Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) represent a by-product of metabolism and their excess is toxic for hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). During embryogenesis, a small number of HSPCs are produced from the hemogenic endothelium, before they colonize a transient organ where they expand, for example the fetal liver in mammals. In this study, we use zebrafish to understand the molecular mechanisms that are important in the caudal hematopoietic tissue (equivalent to the mammalian fetal liver) to promote HSPC expansion. High levels of ROS are deleterious for HSPCs in this niche, however this is rescued by addition of antioxidants. We show that Cx41.8 is important to lower ROS levels in HSPCs. We also demonstrate a new role for ifi30, known to be involved in the immune response. In the hematopoietic niche, Ifi30 can recycle oxidized glutathione to allow HSPCs to dampen their levels of ROS, a role that could be conserved in human fetal liver.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In all vertebrates, hematopoiesis occurs in two main waves, starting with the emergence of primitive hematopoietic cells, and culminating with the specification of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) from the aortic hemogenic endothelium1,2. The very few HSPCs that are produced then colonize a niche where they can expand, the fetal liver and the caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT)3, in mammals and zebrafish, respectively. This embryonic niche is the only niche where HSPCs actively expand during the whole life of an animal4, therefore, understanding the microenvironmental signals required at the non-cell-autonomous level for HSPC expansion may allow better expansion of human HSPCs ex vivo, improving our current clinical protocols. Many studies have pointed out the role of several cytokines in this process, which led to the use of KIT-L, FLT3L, and ThPO to promote human HSPC expansion5,6,7,8,9. However, the mechanisms controlling detoxification of HSPCs from metabolic wastes have been understudied. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a by-product of HSPC metabolism and their excess is toxic, inducing their senescence10,11. Although low levels of ROS appear to be required for proper HSPC activity, including their specification from the hemogenic endothelium12 and hematopoietic reconstitution after transplantation13, an excess of ROS can lead to impaired HSPC function10. Antioxidant molecules are therefore important to maintain cellular ROS levels in cells.

Reduced glutathione (GSH) is considered to be one of the most important scavengers of ROS. GSH plays an important role in protecting cells from oxidative damage and in maintaining redox homeostasis. GSH is a tripeptide composed of cysteine, glutamic acid, and glycine, and is synthetized by γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS) and glutathione synthetase at the cellular level14. The γ-GCS-catalyzed production of γ-glutamylcysteine is the first and rate-limiting step in de novo GSH synthesis, as the availability of cysteine is limited15. This step is inhibited by GSH through a negative feedback loop, a mechanism that is central to the regulation of cellular GSH concentrations. Ultimately, two molecules of GSH can be oxidized into GSSG to eliminate one molecule of H2O2 and produce water. However, the cellular reservoir of GSH is limited and oxidized GSSG must be recycled into GSH, which can be achieved by the action of several enzymes16,17.

Gap junctions are formed by the assembly of connexins from two adjacent cells, which allows them to exchange small metabolites. In the mouse bone marrow, previous studies have shown that HSPCs could transfer ROS directly to their hematopoietic microenvironment through Cx4318. In this context, stress induced by repeated injections of 5FU led to HSPCs senescence in Cx43-deficient animals, as they were accumulating ROS. The authors of this study also showed that Cx43 was similarly necessary in the microenvironment18. Whether or not a similar process involving gap junctions occurs in the fetal liver remains to be determined. However, this raises the hypothesis of a non cell-autonomous mechanism for ROS detoxification.

Previous in vitro data have shown the possible involvement of gilt/ifi30 in this process19,20. Gilt/ifi30 was the first identified and characterized gene encoding a lysosomal redox enzyme which catalyses thiol–disulfide exchange reactions21 and was initially described as IP3022. Gilt/ifi30 encodes a 35-kDa precursor glycoprotein which is transported via the mannose 6-phosphate receptor to the endocytic pathway where the N- and C-terminal propeptides are cleaved into the 30-kDa mature form23,24. Both precursor and mature Gilt reduce disulfide bonds optimally at an acidic pH24. The cDNA encoding gilt has been identified in a variety of species including human, mouse, zebrafish25, large yellow croaker26, amphioxus27, and abalone28. In mammals, IFI30 plays an important role in major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted antigen processing by reducing the disulfide bonds of phagocytosed proteins in the endocytic compartment29. In mice, the expression of Gilt/Ifi30 was also reported in mature T cells and some fibroblasts19. Zebrafish ifi30 encodes a protein very similar to the mammalian Gilt/Ifi30, with a thioredoxin-like C-X-X-C motif that forms the reductase active site30 and mutations of either or both cysteines in the active-site abolish thiol-reductase activity of Gilt/Ifi30 24.

In the present study, we demonstrate a new physiological role for ifi30— expressed by the hematopoietic microenvironment—independent of its role during the immune response. Here we show that ifi30, expressed by the vascular niche, plays an important role in recycling GSH in order to neutralize ROS produced by HSPCs during their expansion in the zebrafish CHT. This cooperation between HSPCs and their niche is possible through connexin channels, in particular Cx41.8. Indeed, their deficiency results in the accumulation of ROS in HSPCs, while the deficiency in ifi30 results in the accumulation of ROS in the microenvironment. We also show that the expression of IFI30 is conserved in human embryos, as hematopoietic progenitors in the human fetal liver are always closely associated with IFI30+ cells, which we identify to be macrophages.

Results

Oxidative stress induces a defect of HSPC proliferation

To evaluate the impact of ROS during HSPC expansion in the CHT, we treated kdrl:mCherry;cmyb:GFP embryos with 3 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for three hours starting at ∼45 hpf, and scored the number of GFP+ cells (HSPCs) embedded within their mCherry+ (endothelial) niche. This concentration was chosen after we tested the toxicity of H2O2 on zebrafish embryos (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We observed a loss of HSPCs in the CHT as early as 48 hpf (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Fig. 1b). This was accompanied by a decrease in HSPC proliferation at 48 hpf, as measured by anti-phospho-Histone 3 (pH3) staining after exposure to H2O2 (Fig. 1c, d), showing that ROS have a toxic effect on HSPCs in the CHT. This phenotype was completely rescued by co-treating embryos with reduced GSH (Fig. 1e, f), at 10 μM, a non-toxic concentration that rescues oxidative stress as measured by Cell-Rox fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 1a, c). Therefore, the accumulation of ROS is deleterious for HSPCs, as expected, but not for endothelial cells, as their number was unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 1d). This defect can be rescued by the addition of antioxidant molecules, such as GSH. In parallel, we also tested the impact of other ROS enhancer compounds on HSPCs in the CHT at 48 hpf. We found that after 10 h of menadione treatment (10 μM), the number of HSPCs was reduced at 48 hpf (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). We also evaluated the impact of the glutathione synthesis inhibitor buthionine sulfoximine (BSO, 10 μM) and oxidized glutathione GSSG (10 μM) treatments on HSPCs in the CHT. Both treatments resulted in a significant decrease in the number of cmyb-expressing cells in the CHT (Supplementary Fig. 2c–f), which was most significant upon treatment with GSSG. These results confirm that oxidative stress is deleterious for HSPCs during their expansion in the CHT, and prompted us to further investigate the role of the glutathione pathway in this process.

a Confocal imaging in the CHT of 48 hpf kdrl:mCherry/cmyb:GFP embryos. Embryos non-treated (NT) or incubated with H2O2 (3 mM). b Quantification of HSPCs associated with ECs. Statistical analysis: unpaired two-tailed t test, ***P < 0.001. Center values denote the mean, and error values denote s.e.m. c Anti-GFP and pH3 immunostaining of NT or H2O2-treated (3 mM) cmyb:GFP embryos. d Quantification of proliferating HSPCs; statistical analysis: unpaired two-tailed t test, ***P < 0.001. Center values denote the mean, and error values denote s.e.m. e cmyb expression at 48 hpf in NT embryos, and embryos treated with H2O2 (3 mM) or GSH (10 µm). f Quantification of cmyb-expressing cells in the CHT at 48 hpf. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests, adjusted for multiple comparison, ****P < 0.0001; (n.s.) non-significant P = 0.15. Center values denote the mean, and error values denote s.e.m. Scale bars: 50 μm (a); 25 μm (c); 100 μm (e).

ifi30 is expressed in the niche and controls HSPC expansion

Previous studies have shown that Ifi30 was primarily expressed in antigen-presenting cells but also in fibroblasts in the adult mouse19. In the zebrafish embryo, we found ifi30 expression in CHT endothelial cells (ECs), more specifically in ECs of the posterior cardinal vein, as determined by in situ hybridization at 24, 33, and 48 hpf (Fig. 2a, b). This was confirmed by qPCR performed on purified kdrl:GFP+, ikaros:GFP+, mpeg1:GFP+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a–e), showing high enrichment of ifi30 in caudal ECs, as well as in macrophages, although to a lesser extent (Fig. 2c). The overexpression of ifi30 mRNA increased the number of HSPCs in kdrl:mCherry;cmyb:GFP at 48 hpf (Fig. 2d). This increase was maintained at 4dpf and correlated with an increase of rag1 expression at 4.5dpf in injected embryos (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c). However, this gain-of-function did not increase runx1 expression at 28hpf, therefore excluding any contribution of ifi30 to HSPCs emergence (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Similarly, we observed no change in the number of HSPCs at 36hpf when ifi30 full-length mRNA was injected in kdrl:mCherry;cmyb:GFP embryos (Supplementary Fig. 4e, f). These results suggest that ifi30 is primarily expressed in ECs, and can increase the proliferation of HSPCs in the CHT niche only and does not affect HSPC specification. To confirm this hypothesis, we generated kdrl:Gal4;UAS:ifi30 embryos to specifically overexpress ifi30 in ECs (Fig. 3a). First, we confirmed that our system worked efficiently by examining the expression of ifi30 in double-transgenic embryos. Kdrl:Gal4 single-positive embryos showed normal expression of ifi30 (in the CHT), whereas kdrl:Gal4;UAS:ifi30 embryos showed ectopic expression of ifi30 in all the vasculature (Fig. 3b). Next, we confirmed that the hemogenic endothelium was not impaired in these embryos, as runx1 and cmyb were normal in kdrl:Gal4;UAS:ifi30 double-positive embryos at 28 and 36hpf, respectively, indicating no change in HSPC emergence when ifi30 is overexpressed in ECs (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). However, kdrl:Gal4;UAS:ifi30 embryos showed an expansion of HSPCs in the CHT as determined by cmyb expression at 4dpf and 48 hpf (Fig. 3c–e) as well as an increase in the T-lymphocyte marker rag1 at 4.5dpf (Supplementary Fig. 5c, d), without affecting the number of ECs in the CHT (Supplementary Fig. 5e, f). Altogether, these data show that ifi30, expressed by the vascular microenvironment, can control HSPC expansion in the CHT. Previous data have suggested an antioxidant role for ifi30 in the mouse, so we then tested whether ifi30 could rescue the loss of HSPCs induced by oxidative stress.

a WISH against ifi30 at 24, 33, and 48 hpf. b Double WISH at 48 hpf against ifi30 (purple) and cdh5 (red), black arrows indicate the expression of cdh5 in dorsal aorta (DA) and the overlapping expression with ifi30 in the posterior cardinal vein (PCV). c qPCR data examining ifi30 expression (fold change relative to expression in kdrl:GFP+ head subset) in FACS-sorted cells from kdrl:GFP, ikaros:GFP, and mpeg1:GFP embryos. GFP+ cells from dissected heads and tails were sorted from 48 hpf embryos (for each transgenic line have been pooled n = 20 embryos), and each experiment was repeated independently three times. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests, adjusted for multiple comparisons, *P = 0.013; **P = 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Center values denote the mean, and error values denote s.e.m. d Imaged area in the tail at 48 hpf, as indicated by the black dotted line. Confocal imaging in the CHT of kdrl:mCherry/cmyb:GFP embryos in non-injected and ifi30-full mRNA injected embryos. The white arrows indicate kdrl and cmyb double-positive cells. e Quantification of HSPCs associated to ECs. Statistical analysis: unpaired two-tailed t test ****P < 0.0001. Center values denote the mean, and error values denote s.e.m. Scale bars: 200 μm (a, b); 50 μm (d).

a Experimental outline to generate double-transgenic kdrl:Gal4;UAS:ifi30. b WISH for ifi30 at 24 hpf in kdrl:Gal4+ embryos that were either UAS:ifi30 negative (upper) or positive (lower). c WISH for cmyb at 4 dpf in kdrl:Gal4+ embryos that were either UAS:ifi30 negative (upper) or positive (lower). d WISH against cmyb at 48 hpf in kdrl:Gal4+ embryos that were either UAS:ifi30- (upper) or UAS:ifi30+ (lower), NT and H2O2-treated. e Quantification of cmyb-expressing cells. Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests, adjusted for multiple comparisons, **P = 0.013; ****P < 0.0001. Center values of all statistical analyses denote the mean, and error values denote s.e.m. Scale bars: 200 μm (b, c), 100 μm (d).

Ifi30 controls the redox status of the CHT niche

Before testing our hypothesis, we evaluated the impact of oxidative stress on ifi30 expression by treating embryos with different ROS enhancers, such as H2O2 and menadione. Next, we also investigated the impact of the glutathione synthesis inhibitor buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) and oxidized glutathione GSSG. After treatment, we scored ifi30 expression in treated embryos by qPCR at 48 hpf. We found a significant increase in ifi30 expression following all pro-oxidant treatments tested (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Ifi30 levels were particularly enhanced by the addition of GSSG, which was also confirmed by in situ hybridization (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Next, to test the potential antioxidant activity of ifi30, we used two approaches. First, we injected wild-type embryos with ifi30-mRNA at different concentrations before challenging them with H2O2 (3 mM) for three hours starting at ∼45 hpf. We observed that the cmyb signal in the CHT was rescued proportionally to the concentration of ifi30 mRNA injected (Supplementary Fig. 6d, e). Next, we challenged kdrl:Gal4;UAS:ifi30 zebrafish embryos with H2O2 3 mM for three hours starting at ∼45 hpf (Fig. 3e, f). As expected, cmyb expression decreased in kdrl:Gal4 single-positive embryos at 48 hpf in the CHT, but the HSPC number was maintained in kdrl:Gal4;UAS:ifi30 embryos (Fig. 3f). These results confirm our hypothesis that the overexpression of ifi30 in the vascular niche can rescue the loss of HSPCs after ROS induction in the CHT. We next examined the consequences of ifi30-deficiency on HSPCs, and used the uncharacterized ifi30sa19758 mutant line which presents a point mutation in exon 2, turning the first cysteine of the catalytic site into a premature stop (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). By in situ hybridization, we found that ifi30−/− embryos exhibit a defect in definitive hematopoiesis as early as 48 hpf (Fig. 4a, b), which was maintained at 4dpf (Supplementary Fig. 8a). However, no change in runx1 and cmyb expression were detected at 28 and 36 hpf, respectively, confirming that ifi30 does not play a role at the level of the hemogenic endothelium (Supplementary Fig. 8b, c). Morpholino-mediated knockdown of ifi30 expression completely phenocopied ifi30−/− mutant embryos (Fig. 4a, b; Supplementary Fig. 7c, d; Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). Primitive erythropoiesis, vasculogenesis, and myelopoiesis were completely normal in ifi30−/− mutants (Supplementary Fig. 9a–c). However, ifi30−/− embryos exhibited a decrease in mfap4 expression (macrophage marker) at 48 hpf (Supplementary Fig. 9d, e). To confirm our observations, we used time-lapse confocal imaging to follow the behavior of HSPCs in the CHT of kdrl:mCherry;cmyb:GFP ifi30-morphants. While the number of HSPCs augmented in control embryos between 42 and 48 hpf (Supplementary Movie 1; Supplementary Fig. 9f), their number remained unchanged in ifi30-deficient embryos (Supplementary Movie 2; Supplementary Fig. 9f). These results suggest that the absence of ifi30 in the niche generates a HSPC proliferation defect in the CHT. To confirm this hypothesis, we injected control-morpholino and ifi30-morpholino in cmyb:GFP embryos and stained for both GFP and pH3 to quantify proliferating HSPCs. At 48 hpf, ifi30-morphants showed a significant decrease in the number of proliferating HSPCs (cmyb:GFP+/pH3+) within the CHT (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). This phenotype was rescued by injecting ifi30 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 10c, d). Given the potential role of ifi30 in maintaining redox homeostasis, we measured the levels of ROS in the CHT of control and ifi30-morphants at 48 hpf, by using the CellROX fluorescent probe. We could not detect any signal in control embryos, however, ifi30-morphants showed high levels of ROS in CHT-ECs (Fig. 4c), which was also confirmed by cytometry (Fig. 4d–g; for FACS strategy Supplementary Fig. 3f–l). This phenotype was also rescued by ifi30 mRNA injection (Supplementary Fig. 10e, f). Here again, the resulting loss of cmyb and/or runx1 in ifi30-morphants at 48 hpf could be rescued by adding anti-oxidants such as GSH or N-Acetyl-Cysteine (NAC) (Fig. 4h, i; Supplementary Fig. 11a–c). Surprisingly, ROS did not accumulate in HSPCs (Supplementary Fig. 11d) but rather in ECs (Fig. 4d–g) as well as in macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). Of note, the accumulation of ROS in macrophages caused their cell death, as detected by acridine orange staining (Supplementary Fig. 12c, d), in line with our observation that ifi30 mutants showed less mfap4 signal in the CHT (Supplementary Fig. 9d, e). In summary, ifi30 is expressed by the niche to control the redox status of the CHT and to therefore allow HSPCs to proliferate.

a cmyb expression at 48 hpf in wild type and ifi30−/− embryos, after the injection of control or ifi30-morpholino. b Quantification of cmyb-expressing cells. Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA, with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests, adjusted for multiple comparisons, ****P < 0.0001, (n.s.) non-significant P = 0.84; P = 0.32. Center values of all statistical analysis denote the mean, and error values denote s.e.m. c Confocal imaging in the CHT of kdrl:GFP+ cells (green), CellROX fluorescent probe (red) and merge (yellow). d Representative FACS plots showing dissociated zebrafish embryos after injection of control or (e) ifi30-morpholinos. FACS plots are gated on live cells. f Histogram plot showing the overlap of both samples, gated on kdrl+ cells. g Quantification of the percentage of kdrl:GFP+ cells affected by oxidative stress (ROS+) in ifi30-morphants (ifi30-MO) and controls (ctrl-MO) at 48 hpf. Data points are the mean of n = 4 biological replicates ± SD. Statistical analysis: unpaired two-tailed t test, **P = 0.007. Center values of all statistical analysis denote the mean, and error values denote s.e.m. h Fluorescence imaging in the CHT of kdrl:mCherry;cmyb:GFP embryos injected with control- and ifi30-MOs and treated with GSH. i Quantification of HSPCs associated with ECs. Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA, with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests, adjusted for multiple comparisons, *P = 0.028; **P = 0.008; ****P < 0.0001. The center values of all statistical analyses denote the mean, and error values denote s.e.m. Scale bars: 200 μm (a), 100 μm (c, d).

Connexin-deficiency increases ROS causing apoptosis in HSPCs

It was previously suggested that mouse adult HSPCs can transfer ROS to their microenvironment through gap junctions31. To test a similar mechanism, we used two different approaches. First, we examined the status of HSPCs in connexin41.8 (cx41.8) mutant embryos. This connexin has been previously described in zebrafish32,33 and we recently reported that cx41.8 plays an important role on ECs proliferation34. In zebrafish embryos, cx41.8 is enriched in caudal ECs, as well as in HSPCs and macrophages, to a lesser extent, as scored by qPCR on sorted kdrl:GFP+, ikaros:GFP+, and mpeg1:GFP+ cells (Fig. 5a, b). Cx41.8−/− mutants have not previously been characterized in terms of hematopoietic markers. The cx41.8−/− mutant presents a point stop mutation (C-T) in exon 2, creating a premature STOP codon (Supplementary Fig. 13a). We found that cx41.8−/− mutants showed normal HSPC specification and emergence, as scored by runx1 and cmyb staining at 28 and 36hpf, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 13b, c). However, we found that cx41.8−/− mutant embryos present a significant decrease in HSPCs in the CHT at 60 hpf and 72hpf, as scored by cmyb expression (Supplementary Fig. 13d–f). The role of gap junctions has previously been described in the mouse bone marrow, where Cx43-deficient HSPCs showed high levels of exhaustion after 5FU-induced exposure18. Furthermore, the authors showed that connexins regulate stress-induced hematopoietic regeneration following the transfer of 5FU-induced ROS from HSPC to the bone marrow niche and prevent ROS-p38-p16/INK4a-mediated HSPC cell-death35. To verify if a connexin deficiency would increase the level of ROS, we measured ROS in cx41.8−/− embryos compared with wild-type embryos at 60 hpf. We found a significant increase of CellROX-positive cells in the CHT of cx41.8−/− mutants (Supplementary Fig. 14a, b). We found that the majority of CellROX-positive cells also co-expressed GFP in cx41.8−/−;cmyb:GFP embryos, confirming the hypothesis that the loss of connexin increases ROS levels in HSPCs (Supplementary Fig. 14c). Next, we tried to rescue the loss of HSPCs observed in the CHT of cx41.8−/− mutants by GSH addition. Cx41.8−/− embryos were supplemented with GSH (10 μM) between 48 and 60 hpf, which led to a rescue in HSPCs number, as scored by cmyb staining (Fig. 5c, d). These results highlight an important role for cx41.8 during HSPC expansion in the zebrafish CHT.

a qPCR data examining cx41.8 expression (fold change relative to expression in kdrl:GFP+ head subset) in FACS-sorted cells from kdrl:GFP, ikaros:GFP and mpeg1:GFP embryos. GFP+ cells from dissected heads and tails were sorted from 48 hpf embryos. b For each transgenic line have been pooled n = 20 animals, and each experiment was repeated independently three times. Statistical analysis was completed using a one-way ANOVA, with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests, adjusted for multiple comparisons *P = 0.018; **P = 0.001; (n.s.) non-significant P = 0.26; P = 0.74. c cmyb expression at 60 hpf in wild type and cx41.8−/− embryos, and after GSH treatment. d Quantification of cmyb-expressing cells. Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA, with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests, adjusted for multiple comparisons, *P = 0.045; ****P < .0001. Center values denote the mean, and error values denote s.e.m. e Imaged area in the tail at 48 hpf, as indicated by the black dotted line. Confocal imaging of the CHT at 48 hpf of cmyb:GFP+ cells (green), CellROX fluorescent probe (red) and merge, in NT and after heptanol treatment cmyb:GFP embryos. Orthogonal projection CellROX+ cmyb:GFP+ double-positive cell after heptanol treatment. Scale bars: 100 μm (c); 25 μm (e).

Next, to evaluate the role of connexins in definitive hematopoiesis, we blocked these channels by treating cmyb:GFP embryos with heptanol or carbenoxelone36,37. As connexins are important for cell-cell communication in many tissues, we first tested the impact of this general inhibition on the cardiovascular system. We treated myl7:DsRed (myocardium) and globin:GFP (erythrocytes) transgenic embryos, with low concentrations (50 μM) of heptanol, to test the impact on blood circulation. This low concentration did not affect cardiac contractions or blood circulation (Supplementary Movies 3, 4, 5 and 6), whereas a higher concentration (1 mM) did (Supplementary Movies 7 and 8), as previously reported37. We therefore used heptanol or carbenoxelone at 50 μM. Following both treatments, HSPCs were depleted from the CHT, as measured by in situ hybridization (Supplementary Fig. 15a, b) and in cd41:GFP embryos at 48 hpf (Supplementary Fig. 15c). This was confirmed by in vivo time-lapse imaging, where kdrl:mCherry;cmyb:GFP embryos were imaged between 41 and 48 hpf (Supplementary Fig. 15d and Supplementary Movies 9 and 10). Whereas the number of HSPCs increased in non-treated embryos (Supplementary Movie 9; Supplementary Fig. 15d), we observed a loss of HSPCs in heptanol-treated embryos (Supplementary Movie 10; Supplementary Fig. 15d). Interestingly, we find that heptanol treatment phenocopied cx41.8 mutants. To ascertain that Cx41.8 was the major connexin involved in this process, we treated wild type and cx41.8−/− embryos with heptanol (between 50 and 60 hpf), and we performed in situ hybridization for cmyb at 60 hpf. We scored the number of HSPCs in the CHT. We found a significant decrease in cx41.8−/− embryos, which was not amplified by the additional heptanol treatment (Supplementary Fig. 16a–c), suggesting that Cx41.8 is the major connexin involved in this mechanism.

Next, we measured the levels of ROS in the CHT of heptanol-treated embryos. To assess the nature of the ROS accumulating cells, we treated mpeg1:GFP and kdrl:GFP embryos, to visualize CellROX in macrophages and ECs, respectively. However, unlike in ifi30-deficient embryos, ROS did never accumulate in macrophages or ECs (Supplementary Fig. 17a, b). But when we treated cmyb:GFP embryos with heptanol, we could see that CellROX staining was overlapping with GFP, indicating that ROS accumulated directly in HSPCs at 48 hpf (Fig. 5e), as expected from our previous experiment in cx41.8−/−;cmyb:GFP embryos (Supplementary Fig. 14c). By using MitoSox-RED, we confirmed this increase of ROS production in HSPCs’ mitochondria after exposure to heptanol (Supplementary Fig. 18a, b).

These high levels of ROS in HSPCs resulted in increased apoptosis in heptanol-treated cmyb:GFP embryos, as measured by TUNEL (Fig. 6a, b). Finally, the loss of HSPCs observed in the CHT of heptanol-treated cmyb:GFP embryos was also rescued by supplementation with GSH (Fig. 6c, d). However, this phenotype was not rescued by overexpressing ifi30 in ECs (kdrl:Gal4;UAS:ifi30). This was expected since the accumulation of ROS at the cell-autonomous level could not be rescued by the anti-oxidant activity of ifi30, expressed in the niche (Supplementary Fig. 18c, d). To confirm the antioxidant activity of ifi30, we generated double-transgenic gata2b:KalTA4;UAS:ifi30 embryos, to overexpress ifi30 directly in HSPCs. We found that after treatment with heptanol, the number of HSPCs in double-positive gata2b:KalTA4;UAS:ifi30 embryos was restored to normal levels (Supplementary Fig. 18e, f). Taken together, we propose a mechanism (Fig. 6e), in which ifi30, expressed by CHT-ECs and, to a lesser extent by macrophages, plays a non-cell-autonomous role during HSPC expansion in the CHT niche.

a Anti-GFP and TUNEL staining of NT and heptanol-treated cmyb:GFP embryos. b Quantification of the number of apoptotic HSPCs in both conditions. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed t test ***P < .001. Center values denote the mean and error values denote s.e.m. c Fluorescence imaging of NT and heptanol-treated (50 μM) cmyb:GFP embryos and after GSH treatment. d Quantification of cmyb:GFP+ cells. Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests, adjusted for multiple comparisons, ***P = 0007; ****P < .0001. Center values denote the mean and error values denote s.e.m. e HSPCs directly communicate with ECs and macrophages (MΦ) in the embryonic niche through connexin channels. Under normal conditions ifi30 reduces oxidized glutathione GSSG into reduced GSH, maintaining low levels of ROS in the CHT/HSPCs. The deficiency of ifi30 increases GSSG levels and increases ROS in the CHT niche, generating a defect of HSPC proliferation. The connexin-deficient embryos (cx41.8 mutants or treated with connexin inhibitors) present ROS accumulation directly in HSPCs, inducing their cell death. Scale bars: 100 μm (a–c).

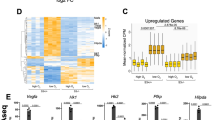

IFI30 expression is conserved in the human fetal liver

Ifi30 was initially described for its importance during antigen presentation on MHCII molecules. In order to validate this new role in the hematopoietic niche, we investigated the expression of IFI30 and CD117 in the human fetal liver, by antibody staining. We observed that the number of IFI30+ cells mirrored the number of hematopoietic progenitors (CD117+), and that both subsets peaked between 12 and 14 gestational weeks (i.e. between 14 and 16 weeks of amenorrhea) (Fig. 7a, b), during which the hematopoietic activity of the human fetal liver also peaks38. Moreover, tight associations between human HSPCs and IFI30+ cells were present in hematopoietic foci of the fetal liver (Fig. 7c). In human fetal liver, the expression of IFI30 was restricted to macrophages, as shown by IFI30/CD68 double staining performed at 13 gestational weeks (Fig. 7d). These data suggest that the expression of IFI30 has been conserved from the zebrafish CHT to the human fetal liver.

a Double immunostaining against GILT/IFI30 and CD117 on sections of human fetal liver at different stages of gestation. b Distribution of GILT/IFI30+ cells (red line), CD117+ cells (brown line), and IFI30+ cells in contact with CD117+ cells (green line). For each developmental stage, only one human fetal liver sample was used (N = 1), but three different sections were analyzed. c High magnification of double immunostaining against GILT/IFI30 (red) CD117 (brown) and nuclei (blue), on sections of human fetal liver at 13 weeks of gestation. Scale bars: 10 μm. d Double immunostaining against GILT/IFI30 (black), CD68 (cyan), and nuclei (blue) in sections of human fetal liver at 13 weeks of gestation. All red arrows point to double-stained cells. Scale bars: 100 μm (a); 25 μm (c); 200 μm. Right panel shows a magnification of the region delimited by the red dotted line (d).

Discussion

Several studies have reported that HSPCs are sensitive to oxidative stress as they reside in a hypoxic niche and are maintained in a quiescent state. Indeed, an increase of ROS levels can induce defects promoting HSPC senescence, ultimately causing premature HSPC aging as well as cell death. Our data confirm that an increase of ROS generates a defect in HSPC proliferation in the CHT niche of zebrafish embryos, which can be rescued by the addition of antioxidant molecules. GSH acts as an important antioxidant, but its cellular quantity is usually limited, which means that oxidized glutathione (GSSG) must be continuously recycled in order for cells to efficiently eliminate ROS. Many enzymes have been proposed to act as GSSG reducers, including IFI30/GILT20, which is mainly known for its role in antigen presentation29. In fact, it has been demonstrated that Ifi30 knock-out mice cannot efficiently establish an immune response against pathogens as antigen-presenting cells cannot stimulate T lymphocytes29,39. Moreover, it was shown that these mice harbor high levels of cellular ROS and oxidized GSSG, as well as mitochondrial defects20. This has potentially been further explained by in vitro experiments showing involvement of Ifi30, in the balance of GSH/GSSG in mouse fibroblasts19.

In our in vivo study on zebrafish embryos, we show that ifi30 plays an important, newly identified role in the CHT niche. First, we show that ifi30 is specifically expressed in ECs of the CHT niche. EC overexpression of ifi30 results in an increase in the number of HSPCs in the CHT, and rescues the loss of HSPCs following challenge with ROS treatment. The novel finding of this study is therefore that ifi30 functions independently of its immunological role and plays a role that was previously underestimated, as a regulator of the redox status in the hematopoietic niche. We show that ifi30, expressed in the niche, acts as an antioxidant, and behaves as such, since its expression is highly increased after an oxidative stimulus. As a thiol-reductase, ifi30 can reduce protein disulfide bonds contained in oxidized glutathione GSSG produced by HSPCs into reduced GSH. However, since ifi30 is expressed only in CHT-ECs and macrophages, this raises the question of the accessibility of HSPC-derived metabolites (ROS or oxidized GSSG). Transportation of these metabolites through cellular channels implies a high proximity between HSPCs and niche vascular ECs, something which has been previously shown by electron microscopy and termed “HSPC cuddling”3. Moreover, it was recently suggested that in the mouse bone marrow, adult HSPCs transfer ROS to their microenvironment through gap junctions31,35. In the present study, we have identified a connexin that is important for the function of the zebrafish hematopoietic niche. In particular, we have shown that cx41.8−/− mutants present a significant decrease in HSPCs in the CHT niche between 48 and 60 hpf, as well as embryos treated with heptanol or carbenoxelone. In these connexin-inhibited embryos, we show that HSPCs accumulate ROS at the cell-autonomous level, inducing their apoptosis, emphasizing the role of gap junctions in this process. To understand the interaction between HSPCs and their niche, several lines of evidence must be examined. The loss of HSPCs (due to connexin- or ifi30-deficiencies) can be rescued by the addition of NAC or GSH, which suggests that the glutathione pathway represents the major ROS scavenging pathway in the zebrafish CHT. In this pathway, a superoxide dismutase (sod) converts the superanion O2.− into H2O2, which is then converted into H2O by a GSH peroxidase (gpx), that uses 2 molecules of GSH to form GSSH and 2 molecules of H2O. When gap junctions are blocked, HSPCs accumulate ROS and enter apoptosis, but they can be rescued when they overexpress ifi30, which is only expressed in the microenvironment. This suggests that HSPCs can perform the first steps of the detoxification (using sod and a gpx enzyme that needs to be identified), but cannot recycle oxidized glutathione (GSSG), a task that is mainly performed by the vascular niche. Indeed, as the amount of reduced GSH is limited in each cell, a failure to recycle GSSG would result in the accumulation of ROS, which we observe in Cx-deficient embryos. This raises the hypothesis of an exchange of reduced and oxidized glutathione exists between HSPCs and their microenvironment, through gap junctions.

Finally, we have demonstrated that this newly identified role of ifi30 in the zebrafish CHT is also conserved in human fetal liver. In particular, we observe that IFI30 is expressed in macrophages that are in close contact with hematopoietic progenitors (CD117+) in the fetal liver. These data reinforce the importance of macrophages to assist HSPCs during their embryonic life. While adult bone marrow macrophages have been described to retain HSPCs in the adult mouse bone marrow40,41,42,43, the importance of macrophages for HSPC migration from the aorta to the CHT has been recently highlighted in the zebrafish embryo44,45. While sterile inflammation has proven to be essential to HSPC emergence and expansion40,41,42 our data show a further example of how common factors of the immune toolbox have been reassigned to the establishment and maturation of the hematopoietic system.

Methods

Ethical statement

Fish were raised according to FELASA and swiss guidelines46. No authorization was required since all experiments were performed before 5 days post fertilization. All efforts were made to comply to the 3R guidelines. The human sample study protocol was approved by the Commission Cantonale d’Ethique de la Recherche (CCER:2020-00582), University of Geneva, Switzerland. Informed written consent for both the autopsy and the further use of coded material for research purposes was obtained from the parents. Fetuses were recruited according to the following criteria: parental written approval to the use of samples for research purposes, gestational age, absence of liver pathology upon histological evaluation, adequate morphology, and in particular no tissue autolysis.

Zebrafish husbandry

AB* zebrafish strains, along with transgenic strains and mutant strains, were kept in a 14/10 h light/dark cycle at 28 °C. Embryos were obtained as described previously47. In this study we used the following transgenic lines: Tg(kdrl:Gal4)bw948, Tg(cmyb:GFP)zf16949, Tg(kdrl:Has.HRASmCherry)s89650, Tg(kdrl:GFP)s84351, Tg(mpeg1:mCherry)gl2352, Tg(mpeg1:GFP)gl2252, Tg(fli1a:nls-mCherry)ubs1053, Tg(gata2b:KalTA4)sd3254, Tg(globin:GFP)cz332555, Tg(myl7:DsRED)s87950, and the mutant line leot1/t1 (referred to as Cx41.8−/−) 33.

Generation of transgenic animals

For Tg(UAS:ifi30) fish generation, a Tol2 vector containing 4xUAS promoter, the sequence for ifi30 (including STOP codon), and a poly-adenylation signal sequence was generated by sub-cloning. Zebrafish embryos were injected with 25 pg of the final Tol2 vector, and with 25 pg Tol2 transposase mRNA. Injected F0 adults were mated to AB zebrafish, and F1 offspring were screened to assess germline integration of the Tol2 construct. Starting with the F2, adults were crossed to the Tg(kdrl:Gal4) and/or Tg(gata2b:KalTA4) to perform experiments. After WISH, embryos were genotyped by PCR. Genotyping primers are listed in Supplemantaryemental Table S1.

Identification of ifi30 mutant line

The ifi30sa19758 mutant line possesses a point stop mutation C-T in exon 2, in the first cysteine of the catalytic site. The ifi30sa19758 line is available at the ZFIN repository (ZFIN ID: ZDB-GENE-030131-8447) from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (ZIRC). The ifi30sa19758 used in this study was subsequently outcrossed with WT AB* for clearing of potential background mutations derived from the random ENU mutagenesis from which this line was derived. The ifi30sa19758 homozygous mutant is referred in the paper as ifi30−/− and was obtained by incrossing our ifi30sa19758/AB strain. Genotyping was performed by PCR of the ifi30 gene followed by sequencing. Genotyping primers are indicated in Supplemantaryemental Table S1.

Drug exposure and analysis

The concentrations of all chemical treatments were chosen based on previous studies which established that these doses produced sub-lethal effects in zebrafish embryos, with no gross malformations11,36,56. All compounds used in these experiments were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Zebrafish embryos were exposed for three hours to 3 mM of H2O2 starting at ∼45hpf. For chemical treatments, the embryos were exposed to 10 µm of NAC or L-glutathione reduced (GSH), Menadione, BSO, oxidized glutathione (GSSG) from 36hpf to 48 hpf in embryo E3 medium. New embryo medium with the fresh compound was administered daily until 4dpf. For heptanol and carbenoxolone treatments, wild-type zebrafish embryos were exposed to 50 µM doses from 36 to 48 hpf, and cx41.8 mutants from 48 to 60 hpf. After exposure, fish were fixed and the expression of different markers was tested by WISH. Embryos were phenotyped based on the expression of the markers and eventually genotyped (when treating ifi30 mutants or kdrl:gal4;UAS:ifi30 embryos).

Synthesis of full-length ifi30 mRNA

mRNA was reverse transcribed using mMessage mMachine kit SP6 (Ambion) from a linearized pCS2+ vector containing PCR-amplified product. After transcription, RNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction. Oligonucleotide primers used are listed in Supplemantaryemental Table 1.

Morpholino injections

The ifi30-morpholino oligonucleotide (MOs) and control-MO were purchased from GeneTools (Philomath, OR) and are listed in Supplemantaryemental Table 2. MO efficiency was tested by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from total RNA extracted from ∼10 embryos at 48 hpf using primers listed in Supplemantaryemental Table S2. In all experiments, 12 ng of ifi30-MO were injected per embryo.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization and analysis

Digoxigenin and fluorescein-labeled probes cmyb, runx1, cdh5, pu.1, gata1, flk1, mfap4, and rag1 were previously described57. Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) was performed on 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed embryos following the protocol described in ref. 58. All injections were repeated three separate times. Analysis was performed using the unpaired Student t-test or ANOVA Multiple comparison-test (GraphPad Prism). Embryos were imaged in 100% glycerol, using an Olympus MVX10 microscope. Oligonucleotide primers used to amplify and clone cDNA for the production of the ifi30 ISH probe are listed in Supplemantaryemental Table S1.

Cell sorting and flow cytometry

Embryos were incubated with a Liberase-Blendzyme 3 (Roche) solution for 90 min at 33 °C, then dissociated and resuspended in 0.9× PBS-1% fetal calf serum, as previously described57. We excluded dead cells by staining with SYTOX-red (Life Technologies), DAPI, or DRAQ7 (Thermo Fischer Scientific) stainings. Cell sorting was performed using an Aria II (BD Biosciences, software diva v6.1.3) or a BIORAD S3 cell sorter. For ROS detection, 25–30 embryos (kdrl:eGFP) were dissociated in 0.9% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 0.2 mg/mL liberase (Roche) for 2 h at 32 °C with agitation. Cell pellets were washed in PBS 0.9% containing 1% Fetal Calf Serum and centrifuged again for 5 mins. The supernatant was removed. Cells were placed in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with 5 mM CellROX deep red reagent (ThermoFisher) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Cell suspension was passed through a 40 mm filter prior to flow cytometry. Data were acquired on a LSR2Fortessa (BD Biosciences, software diva8.0.2) and analyzed with FlowJo.

Quantitative real-time PCR and analysis

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a Superscript III kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using KAPA SYBR FAST Universal qPCR Kit (KAPA BIOSYSTEMS) and run on a CFX connect real-time system (Bio Rad). All primers are listed in Supplemantaryemental Table S3. Analysis was performed using an unpaired Student t test in GraphPad Prism. Each qPCR experiment was performed using biological triplicates. For experiments using qPCR, each n represents an average of biological triplicates from a single experiment. Experiments were repeated at least three times, and fold-change averages from each experiment were combined.

Oxidative stress detection in vivo

Whole-mount staining with the MitoSOX and CellROX (Life Technologies) oxidative stress probes was performed on living zebrafish embryos at 48 hpf, following the methods described56. Embryos injected with ifi30-MO or control-MO were exposed with 5 µM MitoSOX or CellROX solutions for 30 min at 28 C°, followed by analysis using fluorescence or confocal microscopy.

Confocal microscopy and immunofluorescence staining

Transgenic fluorescent embryos were embedded in 1% agarose in a glass-bottom dish. Immunofluorescence double staining was performed as described previously57, with chicken anti-GFP (1:400; Life Technologies) and rabbit anti-phospho-histone 3 (pH3) antibodies (1:250; Abcam). AlexaFluor488-conjugated anti-chicken secondary antibody (1:1000; Life Technologies) and AlexaFluor594-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000; Life Technologies) were subsequently utilized to reveal primary antibodies. Confocal imaging was performed using a Nikon inverted A1r spectral microscope.

Apoptotic-cell detection

Apoptotic cells were detected by incubating live embryos in 10 µg/mL Acridine Orange (Cayman Chemical) in E3 for 30 min followed by 3 × 10 min-washes in E3. Embryos were anesthetized with Tricaine, mounted on glass-bottom dishes in 0.7% agarose, and imaged.

Apoptotic cells were also examined by TUNEL assay. Embryos were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C. After gradual rehydration, the embryos were permeabilized with 25 µg/ml proteinase K for 10 minutes at 28 °C followed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and incubated with 90 µl labeling solution plus 10 µl enzyme solution (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Roche) at 37 °C for 2 h. They were washed three times with PBT for 5 min each, and the images were examined by confocal microscopy.

Time-lapse imaging and analysis

For time-lapse imaging, Tg(kdrl:mCherry;cmyb:GFP) embryos were anaesthetized with 0.03% Tricaine (Sigma), and embedded in 1% agarose in a 60 mm glass-bottom dish. The embryos were imaged at 28.5 °C with a confocal Nikon inverted A1r spectral microscope. Scanning with 20x water immersion objective, z-stalks were acquired with a step size of 7 μm with an interval of 7 min for 6 h in the control and ifi30-morphants starting at ∼42 hpf, and an interval of 10 min for 7 h in non-treated and during heptanol treatment starting at ∼41 hpf. The analysis of cmyb:GFP+ cells in all experiments was performed using IMARIS image software (version 9.7.2). The 3D + t acquisitions were manually oriented to have the CHT horizonal. Then, when required, the presence of a 3D translational drift was corrected by detecting structures that are morphologically stable (therefore not intrinsically moving during the time course). Subsequently, a background subtraction was performed on the GFP channel. Finally, for display purposes, maximum intensity projections were used and the intensity of each channel of the images was set in order to saturate the bottom 1% and the top 0.1% of all pixel values. Movies were recorded using Lanczos’ resampling with a kernel of size 3 and quantized over 8 bits per channel afterwards.

Human fetal liver specimens and immunostaining

Unstained 4 μm sections on whole charged slides were prepared from paraffin blocks. Double staining was identified using a Ventana Discovery Autostainer. IFI30/CD117 double immunostaining: for the first sequence, we used the monoclonal rabbit anti-CD117/KIT antibody (Clone YR 145, Cell Marque 117R-16, dilution 1:500). Antigen retrieval was performed by heating slides for 64 min in a EDTA pH 8.0 solution at 95 °C. Slides were incubated with the anti-CD117 antibody for 60 min at 36 °C, and detection was performed using an Amplification Kit (Ventana N°760-080) and subsequently the UltraView Universal DAB detection Kit (Ventana N°760-500). For the second sequence, with the polyclonal rabbit anti-GILT/IFI30 antibody (PA5-21533, Thermo Fisher, dilution 1:5000), slides were incubated with the anti-IFI30 antibody for 32 mins at 36 °C. This step was followed by detection using the UltraView Universal APR detection Kit (Ventana N°760-501). IFI30/CD68 double immunostaining: for the first sequence with the polyclonal rabbit anti-GILT/IFI30 antibody (PA5-21533, Thermo Fisher, dilution 1:5000), antigen retrieval was performed by heating slides for 64 mins in an EDTA pH 8.0 solution at 95 °C. Slides were incubated with the anti-IFI30 antibody for 32 min at 36 °C and detection was performed using an UltraView Universal DAB detection Kit (Ventana N°760-500). For the second sequence, the monoclonal mouse anti-CD68 antibody (Clone PG-M1, M0876, dilution 1:100) was incubated for 16 min at 37 °C. This step was followed by detection using an OmniMap-HRP Teal (Ventana N°760-4310). The images were acquired with a Nikon NIS-Elements Version 5.02 microscope. Analysis was performed manually in Image J by counting the number of positive cells on three different slides (one human fetal liver for each developmental stage).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All raw data are freely accessible on the following link: https://doi.org/10.26037/yareta:hxkhluu4szdxnmhegpydld743m, or will be provided by the authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Bertrand, J. Y. et al. Haematopoietic stem cells derive directly from aortic endothelium during development. Nature 464, 108–111 (2010).

Bertrand, J. Y. & Traver, D. Hematopoietic cell development in the zebrafish embryo. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 16, 243–248 (2009).

Tamplin, O. J. et al. Hematopoietic stem cell arrival triggers dynamic remodeling of the perivascular niche. Cell 160, 241–252 (2015).

Mahony, C. B. & Bertrand, J. Y. How HSCs colonize and expand in the fetal niche of the vertebrate embryo: an evolutionary perspective. Front Cell Dev. Biol. 7, 34 (2019).

Aiuti, A. et al. Lentiviral hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy in patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Science 341, 1233151 (2013).

Cavazzana-Calvo, M. et al. Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease. Science 288, 669–672 (2000).

Petzer, A. L., Zandstra, P. W., Piret, J. M. & Eaves, C. J. Differential cytokine effects on primitive (CD34 + CD38-) human hematopoietic cells: novel responses to Flt3-ligand and thrombopoietin. J. Exp. Med. 183, 2551–2558 (1996).

Schuster, J. A. et al. Expansion of hematopoietic stem cells for transplantation: current perspectives. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 1, 12 (2012).

Walasek, M. A., van Os, R. & de Haan, G. Hematopoietic stem cell expansion: challenges and opportunities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1266, 138–150 (2012).

Ludin, A. et al. Monocytes-macrophages that express alpha-smooth muscle actin preserve primitive hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow. Nat. Immunol. 13, 1072–1082 (2012).

Rissone, A. et al. Reticular dysgenesis-associated AK2 protects hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell development from oxidative stress. J. Exp. Med. 212, 1185–1202 (2015).

Harris, J. M. et al. Glucose metabolism impacts the spatiotemporal onset and magnitude of HSC induction in vivo. Blood 121, 2483–2493 (2013).

Lewandowski, D. et al. In vivo cellular imaging pinpoints the role of reactive oxygen species in the early steps of adult hematopoietic reconstitution. Blood 115, 443–452 (2010).

Meister, A. & Anderson, M. E. Glutathione. Annu Rev. Biochem. 52, 711–760 (1983).

Zhang, H. & Forman, H. J. Redox regulation of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 41, 509–515 (2009).

Diaz Vivancos, P., Wolff, T., Markovic, J., Pallardo, F. V. & Foyer, C. H. A nuclear glutathione cycle within the cell cycle. Biochem. J. 431, 169–178 (2010).

Sies, H. Glutathione and its role in cellular functions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 27, 916–921 (1999).

Taniguchi Ishikawa, E. et al. Connexin-43 prevents hematopoietic stem cell senescence through transfer of reactive oxygen species to bone marrow stromal cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 9071–9076 (2012).

Bogunovic, B., Stojakovic, M., Chen, L. & Maric, M. An unexpected functional link between lysosomal thiol reductase and mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8855–8862 (2008).

Chiang, H. S. & Maric, M. Lysosomal thiol reductase negatively regulates autophagy by altering glutathione synthesis and oxidation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51, 688–699 (2011).

Arunachalam, B., Phan, U. T., Geuze, H. J. & Cresswell, P. Enzymatic reduction of disulfide bonds in lysosomes: characterization of a gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase (GILT). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 745–750 (2000).

Luster, A. D., Weinshank, R. L., Feinman, R. & Ravetch, J. V. Molecular and biochemical characterization of a novel gamma-interferon-inducible protein. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 12036–12043 (1988).

Lackman, R. L. & Cresswell, P. Exposure of the promonocytic cell line THP-1 to Escherichia coli induces IFN-gamma-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase expression by inflammatory cytokines. J. Immunol. 177, 4833–4840 (2006).

Phan, U. T., Arunachalam, B. & Cresswell, P. Gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase (GILT). Maturation, activity, and mechanism of action. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25907–25914 (2000).

Phan, U. T., Maric, M., Dick, T. P. & Cresswell, P. Multiple species express thiol oxidoreductases related to GILT. Immunogenetics 53, 342–346 (2001).

Zheng, W. & Chen, X. Cloning and expression analysis of interferon-gamma-inducible-lysosomal thiol reductase gene in large yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea). Mol. Immunol. 43, 2135–2141 (2006).

Liu, N., Zhang, S., Liu, Z., Gaowa, S. & Wang, Y. Characterization and expression of gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase (GILT) gene in amphioxus Branchiostoma belcheri with implications for GILT in innate immune response. Mol. Immunol. 44, 2631–2637 (2007).

De Zoysa, M. & Lee, J. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of interferon-gamma inducible lysosomal thiol reductase (GILT)-like cDNA from disk abalone (Haliotis discus discus). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 96, 221–229 (2007).

Maric, M. et al. Defective antigen processing in GILT-free mice. Science 294, 1361–1365 (2001).

Cui, X. W. et al. Molecular and biological characterization of interferon-gamma-inducible-lysosomal thiol reductase gene in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 33, 1133–1138 (2012).

Ludin, A. et al. Reactive oxygen species regulate hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal, migration and development, as well as their bone marrow microenvironment. Antioxid. Redox Signal 21, 1605–1619 (2014).

Irion, U. et al. Gap junctions composed of connexins 41.8 and 39.4 are essential for colour pattern formation in zebrafish. Elife 3, e05125 (2014).

Watanabe, M. et al. Spot pattern of leopard Danio is caused by mutation in the zebrafish connexin41.8 gene. EMBO Rep. 7, 893–897 (2006).

Denis, J. F. et al. KLF4-Induced Connexin40 expression contributes to arterial endothelial quiescence. Front. Physiol. 10, 80 (2019).

Singh, A. K. & Cancelas, J. A. Gap junctions in the bone marrow lympho-hematopoietic stem cell niche, leukemia progression, and chemoresistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21030796 (2020).

Casano, A. M., Albert, M. & Peri, F. Developmental apoptosis mediates entry and positioning of microglia in the zebrafish brain. Cell Rep. 16, 897–906 (2016).

Muto, A. & Kawakami, K. Imaging functional neural circuits in zebrafish with a new GCaMP and the Gal4FF-UAS system. Commun. Integr. Biol. 4, 566–568 (2011).

Goldman, O., Cohen, I. & Gouon-Evans, V. Functional blood progenitor markers in developing human liver progenitors. Stem Cell Rep. 7, 158–166 (2016).

Hastings, K. T., Lackman, R. L. & Cresswell, P. Functional requirements for the lysosomal thiol reductase GILT in MHC class II-restricted antigen processing. J. Immunol. 177, 8569–8577 (2006).

Kim, P. G. et al. Interferon-alpha signaling promotes embryonic HSC maturation. Blood 128, 204–216 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Inflammatory signaling regulates embryonic hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell production. Genes Dev. 28, 2597–2612 (2014).

Sawamiphak, S., Kontarakis, Z. & Stainier, D. Y. Interferon gamma signaling positively regulates hematopoietic stem cell emergence. Dev. Cell 31, 640–653 (2014).

Winkler, I. G. et al. Bone marrow macrophages maintain hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niches and their depletion mobilizes HSCs. Blood 116, 4815–4828 (2010).

Li, D. et al. VCAM-1(+) macrophages guide the homing of HSPCs to a vascular niche. Nature 564, 119–124 (2018).

Travnickova, J. et al. Primitive macrophages control HSPC mobilization and definitive haematopoiesis. Nat. Commun. 6, 6227 (2015).

Alestrom, P. et al. Zebrafish: housing and husbandry recommendations. Lab Anim. 54, 213–224 (2020).

Westerfield, M. The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). 4th edn, (University of Oregon Press, 2000).

Kim, A. D. et al. Discrete Notch signaling requirements in the specification of hematopoietic stem cells. EMBO J. 33, 2363–2373 (2014).

North, T. E. et al. Prostaglandin E2 regulates vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Nature 447, 1007–1011 (2007).

Chi, N. C. et al. Foxn4 directly regulates tbx2b expression and atrioventricular canal formation. Genes Dev. 22, 734–739 (2008).

Jin, S. W., Beis, D., Mitchell, T., Chen, J. N. & Stainier, D. Y. Cellular and molecular analyses of vascular tube and lumen formation in zebrafish. Development 132, 5199–5209 (2005).

Ellett, F., Pase, L., Hayman, J. W., Andrianopoulos, A. & Lieschke, G. J. mpeg1 promoter transgenes direct macrophage-lineage expression in zebrafish. Blood 117, e49–e56 (2011).

Heckel, E. et al. Oscillatory flow modulates mechanosensitive klf2a expression through trpv4 and trpp2 during heart valve development. Curr. Biol. 25, 1354–1361 (2015).

Butko, E. et al. Gata2b is a restricted early regulator of hemogenic endothelium in the zebrafish embryo. Development 142, 1050–1061 (2015).

Ganis, J. J. et al. Zebrafish globin switching occurs in two developmental stages and is controlled by the LCR. Dev. Biol. 366, 185–194 (2012).

Mugoni, V., Camporeale, A. & Santoro, M. M. Analysis of oxidative stress in zebrafish embryos. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/51328 (2014).

Mahony, C. B., Fish, R. J., Pasche, C. & Bertrand, J. Y. tfec controls the hematopoietic stem cell vascular niche during zebrafish embryogenesis. Blood 128, 1336–1345 (2016).

Thisse, C. & Thisse, B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat. Protoc. 3, 59–69 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all lab members for their comments. We would also like to thank Pr. B. Kwak for sharing her expertise on connexins, and N. Liaudet from the Bioimaging platform for his help with the Imaris software. J.Y.B. was endorsed by a chair in life sciences funded by the Gabriella Giorgi-Cavaglieri Foundation and is also funded by the Swiss National Fund (grants #31003_166515 and 310030_184814).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.C. performed experiments and established the UAS:ifi30 transgenic line. P.C. and T.P. performed the work on the connexin mutant. C.B.M. performed FACS-sorting cells from kdrl:GFP embryos. P.B. and A-L.R. performed immunostainings on human fetal samples. T.P., C.M., and A-L.R. edited the manuscript. P.C. and J.Y.B. designed experiments, performed analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cacialli, P., Mahony, C.B., Petzold, T. et al. A connexin/ifi30 pathway bridges HSCs with their niche to dampen oxidative stress. Nat Commun 12, 4484 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24831-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24831-0

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.