Abstract

Utilising one-carbon substrates such as carbon dioxide, methane, and methanol is vital to address the current climate crisis. Methylotrophic metabolism enables growth and energy generation from methanol, providing an alternative to sugar fermentation. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an important industrial microorganism for which growth on one-carbon substrates would be relevant. However, its ability to metabolize methanol has been poorly characterised. Here, using adaptive laboratory evolution and 13C-tracer analysis, we discover that S. cerevisiae has a native capacity for methylotrophy. A systems biology approach reveals that global rearrangements in central carbon metabolism fluxes, gene expression changes, and a truncation of the uncharacterized transcriptional regulator Ygr067cp supports improved methylotrophy in laboratory evolved S. cerevisiae. This research paves the way for further biotechnological development and fundamental understanding of methylotrophy in the preeminent eukaryotic model organism and industrial workhorse, S. cerevisiae.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methylotrophic organisms are able to grow on one-carbon substrates such as carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, methane, or methanol and are important primary producers for Earth’s ecosystems as they fix inorganic carbon into biologically available organic carbon. These organisms and their underlying metabolic networks are becoming increasingly important in global efforts to mitigate climate change and reduce our reliance on non-renewable resources such as fossil fuels. Our current dependence on fossil fuels is not sustainable owing to finite reserves and negative environmental impacts from extraction and use. By-products from fossil fuel combustion include a myriad of toxic air pollutants and CO2, which is the main anthropogenic contributor to climate change. These complex environmental problems call for a global effort to move towards a bio-economy in which microbial metabolism is used for the conversion of renewable materials into useful products1. Typically, sugars derived from sugarcane or corn are used as feedstocks for the production of fuels and chemicals from microbial metabolism. However, sugar production can be prohibitively expensive2 and requires arable land.

As an alternative to sugars, one-carbon (C1) substrates are abundant and can be obtained from natural gas or waste resources such as agricultural, municipal or industrial waste3,4. Methanol is a particularly attractive one-carbon substrate owing to its abundance and liquid state, which makes it more compatible with existing fermentation, storage and transportation infrastructure3,5. Methanol can also be obtained from methane and carbon dioxide stemming from industrial waste streams6. Engineering microorganisms to convert C1 compounds such as methanol into food, fuels and chemicals has therefore become a major goal in the field of synthetic biology4,7.

Methylotrophic metabolism enables energy and biomass generation from methanol and is present in bacterial, archaeal and yeast species. Recent attempts have been made to produce valuable metabolites using methylotrophs. For example, Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 has been engineered to produce 3-hydroxypropionic acid from methanol8. The methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris (renamed Komagataella phaffii9) is currently used industrially for production of recombinant proteins10. Recently, P. pastoris has also been used for production of metabolites including astaxanthin and isobutanol from sugar11,12. However, relative to model organisms, most native methylotrophs lack the genetic tools and depth of characterisation necessary for the successful metabolic engineering of high-yield and heterologous pathways. An attractive alternative to enable the use of methanol as feedstock is to engineer synthetic methylotrophy into industrially robust and well-characterised microorganisms. Model organisms are easier to genetically manipulate, providing opportunities to engineer non-native central carbon metabolism with greater genetic and metabolic plasticity. Given our understanding of their metabolism, model organisms are also more amenable to gaining fundamental insights. Recent approaches have focused on engineering synthetic methylotrophy in bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Corynebacterium glutamicum13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Incorporation of 13C-methanol into central carbon metabolites and specialty products has been demonstrated in both species, with growth on methanol as the sole carbon source recently engineered in E. coli21.

Methanol-utilisation research on model eukaryotes such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been limited, although S. cerevisiae has distinct advantages over organisms such as E. coli for use in industrial fermentation. For example, S. cerevisiae can correctly express, fold and post-translationally modify eukaryotic proteins, is not susceptible to phage contamination, has high tolerance to low pH concentrations and solvents like methanol, and has organelles that can be co-opted for localisation of specialised metabolism22,23,24. Previously, our work identified a methanol-specific transcriptomic response in the laboratory strain CEN.PK as well as methanol-specific growth. This response was stronger than that of the laboratory strain S288C. Thus, we sought to further characterise methanol metabolism in CEN.PK using adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE). Here, we identify the native capacity of S. cerevisiae to assimilate methanol into central carbon metabolism. Using methanol-dependent growth assays and 13C-methanol tracer studies, we characterise and improve native methanol assimilation in S. cerevisiae.

Results

Methanol-specific growth and 13C-methanol tracer analysis reveals native methanol assimilation in S. cerevisiae

Our previous study compared two commonly used S. cerevisiae strains, S288C and CEN.PK 113-5D, for their transcriptional response and growth profile in the presence of methanol25. CEN.PK was identified as the superior candidate to engineer methylotrophy as it had better methanol tolerance and a distinct methanol-specific transcriptional response that included upregulation of genes involved in peroxisomal biogenesis (PEX11), alcohol oxidation (ADH2) and formate oxidation (FDH1). Having identified the potential for methanol-dependent growth and metabolism in S. cerevisiae25, methanol-specific growth of CEN.PK 113-5D was further assessed using controlled bioreactor fermentations. Previous work with E. coli has highlighted the importance of yeast extract for growth on liquid methanol media26. Liquid yeast nitrogen base (YNB) medium with and without 2% methanol and 0.1% yeast extract was therefore used to assess the effect of methanol on growth (Fig. 1a). The presence of methanol in the medium resulted in a final OD600 increase of 39% relative to yeast extract-only medium, confirming a methanol-specific growth increase in liquid medium containing yeast extract.

a Growth profile of CEN.PK 113-5D (with empty vector pRS416) grown in liquid YNB medium with 0.1% yeast extract (circles) or with 0.1% yeast extract and 2% methanol (squares). Data points represent the measurement of two independent biological replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. b Percentage of fully 13C-labelled intracellular metabolite pool relative to total metabolite pool in CEN.PK 113-5D. F1,6BP fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, G3P glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, RL5P ribulose-5-phosphate, DHAP dihydroxyacetone phosphate, CIT citrate, 3PG 3-phosphoglyceric acid, PEP phosphoenolpyruvate, ACCoA acetyl-coenzyme A. Data points are from two independent biological replicates with bars representing the mean, except for CEN.PK 113-5D F1,6BP, for which no 12 C metabolite was detected in one replicate. c 13C-ethanol was produced by CEN.PK 113-5D. The signal intensity was normalised to the inert gas nitrogen, and then to biomass. Data show 13C-ethanol intensity at 47 amu for two independent biological replicates with bars representing the mean. d Comparison of 12C-ethanol and 13C-ethanol intensities during growth in 13C-methanol. The signal intensity was normalised to the inert gas nitrogen, and then to biomass for each strain. Data show the individual technical measurements for 12C-ethanol and 13C-ethanol intensity at 31 and 33 amu, respectively, for two independent biological replicates with bars representing the mean. SEM, secondary electron multiplier, amu atomic mass unit. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further investigate the methanol response in S. cerevisiae and determine the extent to which methanol enters central carbon metabolism in the presence of the co-substrate yeast extract, a 13C-methanol tracer analysis was performed. Bioreactor off-gases such as 13C-methanol, 13C-CO2, CO2, 13C-ethanol and ethanol were measured in real-time using a mass spectrometer connected to the bioreactors. Intracellular metabolites were analysed using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). 13C-ethanol (Fig. 1c, d) and fully 13C-labelled intracellular metabolites involved in the pentose phosphate pathway, glycolysis, and the TCA cycle were also detected (Fig. 1b). 13C-fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and 13C-pyruvate could only arise through the conversion of 13C-methanol through central carbon metabolism (Fig. 1b), confirming S. cerevisiae has a native capacity for methanol assimilation. In particular, the identification of a high proportion of fully 13C-labelled metabolite in the case of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (33% of the metabolite pool) and of the structurally complex acetyl-CoA (60% of the metabolite pool) demonstrates methanol assimilation can occur in S. cerevisiae.

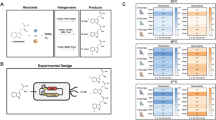

a Schematic of the ALE design. Three independent lineages of CEN.PK 113-5D (with pRS416) were grown in baffled shake flasks in condition A or B for 230 generations. Under condition A, cultures were passaged from YNB medium without amino acids and 1% glucose (24 h) to YNB medium without amino acids and 0.1% yeast extract (YE) (48 h). Under condition B, cultures were passaged from YNB medium without amino acids and 1% glucose to YNB medium without amino acids, 2% methanol and 0.1% yeast extract (MeOH + YE) (48 h). Figure was created with BioRender.com. b Schematic of the mutations in YGR067C from the three evolved lineages grown under condition B, and the changes they caused to the protein, all three mutations theoretically led to truncations. c Growth profiles of CEN.PK 113-5D (black squares), the three evolved lineages (A, dark blue upright triangles. B, light blue inverted triangles. C, purple diamonds.) in condition B, and the reconstructed CEN.PK 113-5D strain with the mutation observed in the evolved lineage C (green circles). Strains were grown in liquid YNB medium with 0.1% yeast extract and 2% methanol. Data are from two independent biological replicates with lines representing the mean. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

ALE of native methanol assimilation in S. cerevisiae

ALE was applied to characterise and improve native methanol metabolism in S. cerevisiae. The ALE strategy consisted of three independent lineages grown in 1× YNB medium with either yeast extract or yeast extract plus 2% methanol. Yeast extract-only medium was included to track any improvements in fitness specific to yeast extract. Cultures were grown in baffled shake flasks with alternating passages on 1% glucose or yeast extract with or without methanol (Fig. 2a). ALE relies on naturally occurring DNA replication errors to generate genetic diversity within a population. Owing to the relatively poor growth of S. cerevisiae on yeast extract methanol medium, pulsing between two different media was performed in order to increase the number of generations and mutations over time, while still exposing the population to methanol alongside a poor co-substrate (yeast extract) as a selection pressure. All six independent lineages were grown for 230 generations until a biomass (OD600) increase in yeast extract methanol medium was observed. The six evolved populations were re-sequenced to identify putative mutations leading to the phenotype. Only genes with mutations in all three methanol-exposed lineages that were absent in the yeast extract only lineages were considered. The only gene that matched these criteria was YGR067C, which had point mutations at different positions in the three methanol-evolved lineages (Fig. 2b). Ygr067cp is an uncharacterised putative transcription factor with a DNA-binding domain similar to that of ADR1 (alcohol dehydrogenase II synthesis regulator). ADRI encodes a transcription factor that is involved in the expression of glucose-repressed genes, ethanol metabolism and peroxisomal proliferation27,28. All three independent mutations resulted in premature stop codons, which would result in truncation of the YGR067C protein (Fig. 2b). Mutations in the High Osmolarity Glycerol response gene HKR1 (I584L) were identified in methanol-evolved lineages A and C, but not B, whereas a mutation in the cell wall protein encoding FIT1 (V204A) gene was identified in all three yeast extract evolved lineages.

To test if truncation of the YGR067C transcription factor was responsible for improved growth on methanol, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated homologous recombination was used to introduce a stop codon in YGR067C of the wild-type strain as observed in the evolved lineage C (Fig. 2b). The mutation from evolved lineage C was chosen to reconstruct the phenotype as the truncation in Ygr067cp occurred midway between the evolved lineages A and B (Fig. 2b). This reconstructed CEN.PK 113-5D strain was referred to as reconstructed EC. The three evolved lineages, the parental CEN.PK 113-5D, and reconstructed EC strains were grown on yeast extract methanol medium to analyse growth differences (Fig. 2c). The evolved lineage A strain had a final biomass increase of 37% in the presence of methanol compared with the parental CEN.PK 113-5D strain, whereas the evolved lineage B and C strains showed a 22% and 44% increase, respectively. Importantly, the reconstructed EC strain has the same growth profile and final biomass increase (44%) as the evolved lineage C strain compared with the parental strain, indicating that the truncated transcription factor is responsible for increased growth in the presence of methanol. No growth improvement was observed between the parental and reconstructed EC strain on yeast extract only medium or minimal medium with glucose.

Reconstructed EC strain characterisation and 13C-methanol tracer analysis

To characterise the effect that the reconstructed EC strain had on native methanol metabolism in S. cerevisiae, CEN.PK 113-5D and the reconstructed EC strain were grown in bioreactors with 2% 13C-methanol and 0.1% yeast extract. The reconstructed EC strain was chosen for 13C-methanol tracer analysis as it provides a clearer genotype–phenotype relationship as the only genotypic change between this strain and the parental CEN.PK 113-5D is the introduced truncation of Ygr067cp. Thus, any observed changes could most likely be attributed to the regulatory function of YGR067C. As previously noted (Fig. 2c), a growth advantage was observed in the reconstructed EC strain (Fig. 3a), which reached a higher final biomass compared with CEN.PK 113-5D. Both strains produced 80% of total CO2 as 13C-CO2 (Fig. 3b). However, the reconstructed EC strain produced less 13C-ethanol, particularly at 11 h (Fig. 3c, d). We hypothesised that the reconstructed EC strain could be redirecting methanol into biomass constituents and thus reducing ethanol production. 13C-methanol tracer analysis revealed that the reconstructed EC strain had a higher percentage of fully 13C-labelled intracellular metabolites compared with CEN.PK 113-5D (Fig. 3e). An approximate threefold increase in 13C-labelled glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate was observed as well as increased 13C-labelling of metabolites involved in lower glycolysis, including 3-phosphoglyceric acid, phosphoenolpyruvate, and pyruvate. 13C-labelled pyruvate increased from 2.7% in CEN.PK 113-5D to 15.4% in the reconstructed EC strain. Higher 13C-labelling was also observed for metabolites in the pentose phosphate pathway but the proportion of 13C-labelled metabolites was still low in both strains (<5%). An interesting observation was that CEN.PK 113-5D had a higher proportion of 13C-labelled acetyl-CoA compared with the reconstructed EC strain, 67.6% compared with 46.6% (Fig. 3e). Finally, no un-labelled or 13C-labelled ketoglutarate, fumarate, malate, oxaloacetate or glyoxylate were detected in the TCA cycle. The only metabolites that were detected in the TCA cycle were citrate and succinate, 13C-labelled citrate increased from 2.4% to 11.4% in the reconstructed EC strain while the same levels (0.5%) were observed in both strains for 13C-labelled succinate.

a Growth profile of CEN.PK 113-5D and the reconstructed evolved strain grown in liquid YNB medium with 2% 13C-methanol supplemented with 0.1% yeast extract cultures in bioreactors. Data are from two independent biological replicates with lines representing the mean. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. b Percentage of 13C-CO2/CO2 production in yeast extract 13C-methanol (2%) medium from two biological replicates with bars representing the mean. c 13C-ethanol was produced by CEN.PK 113-5D and by the reconstructed evolved strain. The signal intensity was normalised to the inert gas nitrogen, and then to biomass for each strain. Data show 13C-ethanol intensity at 47 amu for two independent biological replicates, with bars representing the mean. d Comparison of 12C-ethanol and 13C-ethanol intensities during growth in 13C-methanol. The signal intensity was normalised to the inert gas nitrogen, and then to biomass for each strain. Data show the 12C-ethanol and 13C-ethanol intensity at 31 and 33 amu, respectively, for two independent biological replicates, with bars representing means. SEM secondary electron multiplier, amu atomic mass unit. e Percentage of fully 13C-labelled intracellular metabolite pool relative to total metabolite pool of CEN.PK 113-5D and reconstructed evolved strains. F1,6BP fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, G3P glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, RL5P ribulose-5-phosphate, DHAP dihydroxyacetone phosphate, CIT citrate, 3PG 3-phosphoglyceric acid, PEP phosphoenolpyruvate, ACCoA acetyl-coenzyme A. Data are from two independent biological replicates, with bars representing means, except for CEN.PK 113-5D F1,6BP, for which no 12 C metabolite was detected in one replicate. Purple squares represent the Reconstructed EC strain, and black circles represent the CEN.PK 113-5D strain. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further characterise the changes in the reconstructed EC strain, global transcript and protein levels were compared with the parental strain (Fig. 4). During growth on 2% 13C-methanol and 0.1% yeast extract, 243 transcripts were found to be significantly differentially expressed in the reconstructed EC strain (adjusted p < 0.01) with 111 genes downregulated and 132 genes upregulated (Supplementary File 1). Gene-list analysis of the downregulated genes showed Gene Ontology (GO) pathway enrichment of the TCA cycle, respiration and the glyoxylate cycle. No pathway enrichment was found for the upregulated genes in the reconstructed EC strain but GO process enrichment was found for ‘carbohydrate transmembrane transport’, ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’, ‘glycolytic process’ and ‘pyruvate metabolic process’, among others. Proteomics analysis showed 103 proteins were significantly altered in abundance in the reconstructed EC strain relative to the parent (adjusted p < 0.05; Supplementary File 2) with 84 proteins increased and 19 proteins decreased. Gene-list analysis of proteins with increased expression showed pathway enrichment of the ‘superpathway of glucose fermentation’, whereas the proteins with decreased abundance showed GO process enrichment only for ‘trehalose metabolic process’.

Percentage of 13C-labelled intracellular metabolites in CEN.PK 113-5D (black) and the reconstructed evolved strain (purple). Metabolites are fully labelled with 13C. Data points represent the average of two independent biological replicates with standard deviation. Transcript and protein abundance in the reconstructed evolved strain compared with the parental strain. Genes with up- or downregulated fold-changes and adjusted p values <0.01 are coloured blue or yellow, respectively. Increased or decreased protein abundance and adjusted p values <0.05 is shown in blue or yellow arrows, respectively. ND not detected. The metabolic map was redrawn based on ref. 58. Metabolite abbreviations: MeOH methanol, FORM formaldehyde, DHA dihydroxyacetone, DHAP dihydroxyacetone phosphate, Xu5P xylulose-5-phosphate, G6P glucose-6-phosphate, F6P fructose-6-phosphate, F,6BP fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, GAP glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, 1,3BPG 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate, 3PG 3-phosphoglycerate, 2PG 2-phosphoglycerate, PEP phospheonolpyruvate, OA oxaloacetate, CIT citrate, SUCCCoA succinyl-coenzyme A, ACCoA acetyl-coenzyme A, ICI isocitrate, AKG alpha-ketoglutarate, SUCC succinate, FUM fumarate, MAL malate, GLYOX glyoxylate, ACAL acetaldehyde, 6PGL 6-phospho-d-glucono-1,5-lactone, 6PGC 6-Phospho-d-gluconate, Ru5P ribulose-5-phosphate, R5P ribose-5-phosphate, S7P sedoheptulose-7-phosphate, E4P erythrose-4-phosphate. Enzyme abbreviations: alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh1, Ahd2, Ahd3, Adh4, Adh5, SFA1), formate dehydrogenase (Fdh1), aldehyde dehydrogenase (Ald6), pyruvate decarboxylase (Pdc1, Pdc5, Pdc6), dihydroxyacetone kinase (Dak1, Dak2), triose phosphate isomerase (Tpi1), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Tdh1, Tdh2, Tdh3), fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (Fba1), phosphoglucose isomerase (Pgi1), hexokinase (Hxk1, Hxk2, Glk1), phosphofructokinase (Pfk1, Pfk2), transketolase (Tkl1, Tkl2), 3-phosphoglycerate kinase (Pgk1), phosphoglycerate mutase (Gpm1), enolase (Eno1, Eno2), pyruvate kinase (Pyk1, Pyk2), pyruvate dehydrogenase (Pda1), citrate synthase (Cit1, Cit2), aconitase (Aco1, Aco2), isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh1, Idh2, Idp1), alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (Kgd1, Kgd2), succinyl-CoA ligase (Lsc1, Lsc2), fumarate reductase (Osm1, Frd1), succinate dehydrogenase (Sdh1, Sdh2, Sdh3, Sdh4), fumarase (Fum1), malate dehydrogenase (Mdh1), malic enzyme (Mae1), transaldolase (Tal1, Nqm1), formaldehyde dehydrogenase (Sfa1), d-ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase (Rpe1), Ribose-5-phosphate ketol-isomerase (Rki1). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Both transcriptomics and proteomics indicated there were significant changes in central carbon metabolic pathway expression between the evolved reconstructed and parental strain. Five genes involved in glycolysis had higher transcript abundance in the reconstructed EC strain compared with CEN.PK 113-5D (HXK1, GLK1, DAK2, TDH1 and ENO2), whereas FBP1, coding for fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, a key enzyme involved in gluconeogenesis29,30, had lower transcript abundance. Hxk1p, Glk1p, Tdh1p and Eno2p also had increased protein abundance, as well as Pfk1p, suggesting glycolysis rather than gluconeogenesis is predominantly occurring during growth on methanol in the reconstructed EC strain. The increased transcript abundance of the 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase glycolysis regulator PFK2731 in the reconstructed EC strain also supports this concept. Concordant with the metabolite profile of the reconstructed EC strain, lower transcript abundance was observed for nine genes involved in the TCA cycle (CIT1, CIT2, ACO1, IDH1, IDH2, KGD2, SDH1, SDH3 and FUM3; Fig. 4), suggesting the TCA cycle is downregulated during growth on methanol and yeast extract. Sfa1p, which is involved in native formaldehyde detoxification and alcohol oxidation also had increased protein abundance in the reconstructed EC strain. Finally, the pentose phosphate pathway showed interesting results, with RKI1 having lower transcript abundance and Tkl2p lower protein abundance, whereas Tal1p and Fba1p had higher protein abundance.

ADH2 and ACS1 deletion reduces methanol-specific growth

Four genes were selected to analyse their potential role in native methanol metabolism in the reconstructed EC strain. First, the gene coding for an alcohol dehydrogenase 2 (ADH2) was selected as in a separate study it was significantly upregulated in response to methanol25 and owing to the promiscuity of alcohol dehydrogenases in S. cerevisiae, it could be oxidising methanol to formaldehyde. CAT8, coding for a transcription factor involved in de-repressing genes during growth on non-fermentable carbon sources and thought to regulate the mutated transcription factor Ygr067cp32 (Fig. 2b) was chosen to analyse its effect on methanol growth. The serine hydroxymethyltransferase gene (SHM1) was chosen for deletion as another possibility for C1 carbon assimilation in S. cerevisiae involves formaldehyde detoxification to formate and then assimilation through the glycine cleavage complex33. Shm1p is responsible for converting serine to glycine and 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate and would be required if biomass formation was due to formaldehyde detoxification and subsequent formate assimilation. Finally, ACS1 coding for an Acetyl-CoA synthetase was selected as a study by Oshawa et al.34 analysed the role of ACS1 in P. pastoris and found that it is involved in ethanol repression, which is needed for the expression of methanol-induced genes.

Single deletion strains of the aforementioned genes were constructed in the reconstructed EC strain and tested by spotting the strains onto solid minimal YNB medium with 2% glucose, no additional carbon source, or increasing methanol concentrations (Fig. 5). The reconstructed EC strain Δadh2 grew similarly to the reconstructed EC strain in minimal medium with 2% glucose or no additional carbon source (1× YNB) but growth was dramatically reduced on media containing methanol (1–3%), suggesting it is needed for methanol oxidation to formaldehyde. When Δcat8 was deleted from the reconstructed EC strain, growth was only observed with 2% glucose as the carbon source, and its deletion dramatically decreased growth on methanol and 1× YNB, as previously reported35. Any potential role of CAT8 in methanol assimilation could therefore not be analysed using this method. Deletion of SHM1 had no effect on growth compared with the reconstructed EC strain on media with either glucose or methanol, suggesting it is not involved in the native methanol assimilation pathway. Interestingly, ACS1 deletion showed no growth effect with 1% methanol, but had almost no growth when methanol was present at higher concentrations (2 and 3%).

Growth on solid 1×YNB medium with different carbon sources was tested using serial ten-fold dilutions of the reconstructed evolved strain with an empty vector or ACS1, ADH2, SHM1 or CAT8 deletions. Yeast nitrogen base (YNB), yeast extract (YE), methanol (MeOH). Images were taken after incubating at 30 °C for 6 days. Images are representative of two repeated experiments.

Discussion

Methanol is emerging as an important C1 feedstock for industrial biotechnology, making the characterisation and improvement of native methanol metabolism in model organisms critical to utilising this feedstock. Here, we analysed native methanol utilisation in S. cerevisiae CEN.PK 113-5D. First, a methanol-specific growth increase was seen in medium containing low amounts of yeast extract as a co-substrate (Fig. 1a). 13C-methanol trace analysis was then used to analyse the methanol metabolism of CEN.PK 113-5D. 13C-ethanol and 13C-labelled intracellular metabolites were produced (Fig. 1b, c), demonstrating methanol was not only being utilised by CEN.PK but also assimilated through central carbon metabolism. Importantly, S. cerevisiae has never been classified as a methylotroph, and no previous growth on- or assimilation of- methanol has been recorded in the literature. The identification of fully 13C-labelled metabolites from 13C-methanol clearly showed that methanol can be assimilated through central carbon metabolism in S. cerevisiae.

After identifying native methanol assimilation, we sought to characterise and optimise this pathway using ALE (Fig. 2a). Laboratory evolution experiments have been successful in optimising consumption of C1 carbon sources such as methanol and CO2 in E. coli, and CO2 in P. pastoris14,36,37. ALE strategies are also helpful for elucidating non-obvious biological engineering solutions and understanding partially characterised systems. In this study, final biomass was increased in liquid yeast extract methanol medium by 44% (Fig. 2a) after 230 generations. Whole-genome sequencing revealed mutations in an uncharacterised putative transcription factor YGR067C that led to truncations of the protein (Fig. 2b). Ygr067cp truncation was reverse engineered into the parental CEN.PK 113-5D strain, and the phenotype was restored (Fig. 2c), confirming that mutations in YGR067C are responsible for the improved growth on methanol. Ygr067cp shares an identical DNA-binding domain with Adr1p and is regulated by Cat8p28,32. Both Adr1p and Cat8p are involved in de-repression of genes needed for growth on non-fermentable carbon sources such as ethanol or glycerol32. Adr1p also activates genes involved in peroxisomal biogenesis and proliferation28. Genes under the control of Adr1p that are relevant to methanol metabolism include formate dehydrogenases (FDH1/FDH2), ADH2, catalase (CTA1) and PEX11, a peroxisomal membrane protein28. The truncation of Ygr067cp could have caused the constant expression of genes that are normally repressed, leading to more favourable regulatory conditions and metabolic fluxes for growth on methanol.

To characterise the improved growth on methanol, the reconstructed EC strain was grown on 13C-methanol and compared with the parental strain CEN.PK 113-5D (Fig. 3). The reconstructed EC strain had an improved capacity for methanol assimilation, with higher proportions of 13C-labelled intracellular metabolites observed (Fig. 3e). Moreover, integrated metabolomics, transcriptomics and proteomics analyses showed that the reconstructed EC strain has a different metabolic profile compared to the parent, with the TCA cycle and gluconeogenesis enzymes being downregulated (Fig. 4). Together with the upregulated genes (DAK2, TDH1 and ENO2) and higher protein abundance of Pfk1p, Fba1p, Tdh1p and Eno2p, it is likely that a net glycolytic flux increase occurs during methanol assimilation in the reconstructed EC strain relative to the parental control strain.

The downregulated transcripts and proteins that we observed in the TCA and glyoxylate cycles fully overlap with those that are normally de-repressed during growth on non-fermentable carbon sources in a CAT8- and SNF1-dependent manner28,32. Given that CAT8 is known to regulate YGR067C32, it is likely that truncation of the YGR067C protein facilitates a decoupling of methanol assimilation from the traditional non-fermentable carbon source utilisation phenotype in yeast. At present, it is unclear how these metabolic rearrangements favour methylotrophy in S. cerevisiae. One possibility is that glycolytic rather than gluconeogenic fluxes favour the pentose phosphate pathway fluxes necessary for methanol assimilation in the presence of yeast extract. Another point worth noting is that many obligate methylotrophs operate an incomplete, downregulated TCA cycle through the absence of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase activity, which is thought to preclude heterotrophic growth38.

It is unclear how formaldehyde, the oxidation product of methanol, is assimilated in S. cerevisiae. However, the high levels of 13C-labelling we saw in dihydroxyacetone phosphate, fructose-1-6-bisphosphate, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate suggest assimilation occurs via a mechanism similar to the P. pastoris XuMP pathway where formaldehyde and xylulose-5-phosphate are converted into dihydroxyacetone and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate. Based on the higher transcript abundance of Tal1p and Fba1p, it is possible that the non-oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway is going through different rearrangement reactions than those when S. cerevisiae is grown on glucose to recycle the co-substrates needed for formaldehyde assimilation. Transaldolase could be catalysing the rearrangements of fructose-6-phosphate and sedoheptulose-7-phosphate to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and erythrose-4-phosphate as it was recently postulated in P. pastoris grown on methanol39,40. To identify specific genes involved in native methanol assimilation, ADH2 and three other genes were deleted from the reconstructed EC strain. Another study from our group found that ADH2 was upregulated when S. cerevisiae was grown in the presence of methanol25 and when the reconstructed EC strain with an ADH2 deletion was grown on solid minimal media with increasing concentrations of methanol, growth was severely hindered in all cases, suggesting its role in oxidising methanol to formaldehyde (Fig. 5). We also observed that deletion of acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACS1) reduced growth on solid methanol media (Fig. 5). Acs1p is important for growth on non-fermentable carbon sources41, and its homologue is an important regulator of methylotrophic metabolism in P. pastoris34,42. Acs1p is therefore likely to be an important source of acetyl-CoA in S. cerevisiae methanol metabolism.

Native methanol assimilation was identified in S. cerevisiae and improved through ALE, providing the possibility of exploring native methanol metabolism. Higher biomass formation, a complete understanding of native methylotrophic metabolism, and the elimination of the requirement for yeast extract in liquid methanol medium are the most immediate challenges remaining for the implementation of growth with methanol as the sole carbon source in S. cerevisiae. After robust methylotrophy is established in S. cerevisiae, existing metabolite production pathways could potentially be coupled to a methanol converting ‘platform strain’ using the state-of-the-art genetic tools and the deep physiological characterisation available in this model organism. Together, the results from this work represent an exciting step towards using sustainable feedstocks during microbial fermentations for conversion to chemicals, fuels, materials, pharmaceuticals and foods, and provide a glimpse of an unexplored metabolic network in a model eukaryote.

Methods

Strains and plasmids

S. cerevisiae plasmids and strains used in this study are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. All strains are available from the authors upon request. To delete ADH2, CAT8, SHM1 and ACS1 from the reconstructed EC strain, the orf::KanMX locus from the BY4741 knockout collection43 plus 500 bp up- and downstream was PCR amplified using primers 1–8. Amplified constructs were then transformed into the reconstructed EC strain and plated on yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) with Geneticin (200 μg/mL; Gibco™ 10131035). Independent colonies were screened via PCR using primers 9–16 that annealed 200 bp outside of the PCR-generated homology region. All primers and their sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Media and growth conditions

E. coli DH5α cells were used for plasmid propagation/storage and grown in lysogeny broth media (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl) with ampicillin.

The strains were precultured on yeast nitrogen base (YNB) medium without amino acids and with 5 g/L ammonium sulphate (Sigma-Aldrich Y0626) and 10 g/L glucose. Growth experiments were performed on YNB medium with 1 or 2% methanol supplemented with 1 g/L yeast extract (Merck 103753). Optical density readings at 600 nm (OD600) were used to track growth. For spot assays, swabs from streaked agar plates were precultured twice in 10 mL of 1× YNB, 1% glucose in sterile 50 mL Falcon tubes. During the exponential phase of the final pre-culture, cells were washed twice in 10 mL of sterile MilliQ water and serially diluted 10-fold up to 10−4, prior to spotting 5 μl from each dilution onto the indicated agar plates. Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 6 days. Spot assay photos are representative of repeated experiments. For the ALE experiment, three independent lineages of CEN.PK 113-5D with pRS416 where grown on baffled shake flasks with 50 mL YNB medium containing 1 g/L yeast extract or 1 g/L yeast extract with 2% methanol (48 h) pulsing with YNB medium with 1% glucose (24 h), and incubated at 30 °C. OD600 measurements were taken before every passage and the cultures were inoculated at a starting OD600 of 0.2 if grown on conditional medium or OD600 of 0.02 if grown on glucose medium.

DNA extraction and whole-genome sequencing of ALE lineages

Glycerol stocks of the six independent evolutionary lineages were inoculated into 10 mL of YPD medium and grown overnight. Cells were pelleted and washed twice in 10 mL sterile MilliQ water by centrifuging at 4000 × g for 2 mins. Genomic DNA was extracted from pellets using the Yeast DNA Extraction Kit from ThermoFisher (catalogue number 78870) according to the instructions. Whole-genome sequencing was performed at the Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics using Nextera XT library preparation and NextSeq500 2 × 150 bp sequencing. A minimum of 11 million reads were generated per sample with >95% of reads having Q20 quality scores, except for methanol-evolved lineage B, which had 80% of reads with at least Q20. An annotated CEN.PK 113-7D reference genome was generated by transferring annotated coding sequences with greater than 95% homology from the S288C reference genome to CEN.PK 113-7D FASTA files using Geneious Pro version 1144. Untrimmed reads were mapped to the annotated CEN.PK 113-7D reference genome using Geneious Pro. Each sample had >99% of reads mapped to the reference with ~100-fold coverage. Non-synonymous single nucleotide variants (SNV) within coding sequences were identified at a minimum coverage of 10×, read-variant frequency of 0.9, maximum variant p value of 10−5, and a minimum strand-bias p value of 10−5 when exceeding 65% bias. SNVs from each evolved lineage were annotated onto the same CEN.PK reference sequence and inspected visually using Geneious Pro. SNVs present in the three methanol-exposed lineages but absent in the three yeast extract only lineages were identified as potentially causative mutations. Mutations present in all six lineages were assumed to be present in the parental CEN.PK 113-5D strain, and were not considered any further. Raw genome sequencing reads have been deposited at the National Centre for Biotechnology Information under Bioproject number PRJNA612896.

Reconstruction of evolved lineage C mutation in YGR067C

The methanol-exposed evolutionary lineages had convergent but non-identical mutations in YGR067C, which all encoded truncations in the protein through premature stop codons. These mutations were substitution of C to G at nucleotide position 788, deletion of A at position 1877 and substitution of C at position 1176 to G. The C1176G mutation from lineage C was chosen for reverse engineering into the parental CEN.PK 113-5D strain owing to the proximity of the mutation to a favourable CRISPR-Cas9 PAM site. The mutation was constructed using a single pRS423 plasmid encoding the Cas9 protein, the guide RNA and a hygromycin selection marker, which is PCR amplified using primers that encode a new guide sequence in their 5’ extensions (primers 17 and 18) and have 20 nt of homology to one another45,46,47. This PCR product was co-transformed with mutated YGR067C DNA that was PCR amplified from evolved lineage C genomic DNA using primers 19 and 20, with transformants selected for hygromycin resistance on YPD agar plates. Crude genomic DNA was extracted using the lithium acetate-sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) method where colonies are heated for 5 min at 70 °C in 100 µL of 200 mM lithium acetate, 1% SDS prior to DNA precipitation using 100% ethanol, pelleting at 20,000 × g and resuspension in 100 µL of sterile water48. Transformants were screened by PCR amplifying and Sanger sequencing the putatively mutated region of YGR067C using primers 21 and 22, which anneal outside the YGR067C locus. One out of 12 tested colonies had the desired mutation using this method. This strain was subsequently referred to as ‘reconstructed EC’. All primers and their sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

ambr® 250 bioreactor fermentations

CEN.PK 113-5D was precultured as above in sterile 50 mL Falcon tubes prior to inoculation at an OD600 of 0.02 in ambr® 250 (Sartorius Stedim) microbial bioreactors with 140 mL of medium. Dissolved oxygen was maintained at a minimum level of 20% via automatic control of stirring speed, air sparging and O2 sparging. pH was maintained at five via the automatic addition of 5 M potassium hydroxide or 1 M phosphoric acid, and temperature was kept at 30 °C. Bioreactors were sampled robotically at indicated time points, with 1 mL samples stored at −20 °C prior to measurement of growth using OD600.

13C-methanol fermentations

Growth experiments in YNB medium supplemented with yeast extract (1 g/L) and 13C-methanol (2%; Sigma-Aldrich 277177) were carried out aerobically (sparging air) at 30 °C, agitation of 300 RPM, and with a starting volume of 250 mL of medium using the Multifors 2 bioreactor system (Infors AG). pH was maintained between 4.8 and 5.2 using 3 M H3PO4. For pre-culturing, biological replicates of each strain were grown in liquid YNB medium for ~15 h. Cultures were then passaged into a second pre-culture and grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600nm between 1 and 3). A third pre-culture was also grown to mid-exponential phase and washed twice with sterile water before inoculating the experimental cultures at an OD600 of 0.02.

RNA extraction, sequencing and transcriptome analysis

RNA samples were taken at 34 h during the 13C-methanol (2%) fermentations. In all, 30 mL of culture was centrifuged at 4 °C 17,000 × g for 10 min, with pellets resuspended in RNA later (Sigma-Aldrich R0901) and stored at −20 °C prior to RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted by digesting cell pellets in five units of zymolyase in the digestion buffer of the YeaStar RNA extraction kit (Zymo Research catalogue number R1002) for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by column purification using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN catalogue number 74136). Library preparation and sequencing was performed at the Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics using a TruSeq Stranded mRNA-seq preparation kit and NextSeq 500 2×75 bp sequencing. Thirty million reads were generated per sample with Q30 > 93% and Q20 > 95%. Untrimmed reads were mapped to the S288C genome with read counting and differential expression analysis carried out using Geneious Pro version 1144 by mapping reads to the S288C reference genome using the Geneious RNA algorithm with default settings. RPKM, FPKM and TPM read counts were calculated prior to differential expression analysis using the DeSeq249 within Geneious, and a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.1. Approximately 72 million reads were generated per sample. Genes with adjusted p values <0.01 were considered differentially expressed. Lists of up and downregulated genes were analysed for GO term and pathway enrichment using YeastMine at the Saccharomyces Genome Database (https://yeastmine.yeastgenome.org/yeastmine/bag.do). Significant enrichment against the background whole-genome gene list was identified with p-values less than 0.05 and Holm–Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. A list of all significant genes that were differentially expressed can be found in Supplementary File 1.

Off-gas data analysis

Real-time analysis of bioreactor culture off-gas was achieved using a Hiden HPR-20-QIC mass spectrometer (Hiden Analytical) that was connected to the bioreactors. The Faraday Cup detector was used to monitor the signal intensities of N2, Ar, CO2, 13C-CO2, ethanol, 13C-ethanol and 13C-methanol at 28, 40, 44, 45, 27, 47 and 30 atomic mass unit (amu), respectively. To increase sensitivity and detect the presence of 13C-ethanol from the off-gas data, the Secondary Electron Multiplier (SEM) detector was used to scan any intensities from 15 to 50 amu, with 47 and 48 amu corresponding to 13C-ethanol. N2 intensity (constant during fermentation as nitrogen was an inert gas in our experiments) at 28 amu was used to normalise the intensity from 13C-ethanol. The SEM detector scanned the intensities during two to six independent cycles for each bioreactor and at two different time points.

Metabolomics

To measure intracellular metabolites, samples were taken at 11 h during the 13C-methanol (2%) fermentations, quenched in methanol and frozen at −80 °C. For extraction, the pellet was resuspended in 2 mL of 50% acetonitrile and transferred to 2 mL microcentrifuge tubes with 0.1 mm diameter glass beads, every sample had two technical replicates. Samples were vortexed for 30 s using a Precellys 24 tissue homogeniser (Bertin Instruments) at 30 °C. Three rounds of vortexing were performed allowing the samples to cool completely between rounds. Samples were centrifuged for 3 min at 5000 × g and the supernatant was transferred to a clean microcentrifuge tube and stored overnight at −80 °C. In all, 2 mL of samples were freeze-dried overnight, then resuspended in 100 μL of water with 10 µM of AZT as internal standard, then transferred to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) glass inserts for analysis.

Metabolites were analysed using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry as adapted from ref. 50,51,52. In brief, analyses were performed using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC system coupled to an AB Sciex 4000 QTRAP mass spectrometer. Liquid chromatography was performed using a 50 min gradient, detailed in Supplementary Table 1, with 300 μL/min flowrate, on a Phenomenex Gemini-NX C18 column (150 ×2 mm, 3 μm, 110 A), with a guard column (SecurityGuard Gemini-NX C18, 4 ×2 mm), and column temperature of 55 °C. The mobile phases used were: 7.5 mM aqueous tributylamine (Sigma-Aldrich) with pH adjusted to 4.95 (±0.05) using acetic acid (Labscan) for Solvent A, and acetonitrile (Merck) for Solvent B. Samples were kept at 4 °C in the autosampler and 10 μL were injected for analyses. The HPLC was controlled by Chromeleon 6.80 software (ThermoFisher). Mass spectrometry was achieved using a scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (sMRM) method on the negative ionisation mode. Details of the compound-specific parameters used in the sMRM analysis are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Other hardware parameter values include: ion spray voltage −4500 V, ion source nebuliser (GS1), ion source auxiliary (GS2), curtain (CUR) and collision (CAD) gases were 60, 60, 20 and medium (arbitrary units), respectively, using an in-house ultra-high purity liquid nitrogen tank (BOC). The auxiliary gas temperature was kept at 350 °C. The mass spectrometer was controlled by Analyst 1.6.3 software (AB Sciex). Amounts obtained for each metabolite detected were based on standard curves from serial dilutions of analytical standards, purchased from Sigma, where L1 = 200000, L2 = 100000, L3 = 50000,… L20 = 0.38 nM. This number of standard dilutions guaranteed that the standard curves consisted of at least five data points. Standard mix and pooled samples were regularly injected along the run sequence for quality control. Collected data were processed using MultiQuant 2.1 (AB Sciex).

Protein extraction and mass spectrometry-based proteomics

Protein samples were taken at 34 h during the 13C-methanol (2%) fermentations. Samples were centrifuged at 4 °C 17,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was discarded and the cell pellet was washed with 1.5 mL of Gibco™ Phosphate-buffered Saline (Life Technologies). Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (5% SDS, 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate, 100 mM DTT, pH 7.55) and transferred to a microcentrifuge tube containing 0.5 mm diameter glass beads. Cells were disrupted by using a Precellys 24 tissue homogeniser (Bertin Instruments) for eight rounds of vortexing (30 s vortex, 45 s rest) without cooling. Microcentrifuge tubes were centrifuged for 10 min at 17,000 × g and supernatant was transferred to a clean microcentrifuge tube and stored at −20 °C. Samples were digested with trypsin following the S-trap™ minis (ProtiFi, LCC.) protocol. The digested peptide mixtures were concentrated using Millipore® ZipTip C18 (Merck) eluting with 70% acetonitrile. Residual acetonitrile was removed by vacuum centrifugation and peptides resuspended in 5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid (aqueous) before analysis. Peptides were analysed using a ThermoFisher Scientific UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano UHPLC system. Each sample was initially injected onto a ThermoFisher Acclaim PepMap C18 trap reversed-phase column (300 µm × 5 mm nano viper, 5 µm particle size) at a flow rate of 20 µL/min using 2% acetonitrile (aqueous) for 5 min with the solvent going to waste. The trap column was switched in-line with the separation column (ThermoFisher EasySpray Pepmap RSLC C18, 150 µm × 150 mm, 2 µm) and the peptides were eluted using a flowrate of 1.0 µL/min using 0.1% formic acid in water (buffer A) and 80% acetonitrile in buffer A (buffer B) as mobile phases for gradient elution. Peptide elution employed a 4-30% acetonitrile gradient for 40 min followed by 30–50% acetonitrile for 10 min and 50–95% acetonitrile for 1 min at 40 °C. The total elution time was 60 min including a 95% acetonitrile wash followed by re-equilibration. For each sample run, a volume of 2 µL equating to ~1 µg of peptide material from protein digestion was injected.

The eluted peptides from the C18 column were introduced to the MS via a nano-ESI and analysed using the Q-Exactive HF-X (ThermoFisher). The electrospray voltage was 1.8 kV in positive ion mode, and the ion transfer tube temperature was 275 °C. Employing a top-40ddMS2 acquisition method, full MS-scans were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyser over the range m/z 350–1400 with a mass resolution of 120,000 (at m/z 200). The AGC target value was set at 3.00E + 06. The 40 most intense peaks with a charge state between 2 and 5 were fragmented in the high energy collision dissociation cell with a normalised collision energy of 28. MSMS spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyser with a mass resolution of 15,000 at m/z 200. The AGC target value for MSMS was set to 1.0E + 05 while the ion selection threshold was set to 1E + 03 counts. The maximum accumulation times were 60 min for full MS-scans and MSMS. For all the experiments, the dynamic exclusion time was set to 25 s, and undetermined charge state species were excluded from MSMS.

Raw files were processed using MaxQuant53 version 1.6.10.43 with the integrated Andromeda search engine54 and the following search parameters: trypsin digestion with a maximum of two missed cleavages, carbamidomethyl (C) as a fixed modification and oxidation (M) and acetyl (protein N-term) as variable modifications. The MS data were searched against the SGD protein sequence database (6630 entries downloaded November 2019). A peptide spectrum match FDR of 0.01 and a protein FDR of 0.01 were used as protein identification level cutoffs. Label-free quantification (LFQ)55 was performed using MaxQuant LFQ intensities. Protein quantification analysis of the LFQ results was performed using Perseus56 version 1.6.10.0. The data were first filtered to remove identified proteins classified as ‘reverse’, ‘only identified by site’ and ‘potential contaminants’. The two corresponding biological replicates for CEN.PK 113-5D or the reconstructed EC strain were loaded separately and classified as replicates. Proteins that were not present in at least one of the two biological replicates were removed to further trim the data set. All LFQ values were log2 transformed, the median intensity was subtracted to all intensities for all samples to normalise the distribution, and missing values were imputed to 0. Last, a two-sided t test was performed between CEN.PK 113-5D and the reconstructed EC strain, and proteins with FDR adjusted p values of <0.05 were designated as differentially expressed. The log2FC for the significant proteins was then calculated. A list of all significant proteins that were differentially expressed can be found in Supplementary File 2.

Statistics and reproducibility

The plotted data are from independent cultures and the spot assays in Fig. 5 were repeated twice with similar results.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are included with the published article (and its supplementary information and Source Data files). Raw proteomics data can be downloaded using the following link https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/6n9kdrbcvv/draft?a=6ada27c1-2db7-46e9-83b4-fc34e809cfab. Raw RNA-seq and genome sequencing reads have been deposited at the National Centre for Biotechnology Information under Bioproject number PRJNA612896. Lists of up and downregulated genes were analysed for GO term and pathway enrichment using YeastMine (https://yeastmine.yeastgenome.org/yeastmine/begin.do) at the Saccharomyces Genome Database (https://yeastmine.yeastgenome.org/yeastmine/bag.do). The SGD Protein Sequence database (http://sgd-archive.yeastgenome.org/sequence/S288C_reference/orf_protein/) was used to assign proteomic mass spectra to yeast proteins. Prism 7 software was used to plot data. Any other relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Scarlat, N., Dallemand, J.-F., Monforti-Ferrario, F. & Nita, V. The role of biomass and bioenergy in a future bioeconomy: policies and facts. Environ. Dev. 15, 3–34 (2015).

Tsao, G. T. Annual reports on fermentation processes. (Elsevier Science, 2014).

Cotton, C. A. R., Claassens, N. J., Benito-Vaquerizo, S. & Bar-Even, A. Renewable methanol and formate as microbial feedstocks. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 62, 168–180 (2020).

Whitaker, W. B., Sandoval, N. R., Bennett, R. K., Fast, A. G. & Papoutsakis, E. T. Synthetic methylotrophy: engineering the production of biofuels and chemicals based on the biology of aerobic methanol utilization. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 33, 165–175 (2015).

Bennett, R. K., Steinberg, L. M., Chen, W. & Papoutsakis, E. T. Engineering the bioconversion of methane and methanol to fuels and chemicals in native and synthetic methylotrophs. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 50, 81–93 (2018).

Goeppert, A., Czaun, M., Jones, J.-P., Surya Prakash, G. K. & Olah, G. A. Recycling of carbon dioxide to methanol and derived products closing the loop. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 7995–8048 (2014).

Heux, S., Brautaset, T., A. Vorholt, J., Wendisch, V. F. & Charles Portais, J. In Methane Biocatalysis: Paving the Way to Sustainability Ch. Synthetic Methylotrophy: Past, Present, and Future 133–151 (2018).

Yang, Y.-M. et al. Production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid in engineered Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and its reassimilation through a reductive route. Microb. Cell Factories 16, 179 (2017).

Kurtzman, C. P. Biotechnological strains of Komagataella (Pichia) pastoris are Komagataella phaffii as determined from multigene sequence analysis. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 36, 1435 (2009).

Gellissen, G. Heterologous protein production in methylotrophic yeasts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 54, 741–750 (2000).

Araya-Garay, J. M. et al. Construction of a novel Pichia pastoris strain for production of xanthophylls. AMB Express 2, 24–24 (2012).

Siripong, W. et al. Metabolic engineering of Pichia pastoris for production of isobutanol and isobutyl acetate. Biotechnol. Biofuels 11, 1 (2018).

He, H., Edlich-Muth, C., Lindner, S. N. & Bar-Even, A. Ribulose monophosphate shunt provides nearly all biomass and energy required for growth of E. coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 7, 1601–1611 (2018).

Meyer, F. et al. Methanol-essential growth of Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun. 9, 1508 (2018).

Müller, J. E. N. et al. Engineering Escherichia coli for methanol conversion. Metab. Eng. 28, 190–201 (2015).

Tuyishime, P. et al. Engineering Corynebacterium glutamicum for methanol-dependent growth and glutamate production. Metab. Eng. 49, 220–231 (2018).

Whitaker, W. B. et al. Engineering the biological conversion of methanol to specialty chemicals in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 39, 49–59 (2017).

Witthoff, S., Mühlroth, A., Marienhagen, J. & Bott, M. C(1) metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum: an endogenous pathway for oxidation of methanol to carbon dioxide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 6974–6983 (2013).

Witthoff, S. et al. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for methanol metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 2215 (2015).

Woolston, B. M., King, J. R., Reiter, M., Van Hove, B. & Stephanopoulos, G. Improving formaldehyde consumption drives methanol assimilation in engineered E. coli. Nat. Commun. 9, 2387 (2018).

Chen, F. Y.-H., Jung, H.-W., Tsuei, C.-Y. & Liao, J. C. Converting Escherichia coli to a Synthetic Methylotroph Growing Solely on Methanol. Cell 182, 933–946.e14 (2020).

Brandāo, R. L. et al. Investigating acid stress response in different Saccharomyces strains. J. Mycol. 2014, 9 (2014).

DeLoache, W. C., Russ, Z. N. & Dueber, J. E. Towards repurposing the yeast peroxisome for compartmentalizing heterologous metabolic pathways. Nat. Commun. 7, 11152 (2016).

Ostergaard, S., Olsson, L. & Nielsen, J. Metabolic Engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 34–50 (2000).

Espinosa, M. I., Williams, T. C., Pretorius, I. S. & Paulsen, I. T. Benchmarking two Saccharomyces cerevisiae laboratory strains for growth and transcriptional response to methanol. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 4, 180–188 (2019).

Gonzalez, J. E., Bennett, R. K., Papoutsakis, E. T. & Antoniewicz, M. R. Methanol assimilation in Escherichia coli is improved by co-utilization of threonine and deletion of leucine-responsive regulatory protein. Metab. Eng. 45, 67–74 (2018).

Böhm, S., Frishman, D. & Mewes, H. W. Variations of the C2H2 zinc finger motif in the yeast genome and classification of yeast zinc finger proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 2464–2469 (1997).

Young, E. T., Dombek, K. M., Tachibana, C. & Ideker, T. Multiple pathways are co-regulated by the protein kinase Snf1 and the transcription factors Adr1 and Cat8. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26146–26158 (2003).

Klein, C. J., Olsson, L. & Nielsen, J. Glucose control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the role of Mig1 in metabolic functions. Microbiology 144(Pt 1), 13–24 (1998).

Mercado, J. J. & Gancedo, J. M. Regulatory regions in the yeast FBP1 and PCK1 genes. FEBS Lett. 311, 110–114 (1992).

Rider Mark, H. et al. 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase: head-to-head with a bifunctional enzyme that controls glycolysis. Biochem. J. 381, 561–579 (2004).

Haurie, V. et al. The transcriptional activator Cat8p provides a major contribution to the reprogramming of carbon metabolism during the diauxic shift in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 76–85 (2001).

Gonzalez de la Cruz, J., Machens, F., Messerschmidt, K. & Bar-Even, A. Core catalysis of the reductive glycine pathway demonstrated in yeast. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 911–917 (2019).

Ohsawa, S., Nishida, S., Oku, M., Sakai, Y. & Yurimoto, H. Ethanol represses the expression of methanol-inducible genes via acetyl-CoA synthesis in the yeast Komagataella phaffii. Sci. Rep. 8, 18051 (2018).

Gasmi, N. et al. The switch from fermentation to respiration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is regulated by the Ert1 transcriptional activator/repressor. Genetics 198, 547 (2014).

Gassler, T. et al. The industrial yeast Pichia pastoris is converted from a heterotroph into an autotroph capable of growth on CO2. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0363-0 (2019).

Gleizer, S. et al. Conversion of Escherichia coli to generate all biomass carbon from CO2. Cell 179, 1255–1263.e1212 (2019).

Wood, A. P., Aurikko, J. P. & Kelly, D. P. A challenge for 21st century molecular biology and biochemistry: what are the causes of obligate autotrophy and methanotrophy? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28, 335–352 (2004).

Rußmayer, H. et al. Systems-level organization of yeast methylotrophic lifestyle. BMC Biol. 13, 80 (2015).

Stincone, A. et al. The return of metabolism: biochemistry and physiology of the pentose phosphate pathway. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 90, 927–963 (2015).

Kratzer, S. & Schüller, H.-J. Carbon source-dependent regulation of the acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase-encoding gene ACSI from saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 161, 75–79 (1995).

Sahu, U. & Rangarajan, P. N. Regulation of acetate metabolism and acetyl Co-a synthetase 1 (ACS1) expression by methanol expression regulator 1 (Mxr1p) in the methylotrophic yeast pichia pastoris. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 3648–3657 (2016).

Baker Brachmann, C. et al. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14, 115–132 (1998).

Kearse, M. et al. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649 (2012).

van Wyk, N. et al. Blending wine yeast phenotypes with the aid of CRISPR DNA editing technologies. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 324, 108615 (2020).

Williams, T. C., Xu, X., Ostrowski, M., Pretorius, I. S. & Paulsen, I. T. Positive-feedback, ratiometric biosensor expression improves high-throughput metabolite-producer screening efficiency in yeast. Synth. Biol. 2, https://doi.org/10.1093/synbio/ysw002 (2017).

Xu, X., Williams, T. C., Divne, C., Pretorius, I. S. & Paulsen, I. T. Evolutionary engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals a TRK1-dependent potassium influx mechanism for propionic acid tolerance. Biotechnol. Biofuels 12, 97 (2019).

Lõoke, M., Kristjuhan, K. & Kristjuhan, A. Extraction of genomic DNA from yeasts for PCR-based applications. BioTechniques 50, 325–328 (2011).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Dietmair, S. et al. A multi-omics analysis of recombinant protein production in Hek293 Cells. PloS ONE 7, e43394 (2012).

McDonald, T. S., Carrasco-Pozo, C., Hodson, M. P. & Borges, K. Alterations in cytosolic and mitochondrial [U-13C] glucose metabolism in a chronic epilepsy mouse model. eneuro 4, ENEURO.0341–0316.2017 (2017).

Medina-Torres, C. E., van Eps, A. W., Nielsen, L. K. & Hodson, M. P. A liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry-based investigation of the lamellar interstitial metabolome in healthy horses and during experimental laminitis induction. Vet. J. 206, 161–169 (2015).

Cox, J. & Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 (2008).

Cox, J. et al. Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J. Proteome Res. 10, 1794–1805 (2011).

Cox, J. et al. Accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. Mol. Cell Proteom. 13, 2513–2526 (2014).

Tyanova, S. et al. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 13, 731–740 (2016).

Sikorski, R. S. & Hieter, P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122, 19–27 (1989).

Williams, T. C., Peng, B., Vickers, C. E. & Nielsen, L. K. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae pheromone-response is a metabolically active stationary phase for bio-production. Metab. Eng. Commun. 3, 142–152 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded through the CSIRO Synthetic Biology Future Science Platform, and an internal grant from Macquarie University. The Macquarie University synthetic biology laboratory and The Australian Genome Foundry are funded by Bioplatforms Australia, the New South Wales (NSW) Chief Scientist and Engineer, and the NSW Government’s Department of Primary Industries. There was no funding support from the European Union for the experimental part of the study. However, K.V. also acknowledges support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement N810755. M.I.E. thanks Dr Bradley W. Wright from Macquarie University for his guidance with proteomics analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.I.E. and T.C.W. conceived the study and designed the experiments. M.I.E. performed the experiments, with contributions from T.C.W. M.I.E. and T.C.W. analysed data. M.I.E., E.M., K.V., and R.A.G.G. designed and performed the 13C-labelling and bioreactor experiments. M.P. designed the method to detect intracellular 13C-labelled metabolites. C.S., T.C.W., I.S.P. and I.T.P. participated in the design, support, and coordination of the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Marina Kalyuzhnaya and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Espinosa, M.I., Gonzalez-Garcia, R.A., Valgepea, K. et al. Adaptive laboratory evolution of native methanol assimilation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Commun 11, 5564 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19390-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19390-9

This article is cited by

-

Efficient biosynthesis of (R)-mandelic acid from styrene oxide by an adaptive evolutionary Gluconobacter oxydans STA

Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts (2023)

-

The oxygen-tolerant reductive glycine pathway assimilates methanol, formate and CO2 in the yeast Komagataella phaffii

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Reprogramming methanol utilization pathways to convert Saccharomyces cerevisiae to a synthetic methylotroph

Nature Catalysis (2023)

-

Microbial engineering strategies to utilize waste feedstock for sustainable bioproduction

Nature Reviews Bioengineering (2023)

-

Characterisation of acetogen formatotrophic potential using Eubacterium limosum

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.