Abstract

Spin–orbit torque (SOT), which is induced by an in-plane electric current via large spin-orbit coupling, enables an innovative method of manipulating the magnetization of ferromagnets by means of current injection. In conventional SOT bilayer systems, the magnetization switching efficiency strongly depends on the interface quality and the strength of the intrinsic spin Hall Effect. Here, we demonstrate highly efficient full SOT switching achieved by applying a current in a single layer of perpendicularly magnetized ferromagnetic semiconductor GaMnAs with an extremely small current density of ∼3.4 × 105 A cm−2, which is two orders of magnitude smaller than that needed in typical metal bilayer systems. This low required current density is attributed to the intrinsic bulk inversion asymmetry of GaMnAs as well as its high-quality single crystallinity and large spin polarization. Our findings will contribute to advancements in the electrical control of magnetism and its practical application in semiconductor devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spin–orbit torque (SOT) magnetization switching, which is induced by a spin current that is generated by a charge current, is a promising phenomenon that can be used to improve the performance of magnetoresistive random access memory devices. SOT switching allows the read and write paths to be separated and thus enables the independent co-optimization of readability, access latency and energy consumption, thereby decreasing the read error rate. At present, SOT switching has been achieved in metal systems1,2,3,4 and topological insulator systems5,6, which essentially require two functional layers, namely, one ferromagnetic layer and one paramagnetic layer to generate the spin current and inject it into the ferromagnetic layer. The spin current then exerts a torque on the magnetic moment to reverse it2,7,8,9. Hence, the switching efficiency strongly depends on the quality of the interface between the two layers. Furthermore, a large spin polarization in the nonmagnetic layer is necessary for efficient spin injection. Thus, heavy metals and topological insulators with large spin Hall angles, such as Pt, Ta, W, and BiSb10,11,12, are usually used for SOT switching. While topological insulators have been also proposed to achieve an efficient SOT switching using the surface state effect, the switching process is still improvable in terms of the switching hysteresis and its completeness13.

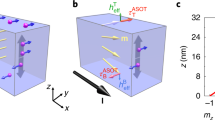

Here, we demonstrate highly efficient full SOT switching that is achieved by applying a current in a single layer of perpendicularly magnetized ferromagnetic semiconductor GaMnAs (Fig. 1a). In a GaMnAs thin film, due to the intrinsic bulk inversion asymmetry of its strained zinc-blende crystal structure and the structural inversion asymmetry induced by the heterostructure, intrinsic spin–orbit interactions couple the spin of a hole with its momentum and generate the effective magnetic field14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. The effective field is contributed by two parts (Fig. 1b), the Dresselhaus-like field (HD) and Rashba-like field (HR). Here, the sign and the magnitude of HD can be changed by the state of strain20. Chernyshov et al. showed partial in-plane magnetization rotation of 90° using the field-like torque in a GaMnAs thin film with in-plane four-fold magnetic anisotropy; however, the prolonged switching process and the efficiency still need to be improved for the realization of full magnetization switching17. In this work, we show that the effective fields due to the spin–orbit interactions can induce a spin component whose direction depends on the current orientation and that this spin component can exert a damping-like torque on the magnetic moment, thus enabling efficient 180° magnetization switching with an extremely low current density. In our high-quality single-crystalline GaMnAs thin film, we can expect a low spin-scattering rate, a large effective magnetic field due to the high momentum of the holes originating from impurity-band conduction22,23,24,25, and a high spin polarization26, leading to the successful realization of efficient full SOT switching.

Schematic illustrations of the device structure and the effective magnetic field. a Schematic of SOT switching and illustration of the cross-bar device structure of the Ga0.94Mn0.06As (7 nm)/In0.3Ga0.7As (500 nm)/GaAs (50 nm) thin film grown on a GaAs (001) substrate. The channel width of the cross-bar is 5 μm. The charge current is applied along the +y direction, and the spin component in the −x direction (\({\hat{\mathbf{\sigma}}}\)x) exerts a torque on the magnetic moment (\({\hat{\mathbf{m}}}\)) and reverses it. b Dresselhaus-like (red) and Rashba-like (blue) effective magnetic fields (HD and HR, respectively) for hole momenta along different crystallographic directions in the tensile Ga0.94Mn0.06As thin film. (kx, ky) is the wave vector of the holes. The dark colored arrows labeled HD and HR correspond to the effective magnetic fields when J > 0 in the y direction

Results

Magnetization reversal in the Ga0.94Mn0.06As single layer

The sample examined in this study is composed of Ga0.94Mn0.06As (7 nm)/In0.3Ga0.7As (500 nm)/GaAs (50 nm) grown on a GaAs (001) substrate via molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) (see Supplementary Note 1). The 500-nm In0.3Ga0.7As layer applies a tensile strain to the Ga0.94Mn0.06As thin film to induce perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (PMA). The film is patterned into a cross-bar device for transport measurements, as shown in Fig. 1a, with a channel width and length of 5 μm and 20 μm, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 2a, b, we can successfully achieve current-induced magnetization reversal in the proposed device. We note that the error bar of our experiments is smaller than the size of the data points. Before the transport measurement depicted in Fig. 2a, a large magnetic field of 10 kOe was applied along the –z direction to align the initial magnetization M0 in this direction (point a in Fig. 2a). After decreasing this magnetic field to zero, we applied an external magnetic field Hy along the \([\bar 1{\mathrm{10}}]\) direction (the current direction) to assist in SOT switching and to ensure deterministic magnetization reversal (see Fig. 1a). Then, we measured the Hall resistance (RH) by measuring the voltage between electrodes A and B shown in Fig. 1a, sweeping a direct current (with a density denoted by J) along the y direction in the order indicated by steps 1 to 5 on the black curve (Hy = +500 Oe) in Fig. 2a. With this variation of J, RH varies within approximately ±1.6 kΩ, which is consistent with the RH value of the anomalous Hall effect (see Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2a, i.e., ∼±1.7 kΩ), indicating that the magnetization is fully reversed between the +z and −z directions by the current. When the current is applied along the \([\bar 1{\mathrm{10}}]\) direction (the +y direction), both HD and HR are generated along the \([\bar 1\bar 10]\) (−x) direction (see the dark colored arrows in Fig. 1b). Thus, as shown in Fig. 2c, the hole spin has an x component σx in the minus direction due to these two effective magnetic fields. \({\hat{\mathbf{\sigma }}}_x\) induces a damping-like torque (DLT) \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ST}}}\) that is proportional to \({\hat{\mathbf{m}}} \times {\hat{\mathbf{\sigma }}}_x \times {\hat{\mathbf{m}}}\) and whose direction is the same as that of \({\hat{\mathbf{\sigma }}}_x\)2,27. Here, \({\hat{\mathbf{m}}}\) represents the unit magnetization vector, and \({\hat{\mathbf{\sigma }}}_x\) is the x component of the spin polarization vector. In addition to the DLT, there is a torque \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{an}}}\) that is induced by the perpendicular anisotropy field Han, i.e., \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{an}}} = - {\hat{\mathbf{m}}} \times {\hat{\mathbf{H}}}_{{\mathrm{an}}}\), and a torque \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ext}}}\) that is induced by Hy, i.e., \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ext}}} = - {\hat{\mathbf{m}}} \times {\hat{\mathbf{H}}}_y\). When Hy = +500 Oe, in the initial magnetization state M0 along the −z direction, the magnetization is slightly tilted towards the +y direction. In this case, when J > 0, \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ST}}}\) points in the same direction as \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ext}}}\), which is opposite to the direction of \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{an}}}\) (Fig. 2c). With increasing J, \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ST}}}\) is enhanced and reverses the magnetic moment with the assistance of \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ext}}}\) (step 1 on the black curve in Fig. 2a). Subsequently, as J decreases to 0, \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ST}}}\) becomes 0, and the magnetic moment then points in the +z direction (step 2 on the black curve). Similarly, when J < 0, the magnetic moment is pulled back to the −z direction via the y > 0 side (steps 3 and 4 on the black curve), where the directions of \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ST}}}\), \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{an}}}\) and \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ext}}}\) are the opposite of what they are in the abovementioned case of J > 0. Finally, as J again increases in the positive direction (step 5 on the black curve), the switching process occurs in the same way as in step 1 on the black curve, which indicates that the current-induced switching process is repeatable. By contrast, when Hy = −500 Oe (see the illustrations of the torques in Fig. 2d), the switching polarity can be symmetrically changed with the reversal of the sign of Hy (see the black and red curves in Fig. 2a), which is a typical characteristic of SOT switching in PMA thin films7. Here, the critical switching current density Jc is 3.43 × 105 A cm−2 with Hy = 500 Oe at 40 K. This value of Jc is two orders of magnitude less than that in metal systems, which is usually on the order of 107 A cm–2 1,7,28.

SOT switching (40 K) and the relevant switching mechanism. a, b Field-assisted SOT switching with J // \(\left[ {\bar 1{\mathrm{10}}} \right]\) and Hy = ± 500 Oe (a) and with J // [110] and Hx = ± 500 Oe (b). c, d Illustrations of the torques exerted by the external field (\({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ext}}}\)), the anisotropy field (\({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{an}}}\)) and the spin component along the –x direction \(({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ST}}})\) with J > 0 when Hy > 0 (c) and Hy < 0 (d). \({\hat{\mathbf{m}}}\) is in the y-z plane. (Source data are provided as a Source Data file)

We can see that by changing the directions of J and the external magnetic field from \([\bar 110]\) to [110] (i.e., Hx), the HD is dominant whereas the HR is negligibly small in our GaMnAs film, as shown below. In this case, when J > 0 (in the +x direction), HD is generated along \([1\bar 10]\), but HR is along \([\bar 110]\), as shown in Fig. 1b. As shown in Fig. 2b, the current-induced SOT switching curves with an Hx of ±500 Oe, which start with the initial magnetization state in the −z direction (point a), present the opposite polarities relative to the results in Fig. 2a. This finding indicates that the direction of the total effective magnetic field relative to the current direction in Fig. 2b is different from that in Fig. 2a. As shown in Fig. 1b, while the direction of HR relative to J [//(+x)] is the same as that when J // (+y), the relative direction of HD is the opposite. Thus, HD is dominant in our system. Furthermore, based on the nearly identical values of Jc between Fig. 2a, b, we can conclude that HR is negligibly small. Because the Rashba effect is relevant only near the interfaces, whereas the current flows mainly in the bulk of the GaMnAs layer in our study, this conclusion is reasonable.

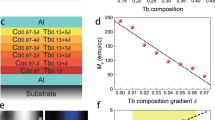

Estimation of the heating effect and switching phase diagram

As shown in Fig. 3a, to estimate the heating effect during the measurement shown in Fig. 2a, b, we made another cross-bar device with electrodes covered with Au (100 nm)/Cr (5 nm) as heat sinks (see the yellow parts in Fig. 3a), using the same MBE-grown wafer. The temperature (T) dependence of the SOT switching in this device is shown in Fig. 3b, indicating that the magnetization switching process is basically stable at T up to 60 K. As shown in Fig. 3c, both Jc and the remanent magnetization (MR) nearly disappear at T = 70 K. Hence, we conclude that the heating effect is negligibly small in this device with metal electrodes.

Estimation of the heating effect and switching phase diagrams. a Schematic illustration of the device with Au (100 nm)/Cr (5 nm) electrodes as heat sinks. b SOT switching at various temperatures. c Temperature dependences of Jc with an external magnetic field (Hy) of 500 Oe applied along the \([\bar 1{\mathrm{10}}]\) axis and remanent magnetization MR. d, e Switching phase diagram of the Ga0.94Mn0.06As thin film about temperature (T) (d) and applied external magnetic field (Hy) along the \([\bar 1{\mathrm{10}}]\) axis (e). (Source data are provided as a Source Data file)

We summarize the switching behavior shown in Fig. 3b as a phase diagram in Fig. 3d, which indicates that Jc decreases with the increase of T. Combining these results with the magnetization hysteresis curves of the Ga0.94Mn0.06As thin film measured with various magnetic field orientations (see Supplementary Fig. 3), the decrease of Jc can be attributed to the decrease in the anisotropy field. The actual temperature during the measurement shown in Fig. 2a, b might be around 10 K higher than the set value (Tset = 40 K) because the critical switching current density of 3.4 × 105 A cm−2 is closed to the value of 4.2 × 105 A cm−2 obtained at T = 50 K in the device with the Au/Cr capping layer. This estimation is also consistent with the fact that the shape of the switching curve is firmly square-like in Fig. 2a, b at Tset = 40 K like the ones obtained at T below 50 K in the device with the Au/Cr capping layer (Fig. 3b). In addition, we carried out measurements of SOT switching with various external magnetic fields Hy applied along the y direction and summarized them as a switching phase diagram as shown in Fig. 3e, indicating that Jc decreases with the increase of Hy when Hy is lower than 500 Oe but increases with the increase in Hy when Hy is larger than 500 Oe. When Hy is lower than 500 Oe, Hy assists the SOT switching and decreases the switching current density, which is consistent with the typical SOT switching. However, the origin of the behavior when Hy is larger than 500 Oe is unclear at present and needs further studies. Hy may tilt part of the magnetization along this magnetic-field direction, and the magnetization switching may also occur near the film plane17. In this case, large Hy does not aid the switching process but hinders it, resulting in the increase of the switching current density.

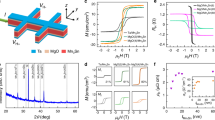

Spin–orbit torque strength in the Ga0.94Mn0.06As thin film

The SOT strength can be quantitatively characterized by the equivalent magnetic field (Hequi)29. We measured RH at 40 K with a current of ±0.3 mA applied along the \([\bar 1{\mathrm{10}}]\) direction and a fixed external magnetic field of 500 Oe applied at an angle β from the \([\bar 1{\mathrm{10}}]\) direction in the y-z plane as shown in Fig. 4a, b. When the current is positive (see the blue lines in Fig. 4a), \({\hat{\mathbf{\tau }}}_{{\mathrm{ST}}}\) is along the –x direction, which gives a force to the magnetization in the counterclockwise direction when we see it from the +x direction (see Fig. 2c). At point A in Fig. 4a with the magnetization in the –z direction, the increase in β helps the magnetization rotate in this counterclockwise direction, and thus the magnetization can easily rotate. However, at point B in Fig. 4a with the magnetization in the +z direction, because the magnetic field direction is the opposite to the rotation direction of the magnetization, it does not rotate until the –z component of the magnetic field becomes large when β is increased in the negative direction. Therefore, one can see that the asymmetry of the data around β = 0 between the different sweep directions of β in Fig. 4 is related to the SOT. When the angle β is small, the effective magnetic field Hequi that is equivalent to the SOT strength is given by Hext·βav29. Here, βav is the average of the β values at the magnetization switching with the different sweep directions of β for positive and negative current directions: βav = (|β(+, →) + β(+, ←)| + |β(−, →) + β(−, ←)|)/4, where the subscript arrow represents the sweeping direction of β, and ± represent the current direction. Here, βav is estimated to be (7.91° + 11.49°)/2 = 9.7°. Thus, Hequi is estimated to be 500 × 9.7 × π/180 = 84.6 Oe and the efficiency of the equivalent field, χ = Hequi/Jc, where Jc is 8.5 × 105 A cm−2 at 40 K in Fig. 3b, is estimated to be 99 Oe/(106 A cm−2), which is almost two orders of magnitude lager than that [1.7 Oe/(106 A cm−2)] in the Pt/Co bilayer system, indicating that very efficient magnetization switching is realized in GaMnAs. Figure 4c, d shows the SOT strength measured at T = 50 K and T = 60 K with a current of I = ±0.1 mA (less than the switching current), from which Hequi is estimated to be 31 Oe at T = 50 K and 17 Oe at T = 60 K. Hence, we can conclude that the SOT strength decreases with the increase of temperature because the effective field becomes weak.

Spin–orbit torque strength in the Ga0.94Mn0.06As thin film. a RH measured with a current of ±0.3 mA and an external field of 500 Oe applied at an angle β from the \(\left[ {\bar 1{\mathrm{10}}} \right]\) direction in the y-z plane. The arrows in the graph represent the sweeping directions of β. b Illustrations of the current (J), the external magnetic field (Hext) and β. c, d RH measured with the current of ±0.1 mA and an external field of 500 Oe applied at an angle β from the \(\left[ {\bar 1{\mathrm{10}}} \right]\) direction in the y-z plane at T = 50 K (c) and T = 60 K (d). (Source data are provided as a Source Data file)

Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert (LLG) simulation

The obtained RH − J curves are well reproduced by the LLG equation, which confirms the scenario described above. Here, we consider the SOT switching result obtained at 40 K for the device with metal electrodes as heat sinks (see Fig. 3b) (i.e., J // y with Hy). The LLG equation is expressed as

where \(\dot{{\widehat{\bf{m}}}}\) is the derivative of \({\hat{\bf{m}}}\) with respect to time; \({\hat{\mathbf{H}}}\) is the effective field consisting of the external field, the anisotropy field, HD and HR; γ is the gyromagnetic ratio; α is the damping constant; \(\zeta _{{\mathrm{DLT}}}\) is the DLT coefficient; and \(\zeta _{{\mathrm{FLT}}}\) is the field-like torque (FLT) coefficient. Here, we replace \(\zeta _{{\mathrm{DLT}}}{\hat{\mathbf{\sigma }}}_x\) with \({\it{r\gamma }}{\hat{\mathbf{S}}}_x\) and \(\zeta _{{\mathrm{FLT}}}{\hat{\bf{\sigma }}}_x\) with \(\frac{{\gamma (1 - r)}}{\alpha }{\hat{\bf{S}}}_x\), where \({\hat{\bf{S}}}_x\) is the effective magnetic field in the x direction and r expresses the strength of the DLT relative to the total SOT: when r is 0, only the FLT is present, and when r is 1, only the DLT is present. As shown in Supplementary Note 4, the LLG equation can be transformed into

where

When Hy = 500 Oe, Han = 2.13 kOe (for the estimation of Han, see Supplementary Note 2), and α = 0.0530, by solving the LLG equation for various r values, we obtained the quasi-static magnetization state in which \({\dot{\hat{\bf{m}}}}\) becomes zero for various Sx as shown in Fig. 5a. When r is 0, only the FLT is present, and no switching occurs. With increasing r, the switching curve shows characteristics much more similar to those of the experimental results, especially when r is 0.95, as shown in Fig. 5b, indicating that both the DLT and FLT act on SOT switching but that the DLT is dominant. Note that the direction of the J axis in Fig. 5b is reversed because the signs of J and Sx are opposite [e.g., when J > 0, Sx (or σx) < 0, as shown in Fig. 2c]. Figure 5c shows the calculated values of mx, my and mz, which are the x, y and z components of \({\hat{\mathbf{m}}}\), respectively, as functions of Sx. After the magnetic moment rotates to the opposite direction at Sx = −0.8 kOe, my and mz become close to 0 and mx becomes close to –1 as Sx increases to −2.4 kOe, indicating that the magnetic moment ultimately points along the −x axis (in the same direction as the DLT).

LLG simulation results and comparison with experimental results. a Simulated SOT switching with different r values of 0, 0.5, 0.9, 0.95 and 1. The parameters used here are Hy = 500 Oe, Han = 2.13 kOe and α = 0.05. b Simulated SOT switching at r = 0.95 and experimental results with Hy = 500 Oe. Note that the direction of the J axis is reversed because the signs of J and Sx are opposite [e.g., when J > 0, Sx (or σx) < 0, as shown in Fig. 2c]. c Calculated values of mx, my and mz as functions of Sx. (Source data are provided as a Source Data file)

Discussion

In this work, we have found that SOT switching can be achieved in a single-crystalline ferromagnet with intrinsic bulk inversion asymmetry, strong spin–orbit interactions and a large spin polarization. Furthermore, the switching current density Jc is very low (3.43 × 105 A cm−2) because of the large effective magnetic field, which is expected due to the large momentum of the holes originating from impurity-band conduction22,23,24,25. Our results provide us with guidance in selecting appropriate materials and offer a new possibility for achieving more efficient electrical control of magnetism, which will facilitate the development of SOT switching devices for practical applications.

Methods

Sample preparation

The Ga0.94Mn0.06As thin film was grown on a semi-insulating GaAs (001) substrate in an ultrahigh-vacuum MBE system. After the removal of the surface oxide layer of the GaAs substrate at 580 °C, a 50-nm-thick GaAs buffer layer was grown to obtain an atomically smooth surface. After that, the substrate was cooled down to 450 °C for the growth of In0.3Ga0.7As with a thickness of 500 nm to induce a tensile strain on the Ga0.94Mn0.06As layer, giving rise to PMA. Then, the sample was cooled down to 243 °C for the growth of the 7-nm Ga0.94Mn0.06As layer. The growth process was monitored in situ by means of reflection high-energy electron diffraction. The Curie temperature of the Ga0.94Mn0.06As layer was estimated to be 88 K (see Supplementary Note 1).

Device preparation and electrical measurements

The sample was patterned into a cross-bar device with a width of 5 μm using photolithography and argon ion milling. For the SOT measurements, a Keithley 2636 A instrument was used as the current source for applying the direct current. The Hall voltage was measured with a Keithley 2400 apparatus. The measurements were carried out at 40 K.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during this study are available at the 4TU. ResearchData repository, https://doi.org/10.4121/uuid:ede92a7d-6b44-4dcd-b555-7d9f76993dcc (ref. 31).

References

Miron, I. M. et al. Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection. Nature 476, 189–193 (2011).

Liu, L. et al. Current-induced switching of perpendicularly magnetized magnetic layers using spin torque from the spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 096602 (2012).

Emori, S. et al. Current-driven dynamics of chiral ferromagnetic domain walls. Nat. Mater. 12, 611–616 (2013).

Myers, E. B. et al. Current-induced switching of domains in magnetic multilayer devices. Science 285, 867–870 (1999).

Han, J. et al. Room-temperature spin-orbit torque switching induced by a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 077702 (2017).

Fan, Y. et al. Magnetization switching through giant spin-orbit torque in a magnetically doped topological insulator heterostructure. Nat. Mater. 13, 699–704 (2014).

Liu, L. et al. Spin-torque switching with the giant spin Hall effect of tantalum. Science 336, 555–558 (2012).

Qiu, X. et al. Characterization and manipulation of spin orbit torque in magnetic heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705699 (2018).

Song, C. et al. Recent progress in voltage control of magnetism: materials, mechanisms, and performance. Prog. Mater. Sci. 87, 33–82 (2017).

Wang, H. L. et al. Scaling of spin Hall angle in 3d, 4d, and 5d metals from Y3Fe5O12/metal spin pumping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 197201 (2014).

Hao, Q. & Xiao, G. Giant spin Hall effect and switching induced by spin-transfer torque in a W/Co40Fe40B20/MgO structure with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Appl. 3, 034009 (2015).

Melnik, A. R. et al. Spin-transfer torque generated by a topological insulator. Nature 511, 449–451 (2014).

Fan, Y. et al. Electric-field control of spin–orbit torque in a magnetically doped topological insulator. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 352 (2016).

Dresselhaus, G. Spin-orbit coupling effects in zinc blende structures. Phys. Rev. 100, 580 (1955).

Winkler, R. Spin-orbit coupling effects in two-dimensional electron and hole systems. Springer Tr. Mod. Phys. 191, 153–156 (2006).

Manchon, A. et al. New perspectives for Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Nat. Mater. 14, 871–882 (2015).

Chernyshov, A. et al. Evidence for reversible control of magnetization in a ferromagnetic material by means of spin-orbit magnetic field. Nat. Phys. 5, 656–659 (2009).

Endo, M., Matsukura, F. & Ohno, H. Current induced effective magnetic field and magnetization reversal in uniaxial anisotropy (Ga,Mn)As. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 222501 (2010).

Lee, S. et al. Field-free manipulation of magnetization alignments in a Fe/GaAs/GaMnAs multilayer by spin-orbit-induced magnetic fields. Sci. Rep. 7, 10162 (2017).

Fang, D. et al. Spin-orbit-driven ferromagnetic resonance. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 413 (2011).

Kurebayashi, H. et al. An antidamping spin–orbit torque originating from the Berry curvature. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 211 (2014).

Ohya, S., Takata, K. & Tanaka, M. Nearly non-magnetic valence band of the ferromagnetic semiconductor GaMnAs. Nat. Phys. 7, 342 (2011).

Kobayashi, M. et al. Unveiling the impurity band induced ferromagnetism in the magnetic semiconductor (Ga,Mn) As. Phys. Rev. B 89, 205204 (2014).

Muneta, I. et al. Sudden restoration of the band ordering associated with the ferromagnetic phase transition in a semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 7, 12013 (2016).

Muneta, I. et al. Artificial control of the bias-voltage dependence of tunnelling-anisotropic magnetoresistance using quantization in a single-crystal ferromagnet. Nat. Commun. 8, 15387 (2017).

Braden, J. G. et al. Direct measurement of the spin polarization of the magnetic semiconductor (Ga,Mn)As. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 056602 (2003).

Shi, G. Y. et al. Spin-orbit torque in MgO/CoFeB/Ta/CoFeB/MgO symmetric structure with interlayer antiferromagnetic coupling. Phys. Rev. B 95, 104435 (2017).

Fukami, S., Anekawa, T., Zhang, C. & Ohno, H. A spin-orbit torque switching scheme with collinear magnetic easy axis and current configuration. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 621–625 (2016).

Zhang, P. X. et al. Spin-orbit torque in a completely compensated synthetic antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 97, 214403 (2018).

Khazen, K. et al. Anisotropic magnetization relaxation in ferromagnetic Ga1−xMnxAs thin films. Phys. Rev. B 78, 195210 (2008).

Jiang, M. et al. Data underlying the research on Efficient full spin-orbit torque switching in a single layer of a perpendicularly magnetized single-crystalline ferromagnet. 4TU.Centre for Research Data. Dataset https://doi.org/10.4121/uuid:ede92a7d-6b44-4dcd-b555-7d9f76993dcc (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 16H02095, No. 18H03860), the CREST program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JPMJCR1777), and the Spintronics Research Network of Japan (Spin-RNJ). M.J. acknowledges the support of China Scholarship Council (No. 201706210086).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sample preparation: M.J. and H.A.; measurements: M.J., T.K. and H.Y.; data analysis: M.J. and S.S.; writing and project planning: M.J., S.O. and M.T.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks Xinyu Liu and other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, M., Asahara, H., Sato, S. et al. Efficient full spin–orbit torque switching in a single layer of a perpendicularly magnetized single-crystalline ferromagnet. Nat Commun 10, 2590 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10553-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10553-x

This article is cited by

-

Asymmetric magnetization switching and programmable complete Boolean logic enabled by long-range intralayer Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Intrinsic spin Hall torque in a moiré Chern magnet

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Perpendicular full switching of chiral antiferromagnetic order by current

Nature (2022)

-

Ferromagnetism modulation by ultralow current in a two-dimensional polycrystalline molybdenum disulphide atomic layered structure

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Fabrication and characterization of epitaxial ferrimagnetic Mn3Ga thin films with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy

Emergent Materials (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.