Abstract

Refractory high-entropy alloys present attractive mechanical properties, i.e., high yield strength and fracture toughness, making them potential candidates for structural applications. Understandings of atomic and electronic interactions are important to reveal the origins for the formation of high-entropy alloys and their structure−dominated mechanical properties, thus enabling the development of a predictive approach for rapidly designing advanced materials. Here, we report the atomic and electronic basis for the valence−electron-concentration-categorized principles and the observed serration behavior in high-entropy alloys and high-entropy metallic glass, including MoNbTaW, MoNbVW, MoTaVW, HfNbTiZr, and Vitreloy-1 MG (Zr41Ti14Cu12.5Ni10Be22.5). We find that the yield strengths of high-entropy alloys and high-entropy metallic glass are a power-law function of the electron-work function, which is dominated by local atomic arrangements. Further, a reliance on the bonding-charge density provides a groundbreaking insight into the nature of loosely bonded spots in materials. The presence of strongly bonded clusters and weakly bonded glue atoms imply a serrated deformation of high-entropy alloys, resulting in intermittent avalanches of defects movement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-entropy alloys (HEAs) composed of four or more elements that form random single-phase crystalline or amorphous (e.g., metallic glass—MG) solid solutions have become a unique class of materials, not only as a scientific curiosity, but also as viable candidates for critical applications.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 Recently, refractory HEAs have shown promising high-temperature properties.4 In a multicomponent HEA systems with a simple crystal structure (typically, a body-centered cubic (BCC), face-centered cubic (FCC), or hexagonal closed-packed (HCP) phase, several empirical principles, guiding the advanced development, have been proposed. These are the ideal enthalpy of mixing (ΔH mix), the entropy of mixing (ΔS mix), the difference of atomic sizes (δ), the electronegativity difference (Δχ), and the valence-electron-concentration (VEC).5, 8,9,10,11 However, the fundamental understanding of the underlying atomic and electronic interactions12,13,14,15,16 is lacking, but critical to reveal the origins of the formation and deformation of HEAs, which, in turn, could be utilized to predict general trends and expand alloy-design strategies.

Up to now, statistical analysis of numerous multicomponent alloys, reported in the literature, allowed the identification of empirical relationships among ΔH mix, ΔS mix, δ, and the types of phases formed in the alloys during casting. In particular, a single crystalline solid solution is likely to form if −22 ~ −15 ≤ ΔH mix ≤ 5 ~ 7 kJ mole−1, 11 ≤ ΔS mix ≤ 19.5 J K−1 mole−1, and 1 ≤ δ ≤ 6, or MGs if −35 ≤ ΔH mix ≤ −8.5 kJ mole−1, 7 ≤ ΔS mix ≤ 14 ~ 16 J K−1 mole−1, and δ ≥ 9.5, 9 Moreover, the formation of FCC- or BCC-type HEAs in a given multicomponent system can be estimated by the value of the VEC, i.e., VEC > 7.5 ~ 8 and VEC < 6 ~ 7.5 for FCC and BCC HEAs, respectively,.5, 9, 11, 17 Recently, a new approach has been established to accelerate the exploration of multicomponent alloys with solid-solution phases by combining calculated phase diagrams with simple rules based on the phases present, transformation temperatures, and attendant microstructures,7 which introduces a technique to predict and achieve target properties (e.g., strength, modulus, and phase stabilities).8, 18, 19

In the present work, we will describe and discuss the atomic and electronic foundations for the VEC-categorized and based principles in FCC or BCC HEAs. Understanding the physical principles guiding these empirical relationships will elucidate and reveal the mechanisms for the formation of single-phase, solid-solution HEAs. In turn, this understanding could be used to predict mechanical properties, such as the yield strength, which, to date, is still under extensive studies.

It is known that the structural and configurational heterogeneities of HEAs and high-entropy metallic glasses (HE-MGs)10, 15, 20 depend strongly on their constituent atomic and electronic structures. As such, emphasis and a more precise interpretation of the local atomic arrangements, for example, the short-range-order (SRO)-dominated deformation (serrated flows16, 21, 22) behavior in the latter, can uncover the nature of the fundamental deformation mechanisms. The atomic basis for the deformation of HE-MGs has been widely studied, and is well understood in terms of viscous flows attributed to weak regions or spots in the material. Such regions include free volumes and liquid-like sites, shear-and tension-transformation zones, and other locally loosely bonded spots.14, 22,23,24,25,26 Recently, similar concepts have been brought forth to connect the local structure to the macroscopic properties of HEAs. Specifically, based on state-of-the-art experiments and simulations,3, 10, 20, 26,27,28 the structure-property relationships of HEAs have been extensively investigated. However, one of the major remaining challenges is how to effectively characterize the local atomic environments in HEAs.

Results

Configurations of HEAs

Herein we treat the ordered and disordered configurations of an equiatomic refractory BCC HEA and elucidate its structure-property relationship and governing deformation mechanisms, using the cluster+glue-atom model29, 30 of the chemical SRO between alloying elements.29, 30 This model is designed to dissociate the alloy’s structure into a cluster and a glue atom parts. Such clusters consist of eight solvent atoms of the 1st nearest neighbor shell and six solvent atoms of the 2nd nearest neighbor shell. Thus, the cluster part can be expressed with a CN14 (coordination number, the number of atoms bonded together, as shown in Fig. 1a). Figure 1 illustrates the supercell structure of the cluster+glue-atom model in the BCC lattice of an ABCD quaternary alloy, in which the BCC structure is expressed by the formula of

Schematic structure of the cluster+glue-atom model in a body-center-cubic (BCC) lattice of an ABCD quaternary alloys. a 3D, (111)supercell and (100)supercell views of the CN14 cluster (the coordination number is 14) with its glue atoms (golden atoms at edge centers and blue atoms in the vertex positions). b Topological structure of each type of element in the BCC lattice generated by the CN14 cluster+glue-atom model. c Configurational transitions of the CN14 clusters via atomic rearrangements, including three ordered configurations (O1 and O2 with the #216 space group, and O3 with the #8 space group) and three random arrangements (R1, R2, and R3 with the #1 space group). The various colors characterize the different kinds of alloying elements for the given equiatomic ABCD BCC HEA alloys, which are kept consistently in the following related figures. In particular, the A, B, C, and D elements are in yellow, wine, green, and blue, respectively

It is noted that with the periodic-boundary condition, this formula results in a 12 atoms for this rhombi-dodecahedral cluster, including the central atom (but still labeled as CN14 based on the physical meaning of CN) since 6 atoms at the face center are shared and counted to be half in the supercell. There are four nearest neighbor atoms of the CN14 cluster included in this model. Figure 1b displays the primary topological structures of each type of alloying element generated by the CN14 cluster+glue-atom model. In this case, we found that there is no chemical bond between the atoms in the same group, which can be estimated by the absence of the 1st and the 2nd peaks of the partial pair correlation functions.31,32,33 The tetrahedrons highlight the 3rd nearest neighbor positions of the same group of atoms. It is worth mentioning that the solute atoms with a large negative ΔH mix construct the clusters, while the glue atoms linked to the cluster have a weakly negative or positive ΔH mix.30 Based on the calculated negative enthalpy of formation matrices obtained from the “data mining” of the binary alloy library and the independent first-principles calculations,8 it is known that the bond pairs preferring to construct the clusters in our studied HEAs are changed in the tendency of Mo-Ta > Mo-Nb > Mo-V > Ta-V > Ta-W > V-W > Nb-W > Nb-V. It is noted that this variation tendency is utilized to present the strong bond pairs, which construct the clusters topologically.33 However, we cannot assume that the Mo will always be the center atom of the cluster. For instance, in the R2 configuration of the MoNbTaWHEA, the Mo atoms located at the 3rd shell of the cluster are glued with the Nb atoms, as presented in Fig. 2c, which can also yield a more stable state than that of the ordered one [i.e., ∆H mix(R2)<∆H mix(O1) for MoNbTaW33].

Structure-dominated compressive property of the BCC MoTaNbW HEA. a The stress–strain curve at a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1 during compressive testing. The various symbols present the corresponding stress states of the invested configurations. b SEM image of the compression fracture surface at room temperature, 298 K, representing a viscous-flow-dominated plastic-deformation behavior (assuming that the weak spots follow a Newtonian-flow behavior with an average viscosity25, 52). c Bonding-charge-density isosurface (Δρ = 0.009 e-Å−3) of configurations of [W3-(Ta 4 Mo 4 Nb 3 W 1 )]Nb1 (labeled as O1), [W3-(Ta 4 Nb 4 Mo 3 W 1 )]Mo1 (labeled as O2), [Ta2Mo1-(Ta 2 Nb 3 Mo 3 W 4 )]Nb1 (labeled as R1), [Mo2W1-(Ta 4 Nb 3 Mo 2 W 3 )]Nb1 (labeled as R2), and [W2Mo1-(W 2 Nb 3 Mo 3 Ta 4 )]Nb1 (labeled as R3) structures in a 3D view, respectively. The insert table presents the details of the first four nearest neighbors of the center atom. Atoms in the CN14 cluster are depicted in red letters. d–h (100)supercell view of the variations of the bonding-charge-density response to an elastic shear under a normal and shear strain (±0.01). The dashed ellipses, circle, and octagon highlight the response of Δρ to the elastic deformations. Plots of the Δρ isosurfaces are generated by the VESTA code65

Through mixing various groups of alloying elements among the CN14 cluster and glue atom positions, the configurational transitions34 guided by atomic-cluster variations can be captured.33 These features are important to reveal the lattice distortions/strains and interactions among the constituent alloying elements. As displayed in Fig. 1c, various atomic rearrangements for the given equiatomic ABCD BCC HEA alloy result in configurational transitions of the CN14 cluster and induce a break of the space group symmetry, which, in turn, manifest themselves as ordered and disordered configurations. Thus, if the hypothetical A–B and C–D bonds are categorized into the same groups as those between the other alloying elements, the ordered O1 and O2 configurations can represent the same groups of alloying elements with and without chemical bonds, respectively.33 The ordered O3 configuration with a different space group is also utilized.33 Therefore, in the present work, the ordered O1, O2, and O3 configurations together with the as-constructed three random arrangements (R1, R2, and R3) are used to study the interactions between the same groups of alloying elements. Four equiatomic refractory HEAs, i.e., MoNbTaW, MoNbVW, MoTaVW, and HfNbTiZr, are selected as case studies, for which MoNbTaW (room temperature hardness, Hv = 4455 MPa35 and yield strength, σ ys = 1058 MPa36) and HfNbTiZr (σys ≈ 879 MPa37) have been generally identified as strong materials.

Similarly, densely-packed SRO structural units of various geometrical configurations (not limited to icosahedral clusters) are universal structural characteristics of HE-MGs;14, 38 these units can be detected by angstrom-scale electron-beam diffraction methods38 and predicted by ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) calculations.20, 39, 40 It turns out that the cluster+glue-atom model is a unique approach that links the relevant local atomic structures and macroscopic properties of HE-MGs. In accord to this model, different SRO clusters are connected with the neighboring clusters with the aid of glue atoms (which, possibly contribute to the free-volume formation or creation of liquid-like regions), thus forming mid-range order configurations. Further, in line with the cluster+glue-atom model, the efficient packing model39 of polyhedra in MGs can have greater implications to understand the nature, forming ability, and properties of MGs.20 Therefore, we choose the Vitreloy-1 MG, Zr41Ti14Cu12.5Ni10Be22.5, hereafter Vit1, as an additional case study. The configurations generated by the AIMD calculations39 at various temperatures provide an insight into the atomic basis for the observed structural features of HE-MGs.

Valance electron concentrations and electron work functions

To investigate the structure–property relationships in the exemplary HEAs and HE-MGs, we characterize interactions among the alloying elements using the electron work function, EWF,18, 41,42,43 and the bonding charge density, Δρ.27, 44 These two parameters are based on the resultant electron redistributions from breaking and forming chemical bonds, respectively. The EWF is the energy required to move an electron from the highest filled level in the Fermi distribution of a solid to a point in the vacuum and specifically represents the atomic interactions or the interactions between electrons and nuclei in the bulk. It can be used to predict the mechanical properties of metallic materials, such as Young’s modulus, hardness, and yield strength.42, 43 In contrast, Δρ is known as the deformation electron density, characterizing chemical bonds via electron redistributions. Consequently, the subsequent response or redistribution of electrons under an applied normal/shear strain is directly measured by the change of Δρ, thus providing the necessary atomic and electronic bases for the deformation behavior of HEAs and HE-MGs, as it is discussed below.

Here, we first study the atomic and electronic basis for the aforementioned VEC-categorized formation of an FCC-type or BCC-type HEA. Based on the previous extensive research on VECs [expressed as \({\rm{VEC}} = {\sum_{i = 1}^n} {c_i}{({\rm{VEC}})_i} \); where (VEC)i and ci are the VEC and the atomic fraction of the ith element, respectively)] and the electron concentration (defined as the number of electrons per unit cell using the Hume-Rothery rules) of the HEA,9, 11, 37 as shown in Fig. 3a, we observe that a mixture of alloying elements from Groups IVB, VB, and VIB forms BCC-type HEAs, consistent with the BCC-lattice structure of these elements (shades of yellow). In contrast, the mixture of dominant alloying elements from Groups VIIIB, IB, and IIB, would form the FCC-type HEAs (shades of orange to red). Moreover, from Fig. 3a, it is evident that there is no change in the VEC if the alloying elements are combined from the same group. However, a more remarkable difference in the EWF among the elements from the same group could be revealed by including the density (atomic size or volume) in the ab initio calculation of the EWF, as described in more detail in the Methods section. Based on the trends exhibited in the figure, it is expected that the structure–property relationship in HEAs and HE MGs can be revealed in terms of EWF.

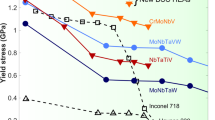

Correlations between the electron work function (EWF) and yield strength. a the EWF41 and valence electron concentration (VEC 9) of the pure elements with gradient colors determined by its quantities. b An analysis and comparison of the power-law scaled yield strength of high-entropy alloys (HEAs) and metallic glasses (MGs) to an experimental data set. The EWFs of these alloys are estimated from the ideal mixing of EWF of the pure elements. c–e The predicted yield strength of the ordered configurations (O1, O2, O3), random arrangements (R1, R2, R3) and amorphous configurations (AM1, AM2, AM3, AM4, AM5, AM6) for the MoTaNbW and HfNbTiZr HEAs, and Vitreloy-1 MG (Zr 41 Ti 14 Cu 12.5 Ni 10 Be 22.5 ) Vit1, illustrating the effect of configurational transition on the yield strengths, respectively. The solid line together with its error bar (± 260 MPa) in b indicates the general variation between the predicted yield strength vs. that of the experimental data. (More information can be found in the Table S1 and Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Information)

Power-law scaled yield strength

The yield strength (σ ys) of a set of HEAs and HE-MGs is presented in Fig. 3b and Table S1 with respect to their EWF (φ). The dependence of σ ys on φ is expressed as

The exponent of 6 with respect to the EWF is taken from previous observations of the dependence of the yield strength and shear modulus (G) of metallic materials on EWF and a unique characteristic structural length (λ = 2π/q 1, where q 1 = 2k F is the first peak position of the total structure factor, and k F is the electron vector45). For MGs,18 σ ys = 223 λ−6±0.4, and G = 4188 λ−6±0.4. It is worth mentioning that both φ and λ in these power-law-scaling relations are treated as the indicators of the electronic interactions, which are in line with the universal relation between the total energy and electron density.18, 46, 47 In Fig. 3b and Table S1, the EWF values of our two exemplary HfNbTiZr and MoNbTaWHEAs (open symbols), obtained from the Halas-Durakiewicz (HD) model41 (see the description in the Methods section), are smaller than those estimated from those of pure elements (\(\phi = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{i = 1}^n {{c_i}{\phi _i}} \), solid symbols); more details are shown in Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Information section. On one hand, it is understood that besides the solid-solution strengthening, the grain refinement and the precipitates-strengthening mechanisms should also play an important role in determining the yield strength. Since those two strengthening mechanisms are not considered here, that’s the reason why there is a significant error bar (±260 MPa) of the predicted results, compared with the experimental ones, shown in Fig. 1b of the Supplementary Information section. On the other hand, this is attributed to the over/lower estimate using EWF, compared to ideal mixing (ignoring the volume variations caused by the interactions of alloying elements) of the pure elements. Moreover, it is believed that the over/lowerestimations would be fixed by combining the different contributions from those various strengthening mechanisms19 and calculating a precise EWF, and thus, to reveal the deformation/strengthening mechanisms of complex structures (including defects, chemistry, and orientations).

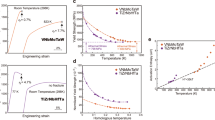

Figure 3c–e are the currently predicted yield strengths of the ordered configurations (O1, O2, and O3), random arrangements (R1, R2, and R3) and amorphous configurations (AM1, AM2, AM3, AM4, AM5, and AM6) for the MoTaNbW and HfNbTiZr HEAs, and Vit1MG, depicting the effect of the configurational transition on the yield strength, respectively. The magnitude of σ ys (the measured yield strength) fluctuation of the Vit1 is about 1% (20 MPa); this value agrees well with experimental observations of the stress fluctuations in the measured stress–strain curves of Zr-based MGs.23, 48 It can be seen that the magnitude of the σ ys fluctuation (< 1%) for MoNbTaW among the five configurations (O1, O2, R1, R2, and R3) is smaller than that of HfNbTiZr (~ 1.5%), which is in agreement with the detected strain steps in the stress–strain curves (Fig. 2a and Fig. 4a, respectively). The essence of these two correlations between the EWF and σ ys is that the bonding-charge density plays a major role in the plastic deformation process. It further indicates that the bond breaking and forming characteristics are the intrinsic features of the shear-deformation process, also applicable to the deformation-twin mechanism, ordinary dislocation mechanism, atomic shuffle mechanism, etc.49,50,51

Structure-dominated tensile property of the BCC HfZrTiNb HEA. a The stress–strain curve at a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1 during tensile testing. The various symbols present the corresponding stress states of the invested configurations. b SEM image of the tensile fracture surface at room temperature, 298 K, representing a viscous-flow-dominated plastic-deformation behavior. c bonding-charge-density isosurface (Δρ = 0.008 e−Å−3) of configurational transformations of ([Zr3-(Ti 4 Hf 4 Nb 3 Zr 1 )]Nb1) (labeled as O1), ([Zr3-(Ti 4 Nb 4 Hf 3 Zr 1 )]Hf1) (labeled as O2), [Ti2Hf1-(Ti 2 Nb 3 Hf 3 Zr 4 )]Nb1 (labeled as R1), [Hf2Zr1-(Ti 4 Nb 3 Hf 2 Zr 3 )]Nb1 (labeled as R2), and [Zr2Hf1-(Zr 2 Nb 3 Hf 3 Ti 4 )]Nb1 (labeled as R3) structures in a 3D view. The insert table presents the details of the first four nearest neighbors of the center atom. Atoms in the CN14 cluster are written in red letters. d–g (100)supercell view of the variations of the bonding-charge-density response to an elastic shear under anormal and shear strain (±0.01). The dashed ellipses and diamonds highlight the response of Δρ to the elastic deformations. Plots of the Δρ isosurfaces are generated by the VESTA code65

Discussion

Compared to the observed serration behaviors5, 16, 23 of HEAs and HE-MGs during deformation, the captured fluctuations of the calculated yield strengths caused by the configurational transitions, shown in Fig. 3b–e, allows us to understand and interpret better the deformation mechanisms governing these materials. In light of the extensive statistics of MG deformation,14, 23,24,25, 48, 52 our model, as shown below, demonstrates that the proposed viscous-flow-mediated deformation mechanisms of HEAs and MG scan result in intermittent avalanches of defects moving through the material. Firstly, the theory of deformation mechanisms in MGs23,24,25, 48, 52 articulates that the atomic-scale heterogeneity due to short- or medium-range orders forms weak spots (the so-called shear-transformation zones24 or free volume25) and is responsible for the observed viscous-flow behavior25, 52 (further assuming that the weak spots follow a Newtonian flow behavior with an average viscosity25, 52). Under an applied stress, the sudden burst of the atomic motion of these weak spots results in a slip avalanche and forms new types of clusters/bonds. Our quantitative characterization of the bonding-charge density of the loosely-bonded spots captures the underlying atomic and electronic basis for the viscous-flow behavior of HEAs and MGs. Secondly, the elastic modulus, determined by not only the chemistry of the alloy, but also its atomic-level configuration,53 represents the limit of elastic deformation and can be used to describe the onset of plastic deformation. Therefore, a more adequate description of the electron redistribution response to applied normal and shear strains can provide the insight into the atomic-flow behavior of HEAs and MGs during deformation, as shown below.

Figure 2 presents the serration behavior (which is much more clearly seen in the plastic region if the temperature is higher21) of the BCC MoNbTaW HEA during compression (Fig. 2a), the scanning-electron-micrograph (SEM) image of a typical fracture surface (Fig. 2b), and the bonding-charge density isosurface of the investigated configurations with/without the applied strain (Fig. 2c–h). From these figures, we find that the mixture of alloying elements with different valence-electrons results in a dramatic change in the nature of chemical bonds (more information about the behavior of two other BCC HEAs, MoTaVW, and MoNbVW, can be found in Supplementary Information, Figs. S2 and S3). It is noted that there are 50% Mo in the atoms besides the clusters (i.e., Mo2W1Nb1), which are labeled in black letters and construct the 3rd shell of the center atom of the cluster and the glue atoms in the R2 configuration.33 The regions enriched in Mo yield the formation of loosely-bonded spots (weak spots), which is attributed to the smallest atomic size of Mo than that of Nb, Ta, and W in the MoNbTaW HEA and the formation of large lattice distortions. In particular, referring to the energy of O1 configurations, the variations of the total energies and the volumes of O2, R1, R2, and R3 are −3.760, −0.511, −0.106, and −0.694 KJ mole−1, 0.592, 0.800, 0.384, and 0.304 Å3 per supercell, respectively. These large lattice distortions caused by mixing the same group elements or the smaller atoms may result in the formation of weak spots and the enhancement of the total energy of the system. Moreover, attributed to the atomic-size misfit (lattice distortion) and valance electron variations, weak spots in the disordered configurations (R1–R3 in Fig. 2f–h) are characterized by the regions with a low bonding-charge density (Δρ). The higher density of Δρ also indicates a correspondingly-stronger chemical bond. It is evident that the bond strength between the Mo atom in the CN14 cluster and the glued Mo atom forms the weakest part of the structure, as illustrated in the R1–R3 configurations. In contrast, it is difficult to clearly define a weak point in the ordered O1 and O2 configurations (Fig. 2d–e); those chemical bonds appear homogeneous. These observations are in line with the hybrid Monte Carlo/Molecular Dynamic simulations that the relatively strong binding between elements from different transition metal groups of the periodic table and the relatively weak bonding between elements from the same group are formed.33, 54, 55 Under an applied normal/shear strain, the electron redistributions are dominated by the local atomic arrangements, resulting in a difference in the electron tomography as shown in Fig. 2c–h. For example, under the compressive and tensile shear deformation, the bonding electrons around the Mo atoms in O1 and O2 configurations present the opposite directions, which are highlighted by the dashed ellipses in Fig. 2d–e. Interestingly, under the normal compressive and tensile deformation, the ring-type bonds around Mo atoms in the O2 configuration transforms back to the octagon with half edges enriched of electrons, shown in Fig. 2e. Meanwhile, the dashed ellipses in Fig. 2f–h highlight the weak spots caused by the large lattice distortion near Mo atoms.

In addition to the BCC MoNbTaW HEA, the serration behavior of the BCC HfNbTiZr HEA, but now under tension, is shown in Fig. 4a, together with an SEM image of a fracture surface (Fig. 4b), with the bonding-charge density isosurface of the investigated configurations with/without the applied strains shown in Fig. 4c–g. Similarly, under the compressive and tensile shear deformation, the bonding electrons around the Ti atoms in the O1 configuration present the opposite directions, which are highlighted by the dashed ellipses in Fig. 4d. The diamond-type bonds around the Ti atoms in the O2 configuration is shrunk during the applied stress changed from the normal compression to the tension, shown in Fig. 4e. As for the random solutions, i.e., the R1 configuration, the region-enriched Zr atoms form the weak spot, which is attributed to the largest atomic size of Zr than those of Hf, Nb, and Ti in the HfNbTiZr HEA, and thus, to result in a large lattice distortion. Under the normal and compressive tension and the compressive shear, the vertical bonding electrons around Zr atoms are changed horizontally, which are highlighted by the dashed ellipses in Fig. 4f. Moreover, through combining the predicted yield strengths of various configurations into the stress–strain curve, the possible microstates related to their strains are addressed, which indicate that each configuration/microstate is stuck until the local stress exceeds a random local failure stress matching well with the weak-spots model.23

It is essential to mention that the weak spots may be the locations of dislocations, shear-transformation zones, shear bands, liquid-like sites, or other relatively weak regions in the real materials.23 It is understood that during plastic deformation, the pipe-up dislocations should contribute to the average strengthening behavior in the stress–strain curve while the local slips of various configurations/microstates distribute the kinks/steps, thus forming the serrations. Here, due to the larger BCC lattice parameter of Zr than those of Hf, Ti, and Nb, it is noted that it is the Zr atoms that are clustered together, which causes the formation of weak spots in the R1 configuration of the HfNbTiZr HEA. Similarly, in the HfNbTaZr, it has been observed that the short-range clustering (SRC) of a subset of atoms, enriched in Hf and Zr, takes place perpendicular to the <100> directions.56 Furthermore, the local structural disorder and distortions at the SRC were modeled by molecular dynamics relaxations.56 Relying on the information from the Δρ isosurfaces, one can evaluate the contributions of the configuration transition to the elastic/plastic properties, and deformation anisotropy (the details are listed as the A VR values in the Table S5, the directional modulus in Table S6, and Fig. S4 of the Supplementary Information). We find that an improper arrangement of atoms causes the large lattice distortion/misfit, which results in a mechanically-unattainable situation (i.e., negative values of elastic constants). That is the reason why the Δρ isosurface of the R2 configuration is unavailable in Fig. 4.

In order to reveal the contributions of various configurations to the serration behaviors, resulting in the stress fluctuations in the stress–strain curve, the plastic properties of each configuration are calculated by the crystal-plasticity finite-element (CPFE) calculations. As shown in Fig. 5a, the morphology of the utilized polycrystal structure represented by Poisson Voronoi tessellations contains 120 grains in a 4 × 4 × 4 mm3 cubic domain, which is dispersed with a free mesh of tetrahedral elements. It yields an average grain size of ~ 1 mm, matching well with the experimental observations in HfNbTiZr.37 The elastic constants predicted by the first-principles calculations (Table S3 and Table S4 of the Supplementary Information) and the empirical parameters (including the reference strain rate, the inverse strain-rate-sensitivity exponent n, and the initial hardening modulus, h 0) are directly applied in the present CPFE analysis. The initial value of the slip resistance is estimated through τ 0 = σ 0.2/M, where M is the Taylor factor of the order of 3.57 Since the saturation value of τ s will be larger than the initial value of τ 0 due to the strain hardening, the τ s/ τ 0 ratio is fixed to be 1.15. All those input parameters predicting the stress–strain curves of MoNbTaW and HfNbTiZr (Fig. 5b–c) are listed in Table S7. Under the same settings in the CPFE analysis, the various configurations mentioned in Fig. 5b–c present the atomic structure O1, O2, R2, and R3 of MoNbTaW and O2, R1, and R3 of HfNbTiZr dominated atomic, elastic, and plastic properties. It can also be seen that the configurational transitions yield the variations of elastic/plastic properties, thus contributing to the observed serration behavior of HEAs. It is essential to point out that the corresponding values of local properties computed from the configuration prior to the initial of shear are critical to obtain the correlation between the plastic activity and local properties.58 It is believed that those investigated configurations correspond to the various microstates of the plastic deformation and their stress fluctuations hint the serration behavior of the HEAs.

The polycrystal structure and the predicted stress–strain curves via the crystal plasticity finite-elements calculations. a The morphology of utilized polycrystal structure represented by Poisson Voronoi tessellations. b–c The predicted stress–strain curves of various configurations of MoNbTaW and HfZrTiNb, respectively

Lastly, to further understand the aforementioned serrated deformation of HEAs, we choose a well-studied MG, Vit1, as a case study. Based on our previous investigations of its atomic structures,39 the bonding-charge density of the various independent configurations generated by the AIMD calculations is shown in Fig. 6, illustrating the physical nature of amorphous bonding. It can be seen that loosely bonded spots and voids (positions highlighted by the dash ellipses) of Vit1 are mainly located at positions enriched with Zr atoms, resulting in a large lattice misfit, which matches the analysis of the BCC HfNbTiZr HEA (see Fig. 4). The strong chemical SROs connect via vertex-, edge-, face-, and intercross-shared atoms (the so-called glue atoms) to form the mid-range order through an efficient packing approach,39 noting that the SROs with various bonding electrons and lattice distortions (i.e., radial-bond stretching and angular-bond bending) would be critical signs identifying the weak spots. The networks of various SROs with weak spots (positions without Δρ in Fig. 6) form “core-shell”-type structures,25 in which the core parts (loosely bonded spots) follow a viscous-flow behavior.25, 52 It is believed that a slipping weak spot can trigger other weak spots to slip, creating what is referred to as a slip avalanche23 and resulting in a structural rejuvenation.14, 59 There are these events that are detected as steps of strain or stress drops in the stress–strain curves, i.e., serrations. It also presents that configuration transitions in the present work (see Figs. 3c–e, 2c–h, 4c–g, and 6) contribute to the observed serration behavior of HEAs and MGs. This viscous-flow-mediated deformation mechanism is consistent with the topological constraint theory,60 both of which show that the mechanical properties of this class of materials are dominated by the presence of weak spots or weak atomic constraints.

Bonding-charge-density isosurface (Δρ = 0.008 e-Å−3) of Vitreloy-1MG (Zr41Ti14Cu12.5Ni10Be22.5),Vit1. TheAM1—AM6 configurations are initially generated by running thousands of AIMD steps (time ≥ 10 ps) at 937, 1000, 1100, 1200, 1300, and 1500 K, respectively, and subsequently fully relaxed at 0 K. The yellow, green, pink, gray, and magenta colors are used to identify the Zr, Hf, Ti, Ni, and Be atoms, respectively. Soft and stiff zones related to free volume and clusters are clearly revealed by low and high values of Δρ. Plots of the Δρ isosurfaces are generated by the VESTA code65

In summary, we have utilized the cluster+glue-atom model integrated with EWF predicted from first-principles calculations to reveal a basis for the atomic structure-dominated mechanical properties and deformation mechanisms of two exemplary BCC HEAs. Specifically, we presented the power-law-scaled yield strength of HEAs and HE MGs based on the electron work function (EWF). Further, using the bonding-charge density, which captures the electron redistributions induced by the lattice distortion and elastic deformation, we provided a groundbreaking insight into the nature of loosely bonded spots in these classes of materials. In particular, the relatively strong binding between elements from different transition metal groups of the periodic table and the relatively weak bonding between elements from the same group are formed. The CPFE analysis further validate that the configurational transitions yield the variations of elastic/plastic properties, thus contributing to the observed serration behavior of HEAs. It is presented that the simultaneous existences of strongly bonded clusters and weak spots created by nearby glue atoms give rise to a viscous-flow-mediated deformation mechanism in HEAs and MGs, resulting in the observed intermittent avalanches of defects moving through the material.

Methods

Ab initio calculations

All calculations in the current work are carried out using the Vienna ab initio simulation package.61, 62 The projector augmented wave functions for the electron–ion interaction and the generalized gradient approximations (GGA-PW91) for the exchange-correlation functional are applied, respectively.63 The wave functions are sampled on Г-centered Monkhorst-Pack grids of 7 × 7 × 7 for the HEAs supercells with 16 atoms and 1 × 1 × 1 for the Vit1 MG supercells with 200 atoms, respectively. The plane-wave cutoff energy (ENCUT) is set automatically to the maximal energy (ENMAX) of each element and the energy-convergence criterion of the electronic self-consistency is 10−6 eV atom−1. While the structures are fully relaxed by the Methfessel-Paxton technique,64 the final static total-energy calculations are performed by the tetrahedron method incorporating a Blӧchl correction.64 As for the AIMD calculations, a canonical ensemble with a Nosé Thermostat for the temperature control and a velocity Verlet algorithm with a time step of 3fs are applied. The bonding-charge density calculated through the charge-density difference for the fully relaxed structure with and without the self-consistent calculations. The isosurface structures with different values of Δρ are generated, using the Visualization for Electronic and Structural Analysis (VESTA) code.65 The EWFs of HEAs and Vit1 MG are calculated by the HD model41 expressed as

where α is an empirical parameter, being either unity for most metals or equal to 0.86 for alkali metals; r s = 1.3882(M/Zρ)1/3 is the effective radius of the electronic volume (normalized by Bohr’s radius, a 0 = 0.529 Å); and EF is the Fermi energy calculated by the free-electron gas model [EF = 50.03(rs/a0)−2] (ev) from bulk properties (i.e., density, ρ, valence, Z, and atomic mass, M). Full data sets for the current calculations are also reported in our previous work39, 44 and elsewhere.41

Crystal-plasticity finite-element (CPFE) analysis

The CPFE analysis based on the work of Asaro and Needleman66 and Peirce et al.67 is utilized, in which the crystal orientation and the activated slip systems are taken into account. The total deformation gradient, F, of a finite strain can be expressed by polar decomposition

where F e represents the elastic-deformation gradient composed of the elastic stretching and rigid body rotation of the configuration, and F p denotes the plastic shear due to slip. The plastic velocity gradient, L p, is defined as:

where \({\dot \gamma ^\alpha }\), s α, and n α are the shear strain rate, the slip-direction vector, and the normal vector to the slip plane of any given slip system, α, respectively. N is the number of the active slip systems.

The shear strain rate, \({\dot \gamma ^\alpha }\), of the αth slip system is determined by a simple rate-dependent power-law relation proposed by Hutchinson68:

where \(\dot \gamma _0^\alpha \) is the reference strain rate, τ α is the resolved shear stress, g α is the slip-system strength or resistance to shear, and n is the inverse strain-rate sensitivity exponent. Attributing to the accumulation of dislocations, the strain hardening will occur, which is characterized by the evolution of the rate of change of yield strengths:

where h αβ is the matrix of slip-hardening moduli. The hardening model of Asaro and Needleman,66 Peirce et al.67 is used here, and the self-hardening moduli is expressed as:

where h 0 is the initial hardening modulus, τ 0 the initial value of the slip resistance, τ s the saturation value, and γ the Taylor cumulative shear strain on the all activated slip systems, which is given by

The latent-hardening moduli are given by

where q is the latent hardening parameter.

Data availability

Correspondence and requests for data and materials should be addressed to W.Y.W. (wywang@nwpu.edu.cn) and the other corresponding authors.

References

Yeh, J. W. et al. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 6, 299–303 (2004).

Li, Z. et al. Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strength-ductility trade-off. Nature 534, 227–230 (2016).

Gludovatz, B. et al. A fracture-resistant high-entropy alloy for cryogenic applications. Science 345, 1153–1158 (2014).

Zou, Y., Ma, H. & Spolenak, R. Ultrastrong ductile and stable high-entropy alloys at small scales. Nat. Commun. 6, 7748 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 61, 1–93 (2014).

Zhang, Z. et al. Nanoscale origins of the damage tolerance of the high-entropy alloy CrMnFeCoNi. Nat. Commun. 6, 10143 (2015).

Senkov, O. N., Miller, J. D., Miracle, D. B. & Woodward, C. Accelerated exploration of multi-principal element alloys with solid solution phases. Nat. Commun. 6, 6529 (2015).

Troparevsky, M. C. et al. Criteria for predicting the formation of single-phase high-entropy alloys. Phys. Rev. X. 5, 011041 (2015).

Guo, S. & Liu, C. T. Phase stability in high entropy alloys: formation of solid-solution phase or amorphous phase. Prog. Nat. Sci. 21, 433–446 (2011).

Santodonato, L. J. et al. Deviation from high-entropy configurations in the atomic distributions of a multi-principal-element alloy. Nat. Commun. 6, 5964 (2015).

Poletti, M. G. & Battezzati, L. Electronic and thermodynamic criteria for the occurrence of high entropy alloys in metallic systems. Acta Mater. 75, 297–306 (2014).

Sammonds, P. Deformation dynamics: plasticity goes supercriticial. Nat. Mater. 4, 425–426 (2005).

Egami, T. Atomic level stresses. Prog. Mater. Sci. 56, 637–653 (2011).

Ma, E. Tuning order in disorder. Nat. Mater. 14, 547–552 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Influence of chemical disorder on energy dissipation and defect evolution in concentrated solid solution alloys. Nat. Commun. 6, 8736 (2015).

Carroll, R. et al. Experiments and model for serration statistics in low-entropy, medium-entropy, and high-entropy alloys. Sci. Rep. 5, 16997 (2015).

Feng, R. et al. Design of light-weight high-entropy alloys. Entropy 18, 333 (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. Inherent structure length in metallic glasses: simplicity behind complexity. Sci. Rep. 5, 12137 (2015).

Wang, W. Y. et al. Power law scaled hardness of Mn strengthened nanocrystalline AlMn non-equilibrium solid solutions. Scripta Mater. 120, 31–36 (2016).

Sheng, H. W. et al. Atomic packing and short-to-medium-range order in metallic glasses. Nature 439, 419–425 (2006).

Antonaglia, J. et al. Temperature effects on deformation and serration behavior of high-entropy alloys (HEAs). JOM 66, 2002–2008 (2014).

Qiao, J., Jia, H. & Liaw, P. K. Metallic glass matrix composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 100, 1–69 (2016).

Antonaglia, J. et al. Tuned critical avalanche scaling in bulk metallic glasses. Sci. Rep. 4, 4382 (2014).

Schuh, C. A. & Lund, A. C. Atomistic basis for the plastic yield criterion of metallic glass. Nat. Mater. 2, 449–452 (2003).

Ye, J. C. et al. Atomistic free-volume zones and inelastic deformation of metallic glasses. Nat. Mater. 9, 619–623 (2010).

Ma, D., Stoica, A. D. & Wang, X. L. Power-law scaling and fractal nature of medium-range order in metallic glasses. Nat. Mater. 8, 30–34 (2009).

Nakashima, P. N. H., Smith, A. E., Etheridge, J. & Muddle, B. C. The bonding electron density in aluminum. Science 331, 1583–1586 (2011).

Ogata, S., Li, J. & Yip, S. Ideal pure shear strength of aluminum and copper. Science 298, 807–811 (2002).

Hong, H. L., Wang, Q., Dong, C. & Liaw, P. K. Understanding the Cu-Zn brass alloys using a short-range-order cluster model: significance of specific compositions of industrial alloys. Sci. Rep. 4, 7065 (2014).

Pang, C. et al. β Zr-Nb-Ti-Mo-Sn alloys with low Young’s modulus and low magnetic susceptibility optimized via a cluster-plus-glue-atom model. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 626, 369–374 (2015).

Wang, W. Y. et al. Effect of composition on atomic structure, diffusivity and viscosity of liquid Al-Zr alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 43, 3471–3480 (2012).

Gao, M. C., Yeh, J. –W., Liaw, P. K., Zhang, Y. High-entropy alloys: fundamentals and applications (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Wang, W. Y. et al. Revealing the microstates of body-centered-cubic (BCC) equiatomic high entropy alloys. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 38 (2017). doi:10.1007/s11669-017-0565-4.

Berry, R. S. & Smirnov, B. M. Configurational transitions in processes involving metal clusters. Phys. Rep. 527, 205–250 (2013).

Senkov, O. N. et al. Refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 18, 1758–1765 (2010).

Senkov, O. N., Wilks, G. B., Scott, J. M. & Miracle, D. B. Mechanical properties of Nb25Mo25Ta25W25 and V20Nb20Mo20Ta20W20 refractory high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 19, 698–706 (2011).

Wu, Y. D. et al. A refractory Hf25Nb25Ti25Zr25 high-entropy alloy with excellent structural stability and tensile properties. Mater. Lett. 130, 277–280 (2014).

Hirata, A. et al. Geometric frustration of icosahedron in metallic glasses. Science 341, 376–379 (2013).

Hui, X. et al. Atomic structure of Zr41.2Ti13.8Cu12.5Ni10Be22.5 bulk metallic glass alloy. Acta Mater. 57, 376–391 (2009).

Xu, W. et al. Evidence of liquid-liquid transition in glass-forming La50Al35Ni15 melt above liquidus temperature. Nat. Commun. 6, 7696 (2015).

Halas, S. & Durakiewicz, T. Work functions of elements expressed in terms of the Fermi energy and the density of free electrons. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 10, 10815 (1998).

Hua, G. & Li, D. The correlation between the electron work function and yield strength of metals. Phys. Status Solidi B 249, 1517–1520 (2012).

Rahemi, R. & Li, D. Variation in electron work function with temperature and its effect on the Young’s modulus of metals. Scripta Mater. 99, 41–44 (2015).

Wang, Y., Wang, W. Y., Chen, L.-Q. & Liu, Z.-K. Bonding charge density from atomic perturbations. J. Comput. Chem. 36, 1008–1014 (2015).

Nagel, S. R. & Tauc, J. Nearly-free-electron approach to the theory of metallic glass alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 35, 380–383 (1975).

Rose, J. H., Ferrante, J. & Smith, J. R. Universal binding energy curves for metals and bimetallic interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 47, 675–678 (1981).

Banerjea, A. & Smith, J. R. Origins of the universal binding-energy relation. Phys. Rev. B 37, 6632–6645 (1988).

Lu, J., Ravichandran, G. & Johnson, W. L. Deformation behavior of the Zr41.2Ti13.8Cu12.5Ni10Be22.5 bulk metallic glass over a wide range of strain-rates and temperatures. Acta Mater. 51, 3429–3443 (2003).

Yu, Q. et al. Strong crystal size effect on deformation twinning. Nature 463, 335–338 (2010).

Liu, B.-Y. et al. Twinning-like lattice reorientation without a crystallographic twinning plane. Nat. Commun. 5, 3297 (2014).

Gilman, J. Electronic Basis of the Strength of Materials (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Wang, Z., Sun, B. A., Bai, H. Y. & Wang, W. H. Evolution of hidden localized flow during glass-to-liquid transition in metallic glass. Nat. Commun. 5, 5823 (2014).

Cheng, Y. Q. & Ma, E. Configurational dependence of elastic modulus of metallic glass. Phys. Rev. B 80, 064104 (2009).

Widom, M., Huhn, W. P., Maiti, S. & Steurer, W. Hybrid monte carlo/molecular dynamics simulation of a refractory metal high entropy alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 45A, 196–200 (2013).

Widom, M. Prediction of structure and phase transformations. in High-Entropy Alloys: Fundamentals and Applications (eds Gao, M. C., et al.) 267–298 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Maiti, S. & Steurer, W. Structural-disorder and its effect on mechanical properties in single-phase TaNbHfZr high-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 106, 87–97 (2016).

Mecking, H., Kocks, U. F. & Hartig, C. Taylor factors in materials with many deformation modes. Scripta Mater. 35, 465–471 (1996).

Patinet, S., Vandembroucq, D. & Falk, M. L. Connecting local yield stresses with plastic activity in amorphous solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 045501 (2016).

Ketov, S. V. et al. Rejuvenation of metallic glasses by non-affine thermal strain. Nature 524, 200–203 (2015).

Bauchy, M. et al. Rigidity transition in materials: hardness is driven by weak atomic constraints. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 125502 (2015).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6671 (1992).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616–3621 (1989).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Asaro, R. J. & Needleman, A. Overview no. 42 texture development and strain hardening in rate dependent polycrystals. Acta Metall. 33, 923–953 (1985).

Peirce, D., Asaro, R. J. & Needleman, A. Material rate dependence and localized deformation in crystalline solids. Acta Metall. 31, 1951–1976 (1983).

Hutchinson, J. Bounds and self-consistent estimates for creep of polycrystalline materials. Proc. R. Soc. London A Math. Phys. Sci. 348, 101–127 (1976).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the U.S. Army Research Laboratory (Project No. W911NF-08-2-0084), the United States National Science Foundation (Grant DMR-1006557), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 51690163, 50871013, 51271018, 51271151, and 51571161). W.Y.W. and J.S.L. acknowledge the support from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities in China (G2016KY0302) and the Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi province of China (2016JQ5003). Work by ONS was supported through the Air Force on-site contract FA8650-10-5226 managed by UES, Inc., Dayton, Ohio. X.X. and P.K.L. would like to acknowledge the Department of Energy, Office of Fossil Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory (DE-FE-0008855, DE-FE-0024054, and DE-FE-0011194), the U.S. Army Research Office project (W911NF-13-1-0438), the National Science Foundation (CMMI-1100080 and DMR-1611180), and the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 105-2221-E-007-017-MY3). K.A.D. and P.K.L. thank the support from the DE-FE-0011194 project. First-principles calculations were carried out on the LION clusters at the Pennsylvania State University supported by the Materials Simulation Center and the Institute for CyberScience. Calculations were also carried out on the CyberStar cluster funded by NSF through Grant OCI-0821527 and the XSEDE clusters supported by NSF through Grant ACI-1053575.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Y.W., S.L.S., and Y.W. carried out the first-principles calculations. Y.D.W., X.D.H., and O.N.S. performed the experimental measurements. F.B.H. and J.S.L. conducted the finite-elements calculations. X.X., P.K.L., and K.A.D. contributed to the review of the HEA data. Z.K.L., L.J.K, and K.A.D. designed the current research work led by PSU and ARL. All authors contributed to the data analysis, interpretation of results, and the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, W.Y., Shang, S.L., Wang, Y. et al. Atomic and electronic basis for the serrations of refractory high-entropy alloys. npj Comput Mater 3, 23 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-017-0024-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-017-0024-0

This article is cited by

-

Elaborating strengthen mechanism of Pt–Ir solid solution superalloy at finite temperature

Rare Metals (2024)

-

Evading dynamic strength and ductility trade-off in a high-entropy alloy via local chemical ordering

Communications Materials (2023)

-

The helium-vacancy complexes and helium bubbles formation mechanism in chromium: a comprehensive first-principle study

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

-

Phase prediction for high-entropy alloys using generative adversarial network and active learning based on small datasets

Science China Technological Sciences (2023)

-

Electronic structures and strengthening mechanisms of superhard high-entropy diborides

Rare Metals (2023)