Abstract

Non-valence states in neutral molecules (Rydberg states) have well-established roles and importance in photochemistry, however, considerably less is known about the role of non-valence states in photo-induced processes in anions. Here, femtosecond time-resolved photoelectron imaging is used to show that photoexcitation of the S1(ππ*) state of the methyl ester of deprotonated para-coumaric acid – a model chromophore for photoactive yellow protein (PYP) – leads to a bifurcation of the excited state wavepacket. One part remains on the S1(ππ*) state forming a twisted intermediate, whilst a second part leads to the formation of a non-valence (dipole-bound) state. Both populations eventually decay independently by vibrational autodetachment. Valence-to-non-valence internal conversion has hitherto not been observed in the intramolecular photophysics of an isolated anion, raising questions into how common such processes might be, given that many anionic chromophores have bright valence states near the detachment threshold.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

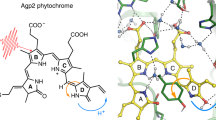

The active site in photoactive proteins and biomolecules is often a simple, well-defined anionic chromophore1,2. For example, one of the most studied biochromophores is that found in the photoactive yellow protein (PYP)3, where an anionic thioester derivative (Fig. 1a) of the E-isomer of para-coumaric acid undergoes an ultrafast E → Z isomerisation that triggers a conformational change in the protein and ultimately leads to a phototaxis response of the host bacterium4,5,6,7,8,9. One of the primary goals of protein photochemistry is to understand the properties of the chromophore and how a protein or condensed phase environment influences the photochemistry. In this context, it is interesting to study biochromophores in isolation, i.e., in the gas-phase, where measurements directly probe the intrinsic light-driven response of the chromophore and also provide theoretically tractable benchmarks10,11,12. Interest in the inherent photochemistry of model PYP chromophores has prompted numerous gas-phase action spectroscopy13,14,15,16,17 and photoelectron spectroscopy studies18,19,20,21, mostly considering deprotonated para-coumaric acid and ester derivatives. However, these studies utilised light sources with nanosecond pulse duration that are not suitable for characterising the ultrafast excited state dynamics that define the photophysics of the PYP chromophore. Furthermore, difficulties in the interpretation of the gas-phase spectra is compounded by the fact that the photoactive S1(ππ*) excited state is close in energy to the electron detachment threshold. The consequence of this near degeneracy is that electron loss by autodetachment can compete with excited state nuclear dynamics (isomerisation). Such a competition was evident in the only previous time-resolved study on an isolated deprotonated para-coumaric acid derivative containing the methyl ketone functional group22. Moreover, because of the proximity of the S1(ππ*) state to the detachment threshold in most PYP chromophore models, the S1(ππ*) state could potentially couple to non-valence states of the anion. Specifically, the neutral molecular core of the model PYP chromophore anions in all studies to date have dipole moments that exceed the ~2.5 D threshold to support a dipole-bound state (DBS)23,24, and therefore will have at least one DBS. While DBSs have been observed in many action and photoelectron spectra by direct excitation23,25,26, internal conversion from a valence-localised state to a DBS has only been observed directly in cluster systems27. In the context of fundamental chemical physics, the lack evidence for the participation of non-valence states in the excited state dynamics of anions is surprising considering that nonadiabatic dynamics between valence and Rydberg states is a common process in the photochemistry of neutral molecules28,29. For PYP chromophore dynamics, the participation of non-valence states has not been considered.

a Structure of the photoactive yellow protein (PYP) chromophore and the E-isomer of pCEs−. b Photodetachment action spectrum of pCEs− (black) and Franck-Condon-Herzberg-Teller simulation of the S1(ππ*) ← S0 transition at 300 K (red). c Photoelectron spectra of pCEs− using hv = 2.79 (red), 3.10 (blue), 3.35 (green), and 3.59 eV (black). The inset in c shows the low-eKE region.

Disentangling environmental perturbations on the excited state dynamics of model PYP chromophores has led to some uncertainty and controversy. There are open questions regarding whether E → Z photoisomerisation actually occurs for many of the model PYP chromophores in the gas-phase and how solvation might influence the photoisomerisation dynamics17. For example, studies on para-coumaric acid derivatives in solution have suggested that the E → Z photoisomerisation efficiency and timescale are modified by a number of factors, including the chromophore’s deprotonation state; functional group substitution on the carbonyl group or torsion-locking the single-bond linking the carboxylic acid tail to the phenyl ring; and properties of the solvent such as polarity and viscosity30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Theoretical studies have confirmed that solvation and substitution on the carboxylate group of para-coumaric acid derivatives modify properties of the S1... (ππ*) potential energy surface, including the nature of twisted intermediates and barriers to reach isomerising conical intersection seams8,9,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46. This state of affairs highlights the need for unambiguous measurements of the gas-phase excited state dynamics on model PYP chromophores.

Here, photodetachment action, photoelectron and time-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy are used to probe the deprotonated methyl ester of para-coumaric acid, pCEs− (Fig. 1a). We uncover a decay mechanism that involves internal conversion from the bright S1(ππ*) valence-localised state to a DBS. Observation of an excited valence to non-valence state internal conversion in the intramolecular photophysics of an unsuspecting chromophore opens the questions about the commonness of such mechanisms in the excited state dynamics of isolated anions. The present results challenge the earlier understanding of this anion in the gas-phase in relation to a model PYP chromophore, by showing there is no internal conversion to the ground electronic state and therefore no concomitant E → Z isomerisation.

Results

Photodetachment action spectroscopy

Figure 1b shows a photodetachment action spectrum for pCEs− recorded over the S1(ππ*) ← S0 transition. The overall shape of the spectrum is in good agreement with earlier work14,17, but additionally shows vibrational structure with ≈90 cm−1 spacing. A Franck-Condon-Herzberg-Teller simulation of the S1(ππ*) ← S0 absorption spectrum at 300 K, which has been translated to agree with an EOM-CC3/aug-cc-pVDZ vertical excitation energy of the S1(ππ*) ← S0 transition at 2.88 eV17, is in good agreement with the experimental vertical excitation energy at 2.88 ± 0.01 eV. The simulation assigns the 0-0 transition at 2.85 ± 0.01 eV and predicts that the absorption spectrum is dominated by a progression involving an in-plane bending mode with a calculated wavenumber of ν3 = 88 cm−1 (see Supplementary Note 1). The red-edge of the photodetachment spectrum is substantially broadened by hot-band transitions because the present experiments were conducted with ions thermalised to ≈300 K.

Single-colour photoelectron spectroscopy

Four representative photoelectron spectra of pCEs− recorded using a tuneable light source (≈6 ns light pulse duration) are shown in Fig. 1c. Extrapolation of the high-electron kinetic energy (eKE) edge of the spectra provided the adiabatic detachment energy (ADE) at 2.83 ± 0.05 eV. The vertical detachment energy (VDE) is 2.87 ± 0.02 eV and refines the value given in an earlier photoelectron spectroscopy study21. The four photoelectron spectra have a low-eKE feature, i.e., eKE < 0.1 eV, see inset in Fig. 1c. In several earlier studies on pCEs− and other PYP chromophore derivatives18,19,20,21, these low-eKE features were assigned to thermionic emission, which involves statistical electron ejection following recovery of the ground electronic state. However, our measurements do not agree with this assignment for several reasons. Firstly, the low-eKE peak has a clear double peak structure. Secondly, the photoelectron angular distribution, quantified with the β2 anisotropy parameter47, of the low-eKE feature have values ranging from +0.1 to +0.2, which implies that some fraction of electron detachment, leading to the low-eKE signal occurs on a timescale that is faster than molecular rotation (picoseconds). Thirdly, delaying the acquisition gate on the electron imaging detector by 50 ns relative to the light pulse showed that all photoelectron signal, including the low-eKE signal, appears on a <50 ns timescale following excitation. All of these observations contradict thermionic emission, which should have a statistical energy distribution, an isotropic angular distribution, and occur on the microseconds to milliseconds timescale. Instead, low-eKE features with the observed attributes can result from autodetachment of valence or non-valence states (picoseconds detachment timescale) that are energetically in close proximity to the detachment threshold, as is the case for pCEs−. Elucidating the origin of these low-eKE electrons requires the excited state dynamics to be probed in real time.

Time-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy

The dynamics of the S1(ππ*) state in pCEs− were investigated using a femtosecond pump-probe strategy. A 2.83 eV pump photon (≈0.02 eV bandwidth) was resonant with red-edge of the action spectrum and a 1.55 eV delayed (Δt) probe photon monitored the evolution of the excited state population. Time-resolved photoelectron spectra, which show the transient changes in eKE with Δt, were determined by subtracting an average of the spectra with Δt ≤ −100 fs (i.e., probe before pump) from all other spectra. Figure 2a shows a series of representative time-resolved photoelectron spectra over the first 3 ps of the dynamics. For three specific delays, we acquired higher single-to-noise spectra and these are shown in Fig. 2b. The negative (bleach) signal for eKE < 0.2 eV has been truncated for clarity; the bleach signal comes about because some of the photoexcited S1(ππ*) population that leads to the low-eKE electrons is photodetached by the probe pulse, leading to a peak at higher kinetic energy. The Δt = 0 ps time-resolved spectrum shows that this feature has a spectral maximum at eKE ≈ 1.4 eV. This feature subsequently broadens and red-shifts to a maximum at eKE ≈ 0.75 eV with increasing Δt. The shift is exemplified by the spectra at Δt = 2.5 and 7.5 ps in Fig. 2b. However, the Δt = 2.5 ps time-resolved spectrum has an additional sharp feature at eKE ≈ 1.53 eV that differs in appearance from Δt = 0 ps spectrum. The Δt = 2.5 ps velocity-map image (from which the time-resolved spectrum is derived) is shown as an inset in Fig. 2b. The photoelectron image shows that the detachment signal leading to the sharp feature is anisotropic, peaking along the probe laser polarisation axis (β2 ≈ +1), which suggests p-wave photodetachment induced by the probe47. A sharp pump-probe feature that peaks near the detachment photon energy with p-wave character is consistent with detachment from a non-valence state of the anion27,48. The sharp peak is evident in the Δt = 0.3–3.0 ps time-resolved spectra.

a Waterfall plot of the time-resolved spectra over the first 3 ps, in 0.5 ps increments. Grey shading highlights evolution of the dipole-bound state. b Example time-resolved spectra taken with higher signal-to-noise than a. The Δt = 2.5 ps spectrum illustrates the sharp, high-eKE feature associated with the DBS. The corresponding velocity-map is shown in the inset, with ε indicating the femtosecond pump and probe pulse electric field polarisation. c Total time-resolved signal with Δt and kinetic model fit, τ1 = 0.6 ± 0.1 ps, τ2 = 2.8 ± 0.7 ps, and τ3 = 45 ± 4 ps. d Average time-resolved electron kinetic energy with Δt, which is best fit with two lifetimes (black trace), τ1′ ≈ τ1 and, τ2′ = 4.7 ± 0.5 ps ≈ τ2 + 1.4 ps, with 1.4 ps being the Δt for maximal DBS signal. The grey trace is a single-exponential fit, which is visually poorer.

The integrated time-resolved photoelectron signal for eKE > 0.2 eV is shown in Fig. 2c and suggests at least two components: a fast decay on the sub-picosecond timescale and a slower decay over tens of picoseconds. The integrated signal fits well to a kinetic model in which an initial excited state decays with a lifetime of τ1 = 0.6 ± 0.1 ps (fast evolution away from the initial broad high-eKE signal) into two intermediate states that separately decay with lifetimes τ2 = 2.8 ± 0.7 ps (decay of the sharp-eKE feature at eKE ≈ 1.53 eV) and τ3 = 45 ± 4 ps (decay of the time-resolved signal peaking around eKE ≈ 0.75 eV). The spectrum associated with lifetime τ3 is represented by the time-resolved spectrum at Δt = 7.5 ps in Fig. 2b, which decays with essentially no further change in its spectral distribution. The time-resolved depletion signal, i.e., eKE < 0.2 eV, returns to the zero level at long Δt. This confirms that all photoelectron signal contributing to the pump-only background spectrum (or single-colour spectra in Fig. 1c) has occurred on the sub-200 ps timescale. Unfortunately, no meaningful analysis could be performed on the depletion signal due to poor signal to noise (small difference signal on a large background), although the recovery kinetics appear to be consistent with the overall decay of τ3.

Further insight into the nuclear relaxation dynamics can be gained through the average kinetic energy, <eKE> , of the time-resolved signal (excluding signal for eKE < 0.2 eV) as a function of Δt (Fig. 2d). The <eKE> data shows a rapid shift towards lower values with Δt, asymptoting to <eKE> = 0.75 eV after ~8 ps, consistent with the time-resolved spectrum at Δt = 7.5 ps (Fig. 2b). The <eKE> data fit well to a bi-exponential model with τ1′ ≈ 0.6 ps and τ2′ = 4.7 ± 0.5 ps (Fig. 2d). A single exponential with lifetime of 2.6 ± 0.2 ps provides a visibly poorer fit. The lifetimes τ1′ and τ2′ can be correlated with the lifetimes in the population dynamics from the kinetic model. Specifically, τ1′ ≈ τ1 and τ2′ ≈ τ2 + 1.4 ps, where 1.4 ps is the Δt at which the sharp feature at eKE ≈ 1.53 eV attributed to detachment from the non-valence state has reached its maximal contribution to the overall signal in the time-resolved spectra (Fig. 2c).

Discussion

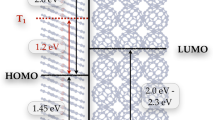

The time-resolved results for pCEs− can be interpreted according to the model presented in Fig. 3a–c. For Δt ≈ 0, the broad, high-eKE time-resolved spectrum (Fig. 2a, b) is due to the probe pulse sampling the S1(ππ*) excited state in the Franck-Condon region of the anion (Fig. 3a). Over the ensuing ≈ 600 fs (τ1 = 0.6 ± 0.1 ps), the time-resolved eKE distribution shifts to lower <eKE> and signal from the non-valence state becomes evident, reaching maximum signal level at Δt ≈ 1.4 ps (Fig. 3b). The time-resolved dynamics associated with the τ1 lifetime involve substantial changes in <eKE> (Fig. 2d), reflecting nuclear relaxation away from the Franck-Condon geometry. A non-valence state is populated along this trajectory, facilitated through a nonadiabatic transition. This state has a lifetime of τ2 = 2.8 ± 0.7 ps and an average binding energy of eBE = hv − eKE ≈ 20 meV. Concomitant with appearance of the non-valence state is the appearance of time-resolved signal with a spectral maximum at < eKE > ≈ 0.75 eV. The disappearance of the time-resolved feature associated with the non-valence state roughly agrees with τ2′ = 4.7 ± 0.5 ps ≈ τ2 + 1.4 ps, indicating that the second time component in the <eKE> fit in Fig. 2d is strongly influenced by loss of the non-valence state population. Indeed, if the <eKE> data is analysed over the 0.2 < eKE < 1.3 eV window, i.e., excluding the signal associated with the non-valence state, the integral can be well fit with a single exponential having a lifetime within the uncertainty of τ1′ ≈ τ1 = 0.6 ± 0.1 ps.

a At Δt ≈ 0, S1(ππ*) population leads to a broad, high-eKE distribution. b Rapid nuclear motion away from the Franck-Condon geometry to a twisted intermediate (τ1 = 0.6 ± 0.1 ps) gives rise to the broad signal peaking around eKE ≈ 0.75 eV. Concurrently, there is internal conversion to a DBS, leading to the sharp eKE signal at eKE ≈ hνprobe. c DBS and twisted intermediate populations decay through vibrational autodetachment with lifetimes τ2 = 2.8 ± 0.7 and τ3 = 45 ± 4 ps, respectively. d CCSD natural orbitals for the S1(ππ*) state and DBS at the initial anion geometry (80% isodensity surface).

The fraction of excited state population that remains in the S1(ππ*) state, which is shown by the Δt = 7.5 ps spectrum in Fig. 2b, decays with a lifetime of τ3 = 45 ± 4 ps. The broad spectral shape and the maximum eKE of this time-resolved feature indicates a valence state with electron-binding energy, eBE = 1.55 – 0.75 eV ≈ 0.8 eV, consistent with detachment from the valence-localised S1(ππ*) state along some nuclear displacement away from the Franck-Condon region. The relatively long lifetime of this time-resolved signal combined with the absence of spectral evolution suggests that the S1(ππ*) population becomes trapped in a potential energy minimum that is presumably associated with a twisted intermediate (phenyl group and alkene tail twisted by 90°) as predicted by theory8,9. In principle, this signal could also arise from the lowest triplet state of the anion. However, the triplet state has not been invoked in previous experimental or computational work and would not be consistent with the observed photoisomerisation of the chromophore in PYP or coumaric acid anions in solution. The twisted intermediate decays through vibrational autodetachment since the time-resolved measurements show recovery of the depletion signal and there was no evidence for thermionic emission in the single-colour spectra. Our calculations on the twisted intermediate predict that it lies vertically ≈0.8 eV below the detachment threshold, in excellent agreement with the experimental data.

The time-resolved signal associated with non-valence state in pCEs− is assigned to a DBS since the neutral core of pCEs has μ = 3.2 or 3.7 D at the anion or neutral equilibrium geometries, respectively, which satisfies the μ > 2.5 D condition to support a DBS23,24. Excited state calculations as part of the current work characterised a DBS with binding energy of 4 and 8 meV at the anion and neutral equilibrium geometries, respectively. Although these binding energies are lower than the average experimental value of ≈20 meV, pCEs− was initially thermalised to 300 K and will exist in several conformations with each possessing a different dipole moment of the neutral core. The orbital associated with the DBS at the anion equilibrium geometry is shown in Fig. 3d.

The model used to fit the integrated time-resolved signal for pCEs− in Fig. 2c assumes that the DBS decays through autodetachment with a lifetime of τ2 = 2.8 ± 0.7 ps, i.e., the DBS population does not convert back to the valence-localised state. Further evidence for autodetachment from the DBS can be seen in the single-colour spectra (Fig. 1c), which show that the low-eKE signal has a double peak structure. Structured, low-eKE features in photoelectron spectra have been previously observed in the vibrational autodetachment dynamics from non-valence states in cluster systems that were initially thermalised to room temperature27,48, with the spectral structure attributed to specific vibrational modes that lead to a substantial change in dipole moment of the neutral core and “shake off” the loosely bound non-valence electron49. The timescale for vibrational autodetachment from the DBS in the earlier study was ≈2 ps, which is in line with the τ2 = 2.8 ± 0.7 ps lifetime observed for pCEs−. The time-resolved data show that the DBS feature has disappeared after several picoseconds, for example see the Δt = 7.5 ps time-resolved spectrum in Fig. 2b, but the spectra still show photodepletion signal in the low-eKE region. Since the photodepletion signal recovers to zero at long Δt, we conclude that excited state population in the twisted intermediate geometry also leads to low-eKE electrons through vibrational autodetachment. In principle, vibrational autodetachment from the twisted intermediate could be mode-specific, leading to a structured low-eKE feature, although the time-resolved data associated with the low-eKE photodepletion signal was too noisy to determine the origin of the low-eKE structure in the single-colour spectra (Fig. 1c).

It is worth noting that even though the time-resolved images and spectra clearly show formation of a DBS, we do not know the branching ratio associated with formation of the DBS and the nuclear dynamics leading to the twisted intermediate because the relative photodetachment cross sections (with probe pulse) are not known. Intuitively we expect the photodetachment cross section for the DBS to be large. Johnson and coworkers50 proposed that the photodetachment cross section depends on the detachment wavelength and maximises when the de Broglie wavelength (λdB) of the outgoing photoelectron is similar to spatial extent of the DBS orbital. At the probe energy of 1.55 eV, λdB = 9.9 Å, which is comparable to the radius of the 80% isodensity surface at ~12 Å for the DBS orbital shown in Fig. 3d.

Internal conversion between the S1(ππ*) state and a DBS requires vibrational motion that induces a nonadiabatic coupling between the two states. The prototypical example, albeit for the ground valence state, is the nitromethane anion in which the nitro group is planar for the DBS but tilted for the valence ground state51. This tilting distortion induces a curve crossing between the two states52. The reverse process, internal conversion from a DBS to a valence state, has been observed in several cluster systems, including I−·X clusters, where X has included (H2O)n or small organic species53,54,55,56. In the case of I−·nucleobase clusters, theory suggested that ring distortion vibrations were responsible for the non-valence-to-valence coupling57. Similar stretching and wagging vibrations were proposed to explain to the valence-to-non-valence internal conversion dynamics characterised in an anionic quinone cluster system27. In a similar vein to these earlier studies, two possible coupling pathways between the S1(ππ*) state and the DBS in pCEs− determined from potential energy surface calculations are shown in Fig. 4. The first pathway (Fig. 4a) is associated with motion along the principal Franck-Condon active vibrational mode, ν3, and indicates a crossing between the S1(ππ*) state and DBS potential energy surfaces roughly halfway along the displacement coordinate in one direction. A second possible pathway (Fig. 4b) involves torsion of the single-bond connecting the phenoxide to the alkene-ester tail, which was identified as principal nuclear displacement required to reach the twisted intermediate from excited state molecular dynamics simulations on the related thioester chromophore of PYP8,9. A rigid potential energy surface scan about dihedral angle θ, suggests that at θ ≈ 52° there is a barrier on the potential energy surface for the S1(ππ*) valence-localised state of ≈0.4 eV (likely lower in a relaxed potential energy surface scan), and a curve crossing with the DBS at θ ≈ 55°. Presumably, there are further coupling pathways along different nuclear displacement coordinates. Excited state molecular dynamics simulations with provision to describe the DBS are needed to identify the active coupling pathways.

The potential energy surfaces are represented by a black line for the ground state, a red line for the S1(ππ*) valence-localised state, and a blue line for the dipole-bound state (DBS), respectively. a Potential energy surface calculation for motion along the principal Franck-Condon active vibration, ν3, with displacement vectors shown on the molecular structure in the inset. 0 corresponds to the initial anion geometry, −1 and 1 correspond to turning points for the ground vibrational level. b Potential energy surface calculation for rigid torsion scan about the single-bond connecting the phenyl and alkene tail by angle θ, as shown inset, with 0° corresponding to the initial anion geometry and 55° to a crossing of valence and non-valence surfaces. Note, the calculated S1(ππ*) vertical excitation energy and VDE (not shown) at the anion equilibrium geometry are both ≈ 0.1 eV lower than experiment.

The excited state dynamics for pCEs− can be compared with those measured for the deprotonated methyl ketone derivative excited at 3.10 eV (400 nm)22. The interpretation of those time-resolved dynamics was that most of the photoexcited population evolved to a twisted intermediate, which then internally converts to the ground electronic state with some fraction undergoing isomerisation by passage through a conical intersection58. However, because the deprotonated methyl ketone study utilised a magnetic bottle analyser, the experiment was unable to reliably accumulate very low-eKE signal and, hence, provide conclusive evidence for the dynamics associated with that signal. The excited state lifetimes were 1 and 52 ps, which are comparable to those for pCEs− (τ1 = 0.6 ± 0.1 ps and τ3 = 45 ± 4 ps), and were similarly assigned to nuclear relaxation away from the Franck-Condon geometry to form a twisted intermediate and its subsequent decay8,9. For pCEs−, the lack of ground state recovery, implies there is no E → Z photoisomerisation by passage through a conical intersection. This conclusion is consistent with recent ion mobility mass spectrometry measurements, which found no evidence for E → Z isomerisation for photon energies resonant with the S1(ππ*) ← S0 transition17. The striking disparity in ground state recovery dynamics between pCEs− and the methyl ketone derivative is presumably linked with substantial differences in potential energy surface topologies associated with isomerising conical intersections8,40,42 for which the isolated chromophores present ideal theoretically tractable benchmarks.

In the context of photoactive yellow protein, the lack of ground state recovery dynamics for isolated pCEs− differs from that for the thioester chromophore in the protein, whereby ground state recovery with concomitant E → Z isomerisation is the key actinic step in the protein’s photocycle. Assuming pCEs− behaves similarly to the isolated thioester derivative, the difference between the photo-induced dynamics in vacuo and in the protein implies that protein side group interactions within the chromophore-binding pocket are crucial for facilitating an ultrafast photoisomerisation of the chromophore.

Finally, we briefly consider the DBS of the chromophore anion in the context of the PYP protein. As the DBS is a weakly bound state, it only exists over a narrow energy range just below the detachment threshold. In the condensed phase, the detachment energy of the chromophore increases due to stabilisation of the ground anion state, shifting the DBS energy away from the energy for the S1(ππ*) state and possibly closer to higher-lying valence-localised states (e.g., S2 or S3). The question of whether a DBS exists in a condensed phase environment is contentious and is presumably linked with local density around the chromophore. In a dense environment, the excluded volume would inhibit the existence of a DBS. On the other hand, charge-transfer-to-solvent states that exist near the detachment threshold of several anions in solution can be viewed as a DBS supported by the dipole of the solvent59. In the PYP protein, the chromophore exists in a binding pocket, which has a lower local density compared with solution and could conceivably support a DBS. For example, recent experiments have shown that a DBS can survive in close proximity to molecular fragments60.

There are two key conclusions of the work. Firstly, we have demonstrated the existence of a valence-to-non-valence state internal conversion process in the intramolecular photophysics of a common chromophore anion, which is active on the picosecond timescale. The formation of a dipole-bound state through internal conversion from an excited valence-localised state for an unsuspecting chromophore raises questions into how common this process might be, and also highlights that care must be taken when assigning low-eKE photoelectron features to dynamical processes implied from single-colour photoelectron spectra. Many biochromophore anions possess S1(ππ*) states that extend into the detachment continuum and have large dipole moments for the neutral state. For example, the methyl ketone derivative of pCEs− has μ = 3.4 D for the neutral core of the E-isomer at the anion geometry, which is similar to that for pCEs (μ = 3.2 D), however, there was no evidence for DBS formation in the time-resolved spectra22. Similar situations exist for pHBDI− (μ = 7.5 D for neutral Z-pHBDI) and deprotonated retinoic acid (μ = 18.2 D for neutral all-trans isomer), which are the chromophore in green fluorescent protein and a retinoid molecule, and have action spectra that extend over their detachment thresholds12,61,62. There is no experimental evidence for coupling with non-valence states in these anions.

A second key conclusion is that pCEs− does not isomerise following photoexcitation of the S1(ππ*) state, despite the anion’s structural similarity to the chromophore in photoactive yellow protein. Instead, the excited state decays by vibrational autodetachment. The signature of this in photoelectron spectroscopy is low-energy electron emission, although the corresponding features in photoelectron spectra can be difficult to distinguish from signal associated with ground state thermionic emission. The application of time-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy removes the interpretation ambiguity and provides a direct measurement of the excited state dynamics. The dramatically different dynamics for small chemical changes in the chemical composition of PYP model chromophores indicates the extreme sensitivity of the S1(ππ*) potential energy surface to functional group modification, and means that PYP chromophores are ideal benchmarks for theoretically tractable excited state dynamics simulations in anions.

Methods

Experimental

Experiments were performed using a custom-built photoelectron imaging apparatus63,64,65. Gas-phase pCEs− was produced through electrospray (−5 kV) of a ~1 mM methanolic solution of the sample (99%, Sigma-Aldrich, shielded from light) with a trace of ammonia to aid deprotonation. Electrosprayed anions were transferred via a vacuum transfer capillary into a radio frequency ring-electrode ion trap. The trapped anions were unloaded (10 or 50 Hz) into a colinear time-of-flight optics assembly that accelerated the ions along a 1.3 m flight region toward a continuous-mode penetrating field velocity-mapping assembly66. Laser pulses were timed to interact with the mass-selected ion packet at the centre of the velocity-map imaging stack. Ejected electrons were velocity mapped onto a dual (chevron) multi-channel plate detector, followed by a P43 phosphor screen, which was monitored with a charge-coupled device camera. Velocity-map images were accumulated with a 500 ns multi-channel plate acquisition gate; delay of the gate relative to the laser pulse by 50 ns demonstrated no thermionic emission signal67. Velocity-mapping resolution was ~5% and the electron kinetic energy (eKE) scale was calibrated from the spectrum of I−. Velocity-map images were processed using an antialiasing and polar onion-peeling algorithm68, providing the photoelectron spectra and associated angular distributions in terms of β2 values47.

The photodetachment action spectrum and single-colour photoelectron spectra were recorded using light from a Continuum Horizon optical parametric oscillator pumped with a Continuum Surelite II Nd:YAG laser (~0.5 mJ pulse−1, unfocused).

Femtosecond laser pulses were derived from a Spectra-Physics Ti:sapphire oscillator and regenerative amplifier. The 2.83 eV (438 ± 5 nm, ~20 µJ) pump pulses were produced by fourth-harmonic generation (two successive BBO crystals) of the idler output from an optical parametric amplifier (Light Conversion TOPAS-C). The 1.55 eV (800 nm, ~100 µJ) probe pulse is the fundamental of the laser. Pump and probe pulses were delayed relative to each other (Δt) using a motorised delay line. Both pulses were combined collinearly using a dichroic mirror and were loosely focused into the interaction region using a curved metal mirror. The pump-probe cross correlation was ~70 fs.

Theoretical

Franck-Condon-Herzberg-Teller simulations were performed at 300 K at the ωB97X-D/aug-cc-pVDZ level of theory within the TD-DFT framework using Gaussian 16.B0169,70,71,72. DBS calculations were performed at the EA-EOM-CCSD/GEN (ROHF reference) level of theory73 using CFOUR 2.174. Potential energy surface calculations of the S1(ππ*) state and VDE were performed at the STEOM-DLPNO-CCSD/aug-cc-pVDZ level of theory using ORCA 4.2.075. Molecular basis set GEN is the 6–31 + G* basis set76 with eight additional s, p, and d diffuse functions centred 1 Å beyond the CH3 on the ester functional group, i.e., at the positive end of the electric dipole moment associated with the neutral core. Orbital exponents for the additional diffuse functions followed the recommendations in Skurski et al.77, starting at 0.1 and followed a decreasing geometric progression with factor 3.2. Calculations in which the additional diffuse functions were situated 2 or 3 Å beyond CH3 group or 1 Å between the CH3 group and carbonyl oxygen atom gave no substantial change to the DBS-binding energies. Neither further diffuse functions nor change of the geometric progression factor to 6.4 gave an increased DBS-binding energy.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon request.

References

Brøndsted Nielsen, S. & Wyer, J. A. Photophysics of Ionic Biochromophores. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013).

Henley, A. & Fielding, H. H. Anion photoelectron spectroscopy of protein chromophores. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 38, 1–34 (2019).

Kort, R. et al. Evidence for trans-cis isomerization of the p-coumaric acid chromophore as the photochemical basis of the photocycle of photoactive yellow protein. FEBS Lett. 382, 73–78 (1996).

Meyer, T. E. Isolation and characterization of soluble cytochromes, ferredoxins and other chromophoric proteins from the halophilic phototrophic bacterium Ectothiorhodospira halophila. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 806, 175–183 (1985).

Meyer, T. E., Yakali, E., Cusanovich, M. A. & Tollin, G. Properties of a water-soluble, yellow protein isolated from a halophilic phototrophic bacterium that has photochemical activity analogous to sensory rhodopsin. Biochemistry 26, 418–423 (1987).

Tenboer, J. et al. Time-resolved serial crystallography captures high-resolution intermediates of photoactive yellow protein. Science 346, 1242–1246 (2014).

Pande, K. et al. Femtosecond structural dynamics drives the trans/cis isomerization in photoactive yellow protein. Science 352, 725–729 (2016).

Groenhof, G. et al. Photoactivation of the photoactive yellow protein: Why photon absorption triggers a trans-to-cis Isomerization of the chromophore in the protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 4228–4233 (2004).

Groenhof, G., Schafer, L. V., Boggio-Pasqua, M., Grubmuller, H. & Robb, M. A. Arginine52 controls the photoisomerization process in photoactive yellow protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3250–3251 (2008).

de Vries, M. S. & Hobza, P. Gas-phase spectroscopy of biomolecular building blocks. Annu Rev. Phys. Chem. 58, 585–612 (2007).

Stavros, V. G. & Verlet, J. R. Gas-phase femtosecond particle spectroscopy: A bottom-up approach to nucleotide dynamics. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 67, 211–232 (2016).

Bull, J. N. et al. Ultrafast photoisomerisation of an isolated retinoid. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 10567–10579 (2019).

Nielsen, I. B. et al. Absorption spectra of photoactive yellow protein chromophores in vacuum. Biophys. J. 89, 2597–2604 (2005).

Rocha-Rinza, T. et al. Gas phase absorption studies of photoactive yellow protein chromophore derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 9442–9449 (2009).

Rocha-Rinza, T. et al. Spectroscopic implications of the electron donor-acceptor effect in the photoactive yellow protein chromophore. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 11977–11984 (2010).

Andersen, L. H. et al. A PYP chromophore acts as a ‘photoacid’ in an isolated hydrogen bonded complex. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 9909–9913 (2016).

Bull, J. N., da Silva, G., Scholz, M. S., Carrascosa, E. & Bieske, E. J. Photoinduced intramolecular proton transfer in deprotonated para-coumaric acid. J. Phys. Chem. A 123, 4419–4430 (2019).

Mooney, C. R., Parkes, M. A., Iskra, A. & Fielding, H. H. Controlling radical formation in the photoactive yellow protein chromophore. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 5646–5649 (2015).

Parkes, M. A., Phillips, C., Porter, M. J. & Fielding, H. H. Controlling electron emission from the photoactive yellow protein chromophore by substitution at the coumaric acid group. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 10329–10336 (2016).

Henley, A., Patel, A. M., Parkes, M. A., Anderson, J. C. & Fielding, H. H. Role of photoisomerization on the photodetachment of the photoactive yellow protein chromophore. J. Phys. Chem. A 122, 8222–8228 (2018).

Henley, A. et al. Electronic structure and dynamics of torsion-locked photoactive yellow protein chromophores. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 31572–31580 (2017).

Lee, I. R., Lee, W. & Zewail, A. H. Primary steps of the photoactive yellow protein: Isolated chromophore dynamics and protein directed function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 258–262 (2006).

Jordan, K. D. & Wang, F. Theory of dipole-bound anions. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 54, 367–396 (2003).

Simons, J. Molecular anions. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 6401–6511 (2008).

Jackson, R. L., Hiberty, P. C. & Brauman, J. I. Threshold resonances in the electron photodetachment spectrum of acetaldehyde enolate anion. Evidence for a low-lying, dipole-supported state. J. Chem. Phys. 74, 3705–3712 (1981).

Lykke, K. R., Mead, R. D. & Lineberger, W. C. Observation of dipole-bound states of negative ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 52, 2221–2224 (1984).

Bull, J. N., West, C. W. & Verlet, J. R. R. Ultrafast dynamics of formation and autodetachment of a dipole-bound state in an open-shell π-stacked dimer anion. Chem. Sci. 7, 5352–5361 (2016).

Stebbings, R. F. & Dunning, F. B. Rydberg States of Atoms and Molecules (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

Child, M. S. Theory of Molecular Rydberg States. (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Changenet-Barret, P. et al. Early molecular events in the photoactive yellow protein: Role of the chromophore photophysics. Photochem. Photobio. Sci. 3, 823–829 (2004).

El-Gezawy, H., Rettig, W., Danel, A. & Jonusauskas, G. Probing the photochemical mechanism in photoactive yellow protein. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 18699–18705 (2005).

Espagne, A., Changenet-Barret, P., Plaza, P. & Martin, M. M. Solvent effect on the excited-state dynamics of analogues of the photoactive yellow protein chromophore. J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 3393–3404 (2006).

Espagne, A., Paik, D. H., Changenet-Barret, P., Martin, M. M. & Zewail, A. H. Ultrafast photoisomerization of photoactive yellow protein chromophore analogues in solution: Influence of the protonation state. Chem. Phys. Chem. 7, 1717–1726 (2006).

Stahl, A. D. et al. On the involvement of single-bond rotation in the primary photochemistry of photoactive yellow protein. Biophys. J. 101, 1184–1192 (2011).

Kuramochi, H., Takeuchi, S. & Tahara, T. Ultrafast structural evolution of photoactive yellow protein chromophore revealed by ultraviolet resonance femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 2025–2029 (2012).

Changenet-Barret, P., Lacombat, F. & Plaza, P. Reaction-coordinate tracking in the excited-state deactivation of the photoactive yellow protein chromophore in solution. J. Photochem. Photobio. A: Chem. 234, 171–180 (2012).

Gromov, E. V., Burghardt, I., Hynes, J. T., Köppel, H. & Cederbaum, L. S. Electronic structure of the photoactive yellow protein chromophore: Ab initio study of the low-lying excited singlet states. J. Photochem. Photobio. A: Chem. 190, 241–257 (2007).

Ko, C., Virshup, A. M. & Martínez, T. J. Electrostatic control of photoisomerization in the photoactive yellow protein chromophore: ab initio multiple spawning dynamics. Chem. Phys. Lett. 460, 272–277 (2008).

Virshup, A. M. et al. Photodynamics in complex environments: ab initio multiple spawning quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 3280–3291 (2009).

Boggio-Pasqua, M. & Groenhof, G. Controlling the photoreactivity of the photoactive yellow protein chromophore by substituting at the p-coumaric acid group. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 7021–7028 (2011).

Isborn, C. M., Gotz, A. W., Clark, M. A., Walker, R. C. & Martinez, T. J. Electronic absorption spectra from MM and ab initio QM/MM molecular dynamics: environmental effects on the absorption spectrum of photoactive yellow protein. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 5092–5106 (2012).

Garcia-Prieto, F. F. et al. Substituent and solvent effects on the UV-vis absorption spectrum of the photoactive yellow protein chromophore. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 5504–5514 (2015).

Garcia-Prieto, F. F., Munoz-Losa, A., Luz Sanchez, M., Elena Martin, M. & Aguilar, M. A. Solvent effects on de-excitation channels in the p-coumaric acid methyl ester anion, an analogue of the photoactive yellow protein (PYP) chromophore. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 27476–27485 (2016).

Garcia-Prieto, F. F. et al. QM/MM study of substituent and solvent effects on the excited state dynamics of the photoactive yellow protein chromophore. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 737–748 (2017).

Boggio-Pasqua, M., Robb, M. A. & Groenhof, G. Hydrogen bonding controls excited-state decay of the photoactive yellow protein chromophore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 13580–13581 (2009).

Boggio-Pasqua, M., Burmeister, C. F., Robb, M. A. & Groenhof, G. Photochemical reactions in biological systems: Probing the effect of the environment by means of hybrid quantum chemistry/molecular mechanics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 7912–7928 (2012).

Zare, R. N. Photoejection dynamics. Mol. Photochem. 4, 1–37 (1972).

Bull, J. N. & Verlet, J. R. R. Observation and ultrafast dynamics of a nonvalence correlation-bound state of an anion. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603106 (2017).

Simons, J. Propensity rules for vibration-induced electron detachment of anions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 3971–3976 (1981).

Bailey, C. G., Dessent, C. E. H., Johnson, M. A. & Bowen, K. H. Vibronic effects in the photon energy-dependent photoelectron spectra of the CH3CN− dipole-bound anion. J. Chem. Phys. 104, 6976–6983 (1996).

Bull, J. N., Maclagan, R. G. & Harland, P. W. On the electron affinity of nitromethane (CH3NO2). J. Phys. Chem. A 114, 3622–3629 (2010).

Gutsev, G. L. & Bartlett, R. J. A theoretical study of the valence- and dipole-bound states of the nitromethane anion. J. Chem. Phys. 105, 8785–8792 (1996).

Lehr, L., Zanni, M. T., Frischkorn, C., Weinkauf, R. & Neumark, D. M. Electron solvation in finite systems: Femtosecond dynamics of iodide. (Water)n anion clusters. Science 284, 635–638 (1999).

Yandell, M. A., King, S. B. & Neumark, D. M. Decay dynamics of nascent acetonitrile and nitromethane dipole-bound anions produced by intracluster charge-transfer. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 184317 (2014).

Kunin, A. & Neumark, D. M. Time-resolved radiation chemistry: Femtosecond photoelectron spectroscopy of electron attachment and photodissociation dynamics in iodide-nucleobase clusters. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 7239–7255 (2019).

Rogers, J. P., Anstoter, C. S. & Verlet, J. R. R. Ultrafast dynamics of low-energy electron attachment via a non-valence correlation-bound state. Nat. Chem. 10, 341–346 (2018).

Stephansen, A. B. et al. Dynamics of dipole- and valence bound anions in iodide-adenine binary complexes: a time-resolved photoelectron imaging and quantum mechanical investigation. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 104308 (2015).

Levine, B. G. & Martinez, T. J. Isomerization through conical intersections. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 58, 613–634 (2007).

Blandamer, M. J. & Fox, M. F. Theory and applications of charge-transfer-to-solvent spectra. Chem. Rev. 70, 59–93 (1970).

Castellani, M. E., Anstöter, C. S. & Verlet, J. R. R. On the stability of a dipole-bound state in the presence of a molecule. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 24286–24290 (2019).

Nielsen, S. B. et al. Absorption spectrum of the green fluorescent protein chromophore anion in vacuo. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 228102 (2001).

Mooney, C. R. S. et al. Taking the green fluorescence out of the protein: dynamics of the isolated GFP chromophore anion. Chem. Sci. 4, 921–927 (2013).

Roberts, G. M., Lecointre, J., Horke, D. A. & Verlet, J. R. R. Spectroscopy and dynamics of the 7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane radical anion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 6226–6232 (2010).

Stanley, L. H., Anstoter, C. S. & Verlet, J. R. R. Resonances of the anthracenyl anion probed by frequency-resolved photoelectron imaging of collision-induced dissociated anthracene carboxylic acid. Chem. Sci. 8, 3054–3061 (2017).

Bull, J. N., West, C. W. & Verlet, J. R. R. On the formation of anions: Frequency-, angle-, and time-resolved photoelectron imaging of the menadione radical anion. Chem. Sci. 6, 1578–1589 (2015).

Horke, D. A., Roberts, G. M., Lecointre, J. & Verlet, J. R. R. Velocity-map imaging at low extraction fields. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 063101 (2012).

Bull, J. N., West, C. W. & Verlet, J. R. R. Internal conversion outcompetes autodetachment from resonances in the deprotonated tetracene anion continuum. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 32464–32471 (2015).

Roberts, G. M., Nixon, J. L., Lecointre, J., Wrede, E. & Verlet, J. R. R. Toward real-time charged-particle image reconstruction using polar onion-peeling. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 80, 053104 (2009).

Santoro, F., Lami, A., Improta, R., Bloino, J. & Barone, V. Effective method for the computation of optical spectra of large molecules at finite temperature including the Duschinsky and Herzberg-Teller effect: the Qx band of porphyrin as a case study. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 224311 (2008).

Chai, J. D. & Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom-atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 6615–6620 (2008).

Dunning, T. H. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 90, 1007–1023 (1989).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16 Revision B.01. (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016).

Nooijen, M. & Bartlett, R. J. Equation of motion coupled cluster method for electron attachment. J. Chem. Phys. 102, 3629–3647 (1995).

CFOUR, Coupled-Cluster techniques for Computational Chemistry, A Quantum-chemical Program Package by Stanton, J. F. et al. with contributions from A. A. Auer, A. A. et al. and the integral packages MOLECULE (Almlöf, J. and Taylor, P. R.), PROPS (Taylor, P. R.), ABACUS (Helgaker, T., Aa. Jensen, H. J., Jørgensen, P. & Olsen, J.) and ECP routines by Mitin, A. V. and van Wüllen, C. For the current version, see http://www.cfour.de.

Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIRES: Comp. Mol. Sci. 2, 73–78 (2012).

Ditchfield, R., Hehre, W. J. & Pople, J. A. Self-consistent molecular-orbital methods. IX. An extended Gaussian-type basis for molecular-orbital studies of organic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 54, 724–728 (1971).

Skurski, P., Gutowski, M. & Simons, J. How to choose a one-electron basis set to reliably describe a dipole-bound anion. Int J. Quant. Chem. 80, 1024–1038 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a University of East Anglia start-up allowance (JNB), the European Research Council, grant 306536 (CAS, JRRV) and the EPSRC grant EP/D073472/1 (JRRV).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.R.R.V. and J.N.B. designed and conceived the experiments. J.N.B. and C.S.A. conducted the experiments. J.N.B. conducted calculations and the analysis of the dynamics. J.N.B. and J.R.R.V. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Martial Boggio-Pasqua, Eduardo Carrascosa and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bull, J.N., Anstöter, C.S. & Verlet, J.R.R. Ultrafast valence to non-valence excited state dynamics in a common anionic chromophore. Nat Commun 10, 5820 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13819-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13819-6

This article is cited by

-

A trajectory surface hopping study of the vibration-induced autodetachment dynamics of the 1-nitropropane anion

Theoretical Chemistry Accounts (2023)

-

Geometric and electronic structure probed along the isomerisation coordinate of a photoactive yellow protein chromophore

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.