Abstract

Nutrients are absorbed solely by the intestinal villi. Aging of this organ causes malabsorption and associated illnesses, yet its aging mechanisms remain unclear. Here, we show that aging-caused intestinal villus structural and functional decline is regulated by mTORC1, a sensor of nutrients and growth factors, which is highly activated in intestinal stem and progenitor cells in geriatric mice. These aging phenotypes are recapitulated in intestinal stem cell-specific Tsc1 knockout mice. Mechanistically, mTORC1 activation increases protein synthesis of MKK6 and augments activation of the p38 MAPK-p53 pathway, leading to decreases in the number and activity of intestinal stem cells as well as villus size and density. Targeting p38 MAPK or p53 prevents or rescues ISC and villus aging and nutrient absorption defects. These findings reveal that mTORC1 drives aging by augmenting a prominent stress response pathway in gut stem cells and identify p38 MAPK as an anti-aging target downstream of mTORC1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of aging-related disorders is increasing due to aging of the population1. Nutrient malabsorption is common among the elderly, and often causes anemia and other illnesses2. Nutrients are absorbed by the intestinal villi, which are composed of a layer of intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) and the lamina propria, and the absorption activity is affected by the size and density of villi3. The epithelial layer is renewed every 4–5 days by Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells (ISCs) following a symmetric division and neutral shift pattern4,5,6, which generate transient amplifying (TA) progenitor cells that later differentiate into absorptive or secretory cells7. The densities of crypts and villi are controlled by ISC fission8. In addition, Bmi1+ quiescent stem cells, TA cells, and secretory progenitors can revert to Lgr5+ ISCs after damage to regenerate the villi9,10,11,12,13. It has been reported that the number of ISCs and ISC regenerative activities are decreased in 17–24-month-old mice14,15, yet whether aging affects villus function and how villus aging is controlled remain less well understood.

mTOR, a sensor of nutrients and growth factors, is a central regulator of aging and a target for lifespan and healthspan extension16,17,18,19,20. mTOR forms mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes, and mTORC1 activation promotes cell proliferation by increasing global protein synthesis and other anabolic processes21,22,23,24, which is assumed to cause irreversible cell senescence and/or oxidative and proteostatic stress and thus aging25,26,27,28. However, this hypothesis is not consistent with the reversible aging theory29,30. mTORC1 signaling has been shown to be required for IEC proliferation during homeostasis and regeneration31,32,33,34, including regeneration mediated by quiescent ISCs35,36. In addition, several studies have shown that diet restriction promotes Lgr5+ ISC expansion via mTORC1 signaling, although conflicting results have been reported regarding the exact roles played by mTORC114,37,38. Nonetheless, the mechanisms by which mTORC1 signaling regulates ISCs and villus aging warrant further investigation.

The current genetic study reveals that mTORC1, which is hyperactivated in IECs, especially ISCs and TA cells of aged mice, drives villus aging by inhibiting ISC/progenitor cell proliferation through amplifying the MKK6-p38-p53 stress response pathway, with MKK6 protein synthesis being upregulated by mTORC1 activation. Villus aging can be slowed or prevented by targeting p38 MAPK or p53. These genetic results establish a prominent stress response pathway as an mTORC1 downstream effector in aging control, elucidate the mechanisms governing villus aging, and identify p38 MAPK as an antiaging target downstream of mTORC1 signaling.

Results

Aging causes a decrease in the numbers of crypts and TA cells

To understand aging of the nutrient-absorbing organ, we collected small intestines from normal B6 mice of various ages, which were bred and housed in the same facility. Histological analysis revealed that 16 or 17.5-month-old mice, compared with 2-, 3.5-, 8-, and 12-month-old mice, showed significant decreases in the height and number of villi in the proximal and distal jejunum (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). The 17.5-month-old mice showed a 12% increase in body weight compared with 2–3-month-old mice. Mice at 24 months of age also showed villus structural deterioration (Supplementary Fig. 1c). These results indicate a decline in the absorption surface in aged mice, which are disagreeable with a recent study by Nalaparenddy et al. reporting an increase in the villus size in old mice15. While the causes of this discrepancy can be complex, one explanation could be that Nalaparenddy’s study used young and old mouse cohorts purchased from different suppliers15. We found that 16- or 17.5-month-old mice showed decreases in nutrient-absorbing activities for unmetabolizable L-glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 1d).

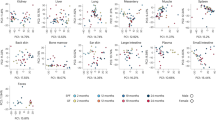

a–d Seventeen and half-month-old mice showed deterioration in villus and crypt structures (right panels: quantitation data) (a), decreased nutrient absorption activities (b), increased sensitivity to IR-induced decreases in the numbers of crypts and proliferating cells at day 2 post IR (c), and compromised regeneration (decreases in the height and number of villi and crypts) at day 6 (d) compared with young mice, which were partially rescued by 1.5 months of RAP treatment (3 mg/kg body weight) starting at 16 months of age. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). e Seventeen and half-month-old mice showed decreases in the height and number of crypts and the number of proliferating TA cells (based on (a)), which were rescued by RAP. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). f Representative images (proximal jejunum midline sections) showed that mTORC1 activation was increased with age in crypt cells. g Western blot results showed that mTORC1 activation was increased in the crypt samples of 17.5-month-old mice compared with 3.5-month-old mice. Isolated crypts were directly lysed and used for WB analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 3 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). h More Lgr5+ ISCs isolated from 17.5-month-old mice showed mTORC1 activation than those from 3.5-month-old mice, which was suppressed by RAP treatment. Lgr5+ ISCs were isolated from the small intestines of Lgr5-GFP-CreERT mice with FACS sorting and stained for p-S6. Right panel: quantification data (mean ± SEM). N = 6 mice per group. **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test).

The old mice also showed increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation (IR), manifested by greater decreases in the numbers of crypts and proliferating cells and greater increase in apoptotic cells than young mice at day 2 post IR (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 2a). This was associated with a decrease in PCNA and cyclin E and an increase in p53 in crypt samples (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Similar results were obtained at day 3 post IR (Supplementary Fig. 2c). The increased damage in old mice may be the cause of compromised villus regeneration observed at day 6 post IR, manifested by decreases in the height and number of villi and crypts (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. 2d). Overall, these findings indicate that aging is associated with a deterioration of villus structure and function, increased sensitivity to stress, and compromised regeneration.

Old mice also showed decreases in the height and number of crypts, the ISC/progenitor-containing glands that control villus size and density. We observed a decrease in the number of Ki67+ progenitor cells (Fig. 1a, e; Supplementary Fig. 1a), but no significant changes in the numbers of apoptotic or senescent cells or differentiation of villus cells after normalized to the villus size (Supplementary Fig. 2e–g). Although the numbers of villi and crypts were decreased in old mice, the crypt-to-villus ratio was unaltered (Supplementary Fig. 2h), suggesting that aging-related decreases in villus height and density may be caused by decreases in the numbers of proliferating TA cells and crypts, respectively. Yilmaz’ group also reported that aging caused decreases in the number and regeneration ability of ISCs, but not defect in goblet or enterocyte differentiation14. Taken together, our and others’ studies suggest that villus aging-associated decrease in villus size and density are likely caused by defects in ISCs and TA progenitors14,15.

Hyperactivated mTOR in IECs contributes to villus aging

mTOR activation is implicated in the aging process34,39. Immunostaining showed that p-4E-BP1 and p-S6, indicators of mTORC1 activation, were increased with age in IECs, especially in crypt cells (Fig. 1f). Western blot analysis confirmed an increase in mTORC1 activation in crypt samples of old mice (Fig. 1g). Because the number of ISCs was too limited for western blot analysis, we sorted Lgr5+ ISCs from 3.5- and 17.5-month-old Lgr5-GFP-CreERT mice and immunostained them for p-S6. We found that substantially more ISCs displayed mTORC1 activation in old mice (Fig. 1h). The factors that cause mTORC1 hyperactivation in aged IECs and ISCs may include systemic and niche cues and, warrant further investigation39,40.

Interestingly, treatment of 16-month-old mice with rapamycin (RAP), an mTORC1 inhibitor21, for 1.5 months inhibited mTORC1 activity (Supplementary Fig. 2i) and partially rescued aging-like phenotypes, including decreases in villus height and density and nutrient absorption activities, increased sensitivity to IR at day 2, and compromised villus regeneration at day 6 post IR (Fig. 1a–d; Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). It has been previously reported that acute RAP inhibited villus regeneration in normal mice31,33,36. Here, we carried out the above experiments 3 days after completion of drug treatment to avoid possible acute effects of RAP. Moreover, RAP mainly rescued IR-induced decrease in cell proliferation and increase in apoptosis at day 2 or 3 post IR (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 2a–c), which might help villus regeneration. In addition, RAP partially rescued the decreases in the height and number of crypts and the number of proliferating TA cells in old mice (Fig. 1a, e). These results suggest that enhanced mTORC1 activation contributes to villus natural aging.

Tsc1 ablation in IECs causes villus premature aging

To test whether mTORC1 activation causes villus aging, we ablated Tsc1, a disease gene encoding an mTOR suppressor, using Villin-Cre mice. Villin is expressed in all small intestinal IECs, including ISCs, but not colon crypts41. Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice exhibited enhanced mTOR activation in the whole villi (Supplementary Fig. 3a). We found that 2- or 3-month-old Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice showed increases in the number and size of crypts, but insignificant increases in villus size (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The nutrient absorption rates were not altered in these mice (Supplementary Fig. 3c), suggesting that mTORC1 activation in IECs per se does not affect nutrient absorption in the presence of normal villi. Surprisingly, 4–6-month-old mutant mice showed villus/crypts similar to age-matched wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Starting from 7 months of age, the mutant mice displayed aging-related changes, including decreases in villus height and density, nutrient absorption activities, and villus regeneration (Supplementary Fig. 3b–d). The compromised regeneration in Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice was likely caused by increases in IR-induced cell death and villus damage at day 2 post IR (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Overall, these results indicate that Tsc1 deletion in IECs cause villus premature aging.

Tsc1 ablation in ISCs-induced villus aging is rescued by RAP

The above studies show that nutrient absorption defects observed in villus natural or premature aging models are associated with decreases in villus size and density, whereas mTORC1 activation per se in IECs does not affect nutrient absorption activities at young age (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Since villus size and density are controlled by ISC and progenitor cells, we ablated Tsc1 in ISCs using Lgr5-CreERT mice4. Lgr5-CreERT reportedly only labels part of ISCs after tamoxifen (TAM) administration and generates chimeric labeling patterns4. Our lineage-tracing studies revealed that three doses of TAM administered daily to 1-month-old Lgr5-CreERT;tdTomato mice labeled 65% of the crypts by 2 months of age (Supplementary Fig. 4a). A majority of the cells in almost all the villi were Tomato-labeled, likely because each villus contains at least six crypts7.

We found that TAM-induced Tsc1 ablation in Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice at 1 month of age led to an increase in mTORC1 activation in most of the cells of almost all the villi by 2 months of age (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 4b). These mice showed increases in the size and number of crypts, but insignificant increases in villus size (Fig. 2b). The nutrient absorption activities were unaltered in these mutant mice (Fig. 2c), confirming that mTORC1 activation in IECs per se does not affect their nutrient absorption activities. However, mice of 7 months of age or older displayed a slight but insignificant decrease in body weight and premature aging phenotypes, including changes in villus height and density (proximal and distal jejunum) and nutrient absorption activities (Fig. 2b, c; Supplementary Fig. 5a).

a A schematic for conditional ablation of Tsc1 and RAP treatment in Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice (b–e). b H/E and Ki67 staining showed that ablation of Tsc1 in Lgr5+ ISCs led to crypt overgrowth at 2 months of age and deterioration of villus structure (the midline section of the proximal jejunum) at 8 months of age, which were partially rescued by RAP. Right panels: quantification data (mean ± SEM). N = 8 mice per group. **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). c Eight-month-old Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice showed decreased nutrient absorption activities for L-glucose (mmol/l), amino acids (ng/ml), and fatty acids, which were partially rescued by RAP treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). d, e Eight-month-old Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice showed increased sensitivity to IR-induced decreases in the numbers of crypts and proliferating cells at day 2 post IR (d), and compromised regeneration (decreases in the height and number of villi and crypts) at day 6 post IR (e), which were partially rescued by RAP treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test).

The mutant mice also showed increased sensitivity to IR, manifested by greater decreases in the numbers of crypts and proliferating cells and greater increase in apoptotic cells than control mice at day 2 post IR (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. 5b), associated with a decrease in PCNA and cyclin E and an increase in p53 in crypt samples (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Similar results were obtained at day 3 post IR (Supplementary Fig 5d). This might have led to compromised villus regeneration at day 6 post IR (Fig. 2e). Although mTOR signaling is required for villus regeneration31,33,36, we found that mTOR hyperactivation sensitized the cells to IR-induced damage, which might delay the regeneration process. Note that most of the crypts and almost all the villi showed increased mTORC1 activation in 8-month-old Lgr5-CreERT; Tsc1f/f mice to a greater extent than that in 2-month-old Lgr5-CreERT; Tsc1f/f mice (Supplementary Fig. 4b).

The villus premature aging phenotypes of Lgr5-CreERT; Tsc1f/f mice could be partially rescued by 1.5 months of RAP treatment starting at 6.5 months of age (Fig. 2a–e). This included the rescue of IR-induced decrease in cell proliferation and increase in apoptosis at day 2 or 3 post IR (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. 5d). RAP could also inhibit mTORC1-driven crypt overgrowth in Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice at 2 months of age (Supplementary Fig. 5e), suggesting that villus growth and aging are at least partially mediated by elevated mTORC1 activation. In addition, Tsc1 deletion led to an overgrowth phenotype in colon crypts at 2 months of age, followed by crypt atrophy at 7 months of age, which were rescued by RAP (Supplementary Fig. 5b). These results revealed biphasic effects of mTORC1 activation on Lgr5+ ISCs in the small intestine and colon.

Our findings that (i) mTORC1 is greatly activated in ISC and progenitor cells of aged mice; (ii) nutrient absorption is normal even when mTORC1 is activated in IECs of young Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice and Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice, which have normal villus size and density; (iii) aging-related nutrient absorption decline is always associated with decreases in villus size and density, which are controlled by Lgr5+ ISCs, suggesting that activated mTORC1 promotes villus aging mainly through ISCs.

mTORC1-driven villus aging may not rely on overgrowth

Both Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice and Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice showed increases in the size of crypts at 2–3 months of age before showing villus premature aging at 7–8 months of age (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 3b). Is it possible that villus overgrowth at 2–3 months of age causes villus premature aging later? Our observation that RAP administration to 6.5-month-old mice could rescue villus aging phenotypes, suggests that villus premature aging is not an inevitable consequence of mTORC1-driven crypt overgrowth at 2–3 months of age (Fig. 2b–e); such rescue may not occur if mTORC1-driven aging is caused by irreversible ISC/TA cell replicative senescence and/or apoptosis. For validation, we induced Tsc1 ablation in Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice at 6.5 months of age. These mice displayed aging-like phenotypes at 8 months of age, including changes in villus height and density and nutrient absorption activities (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c). However, TAM administration failed to induce crypt overgrowth at 7.5 months of age (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Overall, these results suggest that mTORC1-driven villus premature aging may not rely on mTORC1-driven crypt overgrowth.

mTORC1 activation eventually suppresses ISC proliferation

What caused the decreases in villus height and density in 8-month-old Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice? We found that the decrease in villus height was accompanied by decreases in the number of IECs and the number of Ki67+ progenitors (Figs. 2b, 3a, b). On the other hand, IEC apoptosis, senescence, or differentiation were not significantly altered (Supplementary Fig. 5f–h). In addition, the decrease in the number of villi was accompanied by a decrease in the number of crypts (Fig. 2b). Since the villus-to-crypt ratio was not altered (Fig. 3c), we conclude that decreased villus density is caused by decreased numbers of crypts. Overall, these results suggest that the decreases in villus size and density in Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice at 7–8 months of age are caused by defects in the crypts and TA cell proliferation.

a, b Eight-month-old Lgr5-GFP-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice showed decreases in the number of IECs (a) and the number of proliferating TA cells (b) (based on Fig. 2b). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 4 mice per group. **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). c Eight-month-old Lgr5-GFP-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice showed no change in the villus-to-crypt ratios. N = 4. d Representative images showing that Tsc1−/− crypts (isolated from Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice, since Lgr5-GFP-CreERT can label ~65% of the crypts) displayed increases in the size of the minigut organoids and the number of crypts, whereas serial passaging of the organoids revealed that Tsc1-deficient organoids quickly lost their ability to propagate. Right panels: quantification of the data (mean ± SEM). N = 3 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). e Eight-month-old Lgr5-GFP-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice showed decreases in the numbers of ISCs and proliferating ISCs. Intestine sections were immunostained for PCNA, and cells positive for PCNA and GFP were counted and normalized to the total numbers of Lgr5+ ISCs. Bottom panels: quantitation data (mean ± SEM). N = 5 mice per group. **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). f The numbers of ISCs and proliferating ISCs were decreased in naturally aged 17.5-month-old mice. Right panels: quantitation data (mean ± SEM). N = 3 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test).

We then used ex vivo organoid cultures to verify these findings. We isolated crypts from 2-month-old normal or Villin-Cre; Tsc1f/f mice and performed ex vivo minigut organoid cultures. Tsc1-deficient crypts showed increased growth in organoid cultures; however, they lost the ability to propagate at passage 3 (Fig. 3d), confirming the biphasic roles of mTORC1 signaling in crypt growth and aging.

Tsc1 ablation-induced premature villus aging was also associated with defects in ISCs. At 8 months of age, the number of crypts containing Lgr5-expressing ISCs and the number of Lgr5+ ISCs per crypt were decreased, whereas the opposite results were observed at 2-month-old Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice (Fig. 3e). Moreover, the number of proliferating Lgr5+ ISCs was also decreased in 8-month-old Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice (Fig. 3e). Similarly, the numbers of Lgr5+ ISCs and proliferating Lgr5+ ISCs were decreased in naturally aged mice (Fig. 3f). Overall, these results suggest that both Tsc1 deficiency-induced villus premature aging and natural aging are likely caused by decreases in the number of ISC/TA cells.

mTORC1 increases MKK6 protein synthesis and p38 activation

To understand the molecular basis underlying mTORC1-driven villus premature aging and decreased ISC/TA cell proliferation, we used antibody arrays (204 antibodies) to compare the expression and activation of proteins involved in cell proliferation. To this end, we compared snap-frozen intestine samples of Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f and control mice to minimize possible effects of crypt isolation procedures on protein phosphorylation. We found that Tsc1 deficiency altered the expression and activation of several signaling molecules, including p38 MAPK, MEK1, and p53 (Supplementary Table 1). We chose p38 MAPKs for further studies since they are stress-responsive kinases that are involved in aging42. Western blot analysis revealed that the levels of MKK6 protein and p38 MAPK activation were increased in Tsc1−/− villus samples and Tsc1−/− organoid samples (Fig. 4a, b). Mechanistically, Tsc1 deficiency did not significantly affect the mRNA levels of Mkk6 in crypt samples (Fig. 4c). Instead, incorporation of radio-labeled methionine into MKK6 was increased in Tsc1−/− primary enteroblasts, which were suppressed by RAP treatment (Fig. 4d). Increases in MKK6 protein and p38 MAPK activation were also observed in Tsc1−/− MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 7a–c). We found that transient knockdown of MKK6 with siRNA led to a decrease in p38 MAPK activation (Supplementary Fig. 7d), indicating that elevated MKK6 is responsible for enhanced p38 MAPK activation in Tsc1-deficient cells. mTORC1 has been shown to increase protein synthesis of transcripts with 5′ terminal oligopyrimidine (TOP) or TOP-like motifs43. Mouse Mkk6 transcripts contain several TOP or TOP-like tracts in the 5′ untranslated region (Supplementary Fig. 7e). These results suggest that mTORC1 activation promotes protein synthesis of MKK6 and thus enhances p38 MAPK activation.

a, b Western blot results showed that the levels of MKK6 and activation of p38 MAPKs were increased in villus samples of Villin-Cre; Tsc1f/f mice (a) and Tsc1-deficient organoids (b) compared with those in controls. Right panels: quantification data (mean ± SEM). N = 4 mice for a and 3 for b. **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). c Tsc1 deficiency did not significantly affect the mRNA levels of Mkk6 in crypt samples. The total RNA was isolated from the crypt samples, converted into cDNA, and then used for quantitative PCR analysis. N = 4 mice per group. d Tsc1 deficiency led to an increase in radio-labeled methionine incorporation into MKK6, which were suppressed by RAP. Primary enteroblast cultures were pulse-labeled with 35S Met and Cys for 1 h. The cells were collected, and MKK6 was immunoprecipitated and fractionated onto SDS-PAGE gels, which were dried; the signals were detected with a PhosphorImager. Right panels: quantification data (mean ± SEM). N = 3 mice per group. *P < 0.05 (determined using Student’s t test). e Western blot analysis revealed that crypt samples from 8-month-old Lgr5-GFP-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice showed increases in MKK6 expression, p38 MAPK activation, and mTORC1 activation compared with those from 2-month-old mice. Right panels: quantification data (mean ± SEM). N = 3 per group. *P < 0.05 (determined using Student’s t test).

Moreover, comparison of crypt samples of 2- and 8-month-old Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice by western blot revealed that p38 MAPK activation was further augmented in the old mice, accompanied by an increase in mTORC1 activation (Fig. 4e). Immunostaining results confirmed enhanced p38 activation in the crypts of old mice (Supplementary Fig. 7f). Increased mTORC1 activation was also observed on intestine sections of 8-month-old mice compared with 2-month-old mice (Fig. 1f; Supplementary Fig. 4b). These results suggest that extrinsic and/or intrinsic changes at 7–8 months of age may be involved in enhanced activation of mTORC1 and p38 MAPKs in ISCs and IECs.

Mapk14 ablation prevents mTORC1-driven villus and ISC aging

Because the p38 MAPK pathway plays a negative role in cell proliferation under most conditions42, enhanced p38 MAPK activation may underlie mTORC1-driven ISC/progenitor aging. To test this possibility, we ablated Mapk14, which encodes p38α, in Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice to circumvent the possible complication of chimeric ablation of Tsc1 and Mapk14. We found that 2-month-old Villin-Cre;Mapk14f/f mice, like Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice, showed decreased p38α expression and increases in the number and size of crypts (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b), as previously reported44. Moreover, Mapk14 ablation prevented the development of aging-related histological phenotypes, leading to crypt overgrowth and fusion in 8-month-old Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice (Supplementary Fig. 8b).

We also ablated Mapk14 in Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice (Supplementary Fig. 9a), and found that deletion of just one allele of Mapk14 prevented the development of villus premature aging phenotypes at 8 months of age, including defects in villus structure, nutrient absorption activities, and villus regeneration at day 6 post IR (Fig. 5a–c). Mapk14 haploinsufficiency also rescued increased sensitivity to IR at day 2 post IR (Supplementary Fig. 9b–d), the decrease in the numbers of proliferating TA cells, Lgr5+ ISC-containing crypts, Lgr5+ ISCs per crypt, and proliferating Lgr5+ ISCs, as well as mTORC1-driven colon crypt atrophy (Fig. 5d; Supplementary Fig. 9e). Overall, these genetic data suggest that p38 MAPKs mediate mTORC1-driven ISC and villus premature aging. A recent study reported that mitochondria-produced reactive oxygen species activate p38 MAPKs to drive crypt formation in organoid cultures45. Together, these results suggest that p38 MAPKs play critical roles in ISC activities.

a–c Mapk14 haplodeficiency rescued the deterioration in villus structures (a), decreased nutrient absorption activities (b), and compromised regeneration (c) at 8 month of age. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). d Mapk14 haplodeficiency rescued the decreases in the numbers of ISCs and proliferating ISCs in 8-month-old Lgr5-GFP-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice. The intestinal sections were immunostained for PCNA, and cells positive for PCNA and GFP were counted and normalized to the number of Lgr5+ ISCs. Bottom panels: quantitation data (mean ± SEM). N = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test).

A p38 MAPK inhibitor partially rescues villus natural aging

The above studies show that p38 MAPKs play an important role in mTORC1-driven villus/ISC premature aging. To test whether p38 MAPK plays a role in villus natural aging, we compared the crypts of 3.5- and 17.5-month-old normal mice and discovered increases in MKK6 expression and p38 activation in the old mice, which were associated with increased mTORC1 activation and were suppressed by RAP treatment (Fig. 6a). We then tested whether a small molecule inhibitor of p38 MAPK can slow villus natural aging. Administration of SB203580 to 16-month-old normal mice for 1.5 months inhibited p38 MAPK activation, manifested by decreases in phosphorylation of p38 MAPK substrate Creb (Supplementary Fig. 9f), and alleviated villus aging phenotypes, including villus structure, nutrient absorption activity, and compromised regeneration (Fig. 6b–d), as well as decreases in the number of proliferating TA cells (Fig. 6b). Inhibition of p38 MAPK has been shown to slow aging of skeletal muscle46. Moreover, we found that organoids derived from 17.5-month-old mice showed defects in growth and crypt formation, which were partially rescued by addition of low doses of SB203580 or RAP to the cultures (Fig. 6e), suggesting that the effects of SB203580 and RAP are directly on crypt cells. Furthermore, Lgr5-CreERT;Mapk14+/f mice (TAM injected at 2 months of age) showed modest villus/crypt overgrowth but not aging-like phenotypes at 16 months of age (Fig. 6f). These results suggest that elevated p38 signaling inhibits TA cell proliferation and promotes villus natural aging.

a Western blot results showed that 17.5-month-old mouse crypt samples displayed elevated MKK6 expression, increased p38 MAPK activation, and increased p53 and p16 levels, which were suppressed by RAP treatment for 1.5 months starting at 16 months of age. Right panel: quantification data (mean ± SEM). N = 3 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). b–d Inhibition of p38 MAPK largely rescued the deterioration in villus and crypt structures (b), decreased nutrient absorption activities (c), and compromised regeneration (d) in 17.5-month-old normal mice. The mice were treated with SB203580 for 1.5 months. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). e Representative images showing that SB203580 (2 μM) or RAP (0.5 μM) partially rescued the defects in growth and crypt formation of minigut organoids isolated from 17.5-month-old mice. The inhibitors were added to the culture at day 1 of the organoid cultures. Bottom panels: quantification data (mean ± SEM). N = 3 mice per group. **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test). f Lgr5-CreERT;Mapk14f/+ mice (TAM injected at 2 months of age) did not show aging-like villus structural defects at 16 months of age. The intestines were sectioned and stained with H/E or Ki67 antibodies. Right panels: quantification data (mean ± SEM). N = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined using Student’s t test).

mTORC1 upregulates p53 and p16 expression via p38 MAPKs

How does p38 MAPK activation, downstream of mTORC1-MKK6, induce villus aging? Accumulating evidence suggests that p38 MAPK regulates aging via p53, p16, and other molecules47,48,49. Our antibody array and western blot results revealed that naturally aged crypt samples or Tsc1-deficient prematurely aged crypt samples showed increased levels of p53 and p16, which were suppressed by RAP treatment of the mice (Supplementary Fig. 10a, Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, aging- or mTORC1 activation-induced increases in the levels of p53 and p16 in crypt samples were suppressed by Mapk14 deficiency or inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 10b, c). These results indicate that mTORC1 activation induces p53 and p16 expression in a p38 MAPK-dependent manner.

p53 is critical in mTORC1-p38 MAPK-controlled villus aging

We then tested whether p53 and p16 contribute to mTORC1-driven villus aging. Although Trp53−/− mice started to develop tumors at 5–6 months of age, many survived up to 7–8 months with no obvious tumor development. While 2- or 8-month-old Trp53−/− mice showed normal villus structure, Trp53 deficiency enhanced crypt growth in Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice and largely prevented development of villus premature aging phenotypes, including decreases in villus structure, nutrient absorption activities, increased sensitivity to IR, and decreased villus regeneration at 7 months of age (Fig. 7a–c; Supplementary Fig. 10d). We also repeated these experiments using Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f;Trp53−/− mice and found that Trp53 deficiency rescued the decreases in proliferating TA cells and the numbers of Lgr5+ ISC-containing crypts, Lgr5+ ISCs per crypt, and proliferating Lgr5+ ISCs as well (Fig. 7d). These results indicate that p53 plays an important role in Tsc1 deletion-driven villus aging.

a–c Deletion of Trp53 rescued the deterioration in villus and crypt structures (a), decreased nutrient absorption activities (b), and compromised regeneration (c) in 8-month-old Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.0 (determined using Student’s t test). d Trp53 ablation rescued the decrease in the numbers of ISCs and proliferating ISCs in 8-month-old Lgr5-GFP-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice. The intestinal sections were immunostained for PCNA, and cells positive for PCNA and GFP were counted and normalized to the total numbers of Lgr5+ ISCs. Bottom panels: quantification data (mean ± SEM). N = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.0 (determined using Student’s t test). e A model for controlling gut stem and progenitor cell aging by mTORC1.

p16 (encoded by Cdkn2a) plays an important role in aging of several tissues48,50. However, 2- or 8-month-old Cdkn2a−/− mice showed normal villus histology, and Cdkn2a ablation failed to affect villus growth in 2-month-old Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice. Cdkn2a deficiency showed negligible effects on aging-related histology in 8-month-old Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice (Supplementary Fig. 10e). These results suggest that p16 plays a lesser role than p53 in mTORC1-driven villus aging.

Discussion

Aging-related nutrient malabsorption is a common disorder, yet the underlying etiology remains elusive. This study reveals that aging is associated with decreases in villus height and density and nutrient absorption activities, as well as increased sensitivity to IR, which may be the cause of compromised villus regeneration. These aging-related phenotypes are recapitulated in 7–8-month-old Lgr5-CreERT;Tsc1f/f mice and Villin-Cre;Tsc1f/f mice. Aging-related villus structural deterioration was accompanied by decreases in the number and height of crypts and the number and proliferation of ISCs. These findings, together with our observation that Tsc1 ablation and mTORC1 activation in IECs do not affect villus cell differentiation or nutrient absorption activities in 2–3-month-old mice, suggesting that aging-related malabsorption is mainly attributable to exhaustion of gut stem cells and their reduced activity, which result in decreases in villus size and density.

While aging can be caused by complex mechanisms, we provide genetic evidence that villus and ISC aging may involve mTORC1 signaling. mTORC1 is strongly activated in ISCs and TA cells in old mice, and inhibition of mTORC1 with RAP for only 1.5 months partially restored the structure and function of intestinal villi in old mice. Moreover, Tsc1 ablation in Lgr5+ ISCs leads to villus premature aging phenotypes and crypt atrophy in Paneth-less colon, which were rescued by RAP treatment. These data suggest that mTORC1 is an important regulator of gut stem cell and villus aging. Our conclusions are generally consistent with those of a recent study showing that diet restriction helps expand ISCs by inhibiting mTORC1 signaling37, but inconsistent with another study showing that diet-restriction-induced ISC expansion is inhibited by RAP38. What causes enhanced mTORC1 activation in aged IECs and ISCs? It is possible that age-related changes in systemic factors may be involved, which are now being vigorously explored40,51,52. These factors may include nutrients, metabolites, and growth factors14,45, and warrant further investigation.

Our studies also show that mTORC1 activation promotes ISC/TA cell proliferation in young mice. While mTORC1-driven cell hyperproliferation and anabolism are generally presumed to cause aging53, our study suggests that in the fast-turnover intestinal villi, mTORC1 activation-induced aging may not necessarily require mTORC1-induced overgrowth in earlier stages based on the following observations: (i) ablation of Tsc1 in Lgr5+ ISCs at 6.5 months of age circumvents the villus overgrowth phase, which occurs at 2–3 months of age, but still induces villus premature aging; (ii) villus aging in Tsc1-deficient mice can be partially rescued by the administration of p38 or mTORC1 inhibitors to old mice; and (iii) Mapk14 ablation increases crypt cell proliferation, but rescues villus premature aging. These results suggest that Tsc1 deletion-driven ISCs exhaustion and villus aging are not directly caused by mTORC1-driven cell overproliferation.

Instead, we show that mTORC1 signaling promotes villus aging by augmenting a cell stress response pathway. mTORC1 activation increases MKK6 expression, potentiates p38 MAPK activation, and enhances p53 expression, leading to ISC exhaustion and decreases in villus size and density (Fig. 7f). Moreover, mTORC1 activation also increases cell sensitivity to IR and compromises villus regeneration in a p38 MAPK-p53-dependent manner, which is consistent with cell-based studies showing that mTORC1-activated cells are more sensitive to stress47. The natural function of the mTOR-MKK6-p38 MAPKs-p53 pathway may be to balance mTORC1-induced overgrowth and protect cells from runaway proliferation and oncogenic transformation, which is consistent with the concept that aging acts as an anti-hyperplasia mechanism42.

This study places p38 MAPK downstream of mTORC1 signaling in controlling ISC/villus aging. p38 MAPK has been implicated in the aging of skeletal muscle and other tissues42. We show that a p38 MAPK inhibitor can effectively improve the structure and function of naturally aged villi and that Mapk14 ablation can prevent ISC and villus aging. These results justify p38 MAPK as an antiaging target. Since p38 MAPKs can be activated by various stress and cytokines, p38 MAPK may act as a nexus to incorporate environmental cues to influence the aging process. These insults may include mTOR activation-induced oxidative and ER/proteostatic stress, which may lead to further activation of p38 MAPKs (Fig. 7f). Our findings favor a model in which mTORC1 signaling cooperates with p38 MAPK-activating stresses to regulate aging of tissue stem cells (Fig. 7f).

Emerging evidence indicates that mTOR is a central regulator of aging that may mediate RAP- and diet restriction-induced extension of the lifespan and healthspan. While mTORC1-driven cell proliferation and incurred oxidative and proteostatic stress are generally believed to underlie cell and tissue aging, this study provides genetic evidence that mTORC1 can regulate tissue stem/progenitor cell aging and tissue aging via a prominent stress response pathway. These findings reveal a mechanism by which mTORC1 signaling regulates aging and this working model can explain the reversibility of aging.

Methods

Mice maintenance

Tsc1f/f, Villin-Cre, and Trp53−/− mouse lines were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories. The Lgr5-CreERT mouse was generated in Hans Clevers’ lab. Mapk14f/f was generated in Yibin Wang’s lab. Cdkn2a−/− mouse was generated in Ron Depinho’s lab. These mice were maintained in SPF mouse facility of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Most of the mice were originally in a 129/B6 background and were crossed back to B6 for four times. They can live up to 30 months in the facility. Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with recommendations in the National Research Council Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and in comply with relevant ethical regulations for animal testing and research, with the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Mouse drug administration and radiation

Tamoxifen (Sigma) was dissolved in corn oil, and mice were injected with 10 mg per dose daily for 3 consecutive days to activate CreERT. To inhibit mTORC1, mice were injected with RAP (3 mg/kg, Selleck, s1039) daily for the periods indicated in the study. To inhibit p38 MAPKs, mice were injected with SB203580 (5 mg/kg, Selleck, S1076) daily for the time indicated in the study. For long-term RAP or SB203580 administration, we waited at least 3 days after completion of drug treatment before doing experiments to avoid acute effects of the drugs. For ionizing radiation, mice were exposed to γ-irradiation with a dose of 5 Gy, and mice were killed 2, 3, or 6 days after IR.

Nutrients absorption assays

The mice were fasted for 16 h before nutrient assays54,55,56. For glucose absorption test, the mice were gavaged with L-glucose solution (2 mg/g, body weight) in PBS, blood samples were collected from the tail vein at 0, 7, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min, and blood glucose levels were determined, with the value at 60 min used as an indication of glucose absorption activity. For amino acid absorption test, the mice were gavaged with amino acids mixture (2 mg/g, body weight), blood samples were collected from the tail vein at different time points, and blood amino acid levels were determined with HPLC. The peak value (at 1 h) was used to represent amino acid absorption activity. For fatty acid absorption test, the mice were gavaged with BODIPY® 500/510 C1, C12 fatty acids (2 μg/g body weight, Molecular Probes #D3823), or olive oil (10 μl/g body weight). After 2 h, small intestines were excised and frozen in OCT. Ten-μm sections were cut, mounted with ProLong® Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI, and examined under the fluorescence microscope. In nutrient absorption studies, no significant difference was observed between male and female mice.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Small intestines were harvested immediately after killing and washed with PBS. The tissues (the proximal and distal jejunum and proximal colon) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned longitudinally at 4-μm, and the midline sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H/E), ALP or Alcian Blue. For immunostaining, antigen retrieval was carried out by boiling the sections in citrate buffer, pH 6, for 10 min, followed by cooling for 60 min at room temperature. To eliminate endogenous peroxidases, tissues were treated in methanol containing 3% H2O2 for 30 min. Tissues were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min. The sections were blocked in 10% goat serum for 30 min followed by primary antibodies incubation at 4 °C overnight, and secondary antibody incubation for 60 min at 37 °C. Antibodies against Ki67 (ab15580, 1:100) and Lysozyme (ab108508, 1:100) were purchased from Abcam. Antibodies against GFP (2956, 1:200), p-S6 (2211, 1:100), p-p38 (9211, 1:100), and p-Erk1/2 (9106, 1:200) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies against PCNA (sc-56, 1:100) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Antibody array analysis

To compare the activation and expression of proteins involved in cell proliferation, we chose to use snap-frozen small intestine samples of wild-type and Villin-Cre; Tsc1f/f mice since isolated crypts by enzyme digestion at 37 °C produced inconsistent results. The samples were analyzed with phospho-Exploerer (PEX100) by the H-Wayen Biotechnologies.

Crypt isolation and culture and GFP+ ISCs sorting

To isolate crypts, the small intestine, mostly jejunum and ileum, was removed immediately, and the stool was flushed out with ice-cold PBS. The tissues were dissected and opened longitudinally and cut into 1 -cm pieces, which were placed in PBS with 2 mmol/L EDTA for 30 min at 4 °C and then in PBS with 54.9 mmol/L d-sorbitol and 43.4 mmol/L sucrose. The pieces were then vortexed for 1–2 min, filtered by a 70 μm sterile cell strainer, and enriched by centrifugation at 150 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Nearly 500 crypts were suspended in 50 μL growth factor reduced phenol-free Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Afterward, a 50 μL droplet of Matrigel/crypt mix was put in the center well of a 12-wells plate and after 30 min of polymerization, 650 μl of minigut medium was overlain. Minigut medium (advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with HEPES, l-glutamine, N2, and B27) was added to the culture with R-Spondin, Noggin, and EGF. The medium was changed every 2–3 days. For GFP+ ISCs isolation, we first isolated crypts and digested them at 37 °C for 5 min with 0.25% trypsin, centrifuged at 150–200 g for 3 min, and resupensed in 0.1% BSA in ice-cold PBS. We purified GFP+ cells with FACS sorting and collected. These cells were resupensed in PBS, smeared onto coated slides, dried at 4 °C. The slides were then fixed in 4% PFA, and GFP+ cells were countered under the fluorescence microscope.

Epithelial cell isolation and culture

For primary IECs isolation, intestines were opened longitudinally and washed in Ca2+ and Mg2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 2% glucose, 25 ng of amphotericin B/ml, 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 100 mg of streptomycin/ml, which were cut into 1-mm fragments and incubated for 10 min at 22 °C on a shaker platform in HBSS containing collagenase XIa (Sigma), 2% bovine serum albumin, and 0.2 mg of soybean trypsin inhibitor/ml (Sigma). Cells and small sheets of intestinal epithelium were separated from the denser intestinal fragments by harvesting supernatants after two 60-s sedimentations in medium containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco), 10% sorbitol (Gibco), 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 mg of streptomycin/ml, and 5% fetal bovine serum. Cells were centrifuged five times at 1200 g for 3 min in DMEM plus 2% sorbitol. Supernatants were discarded, and the cells were cultured in 10-cm plates coated with 40 ml of Matrigel per cm2 diluted 1:2 in phenol-red-free DMEM (Sigma).

S35-methionine incorporation assay

Primary IECs were pre-incubated with DMEM without methionine and cysteine for 30 min, and then labeled with EasyTag™ EXPRESS 35S Protein Labeling Mix (NEG772007MC) for 1 h. To determine the rates of protein synthesis, cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with individual antibodies. Antibodies against MKK6 (9264, 1:250) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibody against Gapdh (sc32233, 1:250) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The immunoprecipitates were eluted and subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the gel was dried and visualized with phosphoimaging.

Western blot analysis

For Villin-Cre; Tsc1f/f mice, villus tissues were scraped from the small intestines. For Lgr5-CreERT; Tsc1f/f mice, crypts were isolated. In these experiments, the mice were starved overnight and harvested in the following morning. These samples were lysed in T-PER™ Tissue protein extraction reagent purchased from Thermo Scientific (78510) containing 1 mM PMSF and 1 μg/ml aprotonin, leupeptin, and pepstatin. Cells were lysed in TNEN buffer containing 1 mM PMSF and 1 μg/ml aprotonin, leupeptin, and pepstatin. The protein concentration was determined by a Bio-Rad assay. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidenedifluoride membranes (Millipore). Antibodies against MKK6 (9264, 1:1000), p-p38 (9211, 1:1000), p38 (9212, 1:1000), p-Erk1/2 (9106, 1:1000), Erk1/2 (9102, 1:1000), cyclin E (4129, 1:1000), p53 (2524, 1:1000), p-S6 (1211, 1:1000), p-p70S6K (9234, 1:1000), p-4E-BP1 (2855, 1:1000), 4E-BP1 (9644, 1:1000), p-mTOR (5536, 1:1000), and mTOR (2983, 1:1000) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies against β-actin (sc81178, 1:1000), p16 (sc1207, 1:1000) and PCNA (sc-56, 1: 1000) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The protein bands were quantitated using the software provided by FluoChem M system (Protein Simple). Uncropped western blot images can be found in Supplementary Fig. 11.

MKK6 knockdown

Silencer pre-designed siRNA targeting mouse MKK6 was purchased from Gene Pharma (74366, 74367, 74368), which were transfected intoTsc1+/+ and Tsc1−/− MEFs following the manufacturer’s protocol. Knockdown efficiency was determined by western blot.

Quantitative PCR

The total RNA was extracted from cells, crypt, or villi tissues with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA was synthesized with 0.5 μg of the total RNA using Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). The detection and quantification of target mRNA were performed with real-time PCR, which was normalized to the levels of β-actin. Real-time PCR was carried out using the Applied Biosystems 7500 system.

The following primers were used in this study: Mapk14 forward primer: 5′-GGCACCTGCCATCAGTAGTT-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CCAGGGCTTCCAGAAGACAG-3′; Mkk6 forward primer: 5′-GGCACCTGCCATCAGTAGTT-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CCAGGGCTTCCAGAAGACAG-3′.

Villi and crypt quantitation

The numbers of villi per view (10 × 10 magnification) were counted double blindly. The height of villi and crypts were measured from the top to the bottom using NIKON-TiuNIS-Elements microscope. Each group has at least three mice, and the results represent the average of five sections per mouse.

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as the mean with the standard error of the mean (±SEM) or as mean with standard deviation (±SD), if replicates are used. The number of samples (n) is indicated in the figure legends. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was applied to determine the significance of the differences between two groups and P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The source data for Figs. 1a–e, g, h, 2a–d, 3a–d, 4a–e, 5a–d, 6a–f, 7a–d and Supplementary Figs. 1a, d, 2a–c, h, 3b, c, 4a, 5b, d, f, g, 6b, c, 7b–d, 8b, 9b, c, 10d, e are provided as a Source Data file. The remaining data are contained within the article, supplementary information, or available from the authors upon request. A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file.

References

Sharpless, N. E. & Sherr, C. J. Forging a signature of in vivo senescence. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 397–408 (2015).

Soenen, S., Rayner, C. K., Jones, K. L. & Horowitz, M. The ageing gastrointestinal tract. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 19, 12–18 (2016).

Clevers, H. & Batlle, E. SnapShot: the intestinal crypt. Cell 152, 1198–1198 (2013).

Barker, N. et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449, 1003–1007 (2007).

Snippert, H. J. et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143, 134–144 (2010).

Lopez-Garcia, C., Klein, A. M., Simons, B. D. & Winton, D. J. Intestinal stem cell replacement follows a pattern of neutral drift. Science 330, 822–825 (2010).

Barker, N. Adult intestinal stem cells: critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 19–33 (2014).

Bruens, L., Ellenbroek, S. I. J., van Rheenen, J. & Snippert, H. J. In vivo imaging reveals existence of crypt fission and fusion in adult mouse intestine. Gastroenterology 153, 674–677 (2017).

Sangiorgi, E. & Capecchi, M. R. Bmi1 is expressed in vivo in intestinal stem cells. Nat. Genet. 40, 915–920 (2008).

Tian, H. et al. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature 478, 255–259 (2011).

Montgomery, R. K. et al. Mouse telomerase reverse transcriptase (mTert) expression marks slowly cycling intestinal stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 179–184 (2011).

Takeda, N. et al. Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science 334, 1420–1424 (2011).

Yousefi, M., Li, L. & Lengner, C. J. Hierarchy and plasticity in the intestinal stem cell compartment. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 753–764 (2017).

Mihaylova, M. M. et al. Fasting activates fatty acid oxidation to enhance intestinal stem cell function during homeostasis and aging. Cell Stem Cell 22, 769–778 (2018).

Nalapareddy, K. et al. Canonical Wnt signaling ameliorates aging of intestinal stem cells. Cell Rep. 18, 2608–2621 (2017).

Hall, M. N. An amazing turn of events. Cell 171, 18–22 (2017).

Johnson, S. C., Rabinovitch, P. S. & Kaeberlein, M. mTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease. Nature 493, 338–345 (2013).

Laplante, M. & Sabatini David, M. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149, 274–293 (2012).

Harrison, D. E. et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 460, 392–395 (2009).

Pan, H. & Finkel, T. Key proteins and pathways that regulate lifespan. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 6452–6460 (2017).

Hay, N. & Sonenberg, N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Gene Dev. 18, 1926–1945 (2004).

Dowling, R. J. et al. mTORC1-mediated cell proliferation, but not cell growth, controlled by the 4E-BPs. Science 328, 1172–1176 (2010).

Schultz, M. B. & Sinclair, D. A. When stem cells grow old: phenotypes and mechanisms of stem cell aging. Development 143, 3–14 (2016).

Saxton, R. A. & Sabatini, D. M. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 169, 361–371 (2017).

Chen, C. et al. TSC–mTOR maintains quiescence and function of hematopoietic stem cells by repressing mitochondrial biogenesis and reactive oxygen species. J. Exp. Med. 205, 2397–2408 (2008).

Liu, L. & Rando, T. A. Manifestations and mechanisms of stem cell aging. J. Cell Biol. 193, 257–266 (2011).

Narita, M. et al. Spatial coupling of mTOR and autophagy augments secretory phenotypes. Science 332, 966–970 (2011).

Shigeyama, Y. et al. Biphasic response of pancreatic beta-cell mass to ablation of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 in mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 2971–2979 (2008).

Baar, M. P. et al. Targeted apoptosis of senescent cells restores tissue homeostasis in response to chemotoxicity and aging. Cell 169, 132–147 e116 (2017).

Bonkowski, M. S. & Sinclair, D. A. Slowing ageing by design: the rise of NAD+ and sirtuin-activating compounds. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 679–690 (2016).

Sampson, L. L., Davis, A. K., Grogg, M. W. & Zheng, Y. mTOR disruption causes intestinal epithelial cell defects and intestinal atrophy postinjury in mice. FASEB J. 30, 1263–1275 (2016).

Guan, Y. et al. Repression of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 inhibits intestinal regeneration in acute inflammatory bowel disease models. J. Immunol. 195, 339–346 (2015).

Ashton, G. H. et al. Focal adhesion kinase is required for intestinal regeneration and tumorigenesis downstream of Wnt/c-Myc signaling. Dev. Cell 19, 259–269 (2010).

Haller, S. et al. mTORC1 activation during repeated regeneration impairs somatic stem cell maintenance. Cell Stem Cell 21, 806–818 (2017).

Richmond, C. A. et al. Dormant intestinal stem cells are regulated by PTEN and nutritional status. Cell Rep. 13, 2403–2411 (2015).

Yousefi, M. et al. Calorie restriction governs intestinal epithelial regeneration through cell-autonomous regulation of mTORC1 in reserve stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 10, 703–711 (2018).

Yilmaz, O. H. et al. mTORC1 in the Paneth cell niche couples intestinal stem-cell function to calorie intake. Nature 486, 490–495 (2012).

Igarashi, M. & Guarente, L. mTORC1 and SIRT1 cooperate to foster expansion of gut adult stem cells during calorie restriction. Cell 166, 436–450 (2016).

Brack, A. S. et al. Increased Wnt signaling during aging alters muscle stem cell fate and increases fibrosis. Science 317, 807–810 (2007).

Tao, S. et al. Wnt activity and basal niche position sensitize intestinal stem and progenitor cells to DNA damage. EMBO J. 34, 624–640 (2015).

el Marjou, F. et al. Tissue-specific and inducible Cre-mediated recombination in the gut epithelium. Genesis 39, 186–193 (2004).

Wagner, E. F. & Nebreda, A. R. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 537–549 (2009).

Thoreen, C. C. et al. A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature 485, 109–113 (2012).

Otsuka, M. et al. Distinct effects of p38alpha deletion in myeloid lineage and gut epithelia in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 138, 1255–1265 (2010).

Rodriguez-Colman, M. J. et al. Interplay between metabolic identities in the intestinal crypt supports stem cell function. Nature 543, 424–427 (2017).

Bernet, J. D. et al. p38 MAPK signaling underlies a cell-autonomous loss of stem cell self-renewal in skeletal muscle of aged mice. Nat. Med. 20, 265–271 (2014).

Lee, C. H. et al. Constitutive mTOR activation in TSC mutants sensitizes cells to energy starvation and genomic damage via p53. EMBO J. 26, 4812–4823 (2007).

Molofsky, A. V. et al. Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature 443, 448–452 (2006).

Wong, E. S. et al. p38MAPK controls expression of multiple cell cycle inhibitors and islet proliferation with advancing age. Dev. Cell 17, 142–149 (2009).

Kua, H. Y. et al. c-Abl promotes osteoblast expansion by differentially regulating canonical and non-canonical BMP pathways and p16INK4a expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 727–737 (2012).

Brack, A. S. & Rando, T. A. Tissue-specific stem cells: lessons from the skeletal muscle satellite cell. Cell Stem Cell 10, 504–514 (2012).

Conboy, I. M., Conboy, M. J. & Rebo, J. Systemic problems: a perspective on stem cell aging and rejuvenation. Aging 7, 754–765 (2015).

Finkel, T. Relief with rapamycin: mTOR inhibition protects against radiation-induced mucositis. Cell Stem Cell 11, 287–288 (2012).

Tamura, A. et al. Loss of claudin-15, but not claudin-2, causes Na+ deficiency and glucose malabsorption in mouse small intestine. Gastroenterology 140, 913–923 (2011).

Chen, T. S., Currier, G. J. & Wabner, C. L. Intestinal transport during the life span of the mouse. J. Gerontol. 45, B129–B133 (1990).

Wang, B. et al. Intestinal phospholipid remodeling is required for dietary-lipid uptake and survival on a high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 23, 492–504 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lina Gao and Haiyang Xie for technical assistance, and Zilong Qiu and Yibin Wang for providing experimental materials. The work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0103602 and 2018YFA0800803), Shanghai Zhangjiang Stem Cell Research Project (ZJ2018-ZD-004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81520108012 and 91542120), and the Schaefer Research Scholarship to B.L.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L., Y.W., R.A.D., H.L., and S.L.H. designed research; D.H., H.W., J.X., X.R., P.P., and Y.R. performed research; H.W., S.L.H., and D.H. analyzed the data; S.L.H., Y.-G.C., Q.Y., H.L., and B.L. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Christopher Lengner, Kevin Myant and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source Data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, D., Wu, H., Xiang, J. et al. Gut stem cell aging is driven by mTORC1 via a p38 MAPK-p53 pathway. Nat Commun 11, 37 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13911-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13911-x

This article is cited by

-

The effects of restraint stress on ceramide metabolism disorders in the rat liver: the role of CerS6 in hepatocyte injury

Lipids in Health and Disease (2024)

-

The secreted protein Amuc_1409 from Akkermansia muciniphila improves gut health through intestinal stem cell regulation

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Age-, sex- and proximal–distal-resolved multi-omics identifies regulators of intestinal aging in non-human primates

Nature Aging (2024)

-

A stromal lineage maintains crypt structure and villus homeostasis in the intestinal stem cell niche

BMC Biology (2023)

-

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase (HMGCR) protects hair cells from cisplatin‐induced ototoxicity in vitro: possible relation to the activities of p38 MAPK signaling pathway

Archives of Toxicology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.