Abstract

Obtaining genetic variation information from indica rice hybrid parents and identification of loci associated with heterosis are important for hybrid rice breeding. Here, we resequence 1,143 indica accessions mostly selected from the parents of superior hybrid rice cultivars of China, identify genetic variations, and perform kinship analysis. We find different hybrid rice crossing patterns between 3- and 2-line superior hybrid lines. By calculating frequencies of parental variation differences (FPVDs), a more direct approach for studying rice heterosis, we identify loci that are linked to heterosis, which include 98 in superior 3-line hybrids and 36 in superior 2-line hybrids. As a proof of concept, we find two accessions harboring a deletion in OsNramp5, a previously reported gene functioning in cadmium absorption, which can be used to mitigate rice grain cadmium levels through hybrid breeding. Resource of indica rice genetic variation reported in this study will be valuable to geneticists and breeders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Indica (xian) rice, one of the two major subspecies of Asian cultivated rice (Oryza sativa)1, is a staple food for people in many Asian countries. According to a previous study2, indica rice can be divided into two major genetic subgroups: indica I (IndI) and indica II (IndII). Heterosis is the phenomenon in which the first filial generation of two parent lines outperforms its homozygous parents. Taking advantage of heterosis, the commercial breeding of hybrid rice, which started in China in the 1970s and has spread to the other main rice-producing countries in Asia, has greatly secured the food supply in these countries3. Since then, many important indica hybrid parents have been developed. Although there are indica-japonica and japonica-japonica hybrids, the most common rice hybrids are indica-indica hybrids, or indica hybrids for short.

There are two types of indica hybrid rice: 3-line hybrids and 2-line hybrids. The former, which have been commercially available since the 1970s, are generated from crosses between a cytoplasmic male sterile (CMS) line with a sterility gene in the mitochondrial genome and a nonfunctional fertility gene in the nuclear genome, a restorer line (3R) with a functional fertility gene in the nuclear genome that can reverse sterility, and a maintainer line (3M). The 2-line hybrids, which have been commercially available since the 1990s, are generated from a bifunctional line that can behave either as a genic male sterile (GMS) line or a normal line that can reproduce itself (depending upon environmental conditions such as day length and temperature) and a restorer line, which can be either a 2-line restorer (2R) or a 3-line restorer (3R)4,5,6,7,8. It has been thought that a small number of different genes are likely responsible for 3- and 2-line yield heterosis, as based on studies on some indica hybrids9,10.

The first large rice resequencing project, the 3000 Rice Genomes Project in 2014, included many indica rice varieties, but only 322 of them were from China11. Despite other rice resequencing studies, the read lengths were short (between 73 and 90 bp), and the sequencing depth was low (between one- and threefold)2,12. Many important Chinese indica rice accessions, such as Peiai64 (an important germplasm), Quan9311A (a popular CMS), Mianhui146 (a popular 3R), and Shen08S (a popular GMS), were not included in these studies.

To date, almost all rice genomic studies use the japonica Nipponbare genome as the reference genome. However, as reported in the releasing of the genome of indica R498, it is different from that of Nipponbare in many ways13. Thus, it would be more accurate by aligning indica genetic variation reads to the R498 genome rather than the japonica Nipponbare genome. In addition, increasing read length and coverage depth can help to capture accurate and complete genetic variation information for the indica accessions.

In the present study, we select 1143 indica accessions, mostly comprising the major indica accessions used in rice breeding and production in the last 50 years in three different indica-growing environments in China (the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, and southern China), with a particular focus on the parents of superior indica hybrid rice lines. Most of these important accessions have never been resequenced. We identify their genetic variations, using the R498 genome as the reference genome, perform the kinship analysis, and find different hybrid rice crossing patterns in 3- and 2-line superior hybrid lines. Because most-shared parental genetic differences among superior hybrids should be the most relevant to heterosis, we also identify the most-shared single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and indel differences between two parents among all superior hybrids for each type of 3- and 2-line systems, and further identify the different loci associated with heterosis in 3- and 2-line hybrids. We further detect a natural mutation in two accessions that can be used to mitigate cadmium contamination in rice grains.

Results

Resequencing

As detailed in Supplementary Data 1, the 1143 indica accessions in this study included 211 CMS, 110 GMS, 294 3R, and 81 2R accessions (696 in total), representing the parents of the majority of indica hybrid rice accessions that have been widely planted in southern China for almost the last 50 years; some accessions grown internationally were also included. There were also 15 3M, 296 conventional rice (CR), and 136 germplasm rice (GR) accessions that have been used to improve hybrid rice parents and CR accessions. Of the total accessions, 136 were obtained from the International Rice Research Institute and countries other than China (most of which were GM or CR accessions), and the remainder were obtained from China. The raw next-generation sequencing dataset is approximately 3.8 TB and includes 54.7 billion paired-end reads. The average read size is 150 bp (much longer than 87 bp, the average read length for the 3000 Rice Genomes accessions11).

Identification of SNPs and indels

Except for recently published MBKbase14, all major genetic studies on rice to date have used the genome of Nipponbare, a japonica rice (the other major subspecies of cultured Asian rice), as the reference genome1,9,11,15,16,17,18. Because the genome of indica rice R498, which was constructed using recent technologies, is more complete (17 Mb longer) and continuous than that of Nipponbare13, and is the same subspecies as the accessions we studied, we chose the R498 nuclear, mitochondrial, and chloroplast genomes as the reference genomes for this study.

The average mapping rate of the sequencing reads to the R498 nuclear genome was approximately 99.1%. The average genome coverage depth was approximately 17.3× (Supplementary Data 2), slightly greater than the 14× for the average depth for the 3000 Rice Genomes accessions11. SNP and indel identification using the R498 nuclear, mitochondrial, and chloroplast genomes yielded a total of 19.3 million raw SNPs and 2.8 million indels across 1143 accessions, after initial SNP calling. A total of 3.86 million high-quality nuclear SNPs were obtained after filtering with a minor allele frequency greater than 0.01 (Supplementary Table 1 and Methods), and a total of 0.717 million high-quality indels were obtained after filtering (Supplementary Table 2). The nonsynonymous/synonymous substitution ratio for the nuclear SNPs in the CDS regions was 1.55, similar to 1.59 found for indica Guangluai-4 (ref. 19), and slightly higher than the value of 1.46 in the 3000 Rice Genomes Project11, indicating stronger positive selection in indica rice. A total of 452 and 102 high-quality SNPs for the mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes, respectively, were also obtained. The average SNP densities in the nuclear, mitochondrial, and chloroplast genomes were approximately 9.9, 0.86, and 0.76 SNPs/kb, respectively, indicating that the mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes are more conserved than the nuclear genome, which is consistent with previous reports20,21.

Phylogenetic and kinship analyses

First, we performed phylogenetic analysis using the nuclear SNP data and found that most of the CMS, GMS, and GR accessions are grouped into separate clades (Supplementary Fig. 1). Moreover, most 3R and 2R accessions grouped together. However, our results did not show any clear separation between the three indica-growing environments or the different time periods. This likely reflects the history of the development of Chinese indica rice, in which elite accessions were widely shared among rice breeders nationwide and then further modified for improvement in different environments4,5. We also performed phylogenetic analysis using 452 high-quality SNPs from the mitochondrial genome. Most CMS accessions clearly grouped together (Supplementary Fig. 2), as expected from the important role that the mitochondrial genome plays in male sterility in CMS accessions.

In addition to phylogenetic analysis, we performed linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis. The results showed that the CR accessions had the fastest rate of decline, indicating the highest diversity for this group (Supplementary Fig. 3). The GMS and 2R accessions exhibited the slowest rates of decline, indicating the least diversity, probably because the 2-line hybrid system was developed 20 years later than the 3-line hybrid system; thus, there have been fewer parents in the 2-line system. The rates of LD decline are similar to the rates in previous reports15,16.

Because not all accessions that were used to develop these 1143 indica accessions were resequenced and complicated crossbreeding is frequently involved in developing a new line, it is difficult to reconstruct the genealogy of these accessions from genetic variation data. Instead, we performed kinship analysis by calculating kinship coefficients for all pairwise comparisons among the 1143 indica accessions using GEMMA22 (v0.98.1-0). We chose a kinship coefficient cut-off of 0.45 (10% below the first-degree value 0.5, to allow for some errors) and then plotted the relationship data with kinship coefficients greater than the cut-off value (Supplementary Data 3) using Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org/). The results showed 992 accessions with kinship coefficients greater than 0.45, forming 50 multiple-member clusters and 7376 relationships (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 4). The remaining 151 accessions did not display a relationship with a kinship coefficient above the cut-off value. The largest cluster contained 772 accessions, most of which were further divided into eight groups: a restorer group, a CMS group, two GMS groups, two CR groups, and two mixed groups. We found that Minghui63 has close relationships with 98 3R, 12 2R, and 3 CR accessions (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 5). Zhenshan97A, an important CMS accession developed in the 1970s and widely used and shared since, has close relationships with 68 other accessions (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Data 3). These close yet complicated relationships also reflect the complicated rice breeding history in China.

a All kinship relationships with kinship coefficients greater than 0.45. Of 1143 accessions, 992 formed 50 multiple-member clusters and 7376 relationships. The remaining 151 accessions did not have any relationship above the cut-off value and thus are not shown. The largest cluster contains 772 accessions and several subclusters. b Minghui63 and 113 related accessions with kinship coefficients greater than 0.45. In both a and b: circle sizes represent the degree of relationship, i.e., the number of lines connected to each circle; line widths are based on the coefficients between two accessions; circles are in red for conventional rice (CR), yellow for 2-line restorers (2R), green for 2-line photoperiod genic and thermosensitive male sterile (GMS) lines, blue for 3-line cytoplasmic male sterile (CMS) lines, brown for 3-line restorers (3R), purple for 3-line maintainers (3M), and black for germplasm rice (GR). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Population structure and superior hybrid crossing patterns

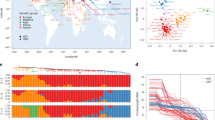

We analyzed the population structure of the 1143 indica accessions using ADMIXTURE23. According to the results (Fig. 2a, K = 2), these accessions can be divided into two genetic groups that closely match the two indica subgroups (IndI and IndII) defined by Xie et al.2, which were determined by comparing to Zhenshan97, a typical IndI accession, and Minghui63, a typical IndII accession (see “Methods”). Among the 1143 accessions, 393 were classified as IndI, and the remaining 750 as IndII. Further analysis of the 211 CMS accessions showed most (186) to be IndI; most (88) of the 110 GMS accessions and most of the 3R, 2R, and GR accessions are IndII (Supplementary Table 3). When we increased K to 6, all accessions were divided into six genetic groups that generally corresponded to GMS lines, restorers (3R + 2R), GR, IndII CR, IndI CR, and CMS lines (Fig. 2a, K = 6), with some exceptions in each group.

a Population structure analysis of 1143 indica accessions. The results for K values from 2 to 6 are shown. When K = 2, two genetic groups match the IndII and IndI subgroups (see “Methods”). When K = 6, the six genetic groups generally correspond to GMS, restorer (3R + 2R), GR, IndII CR, IndI CR, and CMS lines, with some exceptions in each group. b, c Crossing patterns of the superior 3- (b) and 2-line (c) hybrids. The top curves connect two parents of superior hybrids: blue: IndII restorers crossed with IndI male sterile lines; green: IndII restorers crossed with IndII male sterile lines; red: IndI restorers crossed with IndI male sterile lines; yellow: IndII restorers crossed with IndII male sterile lines. A nuclear-genome phylogenetic tree in the horizontal format is shown below the curves in the same color schema as in Fig. 1. d Average nuclear-genome genetic distances between two parents for all 1143 accessions (n = 652,653) and superior 3- (n = 415) and 2-line (n = 136) hybrids (all: min = 0.001, max = 0.491; 3-line: min = 0.194, max = 0.420; 2-line: min = 0.253, max = 0.402). e Average mitochondrial genome genetic distances between two parents for all 1143 accessions (n = 652,653) and superior 3- (n = 415) and 2-line (n = 136) hybrids (all: min = 0.000, max = 0.438; 3-line: min = 0.001, max = 0.315; 2-line: min = 0.003, max = 0.242). In d, e, the p values by two-tailed unpaired Welch’s t-tests are shown on diagrams. Data representation: the middle line: median; the asterisk: mean; the lower and upper hinges: the first and third quartiles; the upper whisker extends from the hinge to the largest value no further than 1.5 × IQR (inter-quartile range) from the hinge. The lower whisker extends from the hinge to the smallest value at most 1.5 × IQR of the hinge. Data beyond the end of the whiskers, which were considered as the outlying points, are plotted individually. Source data underlying figures b–e are provided as a Source Data file.

We also examined parental crossing patterns for each of the superior 3- and 2-line hybrid rice cultivars (Supplementary Data 4). Among 415 superior 3-line hybrids, 382 were found to be crosses between IndII restorers and IndI CMS lines. Among 136 2-line hybrids, 95 are crosses between IndII restorers and IndII GMS lines, and 30 are crosses between IndII restorers and IndI GMS lines (Fig. 2b, c, Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7, and Supplementary Table 4). For 3- or 2-line hybrid rice, crosses using IndI restorers are rare. The superior 3- and 2-line crossing patterns appear to differ; however, the superior 3-line hybrids are more limited to crosses between certain IndII accessions as restorers and certain IndI accessions as CMS lines. Although we identified a few crosses between two parents that are very closely related to each other in both the 3- and 2-line superior hybrids, most crosses were detected as being between two parents in two different or distant clades in the nuclear-genome phylogenetic tree.

Heterosis and genetic distances

Next, we calculated nuclear and mitochondrial genome genetic distances between the two parents of each of the superior indica hybrids in both 3- and 2-line systems. For the nuclear genome, the average genetic distance between the parents for each of the superior 3- and 2-line hybrids (0.345 and 0.334, respectively) was indeed greater than that for all possible combinations of all 1143 accessions (0.306; Fig. 2d). Regarding the mitochondrial genome, the average genetic distance between the parents for each of the superior 3-line hybrids (0.155) was markedly greater than that for all possible combinations of 1143 accessions (0.075). In contrast, the average genetic distance between the parents for each of the superior 2-line hybrid rice lines (0.086) was very similar to that for all possible combinations (Fig. 2e). Although the hybrids only carry maternal mitochondria, these results confirm that the difference in mitochondrial genomes between the two parents for 3-line hybrid rice is important, and that the parents of 2-line hybrid rice do not require such a difference (as the sterility and fertility of GMS lines are both controlled by the nuclear genome).

Identification of loci associated with heterosis

Finding loci involved in rice heterosis is important for improving rice yield. In the last several years, two rice heterosis studies have taken advantage of accurate and cost-effective next-generation sequencing technology. By analyzing computationally delineated parent information from a fixation index (Fst) analysis without separating the 3- and 2-line systems from each other, Huang et al.17 identified 31 highly differentiated loci with a total length of 22.3 Mb between two parental populations. In their new study, Huang et al.9 used another gene identification method—resequencing and genetically mapping very large F2 populations of 17 hybrid rice cultivars at just 0.2× genome coverage —and showed that 3- and 2-line hybrids had a small number of different genes that likely contributed to yield heterosis. Here, the abundance of genetic variation data for many important parents of superior rice hybrids allowed us to take a more direct approach by focusing on the parental genetic differences of superior hybrids. Because our study revealed that superior 3- and 2-line hybrids have different crossing patterns (Fig. 2b, c) and earlier studies also indicated that different genes were involved in the superior 3- and 2-line hybrid rice cultivars9,17, we analyzed the two hybrid systems separately.

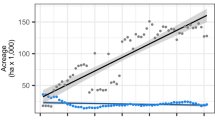

For each of the 415 superior 3-line hybrids, we first compared the variations for each of the 3.86 million high-quality SNPs between two parents. Next, for each SNP position, we obtained the total of hybrids with different parental variations and then calculated the frequencies of parental variation differences (FPVDs) for each SNP in all 415 hybrids and plotted the FPVD values for all SNP positions (Fig. 3a). We did not detect any SNPs or indels with an FPVD of 1 (100%) but did notice that the FPVD values of some SNPs were much higher than those of other SNPs. To help determine an appropriate cut-off value to identify high-FPVD SNPs that are likely associated with heterosis, we simulated inferior hybrids for the 3-line system because either the real inferior hybrids were not well documented by the rice breeders or such information was not available. We used all possible hybrids between the 294 3R and 211 CMS accessions, with the real superior hybrids excluded, as the inferior hybrid set, and then performed FPVD analysis on this set (Fig. 3b). The two highest peaks in the FPVD plot for the 3-line inferior hybrids span two important genes: mads3, a gene on chromosome 1 that regulates late anther development and pollen formation24, and Rf4, a gene on chromosome 10 that restores fertility for WA-type CMS lines25 (Supplementary Table 5). We performed the same analysis on indels for the superior hybrid set and the indel FPVD results were very similar to those of SNPs (Supplementary Fig. 8a).

a Superior 3-line hybrids (n = 415). b Simulated inferior 3-line hybrids (n = 61,619). c Superior 2-line hybrids (n = 136). d Simulated inferior 2-line hybrids (n = 51,114). The inferior 3-line hybrids are the results of simulated crosses between 294 3R and 211 CMS accessions for the 3-line system, with the real superior 3-line hybrids excluded. The inferior 2-line hybrids are the results of simulated crosses between 275 3R + 2R restorers and 110 GMSs, with the real superior 2-line hybrids excluded. Some agronomically important genes located in the loci that we identified are labeled. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As the peak SNP FPVD values located in both the mads3 and Rf4 gene regions were above 0.9, we chose this value as the FPVD cut-off for a superior hybrid FPVD analysis. Using this cut-off value, we found 98 loci that span 3218 SNPs and 539 indels, with a minimum locus length of 100 kb, a maximum length of 11.6 Mb, and a total length of 18.5 Mb (Supplementary Fig. 9a and Supplementary Data 5). These highly differentiated loci are mostly located on chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 7, and 10, with none on chromosome 5. In addition to mads3 and Rf4, these loci span several known genes that control agronomically important traits, such as heading control (hd3a26, Ehd2 (ref. 27) (both were also found by Huang et al.17), and Ehd4 (ref. 28), pleiotropy (Ghd7 (ref. 29), grain number (Gn1a30), panicle initiation (LAX1 (ref. 31), and dwarfism (Sd1 (ref. 32). We also mapped 31 highly differentiated loci discovered by Huang et al.17 to the R498 reference genome and compared them with the loci we found. Seventeen of the 31 loci from Huang’s study partially overlap with 29 of the 98 loci identified in our study, and most overlaps are on chromosomes 1, 2, and 7 (Supplementary Fig. 9a). It is possible that not all 98 loci found in this study contribute to heterosis, and that some loci may be an artifact of the background differences between the parental populations. Nonetheless, the FPVD results from the simulated inferior hybrids indicate that background differences are unlikely to have caused false positives among the 98 loci we identified.

For the 136 superior 2-line hybrids, we performed the same analysis as for the 3-line hybrids. Using the 0.9 FPVD cut-off for the FPVD analysis of the superior 2-line hybrid, we identified 36 loci that span 472 SNPs and 108 indels, with a minimum locus length of 100 kb, a maximum length of 800 kb, and a total length of 5.4 Mb (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 9b, and Supplementary Data 6). Unlike those in the 3-line rice hybrids, these loci are mainly located on chromosomes 2, 4, 7, and 9, and none are located on chromosomes 3, 5, and 6. In addition to tms5, these loci span several known genes that control important agronomic traits, such as OsCOL4 for flowering time33 and OsWRKY71 (ref. 34) and OsHPL2 (ref. 35) for bacterial blight resistance. Indel FPVD analysis showed a very similar pattern (Supplementary Fig. 8b). We also compared the 31 loci found by Huang et al.17 with the loci we found in the 2-line hybrids. However, unlike those of the 3-line hybrids, only 2 of Huang’s 31 loci partially overlapped with 3 of the 36 loci identified in this study (Supplementary Fig. 9b). For the inferior hybrid set for the 2-line system, we used all possible hybrids between all 375 restorers, i.e., both 2R and 3R accessions, and all 110 GMS accessions, with the real superior 2-line hybrids excluded; we then performed FPVD analysis on the inferior hybrids. The highest peak in the SNP FPVD plot for the 2-line inferior hybrids spans tms5, which is responsible for thermosensitive male sterility in the 2-line system36, on chromosome 2 (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Data 7).

To further validate our FPVD results, we performed Fst analysis to compare the parental populations for each of the 3- and 2-line hybrid rice lines. For the 3-line hybrids, there were 380 genes, including Rf4 and mads3, in the selective-sweep regions, mainly located on chromosomes 1, 6, 7, and 10 and with peaks similar to those in our 3-line FPVD study (Supplementary Fig. 10a and Supplementary Data 8). For the 2-line system, there were 359 genes, including tms5, in the selective-sweep regions, which were mainly located on chromosomes 2, 6, and 9 and had peaks at similar locations on chromosomes 2 and 9 as those in our 2-line FPVD study (Supplementary Fig. 10b and Supplementary Data 9). Although our Fst analysis compares two parental populations rather than two specific parents for a superior hybrid, the results largely confirmed our FPVD peak regions for both the superior 3- and 2-line hybrids.

Gene PAV analysis and OsNramp5 deletion mutants

We further performed gene presence/absence variation (PAV) analysis on 434 important loci and genes for all 1143 accessions, and found some genes to be completely absent from some accessions (Supplementary Data 10). One of these genes is OsNramp5, which controls cadmium (Cd) absorption37. Cd contamination in rice grains has become a problem in China and other countries in Asia, mainly due to water and soil contamination38. It has been reported that knockout of OsNramp5 via CRISPR/Cas9 targeting exons 1, 7, and 9 or alteration of OsNramp5 on exon 7 via ethyl methanesulfonate drastically decreases Cd accumulation in rice grains, roots, and shoots, with or without significantly lowering the yield39,40,41,42. Our gene PAV analysis results revealed a 408-kb deletion on chromosome 7 that spans the entire OsNramp5 region in accessions Luohong3A and Luohong4A (Fig. 4a). To confirm the OsNramp5 deletion, we performed PCR using three pairs of primers targeting exons 1, 7–9, and 13 of OsNrapm5 (Fig. 4b), and the results confirmed the absence of this gene from these two accessions (Fig. 4c). Phenotyping experiments also verified that Cd contents in the leaves and roots of Luohong3A and Luohong4A were markedly lower than those in Huazhan (positive control) and were similar to those in Huazhan-OsNramp5 plants, in which OsNramp5 has been knocked out (Fig. 4d).

a Deletion that spans OsNramp5 (marked by the red arrow) in Luohong3A and Luohong4A shown using JBrowse52 (v1.12.3). R93-11, a commonly used 2R, was used as a control to demonstrate no large deletion. b Gene structure of OsNramp5 in Nipponbare showing the location of regions used for PCR: C1 on exon 1, C2 on exons 7 and 9, and C3 on exon 13. c Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products for accessions R93-11 (positive control), Nipponbare (positive control), Luohong3A, and Luohong4A using three pairs of primers targeting the C1, C2, and C3 regions shown in b. The rice actin gene served as the PCR DNA control. The marker sizes (bp) are shown on the left side. Three biological replicates were analyzed for each sample and a representative gel image is shown. d Bar plot for Cd content in leaves (dark) and roots (white) of Huazhan (positive control), Huazhan-OsNramp5 (OsNramp5 knockout39, negative control), Luohong3A, and Luohong4A. Mean values ± s.d. (n = 3) are shown. All individual data points are shown as dots. Source data underlying c and d are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

In this study, we used a variety of techniques to mine the vast genetic variation information for 1143 indica lines. Kinship analysis reveals the complicated many-to-many relationships that characterize the development of rice accessions. Our study also showed that superior 3- and 2-line hybrids have different crossing patterns. Furthermore, we employed a method called FPVD to identify the different loci in 3- and 2-line hybrids that are likely related to heterosis. Through the gene PAV study, we found two accessions with an important deletion that might be used to develop new accessions with low Cd accumulation.

The accession Colomlia links the CMS and GMS subclusters in kinship results, indicating that it was probably used to develop both CMS and GMS lines. Minghui63, a very common and widely used 3R accession that was initially developed in southern China in 1981, has also been widely shared among breeders and yielded hundreds of CR, 3R, and 2R accessions in all three indica-growing environments in China over the last 40 years (www.ricedata.cn), as supported by our kinship analysis results.

Our results showed that superior 3-line hybrids are more limited to crosses between certain IndII accessions as restorers and certain IndI accessions as CMS lines, likely due to the breeding history of how CMS and restorer lines were initially developed as well as the specific genetic interactions that are required between the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes in the 3-line system. The 2-line system is more flexible, as no interaction with the mitochondrial genome is required for sterility; thus, both 2R and 3R restorers can be used as males, though only some hybrids exhibit heterosis.

Because the sterility and fertility genes in simulated inferior hybrid sets for both 3- and 2-line hybrid systems were correctly identified using the FPVD analysis, we are confident that the FPVD method appropriately detected potential loci associated with heterosis. Although previous studies have used Fst to compare two parental populations and to identify loci associated with heterosis17, not all possible hybrids resulting from crosses between the two parental populations are superior; thus Fst analysis might miss loci that are truly associated with heterosis. Using very large F2 populations to identify loci associated with heterosis, as demonstrated in Huang et al.9, requires much resequencing and phenotyping and is thus very laborious and limited to studies on a small number of hybrids. Compared with these two previously published methods, the FPVD method should be simpler to perform and more accurate in detecting potential loci and genes associated with heterosis. Moreover, it should be applicable to other hybrid crops, such as maize, cotton, and pepper (Capsicum), as long as there are enough superior hybrids and the genetic variation information for their parents is known.

It was previously proposed that very few genes may be responsible for the yield heterosis of 3- and 2-line hybrids, but these findings were based on the limited number of superior hybrids9. Conversely our FPVD results are based on 551 superior hybrids and suggest that not only are different loci associated with heterosis in 3- and 2-line systems but that a greater number of loci and genes than previously expected are involved in rice heterosis. Theoretically, other than genes related to sterility and fertility, 3- and 2-line hybrid rice cultivars might share the same set of loci and genes associated with heterosis. The different loci and genes associated with heterosis between superior 3- and 2-line hybrids are probably a result of breeding history and differences in the flexibility of the two hybrid systems. It would be worth integrating the different loci associated with heterosis in the 3- and 2-line hybrids into the same lines to determine whether stronger heterosis can be achieved.

The natural deletion of OsNramp5 found in our study might be valuable in commercial breeding to mitigate the Cd contamination problem in rice-producing countries, as many of these countries require regulatory procedures for gene-edited crops.

Given the large amount of genomic variation information relating to the parents of important hybrid rice lines, many more questions may be answered using this indica dataset, such as what the specific patterns of early, middle, and late hybrid rice crosses are in different environments. We will continue to mine these data to answer these questions. These large resequencing datasets for the 1143 important indica rice accessions and the analysis results, including SNP, indel, and gene PAV data, different crossing patterns, and different loci associated with heterosis in the 3- and 2-line indica hybrid rice, should be useful to both rice researchers and breeders and for both hybrid and CR improvement in the future.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The 1143 indica accessions in this study included 211 CMS, 110 GMS, 294 3R, 81 2R, 15 3M, 296 CR, and 136 GR accessions (Supplementary Data 1). Of the total, 136 accessions were obtained from the International Rice Research Institute and countries other than China (most of which were GM or CR accessions); the remaining accessions were obtained from China. Accessions were planted in a field in Changsha, Hunan, China.

DNA sequencing and SNP calling

For each accession, a single individual was used for genome sequencing. Total DNA was extracted from the leaves of 1-month-old rice plants, and sequencing libraries with an approximately 300-bp insert size were prepared and sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform by Novogene, Beijing, China. Reads containing adaptor sequences or stretches of ambiguous bases and those with low-quality scores were removed from the raw data. Paired-end reads were mapped to the R498 nuclear, mitochondrial, and chloroplast genomes13 with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner43 (BWA, v0.7.8) using the command “BWA mem -t 4 -k 32 –M”. After BWA sorting, the “BWA rmdup” command was used to remove potential PCR duplicates, and only the pairs with the highest mapping quality were retained. After alignment, genomic variants (in genomic variant call format (GVCF) for each accession) were identified with the Haplotype Caller module and the GVCF model using Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) software44 (v3.8). All of the GVCF files were then merged into a single file. A widely accepted method of rice variation filtering (–minGQ 5–maf 0.01–max-missing 0.8–recode–recode-INFO-all) was used, yielding approximately 3.86 million high-quality SNPs and 0.717 million indels1. SNP/indel annotation was performed by mapping SNPs/indels from our dataset onto the gene structures defined by the R498 genome annotation using BEDtools45 (v2.26.0)13.

Phylogenetic and linkage disequilibrium analyses

Pairwise identity-by-state (IBS) genetic distances for SNPs in the 1143 accessions were calculated using PLINK46 (v1.90). The nuclear SNP dataset of 3.86 million high-quality SNPs was employed for nuclear-genome-based phylogenetic analysis, and 452 high-quality mitochondrial SNPs were used for mitochondrial genome-based phylogenetic analysis. The average genetic distance of the entire 1143 accession population was the average of all pairwise distances between accessions. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was then constructed using the R package APE47 (v4.1) with default parameters. Phylogenetic tree graphs were generated using iTOL48. For linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis, PLINK with default parameters was employed to calculate complete and partial LD between each pair of SNPs. We moved 5000-SNP windows along each chromosome. In each window, the LD was estimated between pairs of marker loci plotted against the genetic distance. For every chromosome, we analyzed the values and significance of the squared correlation coefficient (r2) of any LD detected between polymorphic sites (p < 0.05).

Kinship analysis

We calculated kinship coefficients for all pairwise comparisons among the 1143 indica accessions using GEMMA22 (v0.98.1-0) with default parameters and the same nuclear SNP dataset as in the phylogenetic analysis. We chose a cut-off kinship coefficient of 0.45, 10% below the theoretical first-degree value 0.5, to allow for some errors. Network images were generated using Cytoscape (v3.6.0, http://www.cytoscape.org/).

Population structure and subgroup classification

The population structure of the 1143 accessions was determined using the ADMIXTURE23 (v1.3.0) program with default parameters and the same SNP dataset used in the above phylogenetic analysis. To study different genetic groups, we tested K values from 2 to 15 but only show results for K values of 2 to 6. Default settings were used in the analyses. Classification of our accessions into IndI and IndII groups was based on methods used in a previous study2 on two indica accessions: Zhenshan97, a typical IndI accession, and Minghui63, a typical IndII accession. Each accession was classified based on its two subpopulation components: accessions with values that indicated consistency with Zhenshan97 were classified as IndI; those with values that indicated consistency with Minghui63 were classified as IndII.

Genetic distance calculations

To explore genetic distances between the parents of the superior indica hybrids, we calculated the nuclear and mitochondrial genome IBS genetic distances for these parents using PLINK46 (v1.90) with default parameters and high-quality SNP data and then calculated the average genetic distances for the superior 3- and 2-line hybrid rice lines. The average genetic distance for all possible combinations of all 1143 accessions was used as a control. The data were plotted using the box plot tool in R.

Frequency of the parental variation difference analysis

The frequency of the parental variation difference (FPVD) for an SNP is calculated as follows:

where n is the total number of hybrids in a set and dn is the value of the parent variation difference for the nth hybrid: if two parents have the same SNP variation at this SNP position, then dn is 0; if they have different variations, then dn is 1.

We calculated FPVDs for all high-quality SNP positions on all 12 chromosomes in a given hybrid set and then plotted all FPVDs for all SNP positions. We performed FPVD analysis for the superior 3- and 2-line hybrids separately. To construct inferior 3-line hybrids for comparison, we simulated all possible hybrids between 294 3R and 211 CMS accessions, excluded real superior 3-line hybrid rice lines, and used the remaining hybrids as inferior 3-line hybrids. Similarly, we simulated all possible hybrids from crosses between 375 3R + 2R restorer and 110 GMS accessions, excluded real superior 2-line hybrid rice lines, and used the remaining hybrids as inferior 2-line hybrids. For both 3- and 2-line systems, 0.9 was considered the FPVD cut-off. The boundaries for each locus were set as a 100 kb window around the position of an SNP with a 0.9+ FPVD value, and if two adjacent loci overlapped, they were merged into a longer locus. We used BLAST49 (v2.6.0) with parameters “-evalue 1e-200 -perc_identity 95 -max_target_seqs 1” to map 31 highly differentiated loci that were determined by Huang et al.17 to be present in the Nipponbare reference genome to the R498 genome, and the boundaries of some loci were extended somewhat during the mapping due to short insertions in the R498 genome. An indel FPVD analysis was performed in a similar way as for the SNP analysis described above.

Fst analysis

The fixation index (Fst) was estimated to assess the population differentiation of each pair of parents for the 3- and 2-line breeding systems. All genomic regions in 10-kb sliding windows were scanned in 10-kb steps, and regions containing SNPs within the top 1% of the distribution that presented higher differentiation than expected were defined as having stronger signals of selection within the selective-sweep regions.

Gene PAV analysis

The read coverage of all genes in all 1143 samples was calculated using SAMTools depth50 (v1.7) with default parameters. The percentage of gene coverage was calculated using the number of bases in the gene with read coverage greater than 2 divided by the total length of the gene.

PCR

Three pairs of primers, targeting exons 1 (C1), 7–9 (C2), and 13 (C3) of OsNramp5 (Fig. 4b) in the Nipponbare reference genome IRGSP-1.0 (ref. 51) were used for PCR: C1: nrp5-C1f (5′-GTCACTACCACCATTCTCTTC-3′), nrp5-C1r (5′-CTTCATTAGCAGCTGATCATC-3′); C2: nrp5-C2f (5′-ATGCTGGTGTTCGTGATGGC-3′), nrp5-C2r (5′-AGGTGTCGAGGCTGAGGTTGG-3′); and C3: nrp5-C3f (5′-AGTGTTCTCGTGGTTCCTGGGTC-3′), nrp5-C3r (5′-GAGCGGGATGTCGGCCAGGTC-3′). Accessions R93-11 and Nipponbare served as positive PCR primer controls. The rice actin gene was used as a PCR DNA control. The standard PCR procedure was performed as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 4 min, followed by 34 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 20 s, annealing at 57 °C for 20 s, and extension at 72 °C for 20 s, with additional extension for 5 min as the last cycle. The products were examined by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Huazhan-OsNramp5, an OsNramp5 knockout line, was obtained from authors of a previous study39.

Cd concentration measurement

One gram of rice tissue sample was dried at 70 °C for 2 days, ground into a powder, and digested with 25 ml of a 6:1 mixture of HNO3:HClO4 on an electric heating plate at 80 °C for 30 min, 150 °C for 30 min, and then 260 °C until there was no more evaporation. After cooling to room temperature, the residue was dissolved in 1% HNO3. The solution was diluted to 10 ml, and the Cd concentration was determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (SPS3 ICP-720 OES; Agilent Technologies) at 226.502 nm.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. A reporting summary for this Article is available as a Supplementary Information file. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request. All resequencing data have been deposited to NCBI with BioProject ID PRJNA656900. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wang, W. et al. Genomic variation in 3,010 diverse accessions of Asian cultivated rice. Nature 557, 43–49 (2018).

Xie, W. et al. Breeding signatures of rice improvement revealed by a genomic variation map from a large germplasm collection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E5411–E5419 (2015).

Li J. &, Yuan L. Hybrid Rice: Genetics, Breeding and Seed Production (Wiley, 2000).

Lin S. & Yuan L. In Innovative Approaches to Rice Breeding (IRRI, 1980).

Yuan L. in Advances in Hybrid Rice Technology (eds. Virmani, S. S. et al.) (IRRI, 1998).

Guo, J. & Liu, Y. The genetic and molecular basis of cytoplasmic male sterility and fertility restoration in rice. Chin. Sci. Bull. 54, 2404–2409 (2009).

Wang, K. et al. Gene, protein, and network of male sterility in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 92 (2013).

Chen, L. & Liu, Y. G. Male sterility and fertility restoration in crops. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 579–606 (2014).

Huang, X. et al. Genomic architecture of heterosis for yield traits in rice. Nature 537, 629–633 (2016).

Chen, E., Huang, X., Tian, Z., Wing, R. A. & Han, B. The genomics of Oryza species provides insights into rice domestication and heterosis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 70, 639–665 (2019).

Rice Genomes Research. The 3,000 rice genomes project. Gigascience 3, 7 (2014).

Huang, X. et al. Genome-wide association study of flowering time and grain yield traits in a worldwide collection of rice germplasm. Nat. Genet. 44, 32–39 (2011).

Du, H. et al. Sequencing and de novo assembly of a near complete indica rice genome. Nat. Commun. 8, 15324 (2017).

Peng, H. et al. MBKbase for rice: an integrated omics knowledgebase for molecular breeding in rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D1085–D1092 (2020).

McNally, K. L. et al. Genomewide SNP variation reveals relationships among landraces and modern varieties of rice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12273–12278 (2009).

Xu, X. et al. Resequencing 50 accessions of cultivated and wild rice yields markers for identifying agronomically important genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 105–111 (2011).

Huang, X. et al. Genomic analysis of hybrid rice varieties reveals numerous superior alleles that contribute to heterosis. Nat. Commun. 6, 6258 (2015).

Sun, C. et al. RPAN: rice pan-genome browser for ∼3000 rice genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 597–605 (2017).

Srivastava, S. K., Wolinski, P. & Pereira, A. A strategy for genome-wide identification of gene based polymorphisms in rice reveals non-synonymous variation and functional genotypic markers. PLoS ONE 9, e105335 (2014).

Cheng, L., Kim, K. W. & Park, Y. J. Evidence for selection events during domestication by extensive mitochondrial genome analysis between japonica and indica in cultivated rice. Sci. Rep. 9, 10846 (2019).

Tang, J. et al. A comparison of rice chloroplast genomes. Plant Physiol. 135, 412–420 (2004).

Zhou, X. & Stephens, M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat. Genet. 44, 821–824 (2012).

Alexander, D. H., Novembre, J. & Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664 (2009).

Hu, L. et al. Rice MADS3 regulates ROS homeostasis during late anther development. Plant Cell 23, 515–533 (2011).

Tang, H. et al. The rice restorer Rf4 for wild-abortive cytoplasmic male sterility encodes a mitochondrial-localized PPR protein that functions in reduction of WA352 transcripts. Mol. Plant 7, 1497–1500 (2014).

Kojima, S. et al. Hd3a, a rice ortholog of the Arabidopsis FT gene, promotes transition to flowering downstream of Hd1 under short-day conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 1096–1105 (2002).

Matsubara, K. et al. Ehd2, a rice ortholog of the maize INDETERMINATE1 gene, promotes flowering by up-regulating Ehd1. Plant Physiol. 148, 1425–1435 (2008).

Gao, H. et al. Ehd4 encodes a novel and Oryza-genus-specific regulator of photoperiodic flowering in rice. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003281 (2013).

Liu, T., Liu, H., Zhang, H. & Xing, Y. Validation and characterization of Ghd7.1, a major quantitative trait locus with pleiotropic effects on spikelets per panicle, plant height, and heading date in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 55, 917–927 (2013).

Ashikari, M. et al. Cytokinin oxidase regulates rice grain production. Science 309, 741–745 (2005).

Komatsu, K., Maekawa, M., Shimamoto, K. & Kyozuka, J. The LAX1 and FRIZZY PANICLE 2 genes determine the inflorescence architecture of rice by controlling rachis-branch and spikelet development. Dev. Biol. 231, 364–373 (2001).

Spielmeyer, W., Ellis, M. H. & Chandler, P. M. Semidwarf (sd-1), “green revolution” rice, contains a defective gibberellin 20-oxidase gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 9043–9048 (2002).

Lee, Y. S. et al. OsCOL4 is a constitutive flowering repressor upstream of Ehd1 and downstream of OsphyB. Plant J. 63, 18–30 (2010).

Liu, X., Bai, X., Wang, X. & Chu, C. OsWRKY71, a rice transcription factor, is involved in rice defense response. J. Plant Physiol. 164, 969–979 (2007).

Gomi, K. et al. Role of hydroperoxide lyase in white-backed planthopper (Sogatella furcifera Horváth)-induced resistance to bacterial blight in rice, Oryza sativa L. Plant J. 61, 46–57 (2010).

Jia, J.-H., Li, C.-Y., Deng, Q.-Y. & Wang, B. Rapid constructing a genetic linkage map by AFLP technique and mapping a new gene tms5. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 45, 614–620 (2003).

Sasaki, A., Yamaji, N., Yokosho, K. & Ma, J. F. Nramp5 is a major transporter responsible for manganese and cadmium uptake in rice. Plant Cell 24, 2155–2167 (2012).

Hu, Y., Cheng, H. & Tao, S. The challenges and solutions for cadmium-contaminated rice in China: a critical review. Environ. Int. 92-93, 515–532 (2016).

Tang, L. et al. Knockout of OsNramp5 using the CRISPR/Cas9 system produces low Cd-accumulating indica rice without compromising yield. Sci. Rep. 7, 14438 (2017).

Yang, C.-H., Zhang, Y. & Huang, C.-F. Reduction in cadmium accumulation in japonica rice grains by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of OsNRAMP5. J. Integr. Agric. 18, 688–697 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Characterization and evaluation of OsLCT1 and OsNramp5 mutants generated through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis for breeding low Cd rice. Rice Sci. 26, 88–97 (2019).

Cao, Z. Z., Lin, X. Y., Yang, Y. J., Guan, M. Y. & Chen, M. X. Gene identification and transcriptome analysis of low cadmium accumulation rice mutant (lcd1) in response to cadmium stress using MutMap and RNA-seq. BMC Plant Biol. 19, 250 (2019).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Paradis, E., Claude, J. & Strimmer, K. APE: Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20, 289–290 (2004).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W256–W259 (2019).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Kawahara, Y., Bastide, M. D. L., Hamilton, J. P. & Kanamori, H. Improvement of the Oryza sativa Nipponbare reference genome using next generation sequence and optical map data. Rice 6, 1–10 (2013).

Buels, R. et al. JBrowse: a dynamic web platform for genome visualization and analysis. Genome Biol. 17, 66 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the National Key Research and Development Project (2016YFD0101100), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771767 and 31801341), Hunan Science and Technology Major Project (2018NK1010), and Hunan Science and Technology Talent Support Project (2019TJ-Q08). We thank Professor Xinxiong Lu (National Crop Genebank, Institute of Crop Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100081, China) and Professor Xinghua Wei (State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology, China National Rice Research Institute, Hangzhou 310006, China) for providing some rice germplasm resources. We also thank Drs. Jinghua Xiao and Junhua Peng at Huazhi Biotech for beneficial discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. Yuan, L.Y., D.L., and L.Z. co-designed and supervised the research, and wrote the manuscript. Q.L. managed the project. Q.L., W.L., Z.S., N.O., X.J., H.G., G.J., Q.Z., and N.L. performed the bioinformatics work. Q.L., N.O., Q.H., J.W., Jiakui Zheng, Jiatuan Zheng, S.T., R.Z., Y. Tian, M.D., Y. Tan., D. Yu, X. Sheng, X. Sun, L.T., Q.X., B.Z., and Z.H. conducted the field experiments, performed phenotyping, and prepared the samples. Novogene did sequencing and contributed to data analysis. W.L., Q.L., H.L., J. Zhao, and Y.L. prepared figures and tables.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Xuehui Huang, Zhikang Li and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, Q., Li, W., Sun, Z. et al. Resequencing of 1,143 indica rice accessions reveals important genetic variations and different heterosis patterns. Nat Commun 11, 4778 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18608-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18608-0

This article is cited by

-

Natural variation in OsMYB8 confers diurnal floret opening time divergence between indica and japonica subspecies

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Genetic Diversity and Breeding Signatures for Regional Indica Rice Improvement in Guangdong of Southern China

Rice (2023)

-

Whole-genome resequencing reveals genomic footprints of Italian sweet and hot pepper heirlooms giving insight into genes underlying key agronomic and qualitative traits

BMC Genomic Data (2022)

-

Rice functional genomics: decades’ efforts and roads ahead

Science China Life Sciences (2022)

-

Remote estimation of leaf area index (LAI) with unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) imaging for different rice cultivars throughout the entire growing season

Plant Methods (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.