Abstract

There is a large body of evidence that atomic nuclei can undergo octupole distortion and assume the shape of a pear. This phenomenon is important for measurements of electric-dipole moments of atoms, which would indicate CP violation and hence probe physics beyond the Standard Model of particle physics. Isotopes of both radon and radium have been identified as candidates for such measurements. Here, we observed the low-lying quantum states in 224Rn and 226Rn by accelerating beams of these radioactive nuclei. We show that radon isotopes undergo octupole vibrations but do not possess static pear-shapes in their ground states. We conclude that radon atoms provide less favourable conditions for the enhancement of a measurable atomic electric-dipole moment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well established by the observation of rotational bands that atomic nuclei can assume quadrupole deformation with axial and reflection symmetry, usually with the shape of a rugby ball. The distortion arises from long-range correlations between valence nucleons, which becomes favourable when the proton and/or neutron shells are partially filled. For certain values of proton and neutron number it is expected that additional correlations will cause the nucleus to also assume an octupole shape (‘pear-shape’) where it loses reflection symmetry in the intrinsic frame1. The fact that some nuclei can have pear-shapes has influenced the choice of atoms having nuclei with odd nucleon number A (=Z + N) employed to search for permanent electric-dipole moments (EDMs). Any measurable moment will be amplified if the nucleus has octupole collectivity and further enhanced by static-octupole deformation. At present, experimental limits on EDMs, that would indicate charge-parity (CP) violation in fundamental processes where flavour is unchanged, have placed severe constraints on many extensions of the Standard Model. Recently, new candidate atomic species, such as radon and radium, have been proposed for EDM searches. For certain isotopes octupole effects are expected to enhance, by a factor 100–1000, the nuclear Schiff moment (the electric-dipole distribution weighted by radius squared) that induces the atomic EDM2,3,4, thus improving the sensitivity of the measurement. There are two factors that contribute to the greater electrical polarizability that causes the enhancement: (i) the odd-A nucleus assumes an octupole shape; (ii) an excited state lies close in energy to the ground state with the same angular momentum and intrinsic structure but opposite parity. Such parity doublets arise naturally if the deformation is static (permanent octupole deformation).

The observation of low-lying quantum states in many nuclei with even Z, N having total angular momentum (‘spin’) and parity of \(I^\pi = 3^ -\) is indicative of their undergoing octupole vibrations about a reflection-symmetric shape. Further evidence is provided by the sizeable value of the electric octupole (E3) moment for the transition to the ground state, indicating collective behaviour of the nucleons. However, the number of observed cases where the correlations are strong enough to induce a static pear-shape is much smaller. Strong evidence for this type of deformation comes from the observation of a particular behaviour of the energy levels for the rotating quantum system and from an enhancement in the E3 moment5. So far there are only two cases, 224Ra6 and 226Ra7 for which both experimental signatures have been observed. The presence of a parity doublet of 55 keV at the ground state of 225Ra makes this nucleus therefore a good choice for EDM searches8. In contrast to the radium isotopes, much less is known about the behaviour of radon (Rn) nuclei proposed as candidates for atomic EDM searches on account of possible enhancement of their Schiff moments9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. For this reason, different isotopes of radon have been listed in the literature, for example 221,223,225Rn14, each having comparable half-lives and ground state properties. The most commonly chosen isotope for theoretical calculations9,10 and the planning of experiments11,12,13 is 223Rn.

In this work, we present data on the energy levels of heavy even-even Rn isotopes to determine whether parity doublets are likely to exist near the ground state of neighbouring odd-mass Rn nuclei. Direct observation of low-lying states in odd-A Rn nuclei (for example following Coulomb excitation or β-decay from the astatine parent) is presently not possible, as it will require significant advances in the technology used to produce radioactive ions. We observe that 224,226Rn behave as octupole vibrators in which the octupole phonon is aligned to the rotational axis. We conclude that there are no isotopes of radon that have static-octupole deformation, so that any parity doublets in the odd-mass neighbours will not be closely spaced in energy. This means that radon atoms will provide less favourable conditions for the enhancement of a measurable atomic electric-dipole moment.

Results

Measurement of the quantum structure of heavy radon isotopes

In the experiments described here, 224Rn (Z = 86, N = 138) and 226Rn (Z = 86, N = 140) ions were produced by spallation in a thick thorium carbide target bombarded by ~1013 protons s−1 at 1.4 GeV from the CERN PS Booster. The ions were accelerated in HIE-ISOLDE to an energy of 5.08 MeV per nucleon and bombarded secondary targets of 120Sn. In order to verify the identification technique, another isotope of radon, 222Rn, was accelerated to 4.23 MeV/u. The γ-rays emitted following the excitation of the target and projectile nuclei were detected in Miniball18, an array of 24 high-purity germanium detectors, each with six-fold segmentation and arranged in eight triple-clusters. The scattered projectiles and target recoils were detected in a highly segmented silicon detector19. See Methods.

Prior to the present work, nothing was known about the energies and spins of excited states in 224,226Rn, while de-exciting γ-rays from states in 222Rn had been observed20 with certainty up to \(I^\pi = 13^ -\). The chosen bombarding energies for 224,226Rn were about 3% below the nominal Coulomb barrier energy at which the beam and target nuclei come close enough in head-on collisions for nuclear forces to significantly influence the reaction mechanism. For such close collisions the population of high-spin states will be enhanced, allowing the rotational behaviour of the nucleus to be elucidated. This is the method described by Ward et al.21 and has subsequently been coined unsafe Coulomb excitation22 as the interactions between the high-Z reaction partners is predominantly electromagnetic. It is not possible to precisely determine electromagnetic matrix elements because of the small nuclear contribution. The most intense excited states expected to be observed belong to the positive-parity rotational band, built upon the ground state. These states are connected by fast electric quadrupole (E2) transitions. In nuclei that are unstable to pear-shaped distortion, the other favoured excitation paths are to members of the octupole band, negative-parity states connected to the ground-state band by strong E3 transitions.

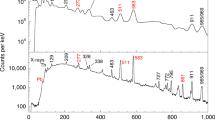

The spectra of γ-rays time-correlated with scattered beam and target recoils are shown in Fig. 1. The E2 γ-ray transitions within the ground-state positive-parity band can be clearly identified, as these de-excite via a regular sequence of strongly-excited states having spin and parity \(0^ + ,2^ + ,4^ + , \ldots\) with energies \(\frac{{\hbar ^2}}{{2\Im }}I\left( {I + 1} \right)\). In this expression the moment-of-inertia \(\Im\) systematically increases with increasing \(I\) (reducing pairing) and with number of valence nucleons (increasing quadrupole deformation). As expected from multi-step Coulomb excitation the intensities of the transitions systematically decrease with increasing \(I\), after correcting for internal conversion and the γ-ray detection efficiency of the Miniball array.

Spectra of γ-rays. The γ-rays were emitted following the bombardment of 120Sn targets by 222Rn (black), 224Rn (blue) and 226Rn (red). The γ-rays were corrected for Doppler shift assuming that they are emitted from the scattered projectile. Random coincidences between Miniball and CD detectors have been subtracted. The transitions which give rise to the observed full-energy peaks are labelled by the spin and parity of the initial and final quantum states. The assignments of the transitions from the negative-parity states in 224,226Rn are tentative (see text)

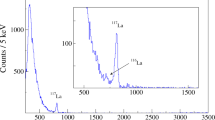

The other relatively intense γ-rays observed in these spectra with energies <600 keV are assumed to have electric-dipole (E1) multipolarity, and to depopulate the odd-spin negative-parity members of the octupole band. In order to determine which states are connected by these transitions, pairs of time-correlated (‘coincident’) γ-rays were examined. In this analysis, the energy spectrum of γ-rays coincident with one particular transition is generated by requiring that the energy of this ‘gating’ transition lies in a specific range. Typical spectra obtained this way are shown in Fig. 2. Each spectrum corresponds to a particular gating transition, background subtracted, so that the peaks observed in the spectrum arise from γ-ray transitions in coincidence with that transition.

Coincidence γ-ray spectra. The representative background-subtracted γ-ray spectra are in time-coincidence with different gating transitions. Here the observed peaks are labelled by the energy (in keV) of the transition. The gating transition is additionally labelled by the proposed spin and parity of the initial and final states

The level schemes for 224,226Rn constructed from the coincidence spectra, together with the known20 scheme for 222Rn, are shown in Fig. 3. For 226Rn the energy of the strongly-converted \(2^ + \to 0^ +\) transition overlaps with those of the Kβ X-rays, but its value can be determined assuming that the relative intensity of Kβ, Kα X-rays is the same as for 222,224Rn. The E2 transitions connecting the states in the octupole band are not observed because they cannot compete with faster, higher-energy E1 decays. The only other plausible description for this band is that it has \(K^\pi = 0^ +\) or 2+, implying that the \(K^\pi = 0^ -\) octupole band is not observed. (Here K is the projection of I on the body-fixed symmetry axis.) This is unlikely as the bandhead would have to lie significantly lower in energy than has been observed in 222,224,226Ra, and inter-band transitions from states with I’ > 4 to states with I and I-2 in the ground-state band and in-band transitions to I’-2 would all be visible in the spectra. The spin and parity assignments for the positive-parity band that is strongly populated by Coulomb excitation can be regarded as firm, whereas the negative-parity state assignments are made in accord with the systematic behaviour of nuclei in this mass region.

Level schemes. These partial level schemes for 222,224,226Rn show the excited states of interest. Arrows indicate γ-ray transitions. All energies are in keV. Firm placements of transitions in the scheme are from previous work20 or have been made using γ- γ-coincidence relations; otherwise in brackets

Characterisation of octupole instability

From the level schemes and from the systematics for all the radon isotopes (Fig. 4) it is clear that the bandhead of the octupole band reaches a minimum around N = 136. The character of the octupole bands can be explored23 by examining the difference in aligned angular momentum, \({\mathrm{\Delta }}i_x = i_x^ - - i_x^ +\), at the same rotational frequency ω, as a function of ω. Here \(i_x\) is approximately I for K=0 bands and \(\hbar \omega\) is approximately \((E_I - E_{I - 2})/2.\) For nuclei with permanent octupole deformation \({\mathrm{\Delta }}i_x\) is expected to approach zero, as observed for several isotopes of Ra, Th, and U5. For octupole-vibrational nuclei in which the negative-parity states arise from coupling an octupole phonon to the positive-parity states, it is expected that \(\Delta i_x\sim 3\hbar\) as the phonon prefers to align with the rotational axis. This is the case for the isotopes 218,220,222,224Rn at values of \(\hbar \omega\) (<0.2 MeV) where particle-hole excitations do not play a role, see Fig. 4. Thus we have clearly delineated the lower boundary at Z > 86 as to where permanent octupole deformation occurs in nature.

Systematic behaviour of radon isotopes. a Systematics of the energies for different spins of low-lying positive-parity (black) and negative-parity states (red) in radon isotopes; b cartoon illustrating how the octupole phonon vector aligns with the rotation (R) vector (which is orthogonal to the rotating body’s symmetry axis) so that I = R + 3\(\hbar\) and \({\mathrm{\Delta }}i_x = 3\hbar\); c difference in aligned spin for negative- and positive-parity states in 218-224Rn (re-analysed for 218-222Rn that have been presented earlier23). The dashed line at \({\mathrm{\Delta }}i_x = 0\) is the expected value for static-octupole deformation

Discussion

The observation of octupole-vibrational bands in the even-even radon isotopes is consistent with several theoretical calculations24,25,26, which predict that only nuclei with Z > 86 have stable octupole deformation. Other calculations suggest that radon isotopes with A~222 will have non-zero values of the octupole deformation parameter β327,28. For such nuclei, which have a minimum in the nuclear potential energy at non-zero values of β3, the positive- and negative-parity states are projected from intrinsic configurations having \(K^\pi = 0^ + ,0^ -\), which are degenerate in energy. In the odd-A neighbours parity doublets arise by coupling the odd particle to these configurations. This is not the case for reflection-symmetric nuclei that undergo octupole vibrations around \(\beta _3 = 0.\) Bands of opposite parity with differing single-particle configurations can lie close to each other fortuitously29,30 but in general those arising from coupling the odd nucleon to the ground state and octupole phonon will be well separated. The separation will be determined by the spacing of the bands in the even-even core, ~500 keV in the case of 222-226Rn (see Fig. 4), and will be in general much larger than that the value (~50 keV) observed for parity doublets in radium isotopes1. Quantitative estimates of Schiff moments for octupole-vibrational systems have yet to be made31. Nevertheless, it can be concluded that, if measurable CP-violating effects occur in nuclei, the enhancement of nuclear Schiff moments arising from octupole effects in odd-A radon nuclei is likely to be much smaller than for heavier octupole-deformed systems.

Methods

Production of radioactive radon beams

In our experiments, 222,224,226Rn were produced by spallation in the primary target, diffused to the surface and then singly ionized (q = 1+) in an enhanced plasma ion-source32 with a cooled transfer line. The ions were then accelerated to 30 keV, separated according to A/q, and delivered to a Penning trap, REXTRAP33, at a rate of around 8 × 106 ions s−1 for 222Rn, 2 × 106 ions s−1 for 224Rn and 105 ions s−1 for 226Rn at the entrance. Inside the trap, the singly-charged ions were accumulated and cooled before being allowed to escape in bunches at 500 ms intervals into an electron-beam ion source, REXEBIS33. Here, the ions were confined for 500–700 ms in a high-density electron beam that stripped more electrons to produce a charge state of 51+ (222Rn) or 52+ (224,226Rn) extracted as 1 ms pulses before being mass-selected again according to A/q, and injected at 2 Hz into the HIE-ISOLDE linear post-accelerator. The Rn beams then bombarded a 120Sn target of thickness ~2 mg cm−2 with an intensity of about 6 × 105 ions s−1, 1.1 × 105 ions s−1 and 2 × 103 ions s−1 for 222Rn, 224Rn and 226Rn, respectively. The total beam-times were respectively 8, 16 and 24 h. The level of Fr impurity in the Rn beams could be estimated for A = 222 as below 1% by observing radioactive decays at the end of the beam line.

Data selection and Doppler correction

Events corresponding to the simultaneous detection of γ-rays and heavy ions in Miniball and the silicon detector array respectively were selected if the measured energy and angle of either projectile or target satisfied the expected kinematic relationship for inelastic scattering reactions. This procedure eliminated any background from stable noble-gas contaminant beams produced in REX-TRAP having the same A/q as the radon beams. In the present setup the average angle of each of the 16 strips of one side of the silicon detector array ranged between 19.6° and 54.9° to the beam direction, corresponding to a scattering angular range of 140.9°–70.2° in the centre-of-mass. In order to reduce background from Compton scattering, events were rejected if any two germanium crystals in each triple-cluster registered simultaneous γ-ray hits, in contrast to the normal adding procedure which would substantially increase the probability of summing two γ-rays emitted in the same decay sequence (‘true pile-up’). Miniball was calibrated using 133Ba and 152Eu radioactive sources that emitted γ-rays of known energy and relative intensity. The relativistic Doppler correction was performed by determining the momentum vector of the projectile, using the energy and position information in the pixelated silicon detector, and the emission polar and azimuthal angle of the detected gamma-ray in the segment of Miniball where most energy was deposited. In the case of the latter the relative orientation of each segment to each other and to the beam axis was determined by employing d(22Ne,pγ) and d(22Ne,nγ) reactions. The Doppler corrected energies for transitions in 224Rn and 226Rn together with the deduced level energies are given in Table 1.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The software used to sort the raw data is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2593370 (Gaffney, L. P. & Konki, J., MiniballCoulexSort for Coulex, SPEDE, CREX and TREX). Information about the ROOT software package used to analyse the data can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2009.08.005.

Change history

09 October 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Butler, P. A. & Nazarewicz, W. Intrinsic reflection asymmetry in atomic nuclei. Rev. Mod. Phys. 68, 349–421 (1996).

Spevak, V., Auerbach, N. & Flambaum, V. V. Enhanced T-odd, P-odd electromagnetic moments in reflection asymmetric nuclei. Phys. Rev. C. 56, 1357–1369 (1997).

Dobaczewski, J. & Engel, J. Nuclear time-reversal violation and the Schiff moment of 225Ra. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 232502 (2005).

Ellis, J., Lee, J. & Pilaftsis, A. Maximal electric dipole moments of nuclei with enhanced Schiff moments. J. High. Energy Phys. 2011, 045 (2011).

Butler, P. A. Octupole collectivity in nuclei. J. Phys. G. Nucl. Part. Phys. 43, 073002 (2016).

Gaffney, L. P. et al. Studies of pear-shaped nuclei using accelerated radioactive beams. Nature 497, 199–204 (2013).

Wollersheim, H. J. et al. Coulomb excitation of 226Ra. Nucl. Phys. A. 556, 261–280 (1993).

Bishop, M. et al. Improved limit on the 225Ra electric dipole moment. Phys. Rev. C. 94, 025501 (2016).

Dzuba, V. A., Flambaum, V. V., Ginges, J. S. M. & Kozlov, M. G. Electric dipole moments of Hg, Xe, Rn, Ra, Pu, and TlF induced by the nuclear Schiff moment and limits on time-reversal violating interactions. Phys. Rev. A. 66, 012111 (2002).

Dobaczewski et al. Correlating Schiff moments in the light actinides with octupole moments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 232501 (2018).

Tardiff, E. R. et al. Polarization and relaxation rates of radon. Phys. Rev. C. 77, 052501(R) (2008).

Rand, E. T. et al. Geant4 developments for the radon electric dipole moment search at TRIUMF. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 312, 102013 (2011).

Tardiff, E. R. et al. The radon EDM apparatus. Hyperfine. Interact. 225, 197–206 (2014).

Behr, J. A. & Gwinner, G. Standard model tests with trapped radioactive atoms. J. Phys. G. Nucl. Part. Phys. 36, 033101 (2009).

Engel, J., Ramsey-Musolf, M. J. & van Kolck, U. Electric dipole moments of nucleons, nuclei, and atoms: the standard Model and beyond. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 71, 21–74 (2013).

Yamanaka, N. et al. Probing exotic phenomena at the interface of nuclear and particle physics with the electric dipole moments of diamagnetic atoms: a unique window to hadronic and semi-leptonic CP violation. Eur. Phys. J. A 53, 54 (2017).

Chupp, T. E., Fierlinger, P., Ramsey-Musolf, M. J. & Singh, J. T. Electric dipole moments of atoms, molecules, nuclei, and particles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 015001 (2019).

Warr, N. et al. The Miniball spectrometer. Eur. Phys. J. A 49, 40 (2013).

Ostrowski, A. et al. CD: a double sided silicon strip detector for radioactive nuclear beam experiments. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 480, 448–455 (2002).

Singh, S., Jain, A. & Tuli, J. K. Nuclear data sheets for A = 222. Nucl. Data Sheets 112, 2851–2886 (2011).

Ward, D. et al. Rotational bands in 238U. Nucl. Phys. A. 600, 88–110 (1996).

Wiedenhöver, I. et al. Octupole correlations in the Pu isotopes: from vibration to static deformation? Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 2143–2146 (1999).

Cocks, J. F. C. et al. Spectroscopy of Rn, Ra and Th isotopes using multi-nucleon transfer reactions. Nucl. Phys. A. 645, 61–91 (1999).

Nazarewicz, W. et al. Analysis of octupole instability in medium-mass and heavy nuclei. Nucl. Phys. A. 429, 269–295 (1984).

Robledo, L. M. & Butler, P. A. Quadrupole-octupole coupling in the light actinides. Phys. Rev. C. 88, 051302(R) (2013).

Agbemava, S. E., Afanasjev, A. V. & Ring, P. Octupole deformation in the ground states of even-even nuclei: a global analysis within the covariant density functional theory. Phys. Rev. C. 93, 044304 (2016).

Möller, P. et al. Axial and reflection asymmetry of the nuclear ground state. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 94, 758–780 (2008).

Robledo, L. M. & Bertsch, G. F. Electromagnetic transition strengths in soft deformed nuclei. Phys. Rev. C. 86, 054306 (2012).

Vermeer, W. J. et al. Octupole correlation effects in 151Pm. Phys. Rev. C. 42, R1183–R1186 (1990).

Wiśniewski, J. et al. Parity-doublet structure in the 147La nucleus. Phys. Rev. C. 96, 064301 (2017).

Auerbach, N. et al. Nuclear Schiff moment in nuclei with soft octupole and quadrupole vibrations. Phys. Rev. C. 74, 025501 (2006).

Penescu, L., Catherall, R., Lettry, J. & Stora, T. Development of high efficiency versatile arc discharge ion source at CERN ISOLDE. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 81, 02A906 (2010).

Wolf, B. H. et al. First radioactive ions charge bred in REXEBIS at the REX-ISOLDE accelerator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 204, 428–432 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Niels Bidault, Eleftherios Fadakis, Erwin Siesling, and Fredrick Wenander who assisted with the preparation of the radioactive beams, and we thank Jacek Dobaczewski for useful discussions. The support of the ISOLDE Collaboration and technical teams is acknowledged. This work was supported by the following Research Councils and Grants: Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC; UK) grants ST/P004598/1, ST/L005808/1; Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; Germany) grants 05P18RDCIA, 05P15PKCIA and 05P18PKCIA and the “Verbundprojekt 05P2018”; National Science Centre (Poland) grant 2015/18/M/ST2/00523; European Union’s Horizon 2020 Framework research and innovation programme 654002 (ENSAR2); Marie Skłodowska-Curie COFUND grant (EU-CERN) 665779; Research Foundation Flanders (FWO, Belgium), by GOA/2015/010 (BOF KU Leuven) and the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Programme initiated by the Belgian Science Policy Office (BriX network P7/12); RFBR(Russia) grant 17-52-12015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.A.B., T.C., L.P.G., M.Sc., N.W. and M.Z. prepared the proposal for the experiment, K.A., H.D.W., L.P.G., A.I., J.K., P.R., D.R., M.Se., V.V., and N.W. set up the instrumentation, L.P.G., K.J., M.L., J.A.R., and S.R. prepared the radioactive beams, M.B., P.A.B., J.C., G.D.A., L.P.G., P.E.G., A.G., C.H., D.T.J., J.M.K., N.A.K., M.K., J.K., T.K., B.N.S., D.O.D., J.O., R.D.P., L.G.P., C.R., M.Sc., T.S., B.S., J.Si., J.F.S., P.S., M.St., S.V., V.V., N.W., K.W.L., M.Z. monitored the detector, data acquisition and radioactive beam systems, P.A.B., L.P.G., J.K., J.F.S., P.S., P.V.D., and N.W. carried out the data analysis and interpretation of the data, and P.A.B., T.C., G.D.A., L.P.G., J.K., T.K., B.N.S., J.O., M.Sc., J.F.S., P.S., P.V.D., N.W., and K.W.L. prepared the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications would like to thank Peter Ring and other anonymous reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Butler, P.A., Gaffney, L.P., Spagnoletti, P. et al. The observation of vibrating pear-shapes in radon nuclei. Nat Commun 10, 2473 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10494-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10494-5

This article is cited by

-

Nuclear shell-model simulation in digital quantum computers

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Misconceptions, Knowledge, and Attitudes Towards the Phenomenon of Radioactivity

Science & Education (2022)

-

Gamma-ray spectroscopy of fission fragments with state-of-the-art techniques

La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento (2022)

-

Young African universities take the lead

Nature Physics (2021)

-

Partial dynamical symmetry versus quasi dynamical symmetry examination within a quantum chaos analyses of spectral data for even–even nuclei

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.