Abstract

A triplon refers to a fictitious particle that carries angular momentum S=1 corresponding to the elementary excitation in a broad class of quantum dimerized spin systems. Such systems without magnetic order have long been studied as a testing ground for quantum properties of spins. Although triplons have been found to play a central role in thermal and magnetic properties in dimerized magnets with singlet correlation, a spin angular momentum flow carried by triplons, a triplon current, has not been detected yet. Here we report spin Seebeck effects induced by a triplon current: triplon spin Seebeck effect, using a spin-Peierls system CuGeO3. The result shows that the heating-driven triplon transport induces spin current whose sign is positive, opposite to the spin-wave cases in magnets. The triplon spin Seebeck effect persists far below the spin-Peierls transition temperature, being consistent with a theoretical calculation for triplon spin Seebeck effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spin Seebeck effects1 (SSEs) refer to the generation of a spin current, a flow of spin angular momentum of electrons, from a temperature gradient applied to a bilayer system comprising a magnet and heavy metal such as Pt. Spin current in the magnet propagates along the temperature gradient and reaches the heavy metal2, in which spin current can be detected as a voltage signal via the inverse spin-Hall effect (ISHE)3,4. The SSE has been observed in various insulating systems, in which parasitic thermal effects originating from itinerant electrons can be eliminated. Some types of spin carriers including magnons in magnets5,6,7,8, paramagnons9, antiferromagnetic magnons7,8, and spinons in a spin liquid10,11 have been demonstrated for different mechanisms of the SSE.

Among quantum spin systems without magnetic order, dimerized magnets spin systems occupy an important position, in which two neighboring spins are frozen as S = 0 singlets in the ground state. The elementary spin excitations are S = 1 triplet states, called a triplon. A triplon has been expected to carry spin angular momentum.

In this work, we report the observation of spin current in CuGeO3, carried by triplons in terms of longitudinal SSE measurements. A typical spin-dimer system is a spin-Peierls material CuGeO3, which contains one-dimensional spin-1/2 chains with antiferromagnetic exchange interaction for nearest-neighbor spins. In the spin chain, with lowering the temperature, neighboring spins dimerizes to form a spin-gapped phase; the transition is called a spin Peierls (SP) transition12. Below the SP transition temperature TSP, the chain distorts so that the distances between neighboring spins change alternately. The bond-alternating exchange interaction causes neighboring spins to dimerize to reduce the total energy, creating a gap in the spin excitation energy spectrum. CuGeO3 is the firstly discovered inorganic system that exhibits a SP transition13. High-quality single crystals of CuGeO3 are easier to obtain than organic SP materials and CuGeO3 has typically been used to study spin excitations in SP systems14.

Results

Sample structure and the concept of the study

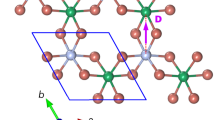

Figure 1a shows the crystal structure of CuGeO3. One-dimensional Cu2+ spin (S = 1/2) chains are aligned along the c-axis, as illustrated as dotted lines. The nearest-neighbor exchange interaction along the c-axis is Jc ~ 120 K, much greater than the interchain exchange coupling15, Jb ~ 0.1Jc, and Ja ~ −0.01Jc along the b and a-axis, respectively. CuGeO3 is thus considered as a quasi-one-dimensional spin system. As the temperature T decreases below the SP transition temperature TSP ~ 14.5 K, the lattice of CuGeO3 is spontaneously distorted to form a bond alternating configuration16. The spin configuration in the ground state is shown schematically in Fig. 1b, where all spins are frozen as dimerized S = 0 singlets. The elementary spin excitation from the ground state is an S = 1 triplon17, also shown in Fig. 1b. The excitation gap of a triplon is estimated to be ~23 K from ESR18 and neutron scattering15,19,20 experiments.

a Crystalline structure of CuGeO3. The Cu spin chains are shown as dotted lines. Spin-1/2 spin chains along the c-axis in CuGeO3 are formed by staking CuO2 chains. Jc and Jb denote the exchange interactions along the c and b-axis, respectively. b When temperature (T) falls down to the SP transition temperature TSP, CuGeO3 undergoes a SP transition. After the transition, the Cu spins dimerize and the ground state becomes a spin singlet state (\((\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle -\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) with S = 0). Elementary excitation in the SP phase is a triplon with S = 1. c Schematic band structure of triplon in CuGeO319,21. Three triplet states (\(\left|\downarrow \downarrow \right\rangle\), \((\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle +\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) and \(\left|\uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle\)) are threefold degenerated at zero fields. By applying a magnetic field (H), the Zeeman effect lift the degeneracy. d The ground state and excitation state of a ferromagnet. Elementary excitation is a magnon with S = 1. The magnons reduce the magnetization (M) along the magnetic field (H) as δSz. e T dependence of magnetic susceptibility (χ) of CuGeO3 under an applied magnetic field of 1 T along the b-axis. The SP transition temperature TSP is illustrated as the arrow in the figure. f Magnetic field - temperature (H - T) spin phase diagram for the CuGeO3 sample obtained from the M(H) and χ(T) measurement results. The diamond symbols represent data taken from a previous study24. The dotted curves are guide for the eyes.

Based on the previous neutron scattering results19 and theoretical calculations21, the dispersion relation of triplons along the c-axis is sketched in Fig. 1c. In the absence of a magnetic field, μ0H = 0, the triplon states are threefold degenerated: \(\left|\uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle\), \((\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle +\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\), and \(\left|\downarrow \downarrow \right\rangle\) corresponding to states with different spin quantum numbers, Sz = 1, 0, and −1, respectively. When a magnetic field is applied, the degenerated triplet bands split into three due to the Zeeman effect, where the triplet state with the parallel spin direction to H, \(\left|\uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle\), has the lowest energy18,19,20. The \(\left|\uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle\) state thus exhibits the highest probability for thermal excitation, while \(\left|\downarrow \downarrow \right\rangle\) the lowest. Driven by a thermal gradient, different occupancy among the three states can result in a flow of a net spin angular momentum in an external magnetic field: triplon SSE. One of the key features of the triplon SSE is that it should exhibit the opposite sign of ISHE signal to the magnon SSE in ferri- and ferro- magnets. This is because triplon spin currents are carried by excitation with the parallel spin direction to the external field; while magnons carry antiparallel spins to the external field, as shown in Fig. 1d. In these two systems, the interfacial accumulated spins in the magnets are injected into the metal (Pt) through the interfacial exchange interaction. Since the exchange interaction conserves the spin angular momentum, the spin current in the metal has the same polarization direction as that in the magnets. As a result, the sign of ISHE in the triplon SSE is opposite to that in the magnon SSE. Our theoretical calculation based on the tunnel spin current (see Supplementary Note G3 for details) suggests that the opposite sign of triplon SSE to magnon SSE is a universal property for gapped triplet-spin systems.

Material characterization and measurement setup

First, we measured the temperature dependence of magnetization, M(T), for the CuGeO3 sample. Figure 1e shows the magnetic susceptibility χ(T) = M(T)/H measured at μ0H = 1 T ∥b-axis. When T is decreased from 20 K, χ exhibits a sudden drop at the SP transition temperature TSP ~ 14.5 K and rapidly decreases towards zero. This indicates that Cu spins along the spin chain (∥c-axis) form dimers and a spin gap develops below TSP. By measuring χ(T) at different values of H (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for details), we obtain the H–T spin-phase diagram of the CuGeO3 sample in Fig. 1f. In the phase diagram, for large H in the SP phase, CuGeO3 undergoes another phase transition into a magnetic phase at a transition field, Hm, where magnetization is recovered by forming a spin soliton lattice in the chain22. The transition can be confirmed as a sudden jump of magnetization as a function of fields23 (also see Supplementary Fig. 1). The obtained phase diagram is in good agreement with a previous study24.

The experimental setup for the SSE measurement and the sample used in the present study are shown in Fig. 2a, b. A trilayer structure comprising a Pt wire for ISHE, an insulating SiO2 layer, and an Au wire as a heater was fabricated on the top of the (001) plane of a CuGeO3 single crystal. The spin Seebeck voltage signal VSSE in the Pt wire is measured by a lock-in method, where an a.c. current is applied to the Au layer under an in-plane magnetic field, H, applied perpendicular to the Pt wire. We normalize VSSE by the heater power and the detector resistance as \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}={V}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}/({P}_{{{{{{{{\rm{Au}}}}}}}}}\cdot {R}_{{{{{{{{\rm{Pt}}}}}}}}})\).

a Experimental setup for the SSE measurement. Temperature gradient (∇T) is applied by using an Au heater electrically insulated from the Pt layer by a SiO2 film. An a.c. current is applied to the Au heater and SSE voltage in the Pt is measured with a lock-in amplifier as the second harmonic voltage V2f. b An optical micrograph for a on-chip SSE device made on the top of CuGeO3. c, d The magnetic field (H) dependence of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) (the SSE signal normalized to the heating power and the detector resistance) for the CuGeO3/Pt sample at 15 and 2 K, respectively. e, f \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}(H)\) measured for Y3Fe5O12/Pt at 2 and 15 K.

Observation of the triplon SSE

The magnetic field dependence of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) at some selected temperatures is shown in Fig. 2c, d. At 15 K, just above TSP ~ 14.5 K, no H-dependent signal is recognized. Most notably, a clear voltage signal appears when T is decreased down to 2 K. The signal is an odd function of H, reflecting the symmetry of the ISHE25. The sign of the \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) signal is opposite to that of the magnon-mediated SSE26,27, which is confirmed in a similar setup for a ferrimagnetic insulator Y3Fe5O12/Pt sample in Fig. 2e, f. The result indicates that spin current carriers in these two systems have different spin polarization directions with respect to H, consistent with the triplon-current senario. Note that the sign of the SSE signals in spin nematic LiCuVO4/Pt (ref. 28) is also opposite to the present CuGeO3/Pt case. We also note that, unlike the magnon-mediated SSE in ferro/ferrimagnets, the triplon-mediated SSE does not scale with the M(H) curve. For the magnon-mediated SSE27, M(H) represents the increase in the spin-current polarization. In contrast, the magnetization increase in the SP phase means larger density of broken dimers and the scattering probability between triplons and broken dimers becomes larger. The unusual H-dependence of the triplon SSE originates from the different properties between ferro/ferrimagnets and SP phases, and it is one of the characteristics of triplon SSE. (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for details).

As shown in Fig. 3a, b, the temperature dependence of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) shows that the signal magnitude increases monotonically as T decreases from TSP to 3 K. When T < 3 K, the SSE voltage remains almost unchanged down to 2 K. At higher temperatures, the dimerized ground state is weakened because the thermally excited phonon disturbs the spontaneous displacement of the Cu2+ ion. In other words, the singlet ground state and triplon excitation is no longer a good picture for the low-energy excitation, and the triplon lifetime shrinks toward higher temperatures and completely disappears at TSP. This effect has been observed as an increase in the peak width of the triplon excitation in neutron scattering experiments29. We note that, by phenomenologically incorporating the triplon-phonon scattering term in a calculation, the T dependence of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) at moderate temperatures can be explained qualitatively (see Supplementary Note G4 for details).

a, b Magnetic field (H) dependence of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) (the SSE signal normalized to the heating power and the detector resistance) at selected temperatures (T) for CuGeO3/Pt, with temperature gradient (∇T) applied along the spin chain. c H dependence of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) for CuGeO3/Pt, with ∇T applied perpendicular to the spin chain. d, e H dependence of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) at selected temperatures for Cu0.99Zn0.01GeO3/Pt and Cu0.97Zn0.03GeO3/Pt, respectively. In a–e, the SSE signal is normalized by the heating power and the detector resistance. f, g T dependence of magnetic susceptibility for Cu0.99Zn0.01GeO3 and Cu0.97Zn0.03GeO3, respectively. h T dependence of SSE signal in different samples at μ0H = 2 T. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Influence of crystal orientation and Zn-doping on the triplon SSE

Let us turn to the H dependence of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) in CuGeO3/Pt. In the entire temperature range, as H increases from zero, \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) increases first and takes its maximum at μ0H ~ 2 T. As H further increases, \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) is then suppressed. As shown theoretically in the following, triplon scattering by inevitable impurities and defects in the nominally pure CuGeO3 sample can explain the observed H dependence of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\).

To show that the observed voltage is related to the triplon in the SP phase, we performed another control experiment with ∇T applied perpendicular to the spin chain configuration. Figure 3c shows \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}(H)\) for ∇T⊥c in a reference sample prepared with the same procedure as ∇T∥c. The observed SSE signal in ∇T⊥c is only 1/7 in magnitude as compared to the ∇T∥c configuration, consistent with the highly anisotropic transport of triplons. This result corroborates that the origin of the observed signal is the 1-D triplon transport. Moreover, additional reference experiments are performed for two nonmagnetic Zn-doped CuGeO3 samples, in which the triplon spin current should be suppressed by Zn-induced scattering. Figure 3d, e show the \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}(H)\) for Cu0.99Zn0.01GeO3/Pt and Cu0.97Zn0.03GeO3/Pt in the same temperature range as the CuGeO3/Pt measurements. Clearly, \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) is suppressed in the 1% Zn-doped sample and disappeared in the 3% Zn-doped sample.

Figure 3f, g shows χ for Cu0.99Zn0.01GeO3 and Cu0.97Zn0.03GeO3, respectively. For Cu0.99Zn0.01GeO3, the SP transition is observed at 13.2 K. The decrease of TSP in doped CuGeO3 agrees with the result from the previous reports30. On the other hand, the SP transition is not visible in χ(T) in Cu0.97Zn0.03GeO3. Instead, a clear cusp is observed in χc(T) (with H∥c-axis) at TN ~ 4.3 K, indicating phase transition to an antiferromagnetic phase. The TN is consistent with the previously reported value for Zn-3% doped CuGeO3 (ref. 30). The doping effect implies that non-magnetic Zn breaks the Cu-spin chains and introduces unpaired Cu free spins, called solitons, into the spin chain. Solitons disturb the dimerization, and local antiferromagnetic correlation may lead to long-range antiferromagnetic order31 at low temperatures in Cu0.97Zn0.03GeO3. As shown in Fig. 3h, \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) is significantly suppressed in the ∇T⊥ spin-chain configuration and the Zn-doped CuGeO3 samples in all T range. In the doped samples, the spin-excitation gap is still present in the SP phase, but their transport may be blocked by Zn. The result suggests that the triplon spin current is strongly influenced by Zn-induced scattering. Curie-Weiss fitting of χ(T) at low T (<3 K)13,32 (see Supplementary Note F for details) reveals that the density of free S = 1/2 spins is estimated to be 0.02% in the nominally pure CuGeO3 sample, so the effect of triplon scattering by impurities cannot be ignored. Therefore, we attempted to formulate the triplon spin current in the manner of Boltzmann equation, which is capable of incorporating scattering effects.

Theoretical model for the triplon SSE

Figure 4 compares the H dependence of the observed SSE voltage signal with theoretical results. As we already discussed, \(| {\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}|\) is expected to monotonically grow with increasing H because the triplon density of Sz = 1, i.e., the dominant carrier of spin current, increases with lowering the spin gap up to the critical field Hm. However, the observed broad peak (see Fig. 4a) and the Zn-doped results shown in Fig. 3 strongly suggest the importance of triplon scattering processes. To theoretically analyze triplon currents in CuGeO3, we here apply the Boltzmann equation33. The spin current Js computed by the Boltzmann equation (See Supplementary Note G2) is given by

where ΔT is the temperature difference along the spin chain direction. \({v}_{{S}_{z}}(k)\), τk and \({\epsilon }_{{S}_{z}}(k)\) are the group velocity, relaxation time, and energy dispersion for the triplons17, respectively. We assume that the triplon can be viewed as a bosonic particle and the final part of Eq. (1) stems from the Bose distribution function. The Sz = 0 branch of the triplon does not contribute to the spin current. At H = 0, the distribution functions of Sz = ±1 branches are identical, which cancel out the total spin current. By varying T and H, the thermal excitation and the Zeeman effect alter the triplon distributions. Assuming a constant τk, the population difference between Sz = ±1 increases monotonically at a fixed T(<TSP) due to the Zeeman effect, resulting in an almost H-linear increase in Js. The H-linear behavior can also be reproduced by using a tunnel spin-current formula10,28,34,35, which is another microscopic theory for thermal spin current (see Supplementary Note G3).

a Magnetic field (H) dependence of the magnitude of \(| {\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}|\) (absolute value of the SSE signal normalized to the heating power and the detector resistance) at 2.5 K. b Calculation results of the H dependence of the triplon spin current (see text and Supplementary Note G2 for details).

As shown in Fig. 4a, \(| {\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}(H)|\) takes a maximum at around 3 T. To explain the non-monotonic behavior of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\), we considered two mechanisms of triplon scattering processes. One is the scattering by nonmagnetic impurities, where the scattering probability 1/τk,non-mag is constant with respect to H. Another source of scattering is free spins of broken dimers and unpaired Cu2+ (S = 1/2). The density of scatterers and scattering potential are assumed to depend on H as a Brillouin function. The total scattering probability is then the sum of the two scattering mechanisms, 1/τk,total = 1/τk,non-mag + 1/τk,mag. Assuming that the scattering effect by magnetic impurities is dominant, we can reproduce the experimentally obtained H dependence of \({\tilde{V}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{SSE}}}}}}}}}\) shown in Fig. 4b. In the low H regime, where the spin of magnetic impurities is not aligned and the scattering effect is weak, the Zeeman effect dominates the generation and transport of the triplon current. With increasing H, the triplon mode of Sz = +1 (Sz = −1) shifts downward (upward) due to the Zeeman effect, and the imbalance between Sz = ±1 triplons becomes larger, resulting in an increase in the total triplon current. As H is further increased, the impurities are magnetized and magnetic scattering dominates the triplon transport, resulting in a broad peak as shown in Fig. 4b. The result agrees with the experimentally obtained data shown in Fig. 4a at a semi-quantitative level.

Discussion

Finally, we here examine other possible origins for the observed thermoelectric voltage. One candidate could be the paramagnetic SSE due to free Cu spins. Several papers have addressed the spin current transport in paramagnets, including Gd3Ga5O12 (refs. 9,36), DyScO3 (ref. 9), and La2NiMnO6 (ref. 37). Paramagnon is believed to be responsible for spin transport in paramagnets as a result of short-range magnetic correlation or long-range dipole interactions. The spin diffusion length of Gd3Ga5O12 is estimated to be about 1.8 μm at 5 K36. However, in our CuGeO3 sample with the free spin density of 0.02%, the average distance between free spins is estimated to be around 0.29 nm/0.02% ~ 1.5 μm (the distance between neighboring Cu2+ ions along the c-axis is 0.29 nm38). This means that the paramagnetic spins are too dilute for spin correlation and spin current transport. Furthermore, the suppression of VSSE in the Zn-doped samples, which exhibit larger paramagnetic moments than CuGeO3, also rules out the possibility of paramagnetic SSE.

The normal and anomalous Nernst effects may also contribute to an electric voltage under a temperature gradient, but these effects contradict with the suppression of the signal in the high-temperature spin-liquid phase; the vanishing signals in the ∇T⊥c configuration and the Zn-doped samples (see Fig. 3a–e). Furthermore, the normal Nernst effect should be linear with respect to the applied magnetic field and can not explain the observed magnetic field dependence of VSSE shown in Fig. 3a, b.

Note that the voltage observed at 15 K in the CuGeO3/Pt shows almost no H-dependence, as shown in Fig. 2c. Above TSP, the elementary excitation of spin chains are gapless spinons21. A spinon spin current, a spin current carried by spinons, was found in Sr2CuO3 (ref. 10). The spinon spin current may contribute to a small H-linear voltage signal above TSP (see Supplementary Note C for details). In the spin-Peierls phase, the gapless spinon is replaced by the gapped triplon21.

In summary, we observed the triplon spin-Seebeck effect in CuGeO3/Pt. Due to the triplon excitation in the system, the sign of the observed SSE is opposite to that of the conventional magnon SSE. The triplon SSE signal persists down to 2 K in the spin-Peierls phase and the magnetic field dependence of the triplon SSE is consistent with microscopic calculation. Our result shows that the spin-Seebeck effect also acts as a probe for spin excitations in gapped spin systems, and can also be applied to other materials with exotic spin excitation, such as a spin ladder system SrCu2O3 (ref. 39) and a spin dimer system SrCu2(BO3)2 (ref. 40).

Methods

Sample fabrication

CuGeO3 single crystals were grown by a traveling solvent floating zone (TSFZ) method. Samples were cut into size of ~7 mm × 3 mm for further measurements. 40nm-thick ferrimagnetic insulator Y3Fe5O12 single crystals were grown on Gd3Ga5O12(111) substrates by magnetron sputtering. Prior to the deposition, Gd3Ga5O12 substrates were annealed in the air at 825 ∘C for 30 min in a face-to-face configuration. To crystalize the as-grown amorphous Y3Fe5O12, the samples were post-annealed in the air at 825 ∘C for 200 s. For SSE measurements, on-chip devices with Pt detector and SiO2/Au heater were fabricated on top of samples (both pure/doped CuGeO3 and Y3Fe5O12) by electron-beam lithography, magnetron sputtering and lift-off technique (see Supplementary Note A).

SSE measurement

We adapted the on-chip heating method for SSE, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. The resistance between the Au and Pt layers is much greater than MΩ at room temperature. A longitudinal temperature gradient was generated by applying an a.c. current with the frequency of f = 13 Hz to the Au heater. Since the SSE is driven by Joule heating, the frequency of the SSE signal on the Pt wire is 2f. The SSE signal was detected via a lock-in method.

Magnetization measurement

The magnetization of CuGeO3 was measured in a Quantum Design Physical Properties Measurement System (PPMS) with a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) option.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes used in theoretical simulations and calculations are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Uchida, K. et al. Observation of the spin Seebeck effect. Nature 455, 778–781 (2008).

Takahashi, S., Saitoh, E. & Maekawa, S. Spin current through a normal-metal/insulating-ferromagnet junction. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 200, 062030 (2010).

Saitoh, E., Ueda, M., Miyajima, H. & Tatara, G. Conversion of spin current into charge current at room temperature: inverse spin-Hall effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 182509 (2006).

Valenzuela, S. O. & Tinkham, M. Direct electronic measurement of the spin Hall effect. Nature 442, 176–179 (2006).

Ito, N. et al. Spin Seebeck effect in the layered ferromagnetic insulators CrSiTe3 and CrGeTe3. Phys. Rev. B 100, 060402 (2019).

Cornelissen, L. J., Liu, J., Duine, R. A., Youssef, J. B. & van Wees, B. J. Long-distance transport of magnon spin information in a magnetic insulator at room temperature. Nat. Phys. 11, 1022–1026 (2015).

Seki, S. et al. Thermal generation of spin current in an antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 266601 (2015).

Wu, S. M. et al. Antiferromagnetic spin seebeck effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 097204 (2016).

Wu, S. M., Pearson, J. E. & Bhattacharya, A. Paramagnetic Spin Seebeck Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 186602 (2015).

Hirobe, D. et al. One-dimensional spinon spin currents. Nat. Phys. 13, 30–34 (2017).

Hirobe, D., Kawamata, T., Oyanagi, K., Koike, Y. & Saitoh, E. Generation of spin currents from one-dimensional quantum spin liquid. J. Appl. Phys. 123, 123903 (2018).

Pytte, E. Peierls instability in Heisenberg chains. Phys. Rev. B 10, 4637–4642 (1974).

Hase, M., Terasaki, I. & Uchinokura, K. Observation of the spin-Peierls transition in linear Cu2+ (Spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\)) chians in an inorganic compound CuGeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 3651–3654 (1993).

Uchinokura, K. Topical review: spin-Peierls transition in CuGeO3 and impurity-induced ordered phases in low-dimensional spin-gap systems. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 14, R195–R237 (2002).

Nishi, M., Fujita, O. & Akimitsu, J. Neutron-scattering study on the spin-Peierls transition in a quasi-one-dimensional magnet CuGeO3. Phys. Rev. B 50, 6508–6510 (1994).

Lorenzo, J. E. et al. Soft longitudinal modes in spin-singlet CuGeO3. Phys. Rev. B 50, 1278–1281 (1994).

Takayoshi, S. & Sato, M. Coefficients of bosonized dimer operators in spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) XXZ chains and their applications. Phys. Rev. B 82, 214420 (2010).

Brill, T. M. et al. High-field electron spin resonance and magnetization in the dimerized phase of CuGeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1545 (1994).

Regnault, L. P., Ain, M., Hennion, B., Dhalenne, G. & Revcolevschi, A. Inelastic-neutron-scattering investigation of the spin-Peierls system CuGeO3. Phys. Rev. B 53, 5579–5597 (1996).

Fujita, O., Akimitsu, J., Nishi, M. & Kakurai, K. Evidence for a singlet-triplet transition in spin-peierls system CuGeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 1677 (1995).

Bonner, J. C. & Blöte, H. W. J. Excitation spectra of the linear alternating antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 25, 6959–6980 (1982).

Rønnow, H. M. et al. Neutron scattering study of the field-induced soliton lattice in CuGeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4469 (2000).

Hase, M. et al. Magnetization of pure and Zn-doped spin-Peierls cuprate CuGeO3 in high magnetic field. Physica B: Condens. Matter 201, 167–170 (1994).

Uchinokura, K., Hase, M. & Sasago, Y. Magnetic phase transitions in CuGeO3 in high magnetic fields. Physica B: Condens. Matter 211, 175–179 (1995).

Maekawa, S., Valenzuela, S., Saitoh, E. & Kimura, T. Spin Current (OUP Oxford, Oxford, 2012).

Kikkawa, T. et al. Critical suppression of spin Seebeck effect by magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 92, 064413 (2015).

Uchida, K.-i et al. Observation of longitudinal spin-Seebeck effect in magnetic insulators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 172505 (2010).

Hirobe, D. et al. Magnon pairs and spin-nematic correlation in the spin Seebeck effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 117202 (2019).

Lussier, J. G., Coad, S. M., McMorrow, D. F. & Paul, D. M. The temperature dependence of the spin - Peierls energy gap in CuGeO3. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 8, L59–L64 (1996).

Sasago, Y. et al. New phase diagram of Zn-doped CuGeO3. Phys. Rev. B 54, R6835–R6837 (1996).

Fukuyama, H., Tanimoto, T. & Saito, M. Antiferromagnetic long range order in disordered spin-peierls systems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 65, 1182–1185 (1996).

Grenier, B. et al. Magnetic susceptibility and phase diagram of CuGe1−xSixO3 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 57, 3444–3453 (1998).

Abrikosov, A. Fundamentals of the Theory of Metals (Dover Publications, Mineola, New York, 2017).

Adachi, H., Ohe, J.-i., Takahashi, S. & Maekawa, S. Linear-response theory of spin Seebeck effect in ferromagnetic insulators. Phys. Rev. B 83, 533 (2011).

Jauho, A.-P., Wingreen, N. S. & Meir, Y. Time-dependent transport in interacting and noninteracting resonant-tunneling systems. Phys. Rev. B 50, 5528 (1994).

Oyanagi, K. et al. Spin transport in insulators without exchange stiffness. Nat. Commun. 10, 4740 (2019).

Shiomi, Y. & Saitoh, E. Paramagnetic spin pumping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 266602 (2014).

Kamimura, O., Terauchi, M., Tanaka, M., Fujita, O. & Akimitsu, J. Electron diffraction study of an inorganic spin-peierls system CuGeO3. J. Phys.Soc. Jpn. 63, 2467–2471 (1994).

Azuma, M., Hiroi, Z., Takano, M., Ishida, K. & Kitaoka, Y. Observation of a spin gap in SrCu2O3 comprising spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) quasi-1D two-leg ladders. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 3463–3466 (1994).

Kageyama, H. et al. Exact dimer ground state and quantized magnetization plateaus in the two-dimensional spin system SrCu2(BO3)2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 3168–3171 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Hirobe, T. Kikkawa, G. E. W. Bauer, and Y. Hirayama for valuable discussions. This research was supported by JST ERATO Spin Quantum Rectification Project (No. JPMJER1402), JPSP KAKENHI (the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) No. JP19H05600 and JP17H06137; the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) No. JP16H02125; the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) No. JP20H01830 and No. JP19H02424; the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) No. JP17K05513; the Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Exploratory) No. JP19K22124 and No. JP20K20896; the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (Research in a proposed research area) No. JP20H04631, No. JP20H05153, No. JP19H05825 and No. JP19H04683; the Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity start-up No. JP20K22476), JST CREST (No. JPMJCR20C1 and No. JPMJCR20T2), and MEXT (Innovative Area “Nano Spin Conversion Science” (No. 26103005)). Y.C., Y.T., and K.O. are supported by GP-Spin at Tohoku University. Y.C. is also supported by the Japan Society for Promotion of Science through a research fellowship for young scientists (No. JP18J21304).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. designed the experiments in discussion with Y.S. and E.S. Y.T., Y.N., T.M., and M.F. grew single crystals for this study. Y.C. and K.O. nano-fabricated devices. Y.C. collected and analyzed the experimental data. M.S. preformed the theoretical calculations. E.S. supervised this work. Y.C., M.S., Y.S., and E.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Joseph P. Heremans, Roberto Myers, and Ganesh Ramachandran for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Sato, M., Tang, Y. et al. Triplon current generation in solids. Nat Commun 12, 5199 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25494-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25494-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.