Abstract

The bonding of copper ions to lattice oxygens dictates the activity and selectivity of copper exchanged zeolites. By 17O isotopic labelling of the zeolite framework, in conjunction with advanced EPR methodologies and DFT modelling, we determine the local structure of single site CuII species, we quantify the covalency of the metal-framework bond and we assess how this scenario is modified by the presence of solvating H216O or H217O molecules. This enables to follow the migration of CuII species as a function of hydration conditions, providing evidence for a reversible transfer pathway within the zeolite cage as a function of the water pressure. The results presented in this paper establish 17O EPR as a versatile tool for characterizing metal-oxide interactions in open-shell systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Copper-exchanged zeolites have been in the focus of comprehensive studies for decades1,2 and are a subject of evergreen interest in catalysis due to applications ranging from NOx removal3,4 to the direct conversion of methane to methanol5,6,7. Among other systems, the Cu-Chabazite (Cu-CHA) redox catalyst is particularly attractive as it couples industrial and environmental relevance—a Cu-CHA catalyst for diesel engine exhaust was commercialized since 2008—and structural simplicity. Cu-CHA catalysts have been widely investigated and it is agreed that isolated CuII ions at ion-exchange positions are the active sites for the NH3-SCR reaction8. However, the exact nature of the active sites and the impact of e.g. the Si/Al ratio and the copper content on the catalytic performance are still under debate. These make it an ideal model system to address fundamental questions of structure–performance relationships in the general context of metal-exchanged zeolite catalysis1.

The high activity of copper-containing zeolites in oxidation and reduction reactions is typically associated with the redox transformations of copper species. These range from isolated single ion sites9 to polynuclear species10, all featuring unsaturated coordination and the possibility for adsorption of small molecules. One crucial aspect to understand and control the catalytic potential of such species is the detailed knowledge of their structure and of the intimate features of chemical bonding, which include covalency, ionicity, electron and spin delocalization.

For paramagnetic CuII species (S = 1/2) the sensitivity and selectivity of EPR techniques are in principle ideally suited to obtain detailed information on the topological distribution and the nature of the chemical bonding of CuII species in zeolites and indeed EPR has been abundantly used to investigate such systems11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. However, the most revealing and important piece of information that can be extracted from this technique, the detection of hyperfine couplings (a measure of the interaction between the electron spin and the nuclear spin of atoms in contact with the unpaired electron) for the coordinating oxygen atoms, is currently missing.

The only magnetic isotope of oxygen is 17O (I = 5/2) but its natural abundance (0.037%) is by far lower than the value necessary to detect a hyperfine structure. The exploitation of hyperfine techniques for the investigation of the metal-oxygen bond requires therefore the isotopic enrichment of oxide solid systems that involves both cost and effort, which however can be very rewarding. Indeed 17O solid state NMR has revealed invaluable to address important issues in this context, providing unique insights into crucial aspects related to the local structure of aluminosilicate zeolites21,22. However, this approach cannot be applied to investigate the Cu–O interaction due to the paramagnetic nature of CuII ions. 17O EPR has been used in different context to derive structural information on paramagnetic species23,24,25,26,27,28. Here we show that the 17O isotopic labelling of the framework provides a unique source of information about the local binding environment of the active site enabling the rationalization of structure-property relationships in Cu-loaded zeolites under, for instance, different hydration conditions. Water has been shown to play a strong effect on the reactivity of Cu species in zeolites promoting specific reaction pathways29,30,31, promoting dynamic catalytic mechanisms at the cross road between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis32,33,34.

The 17O resonance from oxygen atoms directly bound to CuII species in a low copper loaded Chabazite is reported. This enables the identification of two specific binding sites which are selectively populated as a function of the hydration conditions. By the selective isotopic labelling of the zeolite framework with 17O and employing advanced EPR methodologies in conjunction with DFT modelling, we have been able to obtain exquisite details on the nature of the Cu interaction with the oxygen donor atoms of the zeolite framework and of solvating water molecules. We demonstrate that the measured 17O hyperfine couplings provide a so far unexplored and effective handle to obtain a detailed understanding of the Cu–O bond, to assess the siting of Al in the most stable Cu coordination and to follow the migration of CuII species across the zeolite channels as a function of hydrating conditions.

Results and discussion

Structure and dynamics of isolated CuII ions

The first key question we address is related to the structure and dynamics of CuII species as a function of hydration and their interaction with the zeolite framework. The fundamental building block of the CHA framework is a double six-membered ring (D6MR) unit disposed in layers according to an ABC stacking and linked by four-membered rings (4MRs). The interconnection of the D6MRs along the three dimensions generates eight-membered rings (8MRs) units (Fig. 1a). According to early reports35,36,37 and more recent studies3,31, the potential extra-framework sites of Cu cations are located on the window of D6MRs (Fig. 1b) or on 8MRs (Fig. 1c) with either two framework aluminium atoms (2Al) or one aluminium site (1Al) plus an extra-lattice OH− ligand for charge compensation (for this latter case see Supplementary Note 3).

a Graphical representation of CHA framework. The fundamental units are highlighted with different colours. Spin density plots of dehydrated CuII ion sitting on 6MR and hydrated CuII complex attached to the framework in 8MR site are illustrated in (b, c), respectively. d X-band CW-EPR spectra recorded at room temperature of fully hydrated with H216O Cu-CHA and dehydrated at increasing temperatures according to the procedure described in ‘Methods’ section. The hyperfine components of rigid and mobile species are indicated. The asterisk indicates a carbon radical signal. e Spin density plots of [Cu(H2O)6]2+ complex encapsulated in the largest Chabazite’s cage. The labels Oen and Oan refer to n equatorial and axial oxygen ligands, respectively.

Continuous wave (CW)-EPR spectra of the Cu-exchanged CHA sample were recorded as a function of the dehydration temperature and show characteristic spectral patterns depending on the degree of hydration (Fig. 1d). The spectrum of the fully hydrated system is due to two S = 1/2 EPR signals, characteristic of CuII ion with a different local environment3,11,38,39. The room temperature (RT) spectrum shows the contribution of a motionally averaged and a rigid-limit anisotropic components, corresponding to a mobile solvated structure (Fig. 1e) and framework-bound CuII species (Fig. 1c), respectively (see Table 1 and for further details on low temperature CW-experiments, see Supplementary Fig. 1).

The progressive dehydration of the sample (Fig. 1d) is accompanied by a narrowing of the spectral linewidth and disappearance of the motionally averaged component in the RT CW-EPR spectrum. A sharp signal at g = 2.0028 (asterisk in Fig. 1d) is observed in the dehydrated sample, which is often present even in the most careful calcination protocols and assigned to carbon radicals deriving from carbonaceous residues in the zeolite framework40. After dehydration at 400 °C the overall EPR spectral intensity is reduced of about 40% with respect to the fully hydrated system (see Supplementary Fig. 1). The loss of EPR intensity during the sample activation is a well-known phenomenon, which strongly depends on the Si/Al and Cu/Al ratios41,42. Dramatic losses of over 80% have been reported for Cu-CHA with Si/Al = 14 and Cu/Al in the range 0.1–0.439,42,43. The limited reduction we have observed is consistent with the low Cu/Al = 0.005 ratio and is most likely associated to the presence of residual carbonaceous impurities (g = 2.0028 carbon radical signal, Fig. 1d), which act as reducing agents44,45. Although a contribution from the so-called ‘autoreduction’ mechanism42,46 cannot be excluded, this is expected to be relevant at higher Cu/Al ratios as it relies on the condensation of neighbouring hydroxyl bridged [CuOH]+ species whose presence is limited by the low Cu loading considered in this work31.

To summarize, the analysis of the CW-EPR spectra as a function of the sample dehydration evidences the presence of at least two CuII species characterized by distinctively different spin-Hamiltonian parameters, which change as a function of the dehydration treatment in line with previous reports47. In the case of the hydrated sample, two species with nearly equal abundance are present (Table 1). One such species (A in Table 1) shows spin-Hamiltonian parameters typical for [Cu(H2O)6]2+ complexes (Fig. 1e)48,49. The other species (B in Table 1) has spin-Hamiltonian parameters consistent with a tetragonally elongated 6-coordination, i.e. with a distorted octahedral geometry (Fig. 1c)11,50. On the other hand, the spectrum of the fully dehydrated sample is dominated by a CuII species accounting for about 80% of the total EPR intensity with spin-Hamiltonian parameters (C in Table 1) agreeing with a tetragonal planar coordination of CuII (Fig. 1b)18,38,51,52. These configurations are supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations (for further details on the computed EPR parameters, see Supplementary Tables 3, 6, and 7) that give the singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) as dominated by the Cu dx2–y2 orbital with participation of the 2p oxygen orbitals (Fig. 1c–e). The degree of covalency of the Cu–O bond (i.e. the oxygen contribution to the SOMO) will be addressed in the following, along with the detailed topological description of the CuII docking sites under specific hydration conditions.

Geometrical and electronic structure through spin density studies

Most of the information relative to the topological distribution of the CuII species is hidden in the inhomogeneously broadened line of the CW-EPR spectrum and is related to the hyperfine interactions (hfi) with nearby magnetic nuclei (1H, 27Al and 17O). In order to obtain such fundamental knowledge for the structural characterization of CuII siting, hyperfine techniques (HYSCORE and ENDOR) were employed at X- and Q-band frequencies.

The progressive dehydration of the sample was carefully followed by X-band HYSCORE and Q-band Davies ENDOR experiments. The results are shown in Fig. 2a–c where 1H HYSCORE, 1H ENDOR and 27Al HYSCORE experiments are shown for the same dehydration conditions reported in Fig. 1d.

a X-band 1H HYSCORE spectra recorded at 4.5 K and obtained at the echo maximum intensity position of Cu-CHA gradually dehydrated. b Corresponding Q-band 1H Davies ENDOR spectra (black line) acquired at 20 K at the field indicated above the plot and their simulations (red line). c X-band 27Al HYSCORE spectra recorded at same experimental conditions of 1H HYSCORE spectra. 1H and 27Al signals are indicated by arrows. The parameters used in the simulation satisfy both HYSCORE and Davies ENDOR spectra.

The X-band 1H HYSCORE spectrum, correlates nuclear frequencies in the α and β electron spin manifolds that result in—for a set of magnetically equivalent protons featuring weak hyperfine couplings (2|νH| > |A|)—ridges centered at the proton Larmor frequencies (νH) and extension corresponding to the orientation-dependent hyperfine coupling constant (A). The same information can be retrieved by ENDOR experiments, which, under the same conditions, are characterized by a pattern consisting of a single pair of lines separated in frequency by A and mirrored about νH. The 1H HYSCORE spectrum of the hydrated sample is characterized by two distinct ridges with maximum extension of the order of 9 and 3 MHz (Fig. 2a, at the top). These couplings are also confirmed by Q-band Davies ENDOR experiments (Fig. 2b, at the top). The field dependent experimental spectra are simulated exceedingly well considering two interacting protons with hyperfine coupling tensors (in MHz) of AH(1) = [−5.5 −7.5 +8.5] and AH(2) = [−2.7 −3.7 +7.3], whereby the maximum coupling of H(1) lies in the plane of the dx2−y2 orbital, while for H(2) is approximately perpendicular to it. The smaller hyperfine coupling also correlates with the larger axial Cu–O distance (around 0.23 nm with respect 0.19 nm of the equatorial Cu–O distance; distances obtained from periodic DFT geometry optimizations are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 5) of the axially coordinating water molecules. These values are typical for hexaaquacopper complexes (Fig. 1e) and were attributed by Pöppl and Kevan to equatorial and axial water molecules of the [Cu(H2O)6]2+ complex49. A very weakly coupled proton signal is also detected and labelled H(3) in Fig. 2, which we assign to second shell coordinating water molecules.

The intensity of the 1H HYSCORE ridges decreases until the signal completely disappears in the fully dehydrated state, probing the progressive dehydration of the sample. Correspondingly, the 1H ENDOR spectra show that the weakly coupled protons (H(2) and H(3)) are the first one to be lost at this dehydration stage. These couplings are amenable to axially coordinated water molecules (H(2)) or second shell coordinating H2O (H(3)), both displaying a weaker binding energy and therefore removed in the first stages of the dehydration process. On the other hand, H(4) nuclei possess hyperfine couplings and Euler angles similar to H(1), suggesting the stronger persistence of equatorial protons with respect to axial ones. When complete dehydration was achieved, the proton signals are no longer observed (Fig. 2a, b, at the bottom) proving that all coordinated water molecules were removed.

27Al HYSCORE spectra (Fig. 2c) display a pair of cross peaks centered at the Al Larmor frequency (νAl) indicating a hyperfine interaction of the order of 3 MHz. The narrow shape of the cross peaks and absence of multiple quantum transitions indicate a low value of the nuclear quadrupole interaction (estimated to be of the order of e2qQ/h ≤ 4 MHz, see Supplementary Fig. 2). These features are typical for S = 1/2 transition metal ions in zeolite systems53,54,55 and diagnostic of M–O–Al linkages, demonstrating that under hydration conditions a fraction of the CuII ions maintains, at least, a partial interaction with the zeolite framework, in agreement with the RT CW-EPR spectrum. At increasing dehydration temperatures, the 27Al signals drastically change, evolving from well-defined cross peaks in the hydrated sample to a unique unresolved diffuse signal in the fully dehydrated sample (Fig. 2c, at the bottom and Supplementary Fig. 3). This behaviour corresponds to a continuous increase of the aluminium quadrupolar interaction upon water removal, consistent with previous reports on metal-doped zeolites56,57 and quantum mechanical modelling (Supplementary Table 7).

The full set of 27Al and 1H hfi evaluated through the simulation of HYSCORE and ENDOR spectra (for the simulation of HYSCORE spectra, see Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3) are listed in Table 2.

Summarizing, the combination of CW-EPR and hyperfine techniques, provides evidence, in the hydrated sample, for solvated and mobile [Cu(H2O)6]2+ species along with framework interacting species, which attain a partially solvated structure bearing intimate contact with the framework. Upon dehydration, the two species adopt a tetragonal planar coordination through coordinating oxygen donor atoms of the zeolite cage.

Nature of the Cu–O bonding interaction from 17O EPR

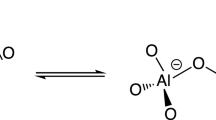

Since the SOMO serves as the redox-active orbital in CuII systems, the covalency of this orbital is crucial for understanding the catalytic properties of Cu based catalysts. The degree of covalency in the ligand–metal bond has far-reaching implications towards reactivity and catalysis as it is the key to activate directional long-range electron transfer pathways58,59, enhance catalyst stability60 and determine the selective stabilization of intermediate species in redox reactions61. Detailed information on the Cu–O bonding interaction can be obtained through the detection of the 17O hyperfine interaction, which is a direct reflection of the spin delocalization over the coordinating ligands and a direct probe of the metal-ligand covalent character. To enable the detection of 17O hyperfine interactions we isotopically enriched the zeolite framework following protocols previously introduced by some of us62. Hydration and dehydration cycles with 17O enriched water lead to framework 17O incorporation. As reported by some of us62 and confirmed by 17O NMR studies22, under the mild reaction conditions adopted in this work, both Al–O and Si–O bonds undergo 17O isotopic exchange. This is schematically shown in Fig. 3a, where the exchangeable sites are highlighted. Orientationally selected 17O Davies ENDOR spectra of the hydrated and fully dehydrated zeolite are shown in Fig. 3b and c, respectively. An ENDOR signal represents an NMR absorption which is observed as a change in the echo signal intensity at a fixed resonant magnetic field, B0.

a Schematic representation of the isotopic enrichment of the zeolite framework. b Experimental (black) and simulated (red) Q-band 17O ENDOR spectra recorded at different magnetic field settings of 17O isotopically enriched Cu-CHA fully hydrated with H217O. c Corresponding experiment performed on a fully dehydrated 17O enriched Cu-CHA. The ESE spectra with the corresponding field positions at which the ENDOR spectra were taken are plotted on the left-hand side. All spectra were recorded at 20 K.

The ENDOR pattern for the Δm = ±1 transitions for 17O (I = 5/2), are expected to obey the Eq. (1):

where A and P are the orientation-dependent hyperfine and quadrupole interaction constants respectively and νI = 6.73 MHz is the nuclear Larmor frequency of 17O at Q-band63. When (2|νI| < |A|) as occurs in our case, the equation describes a pattern consisting of two groups of 2I lines each, centered at A/2 and separated by 2νI. Within each group the resonances are separated by 3P.

The low field 17O ENDOR spectrum of the hydrated zeolite (Fig. 3b) corresponds to a single crystal-like orientation and is characterized by an unresolved set of 2I = 5 quadrupole lines separated by 2νI and centered at a frequency corresponding to A/2 (17O(1) in Fig. 3b). The higher-frequency component is more intense, probably due to hyperfine enhancement and/or due to radio frequency (RF) conversion efficiency of the RF coils. A second oxygen (17O(2) in Fig. 3b) with an hyperfine coupling of the order of 12 MHz, close to the cancellation regime (2|νI| ≈ |A|), is also present and responsible for the resonance fixed at approximately 12 MHz.

To identify the oxygen ligand containing 17O and ascertain the presence of framework coordination, experiments were performed on a 17O isotopically enriched Cu-CHA zeolite (Supplementary Fig. 4), subsequently hydrated with normal water. The presence of 17O resonances (Supplementary Fig. 5), similar to those reported in Fig. 3b in the ENDOR spectra, demonstrates the presence of an intimate interaction of CuII species with the zeolite framework under hydrating conditions supporting the assignment based on 27Al HYSCORE spectra. By fitting the experimental spectra taken at various resonant magnetic field the full 17O interacting tensor for the two families of interacting nuclei was recovered with AO(1) = [−36.5 −36.5 −60.5] MHz and AO(2) = [−8 −8 −14] MHz whereby a negative sign was assumed, based on the negative nuclear g factor of 17O and in agreement with the results of DFT calculations, listed in Supplementary Table 6. The observed couplings can be assigned to equatorially (AO(1)) and axial (AO(2)) coordinating oxygens, whereby the difference in the hyperfine coupling reflects the small overlap of the oxygen 2p orbitals of the axial ligands with the Cu 3dx2−y2 orbital. The spin density on the two coordinating oxygens is estimated to be ρO(1) = 5.4% and ρO(2) = 1.1% (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Table 1)64.

ENDOR spectra for the dehydrated zeolite (Fig. 3c) provide a unique level of detail on the dehydrated CuII docking site, giving evidence of two distinct oxygen species coordinated to the CuII species. At variance with the fully hydrated system, the single crystal-like spectrum recorded at 1006.0 mT is characterized by two doublets separated by 2νI and centered at 37 MHz and 30 MHz, respectively. Simulation of the field dependent spectra allowed to extract the full 17O A-tensors (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 6). The larger 17O hyperfine couplings imply an increased spin density transfer over the framework oxygen donor atoms with respect to the hydrated system equivalent to ρO(3) = 8.5% and ρO(4) = 6.6%. These values correspond to the covalent contribution to the SOMO per O atom. Considering four coordinating oxygen atoms (Fig. 1b and DFT modelling, vide infra and Supplementary Table 2), the wave function is composed by a 70% contribution from Cu 3dx2-y2 orbital with the remaining 30% being shared among the 2p orbitals of the lattice oxygen ligands.

Based on the ENDOR linewidth, we estimate an upper limit of the order of 7 MHz for the 17O nuclear quadrupole coupling constant (e2qQ/h) for both anhydrous and hydrated conditions. These values are consistent with those reported from 17O-NMR studies21 for Brønsted acid sites of 6.6 MHz and in line with computed values reported in Supplementary Tables 6 and 7.

The contribution from the different species were properly weighted in the simulation in order to better fit the experimental plot. 17O(3) and 17O(4) species were considered in 1:1 ratio, whereas 17O(1) bestows the 95 % of the simulated signal and 17O(2) accounts for the remaining 5%. H(1), 17O(1), 17O(3) and 17O(4) hyperfine tensors are found to be in the same plane (same Euler β angle which expresses the orientation of A-tensor with respect to g-tensor). In the same way, Al(1), H(2) and 17O(2) hfi tensors are almost collinear to each other. A summary of the 17O spin-Hamiltonian parameters adopted for simulating the ENDOR spectra is given in Table 3.

The microscopic structure of CuII in CHA and Al siting: DFT Modelling

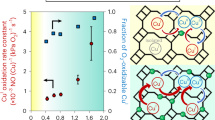

To transpose the spectroscopic findings into atomistic models, DFT calculations were carried out for copper docking sites differing in the Al distribution, namely two Al in two adjacent D6MR, two Al in the same D6MR at second-nearest-neighbour positions and two Al in the same D6MR at third-nearest-neighbour positions (1Al, 2Al-2NN, 2Al-3NN in Fig. 4a). All the aluminium distributions obey the Loewenstein rule avoiding two adjacent sites to be occupied by Al ions65.

a B3LYP-D3(ABC)/pob-TZVP fully optimized structures of dehydrated Cu-CHA models (Si/Al = 11) by employing three different Al distributions, namely 2Al-3NN, 2Al-3NN and 1Al. The corresponding relative electronic energy per unit cell is shown for each structure. The unit cell (top left of the figure) is oriented according to the lattice vectors reported in cyan. b Comparison of experimental (red) and computed (blue) maximum hyperfine coupling values (Amax) for 17O and 27Al nuclei for the three different Al distributions illustrated in (a). The black dashed lines represent the experimental range of Amax for 17O nuclei.

The relative energy of CuII at the three sites was computed for two different Si/Al ratios (Si/Al = 11 and Si/Al = 5). The optimized structures all converged to a tetragonal coordination by the lattice oxygen donor atoms (henceforth named \([{{{{{{\rm{Cu}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{II}}}}}}}{\left({{{{{\rm{O}}}}}}-6{{{{{\rm{MR}}}}}}\right)}_{4}]\)). The most energetically stable configuration was obtained for 2 Al at third-nearest-neighbour (2Al-3NN) positions in a 6MR unit independent of the Si/Al ratio, in agreement with the previous evidence3,31.

For each model, the spin-Hamiltonian parameters were calculated and compared to the experimental data. The computed g- and copper A-tensors obtained by using the geometry optimized structures are reported in Supplementary Table 4 and are in qualitative agreement with the experimental data, but do not allow to confidently discriminate among the three different possible structures presented in Fig. 4. This is unsurprising as the precise and robust calculation of g- and A-tensors for CuII systems is still a great challenge for quantum chemistry methods and only qualitative agreements are usually obtained66,67,68. On the other hand, the prediction of hyperfine couplings for lighter elements (due to negligible spin-orbit coupling and a more accurate determination of the Fermi contact term) is far more reliable69. In Fig. 4b the maximum hyperfine coupling values (Amax = |aiso + 2 T|) for 17O and 27Al nuclei is plotted for the three different structures and compared with the experimental values. Examination of the computed values shows that the experimental 27Al couplings are quantitatively reproduced, however they are not diagnostic as all models yield very similar values. In particular, in the case of the 2 Al models (2Al-3NN and 2Al-2NN in Fig. 4b) the computed couplings display analogous values (∼7 MHz and ∼1 MHz) irrespectively of the Al location. While the 7 MHz coupling is in agreement with the experimental value of 6 MHz, typical for Cu loaded zeolites55, the 1 MHz coupling is too small to be confidently measured, making it impossible to discriminate between 2 Al and 1 Al sites. 17O hyperfine couplings prove to be a far more sensitive structural probe. The experimental data (Table 3) point to two sets of 17O nuclei characterized by different couplings, whereas four different couplings are computed for all models. However, inspection of Fig. 4b shows that only for 2Al-3NN two classes of alike couplings (O1, O3 and O2, O4) can be recognized, with values falling within the experimental range, while 1 Al and 2Al-2NN models feature remarkably different couplings for all four oxygen nuclei (see also the simulation of the 17O ENDOR spectra considering the DFT calculated hyperfine couplings in Supplementary Fig. 7).

The differences in the 17O hyperfine couplings do not arise from differences in the Cu–O bond lengths (Supplementary Table 2), but rather in slightly different spin density transfer over the coordinating oxygen atoms. This can be traced back to geometric distortions from square planar coordination, resulting in a decreased overlap between the Cu dx2−y2 and the O 2p orbitals. A similar effect is observed for [CuCl4]2− complexes where the covalent contribution of the ligands to the SOMO is found to increase from D2d to D4h symmetries due to the increasing overlap between the Cu dx2−y2 orbital and the Cl 3p orbitals in the two geometries70. The three different sites considered in this work feature very similar Cu–O distances but slightly different geometric distortions, leading to asymmetries in the spin delocalization, characteristic for the different sites. Crucially, asymmetries in the spin delocalization are of outmost relevance as they report on the covalent character of each ligand–metal bond, which ultimately design preferential electron transfer pathways58,59.

Overall, this analysis shows that not only structure 2Al-3NN is the most energetically favoured, but it is also the only one for which a satisfactory agreement between computed and experimental spin-Hamiltonian parameters is obtained. In turn, this allows to confidently conclude that 2Al-3NN sites are those dominantly populated by CuII species under the experimental conditions.

A similar analysis on the hydrated system, yields a different scenario for the CuII docking and allows the assessment of migration pathways induced by hydration/dehydration processes. Based on experimental UV-vis, IR and XAS spectra of Cu-CHA in hydrated state at room temperature, previous studies have assumed the presence of two types of CuII complexes, regardless the copper loading and the composition of the zeolite: the former are divalent complexes charge-compensated by a pair of Al atoms (like [Cu(H2O)6]2+ or [CuII(O-8MR)6-n(H2O)n]); the latter are monovalent complexes charge-compensated by one Al atom (e.g. [CuII(OH)(H2O)5] or [CuII(OH)(O-8MR)5−n(H2O)n])31,39. However, the discrimination among such hydrated complexes is hampered by the resolution of the experimental techniques mentioned above. To shed light on the nature of the hydrated species, we first assessed the relative stability of CuII at the different sites as a function of hydration by considering the effect of a single water molecule coordinated to CuII ions hosted in 6MR and 8MR sites, as illustrated in Fig. 5a, b.

a Hydrated and b dehydrated CuII species in 6MRs and 8MRs sites with the corresponding relative electronic energy per unit cell. c Picture of the CuII dynamics inside the CHA framework due to the presence of water molecules. Some relevant atoms are represented by balls-and-sticks (colour code: medium blue Cu, yellow Si, violet Al, red O, white H).

When we consider a dehydrated CuII ion, the 6MR site is far more stable than the 8MR because of the stronger binding to the four framework oxygen atoms in a tetragonal geometry. Energetic considerations suggest thus such a location is the preferred one for the dehydrated material, in agreement with several experimental and theoretical studies35,37,71. However, the adsorption of water molecules completely alters the relative stabilities: with one water ligand, the stability of both sites becomes similar (Fig. 5a). Further addition of H2O molecules increases the energy gap between the different cage locations pointing out that, in hydrated and partially hydrated conditions (both experimentally observed), 8MR sites are more stable than 6MR, in agreement with the findings of Kerkeni et al.72. Details on such results are reported in Supplementary Fig. 8.

The spin Hamiltonian parameters for the hydrated structures shown in Fig. 6a, b and hydrated [CuOH]+ species (Supplementary Fig. 10) were computed. The 1H hyperfine couplings for the [Cu(H2O)6]2+ (Fig. 6a) and interfacial Cu species (Fig. 6b) are in quantitative agreement with the experimental values and characteristic for axially (small hyperfine coupling) and equatorially (large hyperfine coupling) water bound protons. On the other hand, the computed 1H hyperfine coupling of the hydroxyl proton of [CuOH]+—about 20 MHz (Supplementary Table 8 and Supplementary Note 3)—is exceedingly large and allows to discard this structure, consistently with the small Cu/Al ratio. This is also in agreement with the relatively small reduction of the sample upon dehydration compared to similar systems with higher Cu loadings and concur to confirm that 2 Al sites are preferentially populated, consistently with energetic considerations. Computed oxygen hyperfine couplings for these structures (Supplementary Table 6) reproduce the experimental values showing a set of large aiso couplings (−45 MHz and −55 MHz) related to equatorially coordinated oxygen ligands and a set of small values (−8 MHz and −6 MHz) associated to axially coordinated oxygen ligands.

a \([{{{{{{\rm{Cu}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{II}}}}}}}{({{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}})}_{6}]{{{{{\rm{@CHA}}}}}}\) in the Chabazite’s largest cage, b \([{{{{{{\rm{Cu}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{II}}}}}}}{({{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}})}_{4}{({{{{{\rm{O}}}}}}-8{{{{{\rm{MR}}}}}})}_{2}]\) complex and c \([{{{{{{\rm{Cu}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{II}}}}}}}{\left({{{{{\rm{O}}}}}}-6{{{{{\rm{MR}}}}}}\right)}_{4}]\) complex at the 2Al-3NN site. Cu–O bond lengths are indicated in nm. The label of relevant nuclei is reported whereas Si and H atoms are shown in yellow and white, respectively. The remaining framework atoms are represented by grey sticks.

In summary, two CuII complexes are identified under hydrating conditions, \([{{{{{{\rm{Cu}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{II}}}}}}}{({{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}})}_{6}]{{{{{\rm{@CHA}}}}}}\) (Fig. 6a) and an interfacial complex \([{{{{{{\rm{Cu}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{II}}}}}}}{({{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}})}_{4}{({{{{{\rm{O}}}}}}-8{{{{{\rm{MR}}}}}})}_{2}]\) (Fig. 6b), whereby with the notation @CHA we indicate the hexaaquacopper complex encapsulated in the Chabazite’s largest cage. The CHA cage has a diameter of 1.2 nm ensuring the possibility of free tumbling of the water complex at room temperature and explaining the motionally averaged spectrum observed at RT. This mobile species coexists along with the \([{{{{{{\rm{Cu}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{II}}}}}}}{({{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}_{2}{{{{{\rm{O}}}}}})}_{4}{({{{{{\rm{O}}}}}}-8{{{{{\rm{MR}}}}}})}_{2}]\) complex (Eq. (2) and Fig. 5c), where two water ligands are substituted by two oxygen donor atoms belonging to the 8MR site as demonstrated by 17O ENDOR spectra recorded on the 17O-exchanged zeolite in the presence of H216O (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The hydration–dehydration processes in Cu-CHA can, therefore, be described in terms of a dynamic conversion (Eqs. (3) and (4)) between water solvated species and an interfacial complex \([{{{{{\rm{Cu}}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{II}}}}}}({{{{{\rm{O}}}}}}-6{{{{{\rm{MR}}}}}})_{4}]\), whereby the 6MR cage behaves as a tetradentate ligand as shown in Fig. 6c.

The \({[{{{{{{\rm{Cu}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{II}}}}}}}\left({{{{{\rm{O}}}}}}-6{{{{{\rm{MR}}}}}}\right)_{4}]}\) interfacial complexes feature a SOMO with predominant metal dx2−y2 character and a covalent contribution of about 30% from the coordinating framework oxygen donor atoms. Importantly, DFT calculations demonstrate that the spin density distribution over the coordinating oxygens and the corresponding 17O hyperfine couplings are significantly dependent upon the Al distribution in the 6MR site, allowing to discriminate between different Al locations. In particular we find that for the low Cu loading considered in this work, the 2Al-3NN site, characterized by 2 Al atoms separated by two Si, not only has the lowest energy but also provides the better agreement between calculated and experimental 17O hyperfine coupling constants. The new methodology and associated new knowledge that emerges from this study will need to be applied systematically to other framework topologies and comparison will need to be set to catalysts characterized by different Si/Al and Cu/Al ratios. This systematic approach will form the basis to correlate catalytic performances to the Cu (and in general paramagnetic metal species) location at specific zeolite sites. Moreover, while providing a strategy to optimizing catalyst compositions (Al distribution, Cu loading, etc.) the detection of 17O hyperfine couplings provides an effective means to selectively probe the framework lability at open-shell metal centres in zeolites. Most importantly, the exquisite sensitivity of such couplings enables to account for minute structural differences related to the Al distribution and identify the Al siting in the most stable CuII coordination, a long-standing issue in the field.

Methods

Sample preparation and treatment

Na-CHA was prepared using N,N,N-trimethyladamantanammonium hydroxide (TMAdaOH) as template following the procedure published in the patent literature73. The resulting synthesis gel was transferred to a Teflon-lined steel autoclave and heated to 140 °C for 6 days. The product was recovered by centrifugation, washed several times with deionized water, dried overnight at 75 °C and calcined in air at 550 °C for 8 h to remove the TMAdaOH. The resulting zeolite was a pure Na-CHA (Si/Al = 15) without FAU impurities.

Prior to the copper exchange, the protonated form of the zeolite was obtained by liquid ion exchange with a 10% solution of ammonia nitrate, drying in the oven (80 °C) overnight and heating at 550 °C for 3 h to remove the ammonia residues from the framework. Therefore, the doping of CuII cations inside the H-CHA sample was performed by following the ion exchange procedure described by Kevan et al.18. According to this method, approximately 1 CuII cation is incorporated per each 100 unit cells ensuring a very low copper content and a good dilution of the paramagnetic centers, which is fundamental for the application of advanced EPR techniques and allows titrating the most energetically favourable sites. The elemental percentage composition of Cu-CHA sample, determined by ICP-AES analysis, is the following: 43.70 wt% of Si, 2.72 wt% of Al and 0.03 wt% for Cu. No Na residues were detected by ICP-OES. Hence, the Cu/Al ratio is 0.005. The absolute quantification of CuII in the fully hydrated sample was estimated to be of the same order of magnitude of the total Cu content determined by ICP-AES. The SpinCount package of Bruker Xenon Software was employed to carry out the EPR quantification.

The dehydration of the zeolite was carried out at several temperatures under dynamic vacuum (final pressure <10−4 mbar) for a maximum time of 2 h.

The sample was isotopically enriched by exposing the dehydrated powder of Cu-CHA to three consecutive hydration and dehydration cycles in presence of vapours of H217O (86% isotopic enrichment supplied by Icon Services New Jersey) at 120 °C for 2 h: this method was proved to be extremely efficient in the 17O enrichment of zeolites without causing any dealumination of the framework62. At the end of the process, a 17O enriched Cu-CHA sample hydrated with H217O was obtained and, after a final dehydration step, the isotopically labelled water was removed from the framework. Finally, the dehydrated 17O labelled sample was rehydrated with H216O by merely exposing the solid to air for 24 h in order to further prove the framework substitution of 16O with 17O.

EPR measurements

The X-band (microwave frequency of 9.42 GHz) continuous-wave (CW)-EPR spectra were detected at 298 K and 77 K on a Bruker EMXmicro spectrometer. A modulation amplitude, modulation frequency and microwave power of 10 G, 100 kHz and 2 mW were used, respectively. Pulse EPR experiments were performed at 4.5 K and 20 K with X-band (microwave frequency of 9.75 GHz) and Q-band (microwave frequency of 33.8 GHz) Bruker ELEXYS 580 EPR spectrometers equipped with helium gas-flow cryostat from Oxford Inc. The magnetic field was measured with a Bruker ER035M NMR gaussmeter.

The electron-spin-echo (ESE) detected EPR spectra were recorded with the pulse sequence \(\frac{\pi }{2}-\tau -\pi -\tau -{echo}\). The pulse lengths \({t}_{\pi /2}=16\) ns and \({t}_{\pi }=32\) ns, a \(\tau\) value of 200 ns and a shot repetition rate of 3.55 kHz.

X-band hyperfine sublevel correlation (HYSCORE)74 experiments were performed with the pulse sequence \(\pi /2-\tau -\pi /2-{t}_{1}-\pi -{t}_{2}-\pi /2-\tau -{echo}\), applying a four-step phase cycle for deleting unwanted echoes. Pulse lengths of \({t}_{\pi /2}=16\) ns and \({t}_{\pi }=32\) ns and a shot repetition rate of 1.77 kHz were used. The increment of the time intervals \({t}_{1}\) and \({t}_{2}\) was 16 ns, starting from 80 to 2704 ns giving a data matrix of \(170\times 170\); the pulse delay \(\tau\) value was set to 104 ns. The time traces of HYSCORE spectra were baseline corrected with a third-order polynomial, apodized with a hamming window and zero-filled to 2048 points. After 2D Fourier transformation, the absolute-value spectra were calculated.

Q-band electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) measurements were carried out at 15 K and 20 K by employing the Davies pulse sequence75 (\(\pi -{RF}-\pi /2-\tau -\pi -\tau -{echo}\)). For 17O nuclei, strongly coupled to CuII cations, the pulse lengths used were all set to \({t}_{\pi /2}=16\) ns and \({t}_{\pi }=32\) ns. On the other hand, for 1H and 27Al nuclei weakly coupled to the unpaired electron, the first \(\pi\)-pulse was directed along the <x> direction with a length of 50 μs in order to selectively excite transitions belonging to nuclei having small hyperfine interactions. The \({RF}\) pulse length was set to \(14\) μs and a resolution of 440 points was adopted. Further experimental settings are provided in the figure captions.

All the EPR spectra were simulated by using the Easyspin package (version 6.0.0 dev 26)76.

Periodic and cluster modelling

In the present work, Chabazite structure was modelled by employing periodic boundary conditions which better describe the crystalline environment of the zeolite with respect to cluster approaches. Firstly, a purely siliceous chabazite (space group \(R\bar{3}m\)) composed by a rhombohedral lattice with 12 tetrahedral (T) sites per unit cell was considered. Therefore, two Si atoms were replaced by two Al atoms generating a model with a Si/Al ratio equal to 5. The excess of negative charge is exactly compensated by one CuII cations per unit cell. Structures with different distributions and amount (Si/Al ratio of 5 and 11) of aluminium atoms were fully optimized in P1 space group without any symmetry constrain in order to find the most stable Al configuration. Additional models in which the double positive charge of copper ions is counterbalanced by one Al substitution and a OH− group (Si/Al ratio of 11) are also reported in Supplementary Note 3. Hydrated copper species incorporated inside the CHA framework were simulated by adding water molecules to the previously optimized structures or by inserting a Cu molecular complex inside the CHA cavity and reoptimizing the whole adduct.

The periodic DFT study has been complemented with molecular cluster calculations in order to estimate the g-tensor of CuII and the relative orientations of the 17Al, 1H and 17O hyperfine interactions with respect to the g-frame. Cluster models were cut out from the corresponding optimized periodic structures. The dangling bonds were saturated with hydrogen atoms oriented along the broken bonds to keeping the local environment as in the optimized periodic models. Thus, no further geometry optimization of the cluster models was performed: the g-tensor was computed maintaining the same atomic coordinates as the ones in the relaxed periodic structures. The net charge on the clusters was set to 0 in a doublet spin state, except for the hexaaquacopper complex for which a charge of +2 was assessed.

Computational details

Periodic geometry optimizations were carried out by using the distributed parallel version of CRYSTAL17 code (PCRYSTAL)77 in the frame of Density Functional Theory (DFT) adopting the hybrid B3LYP method, Becke’s three parameters exchange functional and the correlation functional from Lee, Yang and Parr78,79. The semi-empirical dispersion corrections for the vdW interactions were employed by using the Grimme approach in the so-called DFT-D3 method in conjunction with a three-body correction80,81. The pob-TZVP basis set82 was used for all the elements during the geometry relaxation of both atomic coordinates and cell parameters. H and O atoms from extra-lattice water molecules or hydroxyl group were treated with Ahlrichs VTZP basis set83. For the prediction of 27Al, 1H and 17O hfi, single point calculations performed on the optimized structures were carried out by employing the aug-cc-pVTZ-J84 basis set for Al atoms, and the EPR-III85 for H and O atoms at B3LYP-D3. The PBE086-D3 exchange-correlation functional was also assessed for the computation of hyperfine coupling constants of aluminium, hydrogen and oxygen atoms; since the results are very similar to the B3LYP ones, they will not be commented in the following sections. Primitive Gaussians with exponents lower than 0.06 were removed in order to avoid linear dependency in the self-consistent cycle (SCF). The other elements were treated with the same basis sets used for geometry optimizations.

A default pruned grid built according to the Gauss-Legendre quadrature and Lebedev schemes having 75 radial points and a maximum number of 974 angular points in regions relevant for chemical bonding has been adopted. The accuracy of the calculation of the two electron integrals in the Coulomb and exchange series was controlled by imposing truncation criteria set at the values of 10−7 except for the pseudo-overlap of the HF exchange series which was fixed to 10−25. A shrink factor equals to 6 was used to diagonalize the Hamiltonian matrix in at least 112 k-points of the first Brillouin zone. The default value of mixing (30%) of the Kohn-Sham (KS) matrix at a cycle with the previous one was adopted. The threshold in energy variation of SCF cycles was set equal to 10−8 Hartree for both geometry relaxation and magnetic properties evaluation. The number of unpaired electrons in the unit cell of the periodic models was not locked to one in order to leave the SCF procedure to freely converge to a doublet spin state of the system wavefunction.

The EPR/NMR module of the ORCA (v4.2.1) code87 was then exploited to compute the g-tensor and the Cu hfi on molecular cluster models properly extracted from the optimized periodic structures. The complete mean-field spin-orbit operator (SOMF)88 was used for treating the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) which is not negligible for CuII cations and accounts for a consistent amount of the copper hyperfine A-tensor67,89. The potential was constructed to include one-electron terms, compute the Coulomb term in a semi-numeric way, incorporate exchange via one-center exact integrals including the spin-other orbit interaction, and include local DFT correlation (SOCFlags 1,2,3,1 in ORCA). The def2-TZVP basis sets90 was employed for Si, Al, H and O atoms and the CP(PPP)91 for Cu atom. The double-hybrid density functional theory (DHDFT) B2PLYP-D3 method92 as implemented in ORCA was adopted for the calculations in combination with the resolution of identity (RI) by using the AutoAux keyword to automatically build the auxiliary basis set. B2PLYP functional is composed by B88 exchange combined with the LYP correlation functional through two empirical parameters controlling the amount of Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange (53% of exact HF exchange) and second order perturbation theory (PT2) correlation. Only the Fermi contact (AFC) and the dipolar component (ASD) of the hyperfine coupling constant can be computed at MP2 level of theory; the spin-orbit contribution (ASO) used was determined at SCF level. In order to compare its performance, the results obtained by B2PLYP-D3 were compared with other exchange-correlation functionals and collected in Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 9.

The SCF convergence criteria were raised up to 10−8 Hartree. An integration grid composed by 770 radial points in agreement with the Lebedev scheme was chosen for all the atoms. Regarding the DHDFT method, the core electrons were not frozen in order to allow the computations of the analytical derivatives at MP2 level of theory.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in Zenodo with the identifier 10.5281/zenodo.4953846. Ref. 93.

References

Borfecchia, E. et al. Cu-CHA - a model system for applied selective redox catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 8097–8133 (2018).

Snyder, B. E. R., Bols, M. L., Schoonheydt, R. A., Sels, B. F. & Solomon, E. I. Iron and copper active sites in zeolites and their correlation to metalloenzymes. Chem. Rev. 118, 2718–2768 (2018).

Fernández, E. et al. Modeling of EPR parameters for Cu(II): application to the selective reduction of NOx catalyzed by Cu-zeolites. Top. Catal. 61, 810–832 (2018).

Iwamoto, M. et al. Copper(II) Ion-exchanged ZSM-5 zeolites as highly active catalysts for direct and continuous decomposition of nitrogen monoxide. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 0, 1272–1273 (1986).

Newton, M. A., Knorpp, A. J., Sushkevich, V. L., Palagin, D. & Van Bokhoven, J. A. Active sites and mechanisms in the direct conversion of methane to methanol using Cu in zeolitic hosts: a critical examination. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 1449–1486 (2020).

Pappas, D. K. et al. The nuclearity of the active site for methane to methanol conversion in Cu-mordenite: a quantitative assessment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 15270–15278 (2018).

Newton, M. A. et al. On the mechanism underlying the direct conversion of methane to methanol by copper hosted in zeolites; braiding Cu K-edge XANES and reactivity studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10090–10093 (2018).

Villamaina, R. et al. Speciation of Cu cations in Cu-CHA catalysts for NH3-SCR: effects of SiO2/AlO3 ratio and Cu-loading investigated by transient response methods. ACS Catal. 9, 8916–8927 (2019).

Kulkarni, A. R., Zhao, Z. J., Siahrostami, S., Nørskov, J. K. & Studt, F. Monocopper active site for partial methane oxidation in Cu-exchanged 8MR zeolites. ACS Catal. 6, 6531–6536 (2016).

Borfecchia, E. et al. Evolution of active sites during selective oxidation of methane to methanol over Cu-CHA and Cu-MOR zeolites as monitored by operando XAS. Catal. Today 333, 17–27 (2019).

Godiksen, A., Vennestrøm, P. N. R., Rasmussen, S. B. & Mossin, S. Identification and quantification of copper sites in zeolites by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Top. Catal. 60, 13–29 (2017).

Carl, P. J. & Larsen, S. C. Variable-temperature electron paramagnetic resonance studies of copper-exchanged zeolites. J. Catal. 182, 208–218 (1999).

Larsen, S. C., Aylor, A., Bell, A. T. & Reimer, J. A. Electron paramagnetic resonance studies of copper ion-exchanged ZSM-5. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 11533–11540 (1994).

Conesa, J. C. & Soria, J. Electron spin resonance of copper-exchanged Y zeolites. Part 1.—Behaviour of the cation during dehydration. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1 75, 406–422 (1979).

Gao, F. et al. Structure-activity relationships in NH3-SCR over Cu-SSZ-13 as probed by reaction kinetics and EPR studies. J. Catal. 300, 20–29 (2013).

Groothaert, M. H., Pierloot, K., Delabie, A. & Schoonheydt, R. A. Identification of Cu(II) coordination structures in Cu-ZSM-5, based on a DFT/ab initio assignment of the EPR spectra. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 5, 2135–2144 (2003).

Vanelderen, P. et al. Spectroscopy and redox chemistry of copper in mordenite. ChemPhysChem 15, 91–99 (2014).

Zamadics, M. & Kevan, L. Electron spin resonance and electron spin echo modulation studies of Cu(II) ions in the aluminosilicate chabazite: a comparison of Cu(II) cation location and adsorbate interaction with isostructural silicoaluminophosphate-34. J. Phys. Chem. 96, 8989–8993 (1992).

Yu, J. S. & Kevan, L. Formation of new copper(II) species during propylene oxidation on copper(II)-exchanged X zeolite. J. Phys. Chem. 94, 5995–6002 (1990).

Wang, A. et al. Unraveling the mysterious failure of Cu/SAPO-34 selective catalytic reduction catalysts. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–10 (2019).

Peng, L., Liu, Y., Kim, N., Readman, J. E. & Grey, C. P. Detection of Brønsted acid sites in zeolite HY with high-field 17O-MAS-NMR techniques. Nat. Mater. 4, 216–219 (2005).

Heard, C. J. et al. Fast room temperature lability of aluminosilicate zeolites. Nat. Commun. 10, 4690 (2019).

Enemark, J. H., Astashkin, A. V. & Raitsimring, A. M. Structures and reaction pathways of the molybdenum centres of sulfite-oxidizing enzymes by pulsed EPR spectroscopy. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 1129–1133 (2008).

Kaminker, I., Goldberg, H., Neumann, R. & Goldfarb, D. High-field pulsed EPR Spectroscopy for the speciation of the reduced [PV2Mo10O40]6− polyoxometalate catalyst used in electron-transfer oxidations. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 10014–10020 (2010).

Colaneri, M. J. & Vitali, J. Probing axial water bound to copper in tutton salt using single crystal 17O-ESEEM spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 122, 6214–6224 (2018).

Burdi, D., Sturgeon, B. E., Tong, W. H., Stubbe, J. & Hoffman, B. M. Rapid freeze-quench ENDOR of the radical X intermediate of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase using 17O2, H217O, and 2H2O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 281–282 (1996).

Chiesa, M. et al. Nature of the chemical bond between metal atoms and oxide surfaces: new evidences from spin density studies of K atoms on alkaline earth oxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 16935–16944 (2005).

Raitsimring, A. M. et al. Determination of the hydration number of gadolinium(III) complexes by high-field pulsed 17O ENDOR spectroscopy. ChemPhysChem 7, 1590–1597 (2006).

Palagin, D., Sushkevich, V. L. & Van Bokhoven, J. A. Water molecules facilitate hydrogen release in anaerobic oxidation of methane to methanol over Cu/mordenite. ACS Catal. 9, 10365–10374 (2019).

Koishybay, A. & Shantz, D. F. Water is the oxygen source for methanol produced in partial oxidation of methane in a flow reactor over Cu-SSZ-13. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11962–11966 (2020).

Paolucci, C. et al. Catalysis in a cage: condition-dependent speciation and dynamics of exchanged cu cations in SSZ-13 zeolites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6028–6048 (2016).

Paolucci, C., Di Iorio, J. R., Schneider, W. F. & Gounder, R. Solvation and mobilization of copper active sites in zeolites by ammonia: consequences for the catalytic reduction of nitrogen oxides. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1881–1892 (2020).

Paolucci, C. et al. Dynamic multinuclear sites formed by mobilized copper ions in NOx selective catalytic reduction. Science 357, 898–903 (2017).

Negri, C. et al. Structure and reactivity of oxygen-bridged diamino dicopper(II) complexes in Cu-ion-exchanged chabazite catalyst for NH3-mediated selective catalytic reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15884–15896 (2020).

Fickel, D. W. & Lobo, R. F. Copper coordination in Cu-SSZ-13 and Cu-SSZ-16 investigated by variable-temperature XRD. J. Phys. Chem. C. 114, 1633–1640 (2010).

Korhonen, S. T., Fickel, D. W., Lobo, R. F., Weckhuysen, B. M. & Beale, A. M. Isolated Cu2+ ions: active sites for selective catalytic reduction of NO. Chem. Commun. 47, 800–802 (2011).

Deka, U. et al. Confirmation of isolated Cu2+ ions in SSZ-13 zeolite as active sites in NH3-selective catalytic reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 4809–4818 (2012).

Godiksen, A. et al. Coordination environment of copper sites in Cu-CHA zeolite investigated by electron paramagnetic resonance. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 23126–23138 (2014).

Giordanino, F. et al. Characterization of Cu-exchanged SSZ-13: a comparative FTIR, UV-Vis, and EPR study with Cu-ZSM-5 and Cu-β with similar Si/Al and Cu/Al ratios. Dalt. Trans. 42, 12741–12761 (2013).

Llabrés i Xamena, F. X. et al. Thermal reduction of Cu2+-mordenite and re-oxidation upon interaction with H2O, O2, and NO. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 7036–7044 (2003).

Sushkevich, V. L., Smirnov, A. V. & Van Bokhoven, J. A. Autoreduction of copper in zeolites: role of topology, Si/Al ratio, and copper loading. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 9926–9934 (2019).

Turnes Palomino, G. et al. Oxidation states of copper ions in ZSM-5 zeolites. A multitechnique investigation. J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 4064–4073 (2000).

Martini, A. et al. Composition-driven Cu-speciation and reducibility in Cu-CHA zeolite catalysts: a multivariate XAS/FTIR approach to complexity. Chem. Sci. 8, 6836–6851 (2017).

Dossi, C., Fusi, A., Moretti, G., Recchia, S. & Psaro, R. On the role of carbonaceous material in the reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+ in Cu-ZSM-5 catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 188, 107–119 (1999).

Sushkevich, V. L. & Van Bokhoven, J. A. Revisiting copper reduction in zeolites: the impact of autoreduction and sample synthesis procedure. Chem. Commun. 54, 7447–7450 (2018).

Kuroda, Y. & Iwamoto, M. Characterization of cuprous ion in high silica zeolites and reaction mechanisms of catalytic NO decomposition and specific N2 adsorption. Top. Catal. 28, 111–118 (2004).

Carl, P. J. & Larsen, S. C. EPR study of copper-exchanged zeolites: effects of correlated g- and A-strain, Si/Al ratio, and parent zeolite. J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 6568–6575 (2000).

Pöppl, A., Newhouse, M. & Kevan, L. Electron spin resonance and electron spin echo modulation studies of cupric ion ion-exchanged into siliceous MCM-41. J. Phys. Chem. 99, 10019–10023 (1995).

Pöppl, A. & Kevan, L. A practical strategy for determination of proton hyperfine interaction parameters in paramagnetic transition metal ion Complexes by two-dimensional HYSCORE electron spin resonance spectroscopy in disordered systems. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 3387–3394 (1996).

Gao, F., Kwak, J. H., Szanyi, J. & Peden, C. H. F. Current understanding of Cu-exchanged chabazite molecular sieves for use as commercial diesel engine DeNOx catalysts. Top. Catal. 56, 1441–1459 (2013).

Ma, L. et al. Characterization of commercial Cu-SSZ-13 and Cu-SAPO-34 catalysts with hydrothermal treatment for NH3-SCR of NOx in diesel exhaust. Chem. Eng. J. 225, 323–330 (2013).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Hydrothermal stability of CuSSZ13 for reducing NOx by NH3. J. Catal. 311, 447–457 (2014).

Morra, E. et al. Electronic and geometrical structure of Zn+ ions stabilized in the porous structure of Zn-loaded zeolite H-ZSM-5: a multifrequency CW and pulse EPR study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 14238–14245 (2017).

Carl, P. J., Vaughan, D. E. W. & Goldfarb, D. Interactions of Cu(II) ions with framework Al in high Si:Al zeolite Y as determined from X- and W-band pulsed EPR/ENDOR spectroscopies. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 5428–5437 (2002).

Carl, P. J., Vaughan, D. E. W. & Goldfarb, D. High field 27Al ENDOR reveals the coordination mode of Cu2+ in low Si/Al zeolites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 7160–7161 (2006).

Goldfarb, D. & Kevan, L. 27Al fourier-transform electron-spin-echo modulation of Cu2+-doped zeolites A and X. J. Magn. Reson. 82, 270–289 (1989).

Freude, D., Haase, J., Pfeifer, H., Prager, D. & Scheler, G. Extra-framework aluminium in thermally treated zeolite CaA. Chem. Phys. Lett. 114, 143–146 (1985).

Hadt, R. G., Gorelsky, S. I. & Solomon, E. I. Anisotropic covalency contributions to superexchange pathways in type one copper active sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15034–15045 (2014).

Hadt, R. G. et al. Spectroscopic and DFT studies of second-sphere variants of the type 1 copper site in azurin: covalent and nonlocal electrostatic contributions to reduction potentials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16701–16716 (2012).

Yagi, S. et al. Covalency-reinforced oxygen evolution reaction catalyst. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–6 (2015).

Lim, H. K. et al. Embedding covalency into metal catalysts for efficient electrochemical conversion of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11355–11361 (2014).

Morra, E. et al. Nature and topology of metal–oxygen binding sites in zeolite materials: 17O high‐resolution EPR spectroscopy of metal‐loaded ZSM‐5. Angew. Chem. 131, 12528–12533 (2019).

Stoll, S. & Goldfarb, D. EPR Interactions—nuclear quadrupole couplings. eMagRes 6, 495–510 (2017).

Fitzpatrick, J. A. J., Manby, F. R. & Western, C. M. The interpretation of molecular magnetic hyperfine interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 084312 (2005).

Loewenstein, W. The distribution of aluminum in the tetrahedra of silicates and aluminates. Am. Mineral. 39, 92–96 (1954).

Neese, F. Prediction of electron paramagnetic resonance g-values using coupled perturbed Hartree-Fock and Kohn-Sham theory. J. Chem. Phys. 115, 11080–11096 (2001).

Neese, F. Metal and ligand hyperfine couplings in transition metal complexes: The effect of spin-orbit coupling as studied by coupled perturbed Kohn-Sham theory. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 3939–3948 (2003).

Munzarova, M. & Kaupp, M. A critical validation of density functional and coupled-cluster approaches for the calculation of EPR hyperfine coupling constants in transition metal complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A 103, 9966–9983 (1999).

Neese, F. Prediction of molecular properties and molecular spectroscopy with density functional theory: From fundamental theory to exchange-coupling. Coord. Chem. Rev. 253, 526–563 (2009).

Shadle, S. E., Hedman, B., Hodgson, K. & Solomon, E. I. Ligand K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy as a probe of ligand-metal bonding: charge donation and covalency in copper-chloride systems. Inorg. Chem. 33, 4235–4244 (1994).

Göltl, F., Bulo, R. E., Hafner, J. & Sautet, P. What makes copper-exchanged SSZ-13 zeolite efficient at cleaning car exhaust gases? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 2244–2249 (2013).

Kerkeni, B. et al. Copper coordination to water and ammonia in CuII-exchanged SSZ-13: atomistic insights from DFT calculations and in situ XAS experiments. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 16741–16755 (2018).

Zones, S. I. U.S Patent, 4,544,538 (1985).

Höfer, P., Grupp, A., Nebenführ, H. & Mehring, M. Hyperfine sublevel correlation (hyscore) spectroscopy: a 2D ESR investigation of the squaric acid radical. Chem. Phys. Lett. 132, 279–282 (1986).

Davies, E. R. A new pulse endor technique. Phys. Lett. A 47, 1–2 (1974).

Stoll, S. & Schweiger, A. EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 178, 42–55 (2006).

Dovesi, R. et al. Quantum-mechanical condensed matter simulations with CRYSTAL. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 8, e1360 (2018).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Becke, A. D. Density‐functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Peintinger, M. F., Oliveira, D. V. & Bredow, T. Consistent Gaussian basis sets of triple-zeta valence with polarization quality for solid-state calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 34, 451–459 (2013).

Eichkorn, K., Weigend, F., Treutler, O. & Ahlrichs, R. Auxiliary basis sets for main row atoms and transition metals and their use to approximate Coulomb potentials. Theor. Chem. Acc. 97, 119–124 (1997).

Hedegård, E. D., Kongsted, J. & Sauer, S. P. A. Optimized basis sets for calculation of electron paramagnetic resonance hyperfine coupling constants: aug-cc-pVTZ-J for the 3d atoms Sc–Zn. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 4077–4087 (2011).

Barone, V. Structure, thermochemistry, and magnetic properties of binary copper carbonyls by a density-functional approach. J. Phys. Chem. 99, 11659–11666 (1995).

Adamo, C. & Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 6158–6170 (1999).

Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2, 73–78 (2012).

Heß, B. A., Marian, C. M., Wahlgren, U. & Gropen, O. A mean-field spin-orbit method applicable to correlated wavefunctions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 251, 365–371 (1996).

Remenyi, C., Reviakine, R., Arbuznikov, A. V., Vaara, J. & Kaupp, M. Spin-orbit effects on hyperfine coupling tensors in transition metal complexes using hybrid density functionals and accurate spin-orbit operators. J. Phys. Chem. A 108, 5026–5033 (2004).

Weigend, F. & Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 3297–3305 (2005).

Sinnecker, S., Slep, L. D., Bill, E. & Neese, F. Performance of nonrelativistic and quasi-relativistic Hybrid DFT for the prediction of electric and magnetic hyperfine parameters in 57Fe Mössbauer spectra. Inorg. Chem. 44, 2245–2254 (2005).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical hybrid density functional with perturbative second-order correlation. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 034108 (2006).

Bruzzese, P. C. et al. 17O-EPR determination of the structure and dynamics of copper single-metal sites in zeolites. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4953846 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is part of a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant agreement no. 813209. We kindly acknowledge the Computing Center of Leipzig University for computational resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.C.B. and E.S. performed and analysed the EPR experiments with contributions from A.P. and M.C. P.C.B. performed the quantum chemical modelling supervised by B.C. S.J. and M.H. prepared the samples. M.C. conceived the project and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Susanne Mossin and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bruzzese, P.C., Salvadori, E., Jäger, S. et al. 17O-EPR determination of the structure and dynamics of copper single-metal sites in zeolites. Nat Commun 12, 4638 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24935-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24935-7

This article is cited by

-

Interplay between copper redox and transfer and support acidity and topology in low temperature NH3-SCR

Nature Communications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.