Abstract

Bound states in the continuum (BICs) have received significant attention for their ability to enhance light-matter interactions across a wide range of systems, including lasers, sensors, and frequency mixers. However, many applications require degenerate or nearly degenerate high-quality factor (Q) modes, such as spontaneous parametric down conversion, non-linear four-wave mixing, and intra-cavity difference frequency mixing for terahertz generation. Previously, degenerate pairs of bound states in the continuum (BICs) have been created by fine-tuning the structure to engineer the degeneracy, yielding BICs that respond unpredictably to structure imperfections and material variations. Instead, using a group theoretic approach, we present a design paradigm based on six-fold rotational symmetry (C6) for creating degenerate pairs of symmetry-protected BICs, whose frequency splitting and Q-factors can be independently and predictably controlled, yielding a complete design phase space. Using a combination of resonator and lattice deformations in silicon metasurfaces, we experimentally demonstrate the ability to tune mode spacing from 2 nm to 110 nm while simultaneously controlling Q-factor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last decade, all-dielectric metasurfaces have emerged as a powerful platform for enhancing light-matter interactions. Unlike their metallic counterparts, all-dielectric metasurfaces can exhibit high-quality factor (Q) states that can be used to increase the performance of a variety of nonlinear phenomena, such as frequency conversion1, actively tunable optics2,3,4, and single-mode lasing5,6. Recently, bound states in the continuum (BICs) have emerged as the starting point for design principles to create states with arbitrarily large Q-factors across many photonic platforms. BICs are states that possess infinite lifetimes (i.e., infinite Q-factors) despite having frequencies that are degenerate with the surrounding continuum of radiative/scattering channels. Since no light can enter or leave a BIC, designing a system to operate at a BIC is generally undesirable for most applications. However, the existence of a BIC in a system’s parameter space guarantees a neighborhood in design space (around the BIC) where a quasi-BIC is formed and the state’s Q-factor can be made arbitrarily large. While there are a few different methods for creating BICs in metasurfaces7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, protecting a state from radiating due to its incompatible symmetry with the radiative channels in free space has proven to be a robust experimental pathway for generating BICs. This method is easily predictable and provides a simple route to tunable Q-factors via judicious symmetry breaking. As such, symmetry-protected BICs have been used to realize lasers15,16,17,18,19,20, narrowband optical filters21,22,23,24, wavefront shapers25,26,27, optical sensors28,29,30,31, frequency combs32, and metasurfaces for harmonic generation33,34.

Nevertheless, despite the dramatic successes of using symmetry-protected BICs to enhance nonlinear optical phenomena, the majority of these previous realizations have relied on spectrally isolated BICs, where a single high-Q state is used to enhance light-matter interactions. This fundamentally limits the classes of nonlinear phenomena that can be easily realized experimentally using these systems, precluding these structural designs from being used for applications which require two modes with similar frequencies (i.e., nearly degenerate) that both possess large Q-factors, such as spontaneous parametric down conversion35,36,37, nonlinear four-wave mixing38,39, four-wave mixing optical bistability40,41,42, and intracavity difference frequency mixingfor terahertz generation43,44,45. Although some recent studies have attempted to overcome this shortcoming through fine-tuning an accidental degeneracy between two otherwise spectrally isolated BICs36,46,47,48,49,50, yielding nearly degenerate states where the frequency splitting, center frequency, and relative polarization states in such systems are extremely sensitive to material variations and fabrication imperfections, both of which yield unpredictable changes to the properties of the two states51,52,53.

Here, we theoretically and experimentally demonstrate a metasurface design paradigm that enables predictable and robust control over the frequency splitting and, independently, the Q-factors of two otherwise degenerate metasurface states. Our design methodology is based on a triangular lattice with six-fold rotational symmetry (C6), which, as we show, is the only possible rotational symmetry that allows for a metasurface to possess symmetry-guaranteed degenerate pairs of symmetry-protected BICs (when combined with reflection or time-reversal symmetry). We prove that the two independent subgroups of C6 each yield a distinct method for controlling the behavior of these pairs of metasurface states: two-fold rotational symmetry (C2) controls the Q-factors of these pairs of states, while three-fold rotational symmetry (C3) controls the frequency splitting between the two states in each pair. (In this work we adopt the notation of Cn referring to an element in the cyclic group, and Cn referring to the group itself54). Thus, by judiciously breaking either or both of these symmetries, our design paradigm facilitates independent control over the Q-factors and frequency splitting of these pairs of states. Experimentally, we realize our system in all-dielectric metasurfaces composed of silicon resonators on fused silica substrates, and measure the frequencies and Q-factors of the resonances using reflectance measurements. To demonstrate the versatility of our design paradigm, we fabricate reflection-symmetric metasurfaces with many strengths of symmetry breaking to destroy the system’s C2 or C3 symmetries by using a combination of resonator and lattice deformations. This tuning process is conceptually illustrated in Fig. 1a. Moreover, as our methodology is based solely on symmetry and does not rely upon fine-tuning the states of a structure, it is robust against material variations and fabrication imperfections that preserve symmetry; any changes in the filling fraction, thickness, or isotropic dielectric constant of the metasurface affect the two states equally, and do not result in uncontrolled changes to the states Q-factors or frequency splitting. In comparison, when designing accidental degeneracies through fine-tuning, the degeneracy will generally be lifted by both symmetry-preserving and symmetry-breaking imperfections. Our design paradigm not only enables robust mode engineering in photonic systems, but also provides a pathway for improving the design of a broad range of devices across a wide range of fields, including quantum light sources, RF antennas, and phonon traps in mechanical systems.

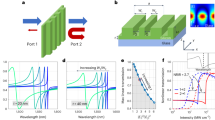

a Conceptual diagram of symmetry-protected degenerate bound states in the continuum. The Q-factor and mode splitting can be independently controlled by breaking C2 and C3 symmetries, respectively. b Band structure of two-dimensional triangular lattice of dielectric circles (n = 3.5). Degenerate, symmetry-protected BICs appear at the Γ-point at 150, 195, and 270 THz denoted with triangle markers. The modes can be categorized as E2 TM Γ(1), E2 TE Γ(1), and E2 TE Γ(3), respectively. Here, the degenerate symmetry-protected BICs at Γ are labeled using the notation E2 P L(α). Here, P denotes whether the mode is TE or TM, L denotes the high-symmetry point in Brillouin zone, and α is the order of the extended Brillouin zone. Symmetry can be broken by having a non-zero in-plane wavevector, resulting in the degeneracies being lifted. c Eigenfrequencies for the degenerate, symmetry-protected BICs denoted in b when the triangular lattice of dielectric circles is transformed into a triangular lattice of dielectric squares. This transformation breaks C3 lifting the degeneracy, but leaves C2 intact requiring the modes to remain symmetry-protected BICs. Insets show the electric and magnetic field profiles for transverse magnetic and transverse electric modes, respectively.

Results

Group theory design principles

There are two essential ingredients that are necessary to realize the symmetry-guaranteed pairs of BICs that our metasurface design paradigm is predicated upon. First, for some in-plane wavevector, k∥, the in-plane symmetry of the crystalline metasurface must be sufficiently high so as to support pairs of states that are guaranteed to be degenerate54,55,56. This requires that the metasurface’s dielectric structure possess three-fold (C3), four-fold (C4), or six-fold (C6) rotational symmetry in addition to either reflection or time-reversal symmetry. (A crystalline metasurface that only possesses the rotational symmetries of a Cn cyclic group is not guaranteed to exhibit any degeneracies. However, if a C3-, C4-, or C6-symmetric metasurface’s design is also reflection symmetric, or it is comprised of materials that preserve time-reversal symmetry, then the metasurface is guaranteed to exhibit pairs of degenerate states. When reflection symmetries are added, these degeneracies can arise from (d ≥ 2)-dimensional irreducible representations of Cnv. When the metasurface possesses rotation and time-reversal symmetries, the Wigner criterion (Herring test) guarantees degeneracies between time-reversal conjugate representations that are otherwise one-dimensional representations.) Second, for these symmetry-guaranteed pairs of states to be BICs, they must be unable to couple to the radiative channels in the surrounding medium at the same frequency, ω, and k∥. Although in principle there are a variety of mechanisms that can be used to prohibit a state from radiating10, the only method that is applicable to a pair of states without fine-tuning the structure is to create a symmetry mismatch between the metasurface’s states and the radiative channels in the surrounding environment. To avoid confusion between the two separate roles that symmetry is performing in our design methodology, we describe the symmetry-induced degeneracy between two metasurface states as “symmetry-guaranteed,” and reserve “symmetry-protected” for the specific method of creating a BIC by prohibiting a state from coupling to the environment’s radiative continuum due to its mismatched symmetry.

For a metasurface state to be a symmetry-protected BIC (regardless of whether the state is degenerate), the state must be at the center of the Brillouin zone, k∥ = Γ, and be even with respect to 180° rotation about the out-of-plane axis (C2) or be at a momentum-space polarization singularity57,58. The first requirement can be proven as a consequence of the Bragg-diffraction limit and the degeneracy between s- and p-polarized waves in free space59, while the latter requirement stems from the fact that the radiative channels at Γ in free space (or any homogeneous and isotropic environment) are always odd with respect to C2. In particular, this latter requirement is especially restrictive for symmetry-guaranteed degenerate states, as even though there are a few different possibilities of the metasurface’s in-plane rotational symmetry that allow for symmetry-guaranteed degeneracies, only the presence of six-fold rotational symmetry (C6) allows for degenerate pairs that are simultaneously even with respect to C2 (these states form the E2 irreducible representation regardless of whether reflection or time-reversal symmetry has been added to the system). Thus, only C6-symmetric metasurfaces that are either reflection or time-reversal symmetric can support symmetry-guaranteed degenerate pairs of symmetry-protected BICs.

Among the possible rotational symmetry point groups of two-dimensional crystalline structures, C6 is unique in possessing two independent, non-trivial subgroups, C2 and C3. As such, it is possible to start with a C6-symmetric structure and judiciously break either its C2 or C3 symmetry while preserving the other (and preserving reflection and/or time-reversal symmetry). Crucially, these two possibilities for reducing the symmetry of a metasurface with C6 symmetry and either reflection or time-reversal symmetry, yield independent effects on its states. For example, it is well known that breaking a metasurface’s C2 symmetry can be used to control the Q-factors of its BICs. However, breaking C2 symmetry of an originally C6-symmetric metasurface (that is also reflection or time-reversal symmetric) need not split the degeneracy between any of the metasurface’s symmetry-guaranteed degenerate states, as the resulting C3-symmetric systems still possess symmetry-guaranteed degeneracies (both the E1 and E2 irreducible representations of the original metasurface correspond to the E irreducible representation of the C3-symmetric metasurface). Similarly, breaking C3 symmetry of a C6-symmetric metasurface does not change any of the states behavior under C2; those states which were originally even about this rotational operation (and thus were BICs) are still even in the metasurface with reduced symmetry. Thus, the symmetry-guaranteed degenerate pairs of symmetry-protected BICs in C6-symmetric metasurfaces can be controlled along two independent axes, with C2 symmetry controlling the states’ Q-factors and C3 symmetry controlling the frequency splitting between these pairs of states.

Altogether, these two independent controls over the behavior of a metasurface with C6 symmetry and either reflection or time-reversal symmetry are shown in Fig. 1a, which schematically shows the behavior of the Q-factors and frequencies of the modes as first C2 symmetry is broken, and then C3. A specific example in a C6-symmetric metasurface with reflection symmetry (C6v) is shown in Fig. 1b and c. Away from Γ, the degeneracy between the pairs of states is broken by the non-zero wavevector (Fig. 1b). However, the degeneracy between these pairs of states can also be lifted at Γ by reducing the symmetry of the metasurface to C2v through geometric deformations, Fig. 1c. Here, we define a function of a single symmetry-breaking parameter, S, to deform the resonator cross sections from circles (S = 0) into squares (S = 1) that preserves the filling fraction of the unit cell (geometric definition in Methods). Throughout this deformation process, these modes are still BICs, as they remain even with respect to C2.

Independent control of splitting and Q-factor

To demonstrate full control of Q-factor and splitting, we designed and fabricated a series of silicon metasurfaces on fused silica substrates where two classes of deformations were applied to break the C2 and C3 symmetries of a lattice that would otherwise possess C6v symmetry. The silicon metasurfaces had a period—1000 nm, thickness—200 nm, resonator diameter—800 nm, and bar width—100 nm. While there are many combinations of resonator and lattice deformations capable of breaking C2 and C3 symmetries, a resonator and lattice deformation were chosen to break C2 and C3, respectively, since the combination is more compatible with the capabilities of electron-beam lithography. An extended discussion on design considerations and an experimental demonstration using only resonator deformations to break C2 and C3 symmetries are presented in the supplementary information.

To break C2 symmetry, the circular resonators were smoothly deformed into triangular resonators (geometric definition in Methods) as depicted in Fig. 2a (this operation preserves C3 and reflection symmetries, as well as the filling fraction of the unit cell). In contrast, the lattice was contracted along one axis to break C3 symmetry (an operation that preserves C2 and reflection symmetries). From these deformations, we define the C2 and C3 symmetry-breaking parameters as S and δ, respectively. A false-color scanning electron micrograph of a representative metasurface is presented in Fig. 2b.

a By deforming the circular resonators into triangles, C2 symmetry can be broken (an operation that preserves C3). Correspondingly, C3 symmetry can be broken by contracting the lattice along one axis (an operation that preserves C2). From these two deformations, we define symmetry-breaking parameters S and δ to denote the strength of C2 and C3 symmetry breaking, respectively. b False-color scanning electron micrograph of a fabricated silicon metasurface on a fused silica substrate.

Together, these symmetry-breaking parameters enable navigation through four symmetry phases and therefore allow control over Q-factor and mode spacing. The symmetry phase diagram for pairs of originally degenerate, symmetry-protected BICs is presented in Fig. 3. The values for Q-factors and mode splitting correspond to the eigenvalue simulation results for the E\({}_{2}^{(1)}\) modes of a silicon metasurface. Here, the notation E\({}_{2}^{(n)}\) denotes the nth pair of symmetry-protected degenerate BICs. As discussed, when no symmetry breaking is present the modes making up the E2 irreducible representation of the p6mm triangular lattice form a pair of degenerate, symmetry-protected BICs, and therefore are fully decoupled from free space (Q = ∞).

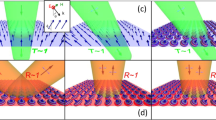

a Symmetry phase diagram for deforming resonators into triangles and contracting the lattice. The deformations determine the splitting and Q-factors for the E\({}_{2}^{(1)}\) modes of a silicon metasurface. When the resonator is deformed into a triangle, only C2 symmetry is broken resulting in two degenerate quasi-BICs. The Q-factors can be controlled by the resonator symmetry-breaking parameter (S). Correspondingly, when the lattice is contracted in one direction two non-degenerate BICs are formed since only C3 symmetry is broken. With these two symmetry-breaking parameters it is possible to design a lattice with cm Cs symmetry capable of having non-degenerate quasi-BICs with arbitrary splitting and Q-factors. b Field profiles for the four symmetry phases.

A new symmetry phase occurs when only resonator deformations are present (δ = 0 nm and S > 0). Since the triangular resonators preserve C3 symmetry, the lattice is reduced to the p31m space group which poses a symmetry-guaranteed degeneracy. Combining this symmetry guarantee with the fact that the metasurface is not C2 symmetric, we can characterize this symmetry phase as having degenerate quasi-BICs. (Specifically, the modes making up the E2 irreducible representation are continued into the E irreducible representation). As the deformation is increased, the Q-factor can be continuously decreased. Increasing the resonator deformation parameter to 0.05 causes the calculated Q-factor to drop from ∞ to 3.3 × 105. Increasing the resonator deformation parameter even further to 0.99 results in a Q-factor of 714.

A separate symmetry phase occurs when the lattice is contracted along one axis (δ > 0 nm and S = 0) since the triangular lattice is reduced to a lattice belonging to the cmm space group. For this space group, the modes of the E2 irreducible representation are reduced into non-degenerate symmetry-protected BICs (even with respect to C2). (The modes making up the E2 irreducible representation are continued into to the one-dimensional A1 and A2 irreducible representations.) As the degeneracy is no longer protected by symmetry, the frequencies of the modes begin to split. Therefore, this symmetry phase can be characterized as having two non-degenerate BICs. Eigenvalue simulations predict that by increasing the lattice deformation from 50 to 200 nm the mode splitting can be increased from 22 to 107 nm demonstrating the continuous tunability of mode splitting in this symmetry phase using lattice contraction.

When both lattice and resonator deformations are present (δ > 0 nm and S > 0), the triangular lattice is reduced to a lattice belonging to the cm space group. Under this symmetry reduction, the degeneracy is no longer guaranteed by symmetry and the modes can couple to the radiative continuum in the environment. This means that the modes in this phase can be characterized as non-degenerate quasi-BICs with Q-factors and splitting controlled by lattice and resonator deformations respectively. (Specifically, the E2 irreducible representation is reduced into the one-dimensional A and B irreducible representations). Since both C2 and C3 rotational symmetries are broken, the two quasi-BICs are no longer required to have the same Q-factors. Because of this, Fig. 3a presents the mean, maximum, and minimum Q-factors for the two E\({}_{2}^{(1)}\) modes of a silicon metasurfaces. As the lattice deformation is increased the difference between the Q-factors increases.

To corroborate the numerical predictions from eigenvalue simulations, we performed near-normal incidence reflectance measurements using unpolarized light on the series of metasurfaces with symmetry-breaking parameters spanning the four symmetry phases. Representative scanning electron micrographs for the four symmetry phases are presented in Fig. 4a. As predicted, when no symmetry breaking was present (δ = 0 nm and S = 0) the E\({}_{2}^{(1)}\) and E\({}_{2}^{(2)}\) modes were not observable in simulated and measured reflectance measurements (Fig. 4b, c). Furthermore, when no lattice deformation was present and the resonators were deformed (S > 0) the E(1) and E(2) modes became observable in simulated and measured reflectance spectra (Fig. 4b, c). By increasing the strength of the resonator deformation parameter (S) the peak reflectance of the degenerate quasi-BICs increased, but at the cost of reduced Q-factor. In this experimental demonstration, we observed a maximum Q-factor of 730 at δ = 0 nm and S = 0.4. The observed Q-factor decreased to 380 when the resonator deformation parameter was increased to 0.99. Compared to simulations, the observed Q-factors were below predicted values. Furthermore, the experimental Q-factor tuning range was significantly smaller than the predicted tuning range. Both of these discrepancies can be attributed to radiative damping from imperfection induced symmetry breaking and non-radiative damping. The measured Q-factors are consistent with an imperfection and non-radiative limited Q-factor ≈ 840. Nevertheless, our experimental measurements demonstrate that C2 symmetry breaking and C3 symmetry-preserving resonator deformations allow the Q-factor to be engineered while maintaining the symmetry-guaranteed modal degeneracy. When only lattice deformations were present (δ > 0 nm and S = 0) no splitting could be measured from simulated or measured reflectance spectra (Fig. 4b, c) since the modes are non-degenerate BICs that are fully decoupled from free space. Consequently, both resonator and lattice deformations were necessary to experimentally confirm predicted mode splitting.

a Scanning electron micrographs of fabricated silicon metasurfaces with designs for the four regimes of resonator deformation into a triangle and/or lattice contraction. Simulations (b) and measurements (c) of unpolarized reflectance for resonator and lattice deformations of the silicon metasurface. When no lattice deformation is present (δ = 0 nm) and the resonators are cylinders (S = 0) no modes are visible. If the resonators are deformed into triangles two peaks appear from degenerate quasi-BICs from the E\({}_{2}^{(1)}\) and E\({}_{2}^{(2)}\) modes. If the lattice is deformed (δ > 0 nm) the degeneracy of the quasi-BICs is lifted allowing four modes to be observed. As the deformation is increased the mode splitting increases. At any deformation, the resonators can be deformed into cylinders (S = 0) which forms two sets of non-degenerate BICs. Since these modes are true BICs they are fully decoupled from the far-field and no longer observable. d Experimental mode splitting and Q-factor tuning range from reflectance measurements.

Using the experimental reflectance measurements, we retrieved the Q-factors and mode splittings to characterize the experimental tunability range. The experimental tunability range is shown in Fig. 4d. By controlling the resonator and lattice deformations we tuned the Q-factor by almost a factor of two and the mode splitting from 2 to 110 nm. Compared to simulations, the average mode wavelength differed by 47 nm, but the mode splitting only differed from simulations by 2 nm on average, with a maximum deviation of 4 nm.

Combined together, the mode splitting and Q-factor tunability illustrate the potential for symmetry-protected degenerate BICs to enable the design of arbitrarily close high-Q modes. In particular, this experimental demonstration validates one of the main features of our design paradigm, that the rotational symmetry of the system guarantees the degeneracy of the metasurface states without requiring any fine-tuning. Even though there are discrepancies between the central frequency of the simulated and experimentally observed systems, the frequency splitting is predictable and robust. This robustness stands in stark contrast to the fragility of accidental degeneracies where there is no general guarantee for how the two accidentally degenerate BICs respond to perturbations. For accidental degeneracies there are two optimal responses to perturbations that can occur, one where the frequencies of both modes shift together equally (preserving the degeneracy) and another where the frequencies shift equally in opposite directions (preserving the center frequency). These optimal responses are not guaranteed and can only result from fine-tuning. Therefore, in general neither the degeneracy nor center frequency will be preserved when accidentally degenerate BICs are perturbed. The robustness of symmetry-protected degenerate BICs arises from the fact that both modes are symmetry-guaranteed to shift equally when the system is perturbed in a way that preserves C3 symmetry (i.e., isotropic refractive index, resonator thickness, or resonator diameter). This robustness combined with independent control of Q-factor and splitting, make symmetry-protected degenerate BICs an ideal starting point for designing metasurfaces with arbitrarily close high-Q modes.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed a general approach using principles rooted in group theory to create BICs where not only are lifetimes (and thus Q-factors) protected by symmetry but also degeneracies leading to the creation of symmetry-protected degenerate BICs. Based on this design, we experimentally proved that symmetry-protected degenerate BICs facilitate the design of high-Q modes with arbitrary frequency splitting. Furthermore, we experimentally demonstrated the ability to control Q-factor and frequency splitting through two classes of symmetry deformations. Moreover, our experimental demonstration provides explicit verification of one of the main advantages of our approach—fabrication imperfections only yielded significant changes to the average properties of both modes, not their relative properties. While we implemented this design paradigm in dielectric metasurfaces, it can be extended to other nanophotonic material platforms. For example, applying our design methodology to metasurfaces with high second-order susceptibilities has the potential to enable the creation of complex quantum states through SPDC37. Further extensions to our design paradigm may enable enhanced polarization control (specifically chirality) by breaking the remaining mirror symmetry planes. This chirality may lead to new methods for designing single-fed circularly polarized RF antennas60. These extensions have the potential to increase the dimensionality of symmetry phase diagrams allowing for increased control over the optical responses of metasurfaces. Looking beyond optical metasurfaces, our design paradigm provides a path for the creation of near degenerate mechanical BICs for phonon trapping61,62,63. Altogether, these future directions show the potential for using symmetry-based approaches for creating and controlling structures with nearly degenerate BICs.

Methods

Near-normal reflectance measurements

We used a homemade near-IR microscope for near-normal reflectance measurements. The illumination source was a stabilized tungsten halogen lamp. To illuminate and collect at low angles of incidence we used a 1.25 mm aperture to reduce the entrance pupil of a 50 mm focal length plano-convex lens leading to a NA of 0.015 with an angle of incidence less than 1°. The collected reflectance spectrum was directed via a fiber to the entrance slit of a grating spectrometer (Acton, Spectra Pro 2500i). We used a liquid nitrogen cooled InGaAs photodiode array to measure reflectance spectra. We used the reflectance spectrum from a silver mirror to normalize all measured reflectance spectra.

Nanofabrication

The fabrication of silicon metasurfaces began with JGS2 grade fused silica substrates. We deposited a thin film of Al2O3 (10 nm) and silicon (200 nm) through electron-beam evaporation. The Al2O3 layer was used an etch stop layer. The samples were then annealed using a rapid thermal anneal (Jipelec, Jetfirst) at 900 °C for 5 min to reduce optical losses in the thin film. An electron-beam resist (ZEP520A) was deposited by spin coating for electron-beam lithography. An anti-charging coating (DisChem Inc., DisCharge) was applied by spin coating to prevent charging during lithography. A 100 keV electron-beam lithography system (JEOL, JBX-6300FS) was used for pattern generation with the ZEP520A pattern developed by n-amyl acetate for 2 min. The pattern was transferred to the silicon through reactive ion etching (PlasmaTherm, SLR) using a mixture of SF6 (33 sccm) and C4F8 (77 sccm) at a working pressure of 10 mT with capacitive and inductive powers of 20 and 750 W, respectively. The remaining resist was removed with hot (60 °C) NMP for 1 h followed by a final O2 plasma descum.

Electromagnetic simulations

All full-wave electromagnetic eigenvalue simulations were performed with the finite element method using COMSOL Multiphysics. Far-field reflectance simulations were performed using finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations using Lumerical FDTD.

Symmetry-breaking deformations

The deformation from a circle to a square is given by Equation (1). To minimize the shifting of the modes while tuning the symmetry-breaking parameter, the diameters was scaled using the area of the full-circle to full-square deformation with the same symmetry-breaking parameter.

The deformation from a circle to a triangle is given by Equation (2). To minimize the shifting of the modes while tuning the symmetry-breaking parameter, the diameter was scaled to keep the area constant as a function of symmetry-breaking parameter.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Liu, S. et al. An all-dielectric metasurface as a broadband optical frequency mixer. Nat. Commun. 9, 2507 (2018).

Yuan, L. & Lu, Y. Y. Strong resonances on periodic arrays of cylinders and optical bistability with weak incident waves. Phys. Rev. A 95, 023834 (2017).

Han, S. et al. All-dielectric active terahertz photonics driven by bound states in the continuum. Adv. Mater. 31, 1901921 (2019).

Karl, N. et al. Frequency conversion in a time-variant dielectric metasurface. Nano Lett. 20, 7052–7058 (2020).

Kodigala, A. et al. Lasing action from photonic bound states in continuum. Nature 541, 196–199 (2017).

Contractor, R., Noh, W., Le-Van, Q. & Kanté, B. Doping-induced plateau of strong electromagnetic confinement in the momentum space. Opt. Lett. 45, 3653–3656 (2020).

Bulgakov, E. N. & Sadreev, A. F. Bound states in the continuum in photonic waveguides inspired by defects. Phys. Rev. B 78, 075105 (2008).

Plotnik, Y. et al. Experimental observation of optical bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 183901 (2011).

Hsu, C. W. et al. Observation of trapped light within the radiation continuum. Nature 499, 188–191 (2013).

Hsu, C. W., Zhen, B., Stone, A. D., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Bound states in the continuum. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–13 (2016).

Bogdanov, A. A. et al. Bound states in the continuum and Fano resonances in the strong mode coupling regime. Adv. Photonics 1, 016001 (2019).

Overvig, A. C., Malek, S. C., Carter, M. J., Shrestha, S. & Yu, N. Selection rules for quasibound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. B 102, 035434 (2020).

Joseph, S., Pandey, S., Sarkar, S. & Joseph, J. Bound states in the continuum in resonant nanostructures: an overview of engineered materials for tailored applications. Nanophotonics 10, 4175–4207 (2021).

Vaidya, S., Benalcazar, W. A., Cerjan, A. & Rechtsman, M. C. Point-defect-localized bound states in the continuum in photonic crystals and structured fibers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 023605 (2021).

Imada, M. et al. Coherent two-dimensional lasing action in surface-emitting laser with triangular-lattice photonic crystal structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 316–318 (1999).

Meier, M. et al. Laser action from two-dimensional distributed feedback in photonic crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 7–9 (1999).

Ha, S. T. et al. Directional lasing in resonant semiconductor nanoantenna arrays. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 1042–1047 (2018).

Jin, J. et al. Topologically enabled ultrahigh-Q guided resonances robust to out-of-plane scattering. Nature 574, 501–504 (2019).

Wu, M. et al. Room-temperature lasing in colloidal nanoplatelets via mie-resonant bound states in the continuum. Nano Lett. 20, 6005–6011 (2020).

Hwang, M.-S. et al. Ultralow-threshold laser using super-bound states in the continuum. Nat. Commun. 12, 4135 (2021).

Foley, J. M., Young, S. M. & Phillips, J. D. Symmetry-protected mode coupling near normal incidence for narrow-band transmission filtering in a dielectric grating. Phys. Rev. B 89, 165111 (2014).

Cui, X., Tian, H., Du, Y., Shi, G. & Zhou, Z. Normal incidence filters using symmetry-protected modes in dielectric subwavelength gratings. Sci. Rep. 6, 36066 (2016).

Gorkunov, M. V., Antonov, A. A., Tuz, V. R., Kupriianov, A. S. & Kivshar, Y. S. Bound states in the continuum underpin near-lossless maximum chirality in dielectric metasurfaces. Adv. Optical Mater. 9, 2100797 (2021).

Vaity, P. et al. Polarization-independent quasibound states in the continuum. Adv. Photonics Res. 3, 2100144 (2022).

Doeleman, H. M., Monticone, F., den Hollander, W., Alù, A. & Koenderink, A. F. Experimental observation of a polarization vortex at an optical bound state in the continuum. Nat. Photonics 12, 397–401 (2018).

Liu, M. & Choi, D.-Y. Extreme Huygens’ metasurfaces based on quasi-bound states in the continuum. Nano Lett. 18, 8062–8069 (2018).

Wang, B. et al. Generating optical vortex beams by momentum-space polarization vortices centred at bound states in the continuum. Nat. Photonics 14, 623–628 (2020).

Gansch, R. et al. Measurement of bound states in the continuum by a detector embedded in a photonic crystal. Light. Sci. Appl. 5, e16147–e16147 (2016).

Romano, S. et al. Label-free sensing of ultralow-weight molecules with all-dielectric metasurfaces supporting bound states in the continuum. Photonics Res. 6, 726–733 (2018).

Romano, S. et al. Tuning the exponential sensitivity of a bound-state-in-continuum optical sensor. Opt. Express 27, 18776–18786 (2019).

Wang, W. et al. Plasmonic hot-electron photodetection with quasi-bound states in the continuum and guided resonances. Nanophotonics 10, 1911–1921 (2021).

Pichugin, K. N. & Sadreev, A. F. Frequency comb generation by symmetry-protected bound state in the continuum. JOSA B 32, 1630–1636 (2015).

Minkov, M., Gerace, D. & Fan, S. Doubly resonant χ(2) nonlinear photonic crystal cavity based on a bound state in the continuum. Optica 6, 1039–1045 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. High-Q quasibound states in the continuum for nonlinear metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 253901 (2019).

Wang, T., Li, Z. & Zhang, X. Improved generation of correlated photon pairs from monolayer WS2 based on bound states in the continuum. Photonics Res. 7, 341–350 (2019).

Parry, M. et al. Enhanced generation of nondegenerate photon pairs in nonlinear metasurfaces. Adv. Photonics 3, 055001 (2021).

Santiago-Cruz, T. et al. Resonant metasurfaces for generating complex quantum states. Science 377, 991–995 (2022).

Colom, R. et al. Enhanced four-wave mixing in doubly resonant Si nanoresonators. ACS Photonics 6, 1295–1301 (2019).

Xu, L. et al. Enhanced four-wave mixing from multi-resonant silicon dimer-hole membrane metasurfaces. N. J. Phys. 24, 035002 (2022).

Winful, H. G. & Marburger, J. H. Hysteresis and optical bistability in degenerate four-wave mixing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 36, 613–614 (1980).

Nakajima, H. & Frey, R. Observation of bistable reflectivity of a phase-conjugated signal through intracavity nearly degenerate four-wave mixing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 54, 1798–1801 (1985).

Schanne, P., Heinrich, H., Elsässer, W. & Göbel, E. O. Optical bistability and nearly degenerate four-wave mixing in a GaAlAs laser under intermodal injection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 61, 2135–2137 (1992).

Fujita, K. et al. Ultra-broadband room-temperature terahertz quantum cascade laser sources based on difference frequency generation. Opt. Express 24, 16357–16365 (2016).

Kim, J. H. et al. Double-metal waveguide terahertz difference-frequency generation quantum cascade lasers with surface grating outcouplers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 161102 (2018).

Fujita, K. et al. Recent progress in terahertz difference-frequency quantum cascade laser sources. Nanophotonics 7, 1795–1817 (2018).

Doskolovich, L. L. et al. Resonant properties of composite structures consisting of several resonant diffraction gratings. Opt. Express 27, 25814–25828 (2019).

Cong, L. & Singh, R. Symmetry-protected dual bound states in the continuum in metamaterials. Adv. Optical Mater. 7, 1900383 (2019).

Gandhi, H. K., Laha, A. & Ghosh, S. Ultrasensitive light confinement: driven by multiple bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. A 102, 033528 (2020).

Wang, M., Li, B. & Wang, W. Symmetry-protected dual quasi-bound states in the continuum with high tunability in metasurface. J. Opt. 22, 125102 (2020).

Han, S. et al. Extended bound states in the continuum with symmetry-broken terahertz dielectric metasurfaces. Adv. Optical Mater. 9, 2002001 (2021).

Sadrieva, Z. F. et al. Transition from optical bound states in the continuum to leaky resonances: role of substrate and roughness. ACS Photonics 4, 723–727 (2017).

Ni, L., Jin, J., Peng, C. & Li, Z. Analytical and statistical investigation on structural fluctuations induced radiation in photonic crystal slabs. Opt. Express 25, 5580–5593 (2017).

Maslova, E. E., Rybin, M. V., Bogdanov, A. A. & Sadrieva, Z. F. Bound states in the continuum in periodic structures with structural disorder. Nanophotonics 10, 4313–4321 (2021).

Inui, T., Tanabe, Y. & Onodera, Y. Group Theory and Its Applications in Physics (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Sakoda, K. Optical Properties of Photonic Crystals (Springer Science & Business Media, 2004).

Sakoda, K. Symmetry, degeneracy, and uncoupled modes in two-dimensional photonic lattices. Phys. Rev. B 52, 7982–7986 (1995).

Wang, X., Wang, J., Zhao, X., Shi, L. & Zi, J. Realizing tunable evolution of bound states in the continuum and circularly polarized points by symmetry breaking. ACS Photonics, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.2c01522 (2022).

Yoda, T. & Notomi, M. Generation and annihilation of topologically protected bound states in the continuum and circularly polarized states by symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 053902 (2020).

Cerjan, A. et al. Observation of bound states in the continuum embedded in symmetry bandgaps. Sci. Adv. 7, eabk1117 (2021).

Wang, Z. & Dong, Y. Circularly polarized antennas inspired by dual-mode SIW cavities. IEEE Access 7, 173007–173018 (2019).

Zhao, M. & Fang, K. Mechanical bound states in the continuum for macroscopic optomechanics. Opt. Express 27, 10138–10151 (2019).

Tong, H., Liu, S., Zhao, M. & Fang, K. Observation of phonon trapping in the continuum with topological charges. Nat. Commun. 11, 5216 (2020).

Sadreev, A., Bulgakov, E., Pilipchuk, A., Miroshnichenko, A. & Huang, L. Degenerate bound states in the continuum in square and triangular open acoustic resonators. Phys. Rev. B 106, 085404 (2022).

Acknowledgements

I.B. and C.F.D. acknowledge support from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering (BES 20-017574 I.B.). A.C. acknowledges support from the Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at Sandia National Laboratories. This work was performed, in part, at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science. Sandia National Laboratories is a multi-mission laboratory managed and operated by National Technology and Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International, Inc., for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-NA0003525. This paper describes objective technical results and analysis. Any subjective views or opinions that might be expressed in the paper do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Energy or the United States Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C. and C.F.D. initiated this research. C.F.D. designed, fabricated, and characterized the samples. All authors analyzed and interpreted data. A.C. and I.B. supervised the project. C.F.D. and A.C. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Almas Sadreev and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Doiron, C.F., Brener, I. & Cerjan, A. Realizing symmetry-guaranteed pairs of bound states in the continuum in metasurfaces. Nat Commun 13, 7534 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35246-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35246-w

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.