Abstract

The glass-forming ability is an important material property for manufacturing glasses and understanding the long-standing glass transition problem. Because of the nonequilibrium nature, it is difficult to develop the theory for it. Here we report that the glass-forming ability of binary mixtures of soft particles is related to the equilibrium melting temperatures. Due to the distinction in particle size or stiffness, the two components in a mixture effectively feel different melting temperatures, leading to a melting temperature gap. By varying the particle size, stiffness, and composition over a wide range of pressures, we establish a comprehensive picture for the glass-forming ability, based on our finding of the direct link between the glass-forming ability and the melting temperature gap. Our study reveals and explains the pressure and interaction dependence of the glass-forming ability of model glass-formers, and suggests strategies to optimize the glass-forming ability via the manipulation of particle interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In studies of glass transition and jamming transition1,2,3,4,5, binary mixtures of particles are widely employed to avoid crystallization. If the two components mix up randomly, the particle size mismatch can frustrate the global structural order6. However, under certain circumstance, some binary mixtures may undergo phase separation or demixing during the solid formation, i.e., the same types of particles aggregate. Although undesirable in disordered systems, phase separation has attracted much attention in many fields7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

The glass-forming ability (GFA), i.e., the capacity of a material to resist crystallization and maintain glassy, is fundamental in studies of glasses. A binary mixture prone to phase separation tends to form crystallites of the same type of particles, and hence has a poor GFA. Because glasses are diverse and out of equilibrium, it is difficult to establish a common understanding of the GFA. Moreover, phase separation is one of the multiple forms of crystallization. Under certain conditions, binary mixtures can also form complex crystalline or quasicrystalline structures15,16, which complicates further the understanding of the GFA to fight against them. Among various interpretations, geometric and energetic frustrations are thought to be essential to the determination of the GFA17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

For binary mixtures, varying the size ratio γ of the large to small particles is an effective way to cause geometric frustration. However, it has been shown that a large γ often promotes phase separation and thus results in poor GFAs for binary mixtures of hard particles, mainly arising from entropy effects14,24,25,26,27,28,29. To suppress phase separation, a moderate size ratio, 1 < γ < 2, is usually adopted. However, it is still unclear if such ratios can prevent phase separation and maintain glassy states after extremely long equilibration. Even with these size ratios, the GFA is sensitive to the particle composition. It has been suggested that the GFA of binary mixtures is the best near the eutectic point or triple point when particle composition is varied23.

In this work, we pay more attention to the energetic frustration on the GFA by studying binary mixtures of soft particles interacting via finite-range repulsions. In the zero temperature (T = 0) and zero pressure (p = 0) limit, such soft particles behave like hard ones30,31. Taking a mixture in the hard particle limit as the reference, which has a decent GFA with certain values of particle size ratio and composition, we vary the pressure (density) and track the evolution of the GFA. When pressure increases, the potential energy plays a more important role and offers soft particles extra opportunities of phase separation. With the intervention of potential energy, the particle size ratio γ, the cause of geometric frustration, may excite and affect energetic frustration as well and hence affect the GFA. We aim at looking for some simple energetic criteria of the GFA and proposing some energy strategies to manipulate it, via the study of the effects of pressure and particle interaction.

We study two types of widely employed model glass-formers, binary mixtures of soft particles interacting via harmonic or repulsive Lennard-Jones (RLJ) repulsion. Both types of systems with a diameter ratio γ = 1.4 and a 50:50 particle composition have been used in many studies of glasses. At low pressures, both systems exhibit a pressure-independent GFA, equal to that of the hard particle counterparts. At high pressures, the GFA of RLJ systems still remains almost constant, but remarkable phase separation occurs in harmonic systems. Therefore, γ = 1.4 does cause not only geometric but also energetic frustrations in soft particle systems. By performing analytic calculations, we find that the behaviors of the GFA can be explained by the pressure dependence of the melting temperatures of the two components, confirmed by our simulation results. This thus builds up a bridge between non-equilibrium and equilibrium quantities and suggests that the pressure dependence of the melting temperatures of constituent components can be an energetic precursor to evaluate the GFA of glass-formers. We also show that the GFA of the hard particle limit can be achieved at high pressures by a proper modulation of the particle stiffness. Combining our work and previous studies on the composition effects23, we expect to achieve a much more comprehensive understanding of the GFA of binary mixtures with effects of composition, pressure, and particle interaction being all included.

Results

Control variables of binary mixtures

We denote the two types of particles in binary mixtures as A and B particles. The particle composition is quantified by the concentration of B particles, cB = NB/(NA + NB), with NA and NB being the numbers of A and B particles, respectively. There are two quantities to make the constituent A and B particles different. One is the particle size. When the diameter ratio γ = σA/σB > 1, A and B particles differ in size, where σA and σB are diameters of A and B particles, respectively. The other is the particle stiffness, characterized by the interaction energy scale ϵAA and ϵBB as defined in Eqs. (17) and (18) of the Methods section. A particles are softer than B particles if ϵAA < ϵBB. Here we manipulate the particle stiffness by letting ϵAA = (1 + Δ)ϵAB and ϵBB = (1 − Δ)ϵAB with Δ\(\in\)[−1, 1]. One of our primary goals is to study and understand the pressure dependence of the GFAs of widely employed model glass-formers with γ = 1.4, cB = 0.5, and Δ = 0 (ϵAA = ϵBB = ϵAB). This manipulation of particle stiffness can facilitate the analytic calculations with Δ being an independent variable, from which the solutions of Δ = 0 can be straightforwardly obtained.

In a rather different perspective from most of the previous studies, we are mainly concerned about the effects of pressure and particle interaction on the GFA. Here we mainly show results of N = NA + NB = 4096 systems in two dimensions. Because the simulations are rather expensive, we have only repeated part of the simulations for larger systems and three-dimensional systems and find consistent results. In the following, we will first present results for harmonic and RLJ systems with γ = 1.4, cB = 0.5, and Δ = 0. Then we will attack the special case with γ = 1 and cB = 0.5. By varying Δ, we are able to sort out potential energy effects without the interference of geometric frustration caused by the particle size distinction. Based on observations of γ = 1, we will derive a generalized picture for γ > 1, from which the results of systems with γ = 1.4, cB = 0.5, and Δ = 0 can be understood. Finally, we will show that the same picture applies to different values of cB.

Characterization of glass-forming ability

For given values of γ, cB, Δ, and p, we start with a liquid equilibrated at about four times of the melting temperature of B particles as defined later, and then decrease the temperature by a small step δT and relax the system for a duration Δt by performing molecular dynamics simulations under constant temperature and pressure. The same procedure is repeated until a solid-like state at a temperature about one-tenth of the melting temperature is achieved. This leads to a quench rate κ = δT/Δt. We compare the GFAs over a wide range of pressures, which have been rarely studied before. It is tricky how to choose a reasonable quench rate to include the pressure effects. Here, we use a dimensionless quench rate \(\tilde{\kappa }\) as defined and discussed in the Methods section, in purpose of giving supercooled liquids at different pressures comparable opportunities to relax their structures.

In the parameter space considered in this work, we have not observed the formation of complex crystalline structures within our simulation time window, so the crystallization mainly takes the form of phase separation23. Therefore, the GFA can be well characterized by the degree of mixing of A and B particles against phase separation in the resultant solid-like states, which is quantified here by the parameters

where the sum is over all A or B particles, \({\delta }_{{n}_{{\rm{s}}i},{n}_{i}}\) is the Kronecker delta, ni is the number of nearest neighbors of particle i, and nsi is the number of nearest neighbors which are the same type as particle i. We calculate χA and χB for A and B particles separately. Their values are close to 0 when two components mix up well. With more particles being separated, the values grow up and approaches 1 for well-separated states. Therefore, smaller values of χA and χB mean better GFAs.

Although χA and χB can characterize the GFA well in our work, we should realize that they may not work well to distinguish glasses from complex crystals with A and B particles being mixed15,16. This is the limitation of the parameters when studying the GFA against the formation of complex crystals. In that case, one needs to select appropriate parameters to characterize the structural order to distinguish complex crystals from amorphous solids, which is out of the scope of current work.

Glass-forming ability for γ = 1.4 and c B = 0.5 with Δ = 0

Figure 1a, b compare the GFAs of binary mixtures of harmonic and RLJ particles in two dimensions with γ = 1.4, cB = 0.5, and Δ = 0, so there is no cause of strong energetic frustration. These binary mixtures have been widely employed as good glass-formers in previous studies.

a, b are for harmonic and RLJ systems, respectively, with γ = 1.4, cB = 0.5, and Δ = 0. The solid and empty symbols are χA and χB, respectively. Circles, squares, and diamonds are for dimensionless quench rate \(\tilde{\kappa }=8.16\times {10}^{-11}\), 8.16 × 10−10, and 8.16 × 10−9, respectively. The lines are guides for the eye. The vertical dot-dashed line in a shows the crossover pressure pn ≈ 0.14 (also shown in Fig. 2a for comparison), at which the melting temperatures of A and B particles intersect and χA is approximately equal to χB, as discussed in the text. c Snapshots of solid-like states for harmonic systems. From top to bottom, \(\tilde{\kappa }\) decreases. From left to right, pressure p increases with the values being shown at the bottom. The yellow and blue disks are A (large) and B (small) particles. To distinguish particles, we have moderately decreased the particle diameters by 10–25%.

In the T → 0 and p → 0 limit when particle overlap is tiny, both harmonic and RLJ systems are equivalent to hard particle systems30,31 and exhibit similar GFAs to that of the hard particle counterpart with γ = 1.4 and cB = 0.5. As shown in Fig. 1a, b, both χA(p) and χB(p) tend to approach a constant at low pressures for both systems.

Because of aging, χA(p) and χB(p) evolve with the quench rate \(\tilde{\kappa }\). Fig. 1 compares three values of \(\tilde{\kappa }\). At low pressures, χB(p) (for small particles) remains small when \(\tilde{\kappa }\) decreases, while χA(p) (for large particles) grows up. As illustrated by snapshots in Fig. 1c, A particles form clusters when \(\tilde{\kappa }\) is small, even at low pressures. It is expected that with even smaller \(\tilde{\kappa }\) the clustering or phase separation will be stronger. Here A and B particles have the same concentration. The separation can be weakened by increasing cB to around 0.623 in order to leave smaller rooms for A particles to aggregate, as will be shown later, but it remains elusive whether the separation is inevitable as long as the waiting time is sufficiently long32,33.

The decrease of \(\tilde{\kappa }\) at fixed pressure is analogous to the decrease of the compression rate at fixed temperature. The emergence of phase separation at low pressures thus suggests that with sufficiently slow compression rates binary mixtures of hard particles with γ = 1.4 and cB = 0.5 will undergo phase separation. Therefore, we show direct evidence suggesting that such binary mixtures widely employed as good glass-formers cannot prevent phase separation, so that thermodynamically stable states may be phase-separated. Figure 1 also shows that, although behaving similarly at low pressures, harmonic and RLJ systems have significantly different GFAs at high pressures. The GFA of RLJ systems still remains almost constant in pressure. In contrast, harmonic systems undergo apparent phase separation, with χB(p) increasing quickly when pressure increases. Apparently, at high pressures, some energetic frustration is excited strongly in harmonic systems, destabilizing the mixing of particles. The particle size distinction triggers such energy effects. Moreover, note that harmonic and RLJ systems have almost identical GFAs up to p ≈ 10−2, which is already far beyond the hard particle limit where particle interactions are not negligible. Then it is interesting to know why harmonic and RLJ systems can have similar GFAs beyond the hard particle limit, why RLJ systems can maintain an almost constant GFA to high pressures, and why the GFA of harmonic systems quickly drops at high pressures.

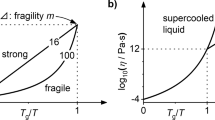

Harmonic and RLJ repulsions are distinct in their respectively bounded (soft-core) and unbounded natures. The soft-core nature of harmonic repulsion induces rich phase behaviors at high densities34,35,36,37,38. Unlike RLJ particles whose melting (crystallization) or glass transition temperature always increases with the increase of pressure39,40,41,42,43, harmonic particles exhibit reentrant liquid-solid transitions with the transition temperatures being non-monotonic in pressure and some related extraordinary phenomena36,37,38,44,45,46,47,48,49. We will show that it is just this non-monotonic behavior that makes harmonic systems to have dramatically distinct GFA from RLJ systems.

Melting temperature gap between components

In this subsection, we will introduce two effective melting temperatures, Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p), for A and B particles, respectively. We will see that they are not the actual equilibrium melting temperatures, which should be obtained from complicated calculations of the equilibrium phase diagram and would vary with cB23,50. They are instead derived from the equilibrium melting temperature of mono-component systems and the simple conversion of units. However, they turn out to work well to characterize the GFA.

An interesting feature shown in Fig. 1a is that χA(p) and χB(p) of harmonic systems intersect at roughly the same pressure pn at different quench rates. When p < pn, χA > χB, so A particles are easier than B particles to form clusters. When p > pn, χA < χB. The clustering or nucleation starts below the melting temperature. If χB > χA, B particles may experience a longer time than A particles to nucleate, suggesting that the melting temperature of B particles is higher, and vice versa. Therefore, we doubt whether Fig. 1a implies that B particles have a lower (higher) melting temperature than A particles when p < pn (p > pn). If this is the case, melting temperature would play an important role in the determination of the GFA, but the question is how A and B particles can feel different melting temperatures in the same mixture.

Note that temperature is the energy, and we are concerned about pressure effects. As defined in the Methods section, for two-dimensional mixtures, the temperature and pressure are in units of \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{AB}}}{k}_{{\rm{B}}}^{-1}\) and \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{AB}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{-2}\), respectively. However, A and B particles also have their own temperature and pressure units, which are \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{AA}}}{k}_{{\rm{B}}}^{-1}\) and \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{AA}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{A}}}^{-2}\) for A particles and \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{BB}}}{k}_{{\rm{B}}}^{-1}\) and \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{BB}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{-2}\) for B particles, respectively. Therefore, in the mixture at a pressure p in units of \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{AB}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{-2}\), A and B particles effectively feel different pressure values, PA and PB, in their own units:

Let us denote Tm(p) as the melting temperature of mono-component systems, i.e., when γ = 1 and Δ = 0 so that A and B particles are identical. In the mixture, since A and B particles feel different pressures in their own units, the corresponding melting temperatures are Tm(PA) and Tm(PB), respectively. In the common units of \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{AB}}}{k}_{{\rm{B}}}^{-1}\), the melting temperatures that A and B particles feel are thus

This leads to a melting temperature gap

Apparently, both γ and Δ can affect ΔTm(p). Note that there is a special case: When Tm(p) is linear, i.e., Tm(p) = Cp with C being the system-dependent coefficient,

so the melting temperature gap is no longer a function of Δ. We will see later that such a linear behavior is crucial to the understanding of the pressure and interaction dependence of the GFA.

Given Tm(p), Eq. (4) indicates that Tm,A(p) can be obtained by multiplying the pressure and temperature of Tm(p) curve by γ−2(1 + Δ) and 1 + Δ, respectively. Correspondingly, Eq. (5) shows that Tm,B(p) can be obtained by multiplying the pressure and temperature of Tm(p) curve by 1 − Δ and 1 − Δ, respectively. For the cases shown in Fig. 1 with γ = 1.4 and Δ = 0, we have Tm,A(p) = Tm(γ2p) and Tm,B(p) = Tm(p). Fig. 2 shows the melting temperatures against pressure for both harmonic and RLJ systems with γ = 1.4 and Δ = 0. In the log–log scale, Tm,A(p) is obtained by just shifting the Tm(p) curve horizontally by an amount of log10(γ−2) = −2log101.4, while Tm,B(p) is the same as Tm(p). If Tm monotonically increases with p, Tm,A(p) is always larger than Tm,B(p), as shown in Fig. 2b for RLJ systems. If Tm(p) is non-monotonic, Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) may intersect. As shown in Fig. 2a, Tm(p) of harmonic systems is non-monotonic in p, so Tm,A(p) = Tm,B(p) at p ≈ 0.14. In Fig. 1a, we display this pressure as the vertical dot-dashed line. Interestingly, it roughly agrees with pn at which χA = χB.

a, b are for harmonic and RLJ systems, respectively. Squares and circles are for Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p), respectively, with γ = 1.4 and Δ = 0. The dashed lines show the linear behavior. The vertical dot-dashed line in a shows the crossover pressure at which Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) intersect. By comparing with Fig. 1a, it is roughly pn at which χA = χB. The inset of a shows how the equilibrium melting temperature Tm(p) is determined from simulation, which is also Tm,B(p) with Δ = 0 by definition. At a fixed pressure p, the melting temperature Tm (marked as the vertical dashed line) is the temperature at which the density ρ undergoes an abrupt change with the decrease of temperature.

This agreement indicates that our hypothesis that the difference between χA and χB, as shown in Fig. 1, is related to the difference between melting temperatures felt by A and B particles is valid. This is further supported by RLJ systems. For RLJ systems, Tm,A(p) is always larger than Tm,B(p) because Tm(p) monotonically increases, consistent with the fact that χA(p) is always larger than χB(p), as shown in Fig. 1b.

Although Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) are not the actual equilibrium melting temperatures, the concurrence of Tm,A = Tm,B and χA = χB at p = pn for harmonic systems suggests that ΔTm(p) defined here at least qualitatively reflects the correct pressure evolution of the gap between equilibrium melting temperatures. This can also be seen from the resultant solid-like states visualized in Fig. 1c. For harmonic systems at p > pn, Tm,A < Tm,B and strong phase separation occurs. From the crystallization mechanism, the liquidus line is in coexistence with the B-solid. When Tm,A < T < Tm,B, B particles crystallize, while A particles can crystallize until T < Tm,A. For phase-separated states obtained from finite quench rates, this sequence of the two-step crystallization would result in purer B-solids than A-solids, i.e., isolated A (B) particles are poor (rich) in B-solids (A-solids), as shown by the snapshots at p = 0.2 in Fig. 1c. The snapshots at other pressures show the opposite behavior when p < pn and Tm,A > Tm,B.

Seen from Fig. 2, another interesting and important feature is that Tm(p) ~ p at low pressures for both harmonic and RLJ systems. The melting temperature curves deviate from linear at high pressures, where harmonic and RLJ systems exhibit significantly different GFAs. The comparison between Figs. 1 and 2 shows that the GFAs maintain almost constant at fixed dimensionless quench rate \(\tilde{\kappa }\) roughly in the pressure regime where Tm(p) is linear. Then the question is whether this is just a coincidence or implies some underlying correlations.

Mixing and demixing for γ = 1 and c B = 0.5

In this work, we focus on the potential energy effects on the GFA. Therefore, before understanding the results of systems with γ = 1.4, cB = 0.5, and Δ = 0, we would like to discuss first a simpler case with γ = 1 and cB = 0.5, so that A and B particles have the same size and geometric frustration induced by particle size difference is absent. Then, it would be clearer to sort out the underlying physics of the evolution from mixing to demixing of two types of particles with only energetic frustration being involved, which provides us with crucial clues to understand the γ = 1.4 case. In the next subsection, we will show that the findings for γ = 1 can be generalized to γ > 1.

With the variation of Δ, A and B particles have different stiffness, leading to energetic frustration affecting the mixing of particles. Because of the trivial symmetry of γ = 1, now we only need to vary Δ from 0 to 1. When Δ = 0, A and B particles are trivially the same and should statistically mix up well. When Δ increases from 0, the distinction in particle stiffness leads to the variation in particle overlap, in analogy to the evolution with the growth of γ51. It is thus expected that phase separation will occur when Δ is large. Fig. 3a shows examples of χB(Δ) of the resultant solid-like states at different pressures and a fixed dimensionless quench rate for harmonic systems. χA(Δ) behaves similarly to χB(Δ), so we do not show it here. In this and the next subsections, because we extend the pressure to much lower values, to use the same dimensionless quench rates \(\tilde{\kappa }\) as in Fig. 1 is far beyond our computational capacity. Therefore, we use faster \(\tilde{\kappa }\). We have verified (not shown here) that the results to be presented are reproducible with different values of \(\tilde{\kappa }\). At fixed pressure, Fig. 3a shows that there is a crossover Δc below which χB remains small and constant. When Δ > Δc, χB grows up, so Δ = Δc signals the onset of phase separation. Fig. 3a also shows that Δc increases when pressure decreases.

Here we show results for γ = 1 and cB = 0.5 systems with the variation of Δ at \(\tilde{\kappa }=1.22\times {10}^{-6}\). a Evolution of χB with Δ in solid-like states for harmonic systems at p = 10−5 (diamonds), 10−4 (triangles), 10−3 (circles), and 0.12 (squares). The lines are guides for the eye. Curves in dark green are in the pressure regime of p < pc as defined in b, where Tm(p) is linear. The orange curve is at p > pc where Tm(p) is nonlinear. b Phase diagram in the temperature and pressure plane for harmonic systems with Δ = 0.95. The diamonds, squares, and circles are melting temperature curves Tm(p), Tm,A(p), and Tm,B(p), respectively. The dashed line shows the linear behavior. The vertical dot-dashed lines label pc,B, pc, and pc,A, at which the melting temperature curves deviate from linear by 5%. The gray area below melting temperatures and to the left of p = pc,B is where the system can mix well (labeled by “mix”). The area below melting temperatures and to the right of p = pc,B is where A and B particles tend to demix (labeled by “demix”). Above melting temperatures are liquids. c Crossover Δ†(p) (solid line) and the iso-χB contours (dashed lines) for harmonic systems. The gray area is Δ ≤ Δ†, where ΔTm = 0. d Scaling collapse of χB(ΔTm) at p = 10−5 (diamonds), 10−4 (triangles), and 10−3 (circles) for harmonic (solid) and RLJ (empty) systems, with ν ≈ 1.02. The squares with a dashed line show the deviation from the master curve at p = 0.12 > pc for harmonic systems.

The appearing consistency between the constant GFA at low pressures and the linear Tm(p) as discussed in the previous subsection stimulates us to investigate whether the emergence of phase separation at Δc is also correlated with the linearity of Tm(p). Fig. 3b shows an example of the temperature-pressure phase diagram of harmonic systems with Δ = 0.95. Here we draw Tm(p) together with Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p). Seen from Eqs. (4) and (5), when γ = 1, Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) are simply obtained by shifting the Tm(p) curve in both horizontal and vertical directions simultaneously by the same amount of log10(1 + Δ) and log10(1 − Δ), respectively, in the temperature-pressure plane with log–log scale. In Fig. 3b, we denote pc as the crossover pressure above which Tm(p) becomes nonlinear. Here, we set pc ≈ 0.004 at which Tm(p) deviates from linear by 5%. Correspondingly, Eqs. (4) and (5) indicate that Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) become nonlinear at pc,A = pc(1 + Δ) and pc,B = pc(1 − Δ), respectively, when γ = 1. Because Δ > 0, Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) collapse and are both linear when p < pc,B. Seen from Eq. (7), the melting temperature gap ΔTm(p) = 0 when p < pc,B, and ΔTm(p) > 0 otherwise. Therefore, in the pressure regime where p < pc, p = pc,B = pc(1 − Δ†) sets a crossover

below (above) which ΔTm = 0 (ΔTm > 0). In the pressure regime where p > pc, any nonzero Δ leads to ΔTm ≠ 0, so Δ† = 0. Note that both Δ† and Δc increase when pressure decreases. It is then natural to ask whether they are related.

Figure 3c shows Δ†(p) together with the iso-χB contours for harmonic systems at fixed \(\tilde{\kappa }\). With the decrease of χB, the contours approach Δ†(p). The contours may shift upward gradually with the decrease of \(\tilde{\kappa }\). With current computational capacity, we expect from Fig. 3c that Δ† agrees with Δc. Next, we will show that this expectation is valid.

At fixed pressure, the melting temperature gap ΔTm is the function of Δ, as shown by Eq. (6). Therefore, χB(Δ) shown in Fig. 3a can be converted to χB(ΔTm). This functional relation establishes the connection between the GFA characterized by χB and the melting temperature gap ΔTm for γ = 1. Fig. 3d shows χB(ΔTm) curves at different pressures for both harmonic and RLJ systems. At all pressures, χB has a minimum when ΔTm = 0. With the increase of ΔTm, χB increases and phase separation emerges. Interestingly, in the pressure regime where p < pc and Tm(p) is linear, all χB(ΔTm) curves can collapse nicely onto the same master curve, when χB is plotted against ΔTm/pν with ν ≈ 1.02 for both harmonic and RLJ repulsions. Figure 3d also shows that the scaling collapse stops working when p > pc, highlighting the important role of the linear Tm(p).

The scaling collapse indicates that at different pressures lower than pc, in order to reach the same degree of particle mixing or demixing, the variation of particle stiffness (Δ) needs to cause a melting temperature gap ΔTm proportional to pressure. In this pressure regime, Tm,A(p) is always linear, i.e., Tm,A(p) = Cp. From Eq. (6), we have

when Δ > Δ† and ΔTm > 0. The right hand side of Eq. (9) is constant in pressure for a given χB. Because Tm,B(p) is nonlinear when ΔTm > 0 (so is \({T}_{{\rm{m}}}(\frac{p}{1-\Delta })\) on the right hand side of Eq. (9)), \(\frac{p}{1-\Delta }\) must be a constant. This leads to

where a is a χB-dependent prefactor. Eq. (10) sets the pressure-dependent values of Δ to reach the same χB at p < pc. Note that Δ†(p) in Eq. (8) shows exactly the same form of pressure dependence. Therefore, Eq. (8) is actually a direct consequence of the scaling collapse in the ΔTm → 0 limit. On the other hand, Δc defined above follows Eq. (10) as well, corresponding to the minimum χB where ΔTm = 0. Therefore, the scaling collapse naturally suggests that Δ† = Δc. Consequently, for γ = 1, phase separation can occur at a given pressure p only when Δ > Δ† and ΔTm > 0.

Equation (8) also indicates that Δ† → 1 when p → 0, so ϵBB → 0 and B particles cannot feel the existence of each other. In the p → 0 limit, as long as Δ < 1 and there are still repulsions among B particles, A and B particles become identical hard particles when γ = 1 and there will be no phase separation. This is consistent with our ΔTm argument, because it is impossible to cause ΔTm > 0 in the p → 0 limit.

Glass-forming ability for γ > 1 and c B = 0.5

Inspired by the results of γ = 1, in this subsection, we will generalize the connection between χA (χB) and ΔTm to γ > 1. The results of γ = 1 are thus naturally incorporated into the generalized picture. Our arguments will be examined by simulation results of γ = 1.4 and cB = 0.5 without loss of generality. The observations of systems with γ = 1.4, cB = 0.5, and Δ = 0 presented above will then be explained. Here we also vary Δ as done for γ = 1. Because γ > 1 and A and B particles have different sizes, Δ and −Δ apparently correspond to two different systems. We thus need to restore the range of Δ to [ −1, 1].

According to Eq. (6), at fixed pressure p, the melting temperature gap ΔTm varies with Δ, so we are able to establish the functional relation between the GFA and ΔTm. Figure 4a, b show χA(ΔTm) and χB(ΔTm) for harmonic systems with γ = 1.4 and cB = 0.5 at different pressures and a given dimensionless quench rate \(\tilde{\kappa }\). All curves reach the minimum at \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}=\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\). In contrast to γ = 1 for which \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }=0\), \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) is nonzero and varies with pressure for γ = 1.4.

Here we show results for γ = 1.4 and cB = 0.5 systems with the variation of Δ at \(\tilde{\kappa }=1.22\times {10}^{-6}\). a, b χA(ΔTm) and χB(ΔTm) of solid-like states for harmonic systems at p = 10−5 (diamonds), 10−4 (triangles), 10−3 (circles), and 0.02 (squares). The curves in orange are at p > pc where Tm(p) is nonlinear, while other curves are at p < pc. c, d Scaling collapse of χA(ΔTm) and χB(ΔTm) for harmonic (solid) and RLJ (empty) systems at p = 10−5 (diamonds), 10−4 (triangles), 10−3 (circles), with ν ≈ 1.02. \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) is the value of ΔTm at which χA and χB reach the minimum, as shown in a, b. The squares with a dashed line show the violation of the scaling at p = 0.02 > pc for harmonic systems. e Comparison of melting temperature gaps \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }(p)\), \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}},{\Delta }^{* }}(p)\) with Δ = Δ* defined in Eq. (14), and ΔTm,0(p) with Δ = 0 for harmonic and RLJ systems. The inset shows Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) with Δ = Δ*.

Analogous to γ = 1, Fig. 4c, d show that for both harmonic and RLJ systems χA(ΔTm) and χB(ΔTm) curves at different pressures lower than pc can also collapse onto the same master curves, when χA and χB are plotted against \((\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}-\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* })/{p}^{\nu }\) with ν ≈ 1.02. Therefore, the scaling collapse shown in Fig. 3d for γ = 1 is just a special case with \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }=0\). When p > pc, the scaling collapse breaks down.

For γ = 1, we have also shown that there is a range of Δ where \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}=\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }=0\), i.e., −Δ† < Δ < Δ†. Then it is natural to ask whether there also exists a range of Δ within which \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}=\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) for γ > 1. Another interesting question is what determines \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\).

Because Tm(p) is linear when p < pc, according to Eqs. (6) and (7), at a given p < pc, there indeed exist a range of Δ within which ΔTm is constant, as long as both Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) are still linear. As shown in Fig. 2, γ = 1.4 leads to the separation of Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) when Δ = 0. When Δ varies from 0, Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) curves in Fig. 2 will shift in both horizontal and vertical directions simultaneously by the same amount of log10(1 + Δ) and log10(1 − Δ), respectively, in the log–log scale. According to Eqs. (4) and (5), at a given p < pc, Tm,A(p) or Tm,B(p) become nonlinear when Δ is below

or above

In the p → 0 limit, \({\Delta }_{1}^{\dagger }\) and \({\Delta }_{2}^{\dagger }\) approach −1 and 1, respectively, consistent with our previous discussions for γ = 1. At low pressures, \({\Delta }_{2}^{\dagger }\) is apparently larger than \({\Delta }_{1}^{\dagger }\). When \({\Delta }_{1}^{\dagger }\le \Delta \le {\Delta }_{2}^{\dagger }\) at a given p, ΔTm remains constant. If such a constant ΔTm is \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\), the scaling collapse shown in Fig. 4c, d also validates that \({\Delta }_{1}^{\dagger }\) and \({\Delta }_{2}^{\dagger }\) are the onsets of the growth of χA and χB and the weakening of the GFA, as observed for γ = 1.

With the increase of pressure, \({\Delta }_{1}^{\dagger }\) and \({\Delta }_{2}^{\dagger }\) approach each other, until arriving at a critical pressure

where

When p > pe, any variation of Δ normally causes the change of ΔTm, so there is no interval of Δ within which ΔTm remains constant. Therefore, the condition p < pc used above should be generally modified to p < pe. When γ = 1, Eqs. (11)–(14) lead to exactly the same results as shown in the previous subsection, with \({\Delta }_{2}^{\dagger }=-{\Delta }_{1}^{\dagger }={\Delta }^{\dagger }\), pe = pc, and Δ* = 0. For γ = 1, Δ* = 0 corresponds to the best mixing of particles with \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }=0\) at all pressures. Is it possible that Δ* defined in Eq. (14) sets \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) for γ > 1 as well?

When plugging in Δ = Δ*, Eqs. (4) and (5) turn to

Interestingly, Tm,A(p) = γ2Tm,B(p), so in the log–log scale Tm,A(p) is obtained by simply shifting Tm,B(p) upward by an amount of log10(γ2). Then both Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) become nonlinear when p > pe.

In the inset of Fig. 4e, we show Tm,A(p) and Tm,B(p) for harmonic systems with γ = 1.4 and Δ = Δ*. In the log–log scale, they are parallel along the vertical direction. We calculate the melting temperature gap \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}},{\Delta }^{* }}(p)\) at Δ = Δ*. Surprisingly, it agrees well with \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }(p)\) over the whole range of pressures studied and for both harmonic and RLJ systems, as shown in Fig. 4e. This agreement confirms our conjecture that there exists a pressure-independent Δ* at which the GFA or the degree of particle mixing is the strongest, equal to that of the hard particle counterpart. When p > pe, any deviation of Δ from Δ* causes \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}\ne \Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) and the weakening of the GFA. When p < pe, Δ* lies in the interval of \(\Delta \in [{\Delta }_{1}^{\dagger },{\Delta }_{2}^{\dagger }]\), within which \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}=\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) and the GFA can maintain the best.

Now we are able to understand the results of systems with γ = 1.4, cB = 0.5, and Δ = 0 discussed earlier. From Eqs. (11) and (12), we can see that Δ = 0 lies in \([{\Delta }_{1}^{\dagger },{\Delta }_{2}^{\dagger }]\) when p < γ−2pc, so the GFA can maintain the best. When p > γ−2pc, Δ = 0 lies outside of \([{\Delta }_{1}^{\dagger },{\Delta }_{2}^{\dagger }]\) and is away from Δ* when p > pe. Therefore, ΔTm,0, the melting temperature gap with Δ = 0, deviates from \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) and the GFA becomes worse. How much ΔTm,0 deviates from \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) determines how worse the GFA becomes. Fig. 4e also compares ΔTm,0(p) with \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }(p)\). At low pressures, they agree very well, as expected. At high pressures, ΔTm,0 deviates from \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\). For RLJ systems, the deviation is small, so the GFA is still close to the best. In contrast, for harmonic systems, the deviation significantly increases with the increase of pressure, so the GFA becomes much worse and remarkable phase separation occurs. The more essential reason of such a distinction between harmonic and RLJ systems is that harmonic systems have a much more nonlinear Tm(p).

Seen from Fig. 4a, b, the minimum values of χA and χB with Δ = Δ* are almost constant in pressure. This explains why the GFA remains constant at low pressures for harmonic and RLJ systems with γ = 1.4, cB = 0.5, and Δ = 0. More interestingly, this suggests that the GFA of hard particle systems can be maintained to high pressures far beyond the hard particle limit, by properly modulating the particle interactions and causing the interplay between geometric and energetic frustrations. To apply Δ* in Eq. (14) is one solution for binary mixtures, which should work generally for other types of particle interactions.

Dependence on c B

In previous subsections, we have focused on cB = 0.5. Fig. 5 verifies that our major findings of the pressure and particle interaction effects on the GFA hold for other values of cB. For given cB, γ, and p, we tune Δ and vary the melting temperature gap ΔTm, exactly as done for cB = 0.5.

a, b Scaling collapse of χA(ΔTm) and χB(ΔTm) of solid-like states at p = 10−5 (diamonds), 10−4 (triangles), and 10−3 (circles) quenched via the rate \(\tilde{\kappa }=1.22\times 1{0}^{-6}\). \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) is the value of ΔTm at which χA and χB reach the minimum, and ν ≈ 1.02. Three values of cB are presented: 0.3 (blue), 0.5 (red), and 0.7 (green). c Comparison of melting temperature gaps \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }(p)\) for cB = 0.3 and 0.7 and \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}},{\Delta }^{* }}(p)\) with Δ = Δ* defined in Eq. (14). They agree well, as shown in Fig. 4e for cB = 0.5. d Schematic plot of the GFA against cB on both sides of pe defined in Eq. (13) and at Δ = 0 and Δ*.

In this subsection, we take harmonic systems with γ = 1.4 as the example. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, for cB = 0.3 and 0.7, χA and χB reach the minimum at a pressure-dependent \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\). Curves of χA(ΔTm) and χB(ΔTm) at different pressures lower than pe defined in Eq. (13) can collapse well when plotted against \((\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}-\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* })/{p}^{\nu }\) with ν ≈ 1.02. Therefore, as for cB = 0.5, the GFA of the hard particle limit can be sustained with the increase of pressure, as long as ΔTm(p) remains linear.

Figure 5c reproduces the agreement between \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) and \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}},{\Delta }^{* }}\) at Δ = Δ* for cB = 0.3 and 0.7, as shown in Fig. 4e for cB = 0.5. For all values of cB studied, Δ = 0 leads to a ΔTm equal to \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\) when p < pe, as already discussed for cB = 0.5 in the previous subsection. Therefore, Δ = 0 can maintain the GFA of the hard particle limit until p = pe, above which the GFA becomes weaker. However, when Δ = Δ*, Figs. 4e and 5c show that \(\Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}},{\Delta }^{* }}\approx \Delta {T}_{{\rm{m}}}^{* }\), so the GFA of the hard particle limit can be maintained over a wide range of pressures and beyond p = pe.

Seen from Fig. 5a, b, a remarkable change with cB is the variation of the minimum values of χA and χB, reflecting the variation of the GFA of the hard particle limit with cB. The GFA can be approximately quantified by χ = χA(1 − cB) + χBcB. Fig. 5a,b suggest that the GFA of cB = 0.3 is apparently weaker than those of cB = 0.5 and 0.7, while the GFAs of cB = 0.5 and 0.7 are similar with that of cB = 0.5 seeming a little bit stronger. The GFAs in the cB = 0 and 1 limits are trivially the weakest. We also find (not shown here) that the best GFA associated with the minimum χ occurs between cB = 0.5 and 0.7.

The evolution of the GFA with the increase of cB characterized in our work is consistent with previous results of binary mixtures of hard disks with γ = 1.4 from the calculations of the interface energy23. Based on our results, we can now qualitatively extend the cB dependence of the GFA to various pressures. In Fig. 5d, we schematically plot the GFA against cB for different pressures and for Δ = 0 and Δ*, respectively. For Δ = 0, it can be expected that the GFA(cB) curve of the hard particle limit can be maintained until p = pe. When p > pe and the GFA becomes weaker, the whole GFA curve will shift down with the increase of pressure. For Δ = Δ*, we would expect that the GFA(cB) curve of the hard particle limit can be maintained beyond p = pe.

In the perspective of the empirical argument of the connection between the GFA and eutectic point, the GFA can be evaluated from the depression of the equilibrium melting temperature with the variation of cB6,23. However, the argument may not be easily applied to compare the GFAs at different pressures or densities, purely from the comparison of melting temperatures. One may then suggest to perform the calculations of the equilibrium phase diagram and the energy barriers (and the rate) of the nucleation of corresponding crystals to evaluate the GFA, as done for binary mixtures of hard disks23,50. Because we have multiple parameters, cB, p, and Δ at fixed γ, it would be a rather difficult task.

Here we realize the comparison of the GFAs over pressures, interactions, and particle compositions in a much simpler way. The key is the finding of the underlying connection between the GFA and the cB-independent melting temperature gap between species derived from the simple conversion of units. The melting temperatures adopted here are not the actual ones from direct simulations or calculations of equilibrium systems, which should depend on not only p but also cB for given γ and Δ, but they turn out to work well to reveal the pressure and interaction dependence. Another important finding is Δ*, which suggests an energy strategy to fight against the weakening of the GFA caused by the softness of particles.

Although we do not show exact results of the equilibrium phase diagram and melting temperatures in the complicated parameter space, the schematic plots in Fig. 5d already to some extend indirectly reflect the pressure and interaction evolution of the equilibrium phase diagram in the T − cB plane. It would be expected that when p < pe the phase diagrams at various pressures look similar for Δ = 0 and Δ*, only that the melting temperatures grow linearly with the pressure. When p > pe, the phase diagram starts to deviate for Δ = 0, while the similarity may be still maintained for Δ = Δ*.

Discussion

By investigating the pressure and interaction dependence of the GFA, we find similarities and distinctions between two types of widely studied model glass-formers, binary mixtures of harmonic and RLJ particles with γ = 1.4, cB = 0.5, and Δ = 0. We focus on the energetic frustration, taking the hard particle limit as the reference. For a given γ, the GFA is the best in the hard particle limit, purely determined by geometric frustration. The involvement of the potential energy normally weakens the GFA of hard particles. We find that the GFAs of both harmonic and RLJ systems remain constant and identical at low pressures, but bifurcate at high pressures. In contrast to RLJ systems which still maintain an almost constant GFA at high pressures, significant phase separation occurs in harmonic systems.

With the variation of both γ and Δ, we come up with a generalized picture, which explains the pressure and interaction dependence of the GFA. Our major findings include (i) the non-equilibrium GFA of binary mixtures of soft particles is connected to the equilibrium melting temperature, (ii) the GFA of the hard particles can be maintained to high pressures with a proper modulation of the particle interaction such as using Δ* in Eq. (14), and (iii) melting temperatures more linear in pressure are better to suppress phase separation and maintain a good GFA. We find that these results are valid for different values of cB. In combination of the cB dependence studied as well in previous approaches and the pressure and interaction dependence studied in this work, we are able to have a much more comprehensive picture of the GFA of binary mixtures of soft particles. Harmonic and RLJ potentials studied here are rather different, but their behaviors can both be understood by the same picture. Moreover, the derivations in this work do not aim at any specific interaction. Therefore, we expect that our findings are valid to other types of interaction.

Note that in this work ϵAA, ϵBB, and ϵAB are connected by the variable Δ and are thus not independent. Therefore, the major conclusions made here may not be directly generalized to other conditions, for example, when all three ϵ’s are independence of each other. However, the robust and consistent evidence shown in this work suggests that the underlying connections between the GFA and the melting temperature should not be a coincidence. Follow-up studies are required to find out whether a more general picture can be established.

Since the melting temperature affects the GFA, it is then straightforward to expect that it also plays some role in dynamics of supercooled liquids. It is interesting to know whether A and B particles exhibit different dynamics related to their melting temperature difference. We are also curious about how the dynamics change when Δ varies from 0 to Δ* with the best GFA, from which we may reveal some underlying connections between the GFA and dynamical properties of glass-formers, such as kinetic fragility and dynamic heterogeneity.

Methods

System information

Our systems contain N/2 A and N/2 B particles with the same mass m and a size ratio γ defined earlier. Periodic boundary conditions are applied in all directions. We consider two types of particle interactions, harmonic:

and repulsive Lennard-Jones (RLJ):

where rij and σij are the separation between particles i and j and sum of their radii, ϵij is the characteristic energy scale, and Θ(x) is the Heaviside step function. We set the units of mass, energy, and length to be m, ϵAB, and σB, so the units of time and temperature are \({\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}{m}^{0.5}{\epsilon }_{{\rm{AB}}}^{-0.5}\) and \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{AB}}}{k}_{{\rm{B}}}^{-1}\) with kB being the Boltzmann constant.

Dimensionless quench rate

In this work, we compare the GFA over a wide range of pressures from 10−5 to above 0.1 and thus have to confront the challenge to choose a reasonable quench rate. To our knowledge, this issue has not been seriously considered, because people rarely compare the GFAs at different pressures.

It has been shown that, when glass-forming liquids are quickly quenched to T = 0, the properties of the resultant inherent structures, e.g., potential energy and stability, depend on the parent temperature Tp prior to the quench52,53,54,55. For glass-forming liquids, there are two characteristic temperatures, the onset temperature Tonset and the glass transition temperature Tg40,55. When Tp > Tonset and the liquids still exhibit the Arrhenius relaxation behavior, the potential energy of the inherent structures does not vary much with Tp. When Tg < Tp < Tonset and the liquids are supercooled and exhibit super-Arrhenius behavior, the potential energy of the inherent structures decreases with the decrease of Tp. Previous results have suggested that Tonset is around 2Tg40.

In our study, we start with an equilibrium liquid above Tonset and apply a quench rate κ = δT/Δt. Apparently, how long the system stays in the temperature window, (Tg, Tonset), is crucial to the structures and properties of the final solid-like states. In contrast, above Tonset or below Tg, the system is either an equilibrium liquid or a glass with extremely slow structural relaxation, so how long the system stays at T > Tonset and T < Tg in the accessible time scales should not significantly affect the final solid-like state.

Previous studies have shown that Tg ~ p at low pressures for systems studied in this work with γ = 1.4 and Δ = 030. If we use the same quench rate κ for all pressures, the time for the system to stay in the supercooled regime, (Tg, Tonset), is (Tonset − Tg)/κ ~ p/κ. Compared with high-pressure systems, the low-pressure systems almost undergo no time in the supercooled regime, which is unfair for them to explore lower-energy inherent structures. Therefore, to compensate this loss at low pressures and give systems at quite different pressures comparable chances to explore lower-energy inherent structures, we need to let κ ~ p. This leads to an updated quench rate \({\kappa }^{* }=\kappa /(p{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{d}/{k}_{{\rm{B}}})\), where d is the dimension of space. This is actually to nondimensionlize the temperature step δT in the expression of κ by \(p{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{d}/{k}_{{\rm{B}}}\).

Moreover, it has also been shown that the structural relaxation time τ of the supercooled liquids studied in this work satisfies the scaling at low pressures30: \(\tau \sqrt{p{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{d-2}/m}=F({k}_{{\rm{B}}}T/p{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{d})\), where F(x) is the scaling function. Therefore, in order for systems at different pressures to undergo comparable structural relaxations in the supercooled liquid regime, the quench rate is required to be further divided by p1/2. This is actually to nondimensionlize the time duration Δt in the expression of κ by \({(p{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{d-2}/m)}^{-1/2}\).

Then we finally obtain a dimensionless quench rate \(\tilde{\kappa }={\kappa }^{* }/\sqrt{p{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{d-2}/m}=\frac{{k}_{{\rm{B}}}{m}^{1/2}}{{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{3d/2-1}}\frac{\kappa }{{p}^{3/2}}\). For two-dimensional systems mainly studied in this work, \(\tilde{\kappa }=\frac{{k}_{{\rm{B}}}{m}^{1/2}}{{\sigma }_{{\rm{B}}}^{2}}\frac{\kappa }{{p}^{3/2}}\). By using the same \(\tilde{\kappa }\) at different pressures, we are able to compare the GFAs of systems with the pressure varying over several orders of magnitude. This is particularly crucial to compare the low-pressure regimes where both the glass transition and melting temperatures are linear in pressure. The robust scaling collapse of χ(ΔTm) curves strongly validates the use of \(\tilde{\kappa }\). When \(\tilde{\kappa }\) is fixed, κ ~ p−3/2, so the computational cost dramatically increases with the decrease of pressure. As a compromise, we use larger values of \(\tilde{\kappa }\) when focusing on the low-pressure systems in Figs. 3–5 than those for higher pressures in Fig. 1.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The computer codes of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Debenedetti, P. G. & Stillinger, F. H. Supercooled liquids and the glass transition. Nature 410, 259–267 (2001).

Berthier, L. & Biroli, G. Theoretical perspective on the glass transition and amorphous materials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 587–645 (2011).

Liu, A. J. & Nagel, S. R. Nonlinear dynamics: jamming is not just cool any more. Nature 396, 21–22 (1998).

O’Hern, C. S., Silbert, L. E., Liu, A. J. & Nagel, S. R. Jamming at zero temperature and zero applied stress: the epitome of disorder. Phys. Rev. E 68, 011306 (2003).

Torquato, S. & Stillinger, F. H. Jammed hard-particle packings: from Kepler to Bernal and beyond. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2633–2672 (2010).

Tanaka, H. Bond orientational order in liquids: towards a unified description of water-like anomalies, liquid-liquid transition, glass transition, and crystallization. Eur. Phys. J. E Soft Mater. 35, 113 (2012).

Bates, F. S. Polymer-polymer phase behavior. Science 251, 898–905 (1991).

Jaeger, H. M., Nagel, S. R. & Behringer, R. P. Granular solids, liquids, and gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 68, 1259–1273 (1996).

Moreo, A., Yunoki, S. & Dagotto, E. Phase separation scenario for manganese oxides and related materials. Science 283, 2034–2040 (1999).

Erlebacher, J., Aziz, M. J., Karma, A., Dimitrov, N. & Sieradzki, K. Evolution of nanoporosity in dealloying. Nature 410, 450–453 (2001).

Balaza, A. C., Emrick, T. & Russell, T. P. Nanoparticle polymer composites: where two small worlds meet. Science 314, 1107–1110 (2006).

Palacci, J., Sacanna, S., Steinberg, A. P., Pine, D., Chaikin, J. & Living, P. M. crystals of light-activated colloidal surfers. Science 339, 936–940 (2013).

Li, P. L., Banjade, S., Cheng, H. C., Kim, S. & Chen, B. et al. Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signalling proteins. Nature 483, 336–340 (2012).

Biben, T. & Hansen, J. P. Phase separation of asymmetric binary hard-sphere fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 2215–2218 (1991).

Hynninen, A.-P., Thijssen, J. H. J., Vermolen, E. C. M., Dijkstra, M. & van Blaaderen, A. Self-assembly route for photonic crystals with a bandgap in the visible region. Nat. Mater. 6, 202–205 (2007).

Shechtman, D., Blech, I., Gratias, D. & Cahn, J. W. Metallic phase with long-range orientational order and no translational symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 1951–1953 (1984).

Xi, X. K., Li, L. L., Zhang, B., Wang, W. H. & Wu, Y. Correlation of atomic cluster symmetry and glass-forming ability of metallic glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 095501 (2007).

Li, Y., Guo, Q., Kalb, J. A. & Thompson, C. V. Matching glass-forming ability with the density of the amorphous phase. Science 322, 1816–1819 (2008).

Fujita, T., Konno, K., Zhang, W., Kumar, V. & Matsuura, M. et al. Atomic-scale heterogeneity of a multicomponent bulk metallic glass with excellent glass forming ability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 075502 (2009).

Bendert, J. C., Gangopadhyay, A. K., Mauro, N. A. & Kelton, K. F. Volume expansion measurements in metallic liquids and their relation to fragility and glass forming ability: an energy landscape interpretation. Phys. rev. Lett. 109, 185901 (2012).

Wu, Z. W., Li, M. Z., Wang, W. H. & Liu, K. X. Hidden topological order and its correlation with glass-forming ability in metallic glasses. Nat. Commun. 6, 6035 (2014).

Ninarello, A., Berthier, L. & Coslovich, D. Models and algorithms for the next generation of glass transition studies. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021039 (2017).

Russo, J., Romano, F. & Tanaka, H. Glass forming ability in systems with competing orderings. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021040 (2018).

Dijkstra, M., van Roij, R. & Evans, R. Phase diagram of highly asymmetric binary hard-sphere mixtures. Phys. Rev. E 59, 5744–5771 (1999).

Dijkstra, M., van Roij, R. & Evans, R. Phase behavior and structure of binary hard-sphere mixtures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 2268–2271 (1998).

Biben, T., Bladon, P. & Frenkel, D. Depletion effects in binary hard-sphere fluids. Matter 8, 10799–10821 (1996).

Dinsmore, A. D., Yodh, A. G. & Pine, D. J. Phase diagrams of nearly-hard-sphere binary colloids. Phys. Rev. E 52, 4045–4057 (1995).

Imhof, A. & Dhont, J. K. G. Experimental phase diagram of a binary colloidal hard-sphere mixture with a large size ratio. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1662–1665 (1995).

Frenkel, D. Entropy-driven phase transitions. Phys. A 263, 26–28 (1999).

Xu, N., Haxton, T. K., Liu, A. J. & Nagel, S. R. Equivalence of glass transition and colloidal glass transition in the hard-sphere limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 245701 (2009).

Wang, X., Zheng, W., Wang, L. & Xu, N. Disordered solids without well-defined transverse phonons: the nature of hard-sphere glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 035502 (2015).

Donev, A., Stillinger, F. H. & Torquato, S. Configurational entropy of binary hard-disk glasses: nonexistence of an ideal glass transition. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 124509 (2007).

Coslovich, D., Ozawa, M. & Berthier, L. Local order and crystallization of dense polydisperse hard spheres. Matter 30, 144004 (2018).

Miller, W. L. & Cacciuto, A. Two-dimensional packing of soft particles and the soft generalized Thomson problem. Soft Matter 7, 7552–7559 (2011).

Miyazaki, R., Kawasaki, T. & Miyazaki, K. Cluster glass transition of ultrasoft-potential fluids at high density. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 165701 (2016).

Pàmies, J. C., Cacciuto, A. & Frenkel, D. Phase diagram of Hertzian spheres. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 044514 (2009).

Zu, M., Tan, P. & Xu, N. Forming quasicrystals by monodisperse soft core particles. Nat. Commun. 8, 2089 (2017).

Xu, N. Phase behaviors of soft-core particle systems. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 37, 1065–1082 (2019).

Pedersen, U. R., Schrøder, T. B. & Dyre, J. C. Repulsive reference potential reproducing the dynamics of a liquid with attractions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 157801 (2010).

Berthier, L. & Tarjus, G. The role of attractive forces in viscous liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 214503 (2011).

Ingebrigtsen, T. S., Schrøder, T. B. & Dyre, J. C. What is a simple liquid? Phys. Rev. X 2, 011011 (2012).

Wang, L. & Xu, N. Probing the glass transition from structural and vibrational properties of zero-temperature glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 055701 (2014).

Khrapak, S. A. & Morfill, G. E. Accurate freezing and melting equations for the Lennard-Jones system. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 094108 (2011).

Berthier, L., Moreno, A. J. & Szamel, G. Increasing the density melts ultrasoft colloidal glasses. Phys. Rev. E 82, 060501 (2010).

Zhao, C., Tian, K. & Xu, N. New jamming scenario: from marginal jamming to deep jamming. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 125503 (2011).

Schmiedeberg, M. Multiple reentrant glass transitions of soft spheres at high densities: monotonicity of the curves of constant relaxation time in jamming phase diagrams depending on temperature over pressure and pressure. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter. Phys. 87, 052310 (2013).

Zu, M., Liu, J., Tong, H. & Xu, N. Density affects the nature of the hexatic-liquid transition in two-dimensional melting of soft-core systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 085702 (2016).

Wang, L. & Xu, N. Non-monotonic pressure dependence of the dynamics of soft glass-formers at high compressions. Soft Matter. 8, 11831–11838 (2012).

Likos, C. M. Effective interactions in soft condensed matter physics. Phys. Rep. 348, 267–439 (2001).

Russo, J. & Wilding, N. B. Disappearance of the hexatic phase in a binary mixture of hard disks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 115702 (2017).

Tong, H., Tan, P. & Xu, N. From crystals to disordered crystals: a hidden order-Disorder transition. Sci. Rep. 5, 15378 (2015).

Sastry, S., Debenedetti, P. G. & Stillinger, F. H. Signatures of distinct dynamical regimes in the energy landscape of a glass-forming liquid. Nature 393, 554–557 (1998).

Helfferich, J., Lyubimov, I., Reid, D. & de Pablo, J. J. Inherent structure energy is a good indicator of molecular mobility in glasses. Soft Matter 12, 5898–5904 (2016).

Wang, L., Ninarello, A., Guan, P., Berthier, L., Szamel, G. & Flenner, E. Low-frequency vibrational modes of stable glasses. Nat. Commun. 10, 26 (2019).

Brumer, Y. & Reichman, D. R. Mean-field theory, mode-coupling theory, and the onset temperature in supercooled liquids. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter. Phys. 69, 041202 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ludovic Berthier for bringing us attention to the micro-phase separation in binary mixtures of harmonic particles at high densities, which stimulates us to perform this study. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant No. 11734014. We also thank the Supercomputing Center of University of Science and Technology of China for the computer time.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.X. designed the project. Y.N. performed the simulations. Y.N., J.L., J.G. and N.X. analyzed the data. Y.N. and N.X. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nie, Y., Liu, J., Guo, J. et al. Connecting glass-forming ability of binary mixtures of soft particles to equilibrium melting temperatures. Nat Commun 11, 3198 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16986-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16986-z

This article is cited by

-

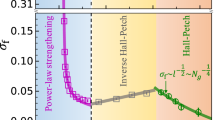

A regime beyond the Hall–Petch and inverse-Hall–Petch regimes in ultrafine-grained solids

Communications Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.