Abstract

The phase offset of quantum oscillations is commonly used to experimentally diagnose topologically nontrivial Fermi surfaces. This methodology, however, is inconclusive for spin-orbit-coupled metals where π-phase-shifts can also arise from non-topological origins. Here, we show that the linear dispersion in topological metals leads to a T2-temperature correction to the oscillation frequency that is absent for parabolic dispersions. We confirm this effect experimentally in the Dirac semi-metal Cd3As2 and the multiband Dirac metal LaRhIn5. Both materials match a tuning-parameter-free theoretical prediction, emphasizing their unified origin. For topologically trivial Bi2O2Se, no frequency shift associated to linear bands is observed as expected. However, the π-phase shift in Bi2O2Se would lead to a false positive in a Landau-fan plot analysis. Our frequency-focused methodology does not require any input from ab-initio calculations, and hence is promising for identifying correlated topological materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of topological semimetals promises an avenue to study novel materials that host quasiparticles that mimick relativistic Dirac and Weyl fermions in high-energy physics1,2,3,4. They host bands that touch at points or lines in momentum space; such degeneracies are typically associated with closed Fermi surfaces with topologically robust Berry phases. While initially considered a rare occurrence, recent ab-initio programs4,5,6,7 have predicted topological band degeneracies in a sixth of all non-magnetic materials in the crystal database5.

Magnetic quantum oscillations8 promise to play a key role in experimentally confirming these predictions. It is widely believed that a π-phase shift in quantum oscillations is interpretable as a π Berry phase, and therefore a smoking-gun confirmation of a topological semimetal. Such phase analysis, often carried out with a ‘Landau-fan plot’, ignores other non-geometric phase shifts, and forgets that the Berry phase is not quantized to an integer multiple of π for many symmetry classes of (semi)metals9,10. For this reason, an unambiguous topological diagnosis is generally impossible for the 3D Dirac semimetals1,2,3 and low-symmetry 3D Weyl semimetals9.

For these cases, we present a new identification method based on the temperature (T) dependence of the oscillation frequency (F), finding a characteristic T2 contribution that is uniquely attributed to the linear energy-momentum dispersion of Dirac, Weyl and multifold fermions11. This T2 contribution is a 3D, higher-degeneracy generalization of an effect predicted by Kübbersbusch and Fritz12 for 2D Dirac materials. To the best of our knowledge, this effect has never been experimentally studied in graphene, yet we will show that it is easy to see in 3D Weyl/Dirac materials. Our strategy applies to candidate topological Fermi pockets which are small compared to the Brillouin-zone volume; small pockets are accurately described by k ⋅ p Hamiltonians that retain only the leading-order term—giving a parabolic dispersion for the Schrödinger-type fermion, and a linear dispersion for the Dirac-type fermion. These two cases are distinguishable by the energy derivative of the cyclotron mass mc (Fig. 1). While ∂mc/∂E = 0 for a parabolic dispersion, for a linear dispersion \(E(k)=\pm \sqrt{{({v}_{x}\hslash {k}_{x})}^{2}+{({v}_{y}\hslash {k}_{y})}^{2}}\), the particular energy dependence of the Fermi-surface area S yields a non-zero energy derivative of the cyclotron mass:

with EF the Fermi energy measured from the Dirac point and vj the Fermi velocity.

a For a linearly dispersing Dirac-type pocket, the energy derivative of the cyclotron mass, \(\partial ({{{{{{\mathrm{log}}}}}}}\,{m}_{{{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}})/\partial E\) diverges when the Fermi level approaches the Dirac node. When approaching the Dirac node, the Fermi pocket shrinks and the cyclotron mass is continuously decreasing to zero, therefore the smaller the oscillation frequency, the larger the oscillation amplitude. Due to the thermal broadening of chemical potential, this ultimately leads to the quadratic temperature dependence of the quantum-oscillation frequency. In constrast, for a Schrödinger-type pocket with a parabolic dispersion, \(\partial ({{{{{{\mathrm{log}}}}}}}\,{m}_{c})/\partial E=0\). b Illustration of Sommerfeld contribution, describes the shift of chemical potential at finite temperatures due to thermal broadening with a fixed carrier density.

To experimentally determine ∂mc/∂E, we exploit the fact that quantum oscillations probe the band structure over an energy window (~kBT) around the Fermi level, due to the thermal broadening of the Fermi-Dirac distribution function. As lighter-mass particles experience less thermal damping than heavier particles, the effective frequency renormalizes towards lighter orbits as T increases. This effect is absent for parabolic bands because the effective mass is energy-independent. However, for a Dirac-type Fermi surface, the frequency decreases with increasing T because the effective mass is smaller closer to the node, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. This temperature-renormalization of F applies generally to linear dispersions near band degeneracies, including Dirac and Weyl degeneracies, as well as higher-fold degeneracies associated with Fermi pockets with higher Chern numbers (so-called ‘multifold fermions’)11.

Results

General methodology

To quantify this frequency shift, it is useful to view the Lifshitz–Kosevich formula13,14 as an asymptotic expansion in powers of kBT/EF (the degeneracy parameter of Fermi gases). Odd powers of T modify the oscillation amplitude, with the first odd power giving the well-known thermal damping factor; in contrast, even powers of T modify the frequency and phase. At elevated temperatures where 2π2kBT is large or comparable to the cyclotron energy, we derive in supplementary note 2(A) a T2-correction to the oscillation frequency:

with μ the chemical potential and β ≔ eℏ/2mc the effective Bohr magneton. The correction ΔFtop is our main theoretical result, and applies to any closed Fermi surface originating from an arbitrary energy-momentum dispersion, whether linear, quadratic, cubic or beyond. While ΔFtop vanishes for parabolic bands, it is finite for linear bands as \(| \partial ({{{{{{\mathrm{log}}}}}}}\,{m}_{c})/\partial E| =1/| {E}_{F}|\), according to Eq. (1), and we hence refer to ΔFtop as a topological correction to F.

Next we consider other mechanisms for the temperature dependence of the frequency. A distinct T2 correction arises from the temperature dependence of the chemical potential [μ(T)] at fixed particle density, as is well known in the Sommerfeld theory of metals15 (Fig. 1b). The sum of Sommerfeld and topological corrections is expressed in:

with Θ a dimensionless coefficient. In high-carrier-density metals with both small and large pockets, the Sommerfeld correction is negligible. The frequency shift of a small pocket is reduced by a factor ∣EF∣/Ebw ≪ 1, with EF the Fermi energy of the small pocket measured from band extremum/degeneracy, and Ebw the typical bandwith. Thus we expect that Θ is dominated by the topological correction, giving Θ ≈ 0 in the parabolic case, and Θ ≈ 1/16 in the case of a linear dispersion. For single-frequency, low-carrier-density semimetals, the Sommerfeld correction is of the same order of magnitude as the topological correction, giving Θ = 1/48 for parabolic bands and Θ = 5/48 for linear bands [see supplementary note 2(B) for extended calculation of Sommerfeld correction]. The two scenarios show that the observation of a T2 correction alone is not conclusive of nontrivial topology. Rather, conclusiveness comes from the following experimental consistency check: since F0(EF), mc and additionally the frequency shift at elevated temperatures all can be experimentally determined, by applying Eq. (3) one obtains an experimental value of Θ which should consistently equal the conditional values that our theory predicts.

In principle, the entropic contribution of electrons gives an additional T2 correction owing to the band-structure modification by thermal expansion16. However, this correction to F is typically of parts in 104 up to the highest temperature that quantum oscillations are observable8. Frequency shifts with a T4 dependence have been observed for a few, non-magnetic metals; these shifts were attributed to the lattice contribution to thermal expansion17,18, as well as the electron-phonon coupling19 [see supplementary note 2(A)]. Because of their distinct power law (T4) compared to the topological and Sommerfeld corrections (T2), lattice and electron-phonon effects would in principle be easy to detect and analyze separately.

Next, we discuss the identification of band topology. Our approach senses the linearity of bands and hence the topological character needs to be inferred. As the argument is based on a k ⋅ p expansion, it is only applicable to small Fermi surfaces that are much smaller than the Brillouin zone. As topological materials of practical relevance generally host small Fermi pockets, this criterion is typically fulfilled. Even when linear bands with a small Fermi pocket are detected, a question remains about distinguishing massive from massless Dirac materials. Conservatively speaking, one can never completely rule out the possibility that any hypothesized Dirac fermion has a tiny mass mD which leads to a weakly nonlinear energy dispersion \(E(k)=\pm \sqrt{{({v}_{x}\hslash {k}_{x})}^{2}+{({v}_{y}\hslash {k}_{y})}^{2}+{m}_{{{{{{\rm{D}}}}}}}^{2}}\) and \({{\Theta }}=(1/16)| {E}_{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}}| (| {E}_{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}}| +2| {m}_{{{{{{\rm{D}}}}}}}| )/{(| {E}_{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}}| +| {m}_{{{{{{\rm{D}}}}}}}| )}^{2}.\) The experimental uncertainty in Θ can be used to set an upper bound on ∣mD∣. If the dispersion at the Fermi level is experimentally indistinguishable from a linear one, a hypothetical gap at the node is necessarily much smaller than the chemical potential (measured from the node), and has negligible influence on the low-energy excitations. For example, graphene with a typical chemical potential (~meV) is well described by massless Dirac fermions, despite the existence of a spin-orbit-induced gap (~μeV)20.

High temperatures are natural opponents of quantum oscillations, because discontinuous changes in the occupation of Landau levels are smoothened out by the Fermi-Dirac distribution, as illustrated in the top panel of Fig. 2. The characteristic T2 dependence for F is observable at a temperature scale T* where 2π2kBT* is comparable to the cyclotron energy, while for T ≫ T* oscillations are exponentially suppressed by thermal damping8. The optimal temperature window for observing F(T) is determined approximately by plotting the product (of the frequency shift and the amplitude) as a function of T, as in Fig. 2. Since T* is inversely proportional to the effective mass mc, the requirement for elevated temperatures does not preclude their observation even when quasiparticles masses are heavy, it simply reduces the optimal temperature window to lower values. For example, for mc that is ten times the free-electron mass, Fig. 2 predicts the optimal temperature window to be between 0.1 and 1 K. Our method hence is expected to apply to strongly interacting topological materials with strong mass renormalization. Detailed discussion on applicability to heavy-fermion materials can be found in supplementary note 2(C).

The upper square panel displays the temperature dependence of the quantum-oscillation amplitude (ΔA = A(T) − A0) and topological frequency shift ΔFtop(T). The temperature axis is scaled by the ratio of cyclotron to free-electron mass, and F0 and A0 stand for the frequency and amplitude at zero temperature, respectively. −ΔFtop/F0 steeply increases just before the oscillation amplitude vanishes; this corresponds to the temperature regime where thermal broadening is comparable to the cyclotron energy (εc ≈ 2π2kBT), as illustrated by the filled density-of-states (DOS) plot for various temperatures (at the very top of figure). The lower square panel plots the temperature dependence of −(ΔFtop/F0)⋅(A/A0); its peak identifies the optimal temperature to observe the topological frequency shift; our scaling of the temperature axis implies the optimal temperature is inversely proportional to the cyclotron mass.

Detection and analysis of temperature-dependent quantum-oscillation frequency

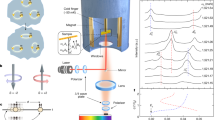

Experimentally, these predictions turn out to be readily observable. Three distinct materials were analyzed (Fig. 3): (i) Cd3As2 is a well-studied prototypical Dirac semimetal with a time-reversal-related pair of Dirac-type Fermi pockets and no other pockets (F ≈ 43.7 T)21. (ii) Bi2O2Se is a topologically trivial semimetal with a single, small electron pocket centered at Γ (F ≈ 33.3 T)22. (iii) LaRhIn5 is a large-carrier-density, multiband metal that hosts Brillouin-zone-sized pockets23 in addition to a very small pocket (F ≈ 6.9 T) that is inconsistent with conventional Schrödinger-like behavior24. In their pioneering work, Mikitik and Sharlai proposed that the small pocket encloses a Dirac nodal line25, based on an assumption that the spin-orbit coupling is perturbatively weak. However, our first-principles calculation [detailed in Supplementary note 2(D) and supplementary note 4] suggest this assumption to be unjustified, leaving the topology of the small pocket still in question.

a Band-structure illustration of three different types of materials, including Cd3As2 and Bi2O2Se where only one Fermi pocket and its symmetric copies sit at the Fermi level, as well as LaRhIn5 where the small, candidate Dirac Fermi pocket coexists with large trivial pockets. b Temperature-dependent SdH oscillations of small Fermi pockets for Cd3As2, LaRhIn5 and Bi2O2Se respectively. ρosc = Δρ/ρBG, with Δρ the oscillatory part of the magnetoresistivity, and ρBG a polynomial fit to the smooth background. The dashed black line represents the Lifshitz–Kosevich fit to the quantum oscillation measured at lowest temperature for each material. The magnetic field range is chosen to include as many low-noise quantum oscillations as possible, to improve the accuracy of frequency fitting. Exact device geometry and field/current orientations are described in the supplementary Material.

Crystalline microbars of (i–iii) for four-terminal resistivity measurements were prepared by Focused Ion Beam machining26. These microbars feature optimized geometries for longitudinal transport and provide high signal amplitudes even in the highly conductive materials studied here. All samples show pronounced quantum oscillations of the longitudinal magnetoresistance, with a single small frequency in the low-field regime (Fig. 3). We obtain F0(EF) from extrapolating the temperature-dependent oscillation frequency to zero temperature, and mc from the temperature dependence of the amplitude. For each material, the temperature dependence of the frequency is obtained from fitting the entire experimental dataset [measured at different temperatures and fields (see Fig. 4)] to a single Lifshitz–Kosevich formula9. The fitting is done by a standard least squares regression method using the nonlinear model fitting function provided by Mathematica, as detailed in supplementary note 3(A) and (B).

a The total frequency shift ΔF(T) versus T2(mc/me)/F0 for Cd3As2 and Bi2O2Se, both of which are semimetals with a single Fermi pocket plus symmetry-related copies (if any). b ΔF(T) for LaRhIn5, which has a single, small pocket with coexisting large pockets. The solid lines display the fitting-parameter-free theoretical expectations \({{\Theta }}{(\pi {k}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}T)}^{2}/{\beta }^{2}{F}_{0}\). For low-carrier density semimetal, Θ = 5/48 for Dirac case while for trivial case Θ = 1/48. For Dirac metal with high-carrier density Θ = 1/16. The filled squares and circles represent the experimentally determined value for different materials. c The frequency shift after subtracting the Sommerfeld contribution (ΔFs); what remains is the topological frequency shift, if any. ΔF−ΔFs for both LaRhIn5 (circles) and Cd3As2 (red squares) fall on the expected theoretical line (solid, red) for Dirac semimetal/metal, while for the topologically trivial semimetal Bi2O2Se, the frequency shift nearly vanishes after subtraction. d Landau-fan plots of Cd3As2 and Bi2O2Se. The solid and empty symbols represent valleys and peaks of the quantum oscillations. Following the common interpretation of the residual Landau index (n0 times 2π) as a quantized Berry phase, one would erroneously diagnose both Cd3As2 and Bi2O2Se as topologically nontrivial. All error bars in this figure are determined by the standard error of the fitting parameters generated by the nonlinear regression fitting procedure.

Both Cd3As2 and Bi2O2Se are low-carrier-density materials in which the Sommerfeld correction applies, and accordingly a clear frequency shift, ΔF(T), is observed in both of them (Fig. 4). It is evident from the raw data that Cd3As2 exhibits a stronger frequency shift compared to the trivial Bi2O2Se. For both cases, ΔF(T) falls directly onto the theoretical predictions \({{\Theta }}{(\pi {k}_{{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}}}T)}^{2}/{\beta }^{2}{F}_{0}({E}_{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}})\) from Eq. (3) for the trivial and topological case respectively. For Cd3As2, Θ = 5/48, as predicted for a Dirac semimetal with only two time-reversal-related Fermi pockets; for Bi2O2Se, Θ = 1/48 is consistent with a conventional semimetal with a single Fermi pocket. We emphasize that the coefficient of T2 has no tuning parameter as F0(EF) and mc are fixed by measurement results, i.e., theory fixes Θ to take on different rational values depending on whether the pocket is Schrödinger or Dirac type.

In comparison, LaRhIn5 is a high-carrier-density metal, and hence the measured ΔF(T) (for three devices) directly matches the prediction of Θ = 1/16, a purely topological correction. This confirms the small 7 T pocket of LaRhIn5 is Dirac type, with a chemical potential that is pinned by other large coexisting pockets.

The universal topological aspect of these distinct compounds becomes evident after subtracting the Sommerfeld correction described by supplementary Eq. (10) and (11) from the experimental ΔF for Bi2O2Se and Cd3As2. Remarkably, Cd3As2 and all three devices of LaRhIn5 collapse on the same red line in Fig. 4c despite their highly different band structures and microscopic details, highlighting the common topological origin of ΔFtop and its insensitivity to material-specific details. Instructively, a quantum-oscillation phase analysis of Bi2O2Se and Cd3As2 by the Landau-fan-diagram method uncovers a π-phase shift in both of them (see Fig. 4d), despite their clearly distinct topology, exemplifying the faults of this method.

These results can be further quantitatively strengthened by the self-consistency of ∣EF∣ computed by two different ways. From k ⋅ p theory, it can be expressed in terms of the standard Lifshitz–Kosevich parameters: ∣EF∣ = 2eℏF0/mc for the linearized Dirac pocket, and ∣EF∣ = eℏF0/mc for the quadratic Schrödinger pocket. On the other hand, ∣EF∣ can also be determined via ΔF(T): in the Dirac case, \(| {E}_{{{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}}| =| \frac{\partial E}{\partial ({{{{{{\mathrm{log}}}}}}}\,{m}_{{{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}})}|\) [cf. Eq. (1)] is deducible from the topological correction, while in the Schrödinger case ∣EF∣ is deducible15 from the Sommerfeld correction to F. For the model correctly describing the topology of the pocket, both estimates for ∣EF∣ should be consistent, and indeed this is what Table 1 shows. This allows for a simple self-consistency check. By analyzing a measured temperature-dependent quantum-oscillation frequency F(T) within both the Dirac/Weyl and Schrödinger framework, the match of both ∣EF∣ signals the correct k ⋅ p model.

Discussions

To conclude, our experimental methodology allows us to diagnose the linear dispersion of small, topological Fermi pockets, as demonstrated by our three case studies. Despite their microscopic differences, all Dirac/Weyl/multifold fermions have a linear dispersion close to the nodal degeneracy. The linear dispersion is directly sensed by the temperature dependence of the oscillation frequency when the Fermi level is also close to the node. It is also capable of identifying multi-Weyl fermions protected by crystallographic rotational symmetry, e.g., the dispersion of a double–Weyl (triple-Weyl) fermion is quadratic (cubic) in two momentum directions and linear in the third direction27, hence they would be identifiable by measuring F(T) at various field orientations. Our methodology is applicable independent of the magnitude of the Zeeman splitting of Landau levels; this magnitude would affect the relative amplitudes of higher harmonics of quantum oscillations9 but not their frequency.

Because the energy scale for band inversion tends to be small compared to the bandwidth, topological Fermi pockets are often small compared to the Brillouin zone. It is not impossible for highly inverted materials that the dispersion of larger topological Fermi pockets acquires substantial nonlinear corrections, in which case our methodology becomes less useful for topological diagnosis. It is also less straightforward to subtract the Sommerfeld correction (from the frequency shift) in materials where a topological Fermi pocket coexists with a non-topological pocket of comparable size; here, supplementing our methodology with a first-principles calculation may be useful to isolate the topological frequency shift.

It will be interesting to apply our method to investigate the topology of Fermi-liquid materials with extreme interaction-driven mass enhancement (e.g., heavy-fermion materials), with the caveat that the optimal temperature for measuring F(T) is inversely proportional to the effective mass. The presence of Dirac fermions in LaRhIn5 suggests that the intimately related Ce(Co, Rh, Ir)In5 are prime candidates for such efforts. The Ce family has a similar band structure to LaRhIn5, but are more prone to correlation-driven instabilities such as unconventional superconductivity28. A different class of correlated topological metals include the Kondo–Weyl semimetals29,30, in which itinerant electronic bands hybridize with localized (4f/5f)-states leading to strongly renormalized Weyl dispersions.

As the field matures towards strongly interacting topological matter, it leaves the comfort zone in which ab-initio-predicted topological band structures can straightforwardly be confirmed by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. The new conceptual and experimental challenges—arising from competing, near-degenerate ground states and unconventional superconductivity—call for new approaches to detect low-energy excitations and assess their topological character. Extending the framework of quantum oscillations to topologically nontrivial Fermi surfaces, as presented here, will play a major role in this development.

Methods

Microstructure fabrication

Micro-devices of all materials are fabricated with a FEI Helios Plasma FIB using Xe-ions. Thin slab (lamella) was dig out from a single crystalline material, which was transferred and glued down to a sapphire substrate. The transferred lamella was later patterned to the desired geometry with the Plasma FIB.

Band-structure calculations

To check for the robustness of band-structure results against choices of functionals in the calculation, the calculations were performed via two independent methods which are both detailedly described in supplementary note 4(A).

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are deposited to Zenodo with the access link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5482689.

Code availability

Mathematica code used for the Lifshitz–Kosevich fit of temperature-dependent quantum oscillations can be found via the access link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5482689.

References

Armitage, N. P., Mele, E. J. & Vishwanath, A. Weyl and Dirac semimetals in three-dimensional solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015001 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Dirac semimetal and topological phase transitions in A3Bi (A = Na, K, Rb). Phys. Rev. B 85, 195320 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Three-dimensional Dirac semimetal and quantum transport in Cd3As2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 125427 (2013).

Bradlyn, B. et al. Topological quantum chemistry. Nature 547, 298 (2017).

Zhang, T. et al. Catalogue of topological electronic materials. Nature 566, 475 (2019).

Vergniory, M. G. et al. A complete catalogue of high-quality topological materials. Nature 566, 480 (2019).

Tang, F., Po, H. C., Vishwanath, A. & Wan, X. G. Comprehensive search for topological materials using symmetry indicators. Nature 566, 486 (2019).

Shoenberg, D. Magnetic Oscillations in Metals (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Alexandradinata, A., Wang, C., Duan, W. & Glazman, L. Revealing the topology of fermi-surface wave functions from magnetic quantum oscillations. Phys. Rev. X 8, 011027 (2018).

Alexandradinata, A. & Glazman, L. Semiclassical theory of Landau levels and magnetic breakdown in topological metals. Phys. Rev. B 97, 144422 (2018).

Bradlyn, B. et al. Beyond Dirac and Weyl fermions: Unconventional quasiparticles in conventional crystals. Science 353, aaf5037 (2016).

Küppersbusch, C. & Fritz, L. Modifications of the Lifshitz-Kosevich formula in two-dimensional Dirac systems. Phys. Rev. B 96, 205410 (2017).

Roth, L. M. Semiclassical theory of magnetic energy levels and magnetic susceptibility of Bloch electrons. Phys. Rev. 145, 434 (1966).

Lifshitz, I. M. & Kosevich, A. Theory of magnetic susceptibility in metals at low temperature. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2, 636 (1956).

Ashcroft, N. W. & Mermin, N. D. Solid State Physics (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976).

Barron, T. H. K., Collins, J. G. & White, G. K. Thermal expansion of solids at low temperatures. Adv. Phys. 29, 609 (1980).

Berlincourt, T. G. & Steele, M. C. Temperature-dependent de Haas-Van Alphen parameters in zinc. Phys. Rev. 95, 1421 (1954).

O’Sullivan, W. J. & Schirber, J. E. Pressure dependence of the low-frequency de Haas-van Alphen oscillations in Zn. Phys. Rev. 151, 484 (1966).

Lonzarich, G. G. & Cooper, N. S. Temperature dependence of the Fermi surface of gold. J. Phys. F: Met. Phys. 13, 2241 (1983).

Sichau, J. et al. Resonance microwave measurements of an intrinsic spin-orbit coupling gap in graphene: a possible indication of a topological state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 046403 (2019).

Crassee, I. et al. 3D Dirac semimetal Cd3As2: a review of material properties. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 120302 (2018).

Wu, J. et al. High electron mobility and quantum oscillations in non-encapsulated ultrathin semiconducting Bi2O2Se. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 530 (2017).

Shishido, H. et al. Fermi surface, magnetic and superconducting properties of LaRhIn5 and CeTIn5 (T: Co, Rh and Ir). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 71, 162 (2002).

Goodrich, R. G. et al. Magnetization in the ultraquantum limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 026401 (2002).

Mikitik, G. P. & Sharlai, Y. V. Berry phase and de Haas-van Alphen effect in LaRhIn5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 106403 (2004).

Moll, P. J. W. Focused ion beam microstructuring of quantum matter. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 9, 147 (2018).

Fang, C., Gilbert, M. J., Dai, X. & Bernevig, B. A. Multi-Weyl topological semimetals stabilized by point group symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 266802 (2012).

Thompson, J. D. & Fisk, Z. Progress in heavy-Fermion superconductivity: Ce115 and related materials. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 81, 011002 (2012).

Lai, H. H., Grefe, S. E., Paschen, S. & Si, Q. Weyl-Kondo semimetal in heavy-fermion systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 93 (2018).

Chang, P. Y. & Coleman, P. Parity-violating hybridization in heavy Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 97, 155134 (2018).

Acknowledgements

A.A. was supported initially by the Yale Postdoctoral Prize Fellowship, and subsequently by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation EPiQS Initiative through Grant No. GBMF 4305 and GBMF 8691 at the University of Illinois. S.Z, Q.W. and O.V.Y. acknowledge support by NCCR Marvel and the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS) under Projects No. s832 and No. s1008. M.D.B. acknowledges studentship funding from EPSRC under grant no EP/L015110/1. E.D.B. and F.R. were supported by the U.S. DOE, Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering. C.P. and P.J.W.M. acknowledge funding by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (“MiTopMat”—grant agreement No. 715730). This project was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grants No. PP00P2_176789).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Crystals were synthesized and characterized by F.R., E.D.B. (LaRhIn5), T.T., H.P. (Bi2O2Se) and N.K., C.S., C.F. (Cd3As2). The experiment design, FIB microstructuring and the magnetotransport measurements were performed by C.G., C.P., A.E., K.R.S., M.B., P.J.W.M. A.A. developed, applied and described the theoretical framework, and the analysis of experimental results has been done by C.G. and C.P. Band structures were calculated by F.F., S.Z., Q.W., O.Y., C.F., and Y.S. All authors were involved in writing the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Zhiqiang Mao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, C., Alexandradinata, A., Putzke, C. et al. Temperature dependence of quantum oscillations from non-parabolic dispersions. Nat Commun 12, 6213 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26450-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26450-1

This article is cited by

-

Magnetoresistive-coupled transistor using the Weyl semimetal NbP

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Low-frequency quantum oscillations in LaRhIn5: Dirac point or nodal line?

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Reply to: Low-frequency quantum oscillations in LaRhIn5: Dirac point or nodal line?

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Temperature-dependent Fermi surface probed by Shubnikov–de Haas oscillations in topological semimetal candidates DyBi and HoBi

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.