Abstract

Mounting evidence suggests that terrestrialization of plants started in streptophyte green algae, favoured by their dual existence in freshwater and subaerial/terrestrial environments. Here, we present the genomes of Mesostigma viride and Chlorokybus atmophyticus, two sister taxa in the earliest-diverging clade of streptophyte algae dwelling in freshwater and subaerial/terrestrial environments, respectively. We provide evidence that the common ancestor of M. viride and C. atmophyticus (and thus of streptophytes) had already developed traits associated with a subaerial/terrestrial environment, such as embryophyte-type photorespiration, canonical plant phytochrome, several phytohormones and transcription factors involved in responses to environmental stresses, and evolution of cellulose synthase and cellulose synthase-like genes characteristic of embryophytes. Both genomes differed markedly in genome size and structure, and in gene family composition, revealing their dynamic nature, presumably in response to adaptations to their contrasting environments. The ancestor of M. viride possibly lost several genomic traits associated with a subaerial/terrestrial environment following transition to a freshwater habitat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Transition to a terrestrial environment, termed terrestrialization, is generally regarded as a pivotal event in the evolution and diversification of land plant flora1. Extant green plants (Viridiplantae) can be subdivided into two lineages, Chlorophyta (most of the green algae) and Streptophyta (embryophytes and their closest algal relatives, a grade collectively known as streptophyte algae2). There is now compelling evidence that adaptation to subaerial/terrestrial habitats is a feature of streptophyte algae, arising from their dual existence in freshwater and subaerial/terrestrial environments throughout their evolutionary history. Recent transcriptomic and genomic studies have shown that the molecular toolkit for life in a terrestrial environment was already present in streptophyte algae3. Homologues of genes once thought to be restricted to embryophytes are now being detected in streptophyte algae. Examples include those involved in symbiotic or pathogenic interactions with soil microbes4, phytohormone signalling5,6,7,8, desiccation/stress9, plastid/nucleus retrograde signalling10,11 and cell wall metabolism12. Importantly, many transcription factors (TFs) thought to be specific to embryophytes originated in streptophyte algae and also substantially expanded there13. These findings raise exciting questions about the functional role of embryophyte-like genes in streptophyte algae.

In phylogenomic analyses, the earliest-diverging streptophyte algae are represented by a clade comprising two monospecific genera, Mesostigma and Chlorokybus14,15,16,17. Both are structurally simple but differ in their cellular organization, life history and type of habitat18. Mesostigma viride is a scale-covered flagellate with an eyespot that reproduces by binary division at the flagellate stage (Fig. 1b). Chlorokybus atmophyticus consists of sarcinoid cell packets where each cell has its own cell wall, occasionally producing biflagellate, scaly zoospores (Fig. 1b). Importantly, M. viride is found in the benthos of small, shallow ponds whereas C. atmophyticus is a subaerial/terrestrial alga that occurs among bryophytes, on soil and on stones.

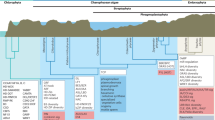

a, This phylogenetic tree was constructed by maximum likelihood based on the concatenated sequences of single-copy genes, while species-specific gene duplicates were excluded from the analysis. A k-means clustering of gene families based on the gene abundance of each species is shown in the right-hand panel; each column represents a family and each row represents one species. b, Differential interference contrast micrographs showing M. viride (left) and C. atmophyticus (right). c, Venn diagrams showing the number of gene families shared among M. viride, C. atmophyticus and a representative rhodophyte, streptophyte or chlorophyte. d, Significant increases and decreases in gene families; filled red circles, triangles and rhombi denote function enrichment of significant increased gene families in the KEGG pathway, while empty symbols denote function enrichment of significant decreased gene families in the KEGG pathway. Details of these functions are shown in the right-hand panel. e, Percentages of total proteins found in both algae and embryophytes (red), proteins shared among algae (purple) and proteins shared among embryophytes (green) based on the classification given in Orthofinder. f, Principal component analysis of the type and number of Pfam domains.

Previous analyses of two streptophyte algal genomes, Klebsormidium nitens6 and Chara braunii7, have not only revealed embryophyte-like genomic traits with gains and expansions of respective genes/gene families in both taxa, but also loss of genes involved in responses to abiotic stresses that prevail in a terrestrial environment, in the aquatic (freshwater) C. braunii (K. nitens thrives in a subaerial/terrestrial environment). The draft genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus reported here allowed us to address two questions important for plant terrestrialization: (1) did the common ancestor of streptophytes already display embryophyte-like genomic traits that would be indicative for adaptation to a terrestrial environment; and (2) how do the genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus differ from each other in light of previous genome studies on two streptophyte algae that occur in contrasting environments (subaerial/terrestrial and aquatic) but belong to different streptophyte classes (Klebsormidiophyceae and Charophyceae)?

Results

Genome sequencing, genome characteristics and phylogenetic analysis

A total of 245 Gb (746.86X) (M. viride) and 66 Gb (775.68X) (C. atmophyticus) raw data were generated using Illumina technology (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Based on k-mer depth distribution analyses, the nuclear genome sizes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus were estimated to be 329 and 85 Mb, respectively (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Approximately 85.4% (281 Mb) and 87.0% (74 Mb) of the genomes were de novo assembled, consisting of 6,924 scaffolds with a minimum contig length needed to cover 50% of the genome (N50) of 113,221 base pairs (bp) for M. viride, and 3,836 scaffolds with N50 of 752,385 bp for C. atmophyticus (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). The distributions of genomic copy content (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4) and BUSCO score (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8) suggested no contamination and good assembly quality. Moreover, 93.8% (M. viride) and 99.4% (C. atmophyticus) of de novo assembled transcripts were aligned to the assembled genome. (Supplementary Tables 9 and 10). Both genomes have substantial repeat components (38.7 and 31.3%, respectively; Supplementary Tables 11 and 12). By combining homologue-based, ab initio and transcriptome-based approaches, 9,300 gene models were predicted for both genomes (Supplementary Tables 13 and 14 and Supplementary Fig. 5). In total, 9,198 and 9,066 predicted coding sequences, respectively, were supported by sequenced transcripts, indicating the high accuracy of gene predictions (Supplementary Table 15). Complete coverage of genes involved in transcription, translation and DNA synthesis was also obtained (Supplementary Table 16).

A phylogenetic analysis of 16 genomes from Rhodophyta, Glaucophyta, Chlorophyta, streptophyte algae and embryophytes, based on a concatenated amino acid sequence alignment of 375 orthologues of single-copy genes, confirmed the sister relationship between Mesostigma and Chlorokybus and also supported previous reports that M. viride and C. atmophyticus constitute the earliest-diverging lineage of extant streptophytes15,16,17 (Fig. 1a).

Comparative genomics

Mesostigma viride, C. atmophyticus and K. nitens shared 3,683 gene families (Fig. 1c), which comprised 4,423 genes in M. viride and 4,210 in C. atmophyticus. Interestingly, 3,639 and 2,470 gene families were found exclusive to M. viride and C. atmophyticus, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 17). We also considered homologues of the identified genes in the red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae, and in Micromonas commoda (Chlorophyta). M. viride and C. atmophyticus share about 2,000–2,500 gene families with C. merolae and 3,300–4,100 with M. commoda, reflecting their phylogenetic relationships (Fig. 1c).

To explore significant increases or decreases in gene families in Rhodophyta, Chlorophyta and streptophyte algae, the gene family content of five representative genomes in each of the three clades (a total of 15 genomes) was compared. The most significant increases in gene families occurred from Rhodophyta to streptophyte algae (225) and to Chlorophyta (188), respectively, and referred mainly to plant hormone signal transduction, plant–pathogen interaction, photosynthesis and starch and sucrose metabolism (Fig. 1d). Conversely, significant decreases in gene families were observed from the two lineages of Viridiplantae to Rhodophyta (41 and 44, respectively), mainly corresponding to purine metabolism, endocytosis and pentose and glucuronate interconversions. In comparison, significant increases and decreases in gene families between streptophyte algae and Chlorophyta were more modest: the main increases for gene families in streptophyte algae were in plant hormone signal transduction, plant–pathogen interactions and TFs, whereas the main decreases for gene families were in purine and pyrimidine metabolism, DNA replication and O-glycan biosynthesis.

In addition, our analysis revealed a higher percentage of embryophyte genes in M. viride and C. atmophyticus compared to Chlorophyta, but lower than in K. nitens (Fig. 1e). In addition to gene families, the total number of conserved Pfam domains in Rhodophyta, Chlorophyta and Streptophyta was subjected to principal component analysis, which showed distinct patterns of functional diversification indicating evolutionary diversification (Fig. 1f). Overall, these results suggest that the genomes of early-diverging streptophyte algae already contained archetypal genes that typically exist in modern embryophytes.

TFs and phytohormones in early-diverging Streptophyta

Out of 114 types of TFs/transcription regulators (TRs) analysed, 72 (M. viride) and 80 (C. atmophyticus) TFs/TRs were identified in the two genomes (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 18), of which most are associated with abiotic stress responses, development and plant–pathogen interactions in embryophytes. TF/TR genes accounted for 3.31% of the total number of protein-coding genes in the M. viride genome and 4.47% in the C. atmophyticus genome, similar to the percentages in bryophytes (4.68%) and angiosperms (~5%). A combination of HMMER and phylogenetic analyses (for details see Methods) revealed putative gains of several TF/TR genes in the common ancestor of streptophytes, and differential losses of some of these genes in M. viride and/or C. atmophyticus (Fig. 2b). We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that the lower TF/TR numbers in M. viride relate to lack of representation in the genome assembly, although we aimed to compensate for this by adding data from our deeply sequenced transcriptome. Among the gains, the homeodomain–leucine zipper (HD-ZIP) family members are unique to plants and have diverse functions in growth and development, mostly related to stress responses19. Of the four known classes (I–IV) of HD-ZIPs, gene classes I–III were found in C. atmophyticus but were missing in M. viride (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 6). M. viride displayed one gene that was positioned near the base of the HD-ZIPIV clade in phylogenetic analyses with moderate support and a long branch (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, this gene contained neither a HD nor a START domain, suggesting that it represents either an ancestral pre-HD-ZIP_IV or a degenerated gene with domain, and perhaps functional, loss. Other TF/TR genes that apparently originated in the common ancestor of streptophytes, such as auxin response factors (ARF) proto-C-type (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8), SHI-related sequence (SRS), Trihelix TF family (Trihelix), growth-regulating factors (GRF), LUG transcriptional co-repressor (LEUNIG) and HD-PLINC homeodomain plant zinc finger (HD-PLINC), have also been implicated in the regulation of growth and development in response to light, salt and pathogen stresses in embryophytes20,21,22,23,24,25. In addition to gains, nine TF/TR gene families expanded by a minimum of threefold in M. viride/C. atmophyticus compared to non-streptophytes (Supplementary Table 18), and five of those (C2C2_CO-like, DDT, PcG_FIE, PcG_MSI, PSEUDO-ARR-B) had a minimum of 50% more members in C. atmophyticus than in M. viride, all involved in responses to abiotic and biotic stresses in embryophytes. Overall, our results correlate well with a recent analysis using transcriptome data13, except that we extend the origin of HD-Zip genes I–III, ARF and HD-KNOX1 (Knotted-like homebox class I) to the common ancestor of streptophytes rather than a later origin.

a, Using a HMMER approach for the respective genomes, the numbers of TFs and TRs were identified using the TAPscan database v.2 (for details see Methods). b, Illustrative phylogenetic representation of the predicted gain (green) and loss (orange) of plant TFs in streptophyte algae. c, Presence/absence of the main phytohormone signalling pathways deduced from the genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus. Coloured boxes indicate the presence of genes in the pathways, white boxes their absence. All searches were done using HMM (1 × 10–10). Purple-lined ellipses denote genes identified in M. viride but not in C. atmophyticus, while the green-lined ellipse denotes a gene identified in C. atmophyticus but not in M. viride. d, The maximum-likelihood method was used to draw the phylogenetic tree of the PIN and PIN-related homologues to understand their origin among Streptophyta.

Next, we explored phytohormone biosynthesis and transduction pathway-related genes (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Tables 19 and 20). By employing a HMMER search, an almost intact abscisic acid (ABA) signalling pathway was detected although the ABA receptor PYL was absent, the latter finding consistent with earlier reports on K. nitens6 and C. braunii7. Homologues of the Abscisic acid responsive element-binding protein (AREB)/Abscisic acid responsive element-binding factors (ABFs) TFs involved in ABA signalling under drought stress in embyophytes were also detected in both genomes26. Genes for the complete signalling pathway of cytokinin (CK27) were identified in both genomes. The second, conserved, two-component signalling pathway (in addition to CK), that of ethylene, was also almost completely represented except for the TF EIN3/EIL.

Both M. viride and C. atmophyticus were found to encode various transporter proteins and ATP-binding cassette B transporters that could potentially participate in auxin transport (Supplementary Table 21). However, no auxin receptor (TIR) was found in either genome (Fig. 2c). Notably, PIN, an important auxin efflux carrier involved in the transport of auxin between cells, was detected in the M. viride genome but not in C. atmophyticus. We found a step-by-step gain in motifs corresponding to PIN (Fig. 2d). Neither M. viride nor C. atmophyticus encodes the auxin signal transduction components AUX/IAA1, SAUR and GH3 (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, both genomes lacked auxin biosynthesis genes such as tryptophan-aminotransferase (TAA) and nitrilase, while YUCCA could be identified in M. viride only (Supplementary Table 19 and Supplementary Fig. 9).

Both organisms could synthesize most of the jasmonic acid (JA)-precursor OPDA but lacked OPR3, indicating that the JA biosynthetic pathway may exist in early-diverging streptophyte algae (Supplementary Table 19). Concomitantly, both C. atmophyticus and M. viride lacked the complete JA and strigolactone (SL)) signalling components and the respective hormone receptors (Fig. 2c). Gibberellic acid (GA) receptors (GID1 and GID2) and signalling components (DELLA, PIL1 and PIF) were also absent (for the PIF and bHLH phylogeny, see Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). Some components of the salicylic acid (SA) pathway (CUL3 and TGA) were, however, detected (for TGA see Supplementary Figs 12 and 13). Finally, we analysed sequence conservation of phytohormone receptor genes among representative algal lineages (Extended Data Fig. 2). The results showed that, although the genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus encode some phytohormone-related receptors, they are not as well conserved as in embryophytes. In general, our results are in accordance with previous genome analyses of later-diverging streptophyte algae and liverworts5,6,7,8 which suggested that F-box-mediated phytohormone signalling pathways (auxin, JA, GA, SL) evolved in the embryophyte ancestor, whereas two-component system phytohormone signalling (CK, ethylene) evolved much earlier, having been present in the common ancestor of streptophytes (this study). Furthermore, some components of both F-box-mediated (auxin, SA) and other phytohormone signalling pathways (ABA, brassinosteroid (BR)) are ancient and presumably originated in the common ancestor of streptophytes—for example, PIN, C-type ARF and TGA (this study).

Analysis of cell wall metabolism, evidence of sexual reproduction and analysis of flagellar genes

In total, 81 and 100 putative carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) and 20 and 22 additional proteins containing putative carbohydrate-binding modules were identified in M. viride and C. atmophyticus, respectively (Supplementary Table 22). Both the numbers of glycosyl hydrolases (GH) and glycosyltransferases (GT) were higher in C. atmophyticus than in M. viride, but in the same range as those found in unicellular red algae (32/54) or early-diverging Chlorophyta28 (52/57/77). Compared to previous transcriptome-based analyses12, the differences in numbers of GTs between M. viride and C. atmophyticus were not as large, suggesting that hidden life history stages in M. viride (zygotes?) may contribute GTs to its overall genomic GT complement. The largest GT families found were GT2 (N-glycosylation and cell wall biosynthesis), GT5 (starch synthases) and GT35 (glycogen/starch phosphorylases). However, certain differences were also encountered: GT 77 (involved in rhamnogalacturonan-II synthesis) had more family members in C. atmophyticus29, while GT 41 (β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase) was more prominent in M. viride. Four GT families were present in only M. viride or C. atmophyticus, among them GT8 (in C. atmophyticus), a large family of glycosyltransferases in embryophytes, of which some members have been implicated in responses to abiotic stress30.

To gain further insight into the evolution of proteins involved in cell wall biosynthesis, we analysed the phylogeny of representative enzymes. Our analyses revealed the presence of three putative cellulose synthase-like (CSL) enzymes (CSLA/CSLC-like), but the absence of cellulose synthase (CESA), in M. viride (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 23). However, three CESA/CSLD-like homologues were identified in the C. atmophyticus genome and showed high similarity to the respective genes in embryophytes. C. atmophyticus displayed two additional CSL enzymes that apparently originated by a gene duplication in the common ancestor of M. viride and C. atmophyticus (Fig. 3a). Our phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that CESA and CSL proteins diverged into two clades, their origin apparently dating back to the ancestor of the Archaeplastida31. The first clade encompassed CESA and CLSB, -D, -E, -G and -H, the second clade CSLA, CSLC and a paraphyletic set of genes (CSLA/CSLC-like) that includes five CSL genes from M. viride and C. atmophyticus. Mapping CESA and CSLs on a simplified phylogenetic tree of Archaeplastida pinpoints putative gains and losses of these enzymes on different branches (Fig. 3b).

a, Phylogenetic tree of CESA and CSL (GT2 family). The tree was constructed using the maximum-likelihood method. b, Left: summary of the gains and losses of cell wall biosynthetic genes mapped on the phylogenetic tree. Right: copy number of the respective cell wall biosynthetic genes. HG, homogalacturonan; XGA, xylogalacturonan; RGI and RGII, rhamnogalacturonan I and II; AGP, arabinogalactan protein; GSL, glucan synthase-like.

To adapt to rapidly changing environments, early-diverging streptophytes would be expected to actively conduct reassembly and degradation of cell wall components to enhance the flexibility of the cell wall during osmotic stress. Enzymes in 14 families of glycoside hydrolases (GH5-10, -12, -26, -44, -45, -48, -51, -61 and -74) are known to degrade cellulose in embryophytes32. Not surprisingly, cellulases were not detected in the M. viride genome, which lacks CESA; however, in C. atmophyticus cellulases were present (Table 1). Interestingly, a majority of the genes involved in mannan and xylan metabolism, such as mannanases, mannosidase and xylosidase, were detected in M. viride whereas C. atmophyticus lacks those enzymes. M. viride and C. atmophyticus also lack xyloglucan- and xylan-degrading enzymes, as well as most of the pectin lyases (Table 1).

Some of the differences in the composition of the cell surface between M. viride and C. atmophyticus could be related to variation in their cellular organization, life history and habitats. To check whether ‘cryptic sex’ may exist in early-diverging streptophyte algae, we searched the M. viride and C. atmophyticus genomes for meiosis-specific (11) and meiosis-related genes (40) by hidden Markov model (HMM) and BLAST (Supplementary Table 24). We found that the core-set of meiosis-specific genes (10) was present in C. atmophyticus whereas the M. viride genome lacked MSH5, REC8 and RED1 (Supplementary Table 24); the absence of the latter is puzzling, but not without precedent33. M. viride reproduces vegetatively by binary division of the flagellate cell, whereas C. atmophyticus forms scale-covered zoospores during asexual reproduction. A comparative analysis of the complement of flagellar genes in their genomes, using a stringent reciprocal-best-BLAST-hits analysis of 397 Chlamydomonas flagellar proteins as query34, detected 204 flagellar proteins in M. viride and 192 in C. atmophyticus (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 25). Non-flagellate organisms lack the majority of radial spoke, as well as central pair proteins, many of the outer and inner dynein arm proteins and all intraflagellar transport proteins (IFTs), as well as dynein heavy-chain proteins. Surprisingly, in both M. viride and C. atmophyticus (flagella covered by scales), we could identify only a few IFTs whereas K. nitens displayed the full set (12 IFTs) (Extended Data Fig. 3).

The phylogenomic tree (left) was constructed using a maximum-likelihood method based on the concatenated sequences of single-copy genes from different representative algal lineages. The horizontal bar chart (middle) denotes the number of putative orthologues to 398 Chlamydomonas conserved flagellar proteins; the pink horizontal bar represents the number of structure-related flagellar genes (individual genes listed at the top of the right panel), while the green area represents the number of flagella-associated genes. The right panel shows the key structure-related flagellar proteins in six categories. The circle size is proportional to the copy number of putative orthologous genes found in the respective species.

Evolutionary analysis of elongation factor-1α and phytochromes

The elongation factor EF-1α is responsible for the selection and binding of aminoacyl-transfer RNA to the A-site (acceptor site) of the ribosome. It is substituted by elongation factor-like (EF-like) proteins in many eukaryotes35. Intriguingly, we found that the M. viride genome encodes both EF-1α and EF-like genes (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 4), contradicting earlier studies that reported only the presence of EF-like genes in M. viride and no EF-1α (ref. 36).

a, Maximum likelihood was used to infer the phylogenetic tree. Right: representative EF-1α and EF-like motifs, from red algae to embryophytes. ‘Other Streptophyta’ represents C. atmophyticus, Klebsormidiophyceae, Coleochaetophyceae, Charophyceae and Zygnematophyceae. b, Left: simplified phylogenic tree of phytochromes across cyanobacteria, glaucophytes, prasinophytes and streptophyte algae is shown. Right: complete domain structures of the phytochrome proteins. PHYX1/PHYX2 represent the sister lineage to p-PHY. The phytochromes from glaucophytes and cyanobacteria are represented by g-PHY and c-PHY, respectively.

The origin of the canonical embryophyte phytochrome (p-PHY) can be traced to the ancestor of extant streptophyte algae37. Two phytochrome genes were identified in both the M. viride and C. atmophyticus genome, which is in accordance with a previous transcriptome study37 (Extended Data Fig. 5). Interestingly, the two genes of M. viride showed differing domain structures, one gene containing a response regulator at the C terminus regulatory module (REC), which was not identified in the previous transcriptome study37. Phylogenetic analyses indicated that a gene duplication occurred in the ancestor of streptophytes, followed by loss of REC in one of the duplicated genes, resulting in the evolution of p-PHY (Fig. 5b). Non-canonical phytochromes (PHYX1 and PHYX2) were retained in several streptophyte algal lineages.

Discussion

The successful colonization of the terrestrial landscape by plants, and their subsequent rapid evolution, is considered to be a pivotal event in the evolution of life. Here, we present the draft genomes of two early-diverging streptophyte algae that thrive in contrasting habitats: M. viride is found in the benthos of small shallow ponds, whereas C. atmophyticus is a subaerial/terrestrial alga. All previous phylogenomic analyses, including the present study, placed the two species as sister taxa in the earliest-diverging clade of streptophytes14,15,16,17. Their contrasting habitats and phylogenetic position make the genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus an exciting resource for comparative investigations into land plant evolution. Our genome analyses suggest that early-diverging streptophyte algae already took the first step on the long road to plant terrestrialization and harbour many embryophyte-type genes. Compared to Chlorophyta, the main gene family gains and expansions in early-diverging streptophyte algae were in plant hormone signal transduction, plant–pathogen interactions and TFs and regulators, most related to environmental stresses (light, temperature, salt, drought and pathogens) that are thought to have played a major role in plant terrestrialization.

Mesostigma viride and C. atmophyticus differ distinctively in their life history and cellular organization. To test whether these differences between the two species are responsible for their genome differences, we analysed the complement of flagellar genes. We detected 204 of 397 Chlamydomonas flagellar proteins in the M. viride genome. Similar numbers of conserved flagellar proteins exist in streptophyte algae that produce reproductive flagellate cells (zoospores, spermatozoids) during their life history (240 in K. nitens and 209 in C. braunii), suggesting that the ancestral number of flagellar proteins in Streptophyta was ~200–250. Second, we looked for possible differences in their life histories focusing on sexual reproduction (in C. atmophyticus sexual reproduction is unknown, in M. viride only a preliminary report exists). The core-set of meiosis-specific genes (10) were present in C. atmophyticus, whereas the M. viride genome lacked three of them. This suggested that both species reproduce sexually, although the process itself remains poorly understood.

Further insight into the differences in gene composition between M. viride and C. atmophyticus was obtained by focusing on genes involved in adaptations to the different habitats in which both species thrive. With the streptophyte algal phylogeny basically resolved, we mapped TF/TR genes on the phylogenetic tree and determined putative gains, losses, expansions and contractions of TF/TR gene family members. From this, we conclude that TFs/TRs that regulate growth and development in responses to light, salt and pathogen stresses in embryophytes originated in the common ancestor of streptophytes. Interestingly, some of the TFs/TRs thought to be involved in responses to light, salt and pathogen stresses, such as the HD-ZIPs_I–II, SRS and GRF, were absent in M. viride, perhaps lost in relation to its aquatic habitat. This hypothesis is consistent with the previous genome analysis of C. braunii (a structurally complex, streptophyte alga from an aquatic, benthic habitat) that also seems to have lost an HD-ZIP gene (HD-ZIP_IV), another HD-gene (HD_KNOX 1) and GRF7; HD-ZIP genes have also been lost in some secondarily aquatic embryophytes38.

Although elements of several biosynthetic and signalling phytohormone pathways were identified in M. viride and C. atmophyticus, they were mostly incomplete and only the CK pathway, considered to be involved in abiotic stress responses39, was fully recovered. Ethylene-related signalling homologues have previously been reported in Spirogyra pratensis and Coleochaete orbicularis40,41, and this is consistent with our findings. K. nitens also displays most of the ethylene-related genes, including the TF EIN3/EIL which is lacking in M. viride and C. atmophyticus, suggesting that this TF had its origin in the common ancestor of K. nitens and derived streptophytes6. The ABA pathway was also nearly complete but lacked the receptor PYL. A PYL orthologue was recently identified in a transcriptomic analysis of the streptophyte alga Zygnema9 (Zygnematophyceae). The absence of the F-box-mediated AUXIN, JA, GA and SL signalling pathways in the early-diverging streptophyte algae is not surprising, as previous studies have reported orthologues of most of the signalling components of these pathways in genomes of embryophytes but not of algae5,6,7,42,43. Interestingly, we identified the origin of several signalling components involved in phytohormone pathways. The PIN protein, an important auxin efflux carrier44, seems to have originated in the common ancestor of streptophytes (two PINs were detected in M. viride) or even in the common ancestor of Viridiplantae (contrary to a previous study, we detected the presence of PIN also in the Chlorellaceae45 (Chlorophyta)).

Previous studies have shown that the most important core cell wall polysaccharides of embryophytes, namely cellulose, mannan, xyloglucan, xylan and pectin, are also represented in diverse lineages of streptophyte algae12. The cellulose synthase-like gene families are among the most important players involved in the formation of plant cell walls46. Three CESA/CSLD-like homologues were identified in the C. atmophyticus genome, which showed high similarity to the respective genes in embryophytes. Our analyses also revealed the presence of putative CSL enzymes (CSLA/CSLC-like) in both genomes, but no CESA in M. viride, the latter corroborating a previous analysis using expressed sequence tags47. Our phylogenetic analysis indicated that the CESAs and CSLDs of embryophytes were derived from CESA/CSLD-like homologues present in the common ancestor of streptophytes that were lost in M. viride.

Moreover, homologues of biosynthetic genes for Rhamnogalacturonan-I and -II (RG), which are considered among the evolutionarily youngest cell wall polysaccharides of embryophytes12, such as RGXT and GALSs, were also identified in C. atmophyticus but not in M. viride. We also found cellulases in both C. atmophyticus and K. nitens but not in M. viride, indicating that M. viride lost these enzymes together with cellulose when adapting to a flagellate life history and an aquatic habitat. It is likely that mannan performs the function of cellulose in M. viride and may be restricted to a putative zygotic stage. Xyloglucan and xylan presumably evolved later (in either the common ancestor of K. nitens and other streptophytes or in the ancestor of derived streptophyte algae12,48,49). In summary, M. viride and C. atmophyticus differ considerably in their CAZymes, as expected from variation in their cellular organization, life history and habitats, but also from later-diverging streptophyte algae such as K. nitens.

Our analyses of phytochromes in the genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus corroborate previous transcriptome studies37, in that the origin of the canonical embryophyte phytochrome (p-PHY) can be traced to the common ancestor of streptophytes. We tentatively identified a gene duplication event in the common ancestor of streptophytes, followed by loss of the response regulator (REC) and the histidine phosphorylation site (H) in one of the duplicated genes. Notably, both phytochrome genes of C. atmophyticus clustered with canonical embryophyte phytochromes (p-PHY) as sisters of p-PHY of M. viride.

Conclusions

Two major conclusions can be drawn from the comparative analysis of the draft genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus: first, the common ancestor of M. viride and C. atmophyticus had already developed traits that reflect adaptations to a subaerial/terrestrial habitat, exemplified by the presence of the canonical embryophyte photoreceptor phytochrome (p-PHY), evolution of TFs implicated in responses to various abiotic and biotic stresses, near-complete pathways for several phytohormones involved in stress signalling and evolution of orthologues of cellulose synthase and cellulose synthase-like genes characteristic of embryophytes. The common ancestor of streptophytes had thus taken the first step toward plant terrestrialization, supporting a recent hypothesis that streptophyte algae lived on land before the emergence of embryophytes50.

Second, the genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus differ conspicuously in genome size, structure and gene complement, revealing the dynamic nature of their genomes perhaps in response to adaptations to their contrasting habitats. Furthermore, the phylogenetic relationship of M. viride and C. atmophyticus as sister taxa leads to the conclusion that M. viride lost several traits of a subaerial/terrestrial ancestry following transition to a benthic, freshwater habitat, a situation that finds a parallel in the secondarily aquatic C. braunii7. Although adaptations to terrestrial life progressed stepwise in streptophyte algae, this did not follow a linear path with deviations into aquatic habitats apparently occurring repeatedly, requiring careful comparative genomic and phylogenomic analyses of a larger taxon set of streptophyte algae in future studies.

Methods

Culture, nucleic acid extraction and light microscopy

Axenic cultures of M. viride (CCAC 1140) and C. atmophyticus (CCAC 0220) were obtained from the Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Cologne, and grown in Waris-H culture medium51 (http://www.ccac.uni-koeln.de/). During all steps of culture scale-up until nucleic acid extraction, axenicity was monitored by both sterility tests and light microscopy. Total RNA was extracted from M. viride using the Tri Reagent Method, and from C. atmophyticus using the CTAB-PVP method as described in ref. 52. Total DNA was extracted using a modified CTAB protocol53 (details below). Light microscopy was performed with a Leica DMLB light microscope using a PL-APO ×100/1.40 numerical aperture (NA) objective, an immersed condenser (NA, 1.4) and a Metz Mecablitz 32 Ct3 flash system.

Genome sequencing, data preparation and genome assembly

Paired-end libraries with insert sizes of 170 bp, 200 bp, 500 bp, 800 bp, 2 kb, 5 kb, 10 kb and 20 kb were constructed following standard Illumina protocols. The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000/4000 and BGI-seq 500 platform. A total of 245 Gb (about 746.86X) and 66.46 Gb (about 775.68X) paired-end data were generated for M. viride (CCAC 1140) and C. atmophyticus (CCAC 0220), respectively. To reduce the effect of sequencing error on assembly, we performed a rigorous quality control of raw data. We used CLC Assembly Cell (v.5.0.1)54 to trim the adaptors, remove duplicates and trim low-quality bases. We then used Pairfq (v.0.16.0) (https://github.com/sestaton/Pairfq) to pair the reads. Finally, SOAPfilter (v.2.2) was used to filter the reads again. After filtering off duplicated and low-quality reads and those with adaptor sequences, 74.63 and 14.51 Gb high-quality clean reads remained for M. viride (CCAC1140) and C. atmophyticus (CCAC 0220), respectively, which were then subjected to a pipeline for genome assembly.

k-mer analysis was performed to survey genome size, heterozygosity and repeat content before genome assembly. The peak of k-mer frequency (F) is determined by the total reads number (N), genome size (G), read length (L) and the length of k-mer (K), following the formula: F = N × (L – K + 1)/G. Total k-mer number (M) is determined by the formula M = N × (L – K + 1). As a result, genome size can be calculated by G = M/F. This formula enables accurate estimation of G, and hence an estimation of genome size for homozygous diploid or haploid genomes. All the above analyses indicated homozygosity of the genome and gave similar estimations of genome size. The final genome size estimate (329 Mb for M. viride and 85.68 Mb for C. atmophyticus) was obtained through 17-mer analysis.

We carried out the SPAdes (v.3.10.1)55 genome assembly algorithm to assemble the contigs of M. viride. The contigs were formed without gaps. Subsequently platanus (v.1.2.4) was conducted to construct the scaffolds, from short insert-sized paired-end reads to long insert-sized paired-end reads. To extend the assembly and close gaps, the scaffolder SSPACE (v.3.0)56 was applied to extend the scaffolds while GapCloser (v.1.12) was used to close gaps and extend the scaffolds again. For C. atmophyticus, the assembly was generated by SOAPdenovo-127-mer (v.2.04)57 with a k-mer of 85. To close the gaps within the constructed scaffolds, we used paired-end reads mapped to the scaffolds using GapCloser (v.1.12). Variant detection was done using Pilon (v.2.11) to improve draft assembly quality.

The quality of the assembly was evaluated in four ways. First, we used BUSCO (v.3)58 to determine the proportion of a core-set of 303 highly conserved eukaryotic genes present in the genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus. Second, Soap (v.2.21) was used to map the reads to the draft assemblies to evaluate the DNA reads mapping rate in both species. Meanwhile, sequence depth and genetic copy content distribution were calculated. Third, we used BLAT (v.36)59 to compare the draft assemblies to a transcript assembled by Bridger. Finally, we mapped the RNA reads to the draft assemblies to evaluate the RNA reads mapping rate using Tophat2 (ref. 60).

Transcriptome sequencing and analysis

For Illumina sequencing, we considered two ways of library construction. The ribosomal RNA-depleted RNA library was constructed using the ribo-zero rRNA removal kit (plant) (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s protocol, while the poly(A)-selected RNA library was constructed using the ScriptSeq Library Prep kit (Plant leaf) (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s protocol. These libraries were sequenced on the Illumina sequencing system. All of the sequenced data were then assembled into transcripts following the Bridger pipeline. This set of transcript sequences was used for assessing the accuracy of the genome assembly and for gene annotation.

Gene expression was measured as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads.

Detection and classification of repetitive elements

Three types of repeat (DNA transposon elements, retrotransposon elements and tandem repeats) were identified in the genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus. DNA transposons and retrotransposon elements were identified using MITE-hunter61 and LTRharvest62, respectively. RepeatModeler (v.1.0.8) was used to search for other repeats using a de novo approach. Alternatively, RepeatMasker63 was applied to using a custom library comprising a combination of Repbase and a de novo-predicted repetitive element library.

Gene prediction

We used a combination of de novo gene prediction methods, homology-based search methods and RNA sequencing-aided annotation methods. For de novo gene prediction, PASApipeline v.2.1.0 was applied to predict gene structure using transcripts assembled by Bridger, after which the inferred gene structures were used in AUGUSTUS (v.3.2.3)64 to train gene models based on transcript evidence. In addition, GeneMark (v.1.0)65 was used to build a hidden Markov model based on genome sequence. For homology-based annotation, we selected gene sets from certain model green algae. In regard to RNA sequencing-aided methods, we took the transcripts assembled by Bridger as evidence. The final consensus gene sets were generated by combining all the evidence using MAKER (v.2.31.8)66. The result of the first round was used for SNAP to train another hidden Markov model based on transcriptome. Subsequently, the hidden Markov model was added to MAKER.

The final gene set was evaluated with two approaches. The BUSCO core eukaryotic gene-mapping approach was used to determine gene set completeness; RNA read mapping was another means of evaluation. We mapped the RNA reads to the gene set with Tophat2, while coverage depth was calculated by Samtools (v.0.1.19).

Gene function annotation was performed by BLASTP (1 × 10–5) against several known databases, including SwissProt, TrEMBL, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), COG and NR. InterProScan (using data from Pfam, PRINTS, SMART, ProDom and PROSITE) was used to identify protein motifs and protein domains of the predicted gene set. Gene Ontology information was obtained through Blast2go (v.2.5.0).

Comparative genome analyses and phylogenetics

The genomes of M. viride and C. atmophyticus were compared to those of nine other algae, namely Cyanophora paradoxa, Chondrus crispus, C. merolae, M. commoda, Ostreococcus tauri, Chlorella variabilis, Volvox carteri and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, with the Streptophyta C. braunii, K. nitens, Physcomitrella patens, Selaginella moellendorffii, Oryza sativa subsp. Japonica and Arabidopsis thaliana. The same species were used to define orthogroups (using OrthoFinder, v.1.1.8). Single-copy gene families (that is, gene families with only one gene member per species) were used to construct phylogenetic trees based on maximum likelihood. We first performed multiple sequence alignment by MAFFT (v.7.310) for each single-copy gene orthogroup, followed by gap position removal (only positions where 50% or more of the sequences have a gap are treated as a gap position). A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed for each single-copy orthogroup. Next, we used ASTRAL to combine all single-copy gene trees to a species tree with the multi-species coalescent model. The online tool iTOL was performed to edit and display the final phylogenetic tree.

Gene identification

We used various search methods to identify different genes.

For TFs and TR we used the HMMER search method. We downloaded the HMMER model of the domain structure of each TF from the Pfam website (https://pfam.xfam.org/), referring to the TAPscan (v.2) TF database (https://plantcode.online.uni-marburg.de/tapscan/). Preliminary candidates were collected by searching the HMM profile for each species (<1 × 10–10). Then, we filtered genes that did not match the SwissProt functional annotation (<1 × 10–5). Finally, we filtered genes containing an incorrect domain according to the domain rules of the TAPscan (v.2) TF database. Most TFs/TRs were confirmed by phylogenetic analysis.

The HMMER search method was also used for phytohormone signalling pathways. We collected ~10–20 query genes from representative model organisms (for example, A. thaliana and C. reinhardtii). A custom profile HMM was built (hmmer-3.1b2) based on the query genes for each phytohormone. All signalling pathway genes must pass the following two restrictions: (1) genes should pass the HMM profile built by ~10–20 known genes (<1 × 10–10), and (2) genes should match the SwissProt functional annotation (<1 × 10–5). The custom profile HMM is available in the Supplementary Information (HMM profiles).

The genes involved in other pathways, such as biosynthetic phytohormone pathways and cell wall-related genes, were selected based on two criteria : (1) BLAST by known query genes (<1 × 10–5), and (2) matching based on SwissProt functional annotation (<1 × 10–5).

For CAZyme annotation we used the dbCAN2 metaserver (http://bcb.unl.edu/dbCAN2/index.php). This server integrates three tools/databases for automated CAZyme annotation: (1) HMMER for annotation of the CAZyme domain against the dbCAN CAZyme domain HMM database; (2) DIAMOND for fast BLAST hits in the CAZy database; and (3) Hotpep for short conserved motifs in the PPR library.

We also constructed phylogenetic trees to classify certain highly similar genes, including ARF, CSL, HD-ZIP, YUCCA, PIF, TGA and others (see Supplementary Figs. 6–13). For phylogenetic analysis of individual genes, we first performed multiple sequence alignment by MAFFT (v.7.310) for each single-copy gene orthogroup, followed by removal of gap position (only positions where 50% or more of the sequences have a gap are treated as gap positions). Then, a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed by RAxML (amino acid substitution model: CAT + GTR, with 500 bootstrap replicates).

Analysis of significantly increased/decreased gene numbers of gene families

We used a median gene number to estimate the changes in gene family size6, shown in Fig. 1d. These showed the gene families whose numbers of genes were significantly increased in embryophytes compared to algae, by calculating the median of the embryophyte gene number/median of the algal gene number ≥10. Taking Rhodophyta and Streptophyta as an example, we selected five representative species for each lineage. Gene numbers of these lineages in the gene family were sorted from largest to smallest. If the median of the Streptophyta gene number/median of the Rhodophyta gene number was >5, this gene family was considered a significantly increased gene family in Streptophyta. The same method is used to define the embryophytes and algal genes in Fig. 1e. If the median gene number of both embryophytes and algae was >0, we defined the genes in this family as those commonly shared between embryophytes and algae. If the median embryophyte gene number was >0 and the median algae gene number was 0, we defined the genes in this family as embryophyte genes. In special cases, if both the median embryophyte and median algae gene number was 0, we removed those low-frequency gene families.

Conserved motif identification

The local multiple Em (expectation maximization) for motif elicitation (MEME, http://meme-suite.org/) tool was used to identify conserved motifs. All genes in this study were analysed using the classical model. According to e values, the number of motifs that MEME should find was set to 20.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The whole-genome assemblies and transcriptome for M. viride and C. atmophyticus in this study are deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession nos. RHPH00000000 and RHPI00000000. Those data are also available in the CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (accession no. CNP0000228).

References

Kenrick, P. & Crane, P. The origin and early evolution of plants on land. Nature 389, 33–39 (1997).

Becker, B. & Marin, B. Streptophyte algae and the origin of embryophytes. Ann. Bot. 103, 999–1004 (2009).

Delwiche, C. F. & Cooper, E. D. The evolutionary origin of a terrestrial flora. Curr. Biol. 25, R899–R910 (2015).

Delaux, P.-M. et al. Algal ancestor of land plants was preadapted for symbiosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 13390–13395 (2015).

Bowman, J. L. et al. Insights into land plant evolution garnered from the Marchantia polymorpha genome. Cell 171, 287–304 (2017).

Hori, K. et al. Klebsormidium flaccidum genome reveals primary factors for plant terrestrial adaptation. Nat. Commun. 5, 3978 (2014).

Nishiyama, T. et al. The Chara genome: secondary complexity and implications for plant terrestrialization. Cell 174, 448–464 (2018).

Bowman, J. L., Briginshaw, L. N., Fisher, T. J. & Flores-Sandoval, E. Something ancient and something neofunctionalized—evolution of land plant hormone signaling pathways. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 47, 64–72 (2019).

de Vries, J., Curtis, B. A., Gould, S. B. & Archibald, J. M. Embryophyte stress signaling evolved in the algal progenitors of land plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E3471–E3480 (2018).

de Vries, J., Stanton, A., Archibald, J. M. & Gould, S. B. Streptophyte terrestrialization in light of plastid evolution. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 467–476 (2016).

Zhao, C. et al. Evolution of chloroplast retrograde signaling facilitates green plant adaptation to land. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 5015–5020 (2019).

Mikkelsen, M. D. et al. Evidence for land plant cell wall biosynthetic mechanisms in charophyte green algae. Ann. Bot. 114, 1217–1236 (2014).

Wilhelmsson, P. K. I., Mühlich, C., Ullrich, K. K. & Rensing, S. A. Comprehensive genome-wide classification reveals that many plant-specific transcription factors evolved in streptophyte algae. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 3384–3397 (2017).

Lemieux, C., Otis, C. & Turmel, M. A clade uniting the green algae Mesostigma viride and Chlorokybus atmophyticus represents the deepest branch of the streptophyta in chloroplast genome-based phylogenies. BMC Biol. 5, 2 (2007).

Timme, R. E., Bachvaroff, T. R. & Delwiche, C. F. Broad phylogenomic sampling and the sister lineage of land plants. PLoS ONE 7, e29696 (2012).

Wickett, N. J. et al. Phylotranscriptomic analysis of the origin and early diversification of land plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E4859–E4868 (2014).

Wodniok, S. et al. Origin of land plants: do conjugating green algae hold the key? BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 104 (2011).

Cook, M. E. & Graham, L. E. in Handbook of the Protists (eds Archibald, J. M. et al.) 1–20 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Ariel, F. D., Manavella, P. A., Dezar, C. A. & Chan, R. L. The true story of the HD-Zip family. Trends Plant Sci. 12, 419–426 (2007).

Bouzroud, S. et al. Auxin response factors (ARFs) are potential mediators of auxin action in tomato response to biotic and abiotic stress (Solanum lycopersicum). PLoS ONE 13, e0193517 (2018).

Guan, H. et al. Genome-wide identification, phylogeny analysis, expression profiling, and determination of protein–protein interactions of the LEUNIG gene family members in tomato. Gene 679, 1–10 (2018).

Kaplan-Levy, R. N., Brewer, P. B., Quon, T. & Smyth, D. R. The trihelix family of transcription factors – light, stress and development. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 163–171 (2012).

Mukherjee, K., Brocchieri, L. & Bürglin, T. R. A comprehensive classification and evolutionary analysis of plant homeobox genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 2775–2794 (2009).

Omidbakhshfard, M. A., Proost, S., Fujikura, U. & Mueller-Roeber, B. Growth-regulating factors (GRFs): a small transcription factor family with important functions in plant biology. Mol. Plant 8, 998–1010 (2015).

Paul, A. et al. RNA-seq-mediated transcriptome analysis of actively growing and winter dormant shoots identifies non-deciduous habit of evergreen tree tea during winters. Sci. Rep. 4, 5932 (2014).

Yoshida, T., Mogami, J. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. ABA-dependent and ABA-independent signaling in response to osmotic stress in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 21, 133–139 (2014).

Brenner, W. G., Romanov, G. A., Köllmer, I., Bürkle, L. & Schmülling, T. Immediate-early and delayed cytokinin response genes of Arabidopsis thaliana identified by genome-wide expression profiling reveal novel cytokinin-sensitive processes and suggest cytokinin action through transcriptional cascades. Plant J. 44, 314–333 (2005).

Ulvskov, P., Paiva, D. S., Domozych, D. & Harholt, J. Classification, naming and evolutionary history of glycosyltransferases from sequenced green and red algal genomes. PLoS ONE 8, e76511 (2013).

Petersen, B. L., Faber, K. & Ulvskov, P. Glycosyltransferases of the GT77 family. Ann. Plant Rev. 41, 305–320 (2010).

Cheng, L. et al. Expressional characterization of galacturonosyltransferase-like gene family in Eucalyptus grandis implies a role in abiotic stress responses. Tree Genet. Genomes 14, 81 (2018).

Brawley, S. H. et al. Insights into the red algae and eukaryotic evolution from the genome of Porphyra umbilicalis (Bangiophyceae, Rhodophyta). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E6361–E6370 (2017).

Minic, Z. & Jouanin, L. Plant glycoside hydrolases involved in cell wall polysaccharide degradation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 44, 435–449 (2006).

Tekle, Y. I., Wood, F. C., Katz, L. A., Cerón-Romero, M. A. & Gorfu, L. A. Amoebozoans are secretly but ancestrally sexual: evidence for sex genes and potential novel crossover pathways in diverse groups of amoebae. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 375–387 (2017).

Nevers, Y. et al. Insights into ciliary genes and evolution from multi-level phylogenetic profiling. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 2016–2034 (2017).

Keeling, P. J. & Inagaki, Y. A class of eukaryotic GTPase with a punctate distribution suggesting multiple functional replacements of translation elongation factor 1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15380–15385 (2004).

Cocquyt, E. et al. Gain and loss of elongation factor genes in green algae. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 39 (2009).

Li, F. W. et al. Phytochrome diversity in green plants and the origin of canonical plant phytochromes. Nat. Commun. 6, 7852 (2015).

Romani, F., Reinheimer, R., Florent, S. N., Bowman, J. L. & Moreno, J. E. Evolutionary history of HOMEODOMAIN LEUCINE ZIPPER transcription factors during plant transition to land. New Phytol. 219, 408–421 (2018).

Bari, R. & Jones, J. D. G. Role of plant hormones in plant defence responses. Plant Mol. Biol. 69, 473–488 (2009).

Ju, C. et al. Conservation of ethylene as a plant hormone over 450 million years of evolution. Nat. Plants 1, 14004 (2015).

Van de Poel, B., Cooper, E. D., Van Der Straeten, D., Chang, C. & Delwiche, C. F. Transcriptome profiling of the green alga Spirogyra pratensis (Charophyta) suggests an ancestral role for ethylene in cell wall metabolism, photosynthesis, and abiotic stress responses. Plant Physiol. 172, 533–545 (2016).

Han, G. Z. Evolution of jasmonate biosynthesis and signalling mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 1323–1331 (2017).

Ohtaka, K., Hori, K., Kanno, Y., Seo, M. & Ohta, H. Primitive auxin response without TIR1 and Aux/IAA in the charophyte alga Klebsormidium nitens. Plant Physiol. 174, 1621–1632 (2017).

Křeček, P. et al. The PIN-FORMED (PIN) protein family of auxin transporters. Genome Biol. 10, 249 (2009).

Viaene, T., Delwiche, C. F., Rensing, S. A. & Friml, J. Origin and evolution of PIN auxin transporters in the green lineage. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 5–10 (2013).

Yin, Y., Huang, J. & Xu, Y. The cellulose synthase superfamily in fully sequenced plants and algae. BMC Plant Biol. 9, 99 (2009).

Simon, A., Glöckner, G., Felder, M., Melkonian, M. & Becker, B. EST analysis of the scaly green flagellate Mesostigma viride (Streptophyta): implications for the evolution of green plants (Viridiplantae). BMC Plant Biol. 6, 1–13 (2006).

Del-Bem, L. E. Xyloglucan evolution and the terrestrialization of green plants. New Phytol. 219, 1150–1153 (2018).

Jensen, J. K. et al. Identification of an algal xylan synthase indicates that there is functional orthology between algal and plant cell wall biosynthesis. New Phytol. 218, 1049–1060 (2018).

Harholt, J., Moestrup, Ø. & Ulvskov, P. Why plants were terrestrial from the beginning. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 96–101 (2016).

McFadden, G. I. & Melkonian, M. Use of Hepes buffer for microalgal culture media and fixation for electron microscopy. Phycologia 25, 551–557 (1986).

Johnson, M. T. J. et al. Evaluating methods for isolating total RNA and predicting the success of sequencing phylogenetically diverse plant transcriptomes. PLoS ONE 7, e50226 (2012).

Rogers, S. O. & Bendich, A. J. Extraction of DNA from milligram amounts of fresh, herbarium and mummified plant tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 5, 69–76 (1985).

White Paper on De Novo Assembly in CLC Assembly Cell 4.0 (CLC bio A/S, 2012).

Bankevich, A. et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477 (2012).

Boetzer, M., Henkel, C. V., Jansen, H. J., Butler, D. & Pirovano, W. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 27, 578–579 (2010).

Luo, R. et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience 1, 18 (2012).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Kent, W. J. BLAT—the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12, 656–664 (2002).

Kim, D. et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36 (2013).

Han, Y. & Wessler, S. R. MITE-Hunter: a program for discovering miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements from genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e199–e199 (2010).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 18 (2008).

Chen, N. Using repeatmasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 5, 4–10 (2004).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–W439 (2006).

Besemer, J. & Borodovsky, M. GeneMark: web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W451–W454 (2005).

Campbell, M. S. et al. MAKER-P: a tool kit for the rapid creation, management, and quality control of plant genome annotations. Plant Physiol. 164, 513–524 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Günther (http://www.mikroskopia.de/index.html), who took microscopic images of M. viride and C. atmophyticus. Financial support was provided by the Shenzhen Municipal Government of China (grant nos. JCYJ20151015162041454 and JCYJ20160531194327655) and the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Genome Read and Write (grant no. 2017B030301011). This work is part of the 10KP project led by BGI-Shenzhen and China National GeneBank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L., M.M. and H. Liu conceived, designed and supervised the project. X.L., M.M., B.M., H. Liu., X.X., J.W., H.Y., Y.V.P. and G.K.-S.W. provided resources and materials. Z.C. and S.K.S. developed the protocol for DNA extraction. S. Wittek and T.R. grew the organisms to quantity and extracted DNA. Samples were sequenced by BGI. S.Wang. and L.L. generated the draft genome and performed the annotation. S.Wang., L.L., H. Li., S.K.S., H.W., Y.X., W.X., B.S., H. Liang, S.C., Y.C., Y.S. and M.P. analysed data. S. Wang., L.L., S.K.S. and M.M. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Plants thanks John Bowman, Stefan Rensing, Charles Wellman and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 The KEGG distribution of unique proteins in M. viride (blue) and C. atmophyticus (pink).

The x-axis indicates the number of genes in a specific category in the respective species. The metabolism pathway is shown on the y-axis.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Sequence conservation of various phytohormone receptor genes in representative species.

Each cell shows a pairwise sequence alignment between a known Arabidopsis protein receptor (top) and the best BLAST hit (E-value <1e−10) in the translated genome of the indicated species. Black and grey represent similar amino acids (the darker the bars, the higher is the similarity).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Analysis of the conserved flagellar proteome in flagellate and non-flagellate organisms and the distribution of key flagellar proteins.

Key structure-related flagellar proteins in flagellate and non-flagellate algal species in different lineages. The phylogenetic tree on the left panel was constructed using maximum-likelihood method based on the concatenated sequences of single-copy genes from these genomes, after excluding the species-specific gene duplications. The presence (filled circle) or absence (empty circle) of putative orthologs to conserved flagellar proteins is shown on right panel [Based on Reciprocal Blast Hit (RBH) method with Cut-off value of e-5]. The histogram on the lower panel shows the differential expression level of these important structure-related flagellar proteins.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Distribution of EF-1α and EF-like motifs.

Maximum Likelihood was used to infer the phylogenetic tree of the EF-1α and EF-like homologs to understand their phylogenetic distribution. The right panel displays the representative EF-1α and EF-like motifs from red algae to embryophytes. The tree derived from a MAFFT alignment and constructed using IQ-TREE (see Methods). Bootstrap values (500 replicates) ≥50% are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Phylogenetic tree of phytochrome.

Maximum Likelihood was used to infer the phylogenetic tree of the phytochrome. The tree derived from a MAFFT alignment and constructed using RAxML (see Methods). Bootstrap values (500 replicates) ≥50% are shown.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–15.

Supplementary Table 1.

Supplementary ST 1–37.

Supplementary Data 1

The HMMER profile of phytohormone genes.

Supplementary Data 2

The HMMER profile of transcription factors and transcription regulators.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Li, L., Li, H. et al. Genomes of early-diverging streptophyte algae shed light on plant terrestrialization. Nat. Plants 6, 95–106 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0560-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0560-3

This article is cited by

-

Uncovering the photosystem I assembly pathway in land plants

Nature Plants (2024)

-

A mysterious cloak: the peptidoglycan layer of algal and plant plastids

Protoplasma (2024)

-

Environmental gradients reveal stress hubs pre-dating plant terrestrialization

Nature Plants (2023)

-

MarFERReT, an open-source, version-controlled reference library of marine microbial eukaryote functional genes

Scientific Data (2023)

-

Genome-wide identification of wheat ABC gene family and expression in response to fungal stress treatment

Plant Biotechnology Reports (2023)