Abstract

Metallic glasses (MGs) possess remarkably high strength but often display only minimal tensile ductility due to the formation of catastrophic shear bands. Purposely enhancing the inherent heterogeneity to promote distributed flow offers new possibilities in improving the ductility of monolithic MGs. Here, we report the effect of the spatial heterogeneity of elasticity, resulting from the inherently inhomogeneous amorphous structures, on the deformation behavior of MGs, specifically focusing on the ductility using multiscale modeling methods. A highly heterogeneous, Gaussian-type shear modulus distribution at the nanoscale is revealed by atomistic simulations in Cu64Zr36 MGs, in which the soft population of the distribution exhibits a marked propensity to undergo the inelastic shear transformation. By employing a mesoscale shear transformation zone dynamics model, we find that the organization of such nanometer-scale shear transformation events into shear-band patterns is dependent on the spatial heterogeneity of the local shear moduli. A critical spatial correlation length of elastic heterogeneity is identified for the simulated MGs to achieve the best tensile ductility, which is associated with a transition of shear-band formation mechanisms, from stress-dictated nucleation and growth to structure-dictated strain percolation, as well as a saturation of elastically soft sites participating in the plastic flow. This discovery is important for the fundamental understanding of the role of spatial heterogeneity in influencing the deformation behavior of MGs. We believe that this can facilitate the design and development of new ductile monolithic MGs by a process of tuning the inherent heterogeneity to achieve enhanced ductility in these high-strength metallic alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metallic glasses (MGs) derive their remarkably high strength from their unique amorphous structure, yet their mechanical properties are often compromised by very limited tensile ductility due to severe strain localization in the form of the shear banding. To tackle the major challenge of ductility in high-strength MGs, structural and mechanical heterogeneities in MGs are desired, which could delocalize strain and suppress shear band instabilities.1,2,3 A conventional engineering route to achieve microstructural heterogeneity is the design of MG-matrix composites by incorporating in situ or ex situ second (or multiple) crystalline phases.4,5 Recently, a new design paradigm, namely the four R’s, has been proposed to achieve ductility via intentionally tailoring the internal structure of the MG itself.3 The four R’s stands for retaining more soft spots (i.e., clusters of atoms that strongly participate in soft vibrational modes6) directly from parent liquid, restraining shear-band propagation and nucleation, rejuvenating glass structure into a more deformable state, and relocating to alloy compositions rich in structural inhomogeneity. Centered on the four R’s is the hypothesis that a monolithic MG, though macroscopically uniform as a single phase, has, in fact, an inherently inhomogeneous amorphous structure that may be tuned.

The heterogeneous amorphous structure and properties of MGs at the nanoscale have been revealed by both modeling and experimental works.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, Ding et al.3,7 discovered two types of motifs in the Cu64Zr36 MGs, icosahedral short-range order (ISRO) and loosely packed “geometrically unfavored motifs” (GUMs). GUMs are usually elastically ‘soft spots’ and are most likely to serve as fertile sites for inelastic shear transformations, giving rise to both structural and mechanical heterogeneities. Using the potential energy landscape model, Fan et al.8,9 derived the atomic-level shear modulus distribution of Cu56Zr44 and revealed that the mechanical instability is due to the aggregation of atoms with low local shear moduli. Furthermore, Wagner et al.12 utilized the atomic force acoustic microscopy to explore the indentation modulus of PdCuSi, which was found to display a Gaussian-like distribution when the cantilever tip was 10 nm. Liu et al.11 applied the dynamic force microscopy to measure the phase shift of Zr55Cu30Ni5Al10 at the nanoscale. A spatial distribution of the phase shift was obtained as a consequence of heterogeneity in local viscoelasticity; in particular, a correlation length of 2.5 nm was identified.

Such nanoscale heterogeneity in MGs focuses on the critical role of the “soft spots”6 that likely undergo stress-driven shear transformation to induce plastic flow. To create ductility, soft spots need to be coordinated over a larger scale, such that the control of heterogeneity has to be translated from the nanometer-scale shear transformation zones (STZs) to their organization into near macroscopic shear-band patterns.3 One way to enhance the heterogeneity is to tune the population by proliferating soft spots through changes in the thermal history,14 rejuvenating MG structure through thermomechanical cycling,15,16 or irradiating MGs into more deformable states.17 A recent continuum model by Wang et al.18,19 proposed a bimodal dispersion of free volume that could result in work hardening and an increase in the free volume gradient that could give rise to a synergy of strength and toughness. In addition, Zhao et al.20,21 also predicted the improvement in ductility by incorporating medium-range ordering (MRO) information into a mesoscale simulation model. Although these experimental and modeling results are encouraging, the specific details are still largely missing concerning the mechanistic details at the STZs’ level and their collective operation into shear-band patterns in the presence of nanoscale heterogeneity. Part of the reason for this is that the time and length scales of individual STZs are too limited either for current experimental resolution or for a continuum mesh to capture directly.

In this work, we employ multiscale modeling techniques to investigate the effect of the spatial heterogeneity of elasticity on the deformation behaviors of the MG, using a Cu64Zr36 MG as the representative system where the local shear moduli display a Gaussian distribution that is directly adopted from atomistic simulations. Explicitly, we use a mesoscale STZ dynamics model to characterize the spatiotemporal correlation of STZs into shear bands in the simulated MGs regulated by various spatial correlations of local shear moduli. We identify a critical correlation length at which the simulated Cu–Zr glass exhibits the best ductility with the largest strain to failure as well as the least propensity for strain localization. On examination of the initial stage of the shear-banding process at various correlation lengths, we observe a transition in the mechanisms of shear-band formation from stress-dominated nucleation and growth to structure-controlled strain percolation, accompanied by saturation of elastically soft sites participating in the plastic flow. Our discussion of these results is focused on determining the correlation between shear-band patterns and soft cluster characteristics extracted from cluster analysis. A hypothesis of critical cluster size for shear-band nucleation is proposed to explain the simulated behavior, together with its implications for developing improved mechanical properties in MGs.

Results

Nanoscale elastic heterogeneity

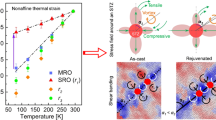

The nanoscale elastic heterogeneity is identified using MD simulations of the model Cu64Zr36 MGs, as shown in Fig. 1a, b. The local shear moduli for two model MGs with different cooling rates (109 K/s and 1011 K/s) are computed by a fluctuation method.22,23,24 At 300 K, the shear moduli in both models exhibit the Gaussian distribution. The MD simulations reveal that the distribution of the local shear moduli is sensitive to the thermal history of the model MG. Fig. 1a shows the distribution of local shear moduli with a sub-cell size of 8 8 Å. As the cooling rate increases from 109 K/s to 1011 K/s, the mean value of the Gaussian distribution decreases from 25.9 to 20 GPa; whereas the deviation (4.44 GPa) remains almost unchanged. Additionally, Fig. 1b illustrates the coarse-grained map of atomic elastic moduli when the cooling rate is 109 K/s, a pronounced spatial heterogeneity is observed with the red and blue colors respectively representing the high ~50 GPa and low ~15 GPa local elastic regions. Our MD simulations, however, did not capture the variation of spatial heterogeneity of elastic constant with respect to MG thermal history, while such variation has been reported experimentally upon thermomechanical processes.16,25 Another limitation of MD simulation for studying elastic heterogneeity problem is the much smaller spatial correlation length (~1-1.5 nm as shown in Fig. 1b), compared to that of reported experimental values in MGs 11 Such discrepancy could be attributed to the inherent limitations of MD simulations, in which fast and uniform cooling rates are adopted to obtain the MG sample with a typical size of ~5 nm.

The spatial heterogeneity of elastic property at the nanoscale. a The Gaussian distributions of local shear moduli of Cu64Zr36 MG obtained by MD simulations under two cooling rates (1011 K/s in blue and 109 K/s in black) and used in the STZ dynamics simulations (in red). b A coarse-grained map of the distribution of local shear moduli obtained by MD simulations at the cooling rate of 109 K/s. c The spatial distributions of local shear moduli in the samples of STZ dynamics simulations with correlation lengths of 0.5 and 5 nm, respectively. d The correlation coefficient as a function of distance (see Eq. 1) for the samples with correlation lengths of ξ = 0.5, 3, 5, and 7 nm, respectively. The correlation length is defined when the value of the correlation coefficient decreases to e-3 = 0.05 at r = ξ

To further establish a connection of the nanoscale elastic heterogeneity and MG deformation at large scale, we employ a mesoscale STZ dynamics model. The STZ dynamics model coarse-grains a collection of atoms, or an STZ as the fundamental deformation unit defined on a finite element (FE) mesh, and controls the stochastic activation of STZs based on the energetics of the system using kinetic Monte Carlo algorithm (kMC). The combination of these two features enables access to the experimentally relevant time and length scale while preserving a microscopic view of the processes of MG deformation. The shear modulus distribution used in the STZ dynamics simulation is displayed as the red curve shown in Fig. 1a, taking the Gaussian distribution identified by the MD simulations with the same standard deviation equal to 4.44 GPa. The average value of the shear modulus is adjusted to 31 GPa by fitting the experimental stress–strain response of Cu64Zr36.26 Such an adjustment can be rationalized by the fact that the average value of the shear modulus is very sensitive to the thermal history of MGs27 evidenced by our MD results.

The spatial heterogeneity of elasticity in the STZ dynamics simulation is tuned by achieving a specific correlation length of the local shear moduli. Following the definition of a spatial autocorrelation function,28 the correlation coefficient of local shear moduli, ρ, is expressed as:

where \(\bar \mu\) denotes the average shear modulus; µr0 is the shear modulus of a reference position r0; µr0+r is the shear modulus at the position which has a distance of r from the reference. The correlation coefficient, ρ, is calculated from all appropriate pairs that are r distance apart from each other. In our simulated MG samples, the correlation coefficient, ρ, decays exponentially with respect to the distance r, as shown in Fig. 1d. We adopt an exponential covariance function ρ(r) = e−3r/ξ,29 used in spatial data analysis to describe the decay, and ξ is the correlation length defined to be the smallest distance beyond which the correlation coefficient ρ is less than 0.05. Furthermore, to obtain the spatial distribution of local shear moduli with a specific correlation length ξ, a reverse Monte Carlo (RMC) method was employed.30 Figure 1c illustrates the map of local shear modulus distributions within the simulation samples with ξ = 0.5 and 5 nm, respectively. Clearly, as the spatial correlation length increases, both elastically soft and hard sites aggregate, giving rise to the larger clustering regions with similar local shear moduli.

Macroscopic stress–strain responses in the presence of nanoscale elastic heterogeneity

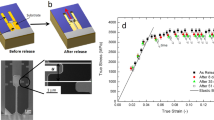

The spatial correlation of elastic heterogeneity significantly affects the macroscopic deformation behaviors of MGs. Fig. 2a illustrates the tensile stress–strain response of the simulated MGs with various correlation lengths. A transition from stress-overshoot to elastic-nearly perfect plastic flow is observed as the spatial correlation length increases. Correspondingly, the deformation morphology changes from a single dominant shear band to the formation of multiple shear bands, as shown in Fig. 2b. For the MG with ξ = 0.5 nm, the significant stress overshoot followed by an abrupt stress drop after yielding is a signature of substantial strain localization in the form of a single dominant shear band. As the correlation length increases to 2 nm, the extent of the stress overshoot is reduced. Correspondingly, the primary shear band becomes less severe as several other strain localization paths start to develop. Once the correlation length reaches 5 nm or larger, the stress overshoot disappears, and the simulated MG exhibits elastic-nearly perfect plastic flow. Meanwhile, the corresponding deformation morphology is characterized by the formation of multiple shear bands with a reduced localized strain in each band. It is not surprising that the increase in the correlation length can alleviate strain localization by forming multiple shear bands, although this effect starts diminishing above a critical correlation length (i.e., 5 nm in this study). For instance, for the MGs with ξ = 7 nm, the extent of strain localization of the most “matured” band is more severe than that in the MGs with ξ = 5 nm.

Mechanical behaviors of the simulated MGs at various correlation lengths. a The representative tensile stress–strain curves of the simulated Cu64Zr36 MG with the correlation lengths ξ = 0.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 nm, respectively. b Snapshots of the von Mises strain of the samples with respective correlation lengths ξ = 0.5, 2, 5 and 7 nm, at a total tensile strain of 0.04. c Yield stress and flow stress vs. the correlation length. d The macroscopic plastic strain failure and the microscopic strain localization index vs. the correlation length

Fig. 2c compiles the data of the yield stresses and the flow stresses vs. spatial correlation lengths for all the MGs (including five independent configurations for each correlation length). Notably, the effect of spatial correlation on the strengths of the MGs, specifically the yield and flow stresses, can be seen to exhibit two regimes. In Regime I, the strength of the MGs is reduced as the spatial correlation increases, whereas in Regime II, the MG strength remains essentially unchanged. The weakening effect in Regime I reflects the increased participation of elastically soft sites during plastic deformation when the spatial correlation is enhanced. In Regime II, starting at the correlation length ξ = 5 nm, the fact that the strength remains roughly constant indicates a critical condition at which the participation ratio of soft sites to carry plastic flow may saturate.

Correspondingly, the dependence of the MG ductility, evaluated by the plastic strain to failure,31 on the spatial correlation ξ also exhibits two regimes, i.e., increasing with increasing ξ in Regime I vs. decreasing with increasing ξ in Regime II. This non-monotonic trend gives rise to the largest plastic strain to failure = 1.037% at the critical correlation length ξ = 5 nm, as shown in Fig. 2d. It should be noted that the current STZ dynamics model has no mechanism for failure; the plastic strain to failure is, therefore, a proxy variable selected to be the macroscopic plastic strain at which the magnitude of local accumulated von Mises strain of an element reaches 0.325 based on a previous study.31 The resultant increasing trend in Regime I is expected, as the enhanced spatial correlation can lead to a larger population of soft sites that undergo plastic flow, promoting the generation of multiple strain-localization paths (Fig. 2b). The decreasing trend in Regime II implies that when the critical condition is reached, i.e., the soft population contributing to plastic flow saturates, further increase in spatial correlation could result in strain localization, rather than distributing flow, which is of course highly detrimental to ductility. In this regard, we can quantify the magnitude of strain localization using a microscopic strain localization index, as proposed in reference.32 This index is defined as the standard deviation of the local von Mises strain of all the elements at a macroscopic strain of 0.04, i.e., reflecting the heterogeneity of microscopic plasticity. As shown in Fig. 2d, the microscopic strain localization index first decreases in Regime I, indicating strain delocalization and homogeneous flow; after reaching the critical correlation length, the index reverses this trend and starts to increase in Regime II, thereby signifying enhanced strain localization.

The process of shear band formation at various correlation length ξ

Next, we delve into the details of the process of shear-band formation and its correlation with elastic heterogeneity. In particular, we choose three cases in Fig. 3: ξ = 0.5 nm, i.e., below the critical correlation length; ξ = 5 nm, i.e., at the critical correlation length; and ξ = 7 nm, i.e., above the critical correlation length. In each of the three cases, the macroscopic stress-strain response is presented, along with the deformation morphology mapped on top of the local shear modulus distribution at the critical moments, for the simulated samples subjected to tensile deformation. To connect with the elastic heterogeneity, the evolution of the participation ratio of the soft sites that have undergone plastic flow is also investigated. At a selected moment, the soft participation ratio is calculated as the number of soft sites that have undergone STZ activation divided by the total number of STZ activated sites. The soft population is taken as the portion of the local sites that have a shear modulus less than the average value of 31 GPa for the sample. Additionally, the shear modulus distributions of the local sites undergoing STZ activity are plotted in comparison to the whole sample distribution, to examine the elastic distribution profile of the activated STZs.

The shear band formation mechanisms in the simulated MG at correlation length of 0.5, 5, and 7 nm. (a), (e), (i) The stress–strain response marked with the critical moments of shear banding. c, g, k The snapshots of von Mises strain distribution at the three critical moments, respectively. The strain distributions on the gray scale are overlapped on the local shear modulus distributions, as represented by the color scale. b, f, j The evolution of the soft participation ratio in the early stage of shear banding. The inset shows the evolution of this ratio over the entire course of deformation. d, h, l The shear modulus distribution of the local sites that have undergone STZ transition at the three critical moments, respectively. For comparison, the distribution of local shear moduli within the whole simulated samples is shown in black

Shear-band formation at the weak correlation of elastic heterogeneity

For the case of the correlation length ξ = 0.5 nm, one dominant shear band is formed even in the presence of elastic heterogeneity, as shown in Fig. 3c. The stress–strain response exhibits a characteristic stress overshoot—immediately after yielding at moment 0, i.e., at the onset of plastic flow, the macroscopic stress continues to climb to a peak at moment 1. Correspondingly, the strain localization is initiated randomly and produces a shear band embryo at moment 1. Upon the formation of the embryo, the stress drops (i.e., from moment 1 to 2) and the shear front propagates progressively along the maximum shear stress path to form an incipient shear band across the sample. As the deformation proceeds, the incipient shear band continues to slide accompanied by its thickening, with the stress relaxing to a flow value (i.e., from moment 2 to 3).

To assess the effect of elastic heterogeneity, the evolution of the soft participation ratio with the tensile strain is plotted in Fig. 3b. In the very early stage of shear band nucleation, e.g., from moment 0 to 1, the soft participation ratio is larger than 75%, such that the soft sites are statistically preferred for STZ activation. From moment 1 to 2 to 3, at the onset of incipient shear-band propagation and growth, the soft participation ratio drops rapidly, as the newly activated STZs become equally likely to be generated from soft or hard sites. This observation is further evidenced by the distributions of the local shear moduli of the activated STZ sites at the three moments, by comparison to the shear modulus distribution of the entire simulated MGs, as displayed in Fig. 3d. At moment 3 in particular, the shear modulus distribution of the activated STZ sites reproduces the probability distribution of the entire sample, showing no preference to the soft sites. Thus, in the case of ξ = 0.5 nm, even though the existence of structural heterogeneity offers a reasonable amount of elastically soft sites that could facilitate strain delocalization, the spatial correlation is not strong enough to do so. Therefore, the concentrated stress in front of the shear band embryo drives the rapid growth of one dominant shear band.

Shear band formation at the critical correlation length ξ

For the MGs with correlation lengths of 5 nm, multiple shear bands are formed to generate plastic flow. Upon yielding at moment 1, the STZs are triggered in several soft sites and evolve into shear band embryos (Fig. 3g). Further straining to moment 2, the embryos penetrate the surrounding locations clustered with relatively low shear moduli regions and form several incipient shear bands. Eventually, the incipient bands connect with each other and develop a percolated strain path throughout the sample to conduct steady plastic flow. Over the course of shear-band formation, the stress barely changes after yielding such that the flow stress remains close to the yield stress in the stress-strain response (Fig. 3e).

On examination of the participation of local sites in the process of plastic flow, the STZ activation is dominated by the soft sites in the early stages of the formation of shear-band embryos from moment 1 to 2 (Fig. 3f), resulting in a soft participation ratio exceeding 95%. When the embryos grow from the very soft regions and connect with each other to form the incipient bands (i.e., from moment 2 to 3), the soft participation ratio slightly drops, as the strain percolation process starts to incorporate harder sites (Fig. 3h). Nevertheless, over the entire shear-band formation process, the soft sites play a truly dominant role in the nucleation and growth of shear bands, i.e., in the very fundamental essence of plastic deformation and ductility in MGs. Therefore, when the spatial correlation of elastic heterogeneity is strong enough (i.e., ξ = 5 nm), the plastic deformation of the MG is controlled by nucleating multiple shear-band embryos to distribute plastic flow.

Shear-band formation at the strong correlation of elastic heterogeneity

Above the critical correlation length, the MG still deforms by forming multiple shear bands, but the number of the bands is reduced. Akin to the case with a critical correlation length of ξ = 5 nm, the stress-strain response of MG with ξ = 7 nm features elastic-nearly perfect plastic flow and the soft sites predominantly control the process of shear-band formation, providing large soft regions to nucleate shear-band embryos. The difference comes from the decrease in the number of shear bands. It is anticipated that the further increase of spatial correlation results in the aggregation of soft regions/clusters enlarged in size but reduced in number. Consequently, fewer soft clusters are now available for the nucleation of shear-band embryos. To accommodate the same amount of plastic flow, the extent of strain localization in each band has to become more severe (Fig. 3k). Additionally, it seems that the large spatial correlation increases the probability to develop a percolated soft path throughout the sample, from which a primary shear band is likely to be formed.

Discussion

A transition in shear-band formation mechanisms

The spatial correlation of elastic heterogeneity can control the organization of STZs into shear-band patterns, leading to a transition in shear-band formation from one of stress-dictated nucleation and growth to structure-dictated strain percolation. We can review the previous theories of shear band formation and propagation in MGs. As summarized by Greer,33 three main viewpoints are most prominent on how shear bands form and propagate from the collective activities of STZs. First, the shear bands are considered as a percolating boundary that reaches a critical concentration of STZs before initiating simultaneous slip along the plane of highest resolved shear stress.34 Second, shear bands are modeled as a propagating zone of rejuvenated glass, followed by a zone of glue-like material, and subsequently by liquid material, as adiabatic heating decreases the local strength.35 Third, a two-step process, with a shear band nucleating from a small cluster of STZs and propagating quickly through the sample before initiating simultaneous slip.36,37

In our simulations, when the correlation length (i.e., ξ < 5 nm) is small, the shear-banding process is reminiscent of the two-step model, in which the stress drives the formation/nucleation of a shear-band embryo before it rapidly grows into a dominant band. The nucleation and growth stages are well distinguished, coming in sequence over the course of deformation (Fig. 3c). The nucleation stage prefers the soft sites but the propagation exhibits no preference, involving both soft and hard sites driven by the concentrated local stress field. On the other hand, when the spatial correlation length is large (i.e., ξ > 5 nm), the two-step process of forming one band is not distinct and might disappear. Instead, several shear-band embryos nucleate at elastically soft sites. The formation of the shear bands occurs by process of connecting/percolating of the shear-band embryos. This process is more like the first model, as the shear bands are initiated from the inherent variation of the local shear moduli and formed via strain percolation.33

Different shear-band morphologies and patterns also emerge due to the transition in the formation mechanisms. When the spatial correlation of the heterogeneity is weak, the stress plays a key role in the nucleation and growth of shear bands and straight shear bands are usually observed along the maximum shear paths (Fig. 3c). As the spatial heterogeneity increases, the shear bands display a non-straight configuration, with a variation in thickness along the line direction and indications of branching on propagation (Fig. 3g, k), features that have been reported experimentally.38,39 For instance, Qu, et al. showed that the brittle titanium-based MG formed one straight shear band while a ductile Pd-based MG formed several curved shear bands in the early stages of plastic deformation. Though our model employs different sample sizes and the relaxation dynamics compared to the experiments,38,39,40 our simulation results clearly reveal that the spatial correlation of the elastic heterogeneity at the nanoscale can be an important factor that significantly influences the shear-banding process and resultant shear-band patterns, which is consistent with the mechanistic insight provided by several recent works at atomic scale.41,42,43

The connection between elastic heterogeneity and deformation behaviors of MGs

To establish a connection between nanoscale elastic heterogeneity and deformation behaviors of MGs, we perform a statistical analysis of the spatial connectivity of the soft sites, termed soft cluster, in the MGs with different levels of spatial correlation, focusing on the number and size of the soft clusters. We then discuss the correlation between these soft cluster characteristics and shear-banding features in light of the resulting mechanical performance of MGs.

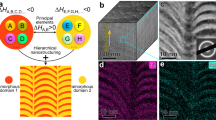

The Hoshen–Kopelman (H–K) algorithm is adopted to determine the cluster characteristics in our 2-D elastically heterogeneous MG samples (method),44 the process of which is illustrated in Fig. 4a–c. Figure 4d shows the resultant soft cluster size distributions for different correlation lengths. As expected, when the correlation length increases, there is a decrease in the number of small-sized clusters and an increase in the number of larger-sized clusters. Consequently, the average cluster size increases but the total number of clusters decreases with the increase of the correlation length, as summarized in Fig. 4e. Moreover, the correlation between the STZ activation sites and the soft cluster locations are progressively enhanced. Figure 4f displays the fraction of the activated STZs within the largest soft cluster, denoted as Pspan, at the total strain of 0.04, vs. the correlation length. The value of Pspan45 increases as the correlation length increases, reflecting that the STZ activations are gradually dictated by the spatial connectivity of the soft sites.

The spatial correlation between STZ activation and the connected soft clusters. a–c An example of soft cluster identification using a simulated MG with ξ = 5 nm, including a the 2-D sample discretization into square cells, b a binary classification of all the cells and c the H–K algorithm to identify the largest soft cluster in the sample. d The histogram of the cluster sizes for three selected correlation lengths, ξ = 0.5, 3, 5, 7, and 9 nm, respectively. e The average cluster size in terms of area and the number of clusters vs. correlation length. f The fraction of the activated STZs within the largest soft cluster, Pspan vs. correlation length

Figure 5 illustrates the correlation between the spatial heterogeneity based on the soft cluster statistics and the resulting deformation behavior, focusing on the two regimes that exhibit different trends. It is noted that when the spatial correlation length increases, the key statistical factor that controls shear band formation changes from the size of the soft clusters to the number of the soft clusters, giving rise to the two regimes of mechanical behavior in MGs. In Regime I, the size of the soft clusters dictates the deformation behavior. As correlation length increases, the soft clusters aggregate and grow in size, facilitating the development of multiple strain-localization paths. In this regime, the shear bands form via nucleation and growth, and thus the larger the size of the clusters, the more effectively they act as nuclei for incipient shear band nucleation, delocalizing plastic flow and enhancing ductility. In Regime II, the number, rather than the size, of the soft clusters plays the dominant role, the enhanced spatial correlation leading to the reduction in the cluster number. In this regime, the shear bands form via strain percolation initiated at the large soft regions. But fewer soft clusters are now available to generate incipient shear bands and to accommodate the same plastic flow. The extent of strain localization in each band has to become severe, equivalently reducing the ductility of MGs.

The correlation between elastic heterogeneity and deformation behavior of the simulated MGs. In Regime I, shear bands form via nucleation and growth. The increase in soft cluster size results in an increased number of shear bands, enhancing ductility. In Regime II, shear bands form via strain percolation from the soft clusters. The decrease in cluster number results in a reduced number of shear bands, detrimental to ductility

We hypothesize that the critical shear band nucleus size is an underlying cause of the transition. As shown in Fig. 3c, in the early stage of plastic flow, STZs appear and begin to cluster into shear band nuclei, which grow before forming a dominant shear band. If the spatial correlation is weak, specifically less than the critical shear band nucleus size, a larger stress is required to activate the adjoining “hard” STZs to reach the critical shear band nucleus size; as such, the smaller the correlation length, the larger the participation ratio of hard sites in creating plastic flow (i.e., the smaller the participation ratio of the soft sites), the higher the resulting strength of the MGs. If instead, the spatial correlation is strong, i.e., equal or larger than the critical shear-band nucleus size, the shear bands are ready to initiate from the soft clusters upon yielding. In this regime, further increases in correlation length do not affect the participation ratio of the soft sites, at least in the early stages of deformation, such that the strength of the MGs remains unchanged. Consequently, an initial increase in correlation length enlarges the soft cluster size, enhancing the capability of distributing flow. When the soft cluster reaches the critical size, the soft cluster number is reduced with increasing correlation, giving rise to strain localization.

It is noteworthy that the prediction of the critical correlation length is restricted by the model limitations, including the simplified glassy state without a structural relaxation dynamics/kinetics,46 the 2D simulated sample geometry47 and the limited finite sample size,48 all of which could affect the critical correlation length and requires the further development of the multiscale model and the integration of the experimental characterization. The MD simulations can investigate the evolution of the local elastic constant distribution subject to various thermomechanical stimuli and further correlate such evolution with STZ activation. The activation energy functionals of STZs that incorporate the local elastic moduli might be developed by using the methods such as the nudged-elastic band (NEB)49,50 or the activation-relaxation technique (ART),9,51 which explore the potential energy landscape of MGs. The development of such activation energy functionals of STZs could inherently capture the nature of disordered glassy structure and the structural dynamics of MGs. The implementation of functionals into STZ dynamics model will significantly improve the accuracy of the prediction of the deformation behaviors at large scales. Nevertheless, the current model could have important implications for improving the macroscale mechanical properties of MGs, specifically, by enhancing ductility of these already high-strength alloys to achieved high fracture toughness and damage-tolerance. It is known that annealing/quenching, mechanical deformation, and radiation can retain or rejuvenate the deformable amorphous state and hence influence the ductility of MGs.3 Perhaps in addition to proliferating the soft spots to enhance the population heterogeneity, these methods can be used to tune the spatial heterogeneity of the glassy structure and increase the number of shear-band nucleation sites to the point that the MG deforms in a more homogeneous manner. A recent experiment provides direct evidence of the intrinsic correlation between β-relaxation and spatial heterogeneity in an MG, and the sub-Tg enthalpy relaxation is demonstrated to be able to regulate the correlation length.25 In addition, the critical correlation length highlights the importance of the spatial/length scale aspects in the heterogeneous amorphous structure, which could guide the design of the optimal spacing of chemical segregation of phase separating MGs,52 the “grain size” in a nanoglass,53 or even the crystalline-amorphous dual-phase nanostructure,54 in order to optimize ductility.

In summary, the important effect of spatial correlation of elastic heterogeneity in tuning the deformation behaviors of metallic glasses is demonstrated using multi-scale modeling techniques. At the atomistic level, MD simulations reveal a highly heterogeneous Gaussian-type distribution of shear moduli at the nanoscale; the soft spots exhibit a greater propensity to undergo STZ transitions. At mesoscale levels, an STZ dynamics simulation is used to investigate the organization of STZs into shear bands. The STZ dynamics model is extended to incorporate the elastic heterogeneity suggested by the MD simulations and to further tune the spatial correlation length of local elasticity using a reverse Monte Carlo algorithm.

A critical spatial correlation length of local shear moduli is identified, dividing the dependence of mechanical properties of MGs on the spatial correlation into two regimes. In the weak correlation Regime I, the strength decreases and ductility increases as the correlation length increases. In the strong correlation Regime II, the strength remains constant and ductility decreases as correlation length increases. Correspondingly, a transition of shear band formation mechanisms is observed. At weak correlations, the shear band forms by stress-driven nucleation and growth, associated with a stress overshoot on the stress–strain responses and characterized by straight shear bands along paths of maximum shear. At strong correlations, the formation of shear bands is controlled by the percolation of soft regions in the heterogeneous glassy structure. The shear bands are now characterized by non-straight bands, which show a variation in thickness along the line directions and evidence of branching upon propagation.

By relating the characteristics of the soft clusters with deformation behaviors, we hypothesize that the critical shear band nucleus size is an underlying cause of the transition. Below the critical size, the increase in correlation length enlarges the size of soft clusters, facilitating the nucleation of incipient shear bands, delocalizing plastic flow and enhancing ductility. Above the critical size, the increase in correlation length decreases the number of soft clusters, limiting strain percolation paths to form shear bands, intensifying the extent of strain localization and reducing the ductility of MGs. Since the population of soft spots and their spatial distribution can be tuned by such processes as rapid quenching,14 high-pressure torsion,55,56,57 laser processing,58 and mechanical cycling,59 and magnetization,60 we envision that our results may offer a totally new approach of using the control of short-range to medium-range order in monolithic MGs to radically improve the ductility, and hence the fracture toughness, of these alloys. As such, this may provide new possibilities for the industrial application of these high-strength metallic alloys as structural materials with unique combinations of mechanical properties.

Methods

MD simulations

The MD simulations of Cu64Zr36 MG with 32,000 atoms (as per the sample studied in reference7) were performed using the optimized embedded atom method (EAM) potential, adopted from reference.61 The melt was equilibrated for 10 ns at high temperature to assure equilibration and then quenched to room temperature (300 K) at cooling rates of 109 K/s and 1011 K/s using the Nose-Hoover thermostat and zero-pressure barostat.62 Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three directions. Isothermal stiffness coefficients (C) were evaluated at room temperature using a fluctuation method.22,23,24 For a canonical (NVT) ensemble, C can be calculated as the sum of three contributions22:

where the superscripts I, II and III represent the Born, kinetic contribution, and the fluctuation terms, respectively (see ref. 22 for more details). To reduce the statistical error in our simulated samples, the average shear modulus (G) was evaluated as: \(G = \bar C_{44} = \frac{{C_{44} + C_{55} + C_{66}}}{3}\), where G can also be decomposed into three terms corresponding to those in Eq. (2). The local elasticity can be evaluated from the atomic scale to the coarse-graining sub-cells, as introduced in ref. 22 Using this approach, the local shear modulus can be plotted with an adequate spatial resolution to reflect its heterogeneous distribution.

The STZ dynamics framework

The STZ dynamics modeling framework, originally developed by Homer et al.63 combines the kMC with the FEM. The MG is simulated by an ensemble of potential STZs defined on a finite element mesh. The kMC algorithm is used to control the activation sequence of STZs and the time evolution of the system. FEM is used to solve the stress and strain redistribution after each STZ activation. The STZ dynamics model successfully captures the general deformation behavior of MGs and has been extended for various implementations.31,36,64,65,66,67

The key constitutive law which describes the activation rate \(\dot s\) for an STZ to shear in one direction can be given by:

where υ0 is the attempt frequency (related to the Debye temperature), ΔF(µ) is the shear modulus dependent activation barrier of the STZ transition, T is the absolute temperature and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The activation rate is biased by the local shear stress τ; Ω0 is the volume of the STZ, and γ0 is a characteristic shear strain increment upon STZ transition. The values of the parameters which were used in this model are given in Table 1. The average shear modulus \(\bar \mu\) is the value for the Cu64Zr36 MG obtained from the ref. 26 ΔF takes a simple functional form of µ, where the coefficient is obtained by fitting the yield strength of Cu64Zr36 MG.26 Ω0 is in the range of values commonly reported in the literature,68 and γ0 is equal to the commonly accepted value.1

For the STZ dynamics simulation, the configurations of the 2D simulated Cu64Zr36 MGs were set with the length and width of 150 and 50 nm, respectively. The long sides of the simulated MGs along the tensile direction were unconstrained, and the top and bottom surfaces of the simulation were allowed to move laterally relative to each other. The simulated tensile test was displacement controlled. This was achieved by constraining the bottom nodes, while the top nodes moved at a fixed velocity corresponding to the desired initial strain rate. The spatial correlation of local shear moduli was tuned for various correlation lengths from 0.5 to 9 nm. For each correlation length, five samples with different spatial distributions of local shear moduli were prepared via RMC, in order to address the statistics. The MGs were loaded in uniaxial tension at a strain rate of 0.01 s−1 and a temperature of 300 K, using STZ dynamics simulation.

Statistical analysis of the connectivity of soft sites in the elastically heterogeneous MG

The H–K algorism is an efficient cluster labeling technique that has been widely used in the determination of the percolation probabilities and cluster size distributions. The following steps were taken in our analysis using an MG sample with correlation length ξ of 5 nm as an example; this is illustrated in Fig. 4a–c. First, we set up a grid onto our 2-D sample and discretize the sample into square cells (Fig. 4a). The grid was fine enough such that each cell is about the size of a fundamental element yet smaller than the size of a potential STZ. Second, each of the square cells is determined to be soft or hard, based on the local shear moduli being respectively smaller or larger than the sample average value of 31 GPa. For this binary classification, all the soft sites are shown in Fig. 4b. Third, the H–P algorithm is used to identify soft clusters by scanning through the cells and labeling the clusters. A labeled soft cluster consists of all the connecting soft cells, the neighbors of which have a common edge. An example of the largest soft clusters is shown in Fig. 4c. In our analysis, we only consider the soft clusters with an area larger than 3.45 nm2, which is slightly larger than an STZ area ~ 2.24 nm2.

Data availability

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Schuh, C. A. et al. Mechanical behavior of amorphous alloys. Acta Mater. 55, 4067–4109 (2007).

Hufnagel, T. C. et al. Deformation of metallic glasses: recent developments in theory, simulations, and experiments. Acta Mater. 109, 375–393 (2016).

Ma, E. & Ding, J. Tailoring structural inhomogeneities in metallic glasses to enable tensile ductility at room temperature. Mater. Today 19, 568–579 (2016).

Hofmann, D. C. et al. Designing metallic glass matrix composites with high toughness and tensile ductility. Nature 451, 1085–1089 (2008).

Qiao, J. et al. Metallic glass matrix composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 100, 1–69 (2016).

Ding, J. et al. Soft spots and their structural signature in a metallic glass. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 111, 14052–14056 (2014).

Ding, J. et al. Full icosahedra dominate local order in Cu64Zr34 metallic glass and supercooled liquid. Acta Mater. 69, 343–354 (2014).

Fan, Y. et al. Evolution of elastic heterogeneity during aging in metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. E 89, 62313 (2014).

Fan, Y. et al. How thermally activated deformation starts in metallic glass. Nat. Commun. 5, 5083 (2014).

Ichitsubo, T. et al. Nanoscale elastic inhomogeneity of a Pd-based metallic glass: sound velocity from ultrasonic and inelastic x-ray scattering experiments. Phys. Rev. B 76, 140201 (2007).

Liu, Y. H. et al. Characterization of nanoscale mechanical heterogeneity in a metallic glass by dynamic force microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 125504 (2011).

Wagner, H. et al. Local elastic properties of a metallic glass. Nat. Mater. 10, 439–442 (2011).

Dmowski, W. et al. Elastic heterogeneity in metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 205502 (2010).

Zhu, Z. D. et al. Elevating the fracture toughness of Cu49Hf42Al9 bulk metallic glass: effects of cooling rate and frozen-in excess volume. Intermetallics 46, 164–172 (2014).

Tong, Y. et al. Structural rejuvenation in bulk metallic glasses. Acta Mater. 86, 240–246 (2015).

Ketov, S. V. et al. Rejuvenation of metallic glasses by non-affine thermal strain. Nature 524, 200–203 (2015).

Magagnosc, D. J. et al. Tunable tensile ductility in metallic glasses. Sci. Rep. 3, 1096 (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. Free volume gradient effect on mechanical properties of metallic glasses. Scr. Mater. 130, 12–16 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Toughen and harden metallic glass through designing statistical heterogeneity. Scr. Mater. 113, 10–13 (2016).

Zhao, P. Y. et al. Influence of nanoscale structural heterogeneity on shear banding in metallic glasses. Acta Mater. 134, 104–115 (2017).

Zhao, P. Y. et al. Heterogeneously randomized STZ model of metallic glasses: softening and extreme value statistics during deformation. Int. J. Plast. 40, 1–22 (2013).

Cheng, Y. Q. & Ma, E. Configurational dependence of elastic modulus of metallic glass. Phys. Rev. B 80, 64104 (2009).

Duan, G. et al. Strong configurational dependence of elastic properties for a binary model metallic glass strong configurational dependence of elastic properties for a binary model metallic glass. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 151901 (2008).

Mayr, S. G. Relaxation kinetics and mechanical stability of metallic glasses and supercooled melts. Phys. Rev. B 79, 60201 (2009).

Zhu, F. et al. Intrinsic correlation between β-relaxation and spatial heterogeneity in a metallic glass. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–7 (2016).

Xu, D. et al. Bulk metallic glass formation in binary Cu-rich alloy series—properties of bulk Cu64Zr36 glass. Acta Mater. 52, 2621–2624 (2004).

Cheng, Y. Q. et al. Correlation between the elastic modulus and the intrinsic plastic behavior of metallic glasses: the roles of atomic configuration and alloy composition. Acta Mater. 57, 3253–3267 (2009).

Kawasaki, T. et al. Correlation between dynamic heterogeneity and medium-range order in two-dimensional glass-forming liquids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 215701 (2007).

Chiles, J. P. & Delfiner, P. Geostatistics: Modeling Spatial Uncertainty. (Wiley, New York, 1999).

McGreevy, R. L. Reverse Monte Carlo modelling. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 13, R877 (2001).

Hardin, T. J. & Homer, E. R. Microstructural factors of strain delocalization in model metallic glass matrix composites. Acta Mater. 83, 203–215 (2015).

Shi, Y. & Falk, M. L. Strain localization and percolation of stable structure in amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 095502 (2005).

Greer, A. L. et al. Shear bands in metallic glasses. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. 74, 71–132 (2013).

Ogata, S. et al. Atomistic simulation of shear localization in Cu-Zr bulk metallic glass. Intermetallics 14, 1033–1037 (2006).

Shimizu, F. et al. Yield point of metallic glass. Acta Mater. 54, 4293–4298 (2006).

Homer, E. R. Examining the initial stages of shear localization in amorphous metals. Acta Mater. 63, 44–53 (2014).

Klaumünzer, D. et al. Stick-slip dynamics and recent insights into shear banding in metallic glasses. J. Mater. Res. 26, 1453–1463 (2011).

Maaß, R. et al. Long range stress fields and cavitation along a shear band in a metallic glass: the local origin of fracture. Acta Mater. 98, 94–102 (2015).

Qu, R. T. et al. Progressive shear band propagation in metallic glasses under compression. Acta Mater. 91, 19–33 (2015).

Qiao, J. C. et al. Transition from stress-driven to thermally activated stress relaxation in metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. B 94, 104203 (2016).

Tian, Z. et al. Strain gradient drives shear banding in metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. B 96, 094103 (2017).

Sopu, D. et al. Atomic-level processes of shear band nucleation in metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 195503 (2017).

Zhu, F. et al. Correlation between local structure order and spatial heterogeneity in a metallic glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 215501 (2017).

Hoshen, J. & Kopelman, R. Percolation and cluster distribution. I. Cluster multiple labeling technique and critical concentration algorithm. Phys. Rev. B 14, 3438–3445 (1976).

Shrivastav, G. P. et al. Yielding of glass under shear: a directed percolation transition precedes shear-band formation. Phys. Rev. E 94, 42605 (2016).

Tsamados, M. et al. Local elasticity map and plasticity in a model Lennard-Jones glass. Phys. Rev. E 80, 26112 (2009).

Ghidelli, M. et al. Homogeneous flow and size dependent mechanical behavior in highly ductile Zr65Ni35 metallic glass films. Acta Mater. 131, 246–259 (2017).

Weiss, J. et al. (Finite) statistical size effects on compressive strength. PNAS 111, 6231–6236 (2014).

Boioli, F., Albaret, T. & Rodney, D. Shear transformation distribution and activation in glasses at the atomic scale. Phys. Rev. B 95, 33005 (2017).

Xu, B. et al. Strain-dependent activation energy of shear transformation in metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. B 95, 144201 (2017).

Rodney, D. & Schuh, C. Distribution of thermally activated plastic events in a flowing glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 235503 (2009).

Kim, J. et al. Acta materialia modulation of plastic flow in metallic glasses via nanoscale networks of chemical heterogeneities. Acta Mater. 140, 116–129 (2017).

Wang, X. L. et al. Plasticity of a scandium-based nanoglass. Scr. Mater. 98, 40–43 (2015).

Wu, G. et al. Dual-phase nanostructuring as a route to high-strength magnesium alloys. Nature 545, 80–83 (2017).

Ubyivovk, E. V. et al. HPT-induced shear banding and nanoclustering in a TiNiCu amorphous alloy. Mater. Lett. 209, 327–329 (2017).

Feng, S. D. et al. Structural evolution of nanoscale metallic glasses during high-pressure torsion: a molecular dynamics analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 36627 (2016).

Joo, S. H. et al. Work-hardening induced tensile ductility of bulk metallic glasses via high-pressure torsion. Sci. Rep. 5, 9660 (2015).

Tsai, P. et al. Hierarchical heterogeneity and an elastic microstructure observed in a metallic glass alloy. Acta Mater. 139, 11–20 (2017).

Ross, P. et al. Linking macroscopic rejuvenation to nano-elastic fluctuations in a metallic glass. Acta Mater. 138, 111–118 (2017).

Huang, B. et al. Tunable elastic heterogeneity caused by deformation-induced magnetization in flexible metallic glass. Scr. Mater. 130, 7–11 (2017).

Cheng, Y. Q. et al. Atomic level structure in multicomponent bulk metallic glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 245501 (2009).

Egami, T. Atomic level stresses. Prog. Mater. Sci. 56, 637–653 (2011).

Homer, E. R. & Schuh, C. A. Mesoscale modeling of amorphous metals by shear transformation zone dynamics. Acta Mater. 57, 2823–2833 (2009).

Li, L. et al. Shear transformation zone dynamics model for metallic glasses incorporating free volume as a state variable. Acta Mater. 61, 3347–3359 (2013).

Li, L. et al. Transient response in metallic glass deformation: a study based on shear transformation zone dynamics simulations. Scr. Mater. 80, 25–28 (2014).

Wang, N. et al. Mesoscopic examination of cyclic hardening in metallic glass. J. Non Cryst. Solids 428, 146–150 (2015).

Harris, M. et al. Competition between shear band nucleation and propagation across rate-dependent flow transitions in a model metallic glass. Acta Mater. 111, 273–282 (2016).

Zink, M. et al. Plastic deformation of metallic glasses: size of shear transformation zones from molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Rev. B 73, 172203 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences (BES), by Award no. DE-SC0016164 for NW and LL, and through the BES Materials Sciences and Engineering Division for JD, MA, and ROR under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 to the Mechanical Behavior of Materials Program (KC13) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL). The study made use of the resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center at LBNL, which is also supported by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.W. conducted STZ dynamics simulations, J.D. performed the MD simulations. J.D. and L.L. designed and organized the study, assisted with data interpretation and designed the paper. All authors discussed the results and participated in writing the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, N., Ding, J., Yan, F. et al. Spatial correlation of elastic heterogeneity tunes the deformation behavior of metallic glasses. npj Comput Mater 4, 19 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-018-0077-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-018-0077-8

This article is cited by

-

Tribological Properties Assessment of Metallic Glasses Through a Genetic Algorithm-Optimized Machine Learning Model

Metals and Materials International (2024)

-

Characterizing Structural Heterogeneity in Metallic Glasses: A Molecular Dynamics-Guided Machine Learning Approach

Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals (2024)

-

Assessment of Nano-Imprinting Process in CuZr Amorphous Films Through Combination of Machine Learning and Molecular Dynamics

Journal of Electronic Materials (2023)

-

Key role of excess atomic volume in structural rearrangements at the front of moving partial dislocations in copper nanocrystals

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Nanometer-scale gradient atomic packing structure surrounding soft spots in metallic glasses

npj Computational Materials (2018)