Abstract

The interoceanic exchange of water masses is modulated by flow through key oceanic choke points in the Drake Passage, the Indonesian Seas, south of Africa, and south of Tasmania. Here, we use the neodymium isotope signature (εNd) of cold-water coral skeletons from intermediate depths (1460‒1689 m) to trace circulation changes south of Tasmania during the last glacial period. The key feature of our dataset is a long-term trend towards radiogenic εNd values of ~−4.6 during the Last Glacial Maximum and Heinrich Stadial 1, which are clearly distinct from contemporaneous Southern Ocean εNd of ~−7. When combined with previously published radiocarbon data from the same corals, our results indicate that a unique radiogenic and young water mass was present during this time. This scenario can be explained by a more vigorous Pacific overturning circulation that supported a deeper outflow of Pacific waters, including North Pacific Intermediate Water, through the Tasman Sea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The exchange of water masses between ocean basins plays a key role in the volume transport and heat budgets of the global overturning circulation. The modern overturning circulation is characterized by strong southward export of deep waters from the North Atlantic into the Southern Ocean, as well as deep water formation in the high-latitude Southern Ocean1. Eventually, these deep waters reach the North Pacific, which hosts the oldest waters in the open ocean2 due to the absence of local deep convection3. The return of such deep waters to the surface results from diapycnal upwelling (across density surfaces) in the Pacific, which feeds upper ocean return flows to the North Atlantic Ocean1,4. Both diapycnal fluxes directly into the Pacific thermocline and isopycnal upwelling (along density surfaces) in the Southern Ocean contribute to that transport1,5. The Southern Ocean route is also important for returning old respired carbon to the surface ocean2,5. Together, these upwelling and return pathways balance the deep export of water from the Atlantic basin within the global overturning circulation system1,4,5. The return flows to the Atlantic Ocean typically follow two routes: the cold water route through the Drake Passage6 and the warm water route via the Indonesian Throughflow and the Agulhas Leakage south of Africa4.

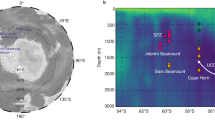

More recently, a third route has been recognized south of Tasmania, which is known as the Tasman Leakage and originates from the poleward transport of predominantly subsurface Pacific waters along the East Australian margin7,8,9,10,11,12 (Fig. 1a). The southward-flowing subsurface waters contain a local variant of Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW)9,10,12 that crossed the South Pacific Gyre after formation in the Southeast Pacific13. Most of the southward-flowing waters turn eastwards at the Tasman Front near ~35°S, but a proportion flows west around the Tasman margin towards the Indian Ocean10,11 (Fig. 1a). This outflow at intermediate depths is more saline than AAIW in the Southern Ocean10 and comprises both eddy transport and a non-eddy component11. The westward-flowing Tasman Leakage waters are bound to a narrow corridor due to bathymetric constraints and the frontal system of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), which dictates predominantly eastward transport of water masses to the south of Tasmania7,10,14 (Fig. 1a). From the Indian Ocean, the Tasman Leakage waters follow the warm water route via the Agulhas Leakage4,15,16 and may represent up to ~50 % of the upper ocean return flow to the North Atlantic17. Unlike the Indonesian Throughflow and Drake Passage routes, the intermediate waters of the Tasman Leakage can preserve their hydrographic properties during transit9,10, thus providing a distinct pathway for the transfer of climatic signals from the Pacific to the Indian and Atlantic oceans10.

a Map showing the coral sample locations south of Tasmania (red diamond) and locations of seawater Nd isotope profiles from stations SR3-60 (light gray triangle), TAN0803-41 (light gray circle), GeoB17019-1 (dark gray triangle), and GeoB17018-1 (dark gray circle)38,40. Solid white arrows indicate simplified flow paths of intermediate waters, while the dashed arrow indicates the Tasman Leakage, and dark blue arrows represent deep water flow11,13,76,94. The mean positions of the Subtropical Front (STF), Subantarctic Front (SAF), Antarctic Polar Front (APF), and Southern ACC front (SACC) are indicated by gray lines14. Colored squares indicate locations of important paleoceanographic records from sediment cores MD06-2986 (dark blue, 1477 m water depth), SO136-003GC (green, 944 m water depth)66, and MD97-2120 (black, 1210 m water depth)65. The white diamond indicates the location of core FR1/97 GC-12 (990 m water depth)85. b Oxygen concentration section95 (along the black line in a), highlighting the major subsurface water masses in the study area: Subantarctic Mode Water (SAMW), Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW), Upper Circumpolar Deep Water (UCDW), Lower Circumpolar Deep Water (LCDW), Pacific Deep Water (PDW), and Equatorial Pacific Intermediate Water (EqPIW) representing a mixture of AAIW originating from the Southeast Pacific and upwelled PDW13,38. Thin black lines indicate surfaces of neutral density anomalies γn (in kg/m3)96. Yellow triangles and red diamonds depict sampling depths of modern and fossil corals, respectively. Ocean fronts and locations of water column profiles (gray circles and triangles) as in a. Base map in a and oxygen section in b generated with ODV software97.

On daily to decadal timescales, the modern Tasman Leakage shows highly variable transport, which has been related to changes in wind forcing7,11,12,16. As such, the outflow can respond sensitively to short-term changes in external forcing, similar to other bottlenecks in the global overturning circulation system7,11,15,18. On multi-decadal to orbital timescales, changes in water flow through these various gateways have been proposed to play an important role in modulating the distribution of heat and salt between the ocean basins19,20,21,22. Moreover, the intensity of the shallow Pacific outflow via the Indonesian Seas has been directly linked to the overturning circulation strength in the Atlantic23 and to deep water inflow and upwelling rates in the Pacific basin24. These studies, therefore, indicate a potential mechanistic connection between the upper-ocean Pacific outflow dynamics and the deep branch of the global overturning circulation. Considering the role of Tasman Leakage waters in re-supplying the Atlantic overturning circulation today17, circulation changes at the Tasman margin may represent a critical component in the global overturning circulation system over glacial-interglacial timescales.

Previous research has focused on reconstructing Pleistocene changes in hydrography and transport through the Indonesian Seas25,26,27, the Agulhas Leakage19,28,29, and the Drake Passage22,30,31,32,33,34. The combined evidence from these studies suggests that the interoceanic exchange of water masses through the oceanic choke points was reduced during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM: 18–24 ka BP), yet the overturning circulation was more active in the Pacific Ocean at the LGM35. One possibility is that changes in the outflow south of Tasmania could have compensated for reductions in the strength of the Indonesian Throughflow, as suggested for centennial to millennial timescales12. However, it has proven challenging to test this idea for the glacial ocean, because tracing changes in the provenance of intermediate and deep water masses is difficult with traditional paleoceanographic tools in this highly dynamic region.

Here we use the neodymium (Nd) isotope composition of the aragonitic skeletons of cold-water corals collected from intermediate water depths south of Tasmania (Fig. 1) to test the idea that circulation changes in this region played a role in the interoceanic exchange of water masses during the last glacial period between ~68 and 12.7 ka BP. At a broad scale, the modern distribution of Nd isotopes in the deep ocean is dominated by mixing between unradiogenic North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) (εNd ~−13)36 and radiogenic Pacific-derived water masses (εNd ~−3 to −4)37,38. Mixing between these water masses in the ACC forms Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW), which has intermediate Nd isotope compositions (εNd ~−8)39,40. The Nd isotope composition of upwelling Upper CDW (UCDW) is largely preserved during the transformation to AAIW, and is similar in composition to Lower CDW (LCDW), which results in a relatively uniform vertical distribution of Nd isotopes in the modern Southern Ocean water column39,40,41,42 (Fig. 2a). However, this Southern Ocean Nd isotope homogeneity did not persist back in time33,34, indicating the potential of using this tracer to explore past changes in ocean circulation and structure. Specifically, a glacial Nd isotope record from south of Tasmania could reveal variability in Pacific water contributions to this region, subject to constraints on past Nd cycling and Nd isotope compositions in the Pacific Ocean. In turn, such evidence would enable a unique assessment of links between the outflow of Pacific waters via the Tasman Sea and large-scale glacial-interglacial ocean circulation changes.

a Coral Nd isotope data (symbols and error bars as in b) compared to modern seawater Nd isotope profiles from the Southern Ocean40 and West Pacific38 (symbols as in Fig. 1). Light and dark gray bars indicate the range of Nd isotope signatures (εNd) of water masses between 400 and 3000 m water depth in the Southern Ocean40 and in the West Pacific38, respectively. Also shown is a profile from North Pacific station BO-1 (gray squares; 40°N, 160°E)98. Error bars for seawater Nd isotope data represent the 2 s uncertainties reported in the original publications38,40,98. SAMW Subantarctic Mode Water, AAIW Antarctic Intermediate Water, UCDW Upper Circumpolar Deep water, LCDW Lower Circumpolar Deep Water, PDW Pacific Deep Water. b Time series of fossil coral εNd compared to Pb isotope (206Pb/204Pb) data from the same specimens50. Error bars represent the analytical uncertainties of coral Nd (Methods) and Pb isotope data50. A light gray bar outlines the 2 SD of Nd isotope compositions of CDW from the Indian Ocean and the Drake Passage between 10 and 70 ka BP34,57,59 (see Fig. 3b for more details). The dark gray bar represents the 2 SD of past seawater Nd isotope compositions from north of the Tasman Sea for the time interval between 10 and 30 ka BP71,72. The numbers and boundaries of Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) are shown along the top axis. Dotted lines and numbers indicate Heinrich Stadials. ACR Antarctic Cold Reversal, LGM Last Glacial Maximum. Ages are reported in thousand years before the present (ka BP, present = 1950). Modern coral data include one replicate (see Supplementary Data 1).

Results and discussion

Sample locations

For this study, we selected 62 fossils and three late Holocene (referred to as modern) cold-water coral specimens of Desmophyllum dianthus that were collected from south of Tasmania (~44°S and ~147°E) (Fig. 1a) using the remotely operated submergence vehicle JASON during cruise TN-228. The three modern corals43 provide a vertical transect from 951 to 2170 m water depth (Supplementary Data 1), sampling both AAIW and UCDW, which are approximately separated by the neutral density surface γn of 27.55 kg/m³ at ~1200 m water depth13 (Fig. 1b). The AAIW layer in the study area is occupied by different variants of AAIW, including northward-flowing Southern Ocean AAIW and southward-flowing Pacific AAIW, which is further modified along the East Australian margin by the incorporation of Tasman Sea thermocline waters to form Tasman Sea AAIW13 (Fig. 1). The fossil coral specimens were collected from a narrow range of 1460 to 1689 m water depth43,44, which in the modern ocean is occupied by UCDW and corresponds to a neutral density γn of 27.75 – 27.85 kg/m³ (refs. 7,40,.) (Fig. 1b). We recognize that the water mass structure and properties may have changed in the past, but use the nomenclature of the modern water masses to describe past oceanographic changes at the depth levels presently occupied by these water masses.

Significance of the Tasman coral Nd isotope signal

The modern corals range from relatively radiogenic εNd values of −6.6 ± 0.4 at 951 m water depth to less radiogenic εNd values of −8.3 and −8.7 ± 0.2 at ~1900 and ~2170 m depth, respectively (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Data 1). The fossil corals were collected from the narrow depth range of 1460 to 1689 m and covered the later part of the last glacial period from 67.5 to 12.7 ka BP44, revealing εNd variability between −4.6 ± 0.2 and −7.7 ± 0.2 (Fig. 2; Supplementary Data 1). The record is characterized by a long-term trend from εNd values of −7.5 ± 0.2 during early Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 3 towards maximum εNd values of −4.6 ± 0.2 during late MIS 2. Superimposed on the long-term evolution, the corals indicate abrupt centennial to millennial-scale Nd isotope shifts, with deviations of up to ~1.5 εNd units from the overall trend line (Fig. 2b). During the deglaciation, we observe a large shift from εNd = −4.9 ± 0.2 at 16.7 ka BP, within early Heinrich Stadial 1 (HS 1), to εNd = −7.3 ± 0.2 at 14.8 ka BP, around the end of HS 1. Those less radiogenic values characterize the Antarctic Cold Reversal (ACR) up to the youngest analyzed sample at 12.7 ka BP (Fig. 2b).

Rigorously cleaned skeletons of cold-water coral D. dianthus have been shown to reliably record ambient seawater Nd isotope signatures45,46. Here we add three modern corals from the Tasman continental margin to the existing calibration datasets. The Nd isotope compositions of the corals at ~1900 and ~2170 m water depth are in excellent agreement with the mean Southern Ocean seawater εNd value of −8.2 ± 0.9 for UCDW (2 SD, n = 41)40, and with the most proximal seawater data40 (Fig. 2a). The modern coral from intermediate water depths has an εNd value of −6.6 ± 0.4, which is more radiogenic than the nearby Southern Ocean AAIW εNd values of −8.1 ± 0.3 (2 SD, n = 3) measured on modern seawater40. This difference can be attributed to the mixing between northward-flowing AAIW derived from the Southern Ocean and southward-flowing intermediate waters, which deliver more radiogenic Nd from the West Pacific region (εNd ~−5)38 to the Tasman margin10,11,12,13 (Figs. 1, 2a). Overall, our data confirm that the skeletons of D. dianthus record ambient seawater Nd isotope compositions and indicate the value of Nd isotopes for tracing the presence of Pacific versus Southern Ocean water masses in the study area.

The Nd isotope composition of local seawater in the past could potentially have been modified by changes in particulate and/or solute fluxes from nearby land masses. While terrestrial input fluxes from the South Island of New Zealand into the eastern Tasman Sea were largely invariable during the last glacial-interglacial cycle47, changes in fluvial activity and dust emissions in Australia have been documented and represent a possible source of radiogenic Nd (εNd > ~−5) to the study area48,49. To evaluate possible changes in local Nd inputs in the past, it is informative to look at lead (Pb) isotopes in the same Tasman corals50. Due to its higher particle reactivity, dissolved Pb has a shorter residence time than Nd in seawater51, such that changes in local input fluxes and sediment-seawater interaction are expected to be more readily reflected in the authigenic seawater-derived Pb isotope composition of the Tasman corals50. Past seawater Pb isotope reconstructions from a subset of the corals spanning ~40 to 12 ka BP show no correspondence with our Nd isotope data (R² = 0.03; Fig. 2b)50, which argues against local processes as a major control on the reconstructed Nd isotope changes. Moreover, the modern seawater and coral Nd isotope datasets do not indicate a significant influence of boundary exchange in the study area40. This assertion is consistent with observations from other highly dynamic regions of the Southern Ocean, including the Drake Passage where UCDW is forced through a narrow channel of rocks and sediments with relatively radiogenic Nd isotope compositions46. The Drake Passage experienced pronounced glacial-interglacial changes in both ocean circulation and the local input of reactive lithogenic material, with no indication that boundary exchange controlled the Nd isotope composition of past seawater33,34. Consequently, there is no reason to expect that boundary exchange was more pronounced in the study area during the last glacial period, so our data are best explained by a primary control from changes in water mass sourcing on a regional to basin-scale (Fig. 2a).

Origin of the radiogenic Nd isotope signal

Neodymium isotope signatures of ~−5 during the late glacial interval (25.3–16.7 ka BP) are approximately three εNd units higher than modern seawater values at the coral sampling locations (Fig. 2b) and mark the culmination of a long-term evolution during MIS 3 and MIS 2 that corresponds to a global cooling trend (Fig. 3a, b). Building on our arguments above, we consider four possible scenarios to explain the highly radiogenic Nd isotope composition of late glacial seawater south of Tasmania: (i) changes in the composition of UCDW in the Southern Ocean, (ii) enhanced admixture of water masses from below, (iii) local deepening of a more radiogenic glacial version of AAIW, and (iv) enhanced advection of intermediate water masses from the West Pacific.

a WAIS Divide ice core oxygen isotope (δ18O) data (thin gray line) with a five-point running mean (thick black line)99. b Mid-depth cold-water coral Nd isotope (εNd) data from south of Tasmania (this study) compared to Drake passage Lower Circumpolar Deep Water (LCDW)34 and Upper Circumpolar Deep Water (UCDW)30 and Indian Ocean LCDW from core SK129-CR2 (light blue)57,59. Error bars and light blue shading represent the respective 2 SD uncertainties. c Abundance of subpolar species (light gray; five-point running mean in black) from core MD03-2611 as an indicator of changes in Southern Ocean front positions south of Australia21. d Tasmanian cold-water coral benthic-atmosphere (B-atm) radiocarbon age offsets and their propagated uncertainties (see also caption of Fig. 4) for fossil corals (black diamonds)44 and for the modern UCDW (black triangles) and AAIW corals (inverted black triangle)43 included in this study (Figs. 1b, 2a, b). e Benthic carbon isotope (δ13C) data from eastern Tasman Sea cores MD06-2986 (UCDW, 11-point running mean in dark blue) and SO136-003GC (AAIW: Antarctic intermediate water; 11-point running mean in green)66, compared to Southwest Pacific core MD97-2120 (light gray; 11-point running mean in black)65. Arrow indicates trends in AAIW depth, which is shallower than 1210 m when the MD97-2120 record converges with UCDW compositions. f Benthic δ13C data from northern Tasman Sea core FR1/97 GC-1285 (radiocarbon dates re-calibrated using CALIB 8.1 software100 and Marine20 calibration curve101) compared to a spliced record of North Pacific cores SO201-2-101KL and SO201-2-85KL84,86 (light gray; five-point running mean in purple), representing a North Pacific Intermediate Water (NPIW) source signal, and δ13C from sub-thermocline-dwelling foraminifera G. hexagonus in ODP 1240 (light gray; five-point running mean in brown), recording the composition of Equatorial Pacific Intermediate Water (EqPIW). The convergence of the latter two records has been interpreted as NPIW expansion into the Equatorial Pacific84. Heinrich Stadials are numbered and highlighted with gray bars along the top axis. LGM Last Glacial Maximum. ACR Antarctic Cold Reversal. The numbers and boundaries of Marine Isotope Stages 1–4 (MIS) are shown along the lower axis according to Fig. 2b.

In the modern ocean, the dominant water mass at the fossil coral sampling locations is UCDW (Figs. 1b, 2a), and a northward shift of the ACC frontal system in the Indo-Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean21,52 (Fig. 3c) could be expected to have reinforced the presence of UCDW at the sampling locations during the late glacial interval. While Nd isotope reconstructions for glacial UCDW have been attempted using foraminifera in sediment cores east of New Zealand53,54, the records from this area are compromised by an offset of ~1–2 εNd units between the measured Holocene signal53,54 and nearby modern seawater values42, which precludes a direct comparison to our coral-based record. In contrast, reconstructions from UCDW depths in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean show good agreement between late Holocene foraminifera values and modern seawater, and indicate late glacial εNd values of ~−7.5 for UCDW55. A more representative Southern Ocean UCDW signal is provided by Drake Passage cold-water corals, with a single specimen from UCDW depths recording an εNd value of −6.4 during HS 130. This UCDW value integrates the circumpolar flow after interaction with the radiogenic water masses of the Pacific, at a time when unradiogenic water masses from the North Atlantic exerted a reduced influence in the Southern Ocean30. However, a Nd isotope composition of ~−6.4 for UCDW in the Southern Ocean is not sufficiently radiogenic to explain late glacial εNd values of ~−5 recorded at the Tasman margin (Fig. 3b).

The late glacial Nd isotope composition of LCDW was more radiogenic than in the modern ocean, which could reflect a reduced presence of unradiogenic NADW in the glacial deep ocean34,56,57,58,59,60, changes in the composition of NADW61,62 and/or changes in the interaction with Pacific waters54,63. Upwelling along sloping isopycnals provides an efficient and direct route for LCDW to reach the upper water column of the Southern Ocean1,5 (Fig. 1b). Therefore, a northward shift of the ACC frontal system21,52 (Fig. 3c) could potentially have increased the exposure of the Tasman corals to LCDW during the late glacial interval (Fig. 1b). However, glacial LCDW was characterized by relatively unradiogenic εNd values of ~−6 to −8, as evidenced by reconstructions from the South Pacific60, the Drake Passage34, and the deep Indian Ocean57,59 (Fig. 3b). These values are too unradiogenic to drive concurrent εNd values south of Tasmania to ~−5. Importantly, an increased presence of LCDW at the coral sampling locations would require a northward shift of the ACC frontal system and the associated isopycnals by more than 10° latitude, which would push both the Subantarctic Front and the Antarctic Polar Front against the Tasman margin (Fig. 1b). Such a scenario is difficult to reconcile with the modern observation that the South Tasman Rise and Campbell Plateau force the deep-reaching fronts of the ACC into a circumpolar trajectory to the south of the coral sampling locations14 (Fig. 1a). Moreover, LCDW was characterized by a low radiocarbon content at the LGM, with a B-atm offset (i.e. the offset between marine benthic and atmospheric 14C ages64) of ~3000 years, whereas concurrent B-atm values at the Tasman margin fluctuated around ~1200 years44 (Fig. 3d). Thus, we exclude the exposure to LCDW as a primary control on the Nd isotope evolution recorded by the cold-water corals.

If glacial AAIW in the Southern Ocean had a significantly more radiogenic Nd isotope composition than today, local deepening of the AAIW layer could provide a possible explanation for the radiogenic Nd isotope signatures at the coral sampling locations (Fig. 1b). A deepening of Southern Ocean AAIW to reach the coral sampling depths would be consistent with the relatively well-ventilated signal reconstructed from radiocarbon44 (Fig. 3d). However, AAIW is formed from UCDW, which was significantly less radiogenic (εNd ~−7)30,55 than our coral data (εNd ~−5) during the late glacial interval (Fig. 4). Recent work from the Drake Passage shows that the Nd isotope signal of UCDW is generally preserved during water mass transformation in the Southern Ocean upper overturning cell33. Moreover, based on modern seawater data it can be expected that any local influences would drive the surface waters between Australia and Antarctica to even less radiogenic values than the upwelling UCDW εNd signal40. Therefore, a deep variant of AAIW forming in the Southern Ocean south of Australia would be unable to explain the shift to such radiogenic Nd isotope signatures at the coral sampling locations during the last glacial period. In addition, rather than a glacial deepening, independent evidence from stable oxygen and carbon isotopes and from redox-sensitive proxies (rhenium and uranium) suggests a glacial shoaling of Southern Ocean AAIW in the study area65,66,67 (Fig. 3e).

The benthic-atmosphere radiocarbon (14C) age offsets (B-atm) were calculated using an atmospheric 14C age of 0 years (1950 AD) for the modern seawater values2,102. For past B-atm, we used coral 14C ages44 and IntCal20 atmospheric 14C ages102. Atmospheric 14C values were calculated as averages of the reported 1 s coral calendar age uncertainty range44. Error bars represent 1 s propagated uncertainties for B-atm age offsets and 2 SD uncertainties for εNd. Modern water column data comprise regional Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW), Upper Circumpolar Deep Water (UCDW), and Lower Circumpolar Deep Water (LCDW) properties2,40. Hypothetical mixing calculations (dotted lines) use the following endmembers: modern North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW, εNd = −13.2, [Nd] = 17.6 pmol/kg, B-atm = 500 years, DIC [dissolved inorganic carbon] = 2160 μmol/kg)2,36; modern Pacific Deep Water (PDW, εNd = −3.5, [Nd] = 44.4 pmol/kg, B-atm = 2100 years, DIC = 2350 μmol/kg)2,37. Note that these hypothetical mixing lines do not account for non-conservative processes along the water mass flow paths. Glacial PDW was defined using an LGM B-atm age offset of 3000 years64 and otherwise modern PDW parameters due to the similarity of glacial and modern PDW Nd isotope compositions54,71,72. Glacial UCDW was estimated based on the Drake Passage coral Nd isotope30,34 and radiocarbon data31,69,103. Glacial North Pacific Intermediate Water (NPIW) properties at its source are estimated based on modern Nd isotope compositions37,38 and LGM radiocarbon ages35. A dashed gray arrow indicates mixing between glacial UCDW and glacial NPIW. Local ventilation (e.g., via deepening of Southern Ocean AAIW) would lead to lower B-atm and relatively invariant εNd values (black arrow). Where paired radiocarbon–Nd isotope data were not available from the same coral specimen, we matched the Nd isotope data with radiocarbon data from nearby corals of the same age (i.e., within age uncertainty and with <100 m depth difference).

A more radiogenic variant of AAIW is present in the modern West Pacific38 (Fig. 2a). This variant is mainly supplied by AAIW formation in the Southeast Pacific and modified to Tasman AAIW upon entering the Tasman Sea from the north13,67 (Fig. 1a). A recent study proposed an increased presence of Tasman AAIW over the Challenger Plateau in the eastern Tasman Sea (west of New Zealand) during the LGM67. Nevertheless, previous work from the main AAIW formation region in the Southeast Pacific68,69, as well as in areas influenced by Tasman AAIW (i.e., eastern Tasman Sea and Bay of Plenty)66,67,70 (Fig. 1a), are inconsistent with a deepening of Tasman AAIW to reach water depths of ~1500–1700 m during the LGM.

Consequently, the highly radiogenic Nd isotope signatures observed in late glacial corals from south of Tasmania were probably not the result of changes in the composition and/or depth ranges occupied by LCDW, UCDW, or AAIW. Instead, we consider the advection of radiogenic water masses from the Pacific Ocean north of the Tasman Sea to provide the most likely explanation (Fig. 1b). Importantly, this scenario requires a shift in the glacial circulation compared to the modern-day.

North Pacific water mass signals at the Tasman margin during the last glacial period

The circulation between the Tasman Sea and the West Pacific is restricted by complex bathymetric features (Fig. 1a), which confine the exchange of waters below ~1500 m water depth to narrow deep channels. The density range of the waters bathing our fossil coral sampling locations is currently occupied by UCDW and PDW, which share similar εNd values of ~−3 to −4 in the modern West Pacific38 (Figs. 1, 2a). Reconstructed glacial εNd values of ~−2.5 to −4 for mid-depth waters (~2–2.6 km water depth) in the West Pacific from north of the Tasman Sea71,72 are indistinguishable from those modern values (Fig. 2b). However, while the radiogenic Nd isotope compositions of the Tasman corals approached PDW values during the late glacial interval (εNd = −2 to −4)54,71, they were associated with much younger ventilation ages (Fig. 4). At the LGM, PDW was characterized by a pronounced radiocarbon depletion (B-atm ~3000 years)64, while the coral data from the Tasman margin show B-atm values of ~1200 years44 (Fig. 3d). Therefore, an increased presence of PDW is unsuitable to explain the trend towards more radiogenic Nd isotope compositions at the Tasman margin during the last glacial period (Fig. 4). The combined radiocarbon and Nd isotope evidence suggest that our LGM and early deglacial coral data lie on a mixing trend between an unradiogenic and poorly-ventilated source represented by glacial Southern Ocean UCDW and relatively well-ventilated and radiogenic Pacific-derived waters (Fig. 4). We hypothesize that this Pacific-derived outflow signal was driven by an expansion of North Pacific Intermediate Water (NPIW) during the last glacial period.

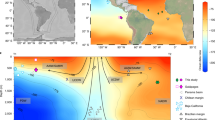

In the modern ocean, NPIW is characterized by εNd values of ~−337,38, but is confined to the North Pacific73,74 (Fig. 5a) as it leaves the Pacific through the Indonesian Seas74 above the sill depth of ~1300 m18,75,76. Its incorporation into the deep Tasman outflow during the last glacial period would thus require a mechanism that enables the cross-equatorial flow of NPIW (Fig. 5c). Modeling studies indicate that the formation of intermediate water masses in the North Pacific and/or their expansion across the Pacific basin may be sensitive to the strength of the Indonesian Throughflow77,78. Glacio-eustatic sea-level fall, the associated shelf exposure in the Indonesian Seas, and changes in the coupled ocean-atmosphere system of the tropical Indo-Pacific probably led to a reduction in the Indonesian Throughflow during glacial periods25,27 (Fig. 5c). An additional reduction of the Indonesian Throughflow may have arisen from a possible link with the weakened overturning circulation in the Atlantic Ocean under glacial boundary conditions23.

Cross-sections show the Pacific Ocean circulation for a the modern-day and c the LGM. Maps focus on the intermediate-depth circulation in the study area near Tasmania for b the present-day (see also Fig. 1a) and d the LGM. Base maps in b, d produced with ODV software97. Water mass pathways are indicated by arrows: Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW, black) and North Pacific Intermediate Water (NPIW, purple). SO: Southern Ocean. Note that the eastward flow of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) (circled dots in a and c) comprises also Upper Circumpolar Deep Water (UCDW) and Lower Circumpolar Deep Water (LCDW) (see also Fig. 1b for more details). Note also that the two possible pathways of glacial Tasman outflow waters are indicated by stippled lines in c, d and that the purple arrows in c, d do not represent pure NPIW, since it is influenced by the admixture of other ambient water masses during its southwards transport (see main text). Gray arrows in a, c indicate the deep overturning, where upwelling of LCDW and Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) feeds into the southward return flow of Pacific Deep Water (PDW). Flow strengths are schematically represented by the thickness of arrows (meridional flows) or the size of the circled dots/crosses (zonal flows). The solid black line in a represents the intermediate water layer ventilated primarily by AAIW and NPIW in the modern Pacific Ocean, while the stippled black line in c indicates the deepened LGM analogue. Dashed boxes indicate the locations and approximate depth extents of Pacific outflow along the Tasman margin and through the Indonesian Seas. The position of the Southern Westerly Winds (SWW) is also shown with circled dots.

Consistent with those modelling predictions77,78, proxy evidence points to the existence of a chemical divide at about 2000 m water depth in the Pacific Ocean at the LGM, with the upper part of the water column dominated by relatively well-ventilated waters35,79,80. This ventilated state has been attributed to a deepening and intensification of NPIW formation35,79,80,81, which was presumably related to subpolar gyre dynamics and reduced freshwater fluxes to the North Pacific35,82. The expanded glacial NPIW signal was detected in reconstructions from the equatorial Pacific83,84 (Fig. 3f) and has been proposed to have spread towards the Southern Ocean predominantly along the western boundary of the Pacific35. A record of benthic carbon isotopes from 990 m water depth on the east Australian margin (northern Tasman Sea) (Fig. 1a) reveals values that were originally interpreted to result from changes in mixing between AAIW and UCDW85. However, glacial NPIW and glacial UCDW are characterized by rather similar δ13C66,84 (Fig. 3e, f). Thus, the northern Tasman Sea record may also be explained by an increased influence of southward-flowing glacial NPIW (low δ13C)84,86 alternating with shallower AAIW (higher δ13C)66,70,85 at these depths during the last glacial period (Fig. 3f). Notably, the peak in NPIW formation during HS 120,86,87 coincides with the most radiogenic Nd isotope compositions and improved ventilation recorded south of Tasmania (Fig. 3b, d). Hence, we propose that the long-term glacial trend towards more radiogenic Nd isotope compositions south of Tasmania was linked to the expansion of glacial NPIW and its incorporation into an outflow through the Tasman Sea below the depth range of modern Tasman Leakage waters. If this interpretation is correct, our data provide evidence that glacial NPIW reached the extratropical South Pacific.

Glacial reorganization of Pacific Ocean circulation and inter-ocean exchange

It has previously been speculated that a reduction in the Indonesian Throughflow could be compensated, on centennial to millennial timescales, by enhanced export of Pacific water masses via the Tasman Sea12. Our coral data corroborate this idea and provide evidence that a glacial reorganization of ocean circulation in the Pacific could have involved the export of NPIW via the Tasman Sea (Fig. 5c, d). Such export would have been particularly efficient during times when NPIW deepened below the Indonesian Throughflow sill depth of ~1300 m75 (Fig. 5c). A reduced inflow of Southern Ocean AAIW into the intermediate depths of the Pacific Ocean (Fig. 5c, d), linked to a shoaling66 and/or weakening65 of Southern Ocean AAIW formation during the LGM, could have further supported the southwards expansion of NPIW within the Pacific basin77. We emphasize that the glacial outflow described here was found at depths significantly below the modern Tasman Leakage waters (Fig. 5a, c). Taken in combination with the possible lower boundary of Tasman AAIW near ~1000 m water depth67,85, our coral dataset suggests that the deep outflow extended from ~1000 to at least ~1700 m water depth during the last glacial interval. At these depths, the southwards expanding glacial NPIW was probably subject to an admixture of other water masses in the West Pacific, potentially including glacial PDW, UCDW, and different variants of AAIW (Figs. 1b, 5c, d). It is difficult to diagnose their individual contributions to the deep outflow signal at the Tasman margin from our dataset because these water masses have similar Nd isotope compositions in the modern Pacific Ocean, reflecting the non-conservative effects of local Nd inputs on the Nd isotope composition of seawater38. However, relatively invariant glacial-interglacial εNd values of ~−2.5 to −4 reconstructed from sites north of the Tasman Sea54,71,72 (Fig. 2b) suggest that any changes in advection, boundary exchange, benthic flux, weathering inputs, or open ocean particle-seawater interactions appear to have had a minimal effect on mid-depth West Pacific Nd isotope signatures across this interval38,47,63,71,72. Accordingly, a glacial intermediate water mass entering the Tasman Sea from the north would probably have been characterized by εNd values near or above ~−4, making it suitable to drive the trend towards more radiogenic glacial εNd values at the Tasman margin.

The key finding from our work is that these radiogenic Pacific-derived water masses contributed substantially to an outflow from the Tasman Sea at water depths of ~1500–1700 m during the last glacial period. This scenario is different from the modern situation, in which the outflow is concentrated in the Tasman Leakage at depths shallower than ~1200 m10,12,16. We ascribe this deep Tasman outflow to a glacial mode of more active NPIW formation35,81,84 (Fig. 5c, d), which has been proposed to have promoted the carbon storage in the deep ocean thus contributing to the glacial reduction of atmospheric CO235.

The deep Tasman outflow waters could have taken two possible routes after passing the coral sampling locations, with distinct implications for the glacial overturning circulation system. If the outflow waters followed the trajectory of the modern shallower Tasman Leakage waters into the Indian and Atlantic Oceans17 (Fig. 5a–d), they would have helped to maintain the interoceanic exchange of water masses and provided an oceanic pathway for the westward export of Pacific climate signals10,16. Conversely, parts of the deep Tasman outflow waters may have joined the eastward flow of the ACC (Fig. 5c, b, d), thus propagating climate signals into the Southern Ocean and influencing the nutrient availability in the Southern Ocean upon upwelling to the surface35. Considering the enhanced northwards deflection of circumpolar water masses in the Southeast Pacific during the late glacial interval22,32, such eastward-flowing waters would have contributed to a more isolated upper overturning cell in the Pacific Ocean78,80 rather than enhancing interoceanic exchange at that time.

While our coral data are unable to provide constraints on the relative importance of these two possible routes downstream of Tasmania, the most radiogenic εNd values in our record suggest that the outflow of Pacific waters was most pronounced during HS 1 (Fig. 3b) when changes in atmospheric circulation and salinity feedbacks promoted convective activity in the North Pacific20,78,87, and when a poleward shift of Southern Ocean winds and fronts21,52 (Fig. 3c) may have effectively widened the westward passageway for outflow waters at the Tasman margin7. Accordingly, such frontal shifts may also have been responsible for the rapid Nd isotope changes on centennial to millennial timescales during MIS 2. Albeit the most radiogenic Nd isotope compositions recorded by the Tasman corals coincided with HS 1, radiogenic Nd isotope excursions could also be a sign of enhanced Pacific outflow during previous Heinrich stadials (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, our coral data clearly indicate that the structure of the Pacific Ocean was substantially reorganized at the end of HS 1. At that time, convection in the North Pacific decreased20,86 and the expansion of NADW supported more modern-like water column characteristics in the Southern Ocean34,56,60, leading to Nd isotope compositions approaching modern values south of Tasmania (Fig. 3b).

Overall, our study provides evidence that a Pacific outflow through the Tasman Sea played a dynamic role in the interoceanic exchange of water masses within the global overturning circulation system through glacial-interglacial cycles. We demonstrate a close link between changes in the deep Tasman outflow, NPIW formation, and circulation changes in the Pacific Ocean during the last glacial period. Implementing these findings into refined ocean models will improve our understanding of how the outflow of Pacific waters via the Tasman Sea affects the interoceanic exchange of climate signals, the global overturning circulation strength, and the oceanic carbon storage, over a range of timescales in the past and the future.

Methods

Sample preparation and analytical procedures

Neodymium isotope analyses were carried out in the MAGIC laboratories at Imperial College London following established protocols46,88. In brief, physically and chemically cleaned cold-water coral samples were subjected to iron co-precipitation to concentrate trace metals before separating uranium (U) and thorium (Th) for U-series dating44. The Nd fractions of the fossil corals were collected during U-Th separation, whereas the Nd fractions of the three modern corals were collected from the wash fraction during Pb separation50. All Nd fractions were purified using a two-step ion-exchange chromatography protocol for analysis by thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS) as NdO+ 88.

Long-term TIMS results of 5 and 15 ng loads of JNdi-1 yielded 143Nd/144Nd = 0.512105 ± 0.000009 (2 SD, n = 110). For each analytical session, the instrumental offset was corrected by normalizing the mass-bias corrected 143Nd/144Nd ratios of samples based on the JNdi-1 reference ratio of 143Nd/144Nd = 0.512115 ± 0.00000746,89. The mass-bias corrected 143Nd/144Nd ratios from one analytical session were subjected to a secondary correction using 142Nd/144Nd90 (see also Supplementary Data 1), yielding 143Nd/144Nd = 0.512117 ± 0.000012 (2 SD, n = 5) for JNdi-1. The long-term external reproducibility was monitored with repeat analyses of USGS reference material BCR-2 and our in-house coral reference material during all analytical sessions, yielding 143Nd/144Nd of 0.512637 ± 0.000010 (2 SD, n = 34) and 0.512336 ± 0.000011 (2 SD, n = 25), respectively. These results are in excellent agreement with published results for BCR-2 (0.512637 ± 0.000012)91 and our coral reference material (0.512338 ± 0.000008)92. We report the 2 SD of the coral reference material as the analytical uncertainty for samples unless the internal 2SE is larger in which case the propagated error is reported. Full procedural blanks for combined U-Th/Pb and Nd separation from the aragonitic matrix ranged from 5 to 31 pg Nd, with a mean of 20 pg (n = 12). All Nd isotope results are reported as εNd = ((143Nd/144Ndsample)/(143Nd/144NdCHUR) – 1) × 10,000, where CHUR is the chondritic uniform reservoir93.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file and available in the figshare database under https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19355633.

References

Talley, L. D. Closure of the global overturning circulation through the Indian, Pacific, and Southern Oceans: Schematics and transports. Oceanography 26, 80–97 (2013).

Key, R. M. et al. A global ocean carbon climatology: results from global data analysis project (GLODAP). Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 18, GB4031 (2004).

Warren, B. A. Why is no deep water formed in the North Pacific? J. Mar. Res. 41, 327–347 (1983).

Gordon, A. L. Interocean exchange of thermocline water. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 91, 5037–5046 (1986).

Marshall, J. & Speer, K. Closure of the meridional overturning circulation through Southern Ocean upwelling. Nat. Geosci. 5, 171–180 (2012).

Rintoul, S. R. South Atlantic interbasin exchange. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 96, 2675–2692 (1991).

Rintoul, S. R. & Sokolov, S. Baroclinic transport variability of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current south of Australia (WOCE repeat section SR3). J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 106, 2815–2832 (2001).

Speich, S., Blanke, B. & Madec, G. Warm and cold water routes of an O.G.C.M. thermohaline conveyor belt. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 311–314 (2001).

Speich, S. et al. Tasman leakage: a new route in the global ocean conveyor belt. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 55-1–55–4 (2002).

Ridgway, K. R. & Dunn, J. R. Observational evidence for a Southern Hemisphere oceanic supergyre. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L13612 (2007).

van Sebille, E., England, M. H., Zika, J. D. & Sloyan, B. M. Tasman leakage in a fine-resolution ocean model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L06601 (2012).

van Sebille, E. et al. Pacific-to-Indian Ocean connectivity: Tasman leakage, Indonesian throughflow, and the role of ENSO. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 119, 1365–1382 (2014).

Bostock, H. C., Sutton, P. J., Williams, M. J. M. & Opdyke, B. N. Reviewing the circulation and mixing of Antarctic intermediate water in the South Pacific using evidence from geochemical tracers and Argo float trajectories. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 73, 84–98 (2013).

Orsi, A. H., Whitworth, T. & Nowlin, W. D. On the meridional extent and fronts of the Antarctic circumpolar current. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 42, 641–673 (1995).

Biastoch, A., Boning, C. W., Schwarzkopf, F. U. & Lutjeharms, J. R. E. Increase in Agulhas leakage due to poleward shift of southern hemisphere westerlies. Nature 462, 495–498 (2009).

Qu, T., Fukumori, I. & Fine, R. A. Spin-up of the southern hemisphere super gyre. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 154–170 (2019).

Rousselet, L., Cessi, P. & Forget, G. Routes of the upper branch of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation according to an Ocean state estimate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089137 (2020).

Sprintall, J. et al. The Indonesian seas and their role in the coupled ocean–climate system. Nat. Geosci. 7, 487–492 (2014).

Bard, E. & Rickaby, R. E. M. Migration of the subtropical front as a modulator of glacial climate. Nature 460, 380–383 (2009).

Okazaki, Y. et al. Deepwater formation in the North Pacific during the last glacial termination. Science 329, 200–204 (2010).

De Deckker, P., Moros, M., Perner, K. & Jansen, E. Influence of the tropics and southern westerlies on glacial interhemispheric asymmetry. Nat. Geosci. 5, 266–269 (2012).

Lamy, F. et al. Glacial reduction and millennial-scale variations in Drake Passage throughflow. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 13496–13501 (2015).

Sun, S. & Thompson, A. F. Centennial changes in the Indonesian throughflow connected to the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation: the ocean’s transient conveyor belt. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090615 (2020).

Feng, M., Zhang, X., Sloyan, B. & Chamberlain, M. Contribution of the deep ocean to the centennial changes of the Indonesian Throughflow. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 2859–2867 (2017).

Holbourn, A. et al. Orbitally paced paleoproductivity variations in the Timor Sea and Indonesian Throughflow variability during the last 460 kyr. Paleoceanography 20, PA3002 (2005).

Stumpf, R. et al. Persistently strong Indonesian Throughflow during marine isotope stage 3: evidence from radiogenic isotopes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 112, 197–206 (2015).

Petrick, B. et al. Glacial Indonesian Throughflow weakening across the mid-Pleistocene climatic transition. Sci. Rep. 9, 16995 (2019).

Franzese, A. M., Hemming, S. R., Goldstein, S. L. & Anderson, R. F. Reduced Agulhas Leakage during the Last Glacial Maximum inferred from an integrated provenance and flux study. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 250, 72–88 (2006).

Martínez-Méndez, G. et al. Contrasting multiproxy reconstructions of surface ocean hydrography in the Agulhas Corridor and implications for the Agulhas Leakage during the last 345,000 years. Paleoceanography 25, PA4227 (2010).

Robinson, L. F. & van de Flierdt, T. Southern Ocean evidence for reduced export of North Atlantic Deep Water during Heinrich event 1. Geology 37, 195–198 (2009).

Burke, A. & Robinson, L. F. The Southern Ocean’s role in carbon exchange during the last deglaciation. Science 335, 557–561 (2012).

Roberts, J. et al. Deglacial changes in flow and frontal structure through the Drake Passage. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 474, 397–408 (2017).

Struve, T., Wilson, D. J., Flierdt, T., van de, Pratt, N. & Crocket, K. C. Middle Holocene expansion of Pacific Deep Water into the Southern Ocean. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 889–894 (2020).

Wilson, D. J. et al. Sea-ice control on deglacial lower cell circulation changes recorded by Drake Passage deep-sea corals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 544, 116405 (2020).

Rae, J. W. B. et al. Overturning circulation, nutrient limitation, and warming in the Glacial North Pacific. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd1654 (2020).

Lambelet, M. et al. Neodymium isotopic composition and concentration in the western North Atlantic Ocean: results from the GEOTRACES GA02 section. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 177, 1–29 (2016).

Fröllje, H. et al. Hawaiian imprint on dissolved Nd and Ra isotopes and rare earth elements in the central North Pacific: Local survey and seasonal variability. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 189, 110–131 (2016).

Behrens, M. K., Pahnke, K., Schnetger, B. & Brumsack, H.-J. Sources and processes affecting the distribution of dissolved Nd isotopes and concentrations in the West Pacific. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 222, 508–534 (2018).

Stichel, T., Frank, M., Rickli, J. & Haley, B. A. The hafnium and neodymium isotope composition of seawater in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 317–318, 282–294 (2012).

Lambelet, M. et al. The neodymium isotope fingerprint of Adélie Coast bottom water. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 11,247–11,256 (2018).

Carter, P., Vance, D., Hillenbrand, C. D., Smith, J. A. & Shoosmith, D. R. The neodymium isotopic composition of waters masses in the eastern Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 79, 41–59 (2012).

Basak, C., Pahnke, K., Frank, M., Lamy, F. & Gersonde, R. Neodymium isotopic characterization of Ross Sea Bottom Water and its advection through the southern South Pacific. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 419, 211–221 (2015).

Thiagarajan, N. et al. Movement of deep-sea coral populations on climatic timescales. Paleoceanography 28, 227–236 (2013).

Hines, S. K. V., Southon, J. R. & Adkins, J. F. A high-resolution record of Southern Ocean intermediate water radiocarbon over the past 30,000 years. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 432, 46–58 (2015).

van de Flierdt, T., Robinson, L. F. & Adkins, J. F. Deep-sea coral aragonite as a recorder for the neodymium isotopic composition of seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 6014–6032 (2010).

Struve, T. et al. Neodymium isotopes and concentrations in aragonitic scleractinian cold-water coral skeletons - Modern calibration and evaluation of palaeo-applications. Chem. Geol. 453, 146–168 (2017).

Cogez, A. et al. Constraints on the role of tectonic and climate on erosion revealed by two time series analysis of marine cores around New Zealand. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 410, 174–185 (2015).

Bayon, G. et al. Extensive wet episodes in Late Glacial Australia resulting from high-latitude forcings. Sci. Rep. 7, 44054 (2017).

De Deckker, P. Airborne dust traffic from Australia in modern and Late Quaternary times. Glob. Planet. Change 184, 103056 (2020).

Wilson, D. J., van de Flierdt, T. & Adkins, J. F. Lead isotopes in deep-sea coral skeletons: Ground-truthing and a first deglacial Southern Ocean record. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 204, 350–374 (2017).

Henderson, G. M. & Maier-Reimer, E. Advection and removal of 210Pb and stable Pb isotopes in the oceans: a general circulation model study. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 66, 257–272 (2002).

Anderson, R. F. et al. Wind-driven upwelling in the southern ocean and the deglacial rise in atmospheric CO2. Science 323, 1443–1448 (2009).

Noble, T. L., Piotrowski, A. M. & McCave, I. N. Neodymium isotopic composition of intermediate and deep waters in the glacial southwest Pacific. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 384, 27–36 (2013).

Hu, R. & Piotrowski, A. M. Neodymium isotope evidence for glacial-interglacial variability of deepwater transit time in the Pacific Ocean. Nat. Commun. 9, 4709 (2018).

Hu, R. et al. Neodymium isotopic evidence for linked changes in Southeast Atlantic and Southwest Pacific circulation over the last 200 kyr. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 455, 106–114 (2016).

Piotrowski, A. M., Goldstein, S. L., Hemming, S. R. & Fairbanks, R. G. Temporal relationships of carbon cycling and ocean circulation at glacial boundaries. Science 307, 1933–1938 (2005).

Piotrowski, A. M. et al. Indian Ocean circulation and productivity during the last glacial cycle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 285, 179–189 (2009).

Skinner, L. C. et al. North Atlantic versus Southern Ocean contributions to a deglacial surge in deep ocean ventilation. Geology 41, 667–670 (2013).

Wilson, D. J., Piotrowski, A. M., Galy, A. & Banakar, V. K. Interhemispheric controls on deep ocean circulation and carbon chemistry during the last two glacial cycles. Paleoceanography 30, 621–641 (2015).

Basak, C. et al. Breakup of last glacial deep stratification in the South Pacific. Science 359, 900–904 (2018).

Howe, J. N. W. et al. North Atlantic deep water production during the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat. Commun. 7, 11765 (2016).

Zhao, N. et al. Glacial–interglacial Nd isotope variability of North Atlantic deep water modulated by North American ice sheet. Nat. Commun. 10, 5773 (2019).

Du, J., Haley, B. A., Mix, A. C., Walczak, M. H. & Praetorius, S. K. Flushing of the deep Pacific Ocean and the deglacial rise of atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Nat. Geosci. 11, 749–755 (2018).

Skinner, L. C. et al. Radiocarbon constraints on the glacial ocean circulation and its impact on atmospheric CO2. Nat. Commun. 8, 16010 (2017).

Pahnke, K. & Zahn, R. Southern hemisphere water mass conversion linked with North Atlantic climate variability. Science 307, 1741–1746 (2005).

Ronge, T. A. et al. Pushing the boundaries: glacial/interglacial variability of intermediate and deep waters in the southwest Pacific over the last 350,000 years. Paleoceanography 30, 2014PA002727 (2015).

Durand, A. et al. Reduced oxygenation at intermediate depths of the southwest Pacific during the last glacial maximum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 491, 48–57 (2018).

Martínez Fontaine, C. et al. Ventilation of the deep ocean carbon reservoir during the last deglaciation: results from the Southeast Pacific. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 34, 2080–2097 (2019).

Li, T. et al. Rapid shifts in circulation and biogeochemistry of the Southern Ocean during deglacial carbon cycle events. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb3807 (2020).

Sikes, E. L., Elmore, A. C., Allen, K. A., Cook, M. S. & Guilderson, T. P. Glacial water mass structure and rapid δ18O and δ13C changes during the last glacial termination in the Southwest Pacific. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 456, 87–97 (2016).

Hu, R., Piotrowski, A. M., Bostock, H. C., Crowhurst, S. & Rennie, V. Variability of neodymium isotopes associated with planktonic foraminifera in the Pacific Ocean during the Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 447, 130–138 (2016).

Wu, Q. et al. Foraminiferal εNd in the deep north-western subtropical Pacific Ocean: Tracing changes in weathering input over the last 30,000 years. Chem. Geol. 470, 55–66 (2017).

Talley, L. D. Distribution and formation of North Pacific intermediate water. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 23, 517–537 (1993).

Bingham, F. M. & Lukas, R. The southward intrusion of North Pacific intermediate water along the Mindanao Coast. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 24, 141–154 (1994).

Gordon, A. L., Giulivi, C. F. & Ilahude, A. G. Deep topographic barriers within the Indonesian seas. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 50, 2205–2228 (2003).

Sprintall, J., Wijffels, S. E., Molcard, R. & Jaya, I. Direct estimates of the Indonesian Throughflow entering the Indian Ocean: 2004–2006. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 114, (2009).

McCreary, J. P. & Lu, P. Influence of the Indonesian Throughflow on the circulation of Pacific intermediate water. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 31, 932–942 (2001).

Saenko, O. A., Schmittner, A. & Weaver, A. J. The Atlantic–Pacific seesaw. J. Clim. 17, 2033–2038 (2004).

Keigwin, L. D. Glacial-age hydrography of the far northwest Pacific Ocean. Paleoceanography 13, 323–339 (1998).

Matsumoto, K., Oba, T., Lynch-Stieglitz, J. & Yamamoto, H. Interior hydrography and circulation of the glacial Pacific Ocean. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 1693–1704 (2002).

Knudson, K. P. & Ravelo, A. C. North Pacific intermediate water circulation enhanced by the closure of the Bering Strait. Paleoceanography 30, 1287–1304 (2015).

Gray, W. R. et al. Wind-driven evolution of the North Pacific subpolar gyre over the last deglaciation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086328 (2020).

Leduc, G., Vidal, L., Tachikawa, K. & Bard, E. Changes in Eastern Pacific ocean ventilation at intermediate depth over the last 150kyrBP. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 298, 217–228 (2010).

Max, L. et al. Evidence for enhanced convection of North Pacific intermediate water to the low-latitude Pacific under glacial conditions. Paleoceanography 32, 41–55 (2017).

Bostock, H. C., Opdyke, B. N., Gagan, M. K. & Fifield, L. K. Carbon isotope evidence for changes in Antarctic intermediate water circulation and ocean ventilation in the southwest Pacific during the last deglaciation. Paleoceanography 19, PA4013 (2004).

Max, L. et al. Pulses of enhanced North Pacific intermediate water ventilation from the Okhotsk Sea and Bering Sea during the last deglaciation. Clim 10, 591–605 (2014).

Gong, X. et al. Enhanced North Pacific deep-ocean stratification by stronger intermediate water formation during Heinrich Stadial 1. Nat. Commun. 10, 656 (2019).

Struve, T. et al. Neodymium isotope analyses after combined extraction of actinide and lanthanide elements from seawater and deep-sea coral aragonite. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 17, 232–240 (2016).

Tanaka, T. et al. JNdi-1: a neodymium isotopic reference in consistency with LaJolla neodymium. Chem. Geol. 168, 279–281 (2000).

Vance, D. & Thirlwall, M. An assessment of mass discrimination in MC-ICPMS using Nd isotopes. Chem. Geol. 185, 227–240 (2002).

Weis, D. et al. High-precision isotopic characterization of USGS reference materials by TIMS and MC-ICP-MS. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7, (2006).

Crocket, K. C., Lambelet, M., van de Flierdt, T., Rehkämper, M. & Robinson, L. F. Measurement of fossil deep-sea coral Nd isotopic compositions and concentrations by TIMS as NdO + , with evaluation of cleaning protocols. Chem. Geol. 374–375, 128–140 (2014).

Jacobsen, S. B. & Wasserburg, G. J. Sm-Nd isotopic evolution of chondrites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 50, 139–155 (1980).

Reid, J. L. On the total geostrophic circulation of the pacific ocean: flow patterns, tracers, and transports. Prog. Oceanogr. 39, 263–352 (1997).

Garcia, H. E. et al. World Ocean Atlas 2013. Volume 3: Dissolved Oxygen, Apparent Oxygen Utilization, and Oxygen Saturation. (NOAA Atlas NESDIS, 2014)

Jackett, D. R. & McDougall, T. J. A neutral density variable for the world’s oceans. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 27, 237–263 (1997).

Schlitzer, R. Ocean data view https://odv.awi.de (2020).

Amakawa, H. et al. Neodymium isotopic variations in Northwest Pacific waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 715–727 (2004).

WAIS Divide Project Members. Precise interpolar phasing of abrupt climate change during the last ice age. Nature 520, 661–665 (2015).

Stuiver, M., Reimer, P. J., & Reimer, R. W. CALIB 8.2. http://calib.org (2022).

Heaton, T. J. et al. Marine20—The marine radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55,000 cal BP). Radiocarbon 62, 779–820 (2020).

Reimer, P. J. et al. The IntCal20 northern hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725–757 (2020).

Chen, T. et al. Synchronous centennial abrupt events in the ocean and atmosphere during the last deglaciation. Science 349, 1537 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the science teams and crews of expedition TN-228. K. Kreissig and B. Coles are thanked for their help with laboratory analyses. The authors acknowledge financial support from the Grantham Institute of Climate Change and the Environment (T.v.d.F. and T.S.), the Ministry for Science and Culture of the State of Lower Saxony (T.S.), Marie Curie Reintegration grant IRG 230828 (T.v.d.F.), Leverhulme Trust grant RPG-398 (T.v.d.F.), Natural Environment Research Council grants NE/F016751/1 (T.v.d.F.), NE/N001141/1 (T.v.d.F. and D.J.W.), and NE/T011440/1 (D.J.W.), and National Science Foundation grant OCE-1503129 (J.F.A. and S.K.V.H.). Open Access funding is enabled by the DFG open access publication fund and the Carl von Ossietzky University Oldenburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S., D.J.W., and T.v.d.F. designed the research and led the draft of the manuscript. T.S. carried out the Nd isotope analysis. J.F.A. and S.K.V.H. provided the sample material and the U-Th dates. D.J.W. and S.K.V.H. collected Nd fractions during Pb and U-Th ion-exchange chromatography, respectively. All authors contributed to the data interpretation and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Brian Haley and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Struve, T., Wilson, D.J., Hines, S.K.V. et al. A deep Tasman outflow of Pacific waters during the last glacial period. Nat Commun 13, 3763 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31116-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31116-7

This article is cited by

-

Oxygen isotope constraints on the ventilation of the modern and glacial Pacific

Climate Dynamics (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.