Abstract

The paradigm of Landau’s Fermi liquid theory has been challenged with the finding of a strongly interacting Fermi liquid that cannot be adiabatically connected to a non-interacting system. A spin-1 two-channel Kondo impurity with anisotropy D has a quantum phase transition between two topologically different Fermi liquids with a peak (dip) in the Fermi level for D < Dc (D > Dc). Extending this theory to general multi-orbital problems with finite magnetic field, we reinterpret in a unified and consistent fashion several experimental studies of iron phthalocyanine molecules on Au(111) that were previously described in disconnected and conflicting ways. The differential conductance shows a zero-bias dip that widens when the molecule is lifted from the surface (reducing the Kondo couplings) and is transformed continuously into a peak under an applied magnetic field. We reproduce all features and propose an experiment to induce the topological transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transport properties of single molecules in contact with metal electrodes are being extensively studied due to their potential use as active components of new electronic devices1,2,3. The paradigmatic Kondo effect (screening of molecule’s magnetic moment by conduction band electrons from metal) is ubiquitous in these systems and allows to control the current by different external parameters4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19.

The Kondo model (KM) for a molecule with spin S coupled to n conduction bands with different symmetries (channels) can be classified into three types: underscreened KM when the number of channels is too small to fully screen the spin, overscreened KM the other way, and compensated Kondo model (CKM) at the frontier. If there is only one way to build the spin, the frontier is at n = 2S20. The ground state of an underscreened molecule has a non-zero residual spin, and is a singular Fermi liquid with logarithmic corrections at low energies21,22. In particular, the case with S = n = 1 and residual spin 1/2 has been thoroughly investigated in molecular nanoscopic systems8,10,13,22,23. The overscreened model is a non-Fermi liquid that exhibits even more striking singular properties at low temperatures24,25,26. In general it was, however, strongly believed that the CKM always corresponds to an ordinary Fermi liquid (OFL) with regular low-energy behavior showing no non-analytical features. Nevertheless, it has been recently shown that this changes in the presence of an anisotropy term \(D{S}_{z}^{2}\) (refs. 27,28), which can drastically modify the ground state29,30,31,32,33.

In a Fermi liquid, the life-time of the quasiparticles with excitation energy ω scales as ω−2 close to the Fermi level at zero temperature, due to restrictions of phase space imposed by the Pauli principle, as first shown by L. Landau. This picture applies to all weakly interacting metals, but it may be broken in the presence of strong interactions. In particular, in the overscreened KM the quasiparticles are not well-defined even at the Fermi level, and in the underscreened KM they have a logarithmic dependence on ω for small ω21,22. The CKM with D = 0 (and the more general Anderson impurity model from which the CKM is derived) corresponds to an OFL. In this case, the Friedel sum rule relates the zero-temperature spectral density of the localized states at the Fermi level (ω = 0), as well as the zero-bias conductance, with the ground-state occupancy of these states34,35. As a consequence of the fractional occupancies per channel and spin in the Kondo regime, the spectral density has a Kondo peak at the Fermi level and the differential conductance dI/dV a zero-bias anomaly, i.e., a peak at voltage V = 0.

However, for the S = 1 CKM, this picture changes dramatically for D > Dc, where Dc is the critical anisotropy at which a topological quantum phase transition takes place. The spectral density at ω = 0 vanishes. In this case, the Friedel sum rule should be modified to allow for a non-zero value of a Luttinger integral IL, which has a topological character with a discrete set of possible values. A system in this regime is a Fermi liquid, yet it cannot be adiabatically connected to a non-interacting system. A closer scrutiny reveals the presence of a δ-peak exactly at the Fermi level in the imaginary part of the impurity self-energy, even though the low-energy scattering properties are not in any way anomalous and remain Fermi-liquid like. Such a ground state has been called a non-Landau Fermi liquid (NLFL)27,28. Previously, other strongly interacting models have been shown to display NLFL behavior for some parameters36,37.

A set of recent spectroscopic measurements performed on iron phthalocyanine (FePc) on Au(111) showed features reminiscent of those expected in NLFL systems. Two relevant experiments, performed before the theory for the NLFL system was developed15,18, reported basic characteristics of the system. Another more recent work19 is a particularly revealing detailed study of the magnetic field and temperature dependence. The existing interpretations proposed in these three works have serious deficiencies, as we discuss in the following. The NLFL theory accounts for the totality of the available results on FePc/Au(111), as well as for very recent experiments on MnPc/Au(111)38. A non-trivial extension of the existing theory to nonequivalent channels and finite magnetic fields presented in this work, was necessary to make these inferences. We also explain how to observe experimentally the topological quantum phase transition between a non-Landau and a Landau Fermi liquid.

Ab initio calculations15 show that the molecule in the “on top” position has a spin S = 1 formed by an electron in the 3d orbital of Fe with symmetry 3z2 − r2 and another shared between the degenerate π (xz, yz) Fe 3d orbitals. The former has larger hybridization with the Au substrate than the latter. The molecule can be described by a three-channel multi-orbital Anderson Hamiltonian, which is compensated39. The low-temperature differential conductance dI/dV measured by a scanning-tunneling microscope (STM) at zero magnetic field shows a broad peak of half-width ~240 K15,39 centered near V = 0 and superposed to it a narrow dip of half width ~2.7 K18, also centered near V = 0. This is exactly the shape expected in the NLFL regime of the anisotropic S = 1 CKM near the topological quantum phase transition at D = Dc27,28.

In the absence of these theoretical results, the first set of experiments15 was initially interpreted as a two-stage Kondo effect, with the larger energy scale corresponding to the stronger hybridized channel with 3z2 − r2 symmetry, and the smaller one due to the π orbitals15,39. The magnetic anisotropy was not taken into account. In general, as a consequence of interference effects, a dI/dV curve has a peak when the tip of the STM has a stronger hopping to the localized orbitals and a dip when the tip has instead a stronger hopping to the conduction electrons40,41 Therefore, this interpretation requires that the tip has a stronger (weaker) hybridization to the localized 3z2 − r2 (π) orbitals than to the conduction electrons of the same symmetry in addition to appropriate magnitudes of these hybridizations39. This seems unlikely.

The more recent experiment in which the molecule is raised from the surface, thereby reducing the hybridization of both localized states to the Au substrate, provides a stringent test of the above interpretation18. In the original interpretation based on the two-stage KM, both the peak and the dip should narrow and become steeper because both Kondo temperatures decrease. Instead, the experiments show clearly that the dip broadens and the peak flattens as the molecule is raised, in agreement with the expectations for the NLFL (see below). The theoretical explanation of the authors, further discussed in Note 6 of the supplemental material of their paper, is only qualitative and considers two contributions with many parameters.

The study of magnetic field effects19 unveils a surprising transformation of the narrow dip into a peak with increasing field strength B. This is a challenge to all existing theories so far. Based on ab initio calculations this effect has been interpreted as a rearrangement of the presence of localized orbitals of 3z2 − r2 and π symmetry near the Fermi level19. However, the difference between the energies of these states, of the order of 1 eV15, is much larger than the Zeeman energy of about 10T. Furthermore, many-body effects, which play a crucial role by shifting the relative positions of peaks in the density of states42 and in the Kondo effect43 have been altogether neglected. Therefore this explanation is very unlikely.

A similar effect of B has been observed in MnPc on Au(111) which has a similar occupancy of the 3d states as FePc. The authors of that work proposed an interpretation in terms of a quantum phase transition involving localized singlet states38. This transition, first discussed in the context of Tm impurities44 and more recently in quantum dots45,46, in particular with C60 molecules9,13,47,48, might be qualitatively consistent with the experiment (see Fig. 10 of ref. 48). However, this requires that the singlet be below the triplet by a few meV, while in fact the triplet is energetically favored by a Hund’s coupling of the order of 1 eV15.

In this work, we show that the behavior of FePc on Au(111) can be interpreted in a unified and consistent way in terms of an anisotropic S = 1 CKM in the parameter regime where the system is a NLFL. Using the numerical renormalization group (NRG) we solve the anisotropic S = 1 CKM for inequivalent channels in the presence of magnetic field and show that all phenomena observed in the above-mentioned experiments can be explained in a consistent and simple way. We underpin these calculations by generalizing the topological theory of the Friedel sum rule to the case in which channel and spin symmetries are broken. In particular, we show how the discontinuous transition at zero magnetic field governs the molecule’s excitation spectrum at finite fields, and why the evolution of the spectral line shape from a dip to a peak with increasing field is nevertheless continuous.

Results

Topological quantum phase transition and generalized Friedel sum rule

The essence of the atomic multi-orbital three-channel Anderson impurity model for FePc, which is difficult to handle numerically, is captured by the S = 1 two-channel KM with the Hamiltonian

where \({c}_{k\tau \sigma }^{{{{\dagger}}} }\) creates an electron in the Au substrate with wave vector k, pseudospin τ (representing a channel with symmetry 3z2 − r2 for τ = 1 and π for τ = −1) and spin σ. The first term describes the substrate bands, the second the Kondo exchange with the localized spin \(\overrightarrow{S}\) with exchange couplings J1 > J−1, the third term is the single-ion uniaxial magnetic anisotropy, and the last term is the effect of an applied magnetic field B. This model is equivalent to that used by Hiraoka et al.18 for large Hund’s coupling JH. As we show below, this model with three parameters explains all the experimental findings in FePc (While three channels participate in FePc39, including all of them in an NRG calculation would lead to a too fast increase in the Hilbert space as a function of the iteration rendering it impossible to obtain precise results). Its fundamental ingredients are well justified by ab initio and/or ligand field multiplet calculations: the existence of an almost integer electronic occupancy of the Fe ion18,49, the spin S = 1 of the FePc molecule15,18,19,50, the markedly different hybridizations of the \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) and dπ orbitals with the Au substrate15,18,51, and the presence of a non-negligible easy-plane magnetic anisotropy. We also consider that the gold conduction bands have a constant density of states, as first-principle calculations52 do not find any signature of sharp structures (with widths of the order of \({T}_{K}^{(1)}\) or less), that would modify sensibly the low energy Kondo physics, and we take the half band width W = 1 as the unit of energy.

It is worth to stress that, in this work, we are looking for a minimal model that, on one hand, allows to understand, in a unified and rather simple way, the low-energy behavior of FePc on Au(111), and that, on the other hand, is suitable for a numerically exact resolution at very low energies. More realistic and quantitative modeling for this and other transition metal phthalocyanines on metallic surfaces should take into account the full complexity of the 3d orbital manifold and the hybridization with the surface53,54,55,56,57.

The generalized Friedel sum rule is more conveniently discussed in terms of an auxiliary two-channel Anderson model HA from which HK can be derived in the limit of total local occupancy pinned to two (one electron in each orbital). This model is

where \({d}_{\tau \sigma }^{{{{\dagger}}} }\) creates a hole with energy ϵτ in the d orbital τ, \({n}_{\tau \sigma }={d}_{\tau \sigma }^{{{{\dagger}}} }{d}_{\tau \sigma }\), and nτ = ∑σnτσ. ϵτ and Uτ are the energy level and the Coulomb repulsion chosen such that ϵτ = −Uτ/2 to fix the occupancy in each orbital to one, while the hopping Vτ characterizes the tunneling between the localized and conduction states with symmetry τ. The Hund’s coupling JH is responsible for the formation of the S = 1 degree of freedom. The actual Coulomb interaction contains more terms27,28,57, but they are irrelevant for realistic parameters for FePc. The two models are related by the Schrieffer-Wolff transformation, such that \({J}_{\tau }\propto {V}_{\tau }^{2}/{U}_{\tau }\) (further details are given in Supplementary Note 1).

The impurity spectral function per orbital and spin, at the Fermi level and T = 0, is related to the quasiparticle scattering phase shift δτσ by34,58,59,60,61,62

where \({G}_{\tau \sigma }^{d}(\omega )\) is the impurity Green’s function \(\left\langle \left\langle {d}_{\tau \sigma };{d}_{\tau \sigma }^{{{{\dagger}}} }\right\rangle \right\rangle\) and Δτ = π∑k∣Vτ∣2δ(ω − εk) is the hybridisation strength, assumed independent of energy. According to the generalized Friedel sum rule, for wide constant unperturbed conduction bands one has

where \({{{\Sigma }}}_{\tau \sigma }^{d}(\omega )\) is the impurity self energy. Further details are given in Supplementary Note 2.

Until recently, based on the seminal perturbative calculation of Luttinger60, it was generally assumed that the Luttinger integrals Iτσ vanish (at least for B = 0). However, several cases are now known where Iτσ = ±π/222,27,28,36,37, yet the quasiparticle scattering phase shifts show no low-energy singularities. In particular, in our case for B = 0 and both orbitals equivalent, the four Iτσ = IL are equal by symmetry and IL has a topological character, being equal to 0 for D < Dc and π/2 for D > Dc27,28. In this case, Eqs. (3) and (4) imply that in the Kondo limit, where \(\left\langle {n}_{\tau \sigma }\right\rangle =1/2\), the spectral densities ρτσ(0) jump from ρ0 = 1/(πΔτ) for D < Dc to 0 for D > Dc. In the general case, when the channels are not equivalent and a magnetic field is present, we show in Supplementary Note 2 that the conservation laws imply that three topological quantities T, Tτ, Tσ can still be defined:

where σ = 1 (−1) for spin ↑ (↓). Although previous perturbative calculations assumed T = Tτ = Tσ ≡ 035, we find numerically that Tτ = Tσ ≡ 0, but T = 4I0 with I0 equal to either 0 or π/2. This allows us to write the individual Luttinger integrals in the general form

where α(D, B) is unknown. For B = 0, by symmetry \({I}_{{}_{\tau \uparrow }}={I}_{{}_{\tau \downarrow }}\) implying α = 0, and therefore not only T, Tτ and Tσ but also individual Luttinger integrals Iτσ have a topological character. The establishment of the general form in Eq. (6) and its numerical validation in the full parameter space of the model is one of the central results of this work.

We define the Kondo temperature \({T}_{K}^{(\tau )}\) as the temperature for which the contribution of channel τ to the zero-bias conductance for D = B = 0 falls to half of its zero-temperature value27. For the KM with channel symmetry [J−1 = J1 in Eq. (1)], the topological transition takes place for \({D}_{c} \sim 2.5{T}_{K}^{(1)}\)27, but Dc decreases with decreasing J−1/J1 ratio. In fact, for J−1 = 0 it is known to be zero23. In FePc experimentally D = 5 meV18 and \({T}_{K}^{(1)} \sim 20\) meV15. In Fig. 1 we represent the ratios \({D}_{c}/{T}_{K}^{(1)}\) and \({T}_{K}^{(-1)}/{T}_{K}^{(1)}\) for intermediate values of J−1/J1. The higher Kondo temperature \({T}_{K}^{(1)}\) changes only moderately as J−1/J1 varies, from 0.024 for J−1/J1 = 0.2 to 0.018 for J−1/J1 = 0.7 as a consequence of the competition between both channels39. Instead, Dc and particularly \({T}_{K}^{(-1)}\) have a strong dependence on J−1 in the range considered.

Ratio of the lower Kondo temperature \({T}_{K}^{(-1)}\) over the higher Kondo temperature \({T}_{K}^{(1)}\) (right scale, red symbols) and ratio of the critical anisotropy Dc over higher Kondo temperature (left scale, black squares), as a function of the smaller exchange coupling J−1 at constant larger coupling J1 = 0.4.

For comparison with the experiment, we take D/W = 0.01 (that means W ~ 500 meV52, a different choice of W does not affect the results in a sensitive manner) and fix J1 = 0.44 so that \({T}_{K}^{(1)} \sim 200\) K as in the experiment. The remaining parameter was fixed at J−1 = 0.22 so that the system is in the non-Landau phase (D > Dc), with the width of the dip near to the experimentally observed one (as described later). The resulting Kondo temperatures are \({T}_{K}^{(1)}=198\) K and \({T}_{K}^{(-1)}=1.77\) K, while Dc = 0.00950 ~ 4.7 meV ~ 55 K.

We choose as the corresponding parameters in the auxiliary Anderson model JH = 0.1, Uτ = 0.4, ϵτ = − Uτ/2, Δ1 = 0.06, Δ−1 = 0.0345. The two models have the same low-energy behavior if the results are rescaled in terms of \({T}_{K}^{(1)}\) or Dc.

Differential conductance at zero temperature in the absence of magnetic field

The s-like orbitals of the STM tip have a larger overlap with the 3z2 − r2 orbital of FePc than with the molecular π orbitals and the substrate conduction-band wave functions. Ab initio calculations for Co on Cu(111) confirm this picture63. For this reason, the dominant contribution to the experimental dI/dV spectra corresponds to the spectral density ρ1(ω) = ρ1↑(ω) + ρ1↓(ω) in channel τ = 1. This description is both simpler and more physically realistic than the assumptions underlying the alternative interpretations of the measured dI/dV from refs. 15,18,19. The observed weak asymmetry in the line shapes indicates that some interference effects involving conduction orbitals are present. They will be incorporated in the next subsections. Here they do not modify the essential features and the conduction orbitals become less important as the molecule is raised from the surface.

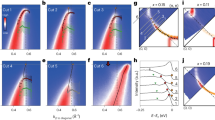

Our result for FePc in the relaxed geometry corresponds to the black full line of Fig. 2 and reproduces the main features of the observed differential conductance except for some asymmetry in the experiments, which we neglect in this subsection as explained above. As the molecule is raised from the substrate by the attractive force of the STM tip, the Kondo coupling to the substrate is reduced18. We assume that both exchange coupling constants Jτ are reduced by the same factor f because the same power-law dependence of the tunneling parameters Vτ with the distance is expected between the localized 3d orbitals and the extended conduction states64. As this factor f decreases from 1, the spectral density flattens and the dip broadens so that the line-shape becomes similar to that observed in single-channel Kondo systems with magnetic anisotropy30,31. The exact same trend is observed experimentally18. For very small f, there should be two sharp steps at the unrenormalized threshold for inelastic spin-flip excitations (ω = ±D); in our calculations they are overbroadened due to technical reasons that limit the resolution of the NRG at large energies65. A detailed comparison with experiment is contained in Supplementary Note 4.

The gradual decoupling from the surface is modeled through equal reduction of both exchange coupling constants by a factor f. The model parameters are J1 = 0.44 × f, J−1 = 0.22 × f and D = 0.01. See Supplementary Fig. 3 for a direct comparison with experiments.

It would be interesting to push the STM tip against the molecule and tune from the tunneling to the contact regime. In this case the factor f is expected to increase beyond 166,67,68, driving the system through the topological quantum phase transition to the OFL regime. This would be signaled by the sudden transformation of the dip into a peak of similar amplitude, i.e., compared to the baseline density of states, the height of the peak just after the transition should be similar as the depth of the dip just before the transition. This is an important prediction of our theory that should be the target of future experiments (although in the contact regime, the widths of dI/d(eV) and ρ1(ω) may differ due to non-equilibrium effects68).

Temperature dependence

Assuming that the molecule is at equilibrium with the substrate, the observed differential conductance is proportional to

where \({f}^{\prime}(\omega )\) is the derivative of the Fermi function and ρh(ω) is the density of a mixed state which contains the orbitals that have a non-vanishing hopping to the STM tip with an amplitude proportional to the hopping69. In the present case we take only two contributions: the \(3{d}_{3{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) and the conduction states of the same symmetry. Assuming that the latter corresponds to a flat band in the absence of hybridization with the localized states, one has70

where q is proportional to the amplitude between the STM tip and the conduction electrons of 3z2 − r2 symmetry and is responsible of the observed asymmetry in the line shape. We take q = 0.4, a similar value as taken in refs. 15,71, although the results do not show a high sensitivity to q.

The temperature dependence of the dip is shown in Fig. 3. The half width of the dip at T = 0.4 K, taken at the average between the minimum dI/dV and the relative maximum near eV = 0.001 is 3.1 K, near the reported one18 2.7 K. With increasing temperature, the low-energy dip in the spectral density decreases and eventually disappears, as expected. The effect is much more pronounced at low temperatures. The same trend is observed in the experiment19. The inset shows the results in a scale of energies similar to that of the experiment (Fig. 2 of ref. 19). See Supplementary Note 4.

Magnetic field dependence

The effect of the magnetic field on the dI/dV spectra reported in ref. 19 is most striking. A moderate field of B = 11 T ~ 14 K readily transforms the dip into a peak with a transition near 3 to 4 T. This phenomenon is fully reproduced in our calculations, see Fig. 4. For larger fields B > 20 T (4.65 × 10−3) a dip is expected to form at the Fermi level as a consequence of the Zeeman splitting between ρ1↑(ω) and ρ1↓(ω). For the comparison with experiment, we have taken the giromagnetic factor g = 2, inside the range of uncertainty of previously reported values (see supplemental material of refs. 18,19). A detailed comparison with the experiment is contained in Supplementary Note 4.

The interpretation of this spectral transformation is highly non trivial. A field-induced topological transition from a NLFL to an OFL would result in an abrupt change from a dip into a peak, clearly at odds with the continuous evolution shown in Fig. 4 and observed in the experiment. To shed more light on this discrepancy, we investigated the Luttinger integrals entering Eq. (4). This study was performed in terms of the equivalent auxiliary Anderson model (see Methods) and interpreted using Eq. (5).

In Fig. 5a we show the evolution of the phase shifts δτσ with increasing field for D/Dc > 1 (as in Figs. 2–4). For B = 0, the four-phase shifts δτσ = 0 (mod. π) and, therefore, the corresponding four Fermi-level spectral densities ρτσ(0) = 0 [see Eq. (3)]. As B increases, the phase shifts for the π molecular orbital (τ = −1) change only moderately (below 0.12π) and, therefore, the corresponding spectral densities continue to exhibit a dip at the Fermi level. By contrast, the phase shifts that correspond to the 3z2 − r2 molecular orbital (τ = 1) change considerably, reaching the values ±π/2 for B/Dc ~ 0.8. At this point the spectral densities ρ1σ(0) reach their maximum value. Since ρ1σ are the main contribution to the differential conductance, the above mechanism explains the transformation from a dip into a peak displayed in Fig. 4. Further increase of B would lead to a Zeeman splitting, as expected for \(B\,\gtrsim\, {T}_{K}^{(1)}\): the peak in ρ1↑(ω) displaces to lower energies and that in ρ1↓(ω) to higher energies, so that ρ1σ(0) decrease for both σ, which corresponds to ∣δ1σ∣ increasing beyond π/2 in agreement with Eq. (3).

The changes in the spectral densities at the Fermi level with the magnetic field should lead to important spatial variations of the differential conductance at a small bias. For B = 0 in the Kondo limit (integer total occupancy), the spectral densities of the localized orbitals with π and 3z2 − r2 symmetry vanish at the Fermi surface and the space variation is dominated by conduction states. As B increases, the influence of π orbitals remains small but that of the cylindrical symmetric 3z2 − r2 orbitals increase considerably and therefore, an evolution to a more circular shape is expected, as observed experimentally19.

The topological properties under an applied magnetic field are very peculiar. For B = 0 and D > Dc, there is a pole in the self-energy Σ(ω) on the real axis at ω = 0. An infinitesimal B displaces this pole away from ω = 0, as it is shown in Supplementary Note 3. I0 drops to zero and the system becomes an OFL. However, at the same time α jumps to π/2 (−π/2) for infinitesimal positive (negative) B. See Fig. 6. As a result, in both cases the Luttinger integral I−1σ for the majority spin [that is ↑ (↓) for positive (negative) B] remains π/2, while I1σ jumps from π/2 to −π/2, see Eq. (6). This jump in π does not affect any physical properties which are continuous across B = 0, as expected and in-line with the “modulo π ambiguity” in the definition of the scattering phase shifts58. The Luttinger integrals for minority spin are obtained by interchanging the orbital index.

Phase diagram of the auxiliary Anderson model as a function of the magnetic field B and the magnetic anisotropy D. Along the green half line B = 0, D > Dc, the system is a non-Landau Fermi liquid (NLFL) with the topological value I0 = π/2, and the non-topological parameter α = 0. For an infinitesimal B both quantities jump as indicated in the figure, yet all physical quantities are continuous. For D < Dc, I0 = 0, and α is continuous across B = 0, where its value crosses zero (orange segment). The insets show the low-energy region around the Fermi level: regular Fermi liquid (orange frame) and NLFL (green frame) at zero magnetic field, as well as weakly spin-polarized Fermi liquids at moderate magnetic field (white and pink frame).

For D < Dc, I0 and α are continuous as functions of B, and both are equal to zero for B = 0. In fact, in the whole (D, B) plane, I0 ≡ 0 and α is continuous except on the half-line B = 0, D > Dc. This line is, hence, a branch-cut for α (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the point D = Dc, B = 0 may be considered as a logarithmic singularity for the function α(D, B) viewed as a function in the complex plane with the argument z = D + iB. In Fig. 7 we display α as a function of both D/Dc and B/Dc. As explained above for B → 0+, α(D, B = 0) = (π/2)θ(D − Dc), where θ(x) is the step function. For small non-zero B, α(D, B) still resembles this step function. In fact, \(\alpha (D,B) \sim -\frac{1}{2}{{{{{{{\rm{Im}}}}}}}}{{{{{{\mathrm{ln}}}}}}}\,[{D}_{c}-D-iB]\). As ∣B∣ further increases, α(D) decreases markedly for D > Dc. For ∣B∣ ≫ Dc, α is small for all D and as a consequence also the four Luttinger integrals are small.

As ∣B∣ increases, the occupancies \(\langle {n}_{\tau \uparrow }\rangle\) increase (Fig. 5b), with the effect of increasing δτ↑ [Eq. (4)]. For δ−1↑, this effect is largely compensated by the decrease in α, leading to a small overall variation of the phase shift. Instead, for δ1↑ both effects add up and δ1↑ has a marked increase, which is then reflected in the transformation of the dip into a peak. For spin ↓ the effects are opposite.

Discussion

The ability to flip the differential conductance between low and high values by tuning some external parameter is of tremendous practical importance in molecular electronics for switching device applications. Recently a topological quantum phase transition has been found in a spin-1 KM with two degenerate channels and single-ion magnetic anisotropy, in which the zero-bias differential conductance and the spectral density at zero temperature jump from their maximum possible values to zero as the longitudinal single-ion anisotropy D is increased beyond a threshold value Dc27,28. By generalizing the theory of such topological transitions to nonequivalent channels and finite magnetic field, we have for the first time conclusively identified FePc/Au(111) as an experimental realization of this phenomenon, since our approach provides a unified description of the totality of experimental observations. The main difficulty in this identification is that for D > Dc the system is an unconventional Fermi liquid that cannot be adiabatically connected to a non-interacting system by turning off the interactions27,28,36,37. The corresponding concept of a NLFL remains largely unfamiliar to most of the physics community. In the NLFL, the Friedel sum rule has to be generalized by introducing a topological quantity that has been previously overseen, even though it leads to a dramatic drop in spectral density and differential conductance for D > Dc.

By formulating a general theory of the topological aspects of the Friedel sum rule that incorporates the effects of broken channel and spin symmetries, fully corroborated by numerical calculations for a model Hamiltonian, we reliably established that FePc on Au(111) behaves as a NLFL. With a single set of parameters we explained three key experiments on the differential conductance of this system15,18,19. The sole assumption (i.e., that the scanning tunneling microscope senses mainly the 3d orbital of Fe with 3d2 − r2 symmetry) is simple, physically realistic, and consistent with ab initio calculations63.

The same model also explains the recent experiments for MnPc on Au(111)38, which exhibit a dependence on magnetic field with qualitative features similar to those in FePc on Au(111). Alternative explanations proposed for these experiments are questionable or contradict well established facts, like the role of Hund rules in defining ground-state multiplets.

While a moderate magnetic field B of the order of 10 T leads to a continuous transition from very small to very high zero-bias conductance, we predict an abrupt transition for B = 0 if the tip is pressed against the molecule changing the regime of the system from the tunneling to the contact one, thereby increasing the Kondo temperatures66,67,68.

Methods

The numerical calculations were performed with the NRG Ljubljana72,73 implementation of the NRG method65,74 using the separate conservation of the isospin (axial charge) in each channel τ, as well as the conservation of the z-component of the total spin, i.e., SU(2) × SU(2) × U(1) symmetry. The calculations for the KM were performed with the discretization parameter Λ = 4 with the broadening parameter α = 0.8 for Figs. 3 and 4. For Fig. 2 the values of α used were 0.1 for f ≤ 0.1, 0.2 for f = 0.6 and 0.7, 0.4 for f = 0.8 and 0.9 and 0.6 for f = 1. The calculations for the Anderson model have been performed using Λ = 3 with the broadening parameter α = 0.3. We kept up to 10000 multiplets (or up to cutoff 10 in energy units) in the truncation, averaging over Nz = 4 different discretization meshes. The spectral functions were computed using the complete Fock space algorithm75, and the resolution for the Anderson model was improved using the “self-energy trick”76.

For large interaction U, the value of Dc calculated with the Anderson model Eq. (2) coincides with that obtained from the corresponding KM. However, for example for U = 4, we obtain that the phase shift modulo π calculated directly from the NRG spectrum and that obtained the using the generalized Friedel sum rule Eq. (4) deviate by up to 0.1π for large B. This is due to the fact that Eq. (4) were simplified for the case in which the conduction band width (which we have taken as 2W = 2) is much larger than all other energies involved (the “wide-band limit”), in such a way that the number of conduction electrons per channel is not modified by the addition of the impurity34. To avoid this difficulty, we have used U = 0.4 in the calculations with the Anderson model. In this case the maximum deviation between both phase shifts is below 0.02π and the critical anisotropy is reduced by a factor of the order of 6. However, the physical properties are very similar for the same D/Dc and B/Dc.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository under accession code https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5506654. The data include figure sources and model definition files for the NRG solver.

Code availability

The NRG calculations presented in this work have been performed with the NRG Ljubljana code. The source code is available from GitHub, https://github.com/rokzitko/nrgljubljana. A snapshot of the specific version used (8f90ac4) has been posted on Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4841076.

References

Aradhya, S. V. & Venkataraman, L. Single-molecule junctions beyond electronic transport. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 399 (2013).

Cuevas, J. C. & Scheer, E. Molecular Electronics: An Introduction to Theory and Experiment. (World Scientific, Singapore, 2010).

Evers, F., Korytár, R., Tewari, S. & van Ruitenbeek, J. Advances and challenges in single-molecule electron transport. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 035001 (2020).

Liang, W., Shores, M. P., Bockrath, M., Long, J. R. & Park, H. Kondo resonance in a single-molecule transistor. Nature 417, 725 (2002).

Yu, L. H. et al. Kondo resonances and anomalous gate dependence in the electrical conductivity of single-molecule transistors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 256803 (2005).

Leuenberger, M. N. & Mucciolo, E. R. Berry-phase oscillations of the Kondo effect in single-molecule magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 126601 (2006).

Osorio, E. A. et al. Electronic excitations of a single molecule contacted in a three-terminal configuration. Nano. Lett. 7, 3336 (2007).

Parks, J. J. et al. Tuning the Kondo effect with a mechanically controllable break junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 026601 (2007).

Roch, N., Florens, S., Bouchiat, V., Wernsdorfer, W. & Balestro, F. Quantum phase transition in a single-molecule quantum dot. Nature 453, 633 (2008).

Roch, N., Florens, S., Costi, T. A., Wernsdorfer, W. & Balestro, F. Observation of the underscreened Kondo effect in a molecular transistor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 197202 (2009).

Osorio, E. A. et al. Electrical manipulation of spin states in a single electrostatically gated transition-metal complex. Nano. Lett. 10, 105 (2010).

Parks, J. J. et al. Mechanical control of spin states in spin-1 molecules and the underscreened Kondo effect. Science 328, 1370 (2010).

Florens, S. et al. Universal transport signatures in two-electron molecular quantum dots: gate-tunable Hund’s rule, underscreened Kondo effect and quantum phase transitions. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 23, 243202 (2011).

Vincent, R., Klyatskaya, S., Ruben, M., Wernsdorfer, W. & Balestro, F. Electronic read-out of a single nuclear spin using a molecular spin transistor. Nature (London) 488, 357 (2012).

Minamitani, E. et al. Symmetry-driven novel Kondo effect in a molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 086602 (2012).

Heinrich, B. W., Braun, L., Pascual, J. I. & Franke, K. J. Tuning the magnetic anisotropy of single molecules. Nano. Lett. 15, 4024 (2015).

Ormaza, M. et al. Controlled spin switching in a metallocene molecular junction. Nat. Commun. 8, 1974 (2017).

Hiraoka, R. et al. Single-molecule quantum dot as a Kondo simulator. Nat. Commun. 8, 16012 (2017).

Yang, K. et al. Tunable giant magnetoresistance in a single-molecule junction. Nat. Commun. 10, 1038 (2019).

Nozières, P. & Blandin, A. Kondo effect in real metals. J. Physique 41, 193 (1980).

Mehta, P., Andrei, N., Coleman, P., Borda, L. & Zaránd, G. Regular and singular Fermi-liquid fixed points in quantum impurity models. Phys. Rev. B 72, 014430 (2005).

Logan, D. E., Wright, C. J. & Galpin, M. R. Correlated electron physics in two-level quantum dots: Phase transitions, transport, and experiment. Phys. Rev. B 80, 125177 (2009).

Cornaglia, P. S., Roura-Bas, P., Aligia, A. A. & Balseiro, C. A. Quantum transport through a stretched spin-1 molecule. Europhys. Lett. 93, 47005 (2011).

Potok, R. M., Rau, I. G., Shtrikman, H., Oreg, Y. & Goldhaber-Gordon, D. Observation of the two-channel Kondo effect. Nature 446, 167 (2007).

Iftikhar, Z. et al. Two-channel Kondo effect and renormalization flow with macroscopic quantum charge states. Nature 526, 233 (2015).

Zhu, L. J., Nie, S. H., Xiong, P., Schlottmann, P. & Zha, J. H. Orbital two-channel Kondo effect in epitaxial ferromagnetic L10 -MnAl films. Nature Commun. 7, 10817 (2016).

Blesio, G. G., Manuel, L. O., Roura-Bas, P. & Aligia, A. A. Topological quantum phase transition between Fermi liquid phases in an Anderson impurity model. Phys. Rev. B 98, 195435 (2018).

Blesio, G. G., Manuel, L. O., Roura-Bas, P. & Aligia, A. A. Fully compensated Kondo effect for a two-channel spin S = 1 impurity. Phys. Rev. B 100, 075434 (2019).

Otte, A. F. et al. The role of magnetic anisotropy in the Kondo effect. Nat. Phys. 4, 847 (2008).

Žitko, R., Peters, R. & Pruschke, T. Properties of anisotropic magnetic impurities on surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 78, 224404 (2008).

Žitko, R. & Pruschke, T. Many-particle effects in adsorbed magnetic atomswith easy-axis anisotropy: the case of Fe on theCuN/Cu(100) surface. New J. Phys. 12, 063040 (2010).

DiNapoli, S. et al. Non–Fermi liquid behaviour in transport through Co-doped Au chains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 196402 (2013).

Oberg, J. C. et al. Control of single-spin magnetic anisotropy by exchange coupling. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 64 (2013).

Langreth, D. C. Friedel sum rule for Anderson’s Model of localized impurity states. Phys. Rev. 150, 516 (1966).

Yoshimori, A. & Zawadowski, A. Restricted Friedel sum rules and Korringa relations as consequences of conservation laws. J. Phys. C 15, 5241 (1982).

Curtin, O. J., Nishikawa, Y., Hewson, A. C. & Crow, D. J. G. Fermi liquids and the Luttinger theorem. J. Phys. Commun. 2, 031001 (2018).

Nishikawa, Y., Curtin, O. J., Hewson, A. C. & Crow, D. J. G. Magnetic field induced quantum criticality and the Luttinger sum rule. Phys. Rev. B 98, 104419 (2018).

Guo, X. et al. Gate tuning and universality of Two-stage Kondo effect in single molecule transistors. Nat. Commun. 12, 1566 (2021).

Fernández, J., Roura-Bas, P., Camjayi, A. & Aligia, A. A. Two-stage three-channel Kondo physics for an FePc molecule on the Au(111) surface. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 30, 374003 (2018). Corrigendum J. Phys. Condens. Matter 31, 029501 (2018).

Újsághy, O., Kroha, J., Szunyogh, L. & Zawadowski, A. Theory of the Fano resonance in the STM tunneling density of states due to a single Kondo impurity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2557 (2000).

Aligia, A. A. & Lobos, A. M. Mirages and many-body effects in quantum corrals. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 17, S1095 (2005).

Allerdt, A., Hafiz, H., Barbiellini, B., Bansil, A. & Feiguin, A. E. Many-body effects in porphyrin-like transition metal complexes embedded in graphene. Appl. Sci. 10, 2542 (2020).

Hewson, A. C. The Kondo Problem to Heavy Fermions. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1997).

Allub, R. & Aligia, A. A. Ground state and magnetic susceptibility of intermediate-valence Tm impurities. Phys. Rev. B 52, 7987 (1995).

Hofstetter, W. & Schoeller, H. Quantum phase transition in a multilevel dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 016803 (2001).

Paaske, J. et al. Non-equilibrium singlet–triplet Kondo effect in carbon nanotubes. Nat. Phys. 2, 460–464 (2006).

Roura-Bas, P. & Aligia, A. A. Nonequilibrium transport through a singlet-triplet Anderson impurity. Phys. Rev. B 80, 035308 (2009).

Roura–Bas, P. & Aligia, A. A. Nonequilibrium dynamics of a singlet–triplet Anderson impurity near the quantum phase transition. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 22, 025602 (2010).

Stepanow, S. et al. Mixed-valence behavior and strong correlation effects of metal phthalocyanines adsorbed on metals. Phys. Rev. B 83, 220401(R) (2011).

Mabrouk, M., Hayn, R. & Chaabane, R. B. Adsorption of iron phthalocyanine on a Au(111) surface. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 94, 1704 (2020).

Kezilebieke, S., Amokrane, A., Abel, M. & Bucher, J.-P. Hierachy of chemical bonding in the synthesis of Fe-phthalocyanine on metal surfaces: a local spectroscopy approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 3175 (2014).

Gao, L. et al. Site-specific Kondo effect at ambient temperatures in iron-based molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 106402 (2007).

Mugarza, A. et al. Electronic and magnetic properties of molecule-metal interfaces: Transition-metal phthalocyanines adsorbed on Ag(100). Phys. Rev. B 85, 155437 (2012).

Jacob, D., Soriano, M. & Palacios, J. J. Kondo effect and spin quenching in high-spin molecules on metal substrates. Phys. Rev. B 88, 134417 (2013).

Kügel, J. et al. Relevance of hybridization and filling of 3d orbitals for the Kondo effect in transition metal phthalocyanines. Nano Lett. 14, 3895 (2014).

Kügel, J. et al. State identification and tunable Kondo effect of MnPc on Ag(001). Phys. Rev. B 91, 235130 (2015).

Valli, A. et al. Kondo screening in Co adatoms with full Coulomb interaction. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033432 (2020).

Taylor, J. R. Scattering Theory. (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1972).

Friedel, J. XIV. The distribution of electrons round impurities in monovalent metals. Philos. Mag. 43, 153 (1952).

Luttinger, J. M. Fermi surface and some simple equilibrium properties of a system of interacting fermions. Phys. Rev. 119, 1153 (1960).

Langer, J. S. & Ambegaokar, V. Friedel sum rule for a system of interacting electrons. Phys. Rev. 121, 1090 (1961).

Shiba, H. The Korringa relation for the impurity nuclear spin-lattice relaxation in dilute Kondo alloys. Prog. Theor. Phys. 54, 967 (1975).

Tacca, M. S., Jacob, T. & Goldberg, E. C. Surface states influence in the conductance spectra of Co adsorbed on Cu(111). Phys. Rev. B 103, 245419 (2021).

Harrison, W. A. Electron Structure and the Properties of Solids. (Freeman, San Francisco, 1980).

Bulla, R., Costi, T. & Pruschke, T. The numerical renormalization group method for quantum impurity systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 395 (2008).

Choi, D.-J. et al. Kondo resonance of a Co atom exchange coupled to a ferromagnetic tip. Nano Lett. 16, 6298 (2016).

Choi, D.-J., Abufager, P., Limot, L. & Lorente, N. From tunneling to contact in a magnetic atom: the non-equilibrium Kondo effect. J. Phys. Chem. 146, 092309 (2017).

Pérez Daroca, D., Roura-Bas, P. & Aligia, A. A. Relation between width of zero-bias anomaly and Kondo temperature in transport measurements through correlated quantum dots: effect of asymmetric coupling to the leads. Phys. Rev. B 98, 245406 (2018).

Fernández, J., Roura-Bas, P. & Aligia, A. A. Theory of differential conductance of Co on Cu(111) Including Co s and d orbitals, and surface and bulk Cu states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 046801 (2021).

Žitko, R. Kondo resonance lineshape of magnetic adatoms on decoupling layers. Phys. Rev. B 84, 195116 (2011).

Tsukahara, N. et al. Evolution of Kondo resonance from a single impurity molecule to the two-dimensional lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 187201 (2011).

Žitko, R. & Pruschke, T. Energy resolution and discretization artifacts in the numerical renormalization group. Phys. Rev. B 79, 085106 (2009).

NRG Ljubljana, https://github.com/rokzitko/nrgljubljana and http://nrgljubljana.ijs.si/.

Wilson, K. G. The renormalization group: critical phenomena and the Kondo problem. Rev. Mod. Phys. 47, 773 (1975).

Peters, R., Pruschke, T. & Anders, F. B. A numerical renormalization group approach to Green’s functions for quantum impurity models. Phys. Rev. B 74, 245114 (2006).

Bulla, R., Hewson, A. C. & Pruschke, T. Numerical renormalization group calculations for the self-energy of the impurity Anderson model. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 10, 8365 (1998).

Acknowledgements

R.Ž. acknowledges the support of the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) under P1-0044. G.G.B. and L.O.M. are supported by PIP2015 No. 364 of CONICET. A.A.A. is supported by PIP 112-201501-00506 of CONICET, and PICT 2017-2726 and PICT 2018-01546 of the ANPCyT, Argentina.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.A. and L.O.M. conceived the project, R.Ž. and G.G.B. performed the NRG calculations. A.A.A., R.Ž., and L.O.M. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Giorgio Sangiovanni, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Žitko, R., Blesio, G.G., Manuel, L.O. et al. Iron phthalocyanine on Au(111) is a “non-Landau” Fermi liquid. Nat Commun 12, 6027 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26339-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26339-z

This article is cited by

-

Quantum study of symmetrical/asymmetrical charge and energy transfer in a simple candidate molecular switch

Structural Chemistry (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.