Abstract

Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) significantly affects the properties of upper mantle and plays a key role in deep carbon recycling. However, its phase relations above 3 GPa and 1000 K are controversial. Here we report a reversible temperature-induced aragonite-amorphization transition in CaCO3 at 3.9–7.5 GPa and temperature above 1000 K. Amorphous CaCO3 shares a similar structure as liquid CaCO3 but with much larger C-O and Ca-Ca bond lengths, indicating a lower density and a mechanism of lattice collapse for the temperature-induced amorphous phase. The less dense amorphous phase compared with the liquid provides an explanation for the observed CaCO3 melting curve overturn at about 6 GPa. Amorphous CaCO3 is stable at subduction zone conditions and could aid the recycling of carbon to the surface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large amounts of carbon could be introduced into the deep mantle in the form of carbonates (e.g. CaCO3, MgCO3, and CaMg(CO3)2) by subduction of oceanic crust, constituting an important part of the global carbon cycling. The subducted carbonates pose enormous impacts on the Earth’s mantle. Carbonates could drastically reduce melting temperature of peridotite and eclogite1,2,3 and are important metasomatic agents with a remarkable wetting capability to impregnate silicate minerals4,5,6. Carbonate melt is an ionic liquid with ultra-low viscosity7 and is considered responsible for the conductivity anomalies in the oceanic mantle3,8,9,10. In particular, CaCO3 acts as a carrier to transport carbon into deep Earth from surface and transfer it back via volcano eruption11,12. CaCO3, together with CaMg(CO3)2, is also a possible calcium source for the formation of perovskite-structured CaSiO3 observed in deep diamond inclusions, providing insights into the recycling of oceanic crust in the deep mantle13. Although CaCO3 was reported to react with enstatite at upper mantle conditions to form dolomite14, diamond inclusions and exhumed ancient subduction-zone rocks evidently show that CaCO3 can survive to depths of at least the topmost lower mantle12,15,16.

Extensive studies on phase transitions of CaCO3 at high pressure and temperature have been conducted17,18,19,20,21,22. Rhombohedral calcite (calcite-I) is stable at ambient conditions and transforms to a monoclinic (P21/c) structure at about 1.5 GPa upon room temperature compression. It further transforms to triclinic calcite-III at about 2 GPa23. Upon heating, calcite-III transforms to aragonite20,24. However, the phase diagram of CaCO3 above 3 GPa and 1000 K is still controversial. A disordered calcite crystal phase (resembling calcite-IV or -V) was reported according to energy-dispersive X-ray diffraction (EDXRD) patterns20, while Litasov et al.25 suggested that it might be a new phase. Both studies did not provide any detailed structure information of the high-PT phase. Coincidently, the P–T conditions of the unsolved phase are in accord with the dissolution conditions of CaCO3 from subducted slabs11. However, the large-scale dissolution of CaCO3 during subduction remains unclear11,12. Therefore, exploring properties of the unsolved phase is essential to unveil this mechanism.

This study aims to clarify the nature of the transition from aragonite to the disordered crystal phase or new phase mentioned in Suito et al.20 and Litasov et al.25, respectively, and provide its structure information by in situ measurements up to 7.5 GPa and 1723 K using Paris–Edinburgh press techniques coupled with EDXRD. We report a reversible temperature-induced amorphization in aragonite. The structure measurements of amorphous CaCO3 indicate that the amorphous phase is one of the lightest materials in subducting slabs. Correlations between properties of the amorphous phase and the mechanism of large-scale CaCO3 dissolution in subduction zone are subsequently presented.

Results

Phase transitions in CaCO3

Upon compression of CaCO3 in a standard assembly cell for large-volume Paris–Edinburgh press (Fig. 1) at room temperature, we observed the transition from the rhombohedral calcite (calcite-I) to the monoclinic phase (calcite-II) between 1.4 and 1.9 GPa. The calcite-III phase appeared at 2.5 GPa (Fig. 2). The observed transitions are consistent with prior determinations of the phase boundaries17,18,20. Upon heating at 4.8 GPa, we confirmed the transition to aragonite at 473 K, whose XRD pattern can be indexed with an orthorhombic structure (Fig. 3). The transition temperature is in a good agreement with previous observations20,24.

The cell assembly for Paris–Edinburgh press used in phase and structure measurements of CaCO3. The CaCO3 sample is loaded in a graphite capsule which is isolated from a graphite heater by a BN pressure medium. The graphite heater is connected by Mo foils and Ta rods which serve as electrodes. MgO serves as both pressure calibrate and pressure medium

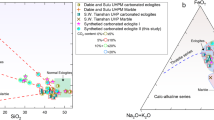

Phase diagram of CaCO3 at high pressure and high temperature. Arag. and DP represent aragonite and disorder phase, respectively. The black diamond and colored symbols show current data. The phase boundaries of calcite-I, calcite-III, calcite-II, and aragonite are drawn according to Suito et al.20. Other symbols and curves are from Irving and Wyllie57, Suito et al.20, Litasov et al.25, and Li et al.37

Energy-dispersive X-ray diffraction patterns of CaCO3 at high pressure and high temperature. The data were collected at a fixed 2θ of 15° and the energy (E) in the x axis was transferred to d-value by the equation of \(Ed\;{\mathrm{sin}}\left( \theta \right) = 6.199\;{\mathrm{keV}} \cdot\)Å. The short red bars denote the peaks of aragonite

Upon further heating at 4.8 GPa, we observed the aragonite phase stable up to 1073 K (Fig. 3). During the heating cycle, the recorded diffraction peaks showed some variation in peak intensity due to aragonite grain growth. At 1273 K, the majority of sharp peaks disappeared, and two broad bands emerged at d-spacing values of ~1.0 and ~1.3 Å. At higher temperature, only three broad peaks were observed up to 1673 K (Fig. 3). The broad peaks over this temperature range cannot be caused by melting because the temperatures are too low to initiate melting. We also confirmed melting that occurred at temperatures >1873 K by monitoring the movement of Pt spheres in the molten sample. Below the melting temperature, no movement of Pt spheres was observed (Fig. 4). It had been reported that the incorporation of water could significantly reduce the melting temperature of CaCO3 to less than 1127 K26,27. However, water (or water source, e.g., Ca(OH)2) should be sealed in Pt (or Au) capsule in large-volume press experiments in order to maintain the equilibrium reaction. We ran the experiments with pre-dried sample in open capsules and the melting of CaCO3 at relatively low temperature caused by hydration can be ruled out. Furthermore, our experiments with Pt spheres would not support CaCO3 melting at relatively low temperature because the viscosity of the melted CaCO3 is too small to hold the Pt sphere28 and Pt sphere is expected to drop. On the contrary, we observed the movement of the Pt sphere only when temperature reaches melting >1873 K. The likely explanation for the observed diffraction features is due to a transition to an amorphous phase. Amorphous CaCO3 could be further confirmed by multiangle EDXRD at 2θ = 3°, 4°, 5°, 7.4°, 9°, 12°, 16°, and 22° (Fig. 5a). No crystal peak of the sample was observed at 5.2 GPa and 1773 K in all the EDXRDs. On the other hand, the intensity of the broad peaks is large enough to exclude the possibility of background. More importantly, the broad peaks shift to lower energy when the diffraction angle increases. All the features conclusively verify that CaCO3 becomes an amorphous phase, ruling out the causes by melting, significant grain growth, or single crystal. We subsequently obtained EDXRD patterns during the cooling cycle. The three broad peaks persist to temperatures as low as 1173 K. When the temperature decreased to 1073 K, the sample immediately transformed back to aragonite characterized by its sharp diffraction peaks (Fig. 3). We also observed similar change of the patterns during the heating and cooling cycles in different experiments. These results indicate that the transition between aragonite and the amorphous phase is reversible.

Monitoring melting of CaCO3 by movement of Pt spheres in a heating cycle. The two red dash lines denote the interface between sample and graphite capsule. Three Pt balls were loaded in the sample. Two balls were packed near the graphite capsule edge and were stuck. The third Pt ball fell at 1873 K, which meant the melting temperature of CaCO3 was 1873 K at 5.1 GPa

Multi-angle energy-dispersive X-ray diffractions of CaCO3. a Amorphous CaCO3 at 5.2 GPa and 1773 K; b Liquid CaCO3 at 5.5 GPa and 1923 K. The liquid state was determined by the falling of Pt sphere. Two sharp peaks at 61.114 keV (2θ = 12°) and 96.640 keV (2θ = 3°) with d = 0.970(1) Å and d = 2.450(1) Å in a are from MgO. The sharp peak at 38.279 keV (2θ = 4°) with d = 4.640 (1) Å in b may come from other assembly materials

A disordered phase of CaCO3 at 6.16 GPa and 1473 K was reported by Suito et al.20. The disordered phase resembles calcite-IV or calcite-V with space groups of \({\mathrm{R}}\bar 3c\) and \({\mathrm{R}}\bar 3m\), respectively29, based on 3 diffraction peaks (102), (104), and (110). The diffraction patterns we collected at temperatures >1473 K and 5 GPa are consistent with features of an amorphous phase, and they are distinctively different from those in Suito et al.20. We also observed some sharp peaks along with the emerging of broad peaks in the temperature range of 1073–1273 K. During ascending temperature, some sharp peaks occasionally persist to temperatures as high as 1673 K and randomly disappeared at a temperature between 1273 and 1673 K in different heating cycles (Fig. 2). Therefore, we cannot rule out the existence of a disordered phase before final amorphization. We note that a weak broad peak at ~56 keV (d = ~2.1 Å) could be observed at 1473 K in Fig. 4 of Suito et al.20. The weak feature could be due to relatively short collection time. The d-value of the weak peak is consistent with the third broad peak in Fig. 3, indicating that amorphous CaCO3 was also presented in the study of Suito et al.20. The other two broad peaks shown in Fig. 3 could not be identified in Suito et al.20, which might be covered by strong graphite peaks at 38 keV.

We conducted a total of seven independent experiments and repeated the experiments to cross the crystal–amorphous phase boundary and characterized this boundary by the diffraction data of the high-PT phase. As discussed above, there is some uncertainty regarding when the diffraction peaks of the crystalline phase completely disappear during the heating cycle. However, during descending of the temperature, we consistently observed amorphous CaCO3 without crystalline diffraction peaks until it transformed to aragonite at a definitive temperature. We determine the phase boundary in Fig. 2 via EDXRD data at descending temperature. The boundary determined in this study is about 200 ± 100 K lower than that reported by Suito et al.20 and Litasov et al.25. Our boundary may be considered as a low bound for the transition.

Structure information of the amorphous phase and liquid CaCO3

Broad diffraction peaks, observed at temperatures between 1473 and 1673 K (Fig. 3), are consistent with diffraction signal from an amorphous phase. In order to confirm the amorphization of CaCO3 at high temperature and to understand the differences between amorphous and liquid CaCO3, we conducted multiangle EDXRD measurements at diffraction angles of 3–22° up to 1923 K at 3.9–7.5 GPa. Figure 5 presents the typical multiangle EDXRDs of amorphous and liquid CaCO3. One or two broad peaks were observed in the multiangle EDXRD at each 2θ (Fig. 5). As the 2θ increases, the broad peaks shifted to lower energy and new broad peak may appear at higher energy. From the multiangle EDXRD, we can get the structure factor [S(Q)] and real-space pair distribution function [G(r)]28.

Figure 6a shows the representative structure factor [S(Q)] of amorphous and liquid CaCO3 up to a Q value of 10 Å−1. The S(Q) patterns for the amorphous solid phase (1573 and 1773 K) and liquid (1873 and 1923 K) share similar features. The first sharp diffraction peak (FSDP) in S(Q) reflects the intermediate range ordering in network forming liquid or glass30. The intensity of FSDP for amorphous CaCO3 is slightly smaller than that of liquid CaCO3. However, the amorphous phase has a broader FSDP, indicating different intermediate range orderings in amorphous and liquid CaCO3.

Structure information obtained from multi-angle energy-dispersive X-ray diffraction measurements on amorphous CaCO3 at 1573 and 1773 K and liquid CaCO3 at 1873 and 1923 K. a Derived structure factor S(Q) of amorphous CaCO3 is compared with that of liquid CaCO3. b The corresponding pair distribution function G(r) of amorphous and liquid CaCO3 shows bond length variations for C-O, C-Ca, and Ca-Ca bonds

Fourier transformation of S(Q) yielded the real-space pair distribution function, G(r) (Fig. 6b)31. The G(r) patterns of liquid CaCO3 are similar to those reported in previous studies7,32. The amorphous CaCO3 has a similar G(r) pattern to that of the liquid CaCO3. However, differences can be observed in the bond lengths of C-O, Ca-O, and Ca-Ca, represented by the first, second, and third peaks, respectively (Table 1). The bond lengths of amorphous and liquid CaCO3 were calculated from peaks in G(r) patterns using Gaussian fitting and those of aragonite were estimated according to its thermal equation of state and crystal structure25,33. The C-O bond length of the amorphous phase is almost same as aragonite, while it is much larger than that of the liquid phase. The Ca-O bond length of the amorphous phase is identical to those of liquid CaCO3 and aragonite. It is difficult to get the Ca-Ca bond length because of the asymmetry of the Ca-Ca peak. However, we can qualitatively compare the differences by the topmost position (TP) of asymmetric Ca-Ca peaks. The Ca-Ca TPs of liquid and aragonite are ~6.3% and ~7.9% smaller than that of the amorphous phase, respectively. These data indicate that the amorphous phase at 1573 and 1773 K has basically the same structure as liquid but with different C-O and Ca-Ca bond lengths.

Although it is difficult to obtain an accurate density from the diffraction data of liquid or amorphous phase alone, the measurements provide qualitative comparison of densities for different phases because the density is proportional to the FSDP position34. The center of the FSDP of amorphous CaCO3 is ~2.00 Å−1, while that of the liquid phase is ~2.15 Å−1. The former is about 7% smaller, which is significantly larger than the uncertainty (<1%)35 in determining the center of the FSDP. Our diffraction data indicate that the density of the amorphous CaCO3 is smaller than that of the liquid phase based on the extracted structure factor of the amorphous and liquid phases. This can be further confirmed by the comparisons of the bond lengths in Table 1. Zhang and Liu36 theoretically calculated the densities of aragonite and liquid CaCO3 and found that the latter is ~13% smaller. In Table 1, the Ca-Ca bond length of liquid CaCO3 is much larger than that of aragonite, while their Ca-O bond lengths are comparable. From the density comparison of liquid CaCO3 and aragonite, we can conclude that the Ca-Ca matrix determines the density, while Ca-O and C-O are the second factor to affect density. Therefore, amorphous CaCO3 is less dense than its liquid counterpart, because the Ca-Ca bond length of amorphous CaCO3 is larger. The Clapeyron relation \(\left( {\frac{{{\mathrm{d}}T}}{{{\mathrm{d}}P}} = \frac{{\Delta V}}{{\Delta S}}} \right)\) describes the relation between phase boundary slope \(\left( {\frac{{{\mathrm{d}}T}}{{{\mathrm{d}}P}}} \right)\) and volume change \(\left( {\Delta V} \right)\), where \(\Delta S\) is entropy change. Since amorphous CaCO3 is less dense than liquid CaCO3, \(\Delta V\) would be negative, leading \(\frac{{{\mathrm{d}}T}}{{{\mathrm{d}}P}}\) to a negative value. This inference is consistent with the observed melting curve overturn at about 6 GPa20,37.

Mechanism

Pressure-induced amorphization is fundamentally interesting in physics, chemistry, material, geoscience, and industrial applications38,39. On the other hand, temperature is mainly treated as a crystallization stabilizer. Only hexagonal ice, SiO2-stishovite, and zeolites were reported to transform to an amorphous phase upon heating40,41,42. The temperature-induced amorphization (TIA) in CaCO3 is more intriguing because (1) amorphous CaCO3 is a stable phase and does not recrystallize before melting; and (2) the aragonite–amorphous phase transition is reversible. We observed direct melting from the amorphous phase without recrystallization in CaCO3, which behaves totally different from the crystal–amorphous phase–recrystallization in the meta-stable stishovite at ambient pressure. We also noticed that the amorphous CaCO3 with a relatively larger volume (the sample size is) could be stabilized at high pressure and high temperature compared with the metastable small amorphous CaCO3 particle (~1 μm) intergrown with aragonite at ambient conditions43,44, indicating that amorphous CaCO3 would exist in volumetrically large size in subduction zone.

The reported mechanisms for TIA include chemical disorder, thermodynamic melting followed by immediate vitrification, and mechanical collapse42,45. Chemical disorder is considered in zeolite where Al substitutes Si in TO4 framework45, whereas it can be excluded in the case of amorphous CaCO3 because there is no another element to substitute carbon in the framework. Thermodynamic melting followed by immediate vitrification was favored in amorphization of hexagonal ice42,45. Taking into account the melting temperature determined by Suito et al.20 and Li et al.37, the observed amorphization of CaCO3 occurs at much too low temperature (~800 K lower than the melting temperature) to be explained by vitrification. Consequently, mechanical collapse is the most plausible mechanism for the TIA in CaCO3. The crystal structure might be destroyed by the high mobility of the Ca2+ cation and the CO32− anion in the amorphous phase. This is consistent with the moderate decrease of the measured resistance across the aragonite to amorphous phase transition below the melting temperature37. The increase of the Ca-Ca bond length of the amorphous phase compared to that of aragonite also supports the increased mobility of Ca2+ cation that could eventually lead to the destruction of the Ca2+ lattices to form the amorphous phase.

Discussion

The observed amorphization in CaCO3 occurs at a relatively low temperature, comparable to the conditions relevant to subduction zone environments. At depth of 30–50 km, calcite will transform to aragonite and further to amorphous phase around 70–120 km (Fig. 7). The bond length comparison and the negative slope of the melting curve support that amorphous CaCO3 is less dense than the liquid counterpart. Most recently, Hudspeth et al.32 obtained the densities of liquid CaCO3 based on structure measurements, which range from 2.4 to 2.6 g cm−3 in the pressure range of 4.7–8.7 GPa at ~2000 K. In contrast, the densities of aragonite are 2.9–3.1 g cm−3 at these P–T conditions according to Litasov et al.25. Liquid CaCO3 is ~16% lighter than aragonite. The density reduction of liquid CaCO3 compared with aragonite is also supported by first principle calculations. Zhang and Liu36 calculated the densities of aragonite and liquid CaCO3 and found the latter is ~13% smaller. Since the amorphous CaCO3 is less dense than the liquid CaCO3, it would be at least 16% smaller than that of aragonite. The density profile of aragonite25 is comparable to MgCO346, (Fe0.65Mg0.33Mn0.02)CO321, basalt melt47, and PREM48. Our results imply that the amorphous CaCO3 is one of the lightest materials in subduction zone assemblages.

Phases of CaCO3 at upper mantle conditions and the schematic for deep carbon recycle. The geotherms follow Gerya and Yuen58 and Penniston-Dorland et al.59. The blue dot and blue shaded area in subducting slabs represent the amorphous CaCO3 and concentration area of amorphous CaCO3, respectively. The blue shaded particles in mantle wedge are escaped amorphous CaCO3 through percolation. At the top of the asthenosphere in mantle wedge, the amorphous CaCO3 would transform back to aragonite

The phase boundary of aragonite and amorphous CaCO3 intersects the melting curve at ~13 GPa, which corresponds to a depth of 400 km. In the depth between 70 and 400 km of subducted slabs, the most plausible form of CaCO3 is amorphous phase according to the phase diagram in Fig. 2. The density difference between the amorphous CaCO3 and other subduction zone assemblages indicates that the amorphous CaCO3 would possess an ultra-high buoyancy. On the other hand, amorphous CaCO3 is a weak solid with shear modulus of 14 GPa at ambient conditions49, which is only ~17% of olivine50 and ~41% of aragonite51. The ultra-high buoyant and soft amorphous CaCO3 has important implications for carbon recycling in subduction zones. Indeed, the majority of CaCO3 would likely escape the down-going slabs and ascend to magmas in the overlying mantle through dissolution11, rather than subducting to the deep mantle (Fig. 7). Decarbonization in fluids from the shallow subducting slabs only accounts for a portion of CO2 released in volcanic gas emissions52,53,54. CaCO3 has been considered to fill the gap between the CO2 outputs via volcanism and inputs in subducting slabs12. However, the mechanism for a large-scale CaCO3 dissolution from the slab is unknown11. We propose a novel regime of carbon input where CaCO3 readily concentrates through percolation of the amorphous phase and migrates from the subducting slabs to the mantle wedge. The migration of CaCO3 in the mantle wedge could be complex depending on the thermal structure of the slab and mantle wedge. Because the mantle wedge is hotter than the subducted slabs, the percolated amorphous CaCO3 from the subducted slabs would be further stabilized and migrate faster when CaCO3 enters the mantle wedge (Fig. 7). On the other hand, the higher temperature in the mantle wedge would dilate the amorphous CaCO3, so as to increase its buoyancy. In the shallow part of the mantle wedge, the temperature decreases as depth becomes smaller. The buoyancy of the amorphous CaCO3 would be reduced and the migration of the amorphous CaCO3 would be slower. As the amorphous CaCO3 migrates to a depth where the temperature is lower than the phase boundary between aragonite and the amorphous phase, it would transform back to aragonite. Assimilation of the amorphous CaCO3 into arc magmas could serve as an important CO2 source for volcanic eruptions. Additionally, this mechanism may lead to the formation of calcite-rich carbonatites12,55.

Methods

Experimental set-up

The EDXRD measurements on CaCO3 at high pressure and temperature were conducted using a large-volume Paris–Edinburgh press at 16-BMB synchrotron beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Two cup-shaped tungsten carbide anvils were used to generate high pressures. The starting material, CaCO3 (purity 99.99%, Alfa Aesar company) dried for 24 h in an oven at 110 °C, was loaded into a graphite capsule (Fig. 1). A boron nitride sleeve was used to separate the graphite heater from the capsule. An MgO sleeve outside the graphite heater served as both pressure medium and pressure marker. Pressure was determined from the XRD data of MgO56 at a fixed angle (2θ) of 15° using a Ge solid-state detector. Temperature was determined according to the calibrated temperature–power relationship28. The pressure and temperature uncertainties are 0.3 GPa and 100 K, respectively. Pt spheres of 80–100 μm in diameter were loaded in the sample chamber to monitor the melting of sample.

Structure measurements

The structure measurements of the solid and liquid CaCO3 were carried out via multiangle EDXRD fixed at 2θs of 3°, 4°, 5°, 7.4°, 9°, 12°, 16°, and 22°. The collection time of EDXRD at each angle is 30 min. Structure factor [S(Q)] and real-space pair distribution function [G(r)] are obtained as follows,

where \(Q = \frac{{4\pi E}}{{12.3984}}{\mathrm{sin}}(\theta )\), \(I_{\mathrm{m}}\left( {2\theta ,E} \right)\) is the observed energy EDXRD spectrum at a given \(2\theta\), \(S^\prime \left( {2\theta } \right)\) is proportional to \({\mathrm{cos}}^2(2\theta )\), \(I_{\mathrm{P}}\left( E \right)\) is the primary white beam profile, \(A\left( E \right)\) is the X-ray attenuation, \(C\left( E \right)\) is any other energy-dependent term, \(I_{{\mathrm{inc}}}\left( {2\theta ,E} \right)\) is incoherent scattering from the sample, \(f^2\left( {2\theta ,E} \right)\) can be calculated according to parameters in International Tables for X-ray Crystallography (Ed. Ibers and Hamilton). The detailed data analysis method can be found in Kono et al.28.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Ghosh, S., Ohtani, E., Litasov, K. D. & Terasaki, H. Solidus of carbonated peridotite from 10 to 20 GPa and origin of magnesiocarbonatite melt in the Earth’s deep mantle. Chem. Geol. 262, 17–28 (2009).

Litasov, K. D. & Ohtani, E. Solidus and phase relations of carbonated peridotite in the system CaO–Al2O3–MgO–SiO2–Na2O–CO2 to the lower mantle depths. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 177, 46–58 (2009).

Kiseeva, E. S., Litasov, K. D., Yaxley, G. M., Ohtani, E. & Kamenetsky, V. S. Melting and phase relations of carbonated eclogite at 9–21 GPa and the petrogenesis of alkali-rich melts in the deep mantle. J. Petrol. 54, 1555–1583 (2013).

Minarik, W. G. & Watson, E. B. Interconnectivity of carbonate melt at low melt fraction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 133, 423–437 (1995).

Hammouda, T. & Laporte, D. Ultrafast mantle impregnation by carbonatite melts. Geology 28, 283–285 (2000).

Dasgupta, R., Hirschmann, M. M., McDonough, W. F., Spiegelman, M. & Withers, A. C. Trace element partitioning between garnet lherzolite and carbonatite at 6.6 and 8.6 GPa with applications to the geochemistry of the mantle and of mantle-derived melts. Chem. Geol. 262, 57–77 (2009).

Kono et al. Ultralow viscosity of carbonate melts at high pressures. Nat. Commun. 5, 5091 (2014).

Evans, R. L. et al. Geophysical evidence from the MELT area for compositional controls on oceanic plates. Nature 437, 249–252 (2005).

Baba, K., Chave, A. D., Evans, R. L., Hirth, G. & Mackie, R. L. Mantle dynamics beneath the East Pacific Rise at 17° S: insights from the mantle electromagnetic and tomography (MELT) experiment. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JB003598 (2006).

Gaillard, F., Malki, M., Iacono-Marziano, G., Pichavant, M. & Scaillet, B. Carbonatite melts and electrical conductivity in the asthenosphere. Science 322, 1363–1365 (2008).

Manning, C. E. Geochemistry: a piece of the deep carbon puzzle. Nat. Geosci. 7, 333–334 (2014).

Ague, J. J. & Nicolescu, S. Carbon dioxide released from subduction zones by fluid-mediated reactions. Nat. Geosci. 7, 355 (2014).

Nestola, F. et al. CaSiO3 perovskite in diamond indicates the recycling of oceanic crust into the lower mantle. Nature 555, 237 (2018).

Kushiro, I., Satake, H. & Akimoto, S. Carbonate-silicate reactions at high presures and possible presence of dolomite and magnesite in the upper mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 28, 116–120 (1975).

Kaminsky, F., Matzel, J., Jacobsen, B., Hutcheon, I. & Wirth, R. Isotopic fractionation of oxygen and carbon in decomposed lower-mantle inclusions in diamond. Mineral. Petrol. 110, 379–385 (2016).

Wirth, R., Kaminsky, F., Matsyuk, S. & Schreiber, A. Unusual micro-and nano-inclusions in diamonds from the Juina Area, Brazil. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 286, 292–303 (2009).

Bridgman, P. W. The high pressure behavior of miscellaneous minerals. Am. J. Sci. 237, 7–18 (1938).

Merrill, L. & Bassett, W. A. The crystal structure of CaCO3 (II), a high‐pressure metastable phase of calcium carbonate. Acta Cryst. B 31, 343–349 (1975).

Fiquet, G., Guyot, F. & Itie, J.-P. High-pressure X-ray diffraction study of carbonates; MgCO3, CaMg (CO3)2, and CaCO3. Am. Mineral. 79, 15–23 (1994).

Suito, K. et al. Phase relations of CaCO 3 at high pressure and high temperature. Am. Mineral. 86, 997–1002 (2001).

Liu, J. et al. High-pressure compressibility and vibrational properties of (Ca, Mn) CO3. Am. Mineral. 101, 2723–2730 (2016).

Ono, S., Kikegawa, T. & Ohishi, Y. High-pressure transition of CaCO3. Am. Mineral. 92, 1246–1249 (2007).

Pippinger, T. et al. Puzzling calcite-III dimorphism: crystallography, high-pressure behavior, and pathway of single-crystal transitions. Phys. Chem. Miner. 42, 29–43 (2015).

Hess, N. J., Ghose, S. & Exarhos, G. J. Raman spectroscopy at simultaneous high pressure and temperature: phase relations of CaCO3 and the lattice dynamics of the calcite CaCO3(II) phase transition. In Recent Trends in High Pressure Research; Proc. X IIIth AIRAPT International Conference on High Pressure Science and Technology (ed. Singh, A. K.) 236–241 (Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt, Ltd., New Delhi, 1991).

Litasov, K. D. et al. P-V-T equation of state of CaCO3 aragonite to 29 GPa and 1673 K: in situ X-ray diffraction study. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 265, 82–91 (2017).

Wyllie, P. & Boettcher, A. Liquidus phase relationships in the system CaO-CO2-H2O to 40 kilobars pressure with petrological applications. Am. J. Sci. 267, 489–508 (1969).

Foustoukos, D. I. & Mysen, B. O. The structure of water-saturated carbonate melts. Am. Mineral. 100, 35–46 (2015).

Kono, Y., Park, C., Kenney-Benson, C., Shen, G. & Wang, Y. Toward comprehensive studies of liquids at high pressures and high temperatures: combined structure, elastic wave velocity, and viscosity measurements in the Paris–Edinburgh cell. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 228, 269–280 (2014).

Ishizawa, N., Setoguchi, H. & Yanagisawa, K. Structural evolution of calcite at high temperatures: phase V unveiled. Sci. Rep. 3, 2832 (2013).

Elliott, S. Origin of the first sharp diffraction peak in the structure factor of covalent glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 711 (1991).

Kaplow, R., Strong, S. & Averbach, B. Radial density functions for liquid mercury and lead. Phys. Rev. 138, A1336 (1965).

Hudspeth, J., Sanloup, C. & Kono, Y. Properties of molten CaCO3 at high pressure. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 7, 17–21 (2018).

Negro, A. D. & Ungaretti, L. Refinement of crystal structure of aragonite. Am. Mineral. 56, 768–772 (1971).

Zeng, Q. et al. General 2.5 power law of metallic glasses. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 113, 1714–1718 (2016).

Shibazaki, Y. & Kono, Y. Effect of silicon, carbon, and sulfur on structure of liquid iron and implications for structure-property relations in liquid iron-light element alloys. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JB015456 (2018).

Zhang, Z. & Liu, Z. High pressure equation of state for molten CaCO3 from first principles simulations. Chin. J. Geochem. 34, 13–20 (2015).

Li, Z., Li, J., Lange, R., Liu, J. & Militzer, B. Determination of calcium carbonate and sodium carbonate melting curves up to Earth’s transition zone pressures with implications for the deep carbon cycle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 457, 395–402 (2017).

Deb, S. K., Somayazulu, M. W. M. & McMillan, P. F. Pressure-induced amorphization and an amorphous-amorphous transition in densified porous silicon. Nature 414, 528 (2001).

Wang, Y. et al. Reversible switching between pressure-induced amorphization and thermal-driven recrystallization in VO2(B) nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 7, 12214 (2016).

Grimsditch, M., Popova, S., Brazhkin, V. V. & Voloshin, R. N. Temperature-induced amorphization of SiO2 stishovite. Phys. Rev. B 50, 12984–12986 (1994).

Greaves, G. N. et al. The rheology of collapsing zeolites amorphized by temperature and pressure. Nat. Mater. 2, 622–629 (2003).

Handle, P. H. & Loerting, T. Temperature-induced amorphisation of hexagonal ice. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 5403–5412 (2015).

Michel, F. M. et al. Structural characteristics of synthetic amorphous calcium carbonate. Chem. Mater. 20, 4720–4728 (2008).

Walker, J. M., Marzec, B. & Nudelman, F. Solid-state transformation of amorphous calcium carbonate to aragonite captured by cryoTEM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 11740–11743 (2017).

Kim, H. N. & Lee, S. K. Temperature-induced amorphization of Na-zeolite A: a view from multi-nuclear high-resolution solid-state NMR. Am. Mineral. 99, 1996–2007 (2014).

Zhang, J., Martinez, I., Guyot, F., Gillet, P. & Saxena, S. X-ray diffraction study of magnesite at high pressure and high temperature. Phys. Chem. Miner. 24, 122–130 (1997).

Sakamaki, T. et al. Ponded melt at the boundary between the lithosphere and asthenosphere. Nat. Geosci. 6, 1041 (2013).

Dziewonski, A. M. & Anderson, D. L. Preliminary reference earth model. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 25, 297–356 (1981).

Faatz, M. et al. Mechanical strength of amorphous CaCO3 colloidal spheres. Langmuir 21, 6666–6668 (2005).

Mao, Z. et al. Elasticity of single-crystal olivine at high pressures and temperatures. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 426, 204–215 (2015).

Huang, D. et al. Elastic properties of CaCO3 high pressure phases from first principles. Chin. Phys. B 26, 089101 (2017).

Kerrick, D. & Connolly, J. Metamorphic devolatilization of subducted marine sediments and the transport of volatiles into the Earth’s mantle. Nature 411, 293 (2001).

Gorman, P. J., Kerrick, D. M. & Connolly, J. A. D. Modeling open system metamorphic decarbonation of subducting slabs. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7, 170–176 (2006).

Poli, S., Franzolin, E., Fumagalli, P. & Crottini, A. The transport of carbon and hydrogen in subducted oceanic crust: an experimental study to 5 GPa. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 278, 350–360 (2009).

Woolley, A. R. & Kjarsgaard, B. A. Carbonatite occurrences of the world: map and database. Geol. Surv. Can. 5796, 1–28 (2008).

Kono, Y., Irifune, T., Higo, Y., Inoue, T. & Barnhoorn, A. P-V-T relation of MgO derived by simultaneous elastic wave velocity and in situ X-ray measurements: a new pressure scale for the mantle transition region. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 183, 196–211 (2010).

Irving, A. J. & Wyllie, P. T. Subsolidus and melting relations for calcite, magnesite and joint CaCO3-MgCO3 to 36 kb. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 39, 36–53 (1975).

Gerya, T. V. & Yuen, D. A. Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities from hydration and melting propel ‘cold plumes’ at subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 212, 47–62 (2003).

Penniston-Dorland, S. C., Kohn, M. J. & Manning, C. E. The global range of subduction zone thermal structures from exhumed blueschists and eclogites: rocks are hotter than models. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 428, 243–254 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jung-Fu Lin, Dr. Qishi Zeng, and Dr. Howard Sheng for their suggestions in understanding the TIA in CaCO3. We also thank Dr. Martin Kunz and Dr. Amanda Lindoo for reviewing the manuscript. Special thanks to Dr. Huiyang Gou and Dr. Zhisheng Zhao for their contributions in analyzing the mechanism of TIA in CaCO3. This work was supported by NSAF (Grant No. U1530402) and NSFC (Grant No. 41174071). The experiments were performed at HPCAT (Sector 16), Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory. HPCAT operation is supported by DOE-NNSA under Award No. DE-NA0001974, with partial instrumentation funding from NSF. The Advanced Photon Source is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02–06CH11357. Y.K. acknowledges the support of DOE-BES/DMSE under Award DE-FG02–99ER45775. Y.F acknowledges the support of Carnegie Institution of Washington and NSF grant (EAR-1619868).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. and Y.F. proposed the project. M.H., Y.K. and Q.Z. conducted the experiments. Q.Z. analyzed the data and Y.K. checked the data analysis. M.H., R.T. and H.L. analyzed the mechanism of the temperature-induced amorphization. W.Y., B.C. and H.-k.M. proposed the structure measurements and discussed the mechanism. M.H., Y.F. and Y.K. wrote the manuscript. All the authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, M., Zhang, Q., Tao, R. et al. Temperature-induced amorphization in CaCO3 at high pressure and implications for recycled CaCO3 in subduction zones. Nat Commun 10, 1963 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09742-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09742-5

This article is cited by

-

Recycled carbonates elevate the electrical conductivity of deeply subducting eclogite in the Earth’s interior

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Sound absorption polyimide composite aerogels for ancient architectures’ protection

Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials (2023)

-

Crystal structure and high-pressure phase behavior of a CaCO3–SrCO3 solid solution

Physics and Chemistry of Minerals (2023)

-

Recycled calcium carbonate is an efficient oxidation agent under deep upper mantle conditions

Communications Earth & Environment (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.