Abstract

A small in-plane external uniaxial pressure has been widely used as an effective method to acquire single domain iron pnictide BaFe2As2, which exhibits twin-domains without uniaxial strain below the tetragonal-to-orthorhombic structural (nematic) transition temperature Ts. Although it is generally assumed that such a pressure will not affect the intrinsic electronic/magnetic properties of the system, it is known to enhance the antiferromagnetic (AF) ordering temperature TN ( < Ts) and create in-plane resistivity anisotropy above Ts. Here we use neutron polarization analysis to show that such a strain on BaFe2As2 also induces a static or quasi-static out-of-plane (c-axis) AF order and its associated critical spin fluctuations near TN/Ts. Therefore, uniaxial pressure necessary to detwin single crystals of BaFe2As2 actually rotates the easy axis of the collinear AF order near TN/Ts, and such effects due to spin-orbit coupling must be taken into account to unveil the intrinsic electronic/magnetic properties of the system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

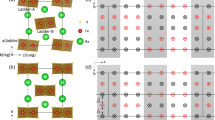

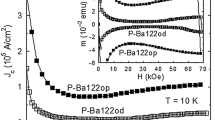

Understanding the intrinsic electronic, magnetic, and nematic properties of iron pnictides such as BaFe2As2 form the basis to unveil the microscopic origin of high-temperature superconductivity because the system is a parent compound of iron-based superconductors1,2,3,4,5. As a function of decreasing temperature, BaFe2As2 first exhibits a tetragonal-to-orthorhombic structural transition at Ts and forms a nematic ordered phase, followed closely by a collinear antiferromagnetic (AF) order with moment along the a-axis of the orthorhombic lattice below the Néel temperature TN (≤Ts) (Fig. 1a)6,7,8,9. Since single crystals of BaFe2As2 form twin domains in the orthorhombic state below Ts, an external uniaxial pressure applied along one of the in-plane Fe-Fe bond direction has been widely used as an effective method to acquire single domains of iron pnictide crystals and determine their intrinsic transport10,11,12,13,14,15, electronic16,17,18, and magnetic19,20,21 properties (inset in Fig. 1b). Although uniaxial pressure necessary to detwin single crystals of BaFe2As2 is known to increase TN (Fig. 1b)22,23,24,25 and create in-plane resistivity anisotropy above Ts14, it is generally assumed that it only induces a small strain on the sample and does not significantly modify the electronic and magnetic properties of the system10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,21. Recently, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments have revealed that an in-plane uniaxial strain on BaFe2As2 induces an enhancement of the low-energy spin fluctuations along the c-axis in the paramagnetic state above TN26. However, it is unclear whether the applied uniaxial pressure can actually modify the collinear AF structure of the system (Fig. 1a)6,7.

a Crystal and AF structure of BaFe2As2. The red arrows indicate the a-axis direction of magnetic moments. b Magnetic order parameters measured at Q1 = (1, 0, 3) and Q = (0, 1, 3) under uniaxial pressure, revealing TN = 143 K. The blue dashed curve denotes the magnetic order parameter measured on a strain-free sample with TN = 136 K. c Scattering geometry of polarized neutron scattering experiment in the [H, 0, L] plane. d The reciprocal space, where the fluctuating moments along the a-, b-, and c-axis directions are marked as Ma, Mb, and Mc, respectively. e Spin arrangements of BaFe2As2 in the paramagnetic (left), near TN (middle), and low-temperature AF state. f Temperature dependence of the static ordered magnetic moment Ma and Mc as determined from \({\sigma }_{x,z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) at (1, 0, 1) and (1, 0, 3). The vertical error bars are estimated errors from fits-to-order parameters. g Comparison of temperature dependence of the strain-induced lattice distortion from ref. 27 and our estimated Mc at ~20 (blue solid line) and ~45 (pink solid line) MPa.

In this work, we use polarized neutron scattering and unpolarized neutron diffraction to demonstrate that an in-plane uniaxial pressure necessary to detwin BaFe2As2 also induces a c-axis ordered magnetic moment and changes the easy axis of the collinear AF structure around the magnetic/nematic critical scattering temperature regime where the applied pressure has a large impact on the crystal structure of the system (Fig. 1c–g)27. In addition, we find that the applied pressure induces c-axis polarized critical spin fluctuations that diverge near TN/Ts, confirming the results of NMR experiments26. Therefore, uniaxial pressure on BaFe2As2 that breaks the tetragonal lattice symmetry also induces changes in the magnetic easy axis near the critical regime of the AF/nematic phase transitions, indicating that the intrinsic electronic and magnetic properties of the system near TN/Ts are much different from naive expectations.

Results

Collinear magnetic order in twinned BaFe2As2

Without external uniaxial pressure, BaFe2As2 exhibits separate weakly first-order magnetic and second-order structural phase transitions (Ts > TN by ~0.75 K)7. The spins within each FeAs layer are collinear and arranged antiferromagnetically along the a-axis and ferromagnetically along the b-axis of orthorhombic structure with lattice parameters of a and b, respectively (a > b). Along the out-of-plane direction, spins are arranged antiferromagnetically within one chemical unit cell (lattice parameter c), but have no net magnetic moment along the c-axis (Fig. 1a)6,7. For a collinear Ising antiferromagnet with second-order (or weakly first order) magnetic phase transition, magnetic critical scattering with moments polarized along the longitudinal (parallel to the ordered moment or a-axis) direction should diverge at TN, while spin fluctuations with moments polarized transverse to the ordered moment (b- and c-axis) direction should not diverge28,29,30,31,32. Unpolarized33 and polarized34 neutron scattering experiments on strain-free BaFe2As2 confirm this expectation. While the longitudinal component (Ma) of the magnetic critical scattering, defined as low-energy spin fluctuations polarized along the a-axis direction, diverges at TN, the transverse components Mb and Mc along the b- and c-axis, respectively (Fig. 1c, d), do not diverge at TN.

Effect of uniaxial pressure on lattice parameters of BaFe2As2

The in-plane uniaxial pressure-induced tetragonal symmetry-breaking lattice distortion [δ(P ≠ 0) − δ(P = 0), where δ = (a − b)/(a + b)] has a Curie–Weiss temperature dependence in the paramagnetic state and peaks near TN/Ts, but is greatly suppressed below TN/Ts when the intrinsic orthorhombic lattice distortion of BaFe2As2 sets in (Fig. 1g)27. In the paramagnetic state, NMR experiments on BaFe2As2 suggest that an in-plane uniaxial strain can induce a diverging c-axis polarized spin susceptibility \({\chi }_{c}^{^{\prime\prime} }\), which equals to Mc in the zero energy limit, on approaching TN/Ts26. Since c-axis polarized low-energy spin fluctuations do not diverge around TN/Ts in the strain-free BaFe2As234, it is important to confirm the NMR results and determine if the diverging \({\chi }_{c}^{^{\prime\prime} }\) is a precursor of a new magnetic order with a component along the c-axis (Fig. 1f)28.

Neutron polarization analysis of spin excitations in detwinned BaFe2As2

Our polarized neutron scattering experiments were carried out on the CEA CRG-IN22 triple-axis spectrometer equipped with Cryopad capability at the Institut Laue-Langevin and the BT-7 triple-axis spectrometer at the NIST Center for Neutron Research. The experimental setup for IN22 has been described in detail before34,35,36,37,38,39, while polarized neutrons were controlled and analyzed using a polarized 3He filter on BT-740,41. We have also carried out unpolarized neutron diffraction experiments on BT-7 using an in-situ uniaxial pressure device25. The wave vector transfer Q in reciprocal space in Å−1 is defined as Q = Ha* + Kb* + Lc*, with \({{\bf{a}}}^{* }=(2\pi /a)\hat{{\bf{a}}}\), \({{\bf{b}}}^{* }=(2\pi /b)\hat{{\bf{b}}}\), and \({{\bf{c}}}^{* }=(2\pi /c)\hat{{\bf{c}}}\), where a ≈ b ≈ 5.6 Å, c = 12.96 Å, and H, K, L are Miller indices. In this notation, the collinear AF structure of BaFe2As2 in Fig. 1a gives magnetic Bragg peaks at (H, K, L) = (1, 0, L) with L = 1, 3, … . The magnetic responses of the system at a particular Q along the orthorhombic lattice a-, b-, and c-axis directions are marked as Ma, Mb, and Mc, respectively (Fig. 1a–d). The scattering plane is [H, 0, L]. The incident neutrons are polarized along the Q (x), perpendicular to Q but in the scattering plane (y), and perpendicular to both Q and the scattering plane (z) (Fig. 1c). In this geometry, the neutron spin-flip (SF) scattering cross sections \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), \({\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), and \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) are related to the components Ma, Mb, and Mc via \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}=\frac{R}{R+1}{M}_{y}+\frac{R}{R+1}{M}_{z}+B\), \({\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}=\frac{1}{R+1}{M}_{y}+\frac{R}{R+1}{M}_{z}+B\), and \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}=\frac{R}{R+1}{M}_{y}+\frac{1}{R+1}{M}_{z}+B\), where R is the flipping ratio (\(R={\sigma }_{\mathrm{Bragg}\,}^{\mathrm{NSF}\,}/{\sigma }_{\mathrm{Bragg}\,}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\approx 13\)), B is the background scattering, \({M}_{y}={\sin }^{2}\alpha {M}_{a}+{\cos }^{2}\alpha {M}_{c}\) with α being the angle between [H, 0, 0] and Q, and Mz = Mb (Fig. 1d)34,35,36,37,38,39.

Figure 1b compares the temperature dependencies of the (1, 0, 3) magnetic Bragg peak for strain-free and strained BaFe2As2. At zero external pressure (P = 0 and strain-free), the magnetic scattering shows an order parameter like increase below TN = 136 K34. When an uniaxial pressure of P ≈ 20 MPa is applied along the b-axis of BaFe2As2, the Néel temperature of the sample increases to TN = 143 K25. The vanishingly small magnetic scattering intensity at Q = (0, 1, 3) suggests that the sample is essentially ~100% detwinned (Fig. 1b).

Figure 2a, b shows the energy dependence of \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), \({\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), and \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) in the zero pressure paramagnetic state at T ≈ 1.015TN ≈ 138 K for magnetic positions (1, 0, 1) and (1, 0, 3)34. Figure 2c, d shows identical scans as those of Fig. 2a, b, respectively, in the paramagnetic state at T ≈ 1.014TN ≈ 145 K with uniaxial pressure of P ≈ 20 MPa. Comparison of the Fig. 2a, c reveals that \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) is clearly larger than \({\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) below ~5 meV in the uniaxial strained sample. Since the (1, 0, 1) peak corresponds to α1 = 23.4° giving My ≈ 0.16Ma + 0.84Mc (Fig. 1d)34, the increased \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) in strained BaFe2As2 is mostly due to the increased Mc. For the (1, 0, 3) peak, which corresponds to α2 = 52.4°, My ≈ 0.63Ma + 0.37Mc, and the scattering is therefore much less sensitive to strain-induced changes in Mc. To conclusively determine the effect of uniaxial pressure on Mc, we consider \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}-{\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\propto {M}_{y}-{M}_{b}\). Since Mb (or \({\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\)) does not diverge at TN or change as a function of uniaxial pressure as seen in NMR26 and neutron polarization analysis (Fig. 2a–d), the effect of uniaxial pressure can be seen directly from the energy dependence of \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}-{\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) at (1, 0, 1) (Fig. 2e) and (1, 0, 3) (Fig. 2f). Without uniaxial pressure, \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}-{\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) does not diverge at the Q1 = (1, 0, 1) position but diverges at Q2 = (1, 0, 3) at low energies consistent with the expectation that spin fluctuations at (1, 0, 1) are mostly probing Mc. With uniaxial pressure, we see clear divergence of low-energy spin fluctuations at (1, 0, 1) below ~5 meV, thus unambiguously confirming the uniaxial pressure-induced Mc enhancement around TN observed in NMR experiments26. To further clarify the energy dependence of Ma, Mb, and Mc, we estimate these components from measurements at the (1, 0, 1) and (1, 0, 3) positions as described in ref. 34. By comparing the energy dependence of Ma, Mb, and Mc in strain-free (Fig. 2g) and strained (Fig. 2h) BaFe2As2, we again see that the effect of uniaxial strain is to enhance Mc below about 4 meV, consistent with the NMR measurements which probe Mc or \({\chi }_{c}^{^{\prime\prime} }\) in the zero energy limit26.

Energy scans of \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) (red circle), \({\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) (green diamond), and \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) (blue square) under a, b P = 0 and T = 138 K34 and c, d ~20 MPa and T = 145 K at the two AF wave vectors Q1 = (1, 0, 1) and Q2 = (1, 0, 3). e, f Comparison of P = 0 and P ≈ 20 MPa \(({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}-{\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,})\) at (1, 0, 1) and (1, 0, 3). g, h Energy dependence of Ma, Mb, and Mc extracted from the raw data in (a–d). The solid lines are guides to the eyes and the error bars represent 1 standard deviation.

To further demonstrate the effect of uniaxial strain on the magnetic critical scattering of BaFe2As2, we show in Fig. 3 the temperature dependence of \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), \({\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), and \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) at E = 2 meV for the strain-free (Fig. 3a, b)34 and strained (Fig. 3c, d) samples. At Q1 = (1, 0, 1), uniaxial strain clearly enhances \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) around TN/Ts, where \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\approx {M}_{y}\approx 0.16{M}_{a}+0.84{M}_{c}\), again consistent with the strain enhanced \({\chi }_{c}^{^{\prime\prime} }\) in the NMR measurements26. Figure 3b, d shows similar measurements at Q2 = (1, 0, 3), which reveal much less enhancement of \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) because \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\approx {M}_{y}\approx 0.63{M}_{a}+0.37{M}_{c}\). Figure 3e shows temperature dependence of \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}-{\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) across TN at the (1, 0, 1) peak without and with uniaxial pressure. Since spin fluctuations at the (1, 0, 1) position are mostly sensitive to Mc, we see no divergence across TN in zero pressure case. Upon application of a ~20 MPa uniaxial pressure, the scattering clearly reveals a diverging behavior at the pressured enhanced TN (solid vertical line) (Fig. 3e). Similar measurements at the (1, 0, 3) position, which is more sensitive to Ma, show diverging magnetic scattering at TN with and without uniaxial pressure consistent with the NMR results (Fig. 3f)26. Figure 3g, h shows the temperature dependencies of the estimated Ma, Mb, and Mc for strain-free and strained BaFe2As2, respectively, using the data in Fig. 3a–d. Comparing with the normal behavior of the strain-free BaFe2As2 (Fig. 3g), the Mc in strained BaFe2As2 clearly diverges around TN/Ts (Fig. 3h), although the relative uncertainties appear more significant for Ma, Mb, and Mc due to the propagation of errors (see Supplementary information for additional data and analysis).

Temperature dependence of \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), \({\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), and \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) at E = 2 meV of a, b uniaxial pressure-free34 and c, d pressured (P ≈ 20 MPa) BaFe2As2 at a, c (1, 0, 1) and b, d (1, 0, 3). e, f Comparison of P = 0 and P ≈ 20 MPa \(({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}-{\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,})\) at Q1 = (1, 0, 1) and Q2 = (1, 0, 3). Temperature dependence of Ma, Mb, and Mc at E = 2 meV for g uniaxial pressure-free and h pressured sample estimated from the data in (a–d). The dotted and solid lines are guides to the eye and the error bars represent 1 standard deviation. The vertical dashed and solid lines mark TN/Ts at P = 0 and P ≈ 20 MPa, respectively.

Effect of uniaxial pressure on static AF order of BaFe2As2

In principle, a diverging dynamic spin susceptibility in the paramagnetic state of a system is an indication of the eventual magnetic order below TN28,29,30,31,32. For strain-free BaFe2As2, the magnetic ordered moment is along the a-axis with no net moment along the b-axis and c-axis directions6,7. Therefore, only the Ma component of the spin susceptibility diverges at TN (Fig. 3e–g)34. The observation of a diverging Mc in strained BaFe2As2, in addition to the usual diverging Ma (Fig. 3e, f, h), suggests that the applied strain may induce static magnetic ordered moment along the c-axis. To test this hypothesis, we carried out polarized neutron diffraction measurements on BaFe2As2 as a function of uniaxial pressure, focusing on the temperature and neutron polarization dependence of the scattering at Q = (1, 0, L) with L = 0, 1, 2, 3, and 5. At wave vectors (1, 0, 0) and (1, 0, 2), there is no evidence of magnetic scattering, consistent with uniaxial pressure-free BaFe2As2 (see Supplementary information for additional data and analysis).

Figure 4a, b shows θ/2θ scans of \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) around Q1 = (1, 0, 1) and Q2 = (1, 0, 3), respectively, at different temperatures. Since \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) at these two wave vectors probes different combinations of Ma and Mc, one can obtain magnitudes of the static ordered moments along the a-axis and c-axis directions at these temperatures. Figure 4c shows the temperature dependencies of the full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of these peaks, indicating that the spin–spin correlation lengths are instrumental resolution limited and temperature independent. Figure 4d plots the magnetic scattering intensity ratio between (1, 0, 1) (I101) and (1, 0, 3) (I103), which measures the relative strength of Mc and reveals a clear peak around TN/Ts.

Elastic θ/2θ scans of \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) across a Q1 = (1, 0, 1) and b Q2 = (1, 0, 3) at different temperatures and P = 20 MPa. The data are collected on BT-7 using final neutron energy of 14.7 meV with instrumental energy resolution of about 1.3 meV. Similar scans of \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) are discussed in Supplementary information for additional data and analysis. \({\sigma }_{y}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) was unavailable at the time of this experiment. c FWHM of the elastic (1, 0, 1) and (1, 0, 3) scans across TN/Ts. d Temperature dependence of I101/I103 ∝ (0.16Ma + 0.84Mc)/(0.63Ma + 0.37Mc). e Temperature dependence of I101/I103 at P ≈ 0 and ~ 45 MPa uniaxial pressure obtained using in-situ uniaxial pressure device with unpolarized neutrons on BT-7. f Pressure dependence of I101/I103 (red symbols, left axis) and Mc/Ma (green symbols, right axis) at T ~ 142 K. The data points for P = 0 and 45 MPa were measured with unpolarized neutron scattering. The data points for P = 20 Mpa were measured with polarized mode with the open (solid) symbols obtained from \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) (\({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\)). The black dashed curve is a guide to the eye for the data points. unpol. denotes unpolarized neutron scattering measurements. The vertical error bars in (a, b, d, e) represent statistical errors of 1 standard deviation. The error bars in (c) are estimated errors from fits to magnetic Bragg peak widths. The error bars in (f) are our estimated errors from fits to magnetic order parameters and applied uniaxial pressure.

To further determine the effect of uniaxial pressure on c-axis ordered moment and its pressure dependence, we carried out unpolarized neutron diffraction measurements focusing on the magnetic scattering intensity ratio between (1, 0, 1) (I101) and (1, 0, 3) (I103) using an in-situ uniaxial pressure device. Since our polarized neutron diffraction measurements revealed no ordered moment Mb, we used unpolarized neutron diffraction on BT-7 to improve the statistics of the data across TN. Figure 4e compares the measured I101/I103 from 130 to 150 K at P ≈ 0 and 45 MPa uniaxial pressure. Consistent with earlier work6,7, I101/I103 is approximately temperature-independent across TN at P ≈ 0, thus indicating that the internal strain of the system does not induce a c-axis ordered moment. Upon applying an uniaxial pressure of P ≈ 45 MPa, the identical measurement shows a dramatic peak at TN, thus confirming the results of Fig. 4a–d. Figure 4f shows the uniaxial pressure dependence of the measured Mc/Ma at TN, suggesting that the ordered c-axis moment saturates with increasing pressure above 45 MPa.

Figure 1f shows the temperature dependencies of the magnetically ordered moments along the a-axis (Ma) and c-axis (Mc) directions obtained by comparing \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) and \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) at wave vectors Q1 = (1, 0, 1) and Q2 = (1, 0, 3) (see Supplementary information for additional data and analysis). In the low-temperature AF ordered state, the strain-free and strained BaFe2As2 have the standard collinear AF structure with no evidence of Mc (right panel in Figs. 1e and 4e)6,7. On warming to 143 K just below TN, the easy axis tilts from the a-axis toward the c-axis with an angle of ~28° (middle panel in Fig. 1e). Finally, on warming to temperatures well above TN, there is no static AF order (left panel in Fig. 1e). Figure 1g shows the temperature dependence of Mc at ~20 (blue solid line) and ~45 (pink solid line) MPa uniaxial pressure, compared with the uniaxial strain-induced lattice distortion δ(P ≈ 20 MPa) − δ(P = 0) (green solid circles and lines) obtained from neutron Larmor diffraction experiments27. The similarity of the data suggests that the c-axis aligned magnetic moment arises from the uniaxial pressure-induced lattice distortion.

Discussion

Theoretically, the in-plane electronic anisotropy of the iron pnictides is expected to couple linearly to the lattice orthorhombicity by the Ginzburg–Landau free-energy formalism if one ignores the effect of spin-orbit coupling induced magnetic anisotropy9,27. From this perspective, in-plane uniaxial strain should only induce in-plane electronic anisotropy. The discovery of a c-axis ordered magnetic moment coupled exclusively with uniaxial pressure-induced lattice distortion suggests that such an effect cannot be only associated with the lattice orthorhombicity of the system, as Mc becomes vanishingly small in the low-temperature orthorhombic phase with large in-plane lattice distortion. This is also different from the c-axis moment AF structure in Ba1−xKxFe2As2 in the sense that the c-axis order appears exclusively in the tetragonal phase42,43, while the c-axis moment appears in BaFe2As2 only near the peak of the nematic susceptibility around TN/Ts. Although there is currently no theoretical understanding of this observation, it must arise from spin-orbit coupling induced magnetic anisotropy44. Our discovery opens a new avenue to control magnetic order in nematic materials using mechanical strain instead of magnetic fields. The strong coupling of the c-axis aligned magnetic order with an in-plane pressure-induced lattice distortion offers the potential for the next generation of mechanical-strain-controlled magnetic switches. One must consider the presence of the magnetically ordered moment along the c-axis in mechanically detwinned iron pnictides in order to understand their intrinsic electronic, magnetic, and nematic properties.

Alternatively, our observations are also consistent with strain inducing a proximate XY spin anisotropy near TN/Ts. In this scenario, while a-axis is energetically favorable in terms of spin anisotropy, c-axis is very close in energy. This allows for a distribution of large (resolution-limited but not long-range ordered) and long-lived (quasi-static) collinear magnetic domains, with their collinear spin direction in the ac-plane. The ratio between I101/I103 (Fig. 4d, e) is then a measure of the distribution of domains, reflective of the difference in spin anisotropy energies along the a- and c-axis. Similar to when the easy axis tilts from a-axis toward c-axis under strain (Fig. 1e), the change to a proximate XY spin anisotropy under strain also indicates a large and highly unusual effect of strain on the spin anisotropy.

In conclusion, we have used polarized and unpolarized neutron scattering to study the magnetic structure and critical scattering in uniaxial strained BaFe2As2. We find that the uniaxial pressure necessary to make single domain samples of BaFe2As2 also induces c-axis polarized critical magnetic scattering and static magnetic order around TN/Ts. The size of the c-axis ordered moment is associated with the uniaxial pressure-induced lattice distortion, instead of the lattice orthorhombicity. These results indicate that in addition to detwinning BaFe2As2, uniaxial pressure applied on the sample actually modifies the magnetic structure of the system. Therefore, infrared45, angle resolved photoemission16, and Raman spectroscopy46,47 experiments on mechanically detwinned BaFe2As2 near the magnetic and nematic phases should be reexamined to take into account the effect of strain-induced change to the spin anisotropy on the in-plane electronic and magnetic properties.

Methods

Sample preparation and experimental details

BaFe2As2 single crystals were grown by the self-flux method using the same growth procedure as described before19. Our polarized inelastic neutron scattering experiments were carried out using the CEA CRG-IN22 triple-axis spectrometer at the Institut Laue-Langevin, Grenoble, France (All raw data from ILL will be published at https://doi.org/10.5291/ILL-DATA.4-02-531, and from NCNR will be provided upon request). Polarized neutrons were produced using a focusing Heusler monochromator and analyzed with a focusing Heusler analyzer with a final wave vector of kf = 2.662 Å−1. The experimental setups for uniaxial pressured and pressure freed experiments are identical. However, it is difficult to directly compare the scattering intensity of these two experiments since the sample masses, their relative positions in the beam, and background scattering of these two experiments are different. Nevertheless, one can safely compare the relative intensity changes of these two experiments. The polarized elastic neutron scattering experiments were carried out on BT-7 utilizing 3He polarizers immediately before and after the sample at NIST center for neutron research, Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA40,41. The unpolarized neutron diffraction experiments in Fig. 4e were carried out using a pyrolytic graphite monochromator and analyzer with pyrolytic graphite filter in the beam. Experiments on twinned BaFe2As2 without external uniaxial pressure were performed on ~12-g aligned single crystals as described before34. The polarized inelastic neutron scattering experiments on uniaxial pressured detwinned BaFe2As2 were performed using 12 pieces cut single crystals (~3 g, Fig. S1)21. The BT-7 measurements were carried out on a single piece of BaFe2As2 mounted on a newly built in-situ uniaxial pressure device and the neutron wave vectors are set at ki = kf = 2.662 Å−1.

Determination of Ma, Mb, and Mc

In our previous polarized neutron scattering studies of iron pnictides, we have established the method for determining the spin-fluctuation components Mβ (β = a, b, c) along the lattice axes via comparing the SF scattering \({\sigma }_{\gamma }^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) (γ = x, y, z) at two equivalent magnetic wave vectors (such as Q1 = (1, 0, 1) and Q2 = (1, 0, 3) as shown in Fig. 1 of the main text). The definition of the directions x, y, and z is described in Fig. 1. \({\sigma }_{\gamma }^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) is directly related to the spin-fluctuation components by:

where α is the angle between (1, 0, 0) and Q (Fig. 1), F(Q) is magnetic form factor of Fe2+, R is the flipping ratio (\(R={\sigma }_{\mathrm{Bragg}\,}^{\mathrm{NSF}\,}/{\sigma }_{\mathrm{Bragg}\,}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\approx 13\)), and B is the polarization-independent background scattering.

From Eq. (1), we can get four equations for our results on Q1 and Q2:

in which r is the intensity ratio factor between Q1 and Q2 to account for the differences in sample illumination volume and the convolution with instrumental resolution. The third and fourth equations in Eq. (2) can be used to determine the ratio r and Mb, and the first two equations for Ma and Mc. More details concerning the determination of the spin-fluctuation components Ma, Mb, and Mc can be found elsewhere39. Although this method can determine the values of Ma, Mb, and Mc, it also results in large error bars of their values. To more accurately determine the effect of uniaxial pressure on Ma and Mc, we consider the differences between \({\sigma }_{z}^{{\rm{SF}}}({\bf{Q}})-{\sigma }_{y}^{{\rm{SF}}}({\bf{Q}})\) at Q1 and Q2.

As Mb does not diverge in uniaxial pressured and pressure-free cases26, a comparison of \({\sigma }_{z}^{{\rm{SF}}}({{\bf{Q}}}_{1})-{\sigma }_{y}^{{\rm{SF}}}({{\bf{Q}}}_{1})\) raw data should be most sensitive to changes in Mc, while \({\sigma }_{z}^{{\rm{SF}}}({{\bf{Q}}}_{2})-{\sigma }_{y}^{{\rm{SF}}}({{\bf{Q}}}_{2})\) should be sensitive to changes in both Ma and Mc. The outcome of this analysis is shown in Figs. 2e, f and 3e, f.

In our polarized neutron diffraction experiment at BT-7, we have only measured \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) and \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\). In elastic channel, Mβ is proportional to the square of the ordered moment (mβ). The determination of Mβ follows the same method as described in Eqs. (1) and (2). But we need to apply the Lorentz factor (\(L=\frac{1}{\sin 2\theta }\)) as we use the integrated intensity of θ − 2θ scan to calculate Mβ48, where 2θ is the scattering angle for Q. Moreover, since no divergence of critical spin fluctuations were observed along the b-axis, we can assume the absence of static ordered moment (Mb = 0) (even if we consider that quasi-elastic spin fluctuations along b-axis within the energy resolution of the elastic scattering could be included in \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) and \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), it can be neglected at least in \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) because of the small pre-factor \(\frac{1}{R+1}\approx 0.07\) before Mb). Then Eq. (2) can be written as:

Given the magnetic moment is polarized along a-axis at 40 K ≪ TN with ma ≈ 0.87μB, we can get r, solve Ma and Mc from both \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) and \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), and determine the magnitude of the c-axis moment induced by uniaxial strain. Taking ma = 0.87μB at 40 K, we can get ma and mc at other temperatures using the data points shown in Fig. 1f. From \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\), we get ma ≈ 0.23 ± 0.05μB and mc ≈ 0.12 ± 0.03μB at 143 K, resulting in a canting angle of ~28° at this critical temperature. The calculated canting angles are estimated to be about 14° at 140 and 149 K, and gradually decrease to zero below 135 K.

\({\sigma }_{x,y,z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) and Ma,b,c below and well above TN at the AF ordering wave vectors

Figure S2 shows the results of \({\sigma }_{\gamma }^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) (γ = x, y, z) below and well above TN under zero and P ~ 20 MPa. At T = 135 K (<TN), \({\sigma }_{\gamma }^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) for uniaxial pressure-free and pressured cases are shown in Fig. S2a–d. A comparison of \({\sigma }_{z}^{{\rm{SF}}}({{\bf{Q}}}_{1})-{\sigma }_{y}^{{\rm{SF}}}({{\bf{Q}}}_{1})\) scattering at P = 0 and ~20 MPa in Fig. S2e suggests that the applied uniaxial pressure may enhance Mc around ~8 meV. Similar data at Q2 in Fig. S2f suggest that the effect of uniaxial pressure is limited on Ma at this temperature. Figure S2g, h shows as the converted Ma, Mb, and Mc at T = 135 K. At T < TN, the data with P ~ 20 MPa are qualitatively consistent with that measured on the P = 0 sample, except that both the Ma and Mb are gapped below E > 10 meV and ~6 meV, respectively, while only Ma is gapped below 6 meV for the P = 0 sample. Note TN is ~136 K for P = 0 and ~143 K for P ~ 20 MPa. In relative temperature T/TN, 135 K is much lower in the P ~ 20 MPa sample (0.94TN) than that in free-standing sample (0.99TN), thus the spin fluctuations are further gapped. For temperatures well above TN (Fig. S2i–p), SF scattering becomes very weak and no qualitative difference was observed for P = 0 and P ~ 20 MPa.

Comparison of Mβ at Q = (1, 0) and (0, 1)

To determine if the uniaxial pressure-induced Mc at the AF wave vector Q = (1, 0) is compensated by magnetic scattering reduction at (0, 1), we compare \({\sigma }_{\gamma }^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) between Q = (1, 0, L) and (0, 1, L)(L = 1, 3) at T = 145 K (Fig. S3a–d). Figure S3e, f shows the energy dependence of \({\sigma }_{z}^{{\rm{SF}}}({\bf{Q}})-{\sigma }_{y}^{{\rm{SF}}}({\bf{Q}})\) at Q = (1, 0, 1)/(0, 1, 1) and Q = (1, 0, 3)/(0, 1, 3), respectively. Compared with clear magnetic intensity gains below ~ 6 meV at the AF wave vectors Q1 = (1, 0, 1) and Q2 = (1, 0, 3), paramagnetic scattering at Q = (0, 1, 1) and (0, 1, 3) is isotropic in spin space as illustrated by the zero values of \({\sigma }_{z}^{{\rm{SF}}}({\bf{Q}})-{\sigma }_{y}^{{\rm{SF}}}({\bf{Q}})\) at these wave vectors. Figure S3g, h shows the energy dependence of Ma, Mb, and Mc extracted from Fig. S3a–d at the wave vectors (1, 0) and (0, 1), respectively. Therefore, the applied uniaxial pressure clearly has an impact on magnetic excitations at (1, 0) but has no observable effect at (0, 1), which has weak and featureless energy dependence of isotropic Ma, Mb, and Mc (Fig. S3h).

Consistent with the weak scattering at (0, 1, L) observed at 145 K, temperature dependence of Ma, Mb, and Mc at Q = (0, 1) is much weaker than that at (1, 0, L) and decreases in intensity at TN (Fig. S4), consistent with the temperature dependence of (0, 1, 1) in detwinned BaFe2As2 measured with unpolarized neutron scattering21.

Uniaxial pressure dependence of the magnetic order and correlations

Figure S5 summarizes the elastic θ − 2θ scans of \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) across Q = (1, 0, L)(L = 1, 2, 3). Similar to the θ − 2θ scans of \({\sigma }_{z}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) as described in Fig. 4 of the main text, the scans for \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}\) (Fig. S5a, b) exhibit temperature-independent FWHM from 40 to 143 K (Fig. S5c), indicating that the spin–spin correlation length is resolution limited even in the temperature range above TN ~ 136 K of unstrained sample. Figure S5d plots the ratio between the scattering intensity at (1, 0, 1) and (1, 0, 3) (I101/I103), which is greatly enhanced close to TN. Since \({\sigma }_{x}^{\mathrm{SF}\,}=0.16{M}_{a}+0.84{M}_{c}\) at Q1 = (1, 0, 1) and 0.37Ma + 0.37Mc at Q2 = (1, 0, 3), the enhancement of I101/I103 is consistent with the emergence of a c-axis magnetic moment induced by uniaxial strain. At temperature where Mc is not induced, the ratio \({I}_{101}/{I}_{103}=0.16{M}_{a}/0.63{M}_{a}\times \frac{{\sin }^{2}2{\theta }_{2}}{{\sin }^{2}2{\theta }_{1}}\approx 0.5\) (black dashed line in Fig. S5d), where \(\frac{{\sin }^{2}2{\theta }_{2}}{{\sin }^{2}2{\theta }_{1}}\) accounts for the Lorentz factor. The data points of I101/I103 in Fig. S5d show that Mc is absent at 149 K and below 135 K but reaches a maximum at 143 K close to TN. The unpolarized data in Fig. 4f show similar behavior.

In addition to the emergence of Mc, it is also important to understand whether Mc forms a new periodicity along c-axis. The magnetic structure factor of the three-dimensional AF order of BaFe2As2 results in magnetic peaks at (1, 0, L) with L = 1, 3, 5, … and the absence of magnetic scattering at (1, 0, L) with L = 0, 2, 4, … . If the induced Mc forms a larger magnetic unit cell along c-axis that ensures the presence of (1, 0, 1) and (1, 0, 3), one can expect detectable magnetic scattering at L = 0, 2. However, the three-point θ − 2θ across (1, 0, 2) in Fig. S5 shows that the intensity for (1, 0, 2) is smaller than 1/3000 of (1, 0, 3), which rules out this possibility and further confirm our conclusion about the canting-moment picture as shown in Fig. 1 of the main text.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request, and all raw data from ILL will be published at https://doi.org/10.5291/ILL-DATA.4-02-531, and from NCNR will be provided upon request.

References

Hosono, H. & Kuroki, K. Iron-based superconductors: Current status of materials and pairing mechanism. Phys. C 514, 399 (2015).

Johnston, D. C. The puzzle of high temperature superconductivity in layered iron pnictides and chalcogenides. Adv. Phys. 59, 803 (2010).

Stewart, G. R. Superconductivity in iron compounds. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1589 (2011).

Scalapino, D. J. A common thread: The pairing interaction for unconventional superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1383 (2012).

Dai, P. C. Antiferromagnetic order and spin dynamics in iron-based superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 855 (2015).

Huang, Q. et al. Neutron-diffraction measurements of magnetic order and a structural transition in the parent BaFe2As2 compound of FeAs-based high-temperature superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 257003 (2008).

Kim, M. G. et al. Character of the structural and magnetic phase transitions in the parent and electron-doped BaFe2As2 compounds. Phys. Rev. B 83, 134522 (2011).

Fernandes, R. M., Chubukov, A. V. & Schmalian, J. What drives nematic order in iron-based superconductors? Nat. Phys. 10, 97–104 (2014).

Böhmer, A. E. & Meingast, C. Electronic nematic susceptibility of iron-based superconductors. C. R. Phys. 17, 90–112 (2016).

Fisher, I. R., Degiorgi, L. & Shen, Z. X. In-plane electronic anisotropy of underdoped ‘122’ Fe-arsenide superconductors revealed by measurements of detwinned single crystals. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 124506 (2011).

Chu, J. -H. et al. In-plane resistivity anisotropy in an underdoped iron arsenide superconductor. Science 329, 824–826 (2010).

Chu, J.-H., Kuo, H.-H., Analytis, J. G. & Fisher, I. R. Divergent nematic susceptibility in an iron arsenide superconductor. Science 337, 710–712 (2012).

Tanatar, M. A. et al. Uniaxial-strain mechanical detwinning of CaFe2As2 and BaFe2As2 crystals: optical and transport study. Phys. Rev. B 81, 184508 (2010).

Man, H. et al. Electronic nematic correlations in the stress-free tetragonal state of BaFe2−xNixAs2. Phys. Rev. B 92, 134521 (2015).

Tam, D. W. et al. Weaker nematic phase connected to the first order antiferromagnetic phase transition in SrFe2As2 compared to BaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134519 (2019).

Yi, M., Zhang, Y., Shen, Z.-X. & Lu, D. H. Role of the orbital degree of freedom in iron-based superconductors. npj Quantum Mater. 2, 57 (2017).

Pfau, H. et al. Detailed band structure of twinned and detwinned BaFe2As2 studied with angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 99, 035118 (2019).

Watson, M. D. et al. Probing the reconstructed Fermi surface of antiferromagnetic BaFe2As2 in one domain. npj Quantum Mater. 4, 36 (2019).

Lu, X. et al. Nematic spin correlations in the tetragonal state of uniaxial-strained BaFe2−xNixAs2. Science 345, 657–660 (2014).

He, M. et al. Dichotomy between in-plane magnetic susceptibility and resistivity anisotropies in extremely strained BaFe2As2. Nat. Comm. 8, 504 (2017).

Lu, X. et al. Spin waves in detwinned BaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 067002 (2018).

Dhital, C. et al. Effect of uniaxial strain on the structural and magnetic phase transitions in BaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 087001 (2012).

Dhital, C. et al. Evolution of antiferromagnetic susceptibility under uniaxial pressure in Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2. Phys. Rev. B 89, 214404 (2014).

Song, Y. et al. Uniaxial pressure effect on structural and magnetic phase transitions in NaFeAs and its comparison with as-grown and annealed BaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 87, 184511 (2013).

Tam, D. W. et al. Uniaxial pressure effect on the magnetic ordered moment and transition temperatures in BaFe2−xTxAs2 (T = Co,Ni). Phys. Rev. B 95, 060505 (2017).

Kissikov, T. et al. Uniaxial strain control of spin-polarization in multicomponent nematic order of BaFe2As2. Nat. Comm. 9, 1058 (2018).

Lu, X. et al. Impact of uniaxial pressure on structural and magnetic phase transitions in electron-doped iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 93, 134519 (2016).

Collins, M. F. Magnetic Critical Scattering (Oxford University Press, New York, 1989).

Birgeneau, R. J., Guggenheim, H. J. & Shirane, G. Neutron scattering investigation of phase transitions and magnetic correlations in the two-dimensional antiferromagnets K2NiF4, Rb2MnF4, Rb2FeF4. Phys. Rev. B 1, 2211 (1970).

Als-Nielsen, J., Birgeneau, R. J., Guggenheim, H. J. & Shirane, G. Spin dynamics and critical fluctuations in a two-dimensional random antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 12, 4963 (1975).

Schulhof, M. P., Nathans, R., Heller, P. & Linz, A. Inelastic neutron scattering from MnF2 in the critical region. Phys. Rev. B 4, 2254 (1971).

Tseng, K. F., Keller, T., Walters, A. C., Birgeneau, R. J. & Keimer, B. Neutron spin-echo study of the critical dynamics of spin-5/2 antiferromagnets in two and three dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 94, 014424 (2016).

Wilson, S. D. et al. Antiferromagnetic critical fluctuations in BaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 82, 144502 (2010).

Li, Y. et al. Spin excitation anisotropy in the paramagnetic tetragonal phase of BaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 020404 (2017).

Lipscombe, O. J. et al. Anisotropic neutron spin resonance in superconducting BaFe1.9Ni0.1As2. Phys. Rev. B 82, 064515 (2010).

Qureshi, N. et al. Anisotropy of incommensurate magnetic excitations in slightly overdoped Ba0.5K0.5Fe2As2 probed by polarized inelastic neutron scattering experiments. Phys. Rev. B 90, 100502 (2014).

Wang, C. et al. Longitudinal spin excitations and magnetic anisotropy in antiferromagnetically ordered BaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. X 3, 041036 (2013).

Song, Y. et al. In-plane spin excitation anisotropy in the paramagnetic state of NaFeAs. Phys. Rev. B 88, 134512 (2013).

Zhang, C. et al. Anisotropic neutron spin resonance in underdoped superconducting NaFe1−xCoxAs. Phys. Rev. B 90, 140502 (2014).

Lynn, J. W. et al. Double-focusing thermal triple-axis spectrometer at the NCNR. J. Res. Natl Inst. Stand. Technol. 117, 61–79 (2012).

Chen, W. C. et al. 3He spin filters for a thermal neutron triple axis spectrometer. Phys. B 397, 168–171 (2007).

Avci, S. et al. Magnetically driven suppression of nematic order in an iron-based superconductor. Nat. Comm. 5, 3845 (2014).

Allred, J. M. et al. Double-Q spin-density wave in iron arsenide superconductors. Nat. Phys. 12, 493–498 (2016).

Scherer, D. D. & Andersen, B. M. Spin-orbit coupling and magnetic anisotropy in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 037205 (2018).

Nakajima, M. et al. Unprecedented anisotropic metallic state in undoped iron arsenide BaFe2As2 revealed by optical spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 12238 (2011).

Ren, X. et al. Nematic crossover in BaFe2As2 under uniaxial stress. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 197002 (2015).

Baum, A. et al. Interplay of lattice, electronic, and spin degrees of freedom in detwinned BaFe2As2: a Raman scattering study. Phys. Rev. B 98, 075113 (2018).

Shirane, G., Shapiro, S. M. & Tranquada, J. M., In Neutron Scattering with a Triple-Axis Spectrometer 170 (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Acknowledgements

The work at BNU is supported by the NSFC under Grant No. 11922402 and 11734002 (X.L.). The work at Rice University is supported by the U.S. NSF DMR-1700081 and the Robert A. Welch Foundation Grant No. C-1839 (P.D.). The work at UCB was supported by the U.S. DOE BES under Contract No. DE-AC02-05-CH11231 within the Quantum Materials Program (KC2202).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.D. and X.L. conceived the project. P.L., M.L.K., L.T., G.T. and X.L. prepared the samples. Polarized inelastic neutron scattering experiments at IN22 were carried out by P.L., L.T., X.L., K.S., J.T.P., Y.L., Y.X.S., and F.B. Neutron diffraction measurements at BT-7 were carried out by M.L.K, Y.S., D.W.T., J.W.L, Y.Z., and R.J.B. The entire project was supervised by P.D. The paper was written by P.D., P.L., X.L., and Y.S. All authors made comments.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Jiun-Haw Chu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, P., Klemm, M.L., Tian, L. et al. In-plane uniaxial pressure-induced out-of-plane antiferromagnetic moment and critical fluctuations in BaFe2As2. Nat Commun 11, 5728 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19421-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19421-5

This article is cited by

-

Competing itinerant and local spin interactions in kagome metal FeGe

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Developing time-of-flight polarized neutron capability at the China Spallation Neutron Source

Nuclear Science and Techniques (2023)

-

Single-domain stripe order in a high-temperature superconductor

Communications Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.