Abstract

Mn+1AXn phases are a large family of compounds that have been limited, so far, to carbides and nitrides. Here we report the prediction of a compound, Ti2InB2, a stable boron-based ternary phase in the Ti-In-B system, using a computational structure search strategy. This predicted Ti2InB2 compound is successfully synthesized using a solid-state reaction route and its space group is confirmed as P\(\bar 6\)m2 (No. 187), which is in fact a hexagonal subgroup of P63/mmc (No. 194), the symmetry group of conventional Mn+1AXn phases. Moreover, a strategy for the synthesis of MXenes from Mn+1AXn phases is applied, and a layered boride, TiB, is obtained by the removal of the indium layer through dealloying of the parent Ti2InB2 at high temperature under a high vacuum. We theoretically demonstrate that the TiB single layer exhibits superior potential as an anode material for Li/Na ion batteries than conventional carbide MXenes such as Ti3C2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mn+1AXn (MAX) phases are a class of unique materials that exhibit a combination of ceramic and metallic properties, and a mixture of covalent and metallic bonding1,2,3. Therefore, MAX phases possess the features of elastically stiff, strong, and heat-tolerant ceramics4, although their electrical and heat conductivities drop linearly with increasing temperature, as with a metal5. For the reported MAX phases, M represents an early transition metal, A is generally a metal element in group 13 or 14, while X is limited to C or N. Utilizing the significant difference in strength between the metallic M–A bonding and covalent M–X bonding, the A-layer can be selectively etched to form two-dimensional (2D) materials known as MXenes, which cannot be synthesized directly due to their thermodynamic metastability6,7,8,9. MAX phases and the derived MXenes have attracted extensive interest because of the abundance of their possible forms and structures, and their excellent chemical and mechanical stabilities, and thus, their broad applicability10,11,12,13,14,15,16. For instance, MXenes have shown great promise in applications involving electrochemical energy storage10,11,12,13,14 and catalysis15,16 because of their excellent conductivity, rich interlayer porosity and high surface functionalization. However, the question has been raised as to whether it is possible to synthesize new MAX phases and corresponding MXene materials without the limitation of using C and N as the X component.

Recently, with the successful deposition of atomic boron layers on various metal surfaces17,18, 2D boron and related borides have attracted broad attention for their potential applications in nanoelectronic devices19,20,21. Therefore, the exploration of boron (B)-containing MAX phases and their derived MXenes with exotic properties is of considerable interest in this research field. Ade and Hillebrecht recently proposed several ternary borides as analogs of MAX phases by introducing B as the X element22. However, each boride presented in their work was orthorhombic, which is totally different from the hexagonal structures (P63/mmc symmetry) of known MAX phases. In MAX phases, the M, A, and X atoms alternately stack along a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) manner and respectively form equilateral triangles of their own (the equilateral nature is determined by the symmetry of the hexagonal space group) parallel to each other. However, M and A atoms in the reported borides alternately stack along orthorhombic manner. And the M atoms, which are coordinated with boron, form non-equilateral trigonal prisms, with the side edge along x direction determining the lattice constant a, perpendicular to the A layers. Furthermore, the nearest neighbor boron atoms in reported borides form one-dimensional zig-zag chains perpendicular to the A layers also. Therefore, these B-containing ternary compounds were not categorized as new MAX phases, but were instead named MAB phases. However, Ade and Hillebrecht did indicate the possibility of extending the family of MAX phases to B-containing compounds. However, it is difficult to explore ternary compounds using conventional techniques because the number of candidates is too large (about 100,000 compounds), even without considering the exponentially increasing number of reactions involved. Therefore, a feasible strategy to simplify the search for ternary compounds based on the available domain knowledge is in high demand.

Recent investigations20,21 have revealed that an abundance of stable or metastable 2D structures can be formed using Ti and B. Our preliminary study and ref. 21 both suggested that TiB and Ti3B4 can exist in the form of layered structures in which TiB (space group Cmcm) or Ti3B4 (space group Immm) layers are connected by Ti-Ti metallic bonds (See Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The predicted Ti3B4 shows the same structure as that reported in the previous experiments23. However, the reported TiB compound in experiment24 possesses the space group of Pnma, indicating that a direct formation of layered TiB (Cmcm) is prohibited. Therefore, a possible strategy could begin from available layered TiB and Ti3B4 and involve inserting A elements into the interlayer Ti-Ti bonds to synthesize B-containing MAX phases, with subsequent etching of A to obtain the related MXenes. Although TiB and Ti3B4 are metastable compounds, the synthesis of a TixAyBz could be possible if the reaction enthalpy is negative with respect to TixBz (TiB2, TiB and Ti3B4), bulk A and other competitive phases.

In the present work, we examine the possibility of forming boron-containing MAX phases by employing a computation-based strategy. The current strategy involves greatly improving the computation efficiency to identify Ti2InB2 and Ti2SnB2 as theoretically stable compounds at ambient pressure and a high pressure of 10 GPa, respectively. Based on theoretical predictions, Ti2InB2 was successfully synthesized through a solid-state reaction, and subsequently a layered TiB compound was obtained by the removal of indium through a high-temperature dealloying process. The obtained compounds were evaluated experimentally and were confirmed to be consistent with the predictions. The layered TiB was predicted to be a promising anode material for Li/Na ion batteries according to density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Pristine TiB monolayers possess a much higher ion (Li or Na) storage capacity than Ti3C2, a representative MXene, and exhibit a very low energy barrier for the diffusion of Li and Na ions.

Results

Stability and structures of predicted borides

Figure 1 shows the thermodynamic stability of possible TixAyBz compounds estimated through reactions of TixBz with A rather than using Ti, B, and A. In the present material design loop, this step was realized by conducting binary variable-composition searches as implemented in the USPEX code25,26,27,28 using TixBz and bulk A as ending compounds. A pre-investigation to identify the structure of TixBz was performed by employing a binary structure search in the Ti-B system (Supplementary Fig. 1). For the given types of TixBz and elemental A, each possible combination of TixBz and A was considered in the preliminary structure search, limited only by the total number of atoms per unit cell. The elements Al, Ga, In, Tl, Si, Ge, Sn, Pb, and Cd were considered as A candidates in the structure search. When one ternary compound, TixAyBz, was found to be thermodynamically stable with respect to the end compositions of TixBz and A in the binary variable-composition search, a ternary variable-composition search was started for this Ti-A-B system to estimate the global stability of the predicted TixAyBz structure. Otherwise, the search procedure was initialized again by the selection of different pairs of TixBz and A elements.

Employing the strategy shown in Fig. 1 resulted in the prediction of a series of ternary compounds with the formulas Ti2AB2 and Ti3AB4 in the preliminary structure search (Fig. 2a). The ternary compounds Ti2AlB2, Ti3AlB4, Ti2GaB2, Ti3GaB4, Ti2InB2, Ti3InB4, Ti2SiB2, Ti3SiB4, Ti2GeB2, Ti3GeB4, Ti2SnB2, and Ti3SnB4 (Fig. 2a) were thermodynamically stable with respect to bulk A and TiB or Ti3B4. However, further Ti-A-B ternary variable-composition searches confirmed that only Ti2InB2 is thermodynamically more stable than competing Ti-B, Ti-In and In-B binary phases in the Ti-In-B ternary system at ambient pressure, while Ti2SnB2 is stable at a high pressure of 10 GPa. Other ternary candidates suggested by the binary variable-composition search were found to fall slightly short of thermodynamic stability and could not be synthesized under pressures lower than 10 GPa.

Results of theoretical structure search. a Summary of structure search results using binary and ternary variable-composition methods, where the distances for metastable phases to the convex hull are labelled in the unit of eV per formula. b Crystal structure. c Calculated electronic structure for stable boron-containing ternary phase Ti2InB2. The projected density of states (DOS), projected band structure and partial charge map on the (110) plane (−0.5 eV < E − Ef < 0.5 eV) for Ti2InB2 are shown in the left, center, and right panels, respectively

The optimized structure of Ti2InB2 with high-precision settings is shown in Fig. 2b. The detailed structures of Ti2InB2 and Ti2SnB2 are shown in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The predicted Ti2InB2 and Ti2SnB2 compounds possess typical characteristics of known MAX phases: a layered hexagonal structure (space group P\(\bar 6\)m2 (No. 187), see details in Supplementary Table 1), two M (Ti) layers, and one A (In) layer close packed along an HCP A-B-A sequence. Because the B/Ti ratio (1.0) in Ti2InB2 and Ti2SnB2 is higher than those of X/M ratios (1/2, 2/3 or 3/4) in conventional MAX phases, boron atoms occupy the X sites between M layers and form a graphene-like layer (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3) instead of a plane of equilateral triangles. The number of X (B) atoms per layer in Ti2InB2 or Ti2SnB2 is two times that for C- or N-containing MAX phases, which implies the existence of B–B covalent bonds that could provide a stiffer structure than conventional MAX phases. Theoretical calculations (Supplementary Table 2) show that Young’s modulus along the x- and y-directions, i.e., in the plane of the boron layer, is much larger than those for Ti2AlC or Ti3AlC2. Phonon stability for these two structures was also confirmed (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, we conclude that a 212 B-containing MAX phase can be formed instead of the traditional form of Mn+1AXn.

Electronic properties of predicted Ti2InB2

The electronic structures shown in Fig. 2c reveal that the predicted B-containing ternary compound possesses typical electronic features of MAX phases. Similar to those known MAX phases, this new B-containing MAX phase is revealed to be metallic. It can be seen that for Ti2InB2, the bonding (antibonding) states between the d orbitals of Ti atoms and the p orbitals of B or In atoms are located below (above) the Fermi level, whereas the non-bonding states of Ti are located between these bonding and antibonding states (near the Fermi level), and predominantly contribute to the metallic nature of Ti2InB2. This electronic structure is qualitatively similar to that for conventional MAX phases. Electron localization function (ELF) calculations showed that electron accumulation occurs between adjacent boron atoms, which reveals the 2c–2e (two center-two electron) nature of the B–B bonds (Supplementary Fig. 5) in Ti2InB2, similar to that in AlB2-type compounds, from which 2D hydrogen–boron sheets have been recently obtained via cation exchange29. However, this situation is different from that for conventional boron clusters derived from electron-deficient multi-center 2e bonding30, where filled octets cannot be achieved via 2c–2e bonding with only three valence electrons of boron. A Bader charge analysis showed that 0.87|e| was transferred from a Ti to a B atom, which resulted in the formation of 2c–2e bonds between B atoms. It is noteworthy to mention that the charge separation of Ti and B and B–B 2c–2e bonds in Ti2InB2 is close to the situation in TiB2 (Supplementary Fig. 5). The boron atoms in MAB phase Fe2AlB2 arrange along B–B zig-zag chains through the formation of B–B 2c–2e bonding (Supplementary Fig. 5). Similar electronic features can be found for another predicted structure, Ti2SnB2, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Possibility of indium removal from Ti2InB2

The interlayer A of MAX phases can be removed by etching with an appropriate acid, generally HF, which leads to the formation of a series of attractive materials, MXenes6,31. To evaluate the possibility of In removal from Ti2InB2, the separation energy for different interfaces along the [001] direction of Ti2InB2 was calculated (Supplementary Fig. 7). The separation energy for the Ti/In interface was found to be 3.27 J m−2, whereas that for the Ti/B interface was 8.36 J m−2. Therefore, the bonding between A (In) and M (Ti) is much weaker than that between M (Ti) and X (B), and is similar to that for the conventional MAX phases that can be engineered to 2D MXenes. For a clear comparison, the separation energy for the Ti/Al(001) and Ti/C(001) interfaces of Ti2AlC was calculated to be 5.66 and 11.90 J m−2, respectively. The Ti–In bonding in the newly predicted MAX phases is much weaker than that for Ti-Al bonding in Ti2AlC. The Ti/In-to-Ti/B separation energy ratio is 39%, which is also much smaller than the Ti/Al-to-Ti/C ratio of 48%. Consequently, the present calculations reveal the possibility of obtaining 2-D MXenes from Ti2InB2 by selective removal of indium through an appropriate approach. Phonon dispersion calculations (Supplementary Fig. 8) show that the hexagonal TiB structure is dynamically stable. However, our calculations show that the TiB orthorhombic structures are thermodynamically more stable (Supplementary Table 1). This suggests that the removal of indium under mild conditions (e.g., by chemical etching) may produce hexagonal TiB MXene, similar to conventional MXenes obtained by HF etching. Surface functional groups, like F, Cl, OH, and O, attributes significantly to the property modifications of conventional MXenes. We studied the electronic structures of TiBX (X = F, Cl, OH, and O) and found that a metal-to-semimetal transition appears in the functional 2D TiB (Supplementary Fig. 9). Moreover, the first-principles molecular dynamics (FPMD) simulations revealed that a phase transition from hexagonal TiB to orthorhombic TiB compounds may occur due to the strong thermal activation of lattice vibrations under high temperature conditions (Supplementary Fig. 10). The separation energy for the Ti/Ti interface of orthorhombic TiB was calculated to be 3.87 J m−2, which is comparable with that of Ti/In interface and indicates the laminated nature of TiB (Cmcm). The orthorhombic phase (Cmcm) that exhibits layered characteristics (Supplementary Fig. 11) was experimentally obtained under high-temperature conditions and will be shown in a later section.

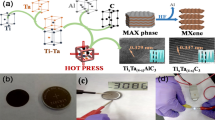

Experimental synthesis and characterization of Ti2InB2

Ti2InB2 was synthesized from a mixture of Ti, In and B powder through a solid-state reaction. The yield of Ti2InB2 was very sensitive to the experimental conditions, which were optimized after many tests (See Methods and Supplementary Figs. 12–17 and Table 3 for details). In the as-grown samples, there were many impurities, which were mainly TiB2 and Ti-In phases (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14). Adjustment of the starting compositional ratio of Ti, In and B enabled the final yield of Ti2InB2 to be maximized, while the amount of TiB2 was minimized (Supplementary Fig. 15). Ti–In phase impurities can be removed by chemical etching, whereas TiB2 is extremely stable (Supplementary Fig. 16). Therefore, after HCl acid etching, only Ti2InB2 (93.7 wt%) and a small amount of TiB2 (6.3 wt%) remained, as shown in Fig. 3a, and the obtained Ti2InB2 was crystallized in the predicted structure (space group P\(\bar 6\)m2). In a Rietveld analysis, the optimum fit was obtained by assuming a preferred orientation of (00l) for Ti2InB2, which suggested a material with a lamellar crystal structure. A laminar structure was clearly evident from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations, as shown in Fig. 3b. This is consistent with simulation results, in that the separation energy for the Ti/B interface is much larger than that for the Ti/In interface, which implies the possibility of obtaining 2D TiB sheets by the selective removal of In. The crystal structure was further confirmed by high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) (Fig. 3c). Observation along [001] direction provides an atomic image of Ti2InB2 in the x–y plane, with hexagonal patterns recording the projection of In and Ti atoms on the plane, which is consistent with the prediction (Fig. 3d). A fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the HAADF image also indicates that Ti2InB2 crystallizes in the hexagonal structure. A homogenous composition ratio of Ti:In:B = 1.95:1:2.08 was confirmed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (Supplementary Fig. 17). The physical properties of Ti2InB2 were also measured and the results are shown in Fig. 3e, f. The synthesized compound exhibits metallic behavior, which is consistent with the electronic structure calculations shown in Fig. 2c. Low temperature heat capacity (Cp) data (Fig. 3f) were fitted well using CP/T = γ + βT2, where γ is the coefficient of the temperature-linear Cp (γT) that describes the contribution from conduction carriers, and β is the coefficient of the Debye T3 term (βT3) associated with propagating acoustic phonons.

Experimental characterization of synthesized Ti2InB2 compound after HCl etching. a Powder XRD pattern with Rietveld analysis using GSAS package42. A small amount of TiB2 is evident. b SEM image of a particle showing a laminated structure. c HAADF-STEM image from the [001] direction. The inset shows the corresponding FFT pattern. d Crystal structure viewed from the z-direction (blue and purple spheres respectively indicate Ti and In atoms). Boron is not shown and the black lines represent the unit cells. e Electrical resistivity. f Heat capacity plotted as C/T vs. T2 at low temperature. The red line represents a linear fit to the data

Synthesis of layered TiB

Following the conventional etching method for producing MXenes, we first attempted to obtain 2D TiB MXene by immersion of Ti2InB2 powder in 50% HF for 12 h at room temperature. This resulted in total dissolution of the MAX phase, and even TiB2 was dissolved given sufficient time (Supplementary Fig. 18). Considering the intrinsically low melting point and high vapor pressure of In metal, a dealloying strategy was adopted to exfoliate the In layers. SiC was used as an oxygen scavenger to prevent the oxidation of compounds during the removal of In at high temperature (Supplementary Fig. 19). The hypothetical dealloying reaction process is described as:

Indium atoms were gradually extracted from Ti2InB2 and coated on the inner wall of a silica glass tube outside the furnace (Supplementary Fig. 20); In was almost completely removed at 1050 °C for 6 days under vacuum conditions (about 10−4 Pa). The weight loss for the sample was in good agreement with the mass of In contained in the Ti2InB2 compound. Figure 4a and Supplementary Fig. 21 show that the main dealloyed products are TiB MX compounds with an orthorhombic structure (Cmcm), together with TiB2 as an impurity phase in the prepared Ti2InB2.

Structure characterization of layered TiB. a XRD patterns for samples prepared by exposure of as-obtained Ti2InB2 powder to a vacuum (about 10−4 Pa) as a function of the temperature after 6 days. b Corresponding specific surface area change of samples in a. c Typical SEM image of the TiB phase obtained at 1050 °C for 6 days under vacuum (about 10−4 Pa); inset shows the atomic ratio for this sample. d HRTEM image of the TiB phase along the [01\(\bar 1\)] direction; inset shows the corresponding SAED pattern. e Enlarged HRTEM image from d showing the interlayer spacing for the (111) and (\(\bar 1\)11) planes. f Simulated crystal structure of the TiB phase with orthorhombic group (Cmcm) along the [01\(\bar 1\)] direction, where the blue spheres represent Ti atoms (other atoms are not shown)

The specific surface area increased from 2.45 to 6.16 m2 g−1 with increasing heating temperature, which also indicates that In species were gradually extracted from Ti2InB2 (Fig. 4b). Unfortunately, the lateral dimension of the parent Ti2InB2 was not kept after In was extracted, and the obtained TiB showed smaller particle size than the parent phase but still with layered structure (SEM images in Fig. 4c), which indicates that the original laminated structure was changed during the dealloying process at high temperatures. However, the obtained TiB can be considered to be a layered material where the layers are connected by Ti-Ti metallic bonds as we discussed above. An EDS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 22) indicated the presence of mainly Ti and B with a molar ratio of ~1:1 and with almost no In residue, which is consistent with the XRD results. A high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image was acquired along the [01\(\bar 1\)] direction of a TiB flake, which revealed bright atomic columns arranged in a square-like pattern, directly corresponding to the stacked Ti atoms (Fig. 4d). An enlarged HRTEM image (Fig. 4e) and the corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern (Fig. 4d inset) of exfoliated TiB flakes indicated an interplanar spacing of 2.162 Å for the (111) plane, which is consistent with the value of 2.127 Å obtained for the simulated structure (Fig. 4f). The (021) and (200) interplanar spacings were also measured to be 2.462 and 1.588 Å, respectively, which is in agreement with the simulation results (Supplementary Fig. 23). It should be noted that high temperature often induces recrystallization, and results in the formation of non-layered, bulk 3D cubic phase by selective loss of the A element from the MAX phase32,33,34,35. However, local displacements of Ti and B atoms caused by the high temperature led to the generation of an orthorhombic (Cmcm) phase with a layered structure during removal of the In species. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 24, we consider this orthorhombic (Cmcm) phase to have originated from a phase change of hexagonal (P\(\bar 6m\)2) with a similar layered structure, which can be confirmed by the simulation results of FPMD at 1273 K for 20 ps (Supplementary Fig. 10). After the FPMD simulation of 10 ps, the space group of TiB changed from P\(\bar 6\)m2 to Cmcm mainly due to interlayer slip. With further simulated heat treatment of 10 more picoseconds, the boron hexagonal rings became collapsed and boron chains instead appeared, which is the typical character of orthorhombic TiB (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 10). The real time scale of phase change from hexagonal TiB to orthorhombic phase (Cmcm) can be too long to be repeated by the FPMD simulations. However, the simulation results can be regarded as a theoretical support for the phase transition in the experiment. The phonon band structures of orthorhombic TiB structures with space groups of Pnma and Cmcm were calculated and shown in Supplementary Fig. 25. Both structures are found to be dynamically stable. Furthermore, the computed free energy (Supplementary Fig. 25) reveals that Pnma TiB is always more stable than the Cmcm phase in the full temperature range from 0 to 2000 K though the energy difference is very small (around ~0.005–0.01 kJ mol−1). This means that the chance for the transition from Cmcm to Pnma can be little due to the weak thermodynamic driving force, which explains the experimental result that the metastable Cmcm phase is the dominant product by heat treatment at 1050 °C.

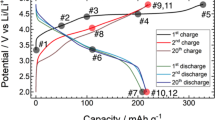

Prospect of layered TiB as anode material for ion batteries

Although impurities, such as TiB2 and 3D TiB (Pnma), were present, a new layered material, TiB (Cmcm), was successfully prepared by dealloying the new Ti2InB2 MAX phase. Although the layered TiB (Cmcm) is not comparable with 2D MXenes, the successful removal of In atoms suggests the possibility to obtain TiB MXene at mild conditions. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the potential applications of 2D TiB in advance. To evaluate the thermal stability of the 2D TiB structure at elevated temperatures for applications, we carried out FPMD simulations at 1273 and 1773 K for 10 ps (Supplementary Fig. 26). No sign of disruption or structural decomposition even in the 1773 K simulation. Therefore, it is expected that 2D TiB will be stable at temperatures as high as 1773 K for practical applications. The intercalation of Li+ or Na+ ions between MXene sheets makes them promising materials for Li- or Na-ion batteries. The charge/discharge reaction that should occur at the anode is: TiBLi(Na) ↔ TiB + Li+(Na+) + e−. To confirm the potential of layered TiB as an anode material for Li/Na ion batteries, adsorption of Li and Na atoms on the surface of a TiB monolayer was first studied using DFT calculations. These calculations revealed that each TiB primitive cell (Ti2B2) can accommodate up to two Li or two Na atoms (the adsorption of extra Li/Na atom would be thermodynamically unfavored.), which corresponds to a composition of TiBLi or TiBNa (Fig. 5a). Therefore, the theoretical specific capacity of TiB for Li or Na ions was calculated to be 480 mAh g−1, which is significantly higher than those of the conventional MXenes Ti3C2 (320 mAh/g for Li+)11, Ti2C (359 mAh g−1 for Na+)36 and even higher than that of the commercial anode material, graphite (372 mAh g−1 for Li+)11. The open circuit voltage (OCV) for the intercalation reactions involving Li+ and Na+ ions on a TiB surface was respectively estimated to be as low as 0.33 and 0.17 V, respectively, which are both much smaller than that for Ti3C2 (0.62 V for Li+) and comparable with that for graphite (about 0.2 V for Li+) and the hypothetical TiC3 (0.18 V for Na+)11,36. The calculated ELF across the absorbed Li/Na atoms and TiB monolayer show that the electron cloud spread out in the metal layers can screen the repulsion between the positive metal ions (Fig. 5a). A Bader charge analysis revealed that the charge transfer from absorbed Li atoms to the TiB monolayer was 0.80 |e|/Li, while one Na atom lost 0.48 |e| upon adsorption. Therefore, Li/Na atoms can be stabilized by the coulombic attraction between negatively charged B and positively charged Li/Na atoms.

Adsorption and diffusion behavior of Li and Na on 2D TiB (Cmcm). a ELF maps of a pristine TiB monolayer with one layer of Li atoms and one layer of Na atoms. b Considered diffusion paths for Li and Na on the TiB monolayer. c Calculated diffusion energy barriers along the paths in b. The purple and yellow spheres represent Li and Na atoms, respectively

The diffusion energy barrier for Li or Na on the TiB surface is critical for determining the charge−discharge rate in Li/Na ion batteries. The diffusion energy barrier along three different pathways (Fig. 5b) between the most stable nearest-neighboring adsorption sites of Li and Na on a 3 × 3 TiB supercell was calculated using the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method37. Figure 5b, c show that Li ions move along Path 1 and 2 with lower energy barriers of 0.11 and 0.16 eV, while Path 3 has the highest energy barrier of 0.22 eV. Similarly, for Na diffusion on the TiB surface, the energy barriers along Paths 1, 2, and 3 are respectively 0.08, 0.11, and 0.17 eV. Therefore, the new TiB monolayer should have a high charge-discharge rate due to these computed low energy barriers for Li and Na diffusion, which are very competitive with those for conventional MXenes (e.g. 0.18 eV for Li diffusion on Ti3C2), graphite (0.30 eV for Li diffusion), anatase TiO2 (0.35–0.65 eV for Li diffusion) and the predicted TiC3 (0.18 eV for Na diffusion)11,36. We noted that the diffusion activation energy for Li+ and Na+ ions on oxidized TiB surface gets increased (0.31~0.68 eV for Li+ and 0.22~0.50 eV for Na+) but is still competitive to the reported conventional materials (Supplementary Fig. 27). Considering the high specific capacity, low OCV and low energy barriers for Li+ and Na+ ions, the 2D- TiB (Cmcm) could be a promising alternative material to the commercial graphite anode in Li/Na ion batteries. Moreover, the diffusion of Li+/Na+ ions on hexagonal TiB surface was investigated (Supplementary Fig. 27), because the present research indicates the possibility to obtain TiB MXene at mild conditions. It shows that the diffusion energy barriers of Li+/Na+ ions on clean hexagonal TiB surface can be as low as around 0.02 eV. On the oxidized surfaces, the calculated energy barriers for Li+ and Na+ are, respectively, 0.23 and 0.19 eV.

Discussion

A progressive calculation-based approach was employed to predict and synthesize the boron-containing MAX phase Ti2InB2. Application of the proposed approach effectively screens out those material systems with a low possibility to produce new MAX phases and involves a much lower computational cost than direct trial and error or high-throughput calculations for ternary compound systems. The obtained Ti2InB2 compound possesses typical features of MAX phases, such as a layered hexagonal structure (symmetry P\(\bar 6m\)2) and a close-packed atom stacking sequence, the co-existence of weak Ti-In metallic and strong Ti-B covalent bonding along the [001] direction, metallic electrical resistivity and ceramic-like low heat capacity. With solid evidence from theoretical calculations and experimental validation, we have provided a clear example to extend the MAX phase family to boron-containing systems. Moreover, DFT calculations revealed that the separation energy for the Ti/In metallic interface is much smaller than that for the Ti/B covalent interface, which indicates the possibility of In atom removal while maintaining the TiB layered structure. Following this theoretical prediction, a layered TiB structure (Cmcm) was obtained by dealloying the Ti2InB2 MAX phase under vacuum conditions. The obtained TiB exhibited superior stability over the conventional MXenes and maintained its layered structure at high temperature. DFT calculations also predicted that the conductive TiB would be a promising anode material for Li/Na ion batteries with respect to a low OCV, a low Li/Na ion diffusion barrier, and a high theoretical Li/Na ion capacity. The present research will extend the fascinating class of MAX phases and MXenes.

Methods

High-throughput structure search

Structure searches were conducted using a combination of Universal Structure Predictor: Evolutionary Xtallography (USPEX)25,26,27,28 and the Vienna Ab initio simulation package (VASP)38,39. This approach was used to identify the structure with the lowest free energy for a given composition or in a composition range under given external conditions (0 K and 1 atm). Three types of structure searches were performed: fixed, binary variable composition, and ternary variable. For a fixed composition structure search, the calculation scheme comprised two steps: global optimization and local optimization. Structure initiation and variation were performed using USPEX in the global optimization step. For a variable composition structure search, two or three elements/compounds were adopted as reference components in a search of the target system. All possible combinations of the reference components were considered in the USPEX structure search, limited only by the number of atoms number per unit cell.

Density functional theory calculations

In the evolutionary structure search, thousands of structures were relaxed using DFT calculations. Therefore, sufficiently good settings were used to reduce the calculation cost: the energy cutoff for the plane-wave basis set expansion was set at 400 eV, and the Monkhorst–Pack40 k-point mesh solution in reciprocal space was 2π × 0.06 Å−1 for all structures. For structure refinement, the cutoff energy and k-point were, respectively, improved to 600 eV and 2π × 0.04 Å−1 to optimize the most stable structures obtained in the evolutionary structure searches. The atomic positions and unit cell volumes were fully relaxed until the total energy converged within 0.001 eV. These calculation settings were also adopted for the electronic structure calculations. Specifically, a denser k-mesh of 2π × 0.02 Å−1 was used for the density of states (DOS) for the predicted structures. Phonon dispersion calculations were performed to confirm the dynamic stability of all thermodynamically stable structures using VASP38,39 and Phonopy41. We performed first-principles molecular dynamics (FPMD) calculations using the VASP38,39 to simulate the transition from hexagonal TiB to orthorhombic phase and confirmed the thermal stability of 2D-TiB at elevated temperature. The FPMD simulations were performed with an NVT ensemble (keeping the number of atoms N, volume V and temperature T constant) with a Nosé thermostat. The time step of 2.0 fs used for each simulation. To compare their thermodynamic stabilities of different phases of TiB at different temperature, their Helmholtz free energies were calculated by following equation:

The total energy Etot was calculated by VASP38,39, the entropy S(T) was obtained by VASP and Phonopy41 calculations.

Synthesis of predicted Ti2InB2

Ti2InB2 was synthesized from Ti (99.9%), In (99.99%), and B (99%) powder using a solid-state reaction route. The chemicals were purchased from Kojundo Chemical Laboratory Co., Ltd. Single-phase Ti2InB2 could not be directly obtained, because it competed with other stable phases (mainly TiB2 and Ti-In phases). Finally, the yield was maximized by varying many different experimental conditions: the optimized values were 1100 °C for 36 h without further annealing using a quartz tube sealed with Ar gas and Mo foil as the protector, and excess amounts of both Ti and In (>25%). The samples used for characterization and property measurements were prepared with increased amounts of Ti and In by 50%. More information regarding the optimization process of temperature, the type of crucible, the atmosphere, the annealing process and the initial composition ratio is provided in Supplementary Figs. 12–17 and Table 3. After the solid-state reaction, chemical etching was applied to remove the impurity phases. Around 2 g samples were immersed in diluted hydrochloric acid (2 mol L−1, 100 mL) at room temperature for 10 h. Ti–In phases (Ti3In, Ti3In4, Ti2.2In1.8) were gradually dissolved with the evolution of H2 bubbles, and the color of the solution became purple (TiCl3). TiB2 exhibited high stability against etching, and could not be removed (Supplementary Fig. 16). Nitric acid was also used for etching; however, TiOx was produced as a new impurity.

Synthesis of layered material TiB

The as-prepared Ti2InB2 powders were filled into a Mo tube (in-house built with Mo foil, Nilaco Corporation, >99.95%). Several SiC (Kanthal Corporation) ingots were placed separately. The molybdenum tube and SiC ingots were heated at 900–1050 °C (5 °C min−1) for 6 days in a dynamically evacuated quartz tube (about 10−4 Pa) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 20. This heating step was effective for improving the dealloying of Ti2InB2, and the yield of TiB gradually increased with increasing annealing temperature. Finally, the optimized condition for the dealloying reaction was determined to be 1050 °C for 6 days. The obtained product TiB was a puce color, different from the dark gray color of the parent Ti2InB2.

Characterization of Ti2InB2 and TiB

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed using an X-ray powder diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (Bruker, D8 Advance). The morphology of the sample was evaluated using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; JEOL, JSM-7600F) and the component elements were analyzed using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS; JEOL, JED-2300). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images were obtained using a JEOL JEM-ARM200F atomic resolution analytical electron microscope operated at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Resistivity and heat capacity were measured with a physical properties measurement system (PPMS, Quantum Design). The Brunauer−Emmett−Teller (BET) specific surface areas of the samples were determined from nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms measured at −196 °C using an automatic gas-adsorption instrument (BELSORP-mini II, MiccrotracBEL).

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information file, or are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Goto, T. & Hirai, T. Chemically vapor deposited Ti3SiC2. Mater. Res. Bull. 22, 1195–1201 (1987).

Jeitschko, W., Nowotny, H. & Benesovsky, F. Carbides of formula T2MC. J. Less. Common. Met. 7, 133–138 (1964).

Schuster, J. C., Nowotny, H. & Vaccaro, C. The ternary systems: Cr-Al-C, V-Al-C, and Ti-Al-C and the behavior of H-phases (M2AlC). J. Solid State Chem. 32, 213–219 (1980).

Gilbert, C. J. Fatigue-crack growth and fracture properties of coarse and finegrained Ti3SiC2. Scr. Mater. 238, 761–767 (2000).

Magnuson, M. Electronic structure and chemical bonding in Ti2AlC investigated by soft x-ray emission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 74, 195108 (2006).

Naguib, M. et al. Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv. Mater. 23, 4248–4253 (2011).

Anasori, B., Lukatskaya, M. R. & Gogotsi, Y. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16098 (2017).

Naguib, M., Mochalin, V. N., Barsoum, M. W. & Gogotsi, Y. 25th anniversary article: MXenes: a new family of two-dimensional materials. Adv. Mater. 26, 992–1005 (2014).

Naguib, M. et al. Two-dimensional transition metal carbides. ACS Nano 6, 1322 (2012).

Farle, A. Demonstrating the self-healing behaviour of some selected ceramics under combustion chamber conditions. Smart Mater. Struct. 25, 1 (2016).

Tang, Q., Zhou, Z. & Shen, P. Are MXenes promising anode materials for Li ion batteries? computational studies on electronic properties and Li storage capability of Ti3C2 and Ti3C2X2 (X = F, OH) monolayer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16909–16916 (2012).

Naguib, M. et al. New two-dimensional niobium and vanadium carbides as promising materials for Li-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 15966 (2013).

Lukatskaya, M. R. Cation intercalation and high volumetric capacitance of two-dimensional titanium carbide. Science 341, 1502–1505 (2013).

Ghidiu, M., Lukatskaya, M. R., Zhao, M., Gogotsi, Y. & Barsoum, M. W. Conductive two-dimensional titanium carbide ‘clay’ with high volumetric capacitance. Nature 516, 78–81 (2014).

Ling, C., Shi, L., Ouyang, Y., Chen, Q. & Wang, J. Transition metal‐promoted V2CO2 (MXenes): a new and highly active catalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Adv. Sci. 3, 1600180 (2016).

Gao, G., O’Mullane, A. P. & Du, A. 2D MXenes: a new family of promising catalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Catal. 7, 494–500 (2017).

Tai, G. et al. Synthesis of atomically thin boron films on copper foils. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 54, 15473–15477 (2015).

Mannix, A. J. et al. Synthesis of borophenes: anisotropic, two-dimensional boron polymorphs. Science 350, 1513–1516 (2015).

Feng, B. et al. Experimental realization of two-dimensional boron sheets. Nat. Chem. 8, 563–568 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. Semimetallic two-dimensional TiB12: improved stability and electronic properties tunable by biaxial strain. Chem. Mater. 29, 5922–5930 (2017).

Li, P., Zhou, R. & Zeng, X. Computational analysis of stable hard structures in the Ti–B system. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 15607–15617 (2015).

Ade, M. & Hillebrecht, H. Ternary borides Cr2AlB2, Cr3AlB4, and Cr4AlB6: the first members of the series (CrB2)nCrAl with n = 1, 2, 3 and a unifying concept for ternary borides as MAB-phases. Inorg. Chem. 54, 6122–6135 (2015).

Spear, K. E., McDowell, P. & McMahon, F. Experimental evidence for the existence of the Ti3B4 phase. J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 69, C-4-C-5 (1986).

Decker, B. F. & Kasper, J. S. The crystal structure of TiB. Acta Cryst. 7, 77 (1954).

Oganov, A. R. & Glass, C. W. Crystal structure prediction using ab initio evolutionary techniques: principles and applications. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 244704 (2006).

Lyakhov, A. O., Oganov, A. R., Stokes, H. T. & Zhu, Q. New developments in evolutionary structure prediction algorithm USPEX. Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 1172–1182 (2013).

Oganov, A. R., Lyakhov, A. O. & Valle, M. How evolutionary crystal structure prediction works—and why. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 227–237 (2011).

Zhu, Q., Li, L., Oganov, A. R. & Allen, P. B. Evolutionary method for predicting surface reconstructions with variable stoichiometry. Phys. Rev. B 87, 195317 (2013).

Nishino, H. et al. Formation and characterization of hydrogen boride sheets derived from MgB2 by cation exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13761 (2017).

Galeev, T. R. et al. Deciphering the mystery of hexagon holes in an all-boron graphene α-sheet. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 11575 (2011).

Alhabeb, M. et al. Selective etching of silicon from Ti3SiC2 (MAX) to obtain 2D titanium carbide (MXene). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 5444–5448 (2018).

Naguib, M. On the topotactic transformation of Ti2AlC into a Ti–C–O–F cubic phase by heating in molten lithium fluoride in air. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 94, 4556 (2011).

Barsoum, M. W. The topotactic transformation of Ti3SiC2 into a partially ordered cubic Ti (C0.67Si0.06) phase by the diffusion of Si into molten cryolite. J. Electrochem. Soc. 146, 3919 (1999).

El-Raghy, T., Barsoum, M. W. & Sika, M. Reaction of Al with Ti3SiC2 in the 800–1000 °C temperature range. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 298, 174 (2001).

Emmerlich, J. Thermal stability of Ti3SiC2 thin films. Acta Mater. 55, 1479 (2007).

Yu, T. et al. TiC3 monolayer with high specific capacity for sodium-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 5962–5968 (2018).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188 (1976).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Toby, B. H. EXPGUI, a graphical user interface for GSAS. J. Appl. Cryst. 34, 210–213 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan through the Element Strategy Initiative to Form Core Research Center. This work was supported in part by the ACCEL program sponsored by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST). This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51872242). T.-N.Y. was supported by a JSPS fellowship for International Research Fellows (No. P18361). H.H. was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) (No. 17H06153). We thank M. Ichihara and M. Sasase (Tokyo Institute of Technology) for technical support with the TEM measurements. J.Wu thanks Y. Muraba (Tokyo Institute of Technology) for his help on sample synthesis. All of the calculations were performed on the supercomputer at the National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS), Tsukuba, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H., J.W., and T.T. proposed the idea behind the research. H.H. supervised the research. J.W. conducted high-throughput structure prediction and density functional theory calculations. Y.G. performed the preliminary synthesis of Ti2InB2. J.Wu. and T.-N.Y. performed the synthesis and characterization of Ti2InB2 and TiB. N.M. performed FPMD simulations and free energy calculation for TiB. J.W., T.-N.Y., J.Wu., and H.H. co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information Nature Communications would like to thank Vladislav Blatov and other anonymous reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Ye, TN., Gong, Y. et al. Discovery of hexagonal ternary phase Ti2InB2 and its evolution to layered boride TiB. Nat Commun 10, 2284 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10297-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10297-8

This article is cited by

-

Finding stable multi-component materials by combining cluster expansion and crystal structure predictions

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Indium (In) whisker growth from MAB phase Ti2InB2

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2023)

-

The single-atom catalytic activity of the hydrogen evolution reaction of the experimentally synthesized boridene 2D material: a density functional theory study

Journal of Molecular Modeling (2023)

-

A Rising 2D Star: Novel MBenes with Excellent Performance in Energy Conversion and Storage

Nano-Micro Letters (2023)

-

Prediction of phonon-mediated superconductivity in new Ti-based M\(_2\)AX phases

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.