Abstract

The sodium channels Nav1.7, Nav1.8 and Nav1.9 are critical for pain perception in peripheral nociceptors. Loss of function of Nav1.7 leads to congenital insensitivity to pain in humans. Here we show that the spider peptide toxin called HpTx1, first identified as an inhibitor of Kv4.2, restores nociception in Nav1.7 knockout (Nav1.7-KO) mice by enhancing the excitability of dorsal root ganglion neurons. HpTx1 inhibits Nav1.7 and activates Nav1.9 but does not affect Nav1.8. This toxin produces pain in wild-type (WT) and Nav1.7-KO mice, and attenuates nociception in Nav1.9-KO mice, but has no effect in Nav1.8-KO mice. These data indicate that HpTx1-induced hypersensitivity is mediated by Nav1.9 activation and offers pharmacological insight into the relationship of the three Nav channels in pain signalling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, and is a serious public health issue1. However, pain is also a part of the body’s warning mechanism, cautioning humans to take action to prevent further tissue damage2,3,4. The voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav) Nav1.7 is known to play critical roles in the regulation of peripheral pain. Homozygous or compound heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in Nav1.7 lead to congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP)2,5,6, whereas gain-of-function mutations cause episodic pain (i.e., primary erythromelalgia and paroxysmal extreme pain disorder) in humans7,8,9. This evidence indicates that selectively blocking Nav1.7 may be useful to relieve pain. Sustained efforts have been made to develop selective inhibitors of this channel, some of which have shown efficacy in clinical studies, although larger clinical trials are needed to definitively assess efficacy10,11,12,13. On the other hand, compared with painful, painless may be more serious. CIP individuals cannot distinguish between sharp and dull stimuli, leading to self-mutilation and painless fractures, and some individuals are even unable to detect temperature differences2,5,6. Therefore, therapeutics that restore the pain responses in Nav1.7-related CIP would be useful. Notably, Nav1.7 might not be a suitable direct target to achieve such an effect because of its loss of function in affected individuals; therefore, an alternative strategy should be developed. Nav1.7 and two other Nav subtypes, Nav1.8 and Nav1.9, are preferentially expressed in the peripheral terminals of sensory neurons14. More recently, genetic and functional studies have illustrated that mutations in Nav1.8 and Nav1.9 cause human pain disorders, providing direct clinical evidence linking these two channels to human pain3,15,16,17. Considering that the three channels play distinct roles in the generation and propagation of action potentials (APs)18,19,20, they might regulate pain signaling cooperatively, and the elucidation of their relationship in pain regulation may be helpful for the treatment of Nav1.7-related CIP.

Animal venom is a rich source of Nav modulators and potential therapeutic compounds21,22,23,24,25,26. Specific modulators are not only novel drug candidates for therapeutics but also powerful pharmacological tools to probe the physiological roles of Navs23,25,26,27,28. In this study, we screened pain-inducing compounds from animal venoms and discovered that a spider peptide toxin, HpTx1, was able to rescue the pain response in Nav1.7 knockout (Nav1.7-KO) mice by activating Nav1.9. HpTx1 was previously identified as an inhibitor of the voltage-gated potassium channel (Kv) Kv4.229, but our study showed that it is also a Nav modulator. Here, we provide pharmacological evidence that cross talk among Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 may affect AP firing and pain signaling, thereby establishing an important role for Nav1.9 in pain perception.

Results

HpTx1 induces pain responses in Nav1.7-KO mice

To discover peptide activators that can induce pain and recover pain responses in Nav1.7-related CIP, we first fractionated 15 crude venoms (from ten spiders and five snakes) using semipreparative reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) and collected a total of 110 fractions (5–10 fractions per venom). Six of these fractions were identified to have pain-inducing activity, with a fraction from the venom of the spider H. venatoria exhibiting the strongest efficacy (Fig. 1a). By further purifying this fraction by analytical RP-HPLC, we identified a component with such a pain-inducing efficacy and named it HpTx1 (rational nomenclature: κ-sparatoxin-Hv1a). The molecular weight of HpTx1 was 3910.8 Da as determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI–TOF MS) (Supplementary Fig. 1a). HpTx1 was found to have some sequence similarity, especially a conserved cysteine pattern, with some spider peptide toxins adopting an inhibitor cystine knot (ICK) motif (Fig. 1b), suggesting that the space structure of HpTx1 might contain a typical ICK motif.

a RP-HPLC profile of the venom from the spider H. venatoria. The F3 fraction contains HpTx1 (pink). b Sequence alignment of HpTx1 with several ICK toxins; red lines show the disulfide linkage. c Comparison of nocifensive behaviors (licking or biting) following intraplantar injection of vehicle (10 μl 0.9% saline, n = 6) versus HpTx1 (1 μM or 10 μM in 10 μl saline, n = 6) (two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × genotype: F(2,30) = 3.447, P = 0.0449; treatment: F(2,30) = 24.05, P < 0.0001; genotype: F(1,30) = 23.09, P < 0.0001). d Mechanical response thresholds measured in paws in response to vehicle (black circles, n = 6), 1 μM HpTx1 (yellow squares, n = 6 for fNav1.7 mice; n = 5 for Nav1.7-KO mice) or 10 μM HpTx1 (red triangles, n = 6) injections (two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × genotype: F(2,29) = 10.52, P = 0.0004; treatment: F(2,29) = 54.72, P < 0.0001; genotype: F(1,29) = 150.2, P < 0.0001). e Latency of paw withdrawal (WD) to a noxious thermal stimulus measured after intraplantar injection of vehicle (black circles, n = 6), 1 μM HpTx1 (yellow squares, n = 6 for fNav1.7 mice; n = 5 for Nav1.7-KO mice) or 10 μM HpTx1 (red triangles, n = 6) (two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × genotype: F(2,29) = 2.857, P = 0.0737; treatment: F(2,29) = 36.83, P < 0.0001; genotype: F(1,29) = 17.71, P = 0.0002). f Images of hind paws with Evans blue staining. Ipsi ipsilateral paws, Contra contralateral paws. g Quantification of Evans blue staining in ipsilateral and contralateral hind paws (n = 3, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × paw: F(2,12) = 96.1, P < 0.0001; treatment: F(2,12) = 87.79, P < 0.0001; paw: F(1,12) = 128.9, P < 0.0001). h Relative thickness of injected hind paws normalized to that of uninjected ones (n = 5 for vehicle, n = 6 for formalin, n = 8 for HpTx1, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test: F(2,16) = 160.9, P < 0.0001). Data are represent the mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Exact P (c–e, g, h) are presented in Supplementary Data 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next examined whether HpTx1 could produce pain sensation in mice lacking Nav1.7. According to methods reported previously30,31, we generated Nav1.7-KO mice by crossing Nav1.7 floxed mice (fNav1.7 in C57BL/6 genetic background) with Nav1.8-Cre mice, which led to the specific deletion of Nav1.7 in Nav1.8-positive sensory neurons (tissue-restricted Nav1.7 knockout, Nav1.7-KO). These mice showed deficits in mechanical pain responses but no alteration in thermal pain behavior (Fig. 1d, e), consistent with the results reported by Minett et al.31. As shown in Fig. 1c, injection of 10 μM HpTx1 into the hind paws of Nav1.7-KO mice or control (fNav1.7) littermate mice triggered robust nocifensive behaviors, such as licking and biting of the injected paws. Furthermore, the pain-inducing effect was further validated in evoked pain models (Fig. 1d, e). Nav1.7-KO mice treated with 10 μM HpTx1 recovered the deficit in mechanical pain caused by Nav1.7 ablation (Fig. 1d); injection of 10 μM HpTx1 also reduced thresholds for thermal pain in Nav1.7-KO mice, paralleling the effect of HpTx1 on fNav1.7 mice (Fig. 1e).

Unlike intraplantar injection of 10% formalin, which elicited robust neurogenic inflammation in the injected hind paws, HpTx1 injection failed to produce neurogenic inflammation, as revealed by the Evans blue test (Fig. 1f, g). No swelling was observed in hind paws injected with 50 μM HpTx1, whereas serious edema was found with injection of 10% formalin (Fig. 1h). These results suggested that HpTx1 evoked pain behaviors in fNav1.7 and Nav1.7-KO mice, but failed to trigger neurogenic inflammation.

HpTx1 activates some small DRG neurons in Nav1.7-KO mice

The effects of HpTx1 on membrane excitability were examined in small (<30 μm) dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons from WT mice by using current-clamp recordings. Four parameters related to AP firing, including resting membrane potential (RMP), current threshold (rheobase), amplitude, and firing frequency, were determined in the experiments. As shown in Fig. 2a, 0.75 μM HpTx1 significantly depolarized RMP by ~2.0 mV (control: −50.4 ± 1.2 mV; HpTx1: −48.4 ± 1.3 mV; n = 30, P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table 1). Treatment with 0.75 μM HpTx1 remarkably decreased the rheobase to evoke an AP by 9.3 pA (control: 41.3 ± 3.9 pA; HpTx1: 32.0 ± 3.4 pA; n = 30, P = 0.0026) (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Table 1). Importantly, 15 out of the 30 DRG neurons tested (50.0%) exhibited a decrease in rheobase in the presence of HpTx1, whereas 10% exhibited an increase, and 40% showed no change (Supplementary Table 2). However, no significant changes in AP amplitude were observed in the presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1 (control: 117.8 ± 1.3 mV; HpTx1: 116.8 ± 1.4 mV; n = 30, P = 0.1) (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Table 1). In 10 out of the 15 neurons with reduced rheobase, the reduction in rheobase was also associated with a prominent increase in firing frequency in response to depolarizing currents (Fig. 2d). The input resistance remained unchanged by HpTx1 treatment (Supplementary Table 1). Similar effects of HpTx1 on membrane excitability were observed in some small DRG neurons from fNav1.7 mice (Fig. 2a–c; Supplementary Table 1).

a–d Current-clamp recording shows that HpTx1 enhances the excitability of small (<30 μm) DRG neurons from WT and fNav1.7 mice. Bars show significant changes for RMP (a, two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × genotype: F(1,39) = 0.02197, P = 0.8829; treatment: F(1,39) = 22.12, P < 0.0001; genotype: F(1,39) = 0.9114, P = 0.3456) and rheobase (b, two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × genotype: F(1,41) = 0.01839, P = 0.8928; treatment: F(1,41) = 15.47, P = 0.0003; genotype: F(1,41) = 0.02329, P = 0.8795), but no effect on AP amplitude (c) in the presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1. d Statistics plots show significant increases in AP spike number in the presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1 (n = 15, two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × inject current: F(7,98) = 2.228, P = 0.0382; treatment: F(1,14) = 7.716, #P = 0.0148; inject current: F(7,98) = 8.916, P < 0.0001). e–g Current-clamp recordings show that HpTx1 increases the excitability of small DRG neurons from Nav1.7-KO mice. e Bars show significant changes for RMP (left, n = 28, parametric paired two-tailed t test: t27 = 3.0, P = 0.006) and rheobase (middle, n = 29, nonparametric Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test: P = 0.0003), but no effect for AP amplitude (right, n = 29, parametric paired two-tailed t test: t28 = 1.7, P = 0.093) in the presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1. f AP traces recorded from a representative Nav1.7-KO mouse DRG neuron before (black) and after (red) the application of HpTx1. The dashed lines indicate 0 mV. g Statistics plots show significant increases in AP spike number in the presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1 (n = 19, two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × inject current: F(7,126) = 2.313, P = 0.0298; treatment: F(1,18) = 17.69, ###P = 0.0005; inject current: F(7,126) = 14.2, P < 0.0001). All DRG neurons recorded were held at −53 ± 2 mV. Error bars represent the mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Exact P (a, b, d, g) are presented in Supplementary Data 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The effects of HpTx1 on membrane excitability were also assessed in small DRG neurons from Nav1.7-KO mice. As shown in Fig. 2e, 0.75 μM HpTx1 significantly depolarized RMP by 3.2 mV (control: −49.6 ± 1.0 mV; HpTx1: −46.4 ± 1.1 mV; n = 28, P = 0.006) and decreased the rheobase by 16.6 pA (control: 48.3 ± 4.6 pA; HpTx1: 31.7 ± 3.4 pA; n = 29, P = 0.0003), but did not alter AP amplitude (control: 108.2 ± 1.3 mV; 0.75 μM HpTx1: 106.5 ± 1.3 mV; n = 29, P = 0.09) (Supplementary Table 1) or input resistance (Supplementary Table 1). A total of 65.5% of neurons (19 out of 29) showed a decrease in rheobase in the presence of HpTx1 (Supplementary Table 2), and these neurons that exhibited a reduction in rheobase also showed enhanced AP firing in response to depolarizing currents (Fig. 2f, g). These results indicated that HpTx1 might enhance the membrane excitability of some small DRG neurons from WT, fNav1.7, and Nav1.7-KO mice by depolarizing RMP, decreasing current threshold, and increasing AP firing.

HpTx1 is an inhibitor of Nav1.7 and an activator of Nav1.9

Sanguinetti et al.29 demonstrated that HpTx1 is a blocker of the Kv4.2 channel. Our study confirmed HpTx1 inhibition of Kv4.2 currents, with a half-maximal inhibitor concentration (IC50) value measured at 1.2 ± 0.3 μM (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Kv4.2 is crucial for the ERK-dependent modulation of dorsal horn neuronal excitability and the ERK-dependent hyperalgesia, but it is seldomly expressed in peripheral sensory neurons32,33. We further found that HpTx1 had no evident effect on voltage-gated potassium channels in DRG neurons, and the current–voltage curves were not altered by HpTx1 treatment (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). Therefore, we assumed that potassium channel inhibition might not be the primary reason for pain reactions induced by HpTx1. Moreover, HpTx1 did not change voltage-gated calcium channels in DRG neurons (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Therefore, we investigated the effect of HpTx1 on Navs. HpTx1-induced pain responses were not distinct between the WT and Nav1.7-KO mice, suggesting that the responses are independent of Nav1.7. Unexpectedly, HpTx1 inhibited the human Nav1.7 (hNav1.7) currents expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells with an IC50 value of 0.51 ± 0.12 μM (Fig. 3a) without altering the steady-state activation (control: V1/2 = −21.9 ± 1.9 mV and k = 5.2 ± 0.2 mV; HpTx1: V1/2 = −22.1 ± 3.3 mV and k = 6.9 ± 0.3 mV; n = 4, P > 0.05) or inactivation (control: V1/2 = −70.7 ± 1.9 mV and k = −4.8 ± 0.1 mV; HpTx1: V1/2 = −73.5 ± 1.7 mV and k = −4.7 ± 0.1 mV; n = 7, P > 0.05) of this channel (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Table 3). In addition, examination of the effect of HpTx1 on tetrodotoxin-sensitive (TTX-S) Nav channels in WT mouse small DRG neurons demonstrated that 1 μM HpTx1 inhibited TTX-S Nav currents by 62.9 ± 7.8% (Fig. 3c). In addition to Nav1.7, the TTX-S channel Nav1.6 is also found within small DRG neurons. Indeed, HpTx1 had inhibitory activity on Nav1.6 with an IC50 of 5.63 ± 0.13 μM, indicating that HpTx1 was tenfold less potent at Nav1.6 than at Nav1.7 (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Vasylyev et al.34. estimated that ~70% TTX-S Nav currents are mediated by Nav1.7 in mouse small DRG neurons. These data suggested that the observed effect on TTX-S Nav currents mainly arise from Nav1.7 inhibition by HpTx1.

a The dose-dependent inhibition of hNav1.7 currents by HpTx1 (n = 7). The inset shows representative current traces in the presence (red) or absence (black) of 2 μM HpTx1. b Voltage-dependent steady-state activation (G/Gmax, n = 4) and fast inactivation (I/Imax, n = 7) of hNav1.7 are not altered by 1 μM HpTx1. c Representative currents show the effect of 1 μM HpTx1 on TTX-S Navs in mouse small DRG neurons. d, e HpTx1 increases TTX-R Nav currents in mouse small DRG neurons and inhibits their fast inactivation, as shown by representative current traces (d) and current density (e, n = 6, two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × voltage: F(6,30) = 9.099, P < 0.0001; treatment: F(1,5) = 15.41, #P = 0.0111; voltage: F(6,30) = 16.25, P < 0.0001). f Bars show noninactivated components observed in the steady-state inactivation (SSI) curve (at −20 mV) of multiple mouse TTX-R channels in the presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1 (unpaired two-tailed t test, WT mice: t12 = 4.09, P = 0.0015, n = 7; Nav1.7-KO mice: t20 = 6.447, P < 0.00001, n = 11; Nav1.8-KO mice: t22 = 5.905, P < 0.00001, n = 12; Nav1.9-KO mice: t6 = 1.999, P = 0.0925, n = 4). Note that 1 μM TTX was applied in these experiments (d–f). g The dose–response curves for the HpTx1-induced inhibition of the fast inactivation of hNav1.9 expressed in ND7/23 cells (n = 5). The inset shows representative current traces (left) and normalized current traces (right) in the absence (black) and presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1 (red). h HpTx1 significantly slows the fast inactivation time of hNav1.9 (n = 6 for control, n = 5 for HpTx1, two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × voltage: F(7,66) = 6.386, P < 0.0001; treatment: F(7,66) = 27.35, ####P < 0.0001; voltage: F(1,66) = 411.9, P < 0.0001). i Voltage dependence of the steady-state activation (G/Gmax) and inactivation (I/Imax) of hNav1.9 for the control (black dots, n = 5 for activation, n = 6 for inactivation) and with 0.75 μM HpTx1 application (red diamonds, n = 5 for activation, n = 9 for inactivation). Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, NS not significant. Exact P (e, h-i) are presented in Supplementary Data 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

From our understanding, inhibition of Nav1.7 may produce analgesia rather than pain. This seemingly paradoxical result suggests that other ion channels might be involved in HpTx1-induced pain. Therefore, the two TTX-resistant (TTX-R) channels, Nav1.8 and Nav1.9, were examined. As shown in Fig. 3d, e and Supplementary Fig. 2a, HpTx1 robustly enhanced the current amplitude and inhibited the fast inactivation of TTX-R Nav channels in mouse small DRG neurons. Specifically, steady-state inactivation (SSI) was not significantly altered (Supplementary Fig. 2b), but a noninactivated component (~35–42% of the transient inward peak currents) was observed in the SSI curve in the presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1 (Fig. 3f). These effects were limited to DRG neurons expressing Nav1.9 (Fig. 3f; Supplementary Fig. 2b), which was further confirmed in ND7/23 cells heterologously expressing Nav1.8 or Nav1.9. HpTx1 significantly enhanced human Nav1.9 (hNav1.9) currents in ND7/23 cells (Fig. 3g; Supplementary Fig. 2c) and potently inhibited the fast inactivation of this channel (Fig. 3g, h), consistent with the effect of HpTx1 on TTX-R Nav currents in mouse DRG neurons. The half-maximum effective concentration (EC50) of HpTx1 was determined to be 0.47 ± 0.08 μM (Fig. 3g). In contrast, HpTx1 did not affect rat Nav1.8 (rNav1.8) currents expressed in ND7/23 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2d).

Further investigation showed that 0.75 μM HpTx1 had no effect on the voltage dependence of the steady-state activation of hNav1.9 (control: V1/2 = −38.2 ± 3.6 mV and k = 8.9 ± 1.5 mV; HpTx1: V1/2 = −35.2 ± 3.0 mV and k = 10.0 ± 0.9 mV; n = 6, P > 0.05). However, the voltage dependence of the SSI was significantly shifted by approximately 13.4 mV in the presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1 (control: V1/2 = −69.9 ± 1.3 mV and k = −9.0 ± 0.7 mV; HpTx1: V1/2 = −56.5 ± 2.4 mV and k = −15.0 ± 0.6 mV; n = 8, P = 0.0009) (Fig. 3i; Supplementary Table 3). This result differed from the effect of HpTx1 on TTX-R Nav currents in DRG neurons, potentially due to differences between DRG neurons and ND7/23 cells and between mouse Nav1.9 (mNav1.9) and hNav1.9 sequences. Nav1.9 channels in ND7/23 cells and DRG neurons have distinct posttranslational modifications and auxiliary subunits that are known to affect the pharmacological properties and physiological properties of Nav channels35,36. However, for both TTX-R Nav currents in DRG neurons and Nav1.9 currents in ND7/23 cells, their window currents were obviously improved in the presence of HpTx1 (Fig. 3i). Indeed, 0.75 μM HpTx1 robustly increased the peak of the ramp current of TTX-R Nav in small DRG neurons from WT mice by 62.0 ± 8.8% (Supplementary Fig. 2e) and of hNav1.9 expressed in ND7/23 cells by 71.8 ± 14% (Supplementary Fig. 2f), potentially increasing Na+ influx and leading to enhanced excitability of DRG neurons.

As a further test of toxin specificity, HpTx1 produced neither activation nor persistent inhibition when applied to other pain-related ion channels, including transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) and acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Taken together, these results suggested that HpTx1 enhances Nav1.9 activity by inhibiting its fast inactivation and that the mechanism by which HpTx1 improves membrane excitability and evokes pain in Nav1.7-KO mice might be related to this enhanced Nav1.9 activity.

HpTx1-triggered pain responses depend on Nav1.9 activity

We next tested the effects of HpTx1 on the membrane excitability of small DRG neurons from Nav1.9-KO mice. As shown in Fig. 4a, 0.75 μM HpTx1 did not change RMP (control: −50.2 ± 1.7 mV; HpTx1: −49.1 ± 1.7 mV; n = 29, P = 0.1828), but significantly increased rheobase by 10.4 pA (control: 40.0 ± 4.3 pA; HpTx1: 50.4 ± 5.6 pA; n = 25, P = 0.008). Furthermore, HpTx1 had no effect on AP amplitude (control: 110.6 ± 1.3 mV; HpTx1: 109.7 ± 1.7 mV; n = 25, P = 0.3132) or input resistance (Supplementary Table 1). The increased rheobase in the presence of HpTx1 led to an obvious suppression in the evoked AP firing frequency of small DRG neurons from Nav1.9-KO mice with HpTx1 treatment (Fig. 4b, c, n = 25). These effects differed from those observed in WT and Nav1.7-KO mice, and these differences could be interpreted to be due to the inhibition of Nav1.7 currents by HpTx1.

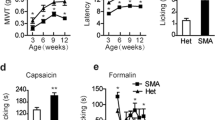

a–c Current-clamp recordings show that HpTx1 decreases the membrane excitability of small DRG neurons from Nav1.9-KO mice. a Bars show no significant changes in RMP (left, n = 29) or AP amplitude (right, n = 25), but a significant increase in rheobase (middle, n = 25, nonparametric Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank two-tailed test: P = 0.008) in the presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1. b AP traces recorded from a representative small Nav1.9-KO DRG neuron before (black) and after (red) application of 0.75 μM HpTx1. The dashed lines indicate 0 mV. c Statistics plots show significant decreases in AP spike number in the presence of 0.75 μM HpTx1 (n = 25, two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × inject current: F(7,168) = 8.834, P < 0.0001; treatment: F(1,24) = 25.49, ####P < 0.0001; inject current: F(7,168) = 25.28, P < 0.0001). d Comparison of nocifensive behaviors (licking or biting) following intraplantar injection of vehicle (10 μl 0.9% saline, n = 6) versus HpTx1 (1 μM or 10 μM in 10 μl saline, n = 6) (two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × genotype: F(2,30) = 8.551, P = 0.0012; treatment: F(2,30) = 11.04, P = 0.0003; genotype: F(1,30) = 24.37, P < 0.0001). e Mechanical response thresholds measured in paws in response to vehicle (black circles, n = 6), 1 μM HpTx1 (yellow squares, n = 6) or 10 μM HpTx1 (red triangles, n = 6) injections (two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × genotype: F(2,30) = 18.68, P < 0.0001; treatment: F(2,30) = 0.0356, P = 0.9651; genotype: F(1,30) = 67.3, P < 0.0001). f Latency of WD to noxious heat stimuli measured after intraplantar injection of vehicle (black circles, n = 6), 1 μM HpTx1 (yellow squares, n = 6) or 10 μM HpTx1 (red triangles, n = 6) (two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × genotype: F(2,30) = 44.54, P < 0.0001; treatment: F(2,30) = 9.701, P = 0.0006; genotype: F(1,30) = 113.5, P < 0.0001). All DRG neurons recorded were held at −53 ± 2 mV. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Exact P (c–f) are presented in Supplementary Data 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In further in vivo experiments, the pain-related behaviors induced by injection of HpTx1 into hind paws observed in WT mice were not observed in Nav1.9-KO mice (Fig. 4d). In contrast to the decrease in thermal and mechanical stimulus thresholds induced by HpTx1 in WT mice, HpTx1 had an analgesic effect in Nav1.9-KO mice. In Nav1.9-KO mice, HpTx1 significantly increased the mechanical threshold (Fig. 4e) and the latency of paw withdrawal under noxious heat stimulus (Fig. 4f), most likely by inhibiting Nav1.7.

Our data demonstrated that HpTx1 enhanced the excitability of primary afferent neurons and elicited pain, depending on the expression of Nav1.9 and that Nav1.9 activation might be required for such an effect. In addition, Nav1.9 expression in DRG neurons from WT mice showed an ~59.6% overlap with the expression of IB4, a marker for small, unmyelinated nonpeptidergic fibers (Supplementary Fig. 4). As mentioned above, 50–65% of small DRG neurons from WT, fNav1.7 or Nav1.7-KO mice exhibited decreased current thresholds for AP firing. These neurons may be the small nonpeptidergic neurons that express Nav1.9 and may transmit nociceptive signals from the periphery to the spinal dorsal horn37.

HpTx1 fails to affect pain responses in Nav1.8-KO mice

Given the important roles of Nav1.8 in AP generation and pain signaling, we sought to determine whether Nav1.8 is also required for HpTx1-induced pain, although HpTx1 did not directly affect Nav1.8. We investigated the effects of HpTx1 on Nav1.8-KO and Nav1.7/Nav1.8 double-knockout (Nav1.7/Nav1.8-DKO) mice (simultaneous knockout of Nav1.7 and Nav1.8). As shown in Fig. 5a–d, 0.75 μM HpTx1 depolarized the RMP of small DRG neurons from Nav1.8-KO mice by 2.6 mV (control: −46.9 ± 1.9 mV; HpTx1: −44.3 ± 1.8 mV; n = 18, P = 0.0037) without affecting rheobase (control: 40.0 ± 6.1 mV; HpTx1: 38.9 ± 8.0 mV; n = 18, P > 0.999), AP amplitude (control: 83.4 ± 3.2 mV; HpTx1: 82.5 ± 2.3 mV; n = 18, P = 0.9816) or firing frequency (Supplementary Table 1). In Nav1.7/Nav1.8-DKO mice, 0.75 μM HpTx1 significantly depolarized the RMP of small DRG neurons by 5.2 mV (control: −52.3 ± 1.4 mV; HpTx1: −47.1 ± 1.2 mV; n = 19, P < 0.0001) and decreased rheobase by 11.6 pA (control: 60.0 ± 6.3 pA; HpTx1: 48.4 ± 6.4 pA; n = 19, P = 0.0112) but had no effect on AP amplitude (control: 88.4 ± 2.3 mV; HpTx1: 87.0 ± 2.5 mV; n = 19, P = 0.5522) or firing frequency (Fig. 5a–c, e; Supplementary Table 1). These data suggested that HpTx1 failed to enhance small DRG neuron AP firing in Nav1.8-KO and Nav1.7/Nav1.8-DKO mice, despite depolarizing the DRG neuron RMP in both mouse lines.

a–e Current-clamp recordings show the effects of HpTx1 on the excitability of small DRG neurons from Nav1.8-KO mice and Nav1.7/Nav1.8-DKO mice. a RMP (two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × genotype: F(1,35) = 5.792, P = 0.0215; treatment: F(1,35) = 52.44, P < 0.0001; genotype: F(1,35) = 3.389, P = 0.0741), b rheobase (two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × genotype: F(1,35) = 3.465, P = 0.0711; treatment: F(1,35) = 5.092, P = 0.0304; genotype: F(1,35) = 2.656, P = 0.1121), and c AP amplitude (Nav1.8-KO mice, n = 18; Nav1.7/Nav1.8-DKO mice, n = 19). d, e HpTx1 has no effect on the AP firing frequency of small DRG neurons from Nav1.8-KO mice (d, n = 18) or Nav1.7/Nav1.8-DKO mice (e, n = 19, two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, treatment × inject current: F(7,126) = 3.141, P = 0.0043; treatment: F(1,18) = 4.275, P = 0.0534; inject current: F(7,126) = 79.17, P < 0.0001). f–h 10 μM HpTx1 (red diamonds) has no effect on nocifensive behaviors (f, n = 6) or mechanical (g, n = 6) or thermal pain (h, n = 6). All DRG neurons recorded were held at −53 ± 2 mV. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. Exact P (a, b, e) are presented in Supplementary Data 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Intraplantar injection of 10 μM HpTx1, a concentration that elicited acute pain in WT and Nav1.7-KO mice, failed to affect the pain responses in Nav1.8-KO mice (Fig. 5f). In addition, in contrast to the effects of HpTx1 in WT and Nav1.7-KO mice, HpTx1-induced mechanical allodynia (Fig. 5g) and thermal hyperalgesia were abrogated in Nav1.8-KO mice (Fig. 5h). Together, these data suggested that Nav1.8 was also required for HpTx1-induced pain in mice.

The mechanism of HpTx1 acting on Nav1.7 and Nav1.9

At least six different neurotoxin receptor sites have been identified on Nav channels so far, with site 3 and site 4 being hot spots for spider peptide toxins28,38. The involvement of the domain IV (DIV) s3b-s4 segment in the formation of receptor site 3 is crucial for fast inactivation22,39,40. In this study, our data showed that HpTx1 slowed the development of the fast inactivation of Nav1.9 (Fig. 3g, h), implying that HpTx1 might target site 3. To identify the region of Nav1.9 critical for the toxin-induced inhibition of fast inactivation, we constructed several chimaeric channels. Because Nav1.8 was resistant to HpTx1, we made a chimera, in which the voltage-sensor domain DIV (DIV s1–s4) of Nav1.9 was replaced with the corresponding domain of Nav1.8 (named Nav1.9/1.8 DIV s1–s4) (Supplementary Fig. 5a). In this chimaera channel, HpTx1 exhibited a significant decrease in efficacy (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Further investigation showed that replacing the DIV s3b-s4 P1 region of Nav1.9 abolished the effects of HpTx1 on the channel (Fig. 6a, b; Supplementary Fig. 5c), but replacing the DIV s1-s2 linker did not (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Moreover, we confirmed that reverse construction of Nav1.9 DIV s3b-s4 P1 into Nav1.8 (Nav1.8/1.9 DIV s3b-s4 P1) conferred the efficacy of HpTx1 (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Fig. 5e). These results indicated that HpTx1 might inhibit the fast inactivation of Nav1.9 through binding to the DIV s3b-s4 region. In addition, site-directed mutagenesis analysis, in which a total of seven amino acid residues in DIV s3–s4 P1 of Nav1.9 were replaced with the corresponding residues of Nav1.8, showed that three mutations (T1444L, E1450L, and N1451K) significantly reduced the toxin activity (Fig. 6c; Supplementary Fig. 5f–h), suggesting that these residues might directly affect the interaction of Nav1.9 with HpTx1.

a Sequence alignments corresponding to the DIV s3b-s4 region of Nav subtypes. The highlighted sequences show the regions swapped between Nav1.8 and Nav1.9. b Representative current traces from Nav1.9/1.8 DIV s3b-s4 P1 (top) and Nav1.8/1.9 DIV s3b-s4 P1 (bottom) chimaera channels in the absence (black) and presence (red) of HpTx1. c Effects of HpTx1 on WT and mutant hNav1.9 channels. Dot plots display the effect of 0.75 μM HpTx1 on the peak current (top, n = 14 for WT; n = 4 for T1444L, M1445L, I1446F, and T1448A; n = 5 for L1449I and E1450L; n = 3 for N1451K) and the persistent current (bottom, n = 14 for WT; n = 4 for T1444L, I1446F, T1448A, and N1451K; n = 5 for M1445L, L1449I, and E1450L). Key residues involved in the interaction between HpTx1 and hNav1.9 are labeled (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, I95/Ipeak: F(7,35) = 17.72, P < 0.0001; I/Imax: F(7,38) = 8.157, P < 0.0001). d (top) Sequence alignments corresponding to the DII s3b-s4 region of Nav subtypes. The highlighted sequences show the regions swapped between Nav1.7 and Nav1.8. Representative current traces from Nav1.7/1.8 DII s3b-s4 (bottom left) and Nav1.8/1.7 DII s3b-s4 (bottom right) chimaera channels in the absence (black) or presence of 5 μM HpTx1 (red). e Dose-dependent inhibitory curves show the effect of HpTx1 on WT (n = 7) and mutant hNav1.7 channels (n = 4 for F813S, n = 6 for L814A and A815S, n = 3 for D816K, n = 6 for V817K, n = 7 for E818G, n = 4 for E818R, n = 5 for G819S and n = 3 for Nav1.7/1.8 DII s3b-s4) and the Nav1.8/1.7 DII s3b-s4 chimaera channel (n = 5). f Bars show the fold changes in IC50 values of HpTx1 for mutant channels compared with that for the WT hNav1.7 channel. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. Exact P (c) are presented in Supplementary Data 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

HpTx1 inhibited Nav1.7 current amplitude without altering steady-state activation and inactivation (Fig. 3b). However, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5i, progressively longer strong depolarization (to +80 mV) led to an increase in the fraction of Na+ currents recovered from inhibition by HpTx1, and increased depolarization potentials were correlated with increased dissociation. The data indicated that the binding of HpTx1 was reversed by prolonged strong depolarization that activated the voltage sensor, similar to our previous results with HWTX-IV41 and HNTX-III42, which are site 4 toxins that interact with Nav1.7 domain II s3b-s4 (DII s3b-s4). Accordingly, chimaera channels of Nav1.7 were constructed. A substitution of the DII s3b-s4 region of Nav1.7 with the corresponding region of Nav1.8 (Nav1.7/1.8 DII s3b-s4) caused this channel to be completely insensitive to HpTx1 (Fig. 6d–f). Similarly, site-directed mutagenesis analysis indicated that D816 and E818 observably affected the efficacy of the HpTx1-Nav1.7 interaction (Fig. 6e, f). In particular, mutating E818 to arginine, an oppositely charged amino acid residue located in the corresponding position of Nav1.9, resulted in an ~20-fold reduction in HpTx1 activity (Fig. 6e, f), potentially explaining why HpTx1 did not depress Nav1.9 currents through binding to DII s3–s4. In addition, two mutants of Nav1.7 (F813S and G819S) increased the efficacy of HpTx1 (Fig. 6e, f). Furthermore, the reverse chimaera (Nav1.8/Nav1.7 DII s3b-s4) conferred toxin sensitivity with an IC50 value of 3.0 ± 0.6 μM (Fig. 6e). However, site-directed mutants, in which seven amino acid residues in DII s3–s4 of Nav1.8 were replaced with the corresponding residues of Nav1.7, were insensitive to HpTx1 (Supplementary Fig. 6). These results suggested that multiple amino acid residues in Nav1.7 DII s3–s4 might be synergistically involved in the interaction with HpTx1.

Discussion

In this study, we discovered that enhancing Nav1.9 activity may recover the pain deficit in CIP caused by loss-of-function of Nav1.7, which was revealed by the intensive study of HpTx1 as a probe. HpTx1 modulates Nav activities through an action mode distinct from previously reported peptide toxins, inhibiting Nav1.7 and activating Nav1.9, but not affecting Nav1.8. Consequently, the effects of HpTx1 on pain responses depend on the expression of these three channels in small DRG neurons. HpTx1 causes pain in WT and Nav1.7-KO mice and analgesia in Nav1.9-KO mice, but is ineffective in Nav1.8-KO mice. The results at the channel level and the data at the animal phenotype level are well connected by the action of HpTx1 on the membrane excitability of small DRG neurons. In other words, this interesting discovery establishes a link among Nav1.7, Nav1.8 and Nav1.9 in the pain signaling pathway and provides a helpful strategy for therapeutic development for Nav1.7-related CIP.

Our study revealed that the activity of Nav1.9 determines the responses of pain or no pain in mice treated with HpTx1. Enhanced activation of Nav1.9 led to hyperexcitability of some small DRG neurons and pain responses in mice regardless of whether Nav1.7 was lacking or inhibited by HpTx1, but Nav1.8 was required in this process. HpTx1 evoked robust pain responses and produced profound hypersensitivity to mechanical and thermal stimuli in Nav1.7-KO mice (Fig. 1c–e), as revealed by the depolarized RMP, reduced rheobase and increased AP firing in some small DRG neurons with Nav1.9 activation by HpTx1 (Fig. 2e–g). In contrast, HpTx1 failed to induce pain in Nav1.9-KO mice, but rather decreased DRG neuron excitability, blocked neuronal signaling, and induced analgesia (Fig. 4), consistent with Nav1.7 inhibition by HpTx1. These observations demonstrate that the two phenotypes derived from the dual activities of HpTx1 (inhibiting Nav1.7 and activating Nav1.9) are manifested in these two mouse mutants. However, WT mice, which express Nav1.7 and Nav1.9, displayed pain responses with HpTx1 treatment, indicating that enhanced Nav1.9 activity might conceal the analgesic activity derived from the inhibition of Nav1.7. Our data suggest that the inhibition of Nav1.7 by HpTx1 treatment may be considered analogous to KO of Nav1.7 to some extent. One possible explanation for the ability of HpTx1-induced Nav1.9 activation to overshadow the analgesic activity derived from HpTx1-induced Nav1.7 inhibition based on the role of Nav1.7 and Nav1.9 as AP threshold channels18,20,43,44 is that HpTx1-bound Nav1.9 largely depolarized the RMP of DRG neurons, potentially compensating for the absence of Nav1.7 and leading to AP generation. Studies have proven that a moderately depolarized RMP contributes to the decrease in the current threshold for AP generation by promoting the opening of other ion channels (i.e., Nav1.8 and voltage-gated calcium channels)45,46. Our data demonstrated that HpTx1 depolarized RMP by 2.0 mV and 3.2 mV in WT and Nav1.7-KO mice, respectively, leading to a reduced current threshold and increased AP and finally enhancing the membrane excitability of some small DRG neurons (Supplementary Table 1). Some studies have shown that histamine induces short-range AP propagation in sensory terminals and evokes a local neurogenic flare in individuals with CIP6,47, which suggests that nociceptive afferents lacking Nav1.7 are not entirely nonfunctional. Histamine has been found to improve the activity of Nav1.9 and enhance AP firing in DRG neurons37,48,49. Studies examining the mechanism by which a gain-of-function mutation of Nav1.9 causes painful disorders have shown depolarized RMP in DRG neurons expressing some of these mutants (for example, a significant 3.5-mV depolarization of RMP was reported for the L1158P mutant)50,51,52. On the other hand, Nav1.9 does not contribute much to the amplitude of APs44, suggesting that enhancing Nav1.9 activity is unable to compensate for the loss of Nav1.8, which contributes to the majority (58–90%) of the inward current during the rising phase of an all-or-none AP in nociceptive sensory neurons19,47,53. Indeed, our data showing that HpTx1 failed to affect AP firing in Nav1.8-KO DRG neurons and pain sensitivity in Nav1.8-KO mice are consistent with this explanation (Fig. 5). In addition, Rush et al.45 demonstrated that the functional consequence of depolarized RMP in part depends on the Nav1.8 expression profile of affected neurons. Therefore, another possible explanation is that depolarization of the RMP of DRG neurons lacking Nav1.8 might result in inactivation of some other channels, resulting in significantly fewer active channels to induce AP electrogenesis.

Our study also provides pharmacological insight into the relationship of Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 in the pain signaling pathway. According to our findings and previous data, the three channels may have different roles in the regulation of membrane excitability and AP firing in DRG neurons. AP generation is the process of neuron membrane depolarization, during which the membrane potential can be described to reach three levels: the RMP, threshold, and upstroke47,54. Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 play distinct roles in these three levels, and their collaboration is required for the generation of a complete AP and repeated firing47. Nav1.9 is believed to set the RMP level of DRG neurons44, supported by the ability of HpTx1-induced Nav1.9 activation and pain-inducing gain-of-function Nav1.9 mutations to depolarize the RMP of DRG neurons50,51,52. Our data demonstrated that the enhanced activity of Nav1.9 reduces the current threshold, showing that, similar to Nav1.7, Nav1.9 can also function as a gain amplifier to amplify subthreshold stimuli in AP firing18,20,43,44. Multiple studies have indicated that Nav1.8 may serve as a major contributor to the rising phase of the AP19,53. Recently, Bennett et al. further refined the contribution of Nav1.7 to AP generation47, proposing that Nav1.7 also contributes to the rising phase, consistent with our finding of a slight decrease in AP amplitude when Nav1.7 is knocked out (Supplementary Table 1). To date, no evidence has shown that Nav1.9 contributes to the rising phase. These findings suggest that the roles of the three channels in AP firing overlap to some extent. Under normal conditions, because of the low amount of Nav1.9 expressed in DRG neurons, its contribution to AP firing related to pain signaling may not be prominent55. Unlike for Nav1.7 and Nav1.8, no loss-of-function mutants for Nav1.9 have been found in the clinic, and Nav1.9-KO mice do not show evident changes in physiological nociception. On the other hand, in hyperalgesic conditions, for example, with HpTx1 treatment, inflammatory factors56, cold51,57 and gain-of-function mutations16,50,51,52,58, the contribution of Nav1.9 can be enhanced and even compensate for the loss of Nav1.7. Therefore, enhanced activation of Nav1.9 may recover the pain responses in Nav1.7-related CIP, as revealed in our studies.

Potentiated pain sensitivity should be beneficial for human Nav1.7-null CIP individuals. Minett et al.59 observed that upregulated endogenous opioids contribute to the analgesia phenotype in Nav1.7-null mutant mice and that the analgesia associated with the loss of Nav1.7 in both mice and humans is substantially reversed by the opioid antagonist naloxone. Our study also revealed that pain sensitivity in Nav1.7-related CIP can be evoked by activating Nav1.9. These studies confirm that a practical treatment strategy for Nav1.7-related CIP may be through targeting the different pain signaling pathways other than Nav1.7 itself. In addition to the ability of agonists such as the peptide toxin HpTx1 to enhance Nav1.9 activity, various other factors have been shown to affect Nav1.9 activity as well. For example, glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) significantly increases Nav1.9 mRNA and current density60, the endogenous molecule contactin promotes the surface expression of Nav1.961,62, and some inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), GTP, and histamine, can markedly increase the current density of Nav1.9 currents and AP firing37,48,49,63,64. Therefore, enhancing the activation of Nav1.9 by regulating these endogenous molecules may be a feasible strategy for treating CIP. However, the possible risks caused by activating Nav1.9 should be noted. Similar to some gain-of-function mutations of Nav1.9, activated Nav1.9 might result in spontaneous pain in humans16,50,51,52, while hyperactive Nav1.9, similar to the L811P and L1302F mutants, may lead to pain insensitivity3,46.

Methods

Venom collection and toxin purification

The venom was obtained by electrical stimulation of female spiders of H. venatoria, and the freeze-dried crude venom was stored at −20 °C prior to analysis. Lyophilized venom was dissolved in double-distilled water. Every time, 10 mg dried venom was purified by semipreparative reverse-phase HPLC using an Ultimate® XB-C18 column (300 Å, 10 mm × 250 mm, Welch Materials Inc., Shanghai, China) on the Hanbon HPLC system (Hanbon Sci&Tech., Jiangsu, China). The following linear gradient of solvent A (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) in solvent B (0.1% formic acid in water) was used at a flow rate of 3 ml min−1: 15% A for 5 min, then 15–60% A over 45 min. Absorbance was measured at 215 nm, and fractions were collected and lyophilized before storage at −20 °C. The target fraction was subjected to the second round of RP-HPLC (Waters alliance 2695 HPLC system) using a XB-C18 column (300 Å, 4.6 mm × 250 mm, Welch Materials Inc., Shanghai, China) with a slower increasing acetonitrile gradient (acetonitrile at an increasing rate of 0.5% per minute, and a flow rate of 1 ml min−1) to obtain the purified HpTx1.

Mass spectrometry and sequencing

The molecular weight of a peptide was analyzed by MALDI–TOF-TOF MS spectrometry (AB SCIEX TOF/TOFTM 5800 system, Applied Biosystems, USA). The entire amino acid sequence of a peptide was obtained by automated Edman degradation using an Applied Biosystems 491 pulsed-liquid-phase sequencer from Applied Biosystem Inc.

Plasmid constructs and mutagenesis

Human Nav1.7 (hNav1.7) and rat Nav1.8 (rNav1.8) clones and beta subunit (β1 and β2) clones were kindly gift from Dr. Theodore R.Cummins (Department of pharmacology and Toxicology, Stark Neurosciences Research Institute, Indiana University School of Medicine, USA). hNav1.7 and rNav1.8 were subcloned into the vectors pcDNA3.1 and pCMV-blank vectors, respectively. hNav1.9 was subcloned into the pEGFP-N1 vector. The C-terminal of hNav1.9 was linked a GFP to construct a fusion protein channel (hNav1.9-GFP)48. The detail methods of mutagenesis are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Cell culture and transfection

ND7/23 and HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 µg ml−1 streptomycin in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Cells were trypsinized, diluted with culture medium, and grown in 35-mm dishes. When grown to 90% confluence, ND7/23 cells were transfected with hNav1.9-GFP or hNav1.9-GFP mutants using the transfection kit X-tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected cells were first maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h, and then incubated at 29 °C with 5% CO2 for 20 h before use in electrophysiology experiments. Transfections of hNav1.7 and hNav1.7 mutants together with β1 and β2-eGFP and other ion channels (Kv4.2, TRPV1 and ASICs with eGFP) into HEK293T cells, and rNav1.8 and rNav1.8 mutants together with eGFP into ND7/23 cells were performed by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Six hours after transfection, the cells were seeded onto poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and maintained at 37 °C in 95% CO2 for 24 h before whole-cell patch-clamp recording. The green fluorescent was used for visual identification of individual transfected cells.

Dorsal root ganglion neuron isolation and culture

Six to eight-week-old C57BL6 WT, fNav1.7, Nav1.7-KO, Nav1.8-KO Nav1.7/Nav1.8-DKO, or Nav1.9-KO mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation under anesthesia. Dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons were collected from the lumbar spinal cord L4–L5. DRG neurons were dissociated by enzymatic treatment with collagenase (1 mg ml−1) and trypsin (0.3 mg ml−1) at 37 °C for 30 min. cells were seeded onto poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips and cultured in DMEM (Gibco) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 for 3 h before whole-cell patch-clamp recording. Note that male and female mice in half were used in each experiment.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) using an EPC-10 USB patch-clamp amplifier operated by PatchMaster software (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany) or Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices). Fire-polished electrodes (2.0–2.5 MΩ) were fabricated from 1.5-mm capillary glass using a P-97 puller (Sutter, Novato, CA). Capacity transients were canceled; voltage errors were minimized with 80% series resistance compensation. The liquid junction potential was corrected using Axopatch 200B series amplifier, the Henderson equation was used to calculate the junction potential based on the ionic strength of bath and pipette solution. During the whole-cell recording performed in the EPC-10 USB amplifier, the liquid junction potential was not corrected. Voltage-dependent currents were acquired with Patchmaster at 5 min after establishing a whole-cell configuration, sampled at 30 kHz, and filtered at 2.9 kHz. The configuration of electrophysiology recording buffer and stimulation pulse are provided in the Supplementary Information.

For electrophysiology experiments, the stock solution of HpTx1 was diluted with fresh bath solution to a concentration of tenfold of the interested concentration, 30 µl of the concentrated peptide was diluted into the recording chamber (containing 270 µl bath solution) far from the recording pipet (the recording cell), and was mixed by repeatedly pipetting to achieve the specified final concentration. TTX and capsaicin were dissolved in DMSO to make 1 mM stock solutions. The final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1%, which was found to have no significant effect on Na+ currents.

Animal experiments

Nav1.9-KO mice have been described earlier56. The floxed Nav1.7 mice and Nav1.8-Cre mice are described by Nassar et al.30. These mice were housed at the constant temperature of 24 °C and 50–60% humidity under controlled conditions of 12 h light/dark cycles and provided with free access to laboratory-standard food and water.

Seven to eight-week-old male (n = 3) and female (n = 3) mice were used on behavioral testing. Before testing, mice were habituated on an elevated platform of the mesh floor and plastic testing chambers for 30 min. HpTx1 was dissolved in saline and administered at doses of 1 μM and 10 μM, respectively. HpTx1 was injected into the hind paws of mice (10 μl saline, 1 μM or 10 μM HpTx1), and the seconds of licking/biting behavior were immediately recorded during a 20 min period following the injection. Nocifensive responses were assessed by the total seconds of licking/biting behavior during 20 min.

The latency to respond to heat was measured to assess the thermal pain threshold after 30 min of injection (Planter Test Analgesia Meter, IITC Inc. Life Science). It was recorded three times by using radiant light heat onto the plantar side of the paw with an interval of at least 5 min. In order to avoid injury to the mice, a cutoff of 20 s was set.

The mechanical withdrawal threshold was assessed by recording the max force that was continuously applied until paw withdrawal (Electronic von Fery Anesthesiometer, IITC Inc. Life Science), and recorded three times with an interval of at least 5 min. Note that all of the behavioral tests were double blind.

Immunofluorescence

DRG neurons were collected from the lumbar spinal cord (L4–L5). The DRG were fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 2 h 30 min at 4 °C then cryoprotected in PBS containing 30% sucrose overnight at 4 °C. The DRG were frozen in OCT, and cryosectioned at 12 μm. The sections were permeabilized in PBS containing 0.5% TritonX-100) for 10 min, and were blocked with 10% goat serum for 1 h. The sections were incubated for 24 h at 4 °C with polyclonal rabbit anti-Nav1.9 (1:200; alomone labs). Then the sections were incubated with biotinylated griffonia simplicifolia Lectin I isolectin B4 (10 μg ml−1, Vector Laboratories, California, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. After incubation, sections were washed three times for 5 min in PBST (0.05% Tween20). Finally, incubated with Alexa-Fluor 488-nm (1:500, Invitrogen) and Alexa-Fluor 594 Streptavidin (1:200, Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). After being washed three times for 5 min in PBST, sections were mounted with coverslips. Fluorescence images were acquired with the FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Study approval

All of the animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Laboratory Animal Research set by Hunan Normal University and Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the College of Medicine, Hunan Normal University and Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed with PatchMaster v2x73 (HEKA Elektronik), Clampfit 9 (Version 9.2.0.09, AXON), IgorPro6 (Version 6.1.0.9, WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA), Prism 7 (Version 7.00, GraphPad Software), FV10-ASW (Version 01.07.03.00, Olympus, Japan) and Office Excel 2010 (Version 14.0.4760.1000, Microsoft, USA). All values are shown as mean ± S.E.M., and n represents the number of animals or cells examined. One-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA were used to assess the difference between multiple groups. Two grouped data were analyzed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test before t test analysis. If the data were normally distributed, a parametric t test was used. Otherwise, a nonparametric t test was used. In figure legends, statistical method to a specific experiment is mentioned, and the F, t, df (degree of freedom) and p-values are also shown. Significant levels were set at p < 0.05 and the exact p-values are presented in Supplementary Data 1. Statistical analyses were performed with Prism 7 (Version 7.00, GraphPad) software.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its Supplementary Information Files, or on request from the corresponding author. The source data underlying Fig. 1a, c–e, g, h, Fig. 2a–e, g, Fig. 3a, b, g–i, Fig. 4a, d–f, Fig. 5a–c, f–h, Fig. 6c and Supplementary Figs. 1b–f, Fig. 2a–d, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5i, Fig. 6 are provided as a Source Data file.

References

Treede, R. D. The international association for the study of pain definition of pain: as valid in 2018 as in 1979, but in need of regularly updated footnotes. Pain Rep. 3, e643 (2018).

Cox, J. J. et al. An SCN9A channelopathy causes congenital inability to experience pain. Nature 444, 894–898 (2006).

Leipold, E. et al. A de novo gain-of-function mutation in SCN11A causes loss of pain perception. Nat. Genet. 45, 1399–1404 (2013).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Transcriptional regulator PRDM12 is essential for human pain perception. Nat. Genet. 47, 803–808 (2015).

Nilsen, K. B. et al. Two novel SCN9A mutations causing insensitivity to pain. Pain 143, 155–158 (2009).

Cox, J. J. et al. Congenital insensitivity to pain: novel SCN9A missense and in-frame deletion mutations. Hum. Mutat. 31, E1670–E1686 (2010).

Yang, Y. et al. Mutations in SCN9A, encoding a sodium channel alpha subunit, in patients with primary erythermalgia. J. Med. Genet. 41, 171–174 (2004).

Fertleman, C. R. et al. SCN9A mutations in paroxysmal extreme pain disorder: allelic variants underlie distinct channel defects and phenotypes. Neuron 52, 767–774 (2006).

Dib-Hajj, S. D., Yang, Y., Black, J. A. & Waxman, S. G. The Na(V)1.7 sodium channel: from molecule to man. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 49–62 (2013).

Cao, L. et al. Pharmacological reversal of a pain phenotype in iPSC-derived sensory neurons and patients with inherited erythromelalgia. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 335ra356 (2016).

McDonnell, A. et al. Efficacy of the Nav1.7 blocker PF-05089771 in a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical study in subjects with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Pain 159, 1465–1476 (2018).

Zakrzewska, J. M. et al. Safety and efficacy of a Nav1.7 selective sodium channel blocker in patients with trigeminal neuralgia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal phase 2a trial. Lancet. Neurol. 16, 291–300 (2017).

Kingwell, K. Nav1.7 withholds its pain potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41573-019-00065-0 (2019).

Dib-Hajj, S. D., Cummins, T. R., Black, J. A. & Waxman, S. G. Sodium channels in normal and pathological pain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 33, 325–347 (2010).

Han, C., Huang, J. & Waxman, S. G. Sodium channel Nav1.8: emerging links to human disease. Neurology 86, 473–483 (2016).

Zhang, X. Y. et al. Gain-of-function mutations in SCN11A cause familial episodic pain. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93, 957–966 (2013).

Faber, C. G. et al. Gain-of-function Nav1.8 mutations in painful neuropathy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 19444–19449 (2012).

Rush, A. M., Cummins, T. R. & Waxman, S. G. Multiple sodium channels and their roles in electrogenesis within dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Physiol. 579, 1–14 (2007).

Renganathan, M., Cummins, T. R. & Waxman, S. G. Contribution of Na(v)1.8 sodium channels to action potential electrogenesis in DRG neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 86, 629–640 (2001).

Baker, M. D., Chandra, S. Y., Ding, Y., Waxman, S. G. & Wood, J. N. GTP-induced tetrodotoxin-resistant Na+ current regulates excitability in mouse and rat small diameter sensory neurones. J. Physiol. 548, 373–382 (2003).

Osteen, J. D. et al. Selective spider toxins reveal a role for the Nav1.1 channel in mechanical pain. Nature 534, 494–499 (2016).

Osteen, J. D., Sampson, K., Iyer, V., Julius, D. & Bosmans, F. Pharmacology of the Nav1.1 domain IV voltage sensor reveals coupling between inactivation gating processes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6836–6841 (2017).

Richards, K. L. et al. Selective NaV1.1 activation rescues Dravet syndrome mice from seizures and premature death. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E8077–E8085 (2018).

Chugunov, A. O. et al. Modular organization of alpha-toxins from scorpion venom mirrors domain structure of their targets, sodium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 19014–19027 (2013).

Ekberg, J. et al. muO-conotoxin MrVIB selectively blocks Nav1.8 sensory neuron specific sodium channels and chronic pain behavior without motor deficits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17030–17035 (2006).

Yang, S. et al. Discovery of a selective NaV1.7 inhibitor from centipede venom with analgesic efficacy exceeding morphine in rodent pain models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 17534–17539 (2013).

Kalia, J. et al. From foe to friend: using animal toxins to investigate ion channel function. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 158–175 (2015).

Catterall, W. A. et al. Voltage-gated ion channels and gating modifier toxins. Toxicon 49, 124–141 (2007).

Sanguinetti, M. C. et al. Heteropodatoxins: peptides isolated from spider venom that block Kv4.2 potassium channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 51, 491–498 (1997).

Nassar, M. A. et al. Nociceptor-specific gene deletion reveals a major role for Nav1.7 (PN1) in acute and inflammatory pain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 12706–12711 (2004).

Minett, M. S. et al. Distinct Nav1.7-dependent pain sensations require different sets of sensory and sympathetic neurons. Nat. Commun. 3, 791 (2012).

Hu, H. J. et al. The kv4.2 potassium channel subunit is required for pain plasticity. Neuron 50, 89–100 (2006).

Phuket, T. R. & Covarrubias, M. Kv4 channels underlie the subthreshold-operating A-type K-current in nociceptive dorsal root ganglion neurons. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2, 3 (2009).

Vasylyev, D. V., Han, C., Zhao, P., Dib-Hajj, S. & Waxman, S. G. Dynamic-clamp analysis of wild-type human Nav1.7 and erythromelalgia mutant channel L858H. J. Neurophysiol. 111, 1429–1443 (2014).

Bosmans, F., Milescu, M. & Swartz, K. J. Palmitoylation influences the function and pharmacology of sodium channels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20213–20218 (2011).

Zhang, M. M. et al. Co-expression of Na(V)beta subunits alters the kinetics of inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels by pore-blocking mu-conotoxins. Br. J. Pharmacol. 168, 1597–1610 (2013).

Salvatierra, J. et al. A disease mutation reveals a role for NaV1.9 in acute itch. J. Clin. Investig. 128, 5434–5447 (2018).

Stevens, M., Peigneur, S. & Tytgat, J. Neurotoxins and their binding areas on voltage-gated sodium channels. Front. Pharmacol. 2, 71 (2011).

Campos, F. V., Chanda, B., Beirao, P. S. & Bezanilla, F. Alpha-scorpion toxin impairs a conformational change that leads to fast inactivation of muscle sodium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 132, 251–263 (2008).

Capes, D. L., Goldschen-Ohm, M. P., Arcisio-Miranda, M., Bezanilla, F. & Chanda, B. Domain IV voltage-sensor movement is both sufficient and rate limiting for fast inactivation in sodium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 142, 101–112 (2013).

Xiao, Y. et al. Tarantula huwentoxin-IV inhibits neuronal sodium channels by binding to receptor site 4 and trapping the domain ii voltage sensor in the closed configuration. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27300–27313 (2008).

Liu, Z. et al. Structure and function of hainantoxin-III, a selective antagonist of neuronal tetrodotoxin-sensitive voltage-gated sodium channels isolated from the Chinese bird spider Ornithoctonus hainana. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 20392–20403 (2013).

Cummins, T. R., Howe, J. R. & Waxman, S. G. Slow closed-state inactivation: a novel mechanism underlying ramp currents in cells expressing the hNE/PN1 sodium channel. J. Neurosci. 18, 9607–9619 (1998).

Herzog, R. I., Cummins, T. R. & Waxman, S. G. Persistent TTX-resistant Na+ current affects resting potential and response to depolarization in simulated spinal sensory neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 86, 1351–1364 (2001).

Rush, A. M. et al. A single sodium channel mutation produces hyper- or hypoexcitability in different types of neurons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8245–8250 (2006).

Huang, J. et al. Sodium channel NaV1.9 mutations associated with insensitivity to pain dampen neuronal excitability. J. Clin. Investig. 127, 2805–2814 (2017).

Bennett, D. L., Clark, A. J., Huang, J., Waxman, S. G. & Dib-Hajj, S. D. The role of voltage-gated sodium channels in pain signaling. Physiol. Rev. 99, 1079–1151 (2019).

Zhou, X. et al. Electrophysiological and pharmacological analyses of Nav1.9 voltage-gated sodium channel by establishing a heterologous expression system. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 852 (2017).

Bonnet, C. et al. Maladaptive activation of Nav1.9 channels by nitric oxide causes triptan-induced medication overuse headache. Nat. Commun. 10, 4253 (2019).

Huang, J. et al. Gain-of-function mutations in sodium channel Na(v)1.9 in painful neuropathy. Brain 137, 1627–1642 (2014).

Leipold, E. et al. Cold-aggravated pain in humans caused by a hyperactive NaV1.9 channel mutant. Nat. Commun. 6, 10049 (2015).

Han, C. et al. Familial gain-of-function Nav1.9 mutation in a painful channelopathy. J. Neurol., Neurosurg., Psychiatry 88, 233–240 (2017).

Blair, N. T. & Bean, B. P. Roles of tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive Na+ current, TTX-resistant Na+ current, and Ca2+ current in the action potentials of nociceptive sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 22, 10277–10290 (2002).

Dib-Hajj, S. D. & Waxman, S. G. Diversity of composition and function of sodium channels in peripheral sensory neurons. Pain 156, 2406–2407 (2015).

Priest, B. T. et al. Contribution of the tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.9 to sensory transmission and nociceptive behavior. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9382–9387 (2005).

Maingret, F. et al. Inflammatory mediators increase Nav1.9 current and excitability in nociceptors through a coincident detection mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 131, 211–225 (2008).

Lolignier, S. et al. The Nav1.9 channel is a key determinant of cold pain sensation and cold allodynia. Cell Rep. 11, 1067–1078 (2015).

Dib-Hajj, S. D., Black, J. A. & Waxman, S. G. NaV1.9: a sodium channel linked to human pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 511–519 (2015).

Minett, M. S. et al. Endogenous opioids contribute to insensitivity to pain in humans and mice lacking sodium channel Nav1.7. Nat. Commun. 6, 8967 (2015).

Fjell, J. et al. Differential role of GDNF and NGF in the maintenance of two TTX-resistant sodium channels in adult DRG neurons. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 67, 267–282 (1999).

Rush, A. M. et al. Contactin regulates the current density and axonal expression of tetrodotoxin-resistant but not tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels in DRG neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 22, 39–49 (2005).

Liu, C. J. et al. Direct interaction with contactin targets voltage-gated sodium channel Na(v)1.9/NaN to the cell membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 46553–46561 (2001).

Rush, A. M. & Waxman, S. G. PGE2 increases the tetrodotoxin-resistant Nav1.9 sodium current in mouse DRG neurons via G-proteins. Brain Res. 1023, 264–271 (2004).

Ostman, J. A., Nassar, M. A., Wood, J. N. & Baker, M. D. GTP up-regulated persistent Na+ current and enhanced nociceptor excitability require NaV1.9. J. Physiol. 586, 1077–1087 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Patrick Delmas (Université de la Méditerranée, Marseille Cedex, France) for providing Nav1.9-KO mice, and Dr. Waxman SG (Yale University School of Medicine, West Haven, Connecticut, USA) for providing the floxed Nav1.7 mice and Nav1.8-Cre mice. This work was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation of China (31800655) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation funded project (2018M632968) to X.Z., the National Science Foundation of China (31570782, 31770832) and the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (14JJ1018) to Z.H.L., the National Science Foundation of China (31671301, 31871262) and the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1306000) to J.Y.L., and the National Science Foundation of China (31872718) to S.P.L.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. and T.B.M. conducted most of the experiments and analyzed the data, including peptide toxin purification, patch-clamp recording, mutagenesis, immunofluorescence, animal behavior tests, and data analysis; L.Y.Y. also conducted patch-clamp recording and animal behavior tests. L.L.L. conducted animal behavior tests. S.J.P., Z.Q.W., Z.X., Q.F.Z., L.W., and Y.Z.H. also conducted peptide toxin purification and patch-clamp recordings; M.Z.C. conducted MALDI–TOF mass spectrometry and data analysis; X.W.Z. designed the animal behavior tests. X.Z. and T.B.M. prepared the paper; X.Z., T.B.M., S.P.L., J.Y.L., and Z.H.L. designed the study and reviewed the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Stephen Waxman and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, X., Ma, T., Yang, L. et al. Spider venom-derived peptide induces hyperalgesia in Nav1.7 knockout mice by activating Nav1.9 channels. Nat Commun 11, 2293 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16210-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16210-y

This article is cited by

-

The mechanism of dentine hypersensitivity: Stimuli-induced directional cation transport through dentinal tubules

Nano Research (2023)

-

Neural Mechanisms Underlying the Coughing Reflex

Neuroscience Bulletin (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.