Abstract

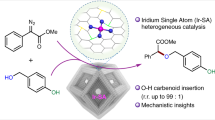

Selectivity in N–H and S–H carbene insertion reactions promoted by Ru(II)porphyrinates currently requires slow addition of the diazo precursor and large excess of the primary amine and thiol substrates in the reaction medium. Such conditions are necessary to avoid the undesirable carbene coupling and/or multiple carbene insertions. Here, the authors demonstrate that the synergy between the steric shielding provided by a Ru(II)porphyrinate-based macrocycle with a relatively small central cavity and the kinetic stabilization of otherwise labile coordinative bonds, warranted by formation of the mechanical bond, enables single carbene insertions to occur with quantitative efficiency and perfect selectivity even in the presence of a large excess of the diazo precursor and stoichiometric amounts of the primary amine and thiol substrates. As the Ru(II)porphyrinate-based macrocycle bears a confining nanospace and alters the product distribution of the carbene insertion reactions when compared to that of its acyclic version, the former therefore functions as a nanoreactor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rich coordination chemistry of porphyrinates1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 is useful in the design of macrocyclic receptors, in which the porphyrinate subunits are positioned on the top of molecular capsules to create hollow structures with well-defined cavities19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. In such molecular architectures, one of the axial positions of the metallic center is shielded from the environment, while the other has unencumbered reactivity. This asymmetry between the two axial coordination sites of the porphyrinate subunit can be explored to introduce a steric bias in the binding modes of the receptor18,19,20,21,22. For example, the porphyrinate’s external axial position can be blocked by selective coordination of bulky and inert monodentate ligands. With such configuration of the ligands around the metal center, the internal coordination site of the porphyrinate-based receptor can bind nonbulky substrates to efficiently and selectively promote their reactions inside the central cavity23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Such versatile strategy has been explored in the active-metal template synthesis of interlocked molecules24,25,26,27, asymmetric catalysis28,29 and biomimetics30,31,32. However, in those applications, the porphyrinate-based macrocycles has virtually the same reactivity as their acyclic analogues.

To expand the scope of porphyrinate-based molecular capsules, incorporation of nanoreactor concepts33 are highly desirable. Nanoreactors are designed to create nanoscale chemical environments partitioned from the bulk in order to change the reactivity of molecules upon binding inside the cavity, therefore altering their behavior in chemical transformations. Congruently, nanoreactors can dramatically change the outcome of chemical reactions 33.

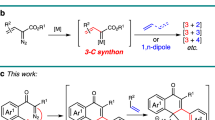

The carbene transfer/insertion reactions promoted by Ru(II)porphyrinates from diazo derivatives are versatile synthetic methods as they catalyze a wide range of chemical transformations such as cyclopropanation, 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions, X–H (X = C, N, O, and S) insertions and olefination of aldehydes in the presence of phosphines34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. However, the methodologies based on carbene transfer/insertion processes promoted by Ru(II)porphyrinates suffer from a serious drawback, which is the concurrent dimerization side-reaction of the carbene intermediates. To avoid the undesirable dimerization process, the methods described in the literature require slow addition of the diazo derivative into the reaction medium in order to keep the carbene concentration at low levels34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Such strategy has had limited success42, often requiring long addition times of the diazo derivative. Among the X–H bond carbene insertion reactions, the N–H one is problematic40,41,42 for two reasons. Firstly, competition between the primary amine and the diazo groups on the substrates for the Ru(II)porphyrinate axial coordination sites slows down or even shuts down the Ru(II)porphyrinate capability to generate carbene intermediates. Secondly, selectivity to the secondary amine product is hard to achieve and requires careful control of the diazo concentration and reaction temperature as well as to use a large excess of the amine substrate (10× relative to the diazo derivative)42 to avoid double carbenoid insertions that lead to the tertiary amine analog.

Herein, it is reported the molecular design and coordinative properties of a Ru(II)porphyrinate-based molecular capsule that works as a nanoreactor. The molecular capsule quantitatively yields an asymmetrical [2]rotaxanes through the challenging single N–H carbenoid insertion by the active metal template technique using an equimolar mixture of substrates. No signs of dimerization side processes nor double insertions are observed in the rotaxane assembly reaction, even under severe experimental conditions for carbene transfer/insertion reactions34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Most surprisingly, the excess of substrates added to the reaction medium is completely recovered as unreacted materials after workup. That efficiency in formation of mechanical bonds is hard to achieve in the present case as the Ru(II)porphyrinate subunit on the macrocycle is still active after the rotaxane assembly process. Therefore, it was expected that intercomponent side reactions would plague our methodology as the inherent effective molarity effects of the mechanical bond should have favored such side reactions32. Conversely, the acyclic Ru(II)porphyrinate analog yields a product mixture composed of the carbene dimer and the mono/double inserted threads, highlighting the distinct reaction outcomes afforded by the two Ru(II)porphyrinates under the same conditions. A detailed structural investigation of the Ru(II)porphyrinate macrocyclic complex and the resulting [2]rotaxanes reveals the basic steps in which the macrocyclic Ru(II)porphyrinate operates to achieve the striking single N–H bond carbene insertion selectivity. To demonstrate the synthetic generality of the present methodology, we also describe the quantitative active metal template synthesis of the parent thioether-containing rotaxane, which is assembled through the S–H carbene insertion reaction. The findings reported herein demonstrate how the steric features of porphyrinate molecular capsules in combination with formation of mechanical bonds can be explored to change the reaction outcomes of challenging chemical transformations; the fundamental principle of nanoreactors.

Results

Molecular design and synthesis of the macrocyclic porphyrin-based ligand

The molecular design of the macrocyclic receptor 7 (Fig. 1) contemplates the structural requirements for the successful exploration of carbene insertion reactions. The molecular backbone of macrocycle 7 is exclusively composed of aromatic C–H bonds, which are chemically inert to Ru(II)-carbenoids34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. The rigid aromatic backbone inevitably leads to formation of a well-defined and relatively small central cavity in 7. The crystal structure (CCDC ID 1883084) of 7 (Fig. 2) reveals a virtually flat porphyrin core which together with the aromatic backbone creates a central cavity with dimensions of 8.49 and 7.91 Å (centroid-to-centroid of the phenyl spacers and porphyrin centroid-to-midpoint of C26–C26i bond on the phenanthrene moiety, respectively, with symmetry code: i = 1/2-x, y, z; see Supplementary Fig. S1 for complete atom numbering). Such cavity dimensions in 7 are rather smaller than those observed for a similar but semi-rigid porphyrin-based macrocycle reported in our previous works24,25 (cavity dimensions 10.30 and 8.40 Å).

Reagents and conditions: (i) Pd(PPh3)4, Na2CO3(aq), MePh/EtOH, reflux, 16 h, N2 atmosphere, 80% yield; (ii) Pd(Cl)2dppf, B2pin2, 1,4-dioxane, reflux, 16 h, N2 atmosphere, 85% yield; (iii) Pd(PPh3)4, Na2CO3(aq), PPh3, MePh/MeOH, reflux, 48 h, N2 atmosphere, 95% yield; (iv) dipyrromethane, TFA, CH2Cl2/CHCl3 (3:1, v/v), high dilution (0.213 mM), rt, 20 h, followed by DDQ, CH2Cl2, reflux, 2 h, 20% yield. Macrocycle 7 is prepared in 13% total yield relative to 2.

Single crystals were grown from a dichloromethane/methanol/tetrahydrofuran saturated solution by slow evaporation. Carbon atoms are shown in gray, nitrogen in blue and oxygen in red. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity purposes. Ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability levels. Symmetry code: i = 1/2-x, y, z. See Supplementary Fig. S1 for complete atom numbering. CCDC ID 1883084.

The angle between the porphyrin and the molecular aromatic loop mean planes is 62.12°, which is smaller than the expected 90°. Although that indicates that the molecular loop and porphyrin mean planes are not orthogonal in the solid state, NMR investigation informs that the meso-aryl rings are rapidly oscillating through their perpendicular orientation to the porphyrin mean plane43, which in turn allow the phenanthrene moiety to rapidly swing back-and-forth below the porphyrin centroid in solution. Such fast swinging movement renders the two faces of macrocycle 7 magnetically equivalent. Accordingly, all resonances are sharp and distinct in the 1H NMR spectrum of 7 (Supplementary Fig. S2), thus confirming the proposed hollow structure in solution (see Supplementary material for further discussion).

Structural and coordinative properties of the macrocyclic Ru(II)porphyrinate complexes

With the structural requirements for a porphyrin-based macrocyclic ligand satisfied by 7, we turned our attention to prepare the corresponding Ru(II)porphyrinate using the classical metalation protocol with Ru3(CO)12 as the metal source followed by purification in the presence of methanol36. In principle, metalation of macrocycle 7 under those conditions should have afforded a mixture composed of Ru(II)porphyrinate 8 and its isomer 9 (Fig. 3) as the central cavity provides no steric shielding for the selective coordination of small axial ligands such as carbonyl and methanol molecules. However, only one porphyrin product is isolated from the crude mixture. The 1H NMR spectrum of the isolated product is not consistent with the proposed isomeric mixture and reveals the expected set of signals for a single Ru(II)porphyrinate-based macrocycle (Supplementary Fig. S3)35. Congruently, 13C NMR and FTIR-ATR analyses (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5, respectively) show one single resonance at δ = 180.1 ppm and one stretching band (\(ν_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{stretch}}}\) = 1926 cm−1) for the carbonyl axial ligand in the isolated product, thus confirming formation of one single complex. Such coordinative properties are not ubiquitous as performing the metalation reaction under the same conditions used for 7 but with our previously reported24,25 semi-rigid and larger macrocycle as ligand yields the two expected isomers as revealed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (for spectrum and chemical structures, see Supplementary Fig. S6). Therefore, the structural features of 7, which yield a hollow receptor with a relatively small central cavity, is most likely the reason for such selectivity in the metalation reaction.

To identify which isomer, 8 or 9, is isolated from the metalation reaction of macrocycle 7, we took advantage of the steric constraints imposed by the central cavity in 8 and 9, along with the high affinity of Ru(II) ions for phosphorus-based ligands and the ring current effects provided by the porphyrin subunit. We reasoned that bulky triphenylphosphine species (PPh3) would easily displace the loosely bound and labile methanol axial ligand but not the kinetically robust carbonyl one in the coordination sphere of the Ru(II) ions in both isomers44. However, the internal axial position in isomer 9 would not be available for the incoming bulky PPh3 ligand due to the steric shielding provided by the appended aromatic loop. Conversely, the external position in complex 8 would be unencumbered, thereby allowing the substitution of the PPh3 ligand for the methanol one. If such ligand substitution reaction takes place, the ring current effects provided by the porphyrin core would shield the protons of the phenyl groups in the PPh3 ligand in the 1H NMR spectrum of the product. Therefore, the shielding of the PPh3 protons is a probe for the identification of the isolated product as complex 8 or 9 by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Treatment of the unidentified Ru(II)porphyrinate with excess of PPh3 in dichloromethane at room temperature followed by precipitation of the crude with petroleum ether lead to the axial ligand substitution reaction to quantitatively yield complex 10 (Fig. 3). 1H NMR analysis (Supplementary Fig. S7) clearly reveals the strong shielding of the protons of the PPh3 axial ligand, hence giving unmistakable evidence for the exclusive formation of 10.

For our purposes, complex 8 is useless as the stable and inert axial carbonyl ligand is coordinated to the Ru(II) ion inside the macrocycle’s cavity. Therefore, we investigated several protocols to substitute the internal carbonyl axial ligand in 8 with other ligands. Thermolysis44, photolysis45, and chemical oxidative decarbonylation reactions46 all failed in our hands, suggesting that the cavity provide the carbonyl ligand with great stability. Gratefully, treating 8 with diphenyldiazomethane34 in dichloromethane at room temperature followed by purification by column chromatography on neutral alumina affords target complex 11 (Fig. 3).

The proposed molecular structure of complex 11 is confirmed by x-ray diffraction on single crystals grown from slow evaporation of a dichloromethane/acetonitrile saturated solution of 11 (Fig. 4, CCDC ID 1988009). The organic backbone of the complex is virtually identical to that of the free ligand macrocycle 7 (Fig. 2), including the cavity dimensions. The complex has a distorted octahedral symmetry with a residual water molecule bound to the internal axial position and with the Ru(II) ion displaced 0.1449(8) Å from the porphyrin mean plane toward the carbene ligand. The axial Ru–C bond distance in 11 is 1.852(4) Å and thus comparable to those reported for other similar carbene-Ru(II)porphyrinates (1.841–1.876 Å)38. However, the Ru–C bond distance in 11 is significantly shorter when compared to the single Ru–C bonds (1.978–2.088 Å)42,47 usually observed in ruthenium complexes with N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. The short Ru–C bond distance together with the displacement of the Ru(II) ion from the porphyrin mean plane towards the carbene ligand reveals the formation of a robust axial Ru–C coordinative interaction with partial double bond character in 1148. Accordingly, the carbene carbon atom receives non-negligible electronic density back from the Ru ion (π-back donation)48,49. 1H NMR analysis on 11 confirms that the solid-state structural features are preserved in solution. The well-defined and sharp signals observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of 11 (Fig. 5, top) inform that the axial carbenoid ligand is inert in solution, which is also a consequence of the strong Ru–C axial bond. Such electronic interactions provide 11 with great thermal and chemical stability47,48,49, which in conjunction with the inertness of the carbenoid ligand in solution, yield the structural features required for an excellent endotopic promoter.

Single crystals were grown from a dichloromethane/acetonitrile saturated solution by slow evaporation. Carbon atoms are shown in gray, nitrogen in blue, oxygen in red, ruthenium in turquoise and chlorine in green. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity purposes. Ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability levels. CCDC ID 1988009.

Experimental conditions: 250 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K. Thread 16 was prepared aside for comparison purposes, using half-threads 13 and 14 as substrates and the acyclic version of 11 as promoter. Unambiguous proton assignments, including the HL signal in rotaxane 15 that overlaps with that of residual chloroform in the deuterated solvent, are based on 2D-NMR spectroscopy. Residual solvent peaks and aliphatic impurities are in gray: chloroform (δ = 7.26 ppm), water (δ = 1.56 ppm), “grease” (δ = 1.26 ppm and δ = 0.88 ppm) and silicone “grease” (δ = 0.07 ppm)52.

Active-metal-template syntheses of asymmetrical [2]rotaxanes through carbene insertion reactions and the nanoreactor effect

To demonstrate the endotopic properties of complex 11, we developed an active-metal template synthesis50,51 of an asymmetrical [2]rotaxanes through the problematic N–H carbene insertions (Fig. 6a)40,41 under relatively severe experimental conditions. Accordingly, we decided to add in one portion a relatively large excess of half-threads 13 and 14 (10 equiv) relative to macrocycle 11 (1 equiv). After 3 hours at room temperature, no reaction was observed. That inactivity is due to the coordination of the amino group in 13 to the internal axial position of the Ru(II) ion in 11 to form hexacoordinated complex 12 (Fig. 3), whose structure is unambiguously confirmed by comparing the 1H NMR spectra of complex 12, macrocycle 11 and half-thread 13 (see Supplementary Fig. S8 for spectra and further discussion).

a Synthesis of asymmetrical [2]rotaxanes by the active-metal template technique based on the Ru(II)porphyrinate-promoted N-H carbene insertion reactions. Experimental conditions: benzene, 8 h, N2 atmosphere, quantitative yield relative to 11. b Conceivable reaction mechanism for the carbenoid N–H insertion process promoted by the Ru(II)porphyrinate subunit in 11 that quantitatively yield asymmetrical [2]rotaxane 15 through the active-metal template technique. The aromatic loop in 11 is not shown in the mechanism for clarity purposes. R = 3,5-di-tert-butylphenoxy stopper groups.

The RH2N–Ru coordinative bond in 12 is inert at room temperature and shuts down the α-estercarbenoid production by 11 from diazo half-thread 1434,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. However, the interaction becomes labile at higher temperatures as heating the reaction mixture at 60 °C results in smooth and total interlocking of macrocycle 11. Significantly, the excess of half-threads 13 and 14 added to the reaction medium is completely recovered as unreacted materials after purification of the crude. No signs of noninterlocked threads (from reactions occurring exo-to the macrocycle’s cavity) or rotaxane by-products (from intercomponent reactions)32 are observed in our experiments. Those findings are surprising and convincingly demonstrate that macrocycle 11 shows chemical selectivity towards promoting a single N–H insertion. Most importantly, the single insertions occur exclusively through the macrocycle’s cavity. Hence, macrocycle 11 is an exceptional endotopic catalyst.

For comparison purposes, we performed the N–H carbene insertion reaction using as promoter the 5,15-bis(phenyl)Ru(II)porphyrinate with the diphenylcarbene axial ligand, which functions as the acyclic version of macrocycle 11, and 13 and 14 as substrates. Under the exact same conditions as those of the rotaxane assembly process, the acyclic Ru(II)porphyrinate leads to total consumption of 14 to afford a small amount of the respective dimer thread along with a mixture composed of the expected thread 16 (26% isolated yield relative to 14; for structure of 16 see Fig. 5, bottom) and the tertiary amine counterpart (65% isolated yield relative to 14; for structure see Supplementary Fig. S27), which is formed from the second carbenoid insertion into the secondary amine group of thread 16. Those findings unequivocally demonstrate that 11 functions as a molecular nanoreactor33 as the selectivity towards single N–H carbenoid insertions is unachievable in bulk solution under the conditions investigated.

A complete spectroscopic characterization of the structure of rotaxane 15 by 2D-NMR (see Supplementary Figs. S81–S87) allows unambiguous assignment of all resonances, which along with MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. S9) provide unequivocal evidence for the proposed interlocked architecture for 15 shown in Fig. 6a. Furthermore, the unique structural features of the interlocked architecture of 15, revealed by the NMR investigation, provide valuable insights into the nature of the highly chemical selectivity observed in the rotaxane assembly process (vide infra).

In the 1H NMR spectrum of 15 (Fig. 5, middle), one observes the duplication of the resonances of the meso-nuclei (HA) and the pyrrolic protons (HB) when compared to that of macrocycle 11, which is consistent with an asymmetrical [2]rotaxane architecture. The axial coordination of diphenylcarbene ligand is warranted by the observation of the diagnostic shielding of the resonances of protons HM-O as well as by the characteristic strongly de-shielded carbene nuclei resonance at δ = 330.3 ppm in the 13C NMR spectrum of 15 (Supplementary Fig. S10)34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Two dimensional NOESY NMR analysis (Supplementary Fig. S11) reveals NOEs between protons HQ’, HS, HT, HU HV and NH on the thread component and HG, HH, HL and HB on the macrocycle, thus confirming the formation of the mechanical bond in 15.

Resonances associated with the thread component (Fig. 5, bottom) informs about the structural peculiarities of rotaxane 15. The secondary N–H moiety is drastically shielded (Δδ = 6.49 ppm) in rotaxane 15 when compared to noninterlocked thread 16, revealing the coordination of the nitrogen atom of the secondary amine group on the thread to the Ru(II) ion on the macrocycle. As a result of such intercomponent chemical interaction, all nuclei on the thread (HS-X), including those on the stoppers (HP-R), are also shielded, indicating that the ring virtually covers the whole thread component in rotaxane 15.

The intercomponent interaction is inert at room temperature and, remarkably, at 333 K (60 °C) as revealed by the variable temperature-NMR analysis of 15 (Supplementary Fig. S12), which is unusual for this type of coordinative bond40,41. The R1R2HN–Ru axial interaction in 15 is kinetically stabilized by the mechanical bond, which constantly keeps the secondary NH binding group on the thread close to the Ru(II) ion on the macrocycle.

To generalize our method, macrocycle 11 was also investigated as promoter for S–H carbene insertions (Supplementary Fig. S13). By mixing thiol half-thread 17 (10 equiv) with macrocycle 11 (1 equiv) followed by one portion addition of half-thread 14 (10 equiv) in benzene at room temperature yields rotaxane 19 (Supplementary Fig. S13) in quantitative yield after 4 hours with complete recovering of the excess of substrates 14 and 17 as starting materials after workup. No signs of by-products were observed in the assembly process of 19 as in the case of the parent rotaxane 15. Most importantly, quantitative formation of rotaxane 19 informs that the S–H carbene insertion occurs at room temperature rather than at 60°C as necessary for the N–H insertion reaction. A complete structural characterization of rotaxane 19 by 2D-NMR spectroscopy (see Supplementary Figs. S15–S22) allows unambiguous assignment of all resonances and informs that the structural features of rotaxane 19 are very similar to that observed for rotaxane 15 analog. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. S23) confirms the interlocked architecture for 19 by revealing the correct ion mass peak at 1624.446 (calculated for C106H98N4O4SRu) along with the characteristic fragmentation pattern expected for that type of rotaxanes24,25,52.

Discussion

The endotopic and chemical selectivity observed for 11 under the demanding conditions investigated for the N–H carbene insertions in the rotaxane synthesis along with its distinct reaction outcome when compared to that afforded by the acyclic Ru(II)porphyrinate can be explained by three main factors, which are summarized in the proposed reaction mechanism depicted in Fig. 6b. Firstly, the lack of non-interlocked threads in the crude mixture, being them formed from carbene dimerization and/or mono/double N–H insertions is warranted by the inert and stable diphenylcarbene axial ligand coordinated exo-to the macrocycle’s cavity in 11. Such stability towards potential nucleophilic attack by the amine moiety in 13 and inertness towards ligand dissociation of the diphenylcarbene axial ligand are due to the significant electronic π-back donation from the Ru(II) ion to the carbene carbon as revealed by the short Ru–C bond (1.852(4) Å) measured in the crystal structure of 11 (Fig. 4) and verified in solution by NMR spectroscopy. Accordingly, only the internal axial position of 11 is available for activation of the substrates.

Secondly, coordination of the amino group in 13 to the internal axial position of 11 yields complex 12 (step a, Fig. 6b) prior to the initiation of the organometallic cycle. Formation of complex 12, which is inert at room temperature, informs about the pre-association of 11 and 13. Heating the reaction solution at 60°C renders complex 12 labile (step b, Fig. 6b), which means that half-thread 13 enters and leaves the coordination sphere of the Ru(II) ions 11 rapidly. Therefore, half-thread 13 is held nearby the Ru(II) ion during the rotaxane assembly process. As soon as the α-estercarbenoid intermediate A is formed34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42 from the reaction between half-thread 14 and 11 after N2 extrusion (step c, Fig. 6b), the relatively stronger nucleophilic power of the amino group in 13 associated with its enforced local concentration near the cavity kinetically favor the N–H insertion (step d, Fig. 6b) instead of the deleterious carbene dimerization. Therefore, symmetrical rotaxanes from dimerizations are not observed in our experiments.

Finally, the kinetic stabilization of the axial R1R2HN–Ru coordinative interaction by the mechanical bond in 15, in conjunction with the somewhat short molecular linkage between the two stoppers, force the latter to be held in front of the faces of the macrocyclic component in the rotaxane architecture. The steric shielding of both macrocycle’s faces by the two stoppers associated with the small cavity provided by the rigid aromatic backbone completely block the access of exogenous substrates to the Ru(II) ions after rotaxane formation. Accordingly, the synergy between such steric and electronic effects shuts down the Ru(II) ion activity in 15 and explain the selectivity of the process towards the single N–H insertion, even in the presence of a large excess of half-thread 14 at 60 °C. Conversely, the experiment promoted by the acyclic Ru(II)porphyrinate demonstrates that after the first N–H carbene insertion that afford thread 16, the resulting axial R1R2HN–Ru interaction is labile due to the lack of the mechanical bond. Congruently, 16 dissociates from the acyclic Ru(II)porphyrinate to allow the turnover of the Ru(II) ions, which then further react with additional 14 molecules present in excess in the reaction medium to generate the α-estercarbenoid intermediate. The lack of the steric shielding in the acyclic Ru(II)porphyrinate permits the secondary amine group on 16 to attack the carbene intermediate to mostly afford the double inserted product.

The similar reaction outcome of the S–H insertion when compared to that of the N–H counterpart suggests that the former reaction should take place through the same mechanism proposed in Fig. 6b. In other words, coordination of the thiol group in 17 to the internal axial position of the Ru(II) ion in 11 should occur to form the hexacoordinated intermediate complex 18 (Supplementary Figure S13). However, the RHS–Ru interaction is labile at room temperature, and complex 18 does not require heating to generate carbenes from half-thread 14 as in the case of the parent complex 12 (Fig. 3).

In conclusion, a rigid porphyrin-based hollow receptor with a relatively small and well-defined central cavity revealed unusual coordinative properties as ligand for Ru(II) ions. Capitalizing on that, we developed a macrocyclic Ru(II)porphyrinate receptor bearing a stable and inert diphenylcarbene axial ligand, which functions as a nanoreactor and alters the outcome of N–H bond carbene insertions when compared to that of its acyclic analog. The findings reported herein establish the basis for the synergetic combination between the steric properties of porphyrinate molecular capsules and formation of mechanical bonds as principles for the design of nanoreactors in order to gain control over the product distribution of challenging chemical transformations. The synthetic utility of the present methodology relies on the conversion of the substrates into mechanical bonds with quantitative efficiency via either N–H or S–H carbene insertions even in the presence of substrate excess. As formation of the mechanical bond blocks the turnover of the Ru(II) ions through a combination of steric and electronic effects, each Ru(II)porphyrinate promotes one single carbene insertion, thus no intercomponent nor side-reactions are observed. The opportunity now exists to apply the technique described herein to assemble interlocked polymers with well-defined structures and low polydispersities. Increasingly, we can look forward to the preparation of copolyrotaxanes as we can now use the reaction temperature to selectively control the carbene insertions either in the S-H or N-H bonds. Such interlocked polymers and copolymers will allow a fundamental investigation of the effects of the inherent dynamic processes of mechanical bonds52 in the properties of macromolecules. Research along those lines is in progress.

Methods

Synthesis of macrocycle 11

In a 100 mL Schlenk flask, macrocycle 8 (0.010 g, 0.011 mmol, 1 equiv) was dissolved in 20 mL of dichloromethane under magnetic stirring at room temperature and inert atmosphere. A dichloromethane solution of freshly prepared diphenyldiazomethane (0.008 g, 0.040 mmol, in 4.00 mL of dichloromethane) was added dropwise to the solution of 8 over 3 h. At the end of the addition, the reaction mixture was magnetically stirred for another 1 h at room temperature. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by chromatography column on neutral alumina using a mixture of petroleum ether/dichloromethane (1:1, v/v) as eluent to afford macrocycle 11 as a red solid in 64% yield (7.4 mg). TLC (petroleum ether:CH2Cl2, 1:1 v/v): Rf = 0.56.; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.34 (s, 2H, HA); 8.66 (d, J = 4.74 Hz, 4H, HB); 8.47 (d, J = 4.70 Hz, 4H, HB); 8.03 (d, J = 7.36 Hz, 2H, HC); 7.90-7.85 (m, 4H, HE and HF); 7.79-7.73 (m, 2H, HD); 7.65 (d, J = 8.20 Hz, 2H, HJ); 7.49 (s, 2H, HK); 7.46 (d, J = 8.39 Hz, 2H, HI); 7.17 (s, 2H, HL); 6.91 (d, J = 8.17 Hz, 4H, HG); 6.65 (d, J = 8.17 Hz, 4H, HH); 6.44 (t, J = 7.30 Hz, 2H, HO); 6.10 (t, J = 7.56 Hz, 4H, HN); 2.88 (d, J = 7.56 Hz, 4H, HM). Impurities: 5.30 (dichloromethane); 1.26 and 0.88 (aliphatic impurities); 13C NMR (60 MHz, CDCl3): Macrocycle 11 was too insoluble to record 13C NMR. MALDI-TOF (m/z): [M]+ calcd. for C71H44N4Ru, 1054.260; found 1054.191. UV-Vis (CH2Cl2), 10-5 mol/L, λmax (nm): 274, 317, 391, 424, 527 and 550.

Synthesis of rotaxane 15

In a 10 mL Schlenk flask, macrocycle 11 (10 mg, 9.4 μmol, 1.0 equiv) and half-thread 13 (24.7 mg, 94.0 μmol, 10.0 equiv) were dissolved in 1.2 mL of benzene under inert atmosphere at room temperature. The resulting solution was stirred for 15 minutes at room temperature. Compound 14 (29.9 mg, 94.0 μmol, 10.0 equiv) was added in one portion as a solid to the reaction flask and the mixture was heated at 60°C for 8 hours. The crude mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The viscous crude product was dissolved in a minimum amount of petroleum ether. The excess of half-thread 14 was insoluble in the petroleum ether phase and was removed using a pipette as a colorless oil. The petroleum-ether solution was further purified by preparative TLC on silica using petroleum ether/dichloromethane (1:1, v/v) as eluent to afford the target rotaxane 15 as a red solid in quantitative yield relative to 11 (15.0 mg) as the first fraction. The excess of half-thread 13 was isolated as the second fraction as a colorless oil. TLC (petroleum ether:CH2Cl2, 1:1 v/v): Rf = 0.79. 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.09 (s, 1H, HA); 9.00 (s, 1H, HA); 8.64 (d, J = 4.83 Hz, 2H, HB); 8.52 (d, J = 4.59 Hz, 2H, HB); 8.47 (d, J = 4.83 Hz, 4H, HB); 8.26 (d, J = 4.83 Hz, 4H, HB); 8.16 (d, J = 7.49 Hz, HC); 7.88-7.65 (m, 6H, HD, HE and HF); 7.58 (d, J = 8.29 Hz, 2H, HJ); 7.44 (s, 2H, HK); 7.32 (d, J = 8.29, 2H, HI); 7.26 (s, 2H, HL); 7.09 (d, J = 8.29, 4H, HG); 6.98 (t, J = 1.48 Hz, 1H, HP’); 6.66-6.58 (m, 5H, HP and HH); 6.47 (d, J = 1.43, 2H, HQ’); 6.43 (t, J = 7.36, 2H, HO); 6.10 (t, J = 7.73, 4H, HN); 5.61 (d, J = 1.52 Hz, HQ); 3.48 (br, 2H, HX); 3.37 (br, 2H, HW); 2.91 (d, J = 7.10, 4H, HM); 1.87 (t, J = 5.35 Hz, 2H, HS); 1.25 (s, 18H, HR’); 0.94 (s, 18H, HR); from −1.76 to −2.45 (br, 4H, HV and HU); −2.86 (br, 2H, HT); −4.25 (br, 1H, NH). Impurities: 1.56 (residual water in the CDCl3 solvent); 0.07 (silicon “grease”). 13C NMR (60 MHz, CDCl3): δ 330.3; 168.2; 162.7; 158.0; 157.9; 152.2; 151.3; 144.6; 144.1; 143.9; 143.4; 143.1; 141.3; 140.3; 140.0; 139.7; 134.9; 133.1; 132.8; 131.8; 131.6; 130.8; 129.9; 129.6; 129.5; 128.1; 127.9; 126.2; 125.8; 125.2; 123.4; 123.1; 118.4; 115.2; 113.9; 111.6; 108.8; 108.0; 107.4; 107.0; 64.7; 64.3; 62.4; 53.5; 46.1; 44.2; 35.0; 34.6; 31.5; 31.3; 29.8; 22.8; 22.1; 14.2. Impurities: 53.5 (residual dichloromethane); 29.8; 22.8 and 14.2 (aliphatic impurities). MALDI-TOF (m/z): [M]+ calcd. for C106H99N5O4Ru, 1607.6741; found 1607.603. UV-Vis, λmax (nm): 270, 313, 398, 425 and 530. FTIR (ATR), ν (cm−1): 1741.

Synthesis of rotaxane 19

In a 10 mL Schlenk flask, under inert atmosphere, macrocycle 11 (10 mg, 0.0094 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and half-thread 17 (26.0 mg, 0.094 mmol, 10.0 equiv) were dissolved in 1.2 mL of benzene at room temperature. The resulting solution was stirred for 15 minutes at rt. Compound 14 (29.9 mg, 0,094 mmol, 10.0 equiv) was added as a solid to the reaction flask and the mixture was magnetically stirred at room temperature for 4 hours. TLC analyses on silica revealed that macrocycle 11 was completely interlocked after that period. The crude mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure, dissolved in a minimum amount of petroleum ether and purified by preparative TLC on silica using petroleum ether/dichloromethane (50:50, v/v) as eluent to afford the target rotaxane 19 as a red solid in quantitative yield (91% isolated yield; 0.014 mg) as the second fraction. The excess of half-threads 17 and 14 was completely recovered as the first (colorless oil) and third (yellowish oil) fractions, respectively. TLC (petroleum ether:CH2Cl2, 1:1 v/v): Rf = 0.79. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 9.16 (s, 1H, HA); 9.08 (s, 1H, HA); 8.63 (d, J = 4.55 Hz, 2H, HB); 8.53 (d, J = 4.73 Hz, 2H, HB); 8.48 (d, J = 4.55 Hz, 4H, HB); 8.36 (d, J = 4.77 Hz, 4H, HB); 8.23 (d, J = 6.57 Hz, HC); 7.84 (td, J = 7.62 Hz e 1.01 Hz, 2H HD); 7.75 (td, J = 7.53 Hz e 1.28 Hz, 2H, HE); 7.70 (d, J = 7.67, 2H, HF); 7.58 (d, J = 8.26 Hz, 2H, HJ); 7.44 (s, 2H, HK); 7.37 (s, 2H, HL); 7.33 (d, J = 8.35, 2H, HI); 7.03 (d, J = 8.26, 4H, HG); 6.94 (br, 1H, HP’); 6.71 (br, 1H, HP); 6.65 (d, J = 8.37 Hz, 4H, HH); 6.49 (t, J = 7.44, 2H, HO); 6.39 (s, 2H, HQ’); 6.15 (t, J = 7.79, 4H, HN); 5.85 (s, 2H, HQ); 3.18 (br, 2H, HX); 2.99 (d, J = 7.25, 4H, HM); 2.73 (br, 2H, HW); 2.38 (br, J = 5.35 Hz, 2H, HS); 1.23 (s, 18H, HR’); 1.00 (s, 18H, HR); −1.76 (br, 2H, HV); −1.90 (br, 2H, HU); −2.05 (s, 2H, HT). Impurities: 1.58 (residual water); 1.26 e 0.07 (aliphatic impurities).13C NMR (60 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.3; 161.4; 158.0; 157.7; 152.2; 151.7; 144.9; 144.5; 143.8; 143.2; 143.1; 141.0; 140.2; 139.7; 139.4; 135.0; 133.0; 132.7; 131.9; 131.7; 130.8; 130.1; 129.8; 129.7; 128.3; 128.2; 128.0; 126.2; 125.7; 125.4; 125.2; 123.9; 123.6; 119.0; 115.2; 114.2; 112.6; 108.6; 108.1; 107.4; 107.0; 65.4; 64.4; 62.5; 35.0; 34.7; 31.5; 31.3; 29.8; 28.6; 28.0; 23.7. Impurities: 29.8; 22.8 e 14.2 (aliphatic impurities). MALDI-TOF (m/z): [M]+ calcd. for C106H98N4O4Ru, 1624.635; found 1624.446.

NMR experiments

1H, 13C, 31P, COSY, HMBC and HSQC NMR spectra were obtained on either a Bruker AVANCE 250 (250 MHz) or a Bruker AVANCE 500 (500 MHz), in all cases using deuterated solvents as the lock. The spectra were collected at 298 K or 333 K, and chemical shifts reported in parts per million (δ, ppm) were referenced to residual solvent peak. Residual solvent peaks and eventual aliphatic impurities were assigned according to literature53. Two dimensional NOESY NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker AVANCE 400 (400 MHz) using CDCl3 as deuterated solvent at 298 K and 400 ms mixing time.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurements

X-Ray quality crystals of macrocycles 7 and 11 were grown from slow evaporation of a dichloromethane/methanol/tetrahydrofuran and dichloromethane/acetonitrile saturated solutions, respectively. Both compounds crystalized as red needle-like single crystals with approximate dimensions of 0.025 mm × 0.01 mm × 0.05 mm for macrocycle 7 and 0.27 × 0.08 × 0.08 mm for macrocycle 11. The X-ray diffraction experiments were performed at the MX2 beamline at the UVX synchrotron source at the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Source. For further information about the X-ray experiments, see Supplementary Material.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files) or available from the authors upon reasonable request. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1883084 and 1988009. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Rickhaus, M. et al. Global aromaticity at the nanoscale. Nat. Chem. 12, 236 (2020).

Megiatto, J. D. Jr. & Schuster, D. I. Introduction of useful peripheral functional groups on [2]catenanes by combining Cu (I) template synthesis with “click” chemistry. N. J. Chem. 34, 276 (2010).

Zhao, J. et al. Proton mediated spin state transition of cobalt heme analogs. Nat. Commun. 10, 2303 (2019).

Megiatto, J. D. Jr., Spencer, R. & Schuster, D. I. Optimizing reaction conditions for synthesis of electron donor-[60]fullerene interlocked multiring systems. J. Mat. Chem. 21, 1544 (2011).

Longevial, J.-F. et al. Peripherally metalated porphyrins with applications in catalysis, molecular electronics and biomedicine. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 15442 (2018).

Megiatto, J. D. Jr., Schuster, D. I., de Miguel, G., Wolfrum, S. & Guldi, D. M. Topological and conformational effects on electron transfer dynamics in porphyrin-[60]Fullerene interlocked systems. Chem. Mat. 24, 2472 (2012).

Polizzi, N. F. et al. De novo design of a hyperstable non-natural protein-ligand complex with sub-Å accuracy. Nat. Chem. 9, 1157 (2017).

Antoniuk-Pablant, A. et al. A new method for the synthesis of β-cyano substituted porphyrins and their use as sensitizers in photoelectrochemical devices. Mat. Chem. A 4, 2976 (2016).

Zhang, W. et al. Porous metal-metalloporphyrin gel as catalytic binding pocket for highly efficient synergistic catalysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 1913 (2019).

Auwaerter, W., Ecija, D., Klappenberger, F. & Barth, J. V. Porphyrins at interfaces. Nat. Chem. 7, 105 (2015).

Megiatto, J. D. Jr., Schuster, D. I., Abwandner, S., de Miguel, G. & Guldi, D. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 3847 (2010).

Ousaka, N. et al. Water-mediated deracemization of a bisporphyrin helicate assisted by diastereoselective encapsulation of chiral guests. Nat. Commun. 10, 1457 (2019).

Kirner, S. V., Henkel, C., Guldi, D. M., Megiatto, J. D. Jr. & Schuster, D. I. Chem. Sci. 6, 7293 (2015).

Wang, S. et al. Controllable hierarchical self-assembly of porphyrin-derived supra-amphiphiles. Nat. Commun. 10, 1399 (2019).

Kirner, S. V., Guldi, D. M., Megiatto, J. D. Jr. & Schuster, D. I. Synthesis and photophysical properties of new catenated electron donor–acceptor materials with magnesium and free base porphyrins as donors and C60 as the acceptor. Nanoscale 7, 1145 (2015).

Megiatto, J. D. Jr. et al. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding as a synthetic tool to induce chemical selectivity in acid catalyzed porphyrin synthesis. Chem. Comm. 48, 4558 (2012).

Megiatto, J. D. Jr. et al. A bioinspired redox relay that mimics radical interactions of the Tyr–His pairs of photosystem II. Nat. Chem. 6, 423 (2014).

Koepf, M., Wytko, J. A., Bucher, J.-P. & Weiss, J. Surface-tuned assembly of porphyrin coordination oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 9994 (2008).

Gunter, M. J. & Mullen, K. M. Dynamic axial ligand-site exchange in facially discriminated ruthenium(II) carbonyl and rhodium(III) halide metalloporphyrins. Inorg. Chem. 46, 4876 (2007).

Koepf, M. et al. Design of porphyrin-based ligands for the assembly of [d-block metal: calcium] bimetallic centers. Dalton Trans. 46, 4199–4208 (2017).

Urbani, M. & Torres, T. Tautomerism and atropisomerism in free‐base (meso)‐strapped porphyrins: static and dynamic aspects. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 16337 (2014).

Tang, H. & Dolphin, D. Interaction of derivatized capped iron(II) porphyrin complexes with CO and O2. Inorg. Chem. 35, 6539 (1996).

Collman, J.-P., Lee, V. J., Zhang, X., Ibers, J. A. & Brauman, J. I. Enantioselective epoxidation of unfunctionalized olefins catalyzed by threitol-strapped manganese porphyrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 3834 (1993).

Alcântara, A. F. P. et al. Olefin cyclopropanation by radical carbene transfer reactions promoted by cobalt (II)/porphyrinates: active‐metal‐template synthesis of [2]rotaxanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 8979 (2018).

Alcântara, A. F. P. et al. Control over the redox cooperative mechanism of radical carbene transfer reactions for the efficient active‐metal‐template synthesis of [2]rotaxanes. Chem. Eur. J. 26, 7808 (2020).

Wolf, M. et al. Light triggers molecular shuttling in rotaxanes: control over proximity and charge recombination. Chem. Sci. 10, 3846 (2019).

Miyazaki, Y. et al. CuAAC in a distal pocket: metal active‐template synthesis of strapped‐porphyrin [2] rotaxanes. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 13579 (2017).

Lang, H. Y. et al. Next-generation D2-symmetric chiral porphyrins for cobalt(II)-based metalloradical catalysis: catalyst engineering by distal bridging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2670 (2019).

Lang, K., Torker, S., Wojtas, L. & Zhang, X. P. Asymmetric induction and enantiodivergence in catalytic radical C-H amination via enantiodifferentiative H-atom abstraction and stereoretentive radical substitution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 12388 (2019).

Thordarson, P., Bijsterveld, E. J. A., Rowan, A. E. & Nolte, R. J. M. Epoxidation of polybutadiene by a topologically linked catalyst. Nature 424, 915 (2003).

van Dongen, S. F. M. et al. A clamp-like biohybrid catalyst for DNA oxidation. Nat. Chem. 5, 945 (2013).

van den Boomen, O. I. et al. Carbenoid transfer reactions catalyzed by a ruthenium porphyrin macrocycle. Tetrahedron 73, 5029 (2017).

Petrosko, S. H., Johnson, R., White, H. & Mirkin, C. A. Nanoreactors: small spaces, big implications in chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 7443 (2016).

Zhou, C.-Y., Huang, J.-S. & Che, C.-M. Ruthenium-porphyrin-catalyzed carbenoid transfer reactions. Synlett 18, 2681 (2010).

Che, C.-M. et al. Asymmetric inter- and intramolecular cyclopropanation of alkenes catalyzed by chiral ruthenium porphyrins. synthesis and crystal structure of a chiral metalloporphyrin carbene complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 4119 (2001).

Ho, C.-M. et al. A water-soluble ruthenium glycosylated porphyrin catalyst for carbenoid transfer reactions in aqueous media with applications in bioconjugation reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1886 (2010).

Reddy, A. R., Zhou, C.-Y., Guo, Z., Wei, J. & Che, C.-M. Ruthenium–porphyrin‐catalyzed diastereoselective intramolecular alkyl carbene insertion into C-H bonds of alkyl diazomethanes generated in situ from N‐tosylhydrazones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 14175 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Spectral, structural, and electrochemical properties of ruthenium porphyrin diaryl and aryl(alkoxycarbonyl) carbene complexes: influence of carbene substituents, porphyrin substituents, and trans-axial ligands. Chem. Eur. J. 10, 3486 (2004).

Yu, X.-Q., Huang, J. S., Yu, W.-Y. & Che, C.-M. Polymer-supported ruthenium porphyrins: versatile and robust epoxidation catalysts with unusual selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 5337 (2000).

Galardon, E., Le Maux, P. & Simonneaux, G. Cyclopropanation of alkenes, N–H and S–H insertion of ethyl diazoacetate catalysed by ruthenium porphyrin complexes. Tetrahedron 56, 615 (2000).

Galardon, E., Roué, S., Le Maux, P. & Simonneaux, G. Asymmetric cyclopropanation of alkenes and diazocarbonyl insertion into S-H bonds catalyzed by a chiral porphyrin Ru (II) complex. Tetrahedron Lett. 39, 2333 (1998).

Chan, K.-H., Guan, X., Lo, V. K.-Y. & Che, C.-M. Elevated catalytic activity of ruthenium (II)–porphyrin‐catalyzed carbene/nitrene transfer and insertion reactions with N‐heterocyclic carbene ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 2982 (2014).

Dirks, J. W., Underwood, G., Matheson, J. C. & Gust, D. Conformational dynamics of alpha.,. beta.,. gamma.,. delta-tetraarylporphyrins and their dications. J. Org. Chem. 44, 2551 (1979).

Stulz, E. et al. Phosphine and phosphonite complexes of a ruthenium (II) porphyrin. 1. Synthesis, structure, and solution state studies. Inorg. Chem. 41, 5255 (2002).

Sovocool, G. W., Hopf, F. R. & Whitten, D. G. Metalloporphyrin photochemistry. Ruthenium(II) porphyrin photodimer with a metal-metal bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94, 4350 (1972).

Spiccia, L., Deacon, G. B. & Kepert, C. M. Synthetic routes to homoleptic and heteroleptic ruthenium(II) complexes incorporating bidentate imine ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 248, 1329 (2004).

Samojłowicz, C., Bieniek, M. & Grela, K. Ruthenium-based olefin metathesis catalysts bearing N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. Chem. Rev. 109, 3708 (2009).

Frémont, P., Marion, N. & Nolan, S. P. Carbenes: synthesis, properties, and organometallic chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 253, 862 (2009).

Lee, M.-T. & Hu, C.-H. Density functional study of N-heterocyclic and diamino carbene complexes: comparison with phosphines. Organometallics 23, 976 (2004).

Beves, J. E., Blight, B. A., Campbell, C. J., Leigh, D. A. & McBurney, R. T. Strategies and tactics for the metal-directed synthesis of rotaxanes, knots, catenanes, and higher order links. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 9260 (2011).

Denis, M. & Goldup, S. M. The active metal template approach to interlocked molecules. Nat. Rev. 1, 1 (2017).

Megiatto, J. D. Jr., Schuster, D. I. & Guldi, D. M. Design, synthesis and photoinduced processes in molecular interlocked photosynthetic [60]fullerene systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 8 (2020).

Gottlieb, H. E., Kotlyar, V. & Nudelman, A. NMR chemical shifts of common laboratory solvents as trace impurities. J. Org. Chem. 62, 7512 (1997).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) for financial support (Grants 2013/22160‐0 and 2015/23761‐2) and fellowship for LAF (2017/06752‐5). JDMJ thanks Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the research fellowship (#307635/2018-0). We also thank Prof. Anita J. Marsaioli for the MALDI‐TOF mass spectrometer and the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory (LNLS), an open national facility operated by the Brazilian Centre for Research in Energy and Materials (CNPEM) for the Brazilian Ministry for Science, Technology, Innovations and Communications (MCTIC). MAR thanks the suport from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Espírito Santo (FAPES) Grant #174/2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D.M.J. conceived, designed the experiments, directed the research, analyzed/interpreted the data and compose the manuscript. L.A.F. performed the experiments, analyzed/interpreted the data and contributed to the manuscript preparation. M.P.A., A.F.P.A. and V.H.R. provided some help with the syntheses. L.A.F., M.A.R. and W.P.B. are responsible for the crystal structures. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fontana, L.A., Almeida, M.P., Alcântara, A.F.P. et al. Ru(II)Porphyrinate-based molecular nanoreactor for carbene insertion reactions and quantitative formation of rotaxanes by active-metal-template syntheses. Nat Commun 11, 6370 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20046-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20046-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.