Abstract

The recent emergence of strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae associated with treatment failures to ceftriaxone, the foundation of current treatment options, has raised concerns over a future of untreatable gonorrhea. Current global data on gonococcal strains suggest that several lineages, predominately characterized by mosaic penA alleles, are associated with elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to extended spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs). Here we report on whole genome sequences of 813 N. gonorrhoeae isolates collected through the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project in the United States. Phylogenomic analysis revealed that one persisting lineage (Clade A, multi-locus sequence type [MLST] ST1901) with mosaic penA-34 alleles, contained the majority of isolates with elevated MICs to ESCs. We provide evidence that an ancestor to the globally circulating MLST ST1901 clones potentially emerged around the early to mid-20th century (1944, credibility intervals [CI]: 1935–1953), predating the introduction of cephalosporins, but coinciding with the use of penicillin. Such results indicate that drugs with novel mechanisms of action are needed as these strains continue to persist and disseminate globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neisseria gonorrhoeae gonorrhoeae, the causative agent of the sexually transmitted infection gonorrhea, was ranked as one of the most “urgent” threats in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States 2019 report1. Gonorrhea is the second most reported infectious condition in the United States (583,405 cases were reported to CDC in 2018) with an estimated yearly incidence of 87 million infections worldwide2,3. Historically, beginning with sulfonamides in the late 1930s, the gonococcus has successively developed resistance to all previously recommended antimicrobial drugs used for treatment of gonorrhea (e.g., penicillins, tetracyclines, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and extended-spectrum cephalosporins [ESCs])4. This led to several countries including the United States in 2010 to recommend combination therapy for gonorrhea treatment as it was theorized that other co-administered agents (e.g., doxycycline or azithromycin) would delay the emergence and dissemination of cephalosporin-resistant gonococcal strains5. Following the worldwide rise in cefixime resistance, treatment guidelines changed, and ceftriaxone became the cornerstone of therapy6,7. Beginning in 2015, doxycycline was removed as part of combination therapy leaving ceftriaxone (250 mg injected intramuscularly) and azithromycin (1 g taken orally) as the only recommended therapy for uncomplicated gonorrhea8. In 2020, combination therapy was no longer recommended and ceftriaxone (500 mg, 1 g for persons weighing ≥150 kg) became the only recommended regimen for uncomplicated gonorrhea9.

The gonococcus has adapted a myriad of strategies enabling it to survive within different niches of the human host and in the presence of antimicrobials, including the use of (i) efflux pumps, (ii) target modification of antimicrobial substrates, (iii) reduction of outer membrane permeability, among others10,11. The capacity of gonococci to develop antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is largely attributed to horizontal gene transfer or specific mutations4. The gonococcus is naturally competent for genetic transformation and can import DNA from extracellular sources into its genome by homologous recombination10. Commensal Neisseria species (e.g., N. cinerea, N. flavescens, N. perflava, etc.) and even other gonococci that share the same host niche can be reservoirs of this extracellular DNA10,12,13. Reduced susceptibility to ESCs has been primarily associated with an altered penA gene encoding penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 24. PBP2 is an important transpeptidase (TPase) among a collection of four PBPs including: PBP1 (ponA; TPase), PBP3, and PBP4 (carboxypeptidase/endopeptidase) necessary for biosynthesis of peptidoglycan, the main component of the cell wall14,15. All β-lactams antimicrobials (e.g., penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, and carbacephems) exert their lethal action by binding and inhibiting PBPs that are necessary for inserting cross-linkage structures into the cell wall10,14,15,16. PBP2 is particularly important as it is the main lethal target of β-lactam antibiotics used for treatment of gonorrhea10,16. By the 1980s, studies had noted penicillin-resistant strains with altered forms of PBP2 characterized by an Asp-345 insertion and other mutations, which was later attributed to interspecies recombination with Neisseria commensals17,18.

As early as the 2000s, gonococcal strains were observed with reduced susceptibility to oral cephalosporins (e.g., cefixime, cefdinir, cefpodoxime, cefepime, etc.) in Japanese metropolitan areas, where their usage was common19,20,21,22. These isolates were shown to harbor “mosaic” penA alleles, which can contain 60–70 amino acid changes in PBP2 compared to a wildtype (WT) PBP2 sequence, and originate from homologous recombination with Neisseria commensals7,10,23,24. Some of the earliest isolates with reduced susceptibility to cefixime were collected from Japan in the 1990s–2000s and contained mosaic penA-107,19,22,24. In 2009, the first mosaic penA-34 (≥98% sequence homology to penA-10) harboring isolates with reduced susceptibility to cefixime were described in the United States, although recent whole genome sequencing (WGS) and AMR determinant screening suggest that these strains had emerged as early as 200625,26. Currently, strains with mosaic penA-34 and its derivatives (mosaic alleles sharing ≥98% sequence homology) are prevalent in the United States and globally27,28,29,30. In addition, certain amino acid substitutions in the mosaic penA genes observed in gonococcal strains such as WHO-Y (penA-44; A501P), H041 (penA-37, A311V, A316P, and T483S), and clones of strain FC428 (penA-60; A311V and T483S) have been shown to confer high-level cefixime (CFMHL, minimum inhibitory concentrations [MICs] ≥1 µg/mL) and ceftriaxone MICs (CROHL, MICs ≥0.5 µg/mL)6,31,32. Compensatory changes in secondary loci such as the acnB gene have also been shown to increase bacterial in vitro fitness in isolates with mosaic penA alleles, which have been demonstrated to impart a biological fitness cost33. Additional pathways for resistance to β-lactams include the acquisition of multiple chromosomal mutations that additively increase resistance: mutations in outer membrane porins (PorB1B), in the PilQ secretin of type IV pili, and in mtr4,33,34,35,36,37,38,39.

In the United States, sentinel surveillance of N. gonorrhoeae is conducted through CDC’s Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP). Notably, GISP includes a system of sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics that collects urethral specimens for culture and determines the antibiotic MICs to selected drugs, currently or previously used to treat gonorrhea, each month from the first 25 male patients with gonococcal urethritis40. GISP uses MIC values to monitor trends in antimicrobial susceptibility over time41. Based on GISP data, the percentage of isolates with elevated cefixime MICs (CFMem; MIC ≥0.25 µg/mL) peaked at 1.4% nationally before CDC updated its treatment recommendations in 2012 but has since fluctuated around 0.4% between 2013 and 201841. In addition, the percentage of GISP isolates that exhibited elevated ceftriaxone MICs (CROem; MIC ≥ 0.125 µg/mL) has fluctuated around 0.2% between 2012 and 201841.

In this observational study, we examined the genomic diversity and AMR determinants of circulating N. gonorrhoeae lineages collected by GISP in the United States between 2005 and 2017. We were primarily interested in how gonococcal susceptibility patterns to ESCs have emerged over time in the United States, and how such strains have evolved and acquired mutations in penA following previous reports26,28,29. In addition, we conducted a global phylogenomic comparison on a subset of isolates with elevated cephalosporin MICs collected from the United States and other countries. From this, we assessed the genetic similarity of mosaic penA containing N. gonorrhoeae strains and estimated their likely emergence and spread.

Results

Strain diversity and distribution

A variety of diverse sequence types (STs) were detected from the 813 isolates. Ninety multi-locus sequencing typing (MLST) STs were identified, with the majority of isolates belonging to five major STs including ST1901 (38%, 308/813), ST9363 (11%, 87/813), ST7363 (5%, 40/813), ST1580 (4%, 32/813), and ST1584 (3%, 27/813). Isolates belonging to the ST1901 (71%, 235/332; P < 0.0001) and ST1580 (10%, 30/332; P < 0.0001) groups were significantly associated with CFMem; however, only those from the ST1901 were significantly associated with CROem (75%, 75/104; P < 0.0001). Furthermore, isolates were assigned to 198 unique N. gonorrhoeaemulti-antigen sequencing typing (NG-MAST) STs, which differentiated many of the broader MLST ST groups (MLST STs differing by 1 allele). For instance, ST1407 (18%, 148/813), the largest group of NG-MAST STs, was observed among isolates with MLST STs 1901, 10312, 9365, and 7360. Isolates with NG-MAST ST3158 were detected only among MLST ST1901 strains, whereas NG-MAST 3935 was only detected among MLST STs 9363 and 11422 strains. In terms of antimicrobial susceptibility, isolates belonging to the NG-MAST ST1407 (41%, 137/332; P < 0.0001) and ST1580 (9%, 30/332; P < 0.0001) groups were significantly associated with CFMem; however, there were no clear significant associations observed between this ST or others with respect to CROem.

Phylogenomic analysis of circulating lineages with elevated cephalosporin MICs in the United States

After detection and removal of putative recombinant sites using Gubbins, the number of polymorphic sites estimated to be present in the non-recombinant part of the whole genome alignment was 25,140 nucleotides (nts)42. The overall recombination to mutation ratio (r/m) was 2.3, calculated as the ratio of base substitutions predicted within the predicted areas of recombination to those occurring through point mutations, and is similar to other previously reported studies26,43,44. The overall percentage of bases under clonal frame was approximately 71%. Fastbaps partitioned the maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny into 15 clades (A–O, Fig. 1). In total there were seven clades that contained at least two GISP isolates with elevated cefixime and/or ceftriaxone MICs including clades A through G. Both the reference strain FA19 and international MLST ST1903 strains possessing the mosaic penA-60 allele (strains A7846, A7536, FC428, FC460, 47707) appeared in separate lineages as distant outgroups45,46. Reference strains WHO-X and WHO-Z clustered with several GISP isolates in Clade D, but were distantly related45. The reference strain WHO-Y clustered with several GISP isolates with elevated cephalosporin MICs in Clade A. A summary of elevated MIC frequency, MLST STs, and intra-clade SNP distances observed in major clades of interest is presented in Table 1.

MSW men that have sex with women, MSM men that have sex with men, MSMW men that have sex with men and women, HHS Health and Human Services region, MIC minimum inhibitory concentration with respect to azithromycin (AZM), ciprofloxacin (CIP), penicillin (PEN), tetracycline (TET), cefixime (CFM), and ceftriaxone (CRO). Highlighted clades contain isolates where we identified the majority of elevated cephalosporin MICs. The tree also includes several reference genomes: FA19 (root, ǂ), international MLST ST1903 strains possessing the mosaic penA-60 allele (*) including strains from Japan (FC428, FC460) and Canada (47707); WHO reference strains WHO-X (H041, Japan) and WHO-Z (A8806, Australia) marked by (ɤ); and WHO-Y (F89, France) marked by (⁂). A summary of antimicrobial susceptibility to each respective antibiotic is shown with colors: susceptible (light orange), elevated MIC range (teal), or high-level MICs (dark green). Alleles for penA are colored based on their amino acid sequence homology to penA-34 (≥98% is a derivative allele; teal), differing mosaic penA allele (dark green), or absence of a mosaic penA allele.

Clade A (n = 278), the largest clade observed in the dataset, was comprised of a diverse collection of isolates spanning several Health and Human Services (HHS) regions (Fig. 1). This clade includes 84 isolates that were first reported by Grad et al.26 as the “cefRS cluster 1” in addition to many others collected by GISP between 2006 and 2017. Clade A was represented predominately by MLST ST1901 (87%, 242/278; P < 0.0001) and NG-MAST ST1407 (53%, 148/278; P < 0.0001), and displayed significant associations with CFMem (78%, 259/332; P < 0.0001) with most isolates possessing CFM MICs of 0.25 µg/mL (n = 246). This clade also contained the bulk of CROem isolates in the dataset (61%; 63/104; P < 0.0001) with most possessing CRO MICs of 0.125 µg/mL (n = 60). Isolates in this clade were characterized by the presence of a variety of mutations in loci commonly associated with elevated cephalosporin MIC, such as the presence of an adenine [A] deletion in the mtrR promoter in combination with the H105Y mutation in the mtrR coding region (CFMem: 75%, 250/332; CROem: 58%, 60/104; P < 0.0001). The majority of CFMem isolates possessed a mosaic penA-34 allele containing the key amino acid mutations I312M, V316T, N512Y, and G545S (77%, 254/332; P < 0.0001), although two isolates possessed a mosaic penA-72 (penA-34 + P551 mutation)47. The penA-34 (58%, 60/104; P < 0.0001) and penA-72 allele (n = 1) were also observed in CROem isolates. In addition, most isolates with elevated cephalosporin MICs in this clade also possessed the L421P mutation in PonA (94%, 260/278; P < 0.0001), which overall was significantly associated with CFMem (89%, 297/332; P < 0.0001) and CROem (99%, 103/104; P < 0.0001). We detected double mutations at amino acid residues Gly-120 and Ala-121 of PorB in the majority of the Clade A isolates with elevated cephalosporin MICs (256/278; P < 0.001), which was also significantly associated with CFMem (85%, 283/332; P < 0.001) and CROem (95%, 99/104; P < 0.0001).

A separate lineage of MLST ST1901 isolates was also observed (Clade B, n = 64, years 2005–2017) sharing a common ancestor with those in Clade A, but differed considerably in the diversity of NG-MAST STs and overall SNPs (average difference of >350 SNPs) (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Only eight isolates were detected with either CFMem or CROem, and with the exception of two isolates all possessed a mosaic penA-10 allele, which shares 98% homology to penA-34, but differs at the C-terminal end (amino acids 549–582)48. All CFMem or CROem isolates possessed an adenine [A] deletion in the mtrR promoter, MtrR H105Y mutation, the PonA L421P mutation, and six of the eight possessed the PorB G120K/A121D mutations.

Clade C (n = 151) contained a sub-lineage of 30 CFMem isolates (MLST ST1580; NG-MAST STs 5895 and 9604) from years 2009 to 2012, which were all susceptible to ceftriaxone26. These isolates were characterized by the presence of a G45D mutation in the MtrR coding region and a mosaic penA-34 allele (n = 32). All isolates in this clade possessed both a WT ponA and porB gene. Outside of Clade C and the aforementioned clades, there were 27 CFMem isolates and 28 CROem isolates that appeared sporadically throughout the phylogenetic tree. These isolates were collected from multiple HHS regions and years (2009–2017), were represented by several STs, and varied in co-occurring mutations across various antimicrobial AMR loci. A closer examination of 14 identified isolates with combined elevated cefixime and ceftriaxone MICs indicated that 7 of the 14 possessed a A-deletion in the MtrR promoter, and 11 possessed a least one or a combination of mutations in the MtrR coding region including the A39T (n = 1), G45D (n = 7), and H105Y (n = 2) mutations. In addition, we also detected six unique PBP2 patterns including those that encode a mosaic penA (10, 27, and 34) and non-mosaic penA alleles (12, 13, and 68). All 14 isolates possessed a WT PBP1, and nine possessed the G120K/A121D mutations in PorB.

Recently, it was shown in clinical gonococcal isolates without mosaic penA alleles that mutations in the RNA polymerase genes (i.e., rpoB and rpoD) can independently give rise to elevated cephalosporin MICs49. Accordingly, we examined our dataset and identified 32 isolates (2009–2017) distributed throughout the phylogeny with elevated cephalosporin MICs (ceftriaxone MICs ≥0.125, cefixime MICs ≥0.25 µg/mL) that could not be explained by mutations in PBP2. A closer look at the WGS data revealed several previously reported mutations in the RNA polymerase genes rpoB and rpoD (Supplementary Data 1). Fourteen of the isolates possessed a WT rpoB gene, while 17 possessed the H553N mutation (Clade B, n = 1; Clade D, n = 3; Clade F, n = 5; Clade G, n = 1; Clade H, n = 1; Clade J, n = 5). We did not detect any additional isolates, aside from three previously reported strains included in this study’s dataset, with either the rpoB R201H mutation (Clade E, n = 1), deletion of amino acids 92–95 (Clade D, n = 1), or the E98K mutation in the rpoD gene (Clade D, n = 1)49. A summary of all unique mutations in the rpoB and rpoD genes is provided in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Figs 1 and 2.

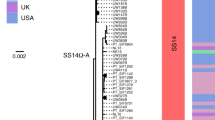

Tracing the global emergence of Clade A-B isolates using timed-scaled phylogenetic analysis

To generate a more detailed understanding of the geographic origin and spread of isolates with elevated cephalosporin MICs (ESCem), we performed timed phylogenetic analyses using BEAST, specifically focusing on the Clade A-B isolates (n = 340, 278 with the MLST ST1901 designation) where the majority of ESCem was detected. We included an additional 465 international isolates (MLST ST1901), which along with Clade A-B isolates fall within the cgMLST cgc400 core genome group no. 3 (Supplementary Data 1 and 2)50. From the BEAST analysis, we estimated the substitution rate for the non-recombinant region of the genome collection at 1.8215 × 10–6 substitutions per site per year, (95% highest posterior density (HPD) ranging from 1.62323 × 10–6 to 2.069 × 10–6) and 2.3638 × 10–6 substitutions per site per year (95% HPD; 2.035 × 10–6–3.1145 × 10–6) for the strict (Fig. 2/Supplementary Table 1) and relaxed (Supplementary Fig. 3/Supplementary Table 2) clock model). The substitution rates are similar to previous estimates from other population-level studies that included N. gonorrhoeae strains from a single or similar STs26,51,52. For both models, we estimated credibility intervals (CIs) for the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) in selected internal nodes (Supplementary Table 3). We estimated the tMCRA for the Clade A-B isolates (n = 805) to be around the early twentieth century. The clade diverged into two sub-lineages around the 1920s (1925, CI: 1913–1951), which we denoted as Clade AB1 and Clade AB2. The larger Clade AB1 contained the majority of the US isolates (n = 594) along with international isolates (n = 147), and were estimated to have emerged from a common ancestor that existed in 1944 (95% CI: 1935–1953) (Supplementary Table 3). The smaller Clade AB2 strains are largely susceptible (n = 64), but contained a small group of ESCem isolates from North America, Asia, and Europe with mosaic penA-71,72, or 75 alleles, all of which appear to have emerged rather sometime around the early 2000s. In addition, while both lineages possess a genomic background with multiple resistances to penicillin, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin, the majority of ESCem, particularly to cefixime, were found in Clade AB1. Interestingly, it is in Clade AB1 where we observed the majority of mosaic penA alleles; notably penA-34 and similar derivatives.

Clade AB1 and Clade AB2 represent the divergent sub-lineages that we identified in the phylogeny. The oldest sequenced isolate is from the Philippines collected in 1992. The phylogeny includes epidemiological details and antimicrobial susceptibility. Sex of sex partners are colored [MSW men that have sex with women (red), MSM men that have sex with men (light orange), MSMW men that have sex with men and women (light blue)]. Antimicrobial susceptibility is based on minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to each respective antibiotic and is shown with colors: susceptible (light orange), elevated MIC range (teal), or high-level MICs (dark green). Alleles for penA are colored based on their amino acid sequence homology to penA-34 (≥98% is a derivative allele; teal), differing mosaic penA allele (dark green), or absence of a mosaic penA allele. Amino acid mutations in PBP2 associated with elevated cephalosporin MICs are shown at the top of figure. The bottom scale bar represents the time to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of the internal node of the phylogenetic tree. Numbers highlighted in red are the ancestral nodes of the time-scaled phylogenetic tree and represent estimated years and credibility intervals based on tMRCA: 1) Root; 1818 [1781 - 1865], 2) 1925 [1913 - 1951], 3) 1944 [1935 - 1953], 4) 1952 [1942 - 1964], 5) 1970 [1964 - 1977], 6) 1972 [1966 -1979], 7) 1985 [1980 - 1990], 8) 1987 [1983 - 1992], 9) 1990 [1986 - 1994].

Discussion

In light of several reports that have examined the global rise in azithromycin MICs, the importance of monitoring resistance to ESCs, particularly ceftriaxone—the last universally effective drug, cannot be overstated. Recently, in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States, azithromycin was removed as a co-administered agent from national treatment guidelines in favor of ceftriaxone monotherapy9,53,54,55,56,57,58. We conducted a large study on gonococcal isolates collected by sentinel surveillance in the United States, with a focus on reduced susceptibility to ESCs. Data for this study were collected over a 13-year period from geographically diverse STD clinics and represents a reasonable approximation of circulating gonococcal strains across US regions over time. Our data are consistent with several previous and recent studies which have indicated that N. gonorrhoeae with elevated cephalosporin MICs has emerged in the United States through several distinct lineages via repeated importation from other countries, clonal expansion, extensive recombination events, or a combination of these factors26,28,29,59,60. We identified five distinct lineages of N. gonorrhoeae with elevated cephalosporin MICs in the United States that could primarily be attributed to mosaic penA-34 and derivative alleles (Fig. 1).

A smaller clade of CFMem isolates in the MLST ST1580 lineage, first described as “cefRS cluster 2” by Grad et al.26, but referred to as Clade E in this study, showed evidence of persistence as late as 2012, but appears to be no longer circulating. Why this lineage is no longer spreading is unclear. However, it is possible that a lack of biological fitness, susceptibility to other antimicrobials (e.g., ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone), successful outbreak control, or a combination of these and other public health interventions may explain a lack of further dissemination.

We found evidence of two emerging CFMem clades with additional resistances to penicillin, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin7,14,48,61. These lineages contained isolates with the MLST ST14283 and ST7363 (Clade D, n = 6, 2012–2017) and MLST ST1600 and ST1579 (Clade G, n = 6, 2014–2017) designation in addition to mosaic penA alleles (penA-10 and penA-27, respectively). Notably, the MLST ST7363 lineage among others (e.g., ST1901) have been attributed to the historical emergence and spread of gonococcal strains with mosaic penA-10 and reduced susceptibility to cephalosporins, especially cefixime, and other oral ESCs, beginning around the mid-1990s in metropolitan Japanese cities7,14,24. The ability to identify these clades at fine resolution highlights the utility of WGS-based phylogenomics when combined with epidemiologic and phenotypic data in unraveling various strain populations. Future studies that incorporate data from this study will reveal if these lineages continue to persist and how they compare to known strains with reduced susceptibility to cephalosporins.

Perhaps our most significant findings came from analysis of Clades A-B, the largest lineage containing ESCem isolates in our dataset. First described as “cefRS cluster 1” by Grad et al.26, this lineage showed evidence of continuing persistence across the United States, particularly on the Westcoast, and was predominantly within MSM networks, with a limited number of introductions into heterosexual networks26. Based on our phylogenomic analysis of genetically similar MLST ST1901 isolates from 1992 to 2017, we provide additional evidence that these strains share a common ancestor, and are likely descended from the clonal spread of strains originating from East Asia7,10,14,24. We estimate that a common ancestor of the Clade A-B ST1901 lineage may have emerged around the early twentieth century (1925, CI: 1913–1951), and spread into two deeply split lineages. Considering historical trends in global antibiotic usage, our data support other studies that propose a successive acquisition of AMR determinants in these ST1901 strains over time. In fact, the vast majority of all ST1901 strains in our dataset possessed a genomic background associated with resistance to penicillin (widely used between mid-1940s–1970s), tetracycline (1940s–1960s; mediated by rpsJ V57M mutations and tetM plasmid), and fluoroquinolones (widely used in the 1980s; mediated by gyraA S91F, D95A, D95G; parC S87R mutations)10. Evidence appears to support the hypothesis that the ST1901 strains acquired the penicillin, tetracycline, and the ciprofloxacin resistance phenotype first, before acquiring reduced susceptibility to ESCs20,21,22.

With regard to Clade AB1 strains with mosaic penA-34 and derivative alleles, we estimate that their most recent common ancestor emerged around the mid-1980s (1985; CI: 1980–1990, Fig. 2/Node # 7). This includes the oldest isolate in our dataset (34789_MU_NG5) from 1992, which harbors a penA-10 allele. It has been proposed that penA-10 originated (April 1986–August 1995) from a recombination event in a penA-5 background, and that the origin of penA-34 is the result of an additional recombination event (May 1990–July 1999) from a penA-1 donor strain into a penA-10 background62. When examining several of the Clade AB1 lineages with mosaic penA-34 or derivatives on an individual basis, most appear to have emerged around the 1990s (1990; CI: 1986–1994, Fig. 2/Node #9). These results largely recapitulate those of the recent Osnes et al.63 study, albeit with slight differences in timing (hereafter we report our tMRCAs and CIs), which suggested two waves of expansion of ST1901 strains out of East Asia: an initial Wave 1 [1970s (1964–1979)], followed by reintroductions in East Asia from Europe and North America, and finally a larger global dispersal of the dominant ST1901 lineage between the 1980s and 1990s [Wave 2; 1987(1983–1992)].

Our current study has several limitations. Notably, samples from the GISP sentinel surveillance system include those from only male patients with symptomatic urethritis at select STD clinics across the United States. Therefore, bias is introduced by not only the populations that visit the clinics but also the exclusion of women who are often asymptomatic, asymptomatic men, extragenital sites of infection, and thus GISP may not fully represent all gonorrhea in the United States. Second, the final sequenced dataset contains most, but not all isolates with elevated cefixime or ceftriaxone MICs. Considering these limitations, findings from our study suggest that patterns of AMR may be generalizable for the populations collected from in the United States between the years 2005 and 2017.

Overall, our analyses support previous studies that have suggested reduced susceptibility to ESCs has emerged and spread independently between and within multiple sexual networks in the United States. We show that the acquisition of cephalosporin-associated AMR has occurred primarily through extensive recombination events, limited de novo mutations, and possible importation from other countries. Given that ceftriaxone is the cornerstone of current therapies and there are few alternatives, it is important to continue carefully monitoring cephalosporin MICs, facilitate programs aimed at increased screening and reducing N. gonorrhoeae transmission, particularly in the populations most affected. Finally, our study underscores the continuing need for drugs with novel mechanisms, and diagnostic point-of-care tests to rapidly screen gonococcal infections to identify susceptibility and provide personalized patient care.

Methods

Isolate selection

Antimicrobial susceptibilities were determined using the agar dilution method, with some further analyzed by ETEST for end-pointing (bioMerieux, France)29. Because the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute has not established resistance breakpoints for cefixime or ceftriaxone and only state susceptibility (≤0.25 µg/mL for both antimicrobials), we defined elevated MICs as follows: elevated cefixime (CFMem; MIC ≥0.25 µg/mL), ceftriaxone (CROem; MIC ≥0.125 µg/mL), and isolates with elevated MICs to both ESCs (ESCem). International isolates with high-level cefixime and/or ceftriaxone MICs were included as references (WGS data were downloaded manually or using SRA toolkit v2.8; http://ncbi.github.io/sra-tools/). Strains from Japan (FC428, FC460) and Australia (A7846, A7536) are available under BioProject PRJNA416507, and a strain from Canada (47707) is available under BioProject PRJNA41504732,45. Three strains available in the World Health Organization [WHO] reference panel as WHO-X (H041, Japan),WHO-Y (F89, France), and WHO-Z (A8806, Australia) were also included for comparison64. A summary of elevated MIC frequency, MLST STs, and intra-clade SNP distances observed in major clades of interest is presented in Table 1.

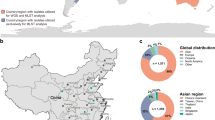

Between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2017, 72,807 urethral gonococcal isolates were collected from symptomatic men through GISP. Overall, 434 GISP isolates were identified with elevated MICs to ESCs, including 293 isolates (68%) that exhibited elevated cefixime MICs, 48 (11%) isolates that exhibited elevated ceftriaxone MICs, and 93 (21%) isolates that exhibited elevated MICs to both ESCs. A convenience sampling of the 72,807 resulted in a total of only 813 isolates being sequenced. Of the 434 GISP isolates with elevated MICs to ESCs, 355 were included in the sequenced isolates with 251 isolates having only elevated cefixime MICs, 23 isolates having only elevated ceftriaxone MICs and 81 isolates having elevated MICs to cefixime and ceftriaxone. Collectively, this resulted in 332 isolates (41%) with elevated cefixime MICs and 104 isolates (13%) with elevated ceftriaxone MICs being included in the dataset. All gonococcal isolates with elevated cephalosporin MICs were matched as closely as possible to susceptible isolates with sequencing data, based on similar region and year. Isolates that were not sequenced by CDC or its partners were missing at random, and unavailable in freezer inventories for unknown reasons. Furthermore, isolates were distributed throughout various US Department of HHS regions, although the majority were overrepresented from the western regions in overall accordance with GISP design (54%, HHS:8, n = 11; HHS:9, n = 372; HHS:10, n = 54) and midwestern region (19%, HHS:5, n = 126; HHS:7, n = 31)29. The GISP isolates in the sequenced dataset were collected from male patients with varying sex of sex partners, including those with female only partners (MSW, 42%), male only partners (MSM, 49%), both male and female partners (MSMW, 8%), and unknown (1%). Additional details on the full dataset are provided in Supplementary Data 1 and a Microreact project: https://microreact.org/project/ESC2005-2017JT65.

Whole genome sequencing and bioinformatics analyses

All 813 N. gonorrhoeae isolates from GISP were sequenced on an Illumina Miseq sequencer at the CDC core sequencing facility (Atlanta, GA) or at either the Maryland, Tennessee, Texas, or Washington State Public Health Laboratories, which are all part of the Antibiotic Resistance Laboratory Network regional laboratories. All sequencing reads were initially screened using Kraken v0.10.5, to identify reads assigned to bacterial strains other than N. gonorrhoeae. Samples with more than 10% of raw reads assigned to Neisseria meningitidis were considered contaminated. In addition, reads were trimmed using CutAdapt v1.8.3 to remove adaptor sequences and bases using a minimum quality cutoff of <Q30 and a minimum length cutoff of 19. Illumina reads were de novo assembled using Spades v3.9.0 under default parameters66. For phylogenetic analysis, a full-length whole genome alignment was generated using snippy v4.3.8 (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy) with FA19 (GenBank accession CP012026.1 set as the reference)67. This full-length whole genome alignment was used as an input to Gubbins v2.3.1 for identifying and filtering regions of homologous recombination. The resulting alignment, containing only the polymorphisms present in the non-recombinant regions, was used as input for RAxML v8.2.9 under the GTR + GAMMA model of nucleotide substitution with a majority-rule consensus convergence criterion, to reconstruct an ascertainment bias corrected (Stamatakis method) ML phylogeny42,68. Analysis of population structure within the ML phylogeny was conducted using Fastbaps v1.0 to identify major clusters under default parameters69. Pairwise SNP distances between isolate genomes were calculated using Snp-dists v0.4 (https://github.com/tseemann/snp-dists) using the recombination removed alignment from Gubbins as input. Determination of AMR genotypes was determined using a combination of several tools including an in-house AMR profiler or tblast alignment of contigs against a reference genes extracted from FA19 in Geneious Prime v2019.2.3 (https://www.geneious.com/prime/). MLST and NG-MAST schemes were determined by StringMLST v0.6.3 and NGMASTER v0.5.5, respectively70,71. WGS data were also screened against the NG-STAR v2.0 database using pyngSTar (https://github.com/leosanbu/pyngSTar)72.

To generate a more detailed understanding of potential introductions and geographic spread of isolates with elevated cephalosporin MICs and mosaic penA alleles, we performed a timed-scaled phylogenetic analysis using BEAST (Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis Sampling Trees) v1.8.4. In total we examined 805 gonococcal genomes collected over multiple years ranging from 1992 to 2017. We used TempEst v1.5.3 to determine if there was a sufficient temporal signal for molecular clock analysis and estimated the root-to-tip correlation was 0.5258 (R2 = 0.2765; Supplementary Fig. 4)73. The 805 isolates consisted of 340 GISP isolates identified in Clade A-B of this study, and 465 international isolates (MLST ST1901) obtained from PubMLST that were recently placed within the cgMLST cgc400 core genome group no. 350. We confirmed that these isolates clustered together by applying fastbaps to the original ML phylogeny containing the 813 GISP isolates but with the additional 465 international isolates, as not all MLST ST1901 strains in PubMLST share a similar genomic background (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Initially, we used ABACAS2 to create a concatenated and ordered “pseudochromosome” of isolate 34789_MU_NG5 (Philippines, 1992; accession SRR969380) against the WHO-Y reference genome (F89, MLST ST1901; accession LT592161)74. We removed all the Ns that ABACAS2 adds to the overlapping regions where any two contigs are joined, and used this updated pseudochromosome as the reference input for snippy v4.3.8 (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy) to generate a whole genome alignment of the abovementioned MLST ST1901 strains. Following the identification and masking of recombinant SNPs in Gubbins, the resulting alignment was used as the input for BEAST v1.8.475. An ascertainment bias correction step was included by providing the count of the monomorphic sites for each nucleotide in the reference within the BEAST input XML file generated in BEAUti v1.8.475. A HKY (Hasegawa, Kishino, and Yan) substitution model provided by ModelTest-NG v0.1.6, a coalescent model with constant population size, and both strict and uncorrelated relaxed clock models with an exponential distribution as the prior for the clock rate were used for the BEAST analysis76. Eight independent chains of 100 million steps were run for clock model, with samples taken every 1000 steps to ensure good mixing. The results were compared using Tracer v1.7.1 to confirm convergence, and the maximum clade credibility trees were generated using Tree Annotator, which are both provided with the BEAST v1.8.4 package.

Statistical analyses and data visualization

Fisher’s exact or χ2 test were used to determine the association between mutational patterns, STs, sex of sex partner, or clades with respect to elevated MICs respective of each antibiotic. P values and 95% confidence intervals were used to determine statistical significance. A Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple tests77. Phylogenetic trees were initially visualized using iToL v6, then redrawn using phandango v1.3.0 (https://github.com/jameshadfield/phandango) and Microreact v5.93.065,78,79. The ggtree v2.5.1 R package (https://github.com/YuLab-SMU/ggtree) was used to visualize all BEAST generated time-scaled phylogenies80.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw sequencing data and genome assemblies for isolates in this study are included as either BioProject (NCBI Sequence Read Archive or European Nucleotide Archive accession codes, or PubMLST identification numbers) (Supplementary Data 1 and 2). Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available in text and Supplementary information files.

References

CDC. Antibiotic-resistant germs: new threats. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest-threats.html. (2020). Accessed April 8, 2020.

Rowley J., et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull. World Health Organ Type Res. 97, 548–562P (2019).

CDC. 2017 Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/default.htm. (2018) Accessed October 19, 2018.

Unemo, M. & Shafer, W. M. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st Century: past, evolution, and future. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 27, 587–613 (2014).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 61, 590–594 (2012).

Unemo, M. et al. High-level cefixime- and ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in France: novel penA mosaic allele in a successful international clone causes treatment failure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 1273–1280 (2012).

Shimuta, K. et al. Emergence and evolution of internationally disseminated cephalosporin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae clones from 1995 to 2005 in Japan. BMC Infect. Dis. 15, 378 (2015).

Anon. Gonococcal infections – 2015 STD treatment guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/gonorrhea.htm. (2019) Accessed April 17, 2019.

Cyr, S. S. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 69 (2020). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6950a6.htm. Accessed February 4, 2021.

Unemo, M., del Rio, C., & Shafer, W. M. Antimicrobial resistance expressed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a major global public health problem in the 21st century. Microbiol. Spectr. 4, 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4920088/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

Hill, S. A., Masters, T. L., & Wachter, J. Gonorrhea—an evolving disease of the new millennium. Microb. Cell 3, 371–389 (2016).

Igawa, G., et al. Neisseria cinerea with high ceftriaxone MIC is a source of ceftriaxone and cefixime resistance-mediating penA sequences in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62, e02069-17 (2018).

Xiu, L. et al. Emergence of ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains harbouring a novel mosaic penA gene in China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 907–910 (2020).

Barry, P. M. & Klausner, J. D. The use of cephalosporins for gonorrhea: the impending problem of resistance. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 10, 555–577 (2009).

Zapun, A., Morlot, C., & Taha, M.-K. Resistance to β-lactams in Neisseria ssp due to chromosomally encoded penicillin-binding proteins. Antibiotics 5, 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5187516/. Accessed September 19, 2018.

Tomberg, J. et al. Alanine-501 mutations in penicillin-binding protein 2 from Neisseria gonorrhoeae: structure, mechanism, and effects on cephalosporin resistance and biological fitness. Biochemistry 56, 1140–1150 (2017).

Spratt, B. G. Hybrid penicillin-binding proteins in penicillin-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Nature 332, 173–176 (1988).

Bowler, L. D., Zhang, Q. Y., Riou, J. Y. & Spratt, B. G. Interspecies recombination between the penA genes of Neisseria meningitidis and commensal Neisseria species during the emergence of penicillin resistance in N. meningitidis: natural events and laboratory simulation. J. Bacteriol. 176, 333–337 (1994).

Ameyama, S. et al. Mosaic-like structure of penicillin-binding protein 2 gene (penA) in clinical isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 3744–3749 (2002).

Akasaka, S. et al. Emergence of cephem- and aztreonam-high-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae that does not produce β-lactamase. J. Infect. Chemother. 7, 49–50 (2001).

Muratani, T. et al. Outbreak of cefozopran (penicillin, oral cephems, and aztreonam)-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 3603–3606 (2001).

Ito, M. et al. Emergence and spread of Neisseria gonorrhoeae clinical isolates harboring mosaic-like structure of penicillin-binding protein 2 in central Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 137–143 (2005).

Tomberg, J., Unemo, M., Davies, C. & Nicholas, R. A. Molecular and structural analysis of mosaic variants of penicillin-binding protein 2 conferring decreased susceptibility to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: role of epistatic mutations. Biochemistry 49, 8062–8070 (2010).

Ohnishi, M. et al. Spread of a chromosomal cefixime-resistant penA gene among different Neisseria gonorrhoeae lineages. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 1060–1067 (2010).

Gose, S. et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and extended-spectrum cephalosporins in California: surveillance and molecular detection of mosaic penA. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 570 (2013).

Grad, Y. H. et al. Genomic epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime in the USA: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 220–226 (2014).

Stefanelli, P., & Carannante, A. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a new challenge. In: Cristaudo, A., Giuliani, M., eds. Sexually Transmitted Infections: Advances in Understanding and Management. 363–374 (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02200-6_19. Accessed April 11, 2021.

Grad, Y. H. et al. Genomic epidemiology of gonococcal resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones in the United States, 2000–2013. J. Infect. Dis. 214, 1579–1587 (2016).

Thomas, J. C., et al. Evidence of recent genomic evolution in gonococcal strains with decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins or azithromycin in the United States, 2014-2016. J. Infect. Dis. https://academic.oup.com/jid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/infdis/jiz079/5351606. Accessed April 17, 2019.

Wong, L. K., et al. Targeting the penA Mosaic XXXIV type for prediction of extended-spectrum-cephalosporin susceptibility in clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, 2017. https://aac.asm.org/content/61/11/e01339-17. Accessed April 9, 2020.

Ohnishi, M. et al. Ceftriaxone-resistantNeisseria gonorrhoeae, Japan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 148–149 (2011).

Nakayama, S. et al. New ceftriaxone- and multidrug-resistantNeisseria gonorrhoeae strain with a novel mosaic penA gene isolated in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 4339–4341 (2016).

Vincent, L. R., et al. In vivo-selected compensatory mutations restore the fitness cost of mosaic penA alleles that confer ceftriaxone resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. mBio 9, e01905–e01917 (2018).

Whiley, D. M., Limnios, E. A., Ray, S., Sloots, T. P. & Tapsall, J. W. Diversity of penA alterations and subtypes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains from Sydney, Australia, that are less susceptible to ceftriaxone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 3111–3116 (2007).

Liao, M., Gu, W.-M., Yang, Y. & Dillon, J.-A. R. Analysis of mutations in multiple loci of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates reveals effects of PIB, PBP2 and MtrR on reduced susceptibility to ceftriaxone. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66, 1016–1023 (2011).

Thakur, S. D., Starnino, S., Horsman, G. B., Levett, P. N. & Dillon, J. R. Unique combined penA/mtrR/porB mutations and NG-MAST strain types associated with ceftriaxone and cefixime MIC increases in a ‘susceptible’ Neisseria gonorrhoeae population. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 1510–1516 (2014).

Eyre, D. W. et al. WGS to predict antibiotic MICs for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 1937–1947 (2017).

Abrams, A. J. et al. A case of decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone in Neisseria Gonorrhoeae in the absence of a mosaic penicillin-binding protein 2 (pena) allele. Sex. Transm. Dis. 44, 492–494 (2017).

Nandi, S., Swanson, S., Tomberg, J. & Nicholas, R. A. Diffusion of antibiotics through the PilQ secretin in Neisseria gonorrhoeae occurs through the immature, sodium dodecyl sulfate-labile form. J. Bacteriol. 197, 1308–1321 (2015).

Anon. GISP—Gonorrhea—STD information from CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gisp/default.htm. Accessed September 18, 2018.

Anon. CDC—GISP Profiles – 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/gisp2016/default.htm. (2019) Accessed April 17, 2019.

Croucher, N. J. et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e15 (2015).

Ezewudo, M. N. et al. Population structure of Neisseria gonorrhoeae based on whole genome data and its relationship with antibiotic resistance. PeerJ 3, e806 (2015).

Vigué, L., & Eyre-Walker, A. The comparative population genetics of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. PeerJ 7, 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6599670/. Accessed June 24, 2020.

Lahra, M. M. et al. Cooperative recognition of internationally disseminated ceftriaxone-resistantNeisseria gonorrhoeae strain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 735–740 (2018).

Berenger, B. M., et al. Genetic characterization and enhanced surveillance of ceftriaxone-resistantNeisseria gonorrhoeae strain, Alberta, Canada, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 25, 1660–1667 (2019).

Lee, H., et al. Emergence and spread of cephalosporin-resistantNeisseria gonorrhoeae with mosaic penA alleles, South Korea, 2012–2017—Volume 25, Number 3—March 2019—Emerging Infectious Diseases journal—CDC. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/25/3/18-1503_article. Accessed December 13, 2019.

Shimuta, K., et al. Antimicrobial resistance and molecular typing of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Kyoto and Osaka, Japan, 2010 to 2012: intensified surveillance after identification of the first strain (H041) with high-level ceftriaxone resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 5225–5232 (2013).

Palace, S. G., et al. RNA polymerase mutations cause cephalosporin resistance in clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates. eLife 9, e51407 (2020).

Harrison, O. B., et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae population genomics: use of the gonococcal core genome to improve surveillance of antimicrobial resistance. J. Infect. Dis. https://academic.oup.com/jid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/infdis/jiaa002/5804212. Accessed June 25, 2020.

Didelot, X., et al. Genomic analysis and comparison of two gonorrhea outbreaks. mBio 7, 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4937209/. Accessed April 19, 2020.

De Silva, D. et al. Whole-genome sequencing to determine Neisseria gonorrhoeae transmission: an observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 1295–1303 (2016).

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH). British Association for Sexual Health and HIV national guideline for the management of infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae (2019). https://www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1208/gc-2019.pdf. (2019) Accessed April 17, 2019.

Whiley, D. M. et al. Azithromycin-resistantNeisseria gonorrhoeae spreading amongst men who have sex with men (MSM) and heterosexuals in New South Wales, Australia, 2017. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 1242–1246 (2018).

Xue, J., Ni, C., Zhou, H., Zhang, C. & van der Veen, S. Occurrence of high-level azithromycin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 3404–3405 (2015).

Allen, V. G., Seah, C., Martin, I., & Melano, R. G. Azithromycin resistance is co-evolving with reduced susceptibility to cephalosporins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Ontario, Canada. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 2528–2534 (2014).

Unemo, M. & Workowski, K. Dual antimicrobial therapy for gonorrhoea: what is the role of azithromycin? Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 486–488 (2018).

Fifer, H. et al. Sustained transmission of high-level azithromycin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in England: an observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 573–581 (2018).

Sánchez-Busó, L. et al. The impact of antimicrobials on gonococcal evolution. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1941–1950 (2019).

Town, K., et al. Early release—genomic and phenotypic variability in Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility, England—Volume 26, Number 3—March 2020—Emerging Infectious Diseases journal—CDC. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/3/19-0732_article. Accessed February 20, 2020.

Yang, Y. et al. NG-STAR genotypes are associated with MDR in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates collected in 2017 in Shanghai. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 566–570 (2020).

Yahara, K. et al. Emergence and evolution of antimicrobial resistance genes and mutations in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Genome Med. 13, 1–12 (2021).

Osnes, M. N. et al. Antibiotic treatment regimes as a driver of the global population dynamics of a major gonorrhea lineage. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 1249–1261 (2020).

Unemo, M. et al. The novel 2016 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae reference strains for global quality assurance of laboratory investigations: phenotypic, genetic and reference genome characterization. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71, 3096–3108 (2016).

Argimón, S. et al. Microreact: visualizing and sharing data for genomic epidemiology and phylogeography. Micro. Genomics 2, e000093 (2016).

Bankevich, A. et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput Biol. 19, 455–477 (2012).

Abrams, A. J., Trees, D. L., & Nicholas, R. A. Complete genome sequences of three Neisseria gonorrhoeae laboratory reference strains, determined using PacBio single-molecule real-time technology. Genome Announc. 3, 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4566190/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 (2006).

Tonkin-Hill, G., Lees, J. A., Bentley, S. D., Frost, S. D. W. & Corander, J. Fast hierarchical Bayesian analysis of population structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 5539–5549 (2019).

Gupta, A., Jordan, I. K. & Rishishwar, L. stringMLST: a fast k-mer based tool for multilocus sequence typing. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 33, 119–121 (2017).

Kwong J. C., et al. NGMASTER: in silico multi-antigen sequence typing for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Microb. Genomics 2, 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5320595/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

Demczuk, W. et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae sequence typing for antimicrobial resistance, a novel antimicrobial resistance multilocus typing scheme for tracking global dissemination of N. gonorrhoeae strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55, 1454–1468 (2017).

Rambaut, A., Lam, T. T., Max Carvalho, L., & Pybus, O. G. Exploring the temporal structure of heterochronous sequences using TempEst (formerly Path-O-Gen). Virus Evol. 2, 2016. https://academic.oup.com/ve/article/2/1/vew007/1753488. Accessed June 25, 2020.

Assefa, S., Keane, T. M., Otto, T. D., Newbold, C. & Berriman, M. ABACAS: algorithm-based automatic contiguation of assembled sequences. Bioinformatics 25, 1968–1969 (2009).

Drummond, A. J., Suchard, M. A., Xie, D. & Rambaut, A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1969–1973 (2012).

Darriba, D. et al. ModelTest-NG: a new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 291–294 (2020).

Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restor. Dent. Endod. 42, 152–155 (2017).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W256–W259 (2019).

Hadfield, J. et al. Phandango: an interactive viewer for bacterial population genomics. Bioinformatics 34, 292–293 (2018).

Yu, G. Using ggtree to visualize data on tree-like structures. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 69, e96 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) core sequencing facility (Atlanta, GA). We also thank the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance (GISP) and Strengthening the US Response to Resistant Gonorrhea (SURRG) for the contribution of additional isolate and epidemiologic data used in our analyses. We thank Alesia Harvey for assistance for verifying isolate epidemiologic and MIC data. This work was supported in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advanced Molecular Detection and Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria initiative. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

J. C. T., B. H. R., and E. N. K. designed the study. S. B. S. and K. S. provided GISP/SURRG isolates and associated epidemiological data. J. C. T., S. J. J., J. C. C., and M. W. S. performed bioinformatic analysis. J. C. T. performed statistical analyses. C. D. P. and the Antimicrobial Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae Working Group provided confirmatory antimicrobial susceptibility testing and information on minimum inhibitory concentrations. Members of the Antimicrobial Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae Working Group also conducted whole genome sequencing of isolates at their respective public health laboratories. J. C. T. wrote and prepared the first draft of the manuscript with contributions from S. J. J. and B. H. R., which was reviewed by all authors for revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, J.C., Joseph, S.J., Cartee, J.C. et al. Phylogenomic analysis reveals persistence of gonococcal strains with reduced-susceptibility to extended-spectrum cephalosporins and mosaic penA-34. Nat Commun 12, 3801 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24072-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24072-1

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.