Abstract

Since its inception more than 25 years ago, Piezoresponse Force Microscopy (PFM) has become one of the mainstream techniques in the field of nanoferroic materials. This review describes the evolution of PFM from an imaging technique to a set of advanced methods, which have played a critical role in launching new areas of ferroic research, such as multiferroic devices and domain wall nanoelectronics. The paper reviews the impact of advanced PFM modes concerning the discovery and scientific understanding of novel nanoferroic phenomena and discusses challenges associated with the correct interpretation of PFM data. In conclusion, it offers an outlook for future trends and developments in PFM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The invention of the atomic force microscope (AFM) in 1986 marked a dramatic shift in scientific research by providing a multifunctional toolbox to explore and manipulate functional properties of a wide range of materials at the nanometer scale. For ferroelectrics and other polar materials, the introduction of one of the voltage-modulated versions of AFM—piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM)—has produced a wealth of new opportunities. PFM enables non-destructive visualization and control of FE nanodomains, as well as direct measurements of the local physical characteristics of ferroelectrics, such as nucleation bias, piezoelectric coefficients, disorder potential, energy dissipation, and domain wall (DW) dynamics (see Box 1). With this, PFM has essentially driven the whole field into the realm of the nanoscale 1.

Since the publication of the first review book 2, the experimental and physical principles of PFM operation have become common knowledge. A number of papers and books provided a comprehensive description of its technical details and gave abundant examples of PFM imaging and modification capabilities 3,4,5. As the field matured, new advanced PFM modes were developed (Box 2). However, the wide application of PFM revealed a growing number of challenges and concerns related to the imaging mechanism, data interpretation, and quantification. While nanoscale domain imaging has been crucial for the initial advent of nanoferroelectric research, it became also clear that a more careful analysis of the PFM image formation mechanism was necessary, along with comprehensive information on the structure, physics, and chemistry of the materials under investigation, to distinguish real effects from artifacts.

This article, instead of describing the experimental issues of PFM and a variety of accumulated data, focuses on new science and discoveries enabled by PFM. After presenting a brief historical overview of the evolution of conventional PFM into a set of advanced modes, it describes the role of PFM in exploration of new emergent phenomena, including DW conductivity, magnetoelectric switching, voltage-free flexoelectric domain control, tunneling electroresistance, domain vertices, and polar vortices. Specific attention is paid to challenges in PFM application related to a variety of electromechanical coupling phenomena and the complex image formation mechanisms. Based on the recent advances and challenges in the field of nanoferroics and other functional materials, this review offers an outlook for future developments and trends in PFM.

A brief history of PFM

A key element of AFM that brought about the possibility of high-resolution characterization of materials is the highly localized interaction between the probing tip and the sample1,2. In the case of ferroelectrics, a wide range of polarization-dependent properties, such as elastic, structural, electrochemical, pyroelectric, and piezoelectric, makes them a perfect material system for testing various AFM-based methods sensitive to the electrostatic, mechanical, and/or electromechanical (EM) tip–sample interactions4. Application of PFM to ferroelectrics makes use of their piezoelectric activity and its linear coupling with polarization in the low-field range. The underlying physical basis of PFM is similar to the idea of piezoelectric polarization-sensing proposed by Kaufman in the late 1950s6. Owing to the converse piezoelectric effect, application of an a.c. electric field to a ferroelectric sample results in surface vibration. The polarization state can be determined by measuring the magnitude and phase of this piezoelectric vibration signal. Therefore, the term “piezoresponse” was initially coined for this AFM-based technique7 although, as it was shown later, the EM coupling mechanism detected by PFM can go well beyond the piezoelectric effect8. The first AFM imaging experiments based on the converse piezoelectric effect were performed by Guethner and Dransfeld in 1992; their paper on local poling of the ferroelectric polymer vinylidene-fluoride trifluoroethylene (PVDF-TrFE) can be considered as the birth of PFM9. However, even before this seminal paper, Dransfeld’s group had used scanning near-field acoustic microscopy to detect different piezoactivity of the poled and non-poled regions of PVDF-TrFE films10. The lateral resolution of 1 µm, quite impressive for that time, was determined by the size of the probe apex. A year before, the same group used scanning tunneling microscope for nanoscale piezoelectric measurements11. However, this approach was too challenging to implement due to the high instability of the feedback signal. Thus, attempts to use the piezoelectric effect for local polarization detection were well under way from the early 1990s, building up on physical principles and technical approaches proposed earlier. However, it took several years for PFM to take off and start its way toward becoming a mainstream imaging and analytical tool for ferroelectrics. The PFM modes integrated into commercial AFM systems started to appear on the market in the late 1990s (Seiko Instruments, Park Scientific Instruments).

Historically, the invention of PFM is closely related to the advances in ferroelectricity, which, since its discovery in the 1920s, has passed through a number of well-marked “phases” when specific materials, techniques, or models were particularly popular12. Even before the development of scanning probe microscopy, it was predicted that the 1990s would be the age of “miniaturization,” when the scaling behavior of FEs would be at the forefront of scientific studies. PFM, along with advances in fabrication of functional ferroelectric nanostructures and theoretical modeling, turned this prediction into reality. Nanoscale visualization of the as-grown domain structure in Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 (PZT) thin films13 and the demonstration of polarization control in individual PZT nanocells14 marked the beginning of a widespread use of PFM and launched the era of nanoferroelectric research. Application of PFM to ferroelectric structures with sub-µm dimensions, such as ultrathin epitaxial films15, nanoscale capacitors16, and nanotubes17, opened a possibility for direct studies of the intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms of their scaling behavior. The fast progress in PFM applications was further boosted by the demonstration of local spectroscopy measurements—PFM hysteresis loops13,18, which allowed nanoscale testing of physical parameters, such as nucleation bias, imprint, piezo-coefficients, and disorder potential. This voltage-dependent PFM approach later evolved into switching spectroscopy PFM (Box 2)—an effective tool for two-dimensional (2D) nanoscale mapping of the local switching characteristics19. An important step forward in nanoferroelectric research was the visualization of domain structures through the top electrode20. This development allowed the direct observation of domain nucleation and DW dynamics at the sub-100-ns time scale in device-grade PZT capacitors using stroboscopic PFM (Box 2) and provided invaluable information on the scaling behavior of ferroelectric random access memory devices (FeRAM)21.

Simultaneous detection of electrically induced contraction/expansion and shear deformation of the sample—the approach later termed as vector PFM (Box 2)22—allowed delineation of the in-plane and out-of-plane polarization components and three-dimensional (3D) polarization reconstruction23. Expanding usage of PFM stimulated serious theoretical efforts to describe the image formation mechanism as well as tip-induced domain switching, and to understand the meaning of local PFM hysteresis loops 24. Detailed analysis of the sample response and cantilever motion revealed limitations of PFM as a quantitative technique, caused by the nonuniform distribution of the tip-generated electroelastic fields, lack of information on the tip geometry, and complex tip–sample contact mechanics, in addition to the non-trivial sample symmetry/orientation-dependence of the PFM signal25.

The mid-00s marked a growing use of PFM in combination with other microscopy techniques further expanding the frontiers of the nanoferroic field. High-resolution imaging of both antiferromagnetic and ferroelectric domains in multiferroic BiFeO3 by X-ray photoemission electron microscopy (PEEM) and PFM, respectively, led to the first demonstration of electrical control of antiferromagnetic domains in a single-phase multiferroic26. In one of the first examples of simultaneous use of PFM and conducting AFM (C-AFM), Yoshida et al. demonstrated polarization-modulated conduction in PZT thin films27. This approach has been utilized to its full extent during the experimental observations of the electroresistance effect in ferroelectric tunnel junctions28,29 and enhanced conductivity of ferroelectric DWs30. A breakthrough discovery of alternating net magnetic moments at ferroelectric DWs in multiferroic hexagonal manganites has been achieved by using PFM in conjunction with magnetic force microscopy (MFM)31.

Around the same time, the utility of PFM in testing the nanoscale EM behavior of a broader range of materials, such as piezoelectric semiconductors and biomaterials, was established. Intrinsic piezoelectricity of biopolymers enabled first nanoscale structural imaging of calcified and connective tissues as well as orientational imaging of protein molecules32. Similarly, the polar structure of III–V semiconductors allowed delineation of the inversion domains associated with different termination layers32. Extension of PFM usage to materials with weak EM properties necessitated enhancement of PFM sensitivity, which was addressed by the development of the resonant-enhanced mode of PFM by Rodriguez et al. in 2007 (Box 2)33 preceded by work of Harnagea et al.34.

PFM is still evolving: for example, high-speed and multi-dimensional data acquisition components have been recently added to its already wide portfolio of capabilities. Latest advances are related to the development of metrological PFM and band-excitation PFM (Box 2), which allow multi-frequency spectroscopic analysis of the dynamic processes in ferroelectrics.

Challenges of PFM

The conceptual simplicity of PFM and the ease, with which the PFM mode can be operated on modern AFMs, should not be mistaken for triviality of PFM data analysis and interpretation. AFM systems tend to turn more and more into “black boxes” that readily produce data with large throughput and high accuracy. On the one hand, the “black-box” design can be an issue for specialists because of reduced flexibility and rather limited options for the development of new experiments. On the other hand—and more problematically—new users are no longer required to have a thorough knowledge or understanding of the experimental details to record PFM data. As a consequence, the danger of misinterpretation and scientifically incorrect conclusions increases. In particular, it is important to remember that PFM is not a foolproof verification tool for ferroelectricity: PFM detects the electrically modulated mechanical strain—a property that is necessary but not sufficient for determining the ferroelectric behavior. The reason is that, in addition to the polarization-dependent piezoelectric deformation, there are several other mechanisms that can lead to a ferroelectric-like PFM response. These mechanisms are discussed below along with other challenges associated with successful experimental implementation and correct interpretation of PFM data.

Image formation

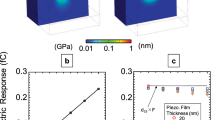

Independent of a specific PFM mode, image formation always follows the same basic principle. The response of the sample is probed by the tip and recorded with the help of lock-in technique, translating the tip-oscillation into a voltage. The output voltage is then used to generate 2D maps by scanning the tip line-by-line across the sample. PFM is thus by no means a direct measure of ferroelectricity or piezoelectric deformation. Understanding whether the detected signals correspond to the intrinsic ferroelectric properties (Fig. 1a) or potential artifacts is a major challenge.

Ferroelectric and non-ferroelectric contributions in PFM. a Owing to the linear coupling between piezoelectric activity and spontaneous polarization in the low-field range, ferroelectric domain imaging can be carried out by detecting the electrically induced surface displacement due to converse piezoelectric effect. b In addition to the mechanism mentioned in a, other mechanisms may contribute to the image formation in PFM in ambient conditions: electrochemical reactions facilitated by the water meniscus at the tip–sample junction, field-induced migration of anions/cations, surface charging, and carrier injection, as well as non-linear high-order strain effects. c Switching spectroscopy PFM on amorphous non-ferroelectric HfO2 films yields hysteretic behavior in the PFM phase and amplitude signals. (Reprinted with permission from ref. 42. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society). As both ferroelectric and non-ferroelectric materials can exhibit hysteretic behavior in switching spectroscopy PFM, the observation of such loops alone is insufficient to confirm the ferroelectric behavior. d Non-ferroelectric signals due to charge injection and electrostatic forces can mimic the ferroelectric behavior in PFM measurements of non-ferroelectric LaAlO3 films. This image demonstrates reversible and long-living PFM phase contrast, which arises after applying a ±5 V d.c. bias to the tip. The image size is 8 × 8 µm2. (Reprinted from ref. 35, with the permission of AIP Publishing). e Electrically switchable and stable PFM phase contrast in Pt/LaAlO3/SrRuO3 capacitors is attributed to electrically induced oxygen vacancy migration. (Reprinted with permission from ref. 81). f Redistribution and accumulation of oxygen vacancies either on the surface or at the interface can cause hysteretic field-dependent behavior of the PFM signal in LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterostructures. (Reprinted with permission from ref. 36. Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society). g, h Effect of environment in PFM manifests itself in creating different boundary conditions for domain writing and retention. PFM images of domains generated by voltage pulses under ambient conditions (g) and low humidity (h) reveal drastically different domain sizes and shapes (g, h are both reprinted from ref. 47, with the permission of AIP Publishing)

Origin of the electromechanical response

Understanding the mechanism behind the EM signal is a key issue for correct data interpretation. For example, charge injection and field-induced oxygen vacancy migration can result in a switchable internal electric field that biases the intrinsic electrostriction, producing a switchable PFM response35,36. Electrochemical strain due to ionic migration (Fig. 1b)37 is also relevant for mixed ionic–electronic conductors, biosystems, and polymers38. In principle, any material that exhibits a macroscopic D–E hysteresis loop can display hysteretic behavior in PFM39. Higher-order EM effects, such as flexoelectricity and switchable electrostriction, can also influence PFM image formation.

Verification of ferroelectricity

To evidence ferroelectricity, two effects have to be verified: the existence of domains with different orientation of polarization and hysteretic switching between the opposite domain states by electric fields. In PFM studies, it has become standard to present images taken before and after electrical poling to show the existence of switchable polarization domains, while PFM switching spectroscopy is commonly used to measure the corresponding hysteresis loop. However, in PFM, the non-piezoelectric effects mentioned above can convincingly mimic the ferroelectric behavior, producing long-lasting bistable states resembling written domains as well as hysteresis loops even in non-ferroelectric materials38. An increasing number of studies on non-ferroelectric materials, for example, TiO28 and LaAlO3/SrTiO336, clearly demonstrate that PFM measurements are insufficient to confirm the ferroelectric behavior (Fig. 1c–f). A striking illustration of PFM limitations in this matter is the ongoing controversy related to the mechanism of the polar behavior in organic perovskites40,41. A scanning probe microscopy-based approach has been recently proposed as a possible way to identify PFM artifacts and distinguish between the ferroelectric and non-ferroelectric PFM contributions42.

Calibration

While thorough signal calibration and careful separation of vertical (buckling/deflection) and horizontal (torsion) cantilever excitations allows 3D mapping of polarization, PFM cannot be considered as a quantitative tool for measuring the local piezoelectric coefficients. This limitation is due to a variety of reasons, i.e. non-uniform field distribution, contributions from the non-local electrostatic effects and multiple piezoelectric tensor elements to the EM displacement at a given point; mechanical constraints from the immediate (non-activated) surrounding; unknown contact resistance; etc43. In addition, system-inherent background contributions can have a significant impact on the PFM signal44. Quantitative PFM evaluation of the piezoconstants can be performed in a limited number of cases, for example, for d33 measurements in perovskite (001)-oriented capacitors with a small thickness/area aspect ratio22.

Environmental influence

In addition to the aforementioned intrinsic phenomena, the sample environment and surface effects can be decisive for the outcome of a PFM scan45. Under ambient conditions, a water meniscus at the tip–sample contact promotes surface charging and electrochemical reactions, affecting the domain switching and retention behavior (Fig. 1g, h)46,47.

Frictional forces

Electrically driven shear deformations, which correspond to the off-diagonal elements of the piezoelectric tensor, can be detected by monitoring the lateral PFM signal induced via tip–surface friction forces. However, surface contamination, topographical features, inhomogeneous electrical fields, complex frequency spectra, and mechanical clamping can significantly complicate the interpretation of lateral PFM data and cause imaging artefacts (Fig. 2). As these phenomena collectively affect the friction forces, the lateral PFM signal is a superposition of various contributions rather than a direct fingerprint of the FE domains. This makes lateral PFM essentially unsuitable for studying domains in the ferroelectric capacitors (Fig. 2a, b). Particular caution is required when using lateral PFM to analyze one-dimensional and 2D structures with constrained geometry, including nanoparticles, nanorods, and nanotubes (Fig. 2c, d).

PFM imaging artefacts. a, b Vertical (a) and lateral (b) PFM phase images of the 180° domains in a microscale (001)-oriented Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 capacitor. Lateral PFM contrast in b arises due to the changes of the top electrode morphology induced by the vertical expansion and contraction of the antiparallel 180° domains causing torsional movement of the cantilever, which changes its direction with the change in the surface slope sign. c, d Any asymmetry in the tip–sample system, for example, due to the surface slope, asymmetric tip apex, local variations in sample stoichiometry, or dielectric or elastic constants, may cause imaging artifacts especially pronounced in lateral PFM. c Atomic force microscopic topography and d lateral PFM images of the (001)-oriented Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 nanograins showing strong variations in the lateral electron microscopic response, which are not related to the in-plane polarization (c, d are adapted from ref. 99, with the permission of AIP Publishing)

Standards on PFM measurements

So far, attempts to develop a standardized PFM measuring protocol to gain consistent imaging and spectroscopic results were unsuccessful due to the complexity of the tip–sample interaction and variability of the imaging formation mechanisms as explained above. Although PFM measurements are carried out in a similar way irrespective of the tested materials, PFM practitioners use a broad range of imaging parameters even for the same type of samples: for example, the reported imaging frequencies are in the range from tens to hundreds of kHz. Furthermore, although the conductive cantilevers typically used for FE testing have elastic constants of several N/m, the modulating bias can vary from hundreds of mV up to several Volts. Coordinated efforts by the PFM users through the round-robin comparative spectroscopic testing of the standardized samples, such as periodically poled stoichiometric LiNbO3 crystals or (001)-oriented single-crystalline PbTiO3 or PZT thin film capacitors, using PFM in conjunction with laser Doppler vibrometry seem to be necessary to identify the data variations attributable to different experimental conditions and setups.

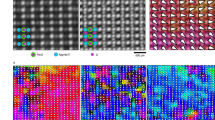

Discovery of new phenomena and testing polarization-enabled functionality

While at the earlier stages of its use PFM was essential for achieving a nanoscale insight into the ferroelectric switching phenomena, more recently, its combination with complementary nanoscale characterization tools allowed exploration of emerging phenomena in nanoferroic systems. This led to several key discoveries revealing unique electronic, magnetic, and transport properties of nanoferroics (Fig. 3).

PFM and discovery of novel phenomena. a Tunneling electroresistance effect verified by spatially resolved correlation between the onset of polarization reversal revealed by PFM and a resistive switching imaged by C-AFM. A change in PFM contrast correlates with the transition from low current (dark contrast) to high current (bright contrast). (Adapted with permission from ref. 29. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society). b Magnetic field control of ferroelectric domains in the multiferroic solid solution of lead zirconium titanate and lead iron tantalite (PZTFT): PFM images reveal a change in the ferroelectric domain structure, which depends on the orientation of the external magnetic field. (Adapted by permission from Springer Nature: ref. 62). c Emerging topologic domain structures: flux-closure domain formation in a microscale single-crystalline BaTiO3 lamella revealed by vector PFM. The image size is 2 × 2 µm2. (Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature: ref. 66). d Domain wall conductivity: the 6 × 6 µm2 lateral PFM image obtained on a ErMnO3 crystal with arrows indicating the in-plane polarization direction. The inset shows a C-AFM image acquired at the same location revealing different conductance for different types of domain walls. (Reprinted by permission from ref. 69). e Flexoelectric control of polarization: in ultrathin ferroelectric films, a strain gradient, generated by PFM tip pressure, can produce a flexoelectric field high enough to exceed the coercive field of the film resulting in purely mechanical switching of nanoscale domains. f Enhancement of photovoltaic current (C-AFM image in the upper panel) at domain walls (PFM phase image in the lower panel). The size of each panel is 3.0 × 1.5 µm2. (Adapted from ref. 86 under the terms of the CC-BY 4.0 license)

Tunneling electroresistance

One of the most exciting discoveries, involving the use of dual a.c. resonance tracking PFM, was the electroresistance effect in ferroelectric tunnel junctions (FTJs)29,48 followed by the demonstration of FE control of the carrier spin polarization in nanoscale capacitors49. PFM demonstrated that polar displacements could be stable and switchable in ultrathin films with a thickness down to only several unit cells and established a direct correlation between ferroelectric switching and the electroresistance effect (Fig. 3a). PFM detection of partial polarization switching associated with different tunneling-current levels led to the discovery of the memristive behavior in FTJs50,51 opening a possibility for the development of multilevel memories and solid-state ferroelectric-based synapses for neuromorphic computing52.

Multiferroics

Another field that has hugely benefited from PFM is multiferroics. A combination of PFM and complementary methods, such as photoemission electron microscopy (PEEM) and X-ray resonant magnetic scattering, enabled the discovery of a local coupling between FE and antiferromagnetic domains in BiFeO3 (BFO) thin films26 and the emergence of multiferroicity at the interface between ultrathin BaTiO3 films and magnetic layers53. In addition, multi-method approaches involving PFM were used to gain control of the exchange bias in BFO films54 and to switch local ferromagnetism by electric fields55. More recently, PFM and NV-center magnetometry have been combined to gain an insight into the coupling of the ferroelectric and cycloidal antiferromagnetic domains in BFO56. In multiferroic bulk systems, combinations of PFM and MFM31, magnetoelectric force microscopy57, transmission electron microscopy (TEM)58, optical microscopy59, as well as second harmonic generation60, were used to scrutinize the emergence and interplay of structural, electric and magnetic degrees of freedom. In particular, PFM allowed high-resolution imaging of the exotic ferroelectric domain pattern in multiferroic hexagonal manganites61. In multiferroic ceramics, PFM together with complementary scanning TEM measurements was used to demonstrate magnetic-field switching of ferroelectric domains at room temperature (Fig. 3b)62.

Topological states

This new, still nascent but rapidly growing field addresses vortices, skyrmions, flux closures, chiral, and other topologically protected states in polar materials. In 2004, unusual vortex states were predicted to occur in nanoscale ferroelectrics due to very high depolarization fields63. Just several years later, when advances in processing technologies facilitated the fabrication of such nanometer-scale structures64, vector PFM, as a uniquely suited characterization technique, revealed the predicted emergence of vortex domain states and flux closures (Fig. 3c)65,66. More recently, nanoscale bubble domains, which can be considered as a precursor of electrical skyrmions, have been resolved67.

Functional DWs

Another emerging field extensively relying on PFM focuses on functional DWs in ferroics68, which exhibit a range of unusual physical properties. The work of Seidel et al.30 stimulated a worldwide interest in DWs by showing that PFM-written DWs in otherwise insulating BFO thin films were electrically conducting. Anisotropic DW conductance was revealed in the improper ferroelectric ErMnO3 (Fig. 3d)69,70. Extended studies on other ferroelectrics showed that unusual DW transport was a rather generic property occurring in a wide range of systems. This includes classical (proper) FEs (PZT71, BaTiO372) as well as improper ferroelectrics RMnO3 (R = Y, In, Dy–Lu)69 (Ca,Sr)3Ti2O773, Cu3B7O13Cl74). The functional properties of DWs and the possibility to inject, erase, or dynamically dope them75 offer unique opportunities for building future agile nanoscale devices76. In the first proof-of-principle experiments, PFM helped to demonstrate specific DW-based functionality, using them as spatially moveable nanowires70, digital switches77, and nonvolatile memories78.

Flexoelectricity

Although demonstrated experimentally almost 50 years ago, flexoelectricity—a coupling between a polarization and a strain gradient—started to draw much attention only with the advent of nanotechnology because of larger gradients at the nanoscale79. In ultrathin films, a flexoelectric field due to a strain gradient, generated by PFM tip pressure, may even exceed the coercive field leading to purely mechanical switching of polarization (Fig. 3e)80. Nanoscale flexoelectricity has been used for tuning 2D electron gas81, mechanical control of resistive switching37, manipulation of oxygen vacancies82, and even for inducing photovoltaic (PV) effects in centro-symmetric materials83.

Photovoltaics

PVs currently experiences renewed interest, triggered by the discovery of abnormal PV effects in ferroelectric thin films84. In seminal experiments on BFO, vector PFM was used in combination with macroscopic current–voltage measurements to investigate the impact of the ferroelectric domain geometry on the PV properties84. Subsequent in-depth studies85 revealed that the emergent above band-gap voltages originate from the bulk PV effect. Furthermore, photocurrents were scrutinized in spatially resolved experiments to clarify the PV/photoconductive properties of the ferroelectric DWs (Fig. 3f)86. In the latest development, PFM allowed demonstration of a tip-enhanced PV effect and light-induced ferroelectric switching87.

Outlook and perspective

We are at an inflection point in PFM development and application. On the one hand, PFM has evolved from an imaging technique to a set of advanced methods, which became the prime tools for probing and controlling the static and dynamic properties of nanoscale ferroic structures and devices. On the other hand, a growing range of tested materials revealed PFM limitations: it is now clear that a careful analysis of the PFM image formation mechanism along with comprehensive information on structure, physics, and chemistry of materials obtained by complementary techniques is necessary to distinguish between science and artifacts. Some predictions for future directions and applications of PFM, made several years ago, have not materialized. For example, while PFM can be used as a valuable platform for conducting rigorous and replicable testing of new scientific ideas and device concepts, it is not likely to become part of an evaluation testbed for integrated memory devices or be exploited for bottom–up large-scale fabrication of electronic circuits.

Where will it go from here? Given that the most important breakthroughs in PFM application have been made in combination with other microscopic techniques, it is safe to predict that this trend will continue. It is envisioned that PFM will be extended to multiple stimuli (magnetic, optical, thermal) and combinations of those to induce mechanical strain response at a broad range of temporal scales to discover emerging phenomena and investigate novel functional properties in a variety of material systems. PFM analysis of the electronic processes in ferroics with respect to the field-induced changes in local structure and chemical composition will be greatly facilitated by acquisition of the spatially resolved chemical 2D and 3D maps by nano-Raman microscopy and time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectroscopy—approaches that have just started to gain momentum88. One of the main limitations of PFM will remain its relatively low time resolution. Short (~10 µm) cantilevers with high resonant frequencies (up to several MHz) facilitate video-rate PFM with an imaging speed of about 10 frames per second. This will allow investigation of domain structure evolution during thermally stimulated phase transitions and relaxation processes on a 100-ms time scale89. However, in application to the fast switching processes, the time resolution is unlikely to go below the current state-of-the-art nanosecond range of stroboscopic PFM being limited by the external circuit time constants. Extension of PFM spectroscopy into the MHz range will enable collection and multivariate analysis of large amounts of data allowing a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the voltage–time-dependent switching and energy dissipation processes. One of the possible hurdles in big-data analysis could be the streaming rate of the data.

Realization of DW-based nanotechnology requires application of PFM in combination with C-AFM, MFM, scanning impedance microscopy, and nano-Raman spectroscopy complemented by high-resolution electron microscopy studies. This comprehensive approach is desirable to get a better knowledge of the local electronic states, carrier density profile, mobility and conduction mechanisms, and their relation to the local atomic structure. First steps in this direction have already been made and include local Hall effect measurements90 and contact-free high-resolution conductance measurements91, as well as advanced nonlinear optical experiments92. Controlled generation and driving of DWs via electric and strain field gradients is a promising approach for the realization of DW-based devices and undoubtedly will be explored further.

As a technique, PFM presents a new paradigm in exploring and designing emergent electronic properties of advanced oxide, hybrid, and organic nanoferroic materials and nanostructures. State-of-the-art PFM methods, in conjunction with first-principle modeling and atomically controlled growth, will play an increasingly important role in investigating the fundamental issues related to the critical behavior and switching dynamics in ultrathin ferroelectric and multiferroic heterostructures. Furthermore, such methods will allow us to understand the interplay between the ferroelectric and ferromagnetic order parameters, the role of structural defects and interfacial properties in the electronic transport at the nanoscale and the scalability of heterostructures to micro-, meso-, and nano-dimensions.

References

Kalinin, S. V. & Gruverman, A. (eds) Scanning Probe Microscopy: Electrical and Electromechanical Phenomena at the Nanoscale (Springer, New York, 2006).

Alexe, M. & Gruverman, A. (eds) Ferroelectrics at Nanoscale: Scanning Probe Microscopy Approach (Springer, New York, 2004).

Kalinin, S. V., Morozovska, A. N., Chen, L. Q. & Rodriguez, B. J. Local polarization dynamics in ferroelectric materials. Rep. Prog. Phys. 73, 056502 (2010). Review article on imaging, manipulation and spectroscopy of ferroelectric switching by PFM with special emphasis on resolution limits.

Gruverman, A. & Kholkin, A. Nanoscale ferroelectrics: processing, characterization and future trends. Rep. Prog. Phys. 69, 2443–2474 (2006).

Soergel, E. Visualization of ferroelectric domains in bulk single crystals. Appl. Phys. B 81, 729–751 (2005).

Kaufman, A. B. Ferroelectric memories for security and identification purposes. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 16, 562–564 (1969). The concept of polarization reading via the converse piezoelectric effect.

Gruverman, A., Auciello, O. & Tokumoto, H. Scanning force microscopy for the study of domain structure in ferroelectric thin films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 14, 602–605 (1996).

Kim, Y. et al. Ionically-mediated electromechanical hysteresis in transition metal oxides. ACS Nano 6, 7026–7033 (2012).

Güthner, P. & Dransfeld, K. Local poling of ferroelectric polymers by scanning force microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 61, 1137–1139 (1992).

Güthner, P., Glatz-Reichenbach, J. & Dransfeld, K. Investigation of local piezoelectric properties of thin copolymer films. J. Appl. Phys. 69, 7895–7897 (1991).

Birk, H., Glatz-Reichenbach, J., Jie, L., Schreck, E. & Dransfeld, K. The local piezoelectric activity of thin polymer films observed by scanning tunneling microscopy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 9, 1162–1165 (1991).

Cross, L. E. & Newnham, R. E. High-Technology Ceramics (American Ceramic Society, Ohio, 1987).

Gruverman, A., Auciello, O. & Tokumoto, H. Nanoscale investigation of fatigue effects in Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 69, 3191–3193 (1996).

Alexe, M., Harnagea, C., Hesse, D. & Gosele, U. Patterning and switching of nanosize ferroelectric memory cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 1793–1795 (1999).

Tybell, T., Ahn, C. H. & Triscone, J.-M. Ferroelectricity in thin perovskite films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 856–858 (1999).

Ganpule, C. S. et al. Scaling of ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties in Pt/SrBi2Ta2O9/Pt thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 3874–3876 (1999).

Luo, Y. et al. Nanoshell tubes of ferroelectric lead zirconate titanate and barium titanate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 440–442 (2003).

Eng, L. M. Nanoscale domain engineering and characterization of ferroelectric domains. Nanotechnology 10, 405–411 (1999).

Jesse, S., Baddorf, A. P. & Kalinin, S. V. Switching spectroscopy piezoresponse force microscopy of ferroelectric materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 062908 (2006).

Hong, S. et al. High resolution study of domain nucleation and growth during polarization switching in Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 ferroelectric thin film capacitors. J. Appl. Phys. 86, 607–613 (1999).

Gruverman, A., Wu, D. & Scott, J. F. Piezoresponse force microscopy studies of switching behavior of ferroelectric capacitors on a 100-ns time scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 097601 (2008). First direct observation of domain nucleation and domain wall dynamics at the sub-100-ns time scale in micrometer-size device-grade PZT capacitors.

Kalinin, S. V. et al. Vector piezoresponse force microscopy. Microsc. Microanal. 12, 206–220 (2006).

Eng, L. M., Güntherodt, H.-J., Schneider, G. A., Köpke, U. & Muñoz Saldaña, J. Nanoscale reconstruction of surface crystallography from three-dimensional polarization distribution in ferroelectric barium–titanate ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 233–235 (1999).

Kalinin, S. V. et al. Imaging mechanism of piezoresponse force microscopy in capacitor structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 152906 (2008).

Harnagea, C., Pignolet, A., Alexe, M. & Hesse, D. Piezoresponse scanning force microscopy: what quantitative information can we really get out of piezoresponse measurements on ferroelectric thin films. Integr. Ferroelectr. 38, 23–29 (2001). Introduction of the method to relate the PFM amplitude to the ferroelectric polarization value while taking into account the anisotropic nature of the piezoelectric tensor and polarization orientation.

Zhao, T. et al. Electrical control of antiferromagnetic domains in multiferroic BiFeO3 films at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 5, 823–829 (2006). First demonstration of electrical control of antiferromagnetic domain structure in a single-phase multiferroic material.

Yoshida, C., Yoshida, A. & Tamura, H. Nanoscale conduction modulation in Au/Pb(Zr, Ti)O3/SrRuO3 heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 1449–1451 (1999).

Garcia, V. et al. Giant tunnel electroresistance for non-destructive readout of ferroelectric states. Nature 460, 81–84 (2009). First demonstration of polarization-controlled tunnel electroresistance effect using a combination of PFM and C-AFM.

Gruverman, A. et al. Tunneling electroresistance effect in ferroelectric tunnel junctions at the nanoscale. Nano Lett. 9, 3539–3543 (2009).

Seidel, J. et al. Conduction at domain walls in oxide multiferroics. Nat. Mater. 8, 229–234 (2009). First demonstration of domain wall conductivity using a combination of PFM and C-AFM.

Geng, Y., Lee, N., Choi, Y. J., Cheong, S. W. & Wu, W. Collective magnetism at multiferroic vortex domain walls. Nano Lett. 12, 6055–6059 (2012).

Denning, D., Guyonnet, J. & Rodriguez, B. J. Applications of piezoresponse force microscopy in materials research: from inorganic ferroelectrics to biopiezoelectrics and beyond. Int. Mater. Rev. 61, 46–70 (2016).

Rodriguez, B. J., Callahan, C., Kalinin, S. V. & Proksch, R. Dual-frequency resonance-tracking atomic force microscopy. Nanotechnology 18, 475504 (2007).

Harnagea, C., Alexe, M., Hesse, D. & Pignolet, A. Contact resonances in voltage-modulated force microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 338–340 (2003).

Borowiak, A. S. et al. Electromechanical response of amorphous LaAlO3 thin film probed by scanning probe microscopies. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 012906 (2014).

Bark, C. W. et al. Switchable induced polarization in LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterostructures. Nano Lett. 12, 1765–1771 (2012).

Kim, Y. et al. Mechanical control of electroresistive switching. Nano Lett. 13, 4068–4074 (2013).

Seol, D., Kim, B. & Kim, Y. Non-piezoelectric effects in piezoresponse force microscopy. Curr. Appl. Phys. 17, 661–674 (2017).

Miao, H., Tan, C., Zhou, X., Wei, X. & Li, F. More ferroelectrics discovered by switching spectroscopy piezoresponse force microscopy? EPL 108, 27010 (2014).

Hermes, I. M. et al. Ferroelastic fingerprints in methylammonium lead iodide perovskite. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 5724–5731 (2016).

Kutes, Y. et al. Direct observation of ferroelectric domains in solution-processed CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite thin films. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 3335–3339 (2014).

Balke, N. et al. Differentiating ferroelectric and nonferroelectric electromechanical effects with scanning probe microscopy. ACS Nano 9, 6484–6492 (2015). Consideration of various mechanisms of the PFM image formation.

Kalinin, S. V. & Bonnell, D. A. Imaging mechanism of piezoresponse force microscopy of ferroelectric surfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 65, 125408 (2002).

Soergel, E. Piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM). J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 44, 464003 (2011).

Balke, N. et al. Quantification of surface displacements and electromechanical phenomena via dynamic atomic force microscopy. Nanotechnology 27, 425707 (2016).

Morozovska, A. N. et al. Piezoresponse force spectroscopy of ferroelectric-semiconductor materials. J. Appl. Phys. 102, 114108 (2007).

Dahan, D. et al. Ferroelectric domain inversion: the role of humidity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 152902 (2006).

Chanthbouala, A. et al. Solid-state memories based on ferroelectric tunnel junctions. Nat. Nano 7, 101–104 (2012).

Pantel, D., Goetze, S., Hesse, D. & Alexe, M. Reversible electrical switching of spin polarization in multiferroic tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 11, 289–293 (2012).

Chanthbouala, A. et al. A ferroelectric memristor. Nat. Mater. 11, 860–864 (2012).

Kim, D. J. et al. Ferroelectric tunnel memristor. Nano Lett. 12, 5697–5702 (2012).

Boyn, S. et al. Learning through ferroelectric domain dynamics in solid-state synapses. Nat. Commun. 8, 14736 (2017).

Valencia, S. et al. Interface-induced room-temperature multiferroicity in BaTiO3. Nat. Mater. 10, 753–758 (2011).

Martin, L. W. et al. Nanoscale control of exchange bias with BiFeO3 thin films. Nano Lett. 8, 2050–2055 (2008).

Chu, Y.-H. et al. Electric-field control of local ferromagnetism using a magnetoelectric multiferroic. Nat. Mater. 7, 478–482 (2008).

Gross, I. et al. Real-space imaging of non-collinear antiferromagnetic order with a single-spin magnetometer. Nature 549, 252–256 (2017).

Geng, Y. et al. Direct visualization of magnetoelectric domains. Nat. Mater. 13, 163–167 (2014).

Choi, T. et al. Insulating interlocked ferroelectric and structural antiphase domain walls in multiferroic YMnO3. Nat. Mater. 9, 253–258 (2010).

Chae, S. C. et al. Direct observation of the proliferation of ferroelectric loop domains and vortex-antivortex pairs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 167603 (2012).

Lilienblum, M. et al. Ferroelectricity in the multiferroic hexagonal manganites. Nat. Phys. 11, 1070–1073 (2015).

Jungk, T., Hoffmann, Á., Fiebig, M. & Soergel, E. Electrostatic topology of ferroelectric domains in YMnO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 012904 (2010).

Evans, D. M. et al. Magnetic switching of ferroelectric domains at room temperature in multiferroic PZTFT. Nat. Commun. 4, 1534 (2013).

Naumov, I. I., Bellaiche, L. & Fu, H. Unusual phase transitions in ferroelectric nanodisks and nanorods. Nature 432, 737–740 (2004).

Lee, W. et al. Individually addressable epitaxial ferroelectric nanocapacitor arrays with near Tb inch−2 density. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 402–407 (2008).

Ivry, Y., Chu, D. P., Scott, J. F. & Durkan, C. Flux closure vortex-like domain structures in ferroelectric thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 207602 (2010).

McQuaid, R. G. P., McGilly, L. J., Sharma, P., Gruverman, A. & Gregg, J. M. Mesoscale flux-closure domain formation in single-crystal BaTiO3. Nat. Commun. 2, 404 (2011).

Zhang, Q. et al. Nanoscale bubble domains and topological transitions in ultrathin ferroelectric films. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702375 (2017).

Catalan, G., Seidel, J., Ramesh, R. & Scott, J. F. Domain wall nanoelectronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 119–156 (2012). Key review article on domain walls highlighting the role of PFM in delineating their properties.

Meier, D. et al. Anisotropic conductance at improper ferroelectric domain walls. Nat. Mater. 11, 284–288 (2012).

Schaab, J. et al. Optimization of electronic domain-wall properties by aliovalent cation substitution. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2, 1500195 (2016).

Guyonnet, J., Gaponenko, I., Gariglio, S. & Paruch, P. Conduction at domain walls in insulating Pb(Zr0.2Ti0.8)O3 thin films. Adv. Mater. 23, 5377–5382 (2011).

Sluka, T., Tagantsev, A. K., Bednyakov, P. & Setter, N. Free-electron gas at charged domain walls in insulating BaTiO3. Nat. Commun. 4, 1808 (2013).

Oh, Y. S., Luo, X., Huang, F.-T., Wang, Y. & Cheong, S.-W. Experimental demonstration of hybrid improper ferroelectricity and the presence of abundant charged walls in (Ca,Sr)3Ti2O7 crystals. Nat. Mater. 14, 407–413 (2015).

McQuaid, R. G. P., Campbell, M. P., Whatmore, R. W., Kumar, A. & Gregg, J. M. Injection and controlled motion of conducting domain walls in improper ferroelectric Cu-Cl boracite. Nat. Commun. 8, 15105 (2017).

Whyte, J. R. et al. Ferroelectric domain wall injection. Adv. Mater. 26, 293–298 (2014).

Whyte, J. R. & Gregg, J. M. A diode for ferroelectric domain-wall motion. Nat. Commun. 6, 7361 (2015).

Mundy, J. A. et al. Functional electronic inversion layers at ferroelectric domain walls. Nat. Mater. 16, 622–627 (2017).

Sharma, P. et al. Nonvolatile ferroelectric domain wall memory. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700512 (2017).

Zubko, P., Catalan, G. & Tagantsev, A. K. Flexoelectric effect in solids. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 43, 387–421 (2013).

Lu, H. et al. Mechanical writing of ferroelectric polarization. Science 336, 59–61 (2012). Pioneering observation of purely mechanical 180° switching of polarization via flexoelectric effect.

Sharma, P. et al. Electromechanics of ferroelectric-like behavior of LaAlO3 thin films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 6538–6544 (2015).

Das, S. et al. Controlled manipulation of oxygen vacancies using nanoscale flexoelectricity. Nat. Commun. 8, 615 (2017).

Yang, M. M., Kim, D. J. & Alexe, M. Flexo-photovoltaic effect. Science 360, 904–907 (2018). The bulk photovoltaic effect can be realized in any semiconductor, including silicon, via the flexoelectric effect.

Yang, S. Y. et al. Above-bandgap voltages from ferroelectric photovoltaic devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 143–147 (2010).

Bhatnagar, A., Roy Chaudhuri, A., Heon Kim, Y., Hesse, D. & Alexe, M. Role of domain walls in the abnormal photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Nat. Commun. 4, 2835 (2013).

Yang, M.-M., Bhatnagar, A., Luo, Z.-D. & Alexe, M. Enhancement of local photovoltaic current at ferroelectric domain walls in BiFeO3. Sci. Rep. 7, 43070 (2017).

Yang, M. M. & Alexe, M. Light-induced reversible control of ferroelectric polarization in BiFeO3. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704908 (2018). Demonstration of light-induced ferroelectric switching.

Ievlev, A. V. et al. Chemical state evolution in ferroelectric films during tip-induced polarization and electroresistive switching. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 29588–29593 (2016).

Nath, R., Chu, Y.-H., Polomoff, N. A., Ramesh, R. & Huey, B. D. High speed piezoresponse force microscopy: <1 frame per second nanoscale imaging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 072905 (2008).

Campbell, M. P. et al. Hall effect in charged conducting ferroelectric domain walls. Nat. Commun. 7, 13764 (2016).

Schaab, J. et al. Contact-free mapping of electronic transport phenomena of polar domains in SrMnO3 films. Phys. Rev. Appl. 5, 054009 (2016).

De Luca, G. et al. Domain wall architecture in tetragonal ferroelectric thin films. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605145 (2017).

Kim, D. J. et al. Observation of inhomogeneous domain nucleation in epitaxial Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 capacitors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 132903 (2007).

Gruverman, A., Cross, J. S. & Oates, W. S. Peculiar effect of mechanical stress on polarization stability in micrometer-scale ferroelectric capacitors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 242902 (2008).

Jesse, S. et al. Direct imaging of the spatial and energy distribution of nucleation centers in ferroelectric materials. Nat. Mater. 7, 209–215 (2008).

Park, M. et al. Three-dimensional ferroelectric domain imaging of epitaxial BiFeO3 thin films using angle-resolved piezoresponse force microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 112907 (2010).

Labuda, A. & Proksch, R. Quantitative measurements of electromechanical response with a combined optical beam and interferometric atomic force microscope. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 253103 (2015).

Jesse, S., Kalinin, S. V., Proksch, R., Baddorf, A. P. & Rodriguez, B. J. The band excitation method in scanning probe microscopy for rapid mapping of energy dissipation on the nanoscale. Nanotechnology 18, 435503 (2007).

Peter, F. et al. Contributions to in-plane piezoresponse on axially symmetrical samples. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 76, 106108 (2005).

Acknowledgements

A.G. acknowledges support by the National Science Foundation through Materials Research Science and Engineering Center under Grant No. DMR-0820521. M.A. acknowledges support of Royal Society through the Wolfson Research Merit and Theo Murphy Blue-sky Awards and EPSRC (UK) through Grant Nos. EP/P031544/1 and EP/P025803/1. D.M. thanks NTNU for support through the Onsager Fellowship Programme and the Outstanding Academic Fellows Programme. The authors thank Steffen Brosseit (Brossboss Entertainment) for animating Fig. 1a, b.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to all aspects of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks Colm Durkan and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gruverman, A., Alexe, M. & Meier, D. Piezoresponse force microscopy and nanoferroic phenomena. Nat Commun 10, 1661 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09650-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09650-8

This article is cited by

-

Electrically induced cancellation and inversion of piezoelectricity in ferroelectric Hf0.5Zr0.5O2

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Tertiary nanocomposite-based self-powered E-skin as energy harvester and electronic nose

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2024)

-

Room-temperature ferromagnetism and piezoelectricity in metal-free 2D semiconductor crystalline carbon nitride

Nano Research (2024)

-

Imaging ferroelectric domains with a single-spin scanning quantum sensor

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Electrically switchable anisotropic polariton propagation in a ferroelectric van der Waals semiconductor

Nature Nanotechnology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.