Abstract

To the best of our knowledge, bridgehead carbon benzofused-bridged ring systems have previously not been accessible to the synthetic community. Here, we describe a formal type-II [4 + 4] cycloaddition approach that provides fully sp2-carbon embedded anti-Bredt bicyclo[5.3.1] skeletons through the Rh-catalyzed C1–C8 activation of benzocyclobutenones (BCBs) and their coupling with pedant dienamides. Variously substituted dienamides have been coupled with BCBs to provide a range of complex bicyclo[5.3.1] scaffolds (>20 examples, up to 89% yield). The bridged rings were further converted to polyfused hydroquinoline-containing tetracycles via a serendipitously discovered transannular 1,5-hydride shift/Prins-like cyclization/Schmidt rearrangement cascade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

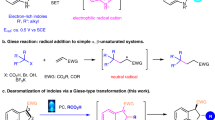

Bridged ring systems are key structural motifs in many important functional molecules1,2,3. The skeleton were characterized by its size (e.g., bicyclo[m.n.1]) and ring strain (hybridization form of the bridgehead carbon (BC)). While the sp3-hybridized BC are commonly seen in many natural products, the sp2-hybridized BC underpins certain limitation on both the ring size (m + n ≥ 7) as well as ring strain3. However, consecutive sp2-hybridized carbon centers and/or bridgehead benzofused [m.n.1] systems are unusual (m + n > 8) and, to the best of our knowledge, unknown to chemist when it was confined in a small ring (m + n ≤ 8) framework (Fig. 1a)4,5. We are herein set off to challenge these limitations. Bicyclo[5.3.1] bridged ring systems with anti-Bredt olefins at the bridgehead position are widely found in bioactive natural products (Fig. 1b)6,7,8, whose total synthesis was highly dictated by the efficiency of assembling such scaffolds9,10. The state-of-art cycloaddition methods in constructing anti-Bredt bicyclo[5.3.1] scaffolds11,12,13,14 are two: (1) type-II intramolecular Diels–Alder reactions developed by Shea et al.15,16, which requires activating substituent on dienophile, otherwise the reactions are mostly in gas phase; (2) a seminal report by Wender et al.17,18 using Ni-catalyzed type-II [4 + 4] intramolecular cycloaddition under diluted conditions between 1,3-dienes (Fig. 1c)19. A general, catalytic and diversifiable cycloaddition strategy remained elusive, especially for the highly strained anti-Bredt20,21 bridged skeletons. The transition metal-catalyzed intramolecular [4 + 2] annulation via C1–C2 bond activation22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 of benzocyclobutenones (BCBs) has emerged as an attractive approach for preparing fused- and bridged ring systems pioneered by Liebeskind34 and Dong35,36 (Fig. 1d). However, no catalytic [4 + 4] annulation via oxidative C–C activation has been known, not to mention forming the highly strained anti-Bredt bridged ring systems37. Accessing anti-Bredt bridged bicycles remained elusive since only a few examples had been known starting from cyclobutanones38,39,40,41,42,43. To the best of our knowledge, no report had been known to construct bridged ring systems that bears highly strained consecutive double bond surrounding the BC.

a Hybridization of bridgehead carbon of [m.n.1] skeleton. b Representative NPs containing anti-Bredt bicyclo[5.3.1] scaffolds. c State-of-art cycloaddition approaches for anti-Bredt bicyclo[5.3.1] rings. d “Cut and sew” type [4 + 2] using BCBs and CBs pioneered by Dong, etc. e Our design: bridged ring formation via [4 + 4] annulation from BCBs.

Herein, we disclose our discovery of a type-II [4 + 4] annulation between BCBs and dienamides enabled by Rh-catalyzed regioselective C1–C8 bond activation (Fig. 1e).

Results and discussion

The challenges are three-fold: (1) there is no precedent report of benzo-fused BC in bicyclo[5.3.1] systems; (2) the kinetically C1–C8 rhodaindanone would be readily isomerize to its thermodynamically stable C1–C2 cleaved counterpart44; (3) competitive fused ring formation through normal cut and sew pathway. Our investigation commenced with preparation of 1a through amide formation in 72% yield between our previously reported 3-NHMe BCB and the known dienoic acid (see supporting information (SI) for detail)45. We tested our hypothesis by using 2.5 mol% of [Rh(nbd)Cl]2 and 12 mol% of DPPP, unfortunately, only the fused tricycle 2a′ was isolated in 45% yield, presumably from the “cut and sew” process followed by a double bond migration (entry 1, Fig. 2). It is noted that the type-I [4 + 4] benzofused ring46,47 product was not observed. When switching to other bidetate ligand with varied bite-angles, namely (S)-H8-BINAP and (S,S)-DIOP. Surprisingly, the desired anti-Bredt benzofused aza-bicyclo[5.3.1] bridged product 2a was successfully isolated (45% and 40% yield, respectively) together with the side product 2a′ (38% and 47% yield, respectively, entry 2 and 3). In both cases, product 2a’s ee values were 0. These results led us to speculate that only one phosphine-center served as dative ligand based on the 18d-electron rule. Mono-dentate P(4-CF3Ph)3 greatly improved the selectivity yielding only 2a in 51% yield (entry 4). However, the analogous P(C6F5)3 only lead to significantly decreased yield of 2a (21%) and selectivity (39% yield of 2a′), presumably due to the loose coordinating ability owing to its π-acidity as well as the large cone angle (entry 5)48. The electron-rich P(4-OMePh)3 provided elevated yield (50%) of 2a albeit with 73% conversion (entry 6). Surprisingly, it was found that the feedstock PPh3 provide the highest 72% isolated yield based on 85% conversion while preserving the complete selectivity for the bridged products (entry 7, with light yellow background). Encouraged by this result, a series of pre-catalysts were screened, but the yields of 2a ranged between 9 and 32% (entry 8–10). The Wilkinson catalyst was also used but proved less chemoselective as both 2a and 2a′ were obtained (entry 11). An attempt to lower the reaction temperature from 150 to 110 °C proved unfruitful, as 2a was only obtained in 10% yield with most of 1a recovered (entry 12). The Rh/ligand ratio was also proved crucial to the success of this [4 + 4] annulation pathway, since decreased efficiency (28% yield of 2a) and loss of selectivity (38% yield of 3a) was observed when lowering the loading of PPh3 (entry 13). Toluene is an inferior solvent (entry 14). First row late transition metal are known to cleave C1–C8 bond of BCB, but Co0 and Ni0 complex were tested and proved less efficient (entry 15–16).

With optimal condition in hand, we set off to explore the reaction scope (Fig. 3). A broad series of dienamide coupled BCB substrates with different steric and electronic properties have been examined. Delightedly, good to high yields of bicyclo[5.3.1] bridged rings were obtained. It was found that changing the electronegativity of aryl substituents on δ-position of dienamides (1a–1d) does not affect the efficacy, and 68–75% yields were obtained, with a slight trend for para-substituted effect favoring electron-withdrawing groups (entry 1–4, Fig. 3). The alkyl substituents at α and β-position of dienamide were also investigated (entry 5–8). It was gratifyingly to find that ethyl (1e), cyclopropylmethyl (1f) as well as hydrogen (1g–h) at α-position were all well tolerated yielding desired bridged products 2e–h in useful yields (46–65%). It is noteworthy that no cleavage of cyclopropyl moiety was detected, revealing good chemoselectivity of this catalyst system. Variation of R group on the nitrogen promised potential use in complex settings, as 89% yield of 2i was isolated (95% brsm), when Bn (1i) was used (entry 9). Increasing the steric bulkiness to cyclopropylmethyl (1j) resulted in no less efficiency (79% yield of 2j, entry 10). The reaction demonstrated excellent chemoselectivity when 1k was employed as substrate, only bridged [4 + 4] product 2k (79% yield, 94% brsm) was observed but no traditional [4 + 2] product (entry 11). The robustness toward electronic variation on BCB was enlightened by obtaining 2l in 66% yield (81% brsm, entry 12). A grand challenge in “migratory insertion” is the unviability of sterically demanding multi-substituted olefins as coupling partners, presumably due to their low binding affinity. We postulated that dienamides are potential chelating ligands, which increased their binding ability to the rhodaindanone complex. The tetrasubstituted dienamide 1m was synthesized and the resulting [4 + 4] annulation product 2m (84% brsm yield) was undoubtedly verified through X-ray crystallography together with the aforementioned 2l (entry 12 and 13). A major competitive side reaction after migratory insertion is the tendency to undergo β-H elimination when a β-H is available. Gratifyingly, in our trials to effect the alkyl substituted dienamides 1n and 1o to the benzo-fused bridged skeletons, high to moderate yields were obtained, respectively, for 2n (89% yield) and 2o (52% yield) as the only isolated product in each case (entry 14 and 15). The terminal dienamide 1p underwent a certain decomposition which cause isolation of desired 2p in 31% yield albeit with moderate 67% brsm yield (entry 16). When the electronic property of dienamide was altered (1q), the desired [4 + 4] annulation took place without loss of efficacy, obtaining 2q in 60% yield (entry 17). It was very encouraging to find that extended conjugated tetraenamide 1r react smoothly yielding 2r in 54% yield and the electron-rich furan moiety was well preserved (entry 18). When using even challenging (possessing cis-terminal olefins) cyclic dienamides 1s–u, the desired [4 + 4] annulation reactions proceeded without any difficulties, affording 2s~u in synthetically useful yields (54–58%, entry 19–21). The product 2t and 2u suggested that aromaticity can be deprived, since the X-ray crystallographic experiment undisputedly showed an exo-olefin for product 2u even with the possibility for re-aromatization (Fig. 3, bottom). This might be caused by the highly strained anti-Bredt aza-bicyclo[5.3.1] skeleton. An effort to generate enantioselective bridged rings through chiral substrate induction was carried out using 1v, delightedly, the resulting product 2v and 2v′ was obtained in a 1:1 ratio as inseparable isomers in a combined 86% yield (entry 22). These provide valuable clues in our future endeavor toward enantioselective [4 + 4] annulation study. Additionally, we also found the ether substrate 1w yielded desired [4 + 4] product 2w, albeit in 12% yield. This indicated that our [4 + 4] conditions can be extrapolated to O linked diene substrate albeit in low yield (entry 23).

With the highly diastereomerically pure benzo-fused bridged cyclic compounds 2 in hand, we hypothesized that if a Schmidt rearrangement reaction can be performed (Fig. 4), which would further extended the structural diversity49,50,51,52,53 based on this [4 + 4] annulation strategy. In addition, it may be considered as a reaction surrogate for using the oxindole 3 as the annulation substrate, which has been an elusive substrate in C–C bond activation due to the more reactive amide bonds.

After extensive investigations, we were delighted to discover that the bicyclo[5.3.1] bridged tricycles can readily undergo a clean rearrangement reaction with isolated yields ranging from 51 to 62% yield (Fig. 5). A careful cultivation of a single crystal of the product 5g/5n and X-ray crystallographic analysis revealed that a densely functionalized and polyfused ring systems were obtained. Product 5 consists of a highly congested tetracyclic fused ring cycle rather than the designed simple Schmidt reaction in scheme 1. The mechanism of this transformation was probed using deuterated product 2a-D as substrate, which was synthesized from correspond 1a-D in 78% isolated yield using our standard [4 + 4] conditions (see SI for detail). The fused tetracyclic product 5a-D was successfully obtained in 64% yield indicating an unambiguous transannular 1,5-deuteryde transfer involved in the cascade skeleton rearrangement (Fig. 6). The dihydroquinoline moiety is a strong evidence of a cation-induced Schmidt rearrangement with NaN3 presumably after the hydride shift (detailed mechanism is provided vide infra).

Based on the previous report and the deuterium experiment, we tentatively proposed the catalytic cycle of the Rh-catalyzed [4 + 4] annulation between BCBs and pedant dienamides, together with the mechanism of the cascade skeleton rearrangement to form fused tetracycles from bridged bicyclo[5.3.1]undecane (Fig. 7, upper cycle). The C1–C8 oxidative addition with RhI complex took place first regioselectively, and the equilibration from II to the C1–C2 cleaved rhodaindanone (green) was competitively overrode by the regioselective migratory insertion into γ,δ-olefin due presumably to readily coordination with Rh-center. The resulting penta/hexa coordinated intermediate II was proposed to undergo a migratory insertion with the dienamide, yielding intermediate III. The RhIII complex III will undergo reductive elimination thanks to the excess PPh3 ligand, providing the benzofused aza-bicyclo[5.3.1]undecandienone 2.

To gain insight for our hypothesis of alkyl C8-Rh undergoing migratory insertion rather than acyl C1-Rh into the distal olefin, compound 6 was designed, prepared, and subjected to the standard [4 + 4] conditions. A formal [4 + 2 − 1] annulated product 7 was obtained in 76% yield (Fig. 8). The formation of product 7 indicated that C8-Rh migratory inserted into the terminal olefins first, followed by decarbonylation and reductive elimination. Otherwise, the decarbonylation could not be realized if acyl C1-Rh migrated first.

In the cascade reaction (Fig. 7, lower cycle), the bridged carbonyl group activated by catalytic H2SO4 will initiated a through space 1,5-hydride transfer followed by a quick E1-type elimination from IV, affording hydride (pink) shifted intermediate V. The benzyl alcohol V will be protonated by the acid generating benzylic cation, which will induce a Prins-type cyclization obtaining VI. The intermediate VI will be trapped by NaN3 and trigger a Schmidt rearrangement yielding the final polyfused hydroquinoline-containing tetracycle 5.

In summary, we have discovered a Rh-catalyzed type-II [4 + 4] annulation between BCBs and pedant dienamide constituting the first synthesis of the anti-Bredt bridgehead benzofused aza-bicyclo[5.3.1] ring system. The methodology featured low catalyst loading (2.5 mol%) and neutral reaction condition with broad substrate scope (23 examples) and high efficiency (up to 89% yield). The mechanism probing experiment supported that an unusual alkyl C8-Rh bond undergoes migratory insertion into distal olefin first. To further diversify the anti-Bredt bridged ring systems, a cascade transformation consisting of transannular 1,5-hydride shift, E1 elimination, Prins-like cyclization, and Schmidt rearrangement was discovered, generating polyfused tetracyclic ring systems. A deuterated experiment supported the 1,5-hydride transfer mechanism.

Methods

Procedure for rh-catalyzed type-II [4 + 4] annulation to make 2a

A 4 ml oven-dried vial was transferred in a N2-filled glove box and was charged with 1a (40 mg, 0.126 mmol), [Rh(nbd)2Cl]2 (1.5 mg, 3.15 μmol), PPh3 (4.0 mg, 0.015 mmol), and 1,4-dioxane (3.7 ml) and the vial was capped. The vial was stirred at 150 °C for 96 h. Upon completion, it was cooled to room temperature. The solvent was removed by rotavap under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by flash chromatography to afford desired product 2a (28.8 mg) in 72% yield and partial 1a (4.9 mg) was recovered. The benzofused bicyclo[5.3.1] products can be further applied in a number of transformations (Fig. 9), Chemoselective reduction can be achieved by using different reagents, e.g., olefin could be hydrogenated obtaining saturated backbone 8 in 72% yield. Ketone and amide functional groups could be reduced to alcohol (9 in 82% yield as a single isomer) and methylene (10 in 60% yield), respectively, with different hydride reagents. In addition, product 2a could underwent nucleophilic attack with vinyl Grignard reagent yielding 11 as a single diastereoisomer (45% yield). When a methylene sulfur ylide was used, an expoxidation product will be isolated in 65% from 2l. A quasi-Favorskii reaction can be performed using aqueous NaOH, the fused tricycle product 13 was afforded in 30% yield.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. Raw data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Materials and methods, experimental procedures, characterization data, 1H, 13C, 19F NMR spectra, and mass spectrometry data are available in the Supplementary Information. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 1873018 (2a), 1873019 (2b), 1873021 (2j), and 1873022 (2n). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Mak, J. Y. W., Pouwer, R. H. & Williams, C. M. Natural products with anti-Bredt and bridgehead double bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 13664–13688 (2014).

Krenske, E. H. & Williams, C. M. Do anti-Bredt natural products exist? Olefin strain energy as a predictor of isolability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10608–10612 (2015).

Maier, W. F. & Schleyer, P. V. R. Evaluation and prediction of the stability of bridgehead olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 1891–1900 (1981).

Tashiro, M. & Ymato, T. A novel reaction of 8,16-bis(bromomethyl)[2.2]metacyclophanes with phenyl lithium and preparation of 8,16-unsymmetrically disubstituted [2.2]metacyclophanes. Chem. Lett. 11, 61–64 (1982).

Tashiro, M. & Ymato, T. Metacyclophane and related compounds. Part 11. Reaction of 8,16-bis(bromomethyl)[2.2]metacyclophane and 8,16-bis(bromomethy1)-5,13-di-t-butyl[2.2]metacyclophane with Grignard reagents. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin. Trans. I, 2165–2171 (1984).

Appendino, G., Gariboldi, P. & Nano, G. M. Crispolide, an unusual hydroperoxysesquiterpene lactone from Tanacetum vulgare. Phytochemistry 21, 1099–1102 (1982).

Bohlmann, F. et al. Two sesquiterpene lactones with an additional propiolactone ring from Disynaphia halimifolia. Phytochemistry 20, 1077–1080 (1981).

Tempesta, M. S. et al. A new class of sesterterpenoids from the secretion of ceroplastes rubens (Coccidae). J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1182–1183 (1983).

Paquette, L. A., Hormuth, S. & Lovely, C. J. Studies directed toward the total synthesis of Cerorubenic Acid-III. 4. Exploration of an organometallic approach to construction of the eastern sector. J. Org. Chem. 60, 4813–4821 (1995).

Liu, X. et al. Asymmetric total synthesis of cerorubenic acid-III. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2872–2877 (2019).

Zhao, W. Y. Novel syntheses of bridge-containing organic compounds. Chem. Rev. 110, 1706–1745 (2010).

Ruiz, M. et al. Domino reactions for the synthesis of bridged bicyclic frameworks: fast access to bicyclo[n.3.1]alkanes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3445–3454 (2011).

Liu, J. et al. Total synthesis of natural products containing a bridgehead double bond. Chem 6, 579–615 (2020).

Min, L., Liu, X. & Li, C.-C. Total synthesis of natural products with bridged Bicyclo[m.n.1] ring systems via type II [5 + 2] cycloaddition. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 703–718 (2020).

Bear, B. R., Sparks, S. M. & Shea, K. J. The type 2 intramolecular diels–alder reaction: synthesis and chemistry of bridgehead alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 820–849 (2001).

Shea, K. J. et al. Applications of the intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction to the formation of strained molecules. Synthesis of bridgehead alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104, 5708–5715 (1982).

Wender, P. A. & Snapper, M. L. Intramolecular nickel catalyzed cycloadditions of bis-dienes: 3 approaches to the taxane skeleton. Tetrahedron Lett. 28, 2221–2224 (1987).

Wender, P. A. & Tebbe, M. J. Nickel(0)-catalyzed intramolecular [4 + 4] cycloadditions: 5. The type II reaction in the synthesis of Bicyclo[5.3.1]Undecadienes. Synthesis 1991, 1089–1094 (1991).

Kennedy, C. R. et al. Regio- and diastereoselective iron-catalyzed [4 + 4]-cycloaddition of 1,3-dienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8557–8573 (2019).

Bredt, J. Steric hindrance in the bridge ring (Bredt’s rule) and the meso-trans-position in condensed ring systems of the hexamethylenes. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 437, 1–13 (1924).

Warner, P. M. Strained bridgehead double-bonds. Chem. Rev. 89, 1067–1093 (1989).

Jones, W. D. The fall of the C-C bond. Nature 364, 676–677 (1993).

Murakami, M. & Ito, Y. Cleavage of Carbon—Carbon Single Bonds by Transition Metals. Top. Organomet. Chem. 3, 97–129 (1999).

Rybtchinski, B. & Milstein, D. Metal insertion into C−C bonds in solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 870–883 (1999).

Necas, D. & Kotora, M. Rhodium-catalyzed C-C bond cleavage reactions. Curr. Org. Chem. 11, 1566–1591 (2007).

Ruhland, K. Transition-metal-mediated cleavage and activation of C-C single bonds. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2683-2706 (2012).

Dong, G. C–C bond activation. (Springer, 2014)

Souillart, L. & Cramer, N. Catalytic C–C Bond Activations via Oxidative Addition to Transition Metals. Chem. Rev. 115, 9410–9464 (2015).

Murakami, M. & Ishida, N. Cleavage of Carbon–Carbon Single Bonds by Transition Metals. (Wiley-VCH, 2015).

Fumagalli, G., Stanton, S. & Bower, J. F. Recent Methodologies that exploit C–C single-bond cleavage of strained ring systems by transition metal complexes. Chem. Rev. 117, 9404–9432 (2017).

Chen, P.-H. et al. “Cut and Sew” Transformations via Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Carbon–Carbon Bond Activation. ACS Catal. 7, 1340–1360 (2017).

Deng, L. & Dong, G. Carbon–Carbon bond activation of ketones. Trends in Chemistry 2, 183–198 (2020).

Murakami, M. & Ishida, N. Cleavage of Carbon–Carbon σ-Bonds of Four-Membered Rings. Chem. Rev. 121, 264–299 (2021).

South, M. S. & Liebeskind, L. S. Regiospecific Total Synthesis of (±)-Nanaomycin A Using Phthaloylcobalt Complexe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 4181–4185 (1984).

Xu, T. & Dong, G. Rhodium-Catalyzed Regioselective Carboacylation of Olefins: A C–C Bond Activation Approach for Accessing Fused-Ring Systems. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 51, 7567–7571 (2012).

Xu, T. et al. Highly Enantioselective Rh-Catalyzed Carboacylation of Olefins: Efficient Syntheses of Chiral Poly-Fused Rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 20005–20008 (2012).

Julià-Hernández, F. et al. Nickel-Catalyzed Chemo-, Regio- and Diastereoselective Bond-Formation through Proximal C-C Cleavage of Benzocyclobutenones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9537–9541 (2015).

Ko, H. M. & Dong, G. Cooperative Activation of Cyclobutanones and Olefins Leads to Bridged Ring Systems by a Catalytic [4 + 2] Coupling. Nat. Chem. 6, 739–744 (2014).

Souillart, L., Parker, E. & Cramer, N. Highly Enantioselective Rhodium(I)-Catalyzed Activation of Enantiotopic Cyclobutanone C–C Bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 53, 3001–3005 (2014).

Souillart, L. & Cramer, N. Highly Enantioselective Rhodium(I)-Catalyzed Carbonyl Carboacylations Initiated by C–C Bond Activation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 53, 9640–9644 (2014).

Zhou, X. & Dong, G. (4 + 1) vs (4 + 2): Catalytic Intramolecular Coupling between Cyclobutanones and Trisubstituted Allenes via C–C Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 13715–13721 (2015).

Liu, L., Ishida, N. & Murakami, M. Atom- and Step-Economical Pathway to Chiral Benzobicyclo[2.2.2]octenones through Carbon–Carbon Bond Cleavage. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 51, 2485–2488 (2012).

Hou, S.-H. et al. Enantioselective Type II Cycloaddition of Alkynes via C–C Activation of Cyclobutanones: Rapid and Asymmetric Construction of [3.3.1] Bridged Bicycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 13180–13189 (2020).

Lu, G. et al. Computational Study of Rh-Catalyzed Carboacylation of Olefins: Ligand-Promoted Rhodacycle Isomerization Enables Regioselective C-C Bond Functionalization of Benzocyclobutenones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 8274–8283 (2015).

Qiu, B. et al. Catalytic enantioselective synthesis of 3, 4-polyfused oxindoles with quaternary all-carbon stereocenters: a Rh-catalyzed C–C activation approach. Org. Lett. 20, 7689–7693 (2018).

Yu, Z.-X., Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Cycloadditions for the Synthesis of Eight-Membered Carbocycles. Chem. Asian J. 5, 1072–1088 (2010).

Wang, Y. & Yu, Z.-X. Rhodium-Catalyzed [5+2+1] Cycloaddition of Ene–Vinylcyclopropanes and CO: Reaction Design, Development, Application in Natural Product Synthesis, and Inspiration for Developing New Reactions for Synthesis of Eight-Membered Carbocycles. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 2288–2296 (2015).

Brown, T. L. & Lee, K. J. Ligand steric properties. Coord. Chem. Rev. 128, 89–116 (1993).

Tambar, U. K. & Stoltz, B. M. The direct acyl-alkylation of arynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 5340–5341 (2005).

Zhu, C. et al. Enantioselective palladium-catalyzed intramolecular α-arylative desymmetrization of 1,3-diketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16486–16489 (2017).

Wang, M. et al. Radical-mediated C-C cleavage of unstrained cycloketones and DFT study for unusual regioselectivity. Nat. Commun. 11, 672 (2020).

Fu, X.-F., Xiang, Y. & Yu, Z.-X. RhI-Catalyzed Benzo/[7+1] Cycloaddition of Cyclopropyl‐Benzocyclobutenes and CO by Merging Thermal and Metal‐Catalyzed C-C Bond Cleavages. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 4242–4246 (2015).

Wang, L.-N. & Yu, Z.-X. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Cycloadditions for the Synthesis of Eight-Membered Carbocycles: An Update from 2010 to 2020. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 40, 3536–3558 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The project was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (202041003), NSFC (Nos. 81991522, U1706213, and 81973232) and Shandong Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (ZR2020JQ32) for financial support. The projected was partially funded by National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2018ZX09735-004), Youth Innovation Plan of Shandong Province (2019KJM004) and Jinan municipal government fund (2019GXRC039). T.X. is a Taishan Youth Scholar (tsqn20161012). GBD of U. Chicago is acknowledged for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.X. conceived the project and wrote the manuscript. J.Z. performed all the key reactions, collected data, and prepared SI. X.W. helped preparing BCB and collecting data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Wang, X. & Xu, T. Regioselective activation of benzocyclobutenones and dienamides lead to anti-Bredt bridged-ring systems by a [4+4] cycloaddition. Nat Commun 12, 3022 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23344-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23344-0

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.