Abstract

Understanding Earth’s response to climate forcing in the geological past is essential to reliably predict future climate change. The reconstruction of continental climates, however, is hampered by the scarcity of universally applicable temperature proxies. Here, we show that heterocyte glycolipids (HGs) of diazotrophic heterocytous cyanobacteria occur ubiquitously in equatorial East African lakes as well as polar to tropical freshwater environments. The relative abundance of HG26 diols and keto-ols, quantified by the heterocyte diol index (HDI26), is significantly correlated with surface water temperature (SWT). The first application of the HDI26 to a ~37,000 year-long sediment record from Lake Tanganyika provides evidence for a ~4.1 °C warming in tropical East Africa from the last glacial to the beginning of the industrial period. Given the worldwide distribution of HGs in lake sediments, the HDI26 may allow reconstructing SWT variations in polar to tropical freshwater environments and thereby quantifying past continental climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earth is currently experiencing major alterations of its climate including an increase in surface temperatures not observed in the historic past1. Climate models consistently forecast that future global temperatures will increase but they disagree in terms of magnitude, which results in particularly large uncertainties in estimating the extent of future climate change2. A means to better constrain future climate change is to study past climate states and transitions using proxy records obtained from climate archives. Organic temperature proxies (UK′37, TEX86, LDI)3,4,5 have proved to be indispensable in this context. These tools are frequently employed in marine sediment sequences to reconstruct past sea surface temperatures and have been used to establish high-resolution palaeotemperature records from all parts of the oceans5,6,7 and in sediments dating back to the Early Jurassic (~200 Ma)8. As such, organic temperature proxies have significantly broadened our knowledge on Earth’s long-term climate evolution over geological timescales9,10 as well as during abrupt climate change events11.

Lakes are outstanding archives of past climate change, as they contain continuous, high-resolution sediment records, are widespread, and highly responsive to climate forcing. Obtaining climate-relevant data from lacustrine sediments using lipid palaeothermometers, however, is not always straightforward. The TEX86 is only applicable in some large lakes12 and long-chain alkenones (needed for the calculation of the UK37) are generally absent from low-latitude lake sediments13. More recently, the MBT′5Me was proposed as a tool to reconstruct past terrestrial temperature14 but in lakes, its application is complicated due to mixed contributions of aquatic and terrestrially derived branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (GDGTs) with contrasting temperature adaptations15. Additional temperature proxies to extract the climate signal stored in lake sediments are thus needed to generate accurate reconstructions of past continental climate change that allow testing climate model hindcasts.

Heterocyte glycolipids (HGs) have recently been proposed as novel tools in reconstructing surface water temperatures (SWTs) in freshwater environments16. These compounds are exclusively found in the heterocyte cell envelope of N2-fixing heterocytous cyanobacteria17,18,19, which are common components of the phytoplankton community in freshwater environments worldwide20. HGs consist of sugar moieties bound to even-numbered alkyl side chains with 26–32 carbon atoms containing either hydroxyl (diols, triols) or additional ketone groups (keto-ols, keto-diols; see Supplementary Fig. 1)17. The distribution of HGs has been shown previously to vary between different cyanobacterial orders and families17,18, facilitating studies of community compositions of cyanobacteria in freshwater environments. In addition, the relative proportion of HGs systematically varies as a function of growth temperature, with HG26 diols increasing and HG26 keto-ols decreasing in abundance with increasing growth temperature in cultured cyanobacteria21. This pattern has been interpreted as a mechanism to constrain the diffusion of atmospheric gases into the heterocyte to protect the oxygen-sensitive enzyme nitrogenase and thus allow for biological N2 fixation22. Very similar changes in the abundance of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols have been observed in surface waters of Lake Schreventeich (northern Germany). These changes were quantitatively expressed by the HDI26 (heterocyte diol index of 26 carbon atoms), which tracked seasonal changes in SWT and evidenced that HDI26 values in lake surface sediments capture a late summer temperature signal, during which maximum in-lake productivity was observed16. Significant differences in the composition of HGs have also been noted between polar microbial mats (dominated by HG keto-ols and keto-diols) and subtropical freshwater environments (dominated by HG diols and triols)19. Although there is compelling evidence that ambient temperature exerts a major control on the relative abundance of individual HGs, highlighting their potential in palaeoclimate investigations, no study has systematically examined HG distribution patterns in lakes of varying temperature regimes. This severely limits our understanding of the potential of HGs for studying past SWT in freshwater environments and reconstructing continental climate change.

Here, we investigate the spatial variability of HGs (in particular HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols) in surface sediments of 46 tropical East African lakes in comparison to eight other globally distributed lakes and ponds to resolve the relationship between HDI26 and environmental (SWT, pH, oxygen concentration), physical (lake depth, size, surface area) as well as biological parameters (productivity, community composition of cyanobacteria). In addition, the HDI26 was for the first time applied to a sediment record from Lake Tanganyika (Tanzania), which allowed a comprehensive study of temperature change in tropical East Africa during the past ~37,000 years. Our data demonstrate the potential of HGs to reconstruct past lacustrine SWT and thereby act as a tool for the quantitative assessment of continental climate change.

Results

HG distributions in East African lake surface sediments

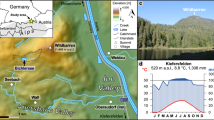

We analyzed HG distribution patterns in surface sediments of 46 tropical East African lakes located on an altitudinal transect from 615 to 4504 m above sea level (masl; Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1). The lakes show large physical, chemical, hydrological, and environmental gradients with maximum water depths differing between 0.3 and 1470 m, surface water pH varying from 3.8 to 9.8 and mean annual SWT ranging from 5.7 to 27.9 °C (Supplementary Table 1)23,24. Fourteen different HGs, ranging in chain length from 26 to 32 carbon atoms and each consisting of one to four structural isomers, were identified in the East African lake surface sediments (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 2). Distribution patterns of HGs significantly varied along the altitudinal gradient. Hierarchical clustering of HGs and comparison with HG signatures found in cultured cyanobacteria17,18,19,25 allowed the definition of three biozones, each characterized by distinct HG distributions and cyanobacterial communities as well as altitudinal ranges (Fig. 3). High relative abundances of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols, as well as HG28 diols and HG28 keto-ols, are specific for low-elevation lakes of Biozone 1 (615 to ~1550 masl). Both types of HGs have been reported previously from non-branching cyanobacteria belonging to the Nostocaceae, such as Anabaena spp. and Anabaenopsis spp.18, which are common components of the phytoplankton community in equatorial African lakes at low altitudes26,27. Mid-elevation lakes of Biozone 2 (~1550 to ~4300 masl) are characterized by a higher diversity of HGs. Increased fractional abundances of HG28 triols and HG28 keto-diols as well as of HG30 triols and HG30 keto-diols suggest a higher contribution of mat-forming heterocytous cyanobacteria belonging to the Rivulariaceae (e.g. Calothrix spp.)18,25 and Scytonemataceae (e.g. Scytonema spp.)17,25. HG30 triols and HG30 keto-diols increase in abundance in the high-elevation lakes, which are mostly shallow and oligotrophic tarns. In these freshwater environments of Biozone 3 (>4300 masl), HG30 triols and HG30 keto-diols constitute the majority of HGs and point to a predominant contribution of Scytonemataceae. The distribution of HGs thus indicates significant altitude-driven changes in the community composition of heterocytous cyanobacteria in the East African lakes.

Orange square marks the area from which surface sediments of tropical East African lakes have been collected. This includes lakes from the Rwenzori Mountains (Uganda), Mt. Kenya (Republic of Kenya) and East African rift valley lakes that are located on an altitudinal transect from 615 to 4504 masl. Red dots = tropical Lake Towuti (Indonesia), Lake Klakah (Indonesia), and Lake Lading (Indonesia). Green dots = temperate Lake Constance (Germany) and Lake Schreventeich (Germany)16. Light blue dot = subpolar Laguna Potrok Aike (Argentina). Dark blue dot = Antarctic meltwater ponds.

Representative samples include a high-elevation Lake Hohnell (4212 masl; 7.9 °C), b mid-elevation Lake Bandasa (2938 masl; 17.2 °C), and c low-elevation Lake Tanganyika (773 masl; 25.7 °C). Insets show the distribution of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols in the respective samples. Note the increase in the relative abundance of HG26 diols compared to HG26 keto-ols with decreasing altitude and increasing lake surface water temperature as well as the concomitant increase in HDI26 values.

The distance in the similarity of HG patterns indicates that three biozones, each characterized by distinct cyanobacterial communities, exist along the altitudinal gradient. Biozone 1 comprises low-elevation lakes (615 to ~1550 masl) and shows abundant HG26 diols and HG28 diols that are specific to nostocalean cyanobacteria belonging to the genera Anabaena and Anabaenopsis17,18. Biozone 2 constitutes of mid-elevation lakes (~1550 masl to ~4300 masl). Surface sediments of these lakes contain more diverse HG distribution patterns and higher relative abundances of HG28 triols and HG30 triols. The latter are found in heterocytous cyanobacteria of the benthic mat-forming families Rivulariaceae (e.g. Calothrix spp.)18,19 and Scytonemataceae (e.g. Scytonema spp.)25. Biozone 3 (>4300 masl) includes shallow, high-elevation tarns that are characterized by abundant HG30 triols and HG30 keto-diols, which points to a predominant contribution of mat-forming heterocytous cyanobacteria of the genus Scytonema25. Note that only the summed fractional abundance of individual HGs is shown as the overall HG distribution pattern is specific for the cyanobacterial community composition. Lake abbreviations are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Numbers in brackets indicate the altitudinal position of the lake systems.

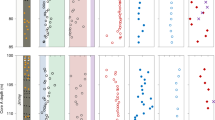

HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols, each consisting of two structural isomers, were present in all of the East African lake surface sediments (Fig. 3). The HG26 diol isomers were most abundant in the low-elevation lakes with the most dominant isomer contributing on average 0.85 ± 0.04 to the summed fractional abundance of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols. However, its abundance declined gradually along the altitudinal gradient and in lakes >4000 masl, the fractional abundance of the most dominant HG26 diol was on average 0.57 ± 0.01 (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table 3). By contrast, the most abundant isomer of the HG26 keto-ols contributed with 0.04 ± 0.01 only minor to the summed fractional abundance of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols in the low-elevation lakes. It increased, however, gradually in abundance with altitude to a maximum of 0.33 ± 0.05 of the summed fractional abundance of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols in the high-elevation lakes (Fig. 4). The HDI26 (heterocyte diol index of 26 carbon atoms = HG26 diol/[HG26 diol + HG26 keto-ol]), a means to quantitatively express changes in the relative abundances of HG26 diols compared to HG26 keto-ols16, varied from 0.59 in high-elevation Lake Hohnell (4212 masl) to 0.99 in low-elevation Lake Albert (615 masl; Supplementary Table 3).

Regression analysis demonstrates that fractional abundances (FA) of (a) HG26 keto-ols are negatively and that of (b) HG26 diols are positively correlated with surface water temperature (SWT). The most dominant structural isomers of both component classes in the East African (indicated in gray) and polar to tropical lake surface sediments showed the strongest correlation with SWT and were used for the calculation of the HDI26. Fractional abundances of HG26 keto-ols and HG26 diols found in surface sediments of polar to tropical lakes and ponds are shown for comparison and express similar compositional changes across the investigated temperature interval as observed for the East African lake sample set. Red circles and diamonds = tropical Indonesian lakes (Lake Klakah, Lake Lading, and Lake Towuti); Green circles and diamonds = temperate European lakes (Lake Constance and Lake Schreventeich16); Light blue circle and diamond = subpolar Laguna Potrok Aike; Dark blue circles and diamonds = Antarctic meltwater ponds. Error bars indicate the SD of the fractional abundances based on replicate sample analyses.

HG distributions in tropical to polar lakes and ponds

In order to assess whether HGs are found globally and whether their distribution shows significant variation between climate zones, we investigated a set of surface sediments collected from eight polar to tropical freshwater systems (Fig. 1). These lakes and ponds were selected based on the availability of direct water temperature measurements, which allowed investigating the effect of seasonality on HG distribution patterns and consequently the reconstruction of SWT. HG26 diols were abundant in the three tropical Indonesian lakes (Klakah, Lading, and Towuti). The most dominant HG26 diol isomer on average amounted to 0.89 ± 0.05 (0.01 ± 0.01 for the HG26 keto-ol) of the summed fractional abundances of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols (Supplementary Table 3). In temperate Lake Constance (southern Germany), its fractional abundance was 0.76 (0.16 for the HG26 keto-ol). A similar fractional abundance of 0.79 for the HG26 diol (0.21 for the HG26 keto-ol) has been reported previously in temperate Lake Schreventeich (northern Germany)16. The fractional abundance of the most dominant HG26 diol was 0.52 (0.27 for the HG26 keto-ol) in surface sediments of subpolar Laguna Potrok Aike, which is in a similar order of magnitude as observed in the East African high-elevation lakes with SWTs of 5–7 °C. HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols were also abundant in polar meltwater ponds of western Antarctica with fractional abundances of the most dominant HG26 diol ranging from 0.27 (0.25 for the HG26 keto-ol) in Orange Pond to 0.29 (0.24 for the HG26 keto-ol) in Conophyton Pond.

Similar to the low-altitude East African lakes, HDI26 values ranged from 0.99 to 1.00 in the warm Indonesian lakes, were intermediate with 0.78 (Lake Constance) to 0.79 (Lake Schreventeich)16 in the two temperate European lakes, but were substantially lower with 0.66 in subpolar Laguna Potrok Aike (Supplementary Table 3). In the Antarctic meltwater ponds with water temperatures close to the freezing point, HDI26 values ranged from 0.51 to 0.55.

HG distributions in tropical Lake Tanganyika

Surface sediments of Lake Tanganyika contained high fractional abundances of HG26 diols (0.87) and HG26 keto-ols (0.02), which together comprised the majority of all HGs (Fig. 2; Supplementary Tables 2 and 4). HG28 diols (0.05) and HG28 keto-ols (<0.01) occurred only in minor relative abundances. Traces of HG28 triols (0.02) and HG28 keto-diols (<0.01), as well as HG30 triols (0.04) and HG30 keto-diols (<0.01) were also detected. The most dominant HG26 diol isomer amounted to 0.90 ± 0.01 of the summed fractional abundance of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols, while the most dominant isomer of the HG26 keto-ols contributed no more than 0.01 ± 0.01 (Supplementary Table 3). A HDI26 value of 0.98 was determined for the lake surface sediment.

Subsurface sediments of Lake Tanganyika, representing the last ~37,000 years of East African climate history, were collected from sediment core NP04-KH04-4A-1K28. Fractional abundances of the most dominant HG26 diol ranged from 0.83 during the last glacial maximum (LGM) to 0.90 at present, while the fractional abundance of the predominant HG26 keto-ol varied concomitantly from 0.08 to 0.01, respectively (Supplementary Table 5). HDI26 values were as low as 0.91 during the LGM and increased to 0.98 in modern Lake Tanganyika (Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

Our biomarker data demonstrates that HGs are present in all of the studied freshwater environments. This is consistent with their presence in North American29 and European freshwater lakes16,19 as well as microbial biofilms collected from Antarctica19, Iceland30, and Svalbard31. These studies have shown that HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols are most widespread16,17,18,29, in agreement with the ubiquitous presence of cyanobacteria belonging to the Nostocaceae (such as Anabaena spp., Aphanizomenon spp., Nodularia spp.) as part of the phytoplankton community in lakes worldwide20. Both HGs were also most widespread and abundant in the East African (0.53 ± 0.25 of all HGs) as well as tropical to polar lake surface sediments and ponds (0.37 ± 0.35 of all HGs; Supplementary Table 2). Similar to previous culture studies18,21 and observations from a time series experiment16, the fractional abundances of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols showed significant changes along the altitudinal gradient of East African lakes and between lakes of different climate zones (Figs. 2–4; Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). In general, HG26 diols increased in abundance with decreasing altitude and increasing SWT as well as from polar to tropical latitudes, while HG26 keto-ols showed an opposing trend.

Bivariate correlation analysis demonstrates that changes in the fractional abundance of the most dominant HG26 diol in the East African lakes are positively correlated with SWT (r = 0.953; p < 0.0001; n = 42; Supplementary Table 6). In contrast, variations in the fractional abundance of the most dominant HG26 keto-ols show a strong negative and statistically significant correlation with SWT (r = −0.979; p < 0.0001; n = 42). Similar correlations between the fractional abundance of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols and temperature have been observed previously in cultured cyanobacteria21 and environmental samples16,19. Statistical analysis also indicates a strong positive correlation of changes in HDI26 values with SWT (r = 0.975; p < 0.0001; n = 42). In addition, the HDI26 shows significant correlations with elevation, mean annual air temperature (MAAT) and bottom water temperature (BWT; Supplementary Table 6). Significant but generally weak correlations are observed with water depth, conductivity, surface (SW pH) as well as bottom water pH (BW pH) and bottom water dissolved oxygen concentrations (BW DO; Supplementary Table 6). These parameters, however, are also all significantly correlated with SWT, suggesting a minor or only indirect influence of parameters other than temperature on the abundance of both HGs and the calculation of the HDI26. Partial correlation analysis indeed demonstrates that none of these variables (except elevation and MAAT) show a significant correlation with the abundances of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols after the effect of SWT as a control variable is removed (Supplementary Table 7). Generally low or absent correlations of HG abundances with environmental parameters, such as pH and DO, have been reported previously from lake systems16,29, providing additional evidence that SWT, either by controlling the amount of oxygen dissolved in lake water or the rate of oxygen diffusion into the heterocyte, regulates the synthesis of HGs. These structural changes in the heterocyte cell envelope likely alter the properties of the gas diffusion barrier against the entry of atmospheric gases (including O2) into the heterocyte in order to allow for optimal N2 fixation21. No correlations with lake surface area, water column conductivity, SW DO or organic matter content, and the abundance of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols or the HDI26 are observed (Supplementary Table 6).

The HDI26 employs the relative abundances of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols to infer changes in water temperature16. In the East African as well as globally distributed lakes and ponds, both components occur as two structural isomers (Supplementary Table 3). Their retention time is indistinguishable from that of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols in cultured cyanobacteria, arguing for a direct biological origin of these components and against sedimentary production via rearrangement reactions. This may suggest that there is little impact of diagenetic overprinting on the distribution pattern of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols in sediments. For the two structural modifications of the HG26 diol, the strongest correlation with SWT was noted for the most dominant early eluting isomer (r = 0.953; p < 0.0001; n = 42; Fig. 2). In the case of the two varieties of the HG26 keto-ol, a generally strong correlation with SWT was observed with the later eluting isomer (r = −0.964; p < 0.0001; n = 42), which was dominating in lakes of Biozones 2 and 3. In all lakes of Biozone 1, however, the early eluting isomer of the HG26 keto-ol was predominant (Fig. 4). Changes in the relative abundance of individual HG isomers in response to variations in growth temperature were reported previously from the thermophilic cyanobacterium Mastigocladus sp. and considered as an alternative means for fine-tuning the properties of the gas diffusion barrier by synthesizing HGs with different spatial dimensions of the sugar moiety30. This finding is corroborated by the changes in the dominance of the HG26 keto-ol isomers observed here. Taking these observations into account, the best correlation with SWT (r = −0.979; p < 0.0001; n = 42) was obtained by selecting the most abundant HG26 keto-ol isomer in each sample for the calculation of the HDI26. Our data thus provides evidence for a significant correlation between SWT and the relative abundances of HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols in the East African lake surface sediments and, together with previous culture experiments18,21, indicate that the HDI26 is primarily controlled by temperature-induced changes in the composition of the heterocyte cell envelope.

Regression analysis indicates that the HDI26 and SWT are best correlated using the following linear equation in the East African lake surface sediments: HDI26 = 0.0155 × SWT + 0.5619 (r2 = 0.95, n = 0.42; RSME = 1.8 °C; Fig. 5). Although a strong relationship between the HDI26 and SWT is evident across the dataset, some of the lakes clearly deviate from the general trend, including Eldoret Nakuru 2 (2217 masl) and Nyamswiga (1463 masl). Some of the scatter may be related to shifts in the cyanobacterial community between different biozones or be caused by multiple cyanobacterial species with different blooming periods and/or different temperature responses towards the synthesis of HGs within a lake. These effects, however, may be partially counteracted by the time-integrating nature of sediment archives. As the sedimentary HG signal represents a multi-year average, this may reduce the overall impact of interannual variability and species differences on local to regional scales and contribute to the generally strong correlation of the HDI26 with SWT observed in the East African lakes.

Note that the four high-elevation tarns of Biozone 3 (>4300 masl) are not included in the calculation of the correlation coefficiency of East African lakes (black regression line and calibration). For comparison, regression lines of SWT and HDI26 values extracted from surface sediments of tropical to polar lakes and ponds (blue regression line and calibration) as well as water column samples (purple regression line and calibration) of temperate Lake Schreventeich16 are displayed, showing regional differences in the correlation between the synthesis of heterocyte glycolipids and water temperatures. Black dots = African lakes; red triangles = tropical Indonesian lakes; green squares = temperate European lakes; open blue diamond = subpolar Laguna Potrok Aike; dark blue diamonds = Antarctic meltwater ponds; purple triangles = water column samples of Lake Schreventeich16. Error bars indicate the SD based on replicate sample analyses.

To investigate whether a similar correlation exists on a global scale, we also applied the HDI26 to surface sediments of lakes and ponds from polar to tropical climate zones. This approach resulted in the following strong linear global correlation: HDI26 = 0.0167 × SWT + 0.5041 (r2 = 0.99, n = 8; RSME = 1.7 °C; Fig. 5). Again, the most dominant HG26 diol and HG26 keto-ol isomers were used for the calculation of the HDI26 as this iteration of the proxy yielded the strongest correlation with SWT. Analysis of covariance demonstrates that the East African lake and the calibration of the globally distributed lakes have no statistically significant difference in slope (p = 0.17) but do differ in the intercepts of the regression lines (p = 0.007). Very similar offsets in HDI26 values have been observed in cultured cyanobacteria21, suggesting that on a global scale species-specific effects in geographical distinct regions may become more pronounced and changes in the cyanobacterial community may require regional calibrations for the accurate reconstruction of SWTs using the HDI26. This is also suggested by the difference in slope and intercept of the transfer function established for water column samples from Lake Schreventeich16 and those reported here (Fig. 5). Together these observations argue for additional environmental and cultures studies to further constrain the differential control of temperature on the HDI26.

Replicate analysis of selected lake surface sediments across the entire sample set revealed that the analytical accuracy with which the HDI26 can be determined is on average ± 0.002. This equals to an analytical error of ±0.2 °C. A larger uncertainty in the determination of past lake water temperatures is usually embedded in the calibration function. The root-mean-square error (RSME), a measure for the uncertainty in temperature prediction, of the East African and global lake transfer functions is 1.8 and 1.7 °C, respectively (Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, the RSME does not evidence any apparent deviation from linearity across the investigated temperature interval. This suggests that the proxy is not affected by differential lipid synthesis towards the extreme ends of the temperature spectrum (Supplementary Table 3). The accuracy with which SWTs can be reconstructed from lacustrine archives using the HDI26 is thus in a similar order of magnitude compared to other commonly applied geochemical temperature proxies32,33 and bioindicators34.

Seasonality and habitat depth strongly control biological productivity and have been demonstrated to impact proxy-based climate reconstructions35,36. Due to the close equatorial position of the East African lakes, variation in SWT over a full annual cycle is only minor and ranges between 2 and 3 °C37,38. In contrast, temperate to polar lakes are characterized by a significantly larger seasonality and more pronounced changes in temperature and productivity. In temperate Lake Constance (southern Germany), measured SWTs range from 5.1 to 25.9 °C (annual mean of 12.3 °C). Surface sediments of this lake yielded a HDI26-based SWT of 19.1 °C (Supplementary Table 3). This ~7 °C bias towards higher water temperatures compared to the annual mean implies that the HDI26–reconstructed SWT records the summer maximum of cyanobacterial activity observed in Lake Constance. A very similar bias has been reported previously from temperate Lake Schreventeich (northern Germany), in which the HDI26 recorded a late summer temperature signal16. Such an observation is also in agreement with a growth optimum of cyanobacteria shifted to higher temperatures compared to most eukaryotic algae39 and reduced availability of combined nitrogen in surface waters during summer, which promotes growth of diazotrophic cyanobacteria40. This suggests that sedimentary HG distribution patterns in temperate to polar lakes and ponds are biased by increased summer productivity and that the HDI26 in such settings does reflect a seasonal and not a mean annual temperature signal. In contrast, changes in habitat depths of heterocytous cyanobacteria are likely to exert only a minor control on the HDI26 signal. Heterocytous cyanobacteria can control their buoyancy and to some extent actively regulate their position in the water column, where they commonly form a dense cover on or close to the surface41. Extensive shading of the underlying water column during such bloom events can preclude major vertical migration of heterocytous cyanobacteria and restricts their presence close to the surface. In contrast to other organic temperature proxies (such as the TEX86), the habitat depth of the biological sources of HGs is thus comparatively well-constrained and limited to the uppermost body of the epilimnion.

Despite the overall good correlation between SWT and the HDI26, four of the East African lakes expressed relatively high HDI26 values compared to measured water temperatures (Fig. 4). These all comprise the clear and mostly shallow high-elevation tarns of Biozone 3 (>4300 masl). HG profiles of these lakes are distinctly different from those of other East African lakes. Based on comparison with HG distribution patterns derived from culture experiments17,25, benthic cyanobacteria of the genus Scytonema are likely most dominant in these tarns, which points to a significant shift in the cyanobacterial community. In the absence of large seasonal temperature variation, the observed bias in calculated HDI26 values may either be explained by a species-specific effect with a different response in lipid synthesis to temperature and/or induced by heating of cell surfaces due to light energy absorption via photosynthetic and photoprotective pigments. In situ measurements and remote sensing demonstrated that through this mechanisms, cyanobacterial surface blooms can increase temperature locally by 1–5 °C above ambient water42,43,44. Local heating of cell surfaces of pelagic cyanobacteria or shallow benthic mats may, at least in parts, explain the unexpectedly high HDI26 values observed in the high-elevation tarns. Other factors, including increased UV radiation or contributions of terrestrial heterocytous cyanobacteria with potentially different HG responses to temperature, may also affect HG distributions. Although such contributions—in particular during bloom events—may only be little, this needs to be explored in future studies.

In order to evaluate the potential of the HDI26 in reconstructing past variations in continental climates, we investigated HG distribution patterns in sediment core NP04-KH04-4A-1K collected from tropical Lake Tanganyika. The core was obtained from the distal margin of the Kayla Platform, located in the central part of the lake, in a water depth of ~330 m. The recovered sediment sequence consists of a succession of alternating diatomaceous oozes and massive to silty clays28. 14C AMS radiocarbon dating and stratigraphic correlation with parallel core KH03 indicate that the 729 cm-long sediment sequence covers the last ~37,000 years of East African climate history45. Lake Tanganyika surface sediments contained abundant HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols. The HDI26-reconstructed SWT of the surface sediment using our East African lake calibration function is 27.2 °C. This temperature is well within the measured annual SWT variation of Lake Tanganyika, which ranges from 24.1 to 28.5 °C based on a 5-year average for the time period from 2004 to 200938. The sedimentary HG distribution thus seems to record the temperature of highest cyanobacterial productivity but also in this tropical lake seems to be biased towards a warmer water temperature signal, despite the comparatively low annual SWT variability.

In the Lake Tanganyika sediment sequence, HG distribution patterns are highly variable and shift from a dominance of HG30 triols (0.73 ± 0.19) and HG30 keto-diols (0.05 ± 0.04) during the LGM to the predominance of HG26 diols (0.87 ± 0.01) and HG26 keto-ols (0.02 ± 0.01) observed in the lake surface sediment (Supplementary Table 4). These variations in the distribution of HGs are likely related to changes in the cyanobacterial community and during the LGM may arise from the spread of mat-forming cyanobacteria in the littoral and subsequent sediment transport to the profundal in a lake with a water level 250–300 m lower than present28,46.

HDI26-reconstructed SWTs of Lake Tanganyika show significant variations over time that relate to global climate trends as well as abrupt climate change events (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table 5). At the base of the record (~37,000 years BP), the HDI26-calculated SWT was 23.8 °C. Over the following 10,000 years, the lake water cooled by 1.3 °C. During the LGM, the HDI26-inferred temperature averaged ~22.5 °C and started to increase between 19,000 and 15,000 years BP, in line with rising global atmospheric CO2 concentrations (Fig. 6)47. SWT continued to increase during the deglacial period and the early Holocene to yield a maximum of 26.5 °C during the mid-Holocene (~4200 years BP), during a CO2 minimum but in keeping with other records from the African tropics48. Thereafter, HDI26 temperatures decreased gradually by ~1.8 °C and started to increase again after ~1,700 years BP to reach a temperature maximum of 27.2 °C in modern Lake Tanganyika.

Profiles are plotted as follows: a Deglacial CO2 record from the Dome Concordia (Dome C) and other ice cores47. b Tropical Lake Malawi TEX86 lake water temperature (LWT) record49,50. Light and dark purple shaded areas denote 68% and 95% confidence intervals of the reconstruction based on bootstrapping of the respective calibration56. c HDI26-based surface water temperature (SWT) record and TEX86-LWT record57 in tropical Lake Tanganyika. Light blue shading denotes the age range of the regional last glacial maximum (LGM), defined by 10Be ages of moraines from the Rwenzori Mountains69, and the Younger Dryas (YD) cold event54. The gray shaded area indicates the calibration uncertainty associated with the TEX86. The calibration uncertainty of the HDI26 is indicated in light orange, while the analytical error based on replicate measurements is shown in dark orange.

Our HDI26-SWT record indicates an overall ~4.1 °C warming in tropical East Africa from the LGM until the onset of the industrial period. This warming is generally similar to other late Pleistocene and Holocene climate records obtained from East African Rift Valley lakes, such as Lake Malawi49,50 and Lake Turkana51. Moreover, our temperature record is within the range of estimated deglacial warming in low-elevation tropical East Africa of 4 ± 2 °C based on pollen52 and lipid palaeothermometers53. Besides the superimposed long-term temperature trend, the HDI26 also provides evidence for abrupt climate change events. Though the resolution of our record is too low to study millennial-scale changes in detail, the HDI26 indicates a decline in SWT by ~0.4 °C about ~12,800 years BP, roughly coincident with the onset of the Younger Dryas (YD) cold event54 (Fig. 6). Equivalent cooling during the YD chronozone has also been documented at other locations in East Africa, such as Lake Albert55, Lake Rutundu56, and Lake Malawi49, but they are controversial as they are absent in other temperature records from this region. Our HDI26-based temperature record, however, suggests that connections between low-latitude and high-latitude may indeed impact the climate of tropical East Africa.

Although our HDI26-SWT record is very similar in terms of trends and magnitude compared to the ~4 °C inferred warming from the late Pleistocene to late Holocene based on the TEX86 lipid palaeothermometer in Lake Tanganyika57, it deviates during the youngest part of the sediment sequence. Our record indicates warming during the early Holocene that culminated in a maximum water temperature of 26.5 °C in Lake Tanganyika during the mid-Holocene. The TEX86 indicates significantly lower water temperatures during this time period45 with a temperature offset of ~1.6 °C between both proxies. Previous comparison of the TEX86 signal in suspended particulate matter with measured water column temperatures indicates that the TEX86 underestimates SWTs by ~2 °C in modern Lake Tanganyika38. This offset is in a similar order of magnitude as observed between the mid to late-Holocene TEX86-based and HDI26-reconstructed water temperatures and may causally be related to a primary residence depth of GDGT-producing Thaumarchaeota not at the surface but the oxycline that is currently situated at a water depth of ~100 m in Lake Tanganyika58. Changes in the lake’s hydrology and increased lake mixing during a cooler and drier glacial may be responsible for the close progression of both proxies by reducing the temperature difference between the residence depths of heterocytous cyanobacteria thriving at the surface of Lake Tanganyika and deep-dwelling Thaumarchaeota. In contrast, increased lake stratification and lesser mixing of the water column has been inferred for the lake during the Holocene59 and together with changes in oxycline depth46 and/or seasonal productivity is likely to explain the here observed offset between both proxy records. Nevertheless, the overall similarity of both records, as well as the good agreement of the timing and magnitude of deglacial warming compared to other low-elevation climate records from this region, including those from Lake Malawi49 and Lake Victoria60 as well as the Congo Basin61, emphasizes the robustness of the HDI26 in tracking continental climate change on regional scales.

Our data demonstrates that the HDI26 is significantly correlated with modern SWT in East African lakes as well as other polar to tropical freshwater environments, indicating that the HDI26 can be applied on a global scale and over a temperature range from 1 to ~28 °C. Its first application to a ~37,000-years sediment record from tropical Lake Tanganyika also shows that the HDI26 constitutes an independent tool to access information on past SWTs and thus on continental climate change archived in fossil lacustrine sequences. The recent discovery of HGs in late Cretaceous sediments (80–90 Myr)62 and sediments covering the Cretaceous–Palaeogene boundary (~66 Myr)63 thus suggests that HG-based indices (such as the HDI26) may allow reconstructing SWTs and continental climates throughout the Cenozoic and beyond.

Methods

Lakes and sediment sampling

Surface sediments (in most cases 0–1 cm) were collected from 46 East African lakes located in the Rwenzori Mountains (Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo) and Mt. Kenya (Kenya) but East African Rift Valley lakes were also included (see Supplementary Table 1). The lakes were situated on an altitudinal transect from 615 to 4504 masl and were selected to cover a wide range of physical, chemical, and hydrological parameters including, e.g. water temperature, lake size and depth, pH and productivity (see Supplementary Table 1 for a comprehensive description of environmental variables)23,24. Surface sediments from tropical Lake Towuti (Indonesia), Lake Lading (Indonesia) and Lake Klakah (Indonesia) were obtained in June 2013 using an Uwitec gravity corer. Surface sediments from temperate Lake Constance (Germany) were taken in summer 2016 also using an Uwitec gravity corer. Surface sediments of subpolar Laguna Potrok Aike (southern Patagonia, Argentina) were collected from short gravity core PTA02/4 taken in 2003 and stored at +4 °C thereafter. Microbial mats were collected from Conophyton Pond and Orange Pond on the McMurdo Ice Shelf (Antarctica) in January 2018 and stored at −20 °C thereafter. All samples were shipped to Christian-Albrechts-University on dry ice where they were stored frozen until they were processed and analyzed for HG distribution patterns and HDI26 values. The here generated data was complemented by previously published HG signatures and HDI26 values from surface sediments and water column experiments in temperate Lake Schreventeich (Germany)16.

Subsurface sediments from Lake Tanganyika were collected from piston core NP04-KH04-4A-1K taken on the Kalya Horst (S 6°42′, E 29°50′) at a water depth of ~330 m28. To minimize degradation of the sedimentary organic matter, the core was stored cold (+4 °C) at Brown University since its recovery in 2004. Solvent-cleaned spatulas were used to collect 5 mm-thick sediment slices, which were transferred to Whirl-Pak sample bags for transport, at an average resolution of ~1500 years. Together with the surface sediments, these samples were shipped to Christian-Albrechts-University on dry ice. Upon arrival, all sediments were lyophilized, ground to a fine powder using a solvent-cleaned agate pestle and mortar and stored frozen until further processing.

SWTs of polar to tropical lakes

All SWTs reported here were collected within the top 10 cm of the water column. SWT of East African lakes were taken during several field campaigns from 1996 to 2010 and varied from 5.7 °C in Hut Tarn (4504 masl) to 27.9 °C in Lake Albert (615 masl)23,24. Water temperatures of tropical Lake Towuti (Indonesia) were recorded from 2012 to 2014 with Hobo Tidbit data loggers (CiK Solutions, Germany) at 15-m depth intervals64. Over the time course of a year, SWT ranged from 28.9 °C in August 2013 to 30.4 °C in March 2013 with a mean annual temperature signal of 29.8 ± 0.5 °C. SWT of Lake Klakah (Indonesia) and Lake Lading (Indonesia) were determined during field work conducted in June 2013 and January 2014; these averaged 29.5 and 28.7 °C, respectively. Water temperatures of temperate Lake Constance (southern Germany) are continuously monitored by the environmental agency of the state Baden-Württemberg. From 2011 to 2015, SWT varied from 5.1 ± 0.3 °C in winter to 20.6 ± 1.0 °C in summer. The average annual SWT was 12.3 ± 0.7 °C. Water temperature measurements were conducted in Lake Schreventeich (northern Germany) from July to October 2014 using an Oxi 1970i instrument coupled to a CellOx325 oxygen probe (WTW, Germany)16. SWT of the small meromictic lake varied from 24.0 °C in early August to 10.5 °C in late October. Highest abundances of HGs, in conjunction with highest in-lake productivity, were observed in the first half of September with SWT averaging 15.7 °C. Temperatures of subpolar Laguna Potrok Aike were recorded at seven different water depths from 2014 to 2017 using M-08TR Minilog thermistors (Vemco Ltd., Canada) attached to a mooring65. The lake SWT over the 4-year period varied from 3.7 ± 0.2 °C in September to 10.7 ± 0.7 °C in February. The mean SWT signal was 7.1 ± 0.4 °C and the summer SWT averaged 9.5 ± 0.5 °C. Water temperatures of the Antarctic meltwater ponds were determined during the field sampling campaign in January 2018 and ranged between 1.0 °C for Conophyton Pond and 2.5 °C for Orange Pond. Water temperatures were collected in austral summer and reflect the time of highest productivity in the ponds, while temperatures were below freezing point for the remainder of the year66, preventing activity of cyanobacteria and the synthesis of HGs.

Heterocyte glycolipid extraction and analysis

Between 0.5 and 2 g of dried and homogenized lake surface and subsurface sediments were extracted using a modified Bligh and Dyer procedure16. For this, a known volume of a single-phase solvent mixture of methanol (MeOH)/dichloromethane (DCM)/phosphate buffer (2:1:0.8; v:v:v) was added to the sediments, which were then extracted in an ultrasonic bath for 10 min. After centrifugation (4000 × g, 10 min), the supernatant was collected and the residue extracted three more times with the above described solvent mixture. DCM and phosphate buffer were added to the combined extracts to a volume ratio of 1:1:0.9 (v:v:v), resulting in phase separation. The bottom layer, containing the organic fraction, was collected after centrifugation (1000 × g, 5 min) and the remaining MeOH/phosphate buffer phase was washed twice with DCM. The bulk of organic solvents was removed by rotary evaporation and the Bligh and Dyer extract (BDE) dried under a gentle stream of nitrogen. Aliquots of the BDEs were re-dissolved in a solvent mixture of n-hexane:2-propanol:H2O (71:27:1, v:v:v) to a concentration between 3 and 9 mg mL−1 dependent on the abundance of the target analyte, filtered through a 0.4 µm mesh-size regenerated cellulose syringe filter and subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC/ESI-MS2).

HGs were measured and identified following previously established analytical protocols16,67. Separation of HGs was achieved using a Waters Alliance 2690 HPLC system equipped with a Phenomenex Luna NH2 column (150 × 2 mm; 3 µm particle size) and a guard column of the same material, which were both maintained at 30 °C. HGs were eluted using the following gradient profile: 95% A/5% B to 85% A/15% B in 10 min (held 7 min) at 0.5 mL min−1, followed by backflushing with 30% A/70% B at 0.2 mg mL−1 for 25 min and re-equilibrating the column with 95% A/5% B for 15 min. Solvent A was n-hexane:2-propanol:HCO2H:14.8 M NH3 aq. (79:20:0.12:0.04; v:v:v:v) and solvent B was 2-propanol:H2O:HCO2H:14.8 M NH3 aq. (88:10:0.12:0.04; v:v:v:v). Detection of HGs was performed using a Micromass Quattro LC triple quadrupole MS equipped with an ESI interface and operated in positive ion mode. Source conditions were as follows: capillary 3.5 kV, cone 20 V, desolvation temperature 230 °C, source temperature 120 °C; cone gas 80 L h−1 and desolvation gas 230 L h−1. HGs were recorded in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode using previously established mass spectral information19,30,67 and monitoring the following transitions: m/z 547 → 415 (pentose HG26 diols), m/z 561 → 415 (deoxyhexose HG26 diols), m/z 575 → 413 (HG26 keto-ols), m/z 577 → 415 (HG26 diols), m/z 603 → 441 (HG28 keto-ols), m/z 605 → 443 (HG28 diols), m/z 619 → 457 (HG28 keto-diols), m/z 621 → 459 (HG28 triols), m/z 631 → 469 (HG30 keto-ols), m/z 633 → 471 (HG30 diols), m/z 647 → 485 (HG30 keto-diols), m/z 649 → 487 (HG30 triols), m/z 675 → 513 (HG32 keto-diols), and m/z 677 → 515 (HG32 triols). Quantification of HGs was achieved by integration of peak areas using the QuanLynx application software. To study changes in cyanobacterial community composition, fractional abundances (FA) of HGs were calculated. For this, the abundance of individual HGs was divided by the summed abundances of all HGs detected in a given sample.

In the East African and polar to tropical lakes, HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols usually consisted of two structural isomers. The relative proportion of these components was calculated as the abundance of each isomer in relation to the abundance of all HG26 diols and HG26 keto-ols:

where x denotes HG26 keto-ol (I) or HG26 keto-ol (II) and y represents HG26 diol (I) or HG26 diol (II). Bivariate correlation analysis showed that SWT in these lakes was most significantly correlated with changes in the relative abundance of the most dominant of these isomers. Consequently, the most abundant structural isomer of the HG26 diol and HG26 keto-ol in each sample was used for the determination of the HDI26:

Statistical analyses

In order to identify statistically significant correlations between HG distributions and the HDI26 with environmental parameters, we performed two-tailed bivariate correlation analysis. The degree of association between environmental variables and fractional abundances of HG26 keto-ols and HG26 diols as well as the HDI26 after removing the effect of SWT as controlling variable was tested using two-tailed partial correlation analysis. Comparison of slopes and intercepts between the regression of the East African and other calibration functions was achieved by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). All of these analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (Version 27.0). Hierarchical clustering of the East African lakes based on HG distribution patterns was achieved using the scientific data analysis software Past (Version 4.03). The chord distance, a modification of the Euclidean distance, was applied to the normalized data set as it provides robust results in ecological resemblance studies68.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Tierney, J. E. et al. Past climates inform our future. Science 370, eaay3701 (2020).

IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2014).

Prahl, F. G. & Wakeham, S. G. Calibration of unsaturation patterns in long-chain ketone compositions for palaeotemperature assessment. Nature 330, 367–369 (1987).

Schouten, S., Hopmans, E. C., Schefuß, E. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Distributional variations in marine crenarchaeotal membrane lipids: a new tool for reconstructing ancient sea water temperatures? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 204, 265–274 (2002).

Rampen, S. W. et al. Evaluation of long chain 1,14-alkyl diols in marine sediments as indicators for upwelling and temperature. Org. Geochem. 76, 39–47 (2014).

Conte, M. H. et al. Global temperature calibration of the alkenone unsaturation index (UK’37) in surface waters and comparison with surface sediments. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7, Q02005 (2006).

Schouten, S., Hopmans, E. C. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. The organic geochemistry of glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether lipids: a review. Org. Geochem. 54, 19–61 (2013).

Robinson, S. A. et al. Early Jurassic North Atlantic sea‐surface temperatures from TEX86 palaeothermometry. Sedimentology 64, 215–230 (2017).

Forster, A., Schouten, S., Baas, M. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Mid-Cretaceous (Albian-Santonian) sea surface temperature record of the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Geology 35, 919–922 (2007).

LaRiviere, J. P. et al. Late Miocene decoupling of oceanic warmth and atmospheric carbon dioxide forcing. Nature 486, 97–100 (2012).

Zachos, J. C. et al. Extreme warming of mid-latitude coastal ocean during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum: inferences from TEX86 and isotope data. Geology 34, 737–740 (2006).

Powers, L. A. et al. Crenarchaeotal membrane lipids in lake sediments: a new paleotemperature proxy for continental paleoclimate reconstruction? Geology 32, 613–616 (2004).

Toney, J. L. et al. Climatic and environmental controls on the occurrence and distributions of long chain alkenones in lakes of the interior United States. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 1563–1578 (2010).

De Jonge, C. et al. Occurrence and abundance of 6-methyl branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers in soils: implications for palaeoclimate reconstruction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 141, 97–112 (2014).

Tierney, J. E. & Russell, J. M. Distributions of branched GDGTs in a tropical lake system: implications for lacustrine application of the MBT/CBT paleoproxy. Org. Geochem. 40, 1032–1036 (2009).

Bauersachs, T., Rochelmeier, J. & Schwark, L. Seasonal lake surface water temperature trends reflected by heterocyst glycolipid-based molecular thermometers. Biogeosciences 12, 3741–3751 (2015).

Gambacorta, A., Trincone, A., Soriente, A. & Sodano, G. Chemistry of glycolipids from the heterocysts of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria. Curr. Top. Phytochem. 2, 145–150 (1999).

Bauersachs, T. et al. Distribution of heterocyst glycolipids in cyanobacteria. Phytochemistry 70, 2034–2039 (2009).

Wörmer, L., Cirés, S., Velázquez, D., Quesada, A. & Hinrichs, K.-U. Cyanobacterial heterocyst glycolipids in cultures and environmental samples: diversity and biomarker potential. Limnol. Oceanogr. 57, 1775–1788 (2012).

Whitton, B. Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time (Springer Netherlands, 2012).

Bauersachs, T., Stal, L. J., Grego, M. & Schwark, L. Temperature induced changes in the heterocyst glycolipid composition of N2 fixing heterocystous cyanobacteria. Org. Geochem. 69, 98–105 (2014).

Stal, L. J. Is the distribution of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria in the oceans related to temperature? Environ. Microbiol. 11, 1632–1645 (2009).

Loomis, S. E., Russell, J. M., Ladd, B., Street-Perrott, F. A. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Calibration and application of the branched GDGT temperature proxy on East African lake sediments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 357–358, 277–288 (2012).

Loomis, S. E., Russell, J. M., Eggermont, H., Verschuren, D. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Effects of temperature, pH and nutrient concentration on branched GDGT distributions in East African lakes: implications for paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Org. Geochem. 66, 25–37 (2014).

Bauersachs, T. et al. Heterocyte glycolipids indicate polyphyly of stigonematalean cyanobacteria. Phytochemistry 166, 112059 (2019).

Hecky, R. E. & Kling, H. J. The phytoplankton and protozooplankton of the euphotic zone of Lake Tanganyika: species composition, biomass, chlorophyll content, and spatio-temporal distribution. Limnol. Oceanogr. 26, 548–564 (1981).

Descy, J.-P. & Sarmento, H. Microorganisms of the East African great lakes and their response to environmental changes. Freshw. Rev. 1, 59–73 (2008).

McGlue, M. M. et al. Seismic records of late Pleistocene aridity in Lake Tanganyika, tropical East Africa. J. Paleolimnol. 40, 635–653 (2008).

Bale, N. J. et al. Impact of trophic state on the distribution of intact polar lipids in surface waters of lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 1065–1077 (2016).

Bauersachs, T. et al. Distribution of long chain heterocyst glycolipids in cultures of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus and a hot spring microbial mat. Org. Geochem. 56, 19–24 (2013).

Rethemeyer, J. et al. Distribution of polar membrane lipids in permafrost soils and sediments of a small high Arctic catchment. Org. Geochem. 41, 1130–1145 (2010).

D’Andrea, W. J., Huang, Y., Fritz, S. C. & Anderson, N. J. Abrupt Holocene climate change as an important factor for human migration in West Greenland. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9765–9769 (2011).

Russell, J. M., Hopmans, E. C., Loomis, S. E., Liang, J. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Distributions of 5- and 6-methyl branched glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (brGDGTs) in East African lake sediment: effects of temperature, pH, and new lacustrine paleotemperature calibrations. Org. Geochem. 117, 56–69 (2018).

Pérez, L. et al. Bioindicators of climate and trophic state in lowland and highland aquatic ecosystems of the Northern Neotropics. Rev. Biol. Trop. 61, 603–644 (2013).

Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., Ossebaar, J., Abbas, B., Schouten, S. & Verschuren, D. Fluxes and distribution of tetraether lipids in an equatorial African lake: constraints on the application of the TEX86 palaeothermometer and BIT index in lacustrine settings. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 4232–4249 (2009).

Deng, L., Jia, G., Jin, C. & Li, S. Warm season bias of branched GDGT temperature estimates causes underestimation of altitudinal lapse rate. Org. Geochem. 96, 11–17 (2016).

Vollmer, M. K. et al. Deep-water warming trend in Lake Malawi, East Africa. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50, 727–732 (2005).

Kraemer, B. M. et al. Century-long warming trends in the upper water column of Lake Tanganyika. PLoS ONE 10, e0132490 (2015).

Paerl, H. W., Hall, N. S. & Calandrino, E. S. Controlling harmful cyanobacterial blooms in a world experiencing anthropogenic and climatic-induced change. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 1739–1745 (2011).

Moisander, P. H., Paerl, H. W. & Zehr, J. P. Effects of inorganic nitrogen on taxa-specific cyanobacterial growth and nifH expression in a subtropical estuary. Limnol. Oceanogr. 53, 2519–2532 (2008).

Paerl, H. W. & Otten, T. G. Harmful cyanobacterial blooms: causes, consequences, and controls. Microb. Ecol. 65, 995–1010 (2013).

Kahru, M., Leppänen, J.-M. & Rud, O. Cyanobacterial blooms cause heating of the sea surface. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 101, 1–7 (1993).

Wurl, O. et al. Warming and inhibition of salinization at the ocean’s surface by cyanobacteria. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 4230–4237 (2018).

Capone, D. et al. An extensive bloom of the N2-fixing cyanobacterium Trichodesmium erythraeum in the central Arabian Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 172, 281–292 (1998).

Tierney, J. E. et al. Northern hemisphere controls on tropical southeast African climate during the past 60,000 years. Science 322, 252–255 (2008).

Gasse, F., Lédée, V., Massault, M. & Fontes, J. C. Water-level fluctuations of Lake Tanganyika in phase with oceanic changes during the last glaciation and deglaciation. Nature 342, 57–59 (1989).

Köhler, P., Nehrbass-Ahles, C., Schmitt, J., Stocker, T. F. & Fischer, H. Compilations and splined-smoothed calculations of continuous records of the atmospheric greenhouse gases CO2, CH4, and N2O and their radiative forcing since the penultimate glacial maximum. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 363–387 (2017).

Ivory, S. J. & Russell, J. Lowland forest collapse and early human impacts at the end of the African Humid Period at Lake Edward, equatorial East Africa. Quat. Res. 89, 7–20 (2018).

Powers, L. A. Large temperature variability in the southern African tropics since the last glacial maximum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L08706 (2005).

Woltering, M., Johnson, T. C., Werne, J. P., Schouten, S. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Late Pleistocene temperature history of Southeast Africa: a TEX86 temperature record from Lake Malawi. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 303, 93–102 (2011).

Berke, M. A., Johnson, T. C., Werne, J. P., Schouten, S. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. A mid-Holocene thermal maximum at the end of the African Humid Period. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 351–352, 95–104 (2012).

Bonnefille, R., Roeland, J. C. & Guiot, J. Temperature and rainfall estimates for the past 40,000 years in equatorial Africa. Nature 346, 347–349 (1990).

Sinninghe Damsté, J. S., Ossebaar, J., Schouten, S. & Verschuren, D. Distribution of tetraether lipids in the 25-ka sedimentary record of Lake Challa: extracting reliable TEX86 and MBT/CBT palaeotemperatures from an equatorial African lake. Quat. Sci. Rev. 50, 43–54 (2012).

Brauer, A. et al. High resolution sediment and vegetation responses to Younger Dryas climate change in varved lake sediments from Meerfelder Maar, Germany. Quat. Sci. Rev. 18, 321–329 (1999).

Berke, M. A. et al. Characterization of the last deglacial transition in tropical East Africa: insights from Lake Albert. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 409, 1–8 (2014).

Loomis, S. E. et al. The tropical lapse rate steepened during the last glacial maximum. Sci. Adv. 3, e1600815 (2017).

Tierney, J. E., Russell, J. M. & Huang, Y. A molecular perspective on Late Quaternary climate and vegetation change in the Lake Tanganyika basin, East Africa. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 787–800 (2010).

Schouten, S., Rijpstra, W. I. C., Durisch-Kaiser, E., Schubert, C. J. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Distribution of glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether lipids in the water column of Lake Tanganyika. Org. Geochem. 53, 34–37 (2012).

Haberyan, K. A. & Hecky, R. E. The late Pleistocene and Holocene stratigraphy and paleolimnology of Lakes Kivu and Tanganyika. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 61, 169–197 (1987).

Berke, M. A. et al. Molecular records of climate variability and vegetation response since the Late Pleistocene in the Lake Victoria basin, East Africa. Quat. Sci. Rev. 55, 59–74 (2012).

Weijers, J. W. H., Schefuß, E., Schouten, S. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Coupled thermal and hydrological evolution of tropical Africa over the last deglaciation. Science 315, 1701–1704 (2007).

Klages, J. P. et al. Temperate rainforests near the South Pole during peak Cretaceous warmth. Nature 580, 81–86 (2020).

Schaefer, B. et al. Microbial life in the nascent Chicxulub crater. Geology 48, 328–332 (2020).

Costa, K. M., Russell, J. M., Vogel, H. & Bijaksana, S. Hydrological connectivity and mixing of Lake Towuti, Indonesia in response to paleoclimatic changes over the last 60,000 years. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 417, 467–475 (2015).

Ohlendorf, C. et al. Mechanisms of lake-level change at Laguna Potrok Aike (Argentina) - insights from hydrological balance calculations. Quat. Sci. Rev. 71, 27–45 (2013).

Hawes, I., Howard-Williams, C. & Sorrell, B. Decadal timescale variability in ecosystem properties in the ponds of the McMurdo Ice Shelf, southern Victoria Land, Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 26, 219–230 (2014).

Bauersachs, T. et al. Rapid analysis of long-chain glycolipids in heterocystous cyanobacteria using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 23, 1387–1394 (2009).

Shirkhorshidi, A. S., Aghabozorgi, S. & Wah, T. Y. A comparison study on similarity and dissimilarity measures in clustering continuous data. PLoS ONE 10, e0144059 (2015).

Kelly, M. A. et al. Expanded glaciers during a dry and cold last glacial maximum in equatorial East Africa. Geology 42, 519–522 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Christoph Mayr provided surface sediments of Laguna Potrok Aike. Roger E. Summons and Ian Hawes are thanked for the provision of mat samples from Bratina Island, Antarctica. Martin Wessels and Sandra Böddeker are acknowledged for assistance during the Lake Constance sampling campaign. The environmental agency Baden-Württemberg is thanked for providing SWT data from Lake Constance for the time period from 2011 to 2015. We acknowledge assistance from Satria Bijaksana and the Institut Teknologi Bandung during field work in Indonesia. This research was funded by Christian-Albrechts-University through institutional grants awarded to L.S. Funding for T.W.E. was provided by the NASA Exobiology program (grant number: 80NSSC19K0465 awarded to Roger E. Summons) and also by the Alexander von Humboldt-Gesellschaft through the Feodor-Lynen-Fellowship.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.B. and L.S. designed the study. J.M.R., T.W.E. and A.S. provided sample material and environmental data. T.B. performed the analysis of HGs and interpretation of the results. L.S. provided personnel and laboratory facilities. The manuscript was written by T.B. All co-authors commented on the manuscript and provided input to its final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Bernhard Naafs and other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bauersachs, T., Russell, J.M., Evans, T.W. et al. A heterocyte glycolipid-based calibration to reconstruct past continental climate change. Nat Commun 12, 2406 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22739-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22739-3

This article is cited by

-

Mid-Holocene expansion of the Indian Ocean warm pool documented in coral Sr/Ca records from Kenya

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.