Abstract

High-pressure synthesis in diamond anvil cells can yield unique compounds with advanced properties, but often they are either unrecoverable at ambient conditions or produced in quantity insufficient for properties characterization. Here we report the synthesis of metallic, ultraincompressible (K0 = 428(10) GPa), and very hard (nanoindentation hardness 36.7(8) GPa) rhenium nitride pernitride Re2(N2)(N)2. Unlike known transition metals pernitrides Re2(N2)(N)2 contains both pernitride N24− and discrete N3− anions, which explains its exceptional properties. Re2(N2)(N)2 can be obtained via a reaction between rhenium and nitrogen in a diamond anvil cell at pressures from 40 to 90 GPa and is recoverable at ambient conditions. We develop a route to scale up its synthesis through a reaction between rhenium and ammonium azide, NH4N3, in a large-volume press at 33 GPa. Although metallic bonding is typically seen incompatible with intrinsic hardness, Re2(N2)(N)2 turned to be at a threshold for superhard materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the approach formulated by Yeung et al.1, the design of novel superhard materials should be based on the combination of a metal with high valence electron density with the first-row main-group elements, which form short covalent bonds to prevent dislocations. This conclusion was based on the synthesis of hard borides, such as OsB22, ReB23,4,5, FeB46, or WB47, whose crystal structures possess covalently bonded boron networks. Similar to boron, nitrogen as well can form covalent nitrogen–nitrogen bonds, but there are several factors, which make it difficult to synthesize nitrogen-rich nitrides. The large bond enthalpy of the triply bound N2 molecule (941 kJ·mol−1)8 makes this element generally unreactive. In many reactions the activation barrier for N2 bond breaking requires temperatures, which are higher than the decomposition temperatures of the target phases. MNx compounds with x > 1 are rarely available via direct nitridation reactions or ammonothermal syntheses9,10. Therefore, binary M-N systems are often limited to interstitial metal-rich nitrides. Usually, they are less compressible and have higher bulk moduli in comparison with pure metals due to the increasing repulsion between metal and nitrogen atoms, whereas their shear moduli are not always much different from those of metals.

Application of pressure is one way to increase the chemical potential of nitrogen and to stabilize nitrogen-rich phases11. Several transition metal dinitrides, PtN212, PdN213, IrN214, OsN214, TiN215, RhN216, RuN217, CoN218, and FeN219, containing covalently bound dinitrogen units were recently synthesized in laser-heated diamond anvil cells (LHDACs) via reactions between elemental metal and nitrogen in a pressure range of 40–80 GPa. Although LHDAC is an efficient method to study high-pressure chemical reactions, it is challenging to scale up the synthesis. The search for suitable synthetic strategies, which would enable an appropriate reaction to be realized in a large volume press (LVP) instead of a LHDAC, is an important challenge for high-pressure chemistry and materials sciences. In this study, focusing on the high-pressure synthesis of nitrogen-rich phases in the Re-N system and the development of new synthetic strategies, we resolved this problem for a rhenium nitride ReN2 with unusual crystal chemistry and unique properties.

Direct reactions between rhenium and nitrogen were studied by Friedrich et al.20, who synthesized two interstitial rhenium nitrides Re3N at 13 GPa and 1700 K, and Re2N at 20 GPa and 2000 K. Both compounds have exceptionally large bulk moduli exceeding 400 GPa (as measured upon compression in a non-hydrostatic medium21), but only moderate shear moduli as expected for interstitial compounds22. Kawamura et al.23 reported synthesis of ReN2 with MoS2 structure type (m-ReN2) in a metathesis reaction between Li3N and ReCl5 at 7.7 GPa. Subsequently, Wang et al.21 suggested, based on the first-principle calculations, that m-ReN2 is unstable and ‘real stoichiometric’ ReN2 should have monoclinic C2/m symmetry and transform to the tetragonal P4/mbm phase above 130 GPa. However, this suggestion has not been proven experimentally as yet. Recently Bykov et al. reported a novel inclusion polynitrogen compound ReN8·xN2 synthesized from elements at 106 GPa24, but the region of ~35–100 GPa still remains completely unexplored for the Re-N system.

Here, we report the high-pressure synthesis of an ultraincompressible metallic hard compound ReN2 via reactions between rhenium and nitrogen or ammonium azide at pressures of 33–86 GPa. The usage of a solid nitrogen precursor NH4N3 allows to scale up the synthesis of ReN2 in the large volume press.

Results

Synthesis of Re2(N2)(N)2 in a laser-heated diamond anvil cell

We have studied chemical reactions between Re and nitrogen and other reagents, such as sodium azide NaN3 and ammonium azide NH4N3, in LHDACs in a range of 29–86 GPa at temperatures of 2000–2500 K (Table 1, Experiments #1 through #6). The reactions products typically contained numerous single-crystalline grains of several rhenium nitride phases (Table 1), which were identified using synchrotron single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 1–3).

A direct reaction between Re and N2 (Table 1) resulted in the synthesis of three rhenium nitrides ReN2, Re2N, and ReN0.6, two of which (ReN2 and ReN0.6) have never been observed before. The third phase identified in these experiments, Re2N (P63/mmc), has previously been reported20. After a stepwise decompression of the sample obtained in Experiment #1 down to the ambient pressure, all of the three phases (ReN2, ReN0.6, Re2N) were found to remain intact even after being exposed to atmospheric oxygen and moisture for several months. Crystal structure analysis of ReN0.6 showed that it has a defect WC structure type (space group P\(\bar 6\)m2) (for details on ReN0.6 see Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3, Supplementary Table 4).

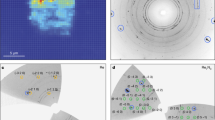

Analysis of the crystal structure of ReN2 revealed its unusual crystal-chemistry. Figure 1 shows the crystal structure of ReN2, which is built of distorted ReN7 capped trigonal prisms (Fig. 1d) and contains both N–N units (dumbbells) (Fig. 1f) and discrete N atoms (N2) (Fig. 1e) in an atomic ratio 1:1. The N1–N1 dumbbells are located in a trigonal antiprism formed by Re atoms (Fig. 1f), while discrete N2 atoms have a tetrahedral coordination by Re (Fig. 1e). The N1–N1 bond length (dN1-N1 = 1.412(16) Å at ambient conditions) suggests that the N2 unit should be considered as a pernitride anion N24−. Therefore, ReN2 is a rhenium nitride pernitride and its crystal-chemical formula is Re+V2[N−II2][N−III]2. In the following discussion we interchangeably use both empirical formula ReN2 and crystal-chemical formula for this compound.

Fragments of the crystal structure of Re2(N2)(N)2 at ambient conditions. Re atoms–grаy, N1 atoms–blue, N2 atoms–red. ReN2 crystallizes in the space group P21/c (No. 14) with a = 3.6254(17), b = 6.407(7), c = 4.948(3) Å, β = 111.48(6)°. Rhenium and nitrogen atoms occupy Wyckoff Positions 4e: Re [0.35490(11), 0.34041(8), 0.19965(8)], N1 [0.194(2), 0.038(2), 0.311(19)], N2 [0.259(3), 0.6381(18), 0.024(2)]. Full crystallographic information is given in the supplementary crystallographic information file and in the Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. a The projection of the crystal structure along the b-axis. b, c Fragments of the crystal structure of ReN2 showing how ReN7 polyhedra are connected with each other. d Separate ReN7 coordination polyhedron. e Coordination of N2 atoms. f Coordination of N1–N1 dumbbells

Compressibility of Re2(N2)(N)2

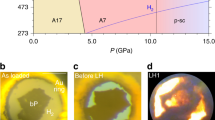

The compressibility of ReN2 was measured on the sample #2 (Table 1), which was synthesized at 49 GPa, then decompressed down to ambient conditions, and re-loaded into another DAC with a neon pressure-transmitting medium, which provides much better hydrostaticity of the sample environment than nitrogen25. The sample was first characterized using single-crystal XRD at ambient conditions. On compression, the lattice parameters were extracted from the powder XRD data (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Figs. 4-6; Supplementary Table 5). The pressure-volume dependence was described using the third-order Birch–Murnaghan equation of state26 with the following fit parameters: V0 = 107.21(4) Å3, K0 = 428(10) GPa, K’ = 1.6(5). Figure 2c shows a plot of correlated values of K0 and K’ to different confidence levels. The bulk modulus K0 lies within the range of 410–447 GPa at the 99.73% confidence level. Thus, K0 of ReN2 is larger than that of any compound in the Re-N system and is comparable to that of diamond (K0 = 440 GPa) and IrN2 (K0 = 428(12) GPa)14. Among very incompressible pernitrides of transition metals, ReN2 is the only compound, in which the metal atom has oxidation state (+V) higher than (+IV). The enhancement of the bulk modulus of ReN2 in comparison to OsN2, PtN2, and TiN2 is therefore in agreement with the general trend, that the bulk modulus of a compound increases with an increase of the product of formal charges of anions and cations19,27.

Physical propeties of Re2(N2)(N)2. a Pressure-dependence of the unit-cell volume of ReN2. The solid line shows the fit of the third- order Birch–Murnaghan EoS to the experimental data. b Normalized lattice parameters of ReN2. Black squares a/a0, red circles–b/b0, blue triangles–c/c0, where a0, b0, c0 are the lattice parameters at ambient conditions. c Plot of the correlated values of K0 and K0′ to different confidence levels of 68.3%, 95.4%, and 99.73%, respectively. d An F-f plot based on Birch–Murnaghan EoS. Dashed lines indicate expected behavior of data points for certain K0′ values. Uncertainties were calculated by propagation of experimental uncertainties in the unit cell volume. e Averaged indentation load-displacement data for Re (blue squares) and for ReN2 (red circles). The error bars correspond to the standard deviation between 16 single measurements at different locations. f Temperature dependence of the electrical resistance of the ReN2 sample at ambient pressure. If error bars are not shown, they are smaller than the symbol size

Search for solid nitrogen precursor

More detail characterization of physical properties of ReN2, such as hardness, electrical conductivity, etc. require a sample to be at least a few tens of microns in size that is much larger than can be synthesized in a LHDAC. The large volume press technique enables the synthesis of such a sample, but precludes from using N2 as a reagent. First, the amount of nitrogen, which can be sealed in a capsule along with Re, is insufficient for the desired reaction yield; second, unavoidable deformation of the capsule upon compression may potentially lead to the loss of nitrogen. Therefore, a solid source of nitrogen had to be found and we tested sodium and ammonium azides, NaN3 and NH4N3, as potential precursors in LHDACs (Experiments #5, #6, Table 1) (for a discussion regarding the choice of the solid reagents see Supplementary Note 4). The experiment with NaN3 (Experiment #5) did not result in the synthesis of ReN2. The major product of the reaction was NaReN2 (Supplementary Fig. 7), whose lattice parameters turned out to be very close to those reported for m-ReN2 by Kawamura et al.23, that might suggest that the material described in ref. 23 as rhenium nitride indeed could be a different compound (for a related discussion see Supplementary Note 4). The experiment in LHDAC with NH4N3 as a source of nitrogen resulted in the synthesis of ReN2 among other products (Experiment #6, Table 1).

Synthesis of Re2(N2)(N)2 in a large volume press

Based on results of this experiment in DAC, we explored a possibility to scale up the synthesis of ReN2 in a multianvil LVP at 33 GPa and 2273 K via a reaction between rhenium and ammonium azide (Experiment #7, Supplementary Note 5, Supplementary Fig. 8). The product of the reaction was a mixture of Re2N and ReN2. Each phase was separated (Supplementary Fig. 9) and characterized using single-crystal X-ray diffraction. A phase-pure polycrystalline sample of ReN2 (70 × 60 × 50 μm3), which was synthesized in the LVP, was used for nanoindentation hardness and electrical resistance measurements (Supplementary Fig. 10). Nanoindentation was performed using a nanoindenter equipped with Berkovich diamond tip and featuring continuous stiffness measurement capabilities. The average hardness and Young’s modulus measured between 200 and 400 nm depths are 36.7(8) GPa and 493(14) GPa, respectively (Fig. 2e, Table 2). The hardness approaching 40 GPa, a threshold for superhard materials, and extreme stiffness comparable with diamond makes mechanical properties of ReN2 exceptional in the row of metal nitrides. Due to the directional N–N bonding, the hardness of ReN2 is higher than that of known interstitial transition metal nitrides (δ-NbN –20 GPa, HfN –19.5 GPa, ZrN –17.4 GPa28, CrN −17 GPa1 etc.). Most transition metal pernitrides MN2 that are metastable at ambient conditions are expected to be very hard compounds too, however they were never obtained in a quantity sufficient for the hardness measurements29,30.

The electrical resistance of ReN2 as a function of temperature was measured at ambient pressure on a sample with the dimensions of about 70 × 60 × 50 μm3. The results of the measurements in the range of 150 K to 400 K are shown in Fig. 2f. Electrical resistivity of metals increases with temperature and this is the case for ReN2. The shape of the resistance–temperature curve (Fig. 2f) is reproducible as confirmed in a number of independent measurements on the same sample with re-glued electrical contacts.

Theoretical calculations

To confirm the experimentally observed peculiarities of ReN2 and to gain deeper insights into the mechanical and electronic properties of this compound, we performed theoretical calculations based on the density functional theory. First, we considered the crystal structure of ReN2. We carried out the full structure optimization for the compound at ambient pressure and found that calculations and experiment are in very close agreement (Supplementary Table 2). Calculated elastic constants for ReN2 (Table 3) fulfill the mechanical stability conditions31, and calculated phonon dispersion relations (Fig. 3a) show only real frequencies confirming its dynamic stability. Theoretically calculated N1–N1 vibrational frequency form a localized band giving rise to a peak of the phonon density of states at ~1031 cm−1. This vibrational behavior is similar to other pernitrides12,15,32. The metallic nature of the material confirmed by our calculations of the electronic density of states (DOS) (Fig. 3c). Calculated vibrational and electronic properties of N1–N1 unit confirm that it is a pernitride anion N24−. On the contrary, electronic and vibrational properties of N2 atoms (Fig. 3a, c) are quite distinct from those of N1, providing strong support to the experimental observation of the crystal chemistry of ReN2, which is unique for transition metals pernitrides.

Discussion

The unique chemistry of the compound is essential for understanding its superior mechanical properties. The bulk modulus, calculated theoretically using Voigt-Reuss-Hill approximation (413.5 GPa)33 is in a good agreement with the experiment (428(10) GPa), confirming that ReN2 can be characterized as highly incompressible material. At the same time, the value of the Poisson coefficient is close to 0.25, and relatively high ratio between share and bulk elastic moduli indicates substantial degree of covalence in ReN2 chemical bonding. A direct calculation of the charge density map (Fig. 3b) confirms the expectation. One sees a formation of covalent bonds between two N1 atoms. It is of single bond character with very high degree of electron localization (Fig. 3d) typical for a pernitride anion N24− in other transition metal pernitrides,34 and incompressible N24− is supposed to contribute to very low compressibility of the materials. The covalent bond between Re and N2 atoms is formed by substantially less localized electrons (compare Fig. 3b and Fig. 3d). Indeed, measured temperature dependence of the electrical resistance (Fig. 2f) and the estimated resistivity (~4 × 10−6 Ω·m–16 × 10−6 Ω·m in a temperature range 150–400 K) are in agreement with the theoretical conclusion and the description of ReN2 as a metal. The formation of the covalent bonds between Re and N2 atoms indicates strong hybridization between the electronic states of the atoms. The calculated electronic DOS (Fig. 3c) shows the presence of the pseudogap between occupied, predominantly bonding states of Re and unoccupied non-bonding and anti-bonding states. According to Jhi et al.35, such features optimize electronic contribution to hardness enhancement in transition-metal carbonitrides, which can also explain very high hardness of ReN2. Thus, the formation of strong covalent bond between Re and N2 atoms, a unique feature of the material synthesized in this work in comparison with known transition metal pernitrides, appears to be essential for its spectacular mechanical and electronic properties. To summarize, in the present work we have synthesized a transition metal nitride ReN2 (Re+V2(N−II2)(N−III)2) with the unique crystal structure and outstanding properties. The structure with Re atoms in the high oxidation state +V features both discrete nitride and pernitride ions. A combination of the high electron density of the transition metal with interstitial nitride anions and covalently bound pernitride units makes this compound ultraincompressible and extremely hard at the same time. The developed method for scaling up the synthesis of ReN2 in a LVP using ammonium azide as a nitrogen precursor may be applied for producing nitrides of other transition metals. We demonstrated the complete route for materials development from screening experiments in diamond anvil cells to the synthesis of samples large enough for physical property measurements. It is not only our results per se that are important, but the fact that the development and synthesis of the new material was realized contrary to the established concepts and should encourage further theoretical and experimental works in the field.

Methods

Synthesis of Re-N phases in laser-heated diamond anvil cells

In all synthesis experiments a rhenium powder (Sigma Aldrich, 99.995%) was loaded into the sample chamber of a BX90 diamond anvil cell (Boehler–Almax anvils, 250-μm size). In four experiments the chamber was filled with nitrogen at 1.5 kbar that served as a pressure-transmitting medium and as a reagent. In two experiments, the chamber was filled either with ammonium azide NH4N3 or with sodium azide NaN3. Pressure was determined using the equation of state of rhenium36,37,38. The compressed sample was heated using the double-sided laser-heating system installed at the Bayerisches Geoinstitut (BGI), University of Bayreuth, Germany. Successful syntheses were performed at 40, 42, 49, 71, and 86 GPa at temperatures of 2200–2500 K (Table 1).

Synthesis of Re-N phases in the large-volume press

High-pressure synthesis was performed using a Kawai-type multi-anvil apparatus IRIS15, installed at the BGI39. The NH4N3 sample (0.5 mm thickness, 0.8 mm in diameter) was sandwiched between two layers of Re powder (0.1 mm thick, 0.8 mm in diameter) and between two tubes of dense alumina in a Re capsule, which also acted as a heater. The capsule was placed in a 5 wt% Cr2O3-doped MgO octahedron with a 5.7 mm edge that was used as the pressure medium. The assembly scheme is given in the Supplementary Fig. 8. Eight tungsten carbide cubes with 1.5 mm truncation edge lengths were used to generate high pressures. The assembly was pressurized at ambient temperature to 33 GPa, following the calibration given by Ishii et al.39 and then heated to ~2273(100) K within 5 min and immediately quenched after the target temperature was reached. The assembly was then decompressed during 16 h.

Synthesis of NH4N3

Ammonium azide, NH4N3 was obtained by the metathesis reaction between NH4NO3 (2.666 g, 33 mmol, Sigma-Aldrich, 99.0%) and NaN3 (2.165 g, 33 mmol, Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium, 99%) in a Schlenk tube. By heating from room temperature to 170 °C in a glass oven and annealing for 7.5 h at 170 °C and then for 12 h at 185 °C, NH4N3 precipitated at the cold end of the tube separated from NaNO3, which remained at the hot end during the reaction40.

Compressibility measurements

For the compressibility measurements the sample synthesized at 49 GPa and 2200 K (Experiment #2) was quenched down to ambient pressure and re-loaded into another diamond anvil cell. The sample chamber was then filled with Ne that served as a pressure-transmitting medium. A powder of gold (Sigma Aldrich, 99.99%) was placed into the sample chamber along with the sample and used as a pressure standard41. The sample was then compressed up to ~45 GPa in 13 steps. At each pressure point we have collected powder X-ray diffraction data.

Synchrotron X-ray diffraction

High-pressure single-crystal and powder synchrotron X-ray diffraction studies of the reaction products were performed at the beamlines P02.2 (DESY, Hamburg, Germany)42, ID15B (ESRF, Grenoble, France), and 13-IDD GSECARS beamline (APS, Argonne, USA). The following beamline setups were used. P02.2: λ = 0.29 Å, beam size ~2 × 2 μm2, Perkin Elmer XRD 1621 detector; ID15B: λ = 0.41, beam size ~10 × 10 μm2, Mar555 flat panel detector; GSECARS: λ = 0.2952 Å, beam size ~3 × 3 μm2, Pilatus CdTe 1 M detector. For the single-crystal XRD measurements samples were rotated around a vertical ω-axis in a range ±38°. The diffraction images were collected with an angular step Δω = 0.5° and an exposure time of 1 s/frame. For analysis of the single-crystal diffraction data (indexing, data integration, frame scaling and absorption correction) we used the CrysAlisPro software package. To calibrate an instrumental model in the CrysAlisPro software, i.e., the sample-to-detector distance, detector’s origin, offsets of goniometer angles, and rotation of both X-ray beam and the detector around the instrument axis, we used a single crystal of orthoenstatite ((Mg1.93Fe0.06)(Si1.93, Al0.06)O6, Pbca space group, a = 8.8117(2), b = 5.18320(10), and c = 18.2391(3) Å). The same calibration crystal was used at all the beamlines.

Powder diffraction measurements were performed either without sample rotation (still images) or upon continuous rotation in the range ±20°ω. The images were integrated to powder patterns with Dioptas software43. Le-Bail fits of the diffraction patterns were performed with the TOPAS6 software.

In-house X-ray diffraction

Ambient-pressure single-crystal XRD datasets were collected with a high-brilliance Rigaku diffractometer (Ag Kα radiation) equipped with Osmic focusing X-ray optics and Bruker Apex CCD detector in the BGI.

Structure solution and refinement

The structure was solved with the ShelXT structure solution program44 using intrinsic phasing and refined with the Jana 2006 program45. CSD-1897795 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from FIZ Karlsruhe via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Nanoindentation

Nanoindentation was performed using a Nanoindenter G200 platform (KLA-Tencor, Milpitas, CA, USA), equipped with a Berkovich diamond tip (Synton MDP, Nidau, Switzerland) and featuring the continuous stiffness based method (CSM)46. Each sample was indented at 16 different locations separated by a distance of at least 10 µm, so that their plastic zones did not overlap. For each measurement, loading was performed at a constant strain-rate of 0.025 s−1 up to a maximal indentation depth of at least 400 nm. A 2 nm large oscillation superimposed on the loading signal allowed continuously measuring the contact stiffness. The acquired data were evaluated using the Oliver–Pharr method47,48. To this purpose, the diamond punch geometry was calibrated from 1000 nm deep references measurements in fused silica and the machine frame stiffness value was refined so as to obtain a constant ratio between stiffness squared and load during indentation of the samples. The conversion of the reduced moduli to a uniaxial Young’s moduli was performed assuming a Poisson’s ratios of 0.24 and 0.29, respectively for ReN2 and Re49.

Temperature-dependent resistance measurements

The resistance of the sample was measured by four-probe method passing a constant DC 90 mA current through the sample and measuring both current and voltage drop across the sample. Temperature was measured using the S-type thermocouple.

Theoretical calculations

The ab initio electronic structure calculations of ReN2 (12 atoms), ReN (2 atoms), and ReNx (2 × 3 × 2 supercell) were performed using the all electron projector-augmented-wave (PAW) method50 as implemented in the VASP code51,52,53. Among the tested exchange-correlation potentials (PBE54, PBEsol55, AM0556) the PBEsol approximation has resulted into the best agreement between the derived experimental and theoretical equation of state. Convergence has been obtained with 700 eV energy cutoff for the plane wave basis and a (18 × 10 × 14) Monkhorst–Pack k-points57 type sampling of the Brillouin zone for ReN2. Gaussian smearing technique was chosen with smearing of 0.05 eV. The convergence criterion for the electronic subsystem has been chosen to be equal to 10−4 eV for two subsequent iterations, and the ionic relaxation loop within the conjugated gradient method was stopped when forces became of the order of 10−3 eV/Å. The elastic tensor Cij has been calculated from the total energy applying (+/−) 1% and 2% lattice distortions. The Born mechanical stability conditions have been verified using the elastic constants. The phonon calculations have been performed within quasiharmonic approximation at temperature T = 0 K using the finite displacement approach implemented into PHONOPY software58. Converged phonon dispersion relations have been achieved using a (3 × 3 × 3) supercell with 324 atoms and (5 × 5 × 5) Monkhorst–Pack k-point sampling.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. CSD-1897795 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from FIZ Karlsruhe via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures. The source data underlying Fig. 2a–f, and Supplementary Figs. 2 a, b are provided as a Source Data file. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction dataset for rhenium nitrides (experiment #2) at 3.5 GPa has been deposited to Figshare (https://figshare.com/) with the accession link https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8081582.

References

Yeung, M. T., Mohammadi, R. & Kaner, R. B. Ultraincompressible, superhard materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 46, 465–485 (2016).

Cumberland, R. W. et al. Osmium diboride, an ultra-incompressible, hard material. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 7264–7265 (2005).

Qin, J. et al. Is rhenium diboride a superhard material? Adv. Mater. 20, 4780–4783 (2008).

Dubrovinskaia, N., Dubrovinsky, L. & Solozhenko, V. L. Comment on ‘synthesis of ultra-incompressible superhard rhenium diboride at ambient pressure’. Science 318, 1550 (2007).

Chung, H.-Y. H.-Y. et al. Synthesis of ultra-incompressible superhard rhenium diboride at ambient pressure. Science 316, 436–439 (2007).

Gou, H. et al. Discovery of a superhard iron tetraboride superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 157002 (2013).

Mohammadi, R. et al. Tungsten tetraboride, an inexpensive superhard material. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 10958–10962 (2011).

Andersen, T., Haugen, H. K. & Hotop, H. Binding energies in atomic negative ions: III. J. Phys. Chem. 28, 1511–1533 (1999).

Richter, T. & Niewa, R. Chemistry of ammonothermal synthesis. Inorganics 2, 29–78 (2014).

Häusler, J. & Schnick, W. Ammonothermal synthesis of nitrides: recent developments and future perspectives. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 11864–11879 (2018)

Sun, W. et al. Thermodynamic routes to novel metastable nitrogen-rich nitrides. Chem. Mater. 29, 6936–6946 (2017).

Crowhurst, J. C. et al. Synthesis and characterization of the nitrides of platinum and iridium. Science 311, 1275–1278 (2006).

Crowhurst, J. C. et al. Synthesis and characterization of nitrides of iridium and palladium. J. Mater. Res. 23, 1–5 (2008).

Young, A. F. et al. Synthesis of novel transition metal nitrides IrN2 and OsN2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 155501 (2006).

Bhadram, V. S., Kim, D. Y. & Strobel, T. A. High-pressure synthesis and characterization of incompressible titanium pernitride. Chem. Mater. 28, 1616–1620 (2016).

Niwa, K. et al. High pressure synthesis of marcasite-type rhodium pernitride. Inorg. Chem. 53, 697–699 (2014).

Niwa, K. et al. Discovery of the last remaining binary platinum-group pernitride RuN2. Chem. A Eur. J. 20, 13885–13888 (2014).

Niwa, K. et al. Highly coordinated iron and cobalt nitrides synthesized at high pressures and high temperatures. Inorg. Chem. 56, 6410–6418 (2017).

Bykov, M. et al. Fe-N system at high pressure reveals a compound featuring polymeric nitrogen chains. Nat. Commun. 9, 2756 (2018).

Friedrich, A. et al. Novel rhenium nitrides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 085504 (2010).

Wang, Y., Yao, T., Yao, J.-L., Zhang, J. & Gou, H. Does the real ReN2 have the MoS2 structure? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 183–187 (2013).

Zhao, Z. et al. Nitrogen concentration driving the hardness of rhenium nitrides. Sci. Rep. 4, 4797 (2014).

Kawamura, F., Yusa, H. & Taniguchi, T. Synthesis of rhenium nitride crystals with MoS2 structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 251910 (2012).

Bykov, M. et al. High-pressure synthesis of a nitrogen-rich inclusion compound ReN8⋅xN2 with conjugated polymeric nitrogen chains. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 9048–9053 (2018).

Klotz, S., Chervin, J.-C., Munsch, P., Le Marchand, G. & Le Marchand, G. Hydrostatic limits of 11 pressure transmitting media. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 42, 075413 (2009).

Angel, R. J. Equations of state. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 41, 35–60 (2000).

Hazen, R. M. & Finger, L. W. Bulk modulus—volume relationship for cation-anion polyhedra. J. Geophys. Res. 84, 6723 (1979).

Chen, X.-J. et al. Hard superconducting nitrides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 102, 3198–3201 (2005).

Wu, Z. et al. Crystal structures and elastic properties of superhard IrN2 and IrN3. Phys. Rev. B 76, 054115 (2007).

Chen, Z. W. et al. Crystal structure and physical properties of OsN2 and PtN2 in the marcasite hase. Phys. Rev. B 75, 054103 (2007).

Nye, J. F. Physical Properties of Crystals. (Clarendon Press, Oxford, New York, 1985).

Wessel, M. & Dronskowski, R. Nature of N-N bonding within high-pressure noble-metal pernitrides and the prediction of lanthanum pernitride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 2421–2429 (2010).

Hill, R. The elastic behaviour of a crystalline aggregate. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. A 65, 349–354 (1952).

Yu, S., Zeng, Q., Oganov, A. R., Frapper, G. & Zhang, L. Phase stability, chemical bonding and mechanical properties of titanium nitrides: a first-principles study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 11763–11769 (2015).

Jhi, S., Ihm, J., Louie, S. G. & Cohen, M. L. Electronic mechanism of hardness enhancement in transition-metal carbonitrides. Nature 399, 132–134 (1999).

Dubrovinsky, L., Dubrovinskaia, N., Prakapenka, V. B. & Abakumov, A. M. Implementation of micro-ball nanodiamond anvils for high-pressure studies above 6 Mbar. Nat. Commun. 3, 1163 (2012).

Zha, C.-S., Bassett, W. A. & Shim, S.-H. Rhenium, an in situ pressure calibrant for internally heated diamond anvil cells. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75, 2409–2418 (2004).

Anzellini, S., Dewaele, A., Occelli, F., Loubeyre, P. & Mezouar, M. Equation of state of rhenium and application for ultra high pressure calibration. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 043511 (2014).

Ishii, T. et al. Generation of pressures over 40 GPa using Kawai-type multi-anvil press with tungsten carbide anvils. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 87, 024501 (2016).

Frierson, W. J. & Filbert, W. F. Ammonium azide. Inorg. Synth. 8, 136 (1946).

Fei, Y. et al. Toward an internally consistent pressure scale. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 104, 9182–9186 (2007).

Liermann, H.-P. et al. The extreme conditions beamline P02.2 and the extreme conditions science infrastructure at PETRA III. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 22, 908–924 (2015).

Prescher, C. & Prakapenka, V. B. DIOPTAS: a program for reduction of two-dimensional X-ray diffraction data and data exploration. High. Press. Res. 35, 223–230 (2015).

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Adv. 71, 3–8 (2015).

Petříček, V., Dušek, M. & Plášil, J. Crystallographic computing system Jana2006: solution and refinement of twinned structures. Z. Kristallogr. - Cryst. Mater. 231, 583–599 (2016).

Merle, B., Maier-Kiener, V. & Pharr, G. M. Influence of modulus-to-hardness ratio and harmonic parameters on continuous stiffness measurement during nanoindentation. Acta Mater. 134, 167–176 (2017).

Oliver, W. C. & Pharr, G. M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 7, 1564–1583 (1992).

Oliver, W. C. & Pharr, G. M. Measurement of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: Advances in understanding and refinements to methodology. J. Mater. Res. 19, 3–20 (2004).

Simmons, G. & Wang, H. Single Crystal Elastic Constants and Calculated Aggregate Properties. A Handbook. (The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1971).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Csonka, I. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Armiento, R. & Mattsson, A. E. Functional designed to include surface effects in self-consistent density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 72, 085108 (2005).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Acknowledgements

N.D. and L.D. thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG projects DU 954-11/1 and DU 393-10/1) and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany (BMBF, grant no. 5K16WC1) for financial support. S.V. and W.S. are grateful for a PhD fellowship granted by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (FCI), Germany. B.M. thanks the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG project ME 4368/7-1) for financial support. Parts of this research were carried out at the Extreme Conditions Beamline (P02.2) at DESY, a member of Helmholtz Association (HGF). Portions of this work was performed at GeoSoilEnviroCARS (The University of Chicago, Sector 13), Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by the National Science Foundation-Earth Sciences (EAR-1634415) and Department of Energy-GeoSciences (DE-FG02-94ER14466). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357, as well as resources from the Center for Nanoanalysis and Electron Microscopy (CENEM) at Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg. Several high-pressure diffraction experiments were performed on beamline ID15B at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), Grenoble, France. We thank Sven Linhardt, Gerald Bauer, Dorothea Wiesner, and Alexander Kurnosov for the help with electrical resistance measurements, SEM measurements and gas-loading. Theoretical analysis of chemical bonding was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 18-12-00492). Theoretical calculations of structural properties were supported by the Ministry of Science and High Education of the Russian Federation in the framework of Increase Competitiveness Program of NUST “MISIS” (No. K2-2019-001) implemented by a governmental decree dated 16 March 2013, No 211. Financial support from the Swedish Research Council (VR) through Grant No. 2015-04391, the Swedish Government Strategic Research Area in Materials Science on Functional Materials at Linkçping University (Faculty Grant SFO-Mat-LiU No. 2009-00971), and the VINN Excellence Center Functional Nanoscale Materials (FunMat-2) Grant 2016–05156 is gratefully acknowledged. This research is also supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No. 787527).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B., L.D., and N.D. designed the research, M.B., L.D., N.D., I.A.A. wrote the paper, M.B., L.D., S.C, T.F., G.A., V.B.P., E.G., M.H., and A.P. H.-P.L. performed X-ray diffraction experiments, M.B. analyzed the X-ray diffraction data, F.T, A.V.P., I.A. performed theoretical calculations, H.F., M.B., T.K., S.V., W.S. performed synthesis in the large volume press and the synthesis of precursors. B.M. and P.F. performed nanoindentation measurements. L.D. performed electrical resistance measurements. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bykov, M., Chariton, S., Fei, H. et al. High-pressure synthesis of ultraincompressible hard rhenium nitride pernitride Re2(N2)(N)2 stable at ambient conditions. Nat Commun 10, 2994 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10995-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10995-3

This article is cited by

-

Stabilization of N6 and N8 anionic units and 2D polynitrogen layers in high-pressure scandium polynitrides

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Materials synthesis at terapascal static pressures

Nature (2022)

-

Chemistry under high pressure

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.