Abstract

Dendrimers are homostructural and highly branched macromolecules with unique dendritic effects and extensive use in multidisciplinary fields. Although thousands of dendrimers have been synthesized in solution, the on-surface synthetic protocol for planar dendrimers has never been explored, limiting the elucidation of the mechanism of dendritic effects at the single-molecule level. Herein, we describe an on-surface synthetic approach to planar dendrimers, in which exogenous palladium is used as a catalyst to address the divergent cross-coupling of aryl bromides with isocyanides. This reaction enables one aryl bromide to react with two isocyanides in sequential steps to generate the divergently grown product composed of a core and two branches with high selectivity and reactivity. Then, a dendron with four branches and dendrimers with eight or twelve branches in the outermost shell are synthesized on Au(111). This work opens the door for the on-surface synthesis of various planar dendrimers and relevant macromolecular systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

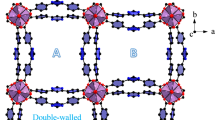

Dendrimers are a unique class of nanosized macromolecules featuring homostructural and highly branched architectures1. As shown in Fig. 1a, the structure of a dendritic macromolecule is composed of three main parts: (1) a central core moiety, (2) interior layers made of divergently growing branch units attached to the core, and (3) terminal functionalities distributed at the outermost space. Thus, repeated fine-tuning of architectural variations enables the optimization of dendrimers for specific applications by the introduction of different functional moieties.

On-surface synthesis of planar dendrimers via DCR. a The general structure of a dendrimer. b On-surface coupling reactions. c On-surface synthesis of planar dendron (2) with four branches and dendrimers (3 and 4) with eight and twelve branches (the products might be surface-bonded radicals or hydrogenated species)

Ever since the first cascade molecules, and nee dendrimers reported by Vögtle et al. in 19782, thousands of dendrimers have been developed in solution3,4,5, which exhibit a variety of unique dendritic effects and lead to extensive use in multidisciplinary fields6,7,8,9,10,11,12. In general, the synthesis of a dendrimer starts from a functionalized core and proceeds by divergent growth via sequential reactions. The growing reactions should generate two or more new branches from a single reactive site to form the dendritic architecture, and the reaction selectivity and reactivity must be very high to guarantee the complete conversion of multiple reactive sites to avoid defects.

Dendrimers synthesized in solution stretch in three-dimensions and the configurations of the numerous components are very complicated and chaotic. In contrast, planar dendrimers synthesized in situ on surfaces could afford unambiguous configurations in the two-dimensional confined space, which are beneficial to elucidate the mechanism of dendritic effects at the single-molecule level and produce highly ordered, self-assembled structures. In addition, the in situ synthesis of dendrimers on surfaces solves the problems of solubility and sublimation caused by their high molecular weight.

However, the synthesis of planar dendrimers on surfaces has not been achieved yet due to the lack of a practicable on-surface synthesis method. The main challenges include (1) development of an on-surface divergent cross-coupling reaction (DCR), which enables the generation of two or more new branches from one reactive site, (2) achievement of sufficiently high selectivity of the cross-coupling with complete inhibition of the homo-coupling, and (3) achievement of sufficiently high reactivity of the cross-coupling to ensure complete conversion of the multiple reactive sites.

After a pioneering study in 200713, on-surface homo-coupling reactions have been extensively developed in various versions (Fig. 1b, I)14, including dehalogenations15,16,17,18,19,20, decarboxylations21, and dehydrogenations22,23,24,25,26, among others27,28,29. In addition, on-surface cross-coupling reactions have also been achieved (Fig. 1b, II), mainly involving the reaction of aryl bromides with porphyrin bromides30, alkynes31,32,33,34,35, and alkenes36, although the reaction selectivity is usually poor. So far, on-surface coupling reactions are all limited in their reaction pattern to the generation of only one new covalent bond, which can only connect one fragment (A) with another fragment (A or B) to generate A–A or A–B structures (Fig. 1b, I and II). An on-surface coupling reaction generating two new bonds to connect one A with two B groups to form A–2B has never been reported (Fig. 1b, III).

Isocyanides are a unique class of building blocks in organic synthesis. Their terminal carbon atom has one pair of electrons and an empty orbital, therefore, enabling reactions with both nucleophiles and electrophiles at the same carbon atom. The reactions of isocyanides in solution have been extensively explored37, but they have never been used in on-surface coupling reactions to date.

Herein, we report a cross-coupling of aryl bromides with isocyanides on a Au(111) surface using exogenous palladium as a catalyst. Surprisingly, one aryl bromide can react with two isocyanides to generate a divergent cross-coupling product (1) with one core and two branches. Due to the high selectivity and reactivity of this reaction, a planar dendron (2) with four isocyanide-derived branches and dendrimers (3 and 4) with eight and twelve isocyanide-derived branches have been successfully synthesized on a surface (Fig. 1c). These products can undergo further self-assembly to form highly ordered structures.

Results

On-surface DCR on Au(111)

As the first step of our investigations, 5-(4-bromophenyl)-10,15,20-triphenylporphyrin (Br-TPP) and 4-isocyano-1,1′-biphenyl (ICBP) were selected as the precursors (Fig. 2a) for the on-surface reaction on Au(111). The experimental results showed that no cross-coupling occurred between the porphyrin derived aryl bromide and isocyanide on Au(111) after annealing to 403 K (see Supplementary Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that the homo-coupling of aryl bromide or isocyanide could also not be observed, and isocyanide desorbed at this annealing temperature38. Palladium is one of the most efficient and versatile catalysts in solution, especially in cross-coupling reactions39. So, exogenous Pd was tested as the catalyst for the reaction of aryl bromide and isocyanide, with the hope of enhancing cross-coupling activity while inhibiting the homo-coupling of the two precursors.

DCR of one Br-TPP with two ICBP on Au(111). a DCR used to generate S-1 and R-1. b STM image of the product generated from DCR. c STM image of self-assembled molecules of S-1. d STM image of self-assembled molecules of R-1. e STM image of mixed molecules of S-1 and R-1. f–h Statistical analysis for the DCR of Br-TPP with ICBP at different coverages of Br-TPP (f, reaction conditions: 403 K, 1 h), different annealing temperatures (g, reaction conditions: ~0.4 ML Br-TPP, 1 h), and different annealing time (h, reaction conditions: ~0.4 ML Br-TPP, 403 K). DCR: the reaction of one Br-TPP with two ICBP. CR: the reaction of one Br-TPP with one ICBP. NR: no coupling reaction. Scale bars: b 3 nm. c–e 1 nm. Tunneling parameters: b, c, e I = −0.49 nA, U = −1.72 V. d I = −0.66, U = −1.78 V

A submonolayer of Br-TPP molecules (see Supplementary Fig. 3a) and an excess of ICBP molecules (see Supplementary Fig. 4a) were successively deposited onto a pristine Au(111) surface (see Supplementary Fig. 4b) maintained at approximately 250 K inside a commercial ultra-high vacuum (UHV) system (base pressure: ~2 × 10−10 mbar) equipped with a variable-temperature scanning tunneling microscope (STM; SPECS, Aarhus 150). Pd atoms were subsequently dosed onto the Au(111) surface (see Supplementary Fig. 4c). The results demonstrate that the alternative arrangement of ICBP and Br-TPP was mostly retained after the Pd deposition and Pd clusters scattered in the molecules. Such miscibility of the reactants is crucial for the high selectivity of the DCR. After annealing at 403 K for 1 h, the sample was cooled to 120 K for STM analysis. Surprisingly, no homo-coupling products were observed under these conditions, and the DCR demonstrates high selectivity and reactivity. These results demonstrate that exerting kinetic control via diluted reactant conditions inhibits homo-coupling products, thereby kinetically selecting the DCR product.

Figure 2b shows the close-packed product molecules generated from the reaction of Br-TPP and ICBP, arranged in a herringbone-like pattern. The resulting highly ordered self-assembly tends to align with [11\(\bar 2\)] and the equivalent directions of the substrate. The high-resolution STM images (Fig. 2c–e) reveal that the backbone of the aligned structure can be attributed to the porphyrin moiety (circled by the blue line in Fig. 2c) derived from the Br-TPP precursor. One V-shaped branch (circled by the white line in Fig. 2c) is attached to the porphyrin moiety, originating from two ICBP precursor molecules. Interestingly, the products were observed in a staggered arrangement, with the V-shaped branches arrayed on both sides. The structural characteristics of the product suggest that the divergent cross-coupling of one Br-TPP molecule with two ICBP molecules occurred on Au(111) to generate 1 with one core and two branches. Through the comparison of experimental STM images with the simulated images based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations (the adsorption models and simulated image, see Supplementary Fig. 5), the structure of 1 is proposed as indicated in Fig. 2a.

It is noteworthy that 1 is a prochiral molecule. According to the direction of rotation of the two branches on the surface, we defined the anti-clockwise species as S-1 and the clockwise species as R-1 (Fig. 2a). Figure 2c, d shows the two pure phases of self-assembled S-1 and R-1, respectively. The self-assembly pattern mixing S-1 and R-1 could be found occasionally (Fig. 2e), but no pure phase could form such a pattern, probably due to self-assembly mismatching.

To further demonstrate the selectivity of the DCR, we performed statistical analysis for the systematic exploration of the coverage of Br-TPP, annealing temperature and time, in which homo-coupling product was not counted due to the low abundance of <2% (Fig. 2f–h). As shown in Fig. 2f, the abundance of 1 slightly decreased when the coverage of Br-TPP increased from 0.2 ML to 0.6 ML. Once the coverage increased to 0.8 ML, the abundance of 1 dramatically decreased and most molecules were TPP species without coupling, accompanied by a very small amount of homo-coupling product TPP-TPP (see Supplementary Fig. 6). This result might be attributed to the high surface coverage that led to the compactly packed porphyrins and hampered both the cross- and homo-coupling reactions. Figure 2g shows that an annealing temperature of 378 K led to a slightly lower abundance of 1, while lowering the annealing temperature to 353 K dramatically decreased the abundance of 1. In contrast, enhancement of the annealing temperature demonstrated no obvious influence on the reaction. The results indicated that the reaction possesses good tolerance to the coverage of Br-TPP and annealing temperature. The investigation of annealing time at 403 K showed that the reaction was rather fast, and the abundance of the product was 77% after 10 min and increased to 82% after 15 min (Fig. 2h). The control experiment for Pd-catalyzed homo-coupling of Br-TPP without ICBP at 403 K for 15 min was carried out and approximate 10% abundance of homo-coupling product TPP-TPP was obtained in lower coverage of Br-TPP (~0.2 ML), similar with our former study performed in Omicron system40, although the system error in temperature measurement may exist between two setups. Moreover, the higher coverage of Br-TPP (~0.8 ML) led to lower abundance of TPP-TPP due to the surface coverage. The results suggested that the homo-coupling reaction of Br-TPP is sluggish, because the C–C bond formation, rather than the debromination step, is the rate-limiting step40. In contrast, the coupling step in DCR is fast, which guarantees the high selectivity of the reaction with the inhibition of the homo-coupling reactions.

To further elucidate the structure of 1 on Au(111), ex situ time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) was performed to determine the molecular weight of the products. Figure 3a shows the mass spectrum of the positive ions obtained from a sample of the Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling on Au(111) with an m/z range from 300 to 1250. The distinct peak at m/z = 971.39 amu corresponds accurately to the molecular ion peak of 1 (C70H47N6+ [M1]+, the calculated value is 971.39), and the experimental isotopic distribution of [M1]+ agrees well with the theoretical isotopic distribution (Fig. 3b). According to the general principles of molecular ionization for ToF-SIMS experiments, hydrogenated product of 1 on Au(111) may lose an electron or gain a proton to generate positive ions41, which would afford the corresponding peaks at m/z = 972.39 or 973.40, respectively. The peak observed at m/z = 971.39 suggests that 1 should consist of a radical bonded with the Au(111) surface rather than a hydrogenated product.

ToF-SIMS analysis of 1 on Au(111). a ToF-SIMS spectrum showing the molecular weight of positive ions (coverage of Br-TPP: ~0.5 ML). M1: molecular weight of divergent cross-coupling product 1; MCR: molecular weight of cross-coupling product of one Br-TPP with one ICBP; MTPP: molecular weight of debrominated product of Br-TPP. b Experimental and simulated isotopic distribution of [M1]+ ions of 1

It is noteworthy that the lower abundance peaks at m/z = 794.33 and 615.25 amu correspond accurately to the quasi-molecular ion peaks (see Supplementary Fig. 7) for the partially branched product of the cross-coupling of one Br-TPP with one ICBP (C57H40N5+, [MCR + H]+, calculated value is 794.33) and the debrominated product of Br-TPP (C44H31N4+, [MTPP + H]+, calculated value is 615.25), respectively. In contrast, molecular ion peak of the homo-coupling product of Br-TPP (C88H59N8+ [MTPP-TPP + H]+, the calculated value is 1227.49) was not observed (see Supplementary Fig. 8).

Mechanism of on-surface DCR

In order to unravel the reaction mechanism and elucidate the origin of the high selectivity of DCR, we performed DFT calculations to determine the energy of the initial debromination and two subsequent addition steps using simplified bromobenzene and isocyanobenzene as model precursors (Fig. 4). Figure 4a shows the Pd adatom-promoted debromination step from bromobenzene (IS1) to a benzene radical intermediate (Int1) on the surface of Au(111). The reaction energy barrier was determined to be 0.70 eV, which is in good agreement with the experimental reaction temperature. In comparison, the reaction energy barrier for the debromination step without Pd on Au(111) is 1.02 eV42, which indicates the key role played by the exogenous Pd catalyst to decrease the reaction barrier in the debromination step.

Mechanism for the divergent cross-coupling of aryl bromide with isocyanide on Au(111). a–c DFT-calculated energy levels and molecular structures for a debromination of bromobenzene, b the first addition of a benzene radical to isocyanobenzene, and c the second addition of an imidoyl radical to another isocyanobenzene. Top and side views of the initial state (IS), transition state (TS), intermediate state (Int), and final state (FS) of the reactions are shown below the energy diagrams. d Overview of the reaction mechanism

Figure 4b shows the first addition process of a benzene radical to isocyanobenzene in order to generate an imidoyl radical intermediate (Int2). The reaction energy barrier assisted by the Au(111) surface was found to be 0.24 eV, suggesting that this addition occurs spontaneously after the debromination step. For the Pd adatom-promoted addition of a benzene radical to isocyanobenzene, a higher reaction barrier energy of 0.46 eV (see Supplementary Fig. 9) was calculated, suggesting that Au(111) surface assistance without a Pd adatom is the preferred pathway for this addition step. In addition, the reaction energy of this exothermic step was found to be 1.85 eV, reflecting the irreversibility of the C–C bond formation. Similarly, the reaction barrier for the second addition of an imidoyl radical intermediate to another isocyanobenzene was determined to be 0.49 eV on Au(111) (Fig. 4c), affording the final product (FS) as a radical bonded with the Au(111) surface. The higher reaction barrier of the second addition step compared to the first addition step might be ascribed to steric hindrance.

Based on the DFT calculations, a reaction mechanism for the divergent cross-coupling of aryl bromide with isocyanide on Au(111) is proposed as depicted in Fig. 4d, in which the debromination step is the rate-limiting step. This contrasts with our previous study on the Pd-catalyzed Ullmann homo-coupling of porphyrin-substituted aryl bromide (Br2-TPP) on Au(111), where C–C bond formation rather than the debromination step, was determined to be the rate-limiting step at high temperature. That was concluded by analyzing the isothermic reaction series and determining the bond concentration as a function of reaction temperature and duration40. Thus, the high selectivity of the divergent cross-coupling of Br-TPP with ICBP may be tentatively explained by the difference in reaction kinetics. For the divergent cross-coupling of Br-TPP with excessive ICBP, once the rate-limiting debromination of Br-TPP occurs, the subsequent two addition steps to ICBP will proceed spontaneously to yield final product 1, while the homo-coupling of Br-TPP may be inhibited by the rate-limiting C–C formation step.

On-surface synthesis of planar dendron and dendrimers via DCR

The divergent cross-coupling of Br-TPP with ICBP achieved on Au(111) has three distinctive features: (1) the unique pattern enables the generation of one core and two branches, (2) high cross-coupling selectivity with complete inhibition of the homo-coupling, and (3) high cross-coupling reactivity with up to 89% abundance. These features successfully meet the challenges posed by the on-surface synthesis of planar dendrons and dendrimers.

For the on-surface synthesis of planar dendrons and dendrimers, two porphyrin precursors, Br2-TPP and Br4-TPP, containing two and four aryl bromides substituents, respectively, were prepared and applied to the Pd-catalyzed DCR on Au(111) (Fig. 5a, e). The STM images for the mixtures of the porphyrins with ICBP before and after Pd deposition are presented in Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11. Under reaction conditions similar to those used to form 1, the on-surface reaction of one molecule of Br2-TPP and four molecules of ICBP readily proceeded to generate dendron 2 containing one porphyrin core and four branches. It is noteworthy that the selectivity was also very high, and no homo-coupling products were observed in this reaction (the large-scale STM image is presented in Supplementary Fig. 10c). As shown in the STM image, Fig. 5b, dendron 2 formed close-packed molecular islands, in which the molecules self-assembled to afford aligned herringbone-like structures similar to the self-assembled structure of 1. From the high-resolution STM images (Fig. 5c, d), dendron 2 in the trans-configuration could be distinguished as R,R-2 and S,S-2. Interestingly, the cis-dendron 2 could barely be observed in the reaction, which demonstrates the high selectivity of the reaction on the surface.

On-surface synthesis of planar dendron and dendrimers. a Schematic representation of DCR used to generate dendrons R,R-2 and S,S-2. b STM image of self-assembled dendron 2 on Au(111). c STM image of self-assembled dendron R,R-2. d STM image of self-assembled dendron S,S-2. e Schematic representation of DCR used to generate dendrimer 3 on Au(111). f STM image of dendrimer 3. The inset represents a close-up image of a single dendrimer 3. g Schematic representation of DCR used to generate dendrimer 4 on Au(111). h STM image of dendrimer 4. The inset represents a close-up image of a single dendrimer 4. The dendron 2, dendrimers 3 and 4 might be surface-bonded radicals or hydrogenated species. Scale bars: b 3 nm. c, d and inset of (f, h) 1 nm. f 2 nm. h 2 nm. Tunneling parameters. b, c I = −0.11 nA, U = −1.80 V. d I = −0.17 nA, U = −1.67 V. f I = −0.52 nA, U = −1.52 V. h I = 0.49 nA, U = 1.74 V

As shown in the STM image (Fig. 5f), dendrimer 3, with a crab-like structure, was also readily achieved on Au(111) through the Pd-catalyzed divergent cross-coupling of one Br4-TPP with eight ICBP molecules. Notably, no homo-coupling reaction of Br4-TPP was observed and the reactivity of the cross-coupling reaction was very high, yielding isolated molecules of dendrimer 3 all containing one porphyrin core and eight branches (the large-scale STM image is presented in Supplementary Fig. 11c).

To achieve the on-surface synthesis of planar dendrimer with a larger size on a two-dimensional surface, we synthesized the Br6-B10 precursor including six aryl bromides as the reactive sites, with the hope of achieving the space-crowded dendrimer 4 with 12 branches (Fig. 5g). After the successive deposition of Br6-B10, ICBP and Pd (see Supplementary Fig. 12a) and annealing at 403 K for 1 h, dendrimer 4 with 12 symmetrical antennae was generated on Au(111) surface, as shown in Fig. 5h. Such a planar dendrimer may possess better conjugate properties because the dihedral angle between the adjacent benzene rings is significantly reduced in comparison with the dendrimers stretched in three-dimensional space. The large-scale STM image (see Supplementary Fig. 12b) suggests that the reaction selectivity was poor, and defects were prevalent in the products due to the crowdedness and strong steric hindrance in the two-dimensional confined space, which severely hampered the DCR. The results indicate that surface coverage is crucial for the on-surface synthesis of planar dendrimers. Noted that excess of hydrogen in the chamber might passive the surface-bonded radicals of the products to generate the hydrogenated species.

Discussion

We have achieved the on-surface divergent growth reaction via cross-coupling of one molecule of aryl bromide with two molecules of isocyanide on Au(111), generating a product containing a core and two branches. Exogenous palladium has been used as a catalyst to promote the DCR with high selectivity and reactivity. Statistical analysis demonstrated that the reaction possesses good tolerance to the coverage and annealing temperature. The structure of the product incorporating a porphyrin core and two isocyanide-derived branches has been confirmed through STM measurements at single-molecule resolution and ToF-SIMS determination of the accurate molecular weight. The DFT calculations suggest that the reaction proceeds via palladium adatom-promoted C–Br activation and sequential addition to two isocyanides. The C–Br activation is the rate-limiting step, which guarantees the high selectivity of the cross-coupling. On the basis of this reaction, a planar dendron with four branches and dendrimers with eight and twelve branches have been synthesized on Au(111) surface in orderly self-assembled patterns. Our results demonstrate a promising protocol for the synthesis of a variety of planar dendrons and dendrimers with diverse structures and functionalities, which might offer great opportunities for future investigations on dendritic effects at the single-molecule level and the applications in functional materials and nano-devices.

Methods

Experimental measurement

All experiments were conducted using commercial UHV system (base pressure 2 × 10−10 mbar) equipped with a variable temperature scanning tunneling microscope (SPECS, Aarhus 150), a molecular evaporator, a metal evaporator and standard facilities for sample preparation. The single-crystalline Au(111) surfaces were cleaned by cycles of argon-ion sputtering and annealing. Imaging was performed in constant current mode, with the bias voltage given with respect to the sample at ~120 K. The precursor ICBP was deposited through a leak valve onto the substrates. Precursors Br-TPP, Br2-TPP, Br4-TPP, and Br6-B10 were evaporated from a quartz crucible onto metal/semimetal surfaces, and the sublimation temperatures for precursors Br-TPP, Br2-TPP, Br4-TPP, and Br6-B10 were 165, 175, 185, and 230 °C, respectively. Palladium atoms were dosed by electron beam evaporation from a Pd rod. ToF-SIMS experiments were performed using a ToF-SIMS V spectrometer (IONTOF GmbH, Münster, Germany). A pulsed 30 keV Bi3+ ion beam was used as the primary ion beam for all measurements. The analysis area was 500 × 500 μm. Target current was 1 pA. All data were obtained and analyzed using the IONTOF instrument software. Positive mass spectra were calibrated using C+, CH+, CH2+, and C2+ peaks.

General procedures for the preparation of sample

An excess of ICBP precursors (~0.8–1.0 ML) were deposited onto a pristine Au(111) surface held at approximately 250 K. Then, a submonolayer of aryl bromide precursor (Br-TPP, Br2-TPP, Br4-TPP, or Br6-B10) was deposited onto the Au(111) surface at approximately 250 K. Next, a submonolayer (~0.1 ML) of Pd atoms was dosed onto the sample containing two precursors at approximately 250 K. Then, the sample was annealed to indicated temperature for indicated time and cooled to 120 K for STM analysis.

Theoretical calculation

DFT calculations were performed with the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP)43, 44, using the projector-augmented wave method45, 46. We used the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) formalism to treat exchange-correlation interaction47, and van der Waals (vdW) interactions were considered by using the DFT-D3 developed by Grimme48. The initial debromination was performed on Au(111) surface (5 × 5), which is different from (4 × 5) in our former report36. The two subsequent addition steps were performed on Au(111) surface (5 × 5) and (7 × 7), respectively. Transition-state calculations according to the nudged elastic band and the climbing-image nudged elastic band was applied to locate the transition state49. STM simulation was performed using the Tersoff–Hamann approximation50.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Extra data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Vögtle, F., Richardt, G. & Werner, N. Dendrimer Chemistry: Concepts, Synthesis, Properties, Applications (Wiley, Weinheim, Germany, 2009).

Buhleier, E., Wehner, W. & Vögtle, F. “Cascade”- and “nonskid-chain-like” syntheses of molecular cavity topologies. Synthesis 1978, 155–158 (1978).

Newkome, G. R. & Shreiner, C. D. Poly(amidoamine), polypropylenimine, and related dendrimers and dendrons possessing different 1→2 branching motifs: an overview of the divergent procedures. Polymer 49, 1–173 (2008).

Li, W.-S. & Aida, T. Dendrimer porphyrins and phthalocyanines. Chem. Rev. 109, 6047–6076 (2009).

Newkome, G. R. & Shreiner, C. Dendrimers derived from 1→3 branching motifs. Chem. Rev. 110, 6338–6442 (2010).

Bauer, R. E., Grimsdale, A. C. & Müllen, K. Functionalised polyphenylene dendrimers and their applications. Top. Curr. Chem. 245, 253–286 (2005).

Burn, P. L., Lo, S.-C. & Samuel, I. D. W. The development of light-emitting dendrimers for displays. Adv. Mater. 19, 1675–1688 (2007).

Lo, S.-C. & Burn, P. L. Development of dendrimers: macromolecules for use in organic light-emitting diodes and solar cells. Chem. Rev. 107, 1097–1116 (2007).

Li, J. & Liu, D. Dendrimers for organic light-emitting diodes. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 7584–7591 (2009).

Astruc, D., Boisslier, E. & Ornelas, C. Dendrimers designed for functions: from physical, photophysical, and supramolecular properties to applications in sensing, catalysis, molecular electronics, photonics, and nanomedicine. Chem. Rev. 110, 1857–1959 (2010).

Mignani, S., Kazzouli, S. E., Bousmina, M. M. & Majoral, J.-P. Dendrimer space exploration: an assessment of dendrimers/dendritic scaffolding as inhibitors of protein–protein interactions, a potential new area of pharmaceutical development. Chem. Rev. 114, 1327–1342 (2014).

Mignani, S. et al. Dendrimers in combination with natural products and analogues as anti-cancer agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 514–532 (2018).

Grill, L. et al. Nano-architectures by covalent assembly of molecular building blocks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 687–691 (2007).

Dong, L., Liu, P. N. & Lin, N. Surface-activated coupling reactions confined on a surface. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 2765–2774 (2015).

Wang, W., Shi, X., Wang, S., Van Hove, M. A. & Lin, N. Single-molecule resolution of an organometallic intermediate in a surface-supported Ullmann coupling reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13264–13267 (2011).

Shi, K. J. et al. Ullmann reaction of aryl chlorides on various surfaces and the application in stepwise growth of 2D covalent organic frameworks. Org. Lett. 18, 1282–1285 (2016).

Sun, Q. et al. On-surface formation of cumulene by dehalogenative homocoupling of alkenyl gem-dibromides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 12165–12169 (2017).

Sun, Q. et al. Direct formation of C–C triple-bonded structural motifs by on-surface dehalogenative homocouplings of tribromomethyl-substituted arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4035–4038 (2018).

Shu, C.-H. et al. On-surface synthesis of poly(p-phenylene ethynylene) molecular wires via in situ formation of carbon–carbon triple bond. Nat. Commun. 9, 2322 (2018).

Cai, L. et al. Direct formation of C–C double-bonded structural motifs by on-surface dehalogenative homocoupling of gem-dibromomethyl molecules. ACS Nano 12, 7959–7966 (2018).

Gao, H.-Y. et al. Decarboxylative polymerization of 2,6-naphthalenedicarboxylic acid at surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9658–9663 (2014).

Zhong, D. et al. Linear alkane polymerization on a gold. Surf. Sci. 334, 213–216 (2011).

Zhang, Y.-Q. et al. Homo-coupling of terminal alkynes on a noble metal surface. Nat. Commun. 3, 1286 (2012).

Gao, H.-Y. et al. Glaser coupling at metal surfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 4024–4028 (2013).

Sun, Q. et al. Dehydrogenative homocoupling of terminal alkenes on copper surfaces: a route to dienes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 4549–4552 (2015).

Li, Q. et al. Surface-controlled mono/diselective ortho C–H bond activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2809–2814 (2016).

Sun, Q. et al. On-surface formation of one-dimensional polyphenylene through Bergman cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 8448–8451 (2013).

Arado, O. D. et al. On-surface reductive coupling of aldehydes on Au(111). Chem. Commun. 51, 4887–4890 (2015).

Liu, L. et al. α-Diazo ketones in on-surface chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 6000–6005 (2018).

Kuang, G. et al. Cross-coupling of aryl-bromide and porphyrin-bromide on an Au(111) Surface. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 8028–8032 (2015).

Kanuru, V. K. et al. Sonogashira coupling on an extended gold surface in vacuo: reaction of phenylacetylene with iodobenzene on Au(111). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 8081–8086 (2010).

Sánchez-Sánchez, C. et al. The flexible surface revisited: adsorbate-induced reconstruction, homocoupling, and Sonogashira cross-coupling on the Au(100) surface. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 11677–11684 (2014).

Sanchez-Sanchez, C. et al. Sonogashira cross-coupling and homocoupling on a silver surface: chlorobenzene and phenylacetylene on Ag(100). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 940–947 (2015).

Zhang, R., Lyu, G., Li, D. Y., Liu, P. N. & Lin, N. Template-controlled Sonogashira cross-coupling reactions on a Au(111) surface. Chem. Commun. 53, 1731–1734 (2017).

Wang, T. et al. Kinetic strategies for the formation of graphyne nanowires via Sonogashira coupling on Ag(111). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 13421–13428 (2018).

Shi, K.-J. et al. On-surface Heck reaction of aryl bromides with alkene on Au(111) with palladium as catalyst. Org. Lett. 19, 2801–2804 (2017).

Boyarskiy, V. P., Bokach, N. A., Luzyanin, K. V. & Kukushkin, V. Y. Metal-mediated and metal-catalyzed reactions of isocyanides. Chem. Rev. 115, 2698–2779 (2015).

Boscoboinik, J. A. et al. One-dimensional supramolecular surface structures: 1,4-diisocyanobenzene on Au(111) surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 11624–11629 (2010).

Molnár, Á. Efficient, selective, and recyclable palladium catalysts in carbon–carbon coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 111, 2251–2320 (2011).

Adisoejoso, J. et al. A single-molecule-level mechanistic study of Pd-catalyzed and Cu-catalyzed homocoupling of aryl bromide on an Au(111) surface. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 4111–4116 (2014).

Benninghoven, A. Chemical analysis of inorganic and organic surfaces and thin films by static Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 33, 1023–1043 (1994).

Björk, J., Hanke, F. & Stafström, S. Mechanisms of halogen-based covalent self-assembly on metal surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5768–5775 (2013).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 48, 13115–13118 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17963–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jonsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Tersoff, J. & Hamann, D. R. Theory of the scanning tunneling microscope. Phys. Rev. B 31, 805–813 (1985).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Xiao-Hui Qiu in National Center for Nanoscience and Technology for his insightful suggestions to this work. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Nos. 21421004, 21561162003, 21672059, and 91845110), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 2018SHZDZX03), the Programme of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (B16017), Program of the Shanghai Committee of Sci. & Tech. (Project No. 18520760700), and the Program for Eastern Scholar Distinguished Professor. The calculations were performed on TianHe-1 (A) at National Supercomputer Center in Tianjin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.-Y.L., S.-W.L., and Y.-L.X. performed the STM experiments. D.-Y.L. and S.-W.L. conducted theoretical computations. A.W. synthesized the molecules. X.H. and Y.-T.L. performed the ToF-SIMS experiments. D.-Y.L., S.-W.L., and P.-N.L. analyzed the data. P.-N.L. planned and supervised the project and all work. All authors discussed the results and helped in writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, DY., Li, SW., Xie, YL. et al. On-surface synthesis of planar dendrimers via divergent cross-coupling reaction. Nat Commun 10, 2414 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10407-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10407-6

This article is cited by

-

Universal inter-molecular radical transfer reactions on metal surfaces

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Steering on-surface reactions through molecular steric hindrance and molecule-substrate van der Waals interactions

Quantum Frontiers (2022)

-

Identifying the convergent reaction path from predesigned assembled structures: Dissymmetrical dehalogenation of Br2Py on Ag(111)

Nano Research (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.