Abstract

High-performance catalysts are extremely required for controlling NO emission via selective catalytic reduction (SCR), and to acquire a common structural feature of catalytic sites is one key prerequisite for developing such catalysts. We design a single-atom catalyst system and achieve a generic characteristic of highly active SCR catalytic sites. A single-atom Mo1/Fe2O3 catalyst is developed by anchoring single acidic Mo ions on (001) surfaces of reducible α-Fe2O3, and the individual Mo ion and one neighboring Fe ion are thus constructed as one dinuclear site. As the number of the dinuclear sites increases, SCR rates increase linearly but the apparent activation energy remains almost unchanged, evidencing the identity of the dinuclear active sites. We further design W1/Fe2O3 and Fe1/WO3 and find that tuning acid or/and redox properties of dinuclear sites can alter SCR rates. Therefore, this work provides a design strategy for developing improved SCR catalysts via optimizing acid-redox properties of dinuclear sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NO with NH3 over V2O5-based catalysts is a widely used technology for controlling NO emission from stationary sources1. The increasingly stringent emission regulations demand the development of high-performance SCR catalysts available for various harsh conditions. However, a common structural feature of active catalytic sites (ACSs), as well as reaction mechanisms, is still obscure2,3,4,5,6, which becomes one of the main obstacles for developing such catalysts.

The nature of ACSs has been extensively studied to achieve the generic feature of ACSs to develop highly active catalysts since V2O5-based catalysts were applied for SCR in 1970s. It is commonly accepted that highly active catalysts require ACSs to simultaneously possess acid-redox features2,3,4, but the origins of the acid-redox properties, provided solely by one mononuclear site or respectively by two adjacent metal sites, i.e., one dinuclear site, are still highly debated2,3,7,8. Even for typical V2O5-based catalysts, there is little consensus on the structure of ACSs. Marberger et al.3 identified ACS as one mononuclear vanadium site, which serves not only as one Lewis acid site for NH3 adsorption, but also as one redox site to close a SCR cycle, similar to the ACS structure proposed by Ramis et al.7. However, Topsøe et al.2,9,10. identified an adjacent dinuclear vanadium site as ACS, which was subsequently used as a structural model to describe SCR mechanisms1,5. Went et al.8,11 confirmed the coexistence of monomeric vanadyl and polymeric vanadate species including dimers on V2O5/TiO2 surfaces, all of which were catalytically active in SCR. These discrepancies in identification of ACSs have mainly arisen from site-averaged information obtained from the studied catalysts without uniform active sites.

Single-atom catalysts with uniform ACSs are favorable for studying the nature of ACSs12,13,14. Wark et al.13 reported that a single-atom V1/ZSM-5 catalyst had significant SCR activity, implying the mononuclear active sites, but its activity is much lower than that over V2O5/TiO2 with abundant dinuclear sites, in line with the results that dinuclear sites are superior to mononuclear sites8,15,16. Although the existence of the dinuclear sites above is either experimentally speculative or theoretically predicted, dinuclear ACSs appear to be necessary for high SCR activity. Likewise, a dynamically formed transient Cu dimer showed higher SCR rates than one Cu monomer14, indicating the requirement of dinuclear ACSs in SCR. An ideal strategy is to fabricate dinuclear metal sites on supports17, which allows them to function as dual sites catalyzing SCR reaction, but it is a formidable task to synthesize such a catalyst.

Here, we develop a single-atom Mo1/Fe2O3 catalyst, and thus the isolated acidic Mo ions and one adjacent surface redox Fe ions are assembled as uniform dinuclear acid-redox sites, which shows high SCR turnover frequencies (TOFs) comparable to V2O5/TiO2. To tune acid-redox properties of dinuclear sites, we develop W1/Fe2O3 and Fe1/WO3, and find that SCR activity can be controlled by tuning acid or/and redox properties of dinuclear sites, thus implying a common dinuclear feature of highly active catalytic sites.

Results

Fabrication of the single-atom Mo1/Fe2O3 catalyst

We prepared hexagon-shaped α-Fe2O3 nanosheets mainly exposing {001} facets18, as confirmed by synchrotron X-ray diffraction (SXRD, Supplementary Fig. 1) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Supplementary Fig. 2) techniques. On the Fe2O3(001) surface, there are plenty of threefold hollow sites formed by three surface lattice oxygen atoms (Supplementary Fig. 2), which serve as suitable sites for anchoring Mo5+/6+ or W5+/6+ with an ionic radius of ∼0.6 Å19. We successfully anchored single Mo ions on the Fe2O3(001) surfaces to get a single-atom Mo1/Fe2O3 catalyst (Fig. 1). The highly dispersed Mo ions are evidenced by the energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mappings of Mo1/Fe2O3 (Fig. 1c–f) and the SXRD patterns of Mo1/Fe2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 1). In Fig. 1g, the aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (AC-STEM) image of Mo1/Fe2O3 shows that the Mo ions are atomically dispersed on the α-Fe2O3(001) surface. As further analyzed by the selected-area intensity surface plot and the corresponding structural model (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 3), the Mo ions are precisely anchored on the threefold hollow sites (the yellow circles in Fig. 1g, h). Hence, each isolated Mo ion and one adjacent outermost surface Fe ion (denoted as Fesurf in Fig. 1h) with a distance of ∼2.9 Å in between are assembled as one dinuclear site (the red ellipse in Fig. 1g).

a TEM image of Mo1/Fe2O3. b AC-STEM, and c–f EDX mapping images of the selected area (black dashed rectangle) in a. g AC-STEM image of Mo1/Fe2O3. h Intensity surface plot and the corresponding structural model of the selected area (white dashed rectangle) in g. The Mo loading is 1.3 wt% with respect to α-Fe2O3. The purple, red, yellow, and brown balls represent Mo atoms, O atoms, surface Fe atoms (Fesurf), and subsurface Fe atoms (Fesub), respectively. Selected single Mo atoms and dinuclear Mo1-Fe1 sites are marked by the yellow circles and the red ellipses, respectively.

Structures of the dinuclear site

Figure 2a shows the χ(R) k2-weighted Fourier-transform extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) spectra of Mo1/Fe2O3 and α-MoO3 at the Mo K-edge and α-Fe2O3 at the Fe K-edge (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5), and the related structure parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The FT-EXAFS spectrum of Mo1/Fe2O3 is similar to that of α-Fe2O3, implying that the Mo ion is located at a surface site corresponding to the Fe site in α-Fe2O3 bulk, but distinctly different from that of α-MoO3, ruling out the existence of α-MoO3 on Mo1/Fe2O3 surfaces. The second peak is contributed from the scattering path between the Mo atom and the neighboring Fe atoms. An average distance between Mo and Fe is ∼2.93 Å with a coordination number (CN) of 3 (Supplementary Table 1)20, consistent with the observation of the dinuclear Mo1-Fe1 site in Fig. 1g. The first peak can be assigned to the Mo–O bonds with an average bond length of ∼1.88 Å and a CN of 6 (Supplementary Table 1), indicating the existence of a MoO6 motif, i.e., each anchored Mo ion has three surface dangling bonds besides three Mo–O bonds formed with three oxygen ions of the anchoring site. The Mo–O bond length (1.88 Å) is shorter than the Fe-O bonds (1.98 Å) in α-Fe2O3 (Supplementary Table 1), which shows the existence of surface dangling Mo = O bond(s), as evidenced by a double-bond-specific Raman band at ∼989 cm−1 appearing in the Raman spectrum of Mo1/Fe2O321 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

a χ(R) k2-weighted FT-EXAFS spectra of Mo1/Fe2O3 (red line) and α-MoO3 (black line) at the Mo K-edge together with α-Fe2O3 (blue line) at the Fe K-edge. b Mo L3-edge X-ray absorption spectra of Mo1/Fe2O3 (red line), α-MoO3 (black line) and Fe2(MoO4)3 (green line). Blue and red shades represent the unoccupied states of the Mo t2g and eg orbitals, respectively.

In the Mo L3-edge X-ray absorption spectra of α-MoO3 and Fe2(MoO4)3 (Fig. 2b), two peaks of α-MoO3 are readily assigned to the Mo 2p3/2 → 4d(t2g0) and 4d(eg0) transitions, respectively, with a ligand-field splitting energy of ∼3.1 eV for a MoO6 octahedral symmetry (Oh)21, which reduces down to ~1.9 eV for a MoO4 tetrahedral symmetry (Td) in Fe2(MoO4)321. The Mo L3-edge X-ray absorption spectrum of Mo1/Fe2O3 is characteristic of two peaks with a splitting energy of ~3.1 eV (Fig. 2b), similar to that of α-MoO3. These results combined with the above AC-STEM image, the EXAFS data and the Raman evidence manifest the existence of a distorted MoO6 octahedral structure on the Mo1/Fe2O3 surface.

Acid and redox properties of the dinuclear site

The absorption peak of Mo1/Fe2O3 due to the Mo 2p3/2 → t2g transition is weaker than that of α-MoO3 when we normalized the intensity of their peaks due to the Mo 2p3/2 → eg0 transitions (Fig. 2b), implying that the oxidation state of the isolated Mo ion is lower than Mo6+ in α-MoO3. More accurately, owing to the peak areas proportional to the unoccupied states of the orbitals22, we deconvoluted the spectrum of Mo1/Fe2O3 to two individual peaks, and thus the unoccupied states of the t2g and eg orbitals are positively proportional to the areas of the blue shade and the red shade (Fig. 2b), respectively. An area ratio of the two peaks is ~5:4, indicating an electronic configuration (t2g1eg0) of the Mo 4d orbitals of the Mo ions of Mo1/Fe2O3, i.e., the Mo species are Mo5+, in accordance with the data of the Mo 3d X-ray photoelectron spectrum of Mo1/Fe2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 7). For the MoO6 motif, three oxygen atoms are provided by electroneutral α-Fe2O3, and the remaining fragment is negatively charged [MoO3]- due to Mo5+ and O2-. Taking the nearly unchanged oxidation state of Fe after the Mo anchoring into account (Supplementary Fig. 8), the MoO6 motif contains one hydrogen ion (H+) for the charge balance, as evidenced by the diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform (DRIFT) spectra in Supplementary Fig. 9. Thus, each isolated Mo ion due to the formation of a MoO6H species can provide one Brønsted acid site23, which can transform to the Lewis acid site during the SCR reactions24 or in the SCR temperature window (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Apart from the acidic property, the redox ability of ACS is also required for closing a SCR cycle2. To study the redox property of Mo1/Fe2O3, we carried out H2 temperature-programmed reduction procedure (H2-TPR) for three samples (Fig. 3a). α-Fe2O3 has a much stronger reduction ability than α-MoO3. A shoulder peak of α-Fe2O3 at ∼310 °C is readily attributed to the Fe2O3 → Fe3O4 reduction, and a strong peak at ∼380 °C with a discernible shoulder at a high-temperature edge (∼410 °C) can be due to the Fe3O4 → Fe0 reduction25. Subtly, a very weak shoulder appears in a temperature regime 180–320 °C (up-left inset of Fig. 3a), which can be assigned to the reduction of the surface active oxygen of α-Fe2O3 (Supplementary Discussion). The Mo anchoring has little effect on the redox ability of the surface active O atoms of α-Fe2O3 (up-left inset of Fig. 3a), but the reduction temperatures of the bulk O atoms shifted up by ∼20 °C. Moreover, an extra weak peak appears in a high-temperature regime 460–615 °C (up-right inset in Fig. 3a), which can be readily assigned to the reduction of the Mo species (Supplementary Discussion). This result evidences that the redox property of Mo1/Fe2O3 originates from the FeOx species of the dinuclear sites. Since the Mo and Fe ions can provide the acidic and redox properties, respectively, the dinuclear site possesses the common acid-redox properties of ACS of SCR2.

a H2-TPR profiles of Mo1/Fe2O3 (red line) with a 1.3 wt% Mo loading, α-Fe2O3 (blue line) and α-MoO3 (black line). Insets: enlargements of the selected regimes together with the fitting data, and the curves of α-MoO3 and α-Fe2O3 are omitted in the up-left and up-right insets, respectively, for clarity. b SCR rates (black square) at 270 °C and Ea (red circle) on Mo1/Fe2O3 with the different Mo number. The error bars represent standard error.

Identifying the dinuclear characteristic of active sites

To identify active sites of Mo1/Fe2O3, we synthesized a series of Mo1/Fe2O3 with the different number of the Mo ions by tuning the Mo loadings (Supplementary Discussion). NO conversions (XNO) in SCR over these Mo1/Fe2O3 catalysts are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, and XNO increases with the Mo loading, whereas the reducible α-Fe2O3 and the acidic α-MoO3 alone have very low SCR activities under identical reaction conditions. Meanwhile, N2 selectivity of α-Fe2O3 drastically enhances after the Mo loading (Supplementary Fig. 12), and the Mo1/Fe2O3 also shows excellent H2O and/or SO2 durability (Supplementary Fig. 13). This evidences that both the acid site and the redox site are required for excellent SCR performance, consistent with the literature2,3,4. In the reaction kinetics regime (XNO < 15%), we extracted SCR rates at 270 °C from Supplementary Fig. 11, and the apparent activation energy (Ea) from the Arrhenius plot of Supplementary Fig. 14. In Fig. 3b, SCR rates increase linearly with the Mo number, and Ea almost remains constant (86 ± 4 kJ mol−1), evidencing that the active sites of Mo1/Fe2O3 are uniform. Owing to the acid-redox properties and the similar structure as the dinuclear active site of V2O5-based catalysts2,26, and the same catalytic behavior as the dinuclear Cu sites14, the dinuclear Mo1-Fe1 sites are rationally identified as ACSs. Otherwise, XNO decreases (Supplementary Fig. 15) when the structure of the dinuclear sites were destroyed (Supplementary Fig. 16). Furthermore, we calculated TOFs (converted NO molecules per ACS per second) to be ∼1.7 × 10−3 s−1 at 270 °C (Supplementary Fig. 17), comparable to the TOF values (1.3 × 10−3 s−1 at 277 °C27, 2.4 × 10−3 s−1 at 323 °C16) of V2O5/TiO2.

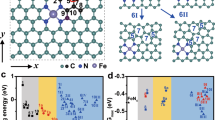

We tuned the acid-redox properties of dinuclear sites, and studied the effect of the properties on SCR activity to substantiate whether the structure feature of dinuclear acid-redox sites can act as a generic structural model of ACSs. To tune the acidic property of the dinuclear site, we anchored the W ions with the weaker acidity than the Mo ions23 on the α-Fe2O3(001) surfaces to get W1/Fe2O3 (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19). As shown in the EDX mapping and AC-STEM images of Fig. 4a–d, the isolated W ions are precisely anchored on the threefold hollow sites to construct dinuclear W1-Fe1 active sites, as marked in red ellipses in Fig. 4d. Likewise, the acidic property (Supplementary Fig. 9) and the redox property (Supplementary Fig. 20) of the dinuclear W1-Fe1 active sites originate from the isolated W ions and the Fe ions, respectively. The trend in catalytic activity of W1/Fe2O3 is similar to that of Mo1/Fe2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 21) and Ea remains constant (Supplementary Fig. 22). In Fig. 4e, the linearly increasing SCR rates over W1/Fe2O3 with the number of ACSs show the behavior expected of the dinuclear catalytic sites14. Catalytic activities of W1/Fe2O3 are slightly lower than Mo1/Fe2O3 (Supplementary Figs. 23 and 24), which indicates that tuning the acidity of the dinuclear site can alter SCR activities.

To tune the redox property, we anchored single Fe ions on (001) surfaces of the square-shaped γ-WO3 nanosheets28 to achieve Fe1/WO3 (Supplementary Discussion), the structures of which were characterized by HRTEM (Supplementary Fig. 25). As the atomic number of W (Z = 74) significantly overnumbers that of Fe (Z = 26) and the very low Fe loadings (Supplementary Discussion), we failed to observe the single Fe atoms on the γ-WO3(001) surfaces by using the AC-STEM imaging and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. The EDX mapping images show the highly dispersed Fe ions on the surfaces (Supplementary Fig. 25). A linear relation between the SCR rate and the number of ACSs (Fig. 4e) and a same trend of catalytic behavior (Supplementary Fig. 26) as that of W1/Fe2O3 or Mo1/Fe2O3 indicate the existence of dinuclear W1-Fe1 sites. The redox property of the dinuclear W1-Fe1 site of Fe1/WO3 is much weaker than that of W1/Fe2O3 (Supplementary Fig. 20), which is one main factor that led to the SCR rates of Fe1/WO3 lower than W1/Fe2O3 (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Figs. 23 and 24). Therefore, to tune the acidic or/and redox properties of the dinuclear sites can alter SCR activities, indicating that the dinuclear acid-redox site can function as a generic structural model of highly active catalytic sites of SCR.

Discussion

The dinuclear structural model could provide a basis for a precise identification of highly active SCR catalytic sites. With an assist of this model to identify dinuclear ACSs, it is not difficult to understand the fact that dimeric vanadium sites show much higher SCR rates than monomeric sites for V2O5-based SCR catalysts5,8, and that a parabola-type curve of TOFs appears as the vanadium coverage increases29. This model also give a satisfactory explanation for the promotional effect of WO3 or MoO3 for V2O5/TiO2 mainly because of the emerging dinuclear W-V or Mo-V catalytic sites more active than the dinuclear V-V sites due to the strong acidity properties of W or Mo ions6,15,23. This model underpins our fundamental understanding why SCR reactions preferentially occur at interfaces of acid-redox oxide catalysts such as Mo-Fe30, W-Fe31, W-Ce32 oxides and so on, leading to their high SCR rates. We anticipate that after optimizing the acid-redox properties of dinuclear sites, improved SCR catalysts with abundant dinuclear acid-redox sites will be developed for more efficiently controlling NO emission.

Methods

Sample synthesis

All the chemicals are of analytical grade and used as received.

Single-atom Mo1/Fe2O3 catalysts

We firstly prepared the α-Fe2O3 hexagonal nanosheets according to the reference18. FeCl3·6H2O (0.54 g, 2.0 mmol) was dissolved in ethanol (30.0 mL) with a trace addition of de-ionized water (1.5 mL) under vigorously magnetic stirring until completely dissolved, to which sodium acetate (1.91 g, 23.3 mmol) was added under stirring. The mixture was sealed in a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave (50 mL) and maintained in the oven at 180 °C for 24 h. After natural cooling to room temperature, the resulting solid was washed with de-ionized water and ethanol several times, respectively, dried at 60 °C for 4 h. The single-atom Mo1/Fe2O3 catalysts were prepared by the impregnation method. The certain amount of (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O was solved in de-ionized water to form an aqueous solution, to which the α-Fe2O3 powder (2.00 g) was added under vigorously magnetic stirring at 80 °C until the water was evaporated. Then all the samples were dried at 80 °C for 12 h and calcined at 550 °C in air for 3 h. The Mo amount was adjusted according to the number of the anchoring sites of the α-Fe2O3 surfaces (see the Section 2 of Supplementary Discussion for more details) to get a series of the samples with the different Mo loadings, and the obtained samples were measured to be 1.3, 1.0, 0.76, and 0.46 wt% by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectra. An overloaded sample with a Mo 3.3 wt% loading (denoted as 3.3% Mo/Fe2O3, see Supplementary Discussion for more details) was also synthesized with the same procedure for comparison.

Single-atom W1/Fe2O3 and Fe1/WO3 catalysts

W1/Fe2O3 and Fe1/WO3 were prepared by the same procedure of that of Mo1/Fe2O3 except that the (NH4)6H2W12O40·xH2O (MW: 2956.30) and Fe(NO3)3·9H2O precursors, and a γ-WO3 nanoplate support were used, and Fe1/WO3 was calcined at 400 °C in air for 4 h. The W loadings of W1/Fe2O3 were set to be 2.0, 1.5, 1.0, and 0.53 wt% with respect to α-Fe2O3. The Fe loadings of Fe1/WO3 were set to be 0.28, 0.21, 0.17, 0.07 wt% with respect γ-WO3. Before the preparation of Fe1/WO3, the γ-WO3 nanoplate support was prepared according to the previous report28. Briefly, Na2WO4·2H2O (1.65 g, 5 mmol) was dissolved in 30 mL de-ionized water, to which an aqueous HCl solution (5 mL, 36–38 wt%) was added under magnetic stirring at room temperature. A H2C2O4 (0.45 g, 5 mmol) was introduced into the solution under stirring for 1 h. The resulting dark-yellow precursor solution was transferred into a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless autoclave, sealed and heated in the oven at 120 °C for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, the precipitate was collected via centrifugation and further washed with de-ionized water and ethanol, and dried in air at 80 °C. Finally, the obtained powder was calcined at 400 °C for 4 h. Unless mentioned otherwise, the following Mo1/Fe2O3, W1/Fe2O3, and Fe1/WO3 refer to 1.3 wt% Mo/Fe2O3, 2.0 wt% W/Fe2O3, and 0.28 wt% Fe/WO3, respectively.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images

TEM and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images were carried out with a JEOL JEM-2100F field-emission gun transmission electron microscope operating at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV and equipped with an ultra-high-resolution pole-piece that provides a point-resolution better than 0.19 nm. Fine powders of the materials were dispersed in ethanol, sonified, and sprayed on a carbon coated copper grid, and then allowed to air-dry.

Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark filed scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-STEM) images and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) elemental mapping were performed at 200 kV with a JEOL ARM-200F FEG TEM equipped with a probe corrector, a high-angle annular dark-field detector, and EDX detector. Fine powders of the materials were dispersed in ethanol, sonified, and sprayed on a Si3N4 grid with a size of 8 nm in thickness, and then allowed to air-dry.

Synchrotron X-ray diffraction (SXRD) patterns

The X-ray diffraction data were obtained at beamline BL14B1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) using X-ray with a wavelength of 0.6884 Å. The sample is loaded into a spinning capillary for measurements. Mythen 1 K Si strip linear detector is used for data acquisition. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of some samples were also collected with a Rigaku Ultima-IV diffractometer (Japan) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å).

X-ray absorption spectra (XAS)

XAS covers the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra, which were measured at Mo K-edge and Fe K-edge at BL14W of the SSRF with an electron beam energy of 3.5 GeV and a ring current of 200–300 mA. Data were collected with a fixed exit monochromator using two flat Si(311) crystals for the Mo K-edge XAS measurements or two flat Si(111) crystals for the Fe K-edge XAS measurements. Harmonics were rejected by using a grazing incidence mirror. The XANES spectra were acquired at an energy step of 0.5 eV. The EXAFS spectra were collected in a transmission mode using ion chambers filled with N2. The raw data was analyzed using the IFEFFIT 1.2.11 software package. The soft-X-ray absorption spectra at the Mo L3-edge were measured at 4B7A of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility with an electron beam energy of 2.21 GeV and a ring current of 300–450 mA.

X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS)

XPS were collected on an ESCALAB 250 multifunctional X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy instrument (Thermo Fisher) using a monochromatic Al-Ka X-ray source (hυ = 1486.6 eV). The spectrometer was equipped with a delay-line detector. Spectra were acquired at normal emission with a passing energy of 40 eV. Spectra were all referenced to the C 1s peak at a binding energy of 284.6 eV for each new scan. Data analysis and processing was undertaken using XPSPeak4.1 with Shirley type background.

Temperature-programmed reduction by hydrogen (H2-TPR) profiles

H2–TPR was conducted by using an AutoChem II 2950HP auto-adsorption apparatus. The areas of the reduction peaks have been calibrated by the H2 uptakes of the different amounts of CuO. Prior to the reduction process, ∼20 mg samples were treated under a N2 atmosphere with a flow rate of 30 mL min−1 at 300 °C for 30 min, and then cooled to room temperature under N2 atmosphere. For each run, the sample was reduced in stream of 10.0 vol% H2/Ar (80 mL min−1) at a ramp of 2.5 °C min−1.

Raman spectroscopy

The static Raman measurements of the molecular structures of catalysts were determined on a XploRA confocal spectrometer (Jobin Yvon, Horiba Gr, France). The Raman scattering was excited by an external-cavity diode (785 nm) and coupled with a 50 × Olympus microscope objective (Olympus, 0.50 Numerical Aperture). The power of the laser was equal to 9 mW. A 1200 lines per mm diffraction grating places prior to a multichannel charge-coupled device device (1024 × 256 pixels) was used to collect spectra in a resolution of 3 cm−1 with two accumulations at a 10 s acquisition time.

In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform (DRIFT) spectra

In situ DRIFT spectra were conducted by accumulating 64 scans at a 4 cm−1 resolution in the kubelka-Munk format from 4000 to 1000 cm−1 on an FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet iS 50) equipped with a Harrick Scientific DRIFT cell and a mercury-cadmium-telluride MCT/A detector. Prior to each experiment, the catalysts were pretreated at 300 °C in a flow of N2 (30 mL min–1) for 0.5 h to remove physically adsorbed water and then cooled to the target temperature under N2 flow to obtain a background spectra which should be deducted from the spectra of samples. After obtaining the background spectra at different temperatures, the catalysts were exposed to a flow of 500 ppm NH3 at 30 °C for 1 h. The desorption process then went on under a flow of N2 (30 mL min–1) and was recorded at the corresponding temperature of background spectrum.

Catalytic evaluations

SCR activity measurements were performed in a fixed-bed quartz reactor (inner diameter 4 mm) under atmospheric pressure. The feed gas contained 500 ppm NO, 500 ppm NH3, 3.0 vol% O2, and balanced N2. The total flow rate was 1000 mL min−1 and 0.1 g sample (40–60 mesh) was used (0.2 g Fe1/WO3 was used to keep the same space velocity as the other samples). The gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) was calculated to be 800,000 h−1. Data were recorded by a temperature-programmed procedure at a ramp of 2.5 °C min−1. H2O and SO2 durability measurements were performed in a fixed-bed quartz reactor (inner diameter 8 mm) under atmospheric pressure at 300 °C. The feed gas contained 500 ppm NO, 500 ppm NH3, 3.0 vol% O2, 200 ppm SO2 (when used), 5.0 vol% H2O (when used) and balanced N2. The total flow rate was 500 mL min−1 and 0.6 g sample (40–60 mesh) was used. The concentration of NO in the outlet was continually monitored by an online chemiluminescence NO−NO2−NOx analyzer (42i-HL, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). N2 selectivity (SN2) in the SCR process was measured by a Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer (Thermo Scientific Antaris IGS analyzer), and SN2 was calculated by a following formula 1:

where [A]in and [A]out represent the concentration of A in inlet gas and outlet gas, respectively.

Data availability

The additional data are provided in the Supplementary Information. All the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Busca, G., Lietti, L., Ramis, G. & Berti, F. Chemical and mechanistic aspects of the selective catalytic reduction of NOx by ammonia over oxide catalysts: a review. Appl. Catal. B 18, 1–36 (1998).

Topsøe, N. Y. Mechanism of the selective catalytic reduction of nitric oxide by ammonia elucidated by in situ on-line fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Science 265, 1217–1219 (1994).

Marberger, A., Ferri, D., Elsener, M. & Kröcher, O. The significance of lewis acid sites for the selective catalytic reduction of nitric oxide on vanadium-based catalysts. Angew. Chem. Inter. Ed. 55, 11989–11994 (2016).

Zhu, M., Lai, J.-K., Tumuluri, U., Wu, Z. & Wachs, I. E. Nature of active sites and surface intermediates during SCR of NO with NH3 by supported V2O5–WO3/TiO2 catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 15624–15627 (2017).

He, G. et al. Polymeric vanadyl species determine the low-temperature activity of V-based catalysts for the SCR of NOx with NH3. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau4637 (2018).

Jaegers, N. R. et al. Mechanism by which tungsten oxide promotes the activity of supported V2O5/TiO2 catalysts for NOx abatement: structural effects revealed by 51V MAS NMR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Inter. Ed. 58, 12609–12616 (2019).

Ramis, G., Busca, G., Bregani, F. & Forzatti, P. Fourier transform-infrared study of the adsorption and coadsorption of nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide and ammonia on vanadia-titania and mechanism of selective catalytic reduction. Appl. Catal. 64, 259–278 (1990).

Went, G. T., Leu, L. -J., Rosin, R. R. & Bell, A. T. The effects of structure on the catalytic activity and selectivity of V2O5/TiO2 for the reduction of NO by NH3. J. Catal. 134, 492–505 (1992).

Topsøe, N. Y., Topsøe, H. & Dumesic, J. A. Vanadia/titania catalysts for selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of nitric-oxide by ammonia: I. combined temperature-programmed in-situ FTIR and on-line mass-spectroscopy studies. J. Catal. 151, 226–240 (1995).

Topsøe, N. Y., Dumesic, J. A. & Topsøe, H. Vanadia-titania catalysts for selective catalytic reduction of nitric-oxide by ammonia: II. studies of active sites and formulation of catalytic cycles. J. Catal. 151, 241–252 (1995).

Went, G. T., Leu, L.-J & Bell, A. T. Quantitative structural analysis of dispersed vanadia species in TiO2(anatase)-supported V2O5. J. Catal. 134, 479–491 (1992).

Thomas, J. M., Raja, R. & Lewis, D. W. Single-site heterogeneous catalysts. Angew. Chem. Inter. Ed. 44, 6456–6482 (2005).

Wark, M., Brückner, A., Liese, T. & Grünert, W. Selective catalytic reduction of NO by NH3 over vanadium-containing zeolites. J. Catal. 175, 48–61 (1998).

Paolucci, C., Khurana, I., Parekh, A. A., Li, S. & Gounder, R. Dynamic multinuclear sites formed by mobilized copper ions in NOx selective catalytic reduction. Science 357, 898–903 (2017).

Wachs, I. E. et al. Selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 over supported vanadia catalysts. J. Catal. 161, 211–221 (1996).

Lietti, L. & Forzatti, P. Temperature programmed desorption/reaction of ammonia over V2O5/TiO2 de-NOxing catalysts. J. Catal. 147, 241–249 (1994).

Ro, I., Xu, M., Graham, G. W., Pan, X. & Christopher, P. Synthesis of heteroatom Rh–ReOx atomically dispersed species on Al2O3 and their tunable catalytic reactivity in ethylene hydroformylation. ACS Catal. 9, 10899–10912 (2019).

Chen, L. et al. Continuous shape- and spectroscopy-tuning of hematite nanocrystals. Inorg. Chem. 49, 8411–8420 (2010).

Shannon, R. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. 32, 751–767 (1976).

Corrias, A., Ennas, G., Mountjoy, G. & Paschina, G. An X-ray absorption spectroscopy study of the Fe K edge in nanosized maghemite and in Fe2O3–SiO2 nanocomposites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2, 1045–1050 (2000).

Radhakrishnan, R. et al. Variability in the structure of supported MoO3 catalysts: studies using raman and X-ray absorption spectroscopy with ab initio calculations. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 8519–8530 (2001).

Choy, J. H., Kim, D. K., Demazeau, G. & Jung, D. Y. L III-edge XANES study on unusually high valent iridium in a perovskite lattice. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 6258–6262 (1994).

Jeong, N. C., Lee, J. S., Tae, E. L., Lee, Y. J. & Yoon, K. B. Acidity scale for metal oxides and Sanderson's electronegativities of lanthanide elements. Angew. Chem. Inter. Ed. 47, 10128–10132 (2008).

Song, I., Lee, H., Jeon, S. W. & Kim, D. H. Understanding the dynamic behavior of acid sites on TiO2-supported vanadia catalysts via operando DRIFTS under SCR-relevant conditions. J. Catal. 382, 269–279 (2020).

Liu, F., Shan, W., Lian, Z., Liu, J. & He, H. The smart surface modification of Fe2O3 by WOx for significantly promoting the selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3. Appl. Catal. B 230, 165–176 (2018).

Silversmit, G. et al. The structure of a VOx/TiO2 (anatase) powder catalyst under reduction and oxidation at 623K. Phys. Scr. T115, 798–801 (2005).

Lietti, L. et al. Characterization and reactivity of V2O5–MoO3/TiO2 de-NOx SCR catalysts. J. Catal. 187, 419–435 (1999).

Zhang, Q. et al. Isolated platinum atoms stabilized by amorphous tungstenic acid: metal–support interaction for synergistic oxygen activation. Angew. Chem. Inter. Ed. 57, 9351–9356 (2018).

Marshneva, V. I. et al. The influence of support on the activity of monolayer vanadia-titania catalysts for selective catalytic reduction of NO with ammonia. J. Catal. 155, 171–183 (1995).

Xin, Y. et al. Active site identification and modification of electronic states by atomic-scale doping to enhance oxide catalyst innovation. ACS Catal. 8, 1399–1404 (2018).

Liu, Z., Su, H., Chen, B., Li, J. & Woo, S. I. Activity enhancement of WO3 modified Fe2O3 catalyst for the selective catalytic reduction of NOx by NH3. Chem. Eng. J. 299, 255–262 (2016).

Chen, J. et al. Enhanced performance of ceria-based NOx reduction catalysts by optimal support effect. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 473–478 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Prof. Liwu Zhang for the help in the Raman spectroscopy measurement. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21777030 and 21976037), the National Engineering Laboratory for Flue Gas Pollution Control Technology and Equipment (NEL-KF-201903), and the National Engineering Laboratory for Mobile Source Emission Control Technology (NELMS2018B02). The SXRD and X-ray absorption spectra were carried out at Shanghai and Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. and X.T. designed and led the experiments. W.Q. and X.L. prepared the catalysts, conducted the experiments, and analyzed the data. J.C. and Y.D. assisted in catalysts preparation and activity measurements. W.Q., X.T., and Y.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, W., Liu, X., Chen, J. et al. Single-atom catalysts reveal the dinuclear characteristic of active sites in NO selective reduction with NH3. Nat Commun 11, 1532 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15261-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15261-5

This article is cited by

-

Antibacterial Properties of Rod-Like Vanadium Oxide Nanostructures via Ganoderma lucidum Plant Extract Approach

Chemistry Africa (2024)

-

Atomically dispersed materials: Ideal catalysts in atomic era

Nano Research (2024)

-

Complex phase transitions and phase engineering in the aqueous solution of an isopolyoxometalate cluster

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Defect engineering for advanced electrocatalytic conversion of nitrogen-containing molecules

Science China Chemistry (2023)

-

Effects of exposed crystal facet on SO2 resistance of α-Fe2O3 for selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.