Abstract

The rise of two-dimensional (2D) crystalline superconductors has opened a new frontier of investigating unconventional quantum phenomena in low dimensions. However, despite the enormous advances achieved towards understanding the underlying physics, practical device applications like sensors and detectors using 2D superconductors are still lacking. Here, we demonstrate nonreciprocal antenna devices based on atomically thin NbSe2. Reversible nonreciprocal charge transport is unveiled in 2D NbSe2 through multi-reversal antisymmetric second harmonic magnetoresistance isotherms. Based on this nonreciprocity, our NbSe2 antenna devices exhibit a reversible nonreciprocal sensitivity to externally alternating current (AC) electromagnetic waves, which is attributed to the vortex flow in asymmetric pinning potentials driven by the AC driving force. More importantly, a successful control of the nonreciprocal sensitivity of the antenna devices has been achieved by applying electromagnetic waves with different frequencies and amplitudes. The device’s response increases with increasing electromagnetic wave amplitude and exhibits prominent broadband sensing from 5 to 900 MHz.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Crystal symmetry plays an essential role in condensed matter physics. Breaking inversion symmetry in materials profoundly changes the electronic ground states of materials and thus brings about many novel physical properties and functionalities, such as nonlinear Hall effect in Weyl semimetals1,2, chiral optical responses in semiconductors3,4 and ferroelectricity5. One particular example is the nonreciprocal charge transport in systems with both broken inversion and time-reversal symmetries6, where the electrical resistivity of a conductor is expected to vary depending on the current and magnetic field direction. Experimentally, nonreciprocal charge transport has been demonstrated in Bi helix7, chiral magnet8,9, Rashba semiconductor10, LaAlO3/SrTiO3 oxide interface11 and in various superconducting systems. These include superconducting non-centrosymmetric gated-MoS212, Bi2Te3/FeTe heterostructures13 and MoGe/Y3Fe5O12 bilayers14, where the nonreciprocal response is markedly enhanced by several orders of magnitude compared to non-superconducting systems due to the large energy scale difference between the Fermi energy and the superconducting gap12,15. Apart from being a powerful tool to study the interplay between superconductivity and chirality in non-centrosymmetric superconductors6,16, nonreciprocal charge transport also promises great potential in superconducting device applications such as vortex diodes17 and flux lenses18, both of which are in great demand for future electrical circuits.

Atomically thin NbSe2 is an emerging non-centrosymmetric superconductor possessing unique intrinsic Ising-type spin-orbit coupling, in which the electron spin is locked to the out-of-plane direction19,20. Accordingly, many exotic superconducting characteristics arise, for example, extremely large upper critical fields exceeding the Pauli limit19,21,22 and an unusual continuous paramagnetic-limited superconductor-normal metal transition20. Meanwhile, as the thickness is reduced to the atomic scale where the fluctuation and disorder begin to play roles, 2D NbSe2 becomes very sensitive to environmental perturbations23. Based on the aforementioned good merits, 2D NbSe2 provides an ideal platform for exploring new mechanisms of nonreciprocal charge transport in non-centrosymmetric superconductors15,24 and further device applications25. In particular, compared with conventional diodes that utilize a built-in electric field in semiconductor junctions, rectifiers based on atomically thin superconductors using the intrinsic electronic properties of quantum crystals pave the way towards the realization of high-frequency sensors and detectors for next-generation wireless networks26. However, practical sensing devices based on layered superconductors are still lacking.

Here we report the observation of nonreciprocal charge transport in atomically thin 2D NbSe2 and the demonstration of successful manipulation of nonreciprocal sensitivity in atomically thin NbSe2 antenna devices. The second harmonic magnetoresistance of few-layer NbSe2 exhibits multiple antisymmetric reversals when the temperature is below the superconducting transition temperature TC, manifesting itself as a feature of reversible nonreciprocal charge transport due to the broken inversion symmetry. Utilizing the reversible nonreciprocal charge transport in NbSe2, we have built superconducting antenna devices that exhibit a strong reversible nonreciprocal sensitivity to the applied alternating current (AC) electromagnetic waves. Furthermore, we find that the response of the antenna increases monotonically with the increasing amplitude of the electromagnetic waves and that the devices show prominent broadband sensing from 5 to 900 MHz. Our research not only demonstrates the exotic physics in 2D NbSe2 but also establishes it to be a promising platform for radio-frequency energy-harvesting, sensing, and identification applications.

Results

Nonreciprocal charge transport in 2D NbSe2

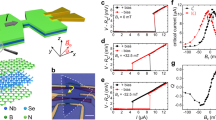

Figure 1a shows the typical crystal structure of NbSe2. It has a hexagonal lattice structure within the a-b plane and crystalizes with the P63/mmc space group27. Monolayer NbSe2 consists of a sublayer of Nb atoms sandwiched between two sublayers of Se atoms in the trigonal prismatic structure19,28. Spatial inversion symmetry is broken in monolayer NbSe2 because the Nb and Se sites are not equivalent. Various thicknesses of atomically thin NbSe2 were obtained via exfoliation of bulk crystals onto SiO2/Si substrates (see Methods for details). Figure 1b displays an optical image of an exfoliated few-layer NbSe2 flake where the number of layers is marked. Figure 1c shows an atomic-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image taken from an atomically thin exfoliated NbSe2 flake. In perfect regions of the crystal, the atomic arrangement agrees well with the expected 2H crystal structure of NbSe229. However, Fig. 1c shows that some point defects (highlighted by circles) can be observed locally, even in high-quality exfoliated materials. This kind of point defects can act as asymmetric pinning potentials in superconducting regimes30,31,32 which we will discuss later. Figure 1d displays the selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern, confirming that the exfoliated flake is a single crystal and its dominant surface is {0001}.

a. Top and side views of NbSe2 crystal. Nb atoms (shown dark green) are sandwiched between two layers of Se (shown light green) atoms. Monolayer NbSe2 exhibits spatial inversion symmetry breaking because the Nb and Se sites are not equivalent. b. Optical image of a few-layer flake of NbSe2 cleaved on a SiO2/Si substrate with a spin-coated PMMA/MMA polymer on it. The number of layers is labeled. Scale bar: 5 μm. c. High-resolution TEM image taken from a NbSe2 flake suspended on a TEM grid, in which the Nb and Se atomic columns are marked by green and yellow dots. And the selected point defects located at Nb and Se sites are highlighted by green and yellow circles, respectively. Scale bar: 1 nm. d. SAED taken from the NbSe2 flake along [0001] zone axis. Scale bar: 2 nm−1.

As is typical for systems with broken inversion symmetry, nonreciprocal charge transport, so-called magneto-chiral anisotropy, will appear when time-reversal symmetry is broken by an external magnetic field24,33. Under such circumstances, the electrical resistance of the device will depend on the current direction and can be phenomenologically described as7,12,24,34

Here, R0 represents the resistance at zero magnetic field, I is the electrical current, B is the external magnetic field and γ is a coefficient representing the strength of the magneto-chiral anisotropy effect(see Supplementary Note 1 for detail). Based on Eq. (1), we have carried out nonreciprocal charge transport experiments using a typical device structure shown in Fig. 2a with the optical image in Fig. 2b inset. The first and second harmonic magnetoresistances were measured simultaneously. The temperature-dependent normalized resistance R/R300 K of a five-layer device is shown in Fig. 2b. The sample exhibits a metallic behavior upon cooling and becomes superconducting at TC = 6.5 K (TC is defined as the temperature corresponding to 50% of the resistance above the superconducting transition RN). Figure 2c illustrates the temperature-dependent first harmonic resistance Rω with a perpendicular magnetic field from −7 to 7 T, in which each Rω(B)-T curve overlaps with Rω(-B)-T curve. Interestingly, for the temperature-dependent R2ω as depicted in Fig. 2d, the R2ω(B)-T and R2ω(-B)-T curves are symmetric with respect to the x-axis. These phenomena are also consistent with the behaviors of first harmonic and second harmonic magnetoresistance isotherms shown in Fig. 2e, f, where Rω-B and R2ω-B curves are respectively symmetric and antisymmetric with respect to the y-axis. The antisymmetric feature of R2ω-B curve is consistent with Eq. (1) which unambiguously suggests the existence of the magneto-chiral anisotropy in 2D NbSe212,15,24.

a, Sketch of the four-terminal device based on atomically thin NbSe2. The magnetic field is perpendicularly to the substrate plane. b, The temperature dependence of the normalized resistance of the NbSe2 device. Inset, an optical image of the four-terminal NbSe2 device with a thickness of five layers. Scale bar, 5 μm. c, d, Temperature-dependent Rω and R2ω of the device under positive and negative magnetic fields applied perpendicularly to the substrate, where Rω(B)-T and Rω(-B)-T curves overlap each other while R2ω(B)-T and R2ω(-B)-T curves are symmetric with respect to the x-axis (I0 = 25 μA and f = 17.1 Hz). e, Magnetoresistance isotherm of the device with the temperature changing from 2 to 7 K, which are symmetric with respect to the y-axis. f, R2ω-B curves of the device at temperatures of 2 to 7 K, showing antisymmetric behavior at T < 7 K, which is consistent with the first harmonic signal in (e). g, The extracted maximum value of R2ω-B curves \(\left| {R_{MAX}^{2\omega }} \right|\) as a function of temperature. The pink squares \(\left| {R_{MAX1}^{2\omega }} \right|\) stands for the peak values in the larger magnetic field regime, the purple triangles \(\left| {R_{MAX2}^{2\omega }} \right|\) stands for the peak values in the small magnetic field regime at B ≥ 5.25 K. h, Calculated temperature-dependent γ and │γ′│, where \(\gamma = \frac{{\sqrt 2 \left| {R_{MAX1}^{2\omega }} \right|}}{{BR^\omega I_0}}\) and \(\gamma ^{\prime} = \frac{{\sqrt 2 \left| {R_{MAX2}^{2\omega }} \right|}}{{BR^\omega I_0}}\), respectively. γ and γ′ have an opposite sign due to the opposite nonreciprocity. i, Temperature-magnetic field phase diagram of the NbSe2 device. The dark pink dots stand for crossover between the vortex solid (glass) state and vortex liquid state at which R2ω goes to zero. The dark blue dots show the crossing point of the vortex liquid state and normal state. R2ω goes to zero when further increasing the magnetic field. The yellow dots are the crossing point where R2ω changes sign, defining the boundary between the activated pinned vortex states (light blue area) and vortex liquid state at TM ≥ 5.25 K. Here TM is the melting temperature above which the vortex solid melts.

Furthermore, the R2ω-B curve shows one pair of peaks at low temperatures in the first and third quadrant (T ≤ 5 K) and as the temperature increases further (T > 5 K), another pair of peaks emerge in the second and fourth quadrant (also see Supplementary Fig. 2). The extracted peak values of the R2ω-B curve \(\left| {R_{MAX1}^{2\omega }} \right|\) and \(\left| {R_{MAX2}^{2\omega }} \right|\) are shown in Fig. 2g, demonstrating that both \(\left| {R_{MAX1}^{2\omega }} \right|\) and \(\left| {R_{MAX2}^{2\omega }} \right|\) are greatly enhanced at T < TC and \(\left| {R_{MAX1}^{2\omega }} \right|\) saturates at T ≤ 4.5 K. The deduced γ and γ´ values as a function of temperature are shown in Fig. 2h, here γ and γ´ are defined as \(\gamma = \frac{{\sqrt 2 \left| {R_{MAX1}^{2\omega }} \right|}}{{BR^\omega I_0}}\) and \(\gamma ^{\prime} = \frac{{\sqrt 2 \left| {R_{MAX2}^{2\omega }} \right|}}{{BR^\omega I_0}}\), respectively (the corresponding values of B and Rω were used to calculate γ and γ′). The maximum of γ and γ′ are 6.53 × 102 T−1A−1 and 3.43 × 104 T−1A−1, respectively. Both of them are higher than those reported in other non-superconducting systems such as Bi helix (γ ∼ 10−3 A−1 T−1)34, chiral organic materials (γ ∼ 10−2 A−1 T−1)33, BiTeBr (γ ∼ 1 A−1 T−1)10 and LaAlO3/SrTiO3 oxide interface11 (γ ∼ 102 A−1 T−1). The normalized coefficient value which defined as \(\gamma _N = \gamma A\) and \(\gamma ^{\prime}_N = \gamma ^{\prime}A\) (A here is the cross-sectional area of device) are 1.44 × 10−11 T−1A−1m2 and 7.55 × 10−10 T−1A−1m2, respectively. Both are also higher than that observed in LaAlO3/SrTiO3 oxide interface11 (∼1.17 × 10−11 T−1A−1m2). The large enhancement of the nonreciprocity below the superconducting transition temperature is due to the reduction of the energy denominator from the Fermi energy (∼100 meV) to the superconducting gap (∼1 meV)12,13,15. Note that R2ω appears only in the resistive state (because the vortex flow in 2D NbSe2 causes dissipation, see Supplementary Note 2 for details). In other words, R2ω is nonzero only when NbSe2 is in the vortex flow regime, signaling the close relationship between R2ω and the vortex motion. Recent theory has revealed that nonreciprocal charge transport occurs in non-centrosymmetric superconductors when vortices driven by the external charge current move among the asymmetric pinning potentials in the vortex flow regime15. In 2D NbSe2, the asymmetric pinning potentials naturally appear as a consequence of disorder15 such as defects30,31,32 in 2D crystals with inversion symmetry breaking, as shown in Fig. 1c. Accordingly, we attribute the emergence of another pair of R2ω peaks at T > 5 K to the melting of the vortex solid (glass) state into the activated pinned vortex states at relatively high temperatures as shown in Fig. 2i. In the low-temperature regime (T ≤ 5 K), as the magnetic field increases, NbSe2 transforms from the non-resistive vortex solid state into the resistive vortex liquid state, in which R2ω reaches its maximum value. Further increasing the magnetic field will quench the NbSe2 into the normal state, giving rise to a non-detectable R2ω. While in the high temperate regime (T ≥ TM = 5.25 K), the vortex solid state will melt into the resistive activated pinned vortex states35 where R2ω also appears. Then the system undergoes a transition from activated pinned vortex states to vortex liquid states as the magnetic field increases. Note that the vortex in activated pinned vortex states will be thermally activated and will jump36 between asymmetric pinning barriers, which is different from that in vortex liquid states where the vortex moves more freely. We then infer that the nonreciprocity of the vortex motion in activated pinned vortex states and vortex liquid states are opposite, leading to the two pairs of antisymmetric peaks in the high-temperature regime (also see Supplementary Note 2).

Next, we try to measure the second harmonic magnetoresistance of NbSe2 at various applied AC currents with different amplitudes I0 (I0 is the effective value of the AC current, see Methods). Figure 3a depicts the first harmonic magnetoresistance Rω of the device measured at T = 2 K with I0 changing from 5 to 100 μA. In the small current regime (I0 ≤ 15 μA), the Rω-B curves almost overlap with each other, indicating a negligible effect of the applied current on the superconducting states of NbSe2. While in the larger current regime (I0 ≥ 20 μA), the nonzero region (0 < Rω < RN) of the Rω-B curves expands as the current further increases. In other words, the larger the current is, the easier the magnetic field will bring the system into resistive states. Correspondingly, the second harmonic magnetoresistance firstly increases then decreases as I0 increases as shown in Fig. 3b. We extract the maximum value of \(R_{MAX}^{2\omega }\) versus I0 in Fig. 3c. In the small current regime (I0 ≤ 15 μA), the maximum value of \(R_{MAX}^{2\omega }\) increases linearly with the increase of I0, consistent with Eq. (1). As I0 further increases (I0 ≥ 20 μA), the rectification effect of vortex motion will be decreased by the relative weakening of the pinning potentials30,37,38. Also, the quenching of superconductivity in NbSe2 can no longer be neglected. As a result, \(R_{MAX}^{2\omega }\) decreases as I0 increases at I0 ≥ 20 μA.

a, Current-dependent first harmonic signal of the five-layer NbSe2 device at T = 2 K. In the small current regime (I0 ≤ 15 μA), the Rω-B curves are nearly unchanged with the increase of I0, suggesting a negligible change of the superconducting properties due to the increasing current. While in the larger current regime (I0 ≥ 20 μA), prominent expansion of the nonzero region in the Rω-B curves emerges, indicating a non-negligible breaking of superconducting states by increasing I0. b, Corresponding current-dependent second harmonic signal of NbSe2 at T = 2 K. c, Deduced maximum value \(\left| {R_{MAX}^{2\omega }} \right|\) as a function of applied current, showing a linear increase at small current bias (I0 ≤ 15 μA) and a decreasing behavior as I0 increases further (I0 ≥ 20 μA).

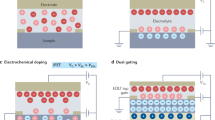

Reversible nonreciprocal DC sensitivity in atomically thin NbSe2 antenna

Having understood the nonreciprocal charge transport in 2D NbSe2, we next explore its direct current (DC) sensitivity and the relationship with nonreciprocal charge transport. We first built a NbSe2 antenna device in order to investigate whether or not it can respond to externally applied electromagnetic waves. The device structure is illustrated schematically in Fig. 4a with the corresponding optical image in Fig. 4b. Here an AC electromagnetic wave is applied to the resistor fabricated on the same substrate. The resistance of the resistor is intentionally designed to be ∼50 Ω so as to give an impedance matching the AC signal. Figure 4c shows the R2ω(B)-T curve of a three-layer NbSe2 device. The R2ω(B)-T and R2ω(-B)-T curves are symmetric with respect to the x-axis, consistent with the previous five-layer device in Fig. 2d. Figure 4d is the DC response of the device with the AC signal applied across the resistor under various magnetic fields (VP-P = 200 mV, fIN = 5.52 MHz, see Supplementary Figs. 6, 7 for additional data). The device gives a prominent DC response as the temperature drops below TC. Surprisingly, the VDC(B)-T and VDC(-B)-T curves are symmetric with respect to the x-axis, same as the R2ω(B)-T curve, suggesting a close relationship between the second harmonic signal and the DC response. As shown in Fig. 4e, f, the similarity of R2ω and VDC can also be observed in second harmonic magnetoresistance and VDC isotherms with the temperature varying from 2 to 6.75 K. Note that the device also gives an antisymmetric DC response to the environmental fluctuation when there is no AC signal applied to the resistor (Fig. 4f inset and Supplementary Fig. 7b, the environmental fluctuations are mainly a few MHz electromagnetic waves in a cryostat14,23).

a, Schematic structure of the NbSe2 antenna device for the measurement of DC signal. The nanovoltage meter was directly connected to NbSe2. Sine wave AC signals were applied to the fabricated resistor. b, Optical image of the antenna device, scale bar, 20 μm. The NbSe2 thickness is three layers. c, R2ω-T of the device under negative and positive applied magnetic fields perpendicular to the substrate (with no AC signal applied on the resistor). d, VDC-B of the device with sine wave AC signal (VP-P = 200 mV, fIN = 5.52 MHz) applied on the resistor. e, R2ω-B curves of the device with the temperature changing from 2 to 6.75 K. Inset, the first harmonic signal of the device measured simultaneously with the second harmonic signal. Both the first and second harmonic signals were measured under no AC signal applied to the resistor. f, DC signal VDC-B of the device with the temperature changing from 2 to 6.75 K with sine wave AC signal (VP-P = 200 mV, fIN = 5.52 MHz) applied to the resistor, showing similar antisymmetric behavior to the R2ω-B curves. Inset, DC signal of the device at T = 2 K with no AC signal applied to the resistor. The antisymmetric signal comes from environmental fluctuations.

The similarity of R2ω and VDC can be explained using Eq. (1) which describes the nonreciprocal charge transport in 2D NbSe2 due to the vortex in asymmetric pinning potentials. If we apply an AC excitation current of \(I = \sqrt 2 I_0\sin \omega t\) to the device, then the voltage of the device can be expressed as13,15,39

where the first term is the first harmonic term, the second term is the second harmonic term and the third term is the DC term (see Supplementary Note 1 for a detailed derivation of the equation). Equation (2) above suggests that if we apply an AC current to the device with inversion symmetry breaking, a DC current will be generated. Then the device can be viewed as a p-n junction or rectifier where their asymmetry can convert an AC current passing through the device into a DC current14. The difference is that the device here has both an AC and DC current. In Eq. (2), the second term and the third DC term carry the same \(\gamma B\) term, indicating that the second harmonic signal and the DC response should have the same relationship with the applied magnetic field. This explains the phenomena that we see in our experiments; that the VDC curves of the device have a similar shape as the R2ω curves. Furthermore, from the point of view of vortex motion, the asymmetric pinning potential in superconducting NbSe2 exerts a counterforce with different magnitudes to each direction of the AC driving force40,41 (introduced by the electromagnetic waves radiated onto NbSe2). As a result, the vortices acquire a net velocity, generating the DC voltage17,42 (see Supplementary Note 2). Also, because the trilayer NbSe2 here exhibits a much lower melting temperature than the five-layer device above, there is no vortex solid state for the device when T ≥ 2 K (see Supplementary Fig. 3). Consequently, the NbSe2 changes from the activated pinned vortex state to the vortex liquid state as the magnetic field increases, leading to two pairs of antisymmetric peaks in both R2ω-B and VDC-B curves at T ≥ 2 K (see Supplementary Note 2). It should also be noted that compared to conventional ratchets composed of artificial structures which rectify AC-driven vortices into a DC electric field without sensing ability17,42,43, our device utilizes the intrinsic inversion symmetry breaking in few-layer NbSe2 and provides extreme sensitivity in the superconducting regime, thus realizing nonreciprocal sensing in 2D NbSe2.

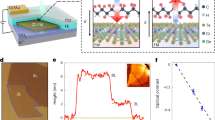

Manipulating nonreciprocal sensitivity in NbSe2 antenna

To control the performance of the NbSe2 antenna device, we then try to change the frequency and the amplitude of the applied AC signal. Figure 5a displays the color plot of VDC as a function of the frequency fIN and magnetic field of the NbSe2 antenna device at VP-P = 1 V and T = 2 K. The device shows prominent broadband sensing from 5 to 900 MHz(see Supplementary Figures 8, 9 for additional data) and the maximum response of the device appears at fIN ∼ 200 MHz. Also, the color plot is symmetric with respect to y-axis and the sign of VDC changes 3 times as the magnetic field increases from −3.5 to 3.5 T, indicating the nonreciprocal sensitivity of NbSe2 antenna device. Figure 5b shows the Color plot of VDC as a function of frequency fIN and VP-P of the device at B = 0.12 T and T = 2 K. The entire spectrum agrees with Fig.5a and the device’s response increases with the increase of the VP-P, suggesting that the device provides an increased DC response as the applied power of the resistor increases (see Supplementary Fig. 8). This is also confirmed in Fig. 5c, which shows the DC response of the device under various AC amplitudes at fIN = 200 MHz. Accordingly, as the amplitude increases from 0 to 1 V (considering the resistor value of ∼50 Ω, the applied power PIN increases from 0 to 2.5 mW as VP-P changes from 0 to 1 V, see Supplementary Fig. 8), the maximum value VMAX1 increases from 3.5 to 5.9 μV and VMAX2 increases from 0.5 to 22 μV (Fig. 5d, e). Here VMAX1 and VMAX2 are defined as \(V_{MAX1} = \left( {\left| {V_{P1}} \right| + \left| {V_{P2}} \right|} \right)/2\) and \(V_{MAX2} = \left( {\left| {V_{P3}} \right| + \left| {V_{P4}} \right|} \right)/2\), where VP1-VP4 are the peak values of VDC as shown in Fig. 5a. The larger variation of VMAX2 than VMAX1 in response to increased applied power is due to the larger γ´ value than γ (see Supplementary Note 2). All these results suggest that we have successfully pushed the relative low-frequency rectification in nonreciprocal charge transport into the radio-frequency sensitivity of the antenna device. It should be noted that the maximum response frequency of each NbSe2 device varies. This may due to the different levels of disorder and defects in each device (see Supplementary Figs. 11–15 for additional antenna devices with different thicknesses). Additionally, the device does not show a cutoff behavior at the maximum frequency that our equipment can reach (900 MHz). Note this value is much larger than the resonant frequency of the vortex moving in the artificial periodic potential (∼100 MHz)18. This may due to the much smaller size (atomic level) of the asymmetric pinning potential in 2D NbSe2(see Supplementary Note 4). Thus, the NbSe2 sensing antenna has great potential to realize sensitive detection at much higher frequencies in the future.

a, Color plot of VDC as a function of the frequency fIN and magnetic field of the NbSe2 antenna device at VP-P = 1 V and T = 2 K. The NbSe2 thickness is five layers. b, Color plot of VDC as a function of frequency fIN and VP-P of the device at B = 0.12 T and T = 2 K. c, VDC-B of the device with VP-P value (that is, the power of the AC signal applied on the resistor) changing from 0 to 1 V at T = 2 K, fIN = 200 MHz. VP1-VP4 are the peak values of VDC. d, e, Extracted VMAX1 and VMAX2 value as a function of VP-P value, where \(V_{MAX1} = \left( {\left| {V_{P1}} \right| + \left| {V_{P2}} \right|} \right)/2\), \(V_{MAX2} = \left( {\left| {V_{P3}} \right| + \left| {V_{P4}} \right|} \right)/2\). Both VMAX1 and VMAX2 values increase monotonically as the increase of VP-P value. f, The dynamic behavior of the device with the AC signal (fIN = 200 MHz, VP-P = 1 V) switching on and off at B = 0.08 T and −0.08 T, respectively. g, Retention behavior of the device under various magnetic fields with a frequency of fIN = 200 MHz, and VP-P = 1 V at T = 2 K. h, Time evolution of the generated power of a 100 Ω resistor connected to the device (B = 0.1 T, fIN = 200 MHz, VP-P = 1 V, T = 2 K), showing a stable detection after 4300 s. Inset, a schematic circuit diagram of the measurement of the generated power on a 100 Ω resistor connected to the device.

To probe the stability of the device, we first measure the dynamic behavior of the NbSe2 antenna device. In Fig. 5f, the DC response of the device was monitored with the AC signal (fIN = 200 MHz, VP-P = 1 V) being switching on and off. The device exhibits a stable and repeatable response to the AC signal with different magnetic fields and the on/off voltage ratio reaches ∼17. We then turn to measure the retention characteristic of the NbSe2 antenna. As shown in Fig. 5g, we keep the magnetic field at the peak position value (P1-P4 inset Fig. 5g) and measure the DC response of the device with the AC wave (FIN = 200 MHz, VP-P = 1 V) applied on the resistor. The DC response of the device was monitored for 4300 s, during which the generated DC voltage is very stable in all four states. This nonreciprocal multi-states of the antenna device suggest its potential applications in radio-frequency information storage and identification44. As shown in Fig. 5h, we have also connected a 100 Ω load resistor to the device (Fig. 5h inset) and measured the power on it (PL) for 4300 s. The generated power PL by the NbSe2 antenna is very stable during the measurement. Note PL here is a net value because we have subtracted the power generated from the environmental fluctuation. All these experiments suggest good device stability and versatile application capability of the NbSe2 sensing device in electronic circuits.

Discussion

During the experiment, we have also performed second harmonic and DC response measurement on samples with various thicknesses (see Supplementary Figs. 11–15 for details). Due to the weak interlayer coupling, few-layer NbSe2 behaves like its monolayer rather than bulk material in which inversion symmetry is preserved. As a result, we can observe the nonreciprocal charge transport and DC sensitivity in few-layer NbSe2 which is not present in the bulk material. We believe that the nonreciprocity still dominates the vortex motion due to the weaker interlayer coupling constant compared to the spin splitting energy in few-layer NbSe2 (see Supplementary Note 7 for a detailed discussion). However, the underlying exquisite physics needs further theoretical and experimental investigation. This study has suggested that low-dimensional crystalline superconductors are promising systems to realize the control of vortex motion and further device applications. Our work highlights NbSe2 as a model system for exploring nonreciprocal charge transport and controlling nonreciprocal sensitivity in its antenna devices, paving the way to understanding the exotic physics in layered low-dimensional crystalline superconductors and allowing their integration into new functionality devices.

Methods

Sample growth. High-quality 2H-NbSe2 single crystals were synthesized using the Chemical Vapor Transport (CVT) method. The stoichiometric-ratio of Nb and Se powders with 0.2% excess of Se and 0.1 g iodine were evacuated and sealed in the quartz tube. The sealed tube was then placed in a double zone furnace horizontally and grown for 2 weeks in a temperature gradient of 730 to 770 °C. After that, the single crystals of 2H-NbSe2 were formed at the low-temperature end.

Device fabrication. Different thicknesses of NbSe2 were obtained through mechanical exfoliation of bulk single crystals onto pre-patterned SiO2(285 nm)/Si substrates using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps in the glove box. Multi-terminal electrical contacts were fabricated by standard EBL process using Polymethylmethacrylate/Methyl methacrylate bilayer polymer and subsequent deposition of Ti/Au (5 nm/80 nm) by magnetron sputtering. For the antenna device with the resistor, the resistance of the resistor was intentionally set to be ∼50 Ω by controlling the thickness of the gold and the length and width of the resistor. We limited the time that the devices were exposed to the air to less than 3 min to minimize the environmental effects on NbSe2.

Transport measurements. Four-terminal temperature-dependent magnetotransport and two-terminal DC measurements were carried out in a Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) system (Quantum Design). Both the first- and second-harmonic signals of the AC resistance were measured by means of lock-in amplifiers (SR830) by applying an AC current \(I = \sqrt 2 I_0\mathrm{sin}t ωt\). The measured first and second harmonic resistance is defined as Rω = Vω/I0, R2ω = V2ω/I0, here I0 is the effective value of the applied AC current, Vω and V2ω are the measured first harmonic and second harmonic voltage drop. During the AC resistance measurements, the applied current frequency is between 10–100 Hz. The phase between the first and second harmonic signal was set to be π/2. The DC response of the NbSe2 sensing device was collected using Keithley 2182 A and the high-frequency sine wave AC signal was applied to the resistor using Zurich Instruments UHFLI and Keithley 3390.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kang, K., Li, T., Sohn, E., Shan, J. & Mak, K. F. Nonlinear anomalous Hall effect in few-layer WTe2. Nat. Mater. 18, 324–328 (2019).

Ma, Q. et al. Observation of the nonlinear Hall effect under time-reversal-symmetric conditions. Nature 565, 337–342 (2019).

de Juan, F., Grushin, A. G., Morimoto, T. & Moore, J. E. Quantized circular photogalvanic effect in Weyl semimetals. Nat. Commun. 8, 15995 (2017).

Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Photonics and optoelectronics of 2D semiconductor transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Photonics 10, 216–226 (2016).

Shi, P.-P. et al. Symmetry breaking in molecular ferroelectrics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 3811–3827 (2016).

Tokura, Y. & Nagaosa, N. Nonreciprocal responses from non-centrosymmetric quantum materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 3740 (2018).

Rikken, G. L. J. A., Fölling, J. & Wyder, P. Electrical magnetochiral anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 236602 (2001).

Yokouchi, T. et al. Electrical magnetochiral effect induced by chiral spin fluctuations. Nat. Commun. 8, 866 (2017).

Aoki, R., Kousaka, Y. & Togawa, Y. Anomalous nonreciprocal electrical transport on chiral magnetic order. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 057206 (2019).

Ideue, T. et al. Bulk rectification effect in a polar semiconductor. Nat. Phys. 13, 578–583 (2017).

Choe, D. et al. Gate-tunable giant nonreciprocal charge transport in noncentrosymmetric oxide interfaces. Nat. Commun. 10, 4510 (2019).

Wakatsuki, R. et al. Nonreciprocal charge transport in noncentrosymmetric superconductors. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602390 (2017).

Yasuda, K. et al. Nonreciprocal charge transport at topological insulator/superconductor interface. Nat. Commun. 10, 2734 (2019).

Lustikova, J. et al. Vortex rectenna powered by environmental fluctuations. Nat. Commun. 9, 4922 (2018).

Hoshino, S., Wakatsuki, R., Hamamoto, K. & Nagaosa, N. Nonreciprocal charge transport in two-dimensional noncentrosymmetric superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 98, e1602390 (2018).

Itahashi, Y. M. et al. Nonreciprocal transport in gate-induced polar superconductor SrTiO3. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay9120 (2020).

Villegas, J. E. A superconducting reversible rectifier that controls the motion of magnetic flux quanta. Science 302, 1188–1191 (2003).

Moshchalkov, V., Woerdenweber, R. & Lang, W. Nanoscience and Engineering in Superconductivity. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2010).

Xi, X. et al. Ising pairing in superconducting NbSe2 atomic layers. Nat. Phys. 12, 139–143 (2016).

Sohn, E. et al. An unusual continuous paramagnetic-limited superconducting phase transition in 2D NbSe2. Nat. Mater. 17, 504–508 (2018).

Xing, Y. et al. Ising superconductivity and quantum phase transition in macro-size monolayer NbSe2. Nano Lett. 17, 6802–6807 (2017).

de la Barrera, S. C. et al. Tuning Ising superconductivity with layer and spin–orbit coupling in two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 9, 1427 (2018).

Tamir, I. et al. Sensitivity of the superconducting state in thin films. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau3826 (2019).

Wakatsuki, R. & Nagaosa, N. Nonreciprocal current in noncentrosymmetric rashba superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 026601 (2018).

Saito, Y., Nojima, T. & Iwasa, Y. Highly crystalline 2D superconductors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16094 (2017).

Isobe, H., Xu, S.-Y. & Fu, L. High-frequency rectification via chiral Bloch electrons. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay2497 (2020).

Marezio, M., Dernier, P. D., Menth, A. & Hull, G. W. The crystal structure of NbSe2 at 15°K. J. Solid State Chem. 4, 425–429 (1972).

Bawden, L. et al. Spin–valley locking in the normal state of a transition-metal dichalcogenide superconductor. Nat. Commun. 7, 11711 (2016).

Zou, Y.-C. et al. Superconductivity and magnetotransport of single-crystalline NbSe2 nanoplates grown by chemical vapour deposition. Nanoscale 9, 16591–16595 (2017).

Itahashi, Y. M., Saito, Y., Ideue, T., Nojima, T. & Iwasa, Y. Quantum and classical ratchet motions of vortices in a two-dimensional trigonal superconductor. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023127 (2020).

Zhao, K. et al. Disorder-induced multifractal superconductivity in monolayer niobium dichalcogenides. Nat. Phys. 15, 904–910 (2019).

Nguyen, L. et al. Atomic defects and doping of monolayer NbSe2. ACS Nano 11, 2894–2904 (2017).

Pop, F., Auban-Senzier, P., Canadell, E., Rikken, G. L. J. A. & Avarvari, N. Electrical magnetochiral anisotropy in a bulk chiral molecular conductor. Nat. Commun. 5, 3757 (2014).

Rikken, G. L. J. A. & Wyder, P. Magnetoelectric anisotropy in diffusive transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 016601 (2005).

Benyamini, A. et al. Fragility of the dissipationless state in clean two-dimensional superconductors. Nat. Phys. 15, 947–953 (2019).

Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity. (Courier Corporation, 2004).

Yokouchi, T. et al. Current-induced dynamics of skyrmion strings. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat1115 (2018).

Zhu, B. Y., Marchesoni, F., Moshchalkov, V. V. & Nori, F. Controllable step motors and rectifiers of magnetic flux quanta using periodic arrays of asymmetric pinning defects. Phys. Rev. B 68, 014514 (2003).

Qin, F. et al. Superconductivity in a chiral nanotube. Nat. Commun. 8, 14465 (2017).

Plourde, B. L. T. Nanostructured superconductors with asymmetric pinning potentials: vortex ratchets. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 19, 3698–3714 (2009).

Lee, C.-S., Jankó, B., Derényi, I. & Barabási, A.-L. Reducing vortex density in superconductors using the ‘ratchet effect’. Nature 400, 337–340 (1999).

Silva, C. C., de, S., Vondel, J. V., de, Morelle, M. & Moshchalkov, V. V. Controlled multiple reversals of a ratchet effect. Nature 440, 651–654 (2006).

Villegas, J. E., Gonzalez, E. M., Gonzalez, M. P., Anguita, J. V. & Vicent, J. L. Experimental ratchet effect in superconducting films with periodic arrays of asymmetric potentials. Phys. Rev. B 71, 024519 (2005).

Cui, L., Zhang, Z., Gao, N., Meng, Z. & Li, Z. Radio frequency identification and sensing techniques and their applications—a review of the state-of-the-art. Sensors 19, 4012 (2019).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11934005, 61322407, 11874116, 61674040), National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos. 2017YFA0303302 and 2018YFA0305601), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai (Grant No. 19511120500) and the Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader (Grant No. 20XD1400200). E.Z. acknowledges support from China Postdoctoral Innovative Talents Support Program (Grant No. BX20190085) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2019M661331). Part of the sample fabrication was performed at Fudan Nano-fabrication Laboratory. S.J.H. would like to acknowledge prior contributions to TEM sample preparation and imaging from Lan Nguyen and Ekaterina Khestanova (University of Manchester) and Reza Kashtiban (Warwick University), and funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (EvoluTEM grant No. [715502]). N.N. was supported by JST CREST Grant Number JPMJCR1874, Japan, and JSPS KAKENHI Grant numbers 18H03676.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.X. conceived the idea and supervised the experiments. E.Z., X.X., Y.Z., Z.J., X.D., C.H., P.L., S.L., X.P., M.Z., and Y.Y. carried out the device fabrication. L.A., E.Z., Z.J., and Y.Z. synthesized the NbSe2 bulk crystals. Y.-C.Z. and S.J.H. performed structural characterization and analysis. E.Z., H.G., and J.S. performed low-temperature measurements. E.Z. and N.N. analyzed the data. E.Z. and F.X. wrote the paper with help from all other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Jung-Woo Yoo and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, E., Xu, X., Zou, YC. et al. Nonreciprocal superconducting NbSe2 antenna. Nat Commun 11, 5634 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19459-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19459-5

This article is cited by

-

High-temperature Josephson diode

Nature Materials (2024)

-

Light-induced giant enhancement of nonreciprocal transport at KTaO3-based interfaces

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Superconducting diode effect sign change in epitaxial Al-InAs Josephson junctions

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Gate-tunable superconducting diode effect in a three-terminal Josephson device

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Local control of superconductivity in a NbSe2/CrSBr van der Waals heterostructure

Nature Communications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.