Abstract

Plate tectonics and mantle plumes are two of the most fundamental solid-Earth processes that have operated through much of Earth history. For the past 300 million years, mantle plumes are known to derive mostly from two large low shear velocity provinces (LLSVPs) above the core-mantle boundary, referred to as the African and Pacific superplumes, but their possible connection with plate tectonics is debated. Here, we demonstrate that transition elements (Ni, Cr, and Fe/Mn) in basaltic rocks can be used to trace plume-related magmatism through Earth history. Our analysis indicates the presence of a direct relationship between the intensity of plume magmatism and the supercontinent cycle, suggesting a possible dynamic coupling between supercontinent and superplume events. In addition, our analysis shows a consistent sudden drop in MgO, Ni and Cr at ~3.2–3.0 billion years ago, possibly indicating an abrupt change in mantle temperature at the start of global plate tectonics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

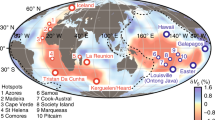

The plate tectonic theory developed last century works well on Earth’s outer shell, but how this system interacts with mantle plumes, and if they are part of the same geodynamic system in Earth history, remains unclear. Seismic studies have revealed that Earth’s present-day lower mantle is dominated by two antipodal large low shear velocity provinces (LLSVPs), also known as the African and Pacific superplumes, surrounded by high-velocity zones with subducted cold slabs1. It has been further shown that almost all known mantle plumes since ~300 million years ago (Ma) were generated atop or near the edges of these two LLSVPs2,3. On the other hand, the assembly and breakup of supercontinents are controlled by global-scale mantle dynamics and constant feedback between surface and deep mantle processes4. It has been further established that the African LLSVP (whether or not in its present geometry) was located underneath the supercontinent Pangaea ca. 300 Ma5, and that there was a close link between mantle plumes and Pangaea breakup6. However, how long the LLSVPs have been present, how such LLSVPs interact with tectonic plates in Earth history, and whether they are fixed in the deep mantle1,3,7 or part of a dynamic system associated with the supercontinent cycle since at least the Proterozoic8,9,10,11, remain topics of debate. Tracing mantle plume signatures throughout Earth history is fundamental for answering those questions and testing the stable vs. dynamic/cyclic nature of the LLSVPs, and thus achieving a better understanding of the coupling between Earth’s mantle dynamics and plate tectonics.

Basaltic magmatism can be used to probe mantle evolution throughout Earth history12,13. Such mafic magmatism is mostly generated in three main tectonic settings: mantle plume, mid-ocean ridge, and subduction zone (arc). Geochemical and isotopic characteristics of basalts generated in such settings can identify, or “fingerprint”, the processes and sources of magma generation from different parts of the mantle12. Where mid-ocean ridge basalts (MORBs) and arc-related basalts (ARBs) represent melts generated within the sub-oceanic and sub-arc upper mantle, respectively14,15,16,17, plume basalts, such as oceanic island basalts (OIBs), oceanic flood basalts, and continental large igneous provinces (LIPs) commonly involve deeper mantle processes in which LLSVPs may provide both additional heat and some melt materials12,18,19.

Incompatible trace elements, particularly high-field strength elements (HFSEs) and their ratios, are widely used to monitor and discriminate between mantle domains and tectonic environments for basaltic magmatism, and to trace plume signatures15,16,20. However, as HFSEs can be affected by various processes, such as source contamination, magma mixing, crust-magma interaction, and high-grade metamorphism, the validity of using such an approach to discriminate tectonic settings has been questioned21,22. One reason for this is that the low partition coefficients (<1) of HFSEs with Fe–Mg silicate minerals and spinel12,23—the main components of basaltic magmatism—make HFSEs easily redistributed by the aforementioned processes. On the other hand, transition elements have partition coefficients with Fe–Mg silicate minerals and spinel >1, making them highly insensitive to post-formation processes23,24,25. The behavior of the first-row transition elements, especially Ni and Cr (highly compatible) and their ratios to less compatible ones (Co and Zn), is strongly melt-composition dependent12,23 and highly sensitive to the earliest magmatic differentiation stages26. Thus, the abundance of Ni and Cr may track the nature of basaltic magmatism generated from different parts of the mantle.

Here, we demonstrate that Ni and Cr contents constitute an excellent tool for discriminating between plume- and non-plume-related (MORBs and ARBs) magmatism. In addition, by using the statistical bootstrapping method on the global geochemical database of basaltic rocks, we show that the transition elements (Ni, Cr, and Fe/Mn, i.e., plume intensity) exhibit systematic short-term variations that coincide with the supercontinent cycle, which could potentially suggest a dynamic coupling between first-order mantle structure (e.g., LLSVPs) and plate tectonics.

Results

Ni and Cr as tracers for mantle plume products

Magnesium content and its ratio to other elements (i.e., Mg/Fe) are commonly used as tracers for the differentiation of silicate rocks and an indicator for mantle temperature14,15,27. Geochemical modeling using MgO content revealed the ambient mantle temperature below the ridges and sub-arc to be ~1350 °C, but typically thermal anomalies of ~200–300 °C over the ambient mantle temperature are expected for mantle plumes14,15,27,28,29. As transition elements (i.e., Ni and Cr) behave similarly to Mg during mantle melting, Ni and Cr should also be highly sensitive to mantle temperature, and can thus be used for distinguishing between plume and non-plume mantle melt products. To illustrate this point, we compare the global databases (see the Methods section and Supplementary Data 1) of mantle melts with a range of MgO content and potential mantle temperature of melting14, such as komatiites (>18 wt% MgO and T ~1600 °C), picrites (>12 wt % MgO and T ~1500 °C; from OIBs and LIPs), and normal basalts (<12 wt % MgO and T ~1350 °C; from present-day MORBs and ARBs)14,15,30,31 to their corresponding Ni, Cr, Ni/Co, and Cr/Zn contents and ratios, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). Strikingly, those transition elements have a positive correlation with MgO content and can, therefore, be used for discriminating komatiites and picrites (representing plume magmatism) from normal basalts (representing non-plume magmatism). Plume magmatism is characterized by Ni > 200 ppm, Cr > 500 ppm, and Ni/Co and Cr/Zn both >8 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

To further verify the inferred plume characteristics, we produced covariation plots for Ni and Cr, and Mg# (100 × MgO/(MgO + FeOT) vs. Ni and Cr of basalt datasets (45 wt% <SiO2 <53 wt% and Na2O + K2O < 5 wt%)32 from Cenozoic OIBs and LIPs and present-day MORBs and ARBs (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 1). Much like komatiites and picrites, 70% of the plume basalt (PB) datasets have Ni >150 ppm and Cr > 300 ppm, whereas non-plume magmatism (MORBs and ARBs) are mostly below these limits. Thus, we argue that high Ni and Cr contents in basalts implies a plume signature. In addition, consistent with previous studies of some OIBs from the Pacific superplume33,34, we found that plume basalts (OIBs and LIPs) generally have Fe/Mn > 65, clearly higher than that of MORBs and ARBs (Fig. 2).

Density plot of Ni, Cr, and Mg# for different basaltic magmatism types. Panels a, b, and c are density plots of plume-related basalts (PRB) for Ni (ppm) vs. Cr (ppm) and Mg# (100 × MgO/ (MgO + FeOT) vs. Ni (ppm) and Cr (ppm), respectively. Panels d–f are density plots for mid-ocean ridge basalts (MORB) and g–i panels are for arc-related basalts. Data sources: Georoc and EarthChem (see Methods and Supplementary Data 1). Black contours define the data density values from high density (blue) to low density (red). The white contour represents 70% of the PRB data

Density plot of Fe/Mn vs. Mg# for different basaltic types. a Plume-related basalts (PRB); b mid-ocean ridge basalts (MORB); c arc-related basalts. Data sources: Georoc and EarthChem (see Methods). Black contours define the data density values from high density (blue) to low density (red). The white contour represents 70% of the PRB data

Based on these observations, we use MgO, Cr, and Ni contents to filter data from ∼41,000 samples (Supplementary Figs. 3, 4 and Supplementary Data 2) in the global databases (Georoc and EarthChem repositories) in order to trace plume signature throughout Earth history (see the Methods section). The bootstrapped data (see Methods) reveal a first-order decrease in MgO, Cr, and Ni content in basalts since the Archean eon29,35 (Fig. 3), plus second-order variations within the Proterozoic and the Phanerozoic (Fig. 4). To further interrogate the second-order variations, we detrended the linear secular decreases in each dataset (Fig. 4a–c; Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1).

Time evolution of global mean MgO, Ni, and Cr contents after a bootstrap resampling of the selected basaltic database. The blue dashed lines in a–c are regression lines for data between 0 to 3.0 Ga that reveal first-order secular decreases. Error bars in a–c show 2 s.e.m. (standard error of the mean) uncertainties. d Secular cooling of Earth’s mantle based on non-arc basalts28 and thermal modeling43. Urey ratios (Ur) are shown: 0.08 (upper curve), 0.23 (middle curve), and 0.38 (lower curve)

Variability of global mean MgO, Ni, and Cr in basalts after detrending the linear secular decreases. The linear secular decreases used are those shown with blue dash lines in Fig. 3. The plot shows major positive peaks at ~2.8–2.3 Ga, ~1.6–1.3 Ga, ~1.0–0.7 Ga, and ~0.3–0.0 Ga, broadly consistent with the tenures and break-up times of post-2 Ga supercontinents. The durations of supercontinent tenure53,54 are marked with solid green vertical bars, e.g., at ca. 320–170 Ma (Pangea), 900–700 Ma (Rodinia), 1600–1300 Ma (Nuna), but the occurrence of Kenorland during 2700–2300 Ma is highly uncertain (thus shown in faded green). The assembly and break-up of supercontinents are generally prolonged and multistage processes, which are marked by gradual green shading

Discussion

Time variations in mantle plume intensity

The highly compatible transition elements Ni and Cr and their ratios to less compatible ones (e.g., Ni/Co and Cr/Zn), plus Fe/Mn and the previously widely used MgO, are good discriminants for mantle plume magmatism because they all indicate higher mantle melt temperature. As basaltic magmatism represents the direct melt products of Earth’s mantle, its composition potentially records Earth’s mantle evolution since 4 billion years ago (Ga). Our analysis revealed a first-order decrease in MgO, Ni and Cr since the Archean similar to that shown by Keller and Schoene29,35 (Fig. 3a–c), readily explainable by Earth’s secular cooling (including the lowering of the mantle potential temperature)15,28,29,35.

The second-order variability of MgO, Ni, and Cr, previously largely ignored29,35,36, is more intriguing. The curves consistently show major positive peaks at ~2.8–2.3 Ga, ~1.6–1.3 Ga, ~1.0–0.7 Ga, and ~0.3–0.0 Ga. The most straightforward interpretation of these second-order variations is that they reflect changes in mantle potential temperature/degree of melting (see Fig. 4 of Ref. 29), which may be a consequence of either mantle plumes, or thermal insulation in the upper mantle37, or both. Plumes are possibly a more dominant factor because they allow the higher Ni (>150 ppm) and Cr (>300 ppm) contents of the basalts to be sourced from the fertile lower mantle peridotites (i.e., Ni = 2500–3200 ppm and Cr = 2600–7500 ppm)14,38,39 (Fig. 1a–c) rather than the depleted upper mantle peridotites (i.e., Ni = 1960 ppm and Cr = 2500 ppm)40 (Fig. 1d–f). This interpretation is supported by their anomalously high Fe/Mn of >65 (Fig. 2), a well-accepted characteristic of plume basalts33,34, as well as high abundances of Ni and Cr (Fig. 1).

Implications for mantle dynamics coupled with the supercontinent cycle

Our results show a general temporal consistency between the MgO, Ni, and Cr peaks/anomalies (i.e., plume intensity/activities) and the occurrence of known supercontinents, suggesting a clear positive correlation between mantle plume intensity and supercontinent tenure (Fig. 4). Such results allow us to speculate on the fixed vs. dynamic models for the two LLSVPs in the lower mantle. In the fixed LLSVPs model1,3,7, the LLSVPs are stable features anchored to the core-mantle boundary (CMB) since early Earth. Their positions and shapes would therefore not have been linked to the subduction girdle and thus to plate motion in general8,9,10,11. As such, one would expect the formation of plume basalts to be stochastic in Earth history, implying a semi-uniform occurrence of plume magmatism over geological time, i.e., plume intensity unrelated to the supercontinent cycle. Alternatively, if supercontinents indeed preferentially form on the global subduction girdle (cold downwelling mantle) as suggested by some41, and both the antipodal LLSVPs and the subduction girdle are fixed and long-lived features, then one would expect an anticorrelation between plume intensity and supercontinental tenure (we note that the pre-Cretaceous global plume record is dominated by continental LIPs). In contrast, according to the dynamic LLSVPs model8,9, the formation of antipodal LLSVPs is linked to circum-supercontinent subduction that leads to the formation of the subduction girdle; the subduction girdle subsequently divides the hot and dense lower mantle into the two antipodal LLSVPs8,9. Such a dynamic LLSVP model therefore predicts an increase in the intensity of plume magmatism during the tenure and breakup stage of the supercontinent, and thus a periodicity positively correlated with the supercontinent cycle.

The global plume intensity record we reported here (Fig. 4) is inconsistent with either predictions of the fixed LLSVPs model, i.e., it shows neither a semi-uniform time distribution, nor an anticorrelation with the supercontinent tenure. The observed positive correlation between plume intensity and supercontinent cycle cannot be viewed as mere coincidence. In the absence of viable alternative explanations, we suggest the coupled supercontinent-mantle plume records as evidence supporting the dynamic LLSVP model. Indeed, it would be challenging to keep the LLSVPs fixed to the CMB because a constantly evolving subduction geometry changes the deposition of the subducted slabs above the CMB42.

Furthermore, our analysis shows a consistent sudden drop in MgO, Ni, and Cr at ~3.2–3.0 Ga (Fig. 3a–c), interpreted to indicate an abrupt change in mantle temperature. These results are comparable with the petrological estimation of mantle potential temperature using non-arc basalts28, as well as Earth’s secular cooling predicted by parameterized convection models43 (Fig. 3d). We speculate that this interpreted dramatic drop in mantle temperature may indicate the initiation of global plate tectonics, where the subduction-driven whole-mantle convection enhanced the heat flux out of the core and mantle. The sharp peaks at ca. 3.2 Ga (Fig. 3a–c), also shown in the mantle potential temperature estimations based on non-arc basalts (red dots in Fig. 3d)28, possibly reflect a dramatic build-up in mantle temperature before the initiation of plate tectonics, when there was a lack of a mechanism for efficient heat flux out of the mantle. A ~3.2–3.0 Ga emergence of plate tectonics would be broadly consistent with the sedimentary, igneous, metamorphic, and palaeomagnetic records26,36,44.

To summarize, geochemical tracers for plume basalts (Ni, Cr, and Fe/Mn) indicate the presence of a coupling between global plume intensity and supercontinent cycle. Such results are consistent with the suggested dynamic LLSVP model8,9,10 that links the formation, position, and evolution of LLSVPs with that of supercontinents. Recent numerical modeling45,46,47,48, paleomagnetic49,50, and seismic51,52 work are also in general agreements with the geodynamic LLSVP model.

Methods

Database compilation

We compiled a global database of komatiites (~3000 samples) and picrites (~1650 samples), covering major- and trace elements (particular transition elements such as Ni, Cr, Co, Zn, Cu, and Sc) from the Georoc (http://georoc.mpch-mainz.gwdg.de/georoc/) and EarthChem (https://www.earthchem.org/) repositories (Supplementary Data 1). The komatiite and picrite samples in the database have ages ranging from Archean to present-day. We made a manual double-check of data quality against the original references to choose only komatiite (>18 wt% MgO, SiO2 < 52 wt%, and total alkali (K2O + Na2O) < 2 wt%) and picrite (>12 wt% MgO, SiO2 < 52 wt% and total alkali (K2O + Na2O) < 3 wt%) compositions14,15,30,31 for the plots of Supplementary Fig. 1. The present-day mid-ocean ridge basalts (MORBs) and arc-related basalts (ARBs), used in Figs. 1, 2 and Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, are assembled from the same repositories and filtered for samples with basaltic composition (i.e., 45–53 wt% SiO2, MgO < 12 wt%, and total alkali (K2O + Na2O) < 5 wt%14,15,31,32) and comprehensive major- and transition elements datasets including Ni, Cr, Co, Zn, Cu, and Sc. The present-day MORBs whole rock and glass database (~1200 samples) includes Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian mid-ocean ridges; the ARBs database (~5300 samples) includes oceanic-arc basalts, such as the Izu–Bonin–Mariana, Tonga, Sunda, Aleutian, Kermadec, New Hebrides, Kurile, and Lesser Antilles arcs, and continental-arc basalts such as that of the Andean, Cascades, and Central American arcs (Supplementary Data 1). The oceanic island basalts, oceanic flood basalts, and large igneous provinces database (~6200 samples) includes mainly Cenozoic basalts, such as the Hawaiian islands, Canary islands, Cape Verde islands, Society islands, St. Helena Chain, Deccan, Afro-Arabia, North Atlantic, Columbia River, Caribbean-Colombian, Hess rise, and Manihiki Plateau basalts (Supplementary Data 1).

Data bootstrap resampling

A geochemical database of major and transition elements of basalts (~41,000 samples), with ages ranging from 3.8 Ga to present-day, was extracted from the Georoc and EarthChem repositories (Figs. 3, 4; Supplementary Data 2), including age estimates and geospatial sample locations for each sample. Data with unknown age or sample location, suspicious data with major elements totaling >100%, and data from ultramafic cumulates or komatiites, have been manually filtered out. The database mainly consists of samples with a basaltic composition (i.e., 45–53 wt% SiO2 and total alkali (K2O + Na2O) < 5 wt%31) and age uncertainties below 50% relative standard deviation (RSD). To obtain an optimal estimate of composition distribution of Ni, Cr, and MgO in mantle-derived melts and minimize sampling and preservation bias, we did a weighted bootstrap resampling of the database following the method of Keller and Schoene35 using the Matlab MIT open-source code available at https://github.com/brenhinkeller/StatisticalGeochemistry.

Data availability

All the data that are necessary for evaluating the findings of this study are available within this article and it’s Supplementary Information.

Change history

05 June 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Dziewonski, A. M., Lekic, V. & Romanowicz, B. A. Mantle anchor structure: an argument for bottom up tectonics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 299, 69–79 (2010).

Burke, K., Steinberger, B., Torsvik, T. H. & Smethurst, M. A. Plume generation zones at the margins of large low shear velocity provinces on the core-mantle boundary. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 265, 49–60 (2008).

Torsvik, T. H. et al. Deep mantle structure as a reference frame for movements in and on the Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 8735–8740 (2014).

Anderson, D. L. Superplumes or supercontinents? Geology 22, 39 (1994).

Burke, K. & Torsvik, T. H. Derivation of large igneous provinces of the past 200 million years from long-term heterogeneities in the deep mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 227, 531–538 (2004).

Courtillot, V., Jaupart, C., Manighetti, I., Tapponnier, P. & Besse, J. On causal links between flood basalts and continental breakup. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 166, 177–195 (1999).

Torsvik, T. H., Burke, K., Steinberger, B., Webb, S. J. & Ashwal, L. D. Diamonds sampled by plumes from the core-mantle boundary. Nature 466, 352–355 (2010).

Li, Z. X. & Zhong, S. Supercontinent-superplume coupling, true polar wander and plume mobility: plate dominance in whole-mantle tectonics. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 176, 143–156 (2009).

Zhong, S., Zhang, N., Li, Z. X. & Roberts, J. H. Supercontinent cycles, true polar wander, and very long-wavelength mantle convection. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 261, 551–564 (2007).

Li, Z. X. et al. Assembly, configuration, and break-up history of Rodinia: a synthesis. Precambrian Res. 160, 179–210 (2008).

Li, Z. X. et al. Decoding Earth’s rhythms: modulation of supercontinent cycles by longer superocean episodes. Precambrian Res. 323, 1–5 (2019).

White, W. Probing the Earth’s deep interior through geochemistry. Geochemical Perspect. 4, 95–251 (2015).

Herzberg, C. Basalts as temperature probes of Earth’s mantle. Geology 39, 1179–1180 (2011).

Herzberg, C. et al. Temperatures in ambient mantle and plumes: constraints from basalts, picrites, and komatiites. Geochemistry, Geophys. Geosystems 8,Q02006 https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GC001390 (2007).

Condie, K. C., Aster, R. C. & Van Hunen, J. A great thermal divergence in the mantle beginning 2.5 Ga: geochemical constraints from greenstone basalts and komatiites. Geosci. Front. 7, 543–553 (2016).

Pearce, J. A. & Peate, D. Tectonic implications of volcanic Arc magmas. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 23, 251–285 (1995).

Gamal El Dien, H., Li, Z. -X., Kil, Y. & Abu-Alam, T. Origin of arc magmatic signature: a temperature-dependent process for trace element (re)-mobilization in subduction zones. Sci. Rep. 9, 7098 (2019).

Condie, K. C. Incompatible element ratios in oceanic basalts and komatiites: tracking deep mantle sources and continental growth rates with time. Geochem., Geophys. Geosystems 4, 1–28 (2003).

Wang, X.-C. et al. Identification of an ancient mantle reservoir and young recycled materials in the source region of a young mantle plume: implications for potential linkages between plume and plate tectonics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 377–378, 248–259 (2013).

Condie, K. C. & Shearer, C. K. Tracking the evolution of mantle sources with incompatible element ratios in stagnant-lid and plate-tectonic planets. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 213, 47–62 (2017).

Condie, K. Changing tectonic settings through time: indiscriminate use of geochemical discriminant diagrams. Precambrian Res. 266, 587–591 (2015).

Pearce, J. A. Geochemical fingerprinting of oceanic basalts with applications to ophiolite classification and the search for Archean oceanic crust. Lithos 100, 14–48 (2008).

White, W. M. Geochemistry. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756813000708 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

Leeman, W. P. & Scheidegger, K. Olivine/liquid distribution coefficients and a test for crystal-liquid equilibrium. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 35, 247–257 (1977).

Horn, I., Foley, S., Jakson, S. & Jenner, G. Experimentally determined partioning of high field strength-and selected transition elements between spinel and basaltic melt. Chem. Geol. 117, 193–218 (1994).

Tang, M., Chen, K. & Rudnick, R. L. Archean upper crust transition from mafic to felsic marks the onset of plate tectonics. Science 351, 372–375 (2016).

Lee, C.-T. A., Luffi, P., Plank, T., Dalton, H. & Leeman, W. P. Constraints on the depths and temperatures of basaltic magma generation on Earth and other terrestrial planets using new thermobarometers for mafic magmas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 279, 20–33 (2009).

Herzberg, C., Condie, K. & Korenaga, J. Thermal history of the Earth and its petrological expression. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 292, 79–88 (2010).

Keller, B. & Schoene, B. Plate tectonics and continental basaltic geochemistry throughout Earth history. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 481, 290–304 (2018).

Arndt, N., Lesher, C. M. & Barnes, S. J. Komatiite. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511535550 (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Le Bas, M. J. IUGS reclassification of the high-Mg and picritic volcanic rocks. J. Pet. 41, 1467–1470 (2000).

Le Maitre, R.W, Streckeisen, A., Zanettin, B., Le Bas, M.J., Bonin, B. & Bateman, P., editors. Igneous Rocks: A Classification and Glossary of Terms: Recommendations of the International Union of Geological Sciences Subcommission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks. 2nd ed. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511535581 (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Humayun, M., Qiu, L. & Norman, M. D. Geochemical evidence for excess iron in the Hawaiian mantle: implications for mantle dynamics. Science 306, 91–94 (2004).

Qin, L. & Humayun, M. The Fe/Mn ratio in MORB and OIB determined by ICP-MS. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 1660–1677 (2008).

Keller, C. B. & Schoene, B. Statistical geochemistry reveals disruption in secular lithospheric evolution about 2.5Gyr ago. Nature 485, 490–493 (2012).

Condie, K. C. A planet in transition: the onset of plate tectonics on Earth between 3 and 2 Ga? Geosci. Front. 9, 51–60 (2018).

Anderson, D. L. The thermal state of the upper mantle; no role for mantle plumes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 3623–3626 (2000).

Ionov, D. A. & Hofmann, A. W. Depth of formation of subcontinental off-craton peridotites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 261, 620–634 (2007).

Herzberg, C. et al. Nickel and helium evidence for melt above the core-mantle boundary. Nature 493, 393–397 (2013).

Salters, V. J. M. & Stracke, A. Composition of the depleted mantle. Geochem., Geophys. Geosystems 5, n/a–n/a (2004).

Mitchell, R. N., Kilian, T. M. & Evans, D. A. D. Supercontinent cycles and the calculation of absolute palaeolongitude in deep time. Nature 482, 208–211 (2012).

Tan, E., Leng, W., Zhong, S. & Gurnis, M. On the location of plumes and lateral movement of thermochemical structures with high bulk modulus in the 3-D compressible mantle. Geochem., Geophys. Geosystems 12, Q07005 https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GC003665 (2011).

Korenaga, J. Urey ratio and the structure and evolution of Earth’s mantle. Am. Geophys. Union 1–32 https://doi.org/10.1029/2007RG000241.1 (2008).

Cawood, P. A. et al. Geological archive of the onset of plate tectonics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Eng. Sci. 376, 20170405 (2018).

Flament, N., Williams, S., Müller, R. D., Gurnis, M. & Bower, D. J. Origin and evolution of the deep thermochemical structure beneath Eurasia. Nat. Commun. 8, 14164 (2017).

Hassan, R., Müller, R. D., Gurnis, M., Williams, S. E. & Flament, N. A rapid burst in hotspot motion through the interaction of tectonics and deep mantle flow. Nature 533, 239–242 (2016).

Zhang, N., Zhong, S., Leng, W. & Li, Z.-X. A model for the evolution of the Earth’s mantle structure since the Early Paleozoic. J. Geophys. Res. 115, B06401 (2010).

Simmons, N. A., Myers, S. C., Johannesson, G., Matzel, E. & Grand, S. P. Evidence for long-lived subduction of an ancient tectonic plate beneath the southern Indian Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 9270–9278 (2015).

Bono, R. K., Tarduno, J. A. & Bunge, H.-P. Hotspot motion caused the Hawaiian-Emperor Bend and LLSVPs are not fixed. Nat. Commun. 10, 3370 (2019).

Li, Z. X., Evans, D. A. D. & Zhang, S. A 90° spin on Rodinia: possible causal links between the neoproterozoic supercontinent, superplume, true polar wander and low-latitude glaciation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 220, 409–421 (2004).

Koelemeijer, P., Deuss, A. & Ritsema, J. Density structure of Earth’s lowermost mantle from Stoneley mode splitting observations. Nat. Commun. 8, 15241 (2017).

Forte, A. M. et al. Joint seismic–geodynamic-mineral physical modelling of African geodynamics: a reconciliation of deep-mantle convection with surface geophysical constraints. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 295, 329–341 (2010).

Evans, D. A. D., Li, Z. X. & Murphy, J. B. Four-dimensional context of Earth’s supercontinents. In Geological Society Special Publication (eds Li, Z.X., Evans, D. A. D. & Murphy, J. B.) 424, 1–14 (Geological Society of London, 2016).

Pourteau, A. et al. 1.6 Ga crustal thickening along the final Nuna suture. Geol. 46, 959–962 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate helpful comments and discussions with Brendan Murphy. We thank C.B. Keller for discussions regarding the bootstrap resampling method. Dr. Josh Beardmore is appreciated for proofreading the paper. Financial support by the Australian Research Council (grant FL150100133 to Z.X.L.) is acknowledged. This is a contribution to IGCP648: Supercontinent Cycles and Global Geodynamics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.G. conducted the data evaluation and analyses and designed the paper. L.S.D. did the bootstrap resampling for the database (Figs. 3, 4). Z.X.L. designed the study and clarified the concepts. H.G., L.S.D., and Z.X.L. participated in the interpretation of the results and preparation of the paper. G.M.C. and R.M. were involved in an early attempt of this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gamal EL Dien, H., Doucet, L.S., Li, ZX. et al. Global geochemical fingerprinting of plume intensity suggests coupling with the supercontinent cycle. Nat Commun 10, 5270 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13300-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13300-4

This article is cited by

-

Light oxygen isotopic composition in deep mantle reveals oceanic crust subduction before 3.3 billion years ago

Communications Earth & Environment (2024)

-

Mechanisms to generate ultrahigh-temperature metamorphism

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2023)

-

The supercontinent cycle

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2021)

-

Oceanic and super-deep continental diamonds share a transition zone origin and mantle plume transportation

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Deep mantle melting, global water circulation and its implications for the stability of the ocean mass

Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.