Abstract

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have been recognized as compelling platforms for the development of miscellaneous applications because of their structural diversity and functional tunability. Here, we propose that the electrocatalytic properties could be well modified by incorporating missing linkers into the MOF. Theoretical calculations suggest the electronic structure of MOFs can be tuned by introducing missing linkers, which improves oxygen evolution reaction (OER) performance of the MOF. Inspired by these aspects, we introduced various missing linkers into a layered-pillared MOF Co2(OH)2(C8H4O4) (termed as CoBDC) to prepare missing-linker MOFs. Transmission electron microscope and synchrotron X-ray measurements confirmed that the missing linkers in the MOF could be introduced and well controlled by our strategy. The self-supported MOF nanoarrays with missing linkers of carboxyferrocene exhibit excellent OER performance with ultralow overpotential of 241 mV at 100 mA cm−2. This work opens a new prospect to develop efficient MOF-based electrocatalysts by introducing missing linkers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Developing efficient electrochemical conversion processes is of great significance for storing and utilizing renewable energy1. Electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction (OER) plays an essential role in many energy conversion technologies involving metal–air batteries, water splitting, and CO2 reduction2,3,4,5. Unfortunately, the efficiency of OER was limited by its sluggish kinetics and high over-potential. So, efficient electrocatalysts are highly required to facilitate OER effectively6. To date, noble metal catalysts including RuO2 and IrO2, have been recognized as effective electrocatalysts for OER7. Nevertheless, the large-scale application of noble metal catalysts was hindered by its high-cost and scarcity. Therefore, exploring new high-efficiency non-noble metal electrocatalysts for OER is of ongoing interest8. Although tremendous efforts have been devoted to developing cost-effective OER catalysts, current electrocatalysts still failed to satisfy the industrial requires. So, the development of non-noble metal electrocatalysts for OER with high catalytic activity and stability is still a challenge9.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), have served as the fascinating material platform with versatile applications including gas storage and separation10,11,12, drug delivery13, and catalysis14,15,16,17,18,19. Benefiting from their isolated active site, large surface area, and high porosity, MOFs have received broad research interest in the field of heterogeneous electrochemical catalysis20,21,22,23,24. Nevertheless, most of MOFs show intrinsic poor electric conductivity and electrocatalytic activity. Although there have been some methods, such as metal node engineering25,26, hydroxide ligands cooperate27, and lattice-strained MOF28 reported to regulate the electrocatalytic activity of MOFs, the directly use of MOFs as efficient OER catalysts is still in its infancy.

The electrocatalytic performance of solid materials is mainly reflected by the number of active sites, electronic conductivity, and the reaction energy barrier of the catalyst29. In addition to regulate the morphology and crystal structure of the catalyst, optimizing the electronic structure of catalytic metal is the most straightforward way to change intrinsic characteristics of catalysts such as electronic conductivity and the reaction energy barrier30. The electronic structure of MOFs is mainly affected by topological structure and coordination environment31. Owing to the high design flexibility of MOFs, the missing linkers can be controllably introduced into MOFs by partially substituting multicoordinating bridging linkers with nonbridging ligands to change their coordination environment without loss of crystallinity and porosity of materials32,33,34,35. So, incorporating missing linkers into MOFs provides a promising strategy to tailor electronic structure of MOFs36,37. This may open up new opportunities for regulating the electrocatalytic property of MOFs.

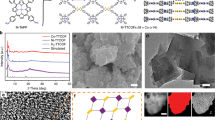

Therefore, we introduce missing linkers to regulate electronic structure of MOFs and report a universal strategy to enhance the OER activity of MOFs (Fig. 1). Theoretical results demonstrate that the electronic structure of CoBDC can be regulated effectively by incorporating missing linkers such as carboxyferrocene (Fc) into MOFs, changing the band gap and charge distribution thus optimizing adsorption strength for the reaction intermediates. In subsequent experiments, the MOFs with missing linkers exhibited an enhanced catalytic activity, validating our design.

Results

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

The layered-pillared MOF Co2(OH)2(C8H4O4) (named as CoBDC) constructed by the coordinated octahedrally divalent cobalt and terephthalic acid (H2BDC). The terephthalates are coordinated and pillared directly to the cobalt hydroxide layers and form a three-dimensional framework (Supplementary Fig. 1)38. owning to its unique structure and good stability25, CoBDC is used as an example to study the effects of missing linkers on its electronic structure. DFT reveals that the terephthalic acid in CoBDC can be repalced by missing linker of carboxyferrocene (Fc) and forms a new stable MOF named by CoBDC–Fc (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2). After introducing missing linkers, CoBDC–Fc generates new electronic states near the Fermi level, suggesting a more conductive electronic structure (Fig. 2b). The partial density of states (PDOS) showed that the generation of new electronic states near the Fermi level can be ascribed to the change of electronic structure of Co and O. 2D electron localization function (ELF) analysis showed that a larger ELF value around the Co atom in CoBDC–Fc compared with that of CoBDC can be observed (Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating a higher electron localization on Co in CoBDC-Fc (Fig. 2c).

Free energy difference (ΔG) for each elementary step was calculated to estimate the OER activity on different sites. The optimized pathways of various sites were shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. Based on the free energy diagram (Fig. 2d) of CoBDC, the energy barrier (∆G1 = 3.74 eV) for the formation of OH∗ is the rate-determining step on the Co site of bulk phase (Co1 in CoBDC–Fc), which is assigned to the weak adsorption energy of OH* (Supplementary Table 1). The Co in bulk phase of CoBDC–Fc showed similar activity with Co in bulk phase of CoBDC. After introducing missing linkers into CoBDC, the defect site (Co2 in CoBDC–Fc) generated and enhanced the adsorption energy of the OER intermediates. As a result, the rate-determining step for CoBDC–Fc is the oxidation of OH* to O* with a smaller energy barrier of 1.85 eV. The decrease of energy barrier after incorporating missing linkers into MOF catalyst implies that the unique electronic structure in the defect site of the MOF plays a vital role in improving OER activity.

Synthesis and characterization of missing-linker MOFs

In light of DFT results, Fc was introduced into CoBDC to construct MOFs containing missing linkers (named as “CoBDC–Fcx” where x = the molar ratio of Fc:BDC) by modulation approach. In order to improve the electric conductivity and mechanical stability of MOF, self-supported CoBDC nanoarrays (CoBDC–NF) were prepared by reacting H2BDC with Co(NO3)2·6H2O in the presence of nickel foam (NF) substrate. The appropriate amount of Fc was introduced into CoBDC nanoarrays to construct defective MOF arrays (CoBDC–Fc–NF). The ratio of BDC:Fc was about 6:1 in CoBDC-Fc0.17 and CoBDC–Fc–NF determined by the measurement of inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP–MS) (Supplementary Table 2). X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns showed that the crystal structure of CoBDC is identical with the previously reported Co2(OH)2(C8H4O4) MOFs (Supplementary Fig. 5)38. The targeted incorporation of missing linker defects led to the formation of highly crystalline CoBDC-Fc0.17 which have almost the same diffraction patterns as CoBDC. The morphologies of as-prepared materials were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Both CoBDC and CoBDC-Fc0.17 showed nanosheets morphologies (Supplementary Fig. 6). Employing NF as a substrate, CoBDC nanosheets can be uniformly grown on NF and form nanosheet array (Fig. 3a, b). After incorporating Fc as a modulator, CoBDC–Fc–NF shows similar morphology to CoBDC–NF (Fig. 3d, e). While CoBDC–Fc–NF was assembled by slightly thicker MOF nanosheets, compared to CoBDC–NF. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images further confirmed their nanosheet morphologies (Fig. 3c, f). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mappings demonstrate that the Fc can be uniformly incorporated into CoBDC nanosheets (Fig. 3g). The N2 sorption isotherms of as-prepared MOFs at 77 K showed that CoBDC–Fc0.17 had a smaller Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area (16.03 m2 g−1) than that of CoBDC (17.12 m2 g−1) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

In order to experimentally confirm the impact of introducing missing linkers on the electronic states of MOFs, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out to investigate the electronic structure of the active center. In the full range XPS spectra of CoBDC, the peaks of C1s, O1s, and Co 2p are detected. Introducing the Fc as modulator led to an obvious peak of Fe 2p in the XPS spectra of CoBDC–Fc0.17 (Supplementary Fig. 8). The Co 2p3/2 of CoBDC and CoBDC–Fc0.17 demonstrated that Co cation was bivalent Co2+ state (Fig. 4a). Compared with those of CoBDC, Co 2p3/2 and O1s in CoBDC–Fc0.17 have higher binding energy and broadened peaks, indicating the change of active center coordination environment caused by the introduction of missing linkers (Supplementary Fig. 9a)39. Furthermore, XPS valence band spectra were measured to investigate the electronic properties of the MOFs catalysts. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 9b, after introducing missing linkers, the valence band maximum energy of CoBDC–Fc0.17 blue shifts to the vacuum level at about 0.37 eV with respect to that of CoBDC (1.65 eV), suggesting that introducing missing linkers can effectively modulate the electronic structure of MOFs. Square resistance measurements proved that the conductivity of the MOF increased after introducing missing linkers (Supplementary Table 3).

To understand the local structures of Co2+ in CoBDC and CoBDC–Fc0.17, we performed Co K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). The observed X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra are shown in Fig. 4b. The sharp lines correspond to the electron transition from Co 1s to outer unoccupied 4p orbitals. The energy position of the pre-edge peak and white line peak for both CoBDC and CoBDC-Fc0.17 are about at 7708.2 and 7723.6 eV, respectively. The spectral profile is very similar to that of CoO, indicating average Co valence state of +240. In contrast, the peak intensity of CoBDC–Fc0.17 is slightly diminished relative to that of CoBDC, suggesting that introduction of the missing ligands changed the local coordination geometry of Co2+ ions41. The similar Co K-edge k3χ data of EXAFS oscillations are displayed from viewpoints of Cobalt (Fig. 4c), suggesting Co for CoBDC and CoBDC–Fc0.17 are in similar coordinated environments. Notably, CoBDC–Fc0.17 exhibits less amplitude oscillations, indicating the average coordination number of Co atom decreases after introducing missing linkers. To clarify the change of local coordination geometry of Co2+ ions observed in XANES, we performed the curve fitting of the Fourier transforms of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) for CoBDC and CoBDC-Fc0.17 (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Table 4). The curve fitting revealed that the Co–O distance of CoBDC–Fc0.17 (2.08 Å) is almost identical to that of CoBDC (2.07 Å). On the other hand, the coordination number of Co–O for CoBDC–Fc0.17 was 4.4, which is smaller than that of CoBDC (6.2). These observations suggest introducing the missing linkers generated unsaturated Co2+ sites, which is expected to work as active sites for the OER.

Electrocatalytic performance of missing-linker MOFs

Next, we sought to verify the electronic structure change of Co active center by introducing missing linkers to facilitate OER performance. The electrocatalytic performance of as-prepared MOFs was investigated with three-electrode system in alkaline condition (1 M KOH) by using commercially RuO2 as reference. CoBDC and CoBDC–Fc0.17 were deposited onto a glassy-carbon electrode with a loading of 0.35 mg cm−2. CoBDC–NF and CoBDC–Fc–NF were directly used as a self-supported electrode. The loading mass of CoBDC and CoBDC–Fc onto CoBDC–NF and CoBDC–Fc–NF was about 2 mg cm−2. The polarization curves with iR-compensation were recorded by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10, the CoBDC existed low OER performance with overpotential of 378 mV at 10 mA cm−2. After introducing missing linkers, CoBDC–Fc0.17 showed improved catalytic activity with overpotential of 291 mV at 10 mA cm−2 and smaller Tafel slope (61 mV dec−1). The direct growth of MOF on NF will enhance transport kinetics and electrical contact. As can be seen in Fig. 5a, CoBDC–NF showed excellent electrocatalytic property for OER with an overpotential of 318 mV at the large current density of 100 mA cm−2, which is better than that of the commercial catalyst RuO2 (349 mV). After introducing miss linkers (Fc), CoBDC–Fc–NF showed significantly enhanced OER activity with the ultralow overpotential of 178 mV to achieve 10 mA cm−2 which is 74 and 57 mV lower than that of CoBDC–NF and commercial RuO2 (Fig. 5b), respectively. Furthermore, very small overpotentials of 241 and 267 mV can drive a high current density of 100 and 500 mA cm−2 for the CoBDC–Fc–NF electrode which competes to the best OER electrocatalysts previously reported (Supplementary Table 5)42,43,44,45,46. Additionally, CoBDC–Fc–NF has a highest turnover frequency (TOF) of 0.034 S−1 at an overpotential of 250 mV, further demonstrating its improved OER performance (Supplementary Fig. 11). The CoBDC–Fc–NF also shows smaller Tafel slope of 51 mV dec−1 compared with CoBDC-NF (63 mV dec−1) and RuO2 (88 mV dec−1), indicating more superior OER reaction kinetics. The stability of CoBDC-Fc-NF was tested by chronopotentiometry and cyclic voltammetry (CV). As shown in Fig. 5d, CoBDC–Fc–NF exhibited strong durability in a prolonged chronopotentiometry test at a constant current density of 100 mA cm−2 for 80 h. After CV between 1.20 and 1.45 V for 2000 cycles, CoBDC–Fc–NF only showed slight degradation, demonstrating its high durability (Supplementary Fig. 12). Additionally, the morphology and crystal structure of CoBDC–Fc–NF showed limited changes after 10 h electrocatalysis at a constant current density of 100 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14). After 5 h electrocatalysis, the elemental composition of catalyst and chemical environment of Co had very little changes (Supplementary Fig. 15). XPS spectra of CoBDC–Fc–NF after 10 h electrocatalysis showed that the peak width and satellites intensity of Co 2p decreased slightly, indicating the formation of a small amount of Co3+ after long-time OER process (Supplementary Fig. 15)47,48. The peaks at binding energy of 779.8 and 795.0 eV are ascribed to Co3+ in CoOOH, confirming the formation of amorphous CoOOH during the long-time OER electrocatalytic process (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 15b)47,48,49. The limited changes in elemental composition and chemical environment of CoBDC–Fc–NF after 10 h OER stability test indicate the MOF to be the main component. Even so, the participation of CoOOH, widely known as an active species for OER electrocatalysis, cannot be excluded at this time.

The concentration of missing linkers can be controlled by varying the addition amount of Fc. A series of CoBDC–Fcx powders with different ratios of BDC:Fc were prepared. SEM images showed that after introducing Fc into CoBDC the original morphology of nanosheet basically remains (Supplementary Fig. 16). The high crystallinity of CoBDC–Fcx was evident from the XRD pattern, which was isostructural with CoBDC (Supplementary Fig. 17). Introducing Fc into CoBDC can obviously improve the electrocatalytic activity of MOFs (Supplementary Fig. 18). A doping ratio of 0.14 (Fc:BDC), exhibited optimal performance with an overpotential of 291 mV at 10 mA cm−2.

To demonstrate the universality of the missing linker engineering of MOF for OER, other monocarboxylic acid ligands including 4-nitrobenzoic acid (PNBA) and 4-carboxybenzaldehyde (PCBA) were used for preparing defective MOFs (CoBDC–PNBA, CoBDC–PCBA), which have the similar morphology with CoBDC (Supplementary Fig. 19). XRD pattern showed that CoBDC–PNBA and CoBDC–PCBA were isostructural with CoBDC (Supplementary Fig. 20). XPS showed that the Co 2p3/2 of CoBDC–PNBA and CoBDC–PCBA had higher binding energy and broadened peak than that of CoBDC (Supplementary Fig. 21a). Compared with that of CoBDC, the valence band maximum energy of CoBDC–PNBA and CoBDC–PCBA blue shifts to the vacuum level at about 1.60 and 1.48 eV, respectively, indicating the change of electronic structure of MOFs (Supplementary Fig. 21b). Encouraged by these results, we tested the OER performance of CoBDC–PNBA and CoBDC–PCBA. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 22, introduction of missing linkers significantly improved the catalytic properties. Moreover, CoBDC–PNBA and CoBDC–PCBA can grow in situ on NF to form uniform films (CoBDC–PNBA–NF, CoBDC–PCBA–NF) (Supplementary Fig. 23). The OER performance of CoBDC–PNBA–NF, CoBDC–PCBA–NF was apparently better than CoBDC–NF with overpotentials of 212 and 209 mV at 10 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Figs. 24a and 25). The low Tafel slopes of CoBDC-PNBA-NF (56 mV dec−1) and CoBDC–PCBA–NF (62 mV dec−1) indicated favorable kinetic process (Supplementary Fig. 24b). These results further demonstrate that tuning the electronic structure of MOFs by introducing missing linkers can enhance the electrocatalytic activity.

To gain more insights into the outstanding catalytic activity of defective MOFs, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) techniques were used to investigate the kinetics of electrode reactions (Supplementary Fig. 26a). Introducing missing linkers into MOFs led to smaller charge-transfer resistance (Rct) for CoBDC-Fc-NF (2.21 Ω), CoBDC–PNBA–NF (4.95 Ω) and CoBDC–PCBA–NF (5.67 Ω) electrodes than that of CoBDC–NF electrodes (6.92 Ω), suggesting the lower activation energy for the reactions on MOFs with missing linkers (Supplementary Table 6). The electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) of as-prepared materials were also evaluated by the electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) (Supplementary Fig. 27). As seen in Supplementary Fig. 26b, the Cdl of the sample of CoBDC–Fc–NF, CoBDC–PNBA–NF, and CoBDC–PCBA–NF is even lower than that of CoBDC–NF, indicating less electroactive surface of defective MOFs films. However, better electrocatalytic performance of missing-linker MOFs confirms that activity enhancement should be attributed to the increase of intrinsic activity of active sites by introducing missing linkers, which is consistent with DFT results.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed a strategy to design efficient MOF electrocatalysts containing missing linkers. DFT predicted the regulation of electronic structure and OER activity in the MOF after introducing missing linkers. Subsequently, a series of MOFs with missing linkers can be successfully synthesized by modulation approach. The concentration of missing linkers can be well controlled by varying the addition amount of monocarboxylic acid. XPS and XAFS results verify the regulation of electronic structure after incorporating missing linkers into MOFs. The improved OER performance of missing-linkers MOFs is providing evidence that OER activity of MOFs can be indeed facilitated by modulating electronic structure via introducing missing linkers. Importantly, this study gives a new strategy to regulate the electronic structure of MOFs as high-efficiency electrocatalysts for potential applications.

Methods

Chemicals

Cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (98%), terephthalic acid (99%), ferrocenecarboxylic acid (98%), PNBA (99%), 4-carboxylbenzaldehyde (99%), NaOH (97%), and commercial RuO2 (99.9%) were purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Solvents were purchased from commercial sources. NF was ultrasonically washed with HCl solution (3 M) for 30 min.

Preparation of CoBDC–NF

Terephthalic acid (83 mg, 0.5 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL N,N- dimethylformamide (DMF). Then, 1 mL 0.4 M NaOH was added under stirring. The solution above was slowly mixed with 5 mL cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (145 mg, 0.5 mmol) DMF solution in a 30 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave with a piece of NF (1 cm × 3 cm) in it. After that, the Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave was heated for 15 h at 100 °C. The resulting MOF film on NF was washed with DMF and ethanol three times and dried naturally. The loading amount of the MOF on NF was determined to be about 2.1 mg cm−2.

Preparation of CoBDC–Fc–NF

Terephthalic acid (125 mg, 0.75 mmol) and ferrocenecarboxylic acid (23 mg, 0.1 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL DMF. Then, 1 mL 0.4 M NaOH was added under stirring. After that, the solution above was slowly mixed with 5 mL cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (218 mg, 0.75 mmol) DMF solution in a 30 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave with a piece of NF (1 cm × 3 cm) in it. The Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave was heated for 15 h at 100 °C. The resulting MOF film on NF was washed with DMF and ethanol three times and dried naturally. The loading amount of the MOF on NF was determined to be about 1.8 mg cm−2.

Preparation of CoBDC

Terephthalic acid (166 mg, 1 mmol) and cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (291 mg, 1 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL N,N-DMF, respectively. Then, the solution above was slowly mixed in a 30 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. After that, the Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave was heated for 12 h at 100 °C. The products were washed with DMF and methanol and dried at 60 °C for 12 h.

Preparation of CoBDC–Fcx

Terephthalic acid (166 mg, 1 mmol) and various amounts of ferrocenecarboxylic acid were dissolved in 5 mL DMF. Then, the solution above was slowly mixed with 5 mL cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (290 mg, 1 mmol) DMF solution in a 30 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. After that, the Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave was heated for 12 h at 100 °C. The resulting products were washed with DMF and ethanol three times and dried naturally. The content of Co and Fe was measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP–MS) to determine the ratio of terephthalic acid and ferrocenecarboxylic acid.

Preparation of RuO2–NF

5 mg RuO2, 950 μL ethanol and 50 μL Nafion were mixed and dispersed by ultrasonic for 30 min. 200 μL RuO2 ink was depositing onto NF (1 cm × 0.5 cm) with a loading amount of 2 mg cm−2.

Preparation of CoBDC–PNBA

Terephthalic acid (166 mg, 1 mmol) and PNBA (17 mg, 0.1 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL DMF. Then, the solution above was slowly mixed with 5 mL cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (290 mg, 1 mmol) DMF solution in a 30 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. After that, the Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave was heated for 12 h at 100 °C. The resulting products were washed with DMF and ethanol three times and dried naturally.

Preparation of CoBDC–PCBA

Terephthalic acid (166 mg, 1 mmol) and 4-carboxylbenzaldehyde (15 mg, 0.1 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL DMF. Then, the solution above was slowly mixed with 5 mL cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (290 mg, 1 mmol) DMF solution in a 30 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. After that, the Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave was heated for 12 h at 100 °C. The resulting products were washed with DMF and ethanol three times and dried naturally.

Preparation of CoBDC–PNBA–NF

Terephthalic acid (83 mg, 0.5 mmol) and PNBA (17 mg, 0.1 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL DMF. Then, the solution above was slowly mixed with 5 mL cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (145 mg, 0.5 mmol) DMF solution in a 30 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave with a piece of NF (1 cm × 3 cm) in it. After that, the Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave was heated for 12 h at 100 °C. The resulting MOF film on NF was washed with DMF and ethanol three times and dried naturally. The loading amount of the MOF on NF was determined to be about 1.9 mg cm−2.

Preparation of CoBDC–PCBA–NF

Terephthalic acid (83 mg, 0.5 mmol) and 4-carboxylbenzaldehyde (15 mg, 0.1 mmol) were dissolved in 5 mL DMF. Then, the solution above was slowly mixed with 5 mL cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (145 mg, 0.5 mmol) DMF solution in a 30 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave with a piece of NF (1 cm × 3 cm) in it. After that, the Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave was heated for 12 h at 100 °C. The resulting MOF film on NF was washed with DMF and ethanol three times and dried naturally. The loading amount of the MOF on NF was determined to be about 1.9 mg cm−2.

Characterization

Powder XRD was measured on Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer with Cu Kα X-ray source (λ = 1.540598 Å). SEM images were measured with a Hitachi SU8010 system. TEM images were taken on a JEM-1400Plus TEM. STEM and EDX mapping images were recorded from a JEOL JEM-ARM200F equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer, operating at 200 kV. XPS were performed on a VG Scientific ESCALAB 250 instrument. X-ray absorption spectra were collected at the BL14B2 beamline, SPring-8. in transmission mode under ambient conditions, using a Si (311) double crystal monochromator for Co K-edge. The data were processed with IFEFFIT50. Fourier transformation was k3-weighted in the k range from 2.9 to 11.7 Å–1. Gas sorption isotherms measurements were measured with a Micromeritics 3Flex Version 4.02 instrument. ICP–MS data were obtained from Thermo Scientific iCAP RQ instrument. Square resistance was measured with a FT-331 Series four-probe resistance ratio test instrument.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were performed in a three-electrode system controlled by a CHI 760E electrochemistry workstation. The Ag/AgCl and platinum plate electrode were used as the reference and counter electrode respectively. The measured potentials were converted vs. RHE, ERHE = EAg/AgCl + 0.197 + 0.059 × pH. The MOF nanoarrays were directly used as a working electrode. LSV curves were recorded at a scan rate of 2 mV/s. The potential in the LSV polarization curves were corrected for iR losses. The ECSA were investigated by double-layer capacitance (Cdl) in the potential range from 0.82 to 0.94 V vs. RHE. EIS were measured in a frequency range from 105 to 0.01 Hz at 1.45 V vs. RHE with 5 mV amplitude. The TOF was calculated by the equation: TOF = (J × A)/(4 × F × m), where J represents the current density (A cm−2) at an overpotential of 250 mV, A and m represent the area of the electrode and the number of moles of the active materials.

Computation method

All spin-polarized density-functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)51. Electron–ion interactions were described using standard PAW potentials52. For the electron–electron exchange and correlation functional was described through the generalized gradient approximation of Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE)53. A plane wave cutoff energy of 520 eV was applied in our calculations. Due to insufficient consideration of the on-site Columbic repulsion, between Co d electrons, the GGA + U approach was used with U−J = 4.0 for the Co atoms54,55.

To study the mechanism of OERs, a (3 × 2 × 2) supercell containing 264 atoms is used. The Brillouin-zone integrations were performed using the Gamma-point-only grid during the optimization. The iterative process considered was convergences, when the force on the atom was <0.02 eV Å−1 and the energy change was <10–5 eV per atom. The Gibbs free energy of each elementary step was calculated as

where ΔE is the reaction energy calculated by the DFT method. ΔZPE and ΔS are the changes in zero-point energies and entropy during the reaction, respectively56.

Data availability

Full data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information, as well as from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: Insights into materials design. Science 355, eaad4998 (2017).

Guo, C. X. et al. Engineering high-energy interfacial structures for high-performance oxygen-involving electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 8539–8543 (2017).

Roger, I., Shipman, M. A. & Symes, M. D. Earth-abundant catalysts for electrochemical and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0003 (2017).

Urbain, F. et al. A prototype reactor for highly selective solar-driven CO2 reduction to synthesis gas using nanosized earth-abundant catalysts and silicon photovoltaics. Energ. Environ. Sci. 10, 2256–2266 (2017).

Cai, P. W., Huang, J. H., Chen, J. X. & Wen, Z. H. Oxygen-containing amorphous cobalt sulfide porous nanocubes as high-activity electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction in an alkaline/neutral medium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 4858–4861 (2017).

Suen, N. T. et al. Electrocatalysis for the oxygen evolution reaction: recent development and future perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 337–365 (2017).

Xia, B. Y. et al. A metal-organic framework-derived bifunctional oxygen electrocatalyst. Nat. Energy 1, 15006 (2016).

Zhang, L. Z. et al. Graphene defects trap atomic Ni species for hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Chem 4, 285–297 (2018).

Tahir, M. et al. Electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction for energy conversion and storage: a comprehensive review. Nano Energy 37, 136–157 (2017).

Carrington, E. J. et al. Solvent-switchable continuous-breathing behaviour in a diamondoid metal-organic framework and its influence on CO2 versus CH4 selectivity. Nat. Chem. 9, 882–889 (2017).

Trickett, C. A. et al. The chemistry of metal-organic frameworks for CO2 capture, regeneration and conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17045 (2017).

Islamoglu, T. et al. Postsynthetic tuning of metal-organic frameworks for targeted applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 805–813 (2017).

Cui, Y. J. et al. Metal-organic frameworks as platforms for functional materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 483–493 (2016).

Yang, Q. H., Xu, Q. & Jiang, H. L. Metal-organic frameworks meet metal nanoparticles: synergistic effect for enhanced catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 4774–4808 (2017).

Wu, C. D. & Zhao, M. Incorporation of molecular catalysts in metal-organic frameworks for highly efficient heterogeneous catalysis. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605446 (2017).

Huang, Y. B., Liang, J., Wang, X. S. & Cao, R. Multifunctional metal-organic framework catalysts: synergistic catalysis and tandem reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 126–157 (2017).

Drake, T., Ji, P. F. & Lin, W. B. Site isolation in metal-organic frameworks enables novel transition metal catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2129–2138 (2018).

Chen, L.-F. & Xu, Q. Converting MOFs into amination catalysts. Science 358, 304–305 (2017).

Ji, S. F. et al. Atomically dispersed ruthenium species inside metal-organic frameworks: combining the high activity of atomic sites and the molecular sieving effect of MOFs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 4271–4275 (2019).

Morozan, A. & Jaouen, F. Metal organic frameworks for electrochemical applications. Energ. Environ. Sci. 5, 9269–9290 (2012).

Miner, E. M. et al. Electrochemical oxygen reduction catalysed by Ni3(hexaiminotriphenylene)2. Nat. Commun. 7, 10942 (2016).

Hod, I. et al. A porous proton-relaying metal-organic framework material that accelerates electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 6, 8304 (2015).

Kornienko, N. et al. Metal-organic frameworks for electrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 14129–14135 (2015).

Su, X. Z. et al. Operando spectroscopic identification of active sites in NiFe Prussian blue analogues as electrocatalysts: activation of oxygen atoms for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11286–11292 (2018).

Zhao, S. L. et al. Ultrathin metal-organic framework nanosheets for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Nat. Energy 1, 1–10 (2016).

Li, F. L., Shao, Q., Huang, X. Q. & Lang, J. P. Nanoscale trimetallic metal-organic frameworks enable efficient oxygen evolution electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 1888–1892 (2018).

Lu, X. F. et al. An alkaline-stable, metal hydroxide mimicking metal-organic framework for efficient electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 8336–8339 (2016).

Cheng, W. R. et al. Lattice-strained metal-organic-framework arrays for bifunctional oxygen electrocatalysis. Nat. Energy 4, 115–122 (2019).

Liu, Y. W., Xiao, C., Huang, P. C., Cheng, M. & Xie, Y. Regulating the charge and spin ordering of two-dimensional ultrathin solids for electrocatalytic water splitting. Chem 4, 1263–1283 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. Metal surface and interface energy electrocatalysis: fundamentals, performance engineering, and opportunities. Chem 4, 2054–2083 (2018).

Dolgopolova, E. A. et al. Electronic properties of bimetallic metal-organic frameworks (MOFs): tailoring the density of electronic states through MOF modularity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5201–5209 (2017).

Slater, B., Wang, Z. R., Jiang, S. X., Hill, M. R. & Ladewig, B. P. Missing linker defects in a homochiral metal-organic framework: tuning the chiral separation capacity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18322–18327 (2017).

Yuan, S. et al. Thermodynamically guided synthesis of mixed-linker Zr-MOFs with enhanced tunability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6636–6642 (2016).

Wu, H. et al. Unusual and highly tunable missing-linker defects in zirconium metal-organic framework UiO-66 and their important effects on gas adsorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10525–10532 (2013).

Fang, Z. L. et al. Structural complexity in metal-organic frameworks: simultaneous modification of open metal sites and hierarchical porosity by systematic doping with defective linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9627–9636 (2014).

Shearer, G. C. et al. Defect engineering: tuning the porosity and composition of the metal-organic framework UiO-66 via modulated synthesis. Chem. Mater. 28, 3749–3761 (2016).

De Vos, A., Hendrickx, K., Van der Voort, P., Van Speybroeck, V. & Lejaeghere, K. Missing linkers: an alternative pathway to UiO-66 electronic structure engineering. Chem. Mater. 29, 3006–3019 (2017).

Huang, Z. L. et al. Ab-initio XRPD crystal structure and giant hysteretic effect (H-c = 5.9 T) of a new hybrid terephthalate-based cobalt(II) magnet. Chem. Mater. 12, 2805–2812 (2000).

Daheron, L. et al. Electron transfer mechanisms upon lithium deintercalation from LiCoO2 to CoO2 investigated by XPS. Chem. Mater. 20, 583–590 (2008).

Wi, S. C. et al. Electronic structure of Zn1-xCoxO using photoemission and x-ray absorption spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 4233–4235 (2004).

de Groot, F., Vanko, G. & Glatzel, P. The 1s x-ray absorption pre-edge structures in transition metal oxides. J. Phys.-Condens. Mater. 21, 104207 (2009).

Liu, Y. et al. Valence engineering via selective atomic substitution on tetrahedral sites in spinel oxide for highly enhanced oxygen evolution catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8136–8145 (2019).

Cai, Z. et al. Single-crystalline ultrathin Co3O4 nanosheets with massive vacancy defects for enhanced electrocatalysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1701694 (2018).

Wu, T. et al. Iron-facilitated dynamic active-site generation on spinel CoAl2O4 with self-termination of surface reconstruction for water oxidation. Nat. Catal. 2, 763–772 (2019).

Li, P. S. et al. Boosting oxygen evolution of single-atomic ruthenium through electronic coupling with cobalt-iron layered double hydroxides. Nat. Commun. 10, 1711 (2019).

Wang, D. et al. Atomic and electronic modulation of self-supported nickel-vanadium layered double hydroxide to accelerate water splitting kinetics. Nat. Commun. 10, 3899 (2019).

McIntyre, N. S. & Cook, M. G. X-ray photoelectron studies on some oxides and hydroxides of cobalt, nickel, and copper. Anal. Chem. 47, 2208–2213 (1975).

Schenck, C. V., Dillard, J. G. & Murray, J. W. Surface analysis and the adsorption of Co(II) on goethite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 95, 398–409 (1983).

Yang, L. et al. Cathodic electrochemical activation of Co3O4 nanoarrays: a smart strategy to significantly boost the hydrogen evolution activity. Chem. Commun. 54, 2150–2153 (2018).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid–metal-amorphous–semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Liao, P., Keith, J. A. & Carter, E. A. Water oxidation on pure and doped hematite (0001) surfaces: prediction of Co and Ni as effective dopants for photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 13296–13309 (2012).

Alidoust, N., Lessio, M. & Carter, E. A. Cobalt (II) oxide and nickel (II) oxide alloys as potential intermediate-band semiconductors: a theoretical study. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 025102 (2016).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Trends in the exchange current for hydrogen evolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, J23–J26 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0108300), Thousand Youth Talents Plan of China and Guangdong Province, Hundred Youth Talents Program of Hunan, Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Program (2017XK2026), Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation project (JCYJ20180307151313532), The 100 Talents Plan Foundation of Sun Yat-sen University, the Program for Guangdong Introducing Innovative and Entrepreneurial Teams (2017ZT07C069), and the NSFC Projects (21872174, 21821003, 201875287, 21890380). The synchrotron radiation experiments were performed at the BL14B2 of SPring-8 with the approval of JASRI (Proposal No. 2018B1728).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.X. and G.L. designed the project. Z.X. and Y.L. performed the syntheses and electrochemical tests. Q.L. carried out the TEM characterizations. K.L. and M. Liu performed the DFT calculations. N.O., H. Kobayashi, M. Li and H. Kitagawa. tested and analyzed the XANES and EXAFS. Z.X., G.L., C.-Y.S. and M. Liu prepared the manuscript. Z.X., K.L., H. Kobayashi, M. Liu, and G.L. proposed mechanism investigation and wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in the discussion of experimental and calculations results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, Z., Liu, K., Liu, Q. et al. Missing-linker metal-organic frameworks for oxygen evolution reaction. Nat Commun 10, 5048 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13051-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13051-2

This article is cited by

-

Nitro-functionalized Fe-MOFs for lithium-sulfur batteries

Ionics (2024)

-

Emerging Atomically Precise Metal Nanoclusters and Ultrasmall Nanoparticles for Efficient Electrochemical Energy Catalysis: Synthesis Strategies and Surface/Interface Engineering

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2024)

-

Enhanced carbon capture with motif-rich amino acid loaded defective robust metal-organic frameworks

Nano Research (2024)

-

Core—shell Prussian blue analogues derived from metal-organic frameworks as efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction

Nano Research (2023)

-

The Renaissance of Ferrocene-Based Electrocatalysts: Properties, Synthesis Strategies, and Applications

Topics in Current Chemistry (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.