Abstract

Globally, tropical forests are assumed to be an important source of atmospheric nitrous oxide (N2O) and sink for methane (CH4). Yet, although the Congo Basin comprises the second largest tropical forest and is considered the most pristine large basin left on Earth, in situ N2O and CH4 flux measurements are scarce. Here, we provide multi-year data derived from on-ground soil flux (n = 1558) and riverine dissolved gas concentration (n = 332) measurements spanning montane, swamp, and lowland forests. Each forest type core monitoring site was sampled at least for one hydrological year between 2016 - 2020 at a frequency of 7-14 days. We estimate a terrestrial CH4 uptake (in kg CH4-C ha−1 yr−1) for montane (−4.28) and lowland forests (−3.52) and a massive CH4 release from swamp forests (non-inundated 2.68; inundated 341). All investigated forest types were a N2O source (except for inundated swamp forest) with 0.93, 1.56, 3.5, and −0.19 kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 for montane, lowland, non-inundated swamp, and inundated swamp forests, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Forest soils play a major role in the biosphere–atmosphere exchange of methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), the second and third most important greenhouse gases, respectively, after carbon dioxide (CO2). Tropical forests in particular are considered to be one of the main natural terrestrial sources of N2O1,2 and major sinks for atmospheric CH43. While strong uptake rates for CH4 can mostly be attributed to diffusion, facilitated by the coarse texture of highly weathered tropical lowland forest soils3, high N2O emissions are mostly attributed to excess nitrogen relative to phosphorus in these soils4. Within the tropics, Congo Basin forests have been postulated, through process-based modeling, as a major hotspot for N2O emissions5. At this scale, such transitive emission modeling is highly consequential, since the Congo Basin comprises the second largest contiguous tropical forest on Earth which blankets approximately half of the 3.6 million km2 total basin area. However, despite its likely importance for the global CH4 and N2O budget, in situ N2O and CH4 flux measurements from the Congo Basin are limited. Since central African forests have been shown to differ fundamentally from other tropical biomes in terms of species richness6,7, structure, biomass8, and carbon uptake9, ecological and biogeochemical conclusions cannot simply be inferred from elsewhere. In addition, the Congo Basin is subjected to a uniquely high fire-derived N deposition load10, which might impose large ramifications on soil-atmosphere N2O and CH4 exchange by potentially stimulating N2O production while increasing CH4 uptake11. Consequently, constraining soil-atmosphere N2O and CH4 fluxes through on-ground observations is paramount to adequately partition sources of global atmospheric N2O and CH4, especially in data-poor but supposedly hotspot-regions like the Congo Basin.

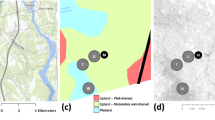

To the best of our knowledge, only one study has reported terrestrial in situ CH4 data from the Congo Basin12 and there are no data for N2O. This single study is complemented by only a few N2O and CH4 measurements from African tropical forest soils outside the Congo Basin (Republic of Congo13; Cameroon14,15,16; Kenya17,18,19,20; Tanzania21; Ghana22; Uganda23), further highlighting central Africa as a blind spot for empirical flux measurements (Fig. 1). Consequently, this study aims to address the high uncertainty surrounding the Congo Basin’s N2O and CH4 budget. To achieve this, we quantified seasonal soil–atmosphere fluxes of N2O and CH4 from the three major tropical forest types (montane, lowland, swamp) within the Congo Basin at a weekly to fortnightly resolution using the static chamber method24. Initial short-term campaigns with daily measurements were conducted in 2016 and 2017 at three lowland locations (Maringa-Lopori-Wamba Landscape, Yangambi Biosphere Reserve, Yoko Forest Reserve) and one montane location (Kahuzi-Biéga National Park) to constrain spatiotemporal variation (Fig. S1). Expanding on these short-term expeditions, long-term observation ‘core sites’ were established in Yoko Forest Reserve and Kahuzi-Biéga National Park, as lowland and montane representatives, starting in 2016 and 2017, respectively. These two long-term core sites were subsequently expanded by the addition of a seasonally inundated swamp forest core site in 2019 (Jardin Botanique d’Eala). Including the initial short-term campaigns, 1558 individual soil–atmosphere flux measurements were undertaken for this study (Table S1). During the short-term campaigns, we also sampled N2O isotopes at all five sites to explore the underlying N2O source processes (n = 63). Lastly, as aquatic ecosystems are increasingly considered as potential emission hotspots within the terrestrial landscape, we also report dissolved N2O and CH4 concentrations from headwater streams draining the same catchments in which soil flux core sites were located. Stream samples were collected for one year together with the soil flux measurements. Headwater streams and low-order tributaries in particular are believed to be important outlets for ecosystem gaseous losses25. Fluxes previously measured from the Congo River main stem26 likely underestimate total aquatic losses by a significant margin, since relatively high fluxes have been observed to take place higher in the watershed27.

2019 forest cover of sub-Saharan Africa (0% white, 100% dark green)78 with Congo Basin boundary delineation in black showing all currently published in situ African tropical forest studies on N2O and/or CH4 in white triangles12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 and this study in yellow (terrestrial) and blue (aquatic). Circles represent core long-term observation sites and squares represent supporting sites. Riverine dissolved CH4 and N2O samples were taken from headwater streams draining the same catchments in which the core sites were located.

Results and discussion

Fluxes of N2O and CH4 from Congo Basin soils

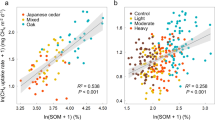

For both CH4 and N2O, there was considerable spatial (between chambers within sites; Table S2) and temporal (within site, across weeks; Table S2) variance, as is common for both gas species. However, even though soil moisture and temperature are known drivers of N2O and CH4 fluxes, the combined variability explained by water-filled pore space (WFPS) and soil temperature was very low. In the lowland forest, WFPS and temperature only explained 5% and <1% of N2O and CH4 flux variability, respectively. In the swamp and montane forests, they explained slightly more but still marginal proportions of flux variability (swamp = N2O 29%; CH4 26%; montane = N2O 27%; CH4 33%). These results suggest that the changes of both N2O and CH4 fluxes within a forest type are driven by factors other than soil temperature and WFPS, which is not surprising given the low temporal variation of soil temperature and WFPS within a given location (Fig. S2).

CH4 fluxes ranged from strong uptakes of −5.36 nmol m−2 s−1 at the montane site to a massive maximum release of 2608.12 nmol m−2 s−1 at the inundated swamp forest with a variable geometric mean [95% CIs] flux depending on forest type (Fig. 2a). While montane and lowland forests soils sequestered −4.28 [−4.70, −3.80] and −3.52 [−4.29, −2.68] kg CH4-C ha−1 yr−1, respectively, the swamp forest site, under both flooded and dry conditions, was a CH4 source, releasing 2.68 [−3.03, 12.09] from non-inundated and 341 [147, 798] kg CH4-C ha−1 yr−1 from inundated areas. It is important to note, however, that the non-inundated swamp forest area was a CH4 sink for most of the study period but the geometric mean was strongly influenced by sporadic high emissions events, as can be seen from the density distribution functions (Fig. S3). One erratic high CH4 flux was also observed for a single chamber at the lowland site (37.6 nmol m−2 s−1, not shown) which was likely caused by transient termite activity, known to result in anomalously high CH4 emissions14.

a Spatiotemporal variation of soil CH4 fluxes measured at three different tropical forest types in the DR Congo between 2016 and 2020 and b corresponding dissolved CH4 measured in headwater streams draining the soil flux core site catchment. Dashed lines indicate CH4 at equilibrium with the atmosphere (0.03 µg C L−1). c Spatiotemporal variation of soil N2O fluxes measured at three different tropical forest types in DR Congo between 2016 and 2020 and d corresponding dissolved N2O measured in headwater streams draining the soil flux core site catchment. Dashed lines indicate N2O at equilibrium with the atmosphere (0.36 µg N L−1). Montane forest (Kahuzi-Biéga National Park (triangles)), lowland forest (Maringa-Lopori-Wamba Landscape (star), Yangambi Biosphere Reserve (cross symbols), Yoko Forest Reserve (plus symbols)), swamp forest (Jardin Botanique d’Eala (closed circles inundated, open circles non-inundated)). Note, for visualization purposes data was pooled into weekly classes irrespective of sampling year.

Lowland forest uptake rates (−3.52 kg CH4-C ha−1 yr−1) agree well with previous studies in African tropical forests (Cameroon, −3.54 kg CH4-C ha−1 yr−1)14 but are higher compared to the tropical forest world average (−2.50 kg CH4-C ha−1 yr−1)3. Similarly, montane uptake rates (−4.28 kg CH4-C ha−1 yr−1) are higher than in other Afromontane tropical forest studies with estimates of −3.219 and −3.12 kg CH4-C ha−1 yr−1 21. Overall, the measured CH4 uptake of lowland and montane study soils fell generally toward the high end of the range of other tropical montane and lowland forest sites (Veldkamp et al., 2013 and references therein). Our inundated swamp forest flux range (0−9870 kg C-CH4 ha−1 yr−1) is higher than the range of CH4 fluxes reported from an inundated forest also located in the Cuvette Centrale (27–1506 kg C-CH4 ha−1 yr−1)12, which is to our knowledge the only soil CH4 study done previously within the confines of the Congo Basin. Despite the swamp forest covering only ~7% of the total humid forest area in the Congo Basin, its massive CH4 flux renders the Congo Basin forests a source, releasing a forest type weighted average of 8.38 [0.89, 25.03] kg CH4-C ha−1 yr−1 to the atmosphere if we assume our sites to be representative of their respective forest types (weighted flux based on forest coverage28: 90.6% lowland, 6.8% swamp, 2.6% montane). The result that Congo Basin’s forests might be on average a net source of CH4, even though 93% of its area was identified as a sink (at least when considering forest type as the sole indicator), highlights the source strength of the swamp CH4 flux relative to the uptake measured in the other forest types. We would like to stress, however, that these extrapolation estimates should not be overinterpreted, as higher spatiotemporal data coverage is needed to draw basin-wide conclusions as to whether the Congo Basin’s forests act as a net sink or source for CH4—especially considering yet unaccounted but potentially sizeable sources such as CH4 fluxes from swamp forest tree stems29.

Congo Basin soil N2O fluxes ranged from −0.22 to 15.46 nmol m−2 s−1 across all forest types and were predominantly a source to the atmosphere (Figs. 2c and S4). We determined geometric mean [95% CIs] N2O fluxes of 0.93 [0.6, 1.29] kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 from montane, 3.5 [1.85, 6.34] kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 from non-inundated swamp forests, −0.19 [−0.75, 0.76] kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 from inundated swamp forests, and 1.56 [1.25, 1.93] kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 from lowland forests. Our estimated basin-wide forest type weighted average of 1.55 [1.19, 2.02] kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 was 32% higher compared to 1.17 kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 reported for Cameroonian tropical forest15 but 12–61% lower than the global averages for tropical forests based on a meta-analysis (2.822; 2.030 kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1) or modeling efforts (1.76–4 kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1)5.

Isotopic evidence of N2O reduction

To further investigate the mechanisms behind the unexpectedly low N2O emission, we analyzed the isotopic composition (δ18O and δ15N) of emitted N2O during the intensive campaigns at all forest locations (Table S1). Isotopes of N in N2O exhibited an average site preference value of 7.22 ± 8.5‰, indicative of denitrification as the major driver for N2O production31,32. We further compared δ18O and bulk δ15N of N2O from this study to previous terrestrial (n = 4) and riverine (n = 1) tropical forest studies using an isotope mapping approach (Fig. 3)33. This mapping approach confirmed denitrification as the dominant N2O production process, with all delta values falling close to an empirical reduction vector with a ratio of 2.4 (δ18O/δ15N). In other words, δ18O and δ15N co-vary during reduction of N2O to N2, which isotopically enriches the remaining soil N2O33,34. Apart from one study in the Amazonas35, all tropical forest sites have so far shown relatively high enrichment of both 18O and 15N, indicating N2O reduction as a dominant process across the tropics. It should be noted that during denitrification (given limited NO3− supply), a concurrent enrichment of 15N and 18O also occurs in the NO3− substrate pool36, resulting in a strong correlation of 18O-NO3− and 15N-NO3−, which in turn directly translates to an increase in δ18O-N2O and δ15N-N2O37. Consequently, high denitrification rates ultimately result in enriched N2O, either through substrate enrichment and/or through reduction to N2. With respect to tropical ecosystems, recent work from Costa Rica38 suggest also weak gaseous N losses as N2O and attributed the discrepancy between high N inputs and low outputs to N2 losses. Similarly, N budgeting from tropical forest watersheds using natural abundance stable isotopes of NO3− assigned 24–53% of the total gaseous N lost to denitrification with a high proportion of N239. Analogously high N2 and comparatively low N2O losses during denitrification were further suggested for tropical forests using a similar approach40 and modeled generally for humid tropical forest soils and hydrological flow paths in the range of >45% of total watershed N losses41. Overall, our isotopic data suggest that the proportion of N2O reduction to N2 might be one driving factor behind the 10–60% lower N2O fluxes observed in the forests of the Congo Basin compared to the global tropical forest average.

Isotope map of δ18O vs. δ15N adapted from Koba et al. (2009)33 of tropical forest soil N2O fluxes35,79,80,81 and riverine N2O82 derived from literature and this study with overall site medians given in ‰. Note, values from Koehler et al. (2012) and Pérez et al. (2000) are fully or partly from soil pore air measurements. Arrow indicates empirical reduction vector with the ratio of 2.4 (ε18O/ε15N)33. Rectangles depict literature ranges of δ18O vs. δ15N for the N2O production from nitrification and denitrification. Asterisk (*) represents isotope composition of tropospheric air as reference44. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Linking terrestrial (vertical) and aquatic (lateral) N2O and CH4

Our estimates of terrestrial N2O fluxes and their isotopic signature, indicative of reduction to N2, are corroborated by low dissolved N2O in headwater streams of the catchments draining our study sites in the forests (Fig. 2d). We found low riverine dissolved N2O concentrations of 0.46 ± 0.06 µg N L−1 (montane), 0.40 ± 0.06 µg N L−1 (lowland), and 0.21 ± 1.16 µg N L−1 (swamp) with a δ15N signature of 6.0 ± 3.1‰ (montane, lowland), indicating near equilibration with the atmosphere (N2Oeq = 0.36 µg N L−1 42; δ15Neq = 7.3‰43,44). This suggests that negligible quantities of N2O are dissolved in soil pore water and laterally exported to aquatic systems and supports the assumption that exclusive measurement of vertical fluxes from soils does not underestimate total landscape N2O fluxes. At the same time, the near-atmospheric N2O concentrations and isotopic signatures found in the stream waters also rule out hydrological mineral N loss, which may be emitted further downstream as well. Our headwater stream results correspond well with earlier studies that also observed N2O in surface waters of the Congo Basin to be nearly in equilibrium with the atmosphere26,45,46,47 or even undersaturated relative to the atmosphere in rivers draining swamp forests, with in-stream N2O reduction as the suggested mechanism45,47.

In contrast to N2O, headwater streams showed CH4 supersaturation at all sites (0.72 ± 0.33 µg C L−1 (montane), 1.74 ± 1.05 µg C L−1 (lowland), and 190 ± 373 µg C L−1 (swamp)) relative to atmospheric equilibrium (0.03 µg C L−1). Moreover, CH4 concentrations exhibited relatively low seasonal variability (Fig. 2b, Fig. S5a) but high spatial heterogeneity (Fig. S5a). Supersaturation of riverine CH4 is commonly found in the Congo Basin26,45,47 with subsequent outgassing partly offsetting terrestrial uptake. Our negative soil CH4 fluxes at the lowland and montane site together with supersaturated dissolved CH4 results suggest that aquatic CH4 production is decoupled from these terrestrial ecosystems and likely occurs within benthic sediments and/or riparian zones of the streams themselves. However, high hydrological connectivity was indicated at the swamp forest site where high soil to atmosphere CH4 fluxes from the inundated forest were corroborated by highly supersaturated dissolved CH4 concentrations found in riverine samples (190 ± 373 µg C L−1). Such high fluvial-wetland connectivity driving variations of riverine greenhouse gas concentrations has been recently shown for the entire Congolese Cuvette Centrale based on data from 10 expeditions across the Congo River network47.

It is important to note that in-stream gas concentrations are a result of a multitude of simultaneous processes and drivers (i.e. gas solubility, aquatic-terrestrial connectivity, inputs from surface water/groundwater, in-stream metabolism, stream chemistry, stream morphology, gas transfer velocity) which render CH4 and N2O highly variable at low spatiotemporal scales. Thus, although the in-stream concentrations we observed are consistent with minimal vertical N2O losses, decoupled CH4 fluxes in the lowland and montane, and strong hydrologic connectivity in the swamp forest, they do not necessarily reflect lateral soil export from the location in the catchment where soil–atmosphere fluxes were measured. We, therefore, caution that such terrestrial–aquatic linkage is likely associated with high uncertainty.

Towards a more nuanced tropical paradigm

Classically, tropical forests are believed to be N-rich systems in which supply exceeds biological demand because high rates of inorganic losses to the atmosphere and aquatic systems have been observed. This has led to the conclusion that tropical forests are ubiquitously strong sources of N2O (Hedin et al., 200948 and references therein). However, recent studies from the Congo Basin49,50 and other data on denitrification losses from the Neotropics39 challenge the paradigm that tropical forests are universal hotspots of N2O emissions. Instead, these studies rather indicate that a fraction of gaseous N losses occur as N2 emissions. Our results align with these recent findings and suggest that the Congo Basin is not a hotspot for N2O and releases less N2O compared to other tropical forests. Contrary to reduced N2O emissions, the Congo Basin shows a higher net CH4 uptake from forest soils when related to other non-inundated tropical forests. However, the sizeable CH4 flux of the swamp forests together with highly concentrated riverine CH4 concentrations indicate that swamp forests may offset the areally dominant CH4 sink of the Congo Basin despite swamp forest covering only 7% of the humid forest and flooded areas covering only 10 % of the total basin area51. This is an especially important finding given that inland waters are increasingly recognized as important greenhouse gas outlets within the terrestrial landscape26,52,53,54 with recent data suggesting that Congo Basin’s inland waters might emit similar or even greater amounts of carbon per area than the Amazon Basin55.

Generally, there are strong links between methanotrophic activity and the nitrogen cycle56 with stimulatory effects on CH4 uptake in response to nitrogen addition (<100 kg N ha−1 yr−1) according to a meta-analysis on non-wetland soils57. In light of the recently discovered high fire derived N deposition on Central African forests10 such N inputs could be one of the driving factors of the observed high biological CH4 oxidation in lowland and montane forest soils. The rapidly expanding database of genome sequences will help to unravel the biogeochemical link of CH4 and N2O, which has already led to interesting new discoveries such as bacteria capable of both CH4 oxidation and denitrification-mediated N2 production58. It is possible that such microbial groups might play a role in the soils of Congo’s tropical forests given both the high methanotrophic activity and signatures of complete denitrification identified in this study.

Overall, our measurements add to key studies on African tropical forests6,7,8,9,59, highlight the role of the Congo Basin as a global greenhouse gas buffering reservoir, and stress once again its value in global conservation efforts. Lastly, we show that on-ground observational efforts remain imperative for improved quantification of regional and global greenhouse gas balances. While dense greenhouse gas observational infrastructures have been established at continental scales (e.g. ICOS, NEON) to feed global databases (e.g. FLUXNET60), ground-based observations from the African continent are still severely underrepresented61,62,63 as can be seen from poor sub-Saharan coverage of soil–atmosphere specific greenhouse gas flux databases (COSORE64, Global N2O Database65). As a consequence, the contribution of African tropical forests (and African ecosystems in general) to global atmospheric exchange of CH4 and N2O remains subject to high uncertainty, despite the fact that CH4 and N2O emissions are thought to shift the African continent as a whole to a net source of greenhouse gases62. Our study is the first step towards addressing this uncertainty and highlights both the variation and nuanced nature of these key biogeochemical fluxes.

Methods

Sites

All field sites are located in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Three long-term observation core sites were established, one in the montane forest of the Albertine Rift (Kahuzi-Biéga National Park, South Kivu province), one in a pristine lowland forest 30 km south of the city of Kisangani (Yoko Forest Reserve, Tshopo province), and one in a seasonally flooded swamp forest 7 km away from the town of Mbandaka (Jardin Botanique d’Eala, Équateur province). The montane forest climate is classified as Cfb-type following the Köppen-Geiger classification, with Allophylus kivuensis, Maesa lanceolata, Lindackeria kivuensis, Bridelia micranta, and Dombea goetzenii as the main occurring tree species at this altitude66. The montane forest soils are classified as Umbric Ferrasols with a sandy loam texture67. The lowland forest climate is classified as Af-type at the Köppen–Geiger classification with highly weathered, nutrient-poor, acidic, and loamy sand textured Xanthic Ferrasol soils68. The main occurring species at the core lowland forest site are Scorodophloeus zenkeri, Julbernardia seretii (De Wild.) Troupin, Prioria oxyphylla (Harms) Breteler, Cynometra hankei, Tessmannia africana with monodominant forest patches of Gilbertiodendron dewevrei (De Wild.) J. Léonard69. The seasonally inundated swamp forest core site investigated was located within a botanical garden operated by the Institute Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN). The botanical garden comprises 371 ha of land consisting of 35% dense swamp forest, 14% forest on firm ground, 32% open forest, and the remaining area consisting of secondary forest, grassland, and deforested land of which 189 ha are protected forest area. The main tree species found at the swamp forest site are Hevea brasiliensis, Ouratea arnoldiana, Pentaclethra eetveldeana, Strombosia tetandra, and Daniella pynaertii. The soil at the site was characterized as Eutric Gleysols with a sandy loam texture.

Before the establishment of the long-term observation core sites, two additional lowland forest sites were initially scouted and sampled; one at the Yangambi Biosphere Reserve (Tshopo province) and one in the protected forests surrounding the town of Djolu (Maringa-Lopori-Wamba Landscape, Tshuapa province). Table S1 gives detailed information on location, soil type, sampling duration, replication, periodicity, and the total number of fluxes measured at each site.

N2O and CH4 soil fluxes and N2O isotopic composition

Soil N2O and CH4 fluxes were measured using the non-steady-state, static chamber method24 with chamber dimensions of d = 30 cm and h = 30 cm. For the majority of the measurement periods five polyvinylchloride chambers, equipped with vent tube, thermocouple, and sampling port, were permanently installed at each site from which flasks were sampled once a week or once every two weeks and during the intensive campaigns at least once per day. Within the entire project time frame, chambers were occasionally relocated within the sites, with the core lowland site (Yoko Forest Reserve) having 16 different chamber locations, the core montane site (Kahuzi-Biéga National Park) 12 different chamber locations, and the core swamp forest site (Jardin Botanique d’Eala) 6 different chamber locations. Those chambers affected by seasonal flooding at the swamp forest site were measured for as long as possible and replaced by floating chamber (V = 17 L) measurements during complete inundation. During the wet season, boardwalks were installed to sample forest water away from the flood water edge whereas during the dry season, the receding water was followed and the floating chamber operated from the edge. We separated data between chamber measurements taken under visibly inundated and non-inundated conditions. To measure the gas flux, chambers were closed over the duration of one hour and headspace air samples were taken at four evenly spread time points (t1 = 0, t2 = 20, t3 = 40, t4 = 60 min) using a disposable airtight plastic syringe which was connected to the chamber via a three-way Luer-lock valve, connecting syringe, chamber, and needle. After connecting the syringe to the sampling port, the plunger was moved a couple of times to ensure air mixing inside the chamber before actual sampling. At each time interval pre-evacuated exetainers (12 mL; Labco, UK), sealed with an additional silicon layer (Dow Corning 734, Dow Silicones Corporation, USA), were filled with 20 mL headspace air. The resulting overpressure prevents air ingress due to temperature and pressure changes potentially occurring during transport. The obtained relationship between time and concentration increase for each chamber measurement was then used to infer the individual flux rates using the ideal gas law PV = \(n\)RT:

with \(n\) moles of gas [mol], P partial pressure of trace gas [atm µmol mol−1], V chamber volume [L], R gas constant 0.08206 [L atm K−1 mol−1], T headspace temperature [K], F flux of gas [µmol m−2 s−1], \(\frac{\Delta n}{\Delta t}\) rate of change in concentration [mol s−1], and S surface area enclosed by chamber [m2]. Headspace temperature was measured at each sampling interval using thermocouples attached to each chamber (Type T, Omega Engineering, Stamford, USA). The coefficient of determination (R2) of the linear regression of \(\frac{\Delta n}{\Delta t}\) was higher than 0.95 for 76% of the N2O data and 75% of the CH4 data (Fig. S7). Note, low R2 values were mostly associated with low or zero fluxes. Thus, to not bias the data towards high fluxes, none of the data has been discarded from the analysis. Signs follow the micrometeorological convention with negative numbers denoting a flux from the atmosphere to the biosphere. All gas samples were shipped to Switzerland and analyzed at ETH Zurich for N2O and CH4 mole fraction using gas chromatography (456-GC, Scion Instruments, UK) with a suite of standards covering the expected range of concentrations.

For the majority of flux measurements, volumetric water content (ECH2O-EC5, Meter Environment, Pullman, USA) and soil temperature (thermocouple Type T, Omega Engineering, Stamford, USA) data from 30 cm depth were available (Fig. S2). Volumetric water content was converted to WFPS using soil bulk density.

Moreover, the intramolecular distribution of 15N within the linear N2O molecule (15N site preference) was analyzed, together with the bulk 15N content (δ15N) and 18O content (δ18O) of N2O, to assess whether N2O production was dominated by either nitrification or denitrification. To determine 15N site preference, δ15N and δ18O of surface flux N2O additional samples were taken during the high-frequency sampling campaigns at all sites (Table S1) and the data was analyzed according to a two-source mixing model approach as described in Krüger et al. (2001)70. In brief, two additional 180 mL gas samples were collected during gas flux measurements with a 60 mL syringe immediately after chamber closure (t1 = 0 min) and shortly before chamber opening (t4 = 60 min). The gas samples were then stored in pre-evacuated 110 mL serum crimp vials and transported back to Zurich, where the isotopic composition of N2O was measured using a gas preparation unit (Trace Gas, Elementar, Manchester, UK) coupled to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS, IsoPrime100, Elementar, Manchester, UK). The gas preparation unit was modified with an additional chemical trap (0.5 inches diameter stainless steel), located immediately downstream from the autosampler to pre-condition samples. This pre-trap was filled with NaOH, Mg(ClO4)2, and activated carbon in the direction of flow and was designed as a first step to scrub CO2, H2O, CO, and VOCs, which otherwise would cause mass interference during measurements. All 15N/14N and 18O/16O sample ratios are reported relative to air-n2 and vsmow, respectively, using the δ notation. For a detailed description of the analytical procedure see Verhoeven et al. (2019)71. Since the accuracy of δ15N, and δ18O resulting from the mixing model approach highly depends on the concentration difference between start and end of the measurement, data with ∆N2O < 31ppb was discarded from further analysis72.

N2O and CH4 concentrations and N2O isotopic composition dissolved in headwater streams

During one hydrological year samples of headwater streams, which drained the catchments of the core sites for soil–atmosphere flux measurements, were taken fortnightly using the headspace equilibration technique (03/2018–03/2019 montane, lowland; 11/2019–11/2020 swamp). Further, to assess spatial variability, several different headwater streams from other lowland and montane catchments close to the core sites were additionally sampled using also the headspace equilibration technique—once in the wet season (03/2018) and once in the dry season (09/2018) (Table S1, Figs. S5 and S6). Water samples were taken in the middle of the stream using a 12 mL plastic syringe and 6 mL of air bubble-free water injected into N2-pre-flushed Labco exetainers. After the initial injection of 3 mL, a vent needle was inserted, and the remaining 3 mL of water was filled into the vial. Prior to capping and flushing with ultrapure N2 (Alphagaz II, Carbagas, Switzerland), the 12 mL Labco exetainer was conditioned with 50 μL of 50% (w/v) ZnCl2 to suppress microbial activity after sample injection73. Samples were transported back to Zurich and headspace was analyzed for N2O and CH4. Final dissolved gas concentrations were calculated according to Henry’s law with a detailed protocol provided in the supplement.

Similar to the preparation of the Labco exetainers, 110 mL serum crimp vials used for the isotopic characterization of dissolved N2O were pre-flushed with ultrapure N2 and pre-treated with 200 µL of 50% (w/v) ZnCl2 to stop microbial activity after sample injection. Once a month, during the same year as dissolved gases were taken, 20 mL of riverine water was injected into the pre-flushed 110 mL serum vials (only montane and lowland streams). Back in the lab, vial headspace was analyzed for N2O isotopic composition using the same IRMS as described above. 20 mL water in 110 mL serum crimp vials allowed direct headspace measurements without the needle of the autosampler entering the water when injected into the vial. The IRMS system operates with a double-holed needle, flushing the entire sample from the headspace using helium as carrier gas. Since samples were measured in the actual gas phase, δ18O and δ15N values of the dissolved N2O phase were calculated using the equilibrium fractionation factors given in Thuss et al. (2014)43:

with αeq = 0.99925 for 15N and 0.99894 for 18O and Rheadspace = (δheadspace/1000 + 1)·Rreference. Corresponding reference values (vsmow for δ18O; air-n2 for δ15N) were taken from Werner ad Brand (2001)74.

Statistics

We used the long-term datasets from Kahuzi-Biéga National Park, Yoko Forest Reserve, and Jardin Botanique d’Eala to assess intra-site (between chamber) and intra-annual variability in the N2O and CH4 fluxes. For between chamber variance, we calculated the arithmetic average of the fluxes per chamber over the monitoring periods (see Supplementary Table S2) and then calculated the variance, and subsequently also the standard deviation and coefficient of variance over those ‘chamber averages’ per site. For the intra-annual variability, an arithmetic average was calculated per week per site (using the different chamber flux estimates). Subsequently, the variance over those weekly site fluxes was calculated, along with the standard deviation and coefficient of variation per site.

We estimated median fluxes (from a highly positively skewed distribution of fluxes) for both N2O and CH4. This was done by fitting linear mixed effect models per forest type (lowland, montane, and swamp forest) with log-transformed fluxes as a response variable, without fixed effects, and with chamber ID (nested within the plot) and sampling date as a random intercept. The effect estimates for the intercept of the different models, corroborating with a ‘best estimator’ for the fluxes in the different forest types, were exponentiated for the estimation of median fluxes per forest type. Finally, we fitted another set of linear mixed effect models to quantify the effects of recorded field temperature and water-filled pore space on the fluxes. For this, different models were fitted for the three different forest types (lowland, montane, and swamp). After log-transforming the response variables, i.e. the fluxes of, respectively, N2O and CH4, linear mixed effect models were fitted using temperature and water-filled pore space as fixed effects, and chamber ID as a random intercept. The estimated fixed effects were extracted from the models and recalculated to the % change that both individual effects cause in the response data by (exp(effect)−1)*100. Note, for visualization purposes, collected soil and riverine data were pooled into weekly classes irrespective of year.

All statistical analyses were carried out using the R software75, mixed effect models were fitted using the lme4 package76, and R2 values for mixed effect models were calculated following Nakagawa and Schielzeth (2013)77.

Data availability

The core datasets generated during the current study have been deposited in the Zenodo repository [https://zenodo.org/record/5764853#.Ya-jJlPTXOR] and are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Dalal, R. C. & Allen, D. E. Turner review no. 18. Greenhouse gas fluxes from natural ecosystems. Aust. J. Bot. 56, 369–407 (2008).

Tian, H. et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 586, 248–256 (2020).

Dutaur, L. & Verchot, L. V. A global inventory of the soil CH4 sink. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 21, 1–9 (2007).

Davidson, E. A. et al. Recuperation of nitrogen cycling in Amazonian forests following agricultural abandonment. Nature 447, 995–998 (2007).

Bai, E., Houlton, B. Z. & Wang, Y. P. Isotopic identification of nitrogen hotspots across natural terrestrial ecosystems. Biogeosciences 9, 3287–3304 (2012).

Slik, J. W. F. et al. An estimate of the number of tropical tree species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7472–7477 (2015).

Parmentier, I. et al. The odd man out? Might climate explain the lower tree α-diversity of African rain forests relative to Amazonian rain forests? J. Ecol. 95, 1058–1071 (2007).

Lewis, S. L. et al. Above-ground biomass and structure of 260 African tropical forests. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 368, 1–14 (2013).

Hubau, W. et al. Asynchronous carbon sink saturation in African and Amazonian tropical forests. Nature 579, 80–87 (2020).

Bauters, M. et al. High fire-derived nitrogen deposition on central African forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 549–554 (2018).

Veldkamp, E., Koehler, B. & Corre, M. D. Indications of nitrogen-limited methane uptake in tropical forest soils. Biogeosciences 10, 5367–5379 (2013).

Tathy, J. et al. Methane emission from flooded forest in Central Africa. J. Geophys. Res. 97, 6159–6168 (1992).

Serca, D., Delmas, R., Jambert, C. & Labroue, L. Emissions of nitrogen oxides from equatorial rainforest in central Africa—origin and regulation of NO emission from soils. Tellus Ser. B-Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 46, 243–254 (1994).

Macdonald, J. A., Eggleton, P., Bignell, D. E., Forzi, F. & Fowler, D. Methane emission by termites and oxidation by soils, across a forest disturbance gradient in the Mbalmayo Forest Reserve, Cameroon. Glob. Chang. Biol 4, 409–418 (1998).

Iddris, N. A. -A., Corre, M., Yemefack, M., van Straaten, O. & Veldkamp, E. Stem and soil nitrous oxide fluxes from rainforest and cacao agroforest on highly weathered soils in the Congo Basin. Biogeosciences 17, 5377–5397 (2020).

Tchiofo Lontsi, R., Corre, M. D., Iddris, N. A. & Veldkamp, E. Soil greenhouse gas fluxes following conventional selective and reduced-impact logging in a Congo Basin rainforest. Biogeochemistry 151, 153–170 (2020).

Werner, C., Kiese, R. & Butterbach-Bahl, K. Soil–atmosphere exchange of N2O, CH4, and CO2 and controlling environmental factors for tropical rain forest sites in western Kenya. J. Geophys. Res. 112, D03308 (2007).

Wanyama, I. et al. Management intensity controls soil N2O fluxes in an Afromontane ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 624, 769–780 (2018).

Wanyama, I. et al. Soil carbon dioxide and methane fluxes from forests and other land use types in an African tropical montane region. Biogeochemistry 143, 171–190 (2019).

Arias-Navarro, C. et al. Quantifying the contribution of land use to N2O, NO and CO2 fluxes in a montane forest ecosystem of Kenya. Biogeochemistry 134, 95–114 (2017).

Gütlein, A., Gerschlauer, F., Kikoti, I. & Kiese, R. Impacts of climate and land use on N2O and CH4 fluxes from tropical ecosystems in the Mt. Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 1239–1255 (2018).

Castaldi, S., Bertolini, T., Valente, A., Chiti, T. & Valentini, R. Nitrous oxide emissions from soil of an African rain forest in Ghana. Biogeosciences 9, 16565–16588 (2013).

Tamale, J. et al. Nutrient limitations regulate soil greenhouse gas fluxes from tropical forests: evidence from an ecosystem-scale nutrient manipulation experiment in Uganda. SOIL 7, 433–451 (2021).

Hutchinson, G. L. & Mosier, A. R. Improved soil cover method for field measurement of nitrous oxide fluxes. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 45, 311 (1981).

Butman, D. & Raymond, P. A. Significant efflux of carbon dioxide from streams and rivers in the United States. Nat. Geosci. 4, 839–842 (2011).

Borges, A. V. et al. Globally significant greenhouse-gas emissions from African inland waters. Nat. Geosci. 8, 637–642 (2015).

Johnson, M. S. et al. CO2 efflux from Amazonian headwater streams represents a significant fate for deep soil respiration. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, 1–5 (2008).

Verhegghen, A., Mayaux, P., De Wasseige, C. & Defourny, P. Mapping Congo Basin vegetation types from 300 m and 1 km multi-sensor time series for carbon stocks and forest areas estimation. Biogeosciences 9, 5061–5079 (2012).

Pangala, S. R. et al. Large emissions from floodplain trees close the Amazon methane budget. Nature 552, 230–234 (2017).

Van Lent, J., Hergoualc’H, K. & Verchot, L. V. Reviews and syntheses: soil N2O and NO emissions from land use and land-use change in the tropics and subtropics: a meta-analysis. Biogeosciences 12, 7299–7313 (2015).

Decock, C. & Six, J. How reliable is the intramolecular distribution of 15N in N2O to source partition N2O emitted from soil? Soil Biol. Biochem. 65, 114–127 (2013).

Yu, L. et al. What can we learn from N2O isotope data? Analytics, processes and modelling. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 34, 1–14 (2020).

Koba, K. et al. Biogeochemistry of nitrous oxide in groundwater in a forested ecosystem elucidated by nitrous oxide isotopomer measurements. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 3115–3133 (2009).

Ostrom, N. E. et al. Isotopologue effects during N2O reduction in soils and in pure cultures of denitrifiers. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 112, 1–12 (2007).

Park, S. et al. Can N2O stable isotopes and isotopomers be useful tools to characterize sources and microbial pathways of N2O production and consumption in tropical soils? Global Biogeochem. Cycles 25, 1–16 (2011).

Aravena, R. & Robertson, W. D. Use of multiple isotope tracers to evaluate denitrification in ground water: study of nitrate from a large-flux septic system plume. Ground Water 36, 975–982 (1998).

Mengis, M. et al. Multiple geochemical and isotopic approaches for assessing ground water NO3- elimination in a riparian zone. Ground Water 37, (1999).

Soper, F. M. et al. Modest gaseous nitrogen losses point to conservative nitrogen cycling in a lowland tropical forest watershed. Ecosystems 1–12 (2017) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-017-0193-1

Houlton, B. Z., Sigman, D. M. & Hedin, L. O. Isotopic evidence for large gaseous nitrogen losses from tropical rainforests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8745–8750 (2006).

Fang, Y. et al. Microbial denitrification dominates nitrate losses from forest ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 1470–1474 (2015).

Brookshire, E. N. J., Gerber, S., Greene, W., Jones, R. T. & Thomas, S. A. Global bounds on nitrogen gas emissions from humid tropical forests. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 2502–2510 (2017).

Hama-Aziz, Z. Q., Hiscock, K. M. & Cooper, R. J. Dissolved nitrous oxide (N2O) dynamics in agricultural field drains and headwater streams in an intensive arable catchment. Hydrol. Process. 31, 1371–1381 (2017).

Thuss, S. J., Venkiteswaran, J. J. & Schiff, S. L. Proper interpretation of dissolved nitrous oxide isotopes, production pathways, and emissions requires a modelling approach. PLoS ONE 9, e90641 (2014).

Harris, E. et al. Tracking nitrous oxide emission processes at a suburban site with semicontinuous, in situ measurements of isotopic composition. J. Geophys. Res. 122, 1850–1870 (2017).

Upstill-Goddard, R. C. et al. The riverine source of CH4 and N2O from the Republic of Congo, western Congo Basin. Biogeosciences 14, 2267–2281 (2017).

Bouillon, S. et al. Organic matter sources, fluxes and greenhouse gas exchange in the Oubangui River (Congo River basin). Biogeosciences 9, 2045–2062 (2012).

Borges, A. V. et al. Variations in dissolved greenhouse gases (CO2, CH4, N2O) in the Congo River network overwhelmingly driven by fluvial-wetland connectivity. Biogeosciences 16, 3801–3834 (2019).

Hedin, L. O., Brookshire, E. N. J., Menge, D. N. L. & Barron, A. R. The nitrogen paradox in tropical forest ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 40, 613–635 (2009).

Gallarotti, N. et al. In-depth analysis of N2O fluxes in tropical forest soils of the Congo Basin combining isotope and functional gene analysis. ISME J. 15, 3357–3374 (2021).

Bauters, M. et al. Contrasting nitrogen fluxes in African tropical forests of the Congo Basin. Ecol. Monogr. 89, 1–17 (2019).

Bwangoy, J. R. B., Hansen, M. C., Roy, D. P., De Grandi, G. & Justice, C. O. Wetland mapping in the Congo Basin using optical and radar remotely sensed data and derived topographical indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 73–86 (2010).

Bastviken, D., Tranvik, L. J., Downing, J. A., Crill, P. M. & Enrich-Prast, A. Freshwater methane emissions offset the continental carbon sink. Science (80-.) 331, 50 (2011).

Drake, T. W., Raymond, P. A. & Spencer, R. G. M. Terrestrial carbon inputs to inland waters: a current synthesis of estimates and uncertainty. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 3, 32–142 (2017).

Raymond, P. A. et al. Global carbon dioxide emissions from inland waters. Nature 503, 355–359 (2013).

Alsdorf, D. et al. Opportunities for hydrologic research in the Congo Basin. Rev. Geophys. 54, 378–409 (2016).

Bodelier, P. L. E. & Steenbergh, A. K. Interactions between methane and the nitrogen cycle in light of climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 9–10, 26–36 (2014).

Aronson, E. L. & Helliker, B. R. Methane flux in non-wetland soils in response to nitrogen addition: a meta-analysis. Ecology 91, 3242–3251 (2010).

Dam, B., Dam, S., Blom, J. & Liesack, W. Genome analysis coupled with physiological studies reveals a diverse nitrogen metabolism in Methylocystis sp. strain SC2. PLoS ONE 8, (2013).

Dargie, G. C. et al. Age, extent and carbon storage of the central Congo Basin peatland complex. Nature 542, 86–90 (2017).

Baldocchi, D. et al. FLUXNET: a new tool to study the temporal and spatial variability of ecosystem-scale carbon dioxide, water vapor, and energy flux densities. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 82, 2415–2434 (2001).

Kim, D. G., Thomas, A. D., Pelster, D., Rosenstock, T. S. & Sanz-Cobena, A. Greenhouse gas emissions from natural ecosystems and agricultural lands in sub-Saharan Africa: Synthesis of available data and suggestions for further research. Biogeosciences 13, 4789–4809 (2016).

Valentini, R. et al. A full greenhouse gases budget of Africa: Synthesis, uncertainties, and vulnerabilities. Biogeosciences 11, 381–407 (2014).

López-Ballesteros, A. et al. Towards a feasible and representative pan-African research infrastructure network for GHG observations. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 085003 (2018).

Bond-Lamberty, B. et al. COSORE: a community database for continuous soil respiration and other soil–atmosphere greenhouse gas flux data. Glob. Chang. Biol 26, 7268–7283 (2020).

Dorich, C. D. et al. Improving N2O emission estimates with the global N2O database. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 47, 13–20 (2020).

Imani, G. et al. Woody vegetation groups and diversity along the altitudinal gradient in mountain forest: case study of Kahuzi-Biega National Park and its surroundings, RD Congo. J. Biodivers. Environ. Sci. 8, 134–150 (2016).

Baumgartner, S. et al. Seasonality, drivers, and isotopic composition of soil CO2 fluxes from tropical forests of the Congo Basin. Biogeosciences 17, 6207–6218 (2020).

Van Ranst, E., Baert, G., Ngongo, M. & Mafuka, P. Carte pédologique de Yangambi, planchette 2: Yangambi, échelle 1:50.000. UGent; Hogent; UNILU; UNIKIN (2010).

Cassart, B., Angbonga Basia, A., Titeux, H., Andivia, E. & Ponette, Q. Contrasting patterns of carbon sequestration between Gilbertiodendron dewevrei monodominant forests and Scorodophloeus zenkeri mixed forests in the Central Congo basin. Plant Soil 414, 309–326 (2017).

Krüger, M., Frenzel, P. & Conrad, R. Microbial processes influencing methane emission from rice fields. Glob. Chang. Biol. 4, 49–63 (2001).

Verhoeven, E. et al. Early season N2O emissions under variable water management in rice systems: source-partitioning emissions using isotope ratios along a depth profile. Biogeosciences 16, 383–408 (2019).

Harris, S. et al. N2O isotopocule measurements using laser spectroscopy: analyzer characterization and intercomparison. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 13, 2797–2831 (2020).

Verhoeven, E. et al. Nitrification and coupled nitrification-denitrification at shallow depths are responsible for early season N2O emissions under alternate wetting and drying management in an Italian rice paddy system. Soil Biol. Biochem. 120, 58–69 (2018).

Werner, R. A. & Brand, W. A. Referencing strategies and techniques in stable isotope ratio analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 15, 501–519 (2001).

R core Team. R.: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. M. & Walker, S. C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, (2015).

Nakagawa, S. & Schielzeth, H. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 133–142 (2013).

Buchhorn, M. et al. Copernicus global land service: land cover 100 m: collection 3: epoch 2019: Globe (version V3.0.1) [Data set]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3939050 (2020).

Kim, K.-R. & Craig, H. Nitrogen-15 and oxygen-18 characteristics of nitrous oxide: a global perspective. Science (80-.) 262, 1855–1857 (1993).

Perez, T. Isotopic variability of N2O emissions from tropical forest soils. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 14, 525–535 (2000).

Koehler, B. et al. An in-depth look into a tropical lowland forest soil: Nitrogen-addition effects on the contents of N2O, CO2 and CH4 and N2O isotopic signatures down to 2-m depth. Biogeochemistry 111, 695–713 (2012).

Boontanon, N., Ueda, S., Kanatharana, P. & Wada, E. Intramolecular stable isotope ratios of N2O in the tropical swamp forest in Thailand. Naturwissenschaften 87, 188–192 (2000).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the park guards of the Institute Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN) for support during field campaigns. We further acknowledge the support by the Institut National des Etudes et Recherches Agronomique (INERA) during our fieldwork in the Yangambi Biosphere Reserve, and the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) during our work in the Maringa-Lopori-Wamba landscape. M. Barthel was funded by two Swiss National Foundation exchange grants (IZSEZ0_186376; IZK0Z2_170806). In addition, M. Barthel, T.W.D., and J.S. were supported through ETH core funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Barthel and J.S. conceived the study. M. Barthel, M. Bauters, S.B., N.G., N.D., L.S., T.W.D., I.A.M., N.M.B., C.E.M., D.M.M., and J.K.M. conducted the fieldwork. J.M. and B.W. provided reference gases for N2O isotope analysis. C.B., F.M.M., L.C.N., G.L.E., R.G.M.S., P.B., G.B., J.Z.M., B.V., M.B.R., K.V.O., and J.S. facilitated local collaborations. M. Bauters did the statistical data analysis. T.W.D., M. Bauters, S.B., and J.S. helped M. Barthel with the drafting of the manuscript outline. All co-authors substantively revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barthel, M., Bauters, M., Baumgartner, S. et al. Low N2O and variable CH4 fluxes from tropical forest soils of the Congo Basin. Nat Commun 13, 330 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-27978-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-27978-6

This article is cited by

-

Substantial Organic and Particulate Nitrogen and Phosphorus Export from Geomorphologically Stable African Tropical Forest Landscapes

Ecosystems (2023)

-

Greenhouse gas dynamics in tropical montane streams of Puerto Rico and the role of watershed lithology

Biogeochemistry (2023)

-

Congo Basin greenhouse gas emissions differ from tropical forest models

Nature Africa (2022)

-

Global distribution and climate sensitivity of the tropical montane forest nitrogen cycle

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Warming and redistribution of nitrogen inputs drive an increase in terrestrial nitrous oxide emission factor

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.