Abstract

Engineered enzyme cascades offer powerful tools to convert renewable resources into value-added products. Man-made catalysts give access to new-to-nature reactivities that may complement the enzyme’s repertoire. Their mutual incompatibility, however, challenges their integration into concurrent chemo-enzymatic cascades. Herein we show that compartmentalization of complex enzyme cascades within E. coli whole cells enables the simultaneous use of a metathesis catalyst, thus allowing the sustainable one-pot production of cycloalkenes from oleic acid. Cycloheptene is produced from oleic acid via a concurrent enzymatic oxidative decarboxylation and ring-closing metathesis. Cyclohexene and cyclopentene are produced from oleic acid via either a six- or eight-step enzyme cascade involving hydration, oxidation, hydrolysis and decarboxylation, followed by ring-closing metathesis. Integration of an upstream hydrolase enables the usage of olive oil as the substrate for the production of cycloalkenes. This work highlights the potential of integrating organometallic catalysis with whole-cell enzyme cascades of high complexity to enable sustainable chemistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The exquisite performance and sophisticated orchestration of metabolic reaction networks have inspired the transition from single-step biocatalysis1,2,3,4,5 to cascade biocatalysis –interconnected enzymatic reactions in one pot6,7. This strategy allows to minimize the isolation and workup of intermediates, thus reducing operation time, waste and, sometimes, enhancing overall selectivity and yield. Furthermore, enzymes may be combined with organometallic catalysts to assemble chemo-enzymatic cascades to perform useful one-pot transformations unattainable with enzymes or small-molecule catalysts alone8,9,10,11,12,13. In the past 6 years, significant progress have been made in combining enzymes with organometallic catalysts14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, including photocatalysts22,23,24. For this purpose, different strategies were implemented to accommodate the incompatible reactivities in a single vessel. Despite these achievements, most of the chemo-enzymatic cascades reported to date are limited to one or two enzymatic steps25,26. Quite on the contrary, the inherent sophistication of the metabolism in cells, which leverage the exquisite synthetic power of enzyme pathways, suggests the feasibility of much more complex reaction schemes.

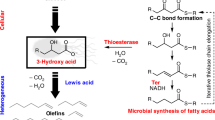

Synthetic biology and metabolic engineering hold great promise for sustainable chemical production from renewable resources via engineered microbial cell factories operating in single-vessel processes27,28,29. Combining enzymes from different organisms substantially expands the scope of bioproduction; however, it remains limited to the existing enzymes’ repertoire. For example, the recent discovery of decarbonylases and decarboxylases has led to bioproduction of various hydrocarbons30,31,32, including various linear alkanes33,34, linear alkenes35,36,37 and aromatics38,39 (Fig. 1). However, to the best of our knowledge, cycloalkanes and cycloalkenes have not been reported via enzymatic pathways. Cycloalkenes are bulk petrochemicals widely employed in various industrial processes40, including use as solvents, synthesis of cyclic compounds (e.g. cyclohexanol)41 and ring-opened chemicals (e.g. adipic acid)42. Currently, cycloalkenes are derived from fossil-fuels (e.g. steam cracking of naphtha and partial hydrogenation of benzene)40. The unavailability of enzymatic production is likely due to the limited number of enzyme-catalyzed C–C cyclization reactions. Indeed, most of these enzymes43,44 (e.g. terpene cyclases) are highly substrate-specific thus limiting their widespread implementation. Recent advances in heme-proteins that catalyze an abiotic carbene transfer offer a powerful means to generate cyclopropane or cyclopropene rings (C3)45,46,47,48. Building on our previous work on ring-closing metathesis (RCM) in a biocompatible environment49,50,51, we contemplated the possibility of capitalizing on RCM to construct cycloalkenes (C5-C7) from diolefins produced from renewable sources.

Production of hydrocarbons from bio-based resources via (chemo-)enzymatic cascades. Bio-based linear alkanes and alkenes are produced from renewable feedstock via enzyme pathways that include decarbonylases or decarboxylases. Engineering a chemo-enzymatic cascade that comprises a decarboxylase and a ring-closing metathesis catalyst leads to the production of bio-based cycloalkenes

Herein we report on our efforts to combine ring-closing metathesis with an engineered multi-enzyme cascade to produce cyclopentene, cyclohexene, and cycloheptene from olive oil-derived intermediates (Fig. 1). This development, combining a concurrent RCM with up-to nine enzymatic steps hosted by whole cells of E. coli in a single reaction vessel, showcases the potential of integrating biocompatible, new-to-nature reactions with synthetic biology at high sophistication.

Results

Design of chemo-enzymatic cascades

We applied a biocatalytic retrosynthetic analysis52,53 to design chemo-enzymatic cascades to produce cyclopentene (1a), cyclohexene (1b), and cycloheptene (1c) from oleic acid (6) (Fig. 2a, b). We hypothesized that cycloalkenes (1a-1c) may be accessed via ring-closing metathesis of the corresponding α,ω-dienes (2a-2c), which, in turn, can be produced from an oxidative bis-decarboxylation of α,ω-dicarboxylic acids (4a-4c) using a decarboxylase35,36,37 (Fig. 2a). Exploratory studies using oleic acid (6) suggested that decarboxylation of carboxylate 6 affords 1,8-heptadecadiene (5), which may undergo ring-closing metathesis to afford cycloheptene 1c and 1-decene (Fig. 2b). To access the synthetically more useful cyclopentene (1a) and cyclohexene (1b) from oleic acid 6, we surmised that one could complement previously reported enzyme cascades54 –for the production of diacids from oleic acid– with a decarboxylase and an RCM catalyst. The diacids 4a and 4b are produced via a six- and four enzyme-cascade, respectively (Fig. 2b). This is achieved via hydration of oleic acid (6) by OhyA2, followed by oxidation with MlADH to the corresponding keto-acid. Subjecting the keto-acid to a Baeyer–Villiger monooxygenase, using either PpBVMO or PfBVMO, followed by hydrolysis by TLL affords either sebacic acid (4b) –with PfBVMO– or a hydroxy-carboxylic acid –with PpBVMO–. The latter may be oxidized by ChnD and ChnE to afford azelaic acid (4a)55 (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1 for details). As olive oil is readily hydrolyzed by TLL to afford oleic acid 6, one may thus be able to produce cycloalkenes 1a-1c, typically derived from petroleum-based feedstocks, from renewable resources via a concurrent chemo-enzymatic cascade.

Chemo-enzymatic cascades to produce cycloalkenes from dicarboxylic acids, oleic acid, and olive oil. a Conversion of diacids (4a-4c) to cycloalkenes (1a-1c) via a concurrent bis-decarboxylation and metathesis. b Chemo-enzymatic cascades for the conversion of olive oil (7) or oleic acid (6) to cycloheptene (1c), cyclopentene (1a, via azelaic acid, 4a) and cyclohexene (1b, via sebacic acid, 4b). c Structure of the selected RCM catalyst Ru3

Selection of the decarboxylase

To identify a suitable enzyme for the bis-decarboxylation of 4a-4c, we evaluated three oxidative decarboxylases, including: (i) a P450 monooxygenase OleT, combined with the putidaredoxin CamAB37, (ii) a non-heme mononuclear iron oxidase UndA from Pseudomonas35, and (iii) a membrane-bound desaturase-like enzyme UndB from Pseudomonas36. These enzymes expressed well in recombinant E. coli strains as confirmed by SDS–PAGE analysis of the whole-cell protein extracts (Supplementary Fig. 2). The E. coli whole cells were used for the bis-decarboxylation of 4a-4c and decarboxylation of the intermediate ω-alkenoic acids (3a-3c) to afford the corresponding α,ω-dienes (2a-2c) in aqueous potassium phosphate buffer (KP). As summarized in Fig. 3a–c, both UndA and UndB displayed good activity towards medium-chain carboxylates 3a-3c, while OleT was inactive. Remarkably, only UndB catalyzed the bis-decarboxylation of 4a-4c to afford 2a-2c. These results are consistent with previous reports: OleT prefers long-chain saturated fatty acids37,56, while UndA and UndB favor medium-chain fatty acids35,36. Under optimized conditions, the bis-decarboxylation of 4a-4c in the presence of E. coli overexpressing UndB was improved to afford increased amounts of 2a (1600 μM, 32% conversion), 2b (1900 μM, 38% conversion) and 2c (800 μM, 16% conversion), respectively (Fig. 3a–c). In view of the hydrophobicity and low aqueous solubility of dienes 2a-2c, we examined a range of water-miscible and immiscible solvents as well as several surfactants added to the phosphate buffer. The results (Supplementary Fig. 3) suggest that n-dodecane (10%), abbreviated KP-Dod hereafter, and the non-ionic surfactant TPGS-750-M57,58 (1%) are compatible with E. coli (UndB), maintaining >50% productivity for the conversion of 4b to 2b. Although isooctane is often used in conjunction of purified enzymes16,17,20, it dramatically reduced the activity of UndB, probably due to the destabilization of the cell membrane. Thus, n-dodecane and TPGS-750-M were selected for further studies. Up to ≥80% conversion was obtained starting from 2 mM of 4a and 4b or 1 mM of 4c by E. coli (UndB) in KP buffer with or without either n-dodecane or TPGS-750-M (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Results for the (bis-)decarboxylation by decarboxylases and the RCM by Ru-based catalysts. a–c Decarboxylation of 3a-3c and 4a-4c (5 mM) to the corresponding dienes 2a-2c in the presence of E. coli cells (10 g l−1) expressing OleT, UndA, or UndB in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 2% glucose) at 30 °C for 24 h. * stands for the optimized condition in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose). d RCM of diene 2b (5 mM) by ruthenium catalyst Ru1-Ru3 (100 μM) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0) with or without n-dodecane (10%) or TPGS-750-M (1%) at 30 °C for 24 h. e, f RCM of diene 2a and 2c (5 mM) by Ru3 (100–250 μM) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data are mean values of triplicates with error bars indicating standard deviations (n = 3). (See Supplementary Fig. 5 for the structure of Ru1 and Ru2)

Identification of the most suitable metathesis catalyst

To identify a biocompatible metathesis catalyst, we selected three commercial (Hoveyda)-Grubbs ruthenium(II) catalysts (Ru1, Ru2, Ru3, Supplementary Fig. 5), which have been reported to tolerate air and water51. The RCM activity of Ru1, Ru2, Ru3 (100 μM, 2 mol%) was evaluated for diolefin 2b (5 mM) either in: (i) KP buffer, (ii) KP buffer and n-dodecane (10%), or (iii) in KP buffer containing the non-ionic surfactant TPGS-750-M (1%) (Fig. 3d). In all cases, the formation of cyclohexene 1b was detected. The biphasic system with 10% n-dodecane clearly outperformed both other systems. To our delight, Ru3 (Fig. 3d) afforded cyclohexene in >90% conversion for the biphasic system. Both other diolefin substrates 2a and 2c afforded cyclopentene 1a (87% conversion) and cycloheptene 1c (72% conversion), respectively (Fig. 3e, f). RCM of dienes 2a and 2b (5 mM) in the presence of a lower catalyst Ru3 loading (50 μM, 1%) using the KP-Dod system afforded cycloalkenes 1a and 1b in 75% and 88% conversions respectively (corresponding to TTNs of 75 and 88). The commercially available catalyst Ru3 was thus selected for the implementation of the chemo-enzymatic cascades.

A cascade to convert diacids to cycloalkenes

E. coli (UndB) whole cells were combined with catalyst Ru3 for the conversion of sebacic acid 4b to cyclohexene 1b in KP buffer via a concurrent chemo-enzymatic cascade. As displayed in Fig. 4a, cyclohexene 1b (25% conversion) was produced only in the presence of both UndB and catalyst Ru3, highlighting the remarkable compatibility of the metathesis catalyst with E. coli whole cells. Addition of either n-dodecane (10%) or TPGS-750-M (1%) to the reaction mixture led to significantly improved conversions: up to 80% conversion was obtained in the presence of the KP-Dod. The chemo-enzymatic cascade catalysis was also performed in a sequential mode by adding the metathesis catalysts after 24 h reaction in the presence of E. coli (UndB). The results are similar to those obtained in the concurrent cascade: high conversion (83%) was only achieved with Ru3 in KP-Dod (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 6). The sequential cascade however required 48 h instead of 24 h for the concurrent cascade to achieve comparable conversions. The reaction progress of the concurrent cascade (Supplementary Fig. 7) reveals minimal accumulation of intermediates 2b and 3b, thus highlighting that the cascade proceeds in a concurrent manner. Next, the E. coli (UndB) and Ru3 were used in the KP-Dod mixture to convert the diolefins 4a and 4c to cyclopentene 1a and cycloheptene 1c in high conversion (83% and 77% conversion, respectively, Fig. 4b, c).

Bis-decarboxylation-metathesis cascade for the conversion of diacids (4a-4c) to cycloalkenes (1a-1c). a Concurrent or sequential cascade for the conversion of diacid 4b (2 mM) to 1b in the presence of E. coli (UndB) (10 g l−1) and Ru3 (100 μM) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose), KP buffer and n-dodecane (10%) or KP buffer and TPGS-750-M (1%) at 30 °C for 24 h. b One-pot conversion of diacid 4a (2 mM) to cyclopentene (1a) with E. coli (UndB) (10 g l−1) and Ru3 (100 μM) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose) with n-dodecane (10%) at 30 °C for 24 h. c One-pot conversion of diacid 4c (1 mM) to cycloheptene (1c) with E. coli (UndB) (10 g l−1) and Ru3 (50 μM) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose) with n-dodecane (10%) at 30 °C for 24 h. For the sequential mode, Ru3 was added at 24 h and reacted for another 24 h (total 48 h). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data are mean values of triplicate experiments with error bars indicating standard deviations (n = 3)

A concurrent cascade to convert oleic acid to cycloheptene

Upon enzymatic decarboxylation, oleic acid (6) is converted to 1,8-heptadecadiene (5), a bio-based precursor of cycloheptene (1c, Fig. 2b). Accordingly, a two-step decarboxylation-metathesis cascade was engineered to convert oleic acid (6) to cycloheptene (1c). The E. coli strains over-expressing OleT, UndA, and UndB were examined for decarboxylation of oleic acid (6) (5 mM) in KP buffer, to afford 1,8-heptadecadiene (5). While OleT is known to display very modest activity toward Δ9 unsaturated fatty acids59, E. coli (UndB) performed the best, giving 33% conversion to diene 5 (Fig. 5a). Upon combining E. coli (UndB) with Ru3, oleic acid (6) (2 mM) was converted to cycloheptene (1c) in the KP-Dod system in 44% conversion (Fig. 5b). The chemo-enzymatic cascade also performed well in a sequential mode: adding the catalyst Ru3 after 12 h allowed to maintain the same overall reaction time at the cost of a lower conversion however (24 h, 33% conversion, Fig. 5b). In a similar fashion, the two-step chemo-enzymatic cascade could be used to produce cyclopentene (1a) and cyclohexene (1b), but the corresponding fatty acids with a C=C bond at position 7 and 8 are not readily available. To access these cycloalkenes, we thus engineered the corresponding enzyme cascades in E. coli to produce the diolefins from oleic acid (6).

Whole-cell decarboxylation-metathesis cascade for the conversion of oleic acid (6) to cycloheptene (1c). a Decarboxylation of oleic acid (6) (5 mM) to diolefin 5 by E. coli cells (10 g l−1) expressing OleT, UndA, or UndB in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose) at 30 °C for 24 h. b Concurrent conversion of oleic acid (6) (2 mM) to cyclopentene 1c with E. coli (UndB) (10 g l−1) and Ru3 (100 μM) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose) in the presence of n-dodecane (10%) at 30 °C for 24 h. For the sequential cascade, n-dodecane and Ru3 were added at 12 h and reacted for another 12 h (total 24 h). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data are mean values of triplicate experiments with error bars indicating standard deviations (n = 3)

Engineering E. coli cells to convert oleic acid to diacids

To produce cyclopentene (1a) and cyclohexene (1b) from oleic acid (6), it is necessary to engineer enzyme cascades to produce the corresponding sebacic acid (4b) and azelaic acid (4a) from oleic acid (6). Two previous enzyme cascades54 have reported the conversion of oleic acid (6) to diacids 4a and 4b via hydration, oxidation, Baeyer–Villiger oxidation (with different regioselectivity) and hydrolysis by TLL (for 4b), as well as further double oxidation (for 4a)55 (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1 for details). The reported cascades were accomplished by combining multiple E. coli strains as well as purified enzymes. We set out to implement this complex cascade in a single E. coli strain.

According to previous reports54,55 and our experience, the bottleneck in the above cascades is likely the Baeyer–Villiger oxidation by PfBVMO (for 4b) and PpBVMO (for 4a). Some N-terminal tags on BVMOs have been shown to improve the stability of the enzymes60. Thus, fusion of BVMOs with different N-terminal tags was tested: the 6x Glu-tagged PfBVMO and 6x His-tagged PpBVMO outperformed other constructs, including BVMOs with no tag (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). A native fatty-acid transporter, FadL, was overexpressed and found to boost the hydration of oleic acid (6) in E. coli (Supplementary Fig. 10). The other enzymes (OhyA2, MlADH, TLL) expressed well in individual E. coli strains (Supplementary Fig. 11).

In order to combine all required activities for the conversion of oleic acid (6) to the dicarboxylate 4a or 4b in a single E. coli strain, we sought to optimize the absolute and relative expression levels of the corresponding enzymes relying on engineering of the respective ribosome binding sites (RBSs). Therefore, we performed combinatorial pathway optimization by applying the recently developed algorithm RedLibs61 to design tailor-made degenerate RBS sequences. Briefly, degenerate RBSs were designed to achieve four different expression levels for each of the four involved genes with the goal to uniformly span the accessible range (Supplementary Fig. 20). For the production of sebacic acid (4b), primers with degenerate RBS (4×) were used to amplify PfBVMO, MlADH, OhyA2, and TLL (with the plasmid backbone). The resulting combinatorial library (combinatorial size: 4 × 4 × 4 × 4 = 256 variants) was assembled in vitro and used to transform E. coli (Fig. 6a). In total 576 of the resulting colonies were randomly picked (~89.5% statistical coverage), cultured in six 96-deep well plates and assayed for the conversion of oleic acid (6). The concentration of sebacic acid (4b) was quantified by UPLC analysis (Fig. 6b). The best four strains for each plate were cultured in flasks for further validation and quantification of the produced sebacic acid (4b) (Fig. 6c). The most promising strain, coined E. coli (C10) hereafter (P1-A4 in Fig. 6c), was selected for converting oleic acid (6) to sebacic acid (4b) in further experiments. For the more complex production of azelaic acid (4a), a two-stage optimization procedure using RedLibs was applied to construct and identify the best strain, E. coli (C9). To this end, we first optimized PpBVMO, MlADH, OhyA2, and TLL for production of 9-hydroxynonanoic acid in a first combinatorial RBS optimization similar as before for the production of sebacic acid (Supplementary Fig. 12). Afterwards, the best-performing clone from this first stage was applied to a second round of combinatorial screening to optimize ChnD, ChnE, and FadL for production of azelaic acid (4a) (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Engineering and screening a strain library for the production of sebacic acid (4b) from oleic acid (6). a Construction of a plasmid library for the co-expression of PfBVMO, MlADH, OhyA2, and TLL with different expression levels, and screening of the resulting E. coli library to identify the most effective strain for the production of sebacic acid (4b). All E. coli strains included an additional plasmid harboring the fatty acid transporter FadL. b Initial screening of 576 strains in six 96-well plates for production of sebacic acid (4b). c Further validation and comparison of 24 strains (best four from each plate) for the production of sebacic acid (4b). The green column indicates the best strain E. coli (C10). The reactions were performed using oleic acid (6) (5 mM) and E. coil (10 g l−1) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose) at 30 °C for 24 h. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data in c are mean values of triplicate experiments with error bars indicating standard deviations (n = 3)

Cascades for oleic acid to cyclopentene and cyclohexene

Cyclopentene (1a) may be produced from oleic acid (6) via a chemo-enzymatic cascade by combining E. coli (C9), E. coli (UndB) and Ru3 either in a concurrent- or a sequential cascade. Since E. coli (UndB) also catalyzes the decarboxylation of oleic acid (6) to form the diolefin 1,8-heptadecadiene (5), E. coli (UndB) and Ru3 can only be added after the conversion of oleic acid to the corresponding diacids, sebacic acid (4b) and azelaic acid (4a), respectively. As highlighted in Fig. 7a, adding all three catalytic components simultaneously (i.e. E. coli (C9), E. coli (UndB) and Ru3), cyclopentene (1a) was produced in only 14% conversion from oleic acid 6 (2 mM). In contrast, the delayed addition of E. coli (UndB) and Ru3 led to cyclopentene (1a) in 65% conversion under the same reaction conditions. We surmise that the cross-reactivity of E. coli (UndB) is the major ground for the erosion of the conversion in the concurrent cascade. For the production of cyclohexene (1b) from oleic acid (6), the E. coli (C10), and E. coli (UndB) strains as well as the RCM catalyst Ru3 were combined in one pot either simultaneously or sequentially, (Fig. 7b). Again here, the delayed addition of E. coli (UndB) and Ru3 led to significantly higher conversions of cyclohexene (1b) (compare 6 % for the simultaneous vs. 22 % conversion for the sequential cascade starting with 2 mM oleic acid (6)). The modest conversion of cyclohexene (1b) is tentatively assigned to the low productivity of PfBVMO (Supplementary Fig. 14). The modest productivity of the former may be improved by engineering a more active BVMO. In summary, by combining two engineered E. coli strains and a ruthenium complex Ru3, cyclopentene (1a) and cyclohexene (1b) were produced from oleic acid (6) in one pot in titers 1.30 mM and 0.44 mM after 24 h, respectively.

Chemo-enzymatic cascades for the conversion of oleic acid to cyclopentene (1a) and cyclohexene (1b). a One-pot conversion of oleic acid (6) (2 mM) to cyclopentene (1a) using E. coli (C9) (10 g l−1), E. coli (UndB) (10 g l−1) and Ru3 (100 μM) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose) with n-dodecane (10%) at 30 °C for 24 h. b One-pot conversion of oleic acid (6) (2 mM) to cyclohexene (1b) using E. coli (C10) (10 g l−1), E. coli (UndB) (10 g l−1) and Ru3 (100 μM) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose) with n-dodecane (10%) at 30 °C for 24 h. For the sequential cascade, E. coli (UndB), Ru3 and n-dodecane were added after 12 h and the reaction was carried on for another 12 h (total 24 h). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data are mean values of triplicate experiments with error bars indicating standard deviations (n = 3)

Cascades to convert olive oil to cycloalkenes

Currently, oleic acid is usually manufactured from plant oils (e.g. canola oil, olive oil) on a very large scale62. To directly utilize these attractive bio-based feedstocks (or even waste oil), we further extend the chemo-enzymatic cascades from a readily available plant oil–olive oil (7), as an example. The enzymatic hydrolysis of olive oil (7) produces oleic acid (6) under mild conditions and is compatible with the implementation of enzyme-cascades. We thus engineered E. coli (TLL) cells expressing the lipase from Thermomyces lanuginosus for the hydrolysis of olive oil (7) to oleic acid (6). The E. coli (TLL) cells were lyophilized and stored. Using the lyophilized cells (1 g l−1), oleic acid (6) was produced with titers ranging from 1.1-2.5 mM from olive oil 7 (1-2 g l−1) in 1–3 h (Supplementary Fig. 15). To produce cycloheptene (1c) from olive oil 7, lyophilized E. coli (TLL), E. coli (UndB) and Ru3 were combined simultaneously or sequentially in one pot. As presented in Fig. 8a, 610–670 μM of cycloheptene (1c) was produced from olive oil (7, 1 g l−1) via this chemo-enzymatic cascade in a concurrent mode as well as two complementary sequential modes. A third sequential cascade afforded cycloheptene (1c) in lower concentration (330 μM). We hypothesize that the lower conversion may be due to the limited RCM reaction time applied in the third sequential cascade. For the production of cyclopentene (1a) from olive oil (7), lyophilized E. coli (TLL), E. coli (C9), E. coli (UndB) and Ru3 were combined sequentially in one pot: to our delight, 760 μM of cyclopentene (1a) was produced from olive oil (7, 1 g l−1) via this extended chemo-enzymatic cascade that includes nine enzymatic reactions preceding the final ring-closing metathesis step (Fig. 8b). Similarly, combining lyophilized E. coli (TLL), E. coli (C10), E. coli (UndB) and Ru3 sequentially, enabled the production of cyclohexene (1b) in 710 μM from olive oil (7, 1 g l−1) via a chemo-enzymatic cascade that includes seven enzymatic steps preceding the final RCM reaction (Fig. 8c). Assuming oleic acid accounts for 70% of the fatty acids in olive oil, the production of cycloalkenes (1a-1c) in 670-760 μM corresponds to around 29–33% conversion from olive oil (7, 1 g l−1). Although the overall conversion to cycloalkenes is rather modest, the chemo-enzymatic cascades showcase the feasibility to produce cycloalkenes from a renewable feedstock. Currently, the performance of the cascades is limited by the modest decarboxylase activity of UndB, which we surmise may be overcome by directed evolution63,64,65,66,67. Considering that oleic acid and diacids are often encountered by microbes, discovering and evolving yet unknown decarboxylases specific for oleic acid or diacids may allow to overcome the current bottleneck of the cascades. In analogy to the discovery of an efficient decarboxylase38 which led to the efficient production of styrene via a two-step deamination-decarboxylation cascade68, the discovery and/or evolution of a more efficient decarboxylase may allow to significantly enhance the yields of cycloheptene 1c via the two-step decarboxylation-metathesis cascade. Similarly, the extended cascades towards cyclopentene 1a and cyclohexene 1b, may be further improved by relying on recently evolved69 or discovered70 BVMOs. Nevertheless, the extended one-pot chemo-enzymatic cascades that include (up to) nine enzymatic steps demonstrates the possibility to integrate a transition metal-catalyzed reaction with synthetic biology at high complexity.

Chemo-enzymatic cascades for the conversion of olive oil (7) to cycloalkenes (1a-1c). a One-pot conversion of olive oil (7) (1 g l−1) to cyclopentene (1a) with E. coli (TLL) (1 g l−1), E. coli (UndB) (10 g l−1) and Ru3 (100 μM) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose) in the presence of n-dodecane (10%) at 30 °C for 24 h. Sequential 1: Ru3 was added after 2 h (total reaction time: 24 h). Sequential 2: E. coli (UndB) and Ru3 were added after 2 h (total 24 h). Sequential 3: E. coli (UndB) was added after 2 h, and Ru3 was added after 12 h (total 24 h). b One-pot conversion of 7 (1 g l−1) to cyclopentene (1a) with E. coli (TLL) (1 g l−1), E. coli (C9) (10 g l−1, added after 1 h), E. coli (UndB) (10 g l−1, added after 12 h) and Ru3 (100 μM, added after 12 h) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose) with n-dodecane (10%, added after 12 h) at 30 °C for 24 h. c One-pot conversion of olive oil (7) (1 g l−1) to cyclohexene (1b) with E. coli (TLL) (1 g l−1), E. coli (C10) (10 g l−1, added after 1 h), E. coli (UndB) (10 g l−1, added after 12 h) and Ru3 (100 μM, added after 12 h) in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0, 1% glucose) with n-dodecane (10%, added after 12 h) at 30 °C for 24 h. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data are mean values of triplicate experiments with error bars indicating standard deviations (n = 3)

Discussion

In summary, we have integrated a ruthenium-catalyzed ring-closing metathesis reaction as the last step of complex enzyme cascades for the one-pot production of cyclopentene (1a), cyclohexene (1b), and cycloheptene (1c) from olive oil (7) and its derivatives. The development of an aqueous-n-dodecane two-phase system enabled the combination of a ruthenium-based catalyst Ru3 with a delicate membrane-bound decarboxylase as part of extended enzyme cascades in E. coli whole cells, including up to nine enzymatic steps. The (chemo)-bioproduction of cycloalkenes from bio-based resources significantly expands the product realm accessible thanks to synthetic biology. The efficiency of the chemo-enzymatic cascades may be further engineered via the identification and/or the directed evolution of (more active) enzymes. The complementarity of homogeneous catalysts and enzymes allows the introduction of new-to-nature reactions with whole-cell enzyme cascades, thus synergizing the synthetic power of organometallic chemistry and synthetic biology.

Methods

Materials

Ru1, Ru2, Ru3, and n-dodecane were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. Except for OleT, the genes of all the other enzymes were synthesized from Gene Universal. The recombinant E. coli strains were engineered using standard molecular cloning techniques by restriction enzymes or Gibson assembly. All the other chemicals were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. See Supplementary Table 1 for all the primers used in this study.

Preparation of engineered E. coli whole cells

LB medium (1 ml) with appropriate antibiotics was inoculated with recombinant E. coli cells and cultured for 8–10 h at 37 °C 250 rpm. Then, the cells were transferred to modified M9 medium (50 ml, with 2% glucose and 0.6% yeast extract) in a baffled flask to grow at 37 °C until OD600 of the culture reached 0.6–0.8. At this time, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. The culture was carried on at 22 °C for 12–14 h. The E. coli cells were harvested by centrifugation and immediately used in the enzyme cascades. For E. coli (TLL), the cells were harvested, washed with water, lyophilized, stored at 4 °C, and added as powder when needed.

Typical procedure for performing chemo-enzymatic cascades

Substrate stock solutions were prepared by dissolving in EtOH: 4a-4c (250 mM), 6 (250 mM), and 7 (100 g l−1, emulsion). Stock solutions of cells were prepared by resuspending freshly harvested E. coli (C9), E. coli (C10) and/or E. coli (UndB) cells in KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0). The density of cells (OD600) was determined with a UV-spectrometer. Stock solutions of Ru3 (5 mM) were freshly prepared by dissolving Ru3 in DSMO: EtOH 1: 1. To an air-tight reaction tube (25 ml) with screw-cap, stock solutions of cells, KP buffer (200 mM, pH 8.0) and stock solution of glucose (50%) were added to form a system (0.5 ml) with required density/concentrations (cells: 10 g l−1, glucose: 1%). Then, n-dodecane (50 μl) and stock solutions of Ru3 (5–10 μl) were added to the reaction tube. The stock solutions of the substrates (2–10 μl) were added last. The reaction tubes were sealed and incubated at 250 rpm, 30 °C for 24 h. For the cascades in the sequential mode, the appropriate amounts of cells, n-dodecane (50 μl) and Ru3 were added at the specified time. Upon completion, the reaction tubes were incubated on ice for 15–20 min before opening these (to minimize the loss of volatile alkenes) and adding of EtOAc (1 ml, containing 1 mM of acetophenone as internal standard). The reaction products were extracted, dried over Na2SO4, and analyzed by GC–MS. See Supplementary Methods for details. See Supplementary Figs. 16 and 21 for the calibration curves. See Supplementary Figs. 17–19 for the representative GC-MS chromatograms.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The DNA sequences of the synthetic genes are available in the SI file and they have been deposited in GenBank with the accession codes (UndA: MN125553; UndB: MN125554; PfBVMO: MN125555; PpBVMO: MN125556; MlADH: MN125557; OhyA2: MN125558; TLL: MN125559; ChnD: MN125560; ChnE: MN125561). The source data used to generate Figs. 3–8 and Supplementary Figs. 2–4, 6–16 and 20–21 are provided as a Source Data file. The other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The source code for RedLibs algorithm is available at GitHub: https://github.com/dgerngross/RedLibs.

References

Bornscheuer, U. T. et al. Engineering the third wave of biocatalysis. Nature 485, 185–194 (2012).

Reetz, M. T. Biocatalysis in organic chemistry and biotechnology: past, present, and future. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 12480–12496 (2013).

Nestl, B. M., Hammer, S. C., Nebel, B. A. & Hauer, B. New generation of biocatalysts for organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 3070–3095 (2014).

Sheldon, R. A. & Woodley, J. M. Role of biocatalysis in sustainable chemistry. Chem. Rev. 118, 801–838 (2017).

Devine, P. N. et al. Extending the application of biocatalysis to meet the challenges of drug development. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 409–421 (2018).

France, S. P., Hepworth, L. J., Turner, N. J. & Flitsch, S. L. Constructing biocatalytic cascades: in vitro and in vivo approaches to de novo multi-enzyme pathways. ACS Catal. 7, 710–724 (2017).

Schrittwieser, J. H., Velikogne, S., Hall, M. & Kroutil, W. Artificial biocatalytic linear cascades for preparation of organic molecules. Chem. Rev. 118, 270–348 (2018).

Rudroff, F. et al. Opportunities and challenges for combining chemo-and biocatalysis. Nat. Catal. 1, 12–22 (2018).

Dumeignil, F. et al. From sequential chemoenzymatic synthesis to integrated hybrid catalysis: taking the best of both worlds to open up the scope of possibilities for a sustainable future. Catal. Sci. Technol. 8, 5708–5734 (2018).

Schmidt, S., Castiglione, K. & Kourist, R. Overcoming the incompatibility challenge in chemoenzymatic and multi-catalytic cascade reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 1755–1768 (2018).

Ríos-Lombardía, N., García-Álvarez, J. & González-Sabín, J. One-pot combination of metal-and bio-catalysis in water for the synthesis of chiral molecules. Catalysts 8, 75 (2018).

Verho, O. & Bäckvall, J. E. Chemoenzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution: a powerful tool for the preparation of enantiomerically pure alcohols and amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 3996–4009 (2015).

Denard, C. A., Hartwig, J. F. & Zhao, H. Multistep one-pot reactions combining biocatalysts and chemical catalysts for asymmetric synthesis. ACS Catal. 3, 2856–2864 (2013).

Köhler, V. et al. Synthetic cascades are enabled by combining biocatalysts with artificial metalloenzymes. Nat. Chem. 5, 93–99 (2013).

Wang, Z. J., Clary, K. N., Bergman, R. G., Raymond, K. N. & Toste, F. D. A supramolecular approach to combining enzymatic and transition metalcatalysis. Nat. Chem. 5, 100–103 (2013).

Denard, C. A. et al. Cooperative tandem catalysis by an organometallic complex and a metalloenzyme. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 465–469 (2014).

Denard, C. A. et al. Development of a one-pot tandem reaction combining ruthenium-catalyzed alkene metathesis and enantioselective enzymatic oxidation to produce aryl epoxides. ACS Catal. 5, 3817–3822 (2015).

Gómez Baraibar, A. et al. A one-pot cascade reaction combining an encapsulated decarboxylase with a metathesis catalyst for the synthesis of bio-based antioxidants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 14823–14827 (2016).

Latham, J. et al. Integrated catalysis opens new arylation pathways via regiodivergent enzymatic C–H activation. Nat. Commun. 7, 11873 (2016).

Scalacci, N. et al. Unveiling the biocatalytic aromatizing activity of monoamine oxidases MAO-N and 6-HDNO: development of chemoenzymatic cascades for the synthesis of pyrroles. ACS Catal. 7, 1295–1300 (2017).

Bojarra, S. et al. Bio‐based α, ω‐functionalized hydrocarbons from multi‐step reaction sequences with bio‐and metallo‐catalysts based on the fatty acid decarboxylase OleTJE. ChemCatChem 10, 1192–1201 (2018).

Litman, Z. C., Wang, Y., Zhao, H. & Hartwig, J. F. Cooperative asymmetric reactions combining photocatalysis and enzymatic catalysis. Nature 560, 355–359 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Selective aerobic oxidation reactions using a combination of photocatalytic water oxidation and enzymatic oxyfunctionalizations. Nat. Catal. 1, 55–62 (2018).

Guo, X., Okamoto, Y., Schreier, M. R., Ward, T. R. & Wenger, O. S. Enantioselective synthesis of amines by combining photoredox and enzymatic catalysis in a cyclic reaction network. Chem. Sci. 9, 5052–5056 (2018).

Wallace, S. & Balskus, E. P. Interfacing microbial styrene production with a biocompatible cyclopropanation reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 7106–7109 (2015).

Sharma, S. V. et al. Living GenoChemetics by hyphenating synthetic biology and synthetic chemistry in vivo. Nat. Commun. 8, 229 (2017).

Nielsen, J. & Keasling, J. D. Engineering cellular metabolism. Cell 164, 1185–1197 (2016).

Smanski, M. J. et al. Synthetic biology to access and expand nature’s chemical diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 135–149 (2016).

Lee, S. Y. et al. A comprehensive metabolic map for production of bio-based chemicals. Nat. Catal. 2, 18–33 (2019).

Zhou, Y. J., Kerkhoven, E. J. & Nielsen, J. Barriers and opportunities in bio-based production of hydrocarbons. Nat. Energy 3, 925–935 (2018).

Payer, S. E., Faber, K. & Glueck, S. M. Non-oxidative enzymatic (De)carboxylation of (Hetero) aromatics and acrylic acid derivatives. Adv. Synth. Catal. 361, 2402–2420 (2019).

Chen, Y., Li, L., Long, L. & Ding, S. High cell-density cultivation of phenolic acid decarboxylase-expressing Escherichia coli and 4-vinylguaiacol bioproduction from ferulic acid by whole-cell catalysis. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 93, 2415–2421 (2018).

Choi, Y. J. & Lee, S. Y. Microbial production of short-chain alkanes. Nature 502, 571–574 (2013).

Huijbers, M. M., Zhang, W., Tonin, F. & Hollmann, F. Light-driven enzymatic decarboxylation of fatty acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13648–13651 (2018).

Rui, Z. et al. Microbial biosynthesis of medium-chain 1-alkenes by a nonheme iron oxidase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 18237–18242 (2014).

Rui, Z., Harris, N. C., Zhu, X., Huang, W. & Zhang, W. Discovery of a family of desaturase-like enzymes for 1-alkene biosynthesis. ACS Catal. 5, 7091–7094 (2015).

Dennig, A. et al. Oxidative decarboxylation of short-chain fatty acids to 1-alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 8819–8822 (2015).

Payne, K. A. et al. New cofactor supports α, β-unsaturated acid decarboxylation via 1, 3-dipolar cycloaddition. Nature 522, 497–501 (2015).

Beller, H. R. et al. Discovery of enzymes for toluene synthesis from anoxic microbial communities. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 451–457 (2018).

Claus, M. et al. Cyclopentadiene and Cyclopentene. in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, (Wiley, 2016).

Musser, M. T. Cyclohexanol and Cyclohexanone. in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, (Wiley, 2012).

Sato, K., Aoki, M. & Noyori, R. A” green” route to adipic acid: Direct oxidation of cyclohexenes with 30 percent hydrogen peroxide. Science 281, 1646–1647 (1998).

Lechner, H., Pressnitz, D. & Kroutil, W. Biocatalysts for the formation of three-to six-membered carbo- and heterocycles. Biotechnol. Adv. 33, 457–480 (2015).

Hammer, S. C., Marjanovic, A., Dominicus, J. M., Nestl, B. M. & Hauer, B. Squalene hopene cyclases are protonases for stereoselective Brønsted acid catalysis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 121–126 (2015).

Coelho, P. S., Brustad, E. M., Kannan, A. & Arnold, F. H. Olefin cyclopropanation via carbene transfer catalyzed by engineered cytochrome P450 enzymes. Science 339, 307–310 (2013).

Bordeaux, M., Tyagi, V. & Fasan, R. Highly diastereoselective and enantioselective olefin cyclopropanation using engineered myoglobin-based catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 1744–1748 (2015).

Brandenberg, O. F., Fasan, R. & Arnold, F. H. Exploiting and engineering hemoproteins for abiological carbene and nitrene transfer reactions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 47, 102–111 (2017).

Chen, K., Huang, X., Kan, S. J., Zhang, R. K. & Arnold, F. H. Enzymatic construction of highly strained carbocycles. Science 360, 71–75 (2018).

Jeschek, M. et al. Directed evolution of artificial metalloenzymes for in vivo metathesis. Nature 537, 661–665 (2016).

Lo, C., Ringenberg, M. R., Gnandt, D., Wilson, Y. & Ward, T. R. Artificial metalloenzymes for olefin metathesis based on the biotin-(strept) avidin technology. Chem. Commun. 47, 12065–12067 (2011).

Vougioukalakis, G. C. & Grubbs, R. H. Ruthenium-based heterocyclic carbene-coordinated olefin metathesis catalysts. Chem. Rev. 110, 1746–1787 (2010).

Turner, N. J. & O’Reilly, E. Biocatalytic retrosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 285–288 (2013).

Hönig, M., Sondermann, P., Turner, N. J. & Carreira, E. M. Enantioselective chemo- and biocatalysis: partners in retrosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 8942–8973 (2017).

Song, J. W. et al. Multistep enzymatic synthesis of long‐chain α, ω‐dicarboxylic and ω‐hydroxycarboxylic acids from renewable fatty acids and plant oils. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 2534–2537 (2013).

Cha, H. J. et al. Simultaneous enzyme/whole-cell biotransformation of C18 ricinoleic acid into (R)-3-hydroxynonanoic acid, 9-hydroxynonanoic acid, and 1, 9-nonanedioic acid. Adv. Synth. Catal. 360, 696–703 (2018).

Dennig, A. et al. Enzymatic oxidative tandem decarboxylation of dioic acids to terminal dienes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 3473–3477, (2016).

Wallace, S. & Balskus, E. P. Designer micelles accelerate flux through engineered metabolism in E. coli and support biocompatible chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 6023–6027 (2016).

Cortes-Clerget, M. et al. Bridging the gap between transition metal-and bio-catalysis via aqueous micellar catalysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 2169 (2019).

Zachos, I. et al. Photobiocatalytic decarboxylation for olefin synthesis. Chem. Commun. 51, 1918–1921 (2015).

Seo, J. H. et al. Engineering of Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase-based Escherichia coli biocatalyst for large scale biotransformation of ricinoleic acid into (Z)-11-(heptanoyloxy) undec-9-enoic acid. Sci. Rep. 6, 28223 (2016).

Jeschek, M., Gerngross, D. & Panke, S. Rationally reduced libraries for combinatorial pathway optimization minimizing experimental effort. Nat. Commun. 7, 11163 (2016).

Biermann, U., Bornscheuer, U., Meier, M. A., Metzger, J. O. & Schäfer, H. J. Oils and fats as renewable raw materials in chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 3854–3871 (2011).

Romero, P. A. & Arnold, F. H. Exploring protein fitness landscapes by directed evolution. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 866–876 (2009).

Turner, N. J. Directed evolution drives the next generation of biocatalysts. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 567–573 (2009).

Denard, C. A., Ren, H. & Zhao, H. Improving and repurposing biocatalysts via directed evolution. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 25, 55–64 (2015).

Bornscheuer, U. T., Hauer, B., Jaeger, K. E. & Schwaneberg, U. Directed evolution empowered redesign of natural proteins for the sustainable production of chemicals and pharmaceuticals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 36–40 (2019).

Qu, G., Li, A., Acevedo-Rocha, C. G., Sun, Z. & Reetz, M. T. The crucial role of methodology development in directed evolution of selective enzymes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201901491. 10.1002/anie.201901491

Zhou, Y., Wu, S. & Li, Z. Cascade biocatalysis for sustainable asymmetric synthesis: from biobased l‐phenylalanine to high‐value chiral chemicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 11647–11650 (2016).

Li, G. et al. Overriding traditional electronic effects in biocatalytic Baeyer–Villiger reactions by directed evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10464–10472 (2018).

Yu, J.-M. et al. Direct access to medium‐chain α, ω‐dicarboxylic acids by using a Baeyer–Villiger monooxygenase of abnormal regioselectivity. ChemBioChem 19, 2049–2054 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Faber, A. Dennig, and A. Schallmey for sharing the plasmids pET28a-OleT and pACYC-CamAB. T.R.W. thanks generous support from Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant SNF 200020_162348), the ERC advanced grant (the DrEAM, grant agreement No 694424) and the NCCR Molecular Systems Engineering. S.W. thanks the Federal Commission for Scholarships for Foreign Students for an ESKAS Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.R.W. and S.W. conceived and designed the project. S.W. and Y.Z. performed the experiments and analyzed the results. M.J. and D.G. designed RBS libraries in silico. T.R.W. supervised the whole project. S.W. and T.R.W. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Huimin Zhao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, S., Zhou, Y., Gerngross, D. et al. Chemo-enzymatic cascades to produce cycloalkenes from bio-based resources. Nat Commun 10, 5060 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13071-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13071-y

This article is cited by

-

Coupling metal and whole-cell catalysis to synthesize chiral alcohols

Bioresources and Bioprocessing (2022)

-

Unnatural biosynthesis by an engineered microorganism with heterologously expressed natural enzymes and an artificial metalloenzyme

Nature Chemistry (2021)

-

Engineering and emerging applications of artificial metalloenzymes with whole cells

Nature Catalysis (2021)

-

Photobiocatalytic synthesis of chiral secondary fatty alcohols from renewable unsaturated fatty acids

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.