Abstract

Animal alarm calls can contain detailed information about a predator’s threat, and heterospecific eavesdropping on these signals creates vast communication networks. While eavesdropping is common, this indirect public information is often less reliable than direct predator observations. Red-breasted nuthatches (Sitta canadensis) eavesdrop on chickadee mobbing calls and vary their behaviour depending on the threat encoded in those calls. Whether nuthatches propagate this indirect information in their own calls remains unknown. Here we test whether nuthatches propagate direct (high and low threat raptor vocalizations) or indirect (high and low threat chickadee mobbing calls) information about predators differently. When receiving direct information, nuthatches vary their mobbing calls to reflect the predator’s threat. However, when nuthatches obtain indirect information, they produce calls with intermediate acoustic features, suggesting a more generic alarm signal. This suggests nuthatches are sensitive to the source and reliability of information and selectively propagate information in their own mobbing calls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Predators are a major source of mortality for many species, and animals often use alarm calls to warn each other about danger1,2,3. Mobbing calls are a type of alarm call typically produced in response to predators that do not pose an immediate threat and function to recruit other individuals to drive these predators away from the area, making a future surprise attack less likely4,5,6,7. Variations in the acoustic structure of mobbing vocalizations can transmit detailed information about the predator1,4,5,8,9, including the type, size, distance, behaviour, category, and threat level of the predator1,6,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. These calls are not only used by conspecifics, but are also eavesdropped on by heterospecifics as well20,21,22,23,24,25. Obtaining information about predators from these calls improves receivers’ chances of survival26,27 and their ability to respond appropriately to different types of predatory threats18,28, and can also allow naïve individuals to learn about new predator species and the threats they pose29,30,31,32,33. Inappropriate responses to a predator threat can be costly either by overestimating the degree of threat leading to wasted time and energy that could be used for other important behaviours (e.g. foraging or searching for mates), or by underestimating the degree of threat leading to injury or death from the predator34,35,36. Thus, natural selection should favour alarm calling systems in which signals reliably reflect the threat level a potential predator poses and receivers assess the quality of the source of the information and base their responses on this information quality.

Although mobbing calls can encode detailed information about the danger posed by a given predator5,16,24,37,38, the information that receivers extract from these calls may not provide the same degree of information that could be obtained through a direct encounter with the predator. This degree of reliability determines how useful indirect information is to an eavesdropper20,39,40. As individuals can vary their calls in response to the community or group composition41,42,43, information obtained indirectly from alarm calls of others (i.e. public or indirect information) could sometimes provide an inaccurate representation of the threat44,45,46,47. A number of factors, for example life history features of a given species43,48,49,50,51,52,53,54, or predator detection55 could affect how individuals assess or respond to different threats; because the information included in these calls are thought to be a representation of the caller’s perceived threat, not the threat itself45, the reliability or accuracy of these calls to heterospecifics (and sometimes conspecifics) is potentially limited45,53,56. Although studies of alarm calls have provide a rich window on animal perception and behaviour, we still have important and outstanding questions about whether and how animals encode threat levels about predators depending on the source of the information—direct, personal information (e.g. hearing a predator calling) versus indirect, public information (e.g. hearing other species giving alarm calls)44,45,46,54,56.

Here we experimentally test how eavesdroppers in a mixed-species bird community propagate information about predator threat in their alarm calls in response to direct, personal information versus indirect, public information. We study wild red-breasted nuthatches (Sitta canadensis), a species that frequently joins nuclear flocks of black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) during the winter. Chickadees are sensitive to the threat levels of different species of avian predators, and are known to vary their alarm calls when they encounter different size raptors4 or overhear raptor calls38. Nuthatches are known to eavesdrop on their mobbing calls and respond appropriately to the information encoded therein24,57, but little is known about whether or how nuthatches encode information about predator threat level in their own mobbing vocalizations.

Here we test the prediction that in response to direct information, nuthatches should produce finely-nuanced alarm calls that accurately reflect the level of threat of the predator; in contrast, in response to less reliable indirect public information, nuthatches should produce alarm calls that reflect the ambiguity in the source of information. In our study, we expose nuthatches to direct information indicating the presence of predators of varying threat levels (playbacks of high and low threat predator calls) and indirect information (chickadee mobbing calls in response to the same predators; Fig. 1). Nuthatches change acoustic features of their mobbing calls in response to increased levels of threat depending on the source of the information. They respond the least to low-threat predator calls, the most to high-threat predator calls, and intermediately to chickadee calls. They do not differentiate between indirect high- and low-threat calls. This suggests that (1) nuthatches only propagate reliable direct information but respond intermediately to less-reliable indirect information to avoid costs of miss-quantifying the degree of predator threat and (2) graded information in nuthatch calls is not a direct reflection of internal state.

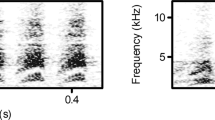

Nuthatches were exposed to playback of acoustic signals indicating a nearby predator of low or high threat. In the direct information treatment, we broadcast the vocalizations of a great-horned owls (low threat), and b northern pygmy-owls (high threat). In the indirect information treatment, we broadcast black-capped chickadee mobbing calls produced in response to c great horned owls, and d northern pygmy-owls.

Results

Acoustic features

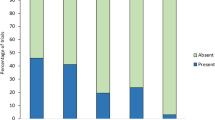

Nuthatches changed the acoustic features of their mobbing calls in response to different levels of threat based on the source of the information—direct or indirect—about predator threat. In response to calls of the high-threat northern pygmy-owl, nuthatches produced mobbing calls that had higher call rates, higher peak frequencies, and shorter call lengths compared to low-threat great-horned owls. In response to indirect public information about predators (mobbing calls of chickadees produced in response to these same owls), nuthatches produced mobbing calls with call rate, peak frequency, and call length parameters that were similar to both high- and low-threat chickadee calls, and intermediate compared with the low- and high-threat calls produced in response to direct information (Linear Mixed Model: call rate interaction: χ2 = 6.43, P = 0.011, peak frequency interaction: χ2 = 12.78, P < 0.001, call length interaction: χ2 = 5.57, P = 0.018; control: 38 sites, 632 calls, low-direct 19 sites, 1204 calls, high-direct: 21 sites, 5272 calls, low-indirect: 29 sites, 3172 calls, high-indirect 35 sites, 5205 calls; Figs. 2, 3; Supplementary Movie 1; Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Data 1). There were no order:exemplar effects (Linear Mixed Model: call rate: χ2 = 4.12, P = 0.846; peak frequency: χ2 = 3.30, P = 0.914; call length: χ2 = 10.42, P = 0.237; Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Data 1).

Acoustic parameters of nuthatch mobbing calls depend both on the threat level of the predator and the source of the information. Mean ± standard error of red-breasted nuthatch a call rate (calls/bird/minute), b peak frequency (kHz), and c call length (s) of mobbing calls produced in response to control (grey triangles), direct information (blue circles), and indirect information (orange squares). Source data are provided as Supplementary Data 1.

Discussion

We found that red-breasted nuthatches produce mobbing calls in response to both direct and indirect information, but how they vary acoustic structures of these calls to transmit information about predator threat depends on the source of the information. In response to direct information (hearing predators), nuthatches produced very different alarm signals to each threat: hearing vocalizations of the very dangerous northern-pygmy owl elicited rapid, shorter, and higher pitched mobbing calls than calls elicited from hearing vocalizations of the less dangerous great-horned owl. This is similar to other species that vary call rate, peak frequency, and call length in response to varying levels of predator threat1,4,5,16. Interestingly, the vocal behaviour of nuthatches hearing alarm calls of chickadees (indirect, public information) was quite different: despite clearly varying their investigatory and approach behaviour when eavesdropping on chickadee alarm calls representing different levels of threat24, nuthatches did not in turn encode this information in their own vocalizations. These results indicate that nuthatches discriminate between direct and indirect, or public information, and this is reflected in the acoustic structure of their alarm calls.

Many animals use public information in uncertain or dangerous situations, including predator assessment and vigilance54,58,59,60,61,62,63,64. Templeton and Greene24 showed that nuthatches obtain information about predator threat from chickadee mobbing calls; public information received from heterospecific mobbing calls could provide a relatively safe method for nuthatches to collect information about predators in their environment20,54,65. Nuthatches are potentially more vulnerable to predation than the species on which they are known to eavesdrop because of their restricted visibility associated with their foraging ecology (typically on or near tree trunks66) and tendency to spend more of the winter months in breeding pairs rather than larger groups67. These ecological factors, combined with previous research, suggests that nuthatches should use social information to learn about predators24,54,57,68,69,70. While nuthatches clearly do use indirect, public information to make behavioural decisions about mobbing, we found that they do not propagate this information in their own vocalizations. We suggest that the variation in vocal signalling behaviour in response to direct or indirect information could be due to differences in the reliability of these sources.

Public information is important for many reasons but is also generally not as reliable as personal/direct information20,44,45,46,54,56,58,65,69,71,72. Individuals—including the sender and receiver—can differ in their life history features, which can, in turn, affect their responses20,51,52,53,54,70,73,74. For example, Eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus) not only respond to alarm calls with increased vigilance depending on their own boldness score (shyer individuals respond more), but also in response to the boldness score of the signaller (bolder individuals elicit increased vigilance)51. New Holland honeyeaters (Phylidonyris novaehollandiae) are slower to respond to aerial predators, and more likely to flee in response to an alarm call when foraging on flowers than when perched52. When dealing with heterospecific alarm calls, these variables are further confounded by the fact that different species may also perceive the same predator as different threat levels5. For example, bird species that are more prevalent in the diet of a Eurasian pygmy-owl (Glaucidum passerinum) are more likely to mob that predator74. Additionally, heterospecifics, even allopatric species from the same family5, may use different ways to encode predator threat information in their alarm calls55; and while some species can learn to recognize heterospecific calls either by associating a new call with their own alarm calls or by associating a new call with the presence of a predator, as superb fairy-wrens (Malurus cyaneus) do32,33, not all species may be able to learn these associations.

The type of public information obtained can also greatly affect the reliability of the information45. Obtaining information by directly observing the state of an individual or the resources it is exploiting (i.e. how often an individual obtains food from a patch) is often highly reliable, but information obtained from the behavioural decisions of others (i.e. which patch an individual chooses) can be much less reliable45. Western Australian magpies (Cractucus tibicen dorsalis) for example, take a signaller’s history of reliability (i.e. whether they previously signalled when a predator was present or absent) when making decisions about how to respond to an individual’s alarm call47 as individuals may differ in their reliability and therefore the threat signalled by the call. Chickadee calls reliably encode information about predator threat44. Nuthatches and chickadees share many predators, suggesting that they should also assess predator species similarly. However, while chickadee call types (i.e. mobbing vs. aerial alarm), like those of many species, reliably encode differences in type of threat and elicit correct search behaviour for different types of predators (i.e. looking up in response to aerial predator calls, and down in response to ‘terrestrial’ predator calls16), chickadee calls are likely not correlated directly with the threat itself but rather a measure of a particular chickadee’s perceived threat level. It is likely that features other than predator species could impact a chickadee’s overall threat assessment, including the predator’s behaviour or distance, the presence of other conspecifics, or the calling individual’s age, sex, experience, personality type, general stress level, internal state, or distance from protective cover23,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,55,74,75,76,77,78. Thus, individuals should be strategic in how they use different types of information44,45,71,72,73. As many species, including nuthatches, that are known to eavesdrop on mobbing calls have long-term pair bonds or kin nearby, it might be in an eavesdropper’s best interest to produce reliable and accurate information to avoid eliciting inappropriate responses that could have negative fitness consequences for the receiver(s).

Due to the potential unreliability of public information obtained from eavesdropping on heterospecific alarm calls, nuthatches may avoid further propagating this information to their mate until they have assessed the situation and obtained more reliable, direct information themselves. Propagating incorrect information could cause a receiver to increase its risk of predation by under- or overestimating a threat. If a receiver underestimates a threat, it might be less vigilant, increasing its chance of predation. On the other hand, if a receiver overestimates a threat, it may increase conspicuous behaviour, like mobbing, which necessarily trades off with foraging and could even increase the likelihood of being depredated by other, unknown predators79. While nuthatches clearly use indirect public information to make behavioural decisions about predators, we found that the resulting alarm calls they produce reflect the uncertainty inherent in this less reliable source of information. Future research should use playback experiments to confirm that other nuthatches can decode information about predator threats and reliability from these acoustic variations in the nuthatch mobbing calls, and if they treat the indirect information in these calls similarly to the information in chickadee calls.

The finding that the mobbing vocalizations of nuthatches are not always directly correlated with their behavioural response adds an interesting piece of data to the debate about what type of information is reflected in variations of graded signals, i.e. where a given call type varies (e.g. number of repeated elements, peak frequency, etc.) across a gradient. Information coded in graded vocalizations, such as nuthatch and chickadee mobbing vocalizations, is often thought to be simply a reflection of the behavioural state of arousal of the calling bird1, or level of risk15. Our findings, in conjunction with those of Templeton and Greene24 and Billings et al.55, suggest that this may not always be the case. Templeton and Greene24 showed that nuthatches varied their anti-predator behaviour when they heard chickadee mobbing calls signifying different threat levels—implying heightened stress/arousal levels—while the current study demonstrates that these nuthatch behaviours do not necessarily translate to variation in their own vocalizations. Billings et al.55 found that while Steller’s jays do not change their foraging behaviour differently in response to visual compared to acoustic cues of predator presence, they did change graded aspects of their mobbing calls (i.e. duty cycle, number of elements)55. This suggests that while some mobbing calls use a graded acoustic structure, these gradations are not simply a reflection of an animal’s internal state of arousal and could instead reflect more nuanced assessments of the information available in regard to predator encounters.

Methods

Subjects

Red-breasted nuthatches tend to stay on year-round territories, but readily join mixed-species flocks with chickadees and other species67. Chickadees are gregarious, highly vocal, and readily mob predators1,4,66.

Stimuli

To test if nuthatches encode information about predator threat in their alarm calls, we presented them with acoustic playbacks of predators that varied in threat level: low-threat (great horned owl, Bubo virginianus) and high-threat (Northern pygmy-owl, Glaudicium gnoma; Fig. 3). Small raptors, like the pygmy-owl, are more manoeuvrable and can accelerate faster than large raptors, and therefore pose a greater threat to small birds like nuthatches80. To test how nuthatches use different information sources, we also varied the type of information source: direct (calls produced by great-horned owls and northern pygmy-owls) and indirect (black-capped chickadee mobbing calls elicited in response to great-horned owls or northern-pygmy owls4; Fig. 1). We used vocalizations from two sympatric species commonly encountered in the winter—house sparrow (Passer domesticus) or Townsend’s solitaire (Myadestes townsendi)—as control stimuli. The predator and control calls were obtained from the Macaulay Library of Cornell Lab of Ornithology (files: 87905, 50193, 119411, 59827(p), 50548, 22874b, 25635a, 11117a, 140258). To reduce pseudoreplication, we had a library of three different examples for each stimulus. Low threat chickadee calls had a call rate of 21.75 ± 3.63 calls/min, and 3.45 ± 0.34 D elements/call and high threat chickadee calls had a call rate of 27.25 ± 2.23 calls/min, and 7.30 ± 1.75 D elements/call.

Playback trials

We conducted auditory playback to pairs of nuthatches at 60 locations in and around Missoula, Montana (46°, 50′ N; 114°, 02′ W), during the winters of 2005 (ref. 24), and 2012, 2013, and 2015, and in three locations in and around Mazama, Washington (48°, 35′ N; 120°, 24′ W), during the winter of 2016. We used a repeated measures experimental design where individuals at each location were presented with each of the five playback stimuli (with the exception of the 2007 data used from ref. 24, in which birds only received chickadee call and control playbacks). While we could not be sure of individual identity for all trials as individuals were not colour ringed, nuthatches remain territorial in the winter67, study sites were at least 500 m apart, and the majority of the sites were not reused across study years. During each playback trial, we located nuthatches that were not in a mixed species flock in order to isolate the responses of the nuthatches to the playbacks without the actual presence and behaviour of chickadees or other species influencing their behaviour. We then played back one stimulus for 1 min using a Pignose Legendary 7-100 speaker (frequency response curve is relatively flat between 500 Hz and 17,000 Hz, Pignose, Las Vegas, NV, USA). This equipment produces high-fidelity non-frequency warped playback characteristics in the hearing range of nuthatches81 and is commonly used in playback experiments to birds (e.g. ref. 82). We calibrated the peak amplitude of each playback stimulus to a natural volume of 75 dB SPL (A-weighting) measured 1 m from the speaker, which observers judged by ear to be similar to natural call amplitudes. For each focal group of nuthatches, the order of presentation of the stimuli and the exemplar for each stimulus were randomized.

The acoustic responses of the nuthatches were recorded with a Sennheiser ME 67 shotgun microphone (Sennheiser, Wedemark, Germany) onto a SONY TCM-5000 tape recorder or a Marantz PMD661 digital recorded (48 kHz sampling rate and 24-bit depth). Due to variation in sampling effort, sample sizes varied somewhat across treatments: control (n = 38), low-threat direct information (n = 19), low-threat indirect information (n = 29), high-threat indirect information (n = 35), and high-threat direct information (n = 21).

Ethical note

We simulated the presence of raptors by playing their calls to wild, free-living birds. We limited our experiments to periods between 1 h after sunrise and 1 h before sunset to allow birds to feed after waking up and before the night. Our experiments conformed to the standards outlined in the ASAB/ABS Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Research and were conducted under the University of Montana’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee’s Animal Use Protocols (ACC 022-01, 049-14EGDBS-080814, 001-11EGDBS-080511).

Acoustic analysis

We analysed the nuthatch vocalizations using Raven acoustical software (RavenPro 1.4 & 1.5; Bioacoustics Research Program 2011) with a spectrogram frequency grid resolution of 23.04 Hz, and a Hann window function. Nuthatches varied in their latency to arrive and begin mobbing after the playback, likely due to variation in distance from the speaker or behaviour at the start of the playback trial. Because of this variation, we standardized our measure of mobbing response by focusing the analyses by using the 60 s after the birds arrived and began intensively mobbing. We recorded (1) the number of calls produced, (2) peak frequency: the frequency (kHz) at which the most power occurred, and (3) call length (seconds; Fig. 3). We chose these acoustic features as they are commonly used by other species, including chickadees and other species of Paridae, to encode information about predator threat in graded signals1,4,5. Occasionally nuthatches would respond to live raptors that flew by just before or during the experiments; we excluded these trials from the analyses. Rarely nuthatches responded by approaching the playback speaker without vocalizing themselves; these trials were also excluded.

Statistical analysis

To test how nuthatches varied their calling behaviour in response to different predators and sources of information, we tested for an interaction between predator threat and information source. We have observed that nuthatches vary in the time they take to begin mobbing after playbacks, escalate from silence to a steady mobbing rate, and vary in how long they respond. Because of this variation, we standardized our measure of mobbing response by focusing the analysis on the 60 s with the highest call rate (calls/s) during mobbing response for each trial. We used R (v3.6.1) statistical software83,84 and the lme4 package to perform data analyses. We generated linear mixed models with a Gaussian distribution to test for the interaction between predator threat and information type on red-breasted nuthatch (1) call rate (total calls per minute/number of individuals present), (2) peak frequency (kHz; the frequency at which the most power occurs), and (3) call length (seconds). Our models included the fixed factors of predator threat (three levels: control, low threat/great-horned owl, high threat/northern pygmy-owl), information type (three levels: control, direct, and indirect), the number of nuthatches present, call exemplar, presentation order, and the interaction between call exemplar and presentation order. Year and location were included in the models as random effects in order to limit the effects of pseudoreplicatoin due to multiple individuals and calls being produced at each location. Nuthatches responded similarly to both species of control playback (house sparrow and Townsend’s solitaire), so these were pooled for further data analysis. We included call exemplar to control for playback exemplars, presentation order to control for order effects, and the interaction between exemplar and order to control for specific combinations thereof (i.e. control 1 being first), and number of red-breasted nuthatches to control for differences in number of nuthatches ((mean ± SEM): 2.317 ± 0.11 nuthatches; the majority of the trials had 1–4 nuthatches present, but in 7% of trials there were 6 or 8 individuals present). We observed a potential exemplar–order interaction in the data; however, this was likely due to stochasticity in which exemplars were used during the relatively small sample size of control trials where we recorded vocalizations. To determine if there were significant factors or an interaction between predator threat and information type, we compared models using likelihood-ratio tests (using the drop1 function). All P values we report are two tailed.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data used in this study can be found in Supplementary Data 1.

Code availability

R Code used in this article for analysis can be found in Supplementary Software 1.

References

Gill, S. A. & Bierema, A. M. K. On the meaning of alarm calls: a review of functional reference in avian alarm calling. Ethology 119, 449–461 (2013).

Suzuki, T. N., Wheatcroft, D. J. & Griesser, M. Experimental evidence for compositional syntax in bird calls. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–7 (2016).

Zuberbühler, K. Predator-specific alarm calls in Campbell’s monkeys, Cercopithecus campbelli. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 50, 414–422 (2001).

Templeton, C. N., Greene, E. & Davis, K. Allometry of alarm calls: black-capped chickadees encode information about predator size. Science 308, 1934–1937 (2005).

Carlson, N. V., Healy, S. D. & Templeton, C. N. A comparative study of how British tits encode predator threat in their mobbing calls. Anim. Behav. 125, 77–92 (2017).

Evans, C. S., Macedonia, J. M. & Marler, P. Effects of apparent size and speed on the response of chickens, Gallus gallus, to computer-generated simulations of aerial predators. Anim. Behav. 46, 1–11 (1993).

Carlson, N. V., Healy, S. D. & Templeton, C. N. Mobbing. Curr. Biol. 28, R1081–R1082 (2018).

Lea, A. J., Barrera, J. P., Tom, L. M. & Blumstein, D. T. Heterospecific eavesdropping in a nonsocial species. Behav. Ecol. 19, 1041–1046 (2008).

Sherman, P. W. Nepotism and the evolution of alarm calls. Science 179, 1246–1253 (1977).

Griesser, M. Referential calls signal predator behavior in a group-living bird species. Curr. Biol. 18, 69–73 (2008).

Marler, P. Characteristics of some animal calls. Nature 176, 6–8 (1955).

Murphy, D., Lea, S. E. G. & Zuberbühler, K. Male blue monkey alarm calls encode predator type and distance. Anim. Behav. 85, 119–125 (2013).

Placer, J. & Slobodchikoff, C. N. A fuzzy-neural system for identification of species-specific alarm calls of Gunnison’s prairie dogs. Behav. Process 52, 1–9 (2000).

Cunningham, S. & Magrath, R. D. Functionally referential alarm calls in noisy miners communicate about predator behaviour. Anim. Behav. 129, 171–179 (2017).

Kalb, N. & Randler, C. Behavioral responses to conspecific mobbing calls are predator‐specific in great tits (Parus major). Ecol. Evol. 9, 9207–9213 (2019).

Kalb, N., Anger, F. & Randler, C. Subtle variations in mobbing calls are predator-specific in great tits (Parus major). Sci. Rep. 9, 6572 (2019).

Pell, F. S. E. D. et al. Birds orient their heads appropriately in response to functionally referential alarm calls of heterospecifics. Anim. Behav. 140, 109–118 (2018).

Suzuki, T. N. Alarm calls evoke a visual search image of a predator in birds. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 1541–1545 (2018).

Placer, J. & Slobodchikoff, C. N. A method for identifying sounds used in the classification of alarm calls. Behav. Process 67, 87–98 (2004).

Magrath, R. D., Haff, T. M., Fallow, P. M. & Radford, A. N. Eavesdropping on heterospecific alarm calls: from mechanisms to consequences. Biol. Rev. 90, 1–27 (2014).

Munoz, N., Brandstetter, G., Esgro, L., Greene, W. & Blumstein, D. T. Asymmetric eavesdropping between common mynas and red-vented bulbuls. Behav. Ecol. 26, 689–696 (2015).

Fuong, H., Keeley, K. N., Bulut, Y. & Blumstein, D. T. Heterospecific alarm call eavesdropping in nonvocal, white-bellied copper-striped skinks, Emoia cyanura. Anim. Behav. 95, 129–135 (2014).

Clucas, B. A., Freeberg, T. M. & Lucas, J. R. Chick-a-dee call syntax, social context, and season affect vocal responses of Carolina chickadees (Poecile carolinensis). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 57, 187–196 (2004).

Templeton, C. N. & Greene, E. Nuthatches eavesdrop on variations in heterospecific chickadee mobbing alarm calls. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 5479–5482 (2007).

Templeton, C. N. & Carlson, N. V. in Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior (ed Choe, J. C.) 568–580 (Oxford Academic Press, 2019).

Griesser, M. Do warning calls boost survival of signal recipients? Evidence from a field experiment in a group-living bird species. Front. Zool. 10, 49–53 (2013).

Griesser, M. & Suzuki, T. N. Naive juveniles are more likely to become breeders after witnessing predator mobbing. Am. Nat. 189, 58–66 (2017).

Suzuki, T. N. Communication about predator type by a bird using discrete, graded and combinatorial variation in alarm calls. Anim. Behav. 87, 59–65 (2014).

Curio, E., Ernst, U. & Vieth, W. Cultural transmission of enemy recognition: one function of mobbing. Science 202, 899–901 (1978).

Baker, M. C. Socially learned antipredator behaviour in black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus). Bird. Behav. 16, 13–19 (2004).

Wheeler, B. C., Fahy, M. & Tiddi, B. Experimental evidence for heterospecific alarm signal recognition via associative learning in wild capuchin monkeys. Anim. Cogn. 22, 687–695 (2019).

Potvin, D. A., Ratnayake, C. P., Radford, A. N. & Magrath, R. D. Birds learn socially to recognize heterospecific alarm calls by acoustic association. Curr. Biol. 28, 2632–2637.e4 (2018).

Magrath, R. D., Haff, T. M., McLachlan, J. R. & Igic, B. Wild birds learn to eavesdrop on heterospecific alarm calls. Curr. Biol. 25, 2047–2050 (2015).

Caro, T. M. Antipredator Defenses In Birds And Mammals (The University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Crofoot, M. C. Why mob? Reassessing the costs and benefits of primate predator harassment. Folia Primatol. (Basel) 83, 252–273 (2012).

Hughes, N. K., Kelley, J. L. & Banks, P. B. Dangerous liaisons: the predation risks of receiving social signals. Ecol. Lett. 15, 1326–1339 (2012).

Griesser, M. Mobbing calls signal predator category in a kin group-living bird species. Proc. R Soc. B 276, 2887–2892 (2009).

Billings, A. C., Greene, E., La Lucia, Jensen & De, S. M. Are chickadees good listeners? Antipredator responses to raptor vocalizations. Anim. Behav. 110, 1–8 (2015).

Goodale, E. & Kotagama, S. W. Testing the roles of species in mixed-species bird flocks of a Sri Lankan rain forest. J. Trop. Ecol. 21, 669–676 (2005).

Goodale, E. & Ruxton, G. D. in Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior Vol. 1 (eds Breed, M. D. & Moore, J.) 94–99 (Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, 2010).

Townsend, S. W., Rasmussen, M., Clutton-Brock, T. & Manser, M. B. Flexible alarm calling in meerkats: the role of the social environment and predation urgency. Behav. Ecol. 23, 1360–1364 (2012).

Coppinger, B. A., Sanchez de Launay, A. & Freeberg, T. M. Carolina chickadee (Poecile carolinensis) calling behavior in response to threats and in flight: flockmate familiarity matters. J. Comp. Psychol. 132, 16–23 (2018).

Woods, R. D., Kings, M., McIvor, G. E. & Thornton, A. Caller characteristics influence recruitment to collective anti- predator events in jackdaws. Sci. Rep. 8, 7343 (2018).

Rieucau, G. & Giraldeau, L.-A. Exploring the costs and benefits of social information use: an appraisal of current experimental evidence. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B 366, 949–957 (2011).

Giraldeau, L.-A., Valone, T. J. & Templeton, J. J. Potential disadvantages of using socially acquired information. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B 357, 1559–1566 (2002).

Barrera, J. P., Chong, L., Judy, K. N. & Blumstein, D. T. Reliability of public information: predators provide more information about risk than conspecifics. Anim. Behav. 81, 779–787 (2011).

Silvestri, A., Morgan, K. & Ridley, A. R. The association between evidence of a predator threat and responsiveness to alarm calls in Western Australian magpies (Cracticus tibicen dorsalis). PeerJ 7, e7572–17 (2019).

Fichtel, C. Ontogeny of conspecific and heterospecific alarm call recognition in wild Verreaux’s sifakas (Propithecus verreauxi verreauxi). Am. J. Primatol. 70, 127–135 (2008).

Hollén, L. I., Clutton-Brock, T. & Manser, M. B. Ontogenetic changes in alarm-call production and usage in meerkats (Suricata suricatta): adaptations or constraints? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 62, 821–829 (2007).

Alatalo, R. V. & Helle, P. Alarm calling by individual willow tits, Parus montanus. Anim. Behav. 40, 437–442 (1990).

Couchoux, C., Clermont, J., Garant, D. & Réale, D. Signaler and receiver boldness influence response to alarm calls in eastern chipmunks. Behav. Ecol. 29, 212–220 (2017).

Igic, B., Ratnayake, C. P., Radford, A. N. & Magrath, R. D. Eavesdropping magpies respond to the number of heterospecifics giving alarm calls but not the number of species calling. Anim. Behav. 148, 133–143 (2019).

McIvor, G. E., Lee, V. E. & Thornton, A. Testing social learning of anti-predator responses in juvenile jackdaws: the importance of accounting for levels of agitation. R. Soc. Open Sci. 5, 171571–12 (2018).

McLachlan, J. R., Ratnayake, C. P. & Magrath, R. D. Personal information about danger trumps social information from avian alarm calls. Proc. R Soc. B Biol. Sci. 286, 1899 (2019).

Billings, A. C., Greene, E. & MacArthur-Waltz, D. Steller’s jays assess and communicate about predator risk using detection cues and identity. Behav. Ecol. 28, 776–783 (2017).

van Bergen, Y., Coolen, I. & Laland, K. N. Nine-spined sticklebacks exploit the most reliable source when public and private information conflict. Proc. R. Soc. B 271, 957–962 (2004).

Hurd, C. R. Interspecific attraction to the mobbing calls of black-capped chickadees (Parus atricapillus). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 38, 287–292 (1996).

Hoppitt, W. & Laland, K. N. Social Learning: An Introduction To Mechanisms, Methods, And Models (Princeton University Press, 2013).

Griffin, A. S., Savani, R. S., Hausmanis, K. & Lefebvre, L. Mixed-species aggregations in birds: zenaida doves, Zenaida aurita, respond to the alarm calls of carib grackles, Quiscalus lugubris. Anim. Behav. 70, 507–515 (2005).

Hetrick, S. A. & Sieving, K. E. Antipredator calls of tufted titmice and interspecific transfer of encoded threat information. Behav. Ecol. 23, 83–92 (2011).

Schmidt, K. A., Lee, E., Ostfeld, R. S. & Sieving, K. E. Eastern chipmunks increase their perception of predation risk in response to titmouse alarm calls. Behav. Ecol. 19, 759–763 (2008).

Lilly, M. V., Lucore, E. C. & Tarvin, K. A. Eavesdropping grey squirrels infer safety from bird chatter. PLoS ONE 14, e0221279–15 (2019).

Bell, M. B. V., Radford, A. N., Rose, R., Wade, H. M. & Ridley, A. R. The value of constant surveillance in a risky environment. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 2997–3005 (2009).

Manser, M. B., Seyfarth, R. M. & Cheney, D. L. Suricate alarm calls signal predator class and urgency. Trends Cogn. Sci. 6, 55–57 (2002).

Ridley, A. R., Wiley, E. M. & Thompson, A. M. The ecological benefits of interceptive eavesdropping. Funct. Ecol. 28, 197–205 (2013).

Foote, J. R., Mennill, D. J., Ratcliffe, L. M. & Smith, S. M. Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus), version 2.0, Birds of North America (ed. Poole, A. F.) (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA, https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.39 2010).

Ghalambor, C. K. & Martin, T. E. Red-breasted nuthatch (Sitta canadensis), version 2.0. Birds of North America Online (eds Poole, A. F. & Gill, F. B.) 1–3 (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA, https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.459 1999).

Sullivan, K. A. Information exploitation by downy woodpeckers in mixed-species flocks. Behaviour 91, 294–311 (1994).

Griffin, A. S. Social learning about predators: a review and prospectus. Learn. Behav. 32, 131–140 (2004).

Hua, F. et al. Functional traits determine heterospecific use of risk-related social information in forest birds of tropical South-East Asia. Ecol. Evol. 6, 8485–8494 (2016).

Valone, T. J. From eavesdropping on performance to copying the behavior of others: a review of public information use. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 62, 1–14 (2007).

Rendell, L. E. et al. Cognitive culture: theoretical and empirical insights into social learning strategies. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 68–76 (2011).

Magrath, R. D., Pitcher, B. J. & Gardner, J. L. An avian eavesdropping network: alarm signal reliability and heterospecific response. Behav. Ecol. 20, 745–752 (2009).

Dutour, M., Lena, J. -P. & Lengagne, T. Mobbing behaviour in a passerine community increases with prevalence in predator diet. IBIS 159, 324–330 (2017).

Hollén, L. I. et al. Ecological conditions influence sentinel decisions. Anim. Behav. 82, 1435–1441 (2011).

Carlson, N. V., Pargeter, H. M. & Templeton, C. N. Sparrowhawk movement, calling, and presence of dead conspecifics differentially impact blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus) vocal and behavioral mobbing responses. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 71, 133 (2017).

Freeberg, T. M. & Harvey, E. M. Group size and social interactions are associated with calling behavior in Carolina chickadees (Poecile carolinensis). J. Comp. Psychol. 122, 312–318 (2008).

Vrublevska, J. et al. Personality and density affect nest defence and nest survival in the great tit. Acta Ethol. 18, 111–120 (2014).

Krams, I. A. Communication in crested tits and the risk of predation. Anim. Behav. 61, 1065–1068 (2001).

Dial, K. P., Greene, E. & Irschick, D. J. Allometry of behavior. TREE 23, 394–401 (2008).

Henry, K. S. & Lucas, J. R. Coevolution of auditory sensitivity and temporal resolution with acoustic signal space in three songbirds. Anim. Behav. 76, 1659–1671 (2008).

Greig, E. I. & Webster, M. S. How do novel signals originate? The evolution of fairy-wren songs from predator to display contexts. Anim. Behav. 88, 57–65 (2014).

R. Core Team. R: A Language And Environment For Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014).

Bates, D. M., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. M. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Luke Rendell and Lauren Chan for commenting on an earlier version of this manuscript, the many individuals who provided access to land and bird feeders, and to Dusty Thomas, Alexis Billings, Devin Landry, Madison Furlong, Ian Anderson, and Samuel Case who helped with fieldwork. Special thanks to Mark Reiling, Libby Maclay and Sapphire Ranch. This research was supported by the Philip L Wright Memorial Research Award and the Montana Integrated Learning Experience for Students (to N.V.C.); NERC fellowship (NE/J018694/1), National Institutes of Health Auditory Neuroscience Training Grant, funds from Pacific University, and the MJ Murdock Charitable Trust (to C.N.T.); and The National Science Foundation DEB 1258003 (to E.G. and Chris Clark).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.V.C., E.G. and C.N.T. developed and designed the experiments, carried out field work, and helped write and edit the manuscript. N.V.C. analysed the acoustic data and ran all statistical tests.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carlson, N.V., Greene, E. & Templeton, C.N. Nuthatches vary their alarm calls based upon the source of the eavesdropped signals. Nat Commun 11, 526 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14414-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14414-w

This article is cited by

-

Bio-acoustic tracking and localization using heterogeneous, scalable microphone arrays

Communications Biology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.