Abstract

In transition metal dichalcogenides, valley depolarization through intervalley carrier scattering by zone-edge phonons is often unavoidable. Although valley depolarization processes related to various acoustic phonons have been suggested, their optical verification is still vague due to nearly degenerate phonon frequencies on acoustic phonon branches at zone-edge momentums. Here we report an unambiguous phonon momentum determination of the longitudinal acoustic (LA) phonons at the K point, which are responsible for the ultrafast valley depolarization in monolayer MoSe2. Using sub-10-fs-resolution pump-probe spectroscopy, we observed coherent phonons signals at both even and odd-orders of zone-edge LA mode involved in intervalley carrier scattering process. Our phonon-symmetry analysis and first-principles calculations reveal that only the LA phonon at the K point, as opposed to the M point, can produce experimental odd-order LA phonon signals from its nonlinear optical modulation. This work will provide momentum-resolved descriptions of phonon-carrier intervalley scattering processes in valleytronic materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phonon-mediated intervalley scattering is a central process in photoexcited carrier dynamics of valleytronic materials1,2. In transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), a prototypical family of valleytronic materials, it has been reported that the degree of valley polarization exhibits ultrafast decays in picosecond time scale due to intervalley carrier-phonon scattering3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. In such scattering processes, zone-edge acoustic phonons play a definitive role in transferring photoexcited carriers from one valley to another; acoustic phonons at the K-point scatter carriers from K to K′ valleys (or K′ to K valleys) and those at the M point scatter carriers from Q to K′ valleys (or Q′ to K valleys) due to the momentum conservation (see Fig. 1a). While numerous optical experiments have been performed to probe zone-edge acoustic phonons by using resonant Raman scattering13,14,15,16,17,18, photoluminescence excitation4,19, and coherent phonon generation20,21,22, the phonon momentum have often remained largely unidentified because the frequencies of phonon modes at the K and M points TMDs are nearly degenerate (see Table 1). For instance, the LA phonon frequencies at the M and K points in Mo-based TMDs (MoS2 and MoSe2) and the ZA phonon frequencies at the M and K points of W-based TMDs (WS2 and WSe2) are nearly degenerated (frequency differences <0.1 THz = 0.4 meV), which are hardly resolved with the phonon frequencies obtained by typical linear spectroscopies.

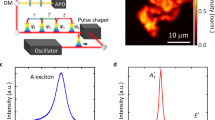

a The atomic structure of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) and valley scattering processes mediated by XA(K) and XA(M) phonons (XA: LA, TA, and ZA). b Schematic illustration of the pump-probe detection of the ultrafast optical response of monolayer MoSe2 modulated by coherent phonon generation. c The experimental differential transmittance (upper panel) and its Fourier-transformed spectrum (lower panel) exhibiting coherent phonon signals in first-order A1′(Γ) mode and first- and higher orders of the LA mode. d The calculated phonon dispersion of monolayer MoSe2 obtained by density-functional theory. The A1′(Γ), LA(M), and LA(K) modes observed at 7.33, 4.75, and 4.79 THz are highlighted.

Results

Coherent phonon measurement

Here, we report on unambiguous determination of the phonon mode that dominates intervalley scattering in MoSe2: the K-point LA phonon. This conclusion was obtained through phonon-symmetry analysis and first-principles calculations, combined with nonlinear coherent phonon (CP) measurement, whose principle is schematically shown in Fig. 1b. The transmission modulations induced by CPs were monitored in the time domain, which was Fourier transformed to generate a CP spectrum (see Fig. 1c). On the basis of comparison with the calculated phonon dispersions of monolayer MoSe2 in Fig. 1d, we assign the observed CP peaks at 4.65 and 7.37 THz to the first-order LA mode and the optical A1′(Γ) mode, while the higher-frequency features (>10 THz) are attributed to multiple-order LA phonon modes: 2LA, 3LA, and 4LA. By contrast, the optical A1′(Γ) mode only shows a first-order CP signal (7.37 THz). This implies that the particular zone-edge LA phonon mode produced by ultrafast intervalley scattering possesses a characteristic nonlinear optical response, while the optical A1′(Γ) phonon only induces linear optical modulation. In what follows we show that this nonlinear optical response is the key feature that conclusively tells us that the generated LA phonons are at the K point, not at the M point.

Phonon displacements and symmetry

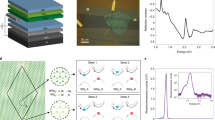

To clarify the nonlinear optical response and zone-edge LA phonon momentum intimately related to their optical processes, we first present a theoretical exploration of the lattice deformations and deformed atomic structures of the A1′(Γ), LA(K), and LA(M) phonon modes in monolayer MoSe2 using density-functional theory. Figure 2 shows lattice deformations and derived optical modulations of the A1′(Γ), LA(K) and LA(M) modes in monolayer MoSe2, with atomic displacements of the phonon modes calculated by density-functional theory (see Methods). As all monolayer TMDCs have the same type of atomic structure, the same description can be generally applied to other TMDCs. Figure 2a, b shows the lattice deformations and displaced atomic structures induced by the phonon modes, with Q(t) denoting the degree of atomic displacements at time t, which oscillates with the phonon frequency. We illustrate the displaced atomic structures of monolayer MoSe2 with lattice deformations of Q(t) = +Q and −Q, where + and − signs denote directions of the phonon vibrations. While all phonon modes deform the lattice structure from the equilibrium structure, we found a significant difference between lattice deformations in the LA(M) mode and both the A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes. +Q and −Q displacements induced by the A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes result in different atomic deformations, as shown in Fig. 2a, but those of the LA(M) mode can be superimposed after the lattice translation shown in Fig. 2b. Thus, +Q and −Q displacements induced by the A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes are asymmetric, but those of the LA(M) modes always induce symmetric atomic structures.

a Asymmetric lattice deformations of the A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes. Q(t) represents the atomic displacements oscillating over time. The + and − signs of Q(t) denote the directions of vibrations. Lattice deformations of the A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes are asymmetric because the atomic structures with +Q and −Q displacements are not identical. b Symmetric lattice deformations of the LA(M) mode. In contrast with the asymmetric A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes, the lattice deformations of +Q and −Q displacements of the LA(M) mode superimposed after the lattice translation are identical. c Lattice oscillations of the asymmetric A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes, with derived optical responses and CP spectra. As +Q and −Q displacements yield asymmetric atomic structures, nonlinear optical modulations with respect to the phonon frequency ω can be recorded as higher-order CP signals. d Lattice oscillation of the symmetric LA(M) mode, the derived optical response and CP spectrum exhibiting only even orders of the phonon frequency, due to the even function behavior of the optical response.

The optical modulations induced by the coherent phonon generation of asymmetric and symmetric lattice deformations of the A1′(Γ), LA(K), and LA(M) modes and associated CP spectra are shown in Fig. 2c, d. Deformations of the atomic structure of monolayer MoSe2 by cosinusoidal lattice oscillations induced by coherent phonon vibrations are illustrated in the left-lower panels in Fig. 2c, d. As the asymmetric lattice deformations of the A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes differ, the differential transmittance ΔT/T0 at the +Q and −Q displacements should have different values, as shown in Fig. 2c. The time evolution of ΔT/T0 is expected to oscillate with the phonon frequency ω. However, its shape is not a perfect cosinusoidal wave, leading to induction of the higher orders of ω such as 2ω, 3ω, 4ω, and so on, as obtained by Fourier transformation. By contrast, linear behavior of the differential transmittance ΔT(Q)/T0 can derive a perfect cosinusoidal optical modulation ΔT(t)/T0 ∝ Q(t) ∝ cos(ωt + φ) (where φ is a phase shift), yielding only first-order CP signals at the phonon frequency ω. This indicates that the nonlinear optical modulation of LA(K) modes is responsible for single and higher-order CP signals. On the other hand, because LA(M) phonons deform the atomic structure in the same crystallographic structure at both the +Q and −Q displacements, the differential transmittance ΔT(Q)/T0 should be an even function, i.e., ΔT( + Q)/T0 = ΔT(−Q)/T0, as illustrated in Fig. 2d. Suppose that the ΔT(Q)/T0 has been expanded with a polynomial of Q, i.e., ΔT(Q)/T0 = a0 + a1Q + a2Q2 + a3Q3 + a4Q4 …, the odd-order coefficients (for example a1 and a3) must be zero for the LA(M) mode due to the even function behavior of ΔT(Q)/T0. If an atomic displacement Q(t)∝sin(ωt + φ) is plugged into the ΔT(Q)/T0, the differential transmittance exhibits only even orders of the phonon frequency ω (see Methods for details). This indicates that the LA(M) mode is not responsible for the odd-order LA signals, our experimental CP spectrum is therefore attributable to dominant generation of LA(K) phonons, which are responsible for phonon-mediated ultrafast intervalley carrier scattering in monolayer MoSe27,20,23. In turn, the striking difference between the LA(K) and A1′(Γ) modes observed in the CP spectrum is attributable to the linear and nonlinear behavior of the differential transmittance ΔT(Q)/T0. Seeking numerical details of the differential transmittance associated with the CP spectra, we next explicitly evaluate the differential transmittance induced by the A1′(Γ), LA(K) and LA(M) coherent phonons from the absorption spectra calculations using density-functional theory.

Phonon-mediated optical modulation

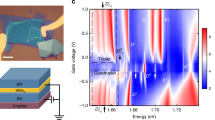

Figure 3 presents the transmittance spectra, the differential transmittance ΔT/T0 and simulated CP spectra of the A1′(Γ), LA(K), and LA(M) modes calculated by linear-response time-dependent density-functional theory (LR-TDDFT) using the HSE06 functional including spin-orbit coupling (SOC). We here quantify the degree of atomic displacements Q by introducing a generalized atomic displacement defined as Q2 = Σmidi2 evaluated for the MoSe2 formular unit (three atoms), where mi and di are the mass and displacement of the i-th atom in atomic mass units (amu) and angstroms (Å), respectively. The calculated transmittance with the atomic displacement of each phonon mode is shown in the left panels of Fig. 3. The A-exciton position of the calculated transmittance spectra is calibrated to the experimental value20,24. The asymmetric A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes modulate each transmittance spectrum with +Q and −Q displacements shown in Fig. 3a, b (magenta and blue lines, respectively), while the transmittance spectra associated with +Q and −Q displacements of the LA(M) phonon are the same (Fig. 3c). These numerical results corroborate our findings derived from the asymmetric and symmetric behaviors of the A1′(Γ), LA(K), and LA(M) modes previously explained and illustrated in Fig. 2. Using the calculated transmittance spectra, the differential transmittance is obtained by the overlap integration of the experimental laser spectrum and calculated transmittance (see Methods). The calculated differential transmittance ΔT(Q)/T0 is shown in the middle panels of Fig. 3. Differences in behavior of ΔT(Q)/T0 among the three phonon modes can be clearly seen. The ΔT(Q)/T0 of the A1′(Γ) mode responds almost linearly with respect to the displacement Q (in Fig. 3a), whereas the LA(K) mode exhibits a highly nonlinear modulation on ΔT(Q)/T0 (in Fig. 3b). The LA(M) mode exhibits the symmetric ΔT(Q)/T0 due to an even function of the displacement Q (in Fig. 3c). We note that the A1′(Γ) mode reduces and increases the band gap of monolayer MoSe2 with +Q and −Q displacements, respectively, whereas both LA(K) and LA(M) modes with +Q and −Q displacements only reduce the band gap.

The optical modulations are induced by: a A1′(Γ), b LA(K), and c LA(M) modes. Left panel: transmittance spectra of monolayer MoSe2 with and without the lattice deformations (Q = ± 0.1, ±0.3, and 0, respectively) and the laser spectrum (gray shading) used in the experiment. Middle panel: the differential transmittance ΔT(Q)/T0 as a function of the generalized displacement Q evaluated by integrating the experimental laser spectrum with the calculated transmittance spectra (see Methods). Right panel: simulated time-evolved differential transmittance ΔT(t)/T0 and associated CP spectra obtained by Fourier transformation of ΔT(t)/T0.

By comparing the calculated ΔT(Q)/T0 in Fig. 3 to the experimentally determined differential transmittance in Fig. 1c, the range of the displacement Q of each phonon can be approximately estimated. The gray shading in the ΔT(Q)/T0 spectra presented in middle panels of Fig. 3 show the experimental range of the differential transmittance, ΔT/T0, with maximum and minimum values of around 1 × 10−3. This corresponds to Q values of the A1′(Γ), LA(K) and LA(M) modes of 0.05, 0.2, and 0.15 amu1/2 Å, respectively. We set these maximum displacements, Q0, as the amplitudes of cosinusoidal lattice motions of the phonon modes, as shown in the right-upper panels in Fig. 3a–c. Evolutions with time of the differential transmission ΔT(t)/T0 are then readily obtained from the calculated ΔT(Q)/T0 by inserting Q(t) = Q0cosωt as the time-dependent displacement Q. Simulated CP spectra of the A1′(Γ), LA(K) and LA(M) modes are obtained from Fourier transformations of ΔT(t)/T0, as shown in the right-bottom panels of Fig. 3a–c. The simulated CP spectra explain the experimental CP spectra well, as follows. The first-order peak dominates the CP spectrum of the A1′(Γ) mode because its atomic motion monotonically increases and decreases the band gap of monolayer MoSe2. The higher-order CP signals of LA phonons originate from nonlinear behavior of the optical modulation induced by LA(K) phonons. Activation of the LA(M) mode in the CP spectrum is strictly limited to its even orders due to the symmetric lattice deformations of the +Q and −Q displacements. Thus, our numerical simulation resolves the acoustic momentum of LA phonons through the nonlinear and higher-order optical responses of monolayer MoSe2 induced by the LA(K) mode.

We present a quantitative comparison of the experimental and simulated spectra in Fig. 4. To include the fast decay of the experimental ΔT(t)/T0, the single exponential decay of 2 ps has been imposed on the simulated ΔT(t)/T0 modulated by the LA(K) mode. The simulated ΔT(t)/T0 spectrum obtained with the combination of the LA(K) and A1′(Γ) modes quantitively reproduces the experimental ΔT(t)/T0 spectrum, as shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 4a. Here, amplitudes Q0 of the A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes are set to 0.003 and 0.2 amu1/2 Å, whose atomic displacements of the A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes are presented in Table 2. The large atomic displacements of the LA(K) mode compared to that of the A1′(Γ) mode indicates that intervalley scattering process would dominantly occur compared to the impulsive stimulated Raman scattering (ISRS)21,23. We showcase the simulated Fourier-transformed CP spectrum compared to the experimental CP spectrum in Fig. 4b, which reproduces overall characteristics of the experimental CP spectrum. The simulated spectrum comes from a combination of A1′(Γ) mode and LA(K) mode having a rapid damping of 2 ps, which could result in asymmetric shapes of Fourier signals. Some marginal inconsistencies remain e.g., relative intensity of the 3LA(K) mode and small variation of the 2LA(K) and 4LA(K) frequencies, which might be attributed to transient phonon frequency chirping through light-induced lattice strain.

a Simulated differential transmittance ΔT(t)/T0 of the A1′(Γ) mode (upper panel), LA(K) mode (middle panel) and combination of the LA(K) and A1′(Γ) modes (bottom panel). Simulation parameters are shown in the insets. b Comparison of experimental and simulated CP spectra. The latter was obtained from the Fourier transformation of the differential transmittance ΔT(t)/T0 of the combination of LA(K) and A1′(Γ) modes (bottom panel of a).

Discussion

Finally, we briefly discuss the generation mechanism of the LA(K) phonon in monolayer MoSe2 observed in our experiment. It has been previously reported that K-point phonon generations in TMDs can involve multiple acoustic phonon branches. For instance, the LA(K) phonon has been widely detected in several TMDs10,11,25. In contrast, the coherent ZA(K) phonon generation has been reported for monolayer MoSe2 when the spin-flip intervalley scattering occurs in between lowest energy K-point valleys with opposite spins, resulting in the generation of the flexure (out-of-plane) ZA(K) phonons20. Because our laser spectrum (cf. gray shadings in Fig. 3) spreads over a wide excitation energy range which includes high energy excitations over the lowest energy valleys, intervalley carrier-phonon scatterings are not limited to the spin-flip intervalley scattering as in Ref. 20 but includes spin-conserved intervalley scatterings. The predominant occurrence of spin-conserved intervalley scatterings over the spin-flip intervalley scatterings then leads to the generation of the in-plane LA(K) phonons in our experiment rather than the flexural ZA(K) phonons as in Ref. 20. This demonstrate that, since the generation mechanism of zone-corner acoustic phonons is intimately related to the carrier excitation energy and spin relaxation, the nonlinear optical response should present an essential clue for exploring the valley depolarization process of TMDs.

In summary, we demonstrate higher-order optical responses of coherent phonon generation in monolayer MoSe2 that identifies the momentum of the LA phonon. The symmetric analysis of lattice deformations of coherent phonons decodes the higher-order optical response of zone-edge acoustic coherent phonons, and the higher-order coherent LA signals can be attributed to LA(K) phonons. Our first-principles calculations enable quantitative analysis of coherent phonon generation of the A1′(Γ) and LA(K) modes, revealing that acoustic LA(K) phonon generation via intervalley scattering dominates over generation of the A1′(Γ) mode through ISRS processes. Our work unveils hidden physics of the higher-order optical responses of monolayer MoSe2, thus facilitating deterministic descriptions of ultrafast phonon-mediated carrier scattering processes in a wide range of valleytronic materials.

Methods

Experimental setup and sample

Coherent phonon experiments with a degenerate pump-probe configuration were performed using a sub-10-fs Ti:sapphire laser (VENTEON PulseONE) with 7.5 fs pulse duration, 90 MHz repetition rate and 300 mW output power. The spectrum of the laser ranges from 650 nm (1.91 eV) to 1050 nm (1.18 eV) (see gray shadings in Fig. 3). The laser output was divided into pump (100 mW) and probe (5 mW) beams, both of which were simultaneously focused on the sample at approximately a normal incidence using a parabolic mirror with 50 mm focal length. The diameter of the focus at the sample was 20 μm. An optical shaker with a 15 ps scanning range running at 20 Hz was placed in the pump beam path, and changes in transmitted probe pulses were detected using a Si photodiode. After subtraction of the intensity of the reference probe pulses, the signal was amplified with a SR560 transimpedance current amplifier. The amplified signal was collected with an analog-to-digital converter and analyzed with the position signal sent from the optical shaker. All the measurements were performed at room temperature.

The sample consisted of monolayer MoSe2 crystals grown by the chemical vapor deposition technique on a sapphire substrate. The triangular single crystals of monolayer MoSe2 with the typical size of 200 μm were confirmed by optical microscopy. We implemented the in-situ microscope at the sample position of the setup for coherent phonon experiment and confirmed that the pump and probe beams are shined on the monolayer region of the sample. The reported waveforms were repeatedly observed during the experiments, indicating that no degradation of the sample occurred during the experiments. The absorption peak of the A-exciton resonance was observed around 1.6 eV in our sample, which was confirmed by a conventional transmission spectrometer.

First-principles calculations

We calculated electronic and vibrational properties of monolayer MoSe2 using density-functional theory (DFT) with the projector augmented wave (PAW) method, implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)26,27,28,29. The kinetic energy cut-off of plane waves was set to 350 eV and a Γ-centered 12 × 12 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid was used for the primitive cell. For supercell calculations, Γ-centered 2 × 2 × 1 and 6 × 6 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grids were employed for 6 × 6 × 1 and \(\sqrt 3\,\times\, \sqrt 3\,\times\, 1\) supercells, respectively. The phonon dispersion of monolayer MoSe2 and atomic displacements of the A1′(Γ), LA(K), and LA(M) modes were calculated using the Phonopy package30. Force constants used in the phonon dispersion calculation were generated with DFT calculations of displaced 6 × 6 × 1 supercells of the monolayer MoSe2 primitive cell using the PBEsol functional31. Optical properties of monolayer MoSe2 with and without atomic displacements of the phonon modes were obtained from the optical calculations of linear-response time-dependent density-functional theory (LR-TDDFT) with the HSE06 kernel including the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) effect as implemented in the VASP package32. Transmittance spectra of monolayer MoSe2 were extracted using VASPKIT code from the real and imaginary dielectric functions of the LR-TDDFT results33.

Simulation of optical modulation and coherent phonon spectra

Integrated transmittance with a generalized atomic displacements Q are evaluated for monolayer MoSe2 as \(T(Q)\,=\,\int {\widetilde{T}}_{Q}(\epsilon )I(\epsilon )d\epsilon\), where ϵ is the excitation energy, \({\widetilde{T}}_{Q}(\epsilon )\) is the calculated transmittance spectra of monolayer MoSe2 using LR-TDDFT with generalized atomic displacement Q, and I(ϵ) is the experimental lager spectrum used in the pump-probe experiment. The generalized atomic displacements are estimated as Q2 = Σmidi2, where mi and di are the mass and displacement of the i-th atom in atomic mass units (amu) and angstroms (Å), respectively. A constant 0.1 eV downshift was applied to the excitation energy of the calculated transmittance \({\widetilde{T}}_{Q}(\epsilon )\) to adjust the A-exciton energy to the experimental value. The differential transmittance ΔT(Q)/T0 was calculated for various Q values with atomic displacements of A1′(Γ), LA(K), and LA(M) modes as ΔT(Q) = [T(Q) − T0]/T0, where ΔT(Q) and T0 are integrated transmittance spectra with generalized atomic displacements Q and Q = 0. The time-dependent differential transmittance ΔT(t)/T0 was obtained by giving a cosinusoidal oscillation Q(t) = Q0cosωt into the ΔT(Q)/T0. For actual calculations of ΔT(t)/T0, the differential transmittance ΔT(Q)/T0 of each phonon mode was expanded into a polynomial of Q up to 6th order by numerical fitting. Finally, a simulated coherent phonon spectrum of each phonon mode was obtained by Fourier transformation of ΔT(t)/T0.

Odd-order regulation of coherent phonon signals of the LA(M) mode

The differential transmission ΔT(Q)/T0 of the LA(M) mode is an even function which satisfies ΔT(+Q)/T0 = ΔT(−Q)/T0. Accordingly, the polynomial expansion of ΔT(Q)/T0 with respect to Q can be written as ΔT(Q)/T0 = a0 + a2Q2 + +a4Q4… (without odd orders of Q) where an is the nth-order coefficient. By giving Q(t) = Q0cosωt to ΔT(Q)/T0, the time-dependent differential transmission is ΔT(t)/T0 = a0 + a2cos2ωt + a4cos4ωt…. By adopting double angle identities of the cosine function cos2(ωt) = [1 + cos2(ωt)]/2 to cosn(ωt) terms, ΔT(t)/T0 can be reformulated into ΔT(t)/T0 = b0 + b2cos(2ω)t + b4cos(4ω)t…(where bn is the nth coefficient) whose Fourier transformation coefficients [the coherent phonon spectrum of the LA(M) mode] only have even orders of the phonon frequency ω, such as 2ω, 4ω, 6ω… excluding odd orders.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Mak, K. F., He, K., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Control of valley polarization in monolayer MoS2 by optical helicity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 494–498 (2012).

Zhu, H. et al. Observation of chiral phonons. Science 359, 579–582 (2018).

Baranowski, M. et al. Dark excitons and the elusive valley polarization in transition metal dichalcogenides. 2D Mater. 4, 025016 (2017).

Chow, C. M. et al. Phonon-assisted oscillatory exciton dynamics in monolayer MoSe2. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 1, 33 (2017).

Christiansen, D. et al. Phonon sidebands in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 187402 (2017).

Molina-Sanchez, A., Sangalli, D., Wirtz, L. & Marini, A. Ab Initio calculations of ultrashort carrier dynamics in two-dimensional materials: valley depolarization in single-layer WSe2. Nano Lett. 17, 4549–4555 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Intravalley spin-flip relaxation dynamics in single-layer WS2. Nano Lett. 18, 6882–6891 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Momentum-dark intervalley exciton in monolayer tungsten diselenide brightened via chiral phonon. ACS Nano 13, 14107–14113 (2019).

Brem, S. et al. Phonon-assisted photoluminescence from indirect excitons in monolayers of transition-metal dichalcogenides. Nano. Lett. 20, 2849–2856 (2020).

He, M. et al. Valley phonons and exciton complexes in a monolayer semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 11, 618 (2020).

Liu, E. et al. Multipath optical recombination of intervalley dark excitons and trions in monolayer WSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 196802 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. Polarization and time-resolved photoluminescence spectroscopy of excitons in MoSe2 monolayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 112101 (2015).

Berkdemir, A. et al. Identification of individual and few layers of WS2 using Raman Spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 3, 1755 (2013).

Gołasa, K. et al. Multiphonon resonant Raman scattering in MoS2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 092106 (2014).

Nam, D., Lee, J. U. & Cheong, H. Excitation energy dependent Raman spectrum of MoSe2. Sci. Rep. 5, 17113 (2015).

Soubelet, P., Bruchhausen, A. E., Fainstein, A., Nogajewski, K. & Faugeras, C. Resonance effects in the Raman scattering of monolayer and few-layerMoSe2. Phys. Rev. B 93, 155407 (2016).

Carvalho, B. R. et al. Intervalley scattering by acoustic phonons in two-dimensional MoS2 revealed by double-resonance Raman spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 8, 14670 (2017).

Li, J.-M. et al. Double resonance Raman scattering in single-layer MoSe2 under moderate pressure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 36, 048201 (2019).

Shree, S. et al. Observation of exciton-phonon coupling in MoSe2 monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 98, 035302 (2018).

Jeong, T. Y. et al. Valley depolarization in monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides with zone-corner acoustic phonons. Nanoscale 12, 22487–22494 (2020).

Jeong, T. Y. et al. Coherent lattice vibrations in mono- and few-layer WSe2. ACS Nano 10, 5560–5566 (2016).

Tornatzky, H., Gillen, R., Uchiyama, H. & Maultzsch, J. Phonon dispersion in MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 99, 144309 (2019).

Trovatello, C. et al. Strongly coupled coherent phonons in single-layer MoS2. ACS Nano 14, 5700–5710 (2020).

Kioseoglou, G., Hanbicki, A. T., Currie, M., Friedman, A. L. & Jonker, B. T. Optical polarization and intervalley scattering in single layers of MoS2 and MoSe2. Sci. Rep. 6, 25041 (2016).

Liu, E. et al. Valley-selective chiral phonon replicas of dark excitons and trions in monolayer WSe2. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 032007 (2019).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Paier, J., Marsman, M. & Kresse, G. Dielectric properties and excitons for extended systems from hybrid functionals. Phys. Rev. B 78, 121201 (2008).

Wang, V., Xu, N., Liu, J.-C., Tang, G. & Geng, W.-T. VASPKIT: A user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 267, 108033 (2021).

Acknowledgements

J.T. and I.K. were partly supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Nos. 20H05662 and 20H02653) and S.B. was supported by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Research Fellow (No. 202115353) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. J.T. is also grateful for support of the Mitsubishi Foundation (No. 202110024). J.K. acknowledges support by the Robert A. Welch Foundation through Grant No. C-1509. S.B. thanks the Iwaki Scholarship Foundation for support and H.R. is grateful for support from the Yokohama Kogyokai and Yokohama National University Rector’s strategic funding. Numerical calculations were performed at the Research Center for Computational Science at ISSP and Information Technology Center, the University of Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B., J.K., J.T. and I.K. conceived and coordinated this project. S.B., K.S. and H.R. performed first-principles calculations. K.M. and I.K. built the sub-10-fs pump-probe setup and performed the experiments. Y.S. X.Z., R.V., P.A. and J.K. synthesized monolayer MoSe2 and Ø.H., M.K. and T.N. characterized the samples. S.B., J.T., J.K and I.K. wrote this paper with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yi-Hsien Lee and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bae, S., Matsumoto, K., Raebiger, H. et al. K-point longitudinal acoustic phonons are responsible for ultrafast intervalley scattering in monolayer MoSe2. Nat Commun 13, 4279 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32008-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32008-6

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.