Abstract

In a radiative Auger process, optical decay leaves other carriers in excited states, resulting in weak red-shifted satellite peaks in the emission spectrum. The appearance of radiative Auger in the emission directly leads to the question if the process can be inverted: simultaneous photon absorption and electronic demotion. However, excitation of the radiative Auger transition has not been shown, neither on atoms nor on solid-state quantum emitters. Here, we demonstrate the optical driving of the radiative Auger transition, linking few-body Coulomb interactions and quantum optics. We perform our experiments on a trion in a semiconductor quantum dot, where the radiative Auger and the fundamental transition form a Λ-system. On driving both transitions simultaneously, we observe a reduction of the fluorescence signal by up to 70%. Our results suggest the possibility of turning resonance fluorescence on and off using radiative Auger as well as THz spectroscopy with optics close to the visible regime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-radiative Auger processes have been observed in both atoms1 and solid-state quantum emitters2,3. They play an important role in determining the efficiency of semiconductor light-emitting diodes and lasers4. In the non-radiative Auger process, one electron reduces its energy by transferring it to a second electron that is promoted to a high-energy state. In the radiative Auger process (shake-up), in contrast, one electron makes an optical decay, creating a photon. Part of the photon energy is transferred to a second electron such that the radiative Auger emission is red-shifted with respect to the main emission line. Both radiative and non-radiative Auger processes arise as a consequence of the Coulomb interactions between electrons in close proximity5,6,7. Non-radiative Auger is a purely Coulomb scattering process. In contrast, radiative Auger involves both Coulomb scattering and electron-photon interactions. It can either be viewed as a higher-order scattering process or interpreted in terms of Coulomb-induced admixtures of higher single-particle states to the multi-electron wave function7,8. What appears to be an optical relaxation of one electron in the single-particle picture involves, in fact, a sudden change of the many-particle configuration.

Radiative Auger emission has been observed over a large spectral range: in the X-ray emission of atoms9; close to visible frequencies on donors in semiconductors10 and quantum emitters11,12; and at infrared frequencies as shake-up lines in two-dimensional systems13,14,15,16,17. Furthermore, radiative Auger connects carrier dynamics to the quantum optical properties of the emitted photons11, making it a powerful probe of multi-particle systems. Driving the fundamental transition between the electron ground state and an optically excited state is an important technique in quantum optics18,19. In contrast, driving the radiative Auger transition has not been achieved, neither on atoms nor on solid-state systems. Success here would significantly increase the number of quantum optics techniques that can be employed.

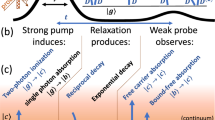

We demonstrate driving the radiative Auger transition on an epitaxial GaAs quantum dot embedded in AlGaAs20,21. The quantum dot forms a potential minimum and confines charge carriers, resulting in discrete energy levels like in an atom. Without optical illumination, a single electron is trapped in the conduction band of the quantum dot and occupies the lowest possible shell (the s-shell, \(\left|s\right\rangle\)). Upon resonant excitation of the fundamental transition, a second electron is promoted from the filled valence band to the conduction band and a negative trion X1− (\(\left|t\right\rangle\)) is formed. This trion consists of two electrons in the conduction band and one electron-vacancy (hole) in the valence band. Figure 1a shows the possible optical decay paths: in the fundamental transition, one electron decays, removing the valence band hole while the other electron remains in the conduction band ground state \(\left|s\right\rangle\); in the radiative Auger process, the remaining electron is left in an excited state \(|p\rangle\). The emitted photon is red-shifted by the energy separation between \(|p\rangle\) and \(\left|s\right\rangle\)5,11. Figure 1b shows a typical emission spectrum from the trion decay. This spectrum is measured on resonantly driving the fundamental transition \(\left|s\right\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\) at 384.7 THz (1.591 eV) with a narrow-bandwidth laser11. Red-shifted by 3.2 THz (13.2 meV) from the fundamental transition, there is a weak satellite line that arises from the radiative Auger process.

a Schematic illustration of the fundamental transition and the radiative Auger process. The trion state \(\left|t\right\rangle\) optically decays by recombination of one electron in the conduction band (cb) with a hole in the valence band (vb). The second electron either stays in its ground state \(\left|s\right\rangle\) (fundamental transition), or is left in a higher shell \(\left|p\right\rangle\) (radiative Auger). The radiative Auger photon is red-shifted from the fundamental transition by the energy transferred to the Auger electron. b Emission spectrum from a negatively charged quantum dot upon optical excitation at the fundamental transition. In addition to the fundamental transition (highlighted in blue), there is a red-shifted satellite line (highlighted in red). This emission arises from the radiative Auger process, where the trion state \(\left|t\right\rangle\) decays to the excited electron state \(\left|p\right\rangle\). c Two possible absorption channels in the presence of one confined conduction band electron. When the electron is in the ground state \(\left|s\right\rangle\), a laser resonant with the fundamental transition (blue, frequency ω1, Rabi frequency Ω1) excites a valence band electron and brings the system to the trion state, \(\left|t\right\rangle\). When the conduction band electron is in an excited state \(\left|p\right\rangle\), a red-shifted laser (frequency ω2, Rabi frequency Ω2) can excite the system to the same trion state \(\left|t\right\rangle\). In this inverted radiative Auger process, the missing energy is provided by the excited electron. d Resonance fluorescence from the fundamental transition in the presence of a strong second laser. When the second laser (ω2) is on resonance with the radiative Auger transition (Δ2 = 0), the resonance fluorescence intensity is strongly reduced.

Photons at the radiative Auger frequency have insufficient energy to excite the fundamental transition \(\left|s\right\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\). Figure 1c shows how the trion state \(\left|t\right\rangle\) still can be excited with a laser at the Auger transition. The missing energy is provided by the electron, which initially occupies the excited state \(|p\rangle\). However, driving the radiative Auger transition is experimentally challenging for two main reasons: first, there is a fast non-radiative relaxation from the excited single-electron state \(|p\rangle\) back to \(\left|s\right\rangle\)11,22, and the state \(|p\rangle\) is not occupied at thermal equilibrium. Second, the dipole moment of the radiative Auger transition is small. Therefore, it is difficult to achieve high Rabi frequencies on driving the transition, plus the radiative Auger emission is very weak and hard to distinguish from the back-reflected laser light.

Results

We perform a two-laser experiment revealing optical driving of the radiative Auger transition. The fundamental transition \(|s\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\) (at ~ 1.591 eV) is driven with one laser (labelled by ω1) while the radiative Auger transition (at ~ 1.578 eV) is simultaneously driven with a second laser (labelled by ω2). This Λ-configuration has the following advantages: First, on driving \(\left|s\right\rangle\)–\(|t\rangle\) with ω1, there is a small chance of initializing the system in state \(|p\rangle\) via the radiative Auger emission. Additionally, driving the \(|p\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\)-transition with ω2, while transferring population to \(\left|t\right\rangle\) with ω1 also leads to a finite occupation of \(|p\rangle\). Second, the small dipole matrix element of the radiative Auger transition is compensated by using high power for ω2. The high power causes a high laser background when detecting the fluorescence from the radiative Auger transition. Instead, we tune the second laser over the Auger transition while measuring just the fluorescence originating from the fundamental transition \(\left|s\right\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\). Figure 1d shows the result of this two-laser experiment. We observe a strong reduction in fluorescence on addressing the transition \(|p\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\) which is characteristic of two-colour excitation of a Λ-configuration. Our approach has a conceptual similarity to the driving of weak phonon sidebands of mechanical resonators resulting in optomechanically induced transparency23,24.

Autler–Townes splitting in single-laser experiments

We consider initially the situation where the fundamental transition (\(\left|s\right\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\)) is strongly driven by a single laser. If radiative Auger and fundamental transition form a Λ-system, one would expect an Autler–Townes splitting in the radiative Auger emission. Figure 2a shows the corresponding level scheme including the dressed states \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left|N+1,s\right\rangle \pm \left|N,t\right\rangle )\) and \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left|N,s\right\rangle \pm \left|N-1,t\right\rangle )\), where N is the photon number. The dressed-state splitting leads to the Mollow triplet in the resonance fluorescence19,25,26. For a decay into a third level, the Autler–Townes splitting27,28 in the emission is expected to be Ω1. Figure 2b shows the radiative Auger emission of one quantum dot (QD1). In this measurement, the laser is on resonance with the fundamental transition. The Rabi frequency (Ω1 = 2π × 31.9 GHz, red bar in Fig. 2b) is estimated independently by measuring the fluorescence intensity as a function of laser power (Supplementary Fig. 3b). We observe an Autler–Townes splitting that agrees well with this Rabi frequency. For this quantum dot, we also observe an additional weak emission appearing on the low energy side of the spectrum when using high Rabi frequencies (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 4). We speculate that this emission is connected to optical coupling between \(|p\rangle\) and an excited trion state, \(\left|{t}^{* }\right\rangle\). Figure 2c shows radiative Auger emission from a second quantum dot (QD2). For this quantum dot, we measure the radiative Auger emission as a function of detuning between the quantum dot transition and the laser (see Supplementary Fig. 4 for the corresponding measurement on QD1). On applying a gate voltage ΔVg, the quantum dot transition \(\left|s\right\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\) is detuned from the fixed laser by Δ1 = ΔVg ⋅ Ss via the quantum-confined Stark shift. Ss parameterizes the Stark shift of the fundamental transition. At zero detuning, the observed Autler–Townes splitting again agrees with the Rabi frequency obtained from a power saturation curve (Ω1 = 2π × 67.7 GHz).

a Level scheme under strong resonant driving of the fundamental transition (\(\left|s\right\rangle\)−\(\left|t\right\rangle\)). The energy levels of the transition are split into dressed states. The splitting between the dressed states is given by the Rabi frequency, Ω1. In the radiative Auger emission (red arrows), the dressed-state splitting creates two decay paths leading to an Autler–Townes splitting. b Radiative Auger emission from the main quantum dot (QD1) on driving the transition \(\left|s\right\rangle\)−\(\left|t\right\rangle\) with ω1. The Rabi frequency of Ω1 = 2π × 31.9 GHz (red bar) is determined from a power saturation curve. The measured Autler–Townes splitting in the emission matches the Rabi frequency. c Emission spectrum from a second quantum dot (QD2), measured for a set of different detunings (Δ1 = ΔVg ⋅ Ss) between fundamental transition and laser frequency. The upper part of the plot is a line cut along the dashed green line at zero detuning (Δ1 = 0). In this case, the measured Autler–Townes splitting agrees with the independently determined Rabi frequency (Ω1 = 2π × 67.7 GHz).

Two-laser experiments

We now consider the experiments with the second laser (labelled as ω2) at the radiative Auger transition. Figure 3a shows the corresponding level scheme. We set ω1 to a modest Rabi frequency (Ω1 = 2π × 0.08 GHz) compared to the decay rate of the trion (Γr = 2π × 0.50 GHz). The frequency of the radiative Auger transition is estimated from the trion emission spectrum (Fig. 1b). We sweep the frequency ω2 and simultaneously monitor the resonance fluorescence intensity from the fundamental transition. Figure 3b shows this measurement for different powers of the laser on the Auger transition. On increasing the power of ω2 to several orders of magnitude higher than the power of ω1, there is a pronounced dip in the fluorescence intensity. This intensity dip appears precisely when the laser frequency ω2 matches the radiative Auger transition (\(|p\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\)) and is characteristic for a Λ-system that is driven with two lasers. We estimate the Rabi frequency Ω2 driving \(|p\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\) by simulating the resonance fluorescence intensity as a function of Δ2 (see Supplementary Note 1 for the quantum optics simulation). In this simulation, we keep the decay rate from \(|p\rangle\) to \(\left|s\right\rangle\) (Γp ~ 2π × 9.3 GHz) fixed to the value that we determine from independent auto- and cross-correlation measurements11 (Supplementary Fig. 2d). The value for Ω2 can then be determined by a corresponding fit to the two-laser experiment. Additionally, we fit a constant pure dephasing, γp, for the state \(|p\rangle\) which leads to an additional broadening of the fluorescence dip. We estimate γp ~ 2π × 8.8 GHz from the fit and a Rabi frequency of Ω2 = 2π × 3.2 GHz (ω2) for the strongest fluorescence dip. Note that additional excitation-induced dephasing via phonons is expected to be weak for such Rabi frequencies29,30.

a The level scheme where one laser (ω1) with Rabi frequency Ω1 drives the fundamental transition (\(\left|s\right\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\)) while a second laser (ω2) drives the radiative Auger transition (\(\left|p\right\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\)) with Rabi frequency Ω2. b Resonance fluorescence (Ω1 = 2π × 0.08 GHz) as a function of detuning Δ2 (detuning of ω2). At low values of Ω2, the resonance fluorescence intensity is almost constant for different values of Δ2. For the highest value of Ω2, the resonance fluorescence drops by up to ~ 70% on bringing ω2 into resonance with the radiative Auger transition. The strong fluorescence dip at a particular frequency is a characteristic feature of a Λ-system driven with two lasers that are detuned in frequency by the ground state splitting. c Resonance fluorescence at Δ2 = 0 as a function of Ω2. The resonance fluorescence intensity (blue dots) drops with increasing Ω2, fitting well to the theoretical model (black line). d Fluorescence intensity as a function of detuning Δ2. The Rabi frequencies are Ω1 = 2π × 0.27 GHz, Ω2 = 2π × 2.1 GHz. The same measurement is repeated for a series of fixed detunings Δ1 (detuning of ω1 from the fundamental transition). Detuning ω1 leads to an asymmetric fluorescence dip. This asymmetry is well captured by our quantum optics simulations (black lines) based on the level scheme shown in (a). e Fluorescence intensity as a function of laser detunings Δ1, Δ2. f Simulation of the fluorescence intensity as a function of the laser detunings.

In Fig. 3c, we plot the minimum of the resonance fluorescence dip as a function of Ω2. The Λ-system model with two driving lasers fits this data set well. For the highest value of Ω2, we achieve a reduction of the resonance fluorescence intensity by up to 70%. The intensity reduction is limited by the power that we can reach in our optical setup. The measurement shows that resonance fluorescence can be switched on and off by using the radiative Auger transition. In our system, part of the fluorescence dip is due to the reduction of the overall absorption via the formation of a dark state. This effect is related to electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT)31 and coherent population trapping (CPT)32,33. An additional reduction of the signal comes from the fact that there is a fast decay rate Γp from state \(|p\rangle\) to \(\left|s\right\rangle\). Thus, after the laser-induced transition from state \(\left|t\right\rangle\) to \(|p\rangle\), the system quickly decays to the ground state \(\left|s\right\rangle\). This de-excitation channel reduces the population of the trion state and, therefore, the fluorescence intensity. We can distinguish the contributions of the two mechanisms by our quantum optics simulation. The density matrix element ρtt (occupation of state \(\left|t\right\rangle\)) is proportional to the overall fluorescence intensity. The term Im(ρst) (coherence between the states \(\left|s\right\rangle\) and \(\left|t\right\rangle\)) is proportional to the absorption and reflects the coherent part of the intensity reduction. The contribution of both mechanisms is comparable for the parameter regime in which we operate (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

The measurements so far were performed with ω1 on resonance (Δ1 = 0). We repeat the two-laser experiments while detuning ω1 from the fundamental transition. Figure 3d shows the fluorescence intensity for positive, zero, and negative detuning Δ1. For non-zero detuning, the fluorescence dip is asymmetric as a function of Δ2. The asymmetry is an important result as it cannot be explained by a rate equation description, but depends on the quantum coherence in the master equation model (Supplementary Note 1). The full dependence of the resonance fluorescence intensity as a function of Δ1 and Δ2 is plotted in Fig. 3e. This data set fits well to the corresponding quantum optics simulation in Fig. 3f using the parameters from the previous measurements.

Discussion

Upon the optical transition of a carrier, radiative Auger leaves other carriers in an excited orbital state, and the emitted photon is red-shifted. We show here that this process can be inverted: radiative Auger exists in absorption and the corresponding transition can be optically driven. In both emission and absorption, the process has conceptual similarities to phonon scattering. For radiative Auger emission, the electronic configuration is left in an excited state, for the phonon sideband, the lattice configuration34,35. We demonstrate that the resonance fluorescence can be strongly reduced by addressing the radiative Auger transition: a modulated laser on the radiative Auger transition could be used for fast optical gating of the emitter’s absorption. As an outlook, we suggest that an effective coupling between orbital states, split by frequencies in the THz band, can be created by two lasers at optical frequencies. The idea here is to establish a Raman-like process: the lasers are equally detuned from their resonances, and an exciton is not created. This scheme facilitates control of the orbital degree of freedom with techniques that have been developed for manipulating spin-states33,36. Further quantum optics experiments with radiative Auger photons are conceivable: by using a two-colour Raman-scheme37, it might be possible to create deterministically highly excited shake-up states that are also subject of recent theoretical investigations38. Adding a third laser with a THz-frequency at the transition \(\left|s\right\rangle\)–\(|p\rangle\)22 might even allow close-contour driving schemes39. In analogy to experiments on spins40, the radiative Auger process could lead to an entanglement between the frequency of the emitted photon and the orbital state of the Auger electron.

Methods

For all our measurements, the quantum dot sample is kept in a liquid helium bath cryostat at 4.2 K. The quantum dots used in this work are GaAs quantum dots in AlGaAs grown by molecular beam epitaxy. Their decay rates Γr (typically in the range 2π × (0.5 − 0.6) GHz) were determined by lifetime measurements using pulsed resonant excitation21. The decay rate of the radiative Auger transition, ΓA ~ Γr/100, is estimated by comparing its emission intensity to the fundamental transition. QD1 is identical to the second quantum dot in Ref. 21. The quantum dots presented in this work have a stronger radiative Auger emission compared to other III-V quantum dots11 indicating a stronger dipole moment of the radiative Auger transition. We use radiative Auger lines where the final state of the Auger electron, \(|p\rangle\), is a quantum dot p-shell. In particular, we investigate the transition associated with the lower p-shell (p+) for QD1 and the higher p-shell (p−) for QD2. We can assign further emission lines to the corresponding higher electronic shells by measuring the magnetic field dispersion of the emission spectrum11 (Supplementary Fig. 3a).

To excite the quantum dots, we use a tunable diode laser with a narrow bandwidth ( ~ 100 kHz) far below the quantum dot linewidth. Resonant excitation is not necessary to observe the radiative Auger emission: above-band excitation is also effective7,12. It is also possible to observe radiative Auger on systems that suffer from much more charge noise than ours12. However, resonant excitation has the advantage that no continuum states are excited making it easier to identify all emission lines, and low charge noise makes resonant excitation a lot easier to perform. For this work, resonant excitation is crucial to optically address a single radiative Auger transition. To suppress the reflected excitation laser, we use a cross-polarization scheme41.

To determine the relaxation rate Γp ( ~2π × 9.3 GHz) from \(|p\rangle\) to \(\left|s\right\rangle\), we make use of a technique developed in Ref. 11: on driving \(\left|s\right\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\) (Ω2 = 0), we measure an auto-correlation of the resonance fluorescence from the fundamental transition and compare it to the cross-correlation between resonance fluorescence from the fundamental transition and radiative Auger emission. The corresponding measurement setups are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5a, b. To resolve the auto- and cross-correlations with high time resolution, we use two superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors (SingleQuantum) with a timing jitter below 20 ps (FWHM) in combination with correlation hardware (Swabian Instruments).

Compared to the auto-correlation, the cross-correlation has a small time offset when a radiative Auger photon is followed by a photon from the fundamental transition (Supplementary Figs. 2d, e). This time scale corresponds to the relaxation time, τp = 1/Γp, describing the relaxation from \(|p\rangle\) to \(\left|s\right\rangle\). The relaxation time appears in the cross-correlation: when a radiative Auger event is detected by the first detector, there is an additional waiting time of τp before the excited Auger electron relaxes to the ground state and the system can be optically re-excited. Therefore, it takes longer before a second photon is detected. The additional waiting time is only present for the cross-correlation. For the auto-correlation, the system decays directly to the ground state \(\left|s\right\rangle\) and there is no additional waiting time.

Finally, we also measure the auto-correlation of the radiative Auger emission (see Supplementary Fig. 5c for the setup). The measurement is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5e. We observe a pronounced anti-bunching at zero delays proving the single-photon nature of the radiative Auger photons. Going beyond the results in Ref. 11, we observe the Rabi oscillation from strongly driving the transition \(\left|s\right\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\) in the photon-statistics of the radiative Auger photons from the transition \(|p\rangle\)–\(\left|t\right\rangle\).

Data availability

The data that supports this work is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that has been used for this work is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bambynek, W. et al. X-ray fluorescence yields, Auger, and Coster–Kronig transition probabilities. Rev. Mod. Phys. 44, 716–813 (1972).

Efros, A. L. & Rosen, M. Random telegraph signal in the photoluminescence intensity of a single quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1110–1113 (1997).

Kurzmann, A., Ludwig, A., Wieck, A. D., Lorke, A. & Geller, M. Auger recombination in self-assembled quantum dots: Quenching and broadening of the charged exciton transition. Nano Lett. 16, 3367–3372 (2016).

Vaxenburg, R., Lifshitz, E. & Efros, A. L. Suppression of Auger-stimulated efficiency droop in nitride-based light emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 031120 (2013).

Bloch, F. Double electron transitions in X-ray spectra. Phys. Rev. 48, 187 (1935).

Hawrylak, P. Resonant magnetoexcitons and the fermi-edge singularity in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 44, 11236–11240 (1991).

Llusar, J. & Climente, J. I. Nature and control of shakeup processes in colloidal nanoplatelets. ACS Photonics 7, 3086–3095 (2020).

Stöhr, J. NEXAFS Spectroscopy Vol. 25 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Åberg, T. & Utriainen, J. Evidence for a “Radiative Auger effect" in X-ray photon emission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 22, 1346–1348 (1969).

Dean, P. J., Cuthbert, J. D., Thomas, D. G. & Lynch, R. T. Two-electron transitions in the luminescence of excitons bound to neutral donors in gallium phosphide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 18, 122–124 (1967).

Löbl, M. C. et al. Radiative Auger process in the single-photon limit. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 558–562 (2020).

Antolinez, F. V., Rabouw, F. T., Rossinelli, A. A., Cui, J. & Norris, D. J. Observation of electron shakeup in CdSe/CdS core/shell nanoplatelets. Nano Lett. 19, 8495–8502 (2019).

Nash, K. J., Skolnick, M. S., Saker, M. K. & Bass, S. J. Many body shakeup in quantum well luminescence spectra. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 3115–3118 (1993).

Skolnick, M. S. et al. Fermi sea shake-up in quantum well luminescence spectra. Solid-State Electron. 37, 825–829 (1994).

Finkelstein, G., Shtrikman, H. & Bar-Joseph, I. Mechanism of shakeup processes in the photoluminescence of a two-dimensional electron gas at high magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 56, 10326–10331 (1997).

Manfra, M. J., Goldberg, B. B., Pfeiffer, L. & West, K. Anderson-Fano resonance and shake-up processes in the magnetophotoluminescence of a two-dimensional electron system. Phys. Rev. B 57, R9467–R9470 (1998).

Bryja, L. et al. Magneto-optical probing of weak disorder in a two-dimensional hole gas. Phys. Rev. B 75, 035308 (2007).

Muller, A. et al. Resonance fluorescence from a coherently driven semiconductor quantum dot in a cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 187402 (2007).

Flagg, E. B. et al. Resonantly driven coherent oscillations in a solid-state quantum emitter. Nat. Phys. 5, 203 (2009).

Wang, Z. M., Liang, B. L., Sablon, K. A. & Salamo, G. J. Nanoholes fabricated by self-assembled gallium nanodrill on GaAs(100). Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 113120 (2007).

Zhai, L. et al. Low-noise GaAs quantum dots for quantum photonics. Nat. Commun. 11, 4745 (2020).

Zibik, E. et al. Long lifetimes of quantum-dot intersublevel transitions in the terahertz range. Nat. Mater. 8, 803–807 (2009).

Weis, S. et al. Optomechanically induced transparency. Science 330, 1520–1523 (2010).

Safavi-Naeini, A. H. et al. Electromagnetically induced transparency and slow light with optomechanics. Nature 472, 69–73 (2011).

Mollow, B. R. Power spectrum of light scattered by two-level systems. Phys. Rev. 188, 1969–1975 (1969).

Ulhaq, A. et al. Cascaded single-photon emission from the Mollow triplet sidebands of a quantum dot. Nat. Photon. 6, 238–242 (2012).

Autler, S. H. & Townes, C. H. Stark effect in rapidly varying fields. Phys. Rev. 100, 703–722 (1955).

Xu, X. et al. Coherent optical spectroscopy of a strongly driven quantum dot. Science 317, 929–932 (2007).

Ramsay, A. J. et al. Phonon-induced Rabi-frequency renormalization of optically driven single InGaAs/GaAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 177402 (2010).

Reiter, D. E., Kuhn, T. & Axt, V. M. Distinctive characteristics of carrier-phonon interactions in optically driven semiconductor quantum dots. Adv. Phys.: X 4, 1655478 (2019).

Fleischhauer, M., Imamoglu, A. & Marangos, J. P. Electromagnetically induced transparency: Optics in coherent media. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 633–673 (2005).

Aspect, A., Arimondo, E., Kaiser, R., Vansteenkiste, N. & Cohen-Tannoudji, C. Laser cooling below the one-photon recoil energy by velocity-selective coherent population trapping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 826–829 (1988).

Prechtel, J. H. et al. Decoupling a hole spin qubit from the nuclear spins. Nat. Mater. 15, 981–986 (2016).

Quilter, J. H. et al. Phonon-assisted population inversion of a single InGaAs/GaAs quantum dot by pulsed laser excitation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 137401 (2015).

Brash, A. J. et al. Light scattering from solid-state quantum emitters: beyond the atomic picture. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 167403 (2019).

Press, D., Ladd, T. D., Zhang, B. & Yamamoto, Y. Complete quantum control of a single quantum dot spin using ultrafast optical pulses. Nature 456, 218–221 (2008).

Gangloff, D. A. et al. Quantum interface of an electron and a nuclear ensemble. Science 364, 62–66 (2019).

Bauman, N. P. et al. Towards quantum computing for high-energy excited states in molecular systems: quantum phase estimations of core-level states. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 17, 201–210 (2020).

Barfuss, A. et al. Phase-controlled coherent dynamics of a single spin under closed-contour interaction. Nat. Phys. 14, 1087–1091 (2018).

Gao, W. B., Fallahi, P., Togan, E., Miguel-Sanchez, J. & Imamoglu, A. Observation of entanglement between a quantum dot spin and a single photon. Nature 491, 426–430 (2012).

Kuhlmann, A. V. et al. A dark-field microscope for background-free detection of resonance fluorescence from single semiconductor quantum dots operating in a set-and-forget mode. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 84, 073905 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Krzysztof Gawarecki and Philipp Treutlein for fruitful discussions. We acknowledge financial support from Swiss National Science Foundation project 200020_175748, NCCR QSIT and Horizon 2020 FET-Open Project QLUSTER. LZ, GNN, AJ acknowledge support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement numbers 721394 / 4PHOTON (LZ), 861097 / QUDOT-TECH (GNN), 840453 / HiFig (AJ). JR, AL and ADW gratefully acknowledge financial support from the grants DFH/UFA CDFA05-06, DFG TRR160, DFG project 383065199, EU Horizon 2020 Grant No. 861097, and BMBF - QR.X KIS6QK4001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.R., L.Z., A.D.W. and A.L. grew the sample. C.S., L.Z., G.N.N. fabricated the sample. L.Z., M.C.L., J.R. and A.L. designed the sample. L.Z., C.S., G.N.N. and M.C.L. carried out the experiments. M.C.L., C.S., P.M., D.E.R., L.Z., G.N.N., A.J. and R.J.W. analysed the data and developed the theory. C.S. and M.C.L. prepared the various figures. MCL initiated and conceived the project. M.C.L. and R.J.W. wrote the manuscript with input from all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Spinnler, C., Zhai, L., Nguyen, G.N. et al. Optically driving the radiative Auger transition. Nat Commun 12, 6575 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26875-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26875-8

This article is cited by

-

Coherent control of a high-orbital hole in a semiconductor quantum dot

Nature Nanotechnology (2023)

-

Harmonizing single photons with a laser pulse

Nature Nanotechnology (2022)

-

Tailoring solid-state single-photon sources with stimulated emissions

Nature Nanotechnology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.