Abstract

Quasi-two-dimensional (quasi-2D) Ruddlesden–Popper (RP) perovskites such as BA2Csn–1PbnBr3n+1 (BA = butylammonium, n > 1) are promising emitters, but their electroluminescence performance is limited by a severe non-radiative recombination during the energy transfer process. Here, we make use of methanesulfonate (MeS) that can interact with the spacer BA cations via strong hydrogen bonding interaction to reconstruct the quasi-2D perovskite structure, which increases the energy acceptor-to-donor ratio and enhances the energy transfer in perovskite films, thus improving the light emission efficiency. MeS additives also lower the defect density in RP perovskites, which is due to the elimination of uncoordinated Pb2+ by the electron-rich Lewis base MeS and the weakened adsorbate blocking effect. As a result, green light-emitting diodes fabricated using these quasi-2D RP perovskite films reach current efficiency of 63 cd A−1 and 20.5% external quantum efficiency, which are the best reported performance for devices based on quasi-2D perovskites so far.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal halide perovskites exhibit distinctive properties such as tunable bandgaps and narrow emission linewidths, which are combined with low cost and facile solution processability1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. These useful characteristics have made them extremely promising candidates for light-emitting diode (LED) and display applications11. Tremendous progress has already been achieved in improving perovskite LEDs (PeLEDs) based on three-dimensional (3D) perovskite films2,12,13,14,15,16,17, but their overall electroluminescence (EL) performance still lags behind those of state-of-the-art organic LEDs and other solid-state lighting devices such as inorganic quantum-dot-based LEDs11,18,19,20. A slow electron–hole capture rate stemming from inherent small exciton binding (only tens of meV) and long diffusion length leads to inefficient radiative recombination in 3D perovskites21,22,23,24, going against high emission efficiency naturally.

Quasi-two-dimensional (quasi-2D) perovskites offer larger exciton binding energy (hundreds of meV) and lower ion mobility compared with 3D perovskites23,25,26,27,28, making them even more promising light-emitting materials. Quasi-2D perovskites with Ruddlesden–Popper (RP) structure have the general formula of L2An−1MnX3n+123,24,29, where L is a large-size organic spacer cation with low conductivity (“barrier”) such as butylammonium (BA), phenylethylammonium (PEA), naphthylmethylamine (NMA), etc., A is Cs, methylammonium (MA), or formamidinium (FA), M is a divalent metal cation such as Pb or Sn, X is a halide anion (Cl, Br, or I), and n is the number of MX64- sheets (which constitute a “quantum well”, QW) sandwiched between the organic spacers25. There are two key points that determine the emission efficiency of quasi-2D RP perovskites, namely the exciton energy transfer process and the deep defect state formation derived from the bandgap broadening30,31,32. The distribution of energy domains is inhomogeneous in quasi-2D perovskites due to the random stacking of low-dimensional structures with varying degrees of quantum and dielectric confinement6,33,34. The small-n phases (n ≤ 3) with wide-bandgap QWs are prone to form because of their low formation energy35, resulting in inefficient energy transfer processes from small-n phases to large-n phases. The defect states that result from lattice defects and the bandgap broadening due to the quantum confinement effect, act as charge-carrier traps during the energy transfer process, which lowers the emission efficiency.

Here, we seek to realize the full potential of quasi-2D perovskites for LEDs by smoothing the energy transfer pathway through structure reconstruction and defect reduction using methanesulfonate (MeS) additive. The strong hydrogen-bonding interaction between MeS and BA spacer cations effectively modulates the crystallization kinetics and leads to an increased ratio of large-n phase with narrow bandgap QWs, while the uncoordinated Pb2+ ions on the perovskite surface are simultaneously reduced due to the weakened adsorbate blocking effect caused by MeS addition, as well as the formation of Lewis adducts. Quasi-2D green PeLEDs fabricated following this strategy show current efficiency (CE) of 63 cd A−1 and up to 20.5% external quantum efficiency (EQE), making this device the best-performing quasi-2D perovskite LED reported in literature so far.

Results

Fabrication of MeS-treated BA2Csn−1PbnBr3n+1 perovskite films

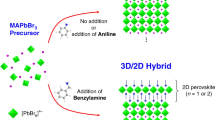

The perovskite precursor solutions comprised of cesium bromide (CsBr), lead bromide (PbBr2), butylammonium bromide (BABr), poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO), and a varying ratio of cesium methanesulfonate (CsMeS) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (see Methods for details). Here, the ratio of the added MeS is defined as the molar ratio of CsMeS-to-PbBr2 (denoted as “x%-MeS” further on). The MeS-treated quasi-2D perovskite films with a chemical formula of BA2Csn−1PbnBr3n+1 were prepared on indium tin oxide (ITO) substrates pre-coated with poly(9,9-dioctylfluorenyl-2,7-diyl)-co-(4,4′-(N-(4-sec-butylphenyl)diphenylamine) (TFB): poly(9-vinylcarbazole) (PVK) hole transport layer (HTL) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) interface modified layer by one-step solution coating of the precursor solutions, followed by thermal annealing under nitrogen atmosphere, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. The CsMeS molecule consists of two parts: a Cs+ cation and a MeS− anion, whose molecular structure is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The introduction of MeS in precursor solution can control the crystallization growth kinetics of quasi-2D perovskite films resulting in enhanced exciton energy transfer from small-n phases to large-n phases, which will be discussed below in detail.

Schematic illustrations of the colloidal clusters’ structures in precursor solutions and phase distributions of n values in films after thermal annealing without (top pathway) and with (bottom pathway) addition of MeS, where different energy transfer pathways from small-n phases to large-n phases are presented. Crystal orientations in the perovskite films were verified by grazing-incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS) measurements (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

Effect of MeS addition on growth of quasi-2D perovskite films

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations (see Methods) reveal that the spacer BA prefers to bind MeS via three hydrogen bonds rather than to bind Br anion. The following reaction was investigated by DFT simulations:

where BABr, CsMeS, and BAMeS were considered in the form of free molecules, and CsBr in the crystalline form of space group \(Fm\bar 3m\). Their relaxed structures are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The calculated reaction free energy is −2.16 eV, indicating a strong driving force toward the formation of BAMeS. Indeed, the binding energy of BA and MeS was calculated to be 4.96 eV, which is much higher than both of BA and Br (4.00 eV), and Cs and MeS (4.39 eV). This suggests that MeS tends to bind BA via triple hydrogen bonding. The formation of hydrogen bonding incurs a charge redistribution of 0.84 e (electron) between BA and MeS, which is larger than that (0.70 e) between BA and Br (Fig. 2). Therefore, the strong affinity of the spacer cation for MeS fosters a higher probability for spacer-free nanosheet formation, and their stacking growth. This interaction is further confirmed by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra (Supplementary Fig. 3). The proton resonance signal of ammonium (NH3+) of BA (peak at δ = 7.65 ppm) shifts to low-field after incorporation of MeS (7.70 ppm). The variation in the chemical shift indicates the formation of hydrogen bonds between BA and MeS, which leads to the deshielding effect36,37. This enables us to increase the proportion of large-n phases in the overall perovskite phase distribution.

MeS molecules are homogeneously distributed over the quasi-2D perovskite films as shown in the energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping data (Supplementary Fig. 4). To address the influence of MeS on the perovskite phase distribution, measurements of the X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) that track the N signal (where BA is the only source of that atomic species and thus the signal stands for the phase distribution changes) along with decreasing the perovskite film thickness by increasing the Ar+ etching time were conducted. The gradual decrease in N content for both control and MeS-treated quasi-2D perovskite films were revealed (Supplementary Fig. 5), indicating that the multiple phases existing in quasi-2D perovskite films are arranged from small-n to large-n in the direction perpendicular to the substrate. The S signal (where MeS was the only source of that species) has a gradient content from high to low across the film from the top to the bottom (Supplementary Fig. 5b), resulting in an orderly phase arrangement in the vertical crystal spatial distribution.

Absorption spectra were measured to further analyze the effect of MeS on the phase distribution of quasi-2D perovskites. The control film produced without MeS treatment exhibits several exciton absorption peaks located at 403, 434, 467, and 516 nm (Supplementary Fig. 6), which correspond to phases with n = 1, 2, 3, and n ≥ 4, respectively38,39,40. The MeS-treated film exhibits weaker absorption peaks for small-n phases, and the 10%-MeS-treated film exhibits only one sharp exciton absorption peak (Supplementary Fig. 7a), suggesting a decrease in the content of small-n phases as the MeS content increased. As shown in the corresponding XRD patterns (Supplementary Fig. 7b, c), the appearance of the (002) plane41 for the n = 1 phase is hindered with increasing MeS content, consistent with the absorption analysis.

Energy transfer in quasi-2D perovskite films

The exciton energy transfer in quasi-2D perovskite films was studied by transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy and steady-state photoluminescence (PL), and time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectroscopy. TA spectra shown in Fig. 3a–d reveal how the addition of MeS influences the dynamics of photo-generated carriers within quasi-2D perovskite films. The control perovskite film features four pronounced ground-state bleach (GSB) peaks at 404, 436, 465, and 513 nm corresponding to n = 1, 2, 3, and n ≥ 4 phases in the TA spectra at different selected delay times, respectively (Fig. 3a). The peak positions of these transitions are consistent with those observed in the steady-state absorption spectra (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Note that the exciton resonance at GSBn = 2 persists after a long excitation time (101 ps), suggesting that there are excitons accumulated in the n = 2 phase in particular, resulting from the incomplete energy transfer between the different phases42.

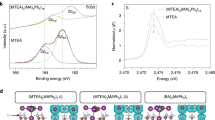

a, b TA spectra at selected timescales. c, d TA kinetics traces probed at a different wavelength for the control (a, c) and MeS-treated perovskite films (b, d), respectively (excited at 365 nm). e Steady-state PL spectra and f TRPL decay of the control (emission wavelength: 512 nm) and MeS-treated perovskite film on glass substrates (emission wavelength: 514 nm) excited at 365 nm.

For the 8%-MeS-treated perovskite film, the exciton resonance at GSBn = 1 does not appear in the TA spectrum (Fig. 3b), indicating that the population fraction of the small-n phases was dramatically reduced. At a probe time of 101 ps, only the exciton bleach at GSBn ≥ 4 was observed in this sample. This is further confirmed by visualizing the same data as TA kinetics traces (Fig. 2c, d). The ultrafast decay component for the control film exhibits time constants (τ1) of 144 fs (n = 1), 329 fs (n = 2), and 973 fs (n = 3), which is closely matched with the formation (rise) time constant (τet) of 1202 fs for GSBn ≥ 4 (Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, the decay kinetics for GSBn ≥ 4 peak of 8%-MeS-treated perovskite film shows a shorter formation time of 910 fs, demonstrating that an accelerated exciton energy transfer occurs inside the reconstructed phases enabling more efficient energy transfer from small-n phases to large-n phases.

The steady-state PL spectra and TRPL spectroscopy analysis are in good agreement with the results of TA kinetics. The 8%-MeS-treated perovskite film shows a much higher PL quantum yield (PLQY) of 73% than that of 47% for the control perovskite film (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 8). Such a dramatic improvement can be attributed to the improved energy transfer from small-n to large-n phases, ultimately enhancing the radiative recombination in the large-n phases. We also observed a slight redshift of the PL emission upon increasing the MeS content which is caused by the increased proportion of large-n phases24. TRPL spectroscopy shows an average recombination lifetime (τavg) of 101 ns for 8%-MeS-treated films (Supplementary Table 2), which constitutes a 1.3-fold increase as compared to the control perovskite film (77 ns), corresponding to the enlarged perovskite crystal sizes (shift to higher n) after MeS treatment. For the control perovskite film, the PLQY was around 47% which, if the proportion of dark emitters is neglected, would imply almost equal radiative and non-radiative recombination rates. The fact that the PLQY increases to 73% with the MeS-treated perovskite, even though the decay rate is slower, indicates that the effective non-radiative rate must also have significantly slowed down (or the dark fraction of emitters has significantly dropped), which in any case would result in brighter emission (and indeed, both of these factors could have jointly contributed to the improved PLQY). In the further film measurements discussed below, we offer evidence that a significant contribution to the reduction in the non-radiative rate is the decrease of trap densities in MeS-treated perovskite.

Apart from the structural reconstruction of perovskite films, the elimination (or partial elimination) of uncoordinated Pb2+ ions is yet another factor that ensures a more efficient exciton energy transfer pathway. Excitons trapped by uncoordinated Pb2+ are prone to recombine non-radiatively43. For the case of the samples discussed here, oxygen (O) atoms possessing lone pair electrons on the S = O groups of MeS could coordinate with the Pb-exposed surface through the formation of Lewis adducts44, favoring an efficient energy transfer into the emitting phases (as illustrated in Fig. 3f). Also, the reduction of small-n phases—which would appear to feature a greater abundance of non-radiative trap sites—should improve the radiative recombination45. Evidence of the coordination between MeS and Pb2+ is obtained from Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and XPS (Fig. 4). The peak at 1029 cm−1 derived from the S=O stretching vibration (ν (S=O)) of the -SO3− in FTIR spectra of powdered CsMeS41 shifts to a higher wavenumber of 1052 cm−1 in the presence of PbBr2, indicating the coordination of MeS and Pb2+ cations46,47,48. To further confirm whether this coordination exists in the MeS-treated perovskite films, we conducted XPS analysis of high-resolution S 2p, Pb 4f, and Br 3d chemical states. As shown in Fig. 4b, the peaks at 168.1 and 169.8 eV corresponding to respective S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 are observed in the MeS-treated perovskite film49. Figure 4c, d shows the XPS spectra for Pb and Br, respectively, where for the photoemission of Pb 4f, both Pb 4f7/2 (138.2 eV) and Pb 4f5/2 (142.9 eV), signals in the 8%-MeS-treated film shift to lower binding energy by around 0.2 eV. Such negative shifts of Pb 4f binding energy indicate the decrease of the cationic charge on the Pb ion since the S=O donates the lone electron pair on the oxygen atoms to the empty 6p orbital of Pb2+ cations49. The shift toward lower binding energy is also observed for the Br 3d spectrum, which is caused by the disturbance due to the electron donation from MeS to Pb2+ through the formation of Lewis adducts, subsequently resulting also in the change of static interactions between Pb2+ and Br− ions50. Besides, the strong affinity of BA with MeS reduces the chance of BA adsorption on the perovskite surface, and this weakens the blocking effect of BA on the growth of the perovskite. As the blocking effect of the adsorbate tends to induce defects in crystal growth51,52,53, the reduced BA adsorption caused by the presence of MeS may also contribute to alleviating defect formation in the perovskite films.

To support this hypothesis, the defect density was evaluated for hole-only devices with the structures of ITO/TFB:PVK/PVP/perovskite/MoO3/Al by performing space-charge-limited current (SCLC) measurements (Supplementary Fig. 9). The device current has a linear proportionality to the drive voltage up to the trap-filled limit (VTFL)54,55,56. It can be seen that the MeS-treated film presented a lower VTFL (1.08 V) compared to those of the control film (1.45 V), demonstrating that the trap density in the perovskite film was reduced. Consequently, we extracted a trap density of ntraps = (5.05 ± 0.18) × 1017 cm−3 for the MeS-treated film, which is lower than that of the control film (ntraps = (9.87 ± 0.45) × 1017 cm−3). We further observed that, when the perovskite films were excited under different excitation powers, both the PLQYs of the control and MeS-treated films increased with the increase of excitation power, and the MeS-treated films showed remarkably higher PLQY values over the whole excitation range (Supplementary Fig. 10) due to the increased fraction of bimolecular recombination and trap-filling behavior17.

Exciton energy transfer manipulation for efficient PeLEDs

Green PeLEDs with structures of ITO/TFB:PVK/control perovskite/1,3,5-tris(1-phenyl-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)benzene (TPBI)/lithium fluoride (LiF)/aluminum (Al) (Device A), ITO/TFB:PVK/MeS-treated perovskite/TPBI/LiF/Al (Device B), ITO/TFB:PVK/PVP/MeS-treated perovskite/TPBI/LiF/Al (Device C), and ITO/TFB:PVK/PVP/control perovskite/TPBI/LiF/Al (Device D) have been fabricated and compared. In the cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image (Fig. 5a), each of the functional layers in Device C (except for the ultrathin, ~4 nm PVP film) can be clearly seen. The device energy band diagram is plotted in Fig. 5b, based on energy level values for this perovskite film as obtained by ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) coupled with optical measurements (Supplementary Fig. 11). Note that the presence of an ultrathin layer of PVP on top of the TFB:PVK mixed HTL plays an important role in improving film quality and ensuing better device performance (Supplementary Fig. 12). It not only enables the deposition of smooth and dense perovskite films due to the significantly improved HTL surface wettability (Supplementary Fig. 13), but also suppresses the emission quenching by suppressing charge transfer at the perovskite/HTL interface57,58 (Supplementary Fig. 14). In the absence of PVP (in both cases), Device B shows an almost two-fold performance enhancement compared to the Device A (13.14% EQE & 10,140 cd m−2 luminance vs. 6.37% EQE & 6094 cd m−2 luminance, respectively. Supplementary Fig. 15 and Supplementary Table 3).

a Cross-sectional SEM image of a PeLED with a structure of ITO/TFB:PVK (25 nm)/PVP (4 nm)/perovskite (50 nm)/TPBI (35 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (100 nm), and b its schematic energy band diagram. Except for the perovskite layer which is directly measured, the energy level values for the other functional layers are taken from Lu et al.11. c Normalized PL spectrum of the 8%-MeS film, and EL spectrum of the PeLEDs at an applied voltage of 5.5 V. d J–V–L, e CE–J–EQE curves of the best-performing 8%-MeS-treated PeLED, and f histogram of the maximum EQEs measured on 20 such devices.

Figure 5c–f shows the performance characteristics of our best green PeLED with MeS-treated perovskite and PVP interlayer (Device C). The EL spectrum matches well with the PL spectrum (Fig. 5c), and the EL emission peak (at 512 nm) is only slightly blueshifted and broadened. The blueshift most probably results from free carrier emission, as already demonstrated in several perovskite systems59,60,61; and the broadened EL can be attributed to the electric-field-induced Stark effect2,62. From the current density–luminance–voltage (J–V–L) curves (Fig. 5d), we can see that the current density rapidly increased after reaching the turn-on voltage (~2.8 V) due to efficient carrier injection into the perovskite emission layer. As the current density continued to increase, the device had a peak luminance of 13,400 cd m−2 at a low applied voltage of 5.5 V, and a high CE of 63 cd A−1 corresponding to an EQE of 20.5% at a current density of ~1 mA cm−2, which is, to the best of our knowledge, a record efficiency in quasi-2D PeLEDs for all colors (Supplementary Table 4 compares our results with recently reported values in the literature). A histogram of the maximum EQE values for 20 devices (Fig. 5f) shows an average EQE of 17.1% with a relative standard deviation of 10%, indicating good device-to-device reproducibility. Furthermore, due to the reduced ion migration pathways in the MeS-treated perovskite films, the device stability becomes remarkably improved as well, so that the Device C shows a two-fold operational lifetime enhancement compared with the Device D (Supplementary Fig. 16).

Discussion

We achieved a record efficiency (CE of 63 cd A−1 and EQE of 20.5%) for quasi-2D BA2Csn−1PbnBr3n+1 PeLEDs by introducing MeS into the perovskite precursor solutions to reconstruct the perovskite phase distribution and reduce uncoordinated Pb2+ ions, and thus enhance the emission efficiency of perovskite films derived from these solutions. The proportion of large-n phases with narrow bandgap has increased in the distribution phases of different n values of quasi-2D perovskites due to hydrogen-bonding interaction between -SO3− group of MeS and BA spacer; and the surface uncoordinated Pb2+ ions on the perovskites were simultaneously reduced benefiting from the electron-rich Lewis base nature of MeS. Besides, the blocking effect of BA which tends to induce defects during crystal growth could be reduced because of the interaction between BA and MeS. This work offers a promising approach for fabricating next-generation high-performance PeLEDs based on quasi-2D perovskites.

Methods

Materials

CsBr (99.999%, metal basis) and PbBr2 (99.999%, metal basis) were purchased from Alfa Aesar. BABr was purchased from Xi’an Polymer Light Technology Corp. CsMeS, PVK, PVP, PEO, and DMSO (99.9%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. TFB, TPBI, and LiF were purchased from Luminescence Technology Corp. Absolute ethyl alcohol and toluene were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.

Perovskite precursor solutions

PbBr2, CsBr, and BABr were dissolved in anhydrous DMSO with the ratio of 1:1.2:0.4, and PEO (3.33 mg ml−1) was added to improve the morphology of the resulting film63,64,65. CsMeS was added into the precursor solution, with its molar ratios to PbBr2 being 6%, 8%, and 10%, respectively. The mixture was stirred at 60 °C overnight and filtered through a 0.45 μm polytetrafluoroethylene membrane before using.

Device Fabrication

ITO substrates were sonicated in sequence with detergent, deionized water, acetone, and isopropyl alcohol for 20 min, respectively, and then dried under nitrogen flow. TFB and PVK were mixed in a weight ratio of 4:6 and dissolved in chlorobenzene (10 mg ml−1). A TFB:PVK layer was spin-coated onto oxygen-plasma-treated ITO substrates at 4000 rpm for 40 s, followed by annealing at 150 °C for 20 min. PVP (1.5 mg ml−1 in absolute ethyl alcohol) was spin-coated on top of the TFB:PVK layer. For the perovskite film, the precursor solution was spin-coated at 4000 rpm for 50 s—after spin coating for 40 s, 100 µl toluene antisolvent was dropped onto the film and spin coating continued for a further 10 s—followed by baking at 80 °C for 10 min. After that, TPBI (40 nm), LiF (1 nm), and Al electrode (100 nm) layers were sequentially deposited by thermal evaporation under a vacuum of ~4 × 10−4 Pa.

Characterization

XRD patterns were collected on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation as the X-ray source, ranging from 5° to 60° at a scanning rate of 6° min−1. UV-Vis spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 950 UV-Vis-NIR spectrometer. TA measurements were carried out on a Helios pump-probe system (Ultrafast Systems LLC) with a 365-nm laser (0.17 mW). XPS and UPS spectra were acquired using a Thermo Scientific Escalab 250Xi. He (I) ultraviolet radiation source (21.22 eV) from a He discharge lamp was used in the UPS measurements. The work functions (WFs) and the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) regions were extracted from the UPS spectra using the equations WF = 21.22 − Ecutoff and HOMO = WF + Eonset. The Ecutoff and the Eonset were determined by the intercepts of the tangents of the peaks with the extrapolated baselines, as depicted in the relevant plots. Steady-state PL spectra and TRPL were recorded on an Edinburgh FLS920 PL spectrometer at an excitation wavelength of 365 nm. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Advanced II (400 MHz) spectrometer at room temperature. The grazing-incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS) data were obtained at beamline BL14B1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), China. A monochromatic beam of λ = 0.6887 Å was used, and the incident angle was 0.1°. The EL characteristics of the PeLEDs were collected on a system comprised of a PR-670 Spectra Scan Spectroradiometer coupled with a Keithley 2400 sourcemeter. The EQEs were calculated from the luminance, the current density, and the EL emission spectra of devices. All the device characterization tests were carried out on unencapsulated PeLEDs at room temperature in ambient air, except that the operational stability test was carried in an N2-filled glovebox.

DFT simulations

The reaction Gibbs free energy ΔG for the reaction, CsMeS + BABr = BAMeS + CsBr, was approximated by the change of ground-state energy at 0 K: \(\Delta G \approx E_{{\mathrm{BAMeS}}} + E_{{\mathrm{CsBr}}} - E_{{\mathrm{BABr}}} - E_{{\mathrm{CsMeS}}}\). The ground-state energy was calculated using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulations Package (VASP) and projected augmented wave (PAW) method with 1s1, 2s22p2, 2s22p3, 2s22p4, 3s23p4, 4s24p5, 5s25p66s1, and 6s26p2 as valence electrons for H, C, N, O, S, Br, Cs, and Pb, respectively. The exchange-correlation interaction was treated with the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) parameterized by a Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE) functional. The Brillouin zone was sampled by using a Gamma point for molecules and a Gamma-cantered k-mesh of 9 × 9 × 9 for CsBr. The cutoff energy of the plane-wave basis was chosen to converge the energy to 1 meV atom−1. The force was converged to less than 0.01 eV Å−1 for all structure relaxations. The calculated ground-state energies are −90.935, −46.738, −133.728, and −6.107 eV for BABr, CsMeS, BAMeS, and CsBr, respectively. The reaction free energy is therefore −2.16 eV.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and the other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Liu, Y. et al. Efficient blue light-emitting diodes based on quantum-confined bromide perovskite nanostructures. Nat. Photonics 13, 760–764 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Trifluoroacetate induced small-grained CsPbBr3 perovskite films result in efficient and stable light emitting devices. Nat. Commun. 10, 665 (2019).

Kumar, S. et al. Ultrapure green light-emitting diodes using two-dimensional formamidinium perovskites: achieving recommendation 2020 color coordinates. Nano Lett. 17, 5277–5284 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Perovskite-molecule composite thin films for efficient and stable light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 11, 891 (2020).

Shi, Z. et al. Uncovering the mechanism behind the improved stability of 2D organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites. Small 15, 1900462 (2019).

Deng, S. et al. Long-range exciton transport and slow annihilation in two-dimensional hybrid perovskites. Nat. Commun. 11, 664 (2020).

Adjokatse, S., Fang, H.-H. & Loi, M. A. Broadly tunable metal halide perovskites for solid-state light-emission applications. Mater. Today 20, 413–424 (2017).

Lu, J.-H., Yu, Y.-L., Chuang, S.-R., Yeh, C.-H. & Chen, C.-P. High-performance, semitransparent, easily tunable vivid colorful perovskite photovoltaics featuring Ag/ITO/Ag microcavity structures. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 4233–4239 (2016).

Wang, Q. et al. Efficient sky-blue perovskite light-emitting diodes via photoluminescence enhancement. Nat. Commun. 10, 5633 (2019).

Jiang, Y. et al. Spectra stable blue perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 10, 1868 (2019).

Lu, M. et al. Metal halide perovskite light‐emitting devices: promising technology for next‐generation displays. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1902008 (2019).

Zhao, L., Lee, K. M., Roh, K., Khan, S. U. Z., & Rand, B. P. Improved outcoupling efficiency and stability of perovskite light‐emitting diodes using thin emitting layers. Adv. Mater. 31, 1805836 (2019).

Yuan, Z. et al. Unveiling the synergistic effect of precursor stoichiometry and interfacial reactions for perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 10, 2818 (2019).

Cao, Y. et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes based on spontaneously formed submicrometre-scale structures. Nature 562, 249–253 (2018).

Xu, W. et al. Rational molecular passivation for high-performance perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photonics 13, 418–424 (2019).

Lin, K. et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 20 percent. Nature 562, 245–248 (2018).

Wu, T. et al. High-performance perovskite light-emitting diode with enhanced operational stability using lithium halide passivation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 4099–4105 (2020).

Shen, H. et al. Visible quantum dot light-emitting diodes with simultaneous high brightness and efficiency. Nat. Photonics 13, 192–197 (2019).

Song, J. et al. Over 30% external quantum efficiency light‐emitting diodes by engineering quantum dot‐assisted energy level match for hole transport layer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1808377 (2019).

Rajamalli, P. et al. A new molecular design based on thermally activated delayed fluorescence for highly efficient organic light emitting diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 628–634 (2016).

Tan, Z.-K. et al. Bright light-emitting diodes based on organometal halide perovskite. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 687–692 (2014).

Xiao, Z. et al. Efficient perovskite light-emitting diodes featuring nanometre-sized crystallites. Nat. Photonics 11, 108–115 (2017).

Liu, T. et al. Tailoring vertical phase distribution of quasi-two-dimensional perovskite films via surface modification of hole-transporting layer. Nat. Commun. 10, 878 (2019).

Zhou, N. et al. Exploration of crystallization kinetics in quasi two-dimensional perovskite and high performance solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 459–465 (2017).

Cheng, L. et al. Multiple‐quantum‐well perovskites for high‐performance light‐emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 32, 1904163 (2019).

Lin, Y. et al. Suppressed ion migration in low-dimensional perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1571–1572 (2017).

Li, C. et al. Understanding the improvement in the stability of a self-assembled multiple-quantum well perovskite light-emitting diode. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 6857–6864 (2019).

Yang, X. et al. Efficient green light-emitting diodes based on quasi-two-dimensional composition and phase engineered perovskite with surface passivation. Nat. Commun. 9, 570 (2018).

Ban, M. et al. Solution-processed perovskite light emitting diodes with efficiency exceeding 15% through additive-controlled nanostructure tailoring. Nat. Commun. 9, 3892 (2018).

Leng, M. et al. Surface passivation of bismuth-based perovskite variant quantum dots to achieve efficient blue emission. Nano Lett. 18, 6076–6083 (2018).

Yin, W.-J., Yang, J.-H., Kang, J., Yan, Y. & Wei, S.-H. Halide perovskite materials for solar cells: a theoretical review. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 8926–8942 (2015).

Kim, J., Chung, C.-H. & Hong, K.-H. Understanding of the formation of shallow level defects from the intrinsic defects of lead tri-halide perovskites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 27143–27147 (2016).

Sapori, D. et al. Quantum confinement and dielectric profiles of colloidal nanoplatelets of halide inorganic and hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites. Nanoscale 8, 6369–6378 (2016).

Xia, P. et al. A pre-solution mixing precursor method for improving crystallization quality of perovskite film and electroluminescent performance of perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nanoscale 11, 20847–20856 (2019).

Quan, L. N. et al. Ligand-stabilized reduced-dimensionality perovskites. J. Am. Chen. Soc. 138, 2649–2655 (2016).

Du, J. et al. Ionic liquid‐assisted improvements in the thermal stability of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite photovoltaics. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 12, 1800130 (2018).

Yuan, S. et al. Optimization of low‐dimensional components of quasi‐2D perovskite films for deep‐blue light‐emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 31, 1904319 (2019).

Quan, L. N. et al. Tailoring the energy landscape in quasi-2D halide perovskites enables efficient green-light emission. Nano Lett. 17, 3701–3709 (2017).

Yuan, M. et al. Perovskite energy funnels for efficient light-emitting diodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 872–877 (2016).

Liu, J., Leng, J., Wu, K., Zhang, J. & Jin, S. Observation of internal photoinduced electron and hole separation in hybrid two-dimensional perovskite films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1432–1435 (2017).

Cohen, B.-E., Wierzbowska, M. & Etgar, L. High efficiency quasi 2D lead bromide perovskite solar cells using various barrier molecules. Sustain. Energy Fuels 1, 1935–1943 (2017).

Lei, L. et al. Effcient energy funneling in quasi-2D perovskites: from light emission to lasing. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906571 (2020).

Cho, H. et al. Overcoming the electroluminescence efficiency limitations of perovskite light-emitting diodes. Science 350, 1222–1225 (2015).

Ren, Z. et al. Hole transport bilayer structure for quasi‐2D perovskite based blue light‐emitting diodes with high brightness and good spectral stability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1905339 (2019).

Xing, G. et al. Transcending the slow bimolecular recombination in lead-halide perovskites for electroluminescence. Nat. Commun. 8, 14558 (2017).

Zhou, W. et al. Zwitterion coordination induced highly orientational order of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite film delivers a high open circuit voltage exceeding 1.2 V. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1901026 (2019).

Wang, Q. et al. Stabilizing the α-phase of CsPbI3 perovskite by sulfobetaine zwitterions in one-step spin-coating films. Joule 1, 371–382 (2017).

Deepa, M., Sharma, N., Agnihotry, S. A. & Chandra, R. FTIR investigations on ion-ion interactions in liquid and gel polymeric electrolytes: LiCF3SO3-PC-PMMA. J. Mater. Sci. 37, 1759–1765 (2002).

Han, M. G. & Im, S. S. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy study of electrically conducting polyaniline/polyimide blends. Polymer 41, 3253–3262 (2000).

Li, B. et al. Anchoring fullerene onto perovskite film via grafting pyridine toward enhanced electron transport in high-efficiency solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 32471–32482 (2018).

Chen, D., Gallagher, M. J. & Sarid, D. Scanning tunneling microscopy study of the adsorption of C60 molecules on Si (100)‐(2 × 1) surfaces. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 12, 1947–1951 (1994).

Taubert, A., Kübel, C. & Martin, D. C. Polymer-induced microstructure variation in zinc oxide crystals precipitated from aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 2660–2666 (2003).

Duan, C. et al. Engineering new defects in MIL-100 (Fe) via a mixed-ligand approach to effect enhanced volatile organic compound adsorption capacity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 774–782 (2019).

Shen, X. et al. Zn-alloyed CsPbI3 nanocrystals for highly efficient perovskite light-emitting devices. Nano Lett. 19, 1552–1559 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Stable triple cation perovskite precursor for highly efficient perovskite solar cells enabled by interaction with 18C6 stabilizer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908613 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Molecule‐induced p‐doping in perovskite nanocrystals enables efficient color‐saturated red light‐emitting diodes. Small 16, 2001062 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Enhancing the brightness of cesium lead halide perovskite nanocrystal based green light-emitting devices through the interface engineering with perfluorinated ionomer. Nano Lett. 16, 1415–1420 (2016).

Pal, B. N. et al. ‘Giant’ CdSe/CdS core/shell nanocrystal quantum dots as efficient electroluminescent materials: strong influence of shell thickness on light-emitting diode performance. Nano Lett. 12, 331–336 (2012).

Zhang, L. et al. Ultra-bright and highly efficient inorganic based perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 8, 15640 (2017).

Palma, A. L. et al. Mesoscopic perovskite light-emitting diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 26989–26997 (2016).

D’Innocenzo, V. et al. Excitons versus free charges in organo-lead tri-halide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 5, 3586 (2014).

Yang, X. et al. Electroluminescence efficiency enhancement in quantum dot light‐emitting diodes by embedding a silver nanoisland layer. Adv. Opt. Mater. 3, 1439–1445 (2015).

Jeong, B. et al. All-inorganic CsPbI3 perovskite phase-stabilized by poly (ethylene oxide) for red-light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1706401 (2018).

Tian, Y. et al. Highly efficient spectrally stable red perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 30, 1707093 (2018).

Wu, C. et al. Improved performance and stability of all-inorganic perovskite light-emitting diodes by antisolvent vapor treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1700338 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51675322, 61605109, 61735004, 51702115, and 51972136), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFB0401702), and the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (No. 19010500600). We thank the staff from BL01B1, BL11B, BL17B1 and BL19U1 beamlines of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for assistance during data collection. A.R. also thanks the financial support from the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong (CRF C7035-20G) and the Croucher Foundation of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y. and A.L.R. designed and directed the study. L.K. and H.W. contributed to LED device fabrication. Y.J. carried out the TA measurements and analysis. Y.L. performed the DFT simulations. L.K., X.Z., Y.L., H.W., S.W., M.Y., C.Z., T.Z., S.V.K., W.Z., Y.Y., Q.L., M.Y., A.L.R., and X.Y. analyzed and discussed the experimental results. L.K., X.Z., and Y.L. contributed equally to this work. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Jianpu Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, L., Zhang, X., Li, Y. et al. Smoothing the energy transfer pathway in quasi-2D perovskite films using methanesulfonate leads to highly efficient light-emitting devices. Nat Commun 12, 1246 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21522-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21522-8

This article is cited by

-

Phase dimensions resolving of efficient and stable perovskite light-emitting diodes at high brightness

Nature Photonics (2024)

-

Phase distribution management in quasi-2D perovskite films toward highly efficient amplified spontaneous emission pumped by nanosecond pulsed laser

Science China Materials (2024)

-

Efficient blue electroluminescence from reduced-dimensional perovskites

Nature Photonics (2024)

-

Rational adjustment to interfacial interaction with carbonized polymer dots enabling efficient large-area perovskite light-emitting diodes

Light: Science & Applications (2023)

-

Efficient all-thermally evaporated perovskite light-emitting diodes for active-matrix displays

Nature Photonics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.