Abstract

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a problematic greenhouse gas, although its conversion to alternative fuels represents a promising approach to limit its long-term effects. Here, pyroelectric nanostructured materials are shown to utilize temperature-variations and to reduce CO2 for methanol. Layered perovskite bismuth tungstate nanoplates harvest heat energy from temperature-variation, driving pyroelectric catalytic CO2 reduction for methanol at temperatures between 15 °C and 70 °C. The methanol yield can be as high as 55.0 μmol⋅g−1 after experiencing 20 cycles of temperature-variation. This efficient, cost-effective, and environmental-friendly pyroelectric catalytic CO2 reduction route provides an avenue towards utilizing natural diurnal temperature-variation for future methanol economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For hundreds of years, fossil fuels have been the main energy source for human activities and industrial manufacture. With the development of human society, the decrease in fossil energy and the increase of CO2 concentration have aroused great attention. For instance, energy crisis, greenhouse effect and ocean acidification are some of the main problems facing humanity1,2,3. Converting CO2 into hydrocarbon fuels is considered as one of the ideal solutions, which can solve not only the environmental problems but also the high requirements of energy consumption. Various methods have been explored to convert CO2 to organic fuels, such as photocatalytic reduction, electrocatalytic reduction, biological transformation, hydrogenation, and dry reforming4,5,6,7. Nevertheless, hydrogenation of CO2 to form CH3OH process requires high operating temperatures (200–250 °C) and high pressures (5–10 MPa), which limit the yield of methanol8. As a matter of fact, photocatalytic reduction of CO2 can be carried out at mild temperature and pressure, but it does not work in dark9.

Temperature variation is a recurring phenomenon in our daily life10. It would be meaningful to harvest such abundant energy source during temperature variation. Such a motive is reasonable because pyroelectric materials can convert heat energy into electric energy via repeating cooling or heating process11,12,13. Pyroelectric materials can produce positive and negative electric charges during temperature variation. The free charges generated through pyroelectric process can be applied to catalytic processes such as dye decomposition14,15,16 and water splitting17,18. Theoretical calculation shows that a pyroelectric engine in an ideal condition can reach an energy conversion efficiency as high as 84–92%, which is much higher than the photovoltaic energy conversion efficiency typically in the range of 20%19,20. Theoretically, Kakekhani et al.21 have proved the feasibility of pyroelectric catalytic water splitting. However, to our best knowledge, there is no report about collecting the energy using pyroelectric materials from temperature variation for CO2 reduction.

The catalytic performance of ferroelectrics has been studied for 70 years. For example, the internal fields from the polarization of the ferroelectrics can separate electrons and holes, thus enhancing the catalytic efficiency17. Ferroelectric polarization can affect molecular adsorption and desorption from the surface of the materials21. It is well known that all ferroelectric materials are pyroelectric materials. As the simplest member of bismuth layer-structured Aurivillius phase, bismuth tungstate (Bi2WO6) exhibits good ferroelectric and pyroelectric properties. Meanwhile, Bi2WO6 has some other interesting properties such as high ion conductivity, large spontaneous polarization (P ≅ 50 µC cm−2), high Curie temperature (TC = 950 °C), and photocatalytic property22,23. As Bi2WO6 is constructed by alternating (Bi2O2)2+ and (WO4)2− layers, such a layered structure enables high thermal and chemical stabilities24. More importantly, the suitable energy band structure and surface properties of Bi2WO6 allow it for CO2 reduction into renewable hydrocarbon fuel25,26. In this work, through pyroelectric catalysis, CO2 is reduced to CH3OH at temperature variation below 100 °C. The efficiency has reached as high as 55.0 µmol g−1 after experiencing 20 cycles between 15 °C and 70 °C. Our experimental work provides a new route to CO2 reduction for methanol through a pyroelectric catalytic process, which can be carried out near room temperature.

Results and discussion

Characterization of Bi2WO6

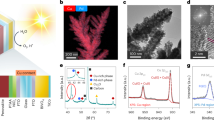

Previous study shows that Bi2WO6 is ferroelectric with an orthorhombic structure27. Bi2WO6 nanoplates were synthesized by hydrothermal process in this work (see the experimental details in the section of Methods). In order to identify the phase of the synthesized Bi2WO6, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed at room temperature. As shown in Fig. 1a, all the diffraction peaks can be assigned to Bi2WO6 according to the standard JCPDS card No. 79-2381 (space group: Pca21; point group: mm2; orthorhombic crystal system).

It can be seen from Fig. 1b that the synthesized Bi2WO6 has a plate-like morphology with an average size of 250 nm. Figure 1c presents the image of Bi2WO6 from transmission electron microscopy (TEM), where the nanoplate has the similar feature size as the ones of scanning electron microscope (SEM) images in Fig. 1b. The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image of Bi2WO6 is shown in Fig. 1d. It clearly shows the single-crystalline nature of Bi2WO6 nanoplate with a lattice plane intervals of 0.27 nm, corresponding to the (002)/(200) plane, respectively. The aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image of Bi2WO6 sample is presented in Fig. 1e. The light/dark gray contrast spots correspond to Bi (Z = 83, where Z is the atomic number) and W (Z = 74) atom columns, respectively. The inset image denotes the fast Fourier transformation (FFT) of the STEM image. The FFT image shows the zone axis of the STEM image is [103], which is perpendicular to b direction. Therefore, the STEM image reflects the layered structure of Bi2WO6, which is sandwiched by alternating perovskite-like (WO4)2− and fluorite-like (Bi2O2)2+ blocks. A comparison between the STEM image and the structure model is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1f. The left picture in Fig. 1f is the magnified image of the area marked in a red rectangle in Fig. 1e. The inset in Fig. 1e shows the simulated diffraction pattern in the [103] projection direction. Complete structure model is shown on the right side of Fig. 1f.

Bi2WO6 is paraelectric with a high-symmetry body-centered tetragonal structure (space group symmetry I4/mmm) at high temperature. When the temperature drops, symmetry of the crystal structure will be broken, and the distortion of the symmetry tetragonal structure makes Bi2WO6 generate ferroelectric properties. This mainly includes two aspects. First, the ions displace along the [110] axis of the tetragonal structure. Secondly, the WO6 octahedra rotates around the a and c axes28. In order to characterize the ferroelectric properties of the as-synthesized Bi2WO6 nanoplates, ferroelectric domains of Bi2WO6 nanoplates are observed using a piezoelectric force microscope (PFM) at a slow scanning frequency of 1 Hz with an area of 0.8 × 0.8 μm2. The nanoplates’ morphologies of Bi2WO6 in Fig. 2a are consistent with the results of TEM and SEM. Figure 2b, c show the vertical piezoresponse amplitude and phase image, respectively. The distinct contrast in the images illustrates the different polarization in the Bi2WO6 nanoplates. Figure 2d, e display the local piezoelectric hysteresis loops of the Bi2WO6, including both “off” state (piezoelectric displacement contribution only) and “on” state (both the piezoelectric contribution and the displacement resulted from electrostatic interaction). The phase angles at “off” and “on” states change about 150° under 60 V DC bias field, confirming the occurrence of a local polarization switching under an electric field. The butterfly-shaped hysteresis loop further verifies the local ferro-/piezoelectric response of Bi2WO6 nanoplate.

It is noted that Bi2WO6 also shows pyroelectric properties, where imbalanced polarization charges can generate electric field when the material undergoes temperature variation. The voltage produced by pyroelectric effect can be driving force for electrochemical reactions. Figure S1 shows the pyro-potential distribution across a Bi2WO6 nanoplate fitted by COMSOL finite element simulation, in which different colors represent different potentials. It can be seen that potential difference occurs on the surfaces of the Bi2WO6 nanoplates. In general, ferroelectric materials have greater pyroelectric and piezoelectric coefficients than non-ferroelectrics28. In order to demonstrate Bi2WO6 generate free charges through temperature variation, pyro-current response of Bi2WO6 nanoplates is measured. Once the temperature of the pyroelectric material changes, the pyroelectric charges can be generated quickly due to the pyroelectric effect. The pyroelectric current can be expressed by Eq. (1),

where I and p are the pyroelectric current and the pyroelectric coefficient of Bi2WO6, respectively. A is the area of electrode. dT/dt is the rate of temperature fluctuation. Therefore, the pyroelectric current is proportional to dT/dt, any temperature change of the pyroelectric material will cause it to generate free charges. Figure 2f, g show the current change generated by Bi2WO6 nanoplates with the infrared signal. Under infrared radiation, a sharp increase of current density is induced by the pyroelectric effect due to the rapid increase of temperature within Bi2WO6 nanoplates. The current density decays slowly due to the decrease of temperature change rate, and maintains at a steady value under the equilibrium condition. When the infrared radiation is turned off, due to the instantaneous temperature decrease (dT/dt < 0), the redistribution of the pyroelectric charges will produce a reverse current. The output current returns to zero while there is no temperature change and infrared radiation. To clarify the temperature effect, we further use xenon lamp (UV light) instead of the infrared radiation to illuminate the sample. There is no pyro-current signal generate, which further confirms that Bi2WO6 generates free charge under temperature variation(see Fig. S2).

Pyroelectric catalytic activity of Bi2WO6

In order to evaluate the pyroelectric catalytic activity of Bi2WO6, CO2 reduction test was carried out under the condition of temperature variation. As shown in Fig. 3a, the methanol yield increases with the increasing thermal cycles. The total methanol yield reaches 20.5 µmol g−1 without adding any sacrificial agent after 20 thermal cycles. 1H NMR in Fig. S3 also demonstrates that no other products can be detected in the liquid phase. Meanwhile, the analyses of gaseous products in Fig. S4 show only a small amount of CH4 and CO (0.11 µmol g−1 and 0.20 µmol g−1, respectively), indicating high selectivity of Bi2WO6 pyroelectric catalytic CO2 reduction to CH3OH. The oxygen production detection is shown in Fig. S5, the amount of O2 is roughly 1.5 times the amount of methanol. It has been similarly reported that the photocatalytic process works due to the recombination of electrons and holes. Such a process will significantly affect the catalytic efficiency29,30. To reduce the occurrence of electrons recombination with holes, sacrificial agents are usually added to the reaction system. Figure 3b shows that more methanol can be generated by using Na2SO3 as negative charge sacrificial agent. The methanol yield can be as high as 55.0 µmol g−1 after 20 temperature-variation cycles, which is 2.5 times more than that without Na2SO3. The range of temperature variation can also affect the pyroelectric catalytic CO2 reduction. Figure S6 shows the yield of methanol after 10 thermal cycles in different temperature ranges (15–40 °C, 15–50 °C, 15–70 °C, 15–85 °C). In Fig. S6, the methanol yield increases as the temperature range increases. The pyro-induced charges (dQ) can be expressed in Eq. (2)

a Methanol yield through pyroelectric catalytic CO2 conversion without Na2SO3, and b with Na2SO3 as sacrificial agent. c The fluorescence spectra of 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid, d the absorption spectra of diformazan and monoformazan. e 1H NMR spectra of the pyroelectric catalytic reaction solution with unlabeled CO2 and f 1H NMR spectra of the pyroelectric catalytic reaction solution with labeled 13CO2.

A larger temperature range can generate more pyro-charges, leading to better pyroelectric catalytic results. It is also noted that the Bi2WO6 nanoplates maintain their crystal structure and morphology after pyroelectric catalytic reduction as confirmed by the XRD analysis and SEM characterization (see Fig. S7). To further prove that CO2 reduction comes from pyroelectric catalysis, experiment without Bi2WO6 nanoplates is performed, the result in Fig. S8a shows that no methanol or other products can be detected under temperature variation without Bi2WO6 nanoplates. Furthermore, no methanol or other products can be detected when the test is carried out with the presence of Bi2WO6 nanoplates for 10 h at temperatures of 15 °C, 45 °C and 70 °C, respectively (Fig. S8b). CO2 is a linear molecule, which is one of the most thermodynamically stable carbon compounds, it’s hard to break the bonding of C=O8,31.

Pyroelectric charges can react with O2 and OH− in water to form \({\mathrm{O}}_2^{ \cdot - }\) and \(\cdot {\mathrm{OH}}\). Such reactions can be expressed as shown in Eqs. (3)–(5).

To have a better understanding of the pyroelectric catalysis, \({\mathrm{O}}_2^{ \cdot - }\) and \(\cdot {\mathrm{OH}}\) detections are performed. Experimentally, the \(\cdot {\mathrm{OH}}\) can be detected by fluorescence spectrometry using terephthalic acid as a photoluminescent \(\cdot {\mathrm{OH}}\) trapping agent. The \({\mathrm{O}}_2^{ \cdot - }\) can be detected by UV–Vis spectrophotometer since \({\mathrm{O}}_2^{ \cdot - }\) can react with nitro-blue tetrazolium (BNT) to produce diformazan and monoformazan. As shown in Fig. 3c, significant fluorescence emission at ~425 nm associated with 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid is observed upon the temperature-variation cycles. The gradual increase of luminescence intensity with temperature-variation cycles indicates the formation of \(\cdot {\mathrm{OH}}\). Figure 3d presents the absorption spectra of diformazan and monoformazan, which are produced by BNT reacted with \({\mathrm{O}}_2^{ \cdot - }\). The increase of peak absorption at ~630 nm and 720 nm with the temperature-variation cycles indicates the formation of \({\mathrm{O}}_2^{ \cdot - }\)32. The electron spin resonance characterization in Fig. S9 can further prove \({\mathrm{O}}_2^{ \cdot - }\) and \(\cdot {\mathrm{OH}}\) generated through temperature variation. \({\mathrm{O}}_2^{ \cdot - }\) and \(\cdot {\mathrm{OH}}\) are considered to be the main active species in dye decomposition33. Except for the pyroelectric catalysis of CO2 reduction, we further performed RhB pyroelectric catalytic decomposition experiment to fully demonstrate the pyroelectric catalytic activities of Bi2WO6. In fact, RhB pyroelectric catalytic decomposition is a visual evidence to prove the redox ability of pyroelectric charges. Accordingly, Rhodamine B (RhB) solution (5 mg L−1) is used to demonstrate the pyroelectric catalytic dye decomposition of Bi2WO6 in Fig. S10a, b. In order to prove that methanol is the product of CO2 reduction, we manage the isotopic labeling experiment using 13CO2 as feedstock. To avoid 12CO2, we have done the additional experimental using NaOH instead of NaHCO3. The 1H NMR spectrum of the reaction solution (Fig. 3e) clearly shows the formation of methanol (δ = 3.34 ppm) when the unlabeled CO2 is used as feedstock. While using 13CO2 instead of CO2, the 1H NMR spectrum of the reaction solution in Fig. 3f shows doublet peaks between 3.7 and 3.0 ppm, which is attributed to the proton coupled with the 13C of 13CH3OH34. The results directly indicate that CO2 is the carbon source for the pyroelectric catalytic CO2 reduction into CH3OH. The time course change of the intensity is shown in Fig. S11.

Theoretical calculation of CO2 reduction reaction path

To better illustrate the reaction mechanism for the CO2 reduction, we employ first-principles calculations with SIESTA package, which is based on density functional theory (DFT)35. The pseudopotentials are constructed by the Troullier-Martins scheme36.The Ceperley–Alder exchange-correlation functional as parameterized by Perdew and Zunger is employed for the local density approximation (LDA)37,38. In all calculations, the double-ζ plus polarization basis sets are chosen for all atoms. The atomic structures are fully relaxed using the conjugated gradient method until the Hellman–Feynman force on each atom is smaller than 0.02 eV Å−1. Since Bi2WO6 consists of alternative (WO4)2− and (Bi2O2)2+ layers as discussed above, a slab model is constructed for the Bi2WO6(001) surface. The top of the slab is terminated by the WO square network, and the bottom of the slab is saturated by H atoms, as shown in Fig. S12. It is known that oxygen vacancies commonly exist in oxide semiconductors39. However, it is found that the formation energy of an oxygen vacancy in Bi2WO6(001) is as large as 3.2 eV, which indicates that the density of oxygen vacancies in Bi2WO6(001) is ignorable. To explore the possible process of the CO2 reduction, it is necessary to figure out the ground-state adsorption configuration of the CO2 molecule on Bi2WO6(001). Figure 4a shows five different adsorption configurations for CO2. The lowest adsorption energy is −3.6 eV, which implies that the CO2 molecule is strongly bound to Bi2WO6(001). In this case, the CO2 molecule is bent with one C–W bond (2.00 Å) and two O–W bonds (2.09 and 2.26 Å) as shown in Fig. 4b (step “0”), which is different from previous report9. The C–O bond lengths are elongated by 0.1 Å because of the interaction between CO2 and Bi2WO6 (001). The CO2 reduction starts when the hydrogen ions in the solvent interact with the CO2 molecule. Note that DFT calculations, the hydrogen atom as proton (H+) and electron (e−) cannot be separated directly. To model the reaction between H and radical on Bi2WO6(001), a H atom is placed beside a certain site of the radical and carried out DFT calculations to optimize the interaction between them. Electron charge transfer happens between the H atom and radical, usually from H to the radical so that the H atom finally becomes H+, according to the chemical bonding between H and the radical (e.g., CO2 molecule in this work). In other words, charge separation can be reached after self-consistent-field iterations. In addition, the gas phase of H is assumed because the solvent does not involve in the reaction of the CO2 reduction. The process of the CO2 reduction is divided into a series of steps and the reaction energies are calculated step by step. All possible structural configurations along with addition of one H ion are considered for each step simulation. For instance, from step “0” to step “1”, the H ion may bind to the CO2 molecule through C or O atom, or to the Bi2WO6 (001) surface through W or O atoms, which results in different products. To determine the most possible reaction, the reaction energy of each product is estimated as: \({{\Delta }}E = E\left( n \right) - E\left( {n - 1} \right) - \mu _{\mathrm{H}}\), where \(E\left( n \right)\) is the total energy of a certain product at the nth step and \(\mu _{\mathrm{H}}\) is the chemical potential of H. After optimizing all structural configurations, the case with the lowest reaction energy at each step is plotted in Fig. 4b. Obviously, the structural configurations in Fig. 4b are the most possible products for each step. Further, Fig. 4c shows the reaction energy of the most possible product at each step. Here, the first three H ions at the first three steps prefer to bind to the C atom, and these reactions are exothermic due to the large negative reaction energies as seen in Fig. 4c. As a consequence, one C–O bond is broken, then a CH3O* radical and a separate O ion are produced at step “3”. Then the subsequent H ions will be attracted by the separated O ion until a H2O molecule forms (step “5”). However, the H2O molecule is not released from Bi2WO6 (001), because it requires a large activation energy of about 1.7 eV. Finally, a methanol (CH3OH) molecule is produced after one more H ion attaches to the CH3O* radical (step “6”). As shown in Fig. 4c, the first four reaction steps are exothermic while the last three are endothermic. In particular, an activation energy of 1.6 eV (equal to the reaction energy) is needed for the CH3OH molecule to be detached from the Bi2WO6(001) surface, i.e., from step “6” to step “7”. Note that CH3OH may also be produced at steps “4” and “5” (short dashed lines in Fig. 4c), but the corresponding activation energies are 1.77 and 1.87 eV, respectively, even larger than that for step “7”. Therefore, the possibility to produce CH3OH at steps “4” and “5” is very small, because the major reactions at the first two steps are exothermic. Nevertheless, the overall process of the CO2 reduction is still exothermic as shown in Fig. 4c, that is, the activation energies in the last three reaction steps can be compensated by the energy released in the first four steps. In principle, the CO2 reduction happens spontaneously. However, energy supply might be required while the energy loss in a solvent environment. This is the reason that the temperature is not high in our experiments. It is worth pointing out that, when the CH3OH molecule is detached from the Bi2WO6 (001) surface, the zero-point energy and enthalpy contribute to the free energy significantly40. Therefore, the reaction energies are also estimated through the free energies for CH3OH production indicated by the red lines in Fig. 4c. Interestingly, the activation energy of step “7” decreases to 0.95 eV, which implies that the reaction may happen at relatively high temperature, as found in our experiments.

a Five different adsorption configurations for CO2 on Bi2WO6. The red, gray, purple, and brown spheres stands for O, W, Bi, and C atoms. b Structures and c reaction energies for the CO2 reduction. Eight reaction steps are considered. The red, cyan, light gray, and dark gray spheres stand for O, W, H, and C atoms. Only the atoms around CO2 are highlighted. The reaction energies for the side product (methanol) at steps “4” and “5” are indicated by short dashed lines. The short red (dashed) lines are estimated from the free energies.

On the basis of the above analysis, the mechanism of pyroelectric catalytic CO2 reduction induced by temperature variation is proposed as shown in Fig. 5. When the temperature of Bi2WO6 remains stable, the internal spontaneous polarization is balanced with the external bound charges (Fig. 5a). It has been reported that the spontaneous polarization intensity of pyroelectric materials decreases as its temperature increases41. That is to say, the increase in temperature will reduce the polarization of the pyroelectric catalyst, thereby breaking the balance and generating free charges. The free negative charges react with adsorbed CO2 to form methanol and the free positive charges would be captured by Na2SO3 to form Na2SO4 (Fig. 5b). As a result, balance is established again between polarization and bonding charges (Fig. 5c). On the other hand, the decrease of temperature causes the increase of spontaneous polarization, and the equilibrium will be broken again, thus leading to opposite charges transfer and CO2 reduction process (Fig. 5d). Then the catalyst temperature returns to its original value and at the same time it returns to its original equilibrium. Therefore, the continuous thermal cycles will cause continuous CO2 reduction reaction.

a The temperature of catalyst remains constant, its spontaneous polarization in equilibrium with the bound charges. b The rapid rise in temperature broke the balance, and thus induce CO2 reduction reaction. c A new balance is established after the CO2 reduction reaction. d When the temperature drops, the opposite charges transfer, leading to a new CO2 reduction process.

In summary, this work introduces the use of pyroelectric materials to reduce CO2 to methanol driven by temperature variation. Experimental results show that the yield of methanol generation from CO2 can be as high as 55.0 µmol g−1 after 20 cycles of temperature variation. This efficient and environmentally friendly process based on the pyroelectric nanomaterial Bi2WO6 provides great potential for CO2 reduction in utilizing environmental heat energy near room temperature.

Methods

Materials

All used chemicals are analytic grade reagents without further purification. Bismuth nitrate (Bi(NO3)3·5H2O, AR), sodium tungstate (Na2WO4·2H2O, AR) and sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, AR), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, AR) were acquired from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Sodium sulfite (Na2SO3, AR was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. Carban dioxide (CO2, ≥99.995%) was purchased from Soochow Jinhong Co., Ltd. Deuterium oxide (D2O, ≥99.9%) was purchased from Qingdao Asfirst Science and trade Co., Ltd. 13CO2 was bought from Soochow changyou gas Co., Ltd with purity of 99.9%. Deionized water was employed throughout the whole experiments.

Preparation of Bi2WO6 nanoplates

Bi2WO6 nanoplates were synthesized through hydrothermal process. In a typical process, 485 mg of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O (1 mmol) and 165 mg of Na2WO4·2H2O (0.5 mmol) were added into the mixed solution. White precipitate appeared immediately in the solution. After being washed for several times, the collected precipitate was added into a 50 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and filled with deionized water up to 80% of the total volume. Then the autoclave was sealed into a stainless steel tank and kept at 433 K for 20 h. After reactions, the white as-prepared sample was centrifugated at 2400 × g and washed three times with deionized water. Finally, the collected products were dried in vacuum at 333 K for 12 h for further use.

Characterization

The crystal structure was test by an X-ray diffractomer (Philips PW3040/60, the Netherlands) with monochromatic Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å, 2θ = 20°−80°). The morphologies of the Bi2WO6 sample was characterized by a transmission electron microscope (TEM, Hitachi H-7650, Japan) and a field emission transmission electron microscopy (FETEM, Scios, USA) with an accelerated voltage of 200 kV. The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image was acquired through a field emission transmission electron microscopy (FEI Tecnai G2 F20 S-TWIN, USA) with the accelerated voltage of 200 kV. Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy image was obtained on a 300 kV aberration-corrected JEM-ARM300F. The piezoelectric property of the Bi2WO6 sample was characterized with piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM, MFP-3D, USA). Photoluminescence (PL) measurements were carried out with a Horiba spectrofluorometer (Fluoromax-4, France) in air. Pyro-current response was measured on a CHI 660E electrochemical workstation using a three-electrode cell. The UV–visible absorption spectra are recorded on a UV2501PC (Shimadzu, Japan).

Pyroelectric catalytic CO2 reduction activity test

In the pyroelectric catalytic CO2 conversion process, Bi2WO6 powder (40 mg) was suspended in 5 mL 0.2 M NaHCO3 solution in a 50 mL flask with the addition of 0.3 M Na2SO3 as sacrificial donor. High purity CO2 gas was bubbled into the flask for 10 min. Then the flask was immediately sealed with a rubber stopper. Then the flask was immediately sealed with a rubber stopper. The sample was suspended in the solution under magnetic stirring, being applied alternating temperature between 15 °C and 70 °C in water bath. The entire catalytic process is performed in dark. The detailed temperature profile and schematic diagram of the process can be found from Figs. S13 and S14, respectively. To detect the formation of methanol, 1 mL solution was fetched out and analyzed by using a gas chromatograph (Persee G5) equipped with a KB-5 column connected to a flame ionization detector. For the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) test, 800 μL reaction solution, 100 μL D2O and 50 μL DMSO (0.1% vol aqueous solution) were taken into nuclear magnetic tubes, and detected with an NMR spectrometer with superconducting magnet (AVANCE NEO 400 MHz, Switzerland).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

02 June 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23801-w

References

Wei, J. et al. Directly converting CO2 into a gasoline fuel. Nat. Commun. 8, 15174 (2017).

Zhang, L., Zhao, Z. J. & Gong, J. Nanostructured materials for heterogeneous electrocatalytic CO2 reduction and their related reaction mechanisms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 11326–11353 (2017).

Rodriguez, J. A. et al. Hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol: Importance of metal–oxide and metal–carbide interfaces in the activation of CO2. ACS Catal. 5, 6696–6706 (2015).

Bard, A. J. & Fox, M. A. Artificial photosynthesis-solar splitting of water to hydrogen and oxygen. Acc. Chem. Res. 28, 141–145 (1995).

Bai, S. et al. Highly active and selective hydrogenation of CO2 to ethanol by ordered Pd-Cu nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 6827–6830 (2017).

Lin, S. et al. Covalent organic frameworks comprising cobalt porphyrins for catalytic CO2 reduction in water. Science 349, 1208–1213 (2015).

Wu, J. et al. Efficient visible-light-driven CO2 reduction mediated by defect-engineered BiOBr atomic layers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 57, 8719–8723 (2018).

Du, X. L., Jiang, Z., Su, D. S. & Wang, J. Q. Research progress on the indirect hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to methanol. ChemSusChem 9, 322–332 (2016).

Tu, W., Zhou, Y. & Zou, Z. Photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into renewable hydrocarbon fuels: state-of-the-art accomplishment, challenges, and prospects. Adv. Mater. 26, 4607–4626 (2014).

Lang, S. B. & Muensit, S. Review of some lesser-known applications of piezoelectric and pyroelectric polymers. Appl. Phys. A 85, 125–134 (2006).

Pandya, S. et al. Pyroelectric energy conversion with large energy and power density in relaxor ferroelectric thin films. Nat. Mater. 17, 432–438 (2018).

Pandya, S. et al. New approach to waste-heat energy harvesting: pyroelectric energy conversion. NPG Asia Mater. 11, 26 (2019).

Wang, Q. et al. Hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets doped pyroelectric ceramic composite for high-performance thermal energy harvesting. Nano Energy 60, 144–152 (2019).

Xu, X. et al. Strong pyro-electro-chemical coupling of Ba0.7Sr0.3TiO3@Ag pyroelectric nanoparticles for room-temperature pyrocatalysis. Nano Energy 50, 581–588 (2018).

Wu, J. et al. Strong pyro-catalysis of pyroelectric BiFeO3 nanoparticles under a room-temperature cold-hot alternation. Nanoscale 8, 7343–7350 (2016).

Qian, W. et al. Thermo-electrochemical coupling for room temperature thermocatalysis in pyroelectric ZnO nanorods. Electrochem. Commun. 81, 124–127 (2017).

Xu, X. et al. Pyro-catalytic hydrogen evolution by Ba0.7Sr0.3TiO3 nanoparticles: harvesting cold–hot alternation energy near room-temperature. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 2198–2207 (2018).

You, H. et al. Room-temperature pyro-catalytic hydrogen generation of 2D few-layer black phosphorene under cold-hot alternation. Nat. Commun. 9, 2889 (2018).

Sebald, G., Pruvost, S. & Guyomar, D. Energy harvesting based on Ericsson pyroelectric cycles in a relaxor ferroelectric ceramic. Smart Mater. Struct. 17, 015012 (2008).

Olsen, R. B. & Evans, D. Pyroelectric energy-conversion-hysteresis loss and temperature sensitivity of a ferroelectric material. J. Appl. Phys. 54, 5941–5944 (1983).

Kakekhani, A. & Ismail-Beigi, S. Ferroelectric oxide surface chemistry: water splitting via pyroelectricity. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 5235–5246 (2016).

Djani, H., Bousquet, E., Kellou, A. & Ghosez, P. First-principles study of the ferroelectric Aurivillius phase Bi2WO6. Phys. Rev. B 86, 054107 (2012).

Djani, H., Hermet, P. & Ghosez, P. First-principles characterization of the P21ab ferroelectric phase of Aurivillius Bi2WO6. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 13514–13524 (2014).

Liang, L. et al. Single unit cell bismuth tungstate layers realizing robust solar CO2 reduction to methanol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 54, 13971–13974 (2015).

Zhou, Y. et al. High-yield synthesis of ultrathin and uniform Bi2WO6 square nanoplates benefitting from photocatalytic reduction of CO2 into renewable hydrocarbon fuel under visible light. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 3, 3594–3601 (2011).

Cheng, H. et al. An anion exchange approach to Bi2WO6 hollow microspheres with efficient visible light photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to methanol. Chem. Commun. 48, 9729–9731 (2012).

McDowell, N. A., Knight, K. S. & Lightfoot, P. Unusual high-temperature structural behaviour in ferroelectric Bi2WO6. Chem. Eur. J. 12, 1493–1499 (2006).

Machado, R., Stachiotti, M. G., Migoni, R. L. & Tera, A. H. First-principles determination of ferroelectric instabilities in Aurivillius compounds. Phys. Rev. B 70, 214112 (2004).

Wang, R., Ni, S., Liu, G. & Xu, X. Hollow CaTiO3 cubes modified by La/Cr co-doping for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 225, 139–147 (2018).

Xu, G. et al. Integrating the g-C3N4 nanosheet with B-H bonding decorated metal-organic framework for CO2 activation and photoreduction. ACS Nano 12, 5333–5340 (2018).

Yang, R., Yu, X., Zhang, Y., Li, W. & Tsubaki, N. A new method of low-temperature methanol synthesis on Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts from CO/CO2/H2. Fuel 87, 443–450 (2008).

Liu, R.-h, Fu, S.-y, Zhan, H.-y & Lucia, L. A. General spectroscopic protocol to obtain the concentration of the superoxide anion radical. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 48, 9331–9334 (2009).

Akram, N. et al. Synergistic catalysis of Co(OH)2/CuO for the degradation of organic pollutant under visible light irradiation. Sci. Rep. 10, 1939 (2020).

Sekizawa, K., Maeda, K., Domen, K., Koike, K. & Ishitani, O. Artificial Z-scheme constructed with a supramolecular metal complex and semiconductor for the photocatalytic reduction of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 4596–4599 (2013).

SanchezPortal, D., Ordejon, P., Artacho, E. & Soler, J. M. Density-functional method for very large systems with LCAO basis sets. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 65, 453–461 (1997).

Troullier, N. & Martins, J. L. Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. Phys. Rev. B 43, 1993–2006 (1991).

Ceperley, D. M. & Alder, B. J. Ground sate of the electron gas by a stochastic method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 566–569 (1980).

Perdew, J. P. & Zunger, A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5048–5079 (1981).

Hu, J. & Pan, B. C. The optical and vibrational properties of dominant defects in undoped ZnO: A first-principles study. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 083710 (2009).

Peterson, A. A., Abild-Pedersen, F., Studt, F., Rossmeisl, J. & Norskov, J. K. How copper catalyzes the electroreduction of carbon dioxide into hydrocarbon fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1311–1315 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Thermal energy harvesting using pyroelectric-electrochemical coupling in ferroelectric. Mater. Joule 4, 301–309 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21971172, 21671141, 11574223, 51872264), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20150303), the Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions for Optical Engineering, Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Photovoltaic Science and Engineering, Shaanxi National Science Foundation of China (2020JM-579), Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province, China (2020GXLH-Z-032), and the Public Welfare Technology Application Research Project of Zhejiang Province, China (LGG18E020005). STEM work is supported by funding from the National Science Foundation of China (21805184), the National Science Foundation Shanghai (18ZR1425200), and the Center for High-resolution Electron Microscopy (CħEM) at ShanghaiTech University (EM02161943).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. and Y.J. conceived the project and idea. L.X. and X.X. carried out the experiment and process data. G.H. and J.H. perform the theoretical calculations. Y.Y. and B.Y. carried out the STEM. All authors participated in the formulation of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Chris R. Bowen, Yasuo Izumi, and other, anonymous, reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, L., Xu, X., Jia, Y. et al. Pyroelectric nanoplates for reduction of CO2 to methanol driven by temperature-variation. Nat Commun 12, 318 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20517-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20517-1

This article is cited by

-

2D MXenes polar catalysts for multi-renewable energy harvesting applications

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Pyro-catalysis for tooth whitening via oral temperature fluctuation

Nature Communications (2022)

-

In-plane sulfur vacancy of MoS2 enabling efficient CO2 hydrogenation to methanol at low temperature

Science China Chemistry (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.