Abstract

Allylic amines are versatile building blocks in organic synthesis and exist in bioactive compounds, but their synthesis via hydroaminoalkylation of alkynes with amines has been a formidable challenge. Here, we report a late transition metal Ni-catalyzed hydroaminoalkylation of alkynes with N-sulfonyl amines, providing a series of allylic amines in up to 94% yield. Double ligands of N-heterocyclic carbene (IPr) and tricyclohexylphosphine (PCy3) effectively promote the reaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

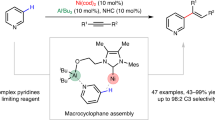

Allylic amines not only widely exist in a broad range of natural products and bioactive compounds, but also serve as versatile building blocks in organic synthesis1,2,3,4. The development of efficient and general methods for their synthesis has received much attention during the past several decades5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Among various reported methods, transition metal-catalyzed hydroaminoalkylation of π-unsaturated compounds, such as alkenes and alkynes represents one of the most straightforward and atom-economical synthetic routes24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. With using either early24,25,26 or late transition metals as catalysts27,28,29,30,31, a large number of hydroaminoalkylations of alkenes have been developed. However, in sharp contrast, analogous reactions of alkynes were faced with tremendous challenges (Fig. 1a), likely owing to difficult alkyne insertion and challenging protonolysis32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. A pioneering investigation was conducted in 1989 by Buchwald and co-workers, who successfully obtained the allylic amine product by aqueous work-up. Despite an efficient protonolysis, the regeneration of Zr catalyst cannot be realized in this protocol, leading to stoichiometric Zr-complex needed32. Since then, much effort has been devoted to improving the reaction33,34,35,36,37,38,39, while the development of a catalytic method has been an elusive challenge. Most recently, during our submission, Schafer group used a tetradentate bis(ureate) ligand and metal Zr to in situ form a bulky Zr catalyst, achieving a catalytic hydroaminoalkylation of alkynes for the first time (Fig. 1b)40,41. The bulky ligand proved critical to the reactivity, not only facilitating alkyne insertion, but also allowing the coordination of neutral amines to the metal center for subsequent easier protonolysis. Despite this big advance, the early transition metal Zr-catalyzed method still suffered from some undesired limitations such as unavoidable hydroamination side reaction in many cases, difficult-to-remove N-aryl protecting groups, and tricky regioselectivity under relatively harsh conditions. Therefore, the development of other efficient catalytic systems for hydroaminoalkylation of alkynes is still highly desirable. In this work, we use an inexpensive nickel as a catalyst to achieve a late transition metal-catalyzed hydroaminoalkylation of alkynes with N-sulfonyl amines, providing a series of allylic amines in up to 94% yield (Fig. 1c). The reaction features relatively mild conditions (80 °C), general substrate scope of both amines and alkynes and high regioselectivity.

a Pioneering investigation using stoichiometric Zr-complex (Buchwald). b Strategy I using early transition metal Zr and bulky tetradentate ligand (Schafer). c Strategy II using late transition metal Ni with dual ligands (this work). IPr = 1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-imidazole. Cy3P = tricyclohexylphosphine.

Results

Reaction optimization

In comparison with various hydroaminoalkylations of alkenes, the difficulty of hydroaminoalkylation of alkynes was ascribed to the following possible reasons: (1) strong basic and nucleophilic alkyl or aryl amines could coordinate to metal centers, resulting in either deactivation of transition metals or undesired side reactions such as hydroaminations; (2) weak acidity of N−H bonds cannot effectively undergo protonolysis of metallocycle intermediates. Thereby, the selection of proper N-protecting groups to increase the acidity of amines could be critical to the reaction efficiency, because more acidic amine would significantly reduce its coordination with metal centers and other side reactions such as hydroamination. However, to accommodate acidic N−H bonds, sensitive early transition metal complexes should be replaced by late transition metals such as Pd, Ru and Ni, because they could have better compatibility with protic substrates and solvents.

Following this hypothesis, we conducted an extensive survey on N-protecting groups, transition metals, ligands and other reaction parameters. Ultimately, triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl (TPS) was identified as the superior N-protecting group and Ni/IPr/PCy3 was identified as the optimal catalyst. With their combination, hydroaminoalkylation of alkyne 2a with N-TPS amine 1a smoothly proceeded under mild conditions (80 °C), providing the corresponding allylic amine 3a in nearly quantitative yield (Fig. 2, entry 1).

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.20 mmol), 2a (0.22 mmol), toluene (2.0 mL) under N2 for 1 h; yield was determined by 1H NMR using Cl2CHCHCl2 as the internal standard. IPrMe = 1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-4,5-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-imidazole. SIPr = 1,3-bis(2,6- diisopropylphenyl)imidazolidine. IMes = 1,3-dimesityl-2,3-dihydro-1H-imidazole. dppe = 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane.

Control experiments showed that the alteration of TPS resulted into significantly diminished yields (entries 2−8). For example, the replacement of isopropyl groups (TPS) by methyl groups (TMS) gave only 9% yield (entry 2). Common p-tolylsulfonyl (Ts) further decreased the yield to a trace amount (entry 3). The combination of NHC (IPr) and phosphine (PCy3) ligands also proved critical to the reaction (entries 9−17). The absence of IPr·HCl completely inhibited the reaction (entry 9), whereas the reaction still gave 3a in 14% yield without the addition of PCy3 (entry 13), demonstrating the vital role of IPr and the promoting effect of PCy3. In fact, a yield of 68% was detected with IPr alone at an elevated temperature (110 °C) but with poor reproducibility (see the Supplementary Information for details). Other carbenes and phosphines were less effective (entries 10−12 and 14−17). Without Ni(cod)2 or with other nickel species, the reaction did not work (entries 18−20).

Scope of amines and alkynes

Under the optimized conditions, various N-TPS amines were then examined (Fig. 3). Results showed that the reaction tolerated a broad range of functional groups on the phenyl ring of N-benzylamines, including simple alkyl (Me, 3b−3d), electron-donating groups (alkoxy, 3e and 3f), and electron-withdrawing groups (OCF3, F, Cl, CF3, CN, and CO2Me, 3g−3n), providing the corresponding allylic amines in 62−94% yields. In addition, the position of substituents did not have a strong influence on the reaction yield (3b−3d and 3h−3j). Notably, both 1-naphthyl (3o) and heteroaryl (3p) instead of the phenyl of 1a also worked well, affording both 86% yields. When the phenyl was replaced by the alkenyl, a decreased yield was obtained (45%, 3q) in the presence of 10 mol% of the catalyst at 110 °C. Notably, various N-alkylamines were still compatible with the reaction (3r−3u, 41−54% yields), but requiring harsher conditions (130 °C and 20 mol% catalyst) and a Ts protecting group. We reasoned that higher α-C–H bond strength of alkylamines than that of benzylamines and higher activation energy may result in this situation.

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.20 mmol), 2a (0.22 mmol), toluene (2.0 mL) under N2 for 1−12 h; yield of isolated products. *Ni(cod)2 (10 mol%), IPr·HCl (10 mol%), PCy3 (10 mol%), tBuOK (12 mol%) at 110 °C. †Ni(cod)2 (20 mol%), IMes·HCl (20 mol%), PCy3 (20 mol%), tBuOK (22 mol%) at 130 °C. Ts = tolylsulfonyl.

Next, a broad range of alkynes were investigated under the standard conditions (Fig. 4). Various diaryl alkynes bearing alkyls (4a−4e) and electron-donating groups (4f) on the phenyl rings were well compatible with the current reaction, providing the corresponding products in 79−92% yields. Notably, 2-tolylalkyne gave a 1:1 mixture of E:Z isomers (4c), probably because the significant steric hindrance on the aryl ring forced the alkene to isomerize.

In contrast, electron-deficient groups such as OCF3 (4g), F (4h), and CF3 (4i) on the phenyl ring led to slightly lower yields even at a higher temperature. In addition, both dialkyl alkynes (4j and 4k) and alkyl aryl alkynes (4l−4p) were well tolerated, providing both good yields and good to excellent regioselectivities. For example, 1-phenylpropyne gave 8.1:1 regioisomeric ratio (4l), and the change of methyl to ethyl significantly increased the ratio to 20:1 (4m). Bulkier alkyls (4n−4p) or silyl (4q) led to a single regioisomer. However, non-symmetrical dialkyl alkyne (4r) cannot afford good regioselectivity probably owing to low differentiation between isopropyl and methyl groups.

Reaction utility and mechanistic investigation

To demonstrate the utility of the reaction, a gram-scale reaction of the model substrates was conducted under the standard conditions, affording the desired product 3a in 88% yield, without significant loss of the yield (Fig. 5a). In addition, the formed allylic amine 3a can act as a versatile synthetic intermediate to participate into various transformations. For example, hydrogenation followed by typical deprotection protocol of the sulfonyl group provided compound 5 in 68% yield. Moreover, direct oxidation of 3a resulted into a synthetically useful α-amino ketone 6 in 90% yield.

To gain insights into the reaction mechanism, some mechanistic experiments were carried out. Deuterium labeling experiments revealed that 100% allylic deuterium and 94% olefinic deuterium existed in product d−3a, together with deuterated Z-stilbene (12% yield). This result showed that there was partial deuterium-scrambling at the vinylic position, which may be ascribed to a reversible insertion of C=C double bonds in products or stilbene into N−H bonds (Fig. 5b). In addition, deuterated Z-stilbene was obtained, indicating that a part of alkynes were reduced during the reaction process. Crossover experiments between d−1a and 1e suggested that the allylic and olefinic hydrogens may originate from different amide molecules (Fig. 5c), excluding an oxidative addition pathway. The observed kinetic isotopic effect (kH/kD = 2.7 in the intermolecular competitive reaction and kH/kD = 2.2 in parallel reactions, Fig. 5d) implied that the cleavage of the benzylic C−H bond could be involved in the rate-determining step. Notably, in case of dimethylamino benzylic amide 1v as the substrate, imine 1v′ was detected (Fig. 5e). Moreover, the competitive reaction between amide and the imine showed that both of them gave the corresponding products in comparable yields (see Supplementary Information).

These results suggested that an imine intermediate could be involved in the catalytic cycle. In addition, the stoichiometric reaction of a five-membered nickelacycle42,43,44 and amide 1a with or without IPr afforded the desired product 3b in 68% and 9% yields, respectively, suggesting that both the nickelacycle and IPr were critical to the reaction (Fig. 5f). Based on these mechanistic experiments and previous literature reports45,46,47,48,49, a possible reaction mechanism was proposed (Fig. 6). At the induction stage, the nickel-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation of alkyne 2a with amine 1a furnishes Z-stilbene and imine 1a′. Then, 1a′, 2a, and the nickel catalyst undergo an oxidative cyclometallation to generate nickelacycle B, which is subsequently protonated by 1a. The resulting intermediate C then proceeds through a direct intramolecular hydrogen transfer to give Ni−product complex D. Finally, catalyst transfer between D and 2a occurs, releasing product 3a and completing the catalytic cycle.

To further shed light on each individual elementary step of the catalytic reaction, we performed density-functional theory (DFT) calculations on the model reaction of N-benzylbenzenesulfonamide and 2a in the presence of a simplified Ni/NHC catalyst. At the induction stage (Fig. 7a), Ni−amine−alkyne complex IN1 first undergoes a ligand-to-ligand hydrogen transfer (LLHT) via TS1 with an activation Gibbs energy of 14.3 kcal/mol. The resulting intermediate IN2 proceeds through a conformational change into its reactive form IN3. Then, another intramolecular hydrogen transfer occurs via TS2 with an overall activation Gibbs energy of 18.1 kcal/mol, generating Ni−imine−alkene complex IN4. Finally, ligand exchange between IN4 and 2a takes place, leading to Ni−imine−alkyne complex IN5 and Z-stilbene. At the product-formation stage (Fig. 7b), IN5 first undergoes an oxidative cyclometallation via TS3 with an activation Gibbs energy of 23.7 kcal/mol, generating nickelacycle IN6. Then, another amine substrate enters the catalytic cycle, forming hydrogen-bonded complex IN7. Subsequently, an intramolecular proton transfer occurs via TS4, leading to intermediate IN8, which then proceeds through a series of ligand exchange processes. After that, the resulting reactive isomer IN9 transforms into Ni−product complex IN10 via the turnover-limiting intramolecular hydrogen transfer via TS5 with an overall activation Gibbs energy of 24.8 kcal/mol, which is in accordance with the observed kinetic isotopic effect (Fig. 5d). Finally, ligand exchange between IN10 and 2a takes place, releasing the final product and IN5, which triggers the next catalytic cycle. DFT calculations with TPS-protected substrate 1a and IPr ligand indicated that the overall activation Gibbs energy is 22.4 kcal/mol. Replacement of TPS by Ts leads to a higher overall activation Gibbs energy of 24.9 kcal/mol. These results suggested that, as compared with the Ts group, a ca. 30-fold acceleration effect of the TPS group would be expected at 80 °C, which nicely reproduced the experimentally observed superior performance of the TPS protecting group (Fig. 2, entry 1 vs. entry 3). In addition, DFT calculations also suggested that the presence of PCy3 may not reduce the overall activation Gibbs energy of the Ni-catalyzed reaction since replacement of NHC by PCy3 did not promote the turnover-limiting hydrogen transfer step (see Supplementary Fig. 8). Instead, PCy3 may act as an auxiliary ligand to facilitate the generation of the catalytic species and/or to inhibit catalyst deactivation.

Methods

General procedure for hydroaminoalkylation

To a 15 mL pressure tube were added Ni(cod)2 (2.75 mg, 0.01 mmol), IPr·HCl (4.25 mg, 0.01 mmol), PCy3 (2.8 mg, 0.01 mmol), KOtBu (1.34 mg, 0.012 mmol), toluene (2.0 mL), alkynes (0.22 mmol) and amines (0.20 mmol) in a glove box. The tube was sealed with a Teflon cap and the mixture was stirred at 80 or 110 °C for 1–12 h. After cooled to room temperature, the crude product was filtered through a short pad of Celite, and the filtrate was concentrated under vacuum. The resulting residue was obtained by chromatography on silica gel column with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate as the eluent.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information file. For the experimental procedures and data of NMR, see Supplementary Methods in Supplementary Information file. For computed energies and Cartesian coordinates of the stationary points see Supplementary Data 1.

References

Johannsen, M. & Jørgensen, K. A. Allylic amination. Chem. Rev. 98, 1689–1708 (1998).

Skoda, E. M., Davis, G. C. & Wipf, P. Allylic amines as key building blocks in the synthesis of (E)-alkene peptide isosteres. Org. Process Res. Dev. 16, 26–34 (2012).

Schnur, R. C. & Corman, M. L. Tandem [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements in an ansamycin: stereospecific conversion of an (S)-allylic alcohol to an (S)-allylic amine derivative. J. Org. Chem. 59, 2581–2584 (1994).

Petranyi, G., Ryder, N. S. & Stgtz, A. Allylamine derivatives: new class of synthetic antifungal agents inhibiting fungal squalene epoxidase. Science 224, 1239 (1984).

Paul, A. & Seidel, D. α-Functionalization of cyclic secondary amines: Lewis acid promoted addition of organometallics to transient imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8778–8782 (2019).

Chen, W., Ma, L., Paul, A. & Seidel, D. Direct α-C−H bond functionalization of unprotected cyclic amines. Nat. Chem. 10, 165–169 (2018).

Xiao, L.-J. et al. Nickel(0)-catalyzed hydroalkenylation of imines with styrene and its derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3396–3400 (2018).

Paul, S. & Guin, J. Radical C(sp3)−H alkenylation, alkynylation and allylation of ethers and amides enabled by photocatalysis. Green. Chem. 19, 2530–2534 (2017).

Deng, H.-P., Fan, X.-Z., Chen, Z.-H., Xu, Q.-H. & Wu, J. Photoinduced nickel-catalyzed chemo- and regioselective hydroalkylation of internal alkynes with ether and amide α‑hetero C(sp3)−H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13579–13584 (2017).

Xiang, B. et al. Lewis acid catalyzed friedel-crafts alkylation of alkenes with trifluoropyruvates. J. Org. Chem. 81, 3929–3935 (2016).

Wei, G. et al. Enantioselective aerobic oxidative C(sp3)−H olefination of amines via cooperative photoredox and asymmetric catalysis. ACS Catal. 6, 3708–3712 (2016).

Sølvhøj, A., Ahlburg, A. & Madsen, R. Dimethylzinc-initiated radical coupling of β-bromostyrenes with ethers and amines. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 16272–16279 (2015).

Liu, R.-R. et al. Nickel-catalyzed enantioselective addition of styrenes to cyclic n-sulfonyl α-ketiminoesters. ACS Catal. 5, 6524–6528 (2015).

Amaoka, Y. et al. Photochemically induced radical alkenylation of C(sp3)−H bonds. Chem. Sci. 5, 4339–4345 (2014).

Sun, M., Wu, H. & Bao, W. α-Vinylation of amides with arylacetylenes: synthesis of allylamines under metal-free conditions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 11, 7076–7079 (2013).

Wei, Y. & Shi, M. Recent advances in organocatalytic asymmetric Morita-Baylis-Hillman/aza-Morita-Baylis-Hillman reactions. Chem. Rev. 113, 6659–6690 (2013).

Li, L., Zhang, X.-S., Zhu, Q.-L. & Shi, Z.-J. Olefinic C-H bond addition to aryl aldehyde and its N-sulfonylimine via Rh catalysis. Org. Lett. 14, 4498–4501 (2012).

Xie, Y., Hu, J., Wang, Y., Xia, C. & Huang, H. Palladium-catalyzed vinylation of aminals with simple alkenes: a new strategy to construct allylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 20613–20616 (2012).

Zhou, C.-Y., Zhu, S.-F., Wang, L.-X. & Zhou, Q.-L. Enantioselective nickel-catalyzed reductive coupling of alkynes and imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10955–10957 (2010).

Ngai, M.-Y., Barchuk, A. & Krische, M. J. Enantioselective iridium-catalyzed imine vinylation: Optically enriched allylic amines via alkyne-imine reductive coupling mediated by hydrogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12644–12645 (2007).

Kong, J.-R., Cho, C.-W. & Krische, M. J. Hydrogen-mediated reductive coupling of conjugated alkynes with ethyl (N-sulfinyl)iminoacetates: synthesis of unnatural α-amino acids via rhodium-catalyzed C−C bond forming hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 11269–11276 (2005).

Patel, S. J. & Jamison, T. F. Catalytic three-component coupling of alkynes, imines, and organoboron reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 1364–1367 (2003).

Sakaguchi, S., Kubo, T. & Ishii, Y. A three-component coupling reaction of aldehydes, amines, and alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 2534−2536 (2001)

Edwards, P. M. & Schafer, L. L. Early transition metal-catalyzed C−H alkylation: hydroaminoalkylation for Csp3-Csp3 bond formation in the synthesis of selectively substituted amines. Chem. Commun. 54, 12543–12560 (2018).

Roesky, P. W. Catalytic hydroaminoalkylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 4892–4894 (2009).

Chong, E., Garcia, P. & Schafer, L. L. Hydroaminoalkylation: early-transition-metal-catalyzed α-alkylation of amines. Synthesis 46, 2884–2896 (2014).

Ryken, S. A. & Schafer, L. L. N,O-chelating four-membered metallacyclic titanium(IV) complexes for atom-economic catalytic reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 2576–2586 (2015).

Hannedouche, J. & Schulz, E. Hydroamination and hydroaminoalkylation of alkenes by group 3−5 elements: recent developments and comparison with late transition metals. Organometallics 37, 4313–4326 (2018).

Shi, L. & Xia, W. Photoredox functionalization of C−H bonds adjacent to a nitrogen atom. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 7687–7697 (2012).

Nakajima, K., Miyake, Y. & Nishibayashi, Y. Synthetic utilization of α-aminoalkyl radicals and related species in visible light photoredox catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 1946–1956 (2016).

Dong, Z., Ren, Z., Thompson, S. J., Xu, Y. & Dong, G. Transition-metal-catalyzed C−H alkylation using alkenes. Chem. Rev. 117, 9333–9403 (2017).

Buchwald, S. L., Watson, B. T., Wannamaker, M. W. & Dewan, J. C. Zirconocene complexes of imines: general synthesis, structure, reactivity, and in situ generation to prepare geometrically pure allylic amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 4486–4494 (1989).

Grossman, R. B., Davis, W. M. & Buchwald, S. L. Enantioselective, zirconium-mediated synthesis of allylic amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 2321–2322 (1991).

Broene, R. D. & Buchwald, S. L. Zirconocene complexes of unsaturated organic molecules: new vehicles for organic synthesis. Science 261, 1696–1701 (1993).

Harris, M. C. J., Whitby, R. J. & Blagg, J. A practical procedure for the elaboration of amines via zirconocene η2-imine complexes. Tetrahedron Lett. 35, 2431–2434 (1994).

Gao, Y., Yoshida, Y. & Sato, F. In situ generation of titanium-imine complexes from imines and Ti(OiPr)4/2iPrMgX, and their reactions with alkynes, nitriles and imines. Synlett 1353−1354 (1997).

Barluenga, J., Rodriguez, F., Alvarez-Rodrigo, L., Zapico, J. M. & Fananas, F. J. Zirconium-mediated coupling reactions of amines and enol or allyl ethers: Synthesis of allyl- and homoallylamines. Chem. Eur. J. 10, 109–116 (2004).

Cummings, S. A., Tunge, J. A. & Norton, J. R. Synthesis and reactivity of zirconaaziridines. Top. Organomet. Chem. 10, 1–39 (2004).

Kristian, K. E. et al. Mechanism of the reaction of alkynes with a “constrained geometry” zirconaaziridine. PMe3 dissociates more rapidly from the constrained geometry complex than from its Cp2 analogue. Organometallics 28, 493–498 (2009).

Bahena, E. N., Griffin, S. E. & Schafer, L. L. Zirconium-catalyzed hydroaminoalkylation of alkynes for the synthesis of allylic amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 20566–20571 (2020).

Kaper, T. et al. Intermolecular hydroaminoalkylation of alkynes. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 6899–6903 (2021).

Ogoshi, S., Ikeda, H. & Kurosawa, H. Formation of an aza-nickelacycle by reaction of an imine and an alkyne with nickel(0): oxidative cyclization, insertion, and reductive elimination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 4930–4932 (2007).

Ogoshi, S., Ikeda, H. & Kurosawa, H. Nickel-catalyzed [2+2+2] cycloaddition of two alkynes and an imine. Pure Appl. Chem. 80, 1115–1125 (2008).

Hoshimoto, Y., Ohata, T., Ohashi, M. & Ogoshi, S. Nickel-catalyzed synthesis of N-aryl-1,2-dihydropyridines by [2+2+2] cycloaddition of imines with alkynes through T-shaped 14-electron aza-nickelacycle key intermediates. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 4105–4110 (2014).

Yao, W.-W., Li, R., Li, J.-F., Sun, J. & Ye, M. NHC ligand-enabled Ni-catalyzed reductive coupling of alkynes and imines using isopropanol as a reductant. Green. Chem. 21, 2240–2244 (2019).

Cai, Y., Zhang, J.-W., Li, F., Liu, J.-M. & Shi, S.-L. Nickel/N-heterocyclic carbene complex-catalyzed enantioselective redox-neutral coupling of benzyl alcohols and alkynes to allylic alcohols. ACS Catal. 9, 1–6 (2019).

Guihaumé, J., Halbert, S., Eisenstein, O. & Perutz, R. N. Hydrofluoroarylation of alkynes with Ni catalysts. C−H activation via ligand-to-ligand hydrogen transfer, an alternative to oxidative addition. Organometallics 31, 1300–1314 (2012).

Nakai, K., Yoshida, Y., Kurahashi, T. & Matsubara, S. Nickel-catalyzed redox-economical coupling of alcohols and alkynes to form allylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 7797–7800 (2014).

McCarren, P. R., Liu, P., Cheong, P. H.-Y., Jamison, T. F. & Houk, K. N. Mechanism and transition-state structures for nickel-catalyzed reductive alkyne−aldehyde coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6654–6655 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21871145, 21933003, and 91856104), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (63191601), High-Performance Computing Platform of Peking University, and National Supercomputing Center in Shenzhen (Shenzhen Cloud Computing Center).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.-W.Y. discovered and developed the reactions. R.L., H.C., M.-K.C. performed part of synthetic experiments. Y.-X.L., Y.W., Z.-X.Y. performed the DFT calculations and analyzed the computational results, Y.-X.L., M.Y. conceived, designed the investigations and wrote the manuscript. W.-W.Y. wrote the Supplementary Information.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Stephen G. Newman and Shi-Liang Shi for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, WW., Li, R., Chen, H. et al. Ni-catalyzed hydroaminoalkylation of alkynes with amines. Nat Commun 12, 3800 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24032-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24032-9

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.