Abstract

Copper hydrides are important hydrogenation catalysts, but their poor stability hinders the practical applications. Ligand engineering is an effective strategy to tackle this issue. An amidinate ligand, N,N′-Di(5-trifluoromethyl-2-pyridyl)formamidinate (Tf-dpf) with four N-donors has been applied as a protecting agent in the synthesis of stable copper hydride clusters: Cu11H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2 (Cu11) with three interfacial μ5-H and [Cu12H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2]·OAc (Cu12) with three interstitial μ6-H. A solvent-triggered reversible interconversion between Cu11 and Cu12 has been observed thanks to the flexibility of Tf-dpf. Cu11 shows high activity in the reduction of 4-nitrophenol to 4-aminophenol, while Cu12 displays very low activity. Deuteration experiments prove that the type of hydride is the key in dictating the catalytic activity, for the interfacial μ5-H species in Cu11 are involved in the catalytic cycle whereas the interstitial μ6-H species in Cu12 are not. This work highlights the role of hydrides with regard to catalytic hydrogenation activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Copper hydrides have historically been studied for their exciting structural chemistry and applications in hydrogenation catalysis and hydrogen-storage technology1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Recently, intense attention has been paid to synthesize atomically precise copper hydride clusters. A series of copper hydride clusters with bidentate ligands have been reported, which contain bridging (μ-H), capping (μ3-H) and interstitial (μ(4−6)-H) hydrides8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. The precise control over number of hydrides and their arrangements within these copper hydride clusters could provide valuable possibilities in modulating their catalytic hydrogenation activity. However, these copper hydride clusters are usually not stable enough and lose their identity quickly in solution17,18,19, which presented synthetic difficulties and limited their wide application.

Surface organic ligands are critical in the construction and stabilization of atomically precise metal nanoclusters20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, ligand engineering is an important approach in promoting the stability of copper hydrides. Envisioning multidentate amine ligands could provide stronger protection to metal clusters due to their multiple binding sites and their anionic nature which is helpful for ligating cationic metal ions28,29,30,31,32, we chose an amidinate ligand, N,N′-Di(5-trifluoromethyl-2-pyridyl)formamidinate (Tf-dpf) containing four N-donors, as the protecting agent for copper hydride clusters. Such a strong protection of ligand shell favors the high stability of copper hydride clusters. Moreover, Tf-dpf has a flexible linear structure favoring the generation of metal cluster diversity30, which may be constructive in establishing structure-property relationships in terms of hydrogenation catalysis.

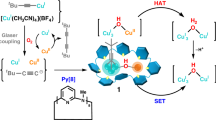

Herein, we report two amidinate-protected copper hydride clusters Cu11H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2 (Cu11) and [Cu12H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2]·OAc (Cu12), and their reversible interconversion (Fig. 1). The hydride positions in Cu11 and Cu12 were further confirmed by a machine-learning model based on convolutional neural networks (CNN) and trained on published structures of copper hydride clusters from neutron diffraction. It is quite unexpected that Cu11 showed high activity in the reduction of 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) to 4-aminophenol (4-AP), while Cu12 displayed very low activity. Structural determination of these two clusters revealed that the type of hydride is the key in dictating the catalytic activity. Cu11 has three interfacial μ5-H and Cu12 has three interstitial μ6-H. Deuterated catalytic experiments confirmed that the μ5-H of Cu11 is involved in the catalytic cycle whereas the μ6-H of Cu12 is not active. These findings are not only helpful for understanding the catalytic mechanism, but also instructive for the design and synthesis of efficient hydrogenation catalysts.

Results

Synthesis and characterization

HTf-dpf ligand was synthesized by heating the mixture of 5-(trifluoromethyl)-2-aminopyridine and excess triethyl orthoformate (TEOF) at 120 °C under nitrogen atmosphere (Supplementary Fig. 1)33. The preparation of Cu12 involves the direct reduction of a mixture of Cu(OAc) and HTf-dpf/Et3N with a mild reducing agent, Ph2SiH2 in a mixed CH2Cl2/CH3OH solvent. Cu11 was obtained by changing the reaction solvent to CH2Cl2/DMSO (dimethylsulfoxide), and then crystallized from CH2Cl2 and n-hexane. 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of Cu11 (Supplementary Fig. 2a) and Cu12 (Supplementary Fig. 3a) in CD3OD identified four sets of aromatic resonances corresponding to Tf-dpf ligands. Three OAc− in Cu12 are divided into two groups in a 2:1 ratio based on their environments. Three hydrides in Cu11 gave 1H NMR signals at 2.34 (2H) and 3.15 (1H) ppm, and similar 1H NMR shifts were found at 1.46–2.80 ppm for [Cu20H11(S2P(OiPr)2)9]17, and 2.18-3.44 ppm for [Cu29Cl4H22(Ph2phen)12]Cl (Ph2phen = 4, 7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline)34. The observed values of Cu12 at 5.64 (2H) and 7.16 (1H) ppm are comparable to those in Cu28H16(dppe)4((4-isopropyl)thiophenol)4(CH3CO2)6Cl2 at 3.4-6.3 ppm35, and the encapsulated hydrides in [Cu8H{S2CC(CN)2}6]5− and [Cu8H{S2C(NEt2)}6]− at 7.02 and 7.6 ppm36,37, respectively. In addition, 19F NMR of Cu11 (Supplementary Fig. 2b) and Cu12 (Supplementary Fig. 3b) in CD3OD show one singlet at −63.28 and −63.88 ppm, respectively (free HTf-dpf presents at −60.21 ppm, Supplementary Fig. 1b), suggesting that the six Tf-dpf ligands in Cu11 and Cu12 are in similar environments, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 2a, the positive ESI-MS spectrum of Cu11 shows two prominent peaks, corresponding to the molecular ion [Cu11H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2]+ (m/z = 2819.64) and [Cu11H3(Tf-dpf)5(OAc)2]+ (m/z = 2484.56). The spectrum of Cu12 gave signal of molecular ion [Cu12H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2]+ at m/z = 2882.51 (Fig. 2b). The observed isotopic patterns of the clusters are in perfect agreement with the simulated. UV–vis absorption spectra of Cu11 and Cu12 in MeOH display three prominent absorption bands at 238, 288, and 340 nm, which are corresponding to the intraligand transitions of the Tf-dpf ligand, as similar bands are found in HTf-dpf (Supplementary Fig. 4).

To our surprise, Cu11 and Cu12 are very stable under ambient conditions. In the solid state, they are air and moisture stable (Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, Cu11 and Cu12 are stable in solution (even in polar solvents such as CH2Cl2) for 2 weeks (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Molecular structures

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) structural analysis (Supplementary Table 1) revealed that Cu11 comprises a Cu11H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2 cluster (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7), wherein six Tf-dpf ligands are ligated to Cu11(μ5-H)3 core in a linear pattern (four in motif A and two in motif B) with Cu–N bond lengths ranging from 2.026(4) to 2.131(4) Å (Supplementary Table 2). Two OAc− anions bind the two copper atoms at the ends of the linear Cu11(μ5-H)3 unit, giving the Cu−O bond lengths of 2.021(4) to 2.038(4) Å. The metal core of Cu11 could be regarded as the fusion of three edge-sharing rectangular pyramids. The Cu…Cu distances of the Cu11 skeleton range from 2.428(1) to 2.749(1) Å.

The structure of Cu12 includes a [Cu12H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2]+ cationic cluster (Fig. 3b) and a OAc− counter anion (Supplementary Fig. 8). The coordination modes of OAc− in Cu12 are similar to that of Cu11, with the Cu–O bond lengths ranging from 2.111(5) to 2.120(4) Å. The six Tf-dpf ligands in Cu12 adopt distorted motif A binding mode, with the Cu–N bond ranging from 2.000(5)–2.096(5) Å. The metal core of Cu12 could be regarded as the fusion of three face-sharing octahedra. Moreover, the 12 copper atoms in Cu12 are typical hexagonal close-packed type structure with ABAB packing mode (Supplementary Fig. 9). Cu…Cu distances of Cu12 skeleton range from 2.497(1)–2.764(1) Å, which is much longer than that of Cu11. Shorter Cu…Cu contact in Cu11 could be attributed to the linear coordination mode of Tf-dpf, while Tf-dpf adopts zigzag coordination mode in Cu12 to form relatively longer Cu…Cu contacts (average 2.657 Å) as shown in Fig. 3c. These Cu…Cu distances observed in Cu12 is comparable to the average Cu…Cu contact of 2.66 Å in the Cu6 octahedral structures38.

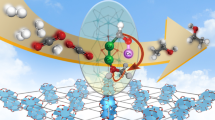

Neural network prediction of hydride sites

Even though the location of H atoms by SCXRD is difficult, the hydrides in Cu11 and Cu12 could be estimated based on the charge distribution in their cluster frameworks and refined freely. Although attempts to grow single crystals suitable for neutron diffraction were unsuccessful, we applied a recently developed machine-learning model based on CNN to confirm the hydride location. The CNN method can quickly predict hydride occupancy in a Cu cluster given the heavy-atom coordinates39,40. We fed the SCXRD-determined positions of heavy-atoms into the CNN model and predicted the most probable sites in the two clusters. As shown in Fig. 4, the CNN model predicted close-to-1 occupancies in three sites for both the Cu11 and Cu12 clusters. The locations of these top three sites are shown in Fig. 4 insets; indeed, they exactly match the sites determined from SCXRD. Further density functional theory (DFT) geometry optimizations confirmed the stability of these clusters, as the cluster framework was well maintained after structural relaxation with hydrides at the predicted sites, and the SCXRD and DFT structures were in good agreement (Supplementary Table 2). For the sites with probability around 0.7–0.9, we would normally consider them as well, but the Cu11 and Cu12 clusters are much smaller and their structures are much simpler, quite resembling the structures in our training set. So the most probable three sites from our machine-learning model happen to be the most viable model that agrees with the SCXRD and is further confirmed by DFT.

In Cu11, three hydrides are disposed in the center of Cu4 square with an approximate square pyramidal μ5 coordination mode. Of note, the positions of the three μ5-H in Cu11 relative to the centers of Cu4 squares differ slightly: the middle one is right in the center of Cu4 square and the other two are deviated from the centers of Cu4 squares (close to the OAc−). The Cu-H distances were found in the range from 1.61(6) to 2.02(7) Å. In Cu12, three hydrides are disposed in the center of Cu6 octahedra with a μ6-H coordination mode. Similar to that in Cu11, the middle H was found to be right in the center of Cu6 octahedron, while the other two show offsets closing to the OAc−. The Cu-μ6-H distance in Cu12 ranges from 1.71(8) to 2.02(6) Å.

Interconversion

Interestingly, it was found that the interconversion between Cu11 and Cu12 could be triggered by solvents. The interconversion involves the adding a Cu+ ion to Cu11 or leaving of a Cu+ ion from Cu12. Dissolving Cu12 in DMSO led to the leaving of a Cu+ ion to form Cu11, while the reaction of Cu11 with CuOAc (1 equiv) in CH3OH converted it back to Cu12. The interconversion was not affected by O2 for the same interconversion was observed both in the air and under nitrogen atmosphere. The flexible arrangement of the N donors of Tf-dpf makes such an interconversion possible, which allows keeping stable ligation to metal ions in adjusting to the structural changes between Cu11 and Cu12. To better understand the cluster-to-cluster transformation process, we monitored the cluster core transformation process (Cu12 to Cu11) by ESI-MS measurements (Fig. 5a). The MeOH solution of Cu12 features one prominent peak attributed to [Cu12H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2]+. The freshly prepared Cu12 solution in DMSO showed peaks corresponding to [Cu11H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2]+ along with a weak peak attributed to [Cu11H3(Tf-dpf)5(OAc)2]+ within 5 min. Then the peaks of Cu11 keep increasing with time, and after 120 min the spectrum features only prominent peaks of Cu11 while the peak of Cu12 disappeared, indicating the complete conversion from Cu12 to Cu11.

We then monitored a solution of Cu12 in DMSO-d6 at room temperature by measuring its 19F NMR spectra at different times. A slight upfield shift of ∼2.6 ppm of Cu12 and Cu11 was found in DMSO-d6 compared with in CD3OD. As shown in Fig. 5b, the signal at −61.24 ppm of Cu12 gradually disappeared, while that at −60.68 ppm of Cu11 gradually grew with increasing time, indicating a transformation of Cu12 to Cu11 in DMSO at room temperature. Based on the integration ratios relative to the internal standard, the conversion of Cu12 to Cu11 is virtually quantitative.

Given the different numbers of Cu atoms in Cu11 and Cu12, the transformation between the two clusters is not isomerization. As shown in (Supplementary Fig. 10), the OAc− only binds two out of the three terminal copper atoms of the Cu12 core, and the other one copper atom could be regarded as an unsaturated site. Thus, it is hypothesized that the transformation of Cu12 to Cu11 is attributed to the binding ability of DMSO, which anchors on the unsaturated copper atom and removes it from the cluster. As a result, the binding mode of Tf-dpf in Cu12 is distorted motif A, which leads to the twisting of two Cu3 units and then the framework rearrangement to form Cu11 (Fig. 6). Moreover, the conversion of Cu11 to Cu12 through adding CuOAc in CH3OH proves that Cu11 is likely to combine free Cu ions to generate Cu12 (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Hydrogenation catalysis

Synthesis of anilines or amines from the corresponding nitro compounds is an important process in both of the laboratory and the chemical industry due to their versatility in several biologically active natural products, pharmaceuticals, and dyes41. Transition metal-catalyzed hydrogenation is an important route for the transformation of nitro groups to amine groups42,43. Thus, the reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP by NaBH4 was chosen as a model reaction to investigate the catalytic performance of Cu11 and Cu12. Considering that Cu11 and Cu12 are insoluble in water, this catalytic reaction belongs to heterogeneous catalysis.

The reduction process monitored by measuring the intensity change of 400 nm peak (4-NP) in UV/vis absorption spectroscopy. As the catalytic reaction proceeded in the presence of Cu11, the intensity of 400 nm peak decreased rapidly and disappeared within 10 min (Fig. 7a), indicating the complete conversion of 4-NP to 4-AP (λmax = 295 nm in water). In comparison, only 5% 4-NP could be reduced to 4-AP with equivalent Cu12 catalyst even when the time was extended to 30 min, and the completion of reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP needed 10 h (Supplementary Fig. 12). It is quite interesting that two copper hydride clusters with similar structures show distinctly different activity in the hydrogenation reaction (Fig. 7b), which prompts us to pay efforts in mechanism study in terms of the role of hydrides.

a UV–Vis spectra showing gradual reduction of 4-NP catalyzed by Cu11. b Plot of −ln(c/c0) vs. reaction time during the reduction of 4-NP with Cu11 and Cu12 catalysts. c ESI-MS of Cu12 after catalysis with NaBD4. Inset: the comparison of the measured (black trace) and simulated isotopic distribution patterns of [Cu12H3(Tf-dpf)6Cl2]+ (green, 2834.5), [Cu12H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)Cl]+ (blue, 2858.5), and [Cu12H3(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2]+ (red, 2882.5). d ESI-MS of Cu11 after catalysis with NaBD4. Inset: the comparison of the measured (black trace) and simulated (red trace) isotopic distribution patterns of [Cu11HD2(Tf-dpf)5(OAc)2 + Na]+ (2844.6) and [Cu11HD2(Tf-dpf)5(OAc)]+ (2762.6).

Three major steps were generally thought to be involved in transition metal-catalyzed reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP41,44, and the formation of [M]–H species as well as the B–H bond cleavage was considered to be the rate-determining step. Therefore, we carried out an experiment using Cu11 and Cu12 as the catalysts for the reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP with NaBD4 in place of NaBH4. In the cases of Cu12, no peak belongs to deuterated cluster was found in the ESI-MS spectrum after catalysis with NaBD4 (Fig. 7c), which indicates that the encapsulated μ6-H of Cu12 were shielded from interaction with substrates. Therefore, Cu12 showed very low catalytic activity. On the contrary, the ESI-MS of Cu11 after catalysis with NaBD4 showed new peaks at 2762.6 and 2844.6 in addition to the expected peak of 2484.6 ([Cu11H3(Tf-dpf)5(OAc)2]+) (Fig. 7d). These two new peaks could be attributed to [Cu11HD2(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)]+ and [Cu11HD2(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2 + Na]+, respectively, which indicates that hydrides in Cu11 were replaced by D atoms from NaBD4, i.e., the μ5-H species of Cu11 were involved in the catalytic cycle. These facts reveal that the high catalytic activity of Cu11 is related to the formation of μ5-H species on the cluster. Moreover, it is noted that Cu11 is relatively robust and can be re-used after centrifugation. Even after seven cycles, Cu11 retains its high activity (Supplementary Table 3). Previously reported copper hydride clusters including Stryker’s reagent are usually moisture- and air-sensitive. Other copper hydride clusters such as [Cu3H(dppm)3(OAc)2]45,46 and [Cu8H6(dppy)6](OTf)27 are stable in solution for less than 3 days. Cu11 and Cu12 are stable in CH2Cl2 for at least 2 weeks, their good stability makes them promising copper hydride catalysts for various applications.

Overall, Cu11 and Cu12 present a pair of valuable copper hydride clusters for correlating the structures and properties. They have identical amidinate ligands, similar metal atom arrangement, but different hydride location and distinct catalytic performance, which demonstrates the importance of the location of hydrides for efficient hydrogenation catalysis45. This information will be instructive in the design, synthesis and selection high performance hydrogenation catalysts.

Discussion

In summary, we have synthesized two stable copper hydride clusters Cu11 and Cu12 with the flexible amidinate ligand Tf-dpf. Because the multidentate amine ligand Tf-dpf has a negative charge and four binding N donors, it could provide strong binding to metal centers. Such a strong protection of ligand shell favors the high stability of copper hydride clusters. The compositions of these two title clusters have only one copper atom difference, but their structures and hydride positions are different. Cu11 and Cu12 show totally distinct catalytic performance in the reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP. Cu11 bearing μ5-H is very active while Cu12 with μ6-H display very low activity. Deuterated catalytic experiments prove that the hydrides at different location play key a role in the catalytic cycles. This work presents valuable information for understanding the hydrogenation process of copper hydride catalysts at atomic level, which helps optimize the design and synthesis of stable and active copper hydride catalysts.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

5-(trifluoromethyl)-2-aminopyridine (97%) was purchased from Meryer. Triethyl orthoformate (TEOF, 99%) and Et3N (99%) were purchased from Aladdin. H2SiPh2 was purchased from Bidepharm, China. CuOAc (93%) was purchased from TCI. Other reagents employed were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All chemical reagents employed were used without further purification.

Synthesis of N,N′-Di(5-trifluoromethyl-2-pyridyl)formamidine (HTf-dpf)

Excess TEOF (1.8571 g, 17.5 mmol) was added to of 5-(trifluoromethyl)-2-aminopyridine (3.2422 g, 20.0 mmol) and heated at 120 °C under a low nitrogen stream for 5 h. The excessed TEOF and ethanol formed during the reaction were distilled off, and the product was recrystallized from petroleum ether/methanol (5:1). Yield: 2.97 g, 89%.

Anal. UV–Vis (λ, nm): 231; 267; 323. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 11.41 (s, 1H, –CH–), 9.77 (s, 1H, NH), 8.70 (s, 2H, py), 8.11–8.08 (dd, 2H, py), 7.22 (s, 2H, py). 19F NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): −60.21. 13C NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ, ppm): 151.70, 146.17, 136.20, 128.70, 126.00, 123.31, 120.61.

Synthesis of [Cu12(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2H3]·OAc (Cu12)

In total, 3 ml CH2Cl2/CH3OH (v:v = 2:1) mixture of Cu(OAc) (24 mg, 0.2 mmol), HTf-dpf (0.1 mmol, 33.4 mg), and excess Et3N (20 ul) was stirred for 5 min first, then H2SiPh2 (0.1 mmol, 18 ul) was added. The solution color changed from green to yellow in 10 min. The mixture was stirred for 3 h and evaporated to dryness to give a yellow solid, which was washed with n-hexane (3 × 2 ml), then dissolved in 4 ml CH2Cl2/CH3OH (v:v = 3:1). The resulted solution was centrifuged for 2 min at 9000 r/min, and the yellow supernatant was collected and subjected to diffusion with n-hexane to afford light yellow crystals after 2 days in 27.4 mg, 56% yield (based on Cu).

Anal. UV–Vis (λ, nm): 238; 288; 341. ESI-MS (CH3OH): 2882.51 ([Cu12(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2H3]+). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): 8.95 (m, 6H, –CH–), 8.55 (m, 12H, py), 7.59–7.57 (m, 12H, py), 7.23–7.20 (m, 12H, py), 7.16 (s, 1H, hydride), 5.64 (s, 2H, hydride), 3.59 (s, 3H, –CH3), 2.68 (s, 6H, –CH3). 19F NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): −63.88.

Synthesis of Cu11(Tf-dpf)6(OAc)2H3 (Cu11)

In total, 3 ml CH2Cl2/DMSO (v:v = 5:1) mixture of Cu(OAc) (24 mg, 0.2 mmol), HTf-dpf (0.1 mmol, 33.4 mg), and excess Et3N (20 ul) was stirred for 5 min first, then H2SiPh2 (0.1 mmol, 18 ul) was added. The solution color changed from green to yellow in 10 min. The mixture was stirred for 3 h and evaporated to remove the CH2Cl2 solvent. The crude product was washed by 5 ml CH2Cl2/n-hexane (v:v = 1:4) for three times, then dissolved in 4 ml CH2Cl2. The resulted solution was centrifuged for 2 min at 9000 r/min, and the orange supernatant was collected and subjected to diffusion with n-hexane to afford light orange crystals after 2 days in 24.2 mg, 47% yield (based on Cu).

Anal. UV–Vis (λ, nm): 240; 287; 338. ESI-MS (CH3OH): 2819.64 ([Cu11(Tf–dpf)6(OAc)2H3]+) and 2484.56 ([Cu11(Tf-dpf)5(OAc)2H3]+). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): 8.98–8.54 (m, 12H, –CH– and py), 7.59–7.50 (m, 12H, py), 7.21–7.17 (m, 12H, py), 3.15 (s, 1H, hydride), 2.60 (s, 6H, –CH3), 2.34 (s, 2H, hydride). 19F NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): −63.28.

Catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol

The water solution of 4-NP (1 ml, 20 mM), Cu11 or Cu12 (1 mg) was mixed, and the mixture was stirred for 10 min at room temperature. Time-resolved UV–vis spectra were taken immediately after the addition of NaBH4 solid (50 mg, 1.3 mmol). The progress of the reaction was tracked by monitoring the change in intensity of 4-NP peak at 400 nm as a function of time. After reaction of Cu11, the reaction solution was centrifuged, and the catalysts was washed with 3 ml H2O for three times. Then the catalysts solid was dried under reduced pressure and re-used as fresh.

Neural network prediction of hydride sites

We employed the recently developed deep-learning model to predict hydride sites in our clusters. The model was based on CNN and trained on Cu-H clusters with hydride sites determined by neutron diffraction. This model takes as input the heavy-atom coordinates of a cluster from the single-crystal X-ray diffraction and then outputs the occupancy for each possible hydride site in the cluster. The training data are based on 23 different copper hydride clusters from the Cambridge Structural Database whose hydride locations have been determined by neutron diffraction. The 23 structures were further chunked into 674 boxes of possible hydride sites that were used for training of CNN. The details of the CNN and its architecture can be found in the previous work39,40 and their Supporting Information. The trained CNN can classify a possible site for hydride in a given cluster with accuracy higher than 94%. In the present work, the X-ray structures of the Cu11 and Cu12 clusters (namely, coordinates of Cu, C, N, F, and O in the cluster) were used as input into the machine-learning model which then predicted hydride occupancies and ranked the hydride sites. Since there are only three hydrides in the Cu11 and Cu12 clusters, one can simply pick the top-ranked sites and examine the top three by inspection, followed by DFT geometry optimization for confirmation using the VASP code.

Physical measurements

UV–Vis absorption spectra was recorded on cary5000. Mass spectra were recorded on a high-resolution Fourier transform ICR spectrometer with an electrospray ionization source in positive mode. Nuclear magnetic resonance data were recorded on a Bruker Avance II spectrometer (500 MHz).

X-ray crystallography

Intensity data of compounds Cu11 and Cu12 were collected on an Agilent SuperNova Dual system (Cu Kα) at 173 K. Absorption corrections were applied by using the program CrysAlis (multi-scan). The structures of Cu11 and Cu12 were solved by direct methods. Non-hydrogen atoms except solvent molecules and counteranions were refined anisotropically by least-squares on F2 using the SHELXTL program. For Cu12, the -CF3 groups (F7–F9, F22–F24) were disordered over two sites with an occupancy factor of 0.5/0.5. SQUEEZE routine in PLATON was employed in the structural refinements due to large solvent voids. In addition, isor and rigu constraints have been applied due to geometric requirements of the ligands.

Computational methods

DFT calculations were performed with the quantum chemistry program Turbomole V7.147. The Def2-SV(P) basis sets48 were used for C, N, O, H, F. The Def2-TZVP basis sets49 were used for Cu. Geometry optimization was done with the functional of Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof50.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article (see Supplementary Table 1) have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers CCDC 2100815 (Cu11) and CCDC 2100816 (Cu12). These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Jordan, A. J., Lalic, G. & Sadighi, J. P. Coinage metal hydrides: synthesis, characterization, and reactivity. Chem. Rev. 116, 8318–8372 (2016).

Liu, X. & Astruc, D. Atomically precise copper nanoclusters and their applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 359, 112–126 (2018).

Sun, C. et al. Hydrido-coinage-metal clusters: rational design, synthetic protocols and structural characteristics. Coord. Chem. Rev. 427, 213576 (2021).

Zhu, S., Niljianskul, N. & Buchwald, S. L. A direct approach to amines with remote stereocentres by enantioselective CuH-catalysed reductive relay hydroamination. Nat. Chem. 8, 144–150 (2016).

Wang, Y. M. & Buchwald, S. L. Enantioselective CuH-catalyzed hydroallylation of vinylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5024–5027 (2016).

Deutsch, C. & Krause, N. CuH-catalyzed reactions. Chem. Rev. 108, 2916–2927 (2008).

Yuan, S.-F. et al. A stable well-defined copper hydride cluster consolidated with hemilabile phosphines. Chem. Commun. 57, 4315–4318 (2021).

Dhayal, R. S., van Zyl, W. E. & Liu, C. W. Polyhydrido copper clusters: synthetic advances, structural diversity, and nanocluster-to-nanoparticle conversion. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 86–95 (2016).

Chakrahari, K. K. et al. [Cu13{S2CNnBu2}6(acetylide)4]+: a two-electron superatom. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 14704–14708 (2016).

Dhayal, R. S. et al. Diselenophosphate-induced conversion of an achiral [Cu20H11{S2P(OiPr)2}9] into a chiral [Cu20H11{Se2P(OiPr)2}9] polyhydrido nanocluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 13604–13608 (2015).

Edwards, A. J. et al. Chinese puzzle molecule: a 15 hydride, 28 copper atom nanoball. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 7214–7218 (2014).

Huang, R.-W. et al. [Cu23(PhSe)16(Ph3P)8(H)6]·BF4: atomic-level insights into cuboidal polyhydrido copper nanoclusters and their quasi-simple cubic self-assembly. ACS Mater. Lett. 3, 90–99 (2020).

Lee, S. et al. [Cu32(PET)24H8Cl2](PPh4)2: a copper hydride nanocluster with a bisquare antiprismatic core. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 13974–13981 (2020).

Nakamae, K., Nakajima, T., Ura, Y., Kitagawa, Y. & Tanase, T. Facially dispersed polyhydride Cu9 and Cu16 clusters comprising apex-truncated supertetrahedral and square-face-capped cuboctahedral copper frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 2262–2267 (2020).

Yuan, P. et al. Ether-soluble Cu53 nanoclusters as an effective precursor of high-quality CuI films for optoelectronic applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 835–839 (2019).

Tang, Q. et al. Lattice-hydride mechanism in electrocatalytic CO2 reduction by structurally precise copper-hydride nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9728–9736 (2017).

Dhayal, R. S. et al. A nanospheric polyhydrido copper cluster of elongated triangular orthobicupola array: liberation of H2 from solar energy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 4704–4707 (2013).

Barik, S. K. et al. Polyhydrido copper nanoclusters with a hollow icosahedral core: [Cu30H18{E2P(OR)2}12] (E=S or Se; R = nPr, iPr or iBu). Chem. Eur. J. 26, 10471–10479 (2020).

Chakrahari, K. K. et al. Isolation and structural elucidation of 15-nuclear copper dihydride clusters: an intermediate in the formation of a two-electron copper superatom. Small 17, 2002544 (2020).

Nasaruddin, R. R., Chen, T., Yan, N. & Xie, J. Roles of thiolate ligands in the synthesis, properties and catalytic application of gold nanoclusters. Coord. Chem. Rev. 368, 60–79 (2018).

Kang X. & Zhu, M. Z. Metal nanoclusters stabilized by selenol ligands. Small 15, 1902703 (2019).

Wan, X.-K., Wang, J.-Q., Nan, Z.-A. & Wang, Q.-M. Ligand effects in catalysis by atomically precise gold nanoclusters. Sci. Adv. 3, 1701823 (2017).

Kurashige, W., Yamaguchi, M., Nobusada, K. & Negishi, Y. Ligand-induced stability of gold nanoclusters: thiolate versus selenolate. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 2649–2652 (2012).

Guan, Z. J. et al. Thiacalix [4] arene: new protection for metal nanoclusters. Sci. Adv. 2, 1600323 (2016).

Lei, Z., Wan, X.-K., Yuan, S.-F., Wang, J.-Q. & Wang, Q.-M. Alkynyl-protected gold and gold-silver nanoclusters. Dalton. Trans. 46, 3427–3434 (2017).

Liu, K. G., Gao, X. M., Liu, T., Hu, M. L. & Jiang, D. E. All-carboxylate-protected superatomic silver nanocluster with an unprecedented rhombohedral Ag8 core. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16905–16909 (2020).

Liu, W.-D., Wang, J.-Q., Yuan, S.-F., Chen, X. & Wang, Q.-M. Chiral superatomic nanoclusters Ag47 induced by the ligation of amino acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11430–11435 (2021).

Yuan, S.-F. et al. Robust gold nanocluster protected with amidinates for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 14345–14349 (2021).

Yuan, S.-F., Lei, Z., Guan, Z.-J. & Wang, Q. M. Atomically precise preorganization of open metal sites on gold nanoclusters with high catalytic performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 5225–5229 (2021).

Yuan, S.-F., Guan, Z.-J., Liu, W.-D. & Wang, Q.-M. Solvent-triggered reversible interconversion of all-nitrogen-donor-protected silver nanoclusters and their responsive optical properties. Nat. Commun. 10, 4032 (2019).

Kounalis, E., Lutz, M. & Broere, D. L. J. Cooperative H2 activation on dicopper(I) facilitated by reversible dearomatization of an “Expanded PNNP Pincer” ligand. Chem. Eur. J. 25, 13280–13284 (2019).

Desnoyer, A. N., Nicolay, A., Ziegler, M. S., Torquato, N. A. & Tilley, T. D. A dicopper platform that stabilizes the formation of pentanuclear coinage metal hydride complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 12769–12773 (2020).

Kombe, H., Limbach, H. H., Böhme, F. & Kunert, C. NMR studies of the tautomerism of Cyclo-tris(4-R-2,6-pyridylformamidine) in solution and in the solid state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 11955–11963 (2002).

Nguyen, T.-A. D. et al. Ligand-exchange-induced growth of an atomically precise Cu29 nanocluster from a smaller cluster. Chem. Mat. 28, 8385–8390 (2016).

Guo, Q. L. et al. Observation of a bcc-like framework in polyhydrido copper nanoclusters. Nanoscale 13, 19642–19649 (2021).

Liao, P. K. et al. A copper(I) homocubane collapses to a tetracapped tetrahedron upon hydride insertion. Inorg. Chem. 50, 8410–8417 (2011).

Liao, P. K. et al. Hydrido copper clusters supported by dithiocarbamates: oxidative hydride removal and neutron diffraction analysis of [Cu7(H){S2C(aza-15-crown-5)}6]. Inorg. Chem. 51, 6577–6591 (2012).

Kohn, R. D., Pan, Z., Mahon, M. F. & Kociok-Kohn, G. Trimethyltriazacyclohexane as bridging ligand for triangular Cu3 units and C-H hydride abstraction into a Cu6 cluster. Chem. Commun. 11, 1272–1273 (2003).

Wang, S., Wu, Z. L., Dai, S. & Jiang, D. E. Deep learning accelerated determination of hydride locations in metal nanoclusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 12289–12292 (2021).

Wang, S., Liu, T. & Jiang, D. E. Locating hydrides in ligand-protected copper nanoclusters by deep learning. Acs Appl. Mater. Int. 13, 53468–53474 (2021).

Zhao, P., Feng, X., Huang, D., Yang, G. & Astruc, D. Basic concepts and recent advances in nitrophenol reduction by gold- and other transition metal nanoparticles. Coord. Chem. Rev. 287, 114–136 (2015).

Tamiolakis, I., Fountoulaki, S., Vordos, N., Lykakis, I. N. & Armatas, G. S. Mesoporous Au–TiO2 nanoparticle assemblies as efficient catalysts for the chemoselective reduction of nitro compounds. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 14311–14319 (2013).

Wunder, S., Lu, Y., Albrecht, M. & Ballauff, M. Catalytic activity of faceted gold nanoparticles studied by a model reaction: evidence for substrate-induced surface restructuring. ACS Catal. 1, 908–916 (2011).

Sun, C. et al. Atomically precise, thiolated copper–hydride nanoclusters as single-site hydrogenation catalysts for ketones in mild conditions. ACS Nano 13, 5975–5986 (2019).

Fountoulaki, S. et al. Mechanistic studies of the reduction of nitroarenes by NaBH4 or hydrosilanes catalyzed by supported gold nanoparticles. ACS Catal. 4, 3504–3511 (2014).

Cook, A. W., Nguyen, T. D., Buratto, W. R., Wu, G. & Hayton, T. W. Synthesis, characterization, and reactivity of the group 11 hydrido clusters [Ag6H4(dppm)4(OAc)2] and [Cu3H(dppm)3(OAc)2]. Inorg. Chem. 55, 12435–12440 (2016).

Furche, F. et al. Turbomole. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 4, 91–100 (2014).

Weigend, F., Haser, M., Patzelt, H. & Ahlrichs, R. RI-MP2: optimized auxiliary basis sets and demonstration of efficiency. Chem. Phys. Lett. 294, 143–152 (1998).

Weigenda, F. & Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 3297–3305 (2005).

Ahlrichs, R., Bar, M., Haser, M., Horn, H. & Kolmel, C. Electronic structure calculations on workstation computers: the program system turbomole. Chem. Phys. Lett. 162, 165–169 (1989).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91961201, 21973116, 21631007 and 22001145) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M701863 and 2020T130343) and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (2224098).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.-M.W. proposed the research direction and guided the whole experiment. C.-Y.L. and S.-F.Y. conducted the synthesis and characterization. S.W. and D.-E.J. predicted hydride sites using deep-learning model. Z.-J.G. assisted analyzing the data. C.-Y.L. and Q.-M.W. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Lai-Sheng Wang and Prafulla K. Jha for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, CY., Yuan, SF., Wang, S. et al. Structural transformation and catalytic hydrogenation activity of amidinate-protected copper hydride clusters. Nat Commun 13, 2082 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29819-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29819-y

This article is cited by

-

Synthesis and Structure of Polyhydrido Copper Nanocluster [Cu14H10(PPh3)8(SPhMe2)3]+: Symmetry-Breaking by Thiolate Ligands to form Racemic Pairs of Chiral Clusters in Solid-State

Journal of Cluster Science (2024)

-

Atomically precise ultrasmall copper cluster for room-temperature highly regioselective dehydrogenative coupling

Nature Communications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.