Abstract

Sn-based compounds with buffer matrixes possessing high theoretical capacity, low working voltage, and alleviation of the volume expansion of Sn are ideal materials for lithium storage. However, it is challenging to confine well-dispersed Sn within a lithium active matrix because low-melting-point Sn tends to agglomerate. Here, we apply a metal-organic framework (MOF) chemistry between Sn-nodes and lithium active ligands to create two Sn-based MOFs comprising Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) with extended ligands from H4dobdc (2,5-dioxido-1,4-benzenedicarboxylate acid) to H4dobpdc (4,4’-dioxidobiphenyl-3,3’-dicarboxylate acid) with molecule-level homodispersion of Sn in organic matrixes for lithium storage. The enhanced utilization of active sites and reaction kinetics are achieved by the isoreticular expansion of the organic linkers. The reversible formation of coordination bonds during lithium storage processes is revealed by X-ray absorption fine structure characterization, providing an in-depth understanding of the lithium storage mechanism in coordination compounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

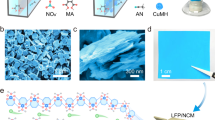

Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have been widely applied in portable electronic products to electric vehicles due to their high energy and power densities1,2,3,4. At present, the most commonly used graphite-based anode materials possess a low theoretical capacity of 372 mAh g–1 (based on the formation of LiC6) and confront lithium deposition and solvent intercalation issues caused by the fairly low working potential5,6. As high-capacity anode materials, Sn-based materials, such as Sn, SnO, and SnO2, have been considerably explored because of the natural abundance of Sn, high theoretical capacity of 994 mAh g–1 (based on the formation of Li22Sn5) and suitable anodic voltage7,8,9,10,11. However, the large volume variation (~260%) of Sn-based materials during Li alloying and dealloying usually causes the problems of mechanical fracture, swelling of particles and unstable solid-electrolyte interface (SEI) layers, hindering the reaction kinetics and decreasing the cycling stability12,13. The strategies of nanocrystallization, alloying modification and application of a carbon matrix coating have been applied to exploit desirable electrode materials to accommodate the volume change and improve the interface contact (Fig. 1a)8,9,14,15,16,17,18,19. However, the relatively low compaction density of the nanomaterials and the large amounts of lithium-inactive matrixes added to the Sn electrodes reduce the energy density of the entire batteries20. Moreover, the synthesis of such materials usually requires complex and rigorous processes21.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), as a new generation of hybrid and crystalline materials, are constructed with metal nodes and organic linkers through coordination bonds22,23,24 and have promising applications for lithium storage because their regular and tunable compositions and pore structures with tunable surface areas could provide both active sites for lithium storage and well-defined pathways for lithium ion transport25,26,27,28,29,30. The construction of Sn-based MOFs with Sn–O coordination bonds could overcome the drastic volume change of Sn anodes because the coordination interactions can uniformly anchor or release the Sn atoms to the organic matrix and hinder particle growth and aggregation (Fig. 1b). In addition, the organic ligands could also offer active sites for additional lithium storage31. By combining the merits of alloy-type metal centers and active organic ligands, well-designed Sn-MOF electrodes could be applied for lithium storage. To the best of our knowledge, the elaborate design and construction of Sn-based MOFs for lithium storage have not been reported. In fact, recent attempts regarding MOFs as anode materials in LIBs mainly involved transition metal-based MOFs with moderate electrochemical performance (Supplementary Table 1), where reversible lithium storage is based on the conversion reaction of metal centers and a charge-state change of the electroactive groups28,29,30,32. Most of them deliver relatively low reversible capacities, especially at high current densities, and are plagued by long-term cycling issues. The lithium storage mechanisms of these reported MOF-based anodes have been investigated by using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which usually provide useful information at the nanoscale, but the atomic accuracy level for coordination compounds is still unclear.

In this paper, we report that high-performance anode materials for LIBs can be obtained by a combination of coordination chemistry and electrochemistry. This approach is demonstrated by two isoreticular Sn-based MOFs from Sn2(dobdc) with a small 2,5-dioxido-1,4-benzenedicarboxylate acid (H4dobdc) linker to Sn2(dobpdc) with an extended 4,4’-dioxidobiphenyl-3,3’-dicarboxylate acid (H4dobpdc) linker (Fig. 1c). The coordination units formed by the Sn2+ ions and organic ligands can not only effectively utilize the abundant active sites affording high specific capacity but also alleviate the volume change, guaranteeing reversible reactions for long-term cycling stability. Importantly, the extension of the ligand resulted in enhanced utilization of active sites and favorable reaction kinetics for Sn2(dobpdc) with an isoreticularly extended framework structure, presenting a high reversible capacity of 1018 mAh g–1 over 200 cycles and excellent rate capability, which outperforms other coordination compounds (Supplementary Table 1). Combined studies with in situ powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS), high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) characterization, ex situ FTIR and XPS spectroscopy and theoretical modeling provided a detailed analysis of the lithium storage mechanism in these Sn-based MOFs, highlighting that the reversible formation of coordination bonds is the core and foundation to solve particle agglomeration and achieve satisfactory active site utilization in coordination compounds.

Results

Structure and basic characterizations

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies revealed that both Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) crystallize in the monoclinic P21/c space group (Supplementary Table 2). The framework of Sn2(dobpdc) is analogous to Sn2(dobdc), featuring the same coordination spheres of Sn2+ ions but an enlarged spacing between the Sn2+ ions due to the extended dobpdc4− linker. The structure of Sn2(dobpdc) is described here representatively. There is one crystallographically independent Sn2+ ion that lies in a nonsymmetric disphenoidal coordination environment and is coordinated by four oxygen atoms from three different dobpdc4- ligands (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The Sn–O bond lengths are in the range from 2.065(6) to 2.181(3) Å. The selected bond lengths and angles are provided in Supplementary Table 3, which are in the range of other types of Sn-based coordination compounds33. The Sn2+ ions are bridged by μ2-η1:η1 carboxylate groups into Sn–COO chains along the b axis, which are further connected via dobpdc4– to form a 3D framework (Supplementary Fig. 1b‚c). Topologically, the organic ligand and Sn2+ ion can be viewed as six- and three-connected nodes, respectively. Thus, the framework can be viewed as a (3,6)-connected rtl net (Supplementary Fig. 2)34. Due to the expanded linkers, the distances between the Sn–COO chains increase from 8.8672(12) Å for Sn2(dobdc) to 13.1427(16) Å for Sn2(dobpdc). The morphologies of Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) were observed by SEM (Supplementary Fig. 3), revealing the uniformity of these crystals.

Both Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) maintain their phase purity and structural stability after immersion in the electrolyte for 7 days, demonstrating high electrolyte resistance (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thermogravimetric analysis showed that Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) are stable up to 500 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere (Supplementary Fig. 5). The thermal stabilities of Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) were further evaluated by in situ variable-temperature PXRD measurements on a Pt sample platform in the temperature range from 50 to 600 °C (Supplementary Fig. 6). The PXRD patterns for both MOFs remain unchanged until 500 °C, further demonstrating their excellent thermal stability. The high stabilities of Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) are uncommon for Sn-based coordination compounds due to the strong coordination bonds and 3D rigid framework structures, which are suitable for lithium storage studies. Furthermore, the electrical conductivities of Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) are 2.9 × 10−7 and 9.8 × 10−7 S cm−1, evaluated by linear sweep voltammetry measurements (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8).

Electrochemical performance

Taking advantage of the multiple lithium storage active sites from the alloying-type Sn centers and electrochemically active groups of organic ligands, Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) were evaluated as anode materials for LIBs in CR2032 coin-type cells at 298 K. According to the reversible reaction of Sn-based oxides with lithium10, the electrochemical process of Sn-MOFs with lithium is expected to undergo a combination of electrochemical conversion and alloying mechanisms, with the following two steps: Sn2L + 4Li+ + 4e– ↔ 2Sn + Li4L (L4– = dobdc4− or dobpdc4−) and Sn + xLi+ + xe– ↔ LixSn (0 ≤ x ≤ 4.4). To investigate this redox chemistry for lithium storage, the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves for both MOFs were measured at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s–1 between 0.01 and 3.0 V (Fig. 2a, b). It is noted that the first cathodic scan with two irreversible cathodic peaks in the ranges of 0.7–1.1 V and 0.3–0.6 V differs from the subsequent scans. This behavior is attributed to the formation of a SEI layer that causes the initial capacity loss35,36. The activation of Sn-MOFs to form amorphized materials also occurs during the first lithiation process (a detailed analysis is in the in situ PXRD section). After the first cycle, two pairs of distinctive redox peaks are observed, which are attributed to the gradual insertion or extraction of Li+ within the organic ligands and metal centers, respectively. The peak at 0.8 V is due to lithium insertion into the conjugated aromatic ligand with a reduction in the Sn centers, while the peak at 0.2 V is ascribed to the alloying reaction of lithium with Sn. All peaks remain invariable after the first cycle, confirming the presence of reversible and stable electrochemical reactions. Figure 2c, d display the first five galvanostatic discharge–charge profiles of the cells at 100 mA g–1. Sn2(dobpdc) shows a lower discharge plateau than Sn2(dobdc). After the formation of the SEI layers with an initial irreversible capacity loss, both Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) exhibit stable lithium storage behaviors, indicating few side reactions of the electrolyte. Two sloping discharge plateaus for Sn2(dobdc) are observed in the ranges of 1.2–0.6 V and 0.45–0.15 V, and the discharge plateaus for Sn2(dobpdc) are in the ranges of 0.8–0.5 V and 0.4–0.1 V (Fig. 2c, d), which agree with the electrochemical reactions in the CV results. Figure 2e shows the rate performances after cycling at various current densities from 200 to 2000 mA g–1. Even at 2000 mA g–1, the capacities of the electrodes are still higher than the theoretical capacity of commercial graphite. Figure 2f shows the cycling performance at 200 mA g–1. After 200 cycles, the Sn2(dobpdc) anode achieves a capacity of 1018 mAh g–1, whereas Sn2(dobdc) maintains a capacity of 731 mAh g–1 at 200 mA g–1. The good cycling performances at high currents are also achieved. At 500 mA g–1 for 600 cycles, the Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) electrodes exhibit stable capacities over 400 and 650 mAh g–1, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Due to the isoreticular structures of Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc), the distinct lithium storage capacities between Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) could be derived from the expansion of the organic linkers. Apart from the alloying reactions of the Sn centers, which are almost the same in these two MOFs, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to evaluate the lithium storage capability of organic ligands. Based on the calculated Li uptake numbers of 8 and 12 for the organic ligands (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5), Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) are able to deliver theoretical capacities of 1044 and 1099 mAh g–1, respectively, with contributions from the Sn centers. The practical capacities of the Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) are 731 and 1018 mAh g–1 at 200 mA g–1, corresponding to utilization efficiencies of 70.0% and 92.6%, respectively. The high utilization efficiency of Sn2(dobpdc) is attributed to the increased conjugation of the organic ligand, which can realize the full electrochemical activity of both redox active groups and aromatic rings.

To reveal the difference in the rate performances of Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc), which mainly depends on the kinetics during the lithium storage processes, electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) and additional CV characterization were performed. The activation energies of these two Sn-based MOFs for lithium storage were estimated by the EIS data at different temperatures (Fig. 3a–c). In general, a semicircle at high and medium frequencies and a straight line at low frequencies are related to the charge transfer resistance (Rct) and the Li+ diffusion resistance (Rw), respectively. The value of Rct decreases as the temperature increases because electrochemical kinetic reactions can easily occur at high temperatures37. Sn2(dobpdc) exhibits a smaller Rct and a lower Rw than Sn2(dobdc), indicating that Sn2(dobpdc) undergoes faster reaction kinetics (Fig. 3a, b). Based on the EIS data at different temperatures, the apparent activation energy (Ea) can be calculated by i0 = RT/nFRct and i0 = Aexp(−Ea/RT)37,38, where i0 is the exchange current, A is the temperature-independent coefficient, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, n is the number of transferred electrons, and F is the Faraday constant. The Ea value is obtained by the slope of the ln(T/Rct) versus 1000/T plot fitted by the Arrhenius equation (Fig. 3c). The calculated Ea values are 62.68 kJ mol–1 and 53.46 kJ mol–1 for Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc), respectively. The relatively low Ea of Sn2(dobpdc) indicates an easier diffusion process for lithium intercalation than that in Sn2(dobdc). Figure 3d displays the EIS of these two Sn-MOFs after 200 cycles. The Sn2(dobpdc) electrode exhibited a lower Rct of 71.8 Ω in comparison to the Rct of 175.4 Ω for the Sn2(dobdc) electrode, in accordance with the faster reaction kinetics of Sn2(dobpdc). Furthermore, the CV tests at different scan rates (0.1–0.4 mV s–1) with a voltage range from 0.01 to 3.0 V were also carried out to probe the kinetic origin of the lithium storage in the Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 11a, b). The relationship between the log (peak current) and log (scan rate) from the CV curves suggests that a combination of diffusion-controlled and surface-controlled processes contribute to the electrochemical reactions in the Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 11c, d)10. Quantitative analyses demonstrate that the percentage of capacitive contribution of the Sn2(dobpdc) electrode is higher than that of the Sn2(dobdc) electrode (Supplementary Fig. 11e, f), confirming that the Sn2(dobpdc) electrode has favorable charge transfer kinetics and good rate capability. Furthermore, the diffusion coefficients of Li+ in Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) were calculated by the galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) (Supplementary Fig. 12), demonstrating that Sn2(dobpdc) has a higher Li+ diffusion coefficient than Sn2(dobdc). The enhanced kinetics of Sn2(dobpdc) are from the high surface area and pore volume of the expanded framework (Supplementary Fig. 13). Therefore, the expanded organic ligand can not only enhance π-aromatic conjugation but also improve the contact area between the electrode and electrolyte, resulting in a high utilization of active sites for a high capacity (Fig. 2f) and fast kinetics for lithium storage (Fig. 2e).

Lithium storage mechanism

To determine the lithium storage mechanism of these Sn-based MOFs, in situ and ex situ characterizations were performed to analyze these Sn-MOF-based electrodes during lithiation and delithiation processes (Figs. 4–6, Supplementary Figs. 14–24). Supplementary Fig. 14a and Fig. 4a are the discharge–charge curves for Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) at 50 mA g−1 during the first cycle, respectively, corresponding to the in situ states for the PXRD measurements, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 14b and Fig. 4b, indicating that the crystallinities of Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) decrease during the first lithiation process. No obvious PXRD peaks are observed after the second lithiation and delithiation processes, revealing that both of them lose the long-range ordered structure and become amorphous upon cycling (Supplementary Fig. 15). Ex situ FTIR spectra were measured to further study the formation of the amorphous MOFs during the first cycle (Supplementary Fig. 16). The selected states of the Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) electrodes at 100 mA g–1 are marked in Supplementary Fig. 16a, d. Taking the case of Sn2(dobpdc), when the potential drops to 1.0 V for a specific capacity of approximately 90 mAh g–1, the corresponding FTIR spectra at the a and b states are congruent with the initial states. The formation of SEI layer on the electrode surface influences the FTIR analysis after being discharged to 0.7 V in the first cycle (Supplementary Fig. 16f)39. Despite the influence of SEI layer, the circled peaks at the fully charged states are similar to those of the pristine electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 16c, f), indicating the structural recovery of the electrode materials. To exclude the influence of SEI layer, Sn 3d, O 1s and C 1s XPS spectra were measured on the electrode materials after argon ion beam sputter etching for 2 min (Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18). The reversible changes of the Sn 3d, O 1s and C 1s XPS peaks indicate the recovery of the coordination structure (Please see detailed discussions in Supplementary Notes after Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18). The amorphization during the first discharge process could endow these active materials with an elastic strain capability to accommodate the volume variation from the alloying reaction of Sn with lithium, which is consistent with the excellent cycling performances of Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) (Fig. 2f). In addition, due to the locally remaining coordination structure, these amorphized samples with crystal defects demonstrate a redox active performance that is superior to that of their crystalline counterparts (Fig. 4a). The amorphous Sn-MOFs have similar characters to quasi-MOFs and glassy MOFs in terms of the absence of Bragg peaks in PXRD patterns. The lack of long-range ordered structure could expose more active sites40,41,42.

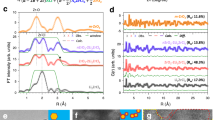

a Discharge–charge profile of Sn2(dobpdc) at 50 mA g−1 for the first cycle in the in situ cell. Inset: schematic diagram of the transformation of Sn2(dobpdc) from crystalline to amorphous states. b In situ PXRD of Sn2(dobpdc) collected at different discharge–charge states corresponding to the process in 4a.

a Load curve during the second discharge–charge process at 50 mA g−1 with marked states for quasi-in situ XAFS tests. b Schematic cross-section of a coin-type battery for the quasi-in situ XAFS test. c, d Sn K-edge XANES during the discharge–charge process. The insets display the corresponding Sn K-edge k3-weighted FT-EXAFS spectra. e, f Sn K-edge k3-weighted FT-EXAFS spectra fitting in R space for selected states during the discharge–charge process. The black lines in c-f correspond to the XAFS spectra of the pristine electrode. g CNs of near neighbors around Sn atoms at different states in the quasi-in situ battery.

To study the valence state and local coordination structure evolution around Sn centers in the amorphous materials during cycling, quasi-in situ XAFS spectra were measured corresponding to the marked states, as shown in Fig. 5a, by which X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS)43 could provide fundamental information about the valence state and local coordination structure of the Sn2(dobpdc) electrode (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20), respectively. The XAFS spectra of the pristine Sn2(dobpdc) electrode confirmed the bivalent state of Sn2+ and Sn–O coordination of 2.13 Å with a coordination number (CN) of 3.7±0.7 (Supplementary Fig. 19 and Table 6), which is consistent with the crystal data of Sn2(dobpdc) (Supplementary Table 3). The quasi-in situ tests were performed on a treated CR2032 coin battery (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 21). During the discharge process (Fig. 5c), the amplitude of the white line in the XANES profile of the Sn2(dobpdc) electrode slowly decreases as a result of the reduction of Sn centers. During the charge process, the intensity of the main XANES peak of the Sn2(dobpdc) electrode gradually increases back to the original state (Fig. 5d). The insets in Fig. 5c, d are the corresponding Fourier transformation-EXAFS (FT-EXAFS) spectra, which could reveal the local coordination structure change around the Sn centers. Upon discharging, the intensity of the Sn–O bonds continuously decreases due to the insertion of lithium into organic ligands and the alloying reaction of lithium with Sn centers. Moreover, a new peak emerges at approximately 3.0 Å because of the formation of Sn–Sn bonds from the alloying reaction. The Sn–O bonds recover, and the Sn–Sn bonds disappear after fully charging, indicating reversible reactions around the Sn centers. To determine the coordination environment around the Sn center, phase-corrected FT-EXAFS of selected states were fitted in R space. As shown in Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 20, the Sn–O coordination interactions are broken with a decrease in CN of the Sn–O coordination shell from 3.7 ± 0.7 to 2.8 ± 0.5 after being discharged to 1.5 V, corresponding to partial disengagement of the organic ligands from the Sn centers due to lithiation of the organic ligands. Upon becoming fully discharged, a new peak at 2.92 Å is observed and is ascribed to the Sn–Sn shell from the LixSn alloy with a CN of 6.3 ± 1.2, confirming the alloying reaction. During the charging process, the CN of the Sn–Sn shell decreases from 6.3 ± 1.2 to 2.5 ± 0.6 after charging to 0.6 V because of the dealloying reaction of LixSn; after charging to 3.0 V, the Sn–Sn interaction disappears, and the Sn–O shell with a CN of 2.7 ± 0.4 reappears (Fig. 5f) and does not fully return to the original state with a CN of 4 due to the formation of a SEI layer during the initial two cycles (Please see detailed discussions in Supplementary Notes after Supplementary Table 6). XAFS analyses of the lithiated and delithiated electrodes after 5 cycles were conducted to further reveal the reversibility of the lithium storage mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 20). After five cycles, the XANES curve of the Sn2(dobpdc) electrode in the fully charged state matches well with that of the pristine state, demonstrating the reversible valence state change of the Sn center (Supplementary Fig. 20a). Based on the FT-EXAFS spectra and fitting results (Supplementary Fig. 20b, c and Fig. 5g), a weak Sn–O shell at 2.15 Å with a CN of 1.8 ± 0.3 can be observed in the discharged electrode after 5 cycles, demonstrating the presence of the Sn–O interaction between the LixSn alloy and the organic ligands. In the charged electrode after 5 cycles, the peak at 2.15 Å from the Sn–O shell with a CN of 3.5 ± 0.6 is very close to that of the pristine electrode (3.7 ± 0.7), confirming the reconstruction of the coordination environment of Sn. These results demonstrate the reversible transformation between the formation of Sn–O and Sn–Sn bonds during the electrochemical reaction in the Sn2(dobpdc) electrode.

To verify the intermediates that form during the alloying reaction around Sn centers, HRTEM analysis of Sn2(dobpdc) was performed during the second cycle (Supplementary Fig. 22). Since these MOFs are easily damaged by the electron beam, the lattice fringe information disappears for the pristine states (Supplementary Fig. 23). During the discharge process, the interplanar distances of 0.291, 0.282 and 0.198 nm are consistent with the (200) and (101) lattice planes in Sn and the (933) lattice planes in Li4.4Sn, respectively, confirming the formation of Sn and Li4.4Sn. These results are consistent with the Li+ ions inserted into the active materials with a reduction of Sn(II) to Sn(0) followed by the alloying reaction (Supplementary Fig. 22a). During the charging process, the appearance of the interplanar distance of 0.294 nm for the (200) lattice planes of Sn metal confirms the dealloying reaction of Li4.4Sn; after becoming fully charged, the amorphous Sn2(dobpdc) recovers with the absence of lattice fringe information (Supplementary Fig. 22b). These HRTEM results confirm the reversible alloying and dealloying of Sn with Li+ ions.

Based on the above analyses, the overall lithiation and delithiation reaction processes of Sn2(dobpdc) can be described, as shown in Fig. 6. Although the amorphization of Sn2(dobpdc) occurs during the first cycle, the coordination interaction between Sn centers and organic ligands could be maintained to sustain stable and long-term lithium storage behavior. In the following processes, the electrochemical reactions in the amorphous Sn2(dobpdc) phase are related to two successively reversible processes: the redox reaction of organic ligands and the alloying reaction of Sn centers. During the discharge process, a capacity of ~210 mAh g–1 over the voltage range from 3.0 to 0.5 V is related to Li+ insertion into organic ligands with a reduction of the Sn centers; after becoming fully discharged, the superlithiation of organic ligands and alloying reaction of Sn could provide a capacity of ~890 mAh g–1 for an uptake of approximately 17-Li+. During the charge process, the dealloying of Li4.4Sn to Sn and the extraction of Li+ from organic ligands successively take place, resulting in the reversion of amorphous Sn2(dobpdc) for a reversible specific capacity of ~1100 mAh g–1. Taking advantage of the multiple lithium storage sites and the reversible formation of the coordination bonds, this Sn-based MOF exhibits a high utilization of active sites and fast kinetics for the merits of high reversible capacity at high rate and excellent cycling stability.

We used ex situ FTIR and SEM to study the composition and morphology changes of the electrodes after long-term cycling (Supplementary Figs. 24 and 25). In the FTIR spectra, after the first, fifth and tenth cycles after becoming fully recharged to 3.0 V, the peaks are not entirely consistent with those of the pristine electrodes because of the lithiation and amorphization of the materials, but the FTIR spectra of the fully charged states after five and ten cycles are consistent with that of the first recharged electrode, indicating the recovery of the coordination units. SEM observations show that the morphologies of the active materials are well retained after long-term cycling (Supplementary Fig. 25), accounting for their stable lithium storage performance during cycling.

Discussion

In comparison with the lithium storage properties and synthetic methods of reported Sn-based nanomaterials and other typical anode materials (Supplementary Table 7), these two well-designed Sn-based MOFs with uniformly confined Sn centers and organic ligands synthesized through a simple solution method achieve a high reversible capacity and long-term cycling stability, verifying the effectiveness of the coordination chemistry strategy for lithium storage. Notably, the reversible formation of the Sn–O–C bond could commendably restrain pulverization and particle aggregation issues to afford stable cycling performance; moreover, the tin alloying element and lithium active organic ligand provide multiple lithium storage sites, thus ensuring high capacity. The rate performances of the Sn-based MOFs are moderate due to the relatively poor electronic conductivity for coordination compounds, but our results have demonstrated that this issue could be solved by a rational ligand design via the extension of π-conjugated functional groups.

In summary, two Sn-based MOFs were designed, and their application in lithium storage was investigated in detail. The ligand extension of these isoreticular Sn-MOFs resulted in enhanced specific capacities up to 1018 mAh g–1 with high rate performance and long-term cycling stability, which had the best lithium storage property among reported coordination compounds. Detailed mechanism analyses for both atomic accuracy and at the nanoscale were performed by a systematic analysis, including XAFS, to reveal a new insight into coordination compounds for lithium storage beyond the previous understanding. The multiple lithium storage sites from the metal centers and organic ligands, the enhanced π-conjugation from the organic ligands, and most importantly, the reversible formation of the coordination bonds during the lithiation and delithiation processes jointly endow the Sn-MOFs with highly reversible capacity, good rate capability and stable cycling performance. The molecular level of the dispersibility of the Sn centers coordinated with organic redox ligands in the framework effectively suppress pulverization and particle aggregation of Sn particles to guarantee capacity stability for long-term cycling performance. Our findings provide new insights into the mechanism of coordination compounds for lithium storage, which benefits the design and construction of high-performance electrode materials.

Methods

Preparation of the Sn2(dobdc)

NaOH (0.9 mmol, 36 mg) and 2,5-dioxido-1,4-benzenedicarboxylate acid (0.3 mmol, 59.4 mg) were dissolved in 10 mL deionized H2O and subsequently poured into a 10 mL aqueous solution of SnSO4 (1.2 mmol, 257 mg). The mixture was heated to 353 K for 72 h. Dark yellow crystals were obtained by filtration, washed several times with water and ethanol, and then fully desolvated by heating under dynamic vacuum at 523 K for 24 h (yields 66% based on SnSO4). Elemental analysis for Sn2C8O6H2 yielded a calcd (%) for C of 22.27 and H of 0.47; the found (%) for C was 22.24, and for H, it was 0.52.

Preparation of the Sn2(dobpdc)

Similar to the synthetic procedure of Sn2(dobdc), 2,5-dioxido-1,4-benzenedicarboxylate acid was replaced with 4,4’-dioxidobiphenyl-3,3’-dicarboxylate acid. Elemental analysis for Sn2C14O6H6 yielded a calcd (%) for C of 33.13 and H of 1.19; the found (%) for C was 33.54, and for H, it was 1.45.

Characterization

The PXRD measurements were performed on a Rigaku Smartlab SE instrument. Elemental analysis was conducted with a Vario EL cube elemental analyzer. Thermal gravimetric analysis was conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere using a METTER TOLEDO TGA 2-Thermogravimetric Analyzer. The FTIR spectra were acquired using a Bruker Alpha ATR-FTIR instrument. The morphologies were observed by field-emission SEM (JEOL, JSM7500F) and HRTEM (Philips Tecnai FEI, 200 kV). XPS spectra were conducted on a Kratos AXIS Ultra DLD spectrometer (UK) with an Al Kα X-ray source.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were conducted in CR2032 coin cells with Sn-MOFs as the active material in the working electrode, metallic lithium foil as the counter electrode, Celgard 2300 as the separator and 1 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate (EC) and diethylcarbonate (DEC) (1:1 v/v) as the electrolyte. The dosage of electrolyte in each cell is 30 μL. All the assembly processes for the coin cells were completed in an Ar-filled glovebox. To prepare the working electrode, 70 wt% Sn-MOF, 20 wt% Ketjen black (KB) and 10 wt% polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) were mixed using N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) as the solvent. Then, the slurries were coated on Cu foils and dried at 80 °C overnight in a vacuum. The thickness of the electrode is about 15 μm on the Cu foil (Supplementary Fig. 26). The loading amount of Sn-MOF is 1.3–1.5 mg cm–2. Galvanostatic discharge–charge experiments were measured on a LANHE-CT2001A test system (Wuhan, China) at room temperature over a voltage range from 0.01 to 3.0 V at different current densities. The CV and EIS were conducted using an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660E). The GITT was conducted at 30 mA g–1 for 20 min followed by a rest time of 1 h.

Quasi-in situ XAFS measurements

The XAFS spectra at the Sn K (E0 = 29200 eV) edge were obtained at the BL14W1 beamline in the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) that was operated at 3.5 GeV under “top-up” mode with a constant current of 240 mA. The home-made open-hole batteries with ~2 mg cm–2 Sn-MOFs were treated to specific voltage states on LAND-CT2001A battery-testing instruments and then moved to the analysis chamber for further XAFS analysis. The XAFS data were recorded under fluorescence mode with a Lytle ion chamber. The energy was calibrated according to the absorption edge of a pure Sn foil. Athena and Artemis codes were used to extract the data and fit the profiles. For the XANES, the experimental absorption coefficients as a function of the energy μ(E) were processed by background subtraction and normalization procedures and reported as “normalized absorption” with E0 = 29200 eV for all the measured samples and a Sn foil/SnO/SnO2 standard. For the EXAFS, the data that underwent FT in R space were analyzed by applying the first-shell approximate and metallic Sn model for Sn-O and Sn-Sn contributions. The passive electron factors, S02, were determined by fitting the experimental data on Sn foils and fixing the CN of Sn-Sn to be the theoretical value from the structural model, and then fixed for further analysis of the measured samples. The parameters describing the electronic properties (e.g., correction to the photoelectron energy origin, E0) and local structure environment, including the CN, bond distance (R) and Debye-Waller factor around the absorbing atoms, were allowed to vary during the fitting process. The fitted ranges for k and R spaces were selected to be k = 3−11 Å−1 with R = 1.0−3.5 Å (k3 weighted).

DFT calculations

Geometry optimization and frequency analysis of the species were performed by the B3LYP functional44 and 6-311 + G(d,p) basis set. All calculations were performed with Gaussian 1645. Computed structures were illustrated using CYLView46.

Single-crystal X-ray structure determination

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were obtained at 120 K via an Oxford Cryo stream system on a Supernova X-ray diffractometer with graphite monochromatic Mo Kα radiation (λ = 71.073 pm). The structures were solved with direct methods and refined by least-squares methods on F2 using SHELXS and SHELXL, respectively, in the Olex2 software packages47. All hydrogen atoms were located and refined isotropically48,49. The crystallographic data are provided in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Data availability

All the data of this study are available. The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. The X-ray crystallographic data for Sn2(dobdc) and Sn2(dobpdc) have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2007076 and 2007077, respectively. These data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

References

Armand, M. & Tarascon, J. M. Building better batteries. Nature 451, 652–657 (2008).

Dunn, B., Kamath, H. & Tarascon, J. M. Electrical energy storage for the grid: a battery of choices. Science 334, 928–935 (2011).

Whittingham, M. S. Quest for nonaqueous multivalent secondary batteries: magnesium and beyond. Chem. Rev. 114, 11414–11443 (2014).

Mai, L., Yan, M. & Zhao, Y. Track batteries degrading in real time. Nature 546, 469–470 (2017).

Idota, Y., Kubota, T., Matsufuji, A., Maekawa, Y. & Miyasaka, T. A high-capacity lithium-ion storage material. Science 276, 1395–1397 (1997).

Schmuch, R., Wagner, R., Hörpel, G., Placke, T. & Winter, M. Performance and cost of materials for lithium-based rechargeable automotive batteries. Nat. Energy 3, 267–278 (2018).

Li, Z., Ding, J. & Mitlin, D. Tin and tin compounds for sodium ion battery anodes: phase transformations and performance. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 1657–1665 (2015).

Ying, H. & Han, W. Q. Metallic Sn-based anode materials: application in high-performance lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 4, 1700298 (2017).

Yu, Y., Gu, L., Zhu, C., Van Aken, P. A. & Maier, J. Tin nanoparticles encapsulated in porous multichannel carbon microtubes: preparation by single-nozzle electrospinning and application as anode material for high-performance Li-based batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 15984–15985 (2009).

Chao, D. et al. Array of nanosheets render ultrafast and high-capacity Na-ion storage by tunable pseudocapacitance. Nat. Commun. 7, 12122 (2016).

Kim, M. G., Sim, S. & Cho, J. Novel core-shell Sn-Cu anodes for lithium rechargeable batteries prepared by a redox-transmetalation reaction. Adv. Mater. 22, 5154–5158 (2010).

McDowell, M. T., Lee, S. W., Nix, W. D. & Cui, Y. 25th anniversary article: understanding the lithiation of silicon and other alloying anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 25, 4966–4985 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. Ultrahigh and durable volumetric lithium/sodium storage enabled by a highly dense graphene-encapsulated nitrogen-doped carbon@Sn compact monolith. Nano Lett. 20, 2034–2046 (2020).

Xu, Y., Zhu, Y., Liu, Y. & Wang, C. Electrochemical performance of porous carbon/Tin composite anodes for sodium-ion and lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 128–133 (2013).

Liu, Y., Zhang, N., Jiao, L., Tao, Z. & Chen, J. Ultrasmall Sn nanoparticles embedded in carbon as high-performance anode for sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 214–220 (2015).

Zhang, H., Shi, T., Wetzel, D. J., Nuzzo, R. G. & Braun, P. V. 3D scaffolded nickel-tin Li-ion anodes with enhanced cyclability. Adv. Mater. 28, 742–747 (2016).

Youn, D. H., Heller, A. & Mullins, C. B. Simple synthesis of nanostructured Sn/nitrogen-doped carbon composite using nitrilotriacetic acid as lithium ion battery anode. Chem. Mater. 28, 1343–1347 (2016).

Wu, C., Maier, J. & Yu, Y. Sn-based nanoparticles encapsulated in a porous 3D graphene network: advanced anodes for high-rate and long life Li-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 3488–3496 (2015).

Liu, J., Wen, Y., van Aken, P. A., Maier, J. & Yu, Y. Facile synthesis of highly porous Ni-Sn intermetallic microcages with excellent electrochemical performance for lithium and sodium storage. Nano. Lett. 14, 6387–6392 (2014).

Mo, R. et al. Tin-graphene tubes as anodes for lithium-ion batteries with high volumetric and gravimetric energy densities. Nat. Commun. 11, 1374 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Circumventing huge volume strain in alloy anodes of lithium batteries. Nat. Commun. 11, 1584 (2020).

Rosi, N. L. et al. Hydrogen storage in microporous metal-organic frameworks. Science 300, 1127–1129 (2003).

Zhou, H. C., Long, J. R. & Yaghi, O. M. Introduction to metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 112, 673–674 (2012).

Burtch, N. C., Jasuja, H. & Walton, K. S. Water stability and adsorption in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 114, 10575–10612 (2014).

Liang, Z., Qu, C., Guo, W., Zou, R. & Xu, Q. Pristine metal-organic frameworks and their composites for energy storage and conversion. Adv. Mater. 30, 1702891 (2018).

Zhou, J. & Wang, B. Emerging crystalline porous materials as a multifunctional platform for electrochemical energy storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 6927–6945 (2017).

Zhang, L., Liu, H., Shi, W. & Cheng, P. Synthesis strategies and potential applications of metal-organic frameworks for electrode materials for rechargeable lithium ion batteries. Coord. Chem. Rev. 388, 293–309 (2019).

Liu, J., Xie, D., Shi, W. & Cheng, P. Coordination compounds in lithium storage and lithium-ion transport. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 1624–1642 (2020).

Xiao, X., Zou, L., Pang, H. & Xu, Q. Synthesis of micro/nanoscaled metal-organic frameworks and their direct electrochemical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 301–331 (2020).

Kong, L., Zhong, M., Shuang, W., Xu, Y. & Bu, X. H. Electrochemically active sites inside crystalline porous materials for energy storage and conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 2378–2407 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Quinone electrode materials for rechargeable lithium/sodium ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1700278 (2017).

Liu, J. et al. Facile construction of two-dimensional coordination polymers with a well-designed redox-active organic linker for improved lithium ion battery performance. Sci. China Chem. 62, 602–608 (2019).

Wang, X., Liu, L., Makarenko, T. & Jacobson, A. J. Acentric and centric interpenetrations of an anionic framework mediated by cation sizes: the alkali-metal tin(II) benzenedicarboxylates A2Sn2(bdc)3(H2O)x(A = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs). Cryst. Growth Des. 10, 1960–1965 (2010).

Eubank, J. F. et al. The next chapter in MOF pillaring strategies: trigonal heterofunctional ligands to access targeted high-connected three dimensional nets, isoreticular platforms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 17532–17535 (2011).

Lin, D. et al. Fast galvanic lithium corrosion involving a Kirkendall-type mechanism. Nat. Chem. 11, 382–389 (2019).

Li, G. et al. A coordination chemistry approach for lithium-ion batteries: the coexistence of metal and ligand redox activities in a one-dimensional metal-organic material. Inorg. Chem. 55, 4935–4940 (2016).

Ma, H., Zhang, S., Ji, W., Tao, Z. & Chen, J. r-CuV2O6 nanowires: hydrothermal synthesis and primary lithium battery application. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5361–5367 (2008).

Hu, Z. et al. Pyrite FeS2 for high-rate and long-life rechargeable sodium batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 1309–1316 (2015).

Qian, J. et al. High rate and stable cycling of lithium metal anode. Nat. Commun. 6, 6362 (2015).

Bennett, T. D. & Cheetham, A. K. Amorphous metal-organic frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 1555–1562 (2014).

Tsumori, N. et al. Quasi-MOF: exposing inorganic nodes to guest metal nanoparticles for drastically enhanced catalytic activity. Chem 4, 845–856 (2018).

Chen, W. et al. Glass formation of a coordination polymer crystal for enhanced proton conductivity and material flexibility. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 5195–5200 (2016).

Ding, Y., Li, Z. F., Timofeeva, E. V. & Segre, C. U. In situ EXAFS-derived mechanism of highly reversible tin phosphide/graphite composite anode for Li-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702134 (2018).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phy. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16, revision A.03, (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2016).

Legault, C. Y. CYLview, 1.0b; Universitéde Sherbrooke: Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada, http://www.cylview.org, (2009).

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXTL NT Version 5.1, Program for solution and refinement of crystal structures. (University of Göttingen: Germany, 1997).

Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta cryst. 64, 112–122 (2008).

Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K. & Puschmann, H. J. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 42, 339–342 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant refs: 21622105, 21931004 and 21773288), the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (grant ref: 18JCJQJC47200) and the Ministry of Education of China (grant ref: B12015). This work was supported by Shanghai Large Scientific Facilities Center and National Key Basic Research Program of China (2017YFA0403402). W. S. gratefully acknowledges the support of the Royal Society through a Newton Advanced Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and W.S. conceived the research. J.L. and D.X. performed the synthesis, structure analysis and electrochemical studies. X.X performed the DFT calculations. L.J and R.S. performed the XAFS analysis. J.L., W.S., R.S. and P.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Yunfeng Lu, Ruqiang Zou and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Xie, D., Xu, X. et al. Reversible formation of coordination bonds in Sn-based metal-organic frameworks for high-performance lithium storage. Nat Commun 12, 3131 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23335-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23335-1

This article is cited by

-

Electrochemical reconstruction: a new perspective on Sn metal–organic complex microbelts as robust anode for lithium storage

Rare Metals (2024)

-

High-sensitivity formaldehyde gas sensor based on Ce-doped urchin-like SnO2 nanowires derived from calcination of Sn-MOFs

Frontiers of Materials Science (2024)

-

Atomic Mo-NC-sourced robust MoO3/C nanocomposite for high-performance Li-ion storage

Science China Materials (2023)

-

Roadmap of amorphous metal-organic framework for electrochemical energy conversion and storage

Nano Research (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.