Abstract

The development of noncovalent halogen bonding (XB) catalysis is rapidly gaining traction, as isolated reports documented better performance than the well-established hydrogen bonding thiourea catalysis. However, convincing cases allowing XB activation to be competitive in challenging bond formations are lacking. Herein, we report a robust XB catalyzed 2-deoxyglycosylation, featuring a biomimetic reaction network indicative of dynamic XB activation. Benchmarking studies uncovered an improved substrate tolerance compared to thiourea-catalyzed protocols. Kinetic investigations reveal an autoinductive sigmoidal kinetic profile, supporting an in situ amplification of a XB dependent active catalytic species. Kinetic isotopic effect measurements further support quantum tunneling in the rate determining step. Furthermore, we demonstrate XB catalysis tunability via a halogen swapping strategy, facilitating 2-deoxyribosylations of D-ribals. This protocol showcases the clear emergence of XB catalysis as a versatile activation mode in noncovalent organocatalysis, and as an important addition to the catalytic toolbox of chemical glycosylations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Noncovalent catalysis constitutes one of the major pillars of organocatalysis1,2,3,4, by capitalizing intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonds (HB) to activate specific functional groups under mild conditions. Indisputably, HB catalysis5,6 dominates the majority of noncovalent organocatalyzed protocols, which is largely spearheaded by thiourea catalysis7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Furthermore, thiourea organocatalysis is widely dubbed as biomimetic2, as it derives inspiration from how enzymes capitalize noncovalent interactions to catalyze biochemical reactions1,2,3,4. Hence, biomimetic thiourea catalysis is well recognized as a powerful synthetic tool spanning from asymmetric catalysis to natural product synthesis5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

In contrast, while the utility of the more directional halogen bond (XB) is increasingly establishing its prominence in noncovalent organocatalysis15,16,17,18,19,20,21, mechanistic understanding and utility of unique XB activation modes is highly limited. While nature also exploits XBs in catalytic processes22, for instance in thyroid hormones, the development of biomimetic XB catalytic strategies in constructing biologically important molecules is surprisingly underexplored in the literature.

In recent years, despite the development of excellent proof-of-concept XB-catalyzed reactions by multiple research groups23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, protocols whereby XB catalysis shows clear catalytic advantages in over conventional thiourea catalysis is lacking21. Moreover, a conceivable configurational advantage pertaining to XB catalysis would involve the ease of σ-hole tunability via halogen swapping to accommodate challenging substrates—an advantage not well adoptable in thiourea catalysis due to strict requirements of hydrogen atoms for dual HB activation. This property is however not yet successfully exploited. In addition, the majority of currently reported XB catalytic strategies are limited to monofunctional group activation, such as solely on carbonyls, imines, quinolines, iodonium ylides, or halides15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Biomimetic complex kinetic behavior involving in situ dynamic XB activation on multiple reaction species offers great promise in unraveling unknown XB mechanisms and reactivity, but little is currently known.

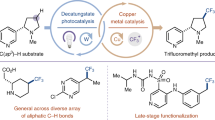

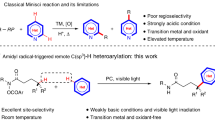

In an elegant seminal benchmarking case, Huber et al. demonstrated a XB-catalyzed Diels–Alder reactions between cyclopentadiene and methyl vinyl ketone (Fig. 1a) through XB-ketone activation27. A comparison of the kinetic profiles between XB and thiourea catalysts illuminated superior XB catalytic performance. An extension of the same activation concept was exemplified by Toy et al., wherein they demonstrated substantially improved effectiveness of a bidentate XB catalyst over thiourea catalysis in a bis-Friedel–Crafts-type reaction of indoles on ketones41.

Furthermore, Takemoto and coworkers showcased in 2017 a powerful cross-enolate coupling reaction catalyzed by a monodentate XB catalyst, which furnished superior yield over thiourea catalysis (Fig. 1b)32. Recent DFT calculations by Wong et al. offer theoretical basis into the potential competitiveness of XB catalysis with respect to thiourea catalysis43. Lately, Yeung and coworkers also reported that XB catalysis enables addition of silylated C-nucleophiles to N-acyliminium ions (Fig. 1c), which was unachievable using thiourea catalysis35. Our group also demonstrated in 2019 that a multistage XB catalysis gave broadly superior anomeric selectivity in strain-release glycosylations44, (Fig. 1d) superceding that of our earlier reported thiourea-catalyzed protocol45. These very limited prior examples provide pressing impetus for more experimental proof and deeper mechanistic understanding of XB catalysis, as a high-performance noncovalent catalytic tool in challenging reactions.

Specifically, we aim to harness and unravel noncovalent mechanisms unique to XB organocatalysis, so that enabling methodologies, which facilitates the preferential construction of challenging bonds over thiourea catalysis in biologically relevant molecules can be developed. In line with this aim, we have identified the biologically relevant 2-deoxyglycosylation as an ideal reaction model for the discovery for unknown XB catalytic mechanisms46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. The unique poly-oxygenated nature of glycosyl substrates and products provides numerous XB acceptor moieties for the in situ catalytic establishment of dynamic noncovalent activations. Moreover, the synthetic importance of 2-deoxyglycosides as a privileged and biologically useful compound class is well exemplified by the continual intense interest by many different research groups46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59, due to its prevalence in glycosidic natural products, such as digitoxin and saccharomicin B (ref. 46).

On the organocatalytic front60,61,62,63,64, seminal studies by Galan and McGarrigle et al. demonstrated the utility of thiourea catalysis in accessing 2-deoxyglycosides via mild organocatalytic conditions47,56. However, significant limitations still exist in such protocols. For instance, the sole application of thiourea catalysis limits the donor scope to galactals47, and expansion to challenging glycosyl donors, such as glucals and rhamnals required harsher conditions, i.e., the usage of either a conventional strong Brønsted acid48, or a judiciously matched combination of thiourea and an appropriate enantiomer of a strong chiral Brønsted acid49. A caveat of directly employing strong Brønsted acid activators lies in the product decomposition due to greatly enhanced hydrolytic cleavage, of up to 2000-fold elevated acid labilities of 2-deoxyglycosides (Supplementary Note 14)65, which necessitates rigorous water exclusion procedures, such as extended pre-vacuum suctioning of substrates47,48,49,56. As the critical mechanistic influence of activators and catalysts in glycosylation pathways is well recognized but largely understudied66, the recent realization of unconventional XB catalytic mechanisms offers huge potential to expand the glycosylation activator toolbox15,16,17,18,19,20,21 and to accommodate improved substrate scopes, while retaining mild conditions required for broad substrate utility and circumventing decomposition.

Furthermore, the applicability of XB activation in advancing chemical glycosylations is still in its infancy. Apart from our above mentioned XB-catalyzed strain-release glycosylation44, Huber and Codée et al. demonstrated a seminal stoichiometric proof-of-principle XB activation in Koenigs–Knorr glycosylation67, and recently Takemoto et al. described a powerful XB-co-catalytic role to elevate the Brønsted acidity in thiourea for N-glycofunctionalizations and N-glycosylations68,69.

We herein report a remarkable XB-catalyzed 2-deoxyglycosylation of glycals 1 (Fig. 1e), featuring robustness, mildness, substrate broadness, and mechanistic complexity via a switchable intricate reaction network. Noncovalent catalytic benchmarking studies are conducted between our protocol and widely established thiourea-catalyzed protocols47,56, and our protocol furnishes overall superior donor and acceptor substrate generality, noteworthily in silylated galactals, glucals, rhamnals, and pentose-derived donors. We introduce a halogen swapping strategy for challenging D-ribal substrates, and this was found to be effective in tolerating challenging 2-deoxypyranoribosylations. In situ NMR monitoring reveal a sigmoidal kinetic profile characteristic of autoinduction, suggesting an amplificative formation of an in situ catalyst. Kinetic isotopic effect (KIE) experiments suggest that quantum tunneling is operative in the proton transfer rate-determining step of the mechanism.

Results

Establishment of an XB-catalyzed 2-deoxyglycosylation

We initiated our investigation on a model glycosylation by selecting the D-glucal substrates 1a–1b as our glycosyl donor, and 2a as the acceptor. Utilizing the benzylated D-glucal 1a (Fig. 2, entry 1–3) was deleterious in our reaction because of substantial formation of Ferrier side products. Encouragingly, when silylated D-glucal 1b (Fig. 2, entry 4) was employed48, we observed a yield elevation of 3a to 92% with excellent anomeric selectivity. A screen of various XB catalysts A–D revealed that A is optimal for our reaction32. We eventually arrived at our optimized protocol (Fig. 2, entry 18), whereby only 3 mol% of catalyst A is required for the glycosylation, furnishing 3a with 89% yield and excellent anomeric selectivity (>20:1).

[a] 2a (0.1 mmol), 1a–b (0.15 mmol), catalyst, 50 °C, solvent (0.2 M), time, argon. [b] Yield and α:β ratio were determined by crude 1H NMR spectra analysis using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard. [c] 40–50% NMR yields of Ferrier rearrangement side-products detected. [d] 92% 1b remaining. [e] 2a (0.2 mmol), 1b (0.30 mmol), catalyst, 50 °C, CH2Cl2 (0.2 M), time, argon. [f] Conducted at 40 °C. [g] Isolated yields. n.d. not determined, iPr isopropyl, TBAB tetrabutylammonium bromide, TBAI tetrabutylammonium iodide.

Control experiments for confirming XB catalysis

To better understand the possible interference effects due to trace acidic HI generation, a series of control experiments were conducted21. While the non-iodinated control catalyst E gave good yields of 3a (Fig. 2, entry 8), the benzimidazolium hydrogen is known to be acidic and could function as either a nonclassical HB or a Brønsted acid catalyst (Supplementary Note 15)70,71, and does not constitute exclusionary proof of XB catalysis by A. To better investigate the criticality of XB catalyst influences on our system, TBAB and TBAI are added into the reaction to inhibit the XB activation mechanism by competition for the σ-hole site, due to the extremely high affinity of halide ions to the XB catalyst (Fig. 2, entries 9 and 10)25,29. Both halide competition experiments gave negligible yield (<5%) of 3a, further augmenting the presence of XB catalysis.

As parallel controls to ascertain TBAB poisoning effects on conventional Brønsted acids without XB influence, the glycosylation was carried out twice in catalytic amounts of HCl (5 mol%), a surrogate for HI, in the absence and presence of the competition reagent TBAB (Fig. 2, entries 11 and 12). The similarly good yields of 3a in both control experiments (80–86% NMR yield) signify that TBAB competition has no effect on fortuitous acid catalysis, further solidifying the cruciality of XB catalysis in our protocol. In control experiments simply reacting A with isopropanol, the absence of O-acceptor substituted benzimidazolium side products in LC–MS and 1H NMR analysis of the reaction mixture further supports the absence of trace acid catalysis (Supplementary Figs. S5–S9 and Supplementary Note 16).

Furthermore, the addition of catalytic amounts of organic base F (Fig. 2, entries 13 and 14), or inorganic base K2CO3 (Fig. 2, entry 15) terminated the glycosylation (<5% yield). This observation is in contrast with our previously reported XB-catalyzed strain-release glycosylation44, whereby the reaction still proceeded with relatively good yields in the presence of base. A control experiment in the absence of catalyst A did not result in reaction (Fig. 2, entry 17). Evaluation of these control experiments revealed a strong dependency on XB catalysis in this protocol. The presence of base deactivation does not necessarily confirm the presence of trace acidity, if XB activation is crucial in initiating a proton transfer step, and the base serves as quencher of the proton transfer. These observations point us toward a possible complex interplay of mechanisms through dynamic XB interactions in our methodology.

Substrate scope

With an optimized protocol in hand, we proceeded to establish the substrate scope of the protocol. We determined that this protocol tolerates a wide range of hexose-based donors 1b–1h, furnishing glycosides 3a–at with good to excellent yields and generally excellent anomeric selectivity (Fig. 3). For the hexoses-based donors 1, natural and nonnatural D- and L-glucal substrates, D- and L-galactal, and L-rhamnal-based substrates are very well tolerated in this methodology. Generally, a range of different O-acceptors bearing the free hydroxyl moiety at multiple positions are very well tolerated to yield the target glycosides 3 with excellent anomeric selectivity. This include the protected monosaccharides acceptors to generate 3a–3j, 3s–3ac, and 3an–3ar. Steroidal acceptors such as cholesterol, testosterone, and methyltestosterone are also well accommodated within the different hexoses donors (3k–3m, 3ad–3ag, and 3as). Interestingly, protected amino acid residues, including L-serine, L-threonine, and L-tyrosine work well in our protocol to generate glycopeptide-type derivatives (3n–3q, 3ah–3aj, and 3at). Simple primary and secondary alcohols, such as propargyl alcohol and isopropanol also gave the target glycosides with generally good to excellent yields, and very good to excellent selectivity (3r and 3ak–3al).

Hexoses donor scope: [a] 2 (0.2 mmol), 1b–1h (0.3 mmol) and 3 mol% catalyst A, in CH2Cl2 (1 mL), argon, 40 °C, 48 h; α:β ratio was determined by crude 1H NMR analysis. [b] 5 mol% catalyst A, 50 °C. [c] 5 mol% catalyst A, 50 °C, 72 h. [d] 5 mol% catalyst A, 50 °C, 108 h. [e] RT, 24 h. [f] 30 °C. [g] 30 °C, 72 h. [h] 30 °C, 24 h. [i] 10 mol% catalyst A, 40 °C, 96 h. [j] 2 (0.2 mmol), 1 f (0.4 mmol) and 5 mol% catalyst A, in CH2Cl2 (1 mL), argon, 30 °C, 48 h. [k] 108 h. [l] 40 °C. [m] 96 h. [n] 50 °C, 72 h. Pentoses donor scope: [aa] 2 (0.2 mmol), 1i–k (0.3 mmol) and 5 mol% catalyst A, in CH2Cl2 (1 mL), argon, 40 °C, 24 h; α:β ratio was determined by crude 1H NMR analysis. [ab] 96 h. [ac] 30 °C, 48 h. [ad] 48 h. [ae] 3 mol% catalyst A, 30 °C, 48 h. [af] 1j (0.4 mmol). [ag] 3 mol% catalyst A, 35 °C, 48 h. [ah] 3 mol% catalyst A, 30 °C. RT = room temperature 23 °C, PG = Protecting Group.

Furthermore, we sought to investigate whether our protocol is robust enough to accommodate less facile pentoses-based donors 1i–1k, which are challenging in thiourea catalysis47,56. Gratifyingly, natural (1i, 1j) and nonnatural pentose-based donors (1k) work generally well in our XB catalysis protocol, to generate the target glycosides (4a–4m) with good to excellent yields and good anomeric selectivity. In the case of the D-xylal substrate 1i (Fig. 3), while there is a clear anomeric preference toward the α-anomer, a diminishment of anomeric selectivity was observed compared to the hexoses, probably due to absence of steric hindrance on the β-face from the C5 substituent. The nonnatural L-xylal was tolerated in the XB catalytic protocol (4i–4k), furnishing anomeric selectivity in the similar range as the natural D-congeners.

We also investigated the use of D-ribal 1j to access the 2-deoxyribose scaffold in 4l–4m. Glycosidic linkages to 2-deoxypyranoribose can be successfully constructed using glycosyl acceptors bearing free primary or secondary alcohol groups, with generally moderate to good yields and excellent anomeric selectivity (Fig. 3).

The overall substrate scope indicated broader donor and acceptor tolerance over established thiourea catalysis, particularly in accessing 2-deoxyglycosides from challenging glucals, rhamnals, and pentose-derived donors. It must be mentioned, however, that thiourea catalysis offers better tolerance on D-galactal donors with ether protecting groups, while XB catalysis is superior when challenging secondary and phenolic acceptors are used on silylated D-galactal donors. Data on benchmarking studies comparing these substrates and protecting group influences against thiourea catalysis will be explored in a later section.

To further ascertain the presence of XB activation on a model glycosyl acceptor 2al, a 13C NMR titration with the addition of increasing quantities of isopropanol 2al to A was conducted (Fig. 4a). A downfield shift of the C–I carbon resonance in A of ~1.9 p.p.m. was observed. The direction of the NMR shift is in accordance with known literature reports of catalytic XB activation27,29,44,68. Fitting of the host–guest titration to a 1:1 isotherm curve yielded an excellent fit with a Ka value of 0.45 M−1 (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. S2 and Supplementary Table S2). The TBAB and TBAI competition experiments were corroborated by 13C NMR resonance shifts of the C–I carbon of catalyst A when an equimolar amount of either TBAB or TBAI was added (Supplementary Figs. S24 and S30)25. In the case of a 1:1 molar ratio of A:TBAB, a downfield shift of 15.45 p.p.m. of the 13C resonance was observed. When a solution of a 1:1 molar ratio of A:TBAI was measured, an analogous downfield 13C resonance shift of 14.34 p.p.m. was observed. The distinctively larger downfield shifts arising from interaction with TBAB and TBAI, compared to the 1:1 adduct formed between catalyst A and isopropanol (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table S2) further support that halides, such as bromide and iodide bind much tighter to catalyst A than isopropanol25. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments between TBAB or TBAI with A yielded Ka values of 7050 and 2210 M−1, respectively (Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4), confirming that halide ion binding to A is of significant orders of magnitude higher than an isopropanol to A interaction, reaffirming the value of halide competition experiments (Fig. 2) in ascertaining XB influences by poisoning the catalyst. A 13C NMR experiment obtained by mixing a 1:1 molar ratio of donor 1c with catalyst A gave an almost negligible 13C NMR shift of the C–I resonance (Supplementary Fig. S36). This supports the hypothesis that noncovalent interactions between the glycosyl donor and A are insignificant in the reaction mechanism38.

Mechanistic investigation by deuterated experiments

For a deeper insight into the mechanism, deuterated experiments (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S44) were conducted. In a first control experiment (Fig. 5, Equation 1), the deuterated 2-propanol-OD 5 was instead used as the acceptor in the XB-catalyzed glycosylation. We observed the formation of both the cis-addition product 6 and the trans-addition product 7 in a ratio of 9.5:1 (6:7).

Deuterated experiments confirming step-wise mechanism through deuterium scrambling and ascertaining source of C2 proton originates from the glycosyl acceptor. Intermolecular competition experiments to understand primary and secondary kinetic isotopic effects (KIEs), and KIE elevation to support quantum tunneling.

In a second confirmatory experiment, a galactal donor 8 with a deuterium label on C2 was synthesized and subjected to the standard XB catalytic conditions with isopropanol (Fig. 5, Equation 2). In this case, we detected the formation of both the cis-addition product 7 and the trans-addition product 6, in a product ratio of 13.5:1 (7:6). The scrambling of the deuterium labels on C2 in both experiments and the appearance of cis- and trans-addition products, suggests that the reaction proceeds through a step-wise reaction, indicating that protonation of the C2 of the glycal from the acceptor –OH proton constitute the first step of the mechanism.

Intermolecular competition experiments using equimolar amounts of isopropanol and deuterated 2-propanol-OD (Fig. 5, Equations 3–4, and Supplementary Figs. S39 and S40) were conducted to determine the presence of primary KIEs. We first conducted two experiments, each terminated at high and low conversions, respectively. In the former, a KIE value of 5.7 is obtained and in the latter, a KIE value of 13.3 is obtained. We postulate that this difference in primary KIE attained under different conversions might be attributed to a mechanistic shift in the overall mechanism as time proceeded, i.e., the initial significance of tunneling in the proton transfer rate-determining step is less pronounced, when a more predominant dynamic acceptor exchange cycle sets in the later part of the reaction (see mechanistic explanation in the later section of the manuscript), which can involve further proton transfer elementary steps. This relatively larger KIE values beyond the semiclassical limit (>9) supports the involvement of quantum tunneling in the rate-determining step72,73,74,75,76,77,78, where the conversion from reactants to products tunnels directly through a kinetic barrier without traversing an energetic maxima.

While such quantum tunneling phenomena were previously known in proton transfer reactions72,73,74,75,76,77,78, as well as in enzymatic catalysis77,79,80, this is hitherto not well understood in the context of noncovalent organocatalysis. A further primary KIE value was determined using a nonpolar solvent mixture of 10:1 PhCH3:CH2Cl2, and a substantial elevation of primary KIE to 23.4 was observed (Fig. 5, Equation 5 and Supplementary Fig. S43). This solvent dependence is in line with previously reported proton transfer reactions involving quantum tunneling81,82, as polar solvents increase the effective mass of the proton via coupling of solvent dipoles, which reduces tunneling and hence decreases the measured KIE.

Furthermore, competition experiments to determine secondary KIE were carried out (Fig. 5, Equations 6–7, and Supplementary Figs. S45 and S46). When equimolar amounts of isopropanol and 9 were used, a secondary KIE value of 1.16 was obtained. In addition, when galactals 1c and 8 were employed in an analogous experiment, a secondary KIE of 0.994 was obtained. The large primary KIEs and the close to unity values attained for secondary KIE experiments strongly support the possibility of OH bond breaking as the rate-determining step.

Mechanistic experiments via in situ NMR spectroscopy

We then undertook an in situ NMR monitoring experiment (Fig. 6) under standard conditions. Surprisingly, the experiment displayed a counter-intuitive sigmoidal kinetic profile83,84,85, differing from saturation kinetics observed our previously reported XB-catalyzed strain-release glycosylation44. Superimposition of the product formation profile of 3al with the depletion profiles of both reactants (Fig. 6a), isopropanol 2al (limiting reagent) and 1c uncovered the symmetrical nature of the product vs substrates profiles. Previous literature precedence corroborate that such a symmetrical profile is indicative of a slow in situ generation of a critical active catalytic intermediate83. Spurred by this finding, we wanted to delineate the mechanistic differences between an XB-catalyzed case with a true strong Brønsted acid catalyst.

Comparing the profile of catalyst A with 3 mol% HCl (Fig. 6b) showed clear divergences. True Brønsted acid catalysis adheres to saturation kinetics, and no induction time was observed. This further indicate that in our XB catalytic method, a mechanistically different route from a true Brønsted acid catalyst is operative. To ascertain the postulate of in situ generation of an active catalytic intermediate during the induction period, we conducted a sequential control experiment. 2al is first reacted with catalyst A at 30 °C for 6 h in the absence of 1c (Fig. 7a), to first generate more of the in situ catalyst in a time period analogous to the induction period. Subsequently, 1c was added with the immediate commencement of NMR monitoring. We observed then the disappearance of the induction period and a significantly accelerated reaction time of ~400 min.

The acceleration arising by conducting the same experiment in sequential order supports the generation of an in situ generated active catalyst from 2al and A (Fig. 7b depicts accelerated kinetic trace with respect to standard conditions)83. The observation of a concave shaped profile indicates continual amplification (active catalyst increasing at an increasing rate) of the in situ catalyst, as the catalytic cycle proceeds upon 1c addition86. In addition, the persistently accelerating kinetic behavior also corroborates that the amount of in situ active catalyst present during the entire experiment is significantly lower than the 3 mol% of A added at the onset. This acceleration is analogous to an ON switching of the catalytic network.

In an orthogonal competition experiment to test if this in situ catalytic species involves XB activation, 2al is first reacted with catalyst A at 30 °C for 6 h (Fig. 7c), followed by the sequential addition of TBAI as an in situ XB catalyst poison and 1c resulted in negligible formation of 3al. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the in situ active catalyst depends crucially on XB participation for catalytic activity.

To investigate if our sigmoidal kinetic at standard condition is representative of an autoinductive or an autocatalytic profile86,87,88, we conducted a control reaction between 1c, 2al, and product 3al as a putative catalyst in the absence of A. This experiment resulted in negligible conversion (<5%, Fig. 7d), and further supports the hypothesis of an autoinductive mechanism over autocatalysis83,86. Unexpectedly, an in situ NMR monitoring experiment adding 20 mol% of product 3al to the standard XB catalytic conditions revealed retardation of catalysis (Fig. 8a). While this observation supports the absence of autocatalytic behavior, it points toward a possible catalyst deactivation by 3al. It is essential to note that addition of 3al at the onset of the reaction enables the direct deactivation of A before the formation of any in situ catalyst in the reaction mixture, hence hampering reaction progression. This retardation effect is analogous to an OFF switching of the catalytic network (Fig. 8b, compared with standard conditions). For a confirmatory test to ascertain XB catalytic influences between 3al and A, an acceptor exchange experiment mixing propargyl alcohol 2r with 3al in the presence of A was conducted (Fig. 8c, Supplementary Figs. S49 and 50, and Supplementary Table S10). The temporal 3ak formation and 3al depletion profiles indicated that a XB-catalyzed transacetalization-type reaction is operative, and displayed saturation kinetics. Moreover, this control experiment is indicative of a steady-state dynamic exchange equilibrium between unreacted acceptor in the reaction and the aglycone component of 3al. Intriguingly, evaluation of all NMR spectra along the time coordinate revealed the detection of only α-glycosides 3al and 3ak. The absence of β-glycosides corroborate an SN1-type exchange mechanism, which involves the cleavage and reformation of the α-glycosidic linkage. A separate control experiment evaluating transacetalization on benzyl protected D-galactal revealed that this dynamic acceptor exchange process is not operative when ether protecting groups are used (Supplementary Fig. S55 and Supplementary Discussion 3).

a Addition of 20 mol% product at the onset retarded XB catalysis. b Comparison of 3al formation kinetics of standard vs conditions in a. c Acceptor exchange experiment to ascertain dynamic acceptor exchange. d Competition experiment with TBAI showed XB catalyst poisoning halted the dynamic acceptor exchange. e 1:1 adduct of catalyst A to 3al revealed a downfield 13C NMR shift.

To test the dependence of this dynamic exchange on XB activation, additional 5 mol% TBAI was added into the acceptor exchange experiment conditions to poison A (Fig. 8d). This experiment failed to generate 3ak, supporting crucial XB catalytic influences in this dynamic equilibration. A 13C NMR experiment mixing a 1:1 ratio of A:3al (Fig. 8e) yielded a 0.158 p.p.m. downfield shift of the 13C C–I resonance of A, evidencing an XB catalytic interaction on the glycosidic bond.

Concentration dependence of the reaction profile

In order to understand the mechanistic role of the glycosyl donor, the glycosyl acceptor and the XB catalyst on the reaction profile, as well as on the induction period, we varied the concentration of each substrate and conducted an in situ 1H NMR monitoring for the reaction between 1c and 2al catalyzed by A.

When the concentration of catalyst A was varied (Fig. 9a), we observed that increase in catalyst loadings resulted in a corresponding decrease in the induction period, and the left shifting of the sigmoidal profile, which is consistent with a positive order with respect to XB catalyst, and is indicative of the participation of the catalyst in the rate-determining step.

When the concentration of the glycosyl donor 1c was varied (Fig. 9b), we observed that the reaction profiles were relatively invariant to the concentration changes and overlapped rather well with each other. The induction periods also remained relatively constant, suggesting that the glycal donor is not involved in the rate-determining step.

Interestingly, when the glycosyl acceptor’s concentration was permutated, a more complex kinetic behavior was observed (Fig. 9c). We observed a positive correlation at lower concentrations, i.e., in the concentration window between 0.1 to 0.2 M, concentration increases resulted in shortening of induction period. However, at larger concentrations beyond the 0.2 M threshold, we observed the onset of a negative correlation where retardation sets in at concentrations from 0.3 to 0.4 M. The observation of a positive order at the lower concentration window suggests the involvement of the glycosyl acceptor in the rate-determining step at standard conditions (0.2 M acceptor).

We speculate that the observed retardation at higher acceptor concentrations beyond the standard conditions could be due to the formation of a more extensive hydrogen-bonded isopropanol network (Fig. 9d), which might inhibit catalyst activity by stabilizing the OH bonds in isopropanol multimeric aggregates89,90, hence hindering the establishment of productive catalyst–glycosyl acceptor XB interactions for catalytic activation.

Proposed intricate XB-modulated network mechanism

Based on the entirety of our mechanistic data, we propose that an intricate reaction network, comprising of multiple dynamic XB catalytic influences is operative in our methodology (Fig. 9d). This mechanistic explanation hinges upon the presence of an off-cycle reservoir of A, which shuttles between an amplificative cycle and a dynamic exchange cycle in response to ON/OFF chemical signals.

The mechanism starts with a slow formation of a critical amount of an in situ catalytic intermediate, which we postulate is the actual catalyst responsible for product amplification. While we made rigorous efforts to detect this intermediate in situ, however, due to minute amounts of this intermediate (presumably much less than the 3 mol% of A inferred from continuous amplification in standard and sequential kinetic studies) beyond the NMR detection limit (5%), we are unable to directly detect and characterize the intermediate.

Despite this, based on holistic analysis of numerous informative indirect experiments, such as in situ sequential experiments, base addition, and poisoning of the in situ generated species by TBAI, we deduced that this intermediate possesses Brønsted acidic characteristics, with concurrent XB catalytic dependency. Significantly, TBAI poisoning characteristics were not observed in control true Brønsted acid-catalyzed experiments, such as HOTf, which performed similarly regardless of the presence or absence of TBAI, hence excluding non-XB effects in our mechanism, such as trace acid catalysis21.

Hence, we propose based on these data that the catalytic intermediate in our protocol is a solvent-separated ion-pair 12, comprising of a solvated XB-stabilized oxyanion–catalyst complex (X−) and a solvated protonated acceptor, arising from the rate-determining proton transfer step, which involves quantum tunneling (Fig. 9, and Supplementary Notes 17 and 18). X− will further serve as an oxocarbenium neutralizing counteranion in subsequent steps. Our experiments ascertaining the presence of acceptor OH bond cleavage (Fig. 5), the crucial involvement of Brønsted acidity (Fig. 2, entries 13–15), and successful TBAI poisoning of the in situ catalyst (Fig. 7c) collectively corroborate the intermediacy of XB-dependent ion-pair 12, as the true in situ catalyst through a proton transfer rate-determining step. This in situ solvent-separated ion-pair hypothesis is also further supported by primary KIE elevation due to increase in the tunneling effect81,82, when the reaction was conducted in a more nonpolar 10:1 PhCH3:CH2Cl2 solvent mixture. This proton transfer arising from the Lewis acidity of the XB donor on the alcoholic glycosyl acceptor is reminiscent of the Lewis acid-assisted Brønsted acid concept proposed by Yamamoto et al.91. In addition, this concept has also been applied by Schmidt et al. in glycosylations using gold complexes or boronates as Lewis acids92,93.

12 can subsequently protonate C2 of glycal 1 to form oxocarbenium intermediate 13. This step-wise mechanism is evidenced by scrambling of deuterium labels originating from the acceptor on C2 (Fig. 5, Equations 1 and 2). As 12 gets consumed in the initial catalytic cycle, the reversible 11 to 12 reaction will be increasingly shifted toward 12 as reaction time progresses, in situ amplifying the active catalyst 12, resulting in an accelerating concave shaped kinetic in the initial phase of the sigmoidal profile (Fig. 7b). Subsequently, the alkoxide in 13 will attack the oxocarbenium species to form 2-deoxyglycoside 3 with the release of A, coupled with a sequential in-cycle intermolecular proton transfer between two molecules of acceptor 2 under the activation of the released catalyst A to regenerate the in situ catalyst 12, analogous to an 11 to 12 conversion. On the other hand, the formation of more glycoside 3 through the amplification cycle (blue circle, Fig. 9d) activates the dynamic exchange mechanism, which siphons off-cycle A, arising from XB interactions with A and the glycosidic bond oxygen in 3 to form 14. This lowering of the off-cycle concentration of A due to the dynamic acceptor exchange will accordingly deplete the concentration of A required to form increasing 12 in the amplificative cycle. This effect is registered by the rate deceleration after the inflection point in the standard sigmoidal kinetic profile (Fig. 6a), but attenuated in the sequential profile (Fig. 7b) due to pre-generation of more 12. However, this effect is strengthened when we directly introduced the glycoside at the onset of the reaction, resulting in retardation (Fig. 8b).

Subsequently, the XB catalytic effect of A in 14 results in a dynamic acceptor exchange evidenced by our acceptor exchange experiment (Fig. 8c), TBAI poisoning, and 13C NMR shift (Fig. 8d, e), which involves firstly cleavage of the newly formed glycosidic linkage in 3 to reform oxocarbenium intermediate 13. Next, a new molecule of 2 will first initiate a proton transfer with the original alkoxide ion in X− to form a new alkoxide, which will attack the oxocarbenium ion to regenerate 3 coupled with the exit of the original protonated alkoxide as 2, releasing catalyst A back into the off-cycle reservoir. Intriguingly, our proposed mechanism seems to constitute a simplified synthetic mimetic of complex noncovalent interactions modulated biochemical mechanisms catalyzed by enzymes, operating in tightly regulated mechanisms. Unexpectedly, we determined that dynamic XB-modulated mechanistic complexity94 could be constructed simply from a ternary chemical mixture comprising of a glycosyl donor, an acceptor, and a XB catalyst.

Benchmarking noncovalent organocatalytic robustness between XB and thiourea catalysis

To evaluate the advances in noncovalent catalyst robustness of benzimidazolium XB catalyst A, and we sought to benchmark our XB catalytic protocol with conventional thioureas47,56,95,96.

In an effort to understand broadness and robustness across glycal donors beyond widely reported galactals, we observed a general superiority trend in using XB catalysis over thiourea on these non-galactal substrates. First, within the hexose family, donors such as silylated D-glucals and L-rhamnals work excellently with catalyst A, but not with 15 and 16. Recognizing the possible caveat that could arise from protecting group influences, we performed the comparative glycosylation also with benzylated glucals and rhamnals. Significantly, literature known ether protecting group preference using thiourea catalysis on 2-deoxygalactosylation47 holds neither for glucosylation nor rhamnosylation.

Second, analogous trends favoring XB over thiourea catalysis can also be observed from the pentose family of glycal donors. Using silylated D-xylal 1i (Fig. 10c), the benchmarking experiments revealed that catalyst A enabled smooth glycosylation, but no reaction was observed with 15 or 16. Using a challenging sterically hindered tertiary alcohol, such as 2af, we noticed that XB catalysis still furnished the desired glycosylation product smoothly, whereas catalysis via 15 or 16 do not generate any observable product. In the case of silylated D-ribal 1j (Fig. 10d), both catalyst A and in particular the brominated version of catalyst A (Br-A in parenthesis) gave superior yields superceding the thiourea congeners. This halogen swapping advantage by XB catalysis will be further discussed in a later section. As a control experiment to clarify specificity of protecting group effects on noncovalent catalysis, we noticed that benzylated xylals and ribals remained lowly reactive, regardless whether thiourea or XB catalysis are employed.

[a] 1H NMR yield determined with 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard. [b] Isolated yields after flash column chromatography. [c] A mixture with inseparable Ferrier-type product impurity was obtained after flash chromatography purification, the yield was calculated by 1H NMR analysis. [d] Reaction time was 48 h, literature gave 68% yield with 2-methyl THF as solvent at 83 °C refluxing temperature. a Benchmarking glucals, b Benchmarking rhamnals, c Benchmarking xylals, d Benchmarking ribals, e Benchmarking reported 2-deoxygalactosylation substrates, f Benchmarking challenging 2-deoxygalactosylation acceptors.

To provide fairer comparison with catalyst 15 and 16, and a more holistic understanding across these noncovalent catalysts, we reproduced the exact conditions reported by Galan and McGarrigle with catalyst A on benzylated galactals, a known strength of these prior methodologies47,56. Our comparative data confirmed that ether protected galactals are better suited for thiourea catalysis, although XB catalysis can also activate benzylated galactals reasonably (Fig. 10e). However, we have demonstrated that employing silyl protecting group in conjunction with XB catalysis gave consistently excellent performance in yields and anomeric selectivity on the galactal donor family (Fig. 3). In cases where more challenging acceptors, such as the phenolic group in protected tyrosine and isopropanol are used, XB catalysis gave clear superiority, while thiourea/thiouracil protocols generated negligible product (Fig. 10f).

In all, we note that XB catalysis offered distinct advantages over thiourea/thiouracil catalysis in activating the entire spectrum of different sugar donors beyond galactals. Pure thiourea catalysis is useful in 2-deoxygalactosylation with ether protecting groups, as previously demonstrated by Galan and McGarrigle et al.47,56,95,96, but reactivity do not scale well across donors, as well as challenging acceptors, and the limitations are evident when other non-galactal glycosyl donors are employed.

These benchmarking experiments reinforce immense value of exploiting XB catalytic protocols as an enhanced organocatalytic tool for accommodating a broader variety of non-galactal glycosyl donors, when conventional thiourea catalytic methods are not optimal.

Applicability of switchable mechanism to elevate yields

To demonstrate further applicability of the XB-dependent “switchable” characteristic, we performed sequential experiments analogous to Fig. 7 in an attempt to elevate yields of representative rhamnosides 3aq and 3at (Fig. 11a) that gave moderate yields in our reaction scope under standard conditions. To our delight, the pre-generation of in situ catalysts had a positive effect in our protocol to substantially improve chemical yields of sluggish substrates.

Tunability of XB catalysis via halogen swapping

Despite the broadly improved performance of catalyst A, we noticed certain limitations of our protocol utilizing the iodide derivative A, particularly in 2-deoxyglycosylation reactions with D-ribals. Meticulous experiments revealed that A is very sensitive to the acceptors employed, furnishing complex mixtures when amino-acid-derived acceptors or more sterically hindered secondary and tertiary alcohol containing steroidal acceptors were employed (Fig. 11b, 4n–4p).

To address this issue, we reasoned that the σ-hole on the iodine atom on A could be fine-tuned by employing an iodine to bromine halogen swapping strategy. Surprisingly, using the bromide derivative Br-A as catalyst showed marked improvement (Fig. 11b) to access such challenging glycosidic linkages in 4n–4p with very good to excellent anomeric selectivity, which were not accessible via A.

Gratifyingly, even 2-deoxyribosylation to 4m gave substantially improved yield (81%) using Br-A. These observations support that postulate that stronger iodide XB donors might be overly strong Lewis acids for sensitive ribal substrates, which resulted in undesired decomposition pathways. As such, tuning XB donor strength by employing the weaker Br-A donor could provide an attenuated, milder catalytic activation route which circumvents decomposition, but increase catalytic performance. This success of our halogen swapping method depicts the power of XB catalysis as a high-performance-tunable noncovalent organocatalytic tool, especially when sensitivity of substrates is pivotal.

Discussion

In conclusion, we demonstrate a robust XB organocatalyzed 2-deoxyglycosylation, operating through an intricately XB catalyst controlled reaction network. This report showcases a marked advancement in noncovalent organocatalysis, where the use of lesser explored XB catalysis resulted in mechanistic divergences, and significantly elevated substrate scope compared to conventional thiourea catalysis, particularly in the formation of challenging glycosidic linkages. Detailed mechanistic studies were also illuminating and instructive of unique and hitherto unknown intricacies and dynamism of XB activation, such as the involvement of quantum tunneling.

In situ temporal kinetic experiments and comparison revealed a sigmoidal kinetic profile characteristic of autoinductive reactions. KIE measurements also revealed unusually high KIE values beyond the semiclassical limit, as well as KIE elevation in nonpolar solvents, which are indicative of quantum tunneling and the formation of an in situ ion-pair intermediate in the rate-determining proton transfer step. Intriguingly, deeper studies unraveled a biomimetic reaction network embedded with switchable ON/OFF mechanism, modulated by dynamic XB interactions between catalyst, substrates, and products. Furthermore, we capitalized on this switchable property, to elevate yields of 2-deoxyrhamnosides through a sequential protocol. We also demonstrate that tuning σ-hole properties via a halogen swap on the catalyst is beneficial in elevating XB catalyst robustness on glycosyl donors, such as D-ribals, particularly when more challenging glycosyl acceptors are employed.

We are optimistic that the development of this protocol has promising wider implications in noncovalent organocatalysis, in deconvoluting differences of mechanism and substrate tolerances between XB and thiourea catalysis, and will contribute to developing mild XB catalysis as a competitive new generational tool in challenging, but biologically relevant bond forming reactions.

Methods

General techniques

Unless otherwise stated, all reactions were set up under inert atmosphere (argon) utilizing glassware that were oven-dried and cooled under argon purging. Silica gel flash column chromatography was performed on deactivated silica gel Merck 60 (particle size 40–63 μm). Starting materials were procured from commercial sources and used without purifications. Solvents were dried according to reported procedures or procured from commercial suppliers. Monitoring of reactions was done using thin layer chromatography (TLC) on Merck silica gel aluminum plates with F254 indicator. TLC visualization of plates was performed under UV light (254 nm) or employing KMnO4 stain or H2SO4-EtOH (10% H2SO4 v/v).

NMR spectra were collected at 300 K on a Bruker DRX400 (400 MHz), Bruker DRX500 (500 MHz), INOVA500 (500 MHz), or Bruker DRX700 (700 MHz) spectrometers, using CDCl3, CD2Cl2, acetone-d6, CD3CN, or benzene-d6 as deuterated solvents. Data for 1H NMR are reported as follows: chemical shift (δ p.p.m.), multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, and br = broad), coupling constant (Hz), NMR spectra were internally referenced to the following residual solvent signals (CDCl3: δ = 7.26 p.p.m. for 1H, δ = 77.16 p.p.m. for 13C; CD2Cl2: δ = 5.32 p.p.m. for 1H, δ = 54.00 p.p.m. for 13C; acetone-d6: δ = 2.05 p.p.m. for 1H, δ = 29.92 p.p.m. for 13C; CD3CN: δ = 1.94 p.p.m. for 1H, δ = 1.32 p.p.m. for 13C of CD3, C6D6: δ = 7.16 p.p.m. for 1H, δ = 128.06 p.p.m. for 13C).

High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on an LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer coupled to an Accela HPLC-System (HPLC column: Hypersyl GOLD, 50 mm×1 mm, particle size 1.9 μm, ionization method: electron spray ionization) and Bruker ultrafleXtreme MALDI-TOF–TOF (three decimal accuracy). Optical rotations were measured in a Schmidt + Haensch Polartronic HH8 polarimeter equipped with a sodium lamp source (589 nm), and are reported as follows: [α]D T °C (c = g/100 mL, solvent). ITC experiments were performed on a MicroCal VP-ITC device.

The anomeric ratio was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy on the crude reaction mixture and the anomeric configuration was determined by 2D NOESY. Chemical yields refer to combined isolated yields of all anomers after flash column chromatography. NMR yields were determined using appropriate internal standards.

General procedure for XB-catalyzed 2-deoxyglycosylation

A mixture of catalyst A (3–10 mol%), glycosyl acceptor 2 (0.2 mmol), and glycal 1 (0.3–0.4 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (1 mL, 0.2 M for 2), and sealed in a dry tube under argon. The mixture was stirred at a specific temperature (room temperature to 50 °C depending on the substrate). Subsequently, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was first analyzed by crude 1H NMR to determine anomeric selectivity and then subjected to flash column chromatography (dry loading) to give the 2-deoxyglycoside 3 or 4.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Knowles, R. R. & Jacobsen, E. N. Attractive noncovalent interactions in asymmetric catalysis: links between enzymes and small molecule catalysts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 20678–20685 (2010).

Marchetti, L. & Levine, M. Biomimetic catalysis. ACS Catal. 1, 1090–1118 (2011).

Wheeler, S. E., Seguin, T. J., Guan, Y. & Doney, A. C. Noncovalent interactions in organocatalysis and the prospect of computational catalysis design. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 1061–1069 (2016).

Mattson, A. E. Tricks for noncovalent catalysis. Science 358, 720 (2017).

Schreiner, P. R. Metal-free organocatalysis through explicit hydrogen bonding interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 32, 289–296 (2003).

Doyle, A. G. & Jacobsen, E. N. Small-molecule H-bond donors in asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Rev. 107, 5713–5743 (2007).

Takemoto, Y. Recognition and activation by ureas and thioureas: stereoselective reactions using ureas and thioureas as hydrogen-bonding donors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 3, 4299–4306 (2005).

Connon, S. J. Organocatalysis mediated by (thio)urea derivatives. Chem. Eur. J. 12, 5418–5427 (2006).

Zhang, Z. & Schreiner, P. R. (Thio)urea organocatalysis-what can be learnt from anion recognition. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1187–1198 (2009).

Takemoto, Y. Development of chiral thiourea catalysts and its application to asymmetric catalytic reactions. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 58, 593–601 (2010).

Serdyuk, O. V., Heckel, C. M. & Tsogoeva, S. B. Bifunctional primary amine-thioureas in asymmetric organocatalysis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 11, 7051–7071 (2013).

Tsakos, M. & Kokotos, C. G. Primary and secondary amine-(thio)ureas and squaramides and their applications in asymmetric organocatalysis. Tetrahedron 69, 10199–10222 (2013).

Nishikawa, Y. Recent topics in dual hydrogen bonding catalysis. Tetrahedron Lett. 59, 216–223 (2018).

Odagi, M. & Nagasawa, K. Recent advances in natural products synthesis using bifunctional organocatalysts bearing a hydrogen-bonding donor moiety. Asian J. Org. Chem. 8, 1766–1774 (2019).

Beale, T. M., Chudzinski, M. G., Sarwar, M. G. & Taylor, M. S. Halogen bonding in solution: thermodynamics and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 1667–1680 (2013).

Cavallo, G. et al. The halogen bond. Chem. Rev. 116, 2478–2601 (2016).

Bulfield, D. & Huber, S. M. Halogen bonding in organic synthesis and organocatalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 14434–14450 (2016).

Breugst, M., von der Heiden, D. & Schmauck, J. Novel noncovalent interactions in catalysis: a focus on halogen, chalcogen, and anion-π bonding. Synthesis 49, 3224–3236 (2017).

Zhao, Y., Cotelle, Y., Sakai, N. & Matile, S. Unorthodox interactions at work. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 4270–4277 (2016).

Tepper, R. & Schubert, U. S. Halogen bonding in solution: anion recognition, templated self-assembly, and organocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6004–6016 (2018).

Sutar, R. L. & Huber, S. M. Catalysis of organic reactions through halogen bonding. ACS Catal. 9, 9622–9639 (2019).

Scholfield, M. R., Vander Zanden, C. M., Carter, M. & Ho, P. S. Halogen bonding (X-Bonding): a biological perspective. Protein Sci. 22, 139–152 (2013).

Bruckmann, A., Pena, M. A. & Bolm, C. Organocatalysis through halogen-bond activation. Synlett 6, 900–902 (2008).

Coulembier, O., Meyer, F. & Dubois, P. Controlled room temperature ROP of L-lactide by ICl3: a simple halogen-bonding catalyst. Polym. Chem. 1, 434–437 (2010).

Walter, S. M., Kniep, F., Herdtweck, E. & Huber, S. M. Halogen-bond-induced activation of a carbon-heteroatom bond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7187–7191 (2011).

Kniep, F. et al. Organocatalysis by neutral multidentate halogen-bond donors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 7028–7032 (2013).

Jungbauer, S. H. et al. Activation of a carbonyl compound by halogen bonding. Chem. Commun. 50, 6281–6284 (2010).

He, W., Ge, Y.-C. & Tan, C.-H. Halogen-bonding-induced hydrogen transfer to C=N bond with Hantzsch ester. Org. Lett. 16, 3244–3247 (2014).

Jungbauer, S. & Huber, S. M. Cationic Multidentate halogen-bond donors in halide abstraction organocatalysis: catalyst optimization by preorganization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12110–12120 (2015).

Takeda, Y., Hisakuni, D., Lin, C.-H. & Minikata, S. 2-Halogenoimidazolium salt catalyzed aza-diels-alder reaction through halogen-bond formation. Org. Lett. 17, 318–321 (2015).

Saito, M., Tsuji, N., Kobayashi, Y. & Takemoto, Y. Direct dehydroxylative coupling reaction of alcohols with organosilanes through Si-X bond activation by halogen bonding. Org. Lett. 17, 318–321 (2015).

Saito, M., Kobayashi, Y., Tsuzuki, S. & Takemoto, Y. Electrophilic activation of iodonium ylides by halogen-bond-donor catalysis for cross-enolate coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 7653–7657 (2017).

Chan, Y.-C. & Yeung, Y.-Y. Halogen bond catalyzed bromocarbocyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3483–3487 (2018).

Benz, S., Poblador-Bahamonde, A., Low-Ders, N. & Matile, S. Cataysis with pnictogen, chalcogen, and halogen bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 5408–5412 (2018).

Chan, Y.-C. & Yeung, Y.-Y. Halogen-bond-catalyzed addition of carbon-based nucleophiles to N-acylimminium ions. Org. Lett. 21, 5665–5669 (2019).

Kuwano, S., Suzuki, T., Hosaka, Y. & Arai, T. A chiral organic base catalyst with halogen-bonding-donor functionality: asymmetric mannich reactions of malononitrile with N-Boc aldimines and ketimines. Chem. Commun. 54, 3847–3850 (2018).

Heinen, F., Engelage, E., Dreger, A., Weiss, R. & Huber, S. M. Iodine(III) derivatives as halogen bonding organocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3830–3833 (2018).

Kuwano, S., Suzuki, T., Yamanaka, M., Tsutsumi, R. & Arai, T. Catalysis based on C-I…π halogen bonds: electrophilic activation of 2-alkenylindoles by cationic halogen-bond donor for [4+2] cycloadditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 10220–10224 (2019).

Guillier, K. et al. A halogen-bond donor catalyst for templated macrocyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 14940–14943 (2019).

Dreger, A. et al. A halogen-bonding-catalysed nazarov cyclisation reaction. Chem. Commun. 55, 8262–8265 (2019).

Liu, X., Ma, S. & Toy, P. H. Halogen bond-catalyzed Friedel-Crafts reactions of aldehydes and ketones using a bidentate halogen bond donor catalyst: synthesis of symmetrical bis(indolyl)methanes. Org. Lett. 21, 9212–9216 (2019).

Kaasik, M. et al. Halo-1,2,3-triazolium salts as halogen bond donors for the activation of imines in dihydropyridinone synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 84, 4294–4303 (2019).

Kee, C. W. & Wong, M. W. In silico design of halogen-bonding-based organocatalyst for Diels-Alder reaction, claisen rearrangement, and cope-type hydroamination. J. Org. Chem. 81, 7459–7470 (2016).

Xu, C. & Loh, C. C. J. A multi-stage halogen bond catalyzed strain-release glycosylation unravels new hedgehog signaling inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5381–5391 (2019).

Xu, C. & Loh, C. C. J. An ultra-low thiourea catalyzed strain-release glycosylation and a multicatalytic diversification strategy. Nat. Commun. 9, 4057 (2018).

Bennett, C. S. & Galan, M. C. Methods for 2-deoxyglycoside synthesis. Chem. Rev. 118, 7931–7985 (2018).

Balmond, E. I., Coe, D. M., Galan, M. C. & McGarrigle, E. M. α-Selective organocatalytic synthesis of 2-deoxygalactosides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 9152–9155 (2012).

Balmond, E. I. et al. A 3,4-trans-fused cyclic protecting group facilitates α-selective catalytic synthesis of 2-deoxyglycosides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 8190–8194 (2014).

Palo-Nieto, C., Sau, A., Williams, R. & Galan, M. C. Cooperative Brønsted acid-type organocatalysis fort the stereoselective synthesis of deoxyglycosides. J. Org. Chem. 82, 407–414 (2017).

Sau, A. et al. Palladium-catalyzed direct stereoselective synthesis of deoxyglycosides from glycals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 3640–3644 (2017).

Palo-Nieto, C., Sau, A. & Galan, M. C. Gold(I)-catalyzed directed stereoselective synthesis of deoxyglycosides from glycals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 14041–14044 (2017).

Das, S., Pekel, D., Neudörfl, J.-M. & Berkessel, A. Organocatalytic glycosylation by using electron-deficient pyridinium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 12479–12483 (2015).

Zhao, G. & Wang, T. Stereoselective synthesis of 2-deoxyglycosides from glycals by visible-light-induced photoacid catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6120–6124 (2018).

Sherry, B. D., Loy, R. N. & Toste, F. D. Rhenium(V)-catalyzed synthesis of 2-deoxy-α-glycosides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 4510–4511 (2004).

Ghosh, T., Mukherji, A. & Kancharla, P. K. Sterically hindered 2,4,6-Tri-tert-butylpyridinium salts as single hydrogen bond donors for highly steroselective glycosylation reactions of glycals. Org. Lett. 21, 3490–3495 (2019).

Bradshaw, G. A. et al. Stereoselective organocatalyzed glycosylations-thiouracil, thioureas and monothophthalimide act as Brønsted acid catalysts at low loadings. Chem. Sci. 10, 508–514 (2019).

Nakatsuji, Y., Kobayashi, Y. & Takemoto, Y. Direct addition of amides to glycals enabled by solvation-insusceptible 2-haloazolium salt catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 14115–14119 (2019).

Palo-Nieto, C. et al. Copper reactivity can be tuned to catalyze the stereoselective synthesis of 2-deoxyglycosides from glycals. Org. Lett. 22, 1991–1996 (2020).

Liu, M. et al. Stereoselective electro-2-deoxyglycosylation from glycals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 15204–15208 (2020).

Williams, R. & Galan, M. C. Recent advances in organocatalytic glycosylations. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 6247–6264 (2017).

Park, Y. et al. Macrocyclic bis-thioureas catalyze stereospecific glycosylation reactions. Science 355, 162–166 (2017).

Levi, S. M., Li, Q., Rötheli, A. & Jacobsen, E. N. Catalytic activation of glycosyl phosphates for stereoselective coupling reactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 35–39 (2019).

Mayfield, A. B., Metternich, Trotta, A. H. & Jacobsen, E. N. Stereospecific furanosylations catalyzed by bis-thiourea hydrogen bond donors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 4061–4069 (2020).

Li, Q., Levi, S. M. & Jacobsen, E. N. Highly stereoselective β-mannosylations and β-rhamnosylations catalyzed by bis-thiourea. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11865–11872 (2020).

Overend, W. G., Rees, C. W. & Sequeira, J. S. Reactions at position 1 of carbohydrates. Part III. The acid-catalysed hydrolysis of glycosides. J. Chem. Soc. 3429–3440 (1962).

Ranade, S. C. & Demchenko, A. V. Mechanism of chemical glycosylation: focus on the mode of activation and departure of anomeric leaving groups. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 32, 1–43 (2013).

Castelli, R. et al. Activation of glycosyl halides by halogen bonding. Chem. Asian J. 9, 2095–2098 (2014).

Kobayashi, Y., Nakatsuji, Y., Li, S., Tsuzuki, S. & Takemoto, Y. Direct N-glycofunctionalization of amides with glycosyl trichloroacetimidate by thiourea/halogen bond donor co-catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3646–3650 (2018).

Li, S., Kobayashi, Y. & Takemoto, Y. Organocatalytic direct α-selective N-glycosylation of amide with glycosyl trichloroacetimiate. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 66, 768–770 (2018).

Mumcu, A. & Küçükbay, H. Determination of pKa values of some novel benzimidazole salts by using a new approach with 1H NMR spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Chem. 53, 1024–1030 (2015).

Dunn, M. H., Konstandaras, N., Cole, M. L. & Harper, J. B. Targeted and systematic approach to the study of pKa values of imidazolium salts in dimethyl sulfoxide. J. Org. Chem. 82, 7324–7331 (2017).

Bell, R. P. The Tunnel Effect in Chemistry (University Press, Cambridge, 1980).

Kwart, H. Temperature dependence of the primary kinetic isotopic effect as a mechanistic criterion. Acc. Chem. Res. 15, 401–408 (1982).

Schreiner, P. R. Tunneling control of chemical reactions: the third reactivity paradigm. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 15276–15283 (2017).

Ley, D., Gerbig, D. & Schreiner, P. R. Tunneling control of chemical reactions – the organic chemist’s perspective. Org. Biomol. Chem. 10, 3781–3790 (2012).

Meisner, J. & Kästner, J. Atom tunneling in chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 5400–5413 (2016).

Nagel, Z. D. & Klinman, J. P. Tunneling and dynamics in enzymatic hydride transfer. Chem. Rev. 106, 3095–3118 (2006).

More O’ Ferrall, R. A. A pictorial representation of zero-point energy and tunneling contributions to the kinetic isotopic effect. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 23, 572–579 (2010).

Reyes, A. C., Amyes, T. L. & Richard, J. P. Primary deuterium kinetic isotope effects: a probe for the origin of the rate acceleration for hydride transfer catalyzed by glyerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 57, 4338–4348 (2018).

Truhlar, D. G. et al. The incorporation of quantum effects in enyzme kinetics modeling. Acc. Chem. Res. 35, 341–349 (2002).

Caldin, E. F. & Mateo, S. Kinetic isotope effects in various solvents for the proton-transfer reactions of 4-nitrophenylnitromethane with bases. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. Issue 22, 854–855 (1973).

Caldin, E. F. & Mateo, S. Kinetic isotope effects and tunnelling in the proton-transfer reaction between 4-nitrophenylnitromethane and tetramethylguanidine in various aprotic solvents. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1 71, 1876–1904 (1975).

Mower, M. P. & Blackmond, D. G. Mechanistic rationalization of unusual sigmoidal kinetic profiles in the Machetti-De Sarlo cycloaddition reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 2386–2391 (2015).

Sharma, K. et al. Cation-controlled enantio-and diastereoselective synthesis of indolines: an autoinductive phase-transfer initiated 5-endo-trig process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 13414–13424 (2015).

Keske, E. C., West, T. H. & Lloyd-Jones, G. C. Analysis of autoinduction, inhibition and auto-inhibition in a Rh-catalyzed C-C cleavage: mechanism of decyanative aryl-silylation. ACS Catal. 8, 8932–8940 (2018).

Blackmond, D. An examination of the role of autocatalytic cycles in the chemistry of proposed primordial reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 386–390 (2009).

Bissette, A. J. & Fletcher, S. P. Mechanisms of autocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 12800–12826 (2013).

Plasson, R., Brandenburg, A., Jullien, L. & Bersini, H. Autocatalyses. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 8073–8085 (2011).

Kononov, L. O. Chemical reactivity and solution structure: on the way to a paradigm shift? RSC Adv. 5, 46718–46734 (2015).

Kononov, L. O. et al. Concentration dependence on glycosylation outcomes: a clue to reproducibility and understanding the reasons behind. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 1926–1934 (2012).

Yamamoto, H. & Futatsugi, K. “Designer acids”: combined acid catalysis for asymmetric synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 1924–1942 (2005).

Peng, P. & Schmidt, R. R. An alternative reaction course in O-glycosidation with O-glycosyl trichloroacetimidates as glycosyl donors and Lewis acidic metal salts as catalyst: acid-base catalysis with gold chloride-glycosyl acceptor adducts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12653–12659 (2015).

Kumar, A., Kumar, V., Dere, R. T. & Schmidt, R. R. Glycoside bond formation via acid-base catalysis. Org. Lett. 13, 3612–3615 (2011).

Whitesides, G. M. & Ismagilov, R. F. Complexity in chemistry. Science 284, 89–92 (1999).

Schreiner, P. R. & Wittkopp, A. H-bonding additives act like Lewis acid catalysts. Org. Lett. 4, 217–220 (2002).

Kotke, M. & Schreiner, P. R. Generally applicable organocatalytic tetrahydropyranylation of hydroxy functionalities with very low catalyst loading. Synthesis Issue 5, 779–790 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Fonds der Chemischen Industrie for generous funding to C.C.J.L. through a Liebig fellowship. Prof. Herbert Waldmann is greatly acknowledged for his generous assistance and infrastructural support. C.X. acknowledges the Max Planck Society for postdoctoral funding and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for a postdoctoral fellowship. V.U.B.R. acknowledges the Max Planck Society for postdoctoral funding. We are grateful for infrastructural support from the Technical University of Dortmund and the Max Planck Institut für Molekulare Physiologie, Dortmund. Robert Lott is acknowledged for initial preliminary contributions to the project. Dr. Raphael Gasper-Schoenenbruecher of the Central Unit for Crystallography and Biophysics of the Max Planck Institut für Molekulare Physiologie is gratefully acknowledged for the ITC expertise and assistance. Jens Warmer is gratefully acknowledged for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry assistance. Bernhard Griewel is gratefully acknowledged for NMR expertise and generous assistance in the in situ NMR monitoring experiments. The NMR department of the faculty of Chemistry and Chemical Biology of the Technical University of Dortmund is gratefully acknowledged for providing NMR timeslots for the NMR monitoring experiments.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C.J.L. conceived the idea and supervised the project. C.X. and V.U.B.R. conducted the majority of the experimental work. C.C.J.L, C.X., and V.U.B.R. prepared this manuscript. C.C.J.L., C.X., V.U.B.R., and J.W. contributed to data analysis and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, C., Rao, V.U.B., Weigen, J. et al. A robust and tunable halogen bond organocatalyzed 2-deoxyglycosylation involving quantum tunneling. Nat Commun 11, 4911 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18595-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18595-2

This article is cited by

-

A synergistic Rh(I)/organoboron-catalysed site-selective carbohydrate functionalization that involves multiple stereocontrol

Nature Chemistry (2023)

-

Halogen-bond-assisted radical activation of glycosyl donors enables mild and stereoconvergent 1,2-cis-glycosylation

Nature Chemistry (2022)

-

Exploiting non-covalent interactions in selective carbohydrate synthesis

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.