Abstract

We present a robust, automatic high-throughput workflow for the calculation of magnetic ground state of solid-state inorganic crystals, whether ferromagnetic, antiferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic, and their associated magnetic moments within the framework of collinear spin-polarized Density Functional Theory. This is done through a computationally efficient scheme whereby plausible magnetic orderings are first enumerated and prioritized based on symmetry, and then relaxed and their energies determined through conventional DFT + U calculations. This automated workflow is formalized using the atomate code for reliable, systematic use at a scale appropriate for thousands of materials and is fully customizable. The performance of the workflow is evaluated against a benchmark of 64 experimentally known mostly ionic magnetic materials of non-trivial magnetic order and by the calculation of over 500 distinct magnetic orderings. A non-ferromagnetic ground state is correctly predicted in 95% of the benchmark materials, with the experimentally determined ground state ordering found exactly in over 60% of cases. Knowledge of the ground state magnetic order at scale opens up the possibility of high-throughput screening studies based on magnetic properties, thereby accelerating discovery and understanding of new functional materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modern high-performance computing has allowed the simulation of crystalline materials and their properties on an unprecedented scale, allowing the construction of large computational materials databases, including the Materials Project and its database of over 86,000 inorganic materials and associated properties.1 These computational databases have led to real-world, experimentally verified advances in state-of-the-art materials design.2

Magnetic materials, in this context meaning an inorganic, crystalline material with a magnetically ordered ground state at 0 K, are of particular interest both due to their wide range of potential applications, such as data storage, spintronic devices,3,4 memristors,5 magnetocaloric-based refrigeration6 and more, and are also of significant interest because of the diversity of fundamental physics at play, including the relation between magnetic order and superconductivity,7,8,9 multiferroic systems10,11 and skyrmions.12

However, despite their importance, magnetic materials have been largely neglected from high-throughput materials computations due to their complexity, with no systematic method employed to explore the magnetic landscape, in particular identifying the ground state of a material from first principles. Previous efforts at high-throughput computation of non-ferromagnetic magnetic materials have been restricted to specific crystal symmetries and specific pre-determined magnetic orderings13 or have only considered simple antiferromagnetic orderings,14 rather than ferrimagnetic orderings or orderings consisting of multiple magnetic sub-lattices, although a sophisticated treatment of paramagnetic phases has been considered15 in addition to the antiferromagnetic cases.

As we will demonstrate in this paper, restricting a search to only a few antiferromagnetic orderings can often lead to an erroneous determination of the ground state magnetic ordering, and justifies a more systematic approach. Currently, the Materials Project database does itself contain a large number of magnetic materials as illustrated in Fig. 1, but the vast majority of these (31,631 of 33,986) are in a ferromagnetic configuration, with only a few well-known antiferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic materials present. While many of these materials might indeed have a ferromagnetic ground state, many materials will exhibit antiferromagnetic or more complex magnetic ground states. Not only will this mean a reported erroneous ground state energy, but also that investigative screening for magnetic properties will be limited in scope.

A survey of magnetic materials is currently available in the Materials Project database based on their atomic magnetic moments, highlighting the specific elements of interest in this present work. The total magnetization of each material is taken to be positive by convention, thus the negative magnetic moments are from materials that exhibit antiferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic order. At present, the vast majority of materials in the Materials Project have only been considered in the ferromagnetic case. Dotted lines show the spin-only magnetic moments for the case of 1, 2, 3, and 4 unpaired electrons, respectively. Only materials containing atoms with non-negligible magnetic moments are shown. Moments from period 4 elements are presented in their order along the period to highlight the trends in magnetic moment

Density Functional Theory has become the de facto tool for calculating material properties due to its efficiency, scalability, and maturity. Within the DFT framework, magnetism can either be neglected completely, be considered in a restricted collinear, non-spin–orbit-coupled case, or include non-collinearity and spin–orbit coupling. In the non-spin–orbit-coupled, collinear case, the total energy of the system is invariant to the rotation of the spins relative to crystallographic cell, and thus the magnetic moments can only be expressed purely as scalar quantities. The non-collinear case, though performed routinely for individual materials, often requires 1–2 orders of magnitude longer computation time, both due to the inclusion of the full spin-density matrix, and also due to reduced symmetry of the system. This places a restriction on the methods available for a high-throughput workflow, and means that a full DFT-based workflow using non-collinear calculations is currently inaccessible. The challenge of high-throughput computation is to find a sufficient compromise such that calculations can be completed in a reliable and timely manner, while also obtaining results that are scientifically useful for the purpose at hand. For many screenings, this purpose might not require absolute accuracy, but rather a low number of false data points such that overall trends are still correct.

In the present study, we therefore present a workflow based on purely collinear DFT simulations with the modest but crucial goal of determining whether a material is ferromagnetic or not in a high-throughput context, and then of attempting to find the ground state magnetic order of a given material at 0 K, presupposing that such a ground state exhibits collinear spin.

The two key advances addressed in this paper are as follows. Firstly, we propose and implement a scheme for enumerating plausible magnetic orderings for a given material, and decide on a ranking for prioritizing calculations. Secondly, we evaluate these generated orderings using a workflow based on conventional DFT + U for a set of well-established magnetic materials, store the differences in energy between the calculated orderings and thus determine the ground-state ordering predicted by DFT.

Results and discussion

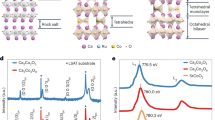

Benchmark structures were drawn from the magndata16 database of magnetic structures. magndata is currently the largest high-quality database of experimentally known magnetic structures, typically determined using neutron powder diffraction. The database consists of a rich cross section of magnetic orderings and also includes, in most cases, the associated magnitude of atomic magnetic moments, although in some instances only direction is known. Some of the entries in the database were deemed unsuitable for the present study, due to either (i) non-collinearity or incommensurate magnetic order, (ii) partial occupancies, or (iii) elements present that are known to be not well described by DFT. As such, a subset of ordered, collinear structures was selected to evaluate our ordering algorithm and workflow. This benchmark set was selected to cover a wide variety of crystallographic structures including spinels and inverse spinels (e.g. Al2CoO4), perovskites and double perovskites (e.g. NaOsO3, EuTiO3), rutiles (e.g. MnF2, Cr2TeO6), corundums and ilmenites (e.g. Cr2O3, TiMnO3), rock salts (NiO, CoO and MnO), and layered and quasi-layered materials (e.g. VClO). In particular, magnetic materials both from well-known, well-understood materials systems, and also lesser-studied magnetic materials, such as those containing Ru or Os, were included to ensure a representative benchmark set. Although f-block elements are notoriously difficult to calculate accurately, Gd and Eu were also included, since these were found to reliably sustain a magnetic moment using the standard VASP pseudopotentials and Materials Project settings. Additionally, both ferrimagnetic materials and materials with multiple magnetic sub-lattices of different elements were included, since these represent particularly complex cases for the enumeration algorithm.

As an initial validation step, the known experimental ground states were computed using the standard DFT workflows found in atomate. Predicted atomic magnetic moments were found to agree well with experimental observation across both a wide range elements and oxidation states, as shown in Fig. 2. A common feature is that the predicted moments were found to cluster around specific values associated with distinct oxidation states in contrast to the wider spread of experimental values, though this spread in experimental values might in part be due to the simulated annealing method commonly used to experimentally determine these moments,17 which is sensitive to noise, peak broadening, and other factors, while the clustering in calculated values is a result of exchange-correlation functional used. There were a few notable failures: while Eu was found to be well-described in that it reliably sustained a magnetic moment and the desired orderings, Gd was not as discussed later, at least among the materials in the benchmark set. This suggests future work suggests future work to better optimize U values and pseudopotentials for Gd. There were two cases where DFT significantly overestimated the magnetic moment including NaFe(SiO3)3 (aegirine), which is a material that exhibits a degeneracy between two different types of magnetic order including an incommensurate phase,18 and LaCrAsO. The latter which belongs to a family of materials important for their superconducting properties and which has proven difficult in previous computational studies,19 although the current workflow did successfully predict the antiparallel spin coupling between adjacent CrAs planes.

A comparison of experimentally determined magnetic moments and the magnetic moments predicted by DFT for the experimentally known magnetic ordering. Points refer to the moments on individual atoms across the different materials in the test set for which the magnitude of experimental moments are known. Solid line shows a robust (Theil–Sen) regression which gives a slope of 0.996 compared to the ideal 1.0, with dotted lines showing the 95% confidence interval of the slope

To test the workflow enumeration algorithm, we ensure that it successfully generates and then ranks the experimental ground state ordering for the selected materials. This is important irrespective of the performance of how the total energy of each ordering is obtained, whether by DFT or otherwise, since the enumeration of the experimental ordering is necessary to evaluate the general ability of the algorithm to find any collinear ordering, and how many different orderings will need to be attempted before the ordering for the true ground state is trialed. An efficient enumeration algorithm necessarily ensures that most experimentally determined ground states are among the highest ranked enumerated orderings. This is found to be the case, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The enumerated orderings are sorted by symmetry, with the first enumerated ordering is always the ferromagnetic case since it is the most symmetrical. Since simple ferromagnetic materials are excluded from this test set, the most likely ordering is at the second index, which is the most symmetrical antiferromagnetic ordering. Subsequently, the distribution matches the desired behavior of the algorithm, with the probability of finding a ground state decreasing as enumeration index increases. The distribution of ground state orderings exhibits a long tail, with the experimental ordering being found as the tenth enumerated ordering in some cases. With this, two distinct cut-offs are proposed that should provide a reasonable chance of enumerating the ground state ordering in most cases. The first cut-off is a soft cut-off of eight orderings, however, if multiple orderings are found with equal symmetry at this index, additional orderings are considered until a hard cut-off of 16 orderings. The exact number of orderings considered will vary depending on the size of the unit cell, number of symmetrically distinct possible magnetic sites in that unit cell, Nsites, and number of magnetic elements present. For the present benchmark this is set to consider a supercell Nsupercells times larger than the primitive cell up to the limit of \(N_{{\mathrm{supercells}}} = \left\lceil {4/N_{{\mathrm{sites}}}} \right\rceil\), such that a sufficient number of supercells will be considered for materials with small primitive cells, while the enumeration algorithm will still complete for materials with large primitive cells. These thresholds ensure that in a high-throughput context not too many spurious calculations are performed, however it does not exclude the possibility to use the enumeration algorithm with much larger cut-offs in the case of specific materials should they be of particular interest. Figure 3 also shows distribution of indices where the DFT-predicted ground state is found after the workflow is run. Though these distributions do not match exactly, the broad distribution of DFT ground state indices closely resembles that of the experimental indices, as would be expected if the workflow performs well.

Histogram showing the index at which the magnetic ground state is generated by the enumeration algorithm in the workflow. With reference to the experimental ground states, the sharp decrease in frequency as enumeration index increases shows that it is reasonable to assume that the ground state will be found if only the first few orderings are attempted, but that given the long tail of this distribution more than the two or three antiferromagnetic orderings typical of many theoretical studies must be attempted to maximize the chance of finding the true ground state

In addition to modifying the choice of maximum supercell size and cut-offs for number of orderings to attempt, the workflow as-written is fully customizable. Users can supply their own mapping of elements to magnetic moment to run the workflow in an additional low-spin configuration, supply their own U values, or enable spin–orbit coupling, which are choices that might be more appropriate for use of the workflow in a low-throughput context.

From the benchmark set, the ability of the workflow to accurately predict the experimental ground-state ordering for each individual benchmark material is summarized in Table 1, where μmax. refers to the maximum atomic magnetic moment determined by experiment or from the ground state predicted by DFT, and ΔE refers to the difference in energy between the predicted ground state ordering and either the calculated energy for the known experimental ordering (expt.) or the calculated energy for the ferromagnetic ordering (FM). Figure 4 shows the total energies of all orderings considered in this benchmark, where each graph represents a distinct material, and with each point representing the energy of a distinct magnetic ordering as a function of the enumeration index. Due to the behavior of the enumeration algorithm, the symmetry tends to decrease along the x-axis, although two adjacent points may exhibit equivalent symmetry. Total energies are normalized to the ferromagnetic ordering in all cases. We note that the energy scale is highly dependent on the specific material, such that the magnetic ordering energy differences range from hundreds of meV to only a few meV per atom. In these later cases, surprisingly, the ground state ordering is often still determined correctly, presumably due to systematic cancellation of errors as a result of a consistent set of simulation parameters being applied across the different orderings. Calculations with very small energy differences between different orderings should be treated with a skepticism, since the absolute energy differences are likely meaningless, for example the cases of Ba2CoGe2O7, YCr(BO3)2, and Li2VSiO5. However, this information is still of interest, since the low sensitivity of total energy to magnetic order might indicate a low transition temperature. Indeed, in these three cases, the materials are only magnetic at very low temperatures and are paramagnetic above 7,20 821 and 3 K22 respectively.

An overview of all benchmark materials calculated by the workflow. Each graph is a separate material, total energy per atom in meV normalized to the ferromagnetic ordering at 0 meV/atom as the y-axis, and x-axis as the enumeration index. Each point therefore refers to the calculation of a separate ordering. The x-axis is the enumeration index with increasing x correlating with decreasing symmetry, with the ferromagnetic case always at x = 0, with the remaining points being non-ferromagnetic orderings. A change in magnetic ordering during electronic minimization this is indicated by a cross. Ground state orderings found experimentally are indicated by a star, while the ground state(s) predicted by the workflow by a large circle: if these coincide, the workflow has correctly predicted the experimental ground state. If there are multiple lowest-energy magnetic orderings of equivalent total energy (within numerical accuracy), these all flagged as ground-state candidates. The total number of successes and failures are summarized in the accompanying bar chart. Some charts have trunctated energy ranges so as not to obscure the detail in the lower energy region of interest

The workflow successfully predicts the experimental ground state in over 60% of the materials benchmarked. In many cases, there are multiple orderings that exhibit very similar energies, and indeed, in nine materials the experimentally determined ground state is found to be very close in energy to the ground state ordering predicted by DFT (these materials are indicated in blue in Fig. 4). As an example, SrRu2O6 is a material with a quasi-two-dimensional honeycomb magnetic lattice of Ru atoms separated by layers of Sr atoms, and as such exhibits very weak interlayer coupling, as confirmed by RPA calculations of this material.23 This is reflected in the workflow results where, even though the predicted ground state ordering did match the experimental ordering, there was a second ordering of very similar energy with the same in-plane magnetic ordering but with different interlayer stacking. Likewise, a case where the predicted ground state did not match experiment is the layered material VClO, where similarly the magnetic in-plane ordering is predicted correctly but the interlayer stacking is different.

Where there is outright disagreement between experiment and computational predictions, there are three main interpretations. Most likely the theoretical prediction itself is in error given the relative coarseness of the high-throughput approach, the nature of the exchange-correlation functionals used and the fixed Hubbard corrections. However, an additional possibility, though unlikely given the robustness and maturity of the neutron diffraction technique, is that experimental measurement or its interpretation may be incorrect. This is especially true considering that many theoretical studies in support of experimental work do not consider orderings beyond the common A-, C- and G-type AFM orderings. As an example of this, consider the case of EuTiO3 which, in our workflow, has a significantly lower energy striped magnetic ordering (two planes of spin-up alternating with two planes of spin-down Eu ions) than the higher symmetry A, C, and G phases previously considered in the literature.24 While this specific case could be spurious due to strong dependence on Hubbard U term,24 it does highlight the value in exploring these lower-symmetry orderings. Finally, disagreement between experiment and workflow predictions might simply be a result of other factors, such as grown-in strain or impurities present in the experimental samples.

Other notable failures of the workflow include Gd2CuO4 which is an example of a class of CuO2 planar compounds important for their superconducting properties, and which exhibits magnetic ordering on both the Cu and Gd sites. While the enumeration algorithm produced plausible inputs in this case, few of the orderings were stable during the electronic state minimization. This is a common failure mode for some materials, which results in many of the magnetic orderings spontaneously relaxing to a non-magnetic configuration. In the case of Gd2CuO4 the predicted ground state possesses two down-spin Gd ions to a single up-spin Gd ion, due to the frustration between Gd atoms, and without a sustained magnetic moment on the Cu ion. We therefore conclude that while the enumeration algorithm and machinery of the workflow are appropriate for this material, the specific choice of pseudopotentials and U values are not, and that further improvement in electronic parameter choices is required before this workflow can be confidently applied to rare-earth magnetic materials. V2CoO6 is an example of a material that, although successfully matched experiment, does highlight a weakness of the workflow in that a magnetic moment was incorrectly initialized on the V site, even though after electronic minimization this moment relaxed to zero.

While, in general, the magnetic ordering after electronic minimization matches that of the initial magnetic ordering, some materials relax spontaneously to their ground state, such as MnCuO2 and NaOsO3, where this latter material would not even sustain a ferromagnetic configuration. As previously discussed, in the case of several materials, the experimentally determined ground states were not determined as the exact ground state by the workflow, but were very similar in energy, where similar here is defined as within an arbitrary window of 0.2 ΔEFM. For example the case of ferrimagnetic Ni3TeO6 or of CaMnBi2, where two orderings are seen to be significantly lower in energy than the other orderings, including the DFT-determined ground state and the experimentally determined ground state. We mark these cases as partial successes of the workflow.

Determining the correct ground state can also lead to improved estimation of band gaps, magnetic moments, and formation enthalpies and other properties, as detailed in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Tables 1–3. While optical properties were not explicitly included in these calculations, the calculations provide an approximate Kohn–Sham gap which can give an estimate of the optical band gap. While many materials that have metallic character in their ferromagnetic configuration, are correctly semiconducting in their predicted magnetic ground state ordering. In the case of formation energies, we also see an improvement, notably in the case of CrN, which has an experimental formation enthalpy of −0.65 eV/atom,14,25 while we calculate a value of −0.55 eV/atom in the ferromagnetic case compared to −0.67 eV/atom in its ground state ordering. Determination of the magnetic ground state is therefore an important initial step before high-throughput calculation of additional properties should be attempted.

This workflow and supporting analyses opens up opportunities for screening based on magnetic properties, and provide a starting point for the investigation of magnetic materials previously unstudied by experimental techniques. Future work includes the consideration of materials whose magnetic ground state is non-collinear or that is highly sensitive to spin–orbit coupling effects, and further optimization of the workflow parameters including choice of functional and U values. All of the results from this study are available on the Materials Project website at materialsproject.org, including interactive representations of the data in this paper. Iterative improvements to this workflow will be communicated in the atomate documentation and Materials Project wiki. The magnetic structures in this paper and additional future outputs from this workflow will also be available via the Materials Project public API and website.

Methods

The workflow presented here is distributed with the atomate26 code, which provides a suite of tested, reusable workflows to calculate a variety of materials properties. These workflows are written as computational ‘recipes’ that use the FireWorks workflow management code,27 which enables the workflows to be managed in a central database and integrates with many high-performance computing systems to enable easy management and tracking of calculations. The outputs of an atomate workflow are then stored in a document-based database for later analysis. In this case, an input structure is provided to the workflow, a series of magnetic orderings is generated, and then for each ordering a structural relaxation and high-quality static calculation are performed using Density Functional Theory with the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) and their results stored in the database. This is followed by a final analysis step, which determines the lowest-energy ordering and characterizes the output with additional useful information, such as the final type of magnetic ordering present (ferromagnetic, antiferromagnetic, ferrimagnetic, or non-magnetic), the magnitude of atomic magnetic moments, and whether any symmetry breaking has occurred. The overall workflow is summarized in Fig. 5. The input structure can be any periodic crystallographic structure and does not need to be annotated with magnetic moments. Plausible magnetic moments will be generated by the Python-based pymatgen analysis code28 and through use of a new MagneticStructureAnalyzer class. Additionally, the capability to input a structure directly from its magnetic space group, based on the magnetic symmetry data tables of Stokes and Campbell,29 or from a magnetic CIF file has also been added for the purposes of this workflow.

Left, the magnetic ordering workflow implemented in the atomate code. Right, a specific example of the ordering algorithm applied to a single example material, LaMnO3, for two illustrative ordering strategies (in this case, just ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic strategies). The input structure is color-coded with La in green, O in red, and Mn in purple (inside O octahedra). For clarity, for the magnetically ordered crystals, the La atoms are hidden, O are in white, and up (down) spin Mn atoms are color-coded as red (blue) respectively

In general, prior to any DFT relaxation, it is desirable to assign plausible initial atomic positions and lattice parameters to promote convergence to the global minimum. Similarly, the initial choice of magnetic moments used to prime the electronic minimizer is of crucial importance. While the size and, sometimes, sign of the magnetic moments will change during a self-consistent electronic minimization procedure, local magneto-structural minima can be difficult to escape. To appropriately sample this space, a set of different initial magnetic moments corresponding to distinct magnetic orderings are generated and each of them calculated independently. The heuristic rule for ferromagnetic orderings is to initialize the system with moments set at or above their high-spin configuration, since it is generally true that a high-spin state will relax to a low-spin state, while a low-spin state will not relax to a high-spin state even if that state is lower in energy. This can be seen illustrated in Fig. 1 where existing high-throughput calculations of materials, all initialized in a high-spin configuration, routinely relax to lower-spin states. Despite this, there will still be cases where a more energetically favorable low-spin configuration might be missed by the electronic minimizer and this is a compromise made in the workflow, although it is designed such that the choice of spin magnitude is easy to customize should a user wish to explicitly include low-spin configurations. In addition to high-spin and low-spin cases, the possibility of zero-spin must also be considered, and this is explicitly included in our workflow. For example, it is possible for the moments on one site to quench the moments on another site such that a configuration, where both sites are initialized with finite moments will result in a higher total energy than if one site is initialized with no moment at all. This exact situation has lead to results inconsistent with experiment and can cause significant misunderstanding,30 but we have found that including a combination of high spin and zero spin initial moments can successfully avoid this issue.

The chosen workflow strategy is to sample this configuration space systematically to maximize the likelihood of finding the true ground state. As previously mentioned, to reduce the degrees of freedom, we restrict our search space to collinear magnetic states. However, it is important to note that this domain still—in principle—contains an infinite number of magnetic orderings, which requires the workflow to set limits and contain a priori prioritization schemes. There are many heuristics and theories for estimating, which magnetic ordering would be the ground state of a given material, such as the Goodenough–Kanamori–Anderson rules, but many of these heuristics rely on chemical intuition that is not necessarily available in a high-throughput context. For example, the oxidation state of a species in a given material is often not known with certainty, and though algorithms exist that can guess what oxidation states are present, such as the bond valence analyzer algorithm found in pymatgen,28 these often fail, including in several cases of important magnetic materials such as inverse spinels. Therefore any strategy for prioritizing magnetic orderings has to be systematic and robust to work at scale and without human intervention. These chemically based heuristics also have known counter examples, which also supports a more systematic approach to enumerating orderings.

The choice made here is to prioritize the most symmetrical magnetic orderings first, provided that they satisfy certain constraints. The algorithms involved in enumerating different magnetic orderings of a given crystal structure are not dissimilar to algorithms for creating ordered approximations of a crystal with partial site occupancies. Leveraging this analogy, we first consider the sites that are potentially magnetic and then construct a co-incident lattice of fictitious dummy ‘spin’ atoms. These sites hold a certain percentage of spin-up dummy atoms and the corresponding percentage of spin-down dummy atoms, where the percentage of up to down spins is referred to as the ‘ordering parameter’ of that site. We refer to this crystal structure including dummy ‘spin’ atoms as a template.

In the case of a simple antiferromagnetic material it is often sufficient to define a global ordering parameter of 0.5 on the magnetic sites and perform the enumeration, or an ordering parameter of 1 for the ferromagnetic case. However, a global ordering parameter is not appropriate for more complex cases. For example, in a case of ferrimagnetism, a global ordering parameter would depend on the number of atoms in each respective magnetic sub-lattice. For example, the postspinel Mn3O431 exhibits two symmetrically in-equivalent Mn sites. Here, the distinct magnetic sub-lattices are both of the same element, although in different oxidation states. The Mn(III) site orders antiferromagnetically, so magnetic moments on this sub-lattice would be generated using an ordering parameter of 0.5, while the Mn(II) site orders ferromagnetically, which requires an ordering parameter of 1 on its sub-lattice. Therefore, to obtain our templates with the correct ordering parameters for the correct sites, multiple strategies are employed that identify these different sub-lattices, whether by the site symmetry, structural motif32 or by the element present, and apply different combinations of ordering parameter to each, allowing each sub-lattice either to be non-magnetic (zero initial spin), ferromagnetic, or antiferromagnetic. Overall, this also allows for the case of ferrimagnetic materials, which can be defined as multiple antiferromagnetic and/or ferromagnetic sub-lattices.

For each template, an enumeration algorithm is then applied. The algorithm is implemented in the pymatgen28 code and builds upon existing functionality that makes use of the enumlib33 enumeration library and spglib34 symmetry analysis libraries. This produces a set of symmetrically distinct crystal structures where each magnetic site is occupied either by a spin-up or spin-down dummy atom. With reference to the element on each site, the dummy atom is then removed, and the underlying site assigned an element-specific spin magnitude.

This collection of distinct magnetic orderings generated from each template are combined into a single list and sorted from most symmetrical to least symmetrical, with the most symmetrical orderings prioritized for calculation. Here, “most symmetrical” is taken simply to mean structures whose space group (determined with spin included as a site coloring to distinguish between otherwise symmetrically equivalent sites) contains the largest number of symmetry operations, and if the number of symmetry operations is equal, they are considered equally symmetric. This sorting of magnetic orderings defines the “enumeration index” in subsequent discussion.

The workflow performs DFT calculations on each ordering using the VASP35,36 code with the PBE exchange-correlational functional and a set of input parameters established by the Materials Project to yield well-converged results in most cases. The only change made to these parameters is to increase the criteria for force convergence, to ensure aspherical contributions are always included in the gradient corrections inside the PAW spheres, and not to use VASP’s in-built symmetrization optimizations. In particular, a common set of standard Hubbard U corrections used by the Materials Project is adopted here, including for corrections for elements Co (3.32 eV), Cr (3.7 eV), Fe (5.3 eV), Mn (3.9 eV), Ni (6.2 eV), and V (3.25 eV). These Hubbard U corrections are included to reduce the error associated with strong on-site Coulomb interactions with standard PBE DFT, and were fitted to reduce the error in a set of known binary formation enthalpies.37 In particular, the workflow uses the rotationally invariant Dudarev form of the Hubbard corrections. This approach will necessarily be insufficient to capture many subtle magnetic properties especially for non-collinear systems or systems where magnetocrystalline anisotropy is significant. In the present study, this standard set of Hubbard U corrections is maintained in the hope that it will be sufficiently transferable to magnetic properties given that there are significant benefits to using the same consistent set of U values as the current Materials Project database, since it allows for seamless integration of energies within the current GGA/GGA + U mixing scheme and therefore of workflow outputs into existing Materials Project functionality, such as the construction of phase diagrams.

During relaxation, the material’s symmetry is allowed to change, followed by a higher quality static calculation with a finer k-point mesh to allow a more accurate total energy evaluation. Future improvements may be to add a dynamic pre-filter step whereby static calculations are performed first to screen out very high-energy configurations before the more computationally expensive geometry optimization is performed.

While the total magnetization of a supercell is calculated using DFT that is well-defined, there are multiple methods for obtaining site-projected magnetic moments. VASP’s native method is to integrate the charge density around an element-specific radius, but this has the unfortunate consequence that the sum of site moments does not match the total magnetization and is also more subject to noise. Here we adopt a method shown to provide good results38 based on integrating the charge difference found within a Bader basin. Since the magnetization density is typically very localized, this method is found to be robust and superior to VASP’s native integration method. This method was implemented for the present study in the pymatgen code, and uses the Henkelman Bader39 code to perform the Bader partitioning.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on the Materials Project website (materialsproject.org), consult Supplementary Table 4 for more information on how to access this data.

Code availability

Code for workflow generation and supporting analysis is available in the atomate code repository (atomate.org) and in the pymatgen code repository (pymatgen.org) respectively.

Change history

13 August 2019

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: the materials project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. Apl. Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Jain, A., Shin, Y. & Persson, K. A. Computational predictions of energy materials using density functional theory. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 15004 (2016).

Wolf, S. et al. Spintronics: a spin-based electronics vision for the future. Science 294, 1488–1495 (2001).

Žutić, I., Fabian, J. & Sarma, S. D. Spintronics: fundamentals and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 323 (2004).

Wang, X., Chen, Y., Xi, H., Li, H. & Dimitrov, D. Spintronic memristor through spin-torqueinduced magnetization motion. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 30, 294–297 (2009).

Guteisch, O. et al. Magnetic materials and devices for the 21st century: stronger, lighter, and more energy efficient. Adv. Mater. 23, 821–842 (2011).

Chubukov, A. V., Efremov, D. & Eremin, I. Magnetism, superconductivity, and pairing symmetry in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 78, 134512 (2008).

Ofer, R. et al. Magnetic analog of the isotope effect in cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 74, 220508 (2006).

Kancharla, S. et al. Anomalous superconductivity and its competition with antiferromagnetism in doped mott insulators. Phys. Rev. B 77, 184516 (2008).

Cheong, S.-W. & Mostovoy, M. Multiferroics: a magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 6, 13 (2007).

Ramesh, R. & Spaldin, N. A. Multiferroics: progress and prospects in thin films. In Nanoscience and Technology: A Collection of Reviews from Nature Journals 6, 21–29 (World Scientific, 2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat1805.

Fert, A., Cros, V. & Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 152 (2013).

Sanvito, S. et al. Accelerated discovery of new magnets in the heusler alloy family. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602241 (2017).

Stevanović, V., Lany, S., Zhang, X. & Zunger, A. Correcting density functional theory for accurate predictions of compound enthalpies of formation: fitted elemental-phase reference energies. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115104 (2012).

Gorai, P., Toberer, E. S. & Stevanović, V. Thermoelectricity in transition metal compounds: the role of spin disorder. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 31777–31786 (2016).

Gallego, S. V. et al. Magndata: towards a database of magnetic structures. i. The commensurate case. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 49, 1750–1776 (2016).

Rodríguez-Carvajal, J. Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 192, 55–69 (1993).

Baum, M. et al. Magnetic structure and multiferroic coupling in pyroxene NaFeSi2O6. Phys. Rev. B 91, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.91.214415 (2015).

Park, S.-W. et al. Magnetic structure and electromagnetic properties of LnCrAsO with a ZrCuSiAs-type structure (Ln = La, Ce, Pr, and Nd). Inorg. Chem. 52, 13363–13368 (2013).

Hutanu, V. et al. Determination of the magnetic order and the crystal symmetry in the multiferroic ground state of Ba2CoGe2O7. Phys. Rev. B 86, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.86.104401 (2012).

Sinclair, R. et al. Magnetic ground states and magnetodielectric effect in RCr(BO3)2 (r = y and ho). Phys. Rev. B 95, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.95.174410 (2017).

Bombardi, A. et al. Direct determination of the magnetic ground state in the square Lattice S = 1/2 antiferromagnet Li2VOSiO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.93.027202 (2004).

Tian, W. et al. High antiferromagnetic transition temperature of the honeycomb compound-SrRu2O6. Phys. Rev. B 92, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.92.100404 (2015).

Ranjan, R., Nabi, H. S. & Pentcheva, R. Electronic structure and magnetism of EuTiO3: a first-principles study. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 19, 406217 (2007).

Kubaschewski, O., Alcock, C. B. & Spencer, P. Materials thermochemistry. Revised. 363 (Pergamon Press Ltd, Oxford, UK,1993).

Mathew, K. et al. Atomate: a high-level interface to generate, execute, and analyze computational materials science workows. Comput. Mater. Sci. 139, 140–152 (2017).

Jain, A. et al. Fireworks: a dynamic workow system designed for high-throughput applications. Concurr. Comput.: Pract. Exp. 27, 5037–5059 (2015).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python materials genomics (pymatgen): a robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Stokes, H., Hatch, D. & Campbell, B. Isotropy Software Suite. http://iso.byu.edu.

Barman, S. R. & Chakrabarti, A. Comment on “physical and electronic structure and magnetism of mn2NiGa: experiment and density-functional theory calculations”. Phys. Rev. B 77, 176401 (2008).

Hirai, S. et al. Giant atomic displacement at a magnetic phase transition in metastable mn 3 o 4. Phys. Rev. B 87, 014417 (2013).

Zimmermann, N. E. R., Horton, M. K., Jain, A. & Haranczyk, M. Assessing local structure motifs using order parameters for motif recognition, interstitial identification, and diffusion path characterization. Front. Mater. 4, 34 (2017).

Hart, G. L., Nelson, L. J. & Forcade, R. W. Generating derivative structures at a fixed concentration. Comput. Mater. Sci. 59, 101–107 (2012).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. Spglib: a software library for crystal symmetry search. arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.01590 (2018).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Jain, A. et al. Formation enthalpies by mixing gga and gga + u calculations. Phys. Rev. B 84, 045115 (2011).

Manz, T. A. & Sholl, D. S. Methods for computing accurate atomic spin moments for collinear and noncollinear magnetism in periodic and nonperiodic materials. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 4146–4164 (2011).

Henkelman, G., Arnaldsson, A. & Jónsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 36, 354–360 (2006).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Roy, B. et al. Experimental evidence of a collinear antiferromagnetic ordering in the frustrated CoAl2o4 spinel. Phys. Rev. B 88, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.88.174415 (2013).

Redhammer, G. J. et al. Magnetic ordering and spin structure in ca-bearing clinopyroxenes CaM2+ (Si, Ge)2O6, M = Fe, Ni, Co, Mn. J. Solid State Chem. 181, 3163–3176 (2008).

Brown, P. J., Welford, P. J. & Forsyth, J. B. Magnetization density and the magnetic structure of cobalt carbonate. J. Phys. C 6, 1405–1421 (1973).

Pertlik, F. Structures of hydrothermally synthesized cobalt(II) carbonate and nickel(II) carbonate. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 42, 4–5 (1986).

Jauch, W., Reehuis, M., Bleif, H. J., Kubanek, F. & Pattison, P. Crystallographic symmetry and magnetic structure of CoO. Phys. Rev. B 64, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.64.052102 (2001).

Rodriguez, E. E., Cao, H., Haiges, R. & Melot, B. C. Single crystal magnetic structure and susceptibility of CoSe2O5. J. Solid State Chem. 236, 39–44 (2016).

Wong, C., Avdeev, M. & Ling, C. D. Zig-zag magnetic ordering in honeycomb-layered Na3Co2SbO6. J. Solid State Chem. 243, 18–22 (2016).

Bertaut, E., Corliss, L., Forrat, F., Aleonard, R. & Pauthenet, R. Etude de niobates et tantalates de metaux de transition bivalents. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 21, 234–251 (1961).

R, M. A. C., Bernès, S. & Vega-González, M. Redetermination of Co4Nb2O9 by single-crystal x-ray methods. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E 62, i117–i119 (2006).

Markkula, M., Arévalo-López, A. M. & Attfield, J. P. Field-induced spin orders in monoclinic CoV2O6. Phys. Rev. B 86, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.86.134401 (2012).

Choi, Y. J. et al. Ferroelectricity in an ising chain magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.100.047601 (2008).

Zubkov, V., Bazuev, G., Tyutyunnik, A. & Berger, I. Synthesis, crystal structure, and magnetic properties of quasi-one-dimensional oxides Ca3CuMnO6 and Ca3Co1+xMn1−xO6. J. Solid State Chem. 160, 293–301 (2001).

Fiebig, M., Fröhlich, D. & Thiele, H. J. Determination of spin direction in the spin-flop phase of Cr2O3. Phys. Rev. B 54, R12681–R12684 (1996).

Sawada, H. Residual electron density study of chromium sesquioxide by crystal structure and scattering factor refinement. Mater. Res. Bull. 29, 239–245 (1994).

Kunnmann, W., Placa, S. L., Corliss, L., Hastings, J. & Banks, E. Magnetic structures of the ordered trirutiles Cr2WO6, Cr2TeO6 and Fe2TeO6. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 29, 1359–1364 (1968).

Damay, F. et al. Magnetoelastic coupling and unconventional magnetic ordering in the multiferroic triangular lattice AgCrS2. Phys. Rev. B 83, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.83.184413 (2011).

Corliss, L. M., Elliott, N. & Hastings, J. M. Antiferromagnetic structure of CrN. Phys. Rev. 117, 929–935 (1960).

Bannikov, V., Shein, I. & Ivanovskii, A. Structural, elastic, electronic properties and stability trends of 1111-like silicide arsenides and germanide arsenides MCuXAs (M = Ti, Zr, Hf; X = Si, Ge) from first principles. J. Alloys. Compd. 533, 71–78 (2012).

Doi, Y., Satou, T. & Hinatsu, Y. Crystal structures and magnetic properties of lanthanide containing borates LnM(BO3)2 (Ln = y, Ho–Lu; M = Sc, Cr). J. Solid State Chem. 206, 151–157 (2013).

Chattopadhyay, T. et al. Magnetic ordering of Cu in Gd2CuO4. Phys. Rev. B 46, 5731–5734 (1992).

Kubat-Martin, K. A., Fisk, Z. & Ryan, R. R. Redetermination of the structure of Gd2CuO4: a site population analysis. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 44, 1518–1520 (1988).

Thompson, J. D. et al. Magnetic properties of Gd2CuO4 crystals. Phys Rev B 39, 6660, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.39.6660 (1989).

Scagnoli, V. et al. EuTiO3 magnetic structure studied by neutron powder diffraction and resonant x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B 86, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.86.094432 (2012).

Allieta, M. et al. Role of intrinsic disorder in the structural phase transition of magnetoelectric EuTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 85, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.85.184107 (2012).

Saha, R. et al. Neutron scattering study of the crystallographic and spin structure in antiferromagnetic EuZrO3. Phys. Rev. B 93, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.93.014409 (2016).

Huang, Q. et al. Neutron-diffraction measurements of magnetic order and a structural transition in the Parent BaFe2As2 compound of FeAs-based high-temperature superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.101.257003 (2008).

Goldman, A. I. et al. Lattice and magnetic instabilities in CaFe2As2: a single-crystal neutron diffraction study. Phys. Rev. B 78, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.78.100506 (2008).

Hill, A. H. et al. Neutron diffraction study of mesoporous and bulk hematite, α-Fe2O3. Chem. Mater. 20, 4891–4899 (2008).

Pernet, M., Elmale, D. & Joubert, J.-C. Structure magnetique du metaborate de fer FeBO3. Solid State Commun. 8, 1583–1587 (1970).

Alikhanov, R. Neutron diffraction investigation of the antiferromagnetism of the carbonates of manganese and iron. Sov. Phys. JETP-USSR 9, 1204–1208 (1959).

Effenberger, H., Mereiter, K. & Zemann, J. Crystal structure refinements of magnesite, calcite, rhodochrosite, siderite, smithonite, and dolomite, with discussion of some aspects of the stereochemistry of calcite type carbonates. Z. Kristallogr.-Cryst. Mater. 156, https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.1981.156.14.233 (1981).

Lançon, D. et al. Magnetic structure and magnon dynamics of the quasi-two-dimensional antiferromagnet FePS3. Phys. Rev. B 94, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.94.214407 (2016).

Melot, B. C. et al. Magnetic structure and properties of the li-ion battery materials FeSO4F and LiFeSO4F. Chem. Mater. 23, 2922–2930 (2011).

Free, D. G. & Evans, J. S. O. Low-temperature nuclear and magnetic structures of La2O2Fe2OSe2 from x-ray and neutron diffraction measurements. Phys. Rev. B 81, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.81.214433 (2010).

Rousse, G., Rodriguez-Carvajal, J., Patoux, S. & Masquelier, C. Magnetic structures of the triphylite LiFePO4 and of its delithiated form FePO4. Chem. Mater. 15, 4082–4090 (2003).

Melot, B. C. et al. Magnetic structure and properties of NaFeSO4F and NaCoSO4F. Phys. Rev. B 85, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.85.094415 (2012).

Tsujimoto, Y. et al. Infinite-layer iron oxide with a square-planar coordination. Nature 450, 1062–1065 (2007).

Singh, Y. et al. Magnetic order in BaMn2As2 from neutron diffraction measurements. Phys. Rev. B 80, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.80.100403 (2009).

Calder, S. et al. Magnetic structure and spin excitations in BaMn2Bi2. Phys. Rev. B 89, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.89.064417 (2014).

Saparov, B. & Sefat, A. S. Crystals, magnetic and electronic properties of a new ThCr2Si2-type BaMn2Bi2 and k-doped compositions. J. Solid State Chem. 204, 32–39 (2013).

Autret, C. et al. Structural investigation of Ca2MnO4 by neutron powder diffraction and electron microscopy. J. Solid State Chem. 177, 2044–2052 (2004).

Lobanov, M. V. et al. Crystal and magnetic structure of the Ca3Mn2O7 ruddlesden–popper phase: neutron and synchrotron x-ray diffraction study. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 16, 5339–5348 (2004).

II, W. R. et al. The magnetic ground state of. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 321, 2612–2616 (2009).

Guo, Y. F. et al. Coupling of magnetic order to planar bi electrons in the anisotropic dirac metals AMnBi2 (A = Sr, Ca). Phys. Rev. B 90, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.90.075120 (2014).

Brechtel, E., Cordier, G. & Schäfer, H. Zur darstellung und struktur von CaMnBi2/on the preparation and crystal structure of CaMnBi2. Z. Naturforsch. B 35, 1–3 (1980).

Moussa, F. et al. Spin waves in the antiferromagnet perovskite LaMnO3: a neutron-scattering study. Phys. Rev. B 54, 15149–15155 (1996).

Lee, S. et al. Antiferromagnetic ordering in Li2MnO3 single crystals with a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 24, 456004 (2012).

Toft-Petersen, R. et al. Magnetic phase diagram of magnetoelectric LiMnPO4. Phys. Rev. B 85, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.85.224415 (2012).

Geller, S. & Durand, J. L. Refinement of the structure of LiMnPO4. Acta Crystallogr. 13, 325–331 (1960).

Fruchart, D. et al. Structure magnetique de Mn3GaC. Solid State Commun. 8, 91–99 (1970).

Brown, P. J. & Forsyth, J. B. The spatial distribution of ferromagnetic moment in MnCO3. Proc. Phys. Soc. 92, 125–135 (1967).

Damay, F. et al. Spin-lattice coupling induced phase transition in the s = 2 frustrated antiferromagnet CuMnO2. Phys. Rev. B 80, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.80.094410 (2009).

Yamani, Z., Tun, Z. & Ryan, D. H. Neutron scattering study of the classical antiferromagnet MnF2: a perfect hands-on neutron scattering teaching course. Special issue on neutron scattering in Canada. Can. J. Phys. 88, 771–797 (2010).

Jauch, W., McIntyre, G. J. & Schultz, A. J. Single-crystal neutron diffraction studies of MnF2 as a function of temperature: the effect of magnetostriction. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 46, 739–742 (1990).

Tsuzuki, K., Ishikawa, Y., Watanabe, N. & Akimoto, S. Neutron diffraction and paramagnetic scattering from a high pressure phase of MnGeO3 (ilmenite). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 37, 1242–1247 (1974).

Goodwin, A. L., Tucker, M. G., Dove, M. T. & Keen, D. A. Magnetic structure of MnO at 10 k from total neutron scattering data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.96.047209 (2006).

Sasaki, S., Fujino, K. & Takéuchi, Y. X-ray determination of electron-density distributions in oxides, MgO, MnO, CoO, and NiO, and atomic scattering factors of their constituent atoms. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 55, 43–48 (1979).

Ressouche, E. et al. Magnetoelectric MnPS3 as a candidate for ferrotoroidicity. Phys. Rev. B 82, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.82.100408 (2010).

Cordier, G. & Schäfer, H. Darstellung und kristallstruktur von BaMnSb2, SrMnBi2 und BaMnBi2/preparation and crystal structure of BaMnSb2, SrMnBi2 and BaMnBi2. Z. Naturforsch. B 32, https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-1977-0406 (1977).

Arévalo-López, A. M. & Attfield, J. P. Weak ferromagnetism and domain effects in multiferroic LiNbO3-type MnTiO3-II. Phys. Rev. B 88, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.88.104416 (2013).

Rodriguez-Carvajal, J., Fernandez-Diaz, M. T. & Martinez, J. L. Neutron diffraction study on structural and magnetic properties of La2NiO4. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 3, 3215–3234 (1991).

Becker, R. & Berger, H. Reinvestigation of Ni3TeO6. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E 62, i222–i223 (2006).

Živković, I., Prša, K., Zaharko, O. & Berger, H. Ni3TeO6—a collinear antiferromagnet with ferromagnetic honeycomb planes. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 22, 056002 (2010).

Ehrenberg, H., Wltschek, G., Rodriguez-Carvajal, J. & Vogt, T. Magnetic structures of the tri-rutiles NiTa2O6 and NiSb2O6. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 184, 111–115 (1998).

Ramos, E., Veiga, M., Fernández, F., Sáez-Puche, R. & Pico, C. Synthesis, structural characterization, and two-dimensional antiferromagnetic ordering for the oxides Ti3(1−x)NixSb2xO6 (1.0 ≥ x ≥ 0.6). J. Solid State Chem. 91, 113–120 (1991).

Plumier, R., Sougi, M. & Saint-James, R. Neutron-diffraction reinvestigation of NiCO3. Phys. Rev. B 28, 4016–4020 (1983).

Ressouche, E., Kernavanois, N., Regnault, L.-P. & Henry, J.-Y. Magnetic structures of the metal monoxides NiO and CoO re-investigated by spherical neutron polarimetry. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 385–386, 394–397 (2006).

Hao, X. F., Stroppa, A., Picozzi, S., Filippetti, A. & Franchini, C. Exceptionally large room-temperature ferroelectric polarization in thePbNiO3multiferroic nickelate: First-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 86, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.86.014116 (2012).

Calder, S. et al. Magnetic structure determination of Ca3LiOsO6 using neutron and x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B 86, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.86.054403 (2012).

Calder, S. et al. Magnetically driven metal–insulator transition in naoso 3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 257209 (2012).

Hiley, C. I. et al. Ruthenium(v) oxides from low-temperature hydrothermal synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 4423–4427 (2014).

Rangan, K. K., Piffard, Y., Joubert, O. & Tournoux, M. Li2VoSiO4: a natisite-type structure. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 54, 176–177 (1998).

Komarek, A. C. et al. Strong magnetoelastic coupling in VOCl: neutron and synchrotron powder x-ray diffraction study. Phys. Rev. B 79, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.79.104425 (2009).

Acknowledgements

M.K.H. acknowledges the primary support of BASF through the California Research Alliance (CARA) and the many useful conversations with our colleagues at BASF. This work was also supported as part of the Computational Materials Sciences Program funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award Number DE-SC0014607. Integration with the Materials Project infrastructure was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division under Contract No. DE-AC02-05-CH11231 (Materials Project program KC23MP). This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. M.K.H. thanks Professor Branton Campbell for the kind permission to use the ISO-MAG data tables in the pymatgen code. Figure 5 created in part with VESTA.40

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K.H. designed and implemented the workflow, generated the data and prepared the manuscript. J.H.M., M.L. and K.A.P. gave scientific and technical advice throughout the project, helped with interpretation of data, and reviewed the manuscript. The project was supervised by K.A.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Horton, M.K., Montoya, J.H., Liu, M. et al. High-throughput prediction of the ground-state collinear magnetic order of inorganic materials using Density Functional Theory. npj Comput Mater 5, 64 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0199-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0199-7

This article is cited by

-

Dataset of theoretical multinary perovskite oxides

Scientific Data (2023)

-

A critical examination of robustness and generalizability of machine learning prediction of materials properties

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Concurrent oxygen reduction and water oxidation at high ionic strength for scalable electrosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide

Nature Communications (2023)

-

AI powered, automated discovery of polymer membranes for carbon capture

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

High-throughput first-principle prediction of collinear magnetic topological materials

npj Computational Materials (2022)