Abstract

Refractory high entropy alloys feature outstanding properties making them a promising materials class for next-generation high-temperature applications. At high temperatures, materials properties are strongly affected by lattice vibrations (phonons). Phonons critically influence thermal stability, thermodynamic and elastic properties, as well as thermal conductivity. In contrast to perfect crystals and ordered alloys, the inherently present mass and force constant fluctuations in multi-component random alloys (high entropy alloys) can induce significant phonon scattering and broadening. Despite their importance, phonon scattering and broadening have so far only scarcely been investigated for high entropy alloys. We tackle this challenge from a theoretical perspective and employ ab initio calculations to systematically study the impact of force constant and mass fluctuations on the phonon spectral functions of 12 body-centered cubic random alloys, from binaries up to 5-component high entropy alloys, addressing the key question of how chemical complexity impacts phonons. We find that it is crucial to include both mass and force constant fluctuations. If one or the other is neglected, qualitatively wrong results can be obtained such as artificial phonon band gaps. We analyze how the results obtained for the phonons translate into thermodynamically integrated quantities, specifically the vibrational entropy. Changes in the vibrational entropy with increasing the number of elements can be as large as changes in the configurational entropy and are thus important for phase stability considerations. The set of studied alloys includes MoTa, MoTaNb, MoTaNbW, MoTaNbWV, VW, VWNb, VWTa, VWNbTa, VTaNbTi, VWNbTaTi, HfZrNb, HfMoTaTiZr.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High entropy alloys (HEA) are of great technological interest due to their excellent mechanical1, 2 and electronic properties.3 Refractory HEAs, such as e.g. bcc NbMoTaW, possess extraordinary mechanical properties, comparable to current state-of-the-art nickel-based superalloys.2, 4,5,6 This makes them promising candidates for next-generation high-temperature applications. The design of materials for extreme temperature environments requires an accurate knowledge of phase stabilities, thermodynamic properties and thermal conductivity,7 all of which are linked intrinsically to lattice vibrations, i.e. phonons.8, 9 Accurate modeling of phonon excitations and their interactions plays therefore a decisive role in the design, exploration and optimization of such materials.

Phonons can be altered by nano-structural features (e.g., nanoparticles, nanowires),10, 11 they interact with themselves (i.e., phonon-phonon interactions)9 and with chemical disorder, a key feature of HEAs.12,13,14 The interaction with chemical disorder can lead to significant phonon scattering and broadening, if elements of considerable mass difference are involved. In addition to the mass disorder, the locally distinct chemical environments in HEAs can induce force constant variations that also modify the phonon spectral distribution. These force constant variations may be enhanced by local lattice distortions that are known to be important in HEAs.13,14,15,16,17

The large compositional space inherent to HEAs offers the possibility to tune phonon broadening by adjusting the chemical complexity via variation of the relative fractions of the constituent elements and the total number of elements. The mass and force constant induced scattering processes could be, for example, used to modify systematically thermal conductivity (inversely proportional to phonon bandwidth). This is of particular interest for HEAs that were recently suggested as candidates for thermoelectric18, 19 or heat shield materials.7

Tuning chemical complexity in HEAs has been employed to tailor electron scattering and electronic properties20, 21 aiming at improved radiation resistant materials. Similar studies on disorder induced phonon scattering and phonon broadening in HEAs are so far lacking. Previous works addressing phonons in disordered alloys have been mostly limited to binaries.22,23,24,25,26,27 A few works have been devoted to vibrational properties of multi-component alloys,16, 28,29,30,31 but were mainly focused on integrated quantities such as the phonon density of states28 or thermodynamic properties such as lattice specific heat, typically derived from simplified Debye-like models.29, 30 Phonon spectra and in particular mass and force constant induced phonon broadening remain unexplored.

Therefore, we have performed an extensive first-principles study to evaluate phonon broadening for 12 different body-centered cubic (BCC) refractory random alloys, from binaries up to 5-component high entropy alloys. Our set of alloys includes in particular the 4-component NbMoTaW, NbTaTiV, NbTaVW, and 5-component NbMoTaWV, NbTaTiVW, HfMoTaTiZr alloys, which attracted attention recently.4, 16, 30, 32,33,34 On the basis of our results, we address the following fundamental questions: How strongly are phonon spectra affected in high entropy alloys by chemical disorder induced scattering? What is the detailed contribution due to mass and force constant fluctuations? Are both equally important or could one or the other be neglected? And what is the role of the number of constituent elements for phonon broadening?

Results

Figure 1 shows the computed phonon spectra for two sets of alloys, namely MoTa, MoTaNb, MoTaNbW, MoTaNbWV in (a)–(d) and VW, VWNb, VWNbTa, VWNbTaTi in (g)–(j) (added elements in bold), i.e., starting with binaries, moving to ternaries, then quaternaries, and finally to the five-component quinaries. This strategy of adding one element after the other allows us to study systematically the impact of the total number of principal elements on the phonon broadening. For all considered alloys, the long-wavelength limit (region close to Γ) is unaffected, i.e., no broadening is visible and the spectral function is sharply peaked as exemplified in the two 3D insets (e) and (f) for MoTaNbW and MoTaNbWV. This long-wavelength behavior is a consequence of the Rayleigh law (~ ω 4) for impurity scattering.35 For the mid- and high-frequency region (above ~ 4 THz), the broadening turns out to be very strong for all alloys, reaching widths of up to a few THz. Inspecting the first sequence of alloys (Figs. 1a–d), the broadening of the 4- and 5-component alloy spectra appears to be larger compared to the 2- and 3-component ones as exemplified by the grey arrows at the H-point. This dependence is even better visible in the upper panel of Fig. 2 where the spectral function is drawn for the H-point. The impact of the number of components is qualitatively different for the second alloy series (Figs. 1g–j), where a phonon band gap appears for the phonon spectrum of VW around the H-point (grey dashed lines and arrow). This band gap disappears when more elements are added and the overall broadening is slightly contracted.

Broadening of phonon spectra with increasing number of constituent elements: From binaries to 5-component high entropy alloys. The added element for each alloy from left to right is shown in bold. Phonon spectra derived by employing averaged force constants and masses are shown for comparison as black solid lines. Mass-fluctuation scattering parameters Γ M (described in the main text) are shown for each alloy. Insets e and f provide 3D representations of the long-wavelength phonon spectra for MoTaNbW and MoTaNbWV

a-d: Full spectral functions of the first alloy series (MoTa to MoNbTaVW) at the H-point. The dashed lines represent the spectral function (delta peaks) employing averaged force constants and masses. e–h: Spectral functions at the H-point projected on elemental pairs (Mo-Mo blue solid lines with blue shading, Ta-Ta red solid lines with red shading, Nb-Nb dark violet dashed lines, W-W black dashed lines, and V-V green solid lines with green shading) including only mass fluctuations (averaged force constants)

To analyze the observed behavior we will proceed in several steps, starting with a comparison to the most simplified approximation of chemical disorder. For that purpose we derived the phonon spectra based on the virtual-crystal approximation (VCA, black solid lines in Fig. 1 and black dashed lines in Fig. 2), where we replaced the force constants with averaged values according to the crystal symmetries (i.e. by not distinguishing the different constituents) and the atomic masses with averaged masses over the constituents. In the long-wavelength limit and for frequencies below ~ 4 THz the averaged spectra agree very well with the full calculation. However, for frequencies above ~ 4 THz, where the broadening sets in, the averaged dispersions fail in capturing the correct physics. Clearly, due to the averaging procedure broadening cannot be described. Moreover, the averaged dispersions do not match well in position with the corresponding (broadened) peaks in the full dispersion. The discrepancy is most obvious for VW where the averaged dispersion falls into the band gap region of the full calculation. We conclude that the VCA is a too simplified approximation. Similar observations have been recently made for face-centered cubic (FCC) random FePt alloys.36

The effective single-species approximation neglects mass fluctuations. A convenient quantity to characterize the latter is the mass-fluctuation phonon scattering parameter,35

where c i and M i denote the concentration and atomic mass of the i-th component and \(\bar M\) the averaged mass of the alloy. Within the original Klemens model,35 Γ M is proportional to the inverse relaxation time, which is often associated with the overall phonon broadening. We therefore employ our computed spectral functions to investigate a possible relationship.

The scattering parameter, Γ M , for the first alloy series in Fig. 1 upper panel is 0.09, 0.11, 0.10 and 0.19. The minor variation of Γ M between the 2-, 3-, and 4-component alloys (Γ M ≈ 0.1) seems to be inconsistent with our observation above that the 4-component alloy (together with the 5-component one) reveals a more broadened spectrum than the 2- and 3-component ones. Inspecting the second alloy series, where Γ M varies as 0.32, 0.26, 0.20, 0.29, substantiates the conclusion that Γ M alone cannot cover all aspects of phonon broadening. The 2- and 5-component alloys, i.e. VW and VWNbTaTi, reveal qualitatively different phonon broadening although their Γ M parameters are similar (0.32 vs. 0.29). The reason that the Γ M parameter is insufficient to capture all the complexity of the broadening is force constant fluctuations that modify the mass induced fluctuations.

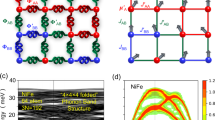

In order to separate the impact of mass and force constant fluctuations, we derived partially averaged phonon spectra with the averaging performed only over the force constants leaving the mass fluctuations unaffected. Subsequently, we applied a recently introduced projection procedure37 that resolves the contribution into the different pair interactions (Mo-Mo, Mo-Ta, etc.). The results for the MoTaNbWV series at the H-point are shown in the lower panel of Fig. 2. The H-point is particularly convenient because, for a one-atomic or an averaged bcc bulk system, only a single frequency mode is present enabling an unbiased analysis of the broadening without intervention from other modes. Taking only the mass fluctuations into account all element-projected contributions to the spectral functions can be directly related to their individual atomic masses. Generally, the lower the atomic mass the higher the frequency and vice versa. For example, Ta has a mass of 181 u and its spectral function (red) is placed in a region of about 4 to 5 THz, shifting somewhat down as the number of elements is increased. Mo is significantly lighter with 96 u and its spectral function (blue) is in the range of 6 to 7 THz. Such a mass analysis makes a straightforward interpretation of the observed Γ M parameter dependence possible: The 2-, 3- and 4-component alloys can be considered as binary or quasi-binary, due to the overlap of some of the atomic masses, thus justifying the similar Γ M ≈ 0.1. It is only the 5-component alloy where a “new” mass of 51 u is introduced. This renders the alloy a quasi-ternary and increases Γ M to 0.19. The spectral functions involving mass fluctuations only (lower panel of Fig. 2) are nicely consistent with this analysis. However, the full spectral functions (upper panel) are quite different and this is caused by force constant fluctuations.

To explain how the force constant fluctuations modify the mass induced broadening, we focus on the VW alloy where the effect is strongest. Figure 3a shows the partially averaged spectral function for VW along the high symmetry directions. The phonon band gap is very large, from about 5 to 8 THz at the H point, due to the significant mass difference between V (51 u) and W (184 u). Figure 3b also shows a partially averaged spectral function. This time however, the mass fluctuations are averaged out leaving the force constant fluctuations unaffected. Although the resulting broadening is smaller than the one caused by the mass fluctuations, it is still significant with a width of about 3 THz. Such a significant impact of force constant fluctuations on the phonon broadening is generally found for the alloys studied here (see Supplementary Information). Inspecting the complete spectral function including both mass and force constant fluctuations (Fig. 3c) reveals that the phonon band gap and the overall broadening are contracted with respect to the spectral function with mass fluctuations only. Similar findings have been reported for random FCC NiPt and CuAu alloys.22,23,24 Our results indicate that such counteractions are also present in multicomponent alloys.

Impact of mass fluctuations and force constant fluctuations on the phonon broadening of the binary VW alloy. a Phonon spectra including only mass fluctuations (averaged force constants), b phonon spectra including only force constant fluctuations (averaged masses), and c phonon spectra including both mass and force constant fluctuations. Phonon spectra derived by employing averaged force constants and averaged masses are shown for comparison (black solid lines)

In order to substantiate this finding, we focus in Figs. 4a, b on the H-point. Figure 4a emphasizes the phonon band gap when only mass fluctuations are considered and clarifies that the lower peak is originating from vibrations of W (184 u) and the upper peak from vibrations of V (51 u). Figure 4b shows that considering only force constant fluctuations the two elements switch positions, V-V interactions are responsible for the lower and W-W interactions for the upper peak. This suggests that the lighter element V has smaller force constants and the heavier W has larger force constants. As a consequence, the force constants counteract the mass induced splitting of the spectral function contracting the band gap and the overall broadening. The resulting full spectral function is shown in Fig. 4a by the grey line. In contrast to the masses, for the force constants the mutual V-W interactions are very important (purple line in Fig. 4b). They lead to a strong damping of the lower-frequency peak and an enhancement of the higher-frequency peak in the final, full spectral function. Similar negative contributions to the spectral function of the mutual interactions have been found and discussed for Cu-Au recently.37

Projected W-W (red lines) and V-V (blue lines) as well as V-W (purple lines) contributions to the spectral functions if only a mass and b only force constant fluctuations are included. In a the total spectral function is shown in grey. c Absolute values of the x-x components of the nearest-neighbor force constants of W-W, V-W and V-V and d the corresponding force constant density of states. The relative peak positions of the force constant density of states in d correlate with the force constant fluctuation contributions to the spectral functions in b and counteract the mass disorder induced contributions to the spectral functions in a. Details are given in the text

The mass fluctuation induced broadening and splitting of the spectral functions can be rather straightforwardly analyzed and understood in terms of the atomic masses, as illustrated above for the MoTaNbWV series (Fig. 2, lower panel). In contrast, the nature of force constant fluctuations is, in general, much more obscure. Such force constant fluctuations are generated from the locally different chemical environments, which can be further modified by the variation of bond lengths (local lattice distortion). Often, however, the main contribution is given by the nearest neighbor force constants and we have therefore investigated this possibility for the present alloys. Specifically, we have computed spectral functions excluding all force constants but the ones with the nearest neighbors. The results (shown in the Supplementary Information) reveal that many features of the phonon spectra and broadening can be observed in these reduced nearest-neighbor calculations, but longer-ranged interactions are needed for quantitative predictions. An example of the first nearest neighbor force constants is given in Figs. 4c, d. Consistent with the above discussion, the V-V interactions reveal smaller force constants than the W-W ones. The relative peak positions for the V-V and W-W force constant distributions in Fig. 4d clearly correlate with the related projections of the spectral functions due to the force-constant fluctuations shown in Fig. 4b.

The relationship between mass and force constant fluctuations is a general phenomenon for the studied alloys. Figure 5 exemplifies this relationship for the 5-component alloys. It shows the mean value of the computed magnitude of nearest-neighbor force constants of all pairs in the 5-component alloys versus the atomic masses. In addition to the already discussed NbTaTiVW and MoNbTaVW alloys, the HfMoTaTiZr alloy38 has been included, motivated by recent interest38 sparked by yield strengths comparable to current state-of-the-art superalloys. Note that the ternary HfNbZr sub-system is discussed in the Supplementary Information. The solid lines represent second order polynomial fits to the computed data and they reveal a clear relation of the masses and force constants for all quinaries. The larger the atomic masses the larger are the computed force constants. This relationship is the underlying reason for the partial compensation of the mass fluctuations by the force constant fluctuations.

Absolute values of the x-x components of the nearest-neighbor force constants of the respective 15 elemental pairs in the 5-component alloys a MoNbTaVW, b NbTaTiVW, and c HfMoTaTiZr. The force constants are shown versus the square-root of the mass product of the atomic pairs including the standard deviation as obtained from the force constant distributions shown in Fig. 4c. The lines are second order polynomial fits to the data. The atomic mass correlates with the computed force constants: the larger the mass, the larger the force constants. This correlation causes a partial compensation of the mass fluctuation induced phonon broadening by the force constant fluctuations

An important tool in the above analysis of the phonon spectral function was the decomposition into the contributions of the various element-element interactions. For the VW binary the projection procedure37 resulted in partial spectral functions for V-V, V-W, and W-W interactions. The virtue of such a decomposition is the close correspondence to force constants between the elements as exploited above. However, for multicomponent alloys the analysis and interpretation based on pair interactions including cross-terms (such as V-W) becomes increasingly cumbersome. For a 5-component alloy already 15 various element-element interactions are present. We therefore propose an alternative projection scheme that allows one to map the total phonon spectral function onto single elements (not element-element pairs). Within this projection scheme, the unfolded partial spectral function for each element X is obtained as

where K is a general wave vector, k k a wave vector in the first Brillouin zone of the underlying crystal structure (here bcc), J a phonon mode index, ω(K, J) the phonon frequency at K and J, and w X(K, J) and \({w_{{{\bf{k}}_k}}}\left( {{\bf{K}},J} \right)\) corresponding weights given by:

Here, \({{\tilde{\bf v}}}\left( {{\bf{K}},J} \right)\) is the phonon eigenmode at K and J, and \({\hat P^{\rm{X}}}\) and \({\hat P^{{{\bf{k}}_k}}}\) are projection operators onto the species X and the wave vector k k . The subscript “0” indicates that the norms are taken for the original unit cell of the supercell model. A detailed derivation of the equations and explicit expressions for the projection operators are given in the Supplementary Information.

The above projection scheme allows us to decompose the full phonon spectra into the individual contributions of each element without requiring cross-terms, thus facilitating the interpretation. To demonstrate the projection scheme we consider the second alloy series in Fig. 1, i.e. VW to VWNbTaTi, but now resolved into the individual contributions of each chemical element. The results are shown in Fig. 6 with the full spectra in the first column and their individually resolved contributions in the corresponding rows. Note that the partial phonon spectral functions include both mass and force constant fluctuations. The decomposition clearly reveals that the highest frequencies for each alloy are predominantly determined by the lightest elements whereas the heavier ones determine the low-frequency parts. This is fully consistent with our findings above. We further see that, apart from the reduced concentration when going from top to bottom, the element specific contributions turn out to be rather independent of the actual alloy. This may open an efficient route for predicting phonon spectra of alloys that have not yet been explored.

Decomposition of the full phonon spectra (first column) into contributions of the individual chemical elements (numbers indicate the atomic mass). The projection onto the elements has been performed employing Eqs. (2) and (3). The seemingly weaker contribution of each element when going from top to bottom is a consequence of the reduced concentration of each element in the given alloy i.e. from 50 at.% for the binary (first row) to 20 at.% in the bottom row (quinary). Decomposition of the second alloy series (MoTa to MoTaNbWV) is given in the Supplementary Information

So far in this section, we have focused on the impact of chemical disorder on spectral functions, i.e., on the detailed wavevector-resolved frequency-dependence of the vibrational spectrum. For thermodynamic equilibrium properties, such as phase stabilities, the spectral function is less clarifying because it enters only after integration over wavevectors and frequencies. To elucidate this issue we computed the vibrational entropy, S vib, in the harmonic approximation using the phonon density of states obtained from the above-discussed spectral functions (see Figs. S1 through S4 in the Supplemental Information).

Figure 7 shows the results for S vib at 1500 K for the MoTa to MoTaNbWV and the VW to VWNbTaTi alloy series in (a) and (b), respectively. The black filled circles and lines represent the full calculations including both, mass and force constant fluctuations, and the other colored lines represent the various approximations as investigated for the phonon broadening. Interestingly, on an absolute scale, even the virtual-crystal-approximation (VCA; orange lines), i.e., the average over mass and force constant fluctuations, provides a reasonable accuracy, in particular for the MoTa to MoTaNbWV series, with errors of about 0.1 k B. The VCA error is larger for the other series, reaching up to 0.3 k B for the VW binary. The fact that the VW binary shows the largest VCA error can be qualitatively understood with reference to the previous analysis of the spectral function for VW that shows a phonon band gap which cannot be captured by the VCA like phonon dispersion (black line in Fig. 1).

a and b: Vibrational entropy for MoTa to MoTaNbWV and VW to VWNbTaTi at 1500 K derived from the phonon density of states (harmonic approximation). The black solid circles include both mass and force constant fluctuations. The orange lines indicate the VCA type spectra (black lines in Fig. 1). The red and blue lines represent the vibrational entropy derived from the approximate spectra including either mass or force constant fluctuations. The green cross indicates the vibrational entropy derived for a B2 ordered (NbTa)(MoW) alloy (see text for details). c and d show the ideal configurational entropy of mixing, and e and f the equilibrium volumes (black filled circles) and averaged atomic masses (grey filled squares) for both alloy series

Although an error of 0.3 k B may seem small in view of the absolute vibrational entropy of 8…9 k B at 1500 K, it can become significant when considering competition between phases. Going beyond the VCA approach by including force constant fluctuations and averaging only over the masses (blue lines in Figs. 7a, b) does not lead to a significant improvement. A much better approximation is achieved by including the mass fluctuations and averaging over the force constants (red lines). This is consistent with our spectral function analysis that the dominating contribution to the phonon broadening is given by the mass fluctuations.

The dependence of the vibrational entropy on the number of constituents differs for the two alloy series. For the MoTa to MoTaNbWV series the changes are relatively small, while for the VW to VWNbTaTi series the vibrational entropy increases monotonically by a substantial amount from the binary (8.2 k B) to the quinary (8.9 k B). These dependencies can be, to a good extent, understood by inspecting the variation of the equilibrium volume and the averaged mass of the alloys, with the volume effect being the dominant one. Generally, increasing the volume results in decreasing phonon frequencies and an enhanced vibrational entropy, which is responsible for the thermal expansion of materials as captured by the quasiharmonic approximation. In this spirit, the strong volume increase when going from VW over to VWNb and then to VWNbTa (black filled circles and lines in Fig. 7f) is responsible for the significant increase in the vibrational entropy for this alloy sequence (black filled circles and lines in Fig. 7b).

The volume effect is modified by the impact of the atomic masses on the phonon frequencies. With reference to the decomposition performed in Fig. 6 and the corresponding discussion, we note again that light elements, i.e., the ones that decrease the average alloy mass, generally correspond to higher frequency regions and heavier elements, i.e., the ones that tend to increase the average alloy mass, to low frequency regions. The connection to the vibrational entropy is then such that it tends to increase when the average alloy mass decreases. The changes in the average atomic mass can counteract the volume effect (as is the case for VW to VWNb, or the sequence MoTa to MoTaNb to MoTaNbW), or can amplify the volume effect (as for VWNb to VWNbTa). Some additional details of these relationships are given in the Supplementary Information.

Finally, to put the changes observed for the vibrational entropy into a proper perspective, we plot the configurational entropy (in the ideal approximation) in Figs. 7c, d using purposefully the same scale as in Figs. 7a, b. The comparison reveals that changes in the vibrational entropy can be of the same magnitude as for the configurational entropy, and thus we conclude that configurational entropy cannot be a priori assumed to be the single dominating contribution to phase stabilities. This conclusion is further supported by explicitly considering the influence of ordering, which we have investigated by performing an additional calculation for the B2 (NbTa)(MoW) alloy, reported to be thermodynamically stable at low temperatures.16, 33 This alloy has two sublattices, with one sublattice containing a random distribution of Nb and Ta, and the other sublattice containing a random distribution of Mo and W. Although the ideal configurational entropy of this alloy is reduced by a factor of 1/2 (green cross in Fig. 7c) as compared to the fully disordered A2 NbMoTaW alloy, the computed phonon spectral functions turn out to be very similar (see Fig. S6 in Supplementary Information). This can be understood by the similar mass disorder on each sublattice in the B2 (NbTa)(MoW) as compared to A2 NbMoTaW. As a consequence the derived vibrational entropy (green cross in Fig. 7a) is hardly affected. This corroborates the statement that configurational entropy is not the sole factor in determining phonon broadening and derived thermodynamic properties.

Discussion

The series of ab initio calculations for phonon spectra of refractory high entropy alloys presented here reveals that it is not only the mere number of constituents, which dominates the chemical disorder induced phonon scattering, but rather the inherent fluctuations in the masses and force constants of the elements. For all considered alloys, strong phonon broadening is observed in the range of mid- to high frequencies (above ~ 4 THz). Mass fluctuations dominate the phonon broadening. However, for quantitative predictions force constant fluctuations cannot be neglected. In fact, for some alloys the neglect of force constant fluctuations can result in predictions of artificial phonon band gaps. In all of the considered alloys the force constant fluctuations counteract the mass disorder induced fluctuations. This might be intuited by the fact that we considered elements from the early transition metal series. Qualitatively the relation between atomic mass and force constants can be understood as follows: Increasing the band filling by going from left to right in the periodic table (e.g. from Hf over Ta to W), not only the atomic masses increase, but also the interatomic bonds are enhanced resulting in increased force constants, which correlates with a decreasing equilibrium volume. Going from top to bottom, e.g. from V over Nb to Ta, the inner core charge and atomic masses increase, resulting in an enhanced local electronic density and thus increased force constants too.

Since atomic mass and force constants jointly contribute to the dynamical matrix and hence phonon energies, this has direct implications for theoretical modeling tools, such as the coherent potential approximation which usually neglect force constant fluctuations.25 The present results further show that conclusions based on a single parameter (e.g. the mass-fluctuation scattering parameter) have little predictive capability because such parameters can neither fully account for the multi-component element character inherent of high entropy alloys nor account for simultaneous mass and force constant fluctuations.

For thermodynamic equilibrium properties, such as the vibrational entropy, one may expect that details of the wavevector-resolved spectral functions are of less importance due to the involved integration. Our analysis shows that this expectation is indeed fulfilled for the force constant fluctuations that show only a small contribution to the vibrational entropy. In contrast, the integration argument does not work well for the mass fluctuations which are found to be significantly more important. When comparing the vibrational entropy with the configurational entropy for a varying number of constituents, we find changes of the same magnitude highlighting the importance of vibrational entropy for phase stability considerations of multicomponent alloys.

For some alloys chemical ordering39 has been reported at lower temperatures. This raises the issue in how far chemical ordering affects phonon broadening and vibrational entropies. Since chemical disorder is the key prerequisite for the derived broadening one might intuit that it would be strongly suppressed by any kind of chemical ordering. We find, however, that such conclusions do in general not apply for HEAs as our B2 (NbTa)(MoW) example reveals. Even though the partial ordering reduces the configurational entropy by a factor of 1/2 compared to the fully disordered alloy, almost no impact on the overall phonon broadening and vibrational entropy is found. Based on our analysis we can therefore conclude that it is not the configurational entropy inherent to HEAs, which controls the vibrational properties such as broadening or vibrational entropy, but rather the specific alloy combination of the involved alloy components.

The present study is a first step towards a full description of lattice excitations in HEAs. Chemical disorder induced scattering is an important part of such a description. The overall phonon broadening at elevated temperatures will be affected by multiple sources (phonon-phonon interactions, extended defect scattering, vacancies). Magnetic fluctuations can be an additional source too.36 Alloys featuring multiple-phases40 will give rise to phonon scattering mechanisms on the nanoscale. Recently, an Al-Hf-Sc-Ti-Zr alloy with partial sublattice ordering has been reported.41 At the same time recent computer simulations suggest the possibility of selective phonon broadening.42 Noteworthy, the disorder-induced broadened high frequency modes carry the highest energies and therefore constitute a very effective frequency range for such a selective filter. The combination of computationally engineered materials with designed phonon broadening may open the route towards a new generation of tailored high-temperature HEAs.

Methods

Electronic structure calculations have been performed with the vasp code43, 44 employing the projector-augmented wave method45 and the generalized gradient approximation.46 To ensure high accuracy, the semi-core p-states of Hf, Mo, Nb, Ta, Ti, V, and W were treated as valence in the employed paw potentials. For Zr, semi-core s-states were treated as valence. A plane wave cutoff energy of 400 eV was chosen throughout all calculations. Chemical disorder was simulated by special quasi random structures (SQS).47 The SQS have been constructed by minimizing the correlation functions of the first two nearest-neighbor shells employing the spcm program. The SQS cells for the equimolar 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-component alloys contain 128, 54, 128, and 125 atoms. For further informations on the spcm program please contact Prof. Andrei V. Ruban (a.v.ruban@gmail.com) .

The equilibrium volume has been determined by computing total energies for at least nine volumes around the equilibrium volume. The atomic coordinates of each supercell were fully optimized with energy convergence criteria set to be less than 10−5 eV per atom while keeping the cubic cell shape. The Methfessel-Paxton technique48 with a smearing value of 0.1 eV has been used. For the total energy calculations of the 54-, 125- and 128-atom cells, k-point grids of 6 × 6 × 6, 4 × 4 × 4, and 4 × 4 × 4 (>8000 k-point*atom) have been employed.

The phonon calculations have been performed at the theoretical equilibrium lattice constant obtained by fitting the Vinet equation of state49 to the total energy calculations. For each alloy, every atom has been displaced in x-, y-, z-direction by a finite displacement of 0.02 Bohr. To ensure a high numerical precision, these calculations have been performed with enhanced energy convergence criteria (<10−7 eV) and k-point grids of 7 × 7 × 7 and 5 × 5 × 5 for the 54-atom and 125-, 128-atom cells, respectively (>16,000 k-point*atom). In addition, an additional support grid for the evaluation of the augmentation charges has been employed. The phonon density of states has been computed employing the phonopy program package.50

The first-principles derived force constants have been employed in the band unfolding method.51,52,53,54 In this method, phonon spectra of random alloys are obtained by decomposing the phonon modes of SQS models onto the Brillouin zone of their underlying crystal structures according to their translational symmetry. Pair-projected contributions of the spectral functions are derived by the recently developed mode decomposition technique37 and by the proposed modified projection scheme. A detailed description is given in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

References

Gludovatz, B. et al. A fracture-resistant high-entropy alloy for cryogenic applications. Science 345, 1153–1158 (2014).

Zou, Y., Ma, H. & Spolenak, R. Ultrastrong ductile and stable high-entropy alloys at small scales. Nat. Commun. 6, 7748 (2015).

Kozelj, P. et al. Discovery of a superconducting high-entropy alloy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 107001 (2014).

Senkov, O. N., Wilks, G. B., Scott, J. M. & Miracle, D. B. Mechanical properties of Nb25Mo25Ta25W25 and V20Nb20Mo20Ta20W20 refractory high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 19, 698–706 (2011).

Senkov, O. N., Wilks, G. B., Miracle, D. B., Chuang, C. P. & Liaw, P. K. Refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 18, 1758–1765 (2010).

Zou, Y., Maiti, S., Steurer, W. & Spolenak, R. Size-dependent plasticity in an Nb25Mo25Ta25W25 refractory high-entropy alloy. Acta. Mater. 65, 85–97 (2014).

Lee, J. I., Oh, H. S. & Park, E. S. Manipulation of σy/κ ratio in single phase FCC solid-solutions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 061906 (2016).

Fultz, B. Phase Transitions in Materials. (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Fultz, B. Vibrational thermodynamics of materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 55, 247–352 (2010).

Poudel, B. et al. High-thermoelectric performance of nanostructured bismuth antimony telluride bulk alloys. Science 320, 634–638 (2008).

Biswas, K. et al. High-performance bulk thermoelectrics with all-scale hierarchical architectures. Nature. 489, 414–418 (2012).

Miracle, D. B. & Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta. Mater. 122, 448–511 (2017).

Gao, M. C., Yeh, J.-W., Liaw, P. K. & Zhang, Y. High-Entropy Alloys: Fundamentals and Applications. (Springer, 2016).

Murty, B. S., Yeh, J. W. & Ranganathan, S. High-Entropy Alloys. (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2014).

Oh, H. et al. Lattice distortions in the FeCoNiCrMn high entropy alloy studied by theory and experiment. Entropy 18, 321 (2016).

Körmann, F. & Sluiter, M. Interplay between lattice distortions, vibrations and phase stability in NbMoTaW high entropy alloys. Entropy 18, 403 (2016).

Wang, W. Y. et al. Revealing the microstates of body-centered-cubic (BCC) equiatomic high entropy alloys. J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. doi:10.1007/s11669-017-0565-4 (2017).

Shafeie, S. et al. High-entropy alloys as high-temperature thermoelectric materials. J. Appl. Phys. 118, 184905 (2015).

Fan, Z., Wang, H., Wu, Y., Liu, X. J. & Lu, Z. P. Thermoelectric high-entropy alloys with low lattice thermal conductivity. RSC Adv 6, 52164–52170 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Influence of chemical disorder on energy dissipation and defect evolution in concentrated solid solution alloys. Nat. Commun. 6, 8736 (2015).

Jin, K. et al. Tailoring the physical properties of Ni-based single-phase equiatomic alloys by modifying the chemical complexity. Sci. Rep 6, 20159 (2016).

Dutta, B. & Ghosh, S. Vibrational properties of Ni x Pt 1− x alloys: An understanding from ab initio calculations. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 053714 (2011).

Grånäs, O., Dutta, B., Ghosh, S. & Sanyal, B. A new first principles approach to calculate phonon spectra of disordered alloys. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 24, 015402 (2011).

Dutta, B., Bisht, K. & Ghosh, S. Ab initio calculation of phonon dispersions in size-mismatched disordered alloys. Phys. Rev. B 82, 134207 (2010).

Alam, A., Ghosh, S. & Mookerjee, A. Phonons in disordered alloys: Comparison between augmented-space-based approximations for configuration averaging to integration from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 75, 134202 (2007).

Chouhan, R. K., Alam, A., Ghosh, S. & Mookerjee, A. Interplay of force constants in the lattice dynamics of disordered alloys: Anab initiostudy. Phys. Rev. B 89, 060201(R) (2014).

Wang, Y., Zacherl, C. L., Shang, S., Chen, L. Q. & Liu, Z. K. Phonon dispersions in random alloys: a method based on special quasi-random structure force constants. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 23, 485403 (2011).

Widom, M. in High-Entropy Alloys: Fundamentals and Applications Ch. 8, (Springer, 2016).

Ma, D., Grabowski, B., Körmann, F., Neugebauer, J. & Raabe, D. Ab initio thermodynamics of the CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy: Importance of entropy contributions beyond the configurational one. Acta. Mater. 100, 90–97 (2015).

Song, H., Tian, F. & Wang, D. Thermodynamic properties of refractory high entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 682, 773–777 (2016).

Caro, M., Béland, L. K., Samolyuk, G. D., Stoller, R. E. & Caro, A. Lattice thermal conductivity of multi-component alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 648, 408–413 (2015).

Yao, H. W. et al. NbTaV-(Ti,W) refractory high-entropy alloys: Experiments and modeling. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 674, 203–211 (2016).

Körmann, F., Ruban, A. V. & Sluiter, M. H. F. Long-ranged interactions in bcc NbMoTaW high-entropy alloys. Mater. Res. Lett 5, 35–40 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Nanoscale origins of the damage tolerance of the high-entropy alloy CrMnFeCoNi. Nat. Commun. 6, 10143 (2015).

Klemens, P. G. The scattering of low-frequency lattice waves by static imperfections. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 68, 1113 (1955).

Ikeda, Y. et al. Temperature-dependent phonon spectra of magnetic random solid solutions. ArXiv e-prints 1702 (2017). http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2017arXiv170202389I.

Ikeda, Y., Carreras, A., Seko, A., Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. Mode decomposition based on crystallographic symmetry in the band-unfolding method. Phys. Rev. B 95, 024305 (2017).

Juan, C.-C. et al. Enhanced mechanical properties of HfMoTaTiZr and HfMoNbTaTiZr refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 62, 76–83 (2015).

Widom, M. Entropy and diffuse scattering: Comparison of NbTiVZr and CrMoNbV. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 47, 3306–3311 (2016).

Li, Z., Pradeep, K. G., Deng, Y., Raabe, D. & Tasan, C. C. Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strength-ductility trade-off. Nature. 534, 227–230 (2016).

Rogal, L. et al. Computational engineering of sublattice ordering in a hexagonal AlHfScTiZr high entropy alloy. Sci. Rep 7, 2209 (2017).

Overy, A. R. et al. Design of crystal-like aperiodic solids with selective disorder-phonon coupling. Nat. Commun. 7, 10445 (2016).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Zunger, A., Wei, S., Ferreira, L. G. & Bernard, J. E. Special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 353–356 (1990).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616–3621 (1989).

Vinet, P., Ferrante, J., Rose, J. H. & Smith, J. R. J. Geophys. Res. [Solid Earth Planets] 92, 9319 (1987).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scripta Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Boykin, T. B., Kharche, N., Klimeck, G. & Korkusinski, M. Approximate bandstructures of semiconductor alloys from tight-binding supercell calculations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 19, 036203 (2007).

Ku, W., Berlijn, T. & Lee, C. C. Unfolding first-principles band structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 216401 (2010).

Popescu, V. & Zunger, A. Extracting E versus k effective band structure from supercell calculations on alloys and impurities. Phys. Rev. B 85, 085201 (2012).

Allen, P. B., Berlijn, T., Casavant, D. A. & Soler, J. M. Recovering hidden Bloch character: Unfolding electrons, phonons, and slabs. Phys. Rev. B 87, 085322 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Andrei V. Ruban for providing the spcm program for generating special quasi-random structures. Discussions with B. Dutta and T. Hickel are acknowledged. Funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through the scholarship KO 5080/1-1, by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 639211), by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan, through the Elements Strategy Initiative for Structural Materials (ESISM) of Kyoto University, and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientist (B) (Grant No. 16K18228) are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.K. and M.S. designed the research, F.K. performed the DFT calculations, Y.I. implemented and applied the band unfolding approach. The results were visualized and analyzed together with B.G. All authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Körmann, F., Ikeda, Y., Grabowski, B. et al. Phonon broadening in high entropy alloys. npj Comput Mater 3, 36 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-017-0037-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-017-0037-8

This article is cited by

-

High-entropy materials for energy and electronic applications

Nature Reviews Materials (2024)

-

Mining of lattice distortion, strength, and intrinsic ductility of refractory high entropy alloys

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Phonon behavior in a random solid solution: a lattice dynamics study on the high-entropy alloy FeCoCrMnNi

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Design of coherent wideband radiation process in a Nd3+-doped high entropy glass system

Light: Science & Applications (2022)

-

Doped high-entropy glassy materials to create optical coherence from maximally disordered systems

Light: Science & Applications (2022)