Abstract

Observation of molecular dynamics with quantum state resolution is one of the major challenges in chemical physics. Complete characterization of collision dynamics leads to the microscopic understanding and unraveling of different quantum phenomena such as scattering resonances. Here we present an experimental approach for observing molecular dynamics involving neutral particles and ions that is capable of providing state-to-state mapping of the dynamics. We use Penning ionization reaction between argon and metastable helium to generate argon ion and ground state helium atom pairs at separation of several angstroms. The energy of an ejected electron carries the information about the initial electronic state of an ion. The coincidence detection of ionic products provides a state resolved description of the post-ionization ion-neutral dynamics. We demonstrate that correlation between the electron and ion energy spectra enables us to directly observe the spin-orbit excited Feshbach resonance state of HeAr+. We measure the lifetime of the quasi-bound HeAr+ A2 state and discuss possible applications of our method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The outcome of atomic and molecular collisions is governed by the details of the intermolecular interactions. In some cases, these can be accurately predicted and calculated by state-of-the-art quantum theory. In other instances, experiments serve as a direct probe of interactions. Starting with the pioneering work of Lee and Herschbach1, gas phase collisions using adiabatically cooled molecular beams have become a central tool in chemical physics, allowing one to prepare reactants with a well-defined quantum state and collision energy2. A complete state resolved detection of all reaction products, however is difficult in current experiments. Only recently Gao et al.3 reported a fully resolved detection of rotational excitation in bimolecular collisions. The latest advances in molecular beams studies now enable performing precise experiments reaching collision energies as low as 10 mK, and the observation of different quantum phenomena such as scattering resonances4, the quantum isotope effect5, stereodynamics of chemi-ionization reaction6, and the prominent effect of the internal molecular structure on dynamics at low collision energies7,8.

Collisions are not the only option for observing molecular dynamics. A molecule can be excited into a nonstationary state in femtosecond transition-state spectroscopy where dynamical information can be recovered from a time-resolved spectroscopy of dissociation fragments9. A nonstationary state can also be reached by a sudden quench of a system onto a lower electronic energy manifold. For example, slow photoelectron velocity-map imaging10 has been used to detect Feshbach resonances in the F + H2 reaction by measuring the photoelectron energy spectrum of the photodetachment of the FH\({}_{2}^{-}\) molecular anion11.

Here, we present an experimental approach where ionization induced by collision between excited noble gas and a neutral particle is used to initiate dynamics between ions and noble gas atoms. We show that such a method is capable of quantum state-to-state resolution. Other experimental approaches for probing ion-neutral dynamics include crossed beam studies of a neutral and ionic beams12,13, collisions within the orbit of the Rydberg electron14,15, and the co-trapping of ions and atoms16. During Penning ionization (PI) reaction, sudden ionization of the neutral system takes place with the ejected electron serving as an indicator of the initial ionic quantum state17. Following the interaction with the noble gas atom, Penning ions carry information about the final distribution of states. Therefore, the correlation between energy distributions of Penning electrons and Penning ions serves as a state-to-state mapping of the postionization ion-neutral dynamics.

A crucial part in our experiment is the coincidence detection of the momenta of PI charged products. This allows us to detect ion–electron pairs that originate from the same collision event. Coincidence detection of ionization fragments enabled many groundbreaking experiments including observation of the Efimov state of He trimer18, determination of chirality of molecules19, and other experiments providing the insight the dynamic of photoionization20,21,22,23. Many experiments reported separate measurement of electron and ion energy spectrum for several PI systems17,24. However, without the correlation, electron energy provides information only about the initial state of the PI ion. As such, it is similar to photoionization spectra and does not necessarily carry additional information. In contrast, the ion energy spectrum does provide information about nuclear dynamics; however, it is always averaged over many initial states that are occupied during the PI process. The correlation is critical in resolving nuclear dynamics for a single initial state. Interestingly, this allows us to achieve quantum state-to-state resolution without any initial state preparation step that requires single quantum level control.

As a first application of our method, we demonstrate a direct detection of Feshbach HeAr+ molecule that dissociates on a microsecond timescale due to the spin–orbit coupling. In future, we plan to apply this method to investigate post-PI nuclear dynamics between vibrationally excited H\({}_{2}^{+}\) molecular ion and helium atom. We will be able to observe state-to-state inelastic processes as well as reactive collisions leading to the formation of HeH+ molecule.

Results

Dynamics of PI

As a first demonstration of our approach, we study the PI and associative ionization (AI) channels of the collision between metastable helium and neutral argon

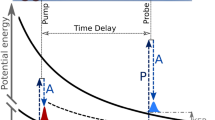

A schematic of the relevant potential curves together with calculated wave functions is presented in Fig. 1. The ionization process is described by the projection of the incoming wave function weighted by the square root of the autoionization width Γ(R) on one of the three possible ion-neutral potential surfaces, which are asymptotically separated on energy scale by the spin–orbit interaction energy of Ar+ (ΔESO = 0.178 eV). The energy of the ejected electron corresponds to the difference between the neutral and ionic potential curves25; therefore, information about the formation of a particular state is manifested in the electron energy distribution E(e−). The projection on the manifold of ionic states may result in a Ar+ product (PI), or a HeAr+ product (AI). However, a molecular ion generated in the electronically excited A2 state (Ψb) may decay via a Feshbach resonance26,27 to the continuum of the electronic ground X state (Ψf). As a result of the predissociation, the free Ar ion and neutral He acquire kinetic energy on the order of ΔESO. The kinetic energy distribution of Ar+ (E(atoms)) consists of low kinetic energy ions resulting from the direct PI reaction and high kinetic energy ions resulting from the predissociation process. In the following section, we present how the correlation between E(e−) and E(atoms) provides the observation of the process, by relating the high kinetic energy argon ions to a specific electron energy.

PECs obtained from refs. 38,39. Ψin represents the incoming wave function with wave number matching an energy of kB × 220 K. Ψb represents the first excited vibrational level of HeAr+ at the A2 electronic state. Ψf represents the scattering state wave function of the X state that couples to Ψb. Ψsc represents the scattering state wave function of the X state with maximal overlap with \(\sqrt{\varGamma }\cdot {\varPsi }_{{\rm{in}}}\). E(e−) represents energy distribution of ejected electrons and E(atoms) represents the energy distributed between He and Ar+(2P3/2). All wave functions were calculated using discrete variable representation40, the resonance width Γ(R) is taken from ref. 41.

Observation of the scattering resonance

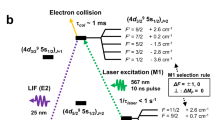

For the purpose of this study we designed and constructed a coincidence double velocity-map imaging (CDVMI) apparatus. A schematic of the setup is presented in Fig. 2. The 2D velocity distribution and the time-of-flight (TOF) of ions and electrons are obtained by a two-sided VMI28 spectrometer. Coincidence ion–electron pairs for a specific ion mass were selected by their TOF (cf. Methods) and their arrival positions were identified by correlation between optical brightness and electronic signal magnitude29. Mass-specific VMI images of ions and corresponding electrons are produced with complete mapping between the images.

Supersonic beams of metastable He (red) and ground state argon (purple) are shaped by a set of skimmers and slits before colliding in the center of a double VMI apparatus. Product ions and electrons are accelerated and their velocity is imaged by a set of 19 open-aperture electrodes followed by two free-field flight tubes. For both ions and electrons, arrival times and positions are detected by micro channel plate (MCP) detectors followed by phosphor screens.

Mass-selected VMI images of Ar+, HeAr+, and coincidence electrons are presented in Fig. 3. The VMI image of Ar+ consists of a central feature that presents low kinetic energy, forward-scattered Ar+ produced directly by PI, and a circular feature related to high kinetic energy Ar+, with a velocity magnitude centered at 269 m/s with a width of 16 m/s (all widths reported in this manuscript refer to half width at half maximum of a Gaussian distribution). The velocity magnitude of high kinetic energy Ar+ corresponds to a kinetic energy of 0.164 ± 0.019 eV, which is partitioned between Ar+ and neutral He. For HeAr+, the ionic VMI image consists of a single central feature at a center-of-mass velocity with an width of 19 and 13 m/s in longitudinal and transverse directions.

Coincidence VMI images of Ar+ and HeAr+ (a, d) and coincidence electrons (b, e). Ionic data are presented on a log scale to emphasize the outer circular feature which is the main interest of this paper. c, f Electron VMI images after rotation to the ionic frame of reference, where θ is defined as the relative angle between the 2D velocities of the electron and the ion.

The complete mapping between the ionic and the electronic VMI images enables the reconstruction of electronic VMI images corresponding to a given range of ionic radial velocities. Energy distribution of electrons was obtained by inversion of the rotated electron VMI images using MEVELER30 (cf. Methods). The electron energy distributions related to low and high kinetic energy Ar ions are presented in Fig. 4 as blue and red curves. The electron energy distribution related to low kinetic energy Ar ions contains two main peaks at 3.89 and 4.06 eV arising from the ionization of Ar by He*(3S). The two smaller peaks at around 4.87 and 4.69 eV correspond to ionization of Ar by He*(1S). The electron energy distribution related to high kinetic energy Ar ions presents a clear preference for electron energies that pinpoints the origin of those ions as the A2 electronic state. The observed additional kinetic energy of ~0.164 eV is gained by resonantly decaying from the quasi-bound A2 state to the free particle Ar+ (2P3/2) + He state as illustrated in Fig. 1.

The complementary dynamical picture is given by inspection of the AI channel. The electron energy distribution for electrons related to HeAr+ is presented in Fig. 4 (green curve) and shows clear preference for electron energies representing the formation of molecular ions at the X and A1 states. Any quasi-bound state formed upon ionization at the electronic A2 state dissociates with a lifetime much shorter than the particle TOF, and therefore is undetected as a molecular ion.

Free argon ions that originate from the dissociation of the quasi-bound HeAr+A2 state spend a fraction of their trajectory as a particle with increased mass, which results in a finite addition to their TOF. The lifetime of the quasi-bound A2 state can be extracted from the TOF of related ions using

where tb is the absolute TOF of the quasi-bound HeAr+ in the A2 state before dissociation, ΔTOF is the addition to the ions TOF relative to the center TOF peak of Ar+, and \(\frac{{m}_{{\mathrm{Ar}}}}{{m}_{{\mathrm{HeAr}}}}\) is the mass ratio. Figure 5 presents the observed exponential decay of tb for Ar+ with a radial velocity between 209 and 295 m/s, with an observed lifetime of 1.01 μs. Our lifetime measurement is not sensitive enough to resolve lifetimes arising from different rovibrational states; however, the measured lifetime falls into the range predicted by theory31. Further support of our observation is given by the lack of Feshbach ions in previous studies of Ne* + Ar PI reaction due to the long lifetime of the quasi-bound NeAr+ A2 state31,32.

In conclusion, we have presented an experimental method that provided a state resolved description of ion-neutral dynamics. For the HeAr+ system, this enabled the observation of a Feshbach resonance identified as the predissociation of the HeAr+ A2 molecular state. Although the kinetic energy distributions of He* + Ar PI products were obtained in previous experiments31,33,34, the lack of correlation between ionic and electronic data left the details of the postionization dynamics completely hidden. Coincidence detection of ions and electrons provides the mapping between initial and final states and enables the direct observation of the scattering resonance.

Our approach may be generalized to any ion-neutral system accessible via PI reaction. Specifically, study of PI of molecules, where rovibrational degrees of freedom span the manifold of ion-neutral potential curves, may pave the way to a multitude of possible experiments studying state-to-state inelastic and reactive collisions between molecular ions and neutral atoms. Specifically, the study of PI ionization of hydrogen molecule by metstable helium will enable the observation of state-to-state collisional quenching of vibrationally excited H\({}_{2}^{+}\) and state-to-state reactive H\({}_{2}^{+}\) + He collisions leading to the formation of HeH+.

Methods

Experimental setup

A pulsed supersonic beam of a 50/50% mixture of argon and helium was created by an Even-Lavie (EL) valve35 and had a mean velocity of 784 m/s and a width of 21 m/s. A second pulsed beam of pure helium was created by another EL valve oriented at an angle of 4. 5° relative to the first valve and had a mean velocity of 1786 m/s and a width of 72 m/s. Helium was excited to the 21S and 23S states by a dielectric barrier discharge36 located directly after the valve. The beams passed through a 1 mm skimmer located 43 cm downstream from the valves orifice. The beams were then further shaped by a set of two double circular slits with diameter of 3 and 1 mm located 2.5 and 6.5 cm after the skimmer accordingly. The two beams crossed at the center of the CDVMI apparatus 58 cm relative to the valves orifice, where atoms collided with a collision energy of kB × 222 ± 33 K. Ions and electrons were accelerated and velocity imaged by a set of 19 electrodes, 8 on the electron side and 11 on the ion side. The electrodes had varying inner diameter (10–48 mm) and fixed outer diameter of 130 mm and were spaced by a 10 mm distance. Following the VMI electrodes, particles entered a field free region defined by two flight tubes, 20 cm long on the electron side and 62 cm long on the ion side. The electron flight region is surrounded by a cylindrical sheet of mu-metal for protection against the effect of external magnetic fields. Both ions and electrons were accelerated to an energy of about 2 keV toward a time and position sensitive MCP detector followed by a phosphor screen, P46 on ion side and P43 on electron side. The potentials on all electrodes and MCP plates were kept constant throughout the experiment. Arrival positions of ions and electrons were captured by a CCD camera and their arrival times were digitized using a fast scope. Experiments were performed in a 10 Hz repetition rate. Results presented in this work were obtained from a data set containing 1.1 million valves shots. The exact geometry of the ion optics was designed based on classical trajectory simulations using SIMION program, optimized for maximal resolution \(\frac{v}{\Delta v}\). For HeAr ions at 875 m/s, SIMION simulations predict VMI resolution of 3.2 m/s. Experimental electron-recoil corrected VMI image of HeAr ions demonstrated transverse width of 4.1 m/s, which corresponds to energy resolution of 0.004 meV. The resolution along the beam propagation axis is limited by the spread in center-of-mass velocity (~20 m/s). For 4.06 eV electrons, the observed width of 49 meV provides the upper limit for the resolution, which is predicted by SIMION simulations to be 25 meV.

Data analysis and coincidence

For every valve shot, the acquired experimental data included ions and electrons arrival times and amplitude of electronic signal as measured on the MCP back plate, arrival position, and the magnitude of the optical signal as obtained from the recorded images of the phosphorus detector. The mass distribution of detected ions was obtained by plotting a histogram of their TOF (cf. Mass spectrum). The obtained mass spectrum provides the limits of ion–electron TOF difference that are used for identification of coincidence in certain mass-to-charge ratio ion–electron pairs. Coincidence by TOF is possible in our experiment due to the narrow spread in the TOF for a given ion mas-to-charge ratio (~0.01 μs) relative to the large overlap in time between the reactant beams (~30 μs). Once an ion–electron pair is identified by TOF, the related ion and electron arrival positions are selected from the measured optical signals based on the correlation between optical phosphorus detector brightness and amplitude of electronic MCP signal29. The resulted mass-selected coincidence VMI images of ions and electrons are shown in Fig 3. The ratio between camera pixels and velocity on the ionic VMI images was found by examining the shift in position of center-of-mass velocity for a variety of single beam Ar–He gas mixtures.

Mass spectrum

TOF distribution of detected ions is presented at Fig. 6. We observe two main peaks at TOF of 9.2 and 9.6 μs that correspond to Ar+ and HeAr+ accordingly. CDVMI performs as a mass spectrometer with a resolving power (FWHM) of \(\frac{m}{\Delta m}=1000\) for Ar and \(\frac{m}{\Delta m}=1500\) for HeAr. The use of CDVMI as a mass spectrometer may be applied to any sample containing atoms and molecules with ionization energy smaller then excitation energy of the metastable atom.

Electron energy distributions

Information about energy distribution of electrons requires the inversion of the 2D velocity distribution (Fig. 3b, e) to a 3D velocity distribution37. Since any inversion method requires an axis of cylindrical symmetry, the electron images were rotated to the ionic frame of reference (Fig. 3c, f). We attribute the anisotropy of the electron VMI images to a nonuniform collection efficiency, resulting from the mismatch of beams overlap position relative to the VMI orifice. Electron energy distributions presented in Fig. 4 were obtained by inversion of rotated electron VMI images using MEVELER30. The resulted velocity magnitude distribution was scaled to energy scale by the known energy difference between metastable states of He.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Lee, Y.-T., McDonald, J., LeBreton, P. & Herschbach, D. Molecular beam reactive scattering apparatus with electron bombardment detector. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 40, 1402–1408 (1969).

Lee, Y. T. Molecular beam studies of elementary chemical processes. Science 236, 793–798 (1987).

Gao, Z. et al. Observation of correlated excitations in bimolecular collisions. Nat. Chem. 10, 469–473 (2018).

Henson, A. B., Gersten, S., Shagam, Y., Narevicius, J. & Narevicius, E. Observation of resonances in Penning ionization reactions at sub-kelvin temperatures in merged beams. Science 338, 234–238 (2012).

Lavert-Ofir, E. et al. Observation of the isotope effect in sub-kelvin reactions. Nat. Chem. 6, 332–335 (2014).

Zou, J., Gordon, S. D. & Osterwalder, A. Sub-kelvin stereodynamics of the Ne (3P2)+ N2 reaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 133401 (2019).

Shagam, Y. et al. Molecular hydrogen interacts more strongly when rotationally excited at low temperatures leading to faster reactions. Nat. Chem. 7, 921–926 (2015).

Klein, A. et al. Directly probing anisotropy in atom–molecule collisions through quantum scattering resonances. Nat. Phys. 13, 35–38 (2017).

Zewail, A. H. Femtochemistry: atomic-scale dynamics of the chemical bond. J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 5660–5694 (2000).

Weichman, M. L. & Neumark, D. M. Slow photoelectron velocity-map imaging of cryogenically cooled anions. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 69, 101–124 (2018).

Weichman, M. L., DeVine, J. A., Babin, M. C., Li, J. & Guo, L. Feshbach resonances in the exit channel of the F+CH3OH → HF+CH3O reaction observed using transition-state spectroscopy. Nat. Chem. 9, 950–955 (2017).

Mikosch, J. et al. Imaging nucleophilic substitution dynamics. Science 319, 183–186 (2008).

Stei, M. et al. Influence of the leaving group on the dynamics of a gas-phase SN2 reaction. Nat. Chem. 8, 151–156 (2016).

Allmendinger, P. et al. New method to study ion–molecule reactions at low temperatures and application to the reaction. ChemPhysChem 17, 3596–3608 (2016).

Allmendinger, P., Deiglmayr, J., Höveler, K., Schullian, O. & Merkt, F. Observation of enhanced rate coefficients in the H\({}_{2}^{+}\) + H2 → H\({}_{2}^{+}\) + H reaction at low collision energies. J. Chem. Phys. 145, 244316 (2016).

Hall, F. H. & Willitsch, S. Millikelvin reactive collisions between sympathetically cooled molecular ions and laser-cooled atoms in an ion-atom hybrid trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 233202 (2012).

Siska, P. Molecular-beam studies of Penning ionization. Rev. Mod. Phys. 65, 337 (1993).

Kunitski, M. et al. Observation of the efimov state of the helium trimer. Science 348, 551–555 (2015).

Pitzer, M. How to determine the handedness of single molecules using coulomb explosion imaging. J. Phys. B 50, 153001 (2017).

Dörner, R. et al. Cold target recoil ion momentum spectroscopy: a momentum microscope to view atomic collision dynamics. Phys. Rep. 330, 95–192 (2000).

Ullrich, J. et al. Recoil-ion and electron momentum spectroscopy: reaction-microscopes. Rep. Prog. Phys. 66, 1463 (2003).

Eland, J. Photoelectron-photoion coincidence spectroscopy: I. Basic principles and theory. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Phys. 8, 143–151 (1972).

Sztáray, B. et al. Crf-pepico: double velocity map imaging photoelectron photoion coincidence spectroscopy for reaction kinetics studies. J. Chem. Phys. 147, 013944 (2017).

Hotop, H. Analyses of ions and electrons resulting from Penning ionization. Radiat. Res. 59, 379–404 (1974).

Miller, W. H. Theory of Penning ionization. I. Atoms. J. Chem. Phys. 52, 3563–3572 (1970).

Feshbach, H. Unified theory of nuclear reactions. Ann. Phys. 5, 357–390 (1958).

Fano, U. Effects of configuration interaction on intensities and phase shifts. Phys. Rev. 124, 1866 (1961).

Eppink, A. T. & Parker, D. H. Velocity map imaging of ions and electrons using electrostatic lenses: application in photoelectron and photofragment ion imaging of molecular oxygen. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 68, 3477–3484 (1997).

Urbain, X. et al. A zero dead-time multi-particle time and position sensitive detector based on correlation between brightness and amplitude. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 86, 023305 (2015).

Dick, B. Inverting ion images without abel inversion: maximum entropy reconstruction of velocity maps. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 570–580 (2014).

Blech, A. et al. Phase protection of Fano-Feshbach resonances. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–7 (2020).

Delmdahl, R. F., Bakker, B. L. & Parker, D. H. Crossed-beam velocity map imaging of collisional autoionization processes. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 7728–7730 (2000).

Ohno, K., Yamakado, H., Ogawa, T. & Yamata, T. Collision-energy/electron-energy resolved two-dimensional study of Penning ionization of ar by he metastable atoms 23S and 21S. J. Chem. Phys. 105, 7536–7542 (1996).

Longley, E., Dunlavy, D., Falcetta, M., Bevsek, H. & Siska, P. Recent retreats in Penning ionization: a new look at the He*(21S)+ Ar → He + Ar+ + e− reaction in crossed molecular beams. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 2097–2105 (1993).

Even, U., Jortner, J., Noy, D., Lavie, N. & Cossart-Magos, C. Cooling of large molecules below 1 k and he clusters formation. J. Chem. Phys. 112, 8068–8071 (2000).

Luria, K., Lavie, N. & Even, U. Dielectric barrier discharge source for supersonic beams. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 80, 104102 (2009).

Ashfold, M. N. et al. Imaging the dynamics of gas phase reactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8, 26–53 (2006).

Hapka, M., Chałasiński, G., Kłos, J. & Żuchowski, P. S. First-principle interaction potentials for metastable He(3S) and Ne(3P) with closed-shell molecules: application to penning-ionizing systems. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 014307 (2013).

Carrington, A. et al. Microwave spectroscopy and interaction potential of the long-range He... Ar+ ion. J. Chem. Phys. 102, 2379–2403 (1995).

Colbert, D. T. & Miller, W. H. A novel discrete variable representation for quantum mechanical reactive scattering via the s-matrix kohn method. J. Chem. Phys. 96, 1982–1991 (1992).

Bibelnik, N. et al. Cold temperatures invert product ratios in penning ionisation reactions with argon. Mol. Phys. 117, 2128–2137 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Sade of the Weizmann CNC Section and A. Kuprienko of the Weizmann Chemical Research Support for assistance in designing and manufacturing the experiment components. We acknowledge funding from the European Research Council and the Israel Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.M., J.N., and E.N. designed and constructed the CDVMI apparatus. B.M. performed the measurements. E.N. planned and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Margulis, B., Narevicius, J. & Narevicius, E. Direct observation of a Feshbach resonance by coincidence detection of ions and electrons in Penning ionization collisions. Nat Commun 11, 3553 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17393-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17393-0

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.