Abstract

Sources of entangled electromagnetic radiation are a cornerstone in quantum information processing and offer unique opportunities for the study of quantum many-body physics in a controlled experimental setting. Generation of multi-mode entangled states of radiation with a large entanglement length, that is neither probabilistic nor restricted to generate specific types of states, remains challenging. Here, we demonstrate the fully deterministic generation of purely photonic entangled states such as the cluster, GHZ, and W state by sequentially emitting microwave photons from a controlled auxiliary system into a waveguide. We tomographically reconstruct the entire quantum many-body state for up to N = 4 photonic modes and infer the quantum state for even larger N from process tomography. We estimate that localizable entanglement persists over a distance of approximately ten photonic qubits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Entanglement is one of the most fundamental concepts in quantum physics1 and an essential resource for applications in quantum information processing2,3. Both the theory of entanglement4 and the experimental generation of entangled states of light5,6,7,8,9,10 and matter11,12,13 have therefore been a subject of intense research. Of particular importance are multipartite entangled states of photons for their use in quantum communication and network protocols14. Experiments to generate entangled states of light most commonly rely on spontaneous parametric down-conversion sources and heralding5,6,7. The probabilistic nature of such schemes is a major obstacle when scaling to larger systems, which has motivated the study of deterministic sources of entangled photonic states more recently8,9,10. So far, only states within device-specific classes of entanglement have been generated deterministically and with a moderate size as compared to their matter-based counterparts11,13. Achieving more versatility in the generation of entanglement has therefore been an outstanding challenge, which we address in this work.

A generic protocol to generate entangled states as a train of sequentially emitted photons was proposed by Schön et al.15 and is based on a long-lived auxiliary quantum system A, which sequentially interacts with an emitter qubit via a controllable coupling (see Fig. 1a). After each interaction cycle i, the engineered emission into a waveguide converts the state of the emitter qubit into a flying photonic qubit Pi defined by the presence or absence of a single photon in the associated time bin. The combination of controllable interaction and photon emission can be understood as a two-qubit gate realized between A and Pi. Consequently, the photonic state preparation is formally described by repeated unitary operations U applied to A interleaved with two-qubit gates, as represented by the generic quantum circuit shown in Fig. 1b. The range of accessible states crucially depends on the set of available two-qubit gates. Although the GHZ state and the cluster state require a controlled NOT (CNOT) gate only16 and have already been generated experimentally8, the preparation of a W state relies on the ability to perform SWAP(θi) gates with adjustable rotation angle \({\theta }_{i}=2\arcsin \left[{(N-i+1)}^{-0.5}\right]\) (see Fig. 1c). Furthermore, a final SWAP operation is required to disentangle the photonic qubits from the auxiliary system by bringing the latter back to its ground state \(\left|g\right\rangle \), thereby rendering the generation of the final photonic state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle \) fully deterministic.

a An auxiliary quantum system A coupled to an emitter is used to generate a state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle \) of photonic modes Pi. b Quantum circuit using an initialization gate and single-qubit gates U acting on the auxiliary system A, and two-qubit gates (small squares) of the CNOT and SWAP family between the auxiliary qubit and the photons Pi. The last two-qubit gate is always a SWAP (crosses). c Specific gates used for the generation of the cluster state, the GHZ state, and the W state. H: Hadamard gate, 1: Identity gate.

In this work, we realize a superconducting circuit-based source of entangled microwave photons and implement the above protocol with both generic SWAP- and CNOT-type gates to demonstrate deterministic state preparation of cluster, GHZ, and W states. We perform full quantum tomography of states up to four modes and use process tomography to analyze the localizable entanglement in larger photonic states. We infer than entanglement persists over a distance of approximately ten photonic qubits.

Results

Superconducting circuit implementation

We realize the auxiliary system as a transmon (see Fig. 2, red) of which we use the first three energy level \(\left|g\right\rangle \), \(\left|e\right\rangle \), and \(\left|f\right\rangle \) with transition frequencies ωge/2π = 5.758 GHz and ωef/2π = 5.455 GHz (see Supplementary Notes 1 and 2 for details about the device fabrication, the experimental setup, and sample characterization). We perform local unitary operations between the states of the auxiliary qutrit system by applying microwave pulses with controlled amplitude and phase resonant with ωge and ωef, respectively (red arrows in Fig. 2f). To stimulate state-dependent photon emission processes, we tunably couple the auxiliary transmon to a second transmon (blue), acting as the emitter, which is operated at ω01/2π = 5.896 GHz and decays into a semi-infinite transmission line with rate κ/2π = 1.95 MHz. The coupling between the auxiliary system and the emitter is mediated by two parallel channels, one of which is tunable via the magnetic flux applied to a superconducting quantum interference device loop. This specific coupler arrangement (green) allows us to interferometrically cancel the static coupling and protect the auxiliary transmon from Purcell decay into the transmission line while enabling fast decay of the emitter17,18.

a False color optical micrograph of the chip used in the experiment, comprising an auxiliary qutrit (red, b), a tunable coupler (green, c), an emitter qubit (blue, d), an output transmission line (purple) connecting to the measurement chain, a feedline (yellow), a readout circuit with Purcell filter (orange), three flux lines (cyan), and two charge lines (pink). e Equivalent electrical circuit diagram. The auxiliary and the emitter qubits are transmons, with a flux tunable superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) loop capacitively shunted to ground. The coupler consists of two paths, one mainly inductive (top), the other capacitive (bottom). Photons are emitted into the semi-infinite transmission line (TL). f Energy level diagram, indicating the possible transitions induced by single-qubit gates (red), parametric modulation of the coupler (green), and photon emission via spontaneous decay into the TL (purple). g Measured outgoing photon flux \(\left|\langle {a}_{{\rm{out}}}^{\dagger }{a}_{{\rm{out}}}\rangle \right|\) vs. time in the transmission line, in units of inverse emitter linewidth κ, for cluster states of N = 2, . . . , 15 modes. Traces are offset by 0.5 for clarity. Insets: zoom-in by a factor 5 of the last time bin for clarity, and amplitude \(\left|\langle {a}_{{\rm{out}}}\rangle \right|\) in units of κ−1/2, for the cluster state of 15 modes.

By parametrically modulating the applied flux around the value at which the static coupling is canceled, we selectively drive sideband transitions between excitation-number-conserving states (green arrows in Fig. 2f) with a rate Jac/2π ≃ 5 MHz. To perform SWAP(θi) gates between the auxiliary qubit and the emitter qubit, we modulate the flux at the difference frequency Δe0g1/2π = (ω01 − ωge)/2π = 139 MHz driving a transition between the states \(\left|e0\right\rangle \) and \(\left|g1\right\rangle \). The CNOT gate is a photon emission process conditioned on the auxiliary qubit being in its first-excited state. We realize this state-dependent photon generation by first applying a Ry(π) pulse on the e–f transition of the auxiliary qubit and then driving a sideband transition at frequency Δf0e1/2π = (ω01 − ωef)/2π = 441 MHz between the \(\left|f0\right\rangle \) and \(\left|e1\right\rangle \) state. This sequence leaves the auxiliary qubit in the \(\left|e\right\rangle \) state while emitting a photon.

By controlling amplitude, duration, and phase of the pulses, we choose any targeted SWAP and CNOT angle19 (see Supplementary Note 3 for details). Using a continuous set of two-qubit gates20 allows for the generation of a family of entangled states belonging to the class of matrix-product states (MPS) with bond dimension d = 221 of which specific instances are studied in this work.

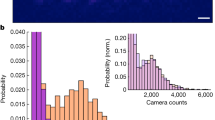

State generation by sequential emission

By applying sequences of the described gates, according to the quantum circuit shown in Fig. 1b, c, we generate many-body states of microwave radiation and experimentally assess their properties through heterodyne measurements of the output field aout in the transmission line (see Supplementary Note 4 for information about the detection method). We first measure the temporal profile of the pulse train by averaging the photon flux \(\left|\langle {a}_{{\rm{out}}}^{\dagger }{a}_{{\rm{out}}}\rangle \right|\) over 106 repetitions of the experiment (see Fig. 2g) for the example of prepared cluster states with up to 15 photonic qubits. Each pulse has an initial rise time of ~π/Jac ≃ 100 ns corresponding to the duration of the two-qubit gate, before exponentially decaying with characteristic timescale κ−1 ≃ 80 ns given by the decay rate of the emitter into the transmission line (see inset). We have chosen a conservative repetition time of T = 900 ns, to ensure that the emitter has fully returned into its ground state before starting the next emission cycle. Each time bin contains an integrated photon flux of ideally half a photon for the cluster state. In comparison to the photon flux, the field expectation value \(\left|\langle {a}_{{\rm{out}}}\rangle \right|\), shown in the inset, is close to zero, as expected for the cluster state. We attribute the small but finite measured \(\left|\langle {a}_{{\rm{out}}}\rangle \right|\) to coherent errors at the 1% level in single-qubit e–f pulses.

Full tomography of states up to four modes

To extract the quantum-mechanical properties of the generated many-body states, we perform quantum state tomography. We reconstruct the density matrix for up to four modes, enabled by advancing the capabilities of our field programmable gate array (FPGA)-based data acquisition (see Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 4 for a detailed discussion of the tomography method). Reconstructing the joint density matrix of four modes is well beyond what has been demonstrated previously for propagating microwave fields, which is full tomography for up to two modes22,23,24. We note that full tomography for even more than four modes is possible by further extending the capacity of data storage on the FPGA or by using offline data processing solutions.

a–c Three- and d–f four-mode state tomography. We plot the real part \({\rm{Re}}(\rho )\) of the most likely density matrices ρ (bars) for a, d the cluster state, b, e the GHZ state, and c, f the W state. Absolute values of the imaginary part (not shown) are all below 0.03. Ideal density matrices ρideal are shown as black wireframes. The fidelity \(F={\rm{Tr}}{\left(\sqrt{\sqrt{\rho }{\rho }_{{\rm{ideal}}}\sqrt{\rho }}\right)}^{2}\) is indicated. Entries are following the binary ordering from (0)000 to (1)111.

We find that the cluster state contains non-vanishing values in all entries of the density matrix, with magnitude close to 2−N, indicating that all basis states are occupied with nearly equal probability. The characteristic pattern of sign changes in some individual terms, which cannot be produced by local Z gates, as there is an imbalance between the number of basis states with positive and negative sign, and renders this state inseparable. For the GHZ state, defined as the equal superposition of the absence or presence of a single photon in each mode \({{\rm{GHZ}}}_{N}=\left({\left|0\right\rangle }^{\otimes N}+{\left|1\right\rangle }^{\otimes N}\right)/\sqrt{2}\), only the four corners of the density matrix have a non-zero value, equal to 0.5. Finally, the W state \({{\rm{W}}}_{N}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{N}{\left|0\right\rangle }^{\otimes (i-1)}\left|{1}_{i}\right\rangle {\left|0\right\rangle }^{\otimes (N-i)}/\sqrt{N}\) is restricted to entries containing exactly one excitation. All non-vanishing entries have ideally the same value of N−1. In all six cases, the experimentally reconstructed density matrices are in very good agreement with the ideally expected ones, which is indicated by the high fidelities FCluster = 0.82 (0.77), FGHZ = 0.90 (0.82), and FW = 0.85 (0.85) for N = 3 (4), with \(F={\rm{Tr}}{\left(\sqrt{\sqrt{\rho }{\rho }_{{\rm{ideal}}}\sqrt{\rho }}\right)}^{2}\), compared to the respective ideal state ρideal. For nearly all prepared states, we observe a higher probability to be in the ground state compared to the ideal case and an overall decrease in the population of states with photons emitted in late time bins. We attribute these effects to the relaxation of the auxiliary qubit during the sequential emission process. Indeed, master equation simulations, taking finite relaxation times \({T}_{1}^{(e)}=21\,\)μs (\({T}_{1}^{(f)}=7\,\)μs) and Ramsey dephasing times \({T}_{2}^{\star (e)}=17\,\)μs (\({T}_{2}^{\star (f)}=8\,\)μs) into account, indicate that the majority of the infidelity originates from the finite coherence of the auxiliary qubit. For the four-mode states, e.g., we simulate fidelities \({F}_{{\rm{Cluster}}}^{{\rm{(MES)}}}=0.87\), \({F}_{{\rm{GHZ}}}^{{\rm{(MES)}}}=0.89\), and \({F}_{{\rm{W}}}^{{\rm{(MES)}}}=0.90\) to the respective ideal state. In general, the W state is affected by decoherence of the first-excited state only and thus pertains a higher fidelity at intermediate mode number N but requires the experimental calibration of more gates. The GHZ state has a higher simulated fidelity at very large mode number N > 10 due to its finite overlap of 0.5 with the vacuum state, whereas the overlap with vacuum scales as 1/N for the cluster state and is 0 for the W state.

Localizable entanglement

To quantify entanglement in the generated many-body states of light, we analyze the localizable entanglement between the first and the last qubit in the chain25 after projecting out all other qubits to obtain the two-qubit density matrix ρD as a function of their distance D = N − 1. As a metric, we choose to report the negativity \({\mathcal{N}}({\rho }_{D})={\sum }_{i}\left|{\lambda }_{i}\right|\), where λi are the negative eigenvalues of the partial transpose of ρD, which is an entanglement monotone for bipartite systems and hence a suited measure of entanglement. For the data points obtained from full tomography (see Fig. 4, filled markers), ρD is calculated from the full density matrix by projecting all qubits but the first and last into their respective ground states in the X- (Z-)basis for the cluster and GHZ (W) states. (The original definition of localizable entanglement averages over all possible outcomes in a given measurement basis. For the W state in particular, localizable entanglement only persists in case the measurement outcome is the ground state for all measured qubits. The resulting estimate for the entanglement length is independent of this particular choice.) The resulting negativities \({{\mathcal{N}}}_{{\rm{Cluster}}}=0.44,0.39,0.31\), \({{\mathcal{N}}}_{{\rm{GHZ}}}=0.42,0.39,0.31\), and \({{\mathcal{N}}}_{{\rm{W}}}=0.41,0.36,0.25\) decrease monotonically with N = 2, 3, 4 (D = 1, 2, 3) as expected and in good agreement with master equation simulations (solid lines) taking the finite coherence of the auxiliary system into account. The deviation between results from full tomography (solid symbols) and partial tomography (open symbols) is likely due to small parameter drifts accumulated during the time in between taking the two different data sets.

Negativity \({\mathcal{N}}\) between the first and (D + 1)-th photonic mode separated by a distance D. Filled dots indicate measurements based on complete tomography, dashed lines are inferred from process maps, empty dots are calculated from partial tomography (see text), and solid lines indicate the coherence limit from master equation simulations. Ideal value of \({\mathcal{N}}\) is 0.5. The cluster state (a, red diamond), GHZ state (b, blue circles), and W state (c, black squares) data are shown. Error bars represent the statistical SD of 0.025 estimated via repeated nominally identical measurements.

Although tomography of the most general N-qubit state requires exponentially growing resources for data acquisition and processing, MPS are fully characterized by the process maps applied in each emission cycle to the auxiliary qubit and the respective photonic mode. To estimate the maximal size of states over which entanglement persists, we thus infer the entanglement length Dent. from measured process maps for the cluster and GHZ states, and from partial tomography for the W state as detailed in the following. We characterize the generated cluster and GHZ states for N > 4 considering the repetitive nature of the underlying photon emission processes. We tomographically measure the process map \(\chi :{\rho }_{A}^{({\rm{pre}})}\to {\rho }_{A,P}^{({\rm{post}})}\) taking a generic input density matrix of the auxiliary qubit \({\rho }_{A}^{({\rm{pre}})}\) to its corresponding output state, while generating an entangled photonic qubit \({\rho }_{A,P}^{({\rm{post}})}\). This measured process map, which we assume to be the same for all N − 1 emission steps, except for the last one, allows us to infer the most likely density matrix within the class of matrix-product density operators with bond dimension d = 28 (see Supplementary Note 5). We determine the negativity between the first and last photonic qubits from the density matrices calculated on the basis of the measured process maps (dashed lines), after projecting out all remaining qubits as before. We find a larger entanglement length Dent.,GHZ ≃ 16 for the GHZ state, compared to the entanglement length Dent.,Cluster ≃ 11 of the cluster state, in agreement with master equation simulations. The negativities obtained from measured process maps follow a similar trend as the ones obtained from master equation simulations, indicating that the experimental performance is mostly limited by decoherence of the auxiliary system, relative to the repetition time T. The slightly lower negativity for the process map approach is likely dominated by coherent errors in the gate operations.

For the W state, each emission step is a SWAP(θi) gate with θi being different in each cycle i. Instead of measuring N different process maps, we opted for an alternative characterization method, by measuring the density matrices ρmix.,i between pairs of the first and the i-th photonic qubit. For an ideal N-qubit W state, we expect these density matrices to satisfy the relation \({\rho }_{i}=N/2\left[{\rho }_{{\rm{mix}}.,i}-(N-2)/N\left|00\right\rangle \left\langle 00\right|\right]\) with \({\rho }_{i}=\left|{{\rm{W}}}_{2}\right\rangle \left\langle {{\rm{W}}}_{2}\right|\) independent of i. The second term on the right originates from tracing out N − 2 photonic qubits. Motivated by these identities, we calculate the experimental ρi based on the measured ρmix.,i using the above relation for the W state of ten photonic modes. We estimate the degree of entanglement between the first and i-th photonic qubit from the negativity of ρi (empty dots). Also in this case, we find good agreement with the simulation results and an entanglement length on the order of ten.

Discussion

As interesting future directions, one could explore applications of the presented source for one-way quantum computing with cluster states6,26,27, Heisenberg-limited metrology, or teleportation with GHZ states28,29,30, or photon loss resilient quantum communication with W states31,32. In addition, this versatile source of quantum many-body states of electromagnetic radiation, able to perform generic gates of the CNOT and SWAP families, could be used to access a larger variety of quantum many-body states in the MPS family, e.g., as ground states of variational quantum algorithms33,34. Finally, we note that our platform naturally allows for integration of additional auxiliary and emitter qubits, suggesting a path to explore entangled tensor network states in higher dimensions35.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this letter and corresponding Supplementary Information file are available online at the ETH Zurich repository for research data https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000429562.

References

Gühne, O. & Tóth, G. Entanglement detection. Phys. Rep. 474, 1–75 (2009).

Kempe, J. Multiparticle entanglement and its applications to cryptography. Phys. Rev. A 60, 910–916 (1999).

Zang, X.-P., Yang, M., Ozaydin, F., Song, W. & Cao, Z.-L. Generating multi-atom entangled W states via light-matter interface based fusion mechanism. Sci. Rep. 5, 16245 (2015).

Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M. & Horodecki, K. Quantum entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 865 (2009).

Eibl, M., Kiesel, N., Bourennane, M., Kurtsiefer, C. & Weinfurter, H. Experimental realization of a three-qubit entangled W state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 077901 (2004).

Walther, P. et al. Experimental one-way quantum computing. Nature 434, 169–176 (2005).

Wang, X.-L. et al. 18-qubit entanglement with six photons’ three degrees of freedom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 260502 (2018).

Schwartz, I. et al. Deterministic generation of a cluster state of entangled photons. Science 354, 434–437 (2016).

Istrati, D. et al. Sequential generation of linear cluster states from a single photon emitter. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.04375 (2019).

Takeda, S., Takase, K. & Furusawa, A. On-demand photonic entanglement synthesizer. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw4530 (2019).

Friis, N. et al. Observation of entangled states of a fully controlled 20-qubit system. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021012 (2018).

Omran, A. et al. Generation and manipulation of Schrödinger cat states in Rydberg atom arrays. Science 365, 570–574 (2019).

Wei, K. X. et al. Verifying multipartite entangled Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger states via multiple quantum coherences. Phys. Rev. A 101, 032343 (2020).

Gisin, N. & Thew, R. Quantum communication. Nat. Photonics 1, 165–171 (2007).

Schön, C., Solano, E., Verstraete, F., Cirac, J. & Wolf, M. Sequential generation of entangled multiqubit states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 110503 (2005).

Lindner, N. H. & Rudolph, T. Proposal for pulsed on-demand sources of photonic cluster state strings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 113602 (2009).

Collodo, M. C. et al. Observation of the crossover from photon ordering to delocalization in tunably coupled resonators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 183601 (2019).

Mundada, P., Zhang, G., Hazard, T. & Houck, A. Suppression of qubit crosstalk in a tunable coupling superconducting circuit. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 054023 (2019).

Abrams, D. M., Didier, N., Johnson, B. R., da Silva, M. P. & Ryan, C. A. Implementation of the XY interaction family with calibration of a single pulse. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.04424 (2019).

Foxen, B. et al. Demonstrating a continuous set of two-qubit gates for near-term quantum algorithms. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08343 (2020).

Cirac, I. In Many-body Physics with Ultracold Gases: Lecture Notes of the Les Houches Summer School Vol. 94, 161–189 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Lang, C. et al. Correlations, indistinguishability and entanglement in Hong-Ou-Mandel experiments at microwave frequencies. Nat. Phys. 9, 345–348 (2013).

Kannan, B. et al. Generating spatially entangled itinerant photons with waveguide quantum electrodynamics. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.07300 (2020).

Ilves, J. et al. On-demand generation and characterization of a microwave time-bin qubit. npj Quantum Inf. 6, 34 (2020).

Verstraete, F., Popp, M. & Cirac, J. I. Entanglement versus correlations in spin systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 027901 (2004).

Raussendorf, R. & Briegel, H. J. A one-way quantum computer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5188–5191 (2001).

Nielsen, M. A. & Dawson, C. M. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with cluster states. Phys. Rev. A 71, 042323 (2005).

Greenberger, D. M., Horne, M. A., Shimony, A. & Zeilinger, A. Bell’s theorem without inequalities. Am. J. Phys. 58, 1131–1143 (1990).

Peniakov, G. et al. Towards supersensitive optical phase measurement using a deterministic source of entangled multiphoton states. Phys. Rev. B 63101, 245406 (2020).

Lee, J. P. et al. A quantum dot as a source of time-bin entangled multi-photon states. Quantum Sci. Technol. 4, 025011 (2019).

Dür, W. Multipartite entanglement that is robust against disposal of particles. Phys. Rev. A 63, 020303 (2001).

Kurpiers, P. et al. Quantum communication with time-bin encoded microwave photons. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 044067 (2019).

Eichler, C. et al. Exploring interacting quantum many-body systems by experimentally creating continuous matrix product states in superconducting circuits. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041044 (2015).

Smith, A., Jobst, B., Green, A. G. & Pollmann, F. Crossing a topological phase transition with a quantum computer. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.05351v2 (2019).

Gimeno-Segovia, M., Rudolph, T. & Economou, S. E. Deterministic generation of large-scale entangled photonic cluster state from interacting solid state emitters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 070501 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Will Oliver and Barath Kannan for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) through the project “Quantum Photonics with Microwaves in Superconducting Circuits”, by the European Research Council (ERC) through the project “Superconducting Quantum Networks” (SuperQuNet), by the National Centre of Competence in Research “Quantum Science and Technology” (NCCR QSIT), a research instrument of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), and by ETH Zurich. J.I.C. acknowledges funding from the ERC Grant QUENOCOBA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-C.B. and K.R. designed the device. J.-C.B., G.N., and M.G. fabricated the device. K.R., P.M., and K.A. programmed the experimental data acquisition device. J.-C.B., K.R., and M.C. prepared the experimental setup. J.-C.B. and K.R. characterized and calibrated the device and the experimental setup. P.M. implemented the qubit reset. J.-C.B., K.R., A. Wulff, L.W., and A.C. carried out the experiments and analyzed the data, with theory support from D.M. and J.I.C. J.-C.B. prepared the figures. J.-C.B. and C.E. wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors. A. Wallraff and C.E. supervised the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Bertrand Reulet and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Besse, JC., Reuer, K., Collodo, M.C. et al. Realizing a deterministic source of multipartite-entangled photonic qubits. Nat Commun 11, 4877 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18635-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18635-x

This article is cited by

-

Deterministic generation of multidimensional photonic cluster states with a single quantum emitter

Nature Physics (2024)

-

Novel multiple access protocols against Q-learning-based tunnel monitoring using flying ad hoc networks

Wireless Networks (2024)

-

Deterministic generation of indistinguishable photons in a cluster state

Nature Photonics (2023)

-

Parity-encoding-based quantum computing with Bayesian error tracking

npj Quantum Information (2023)

-

Photon-number entanglement generated by sequential excitation of a two-level atom

Nature Photonics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.