Abstract

Defects from grain interiors and boundaries of perovskite films cause significant nonradiative recombination energy loss, and thus perovskite films with controlled crystallinity and large grains is critical for improvement of both photovoltaic performance and stability for perovskite-based solar cells. Here, a methylamine (MA0) gas-assisted crystallization method is developed for fabrication of methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) perovskite films. In the process, the perovskite film is formed via controlled release of MA0 gas molecules from a liquid intermediate phase MAPbI3·xMA0. The resulting perovskite film comprises millimeter-sized grains with (110)-uniaxial crystallographic orientation, exhibiting much low trap density, long carrier lifetime, and excellent environmental stability. The corresponding perovskite solar cell exhibits a power conversion efficiency (PCE) of ~ 21.36%, which is among the highest reported for MAPbI3-based devices. This method provides important progress towards the fabrication of high-quality perovskite thin films for low-cost, highly efficient and stable perovskite solar cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic–inorganic hybrid perovskites—such as MAPbX3 (X = I−, Br−, or Cl−)—have attracted increasing attention as light-harvesting materials in low-cost and high-efficiency photovoltaic devices due to their solution processability and excellent optical and electrical properties, such as strong light absorption, long electron–hole diffusion length, and low exciton-binding energy1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. As an active layer, the quality of the perovskite films (coverage, grain size, and crystal orientation) is strongly related to the device performance and stability13,14,15,16. It is generally believed that the primary energy loss in perovskite solar cells is ascribed to the nonradiative recombination of carriers due to trap states at grain boundaries, surfaces, and point defects within the crystallites17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. The high coverage of perovskite film ensures adequate absorption and avoids possible short circuit, and the crystal domains with large grain size and highly orientation are believed to reduce the density of grain boundaries and promote the efficient transport of electrons and holes to their corresponding electrodes. Concurrently, these defects such as the grain boundaries may cause water molecule diffusion and ion migration, deteriorating the device stability25,26,27. Therefore, a perovskite film with controlled crystallinity and large grains is highly desirable for efficient and stable solar cells.

In order to improve the quality of the perovskite films, some effective methods have been reported by using various solution processing techniques, such as solvent engineering28,29, solvent annealing30, hot casting31, intramolecular exchange32,33, and additive-assisted process27,34,35. However, the solution-processed perovskite polycrystalline films typically have small grains with sizes of sub-100 nanometers to several micrometers, and the grains in the films usually exhibit various crystallographic orientations, limiting efficient charge transfer in the films28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. By the way, a high-temperature solution-casting method was reported to obtain perovskite film with millimeter-sized domains31; however, the domains in the film are not single crystals but rather large-size islands with smaller crystal grains36,37. On the other hand, a few research groups have explored the fabrication of single-crystalline perovskite thin films to remove the above-mentioned imperfections in the polycrystalline films38,39,40. However, it is a great challenge to directly grow a single-crystalline layer on a desired substrate with both large lateral dimensions and thin film thickness (<1 μm), which is desirable for high-efficiency perovskite solar cells38,39,40. In 2015, Zhou et al. reported a methylamine (MA0) induced defect-healing (MIDH) method for the processing of highly uniform and crystalline MAPbI3 perovskite films from a liquid intermediate MAPbI3·xMA0 41. Since then, the MIDH method has been extensively employed for improving the quality of perovskite films41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55. In these reports, the grain sizes in the perovskite films are usually limited to 100–200 nm due to the rapid growth of the perovskite films from the rapid MA0 self-degassing process.

In this work, a modified MIDH method is developed for the fabrication of MAPbI3 perovskite films, where the nucleation and crystallization of the perovskite can be adjusted by controlled release of MA0 gas from the liquid intermediate. The resulting perovskite film presents (110)-uniaxial crystallographic orientation with millimeter-sized grains, exhibiting much low trap density and long carrier lifetime. The perovskite solar cells have been fabricated, yielding a stabilized power conversion efficiency (PCE) of ~21.36% with negligible hysteresis and excellent environmental stability.

Results

Methylamine gas-assisted growth of perovskite film

We prepared a methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) perovskite film by combining solution deposition and methylamine-assisted method. The basic steps are illustrated schematically in Fig. 1a. First, a pristine MAPbI3 film is deposited on a mesoporous TiO2 substrate via simple one-step solution method1,2,3. After drying, the perovskite film is loaded face up in a closed chamber in which reagent mixture of methylammonium chloride and sodium hydroxide is enclosed. At an elevated temperature, MA0 gas is created inside, and a liquid intermediate MAPbI3·xMA0 is formed41,42,43. Generally, when a raw MAPbI3 thin film is exposed to CH3NH2 (MA0) gas source at room temperature (RT), a liquid intermediate MAPbI3·xMA0 is quickly formed through uptake of the MA0 gas molecules, where the equilibrium is built, as shown below:

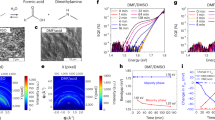

a The steps of the method: (I) formation of a liquid CH3NH3PbI3·xMA intermediate film; (II) controlled growth of the nuclei; and (III) controlled growth of the perovskite film. b Equilibrium partial pressure of the MA0 gas as a function of temperature for the MAPbI3 perovskite crystallization. c Photographic image and d top-view SEM image of the large-grain MAPbI3 perovskite film.

The liquid phase is metastable only under a certain partial pressure of MA0 gas (PMA), and upon removal of the MA0 gas atmosphere, Eq. 1 will move to the right quickly due to the decreased PMA (close to 0). This results in rapid release of the MA0 molecules from the liquid phase (<1 s), inducing supersaturation and thus the formation of massive nuclei. The process is uncontrollable and dominated by the nucleation process, thus leading to formation of fine grained (~100 nm in size) thin films.

In this report, the crystallization of MAPbI3 is processed at a certain temperature in a closed system in MA atmosphere with a controlled PMA. The intervals of the PMA for the crystallization are determined at a certain temperature ranging from 100 to 180 °C. (Supplementary Table 1; for details, see “Methods”), and a mid-interval value is roughly assigned as the equilibrium PMA at the temperature (Fig. 1b). The enthalpy is calculated to be \({\Delta} _rH_m^\theta \) = 150.14 kJ mol−1 based on the van’t Hoff equation assuming that x is 4 in the intermediate (Supplementary Fig. 1). In this case, the supersaturation could be greatly reduced by slow release of MA molecules from the liquid intermediate (by altering the PMA in the interval), leading to low nucleation density and allowing more time for the growth of the large grains in the interval. This process is dominated by the slow growth crystallization process, significantly different from the fast nucleation-driven process reported previously41. The film-forming process is similar to the previous report, where the MAPbI3 film with tens of micron-sized grains was formed from the liquid phase under a constant MA atmosphere by tuning the annealing temperature43.

For clearly exemplifying the unique process, a MAPbI3 perovskite film was intentionally prepared from the liquid phase MAPbI3·xMA0 on a porous TiO2 film at 120 °C (the PMA interval: 0.144–0.096 Mpa), where the MA gas was slowly released from 0.144 to 0.11 MPa, and then rapidly discharged. The optical microscopic image of the resultant perovskite film was recorded as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. In the image, one large crystal (~1 mm in size) with a regular shape (square) is observed, which is surrounded by a large number of small grains with size about 100 μm. The result may indicate that low nucleation density can be realized in the crystallization through the slow release of the MA0 gas.

In our case, we observed that the grain size was strongly dependent on the release rate of MA gas from the liquid phase (discussed below), that is, the degree of the supersaturation. Thus we speculate that homogeneous nucleation could occur in the system. The slow release of MA gas from the liquid phase may favor for the formation of low nucleation sites and also allow more time for the growth of large grains. It should be noted that nonclassical nucleation mechanisms may also be involved here, and further investigation is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Figure 1c shows a typical photographic image of the perovskite film, prepared at 120 °C with a 30-s MA0 degassing time. The film has uniformly packed grains with grain sizes 1–5 mm, which is about four orders of magnitude larger than that in the MAPbI3 film processed by the MIDH method (Supplementary Fig. 3b)41. In the following studies, we name the 30-s sample and the MIDH sample as large-grain film and small-grain film, respectively. Figure 1d shows the scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image of the large-grain perovskite film. The top-view images of the MAPbI3 perovskite films with low and high magnification are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3c, d, respectively, demonstrating the formation of a smooth, dense, and uniform perovskite layer by the current method.

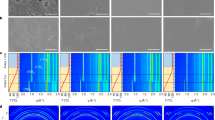

Figure 2a shows optical microscopic images of the perovskite films, evolved from the liquid intermediate with different MA0 degassing times within the internals of the crystallization. It is clear that the grain size in the films is strongly dependent on the time. Upon rapid degassing (~1 s) at 120 °C, the grain size is only tens of micrometer, while the size is greatly increased to millimeters when the degassing time is extended to 30 s. With further extending the degassing time (60 s), the grain size seems unchanged. Figure 2b shows the cross-sectional SEM image of the large-grain film on a TiO2-coated substrate. The perovskite film is smooth and flat with no discernable grain boundaries over the entire measure range, consistent with the top-view SEM images (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). In addition, we prepared the large-grain films at different temperatures with 30 s degassing time, and the top-view SEM and optical microscope images are shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. The grain sizes were comparable for all the large-grain films, indicating that the grains have already grown up within the time at the different temperatures. Supplementary Fig. 6 presents the optical microscopic images of the MAPbI3 films prepared at low temperatures below 373 K. In addition, the atom force microscope (AFM) was employed to characterize the morphologies of the small-grain film and different large-grain films with different degassing time (1, 15, 30, and 60 s). The root mean square roughness value of the different large grain films are comparable, with 0.67 nm for 1 s, 0.73 nm for 15 s, 0.61 nm for 30 s, and 0.76 nm for 60 s, respectively, all of which are lower than that (2.1 nm) for the small-grain film (Supplementary Fig. 7). However, large roughnesses are observed in the regions of the texture (3.1 nm, corresponding to the square line observed in the SEM) and the grain boundary (42 nm), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) mapping was also recorded across two adjacent grains (Supplementary Fig. 9).

a Optical microscopic images of the MAPbI3 perovskite films prepared from the liquid intermediate with different degassing times (1, 15, 30, and 60 s) in the internal. b Cross-sectional scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image of the large-grain MAPbI3 perovskite film. c X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern and rocking curve (inset) of the large-grain MAPbI3 perovskite film. d Cross-sectional transmission electron microscopic (TEM) image and selected area electron diffractions (SAED) taken from the different locations (labeled 1–3) from bottom to top in the perovskite film.

The ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectra of the large-grain film and the pristine perovskite film are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10a. Both the films show almost the same absorption edges, and the large-grain film presents stronger absorption at the full light absorption range when compared with the pristine film. The steady-state photoluminescence (PL) spectra show that the emission peak intensity for the large-grain film is nearly two orders of magnitude higher than that of the pristine film, indicative of reduced surface defect and enhanced crystallinity in the large-grain film (Supplementary Fig. 10b). The inset in Supplementary Fig. 10b shows a 12-nm blue shift of the PL peak for the large-grain perovskite film.

Properties of the perovskite film

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the large-grain film in Fig. 2c exhibits intense signals only in the <110> crystalline directions, indicating that the exposed face is {110} crystal plane in the film. The XRD pattern of the powders (scratched from the film) matches a tetragonal crystal structure (Supplementary Fig. 11), which is the most stable phase at RT56. In addition, a rocking curve, which is the most reliable measure of the average orientation of a particular crystallographic phase, was measured for the large-grain film, exhibiting a small full width of 0.34° at half maximum (FWHM) for the {110} plane. The FWHM value is one order of magnitude lower than those for the polycrystalline perovskite films with micrometer-sized grains21,57, and is close to the value (0.33°) for the single-crystal perovskite thin film reported previously39, further demonstrating that the grain has a sharp preferred orientation. In order to get more information of the grain orientation, one large grain cut from the film was measured by two-dimensional detector. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12, only two visible diffraction points (not arcs) and the point of beam are observed, further indicating that the large grain has a strong preferred orientation. Moreover, the polarized optical microscopic images of the large-grain film were recorded, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 13, where the extinction or transmission state was observed across one large grain from the film when measured by changing the angle of polarizers.

To verify the uniformity of the crystallographic orientation in radial direction in the large-grain film, selected area electron diffraction (SAED) was performed on the cross-section specimen, prepared with the focused ion beam (FIB) along the growth striation on the surface. As shown in Fig. 2d, three SAED patterns, taken at the top, middle, and bottom locations of the specimen, are consistent with the single-crystal tetragonal phase with the same zone axis [001], confirming a single-crystalline structure in the area from the bottom to top.

To inspect the phase purity and the quality over a large scale for the large-grain perovskite film, a SEM-based electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) technique was employed58. In the experiment, a focused electron beam illuminates at an angle of 70° to the surface of the film, and the diffraction pattern (Kikuchi patterns) is then transformed into the crystallographic orientation map through statistical analysis. As shown in Fig. 3a, an area of 1.75 × 1.21 mm2 was randomly selected from the film for the experiment. In the X axis inverse pole figure (Fig. 3b), each individual grain presents nearly the same color, indicating the same crystallographic orientation. A point-to-point misorientation difference, measured along the diagonal line of one grain, is measured to be <0.6° (Fig. 3c), indicating perfect crystal orientation within the grain59. Most interestingly, all the grains in the image present uniform color in the inverse pole figure Z direction, normal to the sample surface (Fig. 3d), implying that all crystallites are very well oriented with the {110} planes, parallel to the substrate. The results are in line with the XRD measurement. This uniaxial orientation is highly desirable for efficient charge transport in the perovskite-based optoelectronic devices. It should be noted that, in the traditional solution-processed perovskite films, various solid-state plumbate intermediates are inevitably generated during the growth of the perovskites, and the resulting films usually present random crystallographic orientations60,61. Here the high degree of order obtained could be ascribed to only phase-pure MAPbI3 crystallization from the solvent-free liquid phase, and a similar result was observed for the MAPbI3 film crystallized from an ionic liquid62.

We also prepared the perovskite film at 120 °C with a short degassing time (~2 s). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 14, the fast degassing process resulted in the formation of relatively small grains with a broad size distribution (50–150 µm) in the film. While each individual grain shows a uniform color in the X axis inverse pole figure, indicating single orientation, the image present non-uniform color distribution in the inverse pole figure Z direction, implying the film lacking of complete orientation. The result indicates that a slow crystallization rate is necessary for the growth of the MAPbI3 film with both uniaxial orientation and large grains. We also tried to measure the EBSD mapping of the small-grain film, and the mapping is shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, where the indexing success rate is only 0.57% with little effective information about the crystal orientation. Under the identical conditions, the EBSD mapping of the large-grain film can be measured, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 16. The difference could be explained as follows: for small-grain film, the scanning range is relatively small, and the probe beam current is the same as the same dwell time on the sample surface. In this case, the sample will receive more electrons per unit area at the same time, causing larger damage on the small-grain film as compared with the large-grain film. In addition, we extended the method for the fabrication of large-grain MAPbBr3 film, and the results are shown in Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18.

To evaluate the trap-state density (Nt), the large-grain MAPbI3 film was inserted between fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) and gold electrodes, and the evolution of the space-charge-limited current at different biases was recorded. The trap density (Nt) is estimated based on the equation: Nt = 2ε0εrVTFL/eL2, where ε0 and εr are the absolute and relative dielectric constants, respectively, e is the elemental charge, VTFL is the onset voltage, and L is the thickness of the film. As shown in Fig. 4a, the large-grain film exhibits a remarkably low trap density Nt = ~9.7 × 1013 cm−3, which is more than two orders of magnitude lower than that (~1.6 × 1016) for the small-grain MAPbI3 film (Supplementary Fig. 19). The significantly reduced Nt can originate from the high crystallinity and fewer grain boundaries in the large-grain perovskite film19,35. To further study the charge dynamics, the time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectroscopies were performed for both the large- and small-grain MAPbI3 films (Fig. 4b). Fitting the TRPL data with a stretched exponential function, average carrier lifetimes of 271 and 27.8 ns are extracted for the large-grain film and the small-grain film, respectively. The longer lifetime of the large-grain film is indicative of slow recombination due to the reduced defect sites in the large-grain perovskite film, which is consistent with the high steady-state PL intensity. The high PL intensity and long PL decay lifetime illustrate that the nonradiative recombination of photo-generated carriers is significantly reduced due to the high crystallinity and low density of grain boundaries in the large-grain perovskite film.

a Current–voltage (I–V) trace of the large-grain MAPbI3 film, showing Ohmic, TFL, and Child region. The onset voltage of the TFL region is ~0.011 V. b Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) decay measurements of the large- and small-grain MAPbI3 films. c Characteristic I–V curves of the large- and small-grain devices. Solid lines and dashed lines indicate the reverse- and forward-bias scan directions, respectively. d The IPCE spectrum of the large-grain device and the integrated short-circuit current density (JSC) versus wavelength.

Solar cell performance

To evaluate the photovoltaic metrics of the large-grain MAPbI3 film, a device configuration of FTO/compact TiO2/meso-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-OMeTAD/Au was constructed to measure photocurrent density versus voltage (J–V) curve and incident photon-to-current conversion efficiency (IPCE). For comparison, the small-grain MAPbI3 film was employed with the same device configuration. The statistical data on the PV metrics for both the devices are listed in Supplementary Fig. 20. The J–V curves of champion devices are presented in Fig. 4c with the figures of the merit in the inset. For a reverse scan, the large-grain device shows a PCE of 21.36% with short-circuit current voltage (JSC) of 22.81 mA cm−2, open-circuit voltage (VOC) of 1.178 V, and fill factor (FF) of 0.795, whereas the small-grain device delivers a lower PCE of 15.69% with JSC of 20.76 mA cm−2, VOC of 1.063 V, and FF of 0.711. For a forward scan, the former shows negligible hysteresis with a PCE of 21.14%, while the latter exhibits large hysteresis with a PCE of 12.47%. The low hysteresis can be ascribed to the low defect sites in the perovskite film with large grains and high crystallinity, which effectively prevent ion mobility and thus charge accumulation at the perovskite surface17,18,19. Figure 4d shows high IPCE values over the spectral range from 400 to 800 nm for the large-grain device, which is in accordance with the optical absorption profile. The integrated JSC (22.67 mA cm−2) from the IPCE is in good agreement with the J–V measurement. A stabilized PCE of ~21.36% is recorded for the large-grain device by holding the voltage at the maximum power point (Supplementary Fig. 21), which is among the highest values for the single-cation/anion perovskites28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. The best device has been certified by a third party (Supplementary Fig. 22), exhibiting 21.29% under the reverse scan direction (1.2 to −0.1 V) and 20.12% under the forward scan direction (−0.1 to 1.2 V) under AM 1.5 G full-sun illumination (100 mW cm−2). In addition, the I–V curves of the different grain-size-based devices (time is 1, 15, 30, or 60 s for the crystallization of the MAPbI3 films) were prepared, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 23. We observed that the device-1 s showed relatively poor conversion efficiency (~19%), as compared with the other three devices, all of them have comparable efficiencies (~21%). The low efficiency for the device-1 s may be ascribed to the small grain and relatively poor orientation in the film, as evidenced by the relatively low values of VOC and FF.

The deficiency of long-term stability of perovskite materials has become one of the greatest barriers to the commercialization, and the degradation is generally initialized from the defect sites at surfaces and grain boundaries, which are more reactive toward moisture. For poly-crystalline perovskite films with sub-micrometer-sized grains, many organic molecules have been deposited on the film to passivate the defects during the past years10,11,12. In our cases, the large-grain perovskite films without the post-treatment were constructed in the solar cells for stability test. The environmental stability of the devices without encapsulation was tested at 65 RH% at 30 °C in air, at 65 °C in nitrogen environment, and under thermal stressing and full-spectrum sunlight irradiation, respectively. The results are shown in Fig. 5a–c. At 65 RH% and 30 °C, the device employing the large-grain perovskite film shows greatly improved stability in comparison with that of the small-grain device. The large-grain device retains over 80% of its initial PCE after 200 h, whereas the control device decays to <20% of the original performance. In addition, the XRD patterns of the large- and small-grain films were recorded before and after exposure to humidity of 65% for 200 h at RT in air, and the results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 24. After the 200-h aging, a set of peaks of PbI2 appeared with high intensity for the small-grain film, showing poor stability. In contrast, the large-grain film showed greater stability, showing very weak peaks from PbI2 and the hydrate intermediate under the same aging condition. The enhanced humidity stability is likely to be attributed to the intrinsic properties such as uniaxially oriented grains and reduced grain boundaries, which can effectively inhibit the permeation of moisture in the large-grain perovskite film25. As shown in Fig. 5d, the large-grain film did not change markedly in color over 200 h, showing excellent stability, whereas the small-grain film turned yellow under the same conditions, because of fast decomposition of MAPbI3 with water, and forming PbI2 in the small-grain film. Likewise, the enhanced stability in the large-grain device can also be observed under thermal stressing and full-spectrum sunlight irradiation, as shown in Fig. 5b, c. The large-grain devices retain around 80 and 85% of their initial PCEs, respectively, under thermal stressing at 65 °C and under the illumination after 1000 h, whereas the control devices decay to about 30 and 60% of the original PCEs, respectively, under the identical conditions. The high stability under the illumination and the heat could be ascribed to effective suppression of ion migration in the large-grain perovskite film with high crystallinity and reduced grain boundaries26,27. The significantly improved stability as well as high efficiency indicate the great potential of the large-grain perovskite solar cell for industrial applications.

a–c Stability assessment of non-encapsulated perovskite solar cells with the large-grain and the small-grain perovskite films. Humidity stability at 65 RH% and 30 °C in air (a), heat stability at 65 °C in nitrogen environment (b), and light stability testing under full-spectrum sunlight at room temperature in nitrogen environment (c). d Photographs of the large- and small-grain perovskite films before and after exposure to humidity of 65% for 200 h at room temperature in air (the size of the films is 20 × 20 mm2).

Discussion

In summary, the methylamine gas-assisted crystallization method was developed for the fabrication of high-quality perovskite films. In the process, the perovskite film is formed from a liquid intermediate phase MAPbI3·xMA0 via controlled release of MA0 gas molecules. By the method, we obtained a uniaxial-oriented perovskite films with millimeter-sized single-crystal grains, which are comprehensively evaluated by using XRD, XRD-rocking curve, and EBSD techniques for the first time. The large-grain perovskite film possesses a low trap-state density and long charge carrier lifetime, which are comparable to those of the single-crystal thin film. The resulting perovskite solar cells exhibited both high efficiency and excellent environmental stability. This represents a major advance in the fabrication of high-quality perovskite films. On the basis of our results, we believe that the uniaxial-oriented large-grain perovskite films will find widespread application in low-cost, high-performance, and stable perovskite optoelectronics devices.

Methods

Materials

Lead (II) iodide (99.999%) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Methylammonium chloride, methylammonium bromide (>99.5%), methylammonium iodide (>99.5%), and Spiro-OMeTAD were purchased from Xi’an Polymer Light Technology in China.

Fabrication of TiO2 electrode

FTO glasses (TECA7, 6–8 ohm sq−1, NSG, Japan) were cleaned with deionized water, alcohol, and acetone successively via ultrasonic process and then cleaned with UV ozone for 10 min. A 30-nm TiO2 blocking layer was deposited on the FTO by spray pyrolysis at 450 °C from a precursor solution of 20 mM titanium diisopropoxide bis(acetylacetonate) solution. A 150-nm mesoporous TiO2 layer was spin-coated on the substrate with a diluted TiO2 paste (18NR-T, Dyesol) in ethanol with a weight ratio of 1:6 and then calcined at 500 °C for 30 min in air.

Methylamine-assisted recrystallization of MAPbI3 film

The starting MAPbI3 perovskite films were deposited the TiO2 electrode using the conventional one-step method, where a 47 wt% PbI2:MAI (molar ratio 1:1) solution in N,N-dimethylformamide was spin-coated at 177.1 × g (~4000 rpm) for 30 s, followed by heat treatment at 100 °C for 10 min. The raw perovskite film was loaded face up in a closed chamber. Before the loading, a beaker with a mixture of methylammonium chloride, sodium hydroxide, and CaO dryer was loaded in advance. After that, the chamber was moved in an oil bath pot at RT, and the air in the chamber was exchanged by N2 gas. With the heating by the bath, the pressure rises upon the generation of MA gas. At a certain temperature between 100 to 180 °C, the interval of the MA partial pressure (PMA) for the crystallization of the MAPbI3 were determined using the bisection method according to the morphology change before and after the MA treatment. The pressure can be adjusted by the valve on the chamber. In the interval, a slow MA degassing is required for the film growth. Generally, a degassing time in the internal is within 1 min. After the degassing, N2 gas was input, and the chamber was moved out of the oil bath. After being cooled to RT, the sample was taken out. This operation is also suitable for the fabrication of large-grain MAPbBr3 film.

Fabrication of solar cells

On the resulting perovskite film, a HTM was deposited by spin coating a solution, which was prepared by dissolving 72.3 mg (2,29,7,79-tetrakis(N, N-di-p-methoxyphenylamine)-9,9-spirobifluorene) (spiro-MeOTAD), 28.8 ml 4-tert-butylpyridine, and 17.5 ml of a stock solution of 520 mg ml lithium bis(trifluoromethylsulphonyl)imide in acetonitrile. Finally, 80 nm of gold was thermally evaporated on top of the device to form the back contact.

Measurement and characterization

The absorption spectra were collected using a UV/Vis spectrometer (SHIMADZU, UV-1800 UV/Vis Spectrophotometer) in the wavelength range of 300–900 nm. Steady-state PL was measured using Edinburgh FLS980 system with an excitation at 485 nm. Optical and polarization images of perovskite films were obtained by Nikon LV100ND optical microscope. The powder XRD patterns and rocking curves were measured using a PANalytical Empyrean X-ray powder diffractometer equipped with a 2.2 kW Cu Kα radiation (1.54 Å). The sample of rocking curves were cutting the films with the grain boundaries. The 2D XRD data were obtained at 1W1A Diffuse X-ray Scattering Station, Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF-1W1A). The AFM and KPFM data were collected on a Bruker Dimension Icon SPM by using doped silicon PFQNE-AL probes (Bruker). The SEM images were taken from a Hitachi S-4800 SEM operated at 5 kV. EBSD patterns were acquired by Symmetry EBSD detector of Oxford Instruments on a Hitachi SU5000 SEM at 20 kV with sample tilted 70° and analyzed using the AZtec and Channel 5 softwares.

To obtain the TEM sample, the sample was milled by an FIB (the FEI Helios Nanolab G3 CX). Before milling, 15 nm amorphous carbon was first deposited on the surface of the sample. Then a rectangle area was chosen that was parallel to the crystal grain and 700 nm and 1 μm Pt was deposited to protect the sample at 5 kv, 0.17 nA and 30 kv, 80 pA. The milling of the cross-sections used a gallium ion source at 30 kV, 0.79 nA for regular and 5 kV, 7 pA for polishing the cross-section. Finally, a cross-section 70-nm thick was obtained.

Current–voltage (J–V) characteristics were recorded by applying an external potential bias to the cell while recording the generated photocurrent with a Keithley model 2400 digital source meter. The light source was a 300 W collimated xenon lamp (Newport) calibrated with the light intensity to 100 mW cm−2 under AM 1.5 G solar light conditions by a certified silicon solar cell. The J–V curve was recorded by the reverse scans with a rate of 100 mV s−1. The active area was determined by metal shadow mask with an aperture of 0.0725 cm2. The IPCE for solar cells was performed using a commercial set-up (PV-25 DYE, JASCO). A 300 W Xenon lamp was employed as a light source for the generation of a monochromatic beam. IPCE spectra were recorded using monochromatic light without white light bias. Calibrations were performed with a standard silicon photodiode.

Device stability testing

The humidity stability for both the unencapsulated perovskite films and the relative devices was conducted in a temperature–humidity chamber (DHS-100, Beijing Zhongkehuanshi Instrument Co. Ltd., China). In the experiment, the temperature is maintained at 30 °C with relative humidity 65%. The photovoltaic performance of the aged devices was measured under ambient conditions.

The bisection method for the determination of the equilibrium PMA range

There are several prerequisites for the determination of the equilibrium PMA range:

-

1.

The atmospheric pressure is taken as 0.1 MPa in the calculation.

-

2.

The raw film and chamber must be preheated.

-

3.

This method can roughly measure the methylamine gas interval.

For the measurement of the interval of the equilibrium PMA, a starting point of the bisection should be determined at first. The lower limit of the interval is initially set to 0, and the upper limit is determined by the following method. At first, adding enough reactants to the chamber, recording the pressure value when the pressure is stable, and then turning valve to let the gas release slowly. The initial value is based on the result of morphological observations by a microscope: if the grains obtained are larger than several tens of microns with texture, the previously recorded pressure value is set as the initial value, otherwise the experiment should be repeated with more amount of reactants to increase PMA until the large grains appear.

After determining the initial value, the interval is divided into two sections: the initial value to the half of the initial value, and the half of the initial value to 0. One of the sections is selected, and the gas is slowly released only in the corresponding interval. If large grains appear on the film, it indicates that the equilibrium PMA is within this range. If not, it must be in another section. Then the two end points of this interval are reset as the new starting points of the bisection. Repeating the steps for several times, a relatively accurate interval could be determined as to where the equilibrium PMA is located.

It should be noted that a special case could remain, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, where the equilibrium PMA is just near the breakpoint one divided earlier.

It should be emphasized that, after the gas released, the pressure value displayed on the pressure gauge does not indicate the partial pressure of the methylamine gas in the chamber at that time. An example is given below to illustrate the calculation process.

It is assumed that the pressure of methylamine gas in the initial chamber is 0.5 MPa, and the gas is released until the gauge pressure shows 0.3 MPa. At this time, the partial pressure of methylamine gas in the chamber is calculated as follows.

Initial total gas pressure in the chamber:

Final total gas pressure in the chamber:

Initial partial pressure of methylamine gas in the chamber:

Final partial pressure of methylamine gas in the chamber:

Estimate of the enthalpy for the methylamine desorption reaction

In the degassing reaction, the MAPbI3 crystallizes from the liquid intermediate MAPbI3·xMA. Assuming the x (≈4) value in the intermediate is not dependent on the MA partial pressure, the degassing reaction can be written as Eq. 2. In the reaction, the enthalpy change was achieved using the well-known van’t Hoff equation \({\int} {{\rm{dln}}K^\theta } = \int {\frac{{{\Delta} _rH_m^\theta }}{{RT^2}}}\, {\rm{d}}T\), where Kθ is the equilibrium constant, T the absolute temperature, and R the gas constant. In the reaction, the Kθ is determined by the partial equilibrium pressure of the methylamine gas and fugacity coefficients φ, as shown in Eq. 3. Supplementary Table 1 lists the intervals of the MA partial pressures for the reaction at different temperatures, and the mid-interval value is roughly assigned as the equilibrium PMA at the temperature. φ is calculated from Eq. 4, where the acentric factor ω is 0.281 according to the reference63, and the values of \({\mathrm{log}}(\frac{f}{p})^{(0)}\) and \({\mathrm{log}}(\frac{f}{p})^{(1)}\) at the different temperatures are collected from the reference64. Thus the Kθ values at the different temperatures can be calculated according to Eq. 3. Assuming that the enthalpy change is not changed with the temperature, the van’t Hoff equation is given as Eq. 5. The lnKθ versus 1/T is plotted (Supplementary Fig. 1), giving ~150.14 kJ mol−1 of the \({\Delta} _rH_m^\theta \).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kojima, A., Teshima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal halide perovskites as visible-light sensitizers for photovoltaic cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6050–6051 (2009).

Kim, H.-S. et al. Lead iodide perovskite sensitized all-solid-state submicron thin film mesoscopic solar cell with efficiency exceeding 9%. Sci. Rep. 2, 591–597 (2012).

Lee, M., Teuscher, J., Miyasaka, T., Murakami, T. N. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient hybrid solar cells based on meso-superstructured organometal halide perovskites. Science 338, 643–647 (2012).

Burschka, J. et al. Sequential deposition as a route to high-performance perovskite-sensitized solar cells. Nature 499, 316–319 (2013).

Li, N. et al. Cation and anion immobilization through chemical bonding enhancement with fluorides for stable halide perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 4, 408–415 (2019).

Zheng, X. et al. Defect passivation in hybrid perovskite solar cells using quaternary ammonium halide anions and cations. Nat. Energy 2, 17102 (2017).

Yang, W. et al. Iodide management in formamidinium-lead-halide–based perovskite layers for efficient solar cells. Science 356, 1376–1379 (2017).

Tan, H. et al. Efficient and stable solution-processed planar perovskite solar cells via contact passivation. Science 355, 722–726 (2017).

Christians, J. A. et al. Tailored interfaces of unencapsulated perovskite solar cells for >1,000 hour operational stability. Nat. Energy 3, 68–74 (2018).

Jung, E. H. et al. Efficient, stable and scalable perovskite solar cells using poly(3-hexylthiophene). Nature 567, 511–515 (2019).

Jeon, N. J. et al. Compositional engineering of perovskite materials for high-performance solar cells. Nature 517, 476–480 (2015).

Bai, S. et al. Planar perovskite solar cells with long-term stability using ionic liquid additives. Nature 571, 245–250 (2019).

Eperon, G. E., Burlakov, V. M., Docampo, P., Goriely, A. & Snaith, H. J. Morphological control for high performance, solution processed planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 151–157 (2014).

Dualeh, A. et al. Effect of annealing temperature on film morphology of organic–inorganic hybrid pervoskite solid-state solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 3250–3258 (2014).

Huang, L. et al. CH3NH3PbI3-xClx films with coverage approaching 100% and with highly oriented crystal domains for reproducible and efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 22015–22022 (2015).

Giesbrecht, N. et al. Synthesis of perfectly oriented and micrometer-sized MAPbBr3 perovskite crystals for thin-film photovoltaic applications. ACS Energy Lett. 1, 150–154 (2016).

Snaith, H. J. et al. Anomalous hysteresis in perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 1511–1515 (2014).

Sherkar, T. S. et al. Recombination in perovskite solar cells: significance of grain boundaries, interface traps, and defect ions. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1214–1222 (2017).

Shao, Y., Xiao, Z., Bi, C., Yuan, Y. & Huang, J. Origin and elimination of photocurrent hysteresis by fullerene passivation in CH3NH3PbI3 planar heterojunction solar cells. Nat. Commun. 5, 5784 (2014).

Chen, Q. et al. Controllable self-induced passivation of hybrid lead iodide perovskites toward high performance solar cells. Nano Lett. 14, 4158–4163 (2014).

Niu, G., Yu, H., Li, J., Wang, D. & Wang, L. Controlled orientation of perovskite films through mixed cations toward high performance perovskite solar cells. Nano Energy 27, 87–94 (2016).

Kim, D. H. et al. 300% Enhancement of carrier mobility in uniaxial-oriented perovskite films formed by topotactic-oriented attachment. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606831 (2017).

Tang, G. et al. Solution-phase epitaxial growth of perovskite films on 2D material flakes for high-performance solar cells. Adv. Mater. 31, 1807689 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Single-crystal MAPbI3 perovskite solar cells exceeding 21% power conversion efficiency. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 1258–1259 (2019).

Wang, Q. et al. Scaling behavior of moisture-induced grain degradation in polycrystalline hybrid perovskite thin films. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 516–522 (2017).

Yuan, Y. & Huang, J. Ion migration in organometal trihalide perovskite and its impact on photovoltaic efficiency and stability. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 286–293 (2016).

Kim, M. et al. Methylammonium chloride induces intermediate phase stabilization for efficient perovskite solar cells. Joule 3, 1–14 (2019).

Xiao, M. et al. A fast deposition-crystallization procedure for highly efficient lead iodide perovskite thin-film solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 9898–9903 (2014).

Jeon, N. J. et al. Solvent engineering for high-performance inorganic–organic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 13, 897–903 (2014).

Xiao, Z. et al. Solvent annealing of perovskite-induced crystal growth for photovoltaic-device efficiency enhancement. Adv. Mater. 26, 6503–6509 (2014).

Nie, W. et al. High-efficiency solution-processed perovskite solar cells with millimeter-scale grains. Science 347, 522–525 (2015).

Yang, W. S. et al. High-performance photovoltaic perovskite layers fabricated through intramolecular exchange. Science 348, 1234–1237 (2015).

Li, F. et al. A novel strategy for scalable high-effciency planar perovskite solar cells with new precursors and cation displacement approach. Adv. Mater. 30, 1804454 (2018).

Liang, P.-W. et al. Additive enhanced crystallization of solution-processed perovskite for highly efficient planar-heterojunction solar cells. Adv. Mater. 26, 3748–3754 (2014).

Han, L. et al. Environmental-friendly urea additive induced large perovskite grains for high performance inverted solar cells. Sol. RRL 2, 1800054 (2018).

Zheng, Y. C. et al. Thermal-induced Volmer−Weber growth behavior for planar heterojunction perovskites solar cells. Chem. Mater. 27, 5116–5121 (2015).

Deng, Y. et al. Scalable fabrication of efficient organolead trihalide perovskite solar cells with doctor-bladed active layers. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 1544–1550 (2015).

Ye, T. et al. Single-crystalline lead halide perovskite arrays for solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 1214–1217 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Thin single crystal perovskite solar cells to harvest below-bandgap light absorption. Nat. Commun. 8, 1890 (2017).

Chen, Y.-X. et al. General space-confined on-substrate fabrication of thickness-adjustable hybrid perovskite single-crystalline thin films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 16196–16199 (2016).

Zhou, Z. et al. Methylamine-gas-induced defect-healing behavior of CH3NH3PbI3 thin films for perovskite solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9705–9709 (2015).

Chen, H. et al. A solvent- and vacuum-free route to large-area perovskite films for efficient solar modules. Nature 550, 92 (2017).

Jacobs, D. L. & Zang, L. Thermally induced recrystallization of MAPbI3 perovskite under methylamine atmosphere: an approach to fabricating large uniform crystalline grains. Chem. Commun. 52, 10743–10746 (2016).

Liu, T. et al. Reduction and oxidation of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) induced by methylamine (CH3NH2)-containing atmosphere for perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 4305–4311 (2016).

Conings, B. et al. Structure−property relations of methylamine vapor treated hybrid perovskite CH3NH3PbI3 films and solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 8092–8099 (2017).

Jiang, Y. et al. Post-annealing of MAPbI3 perovskite films with methylamine for efficient perovskite solar cells. Mater. Horiz. 3, 548 (2016).

Zhang, M. et al. Carrier transport improvement of CH3NH3PbI3 film by methylamine gas treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 31413–31418 (2016).

Zong, Y. et al. Thin-film transformation of NH4PbI3 to CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite: a methylamine-induced conversion–healing process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 14723–14727 (2016).

Jiang, Y. et al. A feasible and effective post-treatment method for high-quality CH3NH3PbI3 films and high-efficiency perovskite solar cells. Crystals 8, 44 (2018).

Wei, Y. et al. Precursor effects on methylamine gas-induced CH3NH3PbI3 films for stable carbon-based perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy 174, 139–148 (2018).

Pang, S. et al. Transformative evolution of organolead triiodide perovskite thin films from strong room-temperature solid−gas interaction between HPbI3‑CH3NH2 precursor pair. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 750–753 (2016).

Li, C., Pang, S., Xu, H. & Cui, G. Methylamine gas based synthesis and healing process toward upscaling of perovskite solar cells: progress and perspective. Sol. RRL 1, 1700076 (2017).

Zhou, Y. & Padture, N. P. Gas-induced formation/transformation of organic−inorganic halide perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 2166–2176 (2017).

Raga, S. R., Jiang, Y., Ono, L. K. & Qi, Y. Application of methylamine gas in fabricating organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Energy Technol. 5, 1750–1761 (2017).

Shao, Z. et al. A scalable methylamine gas healing strategy for high-efficiency inorganic perovskite solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 5587–5591 (2019).

Baikie, T. et al. Synthesis and crystal chemistry of the hybrid perovskite (CH3NH3)PbI3 for solid-state sensitised solar cell applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 5628–5641 (2013).

Wang, Z. et al. Efficient ambient-air-stable solar cells with 2D–3D heterostructured butylammonium-caesium-formamidinium lead halide perovskites. Nat. Energy 2, 17135 (2017).

Dingley, D. J. & Randle, V. Review: Microtexture determination by electron back-scatter diffraction. J. Mater. Sci. 27, 4545–4566 (1992).

Jariwala, S. et al. Local crystal misorientation influences non-radiative recombination in halide perovskites. Joule 3, 1–13 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. Chemical pathways connecting lead(II) iodide and perovskite via polymeric plumbate(II) fiber. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 15907–15914 (2015).

Zhou, Y., Game, O. S., Pang, S. & Padture, N. P. Microstructures of organometal trihalide perovskites for solar cells: their evolution from solutions and characterization. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 4827–4839 (2015).

Moore, D. T. et al. Direct crystallization route to methylammonium lead iodide perovskite from an ionic liquid. Chem. Mater. 27, 3197–3199 (2015).

Yaws, C. L. & Narasimhan, P. K. in Thermophysical Properties of Chemicals and Hydrocarbons (ed. Carl, L. Y.) Ch. 1 (William Andrew Publishing, Norwich, NY, 2009).

Chen, X. Z., Cai, Z. Y., Hu, W. M. & Qian, C. Chemical Thermodynamics 3rd edn (Chemical Industry Press, Beijing, 2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. X. Yang of Oxford Instruments for his help on EBSD test and analyses, Professor Y. Shi of Institute of physics, CAS for discussions; Professor L. Chen of University of Science & Technology Beijing for assistance in crystal analysis; and Dr. X. Hao of Institute of chemistry, CAS for assistance in XRD analysis. A portion of this work is based on the data obtained at BSRF-1W1A. The authors gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of the beamline scientists at BSRF-1W1A beamline. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61874123, 21572235), the National Key R and D Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFA0208501), and the “Strategic Priority Research Program” of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDA09020000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.-J.J. developed the basic concept and coordinated the project. H.F fabricated and characterized photovoltaic devices, optimized device performance, and fabricated high-performance devices. F.L. contributed to the fabrication and characterization of photovoltaic devices. P.W. contributed to the SEM measurement. Z.G. and J.H. analyzed the data. B.G. contributed to the FEM measurement. X.Z., L.-M.Y., and Y.S. contributed to the supervision of the project. K.-J.J. and H.F. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Qingfeng Dong and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, H., Li, F., Wang, P. et al. Methylamine-assisted growth of uniaxial-oriented perovskite thin films with millimeter-sized grains. Nat Commun 11, 5402 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19199-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19199-6

This article is cited by

-

Inverted perovskite solar cells with over 2,000 h operational stability at 85 °C using fixed charge passivation

Nature Energy (2023)

-

Grain boundary passivation via balancing feedback of hole barrier modulation in HfO2-x for nanoscale flexible electronics

Nano Convergence (2022)

-

The Main Progress of Perovskite Solar Cells in 2020–2021

Nano-Micro Letters (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.