Abstract

Since the discovery of the Verwey transition in magnetite, transition metal compounds with pyrochlore structures have been intensively studied as a platform for realizing remarkable electronic phase transitions. We report on a phase transition that preserves the cubic symmetry of the β-pyrochlore oxide CsW2O6, where each of W 5d electrons are confined in regular-triangle W3 trimers. This trimer formation represents the self-organization of 5d electrons, which can be resolved into a charge order satisfying the Anderson condition in a nontrivial way, orbital order caused by the distortion of WO6 octahedra, and the formation of a spin-singlet pair in a regular-triangle trimer. An electronic instability due to the unusual three-dimensional nesting of Fermi surfaces and the strong correlations of the 5d electrons characteristic of the pyrochlore oxides are both likely to play important roles in this charge-orbital-spin coupled phenomenon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding the phase transitions of crystalline solids is a central issue in materials science. Electronic phase transitions in transition metal compounds with pyrochlore structures, made of three-dimensional networks of corner-sharing tetrahedra, have posed challenging questions in materials science since their discovery. The classical example is magnetite Fe3O4, which was reported to show a metal−insulator transition accompanied by a charge order of Fe at 119 K, called the Verwey transition1. Although many studies of this transition have been made, full understanding of its ground state has not yet been reached, and relevant studies based on new perspectives are continuing2. Recently, metal−insulator transitions accompanied by all-in-all-out-type magnetic order in 5d oxides, such as Cd2Os2O7 and Nd2Ir2O7, have attracted considerable attention3,4,5, in terms of a ferroic order of extended magnetic octapoles and the formation of Weyl fermions in solids3,6,7,8,9. As described above, rich physics appears in pyrochlore systems, which might be caused by the high crystal symmetry and a large number of atoms in a unit cell, resulting in the self-organization of d electrons in various forms.

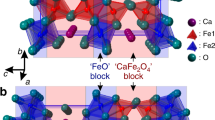

In this study, we report self-organization of 5d electrons at the electronic phase transition of β-pyrochlore oxide CsW2O6, discovered by using high-quality single crystals. CsW2O6 was first synthesized by Cava et al., which was reported to have a cubic lattice with Fd\(\bar 3\)m space group at room temperature10. In this structure, W atoms form a pyrochlore structure and have 5.5+ valence with a 5d0.5 electron configuration. Electrical resistivity measurement of polycrystalline samples suggested that a metal−insulator transition occurs at 210 K11. The crystal structure of the insulating phase was reported to have orthorhombic Pnma space group11; however, this space group was suggested to be incorrect by a theoretical study12. Electronic structure calculations on the Fd\(\bar 3\)m phase pointed out that there is a strong nesting of the Fermi surfaces, which induces a symmetry lowering to the P4132 space group. Recent photoemission experiments of thin films suggested that the valence of W in the insulating phase disproportionates into 5+ and 6+13.

Results

A phase transition at 215 K

We prepared single crystals of CsW2O6 (Fig. 1a) and W-deficient CsW1.835O6 in a quartz tube (see “Method” section). As shown in Fig. 1b, the electrical resistivity, ρ, of a single crystal of CsW2O6 strongly increases below Tt = 215 K with decreasing temperature, as in the cases of a polycrystalline sample and a thin film11,13. This increase is accompanied by a small but obvious temperature hysteresis, indicating that a first-order phase transition occurs at Tt. Here, the phases above and below Tt are named Phase I and II, respectively. The magnetic susceptibility, χ, shown in Fig. 1b strongly decreases below Tt, which is identical to the polycrystalline case11. However, the line widths of the 133Cs-NMR spectra in Phase II do not show any significant broadening compared to those in Phase I, as shown in Fig. 1f, indicating that the decrease of χ in Phase II is not caused by antiferromagnetic order.

All the experimental data in this figure except for the heat capacity were obtained using single crystals. a A single crystal of CsW2O6. b Temperature dependence of the electrical resistivity (upper) and magnetic susceptibility (lower). The inset of the upper panel shows the optical conductivity at room temperature deduced from the reflectivity using the Kramers–Kronig transformation40. The inset of the lower panel shows the heat capacity divided by temperature measured by using a polycrystalline sample. c Single-crystal XRD patterns at 250 (Phase I, right) and 100 K (Phase II, left). The pale blue and white squares indicate the positions of allowed and forbidden reflections, respectively, for the Fd\(\bar 3\)m space group. d Temperature dependence of the lattice constant and intensity of (−2, −5, −3) reflection estimated with the single-crystal XRD data. e Polarization dependence of the (111) Raman spectra measured at room temperature (Phase I, right) and 100 K (Phase II, left). f Temperature dependence of the 133Cs-NMR spectra measured in a magnetic field of 8 T applied along [001].

Figure 1c shows single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of CsW2O6 measured at 250 (Phase I) and 100 K (Phase II). Each of the diffraction spots at 250 K were indexed on the basis of a cubic cell of a = 10.321023(7) Å with Fd\(\bar 3\)m space group, consistent with previous reports10,11. In the diffraction pattern at 100 K, more diffraction spots appear. All these spots were indexed on the basis of cubic P213 space group with a lattice constant of a = 10.319398(6) Å, which is almost identical to a of Phase I. This change of diffraction spots occurs at Tt, as seen in the temperature dependence of the intensity shown in Fig. 1d. Moreover, in Phase II, diffraction spots do not split into multiple spots nor do they change their shapes, even in the high-angle region, as shown in Fig. 1c. Laue class and crystal system determined by the observed reflections clearly indicated that a structural change that preserves the cubic symmetry occurs at Tt and the Phase II has the Laue class of m\(\bar 3\) (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3). As seen in the polarization dependence of the Raman spectra of (111) surface measured at 100 K (Phase II) and room temperature (Phase I) shown in Fig. 1e, the spectra of Phase II are independent of the polarization angle same as in Phase I, indicating the presence of three-fold rotational symmetry perpendicular to (111), consistent with the inferred cubic symmetry. These results mean that the Pnma structural model proposed based on the powder diffraction data is incorrect11. In addition, the proposed Pnma structure has a pseudo-tetragonal distortion of approximately 0.03%, which was not observed in the present study, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 4. This result is also supported by the 133Cs-NMR data on the single crystals of CsW2O6 discussed below. In a polycrystalline sample of CsW2O6, W-deficient CsW1.835O6 always exists as an impurity phase. We believe that the fact that the single crystals of CsW2O6 and W-deficient CsW1.835O6 were separately prepared and the diffraction and physical property measurements were performed by using the high-quality single crystals played a crucial role for elucidating the nature of Phase II. The crystallographic parameters of CsW2O6 at 250 and 100 K determined by the structural analyses are shown in Supplementary Tables 2 and 4, respectively. Physical properties and crystallographic parameters of CsW1.835O6 are also shown in Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 6. A point to be noted in the Raman spectra shown in Fig. 1e is a peak appeared at ~55 cm−1, reflecting the rattling of Cs+ ions14 (see Supplementary Note 6).

Crystal structure of phase II

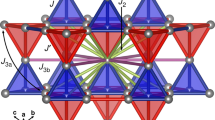

Here we discuss the solved crystal structure of Phase II. In Phase I with the Fd\(\bar 3\)m space group, each of Cs, W, and O atoms occupies one site, where the Cs and W atoms form diamond and pyrochlore structures, respectively (Fig. 2a). In Phase II with the P213 space group, the Cs atoms occupy two different sites and form a zinc-blende structure, as shown in Fig. 2b. This was further confirmed by the two peaks in 133Cs-NMR spectra correspond to the two Cs sites, which appear as a small peak split in the 200, 160, and 125 K data shown in Fig. 1f. On the other hand, W atoms occupy two sites with a 1:3 ratio in Phase II, as shown in Fig. 2b, c, which is incompatible with the W5+–W6+ charge order with a 1:1 ratio of W5+ and W6+ atoms. According to the bond valence sum calculation for the W–O distances determined from single-crystal XRD analyses15, the valences of the W(1) and W(2) atoms are estimated to be 6.07(3) and 5.79(3) at 100 K (Phase II), respectively. Considering that the reliable bond valence sum parameters of W6+ are available but those of W5+ are not, it is natural for the W(1) atoms to be W6+ without 5d electrons. In this case, the valence of the W(2) atoms becomes 5.33+ with 5d2/3 electron configurations. The above discussion indicates that a charge order with a noninteger valence occurs at Tt. In fact, single crystals of W-deficient CsW1.835O6, where all W atoms have 6+ valence without 5d electrons, do not show the transition at Tt (see Supplementary Fig. 6).

a, b Crystal structures of the W and Cs sublattices of Phase I (T > 215 K) and II (90 < T < 215 K). The purple triangles indicate the W3 trimers. c Hyperkagome structure of W(2) atoms in Phase II. d Thermal ellipsoids of the oxygen atoms at 100 K (Phase II). e W–O bond lengths in a W(2)O6 octahedron at 100 K (Phase II). f Schematic picture of the occupied 5d orbitals in Phase II. The lower left and right panels indicate the W3O15 units forming the larger and smaller triangles made of W atoms, respectively. The small triangle corresponds to the W3 trimer. In the right panel, the 2p orbitals of the bridging oxygen atoms are also shown.

In Phase II, the W(2) atoms form a three-dimensional network of small and large regular triangles, which are alternately connected by sharing their corners, as shown in Fig. 2b. Although the difference of sizes between the large and small triangles are about 2%, arrangements of the occupied 5d orbitals are completely different between them, resulting in a W3 trimer on a small triangle, as discussed later. If there was no alternation of the W3 triangles, the W sublattice would possess a hyperkagome structure16, as shown in Fig. 2c. The presence of the alternation indicates that ‘breathing hyperkagome’ structure is formed during Phase II17.

Discussion

The charge order in Phase II of CsW2O6 is interesting in that the “Anderson condition” is maintained in an unusual way. Anderson pointed out that magnetite has an infinite number of charge ordering patterns, where all the tetrahedra in a pyrochlore structure have the same total charge, i.e., so-called Anderson condition, and this macroscopic degeneracy strongly suppresses the transition temperature of the Verwey transition18. This situation can be interpreted as geometrical frustration of electronic charges. However, not only magnetite, but also other mixed-valent pyrochlore systems, such as CuIr2S4 and AlV2O4, were reported to show a charge order that violated the Anderson condition19,20,21,22,23. In them, the energy gained by σ bonding between d orbitals of adjacent atoms was expected to be large enough to compensate for the loss of Coulomb energy due to violation of the Anderson condition, because spinel-type compounds comprised the edge-shared octahedra24,25. In contrast, the charge order of CsW2O6 satisfies the Anderson condition, where each tetrahedron consists of three W5.33+ and one W6+ atoms. However, this charge order is different to that proposed by Anderson and Verwey, which has integer valences with a 1:1 ratio18,26. Hyperkagome-type orders often appear in pyrochlore systems with a 1:3 ratio of two kinds of atoms, such as the uuud spin structure of the half magnetization plateau of Cr spinel oxides and the atomic order in B-site ordered spinel oxides A2BB'3O827,28,29. As far as we are aware, CsW2O6 is the only example to show a hyperkagome-type order where the formation of this order is nontrivial. It is an alternative way to relieve the geometrical frustration based on the traditional problem in condensed matter physics.

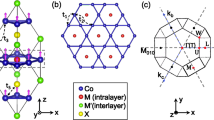

Why does such unusual charge order occur in CsW2O6? A key to understand this question is hidden in Fermi-surface instability of the electronic band structure of Phase I. The left panel of Fig. 3 shows the band structure of Phase I and the right panel shows four overlapping band structures, which are depicted after the parallel shifts of electronic bands corresponding to a change of the primitive cell from face-centered cubic to primitive cubic. As seen in the right panel of Fig. 3, band crossing occurs close to all points where electronic bands touch the Fermi energy EF, suggesting that the Fermi surfaces are well nested by the parallel shift of the electronic bands, corresponding to the loss of centering operations. This situation can be called “three-dimensional nesting”, which means that a large electronic energy is gained by the structural change associated with the above symmetry change. The electronic instability and nesting of the Fermi surfaces in Phase I was also pointed out in the previous study12. It is quite rare for cubic compounds to have such well-nested Fermi surfaces, except for the filled-skutterudite PrRu4P12. PrRu4P12 shows a metal−insulator transition accompanied by a structural change from body-centered cubic to primitive cubic30,31 and has a Fermi-surface instability corresponding to this structural change32.

The left panel is the electronic band structure based on the Brillouin zone of the face-centered cubic lattice, which is shown by black solid lines in the center panel. In the right panel, four band structures based on four primitive cells, which are shown by red, brown, pale blue, and blue solid lines in the center panel, respectively, overlap in the graph.

The above discussion indicates that three-dimensional nesting is likely an essential ingredient for the 215 K transition. However, if it is the only driving force, a structural change from Fd\(\bar 3\)m to P4132 or P4332, which are maximal non-isomorphic subgroups with primitive cubic lattices, must occur, as also discussed in the previous theoretical study12. In this case, the W(2) atoms should form a uniform hyperkagome structure. This study also suggested that the band gap does not open at the Fermi energy in the P4132 and P4332 cases12, which is inconsistent with the observed insulating nature of the Phase II. In reality, the space group of Phase II is P213, which is a subgroup of P4132 and P4332, and W(2) atoms form a breathing hyperkagome structure, where the size of a small triangle is 2% smaller than that of a large triangle. The P213 space group is also different from orthorhombic P212121 proposed in ref. 12. In addition, whether the band structure calculated with the structural parameters of Phase II is gapped or not might be important for understanding of the underlying physics of the phase transition. At present, however, the calculated results with an overlapped gap have not yet completely converged, due to the large number of atoms in a primitive unit cell.

Phenomenologically, orientation of the occupied 5d orbitals is important for the symmetry lowering from P4132/P4332 (uniform hyperkagome) to P213 (breathing hyperkagome). For a W(2)O6 octahedron of Phase II shown in Fig. 2e, the two apical W(2)-O bonds (gray) are 3–8% shorter than the other four equatorial bonds (blue), indicating that the octahedron is uniaxially compressed. This compression is comparable to the typical Jahn–Teller distortion in t2g electron systems, and the 5d orbitals lying in this equatorial plane should be occupied by electrons. Schematic pictures of the occupied 5d orbitals in small and large triangles are shown in the right and left panels of Fig. 2f, respectively. There is considerable overlap between the occupied 5d orbitals in the small triangle via an O 2p orbital. In contrast, there is little overlap in a large triangle, indicating that two electrons in three W(2) atoms are confined in a W3 trimer in the small triangle.

This regular-triangle trimer formation might be understood as a three-centered-two-electron (3c2e) bond formation, where two electrons are accommodated in a molecular orbital made of three W 5d orbitals (and the O 2p orbitals hybridize with them). In this case, it is natural to have a nonmagnetic ground state. This regular-triangle trimer is essentially different to those of famous LiVO2 and LiVS2, where two electrons are shared by two V atoms along each side of a triangle33,34,35. Na3Ir3O8 was pointed out to have regular-triangle Ir3 molecules formed on a hyperkagome structure36. However, the Ir3 molecules are connected each other, which is essentially different from the fact that the W3 trimers in CsW2O6 are isolated, as seen in Fig. 2b. Stabilization of the electronic energy by the formation of multiple-centered bonds, where a few electrons are shared by many atoms, often occurs in electron-deficient molecules or cluster compounds37. To our knowledge, CsW2O6 is the only example where this type of bond formation appears as a phase transition. The formation of regular-triangle trimers itself is also surprising, because the 3c2e bond usually has a bent shape. According to previous reports, only the H3+ ion has a regular-triangle shape in triatomic molecules formed by the 3c2e bond. Moreover, H3+ is an interstellar material and it is not stable on Earth, having been observed in astronomical spectra38.

This regular-triangle shape of the trimer might be related to its internal structure, a part of which appears in the atomic displacement parameters (ADPs). As shown in Fig. 2d, the O atoms bridging W(2) atoms in a W3 trimer (O(1) site) in Phase II have large ADPs perpendicular to the W-W bond. The ADPs of the other O atoms are typical values, suggesting that the ADPs of the O(1) site do not increase by the structural instability of the β-pyrochlore structure, but rather by the electronic instability of the trimer. The large ADPs perpendicular to the W-W bond indicate that there is a strong fluctuation that changes the W(2)–O(1)–W(2) angle. In pyrochlore oxides, the change of this angle has a large effect on the orbital overlap39. Therefore, this fluctuation can be interpreted as a strong fluctuation to a state in which one of the W-W bonds becomes stronger, or in the extreme, to a state in which a W2 dimer is formed. Since ADPs of the W(2) site have typical values, it is unlikely that the dimers statically and randomly form on the trimers. Instead, the dimer might dynamically fluctuate or resonate. For a complete understanding of the internal structure of the trimers, it would be desirable to directly observe their dynamical properties in a future study.

For the formation of this trimer, electron correlation of the 5d electrons in CsW2O6 might be another essential factor. The optical conductivity spectra of CsW2O6 measured at room temperature deduced from the reflectivity using the Kramers–Kronig transformation40, shown in the inset of Fig. 1b, exhibit a broad peak at around 0.6 eV. Extrapolation of the spectra to zero frequency coincides with ρ = 3 mΩ cm at room temperature (the main panel of Fig. 1b). This result indicates that there is no, or negligibly small, Drude contribution in the spectra, and the conducting carriers are trapped by something with an energy scale of 0.6 eV, resulting in the loss of coherency, which is supported by dρ/dT < 0 in Phase I. Absence of a peak in the far-infrared region indicates that this localization is not due to disorder, but might be reminiscent of the spectra of lightly-carrier-doped Mott insulators41,42,43. As seen in the band structure shown in Fig. 3a, there are flat parts near EF and the energy bands have a narrow width of 0.7 eV, suggesting the presence of a strong electron correlation for a 5d electron system. In 5d or 4d pyrochlore oxides, the 5d/4d electrons often have moderately-strong electron correlation because of the small orbital overlap due to the bent metal–oxygen–metal bonds. In fact, the optical conductivities of Nd2Ir2O7 and Sm2Mo2O7 indicate the presence of incoherent d electrons9,44, similar to the case of CsW2O6. As a result, 5d pyrochlore oxides often show an electronic phase transition with the order of electronic degrees of freedom. Nd2Ir2O7 with Jeff = 1/2 and Cd2Os2O7 with S = 3/2, without charge and orbital degrees of freedom, showed a magnetic order accompanied by a metal−insulator transition3,4,5. Instead, for CsW2O6, the trimers are formed with the help of the electron correlation as in the case of LiVO245. In the trimer of CsW2O6, the two 5d electrons form a spin-singlet pair, resulting in the nonmagnetic and insulating ground state. This is an alternative type of self-organization of d electrons realized in a strongly correlated 5d oxide.

Finally, we will discuss another structural transition at 90 K. Phase II looks like a ground state, where most of the degrees of freedom have been lost, but surprisingly another phase transition occurs at 90 K. By indexing the diffraction spots in the single-crystal XRD data of Phase II, the crystal structure below 90 K, named Phase III, was found to have monoclinic P21 space group with a four-times-larger (2 × 1 × 2) unit cell than that of Phase II, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The procedure performed for the determination of the size of unit cell and space group of Phase III is described in Supplementary Notes 2 and 3. As seen in the inset of Fig. 1b, the heat capacity divided by temperature, C/T, shows a small but obvious peak, which corresponds to the entropy change of ~0.4 J K−1 mol−1, at ~90 K, indicating the presence of a bulk phase transition. The P21 space group is different from Pnma and P212121 space groups proposed in the previous studies11,12. The atomic positions in Phase III have not yet been determined, because of tiny monoclinic distortion and domain formation, but it is clear that the structural change at 90 K is small, as seen in Supplementary Fig. 2. In addition, χ does not exhibit an anomaly at 90 K. These results suggest that the 90 K transition is not caused by the spin, charge, and/or orbital order different to the 215 K transition.

What mechanism gives rise to the 90 K transition? The diffuse scattering that appears in the single-crystal XRD patterns might provide a hint to answering this question. In the single-crystal XRD patterns of Phases I, II, and III shown in Fig. 4, there are diffuse scatterings at the same positions, which follow the extinction rule of h + l = 4n (for a cubic unit cell) and connect the superlattice spots that emerged in Phase III. This suggests that the structural change from Phase II to III and the diffuse scatterings have the same origin. The same diffuse scattering pattern also appeared in CsW1.835O6 (Supplementary Fig. 7) and CsTi0.5W1.5O646, which are isostructural to CsW2O6, but only have W6+ atoms without 5d electrons, suggesting that they are independent of the 215 K transition and might be caused by the structural instability of the β-pyrochlore structure itself. This discussion also implies that the 215 K transition is irrelevant to this instability and is purely electronic driven.

Single crystal XRD patterns taken at 25 (Phase III), 100 (Phase II), and 250 K (Phase I) are shown. Diffuse scatterings are emphasized in these patterns. Since the intensity of diffuse scattering is much lower than those of Bragg reflections, the observed diffuse scattering has no effect on the crystal-structure refinement.

In conclusion, we found that regular-triangle W3 trimers are formed at the 215 K transition in β-pyrochlore oxide CsW2O6, as determined using structural- and electronic-property measurements of high-quality single crystals. This transition represents the self-organization of 5d electrons, where geometrical frustration is relieved in a nontrivial way that satisfies the traditional Anderson condition and results in the quite rare cubic−cubic structural transition. This type of electronic transition is not only unusual, but is only partly understood by the first principles calculations, suggesting that it might be a spin-, charge-, and orbital-coupled phase transition occurring beyond the existing electronic phase transitions of pyrochlore systems. The above finding shows that the exploration of geometrically frustrated 5d compounds will lead to the discovery of further interesting electronic phenomena, such as odd-parity multipoles and spin–charge–orbital entangled quantum liquids.

Methods

Sample preparation

Single crystals of CsW2O6 were prepared by crystal growth in an evacuated quartz tube under a temperature gradient. A mixture of a 3:1:3 molar ratio of Cs2WO4 (Alfa Aeser, 99.9%), WO3 (Kojundo Chemical Laboratory, 99.99%), and WO2 (Kojundo Chemical Laboratory, 99.99%), with a combined mass of 0.1 g, was sealed in an evacuated quartz tube with 0.1 g of CsCl (Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, 99.9%). The hot and cold sides of the tube were heated to, and then kept at 973 K and 873 K, respectively, for 96 h, and then the furnace was cooled to room temperature. The mixture was put on the hot side. The obtained single crystals had an octahedral shape with {111} faces with edges of at most 1 mm. Powder samples of CsW2O6 were prepared by the solid-state reaction method described in the previous studies10,11. The obtained powder was sintered at 773 K for 10 min using a spark plasma sintering furnace (SPS Syntex).

Single crystals of W-deficient CsW2−xO6 were prepared using the flux method. A mixture of a 3:1:3 molar ratio of Cs2WO4 (Alfa Aeser, 99.9%), WO3 (Kojundo Chemical Laboratory, 99.99%), and WO2 (Kojundo Chemical Laboratory, 99.99%), with the combined mass of 0.1 g, and 0.2 g of CsCl (Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, 99.9%) were put in an alumina crucible, which was sealed in an evacuated quartz tube. The tube was heated to, and then kept at 923 K for 48 h, and then slowly cooled to 873 K at a rate of −0.5 K/h. The obtained single crystals have similar octahedral shape and mostly have a larger size than those of CsW2O6. The value of the W deficiency, x, was estimated to be 0.165 via a structural analysis using the single-crystal XRD data, meaning that the chemical composition of the single crystal is CsW1.835O6, where the W atoms have no 5d electrons.

Measurements and first principles calculations

The electrical resistivity and magnetization measurements of the CsW2O6 and CsW1.835O6 single crystals were performed using a Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS, Quantum Design) and Magnetic Property Measurement System (Quantum Design), respectively. The normal incident reflectivity of (111) surface of a CsW2O6 single crystal was taken at room temperature using a Fourier-type interferometer (0.005−1.6 eV, DA-8, ABB Bomem; 0.06−1.0 eV, FT-IR6100, Jasco) and a grating spectrometer (0.46−5.8 eV, MSV-5200, Jasco) installed with a microscope40,47. As a reference mirror, we used either evaporated Au (far- to near-IR region), Ag (near-IR to visible region), or Al (near- to far-UV region) films on a glass plate. The heat capacity of the CsW2O6 sintered sample was measured using the relaxation method with the PPMS. Single-crystal XRD experiments of the CsW2O6 and CsW1.835O6 samples were performed at BL02B1 in the SPring-8 synchrotron radiation facility in Japan. The experimental conditions are shown in Supplementary Tables 1, 3, and 5. SORTAV and SHELXL were used for merging the reflection data and the structural refinement48,49,50. A part of crystal structure views were drawn using VESTA51. Powder XRD experiments of CsW2O6 were performed at BL02B2 in SPring-8. Synchrotron X-rays with energies of 15.5 and 25 keV were used for the measurements below and above 150 K, respectively. Rietveld analyses of the powder XRD data were performed using GSAS. Raman scattering spectra of the CsW2O6 single crystals were measured using a diode-pumped CW solid-state laser with a wavelength of 5614 Å. 133Cs-NMR measurements of a CsW2O6 single crystal were conducted in a magnetic field of 8 T. The NMR spectra were obtained by Fourier transforming the free induction decay signal. The band structure calculations of Phase I of CsW2O6 were performed using the full potential linear augmented plane wave (FLAPW) method with a local density approximation. The experimentally obtained structural parameters shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 were used for the calculations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the authors.

References

Verwey, E. J. W. Electronic conduction of magnetite (Fe3O4) and its transition point at low temperatures. Nature 144, 327–328 (1939).

Senn, M. S., Wright, J. P. & Attfield, J. P. Charge order and three-site distortions in the Verwey structure of magnetite. Nature 481, 173–176 (2012).

Yamaura, J. et al. Tetrahedral magnetic order and the metal-insulator transition in the pyrochlore lattice of Cd2Os2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 247205 (2012).

Tomiyasu, K. et al. Emergence of magnetic long-range order in frustrated pyrochlore Nd2Ir2O7 with metal–insulator transition. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 81, 034709 (2012).

Sagayama, H. et al. Determination of long-range all-in-all-out ordering of Ir4+ moments in a pyrochlore iridate Eu2Ir2O7 by resonant x-ray diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 87, 100403 (2013).

Hiroi, Z., Yamaura, J., Hirose, T., Nagashima, I. & Okamoto, Y. Lifshitz metal–insulator transition induced by the all-in/all-out magnetic order in the pyrochlore oxide Cd2Os2O7. APL Mater. 3, 041501 (2015).

Tian, Z. et al. Field-induced quantum metal-insulator transition in the pyrochlore iridate Nd2Ir2O7. Nat. Phys. 12, 134–138 (2016).

Wan, X., Turner, A. M., Vishwanath, A. & Savrasov, S. Y. Topological semimetal and Fermi-arc surface states in the electronic structure of pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205101 (2011).

Ueda, K. et al. Variation of charge dynamics in the course of metal-insulator transition for pyrochlore-type Nd2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 136402 (2012).

Cava, R. J. et al. Cs8.5W15O48 and CSW2O6—members of a new homologous series of cesium tungsten oxides. J. Solid State Chem. 103, 359–365 (1993).

Hirai, D. et al. Spontaneous formation of zigzag chains at the metal-insulator transition in the β-pyrochlore CsW2O6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 166402 (2013).

Streltsov, S. V., Mazin, I. I., Heid, R. & Bohnen, K. P. Spin-orbit driven Peierls transition and possible exotic superconductivity in CsW2O6. Phys. Rev. B 94, 241101 (2016).

Soma, T., Yoshimatsu, K., Horiba, K., Kumigashira, H. & Ohtomo, A. Electronic properties across metal-insulator transition in β-pyrochlore-type CsW2O6 epitaxial films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 115003 (2018).

Hasegawa, T., Takasu, Y., Ogita, N. & Udagawa, M. Raman scattering in KOs2O6. Phys. Rev. B 77, 064303 (2008).

Brown, I. D. & Altermatt, D. Bond-valence parameters obtained from a systematic analysis of the inorganic crystal structure database. Acta Crystallogr. B41, 244–247 (1985).

Okamoto, Y., Nohara, M., Aruga-Katori, H. & Takagi, H. Spin-liquid state in the S = 1/2 hyperkagome antiferromagnet Na4Ir3O8. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 137207 (2007).

Okamoto, Y., Nilsen, G. J., Attfield, J. P. & Hiroi, Z. Breathing pyrochlore lattice realized in A-site ordered spinel oxides LiGaCr4O8 and LiInCr4O8. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 097203 (2013).

Anderson, P. W. Ordering and antiferromagnetism in ferrites. Phys. Rev. 102, 1008–1013 (1956).

Wright, J. P., Attfield, J. P. & Radaelli, P. G. Long range charge ordering in magnetite below the Verwey transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 266401 (2001).

Radaelli, P. G. et al. Formation of isomorphic Ir3+ and Ir4+ octamers and spin dimerization in the spinel CuIr2S4. Nature 416, 155–158 (2002).

Horibe, Y. et al. Spontaneous formation of vanadium “molecules” in a geometrically frustrated crystal: AlV2O4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 086406 (2006).

Browne, A. J., Kimber, S. A. J. & Attfield, J. P. Persistent three- and four-atom orbital molecules in the spinel AlV2O4. Phys. Rev. Mater. 1, 052003 (2017).

Okamoto, Y. et al. Band Jahn–Teller instability and formation of valence bond solid in a mixed-valent spinel oxide LiRh2O4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 086404 (2008).

Hiroi, Z. Structural instability of the rutile compounds and its relevance to the metal–insulator transition of VO2. Prog. Solid State Chem. 43, 47–69 (2015).

Attfield, J. P. Orbital molecules in electronic materials. APL Mater. 3, 041510 (2015).

Verwey, E. J. W., Haaymann, P. W. & Romeijn, F. C. Physical properties and cation arrangement of oxides with spinel structures I. cation arrangement in spinels. J. Chem. Phys. 15, 174–180 (1947).

Matsuda, M. et al. Spin–lattice instability to a fractional magnetization state in the spinel HgCr2O4. Nat. Phys. 3, 397–400 (2007).

Kawai, H., Tabuchi, M., Nagata, M., Tukamoto, H. & West, A. R. Crystal chemistry and physical properties of complex lithium spinels Li2MM′3O8 (M=Mg, Co, Ni, Zn; M′=Ti, Ge). J. Mater. Chem. 8, 1273–1280 (1998).

Strobel, P., Palos, A. I., Anne, M. & Cras, F. L. Structural, magnetic and lithium insertion properties of spinel-type Li2Mn3MO8 oxides (M = Mg, Co, Ni, Cu). J. Mater. Chem. 10, 429–436 (2000).

Sekine, C., Uchiumi, T., Shirotani, I. & Yagi, T. Metal-insulator transition in PrRu4P12 with skutterudite structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 3218–3221 (1997).

Lee, C.-H. et al. Structural phase transition accompanied by metal–insulator transition in PrRu4P12. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 13, L45–L48 (2001).

Harima, H., Takegahara, K., Curnoe, S. H. & Ueda, K. Theory of metal-insulator transition in praseodymium skutterudite compounds. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 71, 70–73 (2002).

Pen, H. F., van den Brink, J., Khomskii, D. I. & Sawatzky, G. A. Orbital ordering in a two-dimensional triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1323–1326 (1997).

Katayama, N., Uchida, M., Hashizume, D., Niitaka, S., Matsuno, J., Matsumura, D., Nishihata, Y., Mizuki, J., Takeshita, N., Gauzzi, A., Nohara, M. & Takagi, H. Anomalous metallic state in the vicinity of metal to valence-bond solid insulator transition in LiVS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 146405 (2009).

Kojima, K., Katayama, N., Tamura, S., Shiomi, M. & Sawa, H. Vanadium trimers randomly aligned along the c-axis direction in layered LiVO2. Phys. Rev. B 100, 235120 (2019).

Takayama, T. et al. Spin-orbit coupling induced semi-metallic state in the 1/3 hole-doped hyper-kagome Na3Ir3O8. Sci. Rep. 4, 6818 (2014).

Müller, U. Inorganic Structural Chemistry (pp. 128–149. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK, 2007).

Oka, T. Observation of the infrared spectrum of H3 +. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 531–534 (1980).

Subramanian, M. A., Aravamudan, G. & Subba Rao, G. V. Oxide pyrochlores. Prog. Solid State Chem. 15, 55–143 (1983).

Jönsson, P. E. et al. Correlation-driven heavy-fermion formation in LiV2O4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 167402 (2007).

Uchida, S. et al. Optical spectra of La2−xSrxCuO4: effect of carrier doping on the electronic structure of the CuO2 plane. Phys. Rev. B 43, 7942–7954 (1991).

Imada, M., Fujimori, A. & Tokura, Y. Metal-insulator transition. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 1039–1263 (1998).

Basov, D. N., Averitt, R. D., van der Marel, D., Dressel, M. & Haule, K. Electrodynamics of correlated electron materials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 471–541 (2011).

Kézsmárki, I. et al. Charge dynamics near the electron-correlation induced metal-insulator transition in pyrochlore-type molybdates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 266401 (2004).

Yoshitake, J. & Motome, Y. Trimer formation and metal–insulator transition in orbital degenerate systems on a triangular lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 80, 073711 (2011).

Thorogood, G. J., Saines, P. J., Kennedy, B. J., Withers, R. L. & Elcombe, M. M. Diffuse scattering in the cesium pyrochlore CsTi0.5W1.5O6. Mater. Res. Bull. 43, 787–795 (2008).

Takenaka, K. et al. Anisotropic optical spectra of BaCo1−xNixS2: effect of Ni substitution on the electronic structure of the Co1−xNixS plane. Phys. Rev. B 63, 115113 (2001).

Blessing, R. H. Data reduction and error analysis for accurate single crystal diffraction intensities. Crystallogr. Rev. 1, 3–58 (1987).

Blessing, R. H. DREADD—data reduction and error analysis for single-crystal diffractometer data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 22, 396–397 (1989).

Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A64, 112–122 (2008).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Y. Yamakawa, A. Yamakage, A. Koda, R. Kadono, J. Matsuno, and D. Hirai for helpful discussions and T. Fujii for his help with experiments. Y.O. is also grateful for collaboration with Y. Nagao, J. Yamaura, M. Ichihara, Z. Hiroi, and M. Yoshida in the early stage of this work using polycrystalline samples. This work was partly carried out under the Visiting Researcher Program of the Institute for Solid State Physics, the University of Tokyo and supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number: 18H04314, 19H05823, 16H03848, 15H05886, 15H05882, 20K03829, 17H02918, 18H04310).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The samples were prepared by K.N., R.M., and Y.O. Single crystal XRD experiments were performed by H.A., H.S., and N.K. Electrical resistivity was measured by K.N., Y.O., and K. Takenaka. Reflectivity measurements were done by Y.Y., K. Takenaka, K. Takehana, Y.I., K.N., Y.N., and H.K. Magnetic susceptibility and heat capacity were measured by Y.O., K.N., and R.M. Raman scattering experiments were performed by T.H., R.M., and N.O. NMR experiments were performed by Y.T. and M.T. First principles calculations were performed by H.H. The manuscript was drafted by Y.O. and revised by all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Alexander Yaresko and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okamoto, Y., Amano, H., Katayama, N. et al. Regular-triangle trimer and charge order preserving the Anderson condition in the pyrochlore structure of CsW2O6. Nat Commun 11, 3144 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16873-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16873-7

This article is cited by

-

Perfect flat band with chirality and charge ordering out of strong spin-orbit interaction

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.