Abstract

Carbene-metal-amides are soluble and thermally stable materials which have recently emerged as emitters in high-performance organic light-emitting diodes. Here we synthesise carbene-metal-amide photoemitters with CF3-substituted ligands to show sky-blue to deep-blue photoluminescence from charge-transfer excited states. We demonstrate that the emission colour can be adjusted from blue to yellow and observe that the relative energies of charge transfer and locally excited triplet states influence the performance of the deep-blue emission. High thermal stability and insensitivity to aggregation-induced luminescence quenching allow us to fabricate organic light-emitting diodes in both host-free and host-guest architectures. We report blue devices with a peak external quantum efficiency of 17.3% in a host-free emitting layer and 20.9% in a polar host. Our findings inform the molecular design of the next generation of stable blue carbene-metal-amide emitters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) has continued for over 30 years since the discovery of electroluminescence from the fluorescent green emitter tris(8-hydroxyquinolinato)aluminium (Alq3)1. An OLED emits light via radiative recombination of strongly bound excitons formed from electrically injected charge pairs. For injected charges with uncorrelated spins, excitons are generated in a 3:1 ratio of spin-1 triplet (T) and spin-0 singlet (S) states. In the absence of spin–orbit coupling, only the singlets can relax to the ground state via photon emission, and the energy of triplets is wasted2. Luminescent harvesting of triplet states can be achieved in several ways. Use of heavy metal complexes with high spin–orbit coupling, notably of iridium(III) and platinum(II), enables photoemission via phosphorescence on the microsecond timescale3,4,5,6,7. Alternatively, compounds can be designed where the lowest-energy excited states, S1 and T1, are sufficiently close in energy for the thermal equilibrium between the two at typical operating temperatures to enable emission from the S1 state via (reverse) intersystem crossing. This process is termed E-type (or thermally activated) delayed fluorescence (TADF)8,9,10. The development of materials for blue OLEDs, however, remains particularly challenging, with high-energy bimolecular interactions involving long-lived triplet excitons implicated as one of the primary limits to operational lifetime11.

We have shown recently that linear, two-coordinated coinage metal complexes of the type (L)MX (M = Cu, Ag, Au) can show efficient photoluminescence (PL) via a delayed fluorescence mechanism, provided the ligand L is a strongly bound carbene capable of acting as π-acceptor and X is an electron-rich anion capable of acting as electron donor upon excitation12,13,14,15,16. Combinations of L = cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbene (CAAC)17,18 and X = carbazolate (Cz) have proved particularly successful and have become known as “carbene–metal–amide” (CMA)-type photoemitters14. These complexes are soluble in most organic solvents and sufficiently thermally stable to enable the fabrication of OLED devices by both solution processing and thermal vapour deposition techniques13,14,19,20. CMAs do not suffer from strong concentration quenching in the solid state, attributed to the lack of close metal–metal contacts, enabling the realization of host-free green devices with an external quantum efficiency (EQE or ηEQE) of 23.1%19. Due to the linear two-coordinate geometry, CMAs are conformationally flexible, with a low barrier for rotation about the metal-N σ-bond. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) is centred on the amide ligand, while the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) consists mainly of the p-orbital of the carbene C atom, with only a small metal contribution to both. Excitation of the molecule thus leads to a charge-transfer (CT) type excited state. Both frontier orbitals are spatially well separated, commensurate with a small ΔE(S1 − T1) energy gap for CT excitations. This arrangement enables luminescence quantum efficiencies to approach 100% coupled with short, sub-microsecond excitation lifetimes for triplet states. The emission process involved has been subjected to a number of theoretical and spectroscopic investigations21,22,23; modelling has shown that, upon rotation about the metal-N σ-bond, the ΔE(S1 − T1) energy gap decreases and at high twist angles may approach zero13,20,21,22,23.

As a consequence of the high polarity of CMA compounds, emission energies are sensitive to their molecular environment; for example, this has allowed “tuning” of electroluminescence by suitable host media from green to sky-blue19. However, much larger changes in emission energies can be achieved by altering the carbazole substitution pattern. For the (AdCAAC)AuCz archetype, the HOMO is almost entirely located on the Cz donor. The introduction of electron-withdrawing groups to this moiety therefore influences the HOMO more than the LUMO and widens the HOMO–LUMO gap, resulting in a shift towards blue emission14,24.

Here we report the synthesis of new Au-bridged emitters that enable blue host-free OLEDs with ηEQE of 17.3% (λem,max = 473 nm), as well as host-guest devices with a peak wavelength of 450 nm and an ηEQE of up to 20.9%. At practical brightness levels of 100 cd m−2, we achieve ηEQE = 17.2% and ηEQE = 17.8% for the best host-free and host-guest devices, respectively.

Results

Synthesis and structures

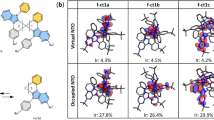

We prepared the CF3-substituted carbazolate complexes 1 (R1 = CF3, R2 = tBu) and 2 (R1 = R2 = CF3) (Fig. 1) from (AdCAAC)AuCl and the corresponding carbazoles in the presence of KOtBu, following our previously published procedures12,13,14. Complexes 1 and 2 were prepared on a 5-g scale as white solids that are stable in air and in solution for long period of time. They possess good solubility in aromatic solvents (toluene, chlorobenzene, 1,2-difluorobenzene), THF, dichloromethane, or DMF, but are insoluble in hexane. We chose the adamantyl-substituted CAAC ligand (AdCAAC) since its high steric hindrance provides good thermal stability and high PL intensities. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, 5% weight loss) showed decomposition temperatures of 325 °C for 1 and 364 °C for 2 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The data for the known14 green (R1 = R2 = H, here complex 3) and yellow emitters (R1 = R2 = tBu, here complex 4) are included for comparison.

The structures of 1 and 2 were confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Fig. 1). Both complexes show a two-coordinate geometry for the gold atom with negligible deviation from linearity (Table 1); there are no close Au···Au contacts. The HOMO–LUMO overlap is directly related to the donor–acceptor distance C1(CAAC)···N2(Cz), which is 0.02 Å shorter in 1 than in 2. This is likely to impact radiative rates and ΔE(S1 − T1)13,24. The torsion angle N1–C1–N2–C28 for 1 of 14.3° is similar to those in 3/4, whereas for 2 it is nearly 0°, possibly due to intermolecular interactions in the crystal (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Electrochemical and photophysical properties

The redox behaviour of 1 and 2 was analysed in acetonitrile solution using [nBu4N]PF6 as the supporting electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 3). The electrochemical data are shown in Table 2. Both 1 and 2 show a quasi-reversible, carbene ligand-centred reduction process. Complex 1 has the smallest peak-to-peak separation (ΔEp) in the series (73 mV), indicating higher stability of the reduced species. The reduction potential is sensitive to the number of Cz–CF3 groups and leads to a greater LUMO stabilization for 1 and 2 compared with 3/4. Both 1 and 2 show irreversible carbazole-centered oxidation processes (Supplementary Fig. 3). The HOMO levels from the onset of the first oxidation potentials25 are −5.85 and −6.12 eV for 1 and 2, respectively, compared to −5.61 eV for 3 and −5.47 eV for 4.

The UV–vis absorption spectra of 1 and 2 were measured in THF (Fig. 2). All complexes show π–π* transitions at ca. 270 nm, which can be ascribed to intra-ligand (IL) transitions of the CAAC carbene, and weaker progressions around 300–310 and 360–375 nm ascribed to π–π* IL transitions of the amide. The broad, low-energy absorption band is assigned largely to ligand-to-ligand CT transitions {π(carbazole)–π*(CAAC)}. The onset of the absorption CT band and its peak position exhibit negative solvatochromism and blue-shifting by ca. 20 nm on each step of the series 4 → 3 → 1 → 2, with decreasing electron-donor character of the amide ligand. The observed trend in absorption spectra is largely consistent with the increase of the band gap (ΔE, Table 2) identified by cyclic voltammetry (CV) (see below).

On excitation with UV light (λexc = 365 nm), 1 and 2 as crystals show blue PL at λmax < 440 nm, dominated by structured emission. This emission is similar to that observed for all complexes in frozen 2-MeTHF at 77 K (Supplementary Fig. 4) and can be ascribed to local (i.e. ligand-centred) triplet excited states (3LE). The behaviour of 1 and 2 contrasts with that of 3 and 4 (Supplementary Fig. 5), which show unstructured CT emission in the crystalline phase. The emission red-shifts in neat amorphous thin films and in liquid solution, becoming broad and unstructured. We ascribe this emission to luminescence from CT excited states, which represent the lowest-energy triplet excitation in these less-constrained environments. The energy of the CT transition (ECT), measured from its high-energy onset in toluene solution, increases with increasing electron-acceptor strength of the carbazole substituents, from 2.62 eV for 4 to 3.15 eV for 2. The effect of carbazole substitution on the 3LE emission energy (ELE), measured from its high-energy onset in frozen MeTHF, is less pronounced, with a change of only 0.11 eV between 4 and 2 (Table 3).

The CT excited-state energy and lifetime of 1 are environment dependent (Table 3). At 298 K in toluene solution, the emission lifetime is 740 ns. The peak emission energy blue-shifts by 60 meV in neat solid samples and the lifetime increases to 1 μs. In DPEPO host, which increases the peak emission energy by a further 110 meV, the lifetime increases to around 20 μs. On cooling to 77 K, the excited-state lifetimes of solid samples increase to 600–700 μs.

For 2, excited-state lifetimes at 298 K follow a similar trend and are longer. The emission in toluene solution exhibits a featureless CT character with τ = 11.5 μs. In neat solid films, the emission shows a blue-shift with a structure associated with 3LE emission. On cooling solid samples to 77 K, lifetimes increase to over 2 ms and the 3LE character of the emission becomes dominant. The energies of the CT and 3LE states in MeTHF were measured at 298 and 77 K, respectively (Table 3). For complexes 1, 3 and 4, the Cz 3LE triplet state is 0.1–0.3 eV higher than the CT state, leading to negative energy gap values ΔE(CT–3LE), which increase in the order 1 < 3 < 4. We thus observe that emission lifetime is correlated with ECT, increasing as the ΔE(CT–3LE) gap narrows. 3LE phosphorescence is observed in environments where the lowest CT states are no longer the lowest-energy triplet excitations, and the PL quantum yield is reduced. For instance, the PL quantum yield in solution (298 K) drops from near unity for 1 to 61% for 2.

Device characterization and performance

OLEDs utilizing complexes 1–4 as emitters were fabricated by thermal vapour deposition under high vacuum (10−7 Torr) on ITO-coated glass substrates with a sheet resistance of 15 Ω/⎕. Two device architectures were employed, shown in Fig. 3 together with chemical structures for the materials used. Architecture A was used for the blue-emitting complexes 1 and 2. A 40-nm layer of 1,1-bis{4-[N,N-di(4-tolyl)amino]phenyl}cyclohexane (TAPC) functions as a hole transport layer, with a 5-nm layer of 9,9′-biphenyl-2,2′-diylbis-9H-carbazole (o-CBP) acting as an exciton blocking layer due to its slightly higher T1 energy and deeper HOMO. The 30-nm thick emissive layer (EML) was composed of either pure 1 and 2 in a host-free configuration, or the emitting material doped at 20 wt% into a bis[2-diphenylphosphino)phenyl]ether oxide (DPEPO) host. A 40-nm layer of diphenyl-4-triphenylsilyl-phenylphosphine oxide (TSPO1) was used as the electron-transporting and hole-blocking layer.

Devices containing the green emitter 3 and yellow emitter 4 were fabricated according to architecture B, using a 40-nm TAPC layer as a hole transport layer and a 20-nm EML utilizing 3 or 4 in a host-free configuration or doped at 20 wt.% in either DPEPO or 1,3,5-tris(carbazol-9-yl)benzene (TCP). A 10-nm layer of 1,4-bis(triphenylsilyl)benzene (UGH2) was used as a hole-blocking layer and 40 nm of 1,3,5-tris(2-N-phenylbenzimidazole-1-yl)benzene (TPBi) as an electron-transport layer.

Electroluminescence spectra for devices based on 1 are shown in Fig. 4; peak wavelengths (λPeak) and CIE colour space coordinates are summarized in Table 4. Host-free 1 devices show λPeak = 473 nm and CIE (0.18, 0.27). The electroluminescence can be blue-shifted by dispersal in a low-polarity host material, here o-CBP, and further blue-shifted by utilizing a high-polarity host material, here DPEPO, to obtain a peak wavelength of 450 nm (CIE 0.17, 0.17).

a Normalized electroluminescence spectra from devices incorporating 1 in host-free and host-guest structures. b CIE colour space chart depicting the apparent colour of electroluminescence from OLED devices incorporating CMA emitters in host-free and host-guest structures. CIE coordinates for 3 in TCP host and host-free structures are reproduced from ref. 19.

Similar shifts are achievable for 3 and 4, utilizing TCP/DPEPO as the low/high-polarity host material, respectively, in agreement with our previous report of 3 in mCP host (1,3-bis(N-carbazolyl)benzene). Host-free 2 devices show deep blue electroluminescence with λPeak = 423 nm and CIE (0.16, 0.05); however, the emission appears to be of 3LE character (Supplementary Fig. 6) and the devices undergo rapid degradation, with an additional spectral feature at 580 nm arising on an ~1 s timescale. Full device characterization was therefore only carried out using 1, 3 and 4 as emitters.

Devices based on 1 show low turn-on voltages (reported as the applied bias at which luminance equals 1 cd m−2) of VOn = 3.7 V for 1, which indicates an absence of large barriers to charge injection into the emitting layer even in host-free architectures. Figure 5 shows the current density–voltage and luminance–voltage characteristics of champion 1 devices in both host-free and host-guest environments. We calculated EQE (Figure 6, ηEQE) by measuring the on-axis irradiance and assuming a Lambertian emission profile. Slightly super-Lambertian emission was previously observed for CMA-based OLEDs. We therefore consider that the ηEQE estimates presented here are conservative19. The peak ηEQE = 17.3% for blue host-free 1 devices is an indication of the insensitivity of gold-bridged CMA materials to aggregation quenching. The efficiency rises slightly to ηEQE = 20.9% on dilution in a DPEPO host. Host-free devices exhibit reduced roll-off compared to host-guest devices, as might be expected from a reduction in triplet density under operation. Equivalent data for compounds 3 and 4 are shown in Supplementary Figs. 7–8.

We measured the operating lifetimes of the host-free and host-guest OLED devices for complexes 1, 3 and 4 as the time taken to reduce the initial brightness from 100 to 95 cd/m2 (LT95, Supplementary Fig. 9). The OLED devices with DPEPO as a host exhibited the shortest LT95 values of less than 4 min. Host-free devices showed slightly longer lifetimes and devices based on 3 and 4 tended to be more stable than 1. In the low-polarity host materials, o-CBP for complex 1 and TCP for complexes 3 and 4, OLED devices based on complexes 1 and 4 showed only marginal improvements, whereas significant enhancement for LT95 (2 h) was measured for complex 3. This result can be correlated with the presence of the tBu-group for both materials 1 and 4 and instability of the cation-radical species for all complexes (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

By varying the electron-donating or -withdrawing nature of carbazole substituents the HOMO–LUMO gap of CMA-type photoemitters can be readily adjusted and the electroluminescence colour can be tuned from yellow (CIE coordinates 0.35, 0.53) to deep blue (CIE 0.16, 0.05). In addition, the CT energy is sensitive to the host environment. These effects enable control of the energy gap between CT and LE excitations. From transient PL measurements, we establish that rapid triplet luminescence is correlated with a larger ΔE(CT–3LE) gap. Approaching resonance between the CT state and the amide triplet at around 3 eV leads to a marked reduction in performance, in contrast with the current models of all-organic TADF luminescence26,27. The effect is most clearly seen in the case of 2 with the most electronically depleted carbazole ligand, where in some environments the 3LE is the lowest-lying triplet. Where this is the case, long-lived structured phosphorescence is observed and device performance is reduced. However, the combined approach of tuning the molecular design and host environment allows devices to operate below this ceiling. We have fabricated efficient blue host-guest OLEDs with a peak ηEQE of 20.9% and peak electroluminescence wavelength of 450 nm (CIE coordinates [0.17, 0.17]). We also achieved a peak ηEQE of 17.3% for blue OLEDs (CIE [0.18, 0.27]) in host-free architectures. Host-free and host-guest (o-CBP) devices exhibit slow roll-off, achieving ηEQE at a brightness of 100 cd m−2 of 17.8% and 17.2%, respectively. The host-free approach can simplify the design of blue OLEDs, but the molecular design of the emitter has to be very carefully considered. We demonstrate that CMA complex 3 exhibits encouraging LT95 values of several hours (CIE [0.24, 0.42]), while installing tBu substituents in the Cz 3,6-positions reduces LT95 values to minutes. These findings provide a practical guide for the molecular design of the next generation of stable blue emitters for display applications.

Methods

General

Solvents were distilled and dried before use. Sodium tert-butoxide and 3-(tert-butyl)phenylboronic acid, were purchased from FluoroChem; SPhos Pd G2 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. The carbene ligand (AdL)28,29,30, N-(2-chloro-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)acetamide (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11), 6-(tert-butyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-9- acetylcarbazole (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13) and 6-(tert-butyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-9H-carbazole (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15)31, and complexes (AdL)MCl (M = Cu and Au)32 were obtained according to literature procedures, see Supplementary Methods. 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker Avance DPX-300 MHz NMR spectrometer. 1H NMR spectra (300.13 MHz) and 13C{1H} (75.47 MHz) were referenced to CD2Cl2 at δ 5.32 (13C, δ 53.84) and CDCl3 at δ 7.26 (δ 13C 77.16) ppm. All electrochemical experiments were performed using an Autolab PGSTAT 302N computer-controlled potentiostat. CV was performed using a three-electrode configuration consisting of either a glassy carbon macrodisk working electrode (GCE) (diameter of 3 mm; BASi, Indiana, USA) combined with a Pt wire counter electrode (99.99%; GoodFellow, Cambridge, UK) or an Ag wire pseudoreference electrode (99.99%; GoodFellow, Cambridge, UK). The GCE was polished between experiments using alumina slurry (0.3 μm), rinsed in distilled water and subjected to brief sonication to remove any adhering alumina microparticles. The metal electrodes were then dried in an oven at 100 °C to remove residual traces of water, the GCE was left to air dry and residual traces of water were removed under vacuum. The Ag wire pseudoreference electrodes were calibrated to the ferrocene/ferrocenium couple in MeCN at the end of each run to allow for any drift in potential, following IUPAC recommendations33. All electrochemical measurements were performed at ambient temperatures under an inert Ar atmosphere in an MeCN-containing complex under study (0.14 mM) and supporting electrolyte [n-Bu4N][PF6] (0.13 mM). Data were recorded with Autolab NOVA software (v. 1.11). Elemental analyses were performed by London Metropolitan University. Mass spectrometry data were obtained using APCI(ASAP) (Atmospheric Solids Analysis Probe) at the National Mass Spectrometry Facility at Swansea University.

Synthesis of complex 1

In a Schlenk tube, (AdL)AuCl (3.52 g, 5.77 mmol), 6-(tert-butyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-9H-carbazole (1.68 g, 5.77 mmol) and tBuONa (0.56 g, 5.83 mmol) were stirred in THF (75 mL) for 6 h. The mixture was filtered through Celite. The filtrate was concentrated and washed with hexane to afford the product as a white solid. Yield: 93% (4.65 g, 5.37 mmol) after annealing at 140 °C under vacuum. See Supplementary Fig. 16.

1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 8.20 (s, 1H, CH4 Cz), 7.99 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H CH5 Cz), 7.71 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, p-CH Dipp), 7.47 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, m-CH Dipp), 7.30 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.0 Hz, 1H, CH7 Cz), 7.25 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.5 Hz 1H, CH2 Cz), 6.87 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, CH8 Cz), 6.42 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, CH1 Cz), 4.31 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 2H, CH2 Adamantyl), 2.90 (Sept, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H, CH iPr Dipp), 2.45 (pseudo s, 2H + 1 H, CH2 CAAC overlapping with CH Adamantyl), 2.19–1.86 (m, 11H, Adamantyl), 1.44 (s, 6H, C(CH3)2 CAAC), 1.39 (s, 9H, tBu), 1.36–1.30 (m, 12H, CH3 iPr Dipp). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 244.1 (s, C: CAAC), 151.9 (s, Cq Cz), 148.8 (s, Cq Cz), 146.2 (s, o-C Dipp), 140.4 (s, C–tBu), 136.7 (s, i-C Dipp), 130.0 (s, p-CH Dipp), 26.8 (q, J = 270.3 Hz, CF3), 123.9 (s, Cq Cz), 123.8 (s, Cq Cz), 123.0 (s, CH7 Cz), 119.8 (q, J = 3.2 Hz, CH2 Cz), 117.1 (q, J = 31.3 Hz, C–CF3 overlapping with CH4 Cz), 116.9 (q, J = 4.2 Hz, CH4 Cz overlapping with C–CF3), 115.9 (s, CH5 Cz), 114.0 (s, CH1 Cz), 113.9 (s, CH8 Cz), 77.6 (s, s, C(CH3)2 CAAC), 64.5 (s, C–C: CAAC), 49.1 (s, CH2 CAAC), 39.4 (s, Adamantyl), 37.6 (s, Adamantyl), 35.8 (s, Adamantyl), 34.8 (s, 2 C overlapped, C(CH3)3 and CH Adamantyl) 32.2 (s, C(CH3)3) 29.6 m, 2 C overlapped, C(CH3)2 and CH iPr Dipp), 28.6 (s, Adamantyl), 27.7 (s, Adamantyl), 26.5 (s, CH3 iPr Dipp), 23.4 (s, CH3 iPr Dipp). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ -59.1. Anal. Calcd. for C44H54AuF3N2 (864.89): C, 61.10; H, 6.29; N, 3.24. Found: C, 61.35; H, 6.07; N, 3.43. C44H54AuF3N2H theoretical [M + H+] = 865.3983, HRMS (APCI(ASAP)) = 865.3997.

Synthesis of complex 2

In a Schlenk tube, (AdL)AuCl (0.78 g, 1.28 mmol), 3,6-bis(trifluoromethyl)-9H-carbazole (0.373 g 1.28 mmol) and tBuONa (0.140 mg 1.45 mmol) were stirred in THF (40 mL) for 6 h. The mixture was filtered through Celite. The filtrate was concentrated and washed with hexane to afford the product as a white solid. Yield: 85% (0.95 g, 1.08 mmol) after annealing at 140 °C under vacuum. See Supplementary Fig. 17.

1H NMR (300 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 8.27 (s, 2H, CH4 Cz), 7.72 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, p-CH Dipp), 7.48 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, m-CH Dipp), 7.40 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H, CH2 Cz), 6.73 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H, CH1 Cz), 4.27 (d, J = 12.7 Hz, 2H, CH2 Adamantyl), 2.89 (sept, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H, CH iPr Dipp), 2.44 (pseudo s, 2 H + 1H, CH2 CAAC overlapping with CH Adamantyl), 2.20–1.99 (m, 7H, Adamantyl), 1.97–1.85 (m, 4H, Adamantyl), 1.44 (s, 6H, C(CH3)2 CAAC), 1.40–1.26 (m, 12H, CH3 iPr Dipp). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 243.5 (s, C: CAAC), 152.3 (s, Cq Cz), 146.2 (s, o-C Dipp), 136.7 (s, i-C Dipp), 130.1 (s, p-CH Dipp), 126.4 (q, J = 270.7 Hz, CF3), 125.8 (s, m-CH Dipp), 123.6 (s, Cq Cz), 121.3 (q, J = 3.3 Hz, CH2 Cz), 118.8 (q, J = 31.5 Hz, C–CF3), 117.5 (q, J = 4.1 Hz, CH4 Cz), 114.7 (s, CH1 Cz), 77.8 (s, C(CH3)2 CAAC), 64.5 (s, C–C: CAAC), 49.0 (s, CH2 CAAC), 39.3 (s, Adamantyl), 37.6 (s, Adamantyl), 35.9 (s, Adamantyl), 34.7 (s, Adamantyl), 29.6 (m, 2 C overlapped, C(CH3)2 and CH iPr Dipp), 28.6 (s, Adamantyl), 27.7 (s, Adamantyl), 26.5 (s, CH3 iPr Dipp), 23.3 (s, CH3 iPr Dipp). 19F NMR (282 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ -59.6. Anal. Calcd. for C41H45AuF6N2 (876.78): C, 56.17; H, 5.17; N, 3.20. Found: C, 55.83; H, 5.38; N, 3.02. C41H45AuF6N2H theoretical [M + H+] = 877.3231, HRMS (APCI(ASAP)) = 877.3241.

Photophysical characterization

Solution UV–visible absorption spectra were recorded using a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 35 UV/vis spectrometer. UV–vis spectra of solid films were recorded using an Agilent 8453 UV–visible spectrophotometer. PL measurements for MeTHF solutions at 298 and 77 K were recorded on a Fluorolog Horiba Jobin Yvon spectrofluorometer. PL measurements for solid films were recorded using an Edinburgh Instruments FLS980 spectrometer. Photoluminescent quantum yield was measured for toluene solutions using an Edinburgh Instruments FS5 spectrometer with 350 nm excitation wavelength for complex 1 (1 mg mL−1) and 2 (0.3 mg mL−1), and 400 nm excitation wavelength for complexes 3 (0.5 mg mL−1) and 4 (0.5 mg mL−1). Toluene solutions have been prepared in a nitrogen glovebox from freshly distilled toluene and measured in a 1-cm screw-cap quartz cuvette.

Transient PL measurements

Time-resolved PL spectra of solid films were recorded using an electrically gated intensified charge-coupled device (ICCD) camera (Andor iStar DH740 CCI-010) connected to a calibrated grating spectrometer (Andor SR303i). Pulsed 400-nm photoexcitation was provided by second harmonic generation in a BBO crystal from the fundamental 800 nm output (pulse width = 80 fs) of a Ti:Sapphire laser system (Spectra Physics Solstice), at a repetition rate of 1 kHz. A 425-nm long-pass filter (Thorlabs) was used to prevent scattered laser signals from entering the camera. Temporal evolution of the PL emission was obtained by stepping the ICCD gate delay with respect to the excitation pulse. The minimum gate width of the ICCD was ~5 ns.

The toluene solution time-resolved fluorescence data at 298 K were collected on a time-correlated single-photon counting Fluorolog Horiba Jobin Yvon spectrofluorometer using Horiba Jobin Yvon DataStation v2.4 software. A NanoLED of 370 nm was used as excitation source, with an instrument response function width of 2 ns. The data were analysed using Horiba Jobin Yvon DAS6 v6.3 software.

The neat film and host-guest time-resolved fluorescence data at 77 K were collected on an Edinburgh Instruments FS5 spectrofluorometer using a 5-W microsecond Xe flash lamp with a repetition rate of 100 Hz (360 nm excitation wavelength).

OLED fabrication and characterization

OLED devices were fabricated by high-vacuum (10−7 Torr) thermal evaporation on ITO-coated glass substrates with a sheet resistance of 15 Ω/⎕. Substrates were cleaned by sonication in non-ionic detergent, deionised water, acetone and isopropyl alcohol and subjected to an oxygen plasma treatment for 10 min. Layers were deposited at rates of 0.1–2 Ås−1. o-CBP was synthesized according to the literature procedure34. TAPC, TCP and UGH2 were purchased from Luminescence Technology Corp. TPBi, DPEPO and TSPO1 were purchased from Shine Materials. All purchased materials were used as received. OLED current density–voltage measurements were made using a Keithley 2400 source-meter unit. The luminance was measured on-axis using a 1-cm2 calibrated silicon photodiode at a distance of 15 cm from the front face of the OLED. Electroluminescence spectra were measured using a calibrated OceanOptics Flame spectrometer. Lifetime measurements were measured with a Keithley 2400 source-meter unit and a 0.75-cm2 silicon photodiode. The devices were held under rough vacuum (~10−3 Torr).

Data availability

The data underlying this publication are available through the following web link: https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.49735.

References

Tang, C. W. & VanSlyke, S. A. Organic electroluminescent diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 51, 913–915 (1987).

Yersin, H., Rausch, A. F., Czerwieniec, R., Hofbeck, T. & Fischer, T. The triplet state of organo-transition metal compounds. Triplet harvesting and singlet harvesting for efficient OLEDs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 255, 2622–2652 (2011).

Baldo, M. A. et al. Highly efficient phosphorescent emission from organic electroluminescent devices. Nature 395, 151–154 (1998).

Baldo, M. A., Adachi, C. & Forrest, S. R. Transient analysis of organic electrophosphorescence. II. Transient analysis of triplet-triplet annihilation. Phys. Rev. B 62, 10967–10977 (2000).

Evans, R. C., Douglas, P. & Winscom, C. J. Coordination complexes exhibiting room-temperature phosphorescence: evaluation of their suitability as triplet emitters in organic light emitting diodes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 250, 2093–2126 (2006).

Schulz, L. et al. Importance of intramolecular electron spin relaxation in small molecule semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 84, 085209 (2011).

Li, T. Y. et al. Rational design of phosphorescent iridium(III) complexes for emission color tunability and their applications in OLEDs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 374, 55–92 (2018).

Wong, M. Y. & Zysman-Colman, E. Purely organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605444 (2017).

Bizzarri, C., Hundemer, F., Busch, J. & Bräse, S. Triplet emitters versus TADF emitters in OLEDs: a comparative study. Polyhedron 140, 51–66 (2018).

Bizzarri, C., Spuling, E., Knoll, D. M., Volz, D. & Bräse, S. Sustainable metal complexes for organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs). Coord. Chem. Rev. 373, 49–82 (2018).

Giebink, N. C. et al. Intrinsic luminance loss in phosphorescent small-molecule organic light emitting devices due to bimolecular annihilation reactions. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 044509 (2008).

Romanov, A. S. et al. Copper and gold cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbene complexes with sub-microsecond photoemissions: Structure and substituent effects on redox and luminescent properties. Chemistry 23, 4625–4637 (2017).

Romanov, A. S. et al. Mononuclear silver complexes for efficient solution and vacuum-processed OLEDs. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6, 1801347 (2018).

Di, D. et al. High-performance light-emitting diodes based on carbene-metal-amides. Science 356, 159–163 (2017).

Shi, S. et al. Highly efficient photo- and electroluminescence from two-coordinate Cu(I) complexes featuring nonconventional N-heterocyclic carbenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 3576–3588 (2019).

Hamze, R. et al. Eliminating nonradiative decay in Cu(I) emitters: >99% quantum efficiency and microsecond lifetime. Science 363, 601–606 (2019).

Soleilhavoup, M. & Bertrand, G. Cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbenes (CAACs): stable carbenes on the rise. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 256–266 (2015).

Melaimi, M., Jazzar, R., Soleilhavoup, M. & Bertrand, G. Cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbenes (CAACs): recent developments. Angew. Chem. 56, 10046–10068 (2017).

Conaghan, P. J. et al. Efficient vacuum-processed light-emitting diodes based on carbene–metal–amides. Adv. Mater. 30, 1802285 (2018).

Romanov, A. S. et al. Dendritic carbene metal carbazole complexes as photoemitters for fully solution-processed OLEDs. Chem. Mater. 31, 3613–3623 (2019).

Thompson, S., Eng, J. & Penfold, T. J. The intersystem crossing of a cyclic (alkyl)(amino) carbene gold (i) complex. J. Chem. Phys. 149, 014304 (2018).

Taffet, E. J., Olivier, Y., Lam, F., Beljonne, D. & Scholes, G. D. Carbene–metal–amide bond deformation, rather than ligand rotation, drives delayed fluorescence. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 1620–1626 (2018).

Föller, J. & Marian, C. M. Rotationally assisted spin-state inversion in carbene–metal–amides is an artifact. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 5643–5647 (2017).

Hamze, R. et al. ‘Quick-Silver’ from a systematic study of highly luminescent, two-coordinate, d10 coinage metal complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8616–8626 (2019).

Cardona, C. M., Li, W., Kaifer, A. E., Stockdale, D. & Bazan, G. C. Electrochemical considerations for determining absolute frontier orbital energy levels of conjugated polymers for solar cell applications. Adv. Mater. 23, 2367–2371 (2011).

Zhang, Q. et al. Nearly 100% internal quantum efficiency in undoped electroluminescent devices employing pure organic emitters. Adv. Mater. 27, 2096–2100 (2015).

Rao, J. et al. Achieving deep-blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence in nondoped organic light-emitting diodes through a spiro-blocking strategy. ACS Omega 4, 1861–1867 (2019).

Lavallo, V., Canac, Y., Prasang, C., Donnadieu, B. & Bertrand, G. Stable cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbenes as rigid or flexible, bulky, electron-rich ligands for transition-metal catalysts: a quaternary carbon atom makes the difference. Angew. Chem. 44, 5705–5709 (2005).

Jazzar, R. et al. Intramolecular “hydroiminiumation” of alkenes: application to the synthesis of conjugate acids of cyclic alkyl amino carbenes (CAACs). Angew. Chem. 46, 2899–2902 (2007).

Jazzar, R., Bourg, J.-B., Dewhurst, R. D., Donnadieu, B. & Bertrand, G. Intramolecular “hydroiminiumation and -amidiniumation” of alkenes: a convenient, flexible, and scalable route to cyclic iminium and imidazolinium salts. J. Org. Chem. 72, 3492–3499 (2007).

Gantenbein, M., Hellstern, M., Pleux, L. L., Neuburger, M. & Mayor, M. New 4,4′-bis(9-carbazolyl)−biphenyl derivatives with locked carbazole−biphenyl junctions: high-triplet state energy materials. Chem. Mater. 27, 1772–1779 (2015).

Romanov, A. S. & Bochmann, M. Gold(I) and Gold(III) complexes of cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbenes. Organometallics 34, 2439–2454 (2015).

Gritzner, G. & Kůta, J. Recommendations on reporting electrode potentials in nonaqueous solvents: IUPC commission on electrochemistry. Electrochim. Acta 29, 869–873 (1984).

Zyryanov, G. V., Kovalev, I. S., Egorov, I. N., Rusinov, V. L. & Chupakhin, O. N. Synthesis of symmetrical dicarbazole-biphenyls, components of phosphorescent organic light-emitting diodes (PHOLEDs) using organocuprates. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 47, 571–574 (2011). Translated from Khimiya Geterotsiklicheskikh Soedinenii 5, 692–695 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC, Grant No. EP/M005143/1), the Royal Society, the European Research Council (ERC) and Samsung Display Corp. (SDC). P.J.C. acknowledges EPSRC for PhD studentship funding. C.S.B.M. acknowledges the Royal Society (RGF\EA\180041) and St John’s College, Cambridge. M.B. is an ERC Advanced Investigator Award holder (Grant No. 338944-GOCAT). D.C. and S.T.E.J. acknowledge support from the Royal Society (grant nos. UF130278 and RG140472). A.S.R. acknowledges support from the Royal Society (Grant Nos. URF\R1\180288 and RGF\EA\181008). We thank the National Mass Spectrometry Facility at Swansea University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.J.C. and C.S.B.M. developed and characterized the OLED devices. C.S.B.M. performed the OLED operating lifetime test. A.S.R. and F.C. performed the molecular design and synthesis. A.S.R. performed X-ray crystallography, TGA and electrochemistry. A.S.R. and F.C. performed initial steady-state photoluminescence studies. C.S.B.M. and S.J. carried out the ns–μs transient and additional steady-state photoluminescence studies. D.C., M.B. and A.S.R. planned the project and designed the experiments. P.J.C., C.S.B.M., D.C., M.B., N.C.G. and A.S.R. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results, analysis of the data and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Conaghan, P.J., Matthews, C.S.B., Chotard, F. et al. Highly efficient blue organic light-emitting diodes based on carbene-metal-amides. Nat Commun 11, 1758 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15369-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15369-8

This article is cited by

-

Copper(I) complexes with planar chirality realize efficient circularly polarized electroluminescence

Science China Chemistry (2023)

-

Large-area display textiles integrated with functional systems

Nature (2021)

-

Advanced Side-Impermeability Characteristics of Fluorinated Organic-Inorganic Nanohybrid Materials for Thin Film Encapsulation

Macromolecular Research (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.